#tomtenney

Photo

Amazing public installation by @pwbuehler “Wall of Lies” at 12 Grattan Street. Color-coded text mural of lies by Trump. . . Interview visit with @chuckschumer on @radiofreebk !! . . 50' by 10' mural with more than 20,000 of Trump's lies. . . “I fact checked every one. Actually the Washington Post did.” - Phillip Buehler . . 12 Grattan St. (next to Pine Box Rock Shop) @pwbuehler collaborated with @tomtenney Tom Tenney, and Radio Free Brooklyn @radiofreebk will be doing a live broadcast where the public is invited to read on-air some of Trump’s crazier lies. . . #politicalart publicart #bushwick #installation #politicsinart #politicalartinstallation #walloflies #brooklynart #trumplies #chuckschumer #colorcoded https://www.instagram.com/p/CF7vexcFMOF/?igshid=1wp22n2i171he

#politicalart#bushwick#installation#politicsinart#politicalartinstallation#walloflies#brooklynart#trumplies#chuckschumer#colorcoded

0 notes

Link

After the start of the three-part miniseries about human nature in the last episode, this time we return to the topic with a more intense topic: personality! More specifically, this instalment is dedicated to the question of how stable our personalities really are. You can find new episodes on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, TuneIn, YouTube, or SoundCloud. Below, you’ll find the transcript of this episode with some references / further reading hyperlinks. The music for this episode comes from FreeSound, specifically these pieces:

https://freesound.org/people/Erokia/sounds/477924/

https://freesound.org/people/ajubamusic/sounds/320805/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/149300/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/154907/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/222741/

https://freesound.org/people/bigmanjoe/sounds/365958/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/200431/

https://freesound.org/people/tyops/sounds/443086/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/149300/

https://freesound.org/people/sofialomba/sounds/467936/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/180249/

https://freesound.org/people/fmceretta/sounds/426709/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/475959/

https://freesound.org/people/waveplay_old/sounds/219288/

https://freesound.org/people/Connum/sounds/12691/

https://freesound.org/people/tomtenney/sounds/125225/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/466655/

—————————————————————————————————————

Transcript

The question of who we are is often synonymous with an inquiry into our personality. But what exactly is personality? Personality is fundamentally individual, it’s supposed to characterize you as a character, as someone who has character. It should be like a fingerprint, unique to yourself as a person, but also something you share, to some degree, with others, a commonality which can lead to like or dislike. And even more importantly, it determines the course of your life and therefore can be used to predict your life, or at least the average life, to a certain extent. Decades of psychological research have identified five factors, five personality traits which seem to dwarf all others in importance. They loom so large that they’re referred to as the ‘Big Five’. Each of them represents a spectrum with opposing traits at its respective ends. This is the bedrock, the underpinning, the essence of personality. Which is why we will launch a frontal attack against the Big Five. Because if they topple, if they so much as flinch, personality as a concept in its current form comes crashing down with it. Let’s see if they do.

Introduction

You’re listening to Counterintuitive, the podcast about things which are not what they seem to be, and my name is Daniel Bojar. This episode is part of a three-part series about human nature. Last time we wrestled with preferences and their influence on our decisions. This time we’ll go after more challenging prey, what many would consider the core of our very being, our personalities. We’ll have a critical look if they truly are as clear-cut as intuition and a substantial body of research would have us believe. And then, next time, we will have our finale, in which we use everything from the first two episodes to address a puzzling conundrum affecting every single one of us that you are, most likely, not even aware of. Yet. But first things first. Off we go into the maze of personality.

Main

“Consistency is the last refuge of the unimaginative.” – Oscar Wilde in The Relation of Dress to Art

Back to the Big Five. Openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Or, in short as an acronym, OCEAN. There is probably no area in psychology which attracts so much attention and research as the Big Five. And perhaps rightly so, as these personality variables have been successfully used to predict your performance in school and life, your happiness (individually and in relationships), and so, so much more. They indeed seem like a firm foundation to build a field on top of.

Here’s a question though: if an acquaintance of yours regularly but unpredictably changed their height, on a range from the smallest person you know to the largest person you know, would you buy them clothes fitting their average height? Put another way, maybe revealing my game here, would the average height be indicative, be relevant to describe the stature of your acquaintance? And if not, then what would be indicative as a description? Keep this conundrum in mind for a while.

In one of my favorite research articles in the last couple of months, William Fleeson, psychology professor at Wake Forest University, analyzed a unique aspect of the Big Five, an aspect which at first sight let’s us question the solidity of our bedrock in personality research. I say ‘in the last couple of months’ because I recently stumbled upon this article. But it was originally published in 2001, nearly 20 years ago by now. I cannot stress enough how crucial this piece of information is. If you forget most of the content of this episode, this is one of the bits you should remember. A paper comes out nearly two decades ago, calls into question a cherished, intuitive concept by new data or new methods, and then is promptly discarded or ignored by most of the scientific community and the public. It��s a pattern you see again and again, if you just look. I could make at least a whole episode just about these kinds of scenarios. But I digress. What we’re interested in right now is of course the content of Fleeson’s article.

