#-they just live with the decapitated head of the mascot of one of the most popular franchises in the world

Text

Because it could never get out.

I think about Candy Cadets story a normal amount....

Cassie and Gregory having a sleepover when Cassie catches Gregory having a tier five Boy Moment™ with zero context

#my art#Chipillustrates#this is also practice for a short comic series I wanted to do with these guys#not pictured: Vanessa and Gregorys panic when they saw Cassie as they try to hide Freddy under a pillow because Cassie Does Not Know that-#-they just live with the decapitated head of the mascot of one of the most popular franchises in the world#fnaf#five nights at freddys#fnaf Gregory#fnaf Vanessa#fnaf Cassie#fnaf Candy Cadet#Fnaf Candy Cadet story#?#fnaf Security Breach#fnaf Security Breach Ruin#fnaf SB Ruin#Fnaf Ruin#Fnaf SB#hope I drew Cassies bonnet right- first time drawing one so I'll try n improve it next time!!#Cassie does NOT know what's going on with this family but she's doing her best to be supportive anyway<3#fnaf comic#fnaf fanart#3 star family#does this count as 3 star family?

457 notes

·

View notes

Note

☕️ transformation items in precure!

Overall I’m more tolerant for dumb designs with transformation items than in weapons so most of them get a positive or at least neutral reaction from me. However some still scream “we would never have used a design like this if it wasn’t for the toys”.

Let’s go through them all!

Futari wa Precure

Simple flip-phone like designs for the modern girl in 2004. I think these are alright enough but don’t raise a lot of emotions in me. Not a fan of the mascots transforming into items, like does the phone become a part of their body, that’s just creepy. I’d prefer if it was made clear that the phone is a separate item and the mascots just shrink to be able to fit in it. I prefer the original designs, the upgraded ones look busier.

Uhh... I got nothing on this. I guess it’s nice that the new girl gets an item that’s a bit different but also similar to the ones we already have.

Splash Star

Still got nothing, it’s the same thing again. Good that they started using different ideas from the fourth season onwards. I guess I prefer the Futari Wa ones since these somehow feel too small. Nice light? But let’s just say that while it’s just fine to use phone as a base for the transformation item, there’s quite many of them on this list and in general they are a bit boring when you can’t do anything else with them than press a few buttons in the beginning.

Yes! Precure 5

Simple design but it works, usually black is a good idea. Though it could do with some buttons because now it doesn’t look you can do much anything with this. It’s a nice detail how the henshin starts with the lid of the clock opening and ends with it closing.

Now we’re truly in the 00′s with the flip phones. I like how the henshin starts with the lid opening, and the rose button is cute. But there’s not a lot to say about this one and it’s pretty boring.

My second least favourite Precure transformation item. What is this even supposed to be? Some kind of makeup case? In that case I’d rather have the colous be actual makeup and not buttons. The handle also feels stupid.

Fresh Precure!

This doesn’t even try to pretend it’s not a phone, it even has the number buttons. Actually were the transformation items originally the Cures’ phones? Can they make regular phone calls with this? I’d like to see that. But this is cute enough, I can imagine that a real phone like this could have been popular with little girls. But maybe it could do with some extra detail to look more weird, now it feels a bit too mundane to be a magical girl item.

Heartcatch Precure!

I’m not a huge fan of beauty products in little girls’ shows, but they do make a lot of sense in a transformation sequence where you get to see the characters “apply” the magic themselves, and the fragrance bottles make for some great henshin animation and also fit a flower-themed season. I also like the white-and-gold palette, makes it look more regal than the usual shock pink.

I forgot this one even existed. I really can’t muster any emotion towards it, KiraKira did the compact mirror thing a lot better.

Suite Precure

Why are the colours pink-white-blue-purple and not yellow? I don’t have particularly strong feelings for this one in any direction, I guess on its own it’s a bit boring when it doesn’t resemble any real item I can recognise and you can’t do much else with it than press the button at the bottom, but I also think it’s fine to have an item like that every once a while. However I think the little mascot creatures that are needed to use this thing are uncute and that lowers the overall points.

Smile Precure!

Another makeup item, another chance for the characters to do the transformation themselves. I love the little tup tup! sound effect that comes from this. Otherwise great, but it’s just unacceptable that the canon Cures cover 5 of the coloured bead thingys but we don’t get a red or purple Cure. False marketing I say.

Doki doki! Precure

The mascot-items are back and I’m still not a fan of this living-creature-turns-into-hard-plastic-device thing. It’s a phone, but it’s also too bulky to comfortably feel like one. But I really like how they spell L-O-V-E with the heart, I thought that was creative.

They tried to make Ace all cool and mature and then her transformation item is the most kiddy-looking TOY makeup box ever. Even if the merch is plastic can’d she at least have actual makeup in the henshin? And what’s with the button colours, sure they’re the team colours this time, but the other Cures don’t even use this item.

Happiness Charge Precure!

The idea that the Cures can choose different cards to insert is a super fun one, and it’s also nice that they can use it for more mundane outfit changes outside battle scenes too. The writing around the cards is atrocious though but that’s another story. As for the design of the device itself, I think it’s pretty weak, it’s somehow bulky and not very memorable.

Probably my least favourite item from this bunch. The Piano is yet another unrelated thing that is shoved into HapiCha’s confused world, there is nothing about making music in the themes of the season, or Iona as a character. I hate that this thing is the culmination of Hime and Iona’s character arcs. Also the design looks really cheap and the animation where Iona presses a couple keys to get sounds that don’t even try to hide that this is just a toy for three-year-olds wastes time.

Go! Princess Precure

Another makeup item. At least perfumes fit the princess theme... But Go!Pri has the best henshin scenes in Precure, and the Cures applying the tranformation themselves plays a part in that. I also love how they start the transformation by filling the bottle with their theme colour, and the little twist they do with the key is a nice change from the usual button presses. And like with Heartcatch white and gold makes for a good regal colour palette. I think you could get an actual pretty fragrance bottle for grownups with this design if you did it with glass rather than plastic.

Also there are the keys which I love because of course I’m going to love collectible frilly dress items. They give each transformation and attack something unique and I like the bit where all the keys show up in a chain at the end of the henshin (and thankfully otherwise hidden under frills so you don’t need to draw them every time), and it’s nice to get the lock-and-key theme to the henshin as well. So once again Go!Pri is the best Precure at something and now gets the award for Best Precure Transformation item.

(god flora is so cute in this frame)

Mahou Tsukai Precure!

My bias that ever since I was a kid I’ve never really liked teddy bears comes to play here. The idea that the Cures don’t have a distinct transformation item at all is fun and the jewel theme is nice too, but I’m just filled with negative emotions whenever I see Mofurun... I haven’t seen MahouTsukai outside the henshin scenes so who knows if she’ll turn out to be my favourite character (and not just by process of elimination from me disliking everyone else more)

Not a big fan of this one, is it supposed to be a smartphone, or do they have some kind of smart notebooks in Japan? Either way it doesn’t really fit witches or flower fairies. All the little engravings are pretty and the flowers are cute, but overall this feels just random.

Kira Kira Precure a la Mode

Mixing the attributes the character represents with a magic whisk and then transforming by covering yourself with the whipped cream is a super fun idea, and also one of the few Precure transformations where the girls apply the transformation themselves that is not based on beauty products. Or I guess this is a pocket mirror too but whatever. The item itself is fun and cute enough.

However as those who saw my Ichika fanart a few days ago I really really really don’t like that they have to fiddle with the pathetic tiny q-tip of a whisk, give them one the size of a microphone so they can put some strength into it!

Hugtto! Precure

I love how you can twist the end to make a heart, if I had one of these I’d click it back and forth while sitting at the computer and the hinges would be busted in no time. The grey things at the edge of the screen could be some other colour, now they look a bit like they’re made of rocks. I don’t think this one does anything special but it’s just so cute that I have to love it.

Star Twinkle Precure

These are fun but a bit wasted on a season that has nothing to do with art. But otherwise A+ idea, very active participation from the girls when they draw almost everything in their new look, and it’s not makeup-based. Quill and ink bottle are the most magical writing apparatus so that’s very fitting, and thanks to the space theme we get some stars too so it’s not just the usual hearts. The pink tone is a bit gaudy.

Healin’ Good Precure

And we end on a weaker note with mascot items again. And these are my least favourites since to me they come across as if they have the dead-eyed animals’ decapitated heads sticking out of them. The paws also feel somehow unbalanced, and should not be pink for the blue and yellow items. The bottles feel tacked on too.

