#County Roscommon

Text

Story and photographs by Ronan O’Connell

September 26, 2023

In the middle of a field in a lesser known part of Ireland is a large mound where sheep wander and graze freely.

Had they been in that same location centuries ago, these animals might have been stiff with terror, held aloft by chanting, costumed celebrants while being sacrificed to demonic spirits that were said to inhabit nearby Oweynagat cave.

This monumental mound lay at the heart of Rathcroghan, the hub of the ancient Irish kingdom of Connaught.

The former Iron Age center is now largely buried beneath the farmland of County Roscommon.

In 2021, Ireland applied for UNESCO World Heritage status for Rathcroghan (Rath-craw-hin). It remains on the organization's tentative list.

Rooted in lore

Spread across more than two square miles of rich agricultural land, Rathcroghan encompasses 240 archaeological sites, dating back 5,500 years.

They include burial mounds, ring forts (settlement sites), standing stones, linear earthworks, an Iron Age ritual sanctuary — and Oweynagat, the so-called gate to hell.

More than 2,000 years ago, when Ireland’s communities seem to have worshipped nature and the land itself, it was here at Rathcroghan that the Irish New Year festival of Samhain (SOW-in) was born, says archaeologist and Rathcroghan expert Daniel Curley.

In the 1800s, the Samhain tradition was brought by Irish immigrants to the United States, where it morphed into the sugar overload that is American Halloween.

Dorothy Ann Bray, a retired associate professor at McGill University and an expert in Irish folklore, explains that pre-Christian Irish divided each year into summer and winter.

Within that framework were four festivities.

Imbolc, on February 1, was a festival that coincided with lambing season.

Bealtaine, on May 1, marked the end of winter and involved customs like washing one’s face in dew, plucking the first blooming flowers, and dancing around a decorated tree.

August 1 heralded Lughnasadh, a harvest festival dedicated to the god Lugh and presided over by Irish kings.

Then on October 31 came Samhain, when one pastoral year ended and another began.

Rathcroghan was not a town, as Connaught had no proper urban centers and consisted of scattered rural properties.

Instead, it was a royal settlement and a key venue for these festivals.

During Samhain, in particular, Rathcroghan was a hive of activity focused on its elevated temple, which was surrounded by burial grounds for the Connachta elite.

Those same privileged people may have lived at Rathcroghan. The remaining lower-class Connachta communities resided in dispersed farms and descended on the site only for festivals.

At those lively events they traded, feasted, exchanged gifts, played games, arranged marriages, and announced declarations of war or peace.

Festivalgoers also may have made ritual offerings, possibly directed to the spirits of Ireland’s otherworld.

That murky, subterranean dimension, also known as Tír na nÓg (Teer-na-nohg), was inhabited by Ireland’s immortals, as well as a myriad of beasts, demons, and monsters.

During Samhain, some of these creatures escaped via Oweynagat cave (pronounced “Oen-na-gat” and meaning “cave of the cats”).

“Samhain was when the invisible wall between the living world and the otherworld disappeared,” says Mike McCarthy, a Rathcroghan tour guide and researcher who has co-authored several publications on the site.

“A whole host of fearsome otherworldly beasts emerged to ravage the surrounding landscape and make it ready for winter.”

Thankful for the agricultural efforts of these spirits but wary of falling victim to their fury, the people protected themselves from physical harm by lighting ritual fires on hilltops and in fields.

They disguised themselves as fellow ghouls, McCarthy says, so as not to be dragged into the otherworld via the cave.

Despite these engaging legends — and the extensive archaeological site in which they dwell — one easily could drive past Rathcroghan and spot nothing but paddocks.

Inhabited for more than 10,000 years, Ireland is so dense with historical remains that many are either largely or entirely unnoticed.

Some are hidden beneath the ground, having been abandoned centuries ago and then slowly consumed by nature.

That includes Rathcroghan, which some experts say may be Europe’s largest unexcavated royal complex.

Not only has it never been dug up, but it also predates Ireland’s written history.

That means scientists must piece together its tale using non-invasive technology and artifacts found in its vicinity.

While Irish people for centuries knew this site was home to Rathcroghan, it wasn’t until the 1990s that a team of Irish researchers used remote sensing technology to reveal its archaeological secrets beneath the ground.

“The beauty of the approach to date at Rathcroghan is that so much has been uncovered without the destruction that comes with excavating upstanding earthwork monuments,” Curley says.

“[Now] targeted excavation can be engaged with, which will answer our research questions while limiting the damage inherent with excavation.”

Becoming a UNESCO site

This policy of preserving Rathcroghan’s integrity and authenticity extends to tourism.

Despite its significance, Rathcroghan is one of Ireland’s less frequented attractions, drawing some 22,000 visitors a year compared with more than a million at the Cliffs of Moher.

That may not be the case had it long ago been heavily marketed as the “Birthplace of Halloween,” Curley says.

But there is no Halloween signage at Rathcroghan or in Tulsk, the nearest town.

Rathcroghan’s renown should soar, however, if Ireland is successful in its push to make it a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Irish Government has included Rathcroghan as part of the “Royal Sites of Ireland,” which is on its newest list of locations to be considered for prized World Heritage status.

The global exposure potentially offered by UNESCO branding would likely attract many more visitors to Rathcroghan.

But it seems unlikely this historic jewel will be re-packaged as a kitschy Halloween tourist attraction.

“If Rathcroghan got a UNESCO listing and that attracted more attention here that would be great, because it might result in more funding to look after the site,” Curley says.