For this, you first have to understand how personality traits are typically assessed in scientific studies. Either participants venture to the laboratory to fill out some questionnaires or researchers, in a way, come to the participants, in the form of phone surveys or questionnaires filled out online. There are of course variations on this theme but that’s still the standard, orthodox way of data collection, today and certainly in 2001. Why is this important information? Let me recap some elements of the last episode for you. Last time, preferences were the main topic of interest. Specifically, the lack of stability in our preferences, which seemed to be swayed by irrelevant details in our environment. Specifically, by the context of a situation. Assessing the preference of a person in a laboratory or in their home during another activity will most likely leave you with two quite different answers. Even if you take multiple measurements, if they’re all done in the same context, the laboratory, the context will reliably exercise its power over the participants and make their preferences seemingly stable. Because the context is stable, the assessed preference is assumed to be stable. So, where do we collect most of the personality trait data? Ohh…

So Fleeson comes along in 2001 and has a different type of data in his pocket. For two to three weeks, his study participants had to use a handheld computer every three hours to record their feelings and actions. Then, on the last day of the study, the same participants also completed a standard questionnaire-type Big Five assessment for comparison. Of course today all of this is not such an unusual study setup but keep in mind this is twenty years ago. So his study participants go about their normal lives, with activities, stress, joy, and drama, and enter their data. Fleeson goes about analyzing this data – and finds something spectacular.

Did you let your subconsciousness work on our problem with your height-changing acquaintance? Is their average height or the spread between minimum and maximum height the relevant characteristic? What if it’s both? The statement that you need both kinds of information tells you that both aspects are informative in their own way. So the average height of your acquaintance would not tell you all too much about the range of heights they reach on any given day, and vice versa. Because if you could completely infer one quantity from the other, you wouldn’t need both for description.

By now you may have already guessed what Fleeson found in his data. Psychologists speak of within-person variability when they want to stress that the same person varies in some respect across time or situations, in contrast to between-person variability which tabulates variance between different people. When Fleeson analyzed the within-person variability with regard to behavior indicating Big Five states, he found this: within-person variability was high. Incredibly high. So high, in fact, that, and I quote, “the typical individual regularly and routinely manifested nearly all levels of all traits in his or her everyday behavior.” End of quote.

This is disturbing news. Especially if you connect it with another finding, that two behaviors of the same person are hardly related at all, with a correlation of around 0.3; that’s awful. So the conclusion of this seems to be that your behavior in one situation is more or less unrelated to your behavior in other situations. Given that behavior is strictly linked to personality, this erratic relation between behaviors at different occasions of course cast doubts on the immutability of the underlying personality. If you’re still on the fence, here’s the biggest result from Fleeson’s analysis: for all Big Five traits, within-person variability was equal to or higher than between-person variability. Just think about that for a second. Two random people from the street differ less in their personality on average than the same person in different environments! This is insane. Who you are depends on where you are.

We’re left with a paradox now. The extreme variability of personality traits in the same individual demonstrates that the mean value of a trait doesn’t properly reflect the individual behaviors of a person. But still, working with these mean values has resulted in a panoply of successful studies in which all kinds of things were correctly predicted. So obviously there is information present in the mean values, but why and how?

Combine that with another compounding factor, results from the Scottish Mental Study which followed participants for 63 years for six personality characteristics. Results suggested quite low stability of these personality aspects over time, robbing personality at least partially from its aura of temporal stability. A meta-analysis of hundreds of studies investigating the change of personality over time confirmed this view of weakening the personality stability theory.

And it doesn’t end there. There is a fully different beast lurking in personality research which we won’t have time to properly treat here. It’s intuition. Just to give you an idea why this is an issue, let’s have a quick look at one aspect of personality: self-esteem. Your subjective sense of self-worth may not be a trait among the illustrious Big Five but it’s still an ample source for scientific studies. Thousands and thousands of scientific studies in fact. Studies which investigate the effects your level of self-esteem and the interactions of self-esteem with your environment have on all kinds of things. Because it’s intoxicatingly intuitive that it should make a difference how high you view your self-worth.

