#12daysofcarnivale

Photo

“Alright, lads...we’ve got a bit of a benjo planned for first sunrise.”

@12daysofcarnivale gift for @henrylevesconte!

#The Terror#the terror amc#TheTerrorEdit#Henry Le Vesconte#Declan Hannigan#gif#flashing gif#12daysofcarnivale

733 notes

·

View notes

Text

an unexpected gift | crozier/fitzjames | 2144

The house in Banbridge is neither large nor small, but even from a distance it has the appearance somehow of a box stuffed beyond closing.

"There are thirteen of us, you recall," Francis says, peering out the carriage window at the facade through the sloping rain.

"Hardly an impossible number," James says. Sits up: straightens his waistcoat. Coach to sloop to coach he has coaxed Francis along, carefully not thinking of what they might make of him, the residents of this house of whom he cannot conceive except as an assortment of Francises of various ages, sexes and professions. Best foot forward, he thinks to himself; he has seen combat and he will survive this.

"Well," says Francis. "Consider, please, when the moment comes, that we have come at your request."

=

After they are swept into the hall which smells of cut greenery and burnt pastry, after Francis is embraced by at least two women in tears and one who calls him "an absolute weasel," after James has managed to have his case sent somewhere, although he is not sure he will see it again—after all this, Francis looks at him flatly and says, "twelve days," in tone of longing which James is now perhaps more capable of understanding.

=

Francis, it transpires, is one of the youngest of the infamous thirteen. There are generations to follow: the hallways are full of lawyers and clergymen and girls and spinsters, officers in the Hussars and little children in blue silk sashes, all apparently talking at once. There are so many of them that even James's considerable powers of keeping his connections straight are tested and then abandoned. He would be more concerned by this but that he is variously introduced by people other than Francis as a rear-admiral, a lieutenant, a captain in the Marines, and once, somewhat improbably, an adjutant to the Swedish ambassador ("That's Thomas," Francis says, curling his lip, "being funny."). Certainly at least one of the children has been telling the others that he is a pirate.

Principally, when he is introduced correctly, it is as Francis's friend, and this seems to be a credential which stands him a great deal of confidence.

"Francis," booms an elderly man with the thunder of heaven in his voice, "are you still a godforsaken atheist?"—"Francis is an irredeemable radical," he is told, by a cheerful, pretty woman who may be Francis's sister-in-law or his sister but is called Mary Ann either way. "Frank doesn't like mint sauce," a dragoon informs him at dinner. ("I do," says Francis, with indignation. "You go off something for a fortnight when you're ten and you're never forgiven it.")

=

It is more like a ship than a house, James thinks. Houses, in James's experience, are quieter. Here it is up and down stairs, looking for playing cards, a bottle of brandy, looking for this gift or that—gossip from the kitchen, what someone has heard from her lady's maid—one of the stablehands heartbroken, his girl run off with a soldier—a spat over chess among the sisters. George and Graham still not speaking. James is brought into these intrigues without scrutiny or examination; his presence seems taken for granted.

At one point when he has at last found an empty room to stand in for a moment—a dusty study which is nevertheless stuffed to every rafter with books of all possible descriptions, German novels, Latin poetry, mathematical treatises, staunch loyalist sermons, political pamphlets (heavily annotated in disapproving red ink, the word "nonsense" repeating throughout and a familiar "FALSE"), a wild-eyed woman—a niece? Elizabeth?—comes through from some connecting passage carrying a child covered in jam and a dressed capon on a platter. She thrusts the platter into James's open hands—he thanks heaven for his gunner's speed—and says "James, please," on her way past. He has no idea what he is meant to do with it until she turns at the door, the child's hands now in her hair, and says "James, George's son, I mean, not James, Edward's brother—in the back parlour, I think," and vanishes down the passage.

"You're a part of it now," Francis says, gleefully, leaning on the bannister halfway up the stairs, when James walks past with the capon. "And you asked if you should wear full dress."

=

He aims himself upstairs to change his coat before dinner, and someone's daughters offer to show him the way: he isn't sure whether to be offended or encouraged that no one seems concerned by this unchaperoned encounter. They are entirely uninterested in him, as it comes to pass: whether he is too old now to turn their heads, or whether being a particular friend of their dour Uncle Francis has simply marked him as inexpressibly dull, he cannot say, but he feels no resentment. Still they are charming and full of chatter, and once he has his coat he waits for them to finish:

"Have you any family, Captain," says Eleanor, as she pins ribbons to her hair.

"A brother," James says. "I suppose."

"You suppose," says Emily, from the settee, where she flips through fashion plates. "How exciting."

"Well, hard luck," says Eleanor. "You've got us now, and we're not exciting in the slightest."

=

The house is neither fine nor shabby. Every inch of it is worn and every inch polished; there are cracks in the plaster and new carpets in the dining room. William, James thinks, would have a fit at the decor, but James rather likes it.

Over the fire in the front parlour hangs a small portrait of a straightforward-looking woman, her hair pulled back from her soft face. "My mother, Jane," Francis says, leaning on the sideboard, the silver tray with its decanters at his elbow, untouched.

James steps up to the fire, eyes turned to the painting.

"She looks like you," he says, after a moment: it isn't clear at first but he sees it after a moment, in the shape of the eyes and the mouth.

"Don't speak ill of the dead, now," Francis says, amusement wrapped like wire around the ragged edge of his voice.

James turns—steps to him—takes his hand and presses it. It is too intimate for a gesture of friendship, here in this dark overfilled room, but then there is no one to see it.

=

"James," Francis says, "is not to be trusted with a pudding."

This over a dinner from which such an item has vanished. He begins the story somewhat apologetically, awaiting some sound of disapproval from Francis: but Francis only looks at him, raises an eyebrow, nods go on.

In five minutes he has them rapt, leaning elbows on napkins and chins on fists, whispering no and he wouldn't and occasionally saying "ha!" By the time he has reached the climax—himself and Charlewood in the cupboard, Mrs Helfer half-convinced poor Mr Rassam is mad—there are tears on cheeks, and Mary Ann is has placed her forehead on the table and is shaking in silent hilarity. Even Francis, leaning back in his chair, is smiling at him, more at ease than should be possible.

"But why were you on the Euphrates at all, Captain," asks Graham, after all is said, and now at last Francis says "oh, here we are," but he is still smiling too—

"Well, a man has to keep some secrets," James says, and smiles back. Realizes, after he does, that he has not kept his mouth shut to hide his false teeth: finds he doesn't mind. If anyone has noticed, it doesn't show.

=

"You have returned him to us," says Charlotte the younger, who very much likes novels, nearly tearful. "For that we owe you more than we can possibly repay."

"Don't mind Lottie," says Francis-who-is-fifteen. "She takes after the weeping side of the family."

=

Francis had insisted that they take rooms in an inn, but in the run of time an elderly aunt arrives from Bath and the girls are desperate to be away from her ("I loathe whist," Emily says, with feeling) so there is a general switching-round, and they end up in an awkward space under the eaves dominated utterly by its only bed.

Charlotte the elder—Francis's sister Charlotte, who seems to feel responsible for such things—wrings her hands. "Oh, Captain," she says, "I am sorry, only there's nowhere else and every room in town is full—you aren't put out, are you? Francis will not be too much trouble, I'm sure—"

"Like a dog," Francis says, amused. No one seems to have considered whether he might object to the arrangement.

"They've both slept in fourteen inches of hammock, and worse," says Sarah, who is nailing something festive—a hook for a holly bough?—to the wall. "I'm sure they will endure this."

"Oh," Charlotte says, to herself, turning, "oh—"

They do indeed endure.

=

On Christmas eve the whole house decants into a variety of conveyances to go up to a party—apparently an immemorial tradition—at the old hall which James suspects is the Earl of Moira's former seat, not that he can find anyone to ask in the flurry of greatcoats and pelisses.

"Will you go," Francis says to James, in the parlour where he sits at piquet with his sister Sarah, who is smoking a pipe. "There will be dancing," he says, to James, considering his cards. "I'm sure the girls would be delighted to have you."

