#pádraig ó tuama

Text

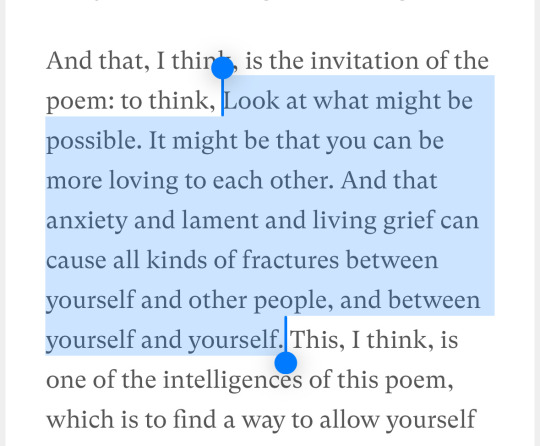

Pádraig Ó Tuama, on Rita Dove's poem "Eurydice, Turning" as featured in On Being: Poetry Unbound

#pádraig ó tuama#poetry unbound#rita dove#eurydice turning#words#interviews#typography#grief is a circular staircase#to be human#the great wound#id in alt text

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“In Irish when you talk about emotion, you don’t say, ‘I am sad’. You’d say, ‘sadness is on me’ ‘tá bron orm’.

And I love that because there’s an implication of not identifying yourself with the emotion fully. I am not sad, it’s just that sadness is on me for a while.

Something else will be on me another time, and that’s a good thing to recognise.”

—Pádraig Ó Tuama

3K notes

·

View notes

Quote

[Paul] Celan, whose parents were murdered at a camp in the Transnistria Governorate, translated Shakespeare while interned in a ghetto. For him, language was a project to be wrestled with. He believed it was possible for language to make something happen; and even if it didn’t make something happen, then at least it was worthwhile trying. He held people to account for loose language (his short correspondence with Heidegger, that phenomenologist, are extraordinary in their critique), and demanded that attention be paid to the impact that words can have in public.

Pádraig Ó Tuama, from his essay “The possibilities of language”, published at the Poetry Unbound substack, March 26, 2023

230 notes

·

View notes

Text

So much lurking in the silence of a poem and so much present in the text of it.

Desire, I think, is a portal where we look at the thing we want, but we also look at the other things that are gathered around that. And I don’t think I know of any better vehicle for holding all that together than poetry. In the lines of poetry, there’s so much said and so much implied, so much lurking in the silence of a poem and so much present in the text of it.

— Pádraig Ó Tuama, from the Poetry Unbound Podcast, “Yu Xiuhua | Crossing Half of China to Sleep with You” (via Poetry of Witness and Provocation)

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE LIFELINE

Here is what I know: when

that bell tolls again, I

need to go and make something,

anything: a poem, a pie, a terrible

scarf with my terrible knitting, I

need to write a letter, remind myself

of any little lifeline around me.

When death sounds, I forget most

of what I learnt before. I go below.

I compare my echoes with other people’s

happiness. I carve that hole in my own

chest again, pull out all my organs once

again, wonder if they’ll ever work again

stuff them back again. Begin. Again.

PÁDRAIG Ó TUAMA

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Someone for everyone in Brooklyn’s holy shop.

[Pádraig Ó Tuama]

* * * *

“Because here's something else that's weird but true: in the day-to day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshipping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship—be it JC or Allah, be it YHWH or the Wiccan Mother Goddess, or the Four Noble Truths, or some inviolable set of ethical principles—is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It's the truth. Worship your body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you. On one level, we all know this stuff already. It's been codified as myths, proverbs, clichés, epigrams, parables; the skeleton of every great story. The whole trick is keeping the truth up front in daily consciousness.”

― David Foster Wallace , This Is Water: Some Thoughts, Delivered on a Significant Occasion, about Living a Compassionate Life

+

“Never touch your idols: the gilding will stick to your fingers."

(Il ne faut pas toucher aux idoles: la dorure en reste aux mains.)”

― Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

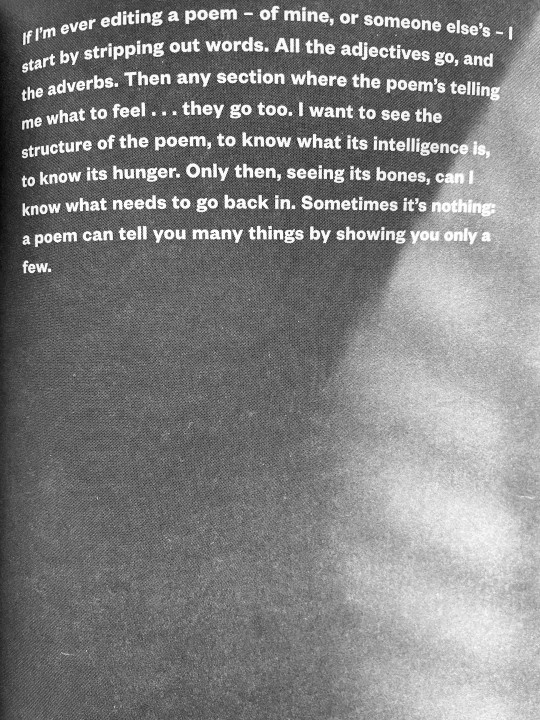

Pádraig Ó Tuama, from Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World (W.W. Norton & Company, 2023)

If I’m ever editing a poem - of mine, or someone else’s - I start by stripping out words. All the adjectives go, and the adverbs. Then any section where the poem’s telling me what to feel...they go too. I want to see the structure of the poem, to know what its intelligence is, to know its hunger. Only then, seeing its bones, can I know what needs to go back in. Sometimes it’s nothing: a poem can tell you many things by showing you only a few.

#pádraig ó tuama#poetry unbound#typography#books#editing#writing#poetry#i'm currently editing a huge batch of poems and i'm going to try this tactic

71 notes

·

View notes

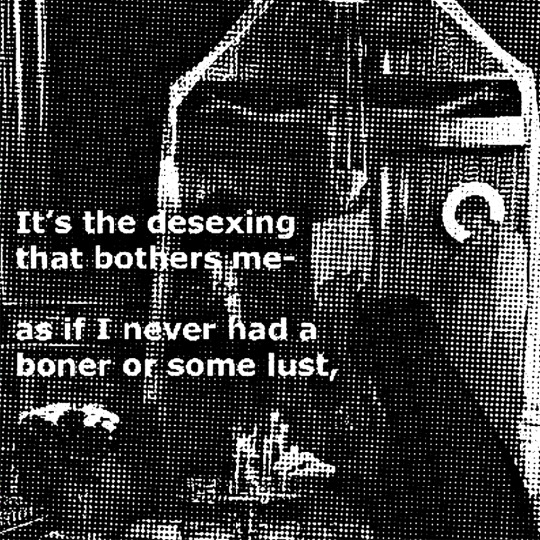

Photo

The poem “Jesus Desiring” by Pádraig Ó Tuama over pictures of Russian Orthodox worship.

Image descriptions:

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a Russian Orthodox nun lighting a candle in front of a large ikona of the crucifixion. There is white text on the image reading “It’s the desexing that bothers me- as if I never had a boner or some lust.”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a woman wearing a platochik kissing a crucifix held up by a priest. There is white text on the image reading “as if I had so much of God’s business to consider that I never wanted kisses“

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a Russian Orthodox priest stroking a wooden icon depicting Mary holding Jesus, with white on it reading “ or a nail run down my back.”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a Russian Orthodox priest entering the sanctuary at the back of a church, with an ikona of Christ on the right side. There is white text over the image reading “I woke every morning the way men wake every morning.”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a woman kissing the base of a crucifix, with white text on the image reading “I sought some comfort in some touch and thought that much could be achieved if people made more love more often.“

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a woman leaning her forehead against an ikona in a church, there is white text on the image reading “I think I’d have made a pretty average father, by which I meanokay,”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a woman wearing a platochik standing in front of the ikon covered wall seperating the sanctuary from the rest of the church. There is white text above her that reads “by which I mean I wish.”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of a man holding up an icon in a jewelled case. There is white text above him that reads “I would like to age and watch my children grow.”