I feel that the mascots have been treated a bit better than average in Healin’ Good so I suppose it’s not bad that they get to be involved with the fights too (It’s nice that the item is also used as a weapon) but I would really rethink the design since now I don’t think the different elements go too well together and the result feels unbalanced.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Clary the Vampire Slayer

Read on AO3

“So, is this your defense? Your faith?” Camille spits out grabbing for the cross in Clary’s outstretched hand. It catches fire immediately from her touch and Clary hurrahs inside her head discreetly popping the lid off the small canister of hairspray behind her back.

“No,” she smirks bringing the cannister up and spraying it onto the flames. “My keen fashion sense.”

Camille screams engulfed in flames, falling to the ground beside her lame little lackey already dead on the ground with a stake protruding from his chest.

Clary watches as her opponent burns, her body dissolving into a crispy pile of ash right before her.

“Ouch!” she says dropping the still burning cross as the flames lick at her fingertips, she throws the mostly empty hairspray cannister down as well. Bringing a bag of weapons and an extra pair of comfortable shoes to this dance hadn’t been a mistake after all it seems.

She looks down at herself, her pretty white dress isn’t too white anymore, what once was floor length now rests above her knees and one strap is completely gone. The right leg of her tights are torn to hell, but the leather jacket she’d borrowed from her sort of girlfriend still seems to be intact.

Above her in the school gym she no longer hears the sounds of fighting and screaming, the revving of car engines driving away from the scene and nearing sirens have taken over. She had taken out most of the vampires in the gym before chasing after Camille to put a stop to her reign of terror, and from the sound of things Maia has finished what she started.

Maia.

Clary runs to the stairs taking them two at a time. She busts open the double doors of the gym surveying the mess. Windows are busted, ‘Don’t Tread on Me’ themed decorations are everywhere, paper flowers ironically litter the ground and their school mascots decapitated head sits beside numerous staked bodies of vampires.

Some students are scattered around still, watching as their principal hands out detention slips to the dead bodies. Whether he’s gone insane after the nights events or he really, genuinely thinks they’re just meth kids faking it Clary isn’t sure.

Lydia, her former friend and boyfriend stealer, cowers in the corner literally using a line of other students to blockade her from any danger that is now long gone. Jace, her ex, is nowhere in sight, likely having run from the scene the second things got even slightly scary.

Clary just rolls her eyes searching for the one person she wants to find in all this mess. A groaning noise comes from under an overturned table catching her attention.

She walks over quickly, slipping for a second on the long laces of her cheer sneakers. She flips the table after she recovers and there still groaning, looking more annoyed than actually injured is Maia. Beautiful, strange yet bold Maia who’d showed up tonight with her hair braided back on one side, dressed in black slacks that fit just right with her own bag of weapons and asked Clary to dance despite the fact she considered the whole concept of high school dances idiotic.

Maia is the exact opposite of the world Clary was living in just weeks ago. But meeting her Watcher, now dead thanks to Camille, had changed everything. The shallow world of boys and clothes she was living in didn’t matter now that she knew she was the chosen one, a slayer. One girl in all the world destine to fight the vampires that secretly plague the world.

Maia had stumbled into this world by accident a near victim of it and she’d chosen to stay, even if Clary hadn’t been the most welcoming to the idea at first. With Clary’s natural skill and Maia’s stubborn determination they make a pretty damn good team.

Clary smiles throwing her legs over Maia and crouching down to settle on Maia’s legs comfortably.

“Maia?” she says. Reaching out to poke at her.

“Ugh, I used to be,” she groans attempting to lift herself up. Clary reaches out so she’s sitting upright, grabbing her by the vest that’s missing a few buttons now.

Maia’s eyes finally open up, she looks Clary up and down.

“You okay?” she asks after a moment.

“Yeah I’m okay,” Clary lifts a hand brushing some fake paper mâché leaves from Maia’s hair. “Are you okay?”

“Yeah,” she replies twisting her neck from side to side. “Just one problem, I can’t feel my legs.”

Clary’s eyes go wide, “Why?”

“Cause you’re sitting on em’,” Maia says with raised eyebrows. Clary snorts, oh yeah. She lifts herself off of Maia’s legs pulling her up so they stand side by side.

“Did we win?” Maia asks once she’s upright stretching out her back now.

Clary nods the affirmative. Maia tilts her head looking at the destroyed gym around them.

“Did I do all that?” she lifts a hand waving it around gesturing at the scene.

Clary scrunches up her nose, “No.”

She sighs, “Did you do all of that?”

“Yeah, yeah I did,” Clary lets out with a small chuckle.

Maia reaches down grabbing Clary’s hand, pulling her to the center of the gym floor. The remaining students file out around them as the sirens get closer and closer.

“I saved you a dance,” Maia says once they’re standing face to face. “Seeing as we didn’t really get to finish that one earlier.”

Clary bites her lip thinking of the dance and the sweet, perfect first kiss that had followed, only to be interrupted by a hoard of blood sucking fiends.

“So, you gonna ask me?” she says, Maia already pulling her in close by the waist. Clary’s arms go up around her shoulders automatically resting her head against Maia’s.

There’s no music around them, the DJ station and the vampire who’d taken it over long dead, so they sway to the sounds of nearing sirens. They stay there embraced in each other’s arms until the screeching of police cars sound outside.

Maia lifts her head eyes intent on the other side of the gym, “Oh, shit.” Clary turns seeing the flames rising up from the basement that have caused Maia’s alarm.

The cross. The hairspray. There’s a chance Clary is about to be responsible for burning down her high school gymnasium on top of everything else they’re sure to pin on her. Which, okay technically it is all her fault, but still can’t a teenage girl catch a break these days?

“We gotta go,” Maia laughs tugging on Clary’s arm and dragging her out the backside double doors.

Maia hops on her bike flipping the kickstand and revving it to a start. Clary slides on behind her, arms secure around Maia’s waist. Maia looks back at her for a second a smile on her lips.

Clary just smiles back.

“So, I’m probably gonna get expelled,” she says.

“Great, that means you’re free all day,” Maia laughs revving the engine one more time before taking off. Out front they bypass everyone, driving through the crowd and commotion of emergency service vehicles and news cameras.

Clary takes one last look back at her high school before Maia turns the corner. She doesn’t know where she’s going or what happens next, but she knows that just because she’s the chosen one it doesn’t mean she’ll have to be alone in it all.

#my fic#claia#clary fray#maia roberts#shadowhunters#claia fic#i just love buffy and i love claia so i combined them

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Backlog Post: MG Spec-Ops Asuka Ep 4

Good to see you, friends!

I’m glad you stopped by. You see I think I’ve uncovered the secret as to why I’m so torn on this series, particularly in the writing department.

That’s right, Squeenix is involved. Don’t get me wrong I like a fair few of the Final Fantasy games. I really need to finish Bravely Default one day, and FMA is one of the godfathers of anime, but we all have to admit that Squeenix has a troubled history with good stories. Granted, they’re just the manga publishers so it’s not like they’re directly responsible for the writing, but the fact that their name is attached to a product where I’m iffy on the writing just makes too much sense to me.

Now at this point you may be wondering, “Fic, don’t you research the shows you plan to watch?”

To which I can only respond: “I’m a dragon living in an extra-dimensional library in need of occasional maintenance or else other realities start bleeding in,” followed swiftly by, “Of course I do research on the shows I want to watch. Would you like to see that research?”

And that’s how I came to watch Magical Girl Spec-Ops Asuka.

Synopsis: This episode is basically all about the world-plot all the time. Even in so far as the character plot is concerned so no extra synopsis this week. Essentially we pick up where we left off with Sporty having been kidnapped by the Babel Brigands. Things seem like they’re going to get right down to the action, but first we get a flash-back nightmare sequence!

[Cue Wayne’s World Flashback transition]

During the war Magical girl’s actually died. Including the original leader of the Magical Girl team who was named Francine. She actually died in Asuka’s arms since the group hadn’t found her in time for Stalker Nurse to do anything to help. She told Asuka to take over the team and remember that no matter how much horrible shit is in this world it also has beautiful things in it. It’s a really touching scene… Too bad the show doesn’t remember the “there are beautiful things too” bit.

[Flash forward]

So, you want to know what the response of the Police Brass’s response to the kidnapping of a high-ranking officer’s daughter happens to be? What with all the Magical nonsense going on and all you’d think maybe they’d have a response team for this sort of thing. Or maybe they’d open communication with the offending party and offer an exchange of hostages seeing as Mophead Mcterrorist is still kicking around. Or, you know, anything? They are Police even if they do have a different name. I presume they’re still there to protect and serve in some capacity even if that idea isn’t associated with the Japanese police the same way it is in the states. No, that’s not what happens at all.

When the concerned father comes to his superior about the situation concerning his kidnapped daughter what does she tell him?