Luckily, researchers are fond of reviewing an existing body of research every couple of years or so. That’s why, for instance, there is a magnificent meta-review by Thomas Scheff and David Fearon which looked at the whole field of self-esteem research. Around 15 000 academic publications. Here’s the gist of it: the strongest effect any study found, the strongest, explained around two percent of the variance. Two percent. Predicting anything with that is utterly useless. And nearly all other “effects” were even well below two percent. Statistically significant they may have been, but these effects don’t affect anything. Here’s some choice bits from their text (and I quote): “…studies of the relationship between social class and self‐esteem have reported findings that are ‘competing, inconclusive, and inconsistent.’ ” and “…studies of the relationship between crime and self‐esteem are ‘rife with contradictory or weak findings.’ “. End of quote.

So, bottom line: self-esteem doesn’t seem to be reliably important for anything. That’s already bad, as we would have expected it to matter at least somewhat. But the worst thing is that, even after this withering critique of their field, self-esteem researchers merrily went along and continued to churn out thousands of more-of-the-same papers in the following years. If this sounds familiar to Fleeson’s article from earlier on, you’re on the right track. Of course people rarely radically restructure their professional lives after such a blow to their worldview. Instead, we rather have to wait for the next generation growing up with a new, hopefully better, worldview instilled during their education, as we touched upon in an earlier episode. But I still think something more insidious is going on here. The intuitive belief that attributes such as self-esteem have to matter, have to make a difference is just nigh-irresistible for most. Why else would there not even be a mention of this meta-review or other doubts cast on the concept and importance of self-esteem on its Wikipedia page, 15 years after this subject has been so thoroughly broached? Counterintuition is hard and uncomfortable, which is why it’s a constant process rather than a one-off thing.

There’s a silver lining in Fleeson’s uncovering the variability of our personalities though. Fleeson refers to the spread of personality traits around their mean values as distributions which indicate the frequency of any type of behavior over the whole spectrum. The shape of these distributions then can potentially give you finer insight into the behavioral tendencies of an individual than the mean value. And most excitingly, this shape is an individual characteristic, akin to a fingerprint. You could identify people from the shape of their personality trait distributions. And it all boils down to your reactivity to context.

Let’s say you’re with a group of friends. No matter how extraverted you typically are, on average your extraversion increases with the time of the day (more extraverted in the evening than in the morning) and with the size of your group of friends (more extraverted in a larger group). But by how much your extraversion increases is specific to you as a person. Individuals can be more or less reactive to situational cues and their reactivity also depends on the respective trait. So a person may be more reactive in, say, their extraversion, than in their openness to experience.

With this, we again reach our central question: do we have stable personalities? And, again, the answer is: Yes and no. The mean values of Big Five traits are certainly predictive and valuable for research. Their purpose is to provide a long-term description of behavioral tendencies. If you’re high on extraversion in your Big Five assessment, you’re slightly more likely to react extraverted in any given situation. And this counts in the long run, at least to the extent it allows us to make predictions. But in the short-term these mean values are not optimal, though also not useless, to predict your behavior in any specific situation or for a period of time.

The extreme context-dependence of your personality makes the trait distribution a better description of your personality in everyday life. And it also, again, leads us to the conclusion that, in the specific interactions with others and your environment, personality is a process rather than a stable trait. Only in the long-term, between-people comparison is the concept of stable personality traits useful. To paraphrase William Fleeson again, this time from a later paper, the trait concept is useful for explaining behavioral trends while the process concept is useful for explaining actual behavior in the moment. And indeed, efforts have been started to build a social context-based personality model in addition to the trait-based model.

The problem is not that personality and your resulting behavior is fluctuating wildly and randomly over time. The problem rather is that these things are systematically influenced by your surroundings. So a friend who only meets you in large groups for late-night outings might perceive you as being far more extraverted than another friend who predominantly meets you alone for brunch. And both can be true simultaneously, because you really and authentically can be two different people in two different contexts. Because there is no single value that would describe how you react in every circumstance.

So the concept of personality, which is at least a merger of trait and process, has to change. Because imagine if you have another friend who knows you in different contexts and perceives your level of extraversion across these contexts as inconsistent. We often condemn inconsistency as hypocrisy or being inauthentic. But inconsistency is the norm, in so far as a plethora of different contexts in your life is typical. We should use the whole distribution, with mean value and everything else, to describe personality, not just one single number per trait. Because then, and only then, can we return to the concept of a stable personality, in which the whole distribution in its shape and position is stable. But in our current framework, personality is decidedly not stable, it’s fluid, erratic, idiosyncratic. At least to the outside. But if you look closer, you notice a pattern. An ocean consists of innumerable water molecules, each of them moving randomly and erratic. But if you zoom out and take in the whole concept, you notice patterns. Rippling waves, gliding across the waterscape not randomly but organized and in response to their environment.