A black and white halftone of a photograph of an ikona of the crucifixion with white text on it reading “I would like to hold on to my body.” End description.

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

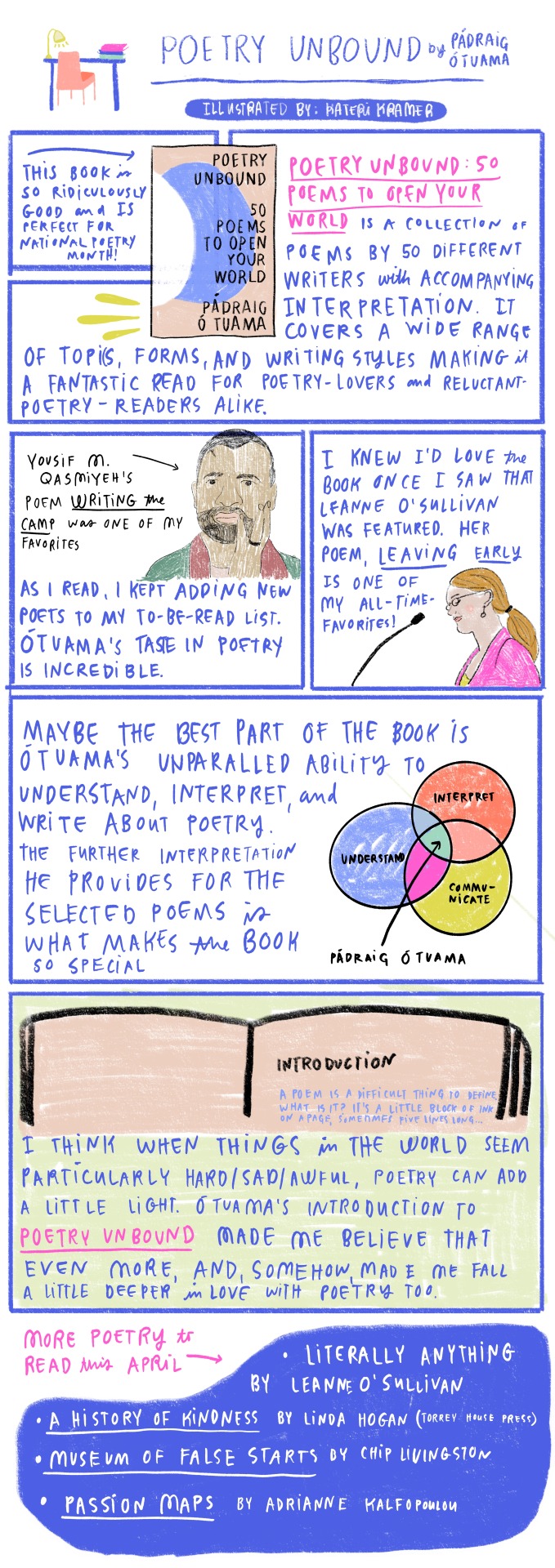

Sketch Book Reviews: Poetry Unbound by Pádraig Ó Tuama

Written and illustrated by Kateri Kramer

"This book is so ridiculously good and is perfect for National Poetry Month! Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World is a collection of poems by 50 different writers and accompanying interpretation. It covers a wide range of topics, forms, and writing styles making it a fantastic read for poetry-lovers and reluctant poetry-readers alike."

#therumpus#sketch book reviews#kateri kramer#comics#art#indielit#indiemagazine#book review#excerpt#literature#quotes#poetry unbound#Pádraig Ó Tuama

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ t h e ] n o r t h [ e r n ] [ o f ] i r e l a n d

Padraig Ó Tuama

It is both a dignity and

a difficulty

to live between these

names,

perceiving politics

in the syntax of

the state.

And at the end of the day,

the reality is

that whether we

change

or whether we stay

the same

these questions will

remain.

Who are we

to be

with one

another?

and

How are we

to be

with one

another?

and

What to do

with all those memories

of all those funerals?

and

What about those present

whose past was blasted

far beyond their

future?

I wake.

You wake.

She wakes.

He wakes.