Allow me to elaborate just a bit. Boss-lady here tells Sporty’s dad that they can’t go up against Mophead’s organization because of the risk they have more killer mascot kaiju which, fair enough, that makes sense. However, she then goes on to say that they can’t go running to the JSDF for help because this is too small an issue. BUT if they let this man’s DAUGHTER DIE then they can get a massive budget from the government which should somehow allow them to overcome giant killer plush-toys.

NO! BAD SHOW! You JUST got done telling us there was beauty in the world worth defending. Oh, right, my mistake you DIDN’T get done telling us that I skipped ahead a bit. No what really followed on the heels of the PTSDream was a scene of Sporty all trussed up while “I need Scissors 61” talks about ‘grilled meat’ a whole lot, and basically works to creep Sporty the fuck out.

Back to the failure of Bureaucracy: At the same time or very nearly to the meeting at the police headquarters, Asuka is being told about the situation and how the Police won’t be intervening. She asks what the super-special-magic combat squad for the SDF is going to do and Cyborg Dude’s all like, “Nothing we can’t act without a police request. BUT if a magical girl were to JUST HAPPEN to SHOW UP OF HER OWN VOLITION and a MAGICAL FIGHT were to break out then the incident might escalate to a point where we would be called on to intervene. HINT. HINT.”

So Asuka and Stalker Nurse say they’re going to head out and OH YEAH this is what I’m talking about. Give us half an epis-

What?

What!?

WHAT!?

Oh yes, friends, we get to spend 4-5 minutes of the episode in the basement with Heckel, Jeckel, “I need scissors 61”, while Sporty is tortured. I suppose I should be fair and say that a large portion of that time is filled with exposition on the villains. The most important tidbit being that this whole operation was aimed at luring out magical girls to take one captive in order to create what ‘I need scissors 61’ calls “A Girl of Mass Destruction”. HOWEVER, we’re still getting all this information while Sporty is stripped down to her… Sporty wear, tied to a wooden horse, and BEING FUCKING TORTURED! Even if it is in small bursts it’s still freaking chilling.

So yeah, we don’t get half an episode of the Magical Girls kicking terrorist ass to rescue their friend. Instead we get to see them take down a grand total of one doorknob, one wire trap, and three guards before they get to the trussed up Sporty.

‘I need scissors 61’ is all like, “Hello my dears I’ll be your transparently evil sadist for the evening. By the way I hope all the bondage and guro fetishists in the audience are getting off on what, for them, must amount to softcore.”

Asuka’s fires back with, “Okay, dirtbag, let our friend go and I won’t kill your ass then send the rest of you to kiss it in hell.”

“Let her go,” Says Scissor-bitch, “Why certainly.”

And she CUTS OFF SPORTY’S LEFT ARM! What grinds my gears the most is that she even makes the stupid fake-cutesy. “Woops I totally meant to cut the chains and missed. Tee-hee.”

So official psycho bitch orders the magical girls to put down their weapons or she’ll straight up decapitate the hostage, and at this point I’m SO happy that these are Magical Girls and not gritty Nineties military characters who would be like “go ahead, princess, make my day”. So Asuka makes a show of dropping her Karambit…. At which point the pair proceed to kick ass. Kurumi fires the massive needle-point on her primary weapon through ‘I need scissors 61’s shoulder pinning her to the wall and through a combination of swift action and a magical flashbang theys coop up Sporty sans one arm and make their getaway.

Naturally Runs-With-Scissors is pissed so she and the Ruski’s (Oh yeah the two people helping her torture an adolescent girl are Russian Mercenary Sorcerers) go and chase after the fleeing magical girls. Asuka stayed behind to try and hold them off, but of course Scissor-girl sics the Ruskis on her and chases after War Nurse on her own. We get a teensy bit more action and expository dialouge and that’s where the episode ends. Now I’ve got some serious…

Thoughts: Now to devil’s advocate it’s not wholly inappropriate that the torture scene take place. I’m bringing prejudice to the table based on what I expect out of a usual Magical Girl Show which is made for a MUCH DIFFERENT target demographic. Honestly along with more fanservice one should go into a Seinen show expecting more grim or edgy aspects to take the forefront. My problem is that those sorts of aspects don’t necessarily make a show more mature.

I guess I’ll never get over it, but Madoka was a perfectly mature take on the Magical Girl template that didn’t need a lot of edgy gory content or blatant spank material. This show seems to not know what the audience for it would want. I came into this thinking “Military Magical Girls in a series whose rating might allow them to actually show the horrors of war? That seems neat.” What I got was a post-war series that doesn’t seem to know if it wants to be about the trauma endured by what effectively child soldiers; a story about a war hero fighting to live a somewhat normal live while realizing the responsibility they have to keep fighting the good fight; pandering to the various circles who would find under-dressed young women attractive; softcore fetish porn; or any of a number of other things.

At the end of the day what did the torture scene serve? What purpose did it have? Was it important to the narrative that we see it? No… No it wasn’t. All it did was show us that one of the Ruski’s has a water Persona and the other likes to heat metal implements and is referred to as a chef. These are things that could have been exposited in combat, and I get that’s more a shounen thing but it doesn’t make the point any less valid. As for the explanation of what Babelfish wanted a Magical Girl for they could have moved that up to when Scissor-girl was tormenting Sporty with grilled meat earlier, or moved back to the classic villainous monologue after our heroes had arrived. If there had been even an iota of reason for the torture scene. Then I probably wouldn’t be this mad, because strong emotional reactions are what I look for to see if a piece of media is doing its job well. Getting angry at a story doesn’t immediately indicate that it’s bad. It’s when you’re mad for reasons other than those specifically written that we have a problem.

I didn’t see the torture scene this episode and think “Those monsters! I want to wring their necks!”

… Okay yes I did, but the problem is that I also asked a question: “Why is this here?”

Having a villain do an evil thing because they are wicked makes sense. SHOWING us them doing said evil thing has to have a narrative reason beyond just “Oh they’re the evil villain!”

Okay… I think I’m starting to repeat myself on that point so let’s talk about the other concern I have. The Flashback PTSDream implies that Asuka is driven to fight by the fact that despite how bad things can be there are still things worth protecting in the world. The problem, as I said in the synopsis, is that the show seems to have missed the memo on that. On the contrary the world is a place where young women get kidnapped and tortured, war heroes can’t get a good night’s sleep, and even the people who SHOULD be the good guys come across as evil schemers.

I know I skipped over the fact that the Police Lady and Cyborg-Scarface were actively manipulating Asuka and Stalker-Nurse into action, but so far as Sporty’s dad knows his boss is someone who’s willing to sacrifice a subordinate’s daughter to get a BUDGET BUMP!

If you’re going to stand on the premise that there are things worth protecting in the world you need to actually SHOW US THOSE THINGS!

“But, Fic, There’s Sporty and Bookish! They’re worth protecting!”

Yes, how very astute. Innocents ARE worth protecting. However, what about the WORLD makes it worth the Magical Girls’ efforts? Where is the beauty that Francine loved? We should have seen at least a sliver of it in this episode.

[Sigh] I stepped away from this post for a while to clear my head and I can’t come up with a positive note to end on. Oh well. I suppose we’ll just have to look forward to other things. Hopefully the future of this show will balance things out, but I know I’ll have fun digging my claws into it regardless.

That said: Until next post keep talking fiction, friends! I’ll see you soon.

P.S.: This week’s Spec-Ops will be posted later this evening. I need to take some time to myself first.

#Anime#Let's Talk Anime#mahou shoujo tokushusen asuka#Magical Girl Spec-Ops Asuka#Fictionerd#In-Character#Winter 2019#Winter Season 2019#Winter Anime 2019

1 note

·

View note

Text

Now, full disclosure, the naming theme for my sweet boys was guessed some time ago. As such, I have no problem now saying that the theme was... the thing the Pokemon is based on. Since some of them are a little obtuse, I thought I'd go through and just name every single one throughout the entire playthrough. Fun!

Minos - Wartortle is base on the Minogame, a mythical turtle said to grow a tail after living for a very long time.

Horus - The Pidgey line, besides various birds, resembles Horus, the Egyptian bird god, and the Eye of Horus in particular.

Pincho - Raticate, among other large rodents, resembles a capybara. Are there other rodents it resembles more? Yes. But capybaras are cool. And they're also known as carpincho.

Xuth - Caterpie is plainly based on the Asian swallowtail caterpillar, from its coloration to its markings to its prominent osmeterium. The species name for the Asian swallowtail is Papilio xuthus.

Vlad - A few levels removed, but Zubat is based on vampire bats, which are called that due to their similar pattern of hematophagy as the mythical vampire. Dracula, the most famous vampire in popular culture, is based on Vlad the Impaler.

Lanius - Spearow, besides a sparrow, has the hooked beak of a Lanius shrike.

