#the idea that a codex and a given text are the same is very much an artifact of modern publishing

Text

☆ミ 𝚖𝚊𝚔𝚎 𝚢𝚘𝚞 𝚜𝚊𝚢 “𝚘𝚑”

PART 10: BIG DICK IS BACK IN TOWN

y/n is back in brooklyn for the holidays. thinking that a stream will make her feel less homesick for cali, she starts working on her famously titled hentai.free.srv. what was supposed to be a relaxing stream turns into a special delivery about two hours in.

─── corpse husband x reader

─── soc. media + written fiction!

─── word count: 2.2k

─── ❥ req: Here's one... You know those apps for delivery like Domino's or whatnot... What if reader is streaming Among Us with Corpse, and reader mentions they're hungry and Corpse offers to order them food, and readers like no no it's fine... Then there's delivery at the door (Corpse ordered beforehand)

author’s note: fucky format is also back in town baby!!! also if you find any mistakes - no u didnt <3 thank u everyone for enjoying this story sm i literally cant believe how feral yall going strawberry cow was a nuclear explosion im still recovering tbh. got an ask a while ago and decided to incorporate it into myso. happy holidays everyone! myso will continue on monday!

ultimate masterlist. ҉ myso masterlist ҉ previous. ҉ next.

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

Indeed, being soft on any social media platform was the biggest disgrace and needed to be eliminated post haste. Moreover, it was a slippery slope - once you start flooding your timeline with cute imagery and heart emojis, what will stop you from posting inspirational Facebook quotes? Disgusting. If Rae were here, she would chide you (not you thinking about her as if she’s dead or something). For once in your life, you feel like you deserve it.

Alas, you hope this little chaos you’ve caused is enough to throw everyone off. The stans, especially. You know the hashtags, you’ve seen ARMY scourging for info online with the same fervor and ruthlessness 1 Direction fans hacked airport security cameras just to spy on the boys. If you had any dirty secrets online, they are out to the public now - thankfully, besides the Harry Styles stan account (with edits and all), you have nothing. Though, now that you think about it, exposed nudes would have been better than your Punk!Harry edit receiving almost a million views. God, your life’s a fucking mess.

Your fans aren’t the only ones out for info - you, too, are trying to decipher Rae’s message. Code: Barbecue Sauce. The two of you had come up with it roughly two years ago, around the same time when you promised that if you didn’t find significant others by the time you’re 40, you’ll just marry each other. It was one of the many rules found in your friendship codex. Barbecue Sauce signifies information - an exchange of information. And depending on how it ends or begins (”So I’m sitting there” alludes to Rae, “On my titties” alludes to you), secret data on that person is given away, usually free of charge.

But why? And to whom did Rae give away what? You had pestered her mercilessly and even sent some voice messages where you were crying. You were only crying because of a video of a grandpa smiling you saw on TikTok, but you are a snake, and so you put those tears to good use. If streaming doesn’t work out, you’ll just become an actress. Hollywood would love you. Your PR firm sure as fuck wouldn’t, though.

Rae was having none of it. She said you’ll figure it out eventually. Told you to channel your superior puzzle skills. You were quick to remind her that you can barely count to ten without having an aneurysm. Oddly serious, she admitted that she worries for you sometimes. Why only sometimes?! you demanded. She merely sighed. uttering under her breath something that sounded closely to “Boke.”

You leave her for barely a week and she’s already neck deep in the gay volleyball anime, hoodie and cardboard cutout and everything. Your life is falling apart.

But Brooklyn is nice. It had snowed when you stepped off of the plane. Thousands of snowflakes sprinkling into your hair, dotting your cheeks and nose. You missed this sight back in Cali. You missed your parents, too.

Home cooked meals, old sweaters, your old room and about 40GB worth of old high school pictures on your computer. You went through them all one night. Some were stomach churning, cringe inducing nightmares. You were especially fond of those. Texted some of your friends that were still in Brooklyn, met up, decided to bake. Bad idea, Rae was the resident chef back in Cali. Besides laughing till your stomach hurt, and almost burning down your kitchen, nothing all that significant happened. Somewhere down the line, at about 3 am, half-way through a cheesy rom-com you had the overwhelming urge to text Corpse.

That’s where the problems really started. God, you missed California, missed being in the same timezone with a guy you hadn’t even met yet, how embarrassing is that?! You missed skating around and taking pictures of the beach in the setting sun, sending it to him, silently wishing he was with you to admire the view.

You really want to call him. And to hang out with him. But for some reason, the thought of that springs up immediate anxiety and you shy away from asking. Him sending you cute good morning texts doesn’t help, either. Maybe it’s better he doesn’t know that you’re a blushing, stuttering mess each time you read “baby”.

Late evening. Your stream is already set up, people are slowly trickling in and you greet them with a grin and a soft “Hello! Hi hi!”. You did your best to make your room a perfectly chaotic backdrop - led lights, an embarrassing amount of anime merch and plushies. You always try to balance out your weeb side by dressing hot as fuck for your streams - today’s inspiration just so happens to be egirls. Mostly because you watched one too many egirl make-up tutorials on TikTok, and also because you’ve been listening to Corpse’s song all day.

Yeah, no, who are you kidding, you dressed up this way because you were hoping Corpse was watching your stream. You didn’t forget your cat headphones, either. You know he likes them. You want to make him suffer. Perhaps then, finally, he will ask you out, so you wouldn’t have to.

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

“I feel like,” You start when you put away your phone, staring idly at the chat, “I feel like I need a new name for you guys. Calling you guys after two years of streaming is just... weird, no? I also don’t respect men so I don’t want to call you guys. Like, so many creator’s have, like, a name for their fans. Uhm, Cody Ko has the chodesters, Kurtis Conner has, uh, folks? Kurtis Town? Citizens! Markiplier has mommy issues--” You can’t help snorting, “So, I’ve been, like, thinking - I know, shocking! - so I was thinking I’m gonna name you cockroaches. Because you’re grimy little shits impossible to kill. And also then I can use the legendary Minaj meme ROACHES!”

Your stream enthusiastically echoes ROACHES, making the chat swim. Yes, if anyone would enjoy such a name, it would be your audience. You’re as equally proud as you are disturbed.

“Well, anyway.” Leaning back into your chair, you throw your arms out with a bright grin, “Big dick is back in town, baby! If you noticed the backdrops different, it’s cuz I’m in Brooklyn now. Don’t ask me when I will return to Always Sunny, I don’t plan that far ahead.”

While Minecraft boots up, you decide to answer a few questions.

r u dating sykkuno?

You want to smack your head into the keyboard, but as it is, you can’t exactly afford a new one, so you refrain, “No, Sykkuno and I are not dating, we are just good friends. Uhm, I’m not sure how much I’ll have to repeat this, but, we really aren’t, so if the roaches could chill - Oh my God, that sounds so stupid, I love it - uh, yeah, if the roaches could chill that’d be great.”

the roaches lmao sounds like we’re a sports team

“Oh shit, yeah it does, uh-- maybe I can make like, jerseys or something. That’d be cool, I think.”

how disappointed are your parents with the way your life turned out?

“My parents are actually not disappointed at all!” You say with a cute little smile, “Uhm, they’re both really proud, actually. They’re glad I found something I love doing and made a job outta it. Dad finds my Youtube videos endearing. Yes, they watch pretty much all of my videos, unless I explicitly tell them not to. And yeah, with all the fucks and thirsting for anime characters. Uhm, it was very embarrassing at first, but I mean, after a while, shame just...doesn’t exist anymore, I guess? Funny thing about my parents, actually, when they watch my videos-” You eye catches a comment, “Oh! No, they only watch my Youtube videos. They don’t know how to use Twitter, thank God. Uhm, anyway-- when they hear a name they don’t know, like, I dunno, Dabi, or something, they google--” You’re grinning by now, eyes crinkling, giggling softly, “--who that is, and buy me like, merch and stuff. It’s really cute.

can i be adopted by ur parents plz

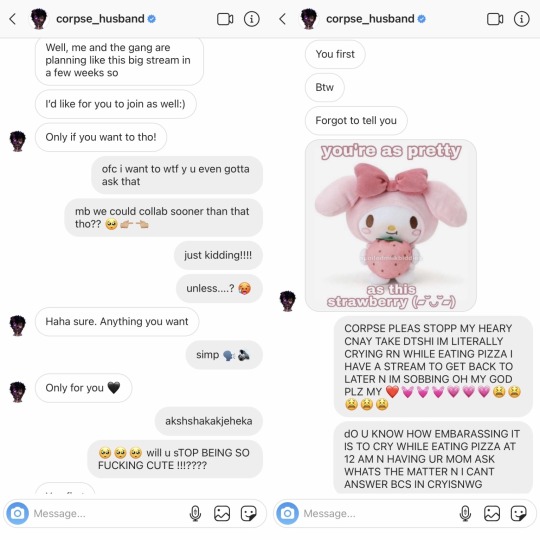

will you and corpse ever collab?!