They wake.

We Wake

and take

this troubled beauty forward.

#poetry#Pádraig Ó Tuama#northern ireland#north of ireland#community#conflict#peace#politics#statehood

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

My exorciser's eyes were nothing like the sun,

they had no fire...

...I have heard the furious from

the pulpit. This man's work as quiet as abuse. I loved

the promises he made, they wound around my

heart with knots of wonder....

....Some terrorise. He Christianised.

I swear to you his heaven rhymed with hell.

I know he'll claw his way to glory. Me as well.

from “(v) Volta” in “Seven Deadly Sonnets” in Feed the Beast by Pádraig Ó Tuama, p. 15

14 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Years ago, I had a colleague, Karen, and sometimes you’d say, “Well, how are you today, Karen?” And she’d say, “Oh, I’ve a bit of the Weltschmerz on me.” She was a great one for many languages. And I’d love the way that she’d do that. And I think there’s something about having a word for it, “Weltschmerz,” that allows you to realize that not all sadness comes from you, but sometimes you are just wearing the world’s sadness for a while and trying to figure out what to do with that.

Pádraig Ó Tuama, from the Poetry Unbound Podcast, ‘Carolina Ebeid | Reading Celan in a Subway Station’, published October 17, 2022

629 notes

·

View notes

Text

When death sounds, I forget most

of what I learnt before. I go below.

I compare my echoes with other people’s

happiness. I carve that hole in my own

chest again, pull out all my organs once

again, wonder if they’ll ever work again

stuff them back again. Begin. Again.

-Pádraig Ó Tuama

#Pádraig Ó Tuama#reading#literature#quotes#life#life quotes#quote#world#random beautiful stuff that i read#random quotes#stumbling on random beautiful quotes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Poetry Unbound: 50 Poems to Open Your World by Pádraig Ó Tuama

Important to remember that myth is not something flase, rather a myth is something with so much truth that it needs a fantastical container. (“Wonder Woman” by Ada Limón, p. 12)

***

Ghazals are written in couplets; from five up to fifteen. Sometimes a poem unfolds only one idea, but a ghazal holds many different ideas together. This is achieved by the repetition of a word at the end of every couplet — in this case, Mississippi. The ghazal is originally an Arabic form; ghazal is the way the word gazelle gets into English: an animal with speed and elegance, and that can change direction quickly. A ghazal poem can, too — the couplets go in many different directions, but the repeated word holds all the lines together.

Natasha Trethewey had a white father and a Black mother, and she’s written widely about how she was treated differently depending on where she was, or which parent she was with. If she was out with her father, she might be perceived as passing for white; if she was out with her mother, she might be treated better than her mother, because she was perceived as ‘less Black’ than her parent. Writing about this poem, Natasha Trethewey shared that for years she’d had unrelated ideas, like threads: the story of her name; the story of place; the story of the laws that affected her family, but she was unsure how to hold them together. When she realized a ghazal has couplets, but the couplets don’t have to follow directly on from each other — that it can spin different threads together with a repeated word — she understood that this was the form that could hold disparate experiences of her personal and political existence in shape. Through the repeated word in this poem — Mississippi — she holds beautiful and brutal things together: marriages and laws; departures and names; novels and history. Mississippi, Mississippi, Mississippi. . . .

The repeated word functions as a way of holding something to the light, seeing what it contains, both the wicked and the good. . . .

In formal ghazal poems, the poet always makes a reference — direct or obscure — to their own name, like a signature. . . . (“Miscegenation” by Natasha Trethewey, pp. 95-97)

***

The speaker of this poem knows how the body is the house of prayer, but also the house of distraction, describing the ‘tangible // hold of secular // trances’. The word trance comes from the Latin transire meaning ‘go across’. I find myself thinking of how tiring every day can sometimes be; and how it can be tiring even to think of doing restorative things like prayer. In the place of pursuits, Faisal Mohyuddin’s poem suggests a kind of prayer that is at once full of stillness and also full of movement: verbs like ‘stand’, ‘facing’, ‘submit’, ‘housed’, and ‘waiting’ make me think of composure; whereas ‘cascading’, ‘plunge’, ‘commune’, ‘burst’ and ‘beheld’ suggest movement, or perhaps exchange. The doing of this poem, then, brings practice into conversation with stillness; a stillness that contains exchange. Nothing is rushed, but nothing is static, either. (“Prayer” by Faisal Mohyuddin, p. 168)