"Oh," says Sarah to Francis, "Does he dance? Wasted on you, then."

Perhaps James ought to startle at the implication, but he finds he simply hasn't the energy.

"Correct," Francis says, just as James says "Not at all," and they look at each other and smile.

"Against character," says James, "I rather feel that dancing is beyond me, tonight."

He takes a seat by the table, flipping out his tails, and eyes Francis's hand. Lifts an eyebrow.

"Ha," says Sarah.

=

Upstairs in the warm room above the empty house Francis turns the bolt of the door and draws the curtain and says "there, now," and turns to James with the edge of smile.

"Less glamorous than you'd hoped, I imagine," he says, as he sits on the end of the bed to pull his boots off. The room smells of cloves and oranges, though not one pomander is to be seen: below, the faint scent of hot brick and dust. On the bed Francis looking up at him, assessing, eyes slightly narrowed: works his jaw as if he means to say something.

Three steps to stand between his knees and bend to kiss him on the mouth and chase the taste of sugar, smoke and almond. To sling a leg over his thigh, slide into his lap—a little stiffly, perhaps, though James does not choose to dwell on it—and sit like that, over him, like a girl in a tavern, and smile against his mouth. Francis's little exhalation against his lip.

"Is this all right," James says, thinking: in the family home, under his mother's roof, rest her no doubt pious soul.

Francis huffs, tips himself backwards, and hauls James down on top.

=

In the study packed with books he finds against all odds a copy of A Poetical History of England: means only to glance at it but finds himself caught in the rhythm, in Louisa's odd sense of humour. Is still standing there forty minutes later when Francis's silent sister Rachel slips through on her way somewhere. Pauses: looks at him curiously.

"Do you know it," she says, in her almost inaudible voice.

"My mother," he says. Her eyebrows quirk—her face so much like Francis's—

"Your mother—enjoys it?" she asks, stepping cautiously closer. He clears his throat.

"Louisa Coningham," he says, "was my—stepmother." A lie: he hadn't meant to lie here. "Well," he says, "nearly."

If this perplexes her she doesn't show it. "How wonderful," she says, still quiet as a mouse, "to have such people in one's family."

=

Sarah is watching him carefully, and James has the distinct feeling that he is being assessed. "May I tell you something, Captain Fitzjames," she says. When he inclines his head she continues: "When Francis was a boy he kissed a brewer's son behind the stables," she says. "I'm not sure it ever occurred to him that he oughtn't. They sent him to sea a month later."

She says this very plainly, as if it is of no concern to her. Perhaps, he thinks, it isn't.

"He has been back once or twice," Sarah says. "Since father passed." A twist of her mouth. She stands: she is a tall woman, grey-haired; her shoulders very straight. "Thank you," she says, looking James in the eye, "For bringing him home."

=

#12daysofcarnivale#except LATE#(i felt odd about reading too much genealogy for this one#so no guarantees all of francis's siblings were still around in 185X)#FOR THE PURPOSES OF THIS NARRATIVE EVERYONE IS ALIVE. thank you#crozier/fitzjames

188 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Anatomy Studies of Harry D. S. Goodsir

Edinburgh “was a townscape raised in the teeth of cold winds from the east; a city of winding cobbled streets and haughty pillars; a city of dark nights and candlelight, and intellect.” – Alexander McCall Smith

(for Day 9 of the 12 Days of Carnivale: “by candlelight”)

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 days of carnivale - day 1 “a special disguise”

Blanky playing with his daughters!

#the terror#12daysofcarnivale#thomas blanky#the terror amc#blanky#ages are wonky because a smaller kid was cuter ops#i TRIED to look for accurate clothing references but then that didnt happen#atrocious quality i recomend clicking

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

12 Days of Carnivale - Day 1, “A special disguise”

So this is early because I’m not good at timing and I wanted to get it out incase I forget tomorrow due to busy busy busy. FitzCro ft THE DRESS. But soft and sad.

He feels pleasantly drunk by the time Francis finds him. There’s a bottle of brandy stood empty by his glass, a splash or five of it on the tabletop, and his toes are more than a little cold where they wriggle just over the edge of the chair opposite.

“What in blazes are you doing, James?” The man asks, voice tight and shaky.

James rolls his head on his neck and relishes the lazy way his eyes catch up with the movement. The sensation makes him giggle. He knows he must seem unhinged, but it all seems so… distant now, as it happens. Sat as he is, red skirts bunched about his bare knees and his hair tousled far from elegantly about his ears and jaw, he must look several times more ridiculous than he feels.

“I’m in disguise, Francis. Can’t you tell?” He replies with a mock-stern glare and a point of one gloved finger. It is a long and white silk glove, no doubt a lady’s glove in design, and James finds himself fascinated by the feel of it on his skin. But Francis is looking at him as though he has lost his mind. “If I’m in this,” he gestures to the dress with his free hand, “then no one can call me Captain or ask me to take charge. I can- I can sit here with my drink and rest a while.”

Something soft crosses over Francis’ expression and James doesn’t know if he likes it. The wrinkles around his eyes smooth out a little, the ones around his mouth deepening as a frown forms on his lips and James thinks, not for the first time, about kissing him. It’s a ridiculous thought, but tonight is for all sorts of ridiculousness - they will be leaving the ships behind in less than forty hours, and James intends to leave some sort of memory in the place.

Francis pulls out a chair and sits by James’ side. His hand reaches out, taking the half-full glass from James’ fingers. Their hands brush and James sighs.

“I am losing a part of myself here, Francis,” he says in laboured breath. “I fear I’ll never- I’ll never quite recover from what has happened. Even if we survive this long walk out, if we keep our minds as well as our lives, I doubt there will be a part of me untouched by this hell.”

He uses the ridiculous thoughts in his mind to bolster the dutch courage in his stomach and reaches out, taking Francis’ hand in his own and staring at the sight of aged skin against pristine glove. Francis squeezes his hand, silent, and it makes James’ heart ache.

After a pause thicker than the ice below them, Francis speaks. “Your disguise is working,” he said under his breath, “I can’t recognise you. How will I take courage in the things ahead without the greatest of men by my side?” He reaches up and tucks a lock of hair behind James’ ear. “I’m not as strong as I seem, I need someone to bolster me. Will you help?”

James sniffles and presses his cheek to Francis’ palm. He turns his face, his lips meeting skin and feeling the thud of Francis’ pulse beneath. With a deep breath he nods, slowly taking the gloves from his fingers and using the digits to comb his hair into some semblance of order.

“There,” Francis whispers, softer than any silk. “There’s my James.”

The words slip between James’ ribs, not unlike a musket shot, and burrow into his heart. He feels defenseless as a grin steals over his lips and his body lists towards his friend. When they kiss it is soft and slow, warm, it fills James’ blood with something far more potent than brandy, and he doesn’t even try to stifle the contented sigh.

“C’mon then, you daft bugger,” Francis lifts him gently to his feet and walks him to his berth. “Get in bed. I’ll stay awhile and make sure you’re all set for the hangover you’re sure to have in the morning.”

James kisses him again at that, drawing him close and shivering as his feet danced on the cold floorboards. “I’m not that drunk. Just- just a little hazy, is all.”

They laugh together, both recognising the lie. Francis gently unlaces the gown, draws it down over James’ chest and hips, helping him step out from the mass of skirts. He stands in his underwear and feels heat blossom in his cheeks, something hotter in his belly as Francis looks him up and down. They can’t, not now, but James almost asks Francis to stay and disguise him with bites and to cover him with a lover’s touch.

Instead, he lets Francis put a nightshirt on him and put him to bed as chaste as any friend. Disappointment fades as Francis kisses the back of his hand and bids him goodnight. Sleep soon follows, dark and deep and undisturbed.

#12daysofcarnivale#12 days of carnivale#the terror amc#the terror#fitzier#fitzcro#james fitzjames#francis crozier

78 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In a far corner of the world, Thomas Blanky celebrates his new years day in quiet peace and a good smoke. With a best friend at his side too.

