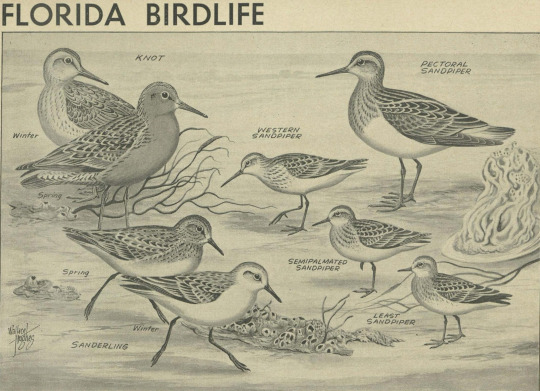

#western sandpiper

Text

Florida Wildlife; vol. 12, no. 2. July, 1958. Illustration by Wallace Hughes.

Internet Archive

#birds#waders#sandpipers#western sandpiper#pectoral sandpiper#semipalmated sandpiper#least sandpiper#sanderling#red knot#Wallace Hughes

122 notes

·

View notes

Text

A flock of western sandpipers (Calidris mauri) landing in Morro Bay, California

by marlin harms

#western sandpiper#sandpipers#seabirds#birds#calidris mauri#calidris#Scolopacidae#charadriiformes#aves#chordata#wildlife: california#wildlife: usa#wildlife: north america

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calidris mauri [ヒメハマシギ,Western Sandpiper]

Calidris alpina [ハマシギ,Dunlin]

久々に海へ。

ヒメハマシギ、小さくてかわいかったです。初��初撮。

鳥まで距離がありましたが何とか証拠写真。

後ろはハマシギです。

#Calidris mauri#ヒメハマシギ#Western Sandpiper#Calidris alpina#ハマシギ#Dunlin#Bird#野鳥#photographers on tumblr

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember to read about the contestants before voting!

Western Sandpiper

These beach combing fellows wander up and down the beach, in huge flocks, looking for biofilm. For a long time, scientists thought Western Sandpipers ate only invertebrates from the sands, but actually they’re on the hunt for a delicious, slimy set of microorganisms! Learn More!

Steller's Sea Eagle

The Steller’s Sea Eagle is one of the heaviest birds in the world. They eat mainly fish, although their second favorite food is seagulls and other, smaller birds. They breed up in Russia, and then winter south, in Japan and other parts of Asia. Their current population is estimated at 5,000 individuals and decreasing, and are considered vulnerable. Learn More!

(Western Sandpiper photo by Derek Lecy)

(Steller's Sea Eagle photo by Ian Davies)

280 notes

·

View notes

Text

95 notes

·

View notes

Text

Western Sandpiper - Pilrito-miúdo (Calidris mauri): adult

Oeiras/Portugal (22/09/2023)

[Nikon D500; AF-S Nikkor 500mm F5,6E PF ED VR]

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

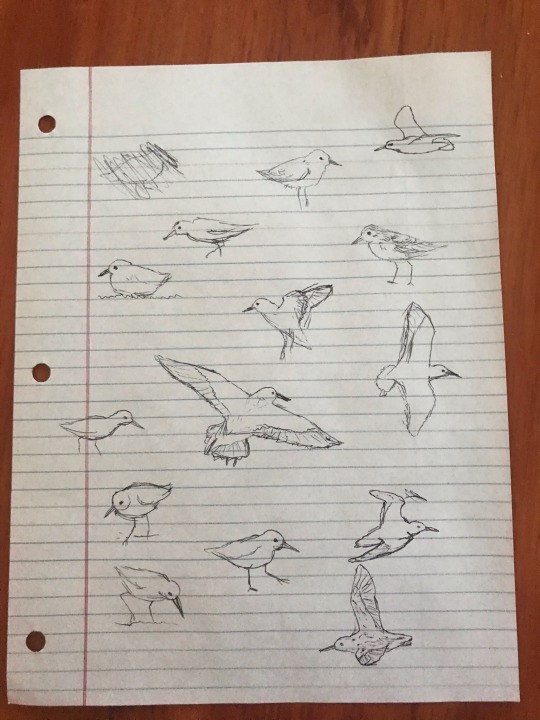

Sandpiper sketches!

