#historical writing

Text

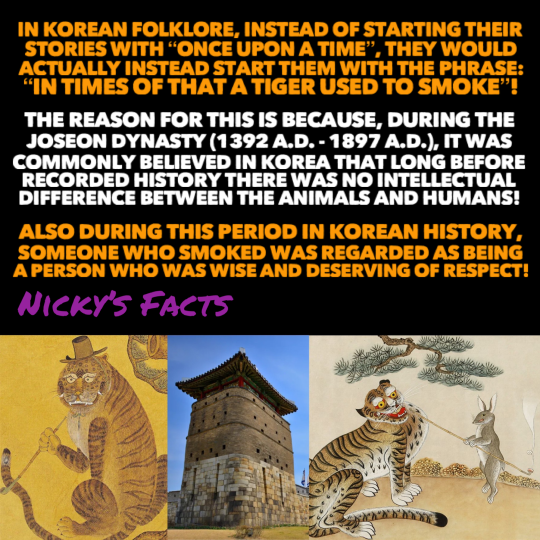

History memes #36

#funny humor#funny memes#history memes#funny#history#humor#meme humor#historical writing#historian#historian jokes#historian memes#sillyposting#silly

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Korean legends come from a time before a intervention was held for the tigers involving their smoking addiction!😂

🚬🐅

#history#korea#in times of that a tiger used to smoke#folklore#tiger#once upon a time#korean history#joseon dynasty#fairy girl#fairycore#asia#animal history#smoking#korean culture#folktales#legend#historical writing#fairy tales#animals#phrase#korean folklore#nickys facts

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

I. Sürgünlik

Aim to make us feeble, if our name is scorned, if our fame is shamed, What defines us as people? - Rıza Fazıl

I wince when people speak about their fathers; not out of hatred, but rather an unknowing sense of envy—his adolescence was far from the all-American tri-varsity lifestyle many experienced. When asked about him, I often find myself diluting his character into a falsehood that can be easily understood; in other words, I lie. I lie the same way he lies about his name when ordering takeout, to spare employees from the burden of mispronunciation. I lie about his background because his ambiguity requires a history lesson I simply do not care to restate. I have heard the question “What is your dad again?” on countless occasions, and although I understand what the question entails, I mask my annoyance with oblivion to avoid repeating myself—in truth, my father’s complexity stems from before he was even born.

The bane of his existence is hereditary; his frustration is an heirloom granted to him by his blood. In the mid-1940s, my Grandfather fell victim to the Crimean Tatar Genocide. He was ten years old when the first mass deportation of his entire ethnic group occurred. Over the course of his childhood, all aspects of his being had been stripped from him by Soviet occupation—my Grandfather, who previously lost his own father to the ongoing war, had to witness his two younger brothers starve to death on frigid trains with no destination. The bloodshed of the Crimean people was considered to be a cleansing; from the start, my Grandfather has been in a position of inferiority no matter the location of his refuge. His history was one which I never fully understood in my early childhood, yet one my dad taught me nonetheless. Perhaps he was using his father's traumas to justify his personality while I was still too young to understand. All I knew was that my Deda’s deportation was the cause of my Dad’s eternal sense of displacement. My Father holds his breath when he speaks of the genocide. My Grandfather is pained at the memory of his childhood, but recognizes the importance of his history regardless; the value of education surrounding his people surpasses the pain of explanation. I was passed down both the knowledge of my bloodline and the feeling of alienation that runs through it.

It was nearly Summertime when Soviet policemen invaded my Grandfather’s village. His first direct encounter was with two armed men at his door, demanding the presence of his family. They forcibly took them from their home, with the rest of the Crimean population following shortly after. Within the span of 3 days, the NKVD (Interior Ministry of the Soviet Union) deported Crimean Tatars of all ages through cattle trains; however, the deportation mostly impacted women, children, and the elderly, because men of age had previously been sent into battle. Their destination? Over 3,000 kilometers away in Uzbekistan, another region that had fallen under Russian Occupation. As each day passed aboard bolted-up cargo, he fell into an unfathomable state of malnourishment and dehydration. His two younger brothers, one of which was a newborn, were both physically incapable of withstanding such conditions for weeks at a time. From the beginning, they had no chance of survival. My grandfather’s entire life trajectory had been altered the moment those two men appeared affront his home; his childhood in Crimea came to a hasty conclusion as his adulthood began in Tashkent at the age of 10. I often find that he precariously lives out their childhood and his own through his mannerisms. He sings and claps when he sees my dog, calls me his baby despite my 16 years of age, and makes sure I always leave his home with a full stomach; because under his wrinkled skin and calloused fingers stands a confused child who does not yet understand the consequence of existing as the other.

#writing#crimean tatars#crimea#essay#personal essay#creative writing#personal writing#history#world history#war#historical writing

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

HAD AN IDEA!!!

so I'm writing a thing rn (book? novel? story?? what do you even call it lmao) and i've been trying to do more art related to it, but i've been failing miserably

SO

i've decided that i'm going to challenge myself by drawing something for each song on the playlist!!! (not in order lol)

here is said playlist:

here's a bonus sketch of palemon <33

#i won't be doing two “je vivroie liements” unless i get creative because theyre just.... the same#but i think this will be a good method of conceptualizing everything anyway#yes it says “girl idk what this is” in latin because I DONT FUCKING HAVE A TITLE YETTT 😭 😭 😭#writing#original writing#original story#oc#ocs#oc art#art challenge#spotify#EL art stuff#Spotify#medieval#historical fiction#historical writing

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is nothing more satisfying then when you're writing a backstory for a fictional historical character and you do research on what was happening during the time and country and EVERYTHING FITS. LIKE, YOU CAN FIT THEM INTO THINGS AND IT'S ACCURATE TO THW CHARACTERS AND THE HISTORICAL EVENTS

For example: I'm writing a backstory for Tintin, but he's Belgian and (in this) is growing up in ww2 and I can't ignore the war because Beligum literally gets invaded (it always does poor thing.) What would Tintin do in a war? Join the resistance, ditch the Hitler Youth programs to play with Snowy, write anti-German and Belgian humor in underground newspapers and Le Faux Soir and do risky jobs in the Resistance helping Jews escape because it's the right thing to do and Tintin does the right thing.