Penthes - Bellsprout's family is based on pitcher plants. One of the two most species-rich families of pitcher plants, including the ones that Victreebel most directly resembles, are of the family Nepenthes.

Maneki - Meowth, with its head-mounted coin and signature move Pay Day, is pretty clearly based on the beckoning cat, a commonly seen statue representing good fortune, and in the original Japanese, called Maneki Neko.

Whaca - Diglett isn't just a mole... it's a Whac-A-Mole.

Cingu - The order to which armored mammals such as armadillos (one of Sandshrew's origins) belong is Cingulata.

Bara - As before, this is for the capybara.

Mick - Voltorb's role in the Power Plant is to decieve the player into believing that a powerful monster is in fact a treasure. In other words, it fills the same niche as a Mimic.

Moschops - Machop's name and face resemble that of the extinct synapsid genus Moschops.

Kitan - Vulpix is of course based on the kitsune. -tan is a childish Japanese honorific denoting something as cute and mascot like, and also that gives it the same name as the Zelda kitsune, the Keaton. Vulpix is an immature kitsune, so I'm using essentially the same logic.

Imugi - Dragonair's entire design is based on the Imugi, a serpent that would gain pearls and become a dragon in Korean folklore.

Sogenbi - Gastly resembles a Japanese yokai said to be the decapitated head of a monk wreathed in flame, called the sōgen bi.

Bernie - Snorlax is based on the habits of bears, which hibernate, eating a lot of food and then sleeping for a long time. HiBERNate.

Tad - Poliwag is a tadpole.

:) - According to Junichi Masuda and Ken Sugimori, Ditto was originally based on the smiley face. :)

Arctid - Arctiidae is a family of moths with similarly poisonous properties to Venomoth due to their diets.

Moa - It's literally just the name of an extinct, large flightless bird which Doduo resembles.

Matsya - The fish avatar of Vishnu, which Goldeen particularly resembles given its horn.

Sciari - Sciaridae are flies which Venonat resembles the larva of.

Aster - I didn't actually mention this name when I mentioned catching the Staryu, huh? Anyway, Staryu is based on sea stars of the class Asteroidea.

Harp - Seel is based on the harp seal!

Okeefe - Cloyster is very clearly based on a Georgia O'keefe painting.

Ooze - It's. Uh. It's ooze.

Wakinyan - According to a website, Wakinyan is the traditional Sioux name for the thunderbird of Native American mythology.

Baku - Drowzee and Hypno are based on the Japanese myth of the baku, a tapir-like creature that devours dreams.

Desmod - The common vampire bat is the desmodus rotundus.

Campus - The seahorse is also called the hippocampus, from the Latin words meaning "horse" and "sea monster".

There ya go. With the exception of whatever crazy thing the Cerulean Cave has in store for me, that's all the names explained.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gus, the 2000 Year Old Man

I've just about run out of decapitation jokes and puns, so let's move a head to our next destination, which is only a few feet away. This is yet another in our series of probes for the ultimate inspirations and cultural roots of the Mansion residents. This one seems like a slam dunk, or is it your imagination, hmm?

Seems like a pretty good match, doesn't it? Of course the "chain" detail is slightly different, but otherwise that sounds a lot like "Gus," as the little prisoner is known. ("Gus," "Ezra," and "Phineas" were names given to the hitchhikers by a veteran Cast Member at WDW, and they've stuck, climbing to the level of official Disney sanction.) Anyway, the description comes from an almost 2000-year-old ghost story, well-known and often cited in surveys of beliefs about ghosts and spirits throughout history. The story is in a letter by Pliny the Younger (ca. 62—113 AD). You can read it HERE. It's in a stuffy, Edwardian English translation (the only one in the public domain), so take your time, or else you can make do with this synopsis.

Pliny wants to know his friend's opinion about whether ghosts exist or not. He relates several examples he has heard of supernatural visitations purported to be genuine. The longest and most interesting is about a haunted house in Athens. A chain-rattling ghost, as described above, terrified the owners so much that they abandoned the place, and no one would live there. It was put up for rent, and a Stoic philosopher, curious as to why such a nice house was renting so cheap, learned the story and decided to take the place. He stayed up late, alone, writing, and sure enough the ghost appeared, rattling its chains. The philosopher pretended to ignore it, but the ghost only rattled louder and closer, beckoning the man to follow him. The philosopher obliged, and after reaching a certain spot, the ghost vanished. The philosopher marked it, and the next day he had the police dig it up. They found the skeleton of a man chained like the ghost, had him properly buried, and the hauntings ceased.

Pliny the Younger. No, it doesn't sing.

For our purposes, the main point here is that Pliny's famous letter would likely have been part of the research into ghost lore that the Imagineers did when they were working on the Haunted Mansion. Considering how well Pliny's ghost matches dear old Gus, we might be tempted to conclude that we have found Gus's archetype. But it's not that easy.

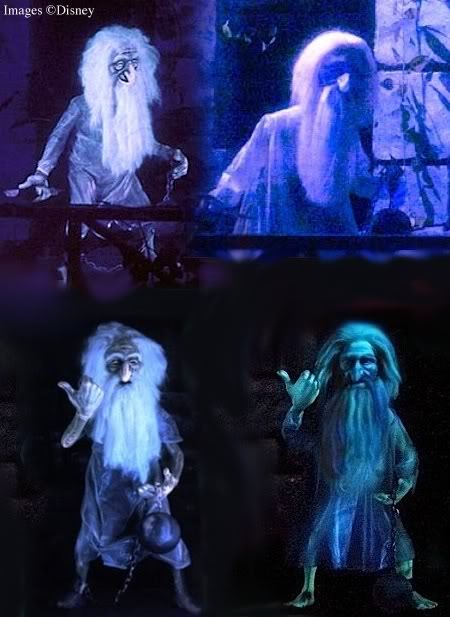

It's true that the Gus we see in the ride today looks a lot like Pliny's ghost, and he always has. Gus has changed very little over the past 40 years (unlike some others who have had noticeable hair and costume alterations), and he looks the same in both of his HM appearances, as part of the headsman trio and as one of the hitchhikers. Here he is in 1969 (left) and today (right).

Heh. Notice that somewhere along the line they quietly fixed the original costume discrepancy?

In 1969 he was long-sleeved in the headsman trio and short-sleeved as a hitchhiker. Quelle horreur!

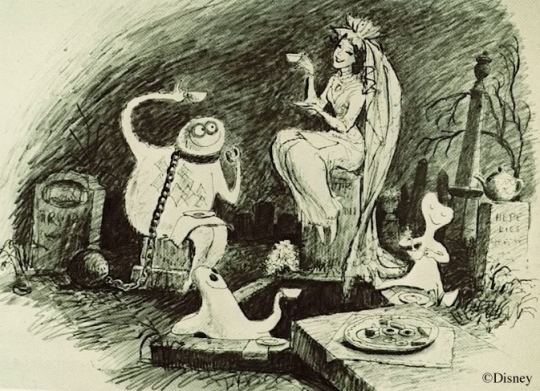

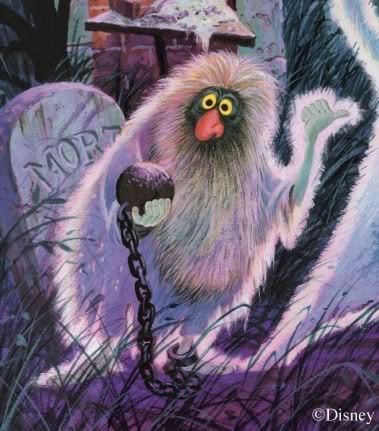

The problem is that the further back you go from this finished Gus figure to his origins on the drawing board, the less he looks like Pliny's ghost. That's the opposite of the case we have seen with others, where the original inspiration is unrecognizable by the time it reaches the ride (The Raynham Lady —> the Attic Bride; the Tedworth Drummer —> the Graveyard Band). Gus started out as a pudgy blob, chained at the neck.

That evolved into the character we know so well from Marc Davis's sketches:

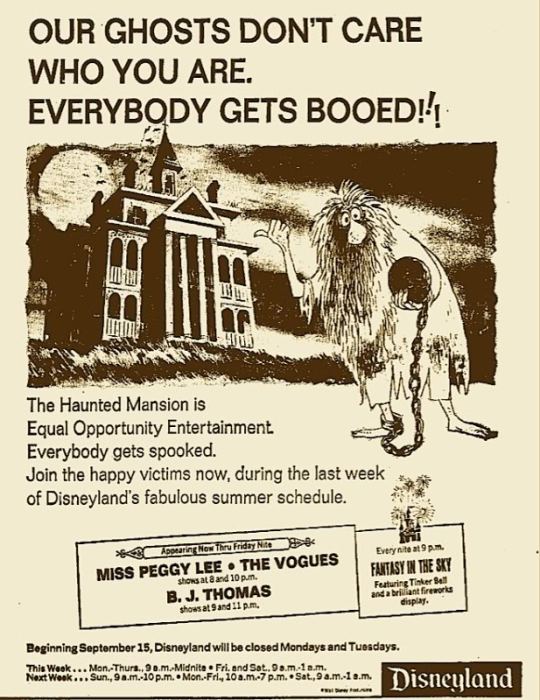

By the way, here we have an example of how good Marc's instincts were. It's obvious today that the hitchhiking ghosts are THE iconic characters of the HM, but how obvious was it in the beginning? There were a lot of candidates, but Davis somehow knew that Gus was the best choice for Mansion mascot, and he gave him that role right off the vampire bat, as we have seen in the early ads he drew.

