#taeniolabis

Text

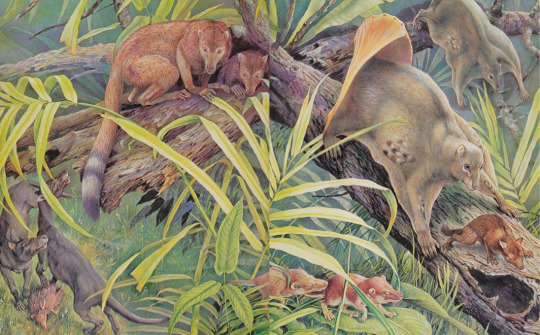

The Evolution of the Mammals. Written by L. B. Halstead. Illustration by Sergio. 1978.

Internet Archive

#prehistoric#prehistoric mammals#plesiadapis#planetetherium#palaeoryctes#priacodon#protictis#taeniolabis#Sergio

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

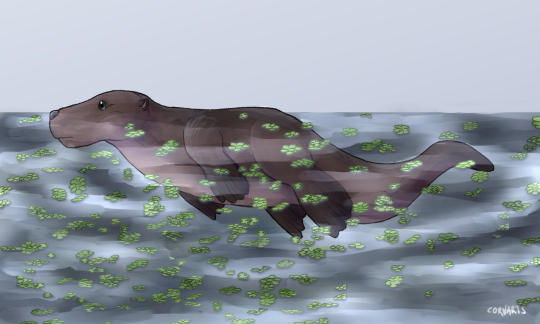

Multituberculate Earth: Taeniolabidoidea

Derived lambdopsalid Cervochenia noduonti by foulserpent. Noticed hooved feet, digit reduction and MASSIVE DONG THAT EVOLVED AS A DISPLAY DEVICE.

(As with all animal pages so far, this only goes so far into the Oligocene… for now. )

Taeniolabidoids are the cimolodont group most adapted to herbivory, having lost their plagiaulacoids and expanded their molars into larger grinding surfaces; while the incisors didn’t grow perpetually like in rodents, in any least some species they kept emerging after the roots closed. Traditionally interpreted as sister-taxa to kogaionids, the most recent consensus seems to place them as slightly closer to the main cimolodont clade rather than them, making them essentially the second most basal lineage.

They first evolved in the Late Cretaceous, with Yubaatar and Erythrobaatar in Asia and Bubodens in North America. Successfully crossing the KT event in spite of their herbivorous habits, they soon diverged into two major clades: Taeniolabididae, occuring in North America and attaining large sizes (the iconic Taeniolabis taoensis weights somewhere between 30 and 100 kg depending on the study, making it not only the largest multituberculate known but also one of the largest mammals of its time) and Lambdopsalidae, ocurring in Asia and mostly diversifying as burrowing herbivores. In our timeline, the former die out in the Danian and the latter endure until the PETM, in environments otherwise dominated by rodents with no signs of diversity decrease; they easily make a strong case for rodents not being the main reason why multituberculates went extinct.

In this timeline, both groups endured, obviously. Idiot.

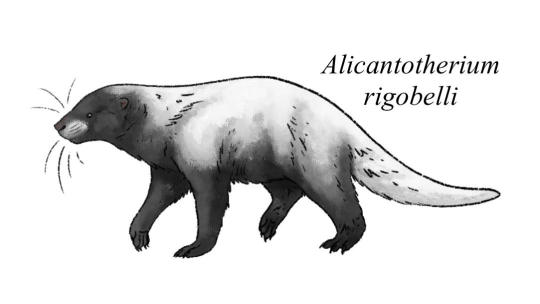

Alicantotherium rigobelli, from the early Paleocene of Bolivia. By pale.relics.

Taeniolabidids kept diversifying as large sized herbivores past the Danian in this timeline, their trajectory in some ways mirroring that of large placental herbivores from our timeline like pantodonts and “condylarth” ungulates. They became the dominant megafaunal herbivores in the northern continents, the largest species weighing up to a ton. Their diversity is particularly high in North America and Europe, with only a single genus in Asia, Kamuilabis. One species, Alicantotherium rigobelli, also occurs in the Santa Lucía Formation of Bolivia, suggesting a short lived excursion into South America.