P.S.: I mentioned the potential danger of labeling someone as inauthentic because of the inconsistency in their personality. But I neglected to address how the person him- or herself thinks of their behavior and personality. In a study, researchers investigated this connection between behaviors and authenticity. You would expect that behavior closest to their actual trait levels would elicit the highest levels of authenticity, of being your true self. But of course that’s not what happened. Rather, regardless of their actual traits, everyone was feeling more authentic when they were being extraverted, agreeable, conscientious, emotionally stable, and intelligent. This is madness. An introvert felt more authentic when acting more extravert, not when acting more introvert. Makes you wonder about the ideal personality we set as a society and its effects on the aspirations and feelings of authenticity of everyone not adhering to these ideal standards. Oh by the way, do you want to venture a guess who one of the two authors of this article was? Together with Joshua Wilt, it was, of course, William Fleeson. Who else.

Outro

That’s it for this episode of Counterintuitive! Don’t forget to check in next time when we wrap up this three-part miniseries. As always, you can find references and further reading for this episode in the show notes. If you like what you hear, please share it with your friends and subscribe on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcast from. It’s really appreciated. Every second Thursday a new episode will be uploaded. My name is Daniel Bojar and you’ve listened to Counterintuitive, the critical thinking podcast about things which are not what they seem to be. You can follow me on Twitter at @daniel_bojar or on my website dbojar.com, where you will find articles about other counterintuitive phenomena or concepts. Until next time!

via Science Blogs

0 notes

Photo

Spider-Woman . 1st - 4th slide is from the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe v3 11 (1991) by Keith Pollard 5th slide is by the Hildebrandt brothers (1994) 7th slide is from Force Works 3 (1994) by Tom Tenney and Rey Garcia. 8th slide is from Avengers West Coast v2 70 (1991) by Steve Butler and Danny Bulanadi. . #marvel #spiderwoman #avengers #90s #westcoastavengers #stevenbutler #keithpollard #josefrubinstein #dannybulanadi #tomtenney #reygarcia #daveross #usagent #scatter https://www.instagram.com/p/CVenbrQNCAl/?utm_medium=tumblr

#marvel#spiderwoman#avengers#90s#westcoastavengers#stevenbutler#keithpollard#josefrubinstein#dannybulanadi#tomtenney#reygarcia#daveross#usagent#scatter

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Force Works 5 (1994) . Written by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning Penciled by Paul Ryan Inked by Rey Garcia Cover by Tom Tenney and Rey Garcia . Force Works teamed up with Black Brigade to fight Ember... . #forceworks #marvel #superhero #ironman #scarletwitch #century #danabnett #andylanning #90s #comics #avengers #paulryan #tomtenney #reygarcia #ember #blackbrigade #usagent #spiderwoman https://www.instagram.com/p/CTKq9dMMArf/?utm_medium=tumblr

#forceworks#marvel#superhero#ironman#scarletwitch#century#danabnett#andylanning#90s#comics#avengers#paulryan#tomtenney#reygarcia#ember#blackbrigade#usagent#spiderwoman

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Force Works 4 (1994) . Written by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning Penciled by Tom Tenney Inked by Rey Garcia . Force Works investigated a possible mission in the wartorn country called Slorenia... . #forceworks #superhero #marvel #90s #tomtenney #reygarcia #ironman #avengers #scarletwitch #century #blackbrigade #slorenia #usagent #spiderwoman (på/i Europe) https://www.instagram.com/p/CSKCLPUsfJR/?utm_medium=tumblr

#forceworks#superhero#marvel#90s#tomtenney#reygarcia#ironman#avengers#scarletwitch#century#blackbrigade#slorenia#usagent#spiderwoman

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Iron Man 298 (1993) Written by Len Kaminski Penciled by Tom Morgan and Tom Tenney Inked by Avon and Don Cameron Iron Man fought the Earthmover, only to be faced with a newly awakened Ultimo... . #marvel #ironman #comics #lenkaminski #90s #avengers #earthmover #ultimo #tommorgan #tomtenney #avon #doncameron #losangeles https://www.instagram.com/p/CC7jbWchZgO/?igshid=11cs6y4oud4p2

#marvel#ironman#comics#lenkaminski#90s#avengers#earthmover#ultimo#tommorgan#tomtenney#avon#doncameron#losangeles

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Clea by Keith Pollard (1992) 1st - 4th slide is from The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe v3 18. 5th - 10th slide is from Women of Marvel. . Clea Strange . #marvel #clea #drstrange #defenders #magic #keithpollard #90s #princess #dormammu #darkdimension #wife #paulsmith #tomtenney #donperlin #tomsutton #richcase #kylehotz #marshallrogers https://www.instagram.com/p/CEQUrD8hJB4/?igshid=1lmdx22co4ljr

#marvel#clea#drstrange#defenders#magic#keithpollard#90s#princess#dormammu#darkdimension#wife#paulsmith#tomtenney#donperlin#tomsutton#richcase#kylehotz#marshallrogers