...

THERE WERE UNDERGROUND BELGIAN NEWSPAPERS, STUDENTS AND YOUNGER KIDS IN THE BELGIAN RESISTANCE AND STUDENTS WHO HELPED WITH THE RISKY PASSIVE REVOLT THAT WAS LE FAUX SOIR IT'S LITERALLY P E R F E C T

Now I need to do a bit more research and stop procrastonating and get writing

#historical writing#historical fiction#tintin#les adventures de tintin#the advetures of tintin#hergé#writing#books#tintin headcanons#UGH IT FITS SO WELLLL#went down a wormhole on Wikipedia doing research for this#im so excited for this

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

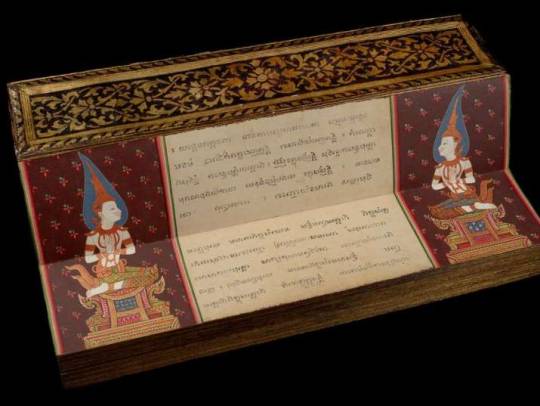

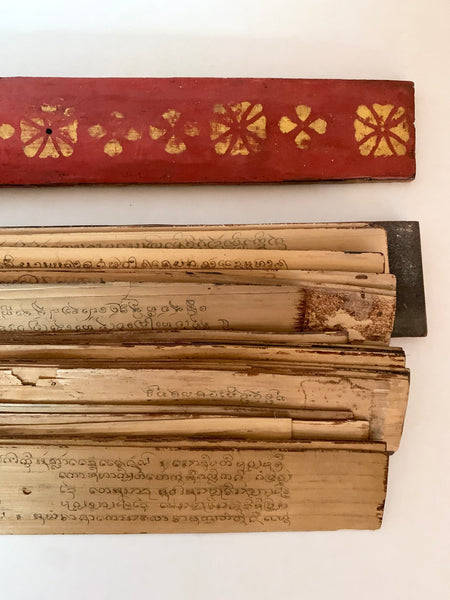

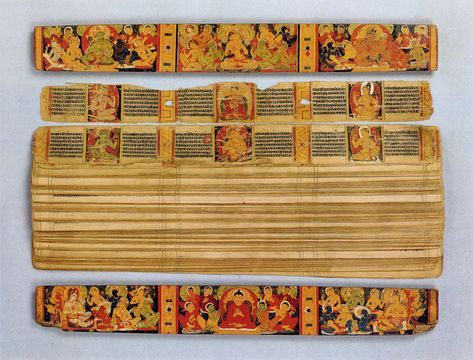

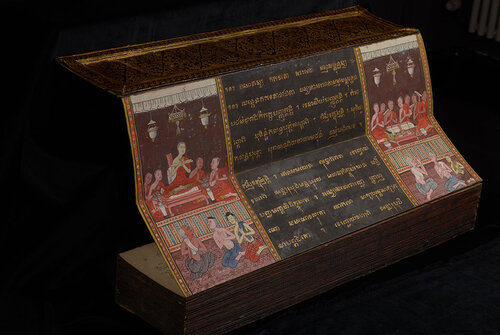

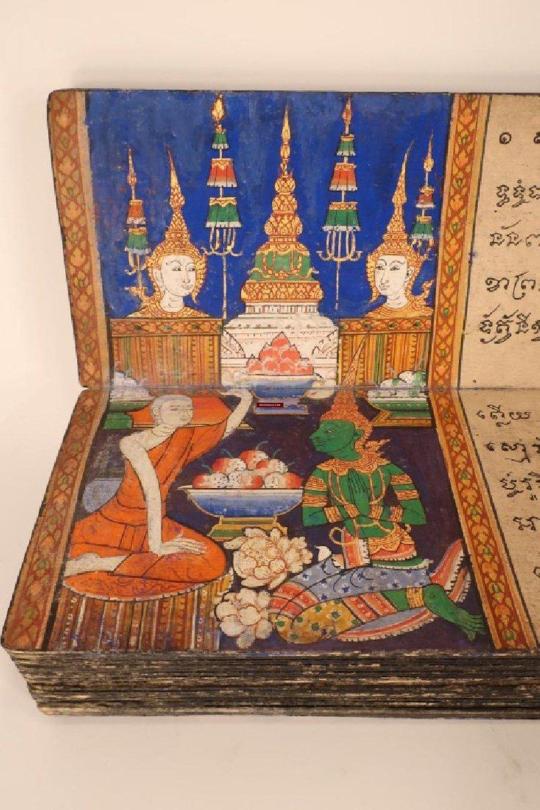

Historical writing practices in Thailand

Thailand, along with other areas of Southeast Asia and India, traditionally used palm leaf manuscripts.

The individual palm leaves were first dried and a type of stylus / knife pen was used to inscribe the text. Natural colourings are then added to sit in the groves of the text and a clean cloth is then used to wipe off the extra colour.

In Thailand there were two ways the palm leaves were used.

The first involved individual thin strips of leaves which were punctured with holes and then threaded together with string.

The second employed a style known as folding book manuscripts where a thick piece of paper, often made from the Siamese rough bush tree, was glued together in a long sheet.

This was then folded in concertina fashion with the front and back lacquered to protect the inside.

These unbound books can be found with white and black pages. Soot being used to darken the latter.

This technique was called samut khoi in Thailand and dates back to the Ayutthaya period (14th-18th centuries.)

Illustrated folding books were very popular in Buddhist monasteries and among royals and nobles.

#thai culture#historical writing#historical books#history#literature#beautiful books#man suang fic inspiration

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

uh small writing practice I did today!