12 Days of Carnival: New Beginnings! (part 2)

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

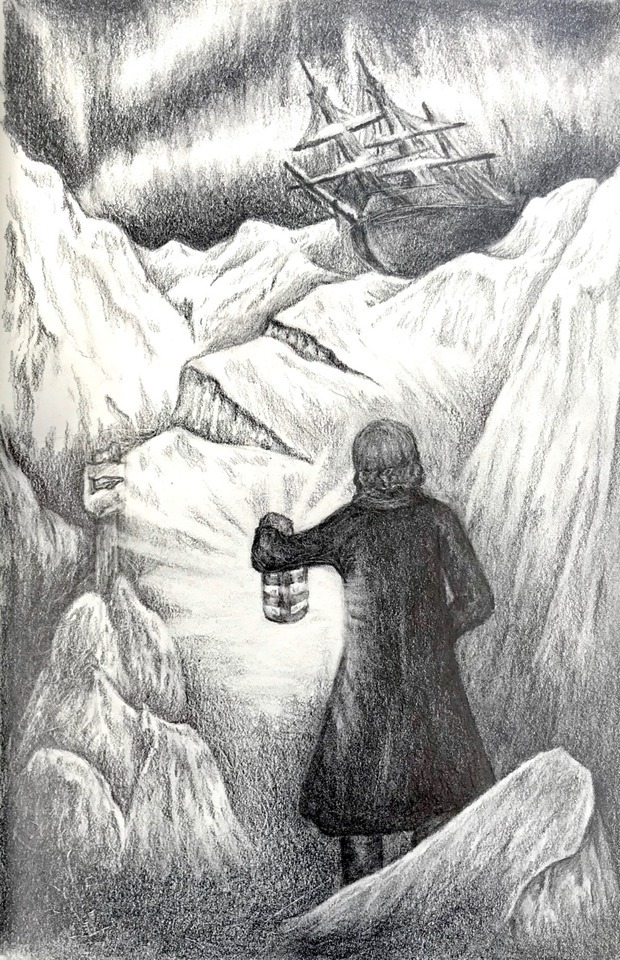

And through the drifts the snowy clifts

Did send a dismal sheen:

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken—

The ice was all between.

Sketch for Twelve Days Of Carnivale: By Candlelight

A sailor makes his way between the ships. And of course I had to feature the ominous pointing-hand signpost.

#the terror#arctic exploration#12daysofcarnivale#franklin expedition#and a Coleridge quote of course#IndifferentArt

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

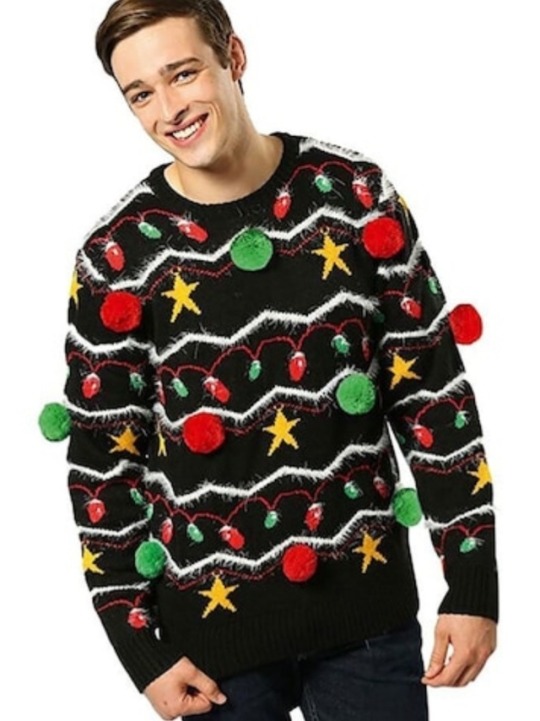

The Terror as Christmas Jumpers (Part 1)

For day one of 12 days of carnivale: "a special disguise", I have crafted hand-crafted you this shitpost. Shout out to @graduatedpillowmonster for finding half of these goddamn jumpers and reminding me of my sons' names!

Crozier:

Fitzjames:

Blanky:

Little:

Jopson:

Irving:

Bridgens:

Peglar:

Sir John Fuckwit Franklin:

Lady Franklin:

#the terror#amc the terror#12daysofcarnivale#12 days of carnivale#shitpost#long post#a special disguise

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Title: The Love of A Biscuit Thief

Prompt 3: Naughty or Nice

Character(s): John Irving, Jacko, Henry Le Vesconte

Rating: General

John Irving loved all of God’s creatures, even the ones that no one else seemed to care for. They were all innocent, free of sin in his eyes. He grew more and more excited as he neared the barren decks of Erebus. Fitzjames had settled on an Officers meeting and Irving had prided himself on volunteering for the excursion, mostly to cure the rising melancholy from being idle for too long but also to enjoy the company for the departed Sir John’s tittering little monkey named Jacko.

She had always been sweet to him, finding a comfort in his presence which he himself felt honored by as most of the Erebites seemed to tolerate her behavior less and less with each visit. During meetings she would often huddle with him and feast on a few treats left out to distract her from any of the officer’s food. On some occasions like a child she would try to feed John to which he politely would decline. To him, she was a good and gentle creature. To others… well that may not be the case.

Irving heard her before he saw her while coming below deck and dusting off the ice from his jacket and boots. She shrieked while he heard a curse coming from the great room. The monkey came bounding in, biscuit in mouth and heading towards John for sanctuary from a very cross Le Vesconte. She jumped, grabbing onto his uniform and he swiftly brought her up into his arms, holding her as he would a baby.

“God damn the beast! I told James to keep her caged for the evening!” The Lieutenant huffed, glaring at the little beast who cradled the fresh biscuit like it was worthy treasure. If Le Vesconte wasn’t so cross he might have laughed at the exchange. Of course, a man who enjoyed snacks as much as the Frenchmen would be angry over this. John thought to tell Edward and George about it later.

“I’ll make sure she behaves, Henry. Salvage what you can of course. One biscuit should sate her.”

“Do not take offense to this John but you do not know the little devil as we do. She has a bottomless appetite and a disposition for destruction.” Le Vesconte quipped before returning back to the room to a spilled bowl of treats. It was hardly what John would call a mess but he understood that tensions were growing daily.

Jacko chittered to him, refusing to look at Le Vesconte like a guilty child while clinging to her friend and savior. Someone had taken the time to dress the monkey up in warm clothing, a little shirt and pants fit more for a tike but with room for her curly tail. Irving had heard that the dark and grumbly ice master-in-training, Mister Collins had knitted her a few pairs of clothing as the adventure grew colder and colder. Her little paw extended to him, offering him parts of her prize. She was a good creature at heart and that’s what John loved the most about her.

“No thank you Miss Jacko.”

#im all about sweet animals babey#12daysofcarnivale#the terror#the terror amc#john irving#jacko#henry le vesconte#james fitzjames#fluff#tres fluffy boiss mentioned#i just love irving and jacko being good friends#irving deserves a friend#i write sins and tragedies

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

day 10: in hot water

@12daysofcarnivale

rating: g

characters: harry goodsir, henry collins, jane goodsir

pairing: goodsir/collins

word count: 3096

read on ao3

buy me a coffee!

harry had always been the type to bring home strays. the goodsir household was large and loud and even as a child, he’d scamper home with crayfish or crabs in buckets, or holding a big orange barn cat, or a baby bird. once he had even come home, a triumphant grin on his face, clutching a live grouse in his hands.

(his mother had nearly had a conniption over it being loose in the house, and then it was caught and butchered and harry had cried for days)

he supposed in a way he felt responsible for collins. he cared for him, of course, admired his gentleness even as the man himself shook to pieces, enjoyed the way his voice curled sweetly around harry’s name, had marveled in the way that collins had been able to point out every star and constellation and name each and every one of them.