“But we want sustainable tourism, not a rush of gimmicky Halloween tourism.”

Those travelers who do seek out Rathcroghan might have trouble finding Oweynagat cave.

Oweynagat is elusive — despite being the birthplace of Medb, perhaps the most famous queen in Irish history, 2,000 years ago.

Barely signposted, it’s hidden beneath trees in a paddock at the end of a one-way, dead-end farm track, about a thousand yards south of the much more accessible temple mound.

Visitors are free to hop a fence, walk through a field, and peer into the narrow passage of Oweynagat.

In Ireland’s Iron Age, such behavior would have been enormously risky during Samhain, when even wearing a ghastly disguise might not have spared the wrath of a malevolent creature.

Two millennia later, most costumed trick-or-treaters on Halloween won’t realize they’re mimicking a prehistoric tradition — one with much higher stakes than the pursuit of candy.

#Rathcroghan#Connaught#County Roscommon#UNESCO World Heritage#Samhain#Imbolc#Bealtaine#Lughnasadh#Tír na nÓg#Oweynagat cave#Ireland#remote sensing technology#Birthplace of Halloween#Halloween#Royal Sites of Ireland#Halloween tourism#Medb#Oweynagat#Iron Age#Irish history#archaeological site

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Good Fry

In his Dictionary of British 18th Century Painters, Ellis Waterhouse describes Thomas Frye (1710-62) as ‘one of the most original and least standardised portrait painters of his generation.’ Frye was born in Edenderry, County Offaly, a younger son of one John Fry whose father, born in Holland of English parents, appears to have settled in Ireland in the 17th century. Little is known of Frye’s…

View On WordPress

#Architectural History#Boyle#County Roscommon#Frybrook#Georgian Architecture#Historic Interiors#Historic townhouse

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The old IRA, County Roscommon, 1966

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castle Strange, Athleague, County Roscommon, Ireland

Late 1990s

0 notes

Text

The unassuming entrance to Oweynagat cave, in Rathcroghan, Ireland, belies its central role in ancient Irish history. It‘s known as a gateway to the demon-filled underworld and the birthplace of the Samhain festival, the traditional roots of Halloween. In 2021, Ireland applied for UNESCO World Heritage status for the archaeological site. Photograph By Ronan O'Connell

Inside The Irish ‘Hell Caves’ Where Halloween Was Born

Go in search of the ancient royal capital that spawned our favorite night of the dead.

— Story and Photographs By Ronan O'Connell | September 26, 2023

In the middle of a field in a lesser known part of Ireland is a large mound where sheep wander and graze freely. Had they been in that same location centuries ago, these animals might have been stiff with terror, held aloft by chanting, costumed celebrants while being sacrificed to demonic spirits that were said to inhabit nearby Oweynagat cave.

This monumental mound lay at the heart of Rathcroghan, the hub of the ancient Irish kingdom of Connaught. The former Iron Age center is now largely buried beneath the farmland of County Roscommon. In 2021, Ireland applied for UNESCO World Heritage status for Rathcroghan (Rath-craw-hin). It remains on the organization's tentative list.

The current archaeological site of Rathcroghan displays an artist’s impression of the temple that once stood there. It was the main meeting place of the Connaught kingdom 2,000 years ago. Photograph By Ronan O'Connell

Rooted in Lore

Spread across more than two square miles of rich agricultural land, Rathcroghan encompasses 240 archaeological sites, dating back 5,500 years. They include burial mounds, ring forts (settlement sites), standing stones, linear earthworks, an Iron Age ritual sanctuary—and Oweynagat, the so-called gate to hell.

More than 2,000 years ago, when Ireland’s communities seem to have worshipped nature and the land itself, it was here at Rathcroghan that the Irish New Year festival of Samhain (SOW-in) was born, says archaeologist and Rathcroghan expert Daniel Curley. In the 1800s, the Samhain tradition was brought by Irish immigrants to the United States, where it morphed into the sugar overload that is American Halloween.

Dorothy Ann Bray, a retired associate professor at McGill University and an expert in Irish folklore, explains that pre-Christian Irish divided each year into summer and winter. Within that framework were four festivities. Imbolc, on February 1, was a festival that coincided with lambing season. Bealtaine, on May 1, marked the end of winter and involved customs like washing one’s face in dew, plucking the first blooming flowers, and dancing around a decorated tree. August 1 heralded Lughnasadh, a harvest festival dedicated to the god Lugh and presided over by Irish kings. Then on October 31 came Samhain, when one pastoral year ended and another began.

Rathcroghan was not a town, as Connaught had no proper urban centers and consisted of scattered rural properties. Instead, it was a royal settlement and a key venue for these festivals. During Samhain, in particular, Rathcroghan was a hive of activity focused on its elevated temple, which was surrounded by burial grounds for the Connachta elite.

Those same privileged people may have lived at Rathcroghan. The remaining, lower-class Connachta communities resided in dispersed farms and descended on the site only for festivals. At those lively events they traded, feasted, exchanged gifts, played games, arranged marriages, and announced declarations of war or peace.

Festivalgoers also may have made ritual offerings, possibly directed to the spirits of Ireland’s otherworld. That murky, subterranean dimension, also known as Tír na nÓg (Teer-na-nohg), was inhabited by Ireland’s immortals, as well as a myriad of beasts, demons, and monsters. During Samhain, some of these creatures escaped via Oweynagat cave (pronounced “Oen-na-gat” and meaning “cave of the cats”).