Untitled so far, it’s a historical romance set in pre colonized Tenochtitlán, the city in Mexico in the Mexica, or Aztec Empire. Yeah :)

The sharpened arrow to the throat. The dull blades to the gut.

The two young adults stared at each other in disbelief. At the glimmering gold on his fingers, to the cream colored cloth on her body. The only thing that had lit up the entire night, was the moon shining above them. It shone softly, yet enough for Xipilli to see the strange girl. For Meztli to see the strange boy.

The strange girl’s hair was cut short, in almost a boyish way. His nose was crooked, broken possibly. What was she even doing here? How did she sneak into the palace gardens? She was breathing oddly- unevenly. Was this her first time thieving? Xipilli tried to search her eyes. Yeah, it had to be. Her eyes glimmered shakily, the color of white moon. She was about to stab him in the stomach. Yet she looked…beautiful.

Who was this strange boy? Meztli had certainly never seen this certain nobility in the parties down town. She heard rumors of the Emperor’s and the Priestess’ bearing children but nothing of this pathetic, shriveled boy. His features were sharp, cute pointed nose, chin, rounded sharped ears- he looked almost like a skeleton. His face was scarred- probably from warrior training, yet his hold on his bow was hesitant. He had to be a runt of the Emperor’s children; Did he seriously not know how to hold a bow?

Meztli’s muscle was tense, it ached heavily, tight on the turquoise handle of the blade. No, she cannot even think about this boy’s life, no matter how pitiful it may be. She did not know him. She might never truly know him.

They continued to hold their position for a minute. Xipilli was underneath her yet held his bow and obsidian tipped arrow in an advantageous position. Meztli was on top, holding two blades right over his stomach. Their inhales were deep and sharp. One thing they both noted however, were their eyes. Each were huge, like prey.

“Eztli.” Meztli spat, rather quietly.

“Hm?” Xipilli blinked, drawing his arrow back first. He had been staring at the moon reflecting in her eyes too long to realize she had spoke.

His mind first went to the fact we let his guard down, but she flipped her daggers, and placed them behind her back. “Stupid,” She muttered, adjusting her clothes and hiding her mud stained skin. “Call me Eztli.”

“Oh.” Xipilli thought his answer for a moment, momentarily forgetting his own name. “Xipil- that is my name.” He bowed a little, before he took his obsidian arrow and placed it on the ground. Was he not being robbed? Killed? Kidnapped? He looked at the ground; perhaps he was being pitied.

The girl nodded, scratching her hair. “It is good to meet you, Xipil.” He had smelled sweet, sweet like the laelias that grew south of the great city. She cleared her throat and crossed her arms. “I believe this is good bye, Xipil. I must leave.”

But Xipilli didn’t notice her words- no he was also thinking. She smelled of a certain cactus juice, dull/ but like dried mud, the ones tracing her skin seemed to be a part of her. It was beautiful- She was, looking like tapestry…art itself. From her poised stance, from her interested look in the high moon: a Goddess.

What would Mother ever think of him for that.

Meztli took her stance to the edge of the building. “Let’s agree on something, Xipil.”

“Huh?” His eyes widened, and he registered the scene, “Wait, don’t—!”

Meztli sighed, looking at him. “Listen boy- I must go. However if you tell the authorities about me I will not hesitate to find you and slice your throat. Let’s call this even: You don’t kill me. I don’t kill you. Deal?”

Xipilli slowly let her words sink in. He tried to speak, his mind racing. Meztli sighed again before he nodded. “I-I mean- uh- okay. I will not tell them.” Xipilli looked up within the second, with a large, sly grin. “But if I see you again, may we talk? Perhaps over a drink?”

Meztli stopped looking at the edge of the building, calculating her jump down and looked at the young boy, annoyed. “This is goodbye. I will not see you again.”

Xipilli went to her, closely. “But I do not want it to be.”

“It must be.” Meztli insisted.

“But,” Xipilli said, a plead in this voice. “I will see you again, right?”

Meztli put her mask on again, the face of Mictecacihuatl, the Queen of the Underworld, and stared back him. “Perhaps in another life.” She jumped.

#creative writing#writblr#historical fantasy#historical romance#historical writing#tenochtitlan#mexico#frenchfriez_#writing#yippee writing!#yeah uh <3 enjoy#Spotify

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

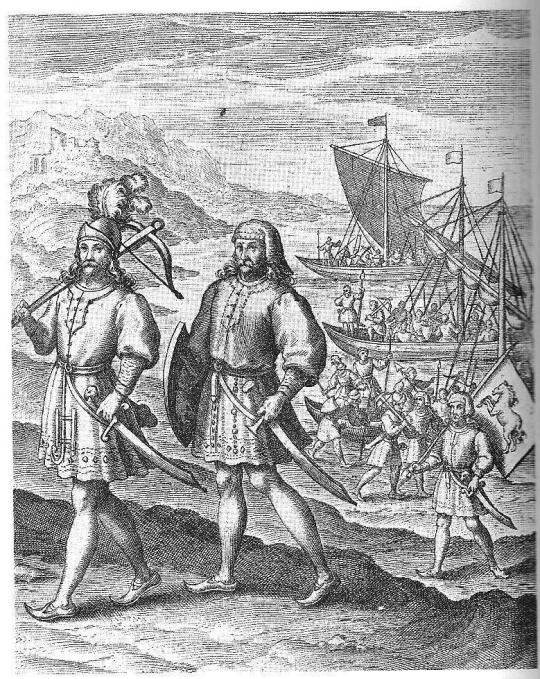

A New Theory on the Saxon Settlement of England

An original essay of Lucas Del Rio

Note: My previous recent essay had focused on the work of Geoffrey of Monmouth, and to some extent it was a more general historiography. Continuing with a historiographical theme, I had initially intended to follow it with an essay comparing primary accounts of conflict and warfare between Brythonic and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the early Middle Ages. During my research, I developed a personal theory that I propose below.