(”they’re different this far north,” collins had said, looking almost bashful about it, but something inside of him had seemed to settle and harry had smiled for it)

collins had been caught with a glancing blow from that monster out there on the ice- tuunbaq, blanky had once translated for them, and lady silence had looked small and mutinous- the impact of its great large paw cracking his ribs, claws rending flesh. the wounds were large and ugly, but survivable, and it had been lucky that collins hadn’t gone into shock or caught an infection; harry suspected that the latter at least was due to the coca wine that collins had pilfered, a mixed blessing.

harry had done his best to stitch him up and had felt guilty that out of all the men he could save, he was glad that collins was one of them.

and after, after, when they were swathed in wool blankets that weren’t threadbare and had bellies full of hot food that wasn’t ridden with lead, when the bandages that were wrapped ‘round collins’s middle were fresh and clean instead of tattered, the man will look so small and miserable that harry near aches with sympathy.

“do you have any family?” harry had asked him in his kindest voice, but collins’s shoulders had drawn up about his ears with a wince. “i could write them, if you wish, tell them that you’re safe. i’ll send the letter out with my own.”

“don’t.” he doesn’t know if collins had meant for the word to come out a whisper but it had, a rasping, sad sort of breath. “i don’t... i’m not well, doctor. in the head. don’t want them to see me like this, billy and harry and the girls. it’s not- i’d rather be dead, than come back to them like this.”

harry draws in a sharp breath at that; he had known that collins had been hurting, horribly so, but he hadn’t thought it had gone so deep to make collins value his life so little. he lays his hand over the other man’s, says, “do you have anywhere to go, once we return?”

collins shakes his head no, just the slightest movement.

“then you’ll come with me,” he decides. “nearly all my brothers have left for homes of their own, so there will be room enough at rosebank.”

that was how harry ended up walking down one of anstruther’s streets, collins near enough at his side that their arms brushed. they both looked rather ragged and disreputable, he was sure, but the streets around him felt familiar and close, inundated with childhood memories. he noticed different things, now, whether by separation or experience, and it fits strange on him like an old coat.

“that’s the baker’s shop,” harry says, pointing out the building as they pass; has done this time and time again, bringing collins’s attention to some landmark and giving a childhood anecdote. “my younger brother robert- bob, really- was sweet on one of the daughters. he’d spend all his money on pastries he didn’t like just to talk to her, and he’d blush and stutter his way through every time.”

later he gestures at the beach as they climb the hill, says, “i used to spend days out there in the sand. i would bring things back to the house- crabs, mostly- and be scolded for it, but it never stopped me. that’s what i did before, you know; i studied crabs.”

the before what didn’t need to be specified.

collins smiles a little, small, and something lightens in his face as he pauses to look out over the water. “my sister maggie, margaret,” he says, “she loved birds. she’d point out every one we saw, but i couldn’t ever remember all the names.”

harry smiles, too, and just barely touches their fingers together before they continue up the hill.

rosebank was a decently sized house, tiled roof and white-washed walls, and a fixture in harry’s life for as long as he could remember it. this was what he thought of when he had buoyed himself dreaming of home: this house, his parents, his siblings. the big garden that his mother and jane had loved; the work lab that he and john had constructed in the attic; the foul words that robert had carved into tree trunks when they were children.

“that’s it there?” collins asks, and harry nods. he is filled with equal parts trepidation and anxiety, a wanting to be there already while also wary of what he might find. “you’ve got a big house, doctor goodsir.”

he’s long given up any sense of humility regarding his titles; he is a doctor, an anatomist by education if not a surgeon by practice. a doctor goodsir in a family of doctor goodsirs. “i’ve a big family, too.”

the cobble road that lead to the house was the same as he remembered it, the bushes and flowers his mother had loved tenderly, the faded paint on the gate to the carriage house. a part of him had almost expected it to all be gone, to be changed with the way he had changed, these past long years.

“are you alright?” collins’s voice was soft, as if often seemed this days, but now out of compassion more than anything. harry runs a hand down his face, through the beard he’d grown during those months on the long march. he was sure he looked a fright, unshaven and framed by riotous dark curls, but he’d scarcely had time to look at himself in a mirror let alone make himself presentable.

they’d just have to take him as he was, then.

the flat stones that marked the way to the door were the same, grass a bit more overgrown between the cracks without a constant and steady stream of traffic to keep it trampled. the door was the same, the white wash on the walls, the creeping ivy that his mother had tried so hard for years to get rid of. he raises his hand to knock on the door, then decides to try the knob.

it was his home, after all, no matter how long he’d been gone. he shouldn’t have to knock to enter his own home.

the door was unlocked and so he pushes it open and the house is quiet, too quiet even for only two people. harry frowns and he hears collins shift closer, just the barest rustle of fabric, and he reaches back for the other man’s hand, reassured slightly when warm fingers tangle with his own. perhaps it was his experiences that had made him so paranoid and distrustful of silence, his neck prickling with awareness; he’d spent so long surrounded by a crush (and then a lessening, lessening number) of men that quiet had become foreign to him.

harry closes the door behind him because he was raised, well, here, and not in a barn, meaning that he had some sense of decency. collins is peering about, his face pinched in that perpetual expression of vague despair that has seemingly come to be his norm.

“you’re sure you lived here, doctor?” collins’s voice is pitched low, and harry would have thought it was a joke had he not known the man as well as he did. he opens his mouth to respond, perhaps a bit put out, but a creak on the stairs makes him look up, the nearly spiral staircase that always squeaked no matter the step.

harry feels something lodge in his throat. “jane?”

“harry?”

they stay at rosebank some few weeks, a season or maybe more. harry is glad for it; anstruther is a sleepy, quiet town, contained and familiar and free of painful reminders. collins, too, seems more settled, something lighter in his eyes, the set of his shoulders. he has been thinking of things to write to his family, to tell them that he is not well but that he is getting better, and that he hopes to see them all soon; harry helps him, sometimes, when the words get caught somewhere between his brain and his pen.

but there was grief here, too, empty spaces where people should have been. he would walk into the sitting room and expect to see his father sitting in front of the fireplace, or at his desk in the study; if he listened close enough, he swore that he could hear archie’s laughter. jane was the only one here, now, and he felt almost bad for her, all alone in the house.

the others visit by turn, john and robert and joseph. harry is glad for it, pathetically so. the first time harry is alone with john he clings to him and sobs like a child, while his brother combs his fingers through his hair, only a little bit awkward. robert, on his own, ribs harry gleefully about it all, but there’s relief in his voice when he says that he had sailed, twice, to find him and came home wanting.

(it is joseph that harry worries for, joseph who comes home and looks thin and sad and ill but so very glad that harry has returned, who holds his face in shaking hands as if he couldn’t believe that this was all real and pulls him into a tight, crushing embrace. harry reminds himself to ask john his thoughts in his next letter.)

he is getting better. they are getting better.

jane seemed taken with collins, which harry was grateful for, but even more than that he was relieved to see that collins rather liked her, as well. she gave him tasks, harry knew, to keep him busy: running errands or washing dishes or chopping wood or pulling up whatever crop she had decided was good enough to harvest. and then they would all sit down together for dinner and it would be cozy, and domestic, and everything that harry had been almost certain he would never see again.

so harry enjoys the little things he had previously put aside or never had time for. he goes back to studying crabs; he collects seashells. some shaggy tortoiseshell with a cropped tail follows collins home from the grocer one morning, and instead of chasing her off they decide to keep her; he names her apollonia (“polly, for short.”) and feeds her scraps off the table, to jane’s eternal vexation.

they go to the beach, sometimes, he and collins. they take off their shoes and socks and roll up their trousers to wade around in the tide pools, laughing and shouting as the cold waves lap over their ankles and sand seeps between their toes. collins says to him, “we used to do this when we lived in hartlepool, george and i.”

“george?”

“my brother,” collins says, and there’s something sad in his voice. “my twin, really.”

harry makes a surprised noise at that, glances over curiously. “i didn’t know you were a twin.”

the barest shrug of shoulders answers him. “i’m not, anymore.”

he backtracks, then, says, “you don’t sound as if you were from hartlepool.”