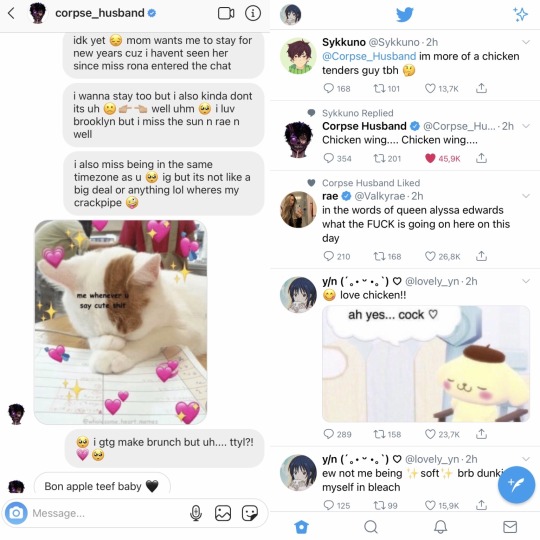

You were about to answer, though the man of the hour himself decides to do it for you.

Corpse_Husband: yes.

Okay, not to say your heart skipped a beat, but it totally did. With a pleased smile, you nod, like one of those bobble head toys sold at the dollar store. The motion is oddly reminiscent of Sykkuno’s own nod. Perhaps you had picked it up from him. The chat seems to notice.

pack it up, sykkuno

More questions pile about this mysterious collab you and Corpse are planning. Yeah, you’d like to hear more about it, too, since he single highhandedly decided one was happening right now. Corpse remains silent. Fine, keep your secrets.

“Okay, guys, oh, I mean, roaches, Oh my God--” You’re covering your mouth, giggling, “-calling all roaches, calling all roaches, calm down. Everyone grab a snack and a blanket I’m turning up the music volume so we can all chill. Entering chill zone. Entering chill zone. Roaches, prepare.”

we are prepared

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

An hour or so passes and you grow hungry. It shows with the amount of cakes you had baked in your server. Currently, you find yourself throwing eggs at the wall of one of the renovated houses, your face scrunched in concentration and slight frustration. 24 of the 50 eggs have been wasted. “What’s a girl gotta do to get some chicks around here?” you had uttered under your breath, until, finally, a screech - the egg finally spawns a mob. Your mouth falls open, “Aww, look!” You approach it, so small, walking in zigzags beside you, “It’s a baby chicken! Die, bitch.” The baby chicken is no more as you swing your bedazzled (you have mods) diamond sword. You’re cackling by the time the dust settles.

y/n is a child murderer

“Roaches,” You address your fan-base, spurring another fit of laughter - you can’t get over the name, “I think I’m like, forgetting that eating in Minecraft won’t actually make less hungry in real life.”

take a break and go eat queen <3

“Fuck no, we starve and die like men. Now I actually really need another chicken.”

Another twenty minutes trickle by and you’re trying to lure back a panda from the jungle when there’s a knock on your bedroom’s door. Whipping your head to the side, you slide down your headphones. At the same time, your mom pokes her head through the ajar door, “MOM!” You scream, “Get OUT of my room I’m playing Minecraft!” But your yell has no actual bite to it, as you don’t manage to hide your smile. Your mom laughs, doing some sort of sign language and motioning for you to follow her with her head. That or it’s some sort of performative dance.

“I’m live right now,” You tell her, pointing at your screen. She knows this already, though, “do you want to say hi?”

The roaches spam the chat with friendly hellos. You mom, quite impatient now, waves you over.

“Sorry, roaches, mom needs something. Be back in a bit!”

Stopping the stream, you rush out of your seat and pleased she slinks into the hallway. “What’s this about?”

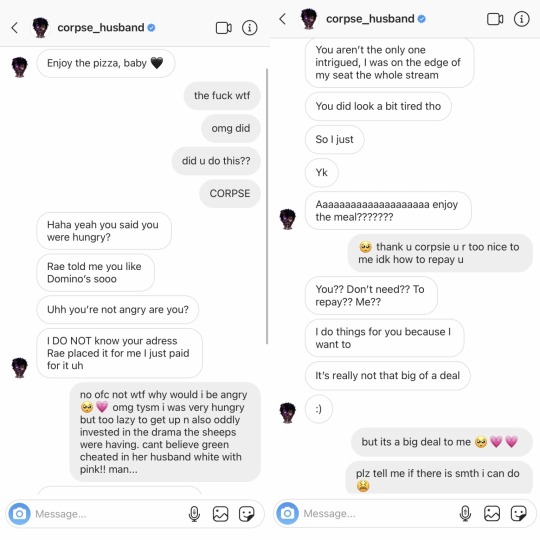

“Your pizza came.”

“My what now?” You echo, confused.

“Domino’s. You ordered pizza?”

“What? No? I was busy with the stream, I never--”

Thankfully, you had managed to grab your phone from your room before you exited. You almost choke on spit once you read the messages.

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

You decide that it’ll be impossible to stream after experiencing what you had just experienced. You tweet out a quick apology to the roaches (God, that fucking name) and say that you had a breakdown but you’re okay. That is as a close to the truth as you managed to muster. It’s a sad sight, chewing and crying; your mom winced when she saw your state - disheveled hair and rundown eyeliner and everything. “D’aww,” She had muttered, caressing the top of your head, “don’t cry my little raccoon.”

If anyone was ever to ask you where did your chaotic nature come from, you’d answer with my mom. To make yourself feel better, you took a selfie - duck face and peace sign and the horrible 2000′s angle. Sent it to Rae.

looking hot, her message read.

thanks, was all you replied with.

You couldn’t just leave things as they were. Once you calmed down, you wanted to text Corpse, but how would you follow up the ungodly caps lock and screeching? Impossible. An idea sprung to mind, one that was brave. Taking the first step.

Instead of sending a text, you sent a voice memo.

“Thank you for the pizza, it was delicious.”

You voice still sounded a bit raspy. His reply was instant. Your heart skipped a beat. He sent a voice memo back.

“Glad you liked it, baby.”

He was going to be the death of you.

✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼ ҉ ✼

tags (in italics is those i couldn’t tag! make sure all’s ok w your settings!) : @littlebabysandboxburritos - @fairywriter-oracle - @tsukishimawh0re - @ofstarsanddreams - @bbecc-a - @annshit - @leahh19 - @letsloveimagines - @bellomi-clarke - @wineandionysus - @guiltydols - @onephootinfrontoftheother - @liamakorn - @thirstyfangirl - @lilysdaydreams - @pan-ini - @mxqicshxp - @tanchosanke - @yoshinorecommends - @flightsandfantasy - @liljennyx3 - @slashersdream - @unknown-and-invisible - @sinister-sleep - @fivedicksinatrenchcoat - @mercury–moon - @peterparkerspjsuit - @unstableye - @simonsbluee - @shinyshimaagain - @ppopty - @siriuslystupid - @crapimahuman - @ofthedewthesunlight - @mythicalamphitrite - @artsyally - @corpsesimpp - @corpsewhitetee - @corpse-husbandsimp - @hyp-oh-critical - @roses-and-grasses - @rhyrhy462 - @sparklylandflaplawyer - @charbkgo - @airwaveee - @creativedogs - @kaitlyn2907 - @loxbbg - @afuckingunicornn - @fleurmoon - @yeolliedokai - @truly-dionysus - @multi-fandom-central707

more tags are in the comments bcs tumblr only allows me to tag 50 people max 💙

#corpse husband#corpse#corpse husband x reader#corpse x reader#corpse husband imagine#corpse social media au#corpse husband fanfic#social media au#corpse husband x y/n#corpse x y/n#corpse husband fic#reader#xreader#imagine#imagines#myso#make you say oh

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Smoke and Iron Reread chapter 22-23

And now we’re back to Morgan. And Annis. There can never be enough Annis.

A hint in the ephemera here that some level of Obscurist talent may be present in everyone. Potentially relevant in Sword and Pen? Talented metalworkers, storytellers, and Medicas are given as examples. Medicas can use the talent deliberately. Some religions also teach that everyone has the talent. Which ones, I wonder?