***

What matters is that you pray, nothing else, Rilke suggests. Sometimes I’ve found his point of view intensely comforting; other times I’ve found it irritating. If this is a prayer, to whom is it addressed? Is God in the darkness of the hours, in the experience of the senses, in the ritual of finding a rhythm to a life, or in the imagination that allows ‘room / for a second life, timeless and wide’? Maybe God is the seed that led to the tree, and the self is the thing that finds the second life in the branches reaching to heaven. Maybe God is the embrace of the sad boy in its warm roots, holding together what nobody else could hold together. Maybe the boy is Rilke. (“from The Book of Hours” by Rainer Maria Rilke, p. 175)

***

Every poem deserves to be read multiple times. In a second — or third, or fourth — reading of ‘My Mother’s Body’, it becomes clear how often the simple word ‘her’ is used: her body, her feet, her womb, her bedsheets, her mouth, her wheelchair . . . nineteen times in total. The single-syllable sound of the word ‘her’ is a thread that holds the poem together. It’s like a familiar chord in a song, something that keeps you homed to a particular key. And so it is a piece of poetic brilliance that the final line doesn’t include it: ‘Our voice in my throat speaking to you now.’ It’s the only time the word ‘our’ appears in the poem. Nowhere else. (“My Mother’s Body” by Marie Howe, p. 203)

***

If I’m ever editing a poem — of mine, or someone else’s — I start by stripping out words. All the adjectives go, and the adverbs. Then any section where the poem’s telling me what to feel . . . they go too. I want to see the structure of the poem, to know what its intelligence is, to know its hunger. Only then, seeing its bones, can I know what needs to go back in. Sometimes it’s nothing: a poem can tell you many things by showing you only a few. (“In Leticia’s Kitchen Drawer” by Peggy Robles-Alvarado, p. 253)

***

Love poetry doesn’t try to describe the entirety of the love between the writer and their beloved, nor does it work as a manual for intimacy. Love poetry often opens up a story of love by looking at a single moment between lovers: a time of intimacy, or frustration; a description of the nape of their neck; the feel of their hand on your back; the space they leave in the bed when they’re away; the presence — or absence — of each other’s anxieties. (“Life Drawing” by R. A. Villanueva, p. 305)

***

It’s a courageous thing to add a new image into the final lines of a poem. . . .

Of the game Hide and Seek the British child psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott wrote, ‘it is a joy to be hidden, and a disaster not to be found.’ (“Consider the Hands that Write this Letter” by Aracelis Girmay, pp. 314-15)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Capilla de Santa Rita at dawn, Chimayó, NM. Photo: Gene Peach (2021)

[h/t Scott Horton]

* * * *

May we find our foundation in the work of Love; demanding, tiring, true and human and holy.

- Pádraig Ó Tuama

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m still thinking of Hayden Carruth’s poem, where — at the core — he is wondering about the purpose of language. In a recently released book, Words for War: New Poems from Ukraine, a Marjana Savka poem (translated from Ukrainian by Sibelan Forrester, Mary Kalyna, and Bohdan Pechenyak) begins with:

“Forgive me, darling, I’m not a fighter.”

The poet Marjana Savka doesn’t try to use words as weapons; instead, she looks at what she’d use a knife for (“to cut willow twigs” or “weave you a basket” or “to prune branches / On the young trees.”). It’s a dream, of course, this idea in the poem; but if nightmares can become realities, why would it be a waste of time to think dreams can, or could, or might? Poets aren’t positioning themselves as generals or politicians; they are positioning themselves as poets, which is always to pay attention to the made-ness of art, or the possibility that art can make something out of nothing, the strange beginning that might be worthwhile trying.

—Pádraig Ó Tuama, from "On language during a time of horror" (Poetry Unbound, October 15, 2023)

12 notes

·

View notes