“never stayed in one place for more than a few years.” collins plucks a stone out of the sand, deep black and smooth, edges rounded; he tries to skip it but it falls flat into the water with a plop. “my father was navy, and we followed his postings. sussex is where me and george were born. hal and billy in hartlepool; maggie, some place in ireland; tamsin, decima, and lizzy were all popped out in liverpool, but by that time i was already sailing.”

“my family have all been doctors,” harry offers. he plants his hands on his hips and stretches his back, cracks his neck. “my father, my grandfather. john, bob, archie, and myself all studied medicine. we were all born here, too, along with jane and baby agnes, except for joseph. he was born in lower largo, but that’s only a few hours’ walk from here, so i’m not sure it counts.”

it’s the most harry’s ever heard collins talk about his family; occasionally there would be some throw away comment, something one of his siblings had said, or that his sister like this kind of chocolate or his brother broke an arm while climbing a tree. little, inconsequential things, but he’d never had names to go with them. he decided that having a brood of siblings rather suited a man like Collins.

“you’ve a good family, doctor goodsir,” collins tells him, and harry smiles. “you all seem very close.”

“we are. were.” it’s tinged with grief; archie’s loss still hurt, sometimes, like a healing wound. “and please, call me harry. i’ve told you this before, mister collins.”

“you have,” collins cedes, “but you’ve never called me henry, either.”

it is winter the first time harry kisses collins, a bit over a year since they had first stumbled up the hill to rosebank, ragged and tired and battered. and it’s very much that way, harry kissing collins, because harry is the one that fair falls forward while collins’s hands hover, surprised and unsure, and harry is the one that breaks it, too.

there is snow on the ground outside, falling in fat, crystalline flakes, and harry finds that he hates going out into it, but not nearly as much as collins, who takes up a near permanent position in the kitchen, wrapped up in a tartan by the stove as he tries to learn how to knit. the cold was in them, now, deep in their bones and dredging up old nightmares.

they stay indoors. harry sends john his papers to be published, collins tries to knit, and a boy from down the lane chops their wood.

the kiss itself is neither coordinated nor particularly good. harry doesn’t know why he dies it, really; perhaps some latent impulse. he was terribly fond of collins, though, and at this point the man knew him better than anyone else; not his past, perhaps, but his thoughts.

so, harry kisses him.

collins is watching him wide-eyed when he rocks away, fingers clutched in a half-woven glove, his mouth slightly parted. he looked utterly gob smacked and harry swallows down the hysterical laugh that crawls up his throat.

“i’m sorry, henry,” he babbles, “i don’t know what- that is, i didn’t. i’m not. i’m sorry-“

“harry,” collins says, and though his voice is small, harry stops talking immediately. it’s a rare moment when collins uses his name.

“…yes?”

collins’s hand is shaking slightly as he reaches out to brush his fingertips across harry’s cheek, light as a feather, and harry’s eyes flutter shut. his palms are rough, callouses that had cracked in the cold catching on harry’s beard, but the gesture is tender nonetheless. harry covers collins’s hand with his own.

“did you mean it?” collins asks, seriously.

“of course,” harry says.

collins smiles at that, something small and shy and unsure, but it’s a start.

“you’re as bad as john,” jane scolds harry, “and not even half as subtle.”

she has him cornered after dinner, having requested his help with cleaning up. collins had given them both a quizzical look- often he was the one cleaning up, always volunteering- but jane shoos him off and he goes, polly cradled in his arms.

“pardon?” he says. he tells himself he’s not intimidated- that he’s seen worse, done worse- but jane had always had something of their mother in her, and her ability to loom over him despite her height was one of them.

“i don’t care what you do to henry in your spare time,” she says hotly, and she has a finger pressed to his chest, a scowl upon her face. there is the just tiniest beginnings of bags beneath her eyes, and harry swallows. “or what he does to you. but you could at least be quiet about it, else your wailing is like to wake the neighbors and send me to an early grave with exhaustion.”

harry remembers, suddenly, that their rooms share a wall.

“it’s not like that, jane,” he protests, a hot flush crawling up his neck, even though it plainly was. “it’s-“

“i don’t care!”

his mouth snaps shut, cowed into quiet for a moment, and then frowns. “what does john have to do with anything?”

the look that jane gives him is pure disbelief paired with a noise of disgust, and she turns on her heel and strides from the room, leaving harry to clean up dinner alone.

collins sends a letter to his family in late spring of ’53, nearly two full years since they had escaped the arctic.

he was happier than he had been before, harry knew, smiled more and had nightmares less. he was still quiet, still shy and sometimes drifting, but he was leaps and bounds better than the miserable, haunted creature that had first followed harry to anstruther. there were things that had come back with them and things that they had left behind, harry knew, and they would never be the same as they were before it all, before all the death and fear and horror.

(he thought, sometimes, of lady silence, whether she had survived it all and what she was doing if she had, and his heart will swell and collapse inwards under the weight of it all and harry knows that this, too, will never leave him.)

collins writes only one letter, to his mother, and it takes him nearly two weeks to do so. harry walks with him to post it, and they walk close enough side by side that their fingers brush on the way home.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

a long winter's night | james/francis/sophia | 4600

Fitzjames looks less like a portrait than she remembers.

Halfway down the stairs she must stop, she finds, to take him in. In the dark of her hall, in the glow of her lamps, in profile: full brass, stiff collar and cuffs. Whenever she thinks of him it is as something from the last century, a sketch of the young Keppel, a halfdrawn figure behind Howe or Duncan: white breeches and silk stockings, honourably receiving a blade from some kneeling admiral.

Here instead he is, dripping on her hall rug, and he looks like a man: just a man, in a salt-stained coat, with a lined face and something to his stance that suggests old injury. Terribly handsome, yes. Terribly tired. Holds his hat under his arm, though John has taken his greatcoat: his eyes on his own braid in the hall glass. As she watches he lifts a hand to his hair and pushes it from his face: turns the curl in his fingers.

At the rustle of her skirts he turns his head. Looks, she thinks, unhappy.

“Mrs Crozier,” he says, inclining his head. All that stiff exhausted grace, not at all like Francis's, somehow. “I had sought your husband.” It sounds like an admission: a disappointment.

She is still halfway down the stairs.

“Forgive me,” Fitzjames says. “How uncivil I am: I have only just come up from Portsmouth. You look very well.” This as if it weighs on him, and his eyes trace the line of her skirts. The spell snaps: she takes a step down, and another.

“You must be exhausted, Captain,” she says, as she reaches him. “Please, come into the parlour—have a glass of something—“

He straightens into formality. “I really must—“

“Francis will be in shortly,” she says. “Won’t you wait? Gin, isn’t it?”

He swallows it like a hook and follows.

-

She had wondered if it was Fitzjames.

Francis had declined to tell her, of course, and she had not pressed: such secrets cost. It was not his to say. But she had felt it between them almost from the first.

On their wedding night, on their marriage bed, when they were both of them wrung like cloth and dripping sweat and sated, she had asked him who he had loved, and he had told her. Yes, there had been women—of course there had. Yes, men too. He had not blushed to tell her so and she loves him more for it.

And now?, she’d said.

You, he’d answered, and she’d kissed him long and hard and slipped his hand into her shift to cup her breast. Felt him exhale against her mouth.

And, she’d said. Others?

Yes. No. Not anymore.

Who.

And he’d turned his head: just half a turn. Not even a refusal: just an absence of an answer.

Ah, she’d thought.

There are certain expectations a person has, as a sailor’s wife, whether married to a stoker or an admiral. This one, at least, suits her. She has not been chaste and would not ask it of him: in this she thinks they understand one another.

(Once, brooding, he asks: “Did you ever have Ross,” something unexpectedly tight in his voice: when she tells him no he looks like a weight has been lifted from him, and ashamed by it, too. Perhaps it ought to tweak her, but somehow it doesn’t.

"And you?" she asks, and he laughs—blusters—no, absurd—but she does not think she was wrong to ask.

She dreams that night of being between them: wakes damp and too hot—presses her hand against herself through her nightgown. Takes her pleasure in the dark with Francis asleep beside her, snoring slightly, and curls against him when she's done.)