“Samhain was when the invisible wall between the living world and the otherworld disappeared,” says Mike McCarthy, a Rathcroghan tour guide and researcher who has co-authored several publications on the site. “A whole host of fearsome otherworldly beasts emerged to ravage the surrounding landscape and make it ready for winter.”

Thankful for the agricultural efforts of these spirits but wary of falling victim to their fury, the people protected themselves from physical harm by lighting ritual fires on hilltops and in fields. They disguised themselves as fellow ghouls, McCarthy says, so as not to be dragged into the otherworld via the cave.

Despite these engaging legends—and the extensive archaeological site in which they dwell—one easily could drive past Rathcroghan and spot nothing but paddocks. Inhabited for more than 10,000 years, Ireland is so dense with historical remains that many are either largely or entirely unnoticed. Some are hidden beneath the ground, having been abandoned centuries ago and then slowly consumed by nature.

That includes Rathcroghan, which some experts say may be Europe’s largest unexcavated royal complex. Not only has it never been dug up, but it also predates Ireland’s written history. That means scientists must piece together its tale using non-invasive technology and artifacts found in its vicinity.

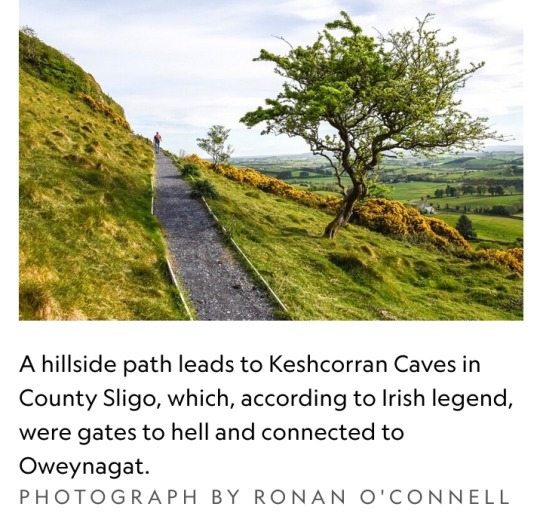

A hillside path leads to Keshcorran Caves in County Sligo, which, according to Irish legend, were gates to hell and connected to Oweynagat. Photograph By Ronan O'Connell

While Irish people for centuries knew this site was home to Rathcroghan, it wasn’t until the 1990s that a team of Irish researchers used remote sensing technology to reveal its archaeological secrets beneath the ground.

“The beauty of the approach to date at Rathcroghan is that so much has been uncovered without the destruction that comes with excavating upstanding earthwork monuments,” Curley says. “[Now] targeted excavation can be engaged with, which will answer our research questions while limiting the damage inherent with excavation.”

Becoming a UNESCO Site

This policy of preserving Rathcroghan’s integrity and authenticity extends to tourism. Despite its significance, Rathcroghan is one of Ireland’s less frequented attractions, drawing some 22,000 visitors a year compared with more than a million at the Cliffs of Moher. That may not be the case had it long ago been heavily marketed as the “Birthplace of Halloween,” Curley says. But there is no Halloween signage at Rathcroghan or in Tulsk, the nearest town.

Rathcroghan’s renown should soar, however, if Ireland is successful in its push to make it a UNESCO World Heritage site. The Irish Government has included Rathcroghan as part of the “Royal Sites of Ireland,” which is on its newest list of locations to be considered for prized World Heritage status. The global exposure potentially offered by UNESCO branding would likely attract many more visitors to Rathcroghan.

But it seems unlikely this historic jewel will be re-packaged as a kitschy Halloween tourist attraction. “If Rathcroghan got a UNESCO listing and that attracted more attention here that would be great, because it might result in more funding to look after the site,” Curley says. “But we want sustainable tourism, not a rush of gimmicky Halloween tourism.”

Those travelers who do seek out Rathcroghan might have trouble finding Oweynagat cave. Oweynagat is elusive—despite being the birthplace of Medb, perhaps the most famous queen in Irish history, 2,000 years ago. Barely signposted, it’s hidden beneath trees in a paddock at the end of a one-way, dead-end farm track, about a thousand yards south of the much more accessible temple mound.

Visitors are free to hop a fence, walk through a field, and peer into the narrow passage of Oweynagat. In Ireland’s Iron Age, such behavior would have been enormously risky during Samhain, when even wearing a ghastly disguise might not have spared the wrath of a malevolent creature.

Two millennia later, most costumed trick-or-treaters on Halloween won’t realize they’re mimicking a prehistoric tradition—one with much higher stakes than the pursuit of candy.

#World Heritage#History | Culture#Ronan O'Connell#Ireland 🇮🇪#UNESCO#Oweynagat Cave#County Roscommon#UNESCO | World Heritage Status | Rathcroghan (Rath-Craw-Hin)

0 notes

Text

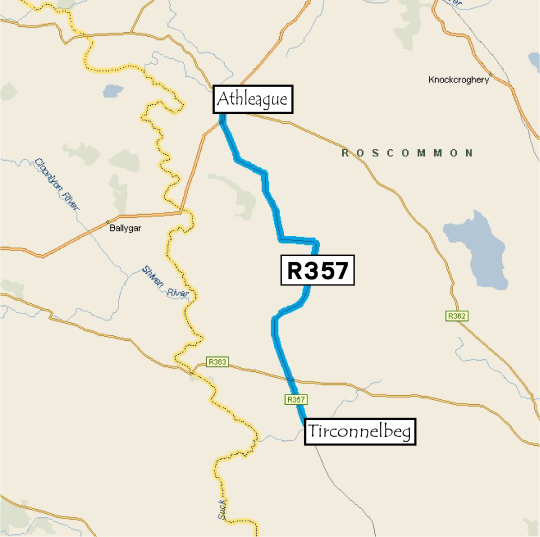

Irish Auto Trail-Tirconnelbeg to Athleague, County Roscommon

Irish Auto Trail-Tirconnelbeg to Athleague, County Roscommon

This Irish auto trail explores the R357, from the crossroads at Tirconnelbeg to the village of Athleague in County Roscommon.