Taeniolabis itself might have already been semi-aquatic, so it is of no surprise that several Paleocene genera were already exploring aquatic niches (though many were unambiguously terrestrial). Most notably is footprint evidence suggesting they foraged on the coastline, the earliest Cenozoic evidence of mammals exploiting the sea and mirroring our world’s pantodonts in this regard.

The PETM saw a reduction in size much as in our world, with semi-aquatic species in particular prevailing over more terrestrial ones. The arrival of gondwanatheres in Asia pretty much ended their reign there on land, but North America and Europe saw their local diversity quickly recover in the Eocene’s nascent rainforests and reclaim their position inland (though in Europe they were comparatively rare, the dominant giant herbivores being gastornithid birds). Some of these forms reached as many as 3 tons, dwarfed only by African galulatheriids and South American/Antarctic/Australian mesungulatid dryolestoids.

Though these unique polar swimmers eventually died out, other taeniolabidids would explore marine environments further south in the Caribbean, and later spread across the Tethys as far east as India and westwards in the Pacific both to the northwest and South American coast, grazing on the abundant sea grass meadows. Some even arrived to Afro-Arabia and South America, returning inland to occupy freshwater niches.

With the Grand Coupure the reign of taeniolabidids on the northern continents came to an end. Collapsing rainforest biomes and herds of Asian gondwanatheres marching towards North America and Europe resulted in the extinction of the giant land herbivores, starved and outcompeted. But in the sea, taeniolabidids reached unparalleled success: the descendents of the second wave of sea goers achieved a cosmopolitan distribution, in polar waters even reaching sizes comparable to those of our largest desmostylians and Steller’s Sea Cow.

Barred from the mainland, the waters and islands hold a bright future for these majestic animals.

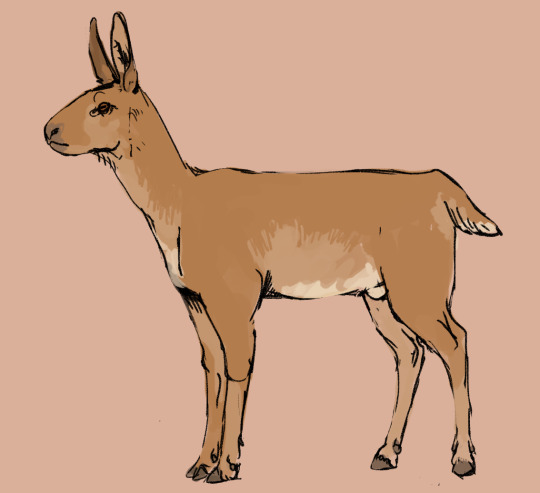

Cervochenia nuada (distinct from anterior species by slightly longer flag head) by foulserpent in display position, foaming like a camel ALSO MODIFIED FLAG-LIKE DISPLAY BENIS

The Paleocene saw a great diversity of lambdopsalids in their Asian homeland as in our world, except more as their placental competitors came crashing down. They seem to have largely replaced the local herbivorous djadochtatheroideans, ranging from small pika size and like burrowers to tall browsers and even hopping forms (as if mocking djadochtatheroideans further). One of their most distinguishing features in real-like was uniquely hypsodont molar teeth, suggesting that they were among the first local mammals to be specialised grazers; here, this is certainly apparent as they are among the first Cenozoic multituberculates to display adaptations for cursoriality in this timeline, marking them as well adapted for open biomes.

The PETM was especially harsh as it coincided with the collision with India, bringing gondwanathere competitors to Asia. Combined with the spread of rainforests, most of the earlier lambdopsalid radiation became extinct, with no species above 10 kg crossing the Paleocene/Eocene boundary. The small sized survivors, however, thrived and even colonised North America, spreading as small sized herbivores swiftly running across the forest floors and/or digging.

The Eocene saw the reduction of digits, with the forelimb coming to be supported on two toes while the hindlimb on a single one, an arrangement similar to some of our bandicoots particularly the Chaeropus genus. This seems to be a compromise between both increased cursoriality and retained digging habits much as in bandicoots, and like them it lead to the development of true hooves. In our bandicoots young are deposited in the pouch by placental stalks, thus removing the need for grasping forelimbs; conversely, juvenile monotremes (which as adults also have non-grasping, specialised forelimbs) actually move about very often in the mother’s pouch in search of mammary glands. Do lambdopsalids need a way around like bandicoots or don’t like monotremes? YOU DECIDE. Disregard that, multituberculates apparently gestated live young like placentals do there’s no need to overexplain the hooved forelimbs.