—

In her blue parlour Fitzjames stands like a figure of himself before the fire, his wrist on the mantel, his glass in his hand. (He’ll take brandy in company, Francis had told her, when first they'd asked Fitzjames to dinner: gin if alone. What a thing to know of a man, Sophia had thought.)

“Are you in Brighton,” she asks, when the quiet has filled the room entirely. She has a sense of it as a great velvet cushion pressing down on them, exhausting every space, restraining hands and tongues. Regards him: his still-brown hair, its glossy curl flattened by the rain. His coat well cut, his back still straight. A shockingly beautiful man: how lucky Francis is, she thinks.

“I am,” he says, and can’t seem to continue. Francis had always told her he was a talker but here words seem beyond him: some unknown country. She wonders, suddenly, if something terrible has happened.

“And how was—Madras?”

No response: only the swirl of his glass in his hand and the fire reflected in it.

“Hot,” he says eventually.

Oh but this is tedious.

“Captain Fitzjames,” she says, “is something troubling you?”

He looks at her for a moment and then a smile, bright with gold, illuminates his face: she can feel the vast lantern of his charm lit in her direction: “My god,” he says, “I am dull, aren’t I? Come, let me tell you of the East Indies Station,” sitting elegantly beside her on the chaise, and it is all of it false: she knows this: and irresistible anyway.

=

(How did you come to choose me, she asks, idly, with her hand on Francis's chest.

I love you, says Francis. Turns his head against her shoulder: turns his clear blue eyes to hers.

You love him, too, Sophia says.

Ah, says Francis. A pause: his hand in her loose hair, following a curl. I gave you my word first, he says, eventually.

And I refused it, Sophia doesn't say.

Does he hate you for it, she asks instead: sometimes she curses her own bluntness, and sometimes relishes it.

I don't know, Francis says. I don't know.)

=

“Captain Crozier, ma'am,” Hannah says, around the door.

And Francis comes in half distracted, his coat already off—talking, as always, about dockyard politics—masters' buttons, inferior gilding—and stops, three steps into the room. Sways, as if he's hit some submerged invisible thing.

“James,” he says. Such a series of thoughts across his face: she cannot track all of them, but some, at least, are familiar. Affection. Hurt. Hope.

“Francis,” says Fitzjames, putting down his glass on the sidetable. He rises, correcting his waistcoat—straightens himself to his full graceful height—

Something is going to happen, she thinks.

They move towards one another like failing clockwork: the inevitability of the action set against the diminishing energy necessary to complete it. Like ships, she thinks, trying to read obscure signals. Waiting for the sound of guns.

“I hadn't meant to come," James says, low, something regretful in his voice.

“You know you are always welcome," says Francis, and she would call the tone dismissal if she didn't know it for hurt.

A foot from one another now, and Fitzjames's hand comes up. Hangs in the empty space between him. Opens, closes. His glance, beyond all reason, comes to her.

She looks at him without rising. “Shall I go,” she says. Means it, entirely. (Idly: wonders if they will lie together, soon—if such things are—repairable. Just the picture of it. A little flare of heat somewhere deep in her.)

“Perhaps—a moment—” Fitzjames says.

“Stay,” says Francis.

James looks at him.

"She knows all, James," Francis says, with that slight tip to his chin that says defiance.

Betrayal in a flash across Fitzjames's face. He nods, once, tightly. For a moment Sophia thinks he will fly.

"I wasn't told," Sophia says. "I came to it myself." She swallows. "I don't mind," she says, and finds it true. Fitzjames makes a choked sound that might be a laugh.

On the mantel the carriage clock ticking. The flicker of the firelight on the panelled walls.

She rises from her place on the chaise.

"I think perhaps I ought to go," she says, gently, to Francis.

The look he gives her: loss, confusion. She takes his hand: holds it a moment. "Send for me when you've finished," she says. "I would like to know how things fall."

As she passes Fitzjames she extends a hand to him, too—he takes it without question, although he looks uncertain.

"Be kind," she says, and then she goes from the room.

—

("What do you think he meant by it?" she asks, leaning at the carriage window, as the column passes view. The little figure almost invisible above, lost in the low London rain. Francis says nothing: a grey mood on him, today, and no interest. "'Kiss me, Hardy'?"

That, at least, lifts his eyes to hers. Amusement or bitterness around his mouth. "Kismet," he says, something wry in it. "Sir John will have told you, I'm sure, that it was 'Kismet'."

"Oh?" She says. "Do you think so?" She settles back in her seat.

He looks blankly at her. Then the edge of a smile: he has realized they are playing.

"He meant nothing at all, save to ask a little comfort," he says. "The man was dying. A friend was near. A solace."

"And you'd have asked Thomas Blanky to kiss you, would you?"

He laughs at that.

"No, but I shall tell him that you asked."

"I wonder, though," she says, eyes on the window.

"Aye," says Francis. "You and the fleet."

"And Lady Hamilton such an interesting woman," Sophia says, idly. "With such interesting friends."

Silence, now, from Francis.

"Do you think the three of them..." She lets it slide, fade.

"Well," she says, arranging her skirts. Letting her eyes catch Francis's, now. "I shall have to think on it further.")

—

There is no shouting, though she had thought perhaps there might be. She isn't certain whether it bodes well or ill.

She sits at a card table and puts a button on a cuff. Across the hall she can hear their paced footsteps, their strained voices—once, an oath, Fitzjames she thinks, saying oh god in such desperation—

To think, that her Francis can be as cruel as she.

—

When the door across the hall comes off its latch and Francis steps quietly out it must be eight o'clock: a still and soundless winter night. Her sewing in her lap. She has got good at them, these naval blues and golds. John helps her, sometimes, with the detail work: his steward's fingers faster than hers will ever be.

"Sophy," Francis says, from a distance away. She looks up at him: he doesn't look as though his heart has broken. (That is a look she knows, on him.)

"How shall we go on," he says, not despairing, merely—inquiring.

"Quite easily, I should think," she says. "Will Captain Fitzjames stay the night?"

Francis swallows.

"Come back into the parlour," he says. "Please."

Fitzjames is sitting in an armchair drawn up close to the fire, his long legs crossed and his hair dishevelled. He has lost his coat somewhere, and his waistcoat is open at the top: his collar disarranged. Head in hand, lost in thought.

When he notices her he makes to stand and she waves: "Never rise," she says, and then because she is herself cannot resist: "Surely we are close enough now, with only one man between us." Watches a high flush appealingly spread across his cheekbones.

After a moment he settles back in the chair. Looks back into the fire.

There is a second chair already pulled up too close to the first, at an awkward angle—a kissing angle, she thinks, and nearly smiles. Something so sweet in both of them: innocent, in a way, for all the hells they have walked through.

Francis is hauling the chaise across, too, into the circle of the firelight. None of the lamps lit in here: she supposes they haven't given Hannah the chance.

She takes a seat in the awkward chair and pushes it back so that she can see both of them.

"Well, gentlemen," she says, aware somehow that she is presiding. "What have you decided?"

"Nothing," says Fitzjames, ambivalently, without looking from the fire. "Francis." He swallows. "Francis is under the impression that you would tolerate—" he leaves off. Doesn't seem to know what he means to say. "I wouldn't force you from him," then, staidly. "Nor him from you. Not to—" Silence again. For a talker, Sophia thinks again, he is strangely ineloquent. She has an impulse to comfort him.

"I would almost certainly tolerate," Sophia says. "I am generally a tolerant woman."

"As I said," Francis says, from his seat on the chaise. Sophia glances at him. His waistcoat is a bit too tight: it suits him, somehow.

"I might," Sophia says, "even take pleasure."

"Sophia," Francis says, sounding pleased—interested. She loves him very much: loves speaking to him, playing games like this. Always has, long before she had any intention of marrying him: which has nearly killed them both.

Fitzjames is watching them look at each other. Breathes out, half a sigh.

Enough, she thinks, enough.

"I think," she says, in the leading tone of a schoolmistress, "that we might make some sort of—arrangement."