This text was written in 1733 but not sent to the Black Archives until 1881. Presumably a year when the Library’s control of information got stricter?

Timeline: it took Morgan “weeks” to figure out how her powers were restricted.

If Gregory didn’t write the script in Morgan’s collar, who did?

Obscurists have room service available.

Annis says that Morgan isn’t feeling well. Specifically, she says Morgan can’t keep anything but soup down. Could be feigning a stomach virus or something. But what else is nausea a symptom of? Pregnancy! Feigning pregnancy would be a very nice and sneaky way of getting out of forced breeding.

In addition to mesmerism, Annis knows “a great many obscure and only partly legal things.” Like what, Annis? We want to know what!

Annis is on Team Morgan in part because it’s what Keria would have wanted, and in part because Gregory is an asshole. Really, I think Morgan has underestimated the number of Obscurists who probably feel the same.

So, did Annis order curry just to troll the English girl, considering they were planning to swap plates?

Morgan “nearly choked” on the curry at first, then powers through eating the rest and decides it’s good enough to get used to the heat. She approaches food the same way she approaches everything else: once she has made up her mind, nothing is stopping her.

Sounds like Morgan and Annis spent some time testing Morgan’s drug-limited powers, and Annis has worked out how to make excuses for Morgan if she isn’t feeling well.

Morgan is worried about Jess and Wolfe. Especially Jess, who she fears might get desperate enough to do something stupid. She does not seem to be concerned about the others, so she definitely trusted Anit.

Morgan did not count on Gregory being able to limit her powers, and again we see some fairly harsh self criticism over that: “What kind of conspiracy couldn’t coordinate efforts? One doomed to fail.”

According to Annis, neither Gregory nor Keria could break the wards on Eskander’s room. Eskander did let Keria in to see him when she asked, and he might have given her a key. There’s how visits with young Christopher could have happened.

Eskander and Keria “understood that love was a trap, a weapon that could be used against them.” Is this why Wolfe thinks his parents hated each other? In addition to being privately guarded with each other, they might have put on a public show of fighting to keep the Archivist from learning how much they cared about each other. Kids can be terrible at lying and keeping secrets, so they might have kept up the act in front of him, in addition to any real tensions he witnessed.

Also, gee, I wonder where Wolfe’s aversion to public displays of affection might come from?

Being in the Iron Tower, and hearing about Eskander and Keria, makes Morgan question her feelings for Jess. This is a very understandable response, really.

Morgan imagining Jess, features she probably appreciates about him: ink-stained fingers, his “quiet, odd smile”, intelligence, speed, violence, fearlessness.

Morgan constantly feels afraid. Realistic response to her situation? Or does she have anxiety on top of that?

More Annis thief skills: she has sewn smuggling pockets into her robes.

The air processing hub is on the 12th floor and Eskander’s room is two floors away, so either 10th or 14th. The library was on the 7th. There is a department on the 4th making the linked crystals.

Apparently, the Artifex department regularly sends ideas to the Obscurists that don’t work. Or at least, that Annis thinks don’t work. How much of this is bad design and how much is coverup of things that work that the Artifex doesn’t want people to know about? What could Obscurists and Artifexes accomplish together if they could actually collaborate without all of the Library’s limitations? I want some Morgan-Thomas collaboration, dammit!

At first it was Morgan reluctant to trust and seek allies. Now she’s realized she needs to work with others, and Annis is the one getting nervous about bringing more people in on their little conspiracy. Annis is a lot like Santi was in Paper and Fire: unhappy with how things are, but afraid of risking the comfortable and (seemingly) safe position she’s created for herself. She’s more easily convinced than Santi was, probably because she only has herself to worry about.

Morgan puts a lot of weight on respecting others’ agency. She’s unhappy about mesmering the servant but justifies it because Gregory was using him too. She cannot justify mesmering the other Obscurists. There’s some immaturity there, that black and white worldview compared to Annis’s pragmatism. Annis has a valid point about the way living in the Iron Tower for a long time would twist a person’s way of thinking. But it’s also a politically savvy move to avoid mesmering any Obscurists: if they find out she’s been mesmering them, they won’t trust her, and she needs to build trust.

Annis on Gregory: “I’ve run circles around that little shite since we were both your age.” So now we officially have conflicting canon on Gregory’s age. Editing error somewhere. Since we have the Wattpad story also putting Gregory’s age the same as Annis and Keria, let’s just conclude that the statement in Paper and Fire is the incorrect one. We can say Wolfe was lying there, if we want to reconcile the whole thing. He always tends to dissemble after showing affection, and he’s not at his best after being dragged through Rome and into the Iron Tower, so he came up with complete obvious bullshit as an excuse for being nice.

Annis is more comfortable with lying to Pyotr than Morgan. Here’s more of Morgan valuing free choice over manipulation.

More Morgan giggling awkwardly at thoughts of Annis’s love life. More Annis expanding Morgan’s worldview. Morgan: “You didn’t have to, ah, promise him...” *can’t even say sex* Annis: I like sex! Morgan: “Do you love him?” Annis: Aromantic and happy that way!

“In the Tower, we’ve never had the luxury of weddings and marriage and growing old together.” Along with the whole Obscurists don’t get married thing, this seems to suggest that matchmaking isn’t a permanent thing. So even Obscurists lucky enough to get matched with someone they like might get broken up by the breeding system.

We have layers of limitations on Morgan here. There’s the drug restricting some uses of her power. Then there’s the Codex monitoring. There’s Gregory watching her. There’s her own body and the changed nature of her power.

Morgan has much more control over her energy draining than she did in Philadelphia. There, she drained the fields without even knowing it. Now, she could theoretically drain small amounts from many sources if not for the tower’s limitations. She can keep herself from draining Annis and Pyotr.

Energy-hungry Morgan has dark streaks on her hands.

How fucking heavy is this garden level? “The earth here went deep.” That’s going to weigh a lot.

Linking the crystals apparently took enough power that Morgan needs to drain a 10-foot circle of garden. She drains the life so completely from everything around her that the soil isn’t fertile anymore. And she still needs more. Or feels like she needs more.

It’s hard to tell here how much of her hunger is genuine need to replenish energy and how much is the nature of her energy vampire state. Does she need more and is denying that need by force of will? Or does she have adequate energy but insatiable hunger because of the corruption?

Morgan can barely walk after draining energy.

Morgan really did try to help the crops in Philadelphia grow. So she was healing Santi, weakening the wall, and helping the crops, all at once. That’s how much it took to push her over into corruption.

Fair point by Morgan that her energy draining isn’t all that different from killing and eating things.

Annis compares Morgan to the devil. Ouch. Understandable, but still not the kindest thing to say to a vulnerable teenager.

Morgan is afraid that if she kills a person by draining them, she will become something worse than what she is. She’s afraid of losing control. That and fear that Gregory would kill her first are what keeps her from draining Gregory.

Morgan’s power corruption is an interesting microcosm of what’s going on in the Library as a whole. She has power, and she sets out to use it for good, but becomes corrupted. She has to fight the draw to descend further into corruption in her efforts to achieve her goals because if she lets the corruption take over, she will become a monster. That’s exactly what happened to the Library, starting out powerful but good and becoming corrupt.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Beth and UARF!Billy

All Hands || -

who wakes up first in the morning

He’s still asleep by the time she makes her way into his office with a small pile of reports from Dr Gates. Mostly because he’d been up until dawn watching the weather patterns out on the open water. She knows because she dragged her board out before the last stars faded into obscurity so that she could catch a few waves before proper sun-up. Sometimes when he sits on the docks with his laptop beside him, staring out at the sea, she swears he looks like he’s dying on the inside.Maybe he is. She would, if she couldn’t go out into the ocean.

who’s the first to fall asleep at night

And he’s still working when she leaves the actual facility a little behind the rest of the crew. There’s a get together over at John’s cottage, and they’re making plans on taking a cutter over to the Big Island for their days off, a rarity at the aquarium. But as much fun as everyone is having, it’s too loud. Too drunk. Too everything for comfort and she finds herself cleverly making off with a plate of appetisers no one is going to miss, and some cokes…because Billy doesn’t drink. Which was why they stopped inviting him.