Little is known for sure of the years that immediately follow the withdrawal of the Roman army from Britain sometime around 410. The Latin works that were characteristic of the Roman era almost completely vanish except for a few texts penned by a handful of monks. Literature in Old English does not appear for centuries and is long limited to hymns and poetry, as is virtually everything written in Welsh. Histories written on Britain that discuss this era are mostly from much later in the Middle Ages. The first manuscript of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a historical text on England commissioned by King Alfred the Great, does not appear until 891. It is sometimes difficult for modern historians to determine when their medieval counterparts recorded the truth versus when they jotted down contemporary legends, especially when they were often writing centuries after the alleged events occurred. Meanwhile, conclusions from archaeological evidence are largely guesswork.

Several names have been coined for this era, including “Sub-Roman Britain,” “Dark Age Britain,” and “Britain in the Age of Arthur.” Developments that historians do know of are reflected in these terms. Roman Britannia now ceased to exist, and the provinces there which had for centuries been under the central control of Rome had fragmented. The Britons had regained their former autonomy, with the Romans that stayed behind now dwelling in the decaying remains of once prosperous towns. Petty tribal kingdoms reappeared and resumed their old quarrels with one another. Decentralization of national authority meant that there were numerous tiny armies led by local chiefs rather than a massive imperial force that could crush insurgencies. With no organized administration beyond competing warlords, society no longer functioned the way that it had before. Roads ceased to be maintained, aqueducts fell into disuse, bandits opportunistically plundered the countryside, Irish and Norse pirates raided the coasts for loot and slaves, and a barter economy took the place of the discontinued system of Roman coinage.

Not all historians agree that everything about Britain after the Romans left represented a “Dark Age,” however. French writer Jean Markale goes as far as to call the era a “Celtic renaissance.” It is true that the end of Roman administration allowed the Celtic Britons to govern themselves once again, and not always in small chiefdoms. The medieval Welsh clergyman Geoffrey of Monmouth writes of a new Brythonic dynasty emerging in the wake of Roman withdrawal. While Geoffrey of Monmouth is very frequently criticized by scholars, modern historians do recognize that Britain did indeed have some very powerful Celtic kings such as Urien ruling over vast realms like Rheged at the start of the Middle Ages. Some of the wars between these kingdoms were said by contemporary Britons such as the bard Taliesen to have seen massive battles, descriptions of which can still be found in Welsh poetry. Local economies, infrastructure, and security all collapsed, but Celtic culture clung on through these calamities. Christianity fused with traditional pagan elements to form the British Church, which held certain unique beliefs from Rome despite occasional accusations of heresy by popes. Through the efforts of members of this church, especially St. Patrick, the other Celtic nation of Ireland also saw most of her population converted to Christianity.

Sub-Roman Britain has thus sometimes been romanticized by the Celts of later eras, who do not hold the view that this was truly the Dark Ages. The most immortal hero of the Celtic Britons symbolizes this phenomenon to a greater extent than anyone or anything else that can be said about the period, hence why the term “Age of Arthur” has been used by some scholars and enthusiasts. On one hand, Arthur can be viewed as representing the glory of the Celtic Britons, although he can also be said to be a personification of their downfall as told by their descendants in Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany. By the late Middle Ages, there had been a number of popular “Arthurian romances,” and these novels tended to focus on classic tales such as the sword and the stone, the knights of the round table, and the quest for the holy grail. While some aspects of these stories had roots in Celtic lore, the King Arthur that authors were writing about in the 1400s was far removed from Celtic society. Descriptions of Camelot and his court were actually more representative of that time than the Brythonic era. To the old Britons, however, Arthur was a king intent on preserving the traditional Celtic ways. His earliest appearances in two early medieval chronicles, the 833 work The History of the Britons and the 1136 work The History of the Kings of Britain, portray him as a heroic leader who battled the invading Saxons.

More modern archaeological finds do not indicate there being a sole “King of the Britons,” as Arthur is often called, anytime after the Romans withdrew their armies. Perhaps the Celtic Britons had a system where a single figurehead took charge of the different regional kings during a time of crisis, just as Cassivelaunus had done centuries earlier when the Britons resisted Julius Caesar. Maybe the knights of the round table were an echo of elite Brythonic warriors in the battles that Arthur led. The historicity of Arthur is irrelevant, however. What is more important is that the greatest significance of the most iconic figure of British lore is his involvement in an epic struggle between two peoples laying claim to the land that would become England. Such a narrative dominates much of English historiography. Gildas, the Venerable Bede, Nennius, Geoffrey of Monmouth, Henry of Huntington, and many other early chroniclers highlighted a Saxon invasion that pitted them against the Britons in the southern half of the island. It created England, thus transforming the island of Britain forever. Since medieval times, historians have continued to tell this story.

Like all intellectual disciplines, of course, the study of history evolves. Recent evidence has caused some scholars to challenge the notion that there was a grand war between Britons and Germanic peoples such as the Saxons. They say that the old idea that the Britons were systematically killed off and England was conquered is not supported by the new science of genetics, as the English today still share similar genes with the inhabitants of the region millenia prior to the alleged invasion. The remains found in 1995 of a prehistoric individual in Cheddar Gorge, despite being nine thousand years old, were discovered to be quite genetically related to the locals. A much larger genetic study stretching from 1994 to 2015 concluded that as little as twenty percent of modern English DNA is Germanic. Both of these findings are examples of why these scholars say that the earlier inhabitants of England were never exterminated by the Saxon newcomers and that they merely blended with the indigenous population. D. F. Dale, in his book The History of the Scots, Picts, and Britons: A study of the origins of the Scots, Picts, Britons (and Anglo-Saxons) in Dark Age Britain based on their own legends, tales, and testimonials, even suggests that there may have been a Germanic population in some parts of England even prior to the Roman conquest. Nor can the Britons be considered a homogeneous people, they say, for the same study that was completed in 2015 found great genetic variation between the modern Welsh, Scottish, and Cornish populations.