For more of our Auto Trails and Slow Travels guides, available in print or eBook format, use one of the links below:

Amazon

Lulu Press

Smashwords

Camera: Sony Active Camera FDR-X3000

Vehicle: Avis Rental 2019 Opel Corsa

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

It does kill me a little bit that the character who claims not to read picked a 100% human name, but the character who owns a bookshop and works in customer service didn't.

#my post#Apparently the name Crowley came from County Roscommon and County Cork so it was probably not a human name in Golgotha the year 33 CE.#But modern day it is!#Anthony J. Crowley is a name.#A. Z. Fell is not a name.#He has a driver's license AND a firearm license what name could he have possibly used?#The answer bewilders and terrifies me.#One day I shall wake up from my slumber and a darkened shadow shall knock on my door thrice.#A knock for a name every soul has their price.#A creak and a groan from my door as a warning to protect the sanity I had. As it is what I'd be mourning.#From cracked lips the shadow shan't speak nor shall it sing.#For all the shadow shall proclaim will be in a paper safety contained.#Upon which I received the script doth proclaim “Ay Zee Fell” be the angel and “Anthony J. Crowley” the serpent's name.#With claws outstretched the shadow shall announce “as ye eyes read these words ye agree to the price”.#An open extension but a threat of ice.#For before I shall come to a decision I shall have fallen to the floor collapsed without vision.#(Do you ever just close your eyes and type out what comes to the top of your head? No backspacing or editing?)#Love a bit of stream of consciousness tagging. Not inefficient WHATSOEVER.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

my friends are in ireland at the moment and they sent me a picture of my ancestral county and I CAN’T WAIT TO GO VISIT😭

#one day i will see what county roscommon looks like in person#if i didn’t have my sister’s wedding going on soon. i’d be hopping on the next flight to dublin lol#don’t mind sakizm

0 notes

Text

the gortnacrannagh idol

unearthed in 2021 from a bog in county roscommon, ireland

and a reconstruction

91 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not from the ask list but the characters in ur fics as Irish counties and why?

anon, this has absolutely sent me. i have genuinely never seen something more up my alley.

let's start with characters we can pull from the series for ireland's six superior counties, shall we...

antrim = oliver wood

a county full of lads who've never met a spivvy tracksuit they don't think is the height of fashion, and who have a vastly inflated sense of their success at sports.

armagh = tom riddle

armagh has a [deservedly] bloody reputation. he could settle down in the murder triangle. he'd like that.

down = draco malfoy

people who live in co. down really like thinking they're better than the rest of us just because it's easy for them to get to belfast [lads, how's that something to boast about?], so they have to be the series' whiniest flop.

fermanagh = rubeus hagrid

fermanagh is full of docile lads who build things, in my experience.

londonderry = ron weasley

canonically gorgeous, gorgeous girlies live in this fine county - by which i mean, of course, that i do. we deserve to be represented by the series' most gorgeous girly. and a ginger sweetheart with six siblings [so you know which side of the sectarian divide his parents are on...] would go down a storm with our mams.

tyrone = harry potter

my brother once had his nose broken in a pub in strabane, which doesn't sound particularly interesting until you realise that my brother is a priest.

by which i mean - a county filled with people who are reckless, quick-tempered, and always ready to throw hands? it can only be represented by one man...

---

and then the rest...

carlow = quirinus quirrell

the most interesting thing there is a big rock.

cavan = percy weasley

everyone i've ever met from cavan has been really boring and really tight. so there's that.

clare = ginny weasley

because it's gorgeous, in a not like other girls way.

cork = albus dumbledore

look at this canon line and tell me dumbledore's not a cork man...

"In fact, being — forgive me — rather cleverer than most men, my mistakes tend to be correspondingly huger.”

donegal = sybill trelawney

always away with the fairies up there... and always drunk too.

dublin = walburga black

everyone you've ever met who lives in dublin is genuinely shocked to discover that the rest of the world exists beyond the m50. it's not not giving "has never set foot in muggle london and would die before she did".

galway = arthur and molly weasley

galway is the home of the nation's sophisticated [and, apparently, sexually adventurous] culchies - which fits two people from clearly quite distinguished backgrounds who nonetheless live the way they do...

kerry = gilderoy lockhart

you will never see american tourists get scammed more glamorously than in kerry.

kildare = regulus black

considerably less interesting than - and devoid of identity in comparison to - its neighbour, dublin.

kilkenny = charlie weasley

all they do is have red hair and hurl.

laois = daphne greengrass

on account of her irrelevance.

leitrim = sally-ann perks

on account of her irrelevance.

limerick = bellatrix lestrange

limerick used to be known as "stab city". she'd fit right in.

longford = mungundus fletcher

gombeen men abound.

louth = myrtle warren

because they [by which i mean the two people i know who were born there...] are always fucking moaning.

mayo = remus lupin

perpetually mopey, unless they reckon they're great at something.

meath = cormac mclaggen

they wish they were as class as the lads in dublin.

monaghan = cuthbert binns

genuinely couldn't locate it on a map.

offaly = grawp

i mean, who fucking knows? the entire place is a bog.

roscommon = aberforth dumbledore

you can guess why...

sligo = fred and george weasley

wheeler dealers, the lot of them.

tipperary = fleur delacour

the home of gorgeous, gorgeous girlies with striking accents.

waterford = dobby

they love a good strike.

westmeath = hermione granger

not somewhere you'd expect you'd choose to live if you were a bit of a know-it-all. and yet.

wexford = neville longbottom

they love to bang on about the soil.

wicklow = marge dursley

she drives a range rover and looks down on anyone who farms, change my mind.