By the time she makes it back to him with her ill-gotten gains, he’s all bent back and head bowed over his laptop. There’s not a single naked person on the screen; he’s editing video for a virtual symposium on seal reclamation. He barely acknowledges her presence except to mutter something under his breath.And much to her surprise, two quiet hours later, he gestures to the only thing that’s changed; a couch unearthed from the Miocene Graduate School epoch of random texts. There’s what looks suspiciously like a doggie blanket draped on one end, and a pillow that doesn’t match anything, anywhere in the universe.What else can she do but curl into a ball and nap?

what they playfully tease each other over

“Doctah Manderly, can you please pass the salt?”“Doctor Riley, have you double checked your figures? Random unsubstantiated facts…”“Doctah Manderly, not da salt I was aksin’ for.”“Perhaps you should have been more clear, Doctor Riley.”

John can’t roll his eyes any harder. “For fucksake, can you just pass her the condiment tray already?”They glance at each other. He’s almost smiling.

It’s going to be a good day.She never does get the salt, though.

what they do when the other’s having a bad day

It’s unusual not to find him with the seals. It’s even more so to have Annie come trotting up to her, teeth tugging at Beth’s skirts gently. By the time they get back to Billy’s office ~never his…parent’s bungalo, she’s noticed~ he’s curled up on the floor, arms and legs tucked as close to his torso as possible. Eyes squeezed shut. All the lights off until the darkness is a living, breathing thing.Not even his laptop is on.She can see from the sliver of light that penetrates the gloom from the open door that his bottle of tablets is laying on its side on his desk, and he tried to give himself a dose of Keppra. The groan directs her attention back to him and she quickly comes inside, Annie at her vanguard, and closes the door.In the silence she picks her way to him and slides down the front of the couch so she’s sitting next to him. Carefully she cushions his head in her lap and starts rubbing small circles between the atlas and axis of his c-spine. She can’t make his migraines go away, she can’t do anything about the seizures, but she can certainly offer what little comfort she can.

how they say ‘i’m sorry’ after arguments

“Wot’s’ee sayin’?” John asks.Ben narrows his eyes and focuses on Billy’s face. A minute later, the whippet-thin groundskeeper shakes his head and shrugs. Which invariably annoys Silver to no end. The blow out last night had been legendary in its own quiet way.Manderly had stood her up. The celebration of her first article co-chaired with Gates, and Tall-Blonde-And-Anti-social couldn’t be assed to show for the cocktail party and the grant announcement. Flint had slipped out and turned back up empty handed and Miranda…had the pinched face of disappointment twinned with worry.

The rest of the crew had taken bets on exactly how upset Hurricane-Beth had been and what kind of fresh hell Manderly had in-store for him. Silver had a hundred bucks riding on the outcome.~*~“In short… it was unavoidable, and maybe in the future, I could be given more than a day’s notice.”“Yeah, okay.”“You…keep saying that. But I don’t quite believe you.”“Okay.”“Doctor Ri–Eliza—Beth. Would you please look at me?”

“Why?”“Because I’m trying to apologise and it’s very disconcerting having to stare down at you.”“And I’m tryin’a read.”

“And I’m trying to apologise.”“Thank you, William. Apology accepted.”Billy throws his hands in the air and wanders off.

which one’s more ticklish

His hands are warm. They are wide-palmed but slender. Long, clever fingers, tapered at the tip. And they are evil. In one of his rare appearances, Billy is joining the pool party. Sits on the edge of her deck chair. In moving her feet so he didn’t crush them, he absolutely noticed the flinch when his thumb graced the line of her in-step. He tries it again and is rewarded with the most unladylike snort in the whole course of human history. She squirms and writhes and the more she does, the firmer his grip becomes because she doesn’t get to escape, and he’s not about to let her kick him.

Her feet are ticklish.He skims his way a little higher, intent on trying for her knees, now that her legs are laid across his lap. She jerks again. This time though there’s no laughter behind it. As soon as his fingers glide over the scar-tissue she bolts upright. Adjusts the wrap so it covers her from the waist down, over her bikini. The gaze she throws his way is full of hurt and full of malice before she stalks off.He mutters under his breath because once more he’s managed to much things up. There ought to be a precisely indexed and double-spaced codex somewhere detailing the nature of women. He doesn’t understand why everything with her is so hard. They aren’t with seals. They aren’t with Miranda. They aren’t with Annie who leans her head into the side of his leg.

their favourite rainy day activities

It’s the off-season and the facility is down to a skeleton crew. Most everyone’s gone to the Big Island or Oahu or even the mainland for some much needed rest. But Billy isn’t satisfied letting other people take care of his seals, and Beth… as much as they don’t get on sometimes… can’t stand the idea of him staying alone, with virtual strangers even if it IS only for a week.So they follow the same patterns they do every day. Walking the beach with Annie and his seals in tow, feeding treats now and again and she collects shells. They eat together quietly. He spends hours in his office, she keeps company with Dr Gates’ open water tank, daydreaming about swimming with the man-eaters that stop by to visit, and with the others. And the rain comes in the quiet of it all, because of course it does. Beth leaves half her hut open to the elements. It’s the least civilised one of the residences. There’s no real furniture, per se, beyond the bed that takes up most of the room inside, a fireplace, some book shelves, the hammock strung up to the beams, and little touches. Her surf-board in a corner, and a few suitcases that live in a perpetual state of Schrodinger’s packing.

Billy lays across the bed on his stomach, reading an honest to goodness novel. He’s got a blanket bunched up under his chest, his arms. She uses his side the same way and flips through her phone for something by Chopin. Annie’s in her own space, as close to him as she can be.They don’t talk, they don’t really do anything. It’s still the best week, ever.

how they surprise each other

“What is that, even?” Billy stares at the dubious blackened lumps of..oddly flat charcoal.“Pancakes!”“Panca-”“Ya know. Breakfast in bed.” The more he pokes at them with the fork the less amused she looks, the less proud.He’s so going to regret this. And so will Annie. And Gates. And Flint. And anyone else who comes into contact with him afterwards.

He forces himself to chew a bite he’s chisled free. His face strained as he whispers, “delicious.”

their most sickening shows of public affection

It’s the New Season Luau.Some of the staff have dug an imu and there’s an entire pig roasting in its depths not far from the long table covered with other things; local delicacies, people’s family recipes, a mixture of traditional and new. There’s no tourists, no visitors. Just the faculty and workers of the research centre.John and Ben and some of the others are flinging a Frisbee just down the beach in full light of the citronella torches. Miranda and Flint are debating with Gates who is content to trade a bottle with Randall.The night air is balmy and Beth’s standing further apart from the rest, arms wrapped around her bare waist. Billy comes up behind her and drops his chin down on the crown of her hair, breathes in the scent of the plumeria blossom tucked behind her ear, Annie leaning against his leg. He rests his arms over top of her. Pulls her closer into him.

He thinks about asking her to dance.She thinks about letting him.

#nolegacies#The Salt in my Bones|Billy Manderly#No Man's Land|Billy and Beth#Urca Aquarium and Research Facility|A Modern AU#Aloha'aina|Hawai'i

1 note

·

View note

Text

Critically Examining the Case for Book of Mormon Historicity

Preface: This started as a YouTube comment and turned into a much more extended essay, as I had meant to work on such an essay for some time. In case you're inclined to ask why I bothered to write all of this, here's why: for different reasons, I find the ancient Near East, the Bible, ancient Mesoamerica, and Mormon origins to be profoundly interesting, and these subjects converge in discussing with LDS scholars the origins of the Book of Mormon. I've never been LDS and my interest in Mormonism is largely academic, though as a believing Christian I have an interest in engaging Mormonism from an orthodox Christian perspective. For those who are interested in reading through this, I hope it both stimulates your own consideration of these issues and sharpens up your ability to engage credibly with LDS family and friends who use such arguments. This essay considers seventeen arguments made by Dr. John Clark, a well-regarded archaeologist of ancient Mesoamerica.

As a non-Mormon and an interested reader of LDS scholarship (which I enjoy reading in the midst of deep disagreements) , I think that this video provides a good encapsulation of where defenses of Book of Mormon historicity tend to go wrong:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EkF4hlddGfw

The basic model of these arguments for Book of Mormon historicity are that there is a feature of the Book of Mormon text which was unknown or absurd in Joseph's day but which is now confirmed by historians of the ancient Near East and Mesoamerica in our own day. In order to evaluate these arguments, I want to spell out what I take to be important methodological points:

1. The two models we are comparing are a) the Book of Mormon as an ancient Mesoamerican codex engraved by authors of roughly Near Eastern extraction and b) the Book of Mormon as a production of the 19th century, written by author(s) familiar with the then popular ideas about the "Mound Builders." These mounds no longer occasion much interest because most of them have been removed or have been built over. But to persons of Joseph Smith's time and place, the Indian Mounds dotted the landscape and provided observers with much material upon which to speculate. Dan Vogel's "Indian Origins and the Book of Mormon" provides a clear and well-argued defense of this model of Book of Mormon origins.