All of this new evidence from a rapidly growing scientific field has prompted certain researchers to deny that there was a Saxon invasion at all. Instead, they say, there was a process of gradual settlement. Such a notion completely contradicts primary accounts, however. While medieval chroniclers can certainly be unreliable, they did genuinely understand aspects of their era that we undeniably cannot, and the fact that all of them agreed that there was a Saxon invasion makes it difficult to deny that it happened in some shape or form. Another finding from the aforementioned study could potentially show some degree of ethnic cleansing, for example. People living in Wales today show substantial genetic differences from all other regions of Britain, with the Welsh being more related than everybody else to the original British hunter-gatherers. Wales is a predominantly Celtic region and is notable for the fact that many of the locals still speak Welsh, a Celtic language, unlike Cornwall and Scotland where Cornish and Gaelic, respectively, are spoken only by a small minority of the populace. The Celts, then, can be shown genetically to be either the indigenous population of Britain or at least one who eventually mixed with an older group, and there was likely a great deal of violence in England to cause fewer of their descendants to live there than in Wales.

Considering, however, that all parts of Britain show far greater diversity than mere Germanic descent, it can be concluded that simply more Celtic Britons survived in Wales than in England. This does not mean that there was a genocide against the Britons per se, but rather that ethnic identity in early medieval Britain was closely linked to politics and war. Celts, Saxons, Scandinavians, and the Irish lived in every region, but certain areas were increasingly dominated by clusters of kings from one group or another. The Celts, once the unchallenged masters of the entire island, would go on to rule Wales and Cornwall. Meanwhile, England became the domain of the Saxons, and the Scottish emerged from earlier Celtic, Pictish, Irish, and Scandinavian inhabitants of the north of Britain. English, Welsh, and Scottish kings all had their own armies, of course, each composed primarily yet not not exclusively of their respective nationalities. These armies periodically clashed, and the fact that the kings and nobles belonged to certain ethnicities meant that civilians of other groups were more likely to be victims of violence during wars, even when a kingdom may have been very diverse. Within the various kingdoms in the different regions, one group may have had the privilege of controlling the nobility while another was forced to be under the yoke of serfdom. To put it simply, kings throughout the island had an array of subjects, although the hierarchy of society was still dependent on ethnicity, and the importance of this during wars led to regional stratification.

To support these arguments, consider the writings of medieval chroniclers. Their stories share both many similarities and differences. All seem to agree that the island had once been the exclusive domain of the Britons, with the Picts and Scots arriving sometime before or during the Roman era. According to the English monk the Venerable Bede, in his 731 work Ecclesiastical History of the English People, states “some Picts from Scythia put to sea in a few longships, and were driven by storms around the coasts of Britain.” Later, “the Picts crossed into Britain, and began to settle in the north of the island.” In describing the origins of the Scots, the Venerable Bede writes “they migrated from Ireland under their chieftain Reuda and by a combination of force and treaty, obtained from the Picts the settlements that they still hold.” He tells both of these stories prior to his description of the arrival of the Romans. Welsh clergyman Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his 1136 book The History of the Kings of Britain, differs in this respect, instead writing of the Picts and Scots appearing at the time of Roman imperial control. Geoffrey of Monmouth writes that “a certain King of the Picts called Sodric came from Scythia with a large fleet and landed in the northern part of Britain which is called Albany.” Next, “Marius thereupon collected his men together and marched to meet Sodric” and “once Sodric was killed and the people who had come with him were beaten, Marius gave them the part of Albany called Caithness to live in.” Regarding the Picts and the Scots, he says that the latter “trace their descent from them, and from the Irish, too.”

These events occurred before the dawn of the Middle Ages and the subsequent coming of the Saxons to Britain, but they demonstrate a similar historical trend of wars based on ethnic control yet not ethnic cleansing. It was a middleground of sorts between genocide and mere settlement because there was indeed violence, although it was to assert political control rather than carry out a campaign of complete extermination. King Sodric of the Picts had the ambition of violently wrestling from the Romans territory that they controlled in Britain, with the Romans then tolerating a local Pictish presence once this hostile foreign king was removed as a threat. Reuda of the Irish would conquer territory that had formerly belonged to the Picts. They must have subjugated the Picts rather than killing them off, however, for the two peoples later mixed to form the Scots. Geoffrey of Monmouth writes that the “five races of people” in Britain were “the Norman-French, the Britons, the Saxons, the Picts, and the Scots.” When he wrote his chronicle, the Normans had conquered England relatively recently, and this shows that they made know attempt to wipe out the Saxons despite stripping them of their power. In his book History of the English, the last edition of which was completed in 1154, Henry of Huntington asserts that the Picts “have entirely disappeared, and their language is extinct.” The Picts thus eventually did die out. Since they survived for as long as they did and the evidence for their decimation was the fact that their language was no longer spoken, it can be concluded that the Picts were gradually assimilated after a long period of Scottish domination.

The appearance of the Picts and Scots in Britain was long before that of the Saxons and the coming of the Normans long after. Medieval accounts show that the newly arrived Saxons were initially quite aggressive towards the local Brythonic inhabitants. At the time that the Saxons emerged on British soil, there were already ongoing political struggles between kings of different ethnic groups. In the most contemporary account, the 540 text On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain, the Romano-British monk Gildas describes how the Britons were to be ruined and conquered while “inviting in among them like wolves into the sheepfold, the fierce and impious Saxons, a race hateful both to God and men, to repel the invasions of the northern nations.” These “northern nations” were presumably the Picts, for the Venerable Bede writes that the Britons “for many years this region suffered attacks from to savage extraneous races, Irish from the northwest, and Picts from the north.” They were vulnerable to attack because the Romans “informed the Britons that they could no longer undertake such troublesome expeditions for their defense.” According to Geoffrey of Monmouth, “about this time there landed in certain parts of Kent three vessels of the type which we call longships” which were “full of armed warriors and there were two brothers named Hengist and Horsa in command of them.”