[other answers from this ask game]

#asks answered#very normal fic writer asks#northern ireland posting#republic of ireland posting#why have i done this

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ordnance Survey - Turas - music in the orbit of the Ghost Box/Clay Pipe binary sun, incorporating field recordings from ancient burial sites in Ireland

Turas (Journey) is the most ambitious Ordnance Survey record to date. The field recordings used on Turas were captured with both analog and digital devices at passage and wedge tombs across Meath, West Cork, Wicklow, Connemara and Roscommon. To make use of the tombs' acoustics, elements like percussion were recorded in the tombs and through the process of re-amplification (playing pre-recorded material back in the tombs), this 3000 year old reverberation became a major part of the sound world that the listener experience. Turas is an electronically mediated journey that allows these historical sites to become an important collaborative factor in the creative process. Guest collaborators include Roger Doyle (Piano), Garreth Quinn Redmond (Violin), and Billy Mag Fhloinn (Yaybahar.)

Recorded and Produced by Neil O'Connor between May 2021 and July 2022 at the National Concert Hall Studios, Ballferriter, Co.Kerry, Willem Twee Studios, Den Bosch, Holland and at historical sites around Ireland.

Instruments

Piano, Bass, Drums, Shakers, Bells, Tambourine.

Synthesizers

Moog Voyager, Moog Opus Three, Korg Mono Poly, Roland Juno 60, Roland JX3P, Sequential Circuits Pro One, Sequential Circuits Prophet 4 & 5, EMS VCS3

Modular Synthesizers

Make Noise Shared System Plus, Serge System, ARP 2500

Test Equipment

Rhode & Schwarz Oscillators x 12, Rhode & Schwarz Octave Filter x 3, Hewlett-Packard 8005A Pulse Generator, Hewlett-Packard 8006A Word Generator, Hewlett-Packard 3722 A Noise Generator, Hewlett-Packard 3310B Function Generator, EG&G Parc Model 193 Multiplier/Divider.

Recording Equipment

Revox A70, Tascam Model 80, Uher Monitor Report, Sony TC-40, Zoom H4

Garreth Quinn Redmond (Violin)

Billy Mag Fhlionn: Yaybahar

Roger Doyle (Piano)

Artwork & Layout: Gavin O Brien

Supported by Final County Council & The Arts Council of Ireland

#Bandcamp#Ordnance Survey#experimental#hauntology#ireland#2023#Scintilla Recordings#electronic#field recordings

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

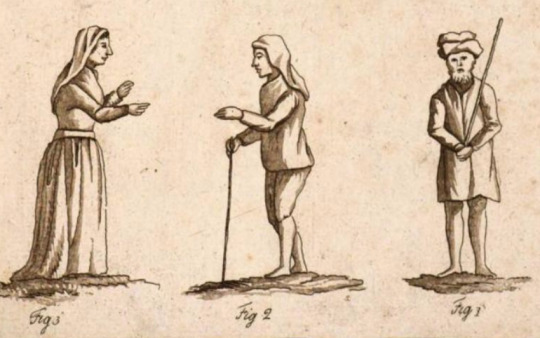

Identifying J.C. Walker's Illustrations

An Historical Essay on the Dress of the Ancient and Modern Irish by Joseph Cooper Walker published in 1788 was the first major work published on Irish dress history. Due to a combination of the limited information known at the time, and his erroneous assumption that Irish dress didn't change for the entirety of the Middle ages, Walker got a lot of things wrong, so his writing isn't cited much anymore. Some of his illustrations, however, are still used.

Because Walker lived before the invention of photography, he used drawings of historical Irish art created by colleagues and family to illustrate his book. I decided to track down the original works of art to see how Walker's drawings compared. I am resorting these into roughly chronological order, because Walker's lack of regard for chronology makes my head hurt.

The High Crosses, 9-10th centuries:

Ireland's high crosses have unfortunately lost a lot of their detail due to erosion, making these hard to identify. Sadly, the breeches with a fitted knee-band and the skirt gathered to a waistband look more Late Medieval or Early Modern than they do Early Medieval, so I don't think these are reliable depictions of the lost detail.

Plate 1: Figure 1 (right) is supposed to be from the Clonmacnoise Cross of Scripture. At a guess, it's based off the guard on the right arresting Jesus:

Figures 2 and 3 are based off a high cross fragment at Old Kilcullen, County Kildare. Unfortunately, I don't think the original carving survived. I initially blamed its loss on the United Irishmen, but this drawing from 1889 convinced me that acid rain was the real culprit.

Plate 5 Figure 1 is supposed to be a king from Muiredach's cross. The closest image I could find on the actual cross is Cain killing Able:

Ironically, Cain and Able have more embellishment on their clothes than the "king" based off of them.