With the Grand Coupure, lambdopsalids moved into Europe, displacing several local small herbivores like ferugliotheriids and boffiids. With the spread of open grasslands they were allowed to attain large sizes once more, some Oligocene forms as large as an elk. In general there is some faunal provincialism, with lambdopsalids being more common in Eurasia and adalatheriids in North America, though both groups occurred across both landmasses.

Like all non-placental mammals multituberculates have bifurcated penises, and in lambdopsalids this lead to a truly unique evolutionary novelty. In derived species, one of the heads evolved into a flag-like organ and lost its urethra, while the other retained it and remained relatively small, just long enough to do its job. Thus, rather than horns and tusks the lambdopsalids probably developed the most direct sexual displays of any tetrapod.

As the world keeps cooling and drying and plains spread, lambdopsalids have bright horizons ahead. Soon, Afro-Arabia and Asia will collide, leading to interesting results…

#multituberculate earth#multituberculate#multituberculata#speculative zoology#speculative biology#spec evo#speculative evolution

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

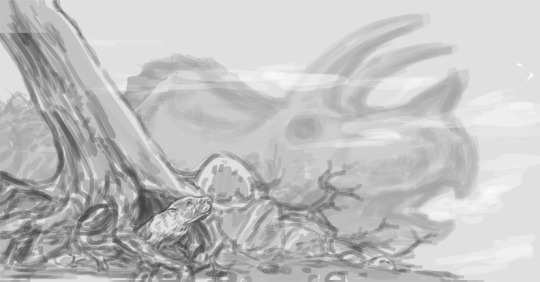

The final version of my illustration for a new collected illustration book project based around the K-Pg mass extinction event.

#paleo#paleoart#paleontology#sciart#science#dinosaur#dinosaurart#dino#dinoart#triceratops#taeniolabis#educational#naturalhistory#digitalart#digitalillustration#illustrationart#illustration#art#artist#maineartist#maine#newenglandartist#artistsontumblr

427 notes

·

View notes

Note

Help me out: which is larger, Taeniolabis or Peligrotherium?

Who fuckin knows. The latter is only known from scraps of skull material and teeth, and far as I can tell none of its close relatives have postcrania either.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil trove shows life's fast recovery after big extinction

https://sciencespies.com/biology/fossil-trove-shows-lifes-fast-recovery-after-big-extinction/

Fossil trove shows life's fast recovery after big extinction

This image provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019 shows a rendering of the ancient Carsioptychus mammal taken from the PBS NOVA special, Rise of the Mammals. In this recreation, Carsioptychus coarctatus eats plants in a newly diversified forest, 300,000 years after the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs. (Jellyfish Pictures/HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

A remarkable trove of fossils from Colorado has revealed details of how mammals grew larger and plants evolved after the cataclysm that killed the dinosaurs.

The thousands of specimens let scientists trace that history over a span of 1 million years, a mere eyeblink in Earth’s lifespan.

Sixty-six million years ago, a large meteorite smashed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula of southeastern Mexico. It unleashed broiling waves of heat and filled the sky with aerosols that blotted out the sun for months, killing off plants and the animals that depended on them.

More than three-quarters of species on Earth died out.

But life came back, and land mammals began to expand from being small creatures into the wide array of forms we see today—including us.

So the new find taps into “the origin of the modern world,” said Tyler Lyson, an author of a paper reporting the fossil finds Thursday in the journal Science.

The fossils were recovered from an area of steep bluffs covering about 10 square miles (17 square kilometers) near Colorado Springs, starting three years ago.

Lyson, of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, found little in that area when he followed the standard practice of scanning for bits of bone. But that changed when he began looking instead for rocks that can form around bone. When the rocks were broken open, skulls and other fossils within were revealed.

This photo provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019 shows some of the mammal skull fossils retrieved from Corral Bluffs, Colo. A trove of fossils has revealed details of how life rebounded after the cataclysm that killed off the dinosaurs. (Frank Verock/HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

Lyson said it’s not clear how wide a geographic region the fossils’ story of recovery applies to, but that he thinks they show what happened over North America.