Apparently, according to The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles commissioned by King Alfred the Great of Wessex centuries later, the reason that the 443 plea for aid was refused was because the Romans were struggling to fight Attila and his horde. With the Britons desperate for any form of help, Hengist and Horsa are said to have earned their trust and then stabbed them in the back. Historians today have no direct evidence for the legitimate existence of Hengist and Horsa other than chronicles written long after the Saxons had established a foothold on the island, yet the story nonetheless reflects a genuine historical timeline. Gildas, for example, claims that the Saxons arrived with full permission from “that proud tyrant Vortigern, the British king.” In The History of the Britons, a work of disputed authorship which may have been penned by the monk Nennius, the Saxon brothers are said to have become friends of Vortigern after their exile from Germany. The Venerable Bede says the result was that the Saxons commanded by Hengist and Horsa fought the Picts on his behalf and “received from the Britons grants of land where they could settle among them on condition that they maintained the peace and security of the island against all enemies in return for regular pay.” These events are early evidence that Britain in this era may have been divided into kingdoms with rulers of particular ethnic groups, but their subjects were a different story. Vortigern was a Britons who presumably was in a power struggle with one or more Pictish kings, although he was willing to both incorporate Saxons into his army and grant them fiefs. Furthermore, his kingdom was structured in a way where society was built around its ethnic makeup. Saxon warriors employed by Vortigern sound as if they earned actual wages, an extremely rare practice in the Middle Ages and even more so in the earliest centuries of the medieval era.

Hengist and Horsa were two Saxons who had the ambitions of being kings of their own. The Venerable Bede writes that “a larger fleet quickly came over with a great body of warriors, which, when joined to the original forces, constituted an invincible army.” It was then that they chose to rise up against the Brythonic leadership, and the fighting did not strictly pit all groups against each other, for he also says “the Angles made an alliance with the Picts.” In these wars, it was the power of a king and not the power of the ethnicity he belonged to that mattered, and he would fight or partner with whoever he had to. Unfortunately for the Britons, they appeared to be cornered on all sides by the newer inhabitants of the island regardless of who fought alongside who at a given time. Gildas records the final and unsuccessful Romano-British plea for help from the imperial forces as including the haunting phrases “the barbarians drive us to the sea” and “thus two modes of death await us.” However, local leadership may still have been deliberately misrepresenting as genocidal persecution of what really just threats to their own power from Picts, Scots, and Saxons.

Chroniclers in the centuries that followed demonstrate in their writings that the local rulers went many years without letting battlefield setbacks break their resolve. While both Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth tell of Vortigern fleeing to a remote hideout and eventually being killed, several of the historians note the victories won by a Romano-British general, or perhaps even king, named Ambrosius Aurelianus or Aurelius Ambrosius. According to the Venerable Bede, he was the last remaining leader in Britain from the Roman era and in 493 led the Britons to win a battle against the Angles for the first time. In one battle that Ambrosius apparently led, Henry of Huntington says that Horsa finally met his death. Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that Ambrosius and his brother Uther Pendragon both were poisoned by Saxon assassins, but the latter was the father of Arthur. Nennius writes of Arthur being chosen by the different Brythonic kingdoms to lead their warriors in twelve victorious battles against the Saxons. He states, however, that this did not cause Saxon leaders in Germany to cease continuing to provide support to those fighting in Britain.

All of these details suggest divisions in Britain between native kings and the Saxons, but none of them demonstrate anything beyond that. Vortigern must have been a highly influential king over large parts of Britain, or else he would not have had the power to have incorporated enough Saxon vassals into his domain for them to gradually muster such enormous military strength. If Vortigern was a king who exercised significant hegemony, it was strategically important for ambitious Saxon war leaders to drive him out of power, but nothing suggests a full-scale deliberate attempt to exterminate the native Britons of his kingdom. The chroniclers all record widespread violence against civilians, but this would have been a tactic of forcing the majority of them into submission. Gildas writes that the Britons “constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves forever to their foes.” Class divisions based on ethnicity, often very severe, were emerging in the new kingdoms that were ethnically diverse despite the ethnic divisions in the area of kingship. Mutual oppression unquestionably would have created major animosity and was certainly used by war leaders, such as Ambrosius and Arthur on the side of the Britons, to rally support. Saxons undoubtedly did the same.

In the centuries that followed the arrival of the Saxons, their kings assumed control of more and more of the island. Kingdoms led by Britons persisted in the southwestern regions of Wales and Cornwall, while in the north the Scots settled down and absorbed the Picts. Just as the Britons had historically quarreled, so, too, did the Saxons, who began to be called the “Anglo-Saxons” as they mixed with the Angles. Some of their kings, including Edwin and Oswiu of Northumbria, started to become quite powerful. The Anglo-Saxons found a sense of national unity when they faced a foreign invader of their own, the Vikings, in the 800s, with strong leaders such as Alfred the Great taking charge. During the 900s, the Kingdom of Wessex established the Kingdom of England after uniting all of the Anglo-Saxons and securing a dominant position over Wales and Scotland. A Welsh poem from that century called “Armes Prydein” prophesied that the greatest of the Brythonic leaders from the 500s and 600s would be reincarnated and unite Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, Scotland, and Ireland against the English, yet this has long proven to be wishful thinking on the part of whichever wandering bard wrote its words. Many centuries later, however, the Anglo-Saxons have never fully replaced the indigenous Celts of Britain or her neighbors. Wales still has the Welsh, England still has the Cornish, France still has the Bretons, Scotland still has the Scots, and the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland still have the Irish, even though all but two of these six countries are now a part of the United Kingdom. Britain was diverse then and is diverse now despite the tensions still caused by differences in national identity.

#alfred the great#Arthurian legend#artwork#britain#British history#British Isles#england#essay#historians#historical debate#historical writing#historiography#history#king arthur#medieval#medieval literature#Middle Ages#theory#uk#writing

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

travllingbunny clearly meant the F&B text in the comments. That person is a Alys/Aemond shipper who believes the relationship in the book was consensual and a love story and thinks the part about him taking her as his "war prize" was unreliabe since the maesters weren't there to witness their relationship.

Huh. So I finally hear a reason other than "helps her down from Vhagar" and "the Strongs were abusive" for the thought that Alys and Aemond were in a real romantic relationship.

Anon refers to this POST.

Anyway, first this excuse of "maesters weren't there" is ridiculous. Some of these people argue for DaemonxNettles being true because Oberyn Martell in that reading of the Dance video says expresses that it is true. Yet Oberyn Martell wasn't alive for the Dance and thus never witnessed Daemon and Nettles interact for himself.