I like this ad. It's snotty. And look at the acts they had back in the day...

Anyway, he looks like an avocado wearing a Barney Rubble costume. He's still this odd-shaped, pudgy-looking character. When Collin Campbell painted his interpretation of Gus, based on Marc's sketch, "emaciated" clearly wasn't in the job description as far as he could see.

With the maquette figure, we can see that Gus has acquired a real skeleton and is now on his way to scrawny, although he isn't quite there yet.

It is only with the final show figure that Gus is unambiguously a skinny old bloke. So if Pliny's ghost is laid under contribution, it would be interesting to learn how it influenced the final design. Maybe we should look over the shoulder of Blaine Gibson or someone like that to see what they were reading.

More Gus Talk

Just for fun. How many of you have never noticed that the Gus of the headsman trio is holding a file, just as he is in one of Marc Davis's sketches. Thanks to the railing in front of him, the file is hard to see, even in many photos.

(Tip 'o the hat to Brandon for the photo)

I don't know if it's a coincidence, but all three members of the headsman trio are holding cutting tools appropriate to their professions. "I'm a knight, and with this sword I vanquish evildoers." "I'm an executioner, and with this axe I mete out justice to criminals and enemies of the state." "I'm a prisoner, and with this file—I escape! HA!"

Gus is also the most fleet-footed ghost in the graveyard, zipping from the headsman trio to the hitchhiking trio with lightning speed—too fast to see—and from there into your buggy (33.3% chance) with the same velocity. Speed, he is speed. So...the fastest ghost around is the one wearing a ball-and-frickin-chain. How droll is that?

Originally Posted: Saturday, July 10, 2010

Original Link: [x]

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pigeons, punches & tattoos - the addictive world of Scottish football

http://www.internetunleashed.co.uk/?p=28641

Pigeons, punches & tattoos - the addictive world of Scottish football - http://www.internetunleashed.co.uk/?p=28641 Goals, gaffes, howlers & handbags - Scottish football ready to return When the news came through from Hampden that a dead squirrel had dropped out of the sky during the League Cup tie between Queen's Park and St Mirren, confusion reigned - yet again - in Scottish football. A dead squirrel? Falling from the heavens? How?The story was, of course, untrue. A spokesperson for Queen's Park revealed it was, on inspection, a pigeon (decapitated) and not a squirrel that had plummeted to its death. The club added sombrely on Twitter that their thoughts "are with his flock at this sad time".A month earlier, Ayr United manager Ian McCall was doing an interview at the end of a pre-season friendly against Forfar at Somerset Park when a seagull crashed to earth beside him. "I'm really not happy about this," said McCall. It wasn't entirely clear what he was referring to - his team's performance or the fact the bereaved seagull's wider family were hovering menacingly above his head at the time.I'm a late convert to Scottish football. Growing up in Limerick, save for the occasional clip of Celtic goals tacked on at the end of a sports bulletin on a Sunday night it was never seen on our screens. You had Manchester United and Liverpool, Leeds and Spurs, West Ham and Arsenal and then you might have had Celtic. Beyond that, Scottish football didn't exist. We were missing out. From about 2005, I started to take notes about the madcap wonder of the game in this country and wrote newspaper columns about the craziness of it all at the end of each year. Some memories of the bonkerdom still stick out. Artur Boruc, then Celtic's goalkeeper, getting a tattoo of a monkey's backside on his tummy with the word 'Rangers' written on it. 'There's a Rangers bum on Artur's tum' went the headline. Then there was the more recent yarn about the Celtic fan getting a '10-in-a-row' tattoo while inebriated on holiday in Magaluf and then waking up the next morning with 'Terry Munro' etched across his chest.There was Craig Brown, then the 70-year-old manager of Motherwell, punching an uppity official from Odense during a European tie at Fir Park. Brown was indignant when asked if the blow had connected. "Oh aye," he said. "I definitely hit him. I used to be quite a useful amateur boxer in my youth."There were tales of blackmail and kidnapping and fraud and mysterious goings-on of all kinds. The Rangers saga could be a movie trilogy. Just in the past year or so we've had Hearts building a new stand and forgetting to order the seats, we've had Ross County accidentally deleting their own website, we've had Inverness Caledonian Thistle somehow tweeting porn on their official account.We've had a vomiting linesman at Kilmarnock v Dundee, we've had a well-oiled Rod Stewart doing the Scottish Cup draw on telly, we've had a section of Celtic fans being told by the club that they're a bit smelly and should wash themselves, we've had Kingsley, the weird-looking Partick Thistle mascot, announcing he's running for office on Glasgow City Council.And now dead birds are dropping out of the sky and endangering players and managers. This is the weirdness that everybody revels in, but there's more to it. Attendances are on the rise. Intrigue is on the up, particularly since the arrival of Steven Gerrard at Rangers, a story that reverberated around European and, perhaps, world football. Gerrard, Brendan Rodgers, Derek McInnes, Neil Lennon, Steve Clarke, Craig Levein - that's a compelling cast of managerial characters at the top end of the Premiership.Scottish football is not monied and it's not glamorous, but in terms of stories and passion it could go toe-to-toe with any league in any country anywhere in the world. Neil Lennon hasn't held back when celebrating this season. 'In that moment, you felt like applauding'It's the passion, the all-encompassing obsession, that's addictive. If you were reared on the game here then it's in you and it's never coming out. If you weren't, but live here for long enough, you find yourself sucked into the vortex. And it's terrific in that vortex. Not everybody gets it, but who cares?It seems like Scottish football fans are caring less and less what outsiders think of their game. A case in point was the recent Adam Rooney business. Rooney, one of the Premiership's most consistent goalscorers in recent seasons, was signed by Salford, a club with deep pockets and famous owners.A few commentators in England - among them, Jim White, the exiled Scot on Sky Sports - wondered what the transfer said about the state of the Scottish game. The inference was that it was a new low that a club of Aberdeen's history lost their best goalscorer to a non-league club down south.Previously, there might have been uproar about it in Scotland. Some might have agreed with the sentiment. Others might have disagreed. The chances are the words would have been taken to heart one way or another and the navel-gazing would have carried on awhile. 'Whither Scottish football and all that...'This time, no. Most people here understood what was going on. Fiscal commonsense came to town a while back. That's something to be proud of. Is this the new 'Broony'? In the Rooney case, McInnes could not guarantee the Irishman a starting place. Rooney was offered regular football elsewhere on a much bigger salary. He went. End of story. The view from Scotland wasn't 'Isn't this embarrassing', it was more 'Isn't it odd that a non-league club can shell out upwards of £4,000 a week on a player...'We have two worlds on one island. There's the world of English football - predominantly Premier League football - and there's Scotland's world. In the world of the Premier League, Everton sign Davy Klaassen for £23.6m and sell him 18 games later for £12m. A world where Southampton sign striker Guido Carrillo for £19m, play him 10 times, get no goals, and loan him to Leganes. A world where Stoke sign defender Kevin Wimmer for £18m in the summer and farm him out to Hannover in January.Instead of asking what the Rooney deal says about Scotland, you could ask what those deals - and many others - say about England, but each to their own. Why do these clubs gamble, and too often waste, tens of millions on players? Because they can. Because their prize money and television money - regardless of success or failure - is other-worldly. West Brom made £94.6m despite finishing bottom of the Premier League last season. The three relegated clubs made a combined £292m. For finishing seventh, Burnley made £120m, which is more than double the amount Aberdeen intend to spend on their new stadium. After Aberdeen drew 1-1 with Burnley in the Europa League first-leg tie at Pittodrie last week, McInnes was asked if this sent a message to England that the quality of football in Scotland is better than they might have assumed.His answer was redolent of a changing attitude. He said he didn't care what people in England thought of it. It was of zero interest. He wasn't being rude, he was just telling it like it was. His team didn't need to prove themselves to anybody apart from their own people. In that moment, you felt like applauding. Scottish football has its own identity, it's own appeal. By turns, it's beautiful and ugly, thrilling and tedious, inspiring and infuriating. It's all yours. And, God bless it, it's back. There was an unexpected participant on the pitch at Hampden... Source link

0 notes

Text

Fighting 'like an animal' may not be what you expect

New Post has been published on https://funnythingshere.xyz/fighting-like-an-animal-may-not-be-what-you-expect/

Fighting 'like an animal' may not be what you expect

Pick an animal.