2. This means that we are not looking at what scholars of ancient America thought in Joseph Smith's day. Then, as today, what academics thought and what was ingrained in the popular understanding were very different things. As LDS scholars often point out, Joseph Smith was relatively unlearned. We would therefore expect a production by Smith or someone associated with him to reflect popular understandings of ancient American civilization rather than academic understandings of that civilization. Hence, to compare what **academics** thought of ancient America in the 19th century with the Book of Mormon is a false trail. Nobody is suggesting that a 19th century scholar of ancient America composed the Book of Mormon.

3. We are not comparing 19th century conceptions of Mesoamerica with 21st century conceptions of Mesoamerica, as nonbelieving accounts for the production of the Book of Mormon do not set its narrative in Central America. Rather, as just described above, the setting of the Book of Mormon according to those who reject its historical authenticity is generally in the North American Heartland, including upstate New York.

These considerations lead us to the most important principle in evaluating claims of Book of Mormon authenticity. If a feature of the Book of Mormon text is found **both** in the ancient world **and** in the popular understanding of Joseph Smith's time and place, then the feature of the text **provides no argument for its authenticity or for its non-authenticity.** Both skeptics and believers of the Book can fall into this trap. In the same vein, we must understand that American culture in the 19th century was far from a monolith. What was believable and normal in 1830 Palmyra might be laughable to a scholar of that period or to a layperson in another area of the country. Thus, that critics once laughed at a feature of the Book of Mormon which has since been found in the ancient world is only significant if the feature was laughable and unexpected in the precise cultural context which enveloped Joseph Smith himself.

Each of the arguments made by Dr. Clark is a point which concerns two worlds. While Dr. Clark is an eminent expert in one of these worlds, in the other, he is merely a layman. The former is Mesoamerica, the latter is 19th century upstate New York. This point must be emphasized, because in several instances Dr. Clark explicitly makes a claim about what was conceivable for "19th century Yankees", with similar claims implied for his other arguments. My argument is that the major failure of his argument turns not on a misunderstanding of Central America (Clark is too much of a scholar to simply have "misconceptions" about Central America), but on a series of failures to grapple with Joseph Smith's own cultural context. Because of the paramount importance of a well-crafted methodology in approaching the question of Book of Mormon historicity, I will be returning to this point again and again in relation to the specific arguments presented by Dr. Clark.

With these points in mind, let's turn to the specific arguments.

1. Metal plates in stone boxes.

The first concerns metal plates sealed in stone boxes. We are told that this claim was thought to be ludicrous in Joseph's time but has since been shown to be authentically ancient. The engraved gold plates of Darius, sealed in a stone box, probably provide the closest analogue to the Book of Mormon plates. But there are serious issues with using this as an argument for the Book's authenticity. First, while engraved metal plates have been found in the ancient world, there has never been a text of the size of the Book of Mormon found- not even close. That a local aristocrat such as Laban had much of the Old Testament translated into Egyptian and engraved on brass plates indicates that the engraving of large records, comprising multiple scrolls, must have been somewhat common in the 6th century BC. The plates that have been discovered provide only a moderate parallel to the description found in the Book of Mormon.

Still, were there no analogue of similar precision found in Joseph Smith's own time and place, this would be a remarkable parallel. However, there are such analogues. The first comes from the surviving Spalding Manuscript, which I use only as an example of what was current in Joseph Smith's background, not as an argument for the Spalding-Rigdon model of BoM authorship. The Spalding Manuscript describes a colony of Roman Christians from the 4th century AD, blown ashore to the American continent accidentally. The internal narrative of the story is that Fabius, the leader of the colony, recorded the history of his people on a document and then sealed it away in a stone box, placing that box inside a cave. Fabius does so in order that the record might come forth and be translated by future Europeans so that they might know the history of Fabius' people. The plates of the Book of Mormon are similarly supposed to record the history of an ancient civilization extracted from the Old World, sealed away in a box with the intention that they should later come forth and be translated so that the later inhabitants of the American continent might know its history. Moreover, testimony from Brigham Young and Oliver Cowdery suggests that the stone box was thought to be hidden away inside a cave filled with records. I am not suggesting literary dependence. Rather, I am pointing out that analogues, even relatively close ones, were indeed present to Joseph Smith in 1830, and that the currency of these ideas indicates that the Book of Mormon's internal account of its sealing in a stone box does not need to be explained in terms of the ancient world: ultimately, it would be a wash.

But what about metal plates? Fabius' account is not engraved on plates of metal. Was this laughable in Smith's context? No, it wasn't. Fawn Brodie (whatever one thinks of her reconstruction of Smith, I refer to her book because of its citation of primary texts) notes that "a Palmyra paper in 1821 had reported that diggers on the Erie Canal had unearthed 'several brass plates' along with skeletons and fragments of pottery." (No Man Knows My History, 35) So, we find that in the cultural world immersing the young Joseph Smith, there are already ideas of records sealed up in stone boxes as well as engraved metal plates, and that these ideas were linked with the Indians, particularly the Mound Builders which forms the setting of the Book of Mormon according to nonbelievers.

So this, at best, is a wash. At worst, the immediacy of the parallel to Joseph's own context and the lack of precise analogues in the Near East (given the length of the record) provides a slight advantage to nonbelieving models for BoM origins. An argument could be made for either, but this is miles away from the slam dunk suggested by Dr. Clark.

2. Ancient American writing

Dr. Clark argues that the Book's description of writing and books in ancient America are exceptionally prescient, given what was then thought of ancient America.

The above examples suffice to show that it was hardly inconceivable in Joseph Smith's world that ancient Americans had writing systems. After all, the fundamental idea undergirding popular ideas about the Mound Builders was that the Mound Builders represented a lost civilization of basically Old World extraction, having all the sophistication known from the Old World, but wiped out by the ancestors of the American Indians known in the 19th century. The Book of Mormon provides a particular spin on this narrative, but it is recognizable as a form of the narrative. So, given the Book's situation in this narrative world (according to those of us who don't believe the Book is historically authentic), it is entirely reasonable that writing systems should be described. And since nobody is alleging that Joseph produced the Book based on an academic understanding of Mesoamerica current in his day, Clark's comparison of the BoM with the scholarly knowledge in 1830 is a false one. However ludicrous ancient American writing might have been to the scholars of 1830, Joseph Smith wasn't acquainted with their ideas, but with the ideas of those for whom ancient American writing was to be expected.

There is thus a close analogue in both the world of Joseph Smith and in ancient Mesoamerica, if one is simply considering the presence of written language. Given that the writing systems of ancient Mesoamerica are not presently related to any Old World writing system, the parallel to the Book of Mormon is quite vague, as the latter describes writing systems derived from Hebrew and Egyptian. So the parallel is merely in the concept of written texts- hardly precise enough to be striking.

3. Ancient American Warfare

Dr. Clark describes the notion of warfare in ancient America as having been "ridiculed" in the Book of Mormon until about twenty years ago. But as before, the question concerns the source of that ridicule. Would a person in Joseph's environment ridicule the idea of wars of extermination among the ancient inhabitants of the Americas? Certainly not. This was the basis for the mythos of the Mound Builders- that the creators of the advanced civilizations of ancient America were savagely wiped out by the ancestors of the Native Americans known to Joseph and his contemporaries. These immense wars of genocide were then seen to explain the ubiquity of the mounds heaped up with the remains of ancient inhabitants of the continent. The Book of Mormon contains a number of passages suggesting its origin, in part, as an etiology of these mounds, where the bones were visibly heaped up almost immediately under the surface:

Alma 16:11: "Nevertheless, after many days their dead bodies were heaped up upon the face of the earth, and they were covered with a shallow covering."

Alma 28:11: "And the bodies of many thousands are laid low in the earth, while the bodies of many thousands are moldering in heaps upon the face of the earth; yea, and many thousands are mourning for the loss of their kindred, because they have reason to fear, according to the promises of the Lord, that they are consigned to a state of endless wo."

Mormon 2:15: "And it came to pass that my sorrow did return unto me again, and I saw that the day of grace was passed with them, both temporally and spiritually; for I saw thousands of them hewn down in open rebellion against their God, and heaped up as dung upon the face of the land. And thus three hundred and forty and four years had passed away."