Secondly, Gyldayn was not there. Norren was not there. Septon Eustace was not there, Mushroom and Munkun were not there at Harrenhal to witness Alys Rivers and Aemond interact. Thus, by that logic that that person, travllingbunny, and others like them use to say that Aemond and Alys were not in a sexually exploitative relationship doesn't make any sense. That means I can just go out and say, Aemond never even killed the Strongs and that the all escaped in the night, but the masters never knew because they didn't see it and weren't there. I can argue that Aemond and Alys never met. I can eve argue that Alys never existed, that Daemon and Aemond never fight and died and just disappeared never to be seen again. What is the point of reading Fire and Blood at all if we're just going to say "maesters weren't there" as the only reason for our arguments for how the people the maesters wrote about in their histories would have acted and interacted?

Thirdly, again, that person and people like them are hypocrites and don't keep track of their own logic, because if you say that "maesters were not there" as your prime or only reason why Aemond and Alys were an actual item, then you yourself are still that very specific argument/conclusion based on the some events that are told through the writings of the very maesters you point blank say can't be trusted to tell the truth about Alys and Aemond!

So to connect my second and third reasons together, travllingbunny and others arguing the same are mostly likely just trying to get away with making the most ludicrous or discriminatory ideas about these characters and the narrative, to twist into something they want it to be more than a tally trying to find as much truth as possible. Perhaps even they do not even know that they are doing this, or at least "half conscious" about it. Because so much of it is bad faith arguments and going back on their own logic to present conclusions that they expect people to just believe....like what?!

Yes, most of the maesters who later write about the Dance were not there. That's is why it is our jobs as readers to think about context (real history and culture, ASoIaF lore, how GRRM writes, etc.) as well as inspect the language and narrative framing Gyldayn and other tellers use to contextualize and provide reasons as to why that character did that things at that time and said that thing at that time, and so on and so forth.

Even Gyldayn/GRRM tells us this: QUOTE #1 and QUOTE #2.

Septon Eustace and Mushroom do not always agree upon particulars, and at times their accounts are considerably at variance with one another, and with the court records and the chroniclers of Grand Maester Runciter and his successors. Yet their tales do explain much and more that might otherwise seem puzzling, and later accounts confirm enough of their stories to suggest that they contain at least some portion of truth. The question of what to believe and what to doubt remains for each student to decide.

#asoiaf asks to me#asoiaf#a song of ice and fire#hotd#house of the dragon#aemond targaryen#aemond's characterization#hotd characterization#characterization#fandom conflict#fire and blood sources#asoiaf maesters#maesters#gyldayn#maester gyldayn#fire and blood comment#asoiaf writing#fire and blood writing#historical writing#medieval history#medieval historical writing

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I hate the “Tiffany problem”

If you’re not aware, the “Tiffany problem” is the concept that someone writing historical fiction can include a detail that’s well-researched, but that the general public will think is crazy and unrealistic because of widely held beliefs about that particular era. It’s name is derived from the fact that the name “Tiffany” immediately conjures to mind some 1980′s cheerleader or, maybe, Audrey Hepburn, when it’s a name that goes all the way back to like the 12th freakin century.

For example, in the past men did sometimes take their wife’s surname. It was real. It happened. Now, the lady was usually very important and very wealthy, so this was by no means COMMON, but it did in fact happen.

But shoving this into a story sets off all kinds of alarms because no matter how you explain it you know SOMEONE is going to cry foul.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of my biggest nitpicks in fiction concerns the feeding of babies. Mothers dying during/shortly after childbirth or the baby being separated form the mother shortly after birth is pretty common in fiction. It is/was also common enough in real life, which is why I think a lot of writers/readers don't think too hard about this. however. Historically, the only reason the vast majority of babies survived being separated from their mother was because there was at least one other woman around to breastfeed them. Before modern formula, yes, people did use other substitutes, but they were rarely, if ever, nutritionally sufficient.

Newborns can't eat adult food. They can't really survive on animal milk. If your story takes place in a world before/without formula, a baby separated from its mother is going to either be nursed by someone else, or starve.

It doesn't have to be a huge plot point, but idk at least don't explicitly describe the situation as excluding the possibility of a wetnurse. "The father or the great grandmother or the neighbor man or the older sibling took and raised the baby completely alone in a cave for a year." Nope. That baby is dead I'm sorry. "The baby was kidnapped shortly after birth by a wizard and hidden away in a secret tower" um quick question was the wizard lactating? "The mother refused to see or touch her child after birth so the baby was left to the care of the ailing grandfather" the grandfather who made the necessary arrangements with women in the neighborhood, right? right? OR THAT GREAT OFFENDER "A newborn baby was left on the doorstep and they brought it in and took care of it no issues" What Are You Going to Feed That Baby. Hello?

Like. It's not impossible, but arrangements are going to have to be made. There are some logistics.

#idk what to tag this#worldbuilding#writing fiction#historical fiction#fantasy#a real-life example: my dad (a pediatrician) was once entrusted with the care of a baby who was born with a rare condition#this was in a place without great hospital/medical access and anyway they were going to fly the baby over#and he specifically asked them to bring the mother and baby#they show up with baby and...the baby's uncle#and he was like. y'all. do you think I asked for the mom to come just for fun??? We don't have formula here. what is the baby going to eat?

37K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, so to the surprise of many, I do in fact write stuff, so if you’re interested in a mixture of humor, wit, and maybe learning something from your fanfic reading, then check my works out. Or don’t, you have free agency.

#twisted wonderland#genshin impact#victory belles#fanfic#creative writing#historical writing#humor#ship girl#anzac#fire emblem three houses#second world war#first world war#samurai

1 note

·

View note

Text

He wanted to colonize the moon and I just wanted to dance.

I asked you a question, this one time when we were having our usual friendly chatter of politics, religion and science like we always used to do as kids. You used to be my favorite person in this world, we shared the same mind – or so I thought.

Remember that question I asked you? It was supposed to be a joke, a rhetorical question, I only meant to make you laugh, maybe a tad bit uncomfortable. I asked you what do you think the world would look like if your ancestors left mine alone?