12th century:

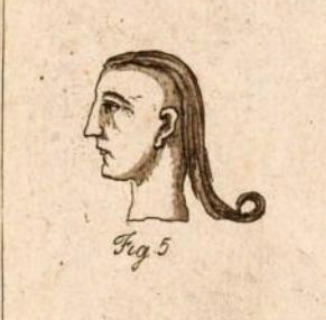

Plate 1 Figure 5 is from the capital of an arch at St. Saviour's Priory in Glendalough, County Wicklow. The drawing gives the impression that the sides of the head were shaved and the hair was deliberately curled at the end. In the actual carving, the hair is slicked back at the sides and interlaced with adjacent design elements. These are stylistic elements of Irish Romanesque art and not intended to be a realistic depiction of an Irish hairstyle.

13th century:

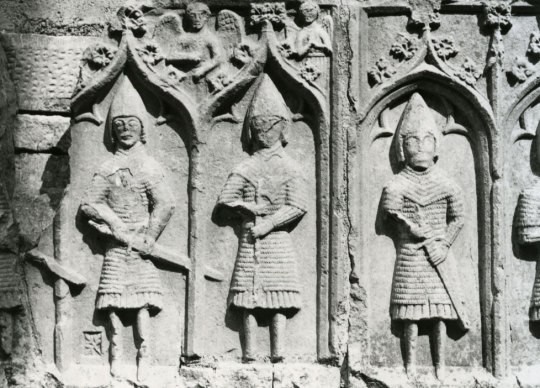

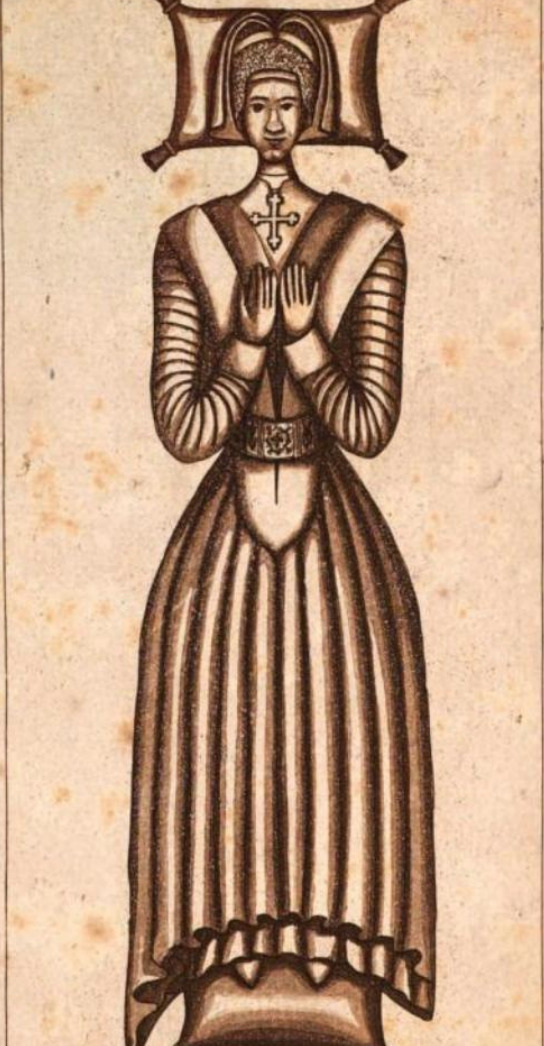

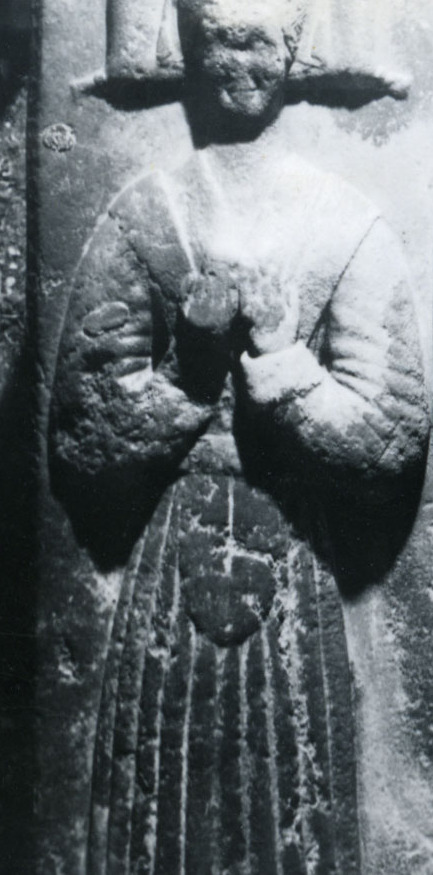

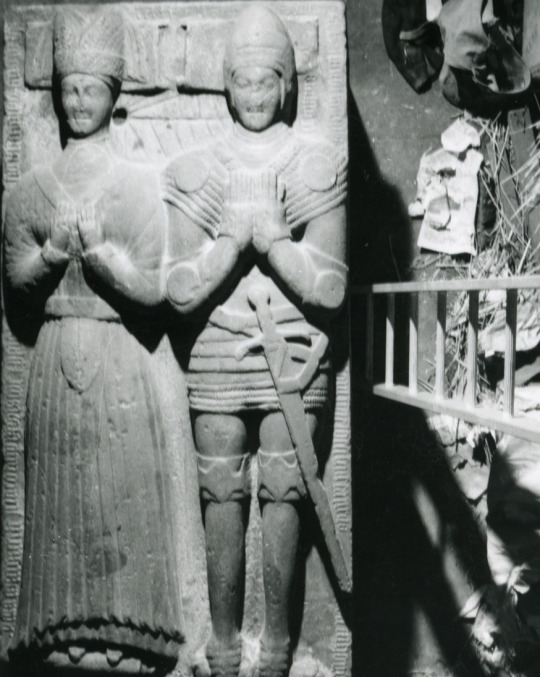

Plate 4 is the late 13th century effigy of Felim O'Connor, Dominican Priory of St. Mary, Roscommon with a frontal of gallowglasses added in the 15th c.