#birds#sandpipers#sandpiper#western sandpiper#bird#nature#art#wren arts#idk if I have a tag for that yet#the witcher fandom urge to just start sketching sandpipers at any given moment#the only reason they aren’t all wearing bard hats is that I wanted to practice the birds#netflix played right into my hands with that nickname

36 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri)

© Bill Holland

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shorebirds! I believe this is a western sandpiper and a lesser yellowlegs

#birds#original photography#original photography on tumblr#nature#vancouver island#nature photography#pnw#birding#bird photography#birdwatching#shorebirds#western sandpiper#sandpiper#lesser yellowlegs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

some soup for the traveler on the edge of town

#week 2! during week 3 but ignore that#week 3 will probably be more low effort but whatever#im testing new harpy designs#we got my boy oliver (western sandpiper) and his friend james (monk vulture)#still placeholder names cuz idk what the naming conventions of this universe are yet 😭 we're getting there#oliver had to bring him soup in a crockpot cuz his family doesn't own vulture-sized bowls#i love vulture wings they dont fold very neatly down onto the bird's back because of how huge they are so most vultures look like a mess#all my rat#original character#oliver has some yet-unnamed genetic defect that makes his feathers curly#because i was absolutely determined to keep his original hairstyle#kinda makes him look like a sheep imo

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Save Barr Lake Series.

Barr Lake State Park is located in Brighton, CO. It is a crucial resting ground for hundreds of thousands of migrating birds, as well as numerous year round residents.

In September of 2023, the company FRICO, who owns the water rights to the reservoir, began removing cottonwood trees and destroying the marshes that so many birds rely on during their migrations. This was in an effort to expand the reservoir for increased strain by fracking, oil, and gas companies in the area.

Despite the Bird Conservancy of the Rockies having an important bird banding research station near the destruction, they were not consulted about the environmental impacts until after public outcry. The ongoing construction may impact the Eagles returning this January to begin building their nests for the spring breeding season - the effects are yet to be seen.

#art#painting#artwork#artist#birds#birds of prey#owl#sandpiper#great horned owl#wilsons warbler#bird art#western grebe#illustration#traditional art#tombow markers

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

western sandpipers :)

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juho Salo

The ruff (Calidris pugnax) is a medium-sized wading bird that breeds in marshes and wet meadows across northern Eurasia. This highly gregarious sandpiper is migratory and sometimes forms huge flocks in its winter grounds, which include southern and western Europe, Africa, southern Asia and Australia.

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

I Love Dick And Balls

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle,[2] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[3] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[4]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the U.S.[5]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the U.S. and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[6]

Description

The American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[7] Females are considerably larger than males.[8] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[4] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[9]

Illustration of American woodcock head and wing feathers

Woodcock, with attenuate primaries, natural size, 1891

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[8] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[4] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[8] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[10]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[4]

Taxonomy

The genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[11] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[12] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[13]

Distribution and habitat

Woodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcock have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[8]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[8]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[8] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[3] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[8]Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime. Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings. Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.). Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[8]

Migration

Woodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[14] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[8] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[15] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[8]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[16]

Behavior and ecology

Food and feeding

American woodcock catching a worm in a New York City park

Woodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[8] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

In spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[8] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[17]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[8]

Woodcock chick in nest

Downy young are already well-camouflaged.

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[4] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[3] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[8] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[18] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[3]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[19]

Rocking behavior

American woodcocks sometimes rock back and forth as they walk, perhaps to aid their search for worms.

American woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[20] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[21]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[22] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[23]

Population status

How many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[4]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[8] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[6]

Conservation

The American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][24] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[17]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[6]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[25]

Leslie Glasgow,[26] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[27]

References

BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

"American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. Smithsonian Institution. 142 (1): 61–78.

"American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7.

Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 0878939660.

Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

[1]Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further readingChoiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5. Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External linksAmerican woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter American Woodcock Bird Sound Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock American Woodcock videos[permanent dead link] on the Internet Bird Collection Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253. vte

Sandpipers (family: Scolopacidae)

Taxon identifiers Wikidata: Q694319 Wikispecies: Scolopax minor ABA: amewoo ADW: Scolopax_minor ARKive: scolopax-minor Avibase: F4829920F1710E56 BirdLife: 22693072 BOLD: 10164 CoL: 6XXHP BOW: amewoo eBird: amewoo EoL: 45509171 Euring: 5310 FEIS: scmi Fossilworks: 129789 GBIF: 2481695 GNAB: american-woodcock iNaturalist: 3936 IRMNG: 10836458 ITIS: 176580 IUCN: 22693072 NatureServe: 2.105226 NCBI: 56299 ODNR: american-woodcock WoRMS: 159027 Xeno-canto: Scolopax-minor

Categories:IUCN Red List least concern speciesScolopaxNative birds of the Eastern United StatesNative birds of Eastern CanadaBirds of MexicoBirds described in 1789Taxa named by Johann Friedrich Gmelin

#pro rq 🌈🍓#radqueer#rq#rq community#rq please interact#rq safe#rq 🌈🍓#rqc🌈🍓#transid#pro radqueer#radqueers please interact#radqueer safe

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remember to read about the contestants before voting!

Andean Cock of the Rock

Known for their mohawk head of hair and funny name, the Andean Cock of the Rock is the national bird of Peru. The males will join up in large groups, called "leks", performing for females who watch the hunk buffet. They mainly eat fruits and insects, however they will also feast on small lizards and amphibians. Learn More!

Western Sandpiper

These beach combing fellows wander up and down the beach, in huge flocks, looking for biofilm. For a long time, scientists thought Western Sandpipers ate only invertebrates from the sands, but actually they’re on the hunt for a delicious, slimy set of microorganisms! Learn More!

(Andean Cock of the Rock photo by Ben Lucking)

(Western Sandpiper photo by Dorian Anderson)

#bird battle#round two#polls#birds#andean cock of the rock#cock of the rock#western sandpiper#sandpiper