“We just know so little about this everywhere on the globe,” he said. “At least now we have at one spot a fantastic record.”

Experts not connected to the study were enthusiastic.

It’s “an unparalleled documentary of how life on land recovered” after the asteroid impact, said P. David Polly of Indiana University in Bloomington. “The sheer number of fossil specimens and the quality of their preservation are exceptional” for this time period, he said.

The fossils’ story certainly represents what happened in central North America and perhaps more broadly, he wrote in an email.

Stephanie Smith of the Field Museum in Chicago said the study’s detailed focus on a single area can help scientists understand the complexity of recovery when combined with results from elsewhere.

This photo provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019 shows a collection of four mammal skulls collected from Corral Bluffs, Colo. From left are Loxolophus, Carsioptychus, Taeniolabis, Eoconodon. A trove of fossils has revealed details of how life rebounded after the cataclysm that killed off the dinosaurs. (HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

Scientists have previously found little evidence about what happened in the aftermath of the meteorite crash, especially on land, said Jin Meng of the American Museum of Natural History in New York. The new work, he said in an email, appears to provide “the best record on Earth to date.”

The study reports on hundreds of mammal fossils representing 16 species and more than 6,000 plant fossils. Researchers also analyzed thousands of pollen grains to see what plants were alive at various times. Analysis of leaves indicated several warming periods during the period.

Here’s the recovery story the fossils tell:

The area had been a forest before the meteorite hit, home to dinosaurs like T. rex and mammals no bigger than about 17 pounds (8 kilograms).

This photo provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019 shows a fern fossil collected from Corral Bluffs, Colo. A trove of fossils has revealed details of how life rebounded after the cataclysm that killed off the dinosaurs. (Frank Verock/HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

Soon after the disaster, the environment was blanketed with ferns and the biggest mammal around was about as heavy as a rat. The world was in a warming period, as documented in previous studies.

By about 100,000 years after the meteorite impact, the forest was dominated by palm trees and mammals had grown to the weight of raccoons, almost as big as before the meteorite crash. “That’s a pretty rapid recovery, or at least one aspect of recovery,” Lyson said.

By 300,000 years, the walnut tree family had diversified, and the biggest mammals were plant eaters about as heavy as a large beaver. Based on other studies of their diet, they may have evolved along with those trees, Lyson said.

This photo provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019 shows some of the plant fossils retrieved from Corral Bluffs, Colo. More than 6,000 leaves were collected as part of the study to help determine how and when Earth’s forest rebounded after the mass extinction event. (Frank Verock/HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

By 700,000 years, the fossil record shows the first known appearance of legume plants, the family that includes peas and beans. And it reveals the two largest mammals found in the study, with the larger one weighing about 100 pounds (50 kilograms), roughly like a wolf. That is about 100 times heavier than the mammals that survived the extinction, “which I think is pretty fast” for growth, Lyson said.

What drove mammals to get bigger? The main factor was the disappearance of the dinosaurs, leaving an ecological niche to be filled, he said. But the quality and types of food on the landscape probably also played a role, he said. The simultaneous appearance of legume plants and bigger mammals suggests the plants may have provided a “protein bar moment,” Lyson said.

He said the mammals were creatures that evolved from animals that had survived extinction or those that immigrated from elsewhere.

In this photo provided by HHMI Tangled Bank Studios in October 2019, a storm rolls in towards Corral Bluffs, Colo, outside of Denver. The area represents about 300 vertical feet of rock and preserves the extinction of the dinosaurs through the first million years of the Age of the Mammals. The exposure is composed of hard yellow sandstone and mudstones, which represent ancient rivers and floodplains, respectively. (Frank Verock/HHMI Tangled Bank Studios via AP)

Zhe-Xi Luo of the University of Chicago, who did not participate in the work, said the report is remarkable for tying together records for plants, mammals and temperature, giving a “holistic picture.”

Scientists expected mammals to recover after the dinosaur extinctions, he said, and the new work “is a huge step forward in getting a firm understanding about just how it happened.”