This drawing is pretty accurate, although the gallowglasses are lacking some details like their quilted cloth gambesons.

photos by Edwin Rae

I cannot find a good photo of Felim O'Connor's effigy, but Conor O'Brien's contemporary effigy at Corcomroe Abbey, County Clare wears the same style of clothing.

13-14th century?

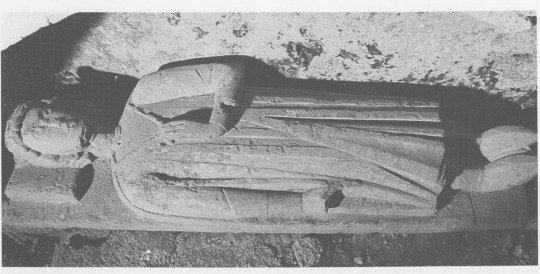

Plate 6 is based on a sculpture from Athassel Priory in County Tipperary. I can't find a solid date for this one. Athassel Priory was built c1200 and then burnt and rebuilt twice before it was dissolved in 1541. The clothing style of the carving makes me think it's from the earlier part of this time frame.

The biggest thing the drawing gets wrong is the gender. This is a man, not a woman. The "necklace pendent" on his chest might have actually been a brooch holding his cloak, but the sculpture is now too damaged to tell. The drape of fabric at his side, which Walker calls a train, is actually the edge of his cloak. The drawing also leaves out the way his become more fitted below the elbow.

15th century:

Plate 3 Figures 1-3 are based off a painting at Knockmoy Abbey.

I'm pretty sure those are houppelandes on the left and center figures. This continental fashion influence shows up elsewhere in 15th c. Ireland (Dunlevy 1989). The drawing omits the massive houppelande sleeves and shortens their hems.

The painting is now badly weather and difficult to see. This is a more accurate drawing published in 1904. Recent photograph here

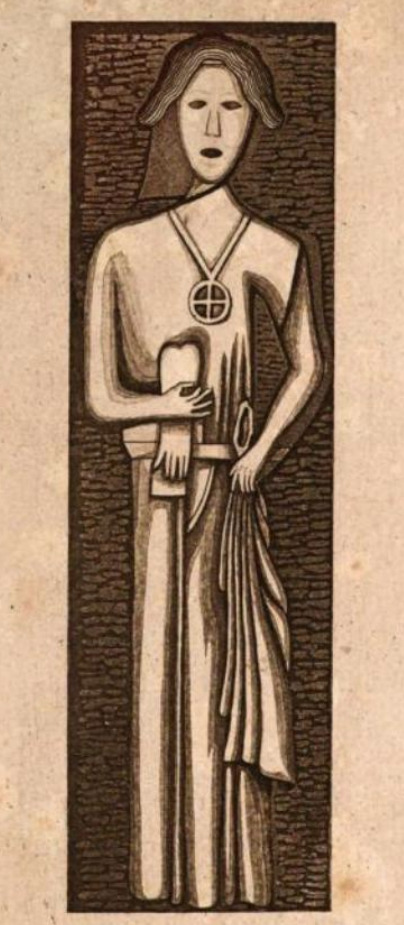

Plate 5 figure 2 and plate 1 figure 6 come from a 15th c. grave at the Dominican Friary, in Strade, County Mayo.

Figure 2 is a decent representation, although it adds a center front slit to the leine which I don't think is actually there. Figure 6 gets the silhouette of the cotehardie a bit wrong and omits the hanging belt accessories, but its greatest crime is that it makes the top of the hood look like a separate object. Walker actually misidenifies it as a Scotch bonnet.

photo again by Edwin Rae

Plate 7 is Anne Plunket's effigy at St. Mary's Church, Howth, County Dublin. This drawing is decent, though the sleeves are a bit too slim. The cross necklace and belt decorations are no longer visible on the effigy.

photos by MVP Edwin Rae

Plate 8 figures 1 and 2 are both based on a late 15th c. tomb at the New Abbey in Kilcullen, County Kildare. Figure 1 is based off a carving which is probably depicting St. Brigid, which makes her headwear the wimple of an abbess, not a laywoman's kerchief Walker. The drawing, however, omits her telltale crozier. The drawing makes it look like she has cuffed sleeves, but that is actually just the folds of her brat draped over her arm. It also shows her as wearing 2 layers of skirts when she is actually wearing a single lower garment with a hem circumference so large that it puddles at her feet.

Figure 2 is based of Margaret Janico's effigy. The effigy is now too badly eroded to make out details, but it originally probably looked very similar to Margaret Janico's other effigy in St. Audoen's Church, Dublin. Unlike Anne Plunket's effigy above, the necklace and belt decorations are still faintly visible on the Dublin effigy. Figure 2 distorts the construction of the gown and headwear. This drawing makes the bodice of the gown look heavily stiffened or even boned like 17th c. stays. The houppelande on the effigy does not have stiffening in it.

effigy of Margaret Janico and husband at St. Audoen's Church, Dublin (photos, once again, by my man Edwin)

The headpiece in the drawing looks like a linen kerchief wound up to form a turban with a decorated fillet tied over it. The headpiece on the effigy is probably actually a truncated hennin with a veil pinned to it like the one in this mid-15th c Burgundian painting by Petrus Christus.