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

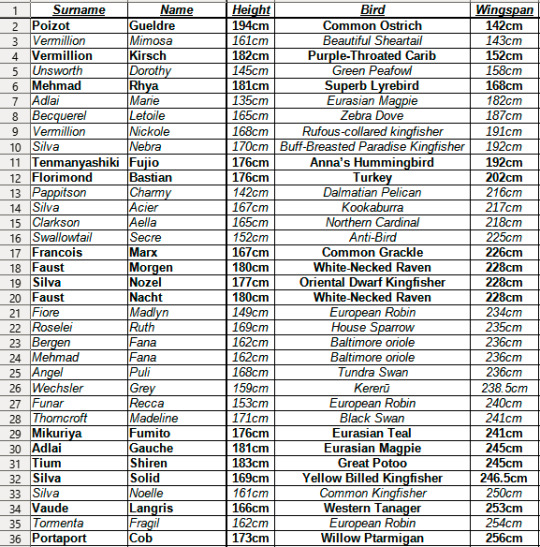

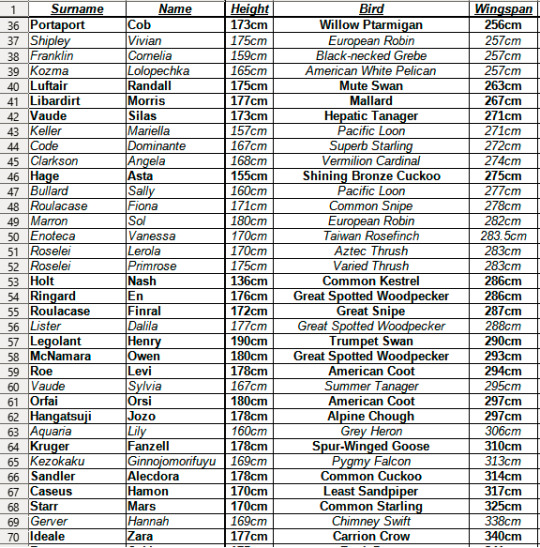

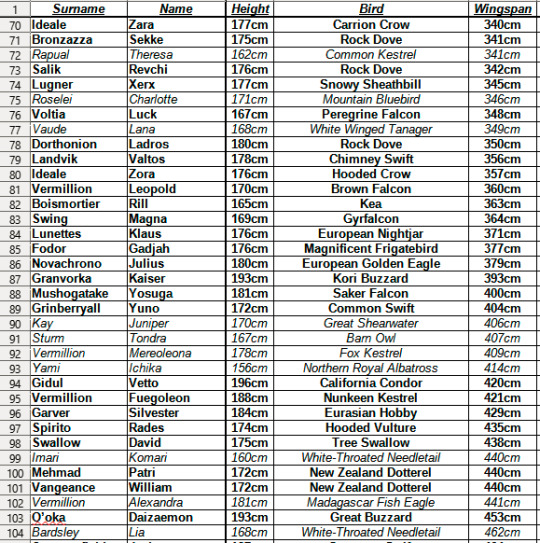

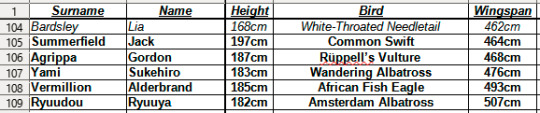

I don't really talk about my aus on here, but I'm pretty proud of the work I've put into this one so I thought I'd share

Nobody ask how long this took.

As per usual, several of the ocs on this list (Nickole, Bastian, Aella, Madlyn, Ruth, Madeline, Vivian, Cornelia, Silas, Angela, Primrose, Lerola, Dalila, Levi, Sylvia, Hannah, Juniper, Silvester, Alexandra and Alderbrand) belong to the lovely @crazedstoryteller, the rest of the ocs (Fiona, Lana, Tondra and Lia) are mine, and obviously canon chracters are canon

(alternate version of the table under the cut)