Explore further

Researchers discover first winged mammals from the Jurassic period

More information:

T.R. Lyson el al., “Exceptional continental record of biotic recovery after the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction,” Science (2019). science.sciencemag.org/lookup/ … 1126/science.aay2268

“Stepping out of the dinosaurian shadow,” Science (2019). science.sciencemag.org/lookup/ … 1126/science.aaz6313

© 2019 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Citation:

Fossil trove shows life’s fast recovery after big extinction (2019, October 24)

retrieved 24 October 2019

from https://phys.org/news/2019-10-fossil-trove-life-fast-recovery.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

#Biology

0 notes

Note

Had an idea for a WWB reboot: Paleocene episode in NA with Taeniolabis and other multies, Eocene episode in Turkey with Necromantis ("Killer Bat"), Oligocene midwest episode with nimravids and bathornithids, Miocene episode in Australia, Pliocene episode in Antarctica and Pleistocene episode in Vietnam with Palaeoloxodon namadicus

Have fun with that.

0 notes

Text

Fossils show life’s recovery after dino-killing asteroid strike

Scientists have discovered an extraordinary collection of fossils that reveal in detail how life recovered after the asteroid impact that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous Period.

The unprecedented find—thousands of exceptionally preserved animal and plant fossils from the first million years after the catastrophe—shines light on how life emerged from one of Earth’s darkest hours.

Scientists unearthed this new record from the first million years after the asteroid impact in the region around Colorado Springs, Colorado, which forms part of a larger geological province known as the Denver Basin. The find includes both plants and animals, painting a portrait of the emergence of the post-dinosaur world.

A cranium of a Taeniolabis taoensis, a herbivorous mammal, uncovered at the Corral Bluffs fossil site. Taeniolabis appears approximately 700,000 years after the end-Cretaceous mass extinction, approximately at the same time as the world’s oldest legume fossil. (Credit: HHMI Tangled Bank Studios)

“I’ve been working on this time period and on these mammals for 21 years, and this is truly an exceptional window into this pivotal event in life history,” says coauthor Greg Wilson, a professor of biology at the University of Washington and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture. “We change over from terrestrial ecosystems dominated by dinosaurs to those that become dominated by mammals in a geological blink of an eye.”

Fossils show how life changed

“The course of life on Earth changed radically on a single day 66 million years ago,” says lead author Tyler Lyson, the curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “Blasting our planet, an asteroid triggered the extinction of three of every four kinds of living organisms. While it was a really bad time for life on Earth, some things survived, including some of our earliest, earliest ancestors.”

A moment of serendipity pointed the way to these rare fossil finds. Lyson, who had been looking for post-impact vertebrate fossils without success, took inspiration from a fossil that had been sitting in a museum drawer and fossil-hunting techniques used by colleagues in South Africa. In the summer of 2016, he stopped looking for glinting bits of bone in the Denver Basin and instead zeroed in on egg-shaped rocks called concretions.

Cracking open the concretions, Lyson and coauthor Ian Miller, curator of paleobotany and director of Earth and space sciences, found fossils such as the skulls of mammals from the early generations of survivors of the mass extinction. Since most of what is understood from this era is based on tiny fragments of fossils, such as pieces of mammal teeth, finding a single skull would be exceptional. Lyson and Miller found four in a single day and more than a dozen in a week. So far, they’ve found fossils from at least 16 different mammalian species.

A big comeback

Wilson participated in excavations at Corral Bluffs, a site just east of Colorado Springs. He and coauthor Stephen Chester, an assistant professor at the City University of New York’s Brooklyn College, worked to identify the mammal fossil that the team found, calculate changes in body size over time, and analyze the diversity of species after the asteroid impact.

The researchers determined that just 100,000 years after the cataclysm, mammalian diversity had approximately doubled. At 300,000 years after the impact, the maximum body mass of mammals had increased threefold, and mammals were evolving specialized diets, possibly in response to changes in plant diversity.

An overhead view of selected plant fossils retrieved from Corral Bluffs. (Credit: HHMI Tangled Bank Studios)

These findings illustrate how the Denver Basin site also is adding evidence to the idea that the recovery and evolution of plants and animals were intricately linked after the asteroid impact. The researchers collected more than 6,000 leaf fossils as part of the study to help determine how and when Earth’s forest rebounded after the mass extinction event. Combining a remarkable fossil plant record with the discovery of the fossil mammals allowed the team to link millennia-long warming spells to specific global events, including massive amounts of volcanism on the Indian subcontinent.