Choose wisely. In this fantasy, you’ll transform into the creature and duel against one of your own. If you care about survival, go for the muscular, multispiked stag roaring at a rival. Never, ever pick the wingless male fig wasp. Way too dangerous!

This advice sounds exactly wrong. But that’s because many stereotypes of animal conflict get the biology backward. All-out fighting to the death is the rule only for certain specialized creatures. Whether a species is bigger than a breadbox has little to do with deadly ferocity.

Many creatures that routinely kill their own kind would be terrifying — if they were larger than a jelly bean. Certain male fig wasps unable to leave the fruit they hatch in have become textbook examples, notes Mark Briffa. He studies animal combat at Plymouth University in England. Stranded for life in one fig, these males grow “big mouthparts like a pair of scissors,” he says. They use those mouthparts to “decapitate as many other males as they possibly can.” The last he-wasp crawling has no competition to mate with all the females in his own private fruit palace.

In contrast, some of the big mammals that inspire sports-team mascots use their antlers, horns and other outsize male weaponry for posing, feinting and strength testing. Duels to the death are rare among these species.

“In the vast majority of cases, what we think of as fights are solved without any injuries at all,” says Briffa.

Evolution has produced a full rainbow of conflict styles. They range from the routine killers to animals that never touch an adversary. Working out how various species in that spectrum assess when it’s worth their while to go head-to-head has become a challenging research puzzle.

To untangle the rules of engagement, researchers are turning to animals that live large in small bodies and have no sports teams named after them. At least not yet.

Story continues below video.

[embedded content]

Animal weaponry can look pretty scary or even deadly. But animals duel in a variety of ways that totally upend the stereotypes most people carry.

Science News/YouTube

Deadliest matches

It’s hard to imagine nematodes fighting at all. There’s little, if any, weaponry visible on their see-through, micronoodle bodies. And that includes the species called Steinernema longicaudum (STYN-er-NEE-muh Lon-jih-KAW-dum). Yet in Christine Griffin’s lab, a graduate student offered a rare hermaphrodite to a male as a possible mate. (A hermaphrodite is an individual with the traits of both a male and female.) Instead of mating, the actual male went in for the kill.

“We thought, well, poor hermaphrodite. She’s not used to mating. So maybe it’s just some kind of accident,” says Griffin. (Griffin’s lab at Maynooth University in Ireland specializes in nematodes as pest control for insects.) The grad student, Kathryn O’Callaghan, also offered females of another species to the males. The males killed some of those females too. When given a chance, males also readily killed each other. That’s how nematodes, in 2014, joined the list of kill-your-own-kind animals, Griffin says.

Killing another nematode is an accomplishment for a skinny thread of an animal with just two thin, protruding prongs. The male S. longicaudum slays by putting his mating moves to new uses.

When he encounters a female of his own species, the male coils his tail around her. He then moves the prongs — known as spicules — that are used to hold open the entrance to her reproductive tract. To kill, a male just coils his tail around another male (or a female of a different species) and squeezes extra hard. Pressure ruptures internal organs. Sometimes those spicules even punch a hole during this fatal embrace. The grip lasts from a few seconds to several minutes. Of those worms paralyzed by the attack, most are dead the next day.

These are Steinernema longicaudum nematodes. In a fight between the tiny worms, the male attacker (first panel) curls his body around one of his own kind and squeezes, rupturing the enemy’s internal organs (second and third panels). The victor (top, last panel) nudges the loser as if checking for any remaining resistance.

C. Griffin

Other nematodes live in labs around the world without murdering each other. So why does S. longicaudum lean toward extreme violence? Its lifestyle of making a home inside an insect inclines it to kill, Griffin suggests. An insect larva is a prize that one male worm can monopolize. It’s also the only place he can mate.

These nematodes lurk in soil without reproducing or even feeding until they find a promising target, such as the pale fat larva of a black vine weevil. Nematodes wriggle in through any opening — the larva’s mouth, its breathing pores or maybe its anus. If a male kills all male rivals inside his new home, he can start a huge family tree with lots of generations of offspring. Those offspring might total in the hundreds of thousands, Griffin points out.

Territorial female slayers

Dramatic fights rage inside green, flower-filled sacs on this tree (Ficus citrifolia) that will eventually mature into figs. Certain male fig wasps are famous for their lethal brawls. However, research shows females also go at it.

C. Jandér

A defendable bonanza like a weevil larva, or a fig, has become a theme in the evolution of deadly fighting. Biologists have studied violence in certain male fig wasps for decades. However, more recent research has revealed that some females kill each other, too.

A female Pegoscapus (Pay-go-SKAY-pus) wasp is a bit longer than a poppy seed. When she chooses one particular pea-sized sac of flowers — a fig-to-be — she’s deciding her destiny. That sac is most likely her only chance at laying eggs. And it will probably be the fruit she will die in, notes Charlotte Jandér. She’s an evolutionary ecologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Inside a fig, two females grapple jaw-to-jaw beside a wasp that may have died in earlier combat.

C. Jandér

Shortleaf fig trees have “a delicate flowery smell,” Jandér says. The blooms, though, are hidden inside little green-skinned sacs. To reach these inner riches and lay one egg per flower in as many flowers as she can, the wasp must push through a tight tunnel. The squeeze can take roughly half an hour. And it could rip her wings and antennae. Reaching the inner cavity carpeted in whitish flowers, “there is plenty of space for one wasp to move around,” Jandér says. But more than one gets cramped, and conflicts get desperate.

In a wasp species from Panama that Jandér has watched, females “can lock on to each other’s jaws for hours and push back and forth,” she says. In a Brazilian species, 31 females were found decapitated among 84 wasps. Jandér was part of a research team that reported this in 2015. It was the first documented female-to-female killing in fig wasps.

Walk away

Many animal species have ways to back off rather than fight to the death. Briffa studies one example: sea anemones. And yes, anemones fight.

The formal name for beadlet sea anemones is Actinia equine (Ak-TIN-ee-uh E-KWY-nuh). They release their sperm and eggs into open seawater. The animals don’t need to argue over mates. For a prime bit of tide-pool rock, however, tensions may rise.

When not battling, an anemone’s fighting equipment (which can sometimes be colored blue) is pulled in.

Below a beadlet’s pinkish, swaying food-catcher tentacles are what often look like “little blue beads,” Briffa points out. These are fighting tentacles, or acrorhagi (AA-kroh-RAJ-ee). When combat looms, the anemone inflates them. “Imagine someone pulling out their bottom lip to make a funny face,” he says.

It’s no joke for an impertinent neighbor. Anemones are distant relatives of stinging jellies. And their acrorhagi carry harpoon-shooting, toxin-injecting capsules. Combatants rake stinger acrorhagi down each other’s soft flesh. “It almost looks like they’re punching each other,” Briffa says. “When one of the anemones decides it’s had enough and wants to quit the contest, it actually actively walks away.”

“Walk” is used loosely here, notes Sarah Lane. Then she demonstrates by alternately arching her hand and flattening it in a measured trip across the Skype screen. She’s a postdoc in Briffa’s lab. Maybe it moves “like a cartoon caterpillar?” she says, trying to describe the gait. Or perhaps “a concertina?”

To start fights, the researchers place anenomes side by side in the lab. About one time in every three the anemones concertina away or otherwise resolve the tension without any acrorhagi swipes. Backing down this way makes sense considering that a full exchange “looks quite vicious,” Lane says. Strikes leave behind bluish fragments of acrorhagi full of stinging capsules. Those capsules kill tissue on the recipient.

Sea anemones escalate some battles and “walk away” from others. After a fight, an anemone’s stinging tentacles, which are called acrorhagi, show holes after losing tissue to an opponent.

The attacker won’t leave unscathed either. Close-ups show open wounds where acrorhagi tissue was pulled out. An anemone “literally can’t hurt an opponent without ripping parts of itself off,” she explains.

Injuries to an attacker from swiping, biting or other acts of aggression get overlooked in discussing how animals weigh the costs and benefits of dueling. Lane and Briffa argued this in the April 2017 Animal Behaviour. The sea anemones may be an extreme example of self-harm from a strike. Still, they’re not the only one.