She looks at Fitzjames: smiles a little. Is aware of him adjusting, minutely, under her gaze: shoulders back, jaw tilted just so. Vain, she thinks: a satisfying trait in bed. To be picked apart with the teeth.

"Yes," he says. His eyes trace some invisible line strung between the two of them. "It needn't be anything—sordid," he says, stiffly. "Only this is—unendurable." This last to Francis. What, she wonders.

Francis, to his credit, laughs.

"Well, what is sordid, James," he says. And then, softer: "You have never been sordid in your life."

"The question now, Captain Fitzjames," Sophia says, before they can wander into stiff endearments, "is the precise shape of it. Tell me, have you any interest at all in me, or will only Francis do?" Francis, scoffing quietly: and out of reach of her hand.

Fitzjames is staring at her, his head tilted a little. Flicks his glance to Francis. Something she cannot see passes between them, and Fitzjames's face softens minutely.

"I think," says Fitzjames, "you had better call me James."

"James, then," she says. "James, will you come to bed with me?"

An intake of breath from Francis: she wants to look at him, just to see his face, but it cannot be. She holds Fitzjames's gaze instead.

"Yes," he says, after a moment. And then, swallowing, at last with something of the charm she recalls: "Yes, I would like that."

"Good," says Sophia. "Francis, I hardly need ask—"

"Yes," says Francis, unequivocally.

"Shall we all go upstairs, then," Sophia says.

They look at her, then, both of them together. As though somehow it is her decision, for all the rank in the room. A giddiness to it: she is torn between telling them they are both fools and taking it in stride. Jane, she thinks, would not hesitate.

"Well," Sophia says. "Someone had best tell Mary and Hannah to take the evening. John, I think, can probably stay."

—

It is not a smooth ascent nor elegant. They stop, stumble, fall back: Francis holds the door for her and then for James and she goes on ahead but James waits for him to latch it, so that she is left standing on the bottom step looking at them together, their awkward edges nearly touching. She waits for them to come up and they do, keeping pace; she thinks again of ships—won't voice the thought, would surely make some error, but it makes her smile, anyway. Herself the faltering would-be prize: waiting only for the range to haul her fighting colours up.

Francis kisses her, in passing, his hand at her elbow, his thumb rubbing at the fabric of her sleeve: then goes on, a few steps up. Fitzjames watching, silent, from below. Something open in his face, now, and searching. He sways closer: she leans: a glancing kiss, on the side of the mouth. Tentative: more kind than passionate.

Above, on the stairs, she hears Francis curse, choked somewhere in his throat. Against her mouth James smiles, and she feels something arc between them: the spark of tying Francis's tongue. She kisses James again: deeper, this time. Makes a little sound in it, a little kitten-mew.

James brings a hand to her waist as she pulls away. She places hers on his shoulder: then turns it, the backs of her fingers against the edge of his jaw. His head turns easily when she presses, his mouth opening: interesting, she thinks. His eyes glassy in the dim light. He is one perhaps who would like to be taken in hand: perhaps he does not know it yet.

She has lost track of Francis, she realizes, though of course this is all for his benefit. When she glances up she finds he has come down to stand a bare step above them, back up against the bannister, hands resting on it at either side. His breathing shallow.

"Again," he says, in a tone something like need.

James steps up to her, now, and oh, he's tall: solid, even in his shirt sleeves: his heavy hand still at her waist. A new role, she thinks, and melts into it, against the wall. James kisses her steadily, this time, and firmly: like something from a novel. Pleasant, she thinks, to be had so. A while now, since she had any man like this, all brisk and bold, affectation though it may be. Her eyes when they open drift to Francis, the high colour in his cheeks, their poses mirrored. James fitting so neatly into the space between them.

She puts her hands to his breast: runs her fingertips down the underside of his lapels. Pushes a little, with her knuckles.

"You," she says. Swallows. "The two of you."

James's breath hitches, just barely.

It is an odd place to see it first, in the middle of her own front stairs, with the lamps shining low off everything. The way James leans up, halting: the breath Francis draws before his eyes shut. Then the angle of it, familiar: the easy way they fit together, as lovers do.

—

In her chamber, at the foot of her bed, certain things become clear.

First, this: however they have been together, they have not managed to undress: not fully, not with the lamps lit. She has the pleasure then of watching, the awkward beauty of it, the anxieties of revelation. Fingers on buttons, quick then slowing; shirts pulled hesitantly over heads: James with his bitter scars and his lean shoulders, tilting his head just so into shadow—Francis holding his breath until James kisses him fiercely and he forgets.

On the end of her bed stripped to her shift she watches: her leg folded against her chest, her arm round her knee. Her hand against herself, unforgiving. She could love them both, she thinks, the way she loves Francis: easily. Indeed.

It is James who turns to her first: who breaks the kiss and crawls onto the bed at her side. His trousers still on, but open: the half-hard line of his prick visible. Her fingers twitch.

"Sophia," he says, "May I—", and she nearly laughs at him, his misplaced decorum, but she says "Yes" instead, without hearing the end of the question.

His hands come up to her face and she waits, curious: presses her mouth to the heel of his hand, just barely: and then he reaches to pull the pins from her hair.

"Shall I help," she says, after a minute of this, the gentle twist of his fingers through her careful curls: not one snag, not one tangle: a practiced hand. Who has he has done this for before, she wonders.

"No," he says, and when the weight of her hair falls against her neck she dips her head. His hand, sliding down her neck to the space between her breasts. Lower, to cup one: his thumb brushing across the peak of it.

She is aware, vaguely, of Francis settling behind her on the bed: his hand on the round curve of her hip.

"It has been some time," James says, quite plainly, with the weight of her breast in his hand, "since I have been close to a woman."

"Christ," Francis says, under his breath.

"How shall we—" says James.

—

How shall we: an excellent question. Slowly. In the warm halflight, with little inquisitive touches: with Francis showing them the way of it. Placing James's hand at the back of her thigh, just below the crease. Placing hers on James's shoulders, to work the tightness there and make his head tip back, mouth open. Francis's hand on James's prick, gentler than he likes it himself. They find their own ways, too: James lapping the hollow of her throat with his tongue; her fingers in his mouth; his fingers inside her.

("Are you," he asks, at one point—swallows—looks awkward—looks to Francis—wondering, of course, whether there will be a child.

"Not yet," she says. Struck by the sudden ache of knowing she will not have him inside her she wants it desperately: tugs his hand into her lap.)

He is better with his tongue than Francis, perhaps unsurprisingly.

Her legs spread, his fingers tanned and rough against the plush of her thigh: his tongue at the crease of her leg and then against her, in stutters like a code, shallow then deep, off-rhythm—off-perfect, in that way that keeps her twisting for more—and Francis lying on his side, watching, his thumb at the bone of her ankle, saying "oh."

And when she has had enough of him she pushes at his shoulder and he goes, easily, sliding back from her and off the bed and upright: she rolls her head to look at him and is surprised for an instant that he is still just a man, slighter than she would have thought, and softer at the hips, with his hair tucked back behind his ear. She glances at Francis, thinking to watch him watch James—a new and exquisite pleasure—but he is watching her instead. Only when she slides her eyes back to James—pouring himself a glass of water, now, from the carafe on her dressing table, his back straight and scarred—does Francis turn his head that way.

"James," he says, voice rough, and James turns—

—

The two of them, intensely gentle with each other. Francis's light touch at the wound in James's side: questioning, she thinks. The ragged sound Francis makes deep in his throat when James kisses him: when James slides a hand up his thigh and cups him, less than gently.

Francis for all his defences and deflections open, now, at James's touch.

James between his thighs sliding into him so devastatingly slowly. Francis with his lip between his teeth and that expression which she can only read as acute pain, though when James lowers himself to ask with mouth against throat "all right?", all raw, Francis responds with a wordless sound which can only be pleasure, pleasure above and beyond all things.

Their hands, caught together on the bed, fingers twisting.

The drip of sweat on the end of James's nose.

—

And Francis, finally, sliding home into her, on his back between her legs. The burn in her spread thighs as she lifts and lowers herself, undone when he pulls her down flush chest to chest to fuck up into her, hard and fast as she adores.