These events may have shaped the ecosystems half a world away. For example, the research team saw another increase in body size among mammals at about 700,000 years post-impact, which coincided with the evolution of legumes, then a new type of plant. Additional analyses of these fossils, as well as the unearthing of new specimens, will only deepen scientists’ understanding of this critical period in Earth’s history and the evolution of mammals that came before humans.

“Our understanding of the asteroid’s aftermath has been spotty,” Lyson explains. “These fossils tell us for the first time how exactly our planet recovered from this global cataclysm.”

The research appears in the journal Science.

Additional coauthors are from the Denver Museum of Nature & Science; the University of New Hampshire; the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History; Wesleyan University; the University of Maryland; and Colorado College. Funding for the research came from the Lisa Levin Appel Family Foundation, M. Cleworth, Lyda Hill Philanthropies, David B. Jones Foundation, ML and SR Kneller, T. and K. Ryan, and JR Tucker as part of the Denver Museum of Nature & Science No Walls: Schools initiative.

Source: University of Washington

The post Fossils show life’s recovery after dino-killing asteroid strike appeared first on Futurity.

Fossils show life’s recovery after dino-killing asteroid strike published first on https://triviaqaweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Colorado Fossils Show How Mammals Raced to Fill Dinosaurs’ Void

Some 66 million years ago, mammals caught their lucky break. An asteroid crashed into what is now Chicxulub, Mexico, and set off a catastrophic chain of events that led to the annihilation of the non-avian dinosaurs. That day began their furry ascension to the top of a brave new world, the one from which our species would one day emerge. But little is known about the time period directly after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, or K-Pg event, because the fossil record is lacking.

Now, a team of paleontologists has uncovered a trove of thousands of fossils in Colorado that provides an in-depth look at the first million years following the K-Pg mass extinction event. The finding provides insight into the interactions between animals, plants and climate that occurred in the earliest days of the age of mammals, and that allowed them to grow from the size of large rodents into diverse wildlife we might begin to recognize today.

“We provide the most vivid picture of recovery of an ecosystem on land after any mass extinction,” said Tyler Lyson, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. His team’s paper was published on Thursday in Science.

Dr. Lyson has hunted fossils since he was 10. Although he has found many dinosaurs, uncovering fossils of species that emerged in the immediate aftermath of the dinosaur extinction had proven rather elusive in his field of study.

“You can only find so many triceratops skeletons and partial T. rex skeletons and things like that until you want a larger challenge,” said Dr. Lyson. “Finding fossils just after the K-Pg extinction is a huge, huge challenge.”

In spring 2016 he and some colleagues explored a fossil site near Colorado Springs called Corral Bluffs. He knew that years earlier, Sharon Milito, an amateur fossil hunter, had found a mammal skull that was confirmed to be from the K-Pg boundary there. He set out looking for mammal bones sticking out of the ground. But his search proved fruitless.

As he wandered around the bluff, he thought back to his time as a graduate student working in South Africa. There, he had learned to spot certain rocks called concretions that held fossils captive, like pearls in oysters. He shifted his focus from bones to rocks.

“I found this ugly white-looking rock that looked like it had a little mammal jaw coming out of it,” Dr. Lyson said. He cracked it open and found inside part of a fossilized crocodile. “That was the moment when the light bulb went off. If there’s one concretion with fossils inside, there’s got to be more.”

He and his colleagues returned to Corral Bluffs that September and searched for more of the ugly rocks.

“When I cracked open the very first concretion I found a mammal skull,” Dr. Lyson said.

It was the most complete mammal from the K-Pg interval that he had ever seen. Within an hour they found four or five more. So far, they have uncovered more than 1,000 vertebrate fossils and 16 different mammal species.

“With this discovery, we’re starting to see the entire skull of many of these mammals that we previously only knew from teeth,” said Stephen Chester, a mammalian paleontologist at Brooklyn College and an author on the paper.

The skulls tell a story of mammalian resilience. Whereas rat-size mammals survived the extinction event, raccoon-size ones perished. About 100,000 years after the K-Pg event, mammals bounced back, with raccoon-size mammals reappearing.