16th century:

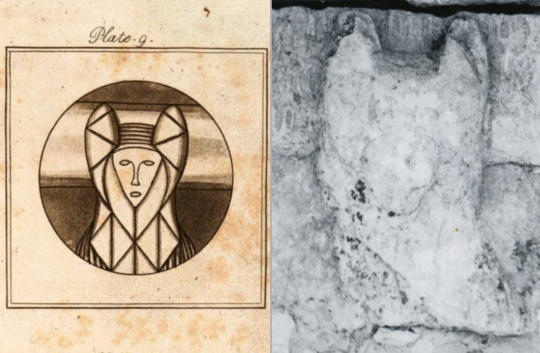

Plate 9 is based on Katherine Molloy's early 16th c. effigy at Fertagh Church, in County Kilkenny. According to the artist's notes it was in "nearly perfect" condition at the time. I wish he had put more detail into the drawing.

(photo also by Edwin Rae)

17th century:

Plate 10 is based on The Taking of the Earl of Ormond in anno 1600. Walker's artist clearly fabricated some detail here, falsely giving the impression that triús were ankle-length. We know from extant examples from Kilcommon, Dungiven, and Killery that triús actually extended past the ankle, covering part of the wearer's foot (Dunlevy 1989, Henshall et al 1961).

Plate 11 was taken from the tomb of Sir Gerald Aylmer (died 1634) and Juliana Nugent. Sadly, it appears to have been destroyed in the early 19th c, so I have no further pictures of it. The clothing looks to me like typical 1630s English fashion with loose gowns over doublets, falling bands, and linen cuffs.

? Century

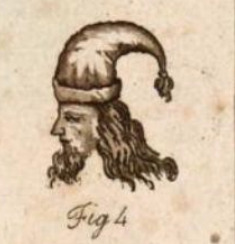

Plate 1 figure 4 is apparently from Old Kilcullen, County Kildare. I am not sure what this is based on. I haven't seen any Santa hats at Old Kilcullen. Or anywhere else in Medieval Ireland.

Bibliography:

Dunlevy, Mairead (1989). Dress in Ireland. B. T. Batsford LTD, London.

Henshall, Audrey, Seaby, Wilfred A., Lucas, A. T., Smith, A. G., and Connor, A. (1961). The Dungiven Costume. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 24/25, 119-142. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20627382

Edwin Rae's invaluable collection of photographs of Late Medieval Irish art accessed via TARA.

#15th century#irish dress#dress history#irish history#art#early medieval#16th century#historical women's fashion#historical men's fashion#historical fashion#hiberno norman#gaelic ireland#headwear

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Commodious and Comfortable

‘As soon as I got hither, I ran to my building, and had the pleasure to find every thing very well…The Scaffolding is all down, and the House almost pointed, and It’s figure is vastly more beautiful than I expected it would be. Conceited people may censure its plainness. But I don’t wish it any further ornament than it has. As far as I can judge, the inside will be very commodious, and…

View On WordPress

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

today's Writer Search History™

Parts of a light bulb

what gemstones are good for memory

What are light bulb wires made of

geology of County Roscommon

How to dismantle a light bulb

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

SAD END FOR THE VENUE OF IRELAND'S FIRST MUSIC FESTIVAL!

You'll find Galey Castle teetering on one corner of what was once an impressive 4-storey tower house, on the western shores of Lough Ree near Knockcroghery in County Roscommon. The castle was built in 1340 by William Bui O’Kelly; at the time the O’Kelly Clan were Chieftains of South Roscommon/East Galway. In 1351 William invited all the poets, brehons, bards, harpers, gamesters and jesters he could muster to Galey Castle for Christmas. Often described as a poet, warrior and visionary, he organised the festival because he feared the Gaelic way of life and culture was under threat. The gathering lasted until February 1st, St. Bridget’s Day, and became known as Ireland's first Fleadh Ceol (music festival).

In 1650 Oliver Cromwell’s troops laid siege to Galey Castle. The O’Kelly clan resisted and, for their defiance, were taken to Creggan and hanged on the stepped hill just north of the village, now commonly known as Hangman’s Hill.

(M) 💚

Pic. Wiki, J.daly2

53 notes

·

View notes

Note

#7 & #10 for Sophie? [ellie-e-marcovitz 😊]

7. Where is your OC's family from? Does your OC feel a close connection to that place? Why or why not?

Sophie’s family is from Wales, England, and Ireland. Her father’s family can be traced to Cardiff, Wales and County Roscommon through Max Pembroke, Counties Donegal and Tyrone, Ireland and Kent and Devon, England through William Devlin, and County Limerick, Ireland through her grandmother, Maureen Pembroke’s family. On her mother’s side, Sophie’s ancestry is mostly found in and around London, England.

Sophie does feel a connection to Ireland. She was born in Boyle, County Roscommon, Ireland and spent her whole life there. That’s the main reason why she feels such a connection to Ireland. She feels less connected to her Welsh and English roots. She’s visited London quite a bit over the years because that’s where her maternal grandparents were. She’s also been Cardiff once.

10. What's the first significant injury your OC remembers getting? Did it leave any scars?

The first significant injury that Sophie remembers getting is when she broke her arm. She was six at the time and was learning to ride a bike without training wheels. It didn’t go very well and when the bike veered off the pavement, Sophie wasn’t able to stop it. She broke her arm. This incident did not leave any scars, but it took another year for Sophie to learn how the to ride a two wheeler bike.

oc asks: roots edition

2 notes

·

View notes