Humans can hurt themselves when they attack. Deciding whether to fight can have some unintended impacts, Lane points out. In a bare-handed punch at somebody’s head, little bones in the hand crack — creating so-called boxer’s fractures — before the skull cracks. With the introduction of gloves around 1897, boxer’s fractures basically disappeared from match records, Lane says. Before gloves, however, records show no reported deaths in professional matches. Once gloves lessened the costs of delivering high-impact punches, deaths began appearing in the records.

Worth the fight?

Sea anemones don’t have a brain or central nervous system. However, costs and benefits of fighting somehow still matter. The animals clearly pick their fights. They escalate some blobby sting matches and creep away from others.

Just how anemones choose — or how any animal chooses — when to fight and when to back down turns out to be a rich vein for research. Scientists have proposed versions of two basic approaches. One is called mutual assessment. This “is sussing out when you’re weaker and giving up as soon as you know,” Briffa says. “That’s the smart way.” Yet the evidence Briffa has so far, he says with perhaps a touch of wistfulness, suggests anemones use “the dumb way of giving up.”

This “dumb” option is called self-assessment. Animals resort to this when they can’t compare their opponent’s odds of winning with their own. Maybe they fight in shadowy, murky places. Maybe they don’t have the neural “smarts” for that type of comparison. For whatever reason, they’re stuck with “keep going until you can’t keep going anymore,” he says. Never mind if the fight is hopeless from the beginning.

The odds of fighting “smart” look better for the animals that Patrick Green of Duke University in Durham, N.C., studies. These creatures have a brainlike ganglion (GANG-lee-un). And they come close to fighting with superpowers. He’s working with, of course, mantis shrimp.

The high-powered smashers among these small crustaceans flick out a club to move at “highway speeds,” Green says. What’s more remarkable is that the club reaches those speeds really fast. They accelerate like a bullet shooting out of a .22 caliber pistol.

When the clubs wham a tasty snail, the bounce back creates a low-pressure zone that vaporizes water. “I always feel weird saying this because it seems just goofy.” Still, Green says, “that does release heat equivalent to the surface of the sun.” Fortunatey, it lasts only a fraction of a microsecond.

When smasher mantis shrimp — males or females — fight each other, they batter rivals into oblivion. The reality, though, is arguably stranger. They superpunch each other. But the blows land on an area that can withstand the force. It’s the telson. This bumpy shield covers the rump.

In Caribbean rock mantis shrimp, the battle is often over after just one to five blows. Those blows happen too fast for the human eye to see. In test fights between animals of equal size, the winner is not the animal that lands the most forceful blow. Instead, it’s the one that gets in the most punches. Then, with no visible gore, one dueler just gives up.

Story continues below image.

Power-punching Caribbean rock mantis shrimp can settle disputes without deadly blows. Here, the combatant at right lifts its telson, or rump shield, which takes the hits.

Roy Caldwell

Green and Sheila Patek, also at Duke, propose that this telson sparring permits genuine mutual assessment. That’s the smart way of losing a fight. It’s difficult to figure out what lurks in the neural circuits of an arthropod. However, the researchers presented multiple lines of evidence in the January 31 Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

One strong clue came from matches that Green staged between mantis shrimp of different sizes. He didn’t see a trend of smaller ones pointlessly pounding telsons as the lightweights fought bigger animals. Those bigger animals were going to win anyway. And it seemed as if the smaller ones understood that. This suggests something more than self-assessment is going on, Green and Patek now propose.

Researchers think they have seen mutual assessment in other animals too. These include wrestling male New Zealand giraffe weevils. They’ve also seen it in male jumping spiders that flip up banded legs in “Goal!” position to intimidate rivals. Analyzing assessment gets tricky.

For instance, scientists, dazzled by the sights and sounds that our own sensory world emphasizes, may be underestimating chemical cues. Among crawfish, “part of their fight is squirting urine in one another’s faces,” Briffa says.

Paradoxically peaceful

Rhinoceros beetles have elaborate horns that the males use in duels over potential mates.

Frantisek Bacovsky

Many of the scariest-looking weapons end up causing little bodily harm. Some are specialized for combat that’s more strategic than gory. Other weapons look so scary they hardly ever get used.

Erin McCulloughan is an evolutionary biologist, now working at the University of Western Australia in Perth. The male Asian rhinoceros beetles that she studies host odd horns. The forked horns on their heads stretch nearly two-thirds the beetle’s body length. Surprisingly lightweight, the horns look cumbersome. They resemble “a Styrofoam leg sticking out of your forehead,” she says.

She watched the guys compete furiously with each one night at a university in Taiwan. Despite it being hot and muggy, her shirts had the collars pulled way up. Leather gloves covered her hands. She hardly blended in with the students. So why all this gear? “You shouldn’t wear mosquito repellant when you’re working with insects,” she explains.

But it was worth it. The scene illuminated by her head lamp was “really messy and chaotic,” she recalls. Beetles flying out of the dark fought to dominate cracks in ash tree bark that oozed sap and attracted females. A dominant beetle would grip the bark and use his horn to flick incoming challengers off the branch left and right — until some other guy unseated him. Getting thrown off the limb doesn’t kill losers. Often they buzz right back for another try.

Yet from the vantage point of evolution, a male who doesn’t mate might as well be dead. His genes will never be carried on to the next generation. That meant his winning a female has important impacts for his community impacts. Males with longer horns are better at flicking off other males. Yet longer horns also are more likely to snap, McCullough notes. And a broken horn won’t grow back.

The largest male rhinoceros beetles grow the longest horns, which gives those males an advantage in monopolizing a mate.

I.A. Warren et al/PLOS ONE 2014

The extravagant tool needs to be a pry bar of just the right length, lightness and strength. Fresh, new horns on male beetles just starting their fighting careers have about four times the strength the horns need to resist cracking. (That’s about the safety factor that engineers build into bridges but less than the standard for elevator cables, she notes.)

Horns or antlers on male mammals often can kill. Yet fatal fights may be rare, says Douglas Emlen. He’s a biologist at the University of Montana in Missoula. One of his favorite studies comes from decades-old research on caribou. That study looked at about 1,308 sparring matches between male caribou in Alaska. With all this glaring, snorting and rushing, only six matches escalated into violent, bloody fights.

Evolution usually does not favor extremes in teeth, horns or other such body weaponry. Certain forms of rivalry for mates, however, can foster certain weapons to expand extravagantly in a body-part arms race. There are common patterns to such arms races, Emlen says, including some cheating.

Among conditions that favor an arms race are rivalries playing out in one-on-one duels, he says. Imagine a magnificently endowed dung beetle in a tunnel. He guards a female in the depths behind him. One by one, he must fend off all rivals for her attention. Growing bigger and bigger horns, however, comes with a cost. Eventually, only an animal with the best nutrition, genes and luck can spare the resources to grow a truly commanding horn. And at this point, horn size signals a male that can overpower just about all rivals. Only another supermale will engage him in an all out fight. The rest of the time, his threatening weaponry keeps the peace with barely a bump or a bruise.

Yet this is “a very unstable situation,” Emlen adds. “It creates incentives for males to cheat.” Or maybe the word should be “innovate.” He has found that big-horned male dung beetles defending their tunnels can be outmaneuvered by small rivals. Those smaller beetles dug bypass tunnels around the guard zone. That let them mate with the supposedly defended female.

At the far extreme of animal rivalries are some species that blur the meaning of fights. Some butterflies, such as the speckled wood butterfly, “fight” without physical contact. Males compete for a little sunlit dapple on the forest floor by flying furious circles around each other until one gives up and scrams. No gore, but probably really exhausting.

0 notes

Text

Fighting like an animal doesn't always mean a duel to the death

New Post has been published on http://funnythingshere.xyz/fighting-like-an-animal-doesnt-always-mean-a-duel-to-the-death/

Fighting like an animal doesn't always mean a duel to the death

Pick an animal.

Choose wisely because in this fantasy you’ll transform into the creature and duel against one of your own. If you care about survival, go for the muscular, multispiked stag roaring at a rival. Never, ever pick the wingless male fig wasp. Way too dangerous.

This advice sounds exactly wrong. But that’s because many stereotypes of animal conflict get the real biology backward. All-out fighting to the death is the rule only for certain specialized creatures. Whether a species is bigger than a breadbox has little to do with lethal ferocity.

Many creatures that routinely kill their own kind would be terrifying, if they were larger than a jelly bean. Certain male fig wasps unable to leave the fruit they hatch in have become textbook examples, says Mark Briffa, who studies animal combat. Stranded for life in one fig, these males grow “big mouthparts like a pair of scissors,” he says, and “decapitate as many other males as they possibly can.” The last he-wasp crawling has no competition to mate with all the females in his own private fruit palace.

In contrast, big mammals that inspire sports-team mascots mostly use antlers, horns and other outsize male weaponry for posing, feinting and strength testing. Duels to the death are rare.