Some 300,000 years after the asteroid struck, more mammals appeared, such as Loxolophus and the small pig-size Carsioptychus appeared. Within 700,000 years, the capybara-size Taeniolabis and the wolf-size Eoconodons began to thrive.

“You’re going from a very small dog that you’d see on the streets on New York City to a very large wolf within those hundreds of thousands of years,” Dr. Chester said.

The team also collected more than 6,000 fossilized leaves and analyzed more than 37,000 pollen grains. Together the items describe the re-emergence of plant life, which may have been a crucial factor in the evolution of mammals.

First came the ferns. With their feather-like leaves, they proliferated across the wasteland for many hundreds of years to a couple thousand years, paving the way for forests to rebound.

Next, the palms paraded in, dominating the green scene for hundreds of thousands of years.

Then around 300,000 years after the catastrophe, a diverse array of walnuts appeared. That coincided with the jump in diversity and body size of herbivorous mammals, which suggests they were an important food source.

“We call that world the ‘Pecan Pie World,’” said Ian Miller a paleobotanist at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. He added that this epoch also coincided with a warming period in the fossil record, which could indicate that a shifting climate played a role in the development of plants and animals following the extinction event.

One of their most important botanical finds — a fossil bean pod — was made one summer by a high school student while the team was working with NOVA for a documentary that will be broadcast Wed., Oct. 30 on PBS.

“There she is holding the world’s earliest fossil legume,” Dr. Miller said. “She just had this ear-to-ear smile, totally beaming.”

They dated the legume to around 700,000 years after the mass extinction event. That period was tied to another short warming pulse, as well as to the appearance of the wolf-size mammals. Perhaps the legumes were fueling furry animals, the team suggested.

“We liken them to the protein bars of the ancient world,” Dr. Miller said. One remaining question, he added, is whether climate drove the changes in the plants and mammals.

Courtney Sprain, a geoscientist at the University of Florida, said she was impressed by their animal, plant and climate records. “That’s one of the really spectacular things about this paper, just how amazing the preservation is and how good the record is for a variety of different changes following a mass extinction.”

Other paleontologists agreed.

“I looked at this and went ‘Wow, that’s a lot of skulls!’” said Jaelyn Eberle, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Colorado at Boulder, who was not involved in the paper. She said a next step should be to perform micro CT scans on the skulls, to determine the brain sizes and compartments, which would provide insight into the animals’ sensory abilities.

The find also helps elucidate how species are able to respond to catastrophic events in a relatively rapid time frame.

“It has obvious ramifications for the current biodiversity and climate crisis, as we start to approach similar levels of devastation,” said Anjali Goswami, a vertebrate paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London. The current crisis, she added, is “ unfortunately caused by our own shortsighted avarice, rather than a chance encounter with an extraterrestrial body.”

Sahred From Source link Science

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2WaZgLb

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

“Cool fossils I’ve held” compilation: mosasaur vertebra, taeniolabis teeth, pretty little crinoids.

79 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Taeniolabis.

I couldn't find many restorations online so i drew one, haha. Taeniolabis was the largest mammal discovered to have lived through the Cretaceous extinction event and into the Eocene. It was the size of a beaver.

(If you click through on the blog you can see a better resolution.)

Also, they're known mostly from their teeth only (as with a lot of early mammals) so all restorations are very speculative.

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Work in progress underpainting for my current illustration for an upcoming paleoart project about the KPg mass extinction event. A lone Taeniolabis emerging from shelter amongst the smoldering corpses of the giants it once dwelled beneath.

#workinprogress#wip#paleoart#paleontology#paleo#paleoartprocess#sciart#science#educational#dinosaur#dinosaurart#dino#dinoart#mammal#taeniolabis#triceratops#prehistoric#extinction#digitalart#digitalillustration#illustration#illustrationart#art#artist#maine#maineartist#newenglandartists#artistsontumblr

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-apocalyptic fossils show rise of mammals after dinosaur demise

https://sciencespies.com/news/post-apocalyptic-fossils-show-rise-of-mammals-after-dinosaur-demise/

Post-apocalyptic fossils show rise of mammals after dinosaur demise

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – A revelatory cache of fossils dug up in central Colorado details as never before the rise of mammals from the post-apocalyptic landscape after an asteroid smacked Earth 66 million years ago and annihilated three-quarters of all species including the dinosaurs.