1 note

·

View note

Photo

U S Agent . 1st - 4th slide is from the Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe v3 29 (1993) by Keith Pollard and Josef Rubinstein. 5th slide is by the Hildebrandt brothers (1994) 6th slide is by Tom Tenney and Rey Garcia (1994) . #usagent #captainamerica #marvel #superhero #avengers #90s #keithpollard #josefrubinstein #reygarcia #superpatriot #tomtenney https://www.instagram.com/marvelman901/p/CZAiweZMSK6/?utm_medium=tumblr

#usagent#captainamerica#marvel#superhero#avengers#90s#keithpollard#josefrubinstein#reygarcia#superpatriot#tomtenney

1 note

·

View note

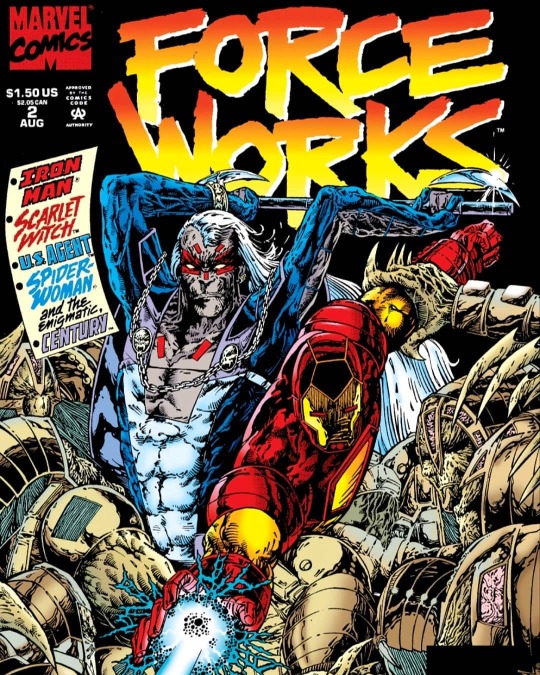

Photo

Force Works 2 (1994) . Written by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning Penciled by Tom Tenney Inked by Rey Garcia . Iron Man got help from Century to find and rescue his missing teammates... . #forceworks #avengers #ironman #marvel #superhero #century #alien #scatter #usagent #scarletwitch #90s #danabnett #tomtenney #reygarcia #andylanning #spiderwoman https://www.instagram.com/p/CP6XxOYBJsV/?utm_medium=tumblr

#forceworks#avengers#ironman#marvel#superhero#century#alien#scatter#usagent#scarletwitch#90s#danabnett#tomtenney#reygarcia#andylanning#spiderwoman

0 notes

Link

The fourth episode of my podcast, Counterintuitive, is online! Join me for a journeys into stories which are not what they seem to be. Episodes examine unusual concepts from a broad spectrum that will surprise you and then make you think. Because there’s always a layer beneath. You can find new episodes on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, TuneIn, YouTube, or SoundCloud. Below, you’ll find the transcript of this episode with some references / further reading hyperlinks. The music for this episode comes from FreeSound, specifically these pieces:

https://freesound.org/people/Dexnay/sounds/82310/

https://freesound.org/people/kangaroovindaloo/sounds/138288/

https://freesound.org/people/Setuniman/sounds/154907/

https://freesound.org/people/reecord2/sounds/85040/

https://freesound.org/people/bigmanjoe/sounds/365958/

https://freesound.org/people/fmceretta/sounds/426709/

https://freesound.org/people/tyops/sounds/443086/

https://freesound.org/people/tomtenney/sounds/125225/

https://freesound.org/people/LukeIRL/sounds/176020/

https://freesound.org/people/sofialomba/sounds/467936/

https://freesound.org/people/PSOVOD/sounds/416057/

—————————————————————————————————————

Transcript

In late 2016, seven penguins vanished from the zoo in Calgary, Canada. Well, not literally vanished. Their bodies were found after all. To the last of them, the seven penguins drowned. Imagine, penguins drowning. In water. In the summer of 2017, a pair of mountain goats got stuck on Brean Down cliff in Somerset, England. So badly, in fact, that they were trapped there for months. Some people were worried about the goats as the days passed by and they grew ever thinner. A few animal lovers even tried to climb up and carve a path to freedom for the stuck goats. Yet an unperturbed spokesperson of the National Trust remarked ‘It is common for goats to get onto ledges and rock faces and, while it can look as though the goat is stuck, they do tend to get themselves down when they are ready.’ Mere hours after this statement – imagine the sad irony – one of the goats jumped from the ledge, fell down, and died.