Ether 11:6: "And there was great calamity in all the land, for they had testified that a great curse should come upon the land, and also upon the people, and that there should be a great destruction among them, such an one as never had been upon the face of the earth, and their bones should become as heaps of earth upon the face of the land except they should repent of their wickedness."

Even apart from the link between the Mound Builder mythos and the Book of Mormon, bloody wars with Native Americans were a matter of living memory and direct knowledge for contemporaries of Joseph Smith's. This is one place where I am genuinely mystified by Dr. Clark's assertion. Why would anybody in Joseph Smith's environment be surprised that he describes ancient Americans as fighting wars?

4. Nature of Civilization

Dr. Clark states that the account of ancient American civilization differs markedly from what Joseph would have expected from his own knowledge of the American Indians and their culture, But this misses the point in a crucially important way. The Mound Builder mythos itself arose as an explanation for an apparent discontinuity for the high civilization evident from the mounds and the perceived low culture of the Native Americans of the 19th century. As wrong as Rodney Meldrum is, he and his compatriots have played a helpful role in reminding everyone that there is evidence of civilization in North America, with highways, fortifications, and the like. In their efforts to demonstrate that "Joseph knew" the setting of the Book of Mormon in the Heartland of North America, they have also provided extremely helpful documentation showing that this evidence of civilization was known to Joseph and his contemporaries.The important point is that these features were immediately apparent in Joseph Smith's own day, as the mounds which have now been eradicated or built over were visible to the naked eye and well-known as a feature of the landscape.

[As a minor footnote, even if these things were not known to Joseph and his contemporaries, anyone describing an ancient civilization of Old World extraction would draw features known from Old World cultures, which is particularly predictable for a narrative like the Book of Mormon, anchored in the detailed information given about ancient Israelite civilization.]

According to the Mount Builder mythos, the architects of the great civilization evident in the Mounds were wiped out by the ancestors of the Indians known to 19th century Americans. In the Book of Mormon, this position is neatly filled by the Lamanites, cursed with a red skin (which is at the very least the strong prima facie evidence of the BoM text) and identified as the forefathers of the Indians. 2 Nephi 5:24 serves as an etiology for the perceived low culture of these Indians:

2 Nephi 5:24: "And because of their cursing which was upon them they did become an idle people, full of mischief and subtlety, and did seek in the wilderness for beasts of prey."

Enos 1:20 provides an even clearer example:

Enos 1:20: "And I bear record that the people of Nephi did seek diligently to restore the Lamanites unto the true faith in God. But our labors were vain; their hatred was fixed, and they were led by their evil nature that they became wild, and ferocious, and a bloodthirsty people, full of idolatry and filthiness; feeding upon beasts of prey; dwelling in tents, and wandering about in the wilderness with a short skin girdle about their loins and their heads shaven; and their skill was in the bow, and in the cimeter, and the ax. And many of them did eat nothing save it was raw meat; and they were continually seeking to destroy us."

And see also:

Mormon 6:9: "And it came to pass that they did fall upon my people with the sword, and with the bow, and with the arrow, and with the ax, and with all manner of weapons of war."

The red-skinned Lamanites are noted for their association with the bow and the axe- both well known associates of Native Americans known to Smith, whose favorite weapons were the bow and the tomahawk axe. I'm not sure when the teepee became a stereotype for Native Americans in general, but if it was present in Smith's day (I'm working to confirm or deny its presence), then the notation about the tents provides another specific convergence to Smith's background and context. The reference to the shaven heads likewise hits the mark for the Native Americans known to Smith, for whom a partially or entirely shaved head was a common hairstyle. And the reference to loincloths is easily accounted for in terms of the "breechcloth" which was common to most Native American tribes and would have been immediately known to Smith and his contemporaries. Thus, while the Nephites (and righteous Lamanites who are turned white- thus suggesting a path of redemption for the Natives known to Smith) are described in terms of civilization familiar to the Old World, the Lamanites who are the ancestors of the American Indians known to Smith (in the unbelieving model of Book of Mormon origins) are described in a way which immediately rings true with what was thought in the 19th century. I don't write this to attack Smith or his contemporaries for believing this, but simply to note that the Book of Mormon resembles almost precisely what one would expect from a text drawing on the Mound Builder mythos.

5. Weapons and Armor

Dr. Clark then states that the description of Book of Mormon weapons and armor converge unexpectedly and specifically with ancient Mesoamerica. As evidence for the historicity of the Book of Mormon, this point cannot prove very much, since the weapons described are easily explained as a result of a) a biblical history of ancient America mirroring biblical warfare, where all of the mentioned weapons and armor are described and b) knowledge of weapons used by Indians of the 19th century and found in Indian Mounds. The latter accounts for the peculiar prominence of the axe (tomahawk) and bow in relation to the Lamanites, who are linked with the Native Americans of the 19th century on the non-historical model of Book of Mormon authorship.

5a. Excursus on Metals in Mesoamerica

By itself, then, the presence of these weapons is neither an argument for or against the Book of Mormon, as their textual presence can be explained both as an authentic Mesoamerican history and as a projection of biblical warfare. However, when further detail is considered, the weapons described point away from Book of Mormon historicity and towards a 19th century origin. First, as mentioned above, the weapons associated with the Lamanites are suggestive of a 19th century cultural background. Second, and more seriously, while most references to Book of Mormon weapons and armor are nondescript concerning their makeup, those details which do exist each point towards a metallic origin. No reader of the Book of Mormon without knowledge of ancient America would have any reason to suppose that they were made of anything else- on "bloodstains" see below. Evidence of metallurgy in Mesoamerica during Book of Mormon times is slim to nonexistent. It is important to distinguish metallurgy from the use of metal. John Sorenson has plausibly noted linguistic and some archaeological evidence for the use of metals in Central America during Book of Mormon times.

However, as Deanne Matheny points out:

"It is important to distinguish between metalworking, 'the act or process of shaping things out of metal' and metallurgy, the 'science and technology of metals' which may involve such processes as smelting, casting, and alloying." ("Does the Shoe Fit" in "New Approaches to the Book of Mormon", p. 283)

The Book of Mormon is very clear that the Lehites and the Jaredites possessed advanced metallurgical technology. Not only does the text describe tools (such as swords fashioned after Laban's model) which can only be produced by metallurgy, it makes explicit references to metallurgy. "Dross" is used as a metaphor in both Alma 32:3 and 34:29. The latter is placed in the mouth of Alma himself, preaching to the people and saying "if ye do not remember to be charitable, ye are as dross, which the refiners do cast out, (it being of no worth) and is trodden under foot of men." This comment is immensely significant in evaluating the presence of metallurgy in the Book of Mormon, because its use as a metaphor indicates that it must have been common enough for the average person to understand. Hence, in the society described, metallurgists would play an important economic and civic role, and given the intelligibility of the metaphor, it would be strange if Book of Mormon civilizations did not use their knowledge of advanced metallurgy to produce metal weapons and armor, as such implements would provide a decisive advantage in war with those cities which did not use metallurgical technology.

Helaman 6:11 explicitly describes the extent of metallurgy at this point in Book of Mormon history: "And behold, there was all manner of gold in both these lands, and of silver, and of precious ore of every kind; and there were also curious workmen, who did work all kinds of ore and did refine it; and thus they did become rich."

Helaman 6:9 describes the geographical extent of this knowledge: "And it came to pass that they became exceedingly rich, both the Lamanites and the Nephites; and they did have an exceeding plenty of gold, and of silver, and of all manner of precious metals, both in the land south and in the land north."

Thus, in the first century before Christ, advanced metallurgy is known among both Nephites and Lamanites and is prominent throughout the entirety of the lands described in the text. Given the vast extent of this knowledge- in both land northward and land southward, among both Nephites and Lamanites, among both rich and common (as evident in its intelligible metaphorical application)- it would be totally unexpected for this knowledge to simply pass away, as some Book of Mormon scholars have suggested occurred. Metallurgy is an important enough technology that once it is established on a large scale, it will not be forgotten by accident.

2 Nephi 5:14-15: And I, Nephi, did take the sword of Laban, and after the manner of it did make many swords, lest by any means the people who were now called Lamanites should come upon us and destroy us; for I knew their hatred towards me and my children and those who were called my people. And I did teach my people to build buildings, and to work in all manner of wood, and of iron, and of copper, and of brass, and of steel, and of gold, and of silver, and of precious ores, which were in great abundance.