“In the vast majority of cases, what we think of as fights are solved without any injuries at all,” says Briffa, of Plymouth University in England.

Evolution has produced a full rainbow of conflict styles, from the routine killers to animals that never touch an adversary. Working out how various species in that spectrum assess when it’s worth their while to go head-to-head has become a challenging research puzzle.“In the vast majority of cases, what we think of as fights are solved without any injuries at all,” says Briffa, of Plymouth University in England.

To untangle the rules of engagement, researchers are turning to animals that live large in small bodies but don’t have sports teams named after them. At least not yet.

[embedded content]

DUKE IT OUT Animal weaponry can look pretty scary, deadly, even. But, animals duel in a variety of ways that totally upend human-contrived stereotypes.

Deadliest matches

It’s hard to imagine nematodes fighting at all. There’s little, if any, weaponry visible on the see-through, micronoodle body of the species called Steinernema longicaudum. Yet in Christine Griffin’s lab at Maynooth University in Ireland, a graduate student offered a rare hermaphrodite to a male as a possible mate. Instead of mating, the male went in for the kill.

“We thought, well, poor hermaphrodite, she’s not used to mating, so maybe it’s just some kind of accident,” says Griffin, whose lab specializes in nematodes as pest control for insects. When the grad student, Kathryn O’Callaghan, offered females of another species, males killed some of those females too. When given a chance, males also readily killed each other. That’s how nematodes, in 2014, joined the list of kill-your-own-kind animals, Griffin says.

The worm turns

In a fight between nematodes, the male Steinernema longicaudum attacker (first panel) curls his body around one of his own kind and squeezes, rupturing the enemy’s internal organs (second and third panels). The victor (top, last panel) nudges the loser as if checking for any remaining resistance.

Killing another nematode is an accomplishment for a skinny thread of an animal with just two thin, protruding prongs. The male S. longicaudum slays by repurposing his mating moves.

When he encounters a female of his own species, the male coils his tail around her and positions the prongs, known as spicules, to hold open the entrance to her reproductive tract. To kill, a male just coils his tail around another male, or a female of a different species, and squeezes extra hard. Pressure ruptures internal organs; sometimes spicules even punch a hole during the fatal embrace. The grip lasts from a few seconds to several minutes. Of those worms paralyzed by the attack, most are dead the next day.

Other nematodes live in labs around the world without murdering each other. So why does S. longicaudum, for one, lean toward extreme violence? Its lifestyle of colonizing the innards of an insect inclines it to kill, Griffin suggests. An insect larva is a prize one male worm can monopolize, not to mention the only place he can have sex.

These nematodes lurk in soil without reproducing or even feeding until they find a promising target, such as the pale fat larva of a black vine weevil. Nematodes wriggle in through any opening: the larva’s mouth, breathing pores, anus. If a male kills all rivals inside his new home, he becomes the nematode Adam for generations of offspring perhaps totaling in the hundreds of thousands, Griffin says.

Fig-based battles

Dramatic fights rage inside the green, flower-filled sacs that will mature into figs (top, Ficus citrifolia). Certain male fig wasps are famous for lethal brawls, but research shows females also go at it. Two females (bottom) grapple jaw-to-jaw beside a wasp that may have died in earlier combat.

Territorial female slayers

A defendable bonanza like a weevil larva, or a fig, has become a theme in the evolution of lethal fighting. Biologists have studied violence in certain male fig wasps for decades, but more recent research has revealed that some females kill each other too.

When a female Pegoscapus wasp, a bit longer than a poppy seed, chooses one particular pea-sized sac of flowers, a fig-to-be, she’s deciding her destiny. That sac is most likely her only chance at laying eggs, and will probably be the fruit she will die in, says evolutionary ecologist Charlotte Jandér of Harvard University.

Shortleaf fig trees (Ficus citrifolia) have “a delicate flowery smell,” Jandér says, but the blooms are hidden inside the little green-skinned sacs. To reach these inner riches and lay one egg per flower in as many flowers as she can, the wasp must push through a tight tunnel. The squeeze can take roughly half an hour and rip her wings and antennae. Reaching the inner cavity carpeted in whitish flowers, “there is plenty of space for one wasp to move around,” Jandér says. But more than one gets cramped, and conflicts get desperate.

In a Panamanian wasp species that Jandér has watched, females “can lock on to each other’s jaws for hours and push back and forth,” she says. In a Brazilian species, 31 females were found decapitated among 84 wasps, reported Jandér, Rodrigo A.S. Pereira of the University of São Paulo and colleagues in 2015. That was the first documented female-to-female killing in fig wasps.

Walk away

From bellowing red deer stags to confrontational male stalk-eyed flies, many animal species have ways to back off rather than fight to the death. Searching for dynamics of less-than-deadly discord, Briffa studies sea anemones. And yes, anemones fight.

Beadlet sea anemones (Actinia equina) release sperm and eggs into open seawater, so the animals don’t need to argue over mates. For a prime bit of tide pool rock, however, tensions rise.

Below a beadlet’s pinkish, swaying food-catcher tentacles are what often look like “little blue beads,” Briffa says. These are fighting tentacles, or acrorhagi. When combat looms, the anemone inflates them. “Imagine someone pulling out their bottom lip to make a funny face,” he says.

It’s no joke for an impertinent neighbor. Anemones, distant relatives of stinging jellies, carry harpoon-shooting, toxin-injecting capsules in the acrorhagi. Combatants rake stinger acrorhagi down each other’s soft flesh. “It almost looks like they’re punching each other,” Briffa says. “When one of the anemones decides it’s had enough and wants to quit the contest, it actually actively walks away.”

“Walk” is used loosely here, says Sarah Lane, a postdoc in Briffa’s lab, as she alternately arches her hand and flattens it in a measured trip across the Skype screen. “Like a cartoon caterpillar?” she says, trying to describe the gait. “A concertina?”

When placed side by side in the lab for fighting tests, anemones concertina away or otherwise resolve the tension without any acrorhagi swipes about a third of the time. De-escalating makes sense considering that a full exchange “looks quite vicious,” Lane says. Strikes leave behind bluish fragments of acrorhagi full of stinging capsules, which kill tissue on the recipient. The attacker isn’t unscathed either; close-ups show open wounds where acrorhagi tissue was pulled out. An anemone “literally can’t hurt an opponent without ripping parts of itself off,” she says.

Injuries to an attacker from swiping, biting or other acts of aggression get overlooked in theorizing over how animals weigh the costs and benefits of dueling, Lane and Briffa argued in the April 2017 Animal Behaviour. The sea anemones may be an extreme example of self-harm from a strike, but they’re not the only one.

Humans can hurt themselves when they attack, and decision making around fighting has had some unintended consequences, Lane points out. In a bare-handed punch at somebody’s head, little bones in the hand crack — called boxer’s fractures — before the skull does. With the introduction of gloves around 1897, boxer’s fractures basically disappeared from match records, Lane says. Before gloves, however, records show no reported deaths in professional matches. Once gloves lessened the costs of delivering high-impact punches, deaths began appearing in the records.

Worth the fight?

Sea anemones don’t have a brain or centralized nervous system, yet costs and benefits of fighting somehow still matter. The animals clearly pick their fights, escalating some blobby sting matches and creeping away from others.

Just how anemones choose, or how any animal chooses when to fight and when to back down, turns out to be a rich vein for research. Theorists have proposed versions of two basic approaches. One, called mutual assessment, “is sussing out when you’re weaker and giving up as soon as you know — that’s the smart way,” Briffa says. Yet the evidence Briffa has so far, he says with perhaps a touch of wistfulness, suggests anemones use “the dumb way of giving up.”

Animals resort to this “dumb” option, called self-assessment, when they can’t compare their opponent’s odds of winning with their own. Maybe they fight in shadowy, murky places. Maybe they don’t have the neural capacity for that kind of comparison. For whatever reason, they’re stuck with “keep going until you can’t keep going anymore,” he says. Never mind if the fight is hopeless from the beginning.

The odds of fighting “smart” look better for the animals that Patrick Green of Duke University studies. Those creatures have a brainlike ganglion and come close to fighting with superpowers. He’s working with, of course, mantis shrimp.

The high-powered smashers among these small crustaceans flick out a club that can accelerate as fast as a bullet shooting out of a .22 caliber pistol. When the clubs wham a tasty snail, the bounce back creates a low-pressure zone that vaporizes water. “I always feel weird saying this because it seems just goofy, but that does release heat equivalent to the surface of the sun,” Green says. But only for a fraction of a microsecond.

When smasher mantis shrimp — male or female — fight each other, they don’t supernova rivals into oblivion. The reality, arguably stranger, is that they superpunch each other. But the blows land on an area that can withstand the force: the telson, a bumpy shield covering the rump (SN: 7/11/15, p. 13).