Introduction

My name is Daniel Bojar and this is Counterintuitive, the podcast about things which are not what they seem to be. This time we will zoom into a conviction, a bias, an intuition we all carry with us. It’s the naturalist bias or appeal to nature fallacy, glorifying all things natural and condemning everything artificial. I mean, just consider the emotions evoked by the words ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ and you already see the problem we have at our hands. Because natural isn’t perfect and artificial isn’t bad by default. But, first things first. We’ll get to artificial in a future episode, so let’s focus on natural here. Since the naturalist bias is strongly anchored in most people, we have to exercise caution not to provoke backlash. So we’ll start slow, remote, perhaps insignificant. We’ll start with a humble beetle.

Main

We’re in Western Australia. It’s dry, it’s hot, and seemingly devoid of life. Well, not quite. In front of us flies a beetle, a large specimen of the species Julodimorpha bakewelli, also known as the giant jewel beetle. Not so humble after all. But giant indeed, as these insects can reach lengths of up to four centimeters of bright red or brown color. Like so many species, the survival of the giant jewel beetle is endangered because of our actions. But there’s a twist. We don’t hunt these insects, we don’t exactly destroy their environment, heck, in this case not even climate change can be really blamed for the slow demise of the giant jewel beetle. If you want to be mean, you could put part of the blame on the giant jewel beetle itself. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

Our story will soon lead us to Harvard University, North America, and eventually the whole world. Yet for now, we’re still in Western Australia. Just a few meters from where we started, our giant jewel beetle has found what it was looking for. Or, rather, what he was looking for. Because, you see, it’s August and that means it’s mating season for the giant jewel beetle. And mating season means finding the best possible mate, to ensure maximal genetic fitness for the offspring of our beetle. That’s why he endured the blazing Australian sun and now his insectile eyes are locked on his precious prize.

Finding a good mate is crucial for individuals of any species. Operating through natural selection of the fittest offspring, evolution usually occurs in species which reproduce sexually. Thereby, they accrue mutations which can improve or deteriorate the fitness of offspring, with fitness implying the number of their offspring. So, you would think that mate selection with its direct link to procreation is one of the processes where evolutionary investments would have the greatest payoff and which are therefore optimal to the highest degree possible. Having established this mechanism as a particularly well adapted process in the evolution of species, I will now spend a good part of the rest of this episode to dismantle this notion. Because if I can convince you that the intricately evolved mate selection system isn’t always working, maybe I can convey my broader argument, that natural isn’t necessarily good. Ready?

Let’s not quite yet return to our giant jewel beetle. After all, they had millions of year of evolution to adapt to their environment, so they should be fine for a minute or two without us. Instead, let’s go to Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts. It’s September 29th, 2011. Darryl Gwynne and David Rentz have come here for an award ceremony. Specifically, their award ceremony. Several Nobel Laureates are present as well, together with other distinguished scientists, and of course the media. This prize captures quite some international attention. The scientific work Gwynne and Rentz will be awarded for was published nearly 30 years earlier, in 1983. At the time, they were stationed at the Department of Zoology in the University of Western Australia. See the connection? Their paper, of course, focused on Julodimorpha bakewelli, the giant jewel beetle, and its mating process. The prize which Gwynne and Rentz receive in 2011 is typically described as awarding ‘research that makes people laugh and then think.’ It’s the Ig® Nobel Prize, an award which honored research about kickstarting barbecues with rocket fuel, alarm clocks fleeing from you to aid waking up, or the science of sword swallowing.

Back in Western Australia, our beetle has proceeded in his mating mission and, while we were gone, reached his mating partner. He extends his aedeagus, the protrusion to release his sperm, and tries to insert it. I should have warned you that this will get steamy. After mating, the female giant jewel beetle will lay the fertilized eggs at the roots of Eucalyptus trees, where new beetles will hatch and joyfully populate Western Australia. But wait. Something’s odd. The mating partner our beetle has selected seems large. Too large. You could even call it gigantic. Instead of a length of four centimeters, typical for a giant jewel beetle, the mating partner beneath our beetle is 23 centimeters long. Granted, it’s brown, but if you look closely you’ll see that it’s not a female giant jewel beetle. It’s a beer bottle.

In their paper, which was honored with the Ig® Nobel Prize, Gwynne and Rentz found that properties of beer bottles – brown color, reflectiveness, and stubs or undulations on the bottle – are sensory stimuli which are extremely salient for male giant jewel beetles. These are features which those beetles typically look for in female beetles, yet they prefer Australian beer bottles in trials. The increased activation, or even overactivation, by these features, in this case by special types of bottles, is an example of what researchers refer to as ‘superstimuli,’ which are often artificial. To demonstrate that this really represents a genuine effect, Gwynne and Rentz presented their beetles with wine bottles, which didn’t impress the mate-seeking beetles much. Apparently, they’re discerning drinkers.

It may seem funny to picture giant beetles humping glass bottles in the desert, but researchers are actually worried this behavior might endanger the survival of the whole species. Next to the foregone mating opportunity, by choosing a beer bottle, giant jewel beetles engaged with their glassy partners have been observed to fall easy prey to ants which calmly start to dismember the occupied beetle. The beetle-bottle romance really seems to be an intense thing.