For all that she loves performance this is not one: has never been one, between them. They simply find the smoothest routes to pleasure, like water coursing downhill. Francis, rolling her under him without pulling out: hitching her hips up off the bed: the heat of his skin against hers. The tension in his shoulders and his arms as he supports himself: the concentration on his face. His eyes, shut. The kiss he presses to her brow. The weight of him, when he presses her down. Release like a spiral, descending.

And James, sitting up against the headboard, prick soft and spent against his thigh. Just watching. His dark eyes catch hers for an instant, and he smiles.

—

After, with the lamps out. With her hand in Francis's. He has pulled a shirt on as he always does: less invulnerable, in the afterglow. James curved around them, a loose bracket, asleep. His even breath and his warm hand over her waist, resting in the space between her and Francis.

"I like him," she says, to Francis. He swallows: his eyes already shut.

"Good," he says, drifting. "Good."

"Will he stay," she asks, hoping, but Francis is asleep.

—

And in the morning the light through the curtains and onto the bed, and Francis still warm beside her, despite the sense of someone moving through the room.

"A mistake," James is saying. She comes awake quicker, then.

Francis, beside her, quiet and tense. Sitting up now to watch this display. "James," he says, after a moment. "Must we, again—"

"Christ, again," James says, half to himself, stuffing his shirt into his trousers and buttoning at speed. "I can't—I won't—" he is looking for his tie, now, staccato—and Sophia looks at Francis, to see what he is thinking, but he does not look at her. What is written on his face is something like resignation.

"I have no interest," James is saying, to whom unclear, but so bitterly, "in being a paramour—in trespassing—"

"James," Francis says, and then nothing.

"Please," says Sophia, and James starts. Perhaps hasn't realized she is awake. "Let us be clear about what we are asking of one another." She slips from the bed almost despite herself: meets him standing, on her own two feet. Bare in front of him: a weapon in its own right.

"Stay here," she says. "With us. As long as you like. Live here, James. Tell people you live here."

"Yes," says Francis, without pause.

James standing there with his crumpled tie in his hand looking—mortared.

"Have your things sent up," Sophia says. "Today, if you will."

Francis on his feet, now, too. His hand touching her shoulderblade, just—light. Through the windows the light pooling on the floor: motes of dust caught in it, turning. Winter light, but turning.

"Please do," Sophia says. "Stay."

(She had asked Francis, in those first weeks after the wedding: And will Captain Fitzjames be living with us? Such things are done, though she was not innocent even then of how this case might differ. Francis's mouth unmoving: his eyes aside: No, he'd said, I think not.)

James looking at both of them. Half-dressed, his hair flat, his collar half down. Those little lines around his mouth: discomfort, distrust. So much of him, she thinks, invested in being respectable. So much faith in the sanctity of whatever he is not.

"You were the one," she says, "who said it needn't be sordid. So stay."

He brings a hand to his brow: pushes that lock of hair back from it.

"All right," he says, and it sounds like defeat: but longing, also.

"Good," Sophia says. "I'll let Mary know about breakfast."

(As she goes to dress she glances back: sees Francis extend his hand and draw James into his arms. Sees them tip together. Like sculpture, she thinks, the way they fit. Implausibly balanced. As if cut from one single piece of stone.)

>>a probably unnecessary note: despite it generally being pinned on the victorians, the earliest mentions i can find of the "kismet" argument are from the 1920s. on the other hand these are all refutations, so presumably the idea was floating around before that? Great Battles of the British Navy (1872) omits the line entirely and gives Nelson and Hardy a nice manly deathbed handshake instead, so presumably the concern about how “kiss me” might be understood existed by then. also this show/book shamelessly used "go for broke" in the 1840s so i, too, refuse to be ashamed.

#12daysofcarnivale#i was going to save this for the Last Day but what the hell:#happy new year's eve friends#nervous about tagging this#in this new puritanical dawn#but like: you probably shouldn't read it at a family gathering.

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(for Day 12 of the 12 Days of Carnivale and @wildcard47, who asked for a CrozFitz rom-com AU, filled with all the tropes!)

The Hallmark Channel Presents: “The Christmas Inn”

James Fitzjames was surely being sent into exile.

As a prize-winning foreign affairs correspondent, he had covered stories everywhere from Syria to Bangladesh to North Korea, sometimes risking life and limb in the process. But apparently he had irritated someone on the editorial floor enough that they decided to send him to the most hellish location imaginable – upstate Vermont – to write, of all things, a feature story on the historic anniversary of the nation’s oldest continuously-operating inn.

And the date of that historic anniversary? Christmas Eve.

It shouldn’t really surprise him that with this particular story, nothing goes right at first: a mix-up with his reservation and a massive snowstorm that strands him there for longer than he had planned, a gruff inn owner who seems entirely unimpressed with his easy charm and tales of international adventures.

But as James learns more and more about the Franklin Inn and about its good-hearted and handsome proprietor, he’ll realize that there might be a story there after all, one about the true meaning of Christmas, and how a single place – and a single person – can bring together an entire community.

And in the end, there might even be a little Christmas magic just for James, waiting for him under the mistletoe.

#the terror amc#the terror#12daysofcarnivale#fitzier#james fitzjames#francis crozier#au#wildcard47#i hope you like it!#moodboard

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

ficlet: james & francis, “state of grace”

gen, rated g, 335 words.

(written for @12daysofcarnivale!)

Once, before the walking out had taken from them any spiritual performances not carried out in the mind’s quietude, Francis had glimpsed Fitzjames praying.

In his kneeling position, height cut down by half, the man had looked so oddly small. Like a child. Francis had neither meant nor wanted to see this sight—had entered Erebus’s Great Cabin with his customary brief rap upon the lintel, and been confused to find it empty but for a voice issuing from the captain’s berth—once Sir John’s, now Fitzjames’s. Damnable curiosity had drawn him within earshot.

“Christ, hear me,” spoke Fitzjames, low and serious. “God in heaven, have mercy on us, and show us the path to our salvation; whether it be earthly or spiritual.” A breath. “Though, Christ, I confess I do hope for earthly salvation most of all—” and then the prayer had broken off on a ragged noise.

With lightest steps, Francis retreated, his fingers twisting wildly at his sides. He felt flayed and observed, without seeming reason; for it was not himself that had been overheard in such vulnerability.

Francis collected himself outside of the Great Cabin. This time, he rapped long and loud, calling, “Captain Fitzjames?”

There was the sound of a scraping door. Footsteps followed, and then Fitzjames stood before him, a neat half-turn on his heel and incline of his head as greeting. “Francis. To what do I owe the honor?”

There was no outward sign that Fitzjames had been moments before, in a quiet and uncertain voice, beseeching the Lord for deliverance. The cant of his eyebrow was as cool as usual, and no hair on his head was out of place; nor any speck of dust visible at the knee of his trousers. The state of his person gave no indication of the apparently troubled state of his soul.

Francis cleared his throat and moved into the room so that their conversation might continue in privacy—he felt that much and more he now owed him, though it was a debt he fervently wished to forget.

#the terror#the terror amc#12daysofcarnivale#originals#fics#today's yuletide warmup#hashtag multitasking

32 notes

·

View notes

Link

At an Admiralty gathering, James and Francis make the acquaintance of some illustrious - or is that notorious? - elders. Written for the Terror 12 Days of Carnivale event, Day 4 (December 16th): 'An Unexpected Gift.' Sorry it's late!

#12daysofcarnivale#the terror#francis crozier#james fitzjames#fitzier#my writing#my fic#ahhhh i wasn't sure if i would get this done there have been CHALLENGES#happy carnivale people

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

In Hot Water

Two nerds (according to sources; James Fitzjames and Harry Goodsir) found a hot spring in the arctic.

12 Days of Carnivale

Day 10 (Dec 22): “in hot water”

29 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 1: a special disguise

Terror and Erebus are playable ships in Azur Lane and that was an opportunity I couldn’t let pass

Sorry for the delay

26 notes

·

View notes