I thought you would let out at least a chuckle, but you were silent. Not a sound heard. Your expression unreadable, I thought I went too far. Maybe I made you embarrassed, maybe you still carry some form of guilt, ashamed even. I would never shame you; you know that.

We could’ve sat down and imagine what the world would look like if wars and bloodshed didn’t shape history. What it would look like if those before us – before you – spent more time creating and preserving rather than slaughtering and stealing. We could’ve indulged on how different the world would be and maybe strive towards it together.

But you didn’t and if I ask you right at this moment, you still wouldn’t. You actually love what the world has become. You would’ve cheered for the bloodshed of my people and your complicity in silence today is telling enough. All this time, I thought you’ve seen right through me and considered me equal. But behind your facade you would prefer it I thank you and kiss the ground you walk on.

While I had to learn every heinous history from every corner of the earth – including mine and yours – with dreams no ugly injustice would ever repeat itself unto others, you sit there, pretentious with all the knowledge and false humanity you preach, only for it to mean absolutely nothing for you wish such evil to be repeated.

You’ve learned nothing.

0 notes

Text

*Writing a historical piece*: THEY DON'T KNOW THAT THIS WORD WOULD'VE HAD A DIFFERENT MEANING BACK THEN

1 note

·

View note

Text

all RIGHT:

Why You're Writing Medieval (and Medieval-Coded) Women Wrong: A RANT

(Or, For the Love of God, People, Stop Pretending Victorian Style Gender Roles Applied to All of History)

This is a problem I see alllll over the place - I'll be reading a medieval-coded book and the women will be told they aren't allowed to fight or learn or work, that they are only supposed to get married, keep house and have babies, &c &c.

If I point this out ppl will be like "yes but there was misogyny back then! women were treated terribly!" and OK. Stop right there.

By & large, what we as a culture think of as misogyny & patriarchy is the expression prevalent in Victorian times - not medieval. (And NO, this is not me blaming Victorians for their theme park version of "medieval history". This is me blaming 21st century people for being ignorant & refusing to do their homework).

Yes, there was misogyny in medieval times, but 1) in many ways it was actually markedly less severe than Victorian misogyny, tyvm - and 2) it was of a quite different type. (Disclaimer: I am speaking specifically of Frankish, Western European medieval women rather than those in other parts of the world. This applies to a lesser extent in Byzantium and I am still learning about women in the medieval Islamic world.)

So, here are the 2 vital things to remember about women when writing medieval or medieval-coded societies

FIRST. Where in Victorian times the primary axes of prejudice were gender and race - so that a male labourer had more rights than a female of the higher classes, and a middle class white man would be treated with more respect than an African or Indian dignitary - In medieval times, the primary axis of prejudice was, overwhelmingly, class. Thus, Frankish crusader knights arguably felt more solidarity with their Muslim opponents of knightly status, than they did their own peasants. Faith and age were also medieval axes of prejudice - children and young people were exploited ruthlessly, sent into war or marriage at 15 (boys) or 12 (girls). Gender was less important.

What this meant was that a medieval woman could expect - indeed demand - to be treated more or less the same way the men of her class were. Where no ancient legal obstacle existed, such as Salic law, a king's daughter could and did expect to rule, even after marriage.

Women of the knightly class could & did arm & fight - something that required a MASSIVE outlay of money, which was obviously at their discretion & disposal. See: Sichelgaita, Isabel de Conches, the unnamed women fighting in armour as knights during the Third Crusade, as recorded by Muslim chroniclers.

Tolkien's Eowyn is a great example of this medieval attitude to class trumping race: complaining that she's being told not to fight, she stresses her class: "I am of the house of Eorl & not a serving woman". She claims her rights, not as a woman, but as a member of the warrior class and the ruling family. Similarly in Renaissance Venice a doge protested the practice which saw 80% of noble women locked into convents for life: if these had been men they would have been "born to command & govern the world". Their class ought to have exempted them from discrimination on the basis of sex.

So, tip #1 for writing medieval women: remember that their class always outweighed their gender. They might be subordinate to the men within their own class, but not to those below.

SECOND. Whereas Victorians saw women's highest calling as marriage & children - the "angel in the house" ennobling & improving their men on a spiritual but rarely practical level - Medievals by contrast prized virginity/celibacy above marriage, seeing it as a way for women to transcend their sex. Often as nuns, saints, mystics; sometimes as warriors, queens, & ladies; always as businesswomen & merchants, women could & did forge their own paths in life

When Elizabeth I claimed to have "the heart & stomach of a king" & adopted the persona of the virgin queen, this was the norm she appealed to. Women could do things; they just had to prove they were Not Like Other Girls. By Elizabeth's time things were already changing: it was the Reformation that switched the ideal to marriage, & the Enlightenment that divorced femininity from reason, aggression & public life.

For more on this topic, read Katherine Hager's article "Endowed With Manly Courage: Medieval Perceptions of Women in Combat" on women who transcended gender to occupy a liminal space as warrior/virgin/saint.

So, tip #2: remember that for medieval women, wife and mother wasn't the ideal, virgin saint was the ideal. By proving yourself "not like other girls" you could gain significant autonomy & freedom.

Finally a bonus tip: if writing about medieval women, be sure to read writing on women's issues from the time so as to understand the terms in which these women spoke about & defended their ambitions. Start with Christine de Pisan.

I learned all this doing the reading for WATCHERS OF OUTREMER, my series of historical fantasy novels set in the medieval crusader states, which were dominated by strong medieval women! Book 5, THE HOUSE OF MOURNING (forthcoming 2023) will focus, to a greater extent than any other novel I've ever yet read or written, on the experience of women during the crusades - as warriors, captives, and political leaders. I can't wait to share it with you all!

#watchers of outremer#medieval history#the lady of kingdoms#the house of mourning#writing#writing fantasy#female characters#medieval women#eowyn#the lord of the rings#lotr#history#historical fiction#fantasy#writing tip#writing advice

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

19th Century Writing Tools

#historical writing#history#man suang fic inspiration#ancient stationary#quill pens#dip pens#brush pens#palm leaf stylus#stylus

1 note

·

View note