Surname Name Height Bird Wingspan

Poizot Gueldre 194cm Common Ostrich 142cm

Vermillion Mimosa 161cm Beautiful Sheartail 143cm

Vermillion Kirsch 182cm Purple-Throated Carib 152cm

Unsworth Dorothy 145cm Green Peafowl 158cm

Mehmad Rhya 181cm Superb Lyrebird 168cm

Adlai Marie 135cm Eurasian Magpie 182cm

Becquerel Letoile 165cm Zebra Dove 187cm

Vermillion Nickole 168cm Rufous-collared kingfisher 191cm

Silva Nebra 170cm Buff-Breasted Paradise Kingfisher 192cm

Tenmanyashiki Fujio 176cm Anna’s Hummingbird 192cm

Florimond Bastian 176cm Turkey 202cm

Pappitson Charmy 142cm Dalmatian Pelican 216cm

Silva Acier 167cm Kookaburra 217cm

Clarkson Aella 165cm Northern Cardinal 218cm

Swallowtail Secre 152cm Anti-Bird 225cm

Francois Marx 167cm Common Grackle 226cm

Faust Morgen 180cm White-Necked Raven 228cm

Silva Nozel 177cm Oriental Dwarf Kingfisher 228cm

Faust Nacht 180cm White-Necked Raven 228cm

Fiore Madlyn 149cm European Robin 234cm

Roselei Ruth 169cm House Sparrow 235cm

Bergen Fana 162cm Baltimore oriole 236cm

Mehmad Fana 162cm Baltimore oriole 236cm

Angel Puli 168cm Tundra Swan 236cm

Wechsler Grey 159cm Kererū 238.5cm

Funar Recca 153cm European Robin 240cm

Thorncroft Madeline 171cm Black Swan 241cm

Mikuriya Fumito 176cm Eurasian Teal 241cm

Adlai Gauche 181cm Eurasian Magpie 245cm

Tium Shiren 183cm Great Potoo 245cm

Silva Solid 169cm Yellow Billed Kingfisher 246.5cm

Silva Noelle 161cm Common Kingfisher 250cm

Vaude Langris 166cm Western Tanager 253cm

Tormenta Fragil 162cm European Robin 254cm

Portaport Cob 173cm Willow Ptarmigan 256cm

Shipley Vivian 175cm European Robin 257cm

Franklin Cornelia 159cm Black-necked Grebe 257cm

Kozma Lolopechka 165cm American White Pelican 257cm

Luftair Randall 175cm Mute Swan 263cm

Libardirt Morris 177cm Mallard 267cm

Vaude Silas 173cm Hepatic Tanager 271cm

Keller Mariella 157cm Pacific Loon 271cm

Code Dominante 167cm Superb Starling 272cm

Clarkson Angela 168cm Vermilion Cardinal 274cm

Hage Asta 155cm Shining Bronze Cuckoo 275cm

Bullard Sally 160cm Pacific Loon 277cm

Roulacase Fiona 171cm Common Snipe 278cm

Marron Sol 180cm European Robin 282cm

Enoteca Vanessa 170cm Taiwan Rosefinch 283.5cm

Roselei Lerola 170cm Aztec Thrush 283cm

Roselei Primrose 175cm Varied Thrush 283cm

Holt Nash 136cm Common Kestrel 286cm

Ringard En 176cm Great Spotted Woodpecker 286cm

Roulacase Finral 172cm Great Snipe 287cm

Lister Dalila 177cm Great Spotted Woodpecker 288cm

Legolant Henry 190cm Trumpet Swan 290cm

McNamara Owen 180cm Great Spotted Woodpecker 293cm

Roe Levi 178cm American Coot 294cm

Vaude Sylvia 167cm Summer Tanager 295cm

Orfai Orsi 180cm American Coot 297cm

Hangatsuji Jozo 178cm Alpine Chough 297cm

Aquaria Lily 160cm Grey Heron 306cm

Kruger Fanzell 178cm Spur-Winged Goose 310cm

Kezokaku Ginnojomorifuyu 169cm Pygmy Falcon 313cm

Sandler Alecdora 178cm Common Cuckoo 314cm

Caseus Hamon 170cm Least Sandpiper 317cm

Starr Mars 170cm Common Starling 325cm

Gerver Hannah 169cm Chimney Swift 338cm

Ideale Zara 177cm Carrion Crow 340cm

Bronzazza Sekke 175cm Rock Dove 341cm

Rapual Theresa 162cm Common Kestrel 341cm

Salik Revchi 176cm Rock Dove 342cm

Lugner Xerx 177cm Snowy Sheathbill 345cm

Roselei Charlotte 171cm Mountain Bluebird 346cm

Voltia Luck 167cm Peregrine Falcon 348cm

Vaude Lana 168cm White Winged Tanager 349cm

Dorthonion Ladros 180cm Rock Dove 350cm

Landvik Valtos 178cm Chimney Swift 356cm

Ideale Zora 176cm Hooded Crow 357cm

Vermillion Leopold 170cm Brown Falcon 360cm

Boismortier Rill 165cm Kea 363cm

Swing Magna 169cm Gyrfalcon 364cm

Lunettes Klaus 176cm European Nightjar 371cm

Fodor Gadjah 176cm Magnificent Frigatebird 377cm

Novachrono Julius 180cm European Golden Eagle 379cm

Granvorka Kaiser 193cm Kori Buzzard 393cm

Mushogatake Yosuga 181cm Saker Falcon 400cm

Grinberryall Yuno 172cm Common Swift 404cm

Kay Juniper 170cm Great Shearwater 406cm

Sturm Tondra 167cm Barn Owl 407cm

Vermillion Mereoleona 178cm Fox Kestrel 409cm

Yami Ichika 156cm Northern Royal Albatross 414cm

Gidul Vetto 196cm California Condor 420cm

Vermillion Fuegoleon 188cm Nunkeen Kestrel 421cm

Garver Silvester 184cm Eurasian Hobby 429cm

Spirito Rades 174cm Hooded Vulture 435cm

Swallow David 175cm Tree Swallow 438cm

Imari Komari 160cm White-Throated Needletail 440cm

Mehmad Patri 172cm New Zealand Dotterel 440cm

Vangeance William 172cm New Zealand Dotterel 440cm

Vermillion Alexandra 181cm Madagascar Fish Eagle 441cm

O’oka Daizaemon 193cm Great Buzzard 453cm

Bardsley Lia 168cm White-Throated Needletail 462cm

Summerfield Jack 197cm Common Swift 464cm

Agrippa Gordon 187cm Rüppell’s Vulture 468cm

Yami Sukehiro 183cm Wandering Albatross 476cm

Vermillion Alderbrand 185cm African Fish Eagle 493cm

Ryuudou Ryuuya 182cm Amsterdam Albatross 507cm

10 notes

·

View notes