Now, is this an episode about the giant jewel beetle and its challenges in life? Yes and no. The preference of our beetle for beer bottles over female beetles represents an evolutionary maladaptation. Basically, this means that the salience of features overly present on beer bottles is a bad choice, in evolutionary fitness terms, in a world littered with beer bottles. Provocatively, it’s stupid of the beetle to like beer bottles better than real mates, there is no payoff to this in any way. The first objections to this will be that it’s our fault that beer bottles lie around and, also, it’s just been a few decades and evolution has basically no chance to catch up with changes that quick.

And I think we now have finally arrived at the core of this whole issue.

Of course it’s true that it’s our fault that the environment is littered with beer bottles and, for many reasons, we should try to remedy this unfortunate circumstance. But, abstractly, every animal changes its environment by its actions, humans included. The notion of a keystone species, beloved by conservationists and environmentalists alike, is exactly that it has a disproportionate effect on its environment compared to what would be expected based on its population. So animals hailed as the most important in an ecosystem change it the most. Naturally, we as humans do that on a gargantuan scale and destroy a lot in the process, but in principle change is nothing foreign to nature. That’s what evolution is for after all.

Imagine if we stick to our despicable habit of littering in the countryside. Male giant jewel beetles with an affinity for beer bottles will be removed by natural selection over the long-term and the evolutionary process goes on. Yet it’s not a given that the species as a whole will adapt. It may survive or it may go extinct if it can’t change fast enough. This depends on a lot of factors, pure chance in terms of mutating the right genes at the right time being one of the biggest. And if the species does change, the mate selection will be quite different than before and may even be worse than before. Because by accruing evolutionary changes to avoid beer bottles, you may need to sacrifice valuable salient attributes typically used in mate selection. You just can’t optimize everything at the same time. In the end, the product, if viable, will not be better but different. Evolution is goalless, so the assumption that evolved creatures accrue advantages in a continuous fashion over time is faulty.

The other major issue is speed. Environments change, and species will change accordingly, or die out. But importantly, this doesn’t happen at the same time. First environments change, and then species adapt, by selecting the few random individuals which by chance exhibited mutations that are now beneficial. Because pre-adaptation of a whole species to potential changes in the future would be too wasteful to sustain. This means that there is a time in between, in which environments already underwent significant change but the species in its entirety didn’t fully adapt to these changes yet. You can see this with our beetles. Their environment changed, but they haven’t yet changed accordingly. Since evolutionary processes typically take months, years, decades, or even longer, all dependent on the generation time of the animal, all we get is a snapshot of the whole process. As a consequence, the species and animals we currently observe are not necessarily well adapted to their current circumstances. We have no way of intuitively telling if what we see in any given species is a snapshot or a stable state. Our main fallacy is to view evolution as a result or a thing that happened in the past and now just fine-tunes species a bit further. Evolution, however, is a process, and frequently a messy process at that.

So to recap: in a fast-changing environment, natural oftentimes is decidedly suboptimal. And with climate change and the drastic influence we humans as a globe-spanning species have on the environment, changes occur with a mind-boggling velocity and with far-reaching consequences. Which means we really have to update our conception of optimized ecosystems and the species therein. Drowning penguins and plunging mountain goats may be a rare sight but they are currently entirely absent from our imagination and intuition. As we idealize and even idolize animal ability, conceptions of failure in their environment don’t even begin to enter our intuition.

If you’re still not convinced, take the island of Surtsey in the Atlantic Ocean, close to Iceland. Before 1963, no land existed at the coordinates which now harbor Surtsey. Yet by now, Surtsey boasts fauna as well as flora. A timespan of around fifty years may be sufficient to populate a virgin island, a process extremely fascinating for scientists to observe, but it’s certainly not enough to achieve evolutionary mastery over these fresh surroundings. Animals inhabiting Surtsey will have come from somewhere else and, on an evolutionary level, are still adapted to their previous environment and will continue on this route for a very long time. Therefore, current species present on Surtsey certainly can’t be seen as the embodiments of perfect adaptation to their surroundings. In fact, some of them may not even be categorized as ‘good’ in terms of their adaptation to the environs of Surtsey. But as long as no better adapted species comes along, desiring the same evolutionary niche for itself, the original maladapted species might be able to eke out a living thanks to a lack of competition, even though its adaptation to its environment is far from ‘good.’ In new environments, natural absolutely doesn’t go hand in hand with exhibiting good adaptation, as many species will die out because of a clear lack of adaptation.