The close textual conjunction of the making of swords like Laban's sword and the description of metallurgy strongly mitigates against an interpretation which suggests that the swords were like Laban's in form but not in their metallic constitution. 1 Nephi 17:10-11 describes the process of Nephi's metallurgical knowledge, where ore is mined, refined through the use of bellows as smelting tools. The emphasis placed on the working of various metals suggests that they must have been of supreme importance in Book of Mormon societies. Indeed, the use of metal seems to be a literary motif that runs throughout the Book, as signified in its engraving on a book of metal plates.

Jarom 1:8: And we multiplied exceedingly, and spread upon the face of the land, and became exceedingly rich in gold, and in silver, and in precious things, and in fine workmanship of wood, in buildings, and in machinery, and also in iron and copper, and brass and steel, making all manner of tools of every kind to till the ground, and weapons of war -- yea, the sharp pointed arrow, and the quiver, and the dart, and the javelin, and all preparations for war.

The text here links the use of metallurgical "machinery" with the making of both agricultural tools and weapons of war. Such would be expected from a projection of Old World civilization as known from the Bible, but would be manifestly unexpected as a description of an ancient Mesoamerican civilization.

Ether 7:9: Wherefore, he came to the hill Ephraim, and he did molten out of the hill, and made swords out of steel for those whom he had drawn away with him; and after he had armed them with swords he returned to the city Nehor and gave battle unto his brother Corihor, by which means he obtained the kingdom and restored it unto his father Kib.

Here, almost at the earliest point in Book of Mormon history, we are told of metal swords being produced by metallurgy in ancient America.

Ether 10:23-27: And they did work in all manner of ore, and they did make gold, and silver, and iron, and brass, and all manner of metals; and they did dig it out of the earth; wherefore they did cast up mighty heaps of earth to get ore, of gold, and of silver, and of iron, and of copper. And they did work all manner of fine work. And they did have silks, and fine-twined linen; and they did work all manner of cloth, that they might clothe themselves from their nakedness. And they did make all manner of tools to till the earth, both to plow and to sow, to reap and to hoe, and also to thrash. And they did make all manner of tools with which they did work their beasts. And they did make all manner of weapons of war. And they did work all manner of work of exceedingly curious workmanship.

Several centuries later (during the time of Kish and Lib) in Jaredite history, metal is a central feature of Jaredite civilization, and the mining of ore and its refining into metal is described in the context of agricultural tools and weapons of war. The phrase "exceedingly curious workmanship" is also generally used of metallic implements in the Book of Mormon.

At the very latest point in Book of Mormon chronology, Moroni indicates that metallurgical knowledge was available to him in Mormon 8:5: "Behold, my father hath made this record, and he hath written the intent thereof. And behold, I would write it also if I had room upon the plates, but I have not; and ore I have none, for I am alone."

If ore were available, the text clearly implies, Moroni had the skills necessary to extract the necessary metals and make additional plates. Thus, metallurgy is in evidence from almost the beginning of the Jaredite history to the exact end of the Lehite history. Moreover, it is not presented as an ancillary feature of Book of Mormon civilizations. Rather, metallurgy is presented as central to the economies of both Nephite and Jaredite peoples. It is described in conjunction with the creation of agricultural and military implements during both the Jaredite and Lehite periods. War and food are twin pillars of any ancient society, including ancient America. It was known at the beginning, middle, and end of the Lehite period, with its use spanning the entirety of Book of Mormon lands and both Nephite and Lamanite branches of the nation.

Evidence for metallurgy during this period in Central America is basically absent. I say "basically" only to leave open the possibility that I have missed the publication of marginal evidence for metallurgy during the appropriate period. However, as far as I know, the first evidence for metallurgy in Mesoamerica comes around 700 AD. Before this period, the only evidence for pre-Columbian metallurgy is in ancient Peru, which is not relevant to Book of Mormon lands on the standard Mesoamerican geography. What is remarkable is the absence of the evidence in Mesoamerica during Book of Mormon times when its presence is clearly known in Central American archaeology from 700 onwards, especially in light of the centrality of metallurgy to Book of Mormon civilizations.

While it is always possible that evidence for metallurgy will be forthcoming in the future, as long as one is speaking of the present state of the evidence, one is faced with the complete absence of archaeological evidence for one of the most central features of Book of Mormon civilizations for the entirety of its timeline of two and a half millennia. Given the appearance of such evidence several centuries after Mormon's death, this is evidence that one would expect to see if the Book of Mormon were truly an ancient Mesoamerican codex. But it is missing.

Back to Weapons and Armor

I spent so much space discussing the issue of metallurgy because of the centrality of warfare to Book of Mormon history and the importance placed on the convergence between Book of Mormon history and ancient America in this respect by Dr. Clark and other LDS scholars. Below I will return to the issue of specific weapons and the nature of the convergence with Mesoamerican evidence.

5b. Breastplates:

Breastplates are described several times in the Book of Mormon, and are known from ancient America. However, the one time that the makeup of a breastplate is identified, we are told that it is of brass and copper, referring to Jaredite armor brought to King Mosiah:

Mosiah 8:10: And behold, also, they have brought breastplates, which are large, and they are of brass and of copper, and are perfectly sound.

5c. Swords:

Ether 7:9: Wherefore, he came to the hill Ephraim, and he did molten out of the hill, and made swords out of steel for those whom he had drawn away with him; and after he had armed them with swords he returned to the city Nehor and gave battle unto his brother Corihor, by which means he obtained the kingdom and restored it unto his father Kib.

1 Nephi 4:9: And I beheld his sword, and I drew it forth from the sheath thereof; and the hilt thereof was of pure gold, and the workmanship thereof was exceedingly fine, and I saw that the blade thereof was of the most precious steel.

2 Nephi 5:14: And I, Nephi, did take the sword of Laban, and after the manner of it did make many swords, lest by any means the people who were now called Lamanites should come upon us and destroy us; for I knew their hatred towards me and my children and those who were called my people.

Mosiah 8:11: And again, they have brought swords, the hilts thereof have perished, and the blades thereof were cankered with rust; and there is no one in the land that is able to interpret the language or the engravings that are on the plates. Therefore I said unto thee: Canst thou translate?

Thus, when it comes to swords, the only textual evidence for the composition of swords in the text of the Book of Mormon is that they are metal. Dr. Clark, however, argues that there is evidence for non-metal swords in Alma 24, where the swords are described as having the ability to be stained with blood.The first thing to point out is that the text describes the swords, after having been cleansed, becoming "bright", an adjective which makes far more sense in reference to a clean metal sword which shines in the sunlight than it does to a wooden sword. Second, the use of "bloodstained" in reference to swords provides little evidence that the swords were anything other than metal, as "bloodstained" is used of metal swords in the parlance of Joseph Smith's day.

To give just one example (searching Google Books produces a good number of examples) from 1825, Augustin Thierry's "History of the Conquest of England" (p. 127) describes a "bloodstained sword." Language of staining with blood is frequently metaphorical- one says that one has bloodstained hands if one is guilty of murder, not because the skin on one's hand has reddened permanently. Given, then, that this phrase was attested in Joseph Smith's day when speaking of metal swords, one cannot take this as evidence that the swords are anything other than metal. Of course, it's possible, given the constraints of the text, that some of the swords described could be made of something other than metal. But there are a number of passages which clearly describe metal swords, and there are no passages which clearly describe a non-metal sword. There are no hermeneutical grounds for assuming that every sword in the text refers to a non-metal sword unless it specifically states otherwise. Such an interpretation must be brought to the text on the basis of Mesoamerican archaeology, in which case the strength of an independent convergence between the text and the evidence disappears.

Evidence for metallurgy in the appropriate time periods is presently lacking, and the Book of Mormon text needs to be supplemented by conjecture to bring it into line with the archaeological evidence. Thus, the picture that Clark paints of a specific convergence between the Book of Mormon text and Mesoamerican civilization of the appropriate time period is exaggerated at best. At a deeper level, however, this point reveals the profound discordance presently existing between Mesoamerican archaeology and the Book of Mormon. Throughout the text, metallurgy is presented as widely known and centrally important for agriculture, warfare, and trade. With regard to the specific issue of weapons, the convergence suggested by Dr. Clark is actually a substantial discordance, for the weapons known from ancient Mesoamerica are not made of metal, while the only indications provided in the text are for metal weapons and armor, along with a substantial metallurgical industry. This must be regarded as a substantial argument against the historicity of the Book of Mormon- a major textual feature permeating the whole narrative which is entirely absent from the appropriate time and place.