More

Fossilized mammal skull fossils and lower jaw retrieved from the Corral Bluffs site in Colorado dating from the aftermath of the mass extinction of species 66 million years ago is seen in a picture released October 24, 2019. HHMI Tangled Bank Studios/Handout via REUTERS.

The fossils, described by scientists on Thursday, date from the first million years after the calamity and show that the surviving terrestrial mammalian and plant lineages rebounded with aplomb. Mammals, after 150 million years of subservience, attained dominance. Plant life diversified impressively.

With dinosaurs no longer eating them, mammals made quick evolutionary strides, assuming new forms and lifestyles and taking over ecological niches vacated by extinct competitors. Within 700,000 years of the mass extinction, their body mass had become 100 times bigger than the mammals living immediately after the mass extinction.

“Were it not for the asteroid, humans would never have evolved,” said Ian Miller, curator of paleobotany and director of earth and space sciences at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. “One message I would like people to take from this is that their earliest ancestors – and by ancestors we’re talking fuzzy little squirrel-like critters – had their origins in the wake of the extinction of the dinosaurs.”

The thousands of well-preserved animal and plant fossils, unearthed just east of Colorado Springs, illuminate a time interval that had been shrouded in mystery.

“Essentially, we were able to tease out details of the emergence of the modern world – the age of mammals – from the ashes of the age of the dinosaurs,” Miller said.

Sixteen mammal species were discovered, with skulls and other bones fossilized after being buried in rivers and floodplains. Until now, only tiny mammal fossil fragments from that time had been discovered.

“For the first time, we were able link together time, fossil plants, fossil animals and temperature in one of the most critical intervals of Earth’s history,” said Tyler Lyson, the museum’s curator of vertebrate paleontology and lead author of the research published in the journal Science.

The asteroid strike, which ended the Cretaceous Period and opened the Paleogene Period, laid waste to the world, eradicating the dinosaurs except their bird descendants, seagoing reptiles that dominated the oceans, and important marine invertebrates and numerous plant species.

Plant life also was hit hard by the global environmental catastrophe that followed the crash of the six-mile-wide (10-km) asteroid off Mexico’s coast, with new forms evolving in the aftermath. The earliest-known legumes – bean pods – were among the Colorado fossils.

Evolutionary events set in motion by the mass extinction led much later to the appearance of the primate lineage that includes monkeys, apes and eventually, roughly 300,000 years ago, the appearance of our species Homo sapiens.

SHADOW OF THE DINOSAURS

Mammals had lived in the large shadow of the dinosaurs, never getting bigger than a small dog until the mass extinction. The mammals that survived the asteroid were mainly small omnivores – the largest being the size of a rat and weighing about a pound (0.5 kg).

Within 100,000 years of the extinction event, mammals reached about 13 pounds (6 kg). By 300,000 years after the extinction, they got to 55 pounds (25 kg), with the first purely herbivorous mammalian species. By 700,000 years after the asteroid, some mammals weighed more than 110 pounds (50 kg).

“When the dinosaurs go extinct, mammals proliferate, and fast,” Miller said, for the first time becoming the top predators and herbivores on the landscape.

The largest mammal among the Colorado fossils was wolf-sized Eoconodon, followed by Taeniolabis, the size of a capybara. The largest predators were 5-foot-long (1.5 meters) crocodilians, with blunt teeth useful for cracking turtle shells rather than gobbling mammals.

More

Slideshow (5 Images)

Egg-shaped rocks called concretions that over time formed concentrically around some kind of nucleus – in this case mammal skulls – provided a bonanza. Most of the 16 mammal species belonged to a diverse group called “archaic ungulates” related to modern-day hoofed mammals like deer, cows and pigs. The plant fossils included pollen, leaf impressions and petrified wood.

The mass extinction was the second worst on record – exceeded by one 252 million years ago thought to have been caused by extreme volcanism – that helped pave the way for the first dinosaurs.

“Mass extinctions,” Lyson said, “are the biologic reset button.”

Reporting by Will Dunham; Editing by Sandra Maler

Our Standards:The Thomson Reuters Trust Principles.

#News

0 notes