Even in largely non-changing environments evolved doesn’t mean optimal, just good enough to avoid extinction. Consider the humble ant. You could easily see it as the embodiment of industriousness, on par with bees perhaps, constantly used in metaphors implicitly glorifying the natural world. It epitomizes the attitude of a selfless worker chugging along to sustain and further the colony. At least that’s what intuition will tell you. In 2015, researchers around the entomologist Daniel Charbonneau at the University of Arizona conducted a simple experiment: paint differently colored dots on each ant and track them. What did they find? Around 40 percent of ants don’t do anything; nearly half of the entire working force! They just sit around and watch the others do all the work. They’re lazy. Normally you wouldn’t notice that as an observer because ants are scrambling about in a dizzying mess, making it hard to track individual ants and compare between them. Currently, it’s believed that these slackers are forming a kind of workers reservoir. Remove the productive ants and, eventually, the lazy ants will step up their game and make sure that the colony has enough food and other materials. On a grand scale, this might make sense in terms of robustness in the face of adversity, though it appears to come at great cost. And it’s decidedly not in line with our intuitive assessment of industriousness and optimality.

But let’s go back to changing environments, because as we’ve seen they’re the norm. When humans entered North America via the Beringia land bridge from Siberia a couple of ten thousand years ago, they dramatically changed the environmental framework resident animal species were operating in. Being expert hunters, early humans relentlessly culled unprepared animals, which before this had no reason whatsoever to prepare themselves for this onslaught. Most affected by this were species constituting the megafauna, animals weighing more than 40 kg. And by ‘most affected,’ I of course mean that they went extinct. A lot of them. Species dying out in North America shortly after the arrival of humans include the Western camel, the mammoth, all forms of wild horses, all variants of North American tapirs, and the American lion. That’s just a tiny fraction of the species our ancestors hunted to extinction. You add naturally evolved humans to naturally evolved animals and what do you get? Certainly not perfection.

But wait for it, the most insightful piece of information is still coming. Obviously, not all animal species in North America went extinct in prehistoric times. Survivors included the grizzly bear, bison, bighorn sheep, and grey wolves. What did all of these animals have in common? Their ancestors coevolved with humans in Asia. By slow natural selection of fit animals via an increasingly skilled population of human hunters, for these species the descent of humans into North America didn’t represent a radically new environment. They were prepared.

There are hardly any species which you could point to that survived the megafauna extinction and whose ancestors did not coevolve with humans. One of these remarkable exceptions is the pronghorn, colloquially known as the American antelope, even though it technically isn’t even an antelope and is more closely related to giraffes. The pronghorn and its ancestors didn’t spend any time in human-populated areas and still survived the incoming human hunters. This is remarkable. And it only could do that with an extraordinary ability it possesses. Because the pronghorn is the second-fastest mammal on our planet, inferior only to the lightning-fast cheetah. Even then, three of the four pronghorn genera in existence succumbed to the evolutionary pressures of hordes of human hunters. So in effect, to even have a chance at survival as a species, you either need to be already familiar with your surroundings or you need to be world-class in something which incidentally is beneficial to your survival once change is underway.

This unlikely constellation of factors doesn’t bode well for the infallible quality we often bestow upon nature and all things natural. Especially if you consider that this sequence of events is not limited to North America. Here’s an incomplete list of habitats in which the arrival of enterprising humans in prehistoric times led to mass extinction events in the megafauna shortly thereafter: Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, Cyprus, Japan, Madagascar, and South America. As Carl Sagan already noted, ‘Extinction is the rule. Survival is the exception.’ Most species fail, precisely because they were not good, in terms of their environment. Evolution makes species only as efficient as they have to be for their current environment, not as much as they could be in theory. Adapted instead of optimal. Being complex creatures with multiple needs, animals aren’t perfect and sometimes, if change occurred relatively recently, they’re not even good. And for better or worse, change is underway, with increasing temperatures, ocean acidification, deforestation, extreme weather events, and much more, so even if we can slow it down we better get used to some of the natural losing its splendor. As for the giant jewel beetle, its current adaptation to its new environment certainly can’t be described as good and won’t be for a long time if beer bottles remain in the plains of Western Australia. If it survives this struggle, the giant jewel beetle won’t be the same as before. But, and this is crucial, it won’t be better, just different.

Outro

I hope you’ve enjoyed this instalment of Counterintuitive! If you did, join me next time where we’ll talk about the fascinating multitudes of our personalities. You can find references and further reading for this episode in the show notes. If you like Counterintuitive, please recommend it to your friends and give it a 5-star rating on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcast from. It really helps. A new episode will be uploaded every two weeks. My name is Daniel Bojar and you’ve listened to Counterintuitive, the critical thinking podcast about things which are not what they seem to be. You can follow me on Twitter at @daniel_bojar or on my website dbojar.com, where you will find articles about more counterintuitive phenomena. Until next time!

via Science Blogs

0 notes