5d. Cotton Armor

Dr. Clark briefly mentions cotton armor as a convergence between the Book of Mormon and ancient Mesoamerica. Such a convergence, as something not present in the Bible nor (to the best of my knowledge) to the Indians of Joseph Smith's day, would be exactly the kind of convergence which is striking. But it is not present, as Dr. Clark suggests, in the Book of Mormon text. On screen, Alma 43:19 is cited, which refers to the "thick clothing" of the Nephite armies. At most, this is a vague convergence rather than a specific one as cotton is not mentioned. However, a better textual explanation for this feature can be found. I discussed above the description of Lamanites as wearing loincloths and its connection with the "breechcloths" widely known among the Indians of Joseph Smith's day. This is described in the text as one of the features differentiating the civilization of the early Nephites with the wildness of the Lamanites, who are nearly naked, live in tents, and subsist on uncooked meat. Here, in Alma 43, we see Nephite and Lamanite soldiers clashing, and the differences between the two cultures (the stereotypical contrasts present in the Mound Builder mythos) is drawn into focus. In Alma 43:20, we are told about the Lamanites who see the Nephites with their armor and "thick clothing":

"Now the army of Zerahemnah was not prepared with any such thing; they had only their swords and their cimeters, their bows and their arrows, their stones and their slings; and they were naked, save it were a skin which was girded about their loins; yea, all were naked, save it were the Zoramites and the Amalekites"

This text is very similar to the above-cited text concerning the initial wildness of Laman's people. We are told of their typical weapons of warfare and their near-nakedness except the "skin which was girded about their loins." The meeting of these armies thus provides a glimpse at the sharp difference between the civilized Nephites and the wild Lamanites who explain the perceived savagery of 19th century Native Americans. The reference to "thick garments" then, is explained best as a contrast between the near-nakedness of the Lamanite army with the sophistication and civilization of the Nephite army. While it is possible, given the constraints of the text, that it refers to cotton armor, the literary contrast is sufficient to explain why "thick garments" are described, so that absent any additional evidence (which is not, as far as I can see, present), it is an unjustified leap to identify characteristically Mesoamerican cotton armor in the Book of Mormon text.

To sum up this most important section, there is nothing that I can see in the textual description of Book of Mormon implements of war that is convergent with ancient Mesoamerica in a way that is discordant with Joseph's own context. On the other hand, there are major discordances between present knowledge of Mesoamerica and the Book of Mormon- discordances which are convergent with Joseph's own context.

6. The Use of Severed Arms as War Tribute to the King

Dr. Clark next turns to the story of Ammon and the presentation of severed arms to King Lamoni as evidence of a convergence with ancient Mesoamerican war practice, which is said to include the presentation of severed arms as a traditional feature of warfare. However, the documentation provided about ancient America is too vague to make this a strong convergence. This article cites the specific sources underlying this argument:

https://knowhy.bookofmormoncentral.org/content/why-did-the-servants-present-lamoni-with-the-arms-of-his-enemies

In this case, two sets of parallels are cited. The first set comes from the ancient Near East, but the parallel concerns merely the severing of any body part as a war trophy, including heads, arms, hands, or legs. This practice is attested in the Bible, obviously available to Joseph Smith, and does not apparently include the ritual presentation of the severed body parts to the king. From ancient America, Izapa Stela 25 is cited, which is mythological in nature. It shows two heroic twins in a fight with Seven Macaw. When one attempts to grab Seven Macaw, Seven Macaw tears off his arm and hangs it over a fire. Here, the only parallel is in the tearing off of an arm, hardly specific enough to require situating the Book of Mormon in the ancient world. And while the authors state that the story "likely reflects actual Maya attitudes and practices in war and conflict", no specific evidence for this practice is described. The other example cited comes over a thousand years after the close of the Book of Mormon and refers to the Aztecs throwing severed limbs of Spanish soldiers at the Spaniards to taunt them. In addition to the chronological gap, there is no evidence that this was an established ritual among Mesoamerican civilizations, and the severed limbs are used to taunt enemy soldiers and strike terror into them rather than being ritually presented to the king.

Ultimately, then, there is no specific evidence that the practice described (once) in the Book of Mormon was a ritual practice in ancient Mesoamerica. Alma 17 describes Ammon's enemies "lifting their clubs" against Ammon, who cuts their arms off. The image which one is supposed to derive from this is of a number of soldiers attacking Ammon all at once, who is so skillful in battle that as soon as one raises an arm against him, he slices the arm off, and within moments, he swiftly maneuvers to cut another arm off in the same way. Thus, the severed arms are significant in that they particularly reflect Ammon's valor and skill in warfare and his ability to decisively win an engagement in which he is significantly outnumbered. The peculiarities of the text are explained in terms of the literary purpose of the story. As above, this does not rule out ancient Mesoamerican context, but absent more specific evidence, hypothesizing such a context is unnecessary to explain the text's production and thus does not indicate an anomaly in a model of 19th century authorship requiring the Book's ancient authenticity as an explanation.

7. Towers as a Place of Final Surrender

Dr. Clark then turns to the scene described in Moroni 9, where Mormon narrates the Lamanites' taking prisoners from the tower of Sherrizah. This, he argues, reflects the ancient Mesoamerican practice of fleeing to the tower/pyramid (the two are used interchangeably in the Bible and thus reasonably so in the Book of Mormon) as places of last defense and surrender. While he may have additional evidence for this practice, the only evidence he cites is the fact that broken or burning pyramids are a symbol of a city's conquest in Mesoamerican art and iconography, which is vaguer than the specific convergence being cited. More importantly, however, the notion of the tower as a place of last refuge is present in the Bible and thus directly available to Joseph Smith:

(Judges 9:50-52) Then Abimelech went to Thebez and encamped against Thebez and captured it. But there was a strong tower within the city, and all the men and women and all the leaders of the city fled to it and shut themselves in, and they went up to the roof of the tower. And Abimelech came to the tower and fought against it and drew near to the door of the tower to burn it with fire.

While Abimelech is then unexpectedly killed, the story closely resembles the story in Moroni 9, where women and children had apparently fled to a tower at which they were defeated and captured. Since this textual feature was available to Joseph Smith, it cannot provide evidence for an unexpected convergence with Mesoamerican civilization at a point which diverges from Joseph's time and place.

8. Human Sacrifice and Cannibalism

Clark briefly mentions human sacrifice and cannibalism as a convergence between the Book of Mormon and ancient Mesoamerica. This is true, but both were also present among the North American Indians with whom Joseph and his contemporaries were familiar. North American Indians were often especially reviled because of the exquisite ritual torture exacted by some tribes upon captured European settlers. Likewise, while the evidence for cannibalism among North American Indians has been controversial, there is no question that Europeans who encountered them believed them to have practiced cannibalism, as is documented among early Jesuit encounters with the Iroquois. As above, then, since the feature is present both in ancient Mesoamerica and in Joseph Smith's world, it cannot provide an argument for either as the source of the Book of Mormon.

9. Large Troop Numbers

Both the Book of Mormon and ancient Mesoamerica featured large battles, but such large battles were also believed necessary to explain the heaps of human bones found throughout North America, so the presence of large armies in the Book of Mormon provides no specific evidence for either time period as the Book's production context.

10. Large Structures Such as Temples and Palaces

This was discussed in #4 above. Far from being "foreign to the gossip along the Erie Canal" as Dr. Clark suggests, the known presence of an advanced civilization in ancient North America was the foundation for popular speculation about the Mound Builders which forms the nonbelieving production model for the Book of Mormon.

11. Cement Buildings in the Land Northward

Here, Dr. Clark refers to the presence of cement buildings mentioned once in Helaman and states that the notion of cement buildings was "considered ridiculous" in 1830. Actually, cement plaster had been discovered in the aforementioned North American mounds and thus forms a part of the most pertinent background for the production model of a non-historical Book of Mormon. The Spalding manuscript (which I again present only as an example of what was present in Joseph Smith's cultural world, not as a literary source for the Book of Mormon) also refers to the working of stone to build walls and other stone implements.

The description in Helaman 3 is the only place where cement is mentioned in the Book of Mormon, and the specific content of the reference is highly problematic. First, it states that the use of cement to build houses came about because of the lack of timber in the land, suggesting it was a novelty. However, in Mesoamerica, the use of cement was relatively common before the time of Helaman 3. Second, Teotihuacan did suffer from deforestation, but the deforestation occurred as a result of the use of cement, which requires the burning of timber. To attribute the rise of cement buildings to a lack of timber reverses the order of causation and makes little sense in itself.