#Han Bennink

Photo

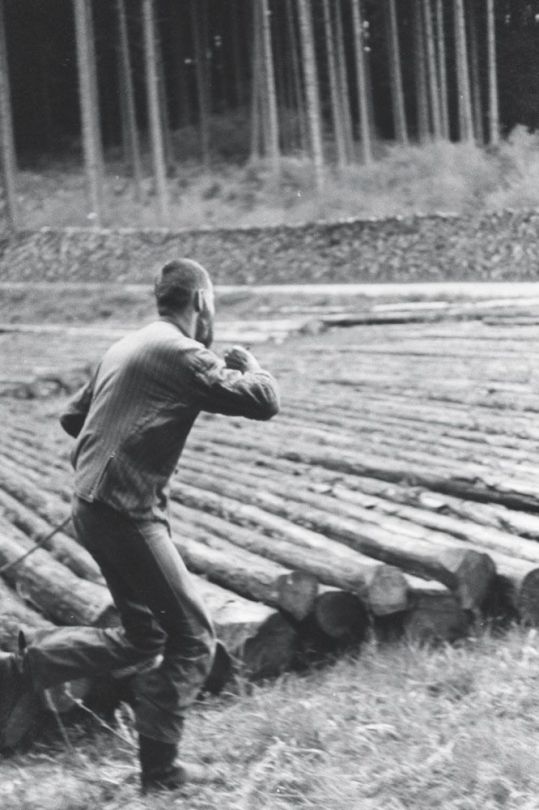

Peter Brötzmann and Han Bennink during the open-air recording sessions of "Schwarzwaldfahrt", 1977.

#peter brötzmann#han bennink#schwarzwaldfahrt#free jazz#free improvisation#fmp#free music production#black forest#1977#peter brotzmann

123 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

evan parker / dererk bailey / han bennink -- the topography of the lungs [album, 1970]

18 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Leo Cuypers - Heavy Days Are Here Again (1981) live at “De Kroeg” Amsterdam

Leo Cuypers: Piano

Han Bennink: Drums, Soprano Saxophone, Trombone

Willem Breuker: Saxophone, Clarinet

Arjen Gorter: Bass

#1980s#netherlands#Leo Cuypers#Han Bennink#Willem Breuker#Arjen Gorter#jazz#free jazz#avant-garde jazz#bebop#amsterdam#de kroeg#1981#week 9-2023

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Brötzmann / Bennink - Schwarzwaldfahrt (1977) FULL ALBUM

#rip peter brotzmann#han bennink#free improvisation#experimental music#field recording#woodwinds#game calls#forest#bottles and cans#clap your hands

0 notes

Text

youtube

Evan Parker/Derek Bailey/Han Bennink

Titan Moon

from the lp The Topography Of the Lungs

0 notes

Text

Diez de... agosto de 2022 (I) Por Pachi Tapiz [Grabaciones de jazz]

Diez de… agosto de 2022 (I) Por Pachi Tapiz [Grabaciones de jazz]

Inauguramos la sección Diez de… de Pachi Tapiz con el repaso a diez grabaciones (más o menos) de lo más variado. Ken Vandermark, Perico Sambeat, Dave Rempis, Manuel Mengis, Juan Vinuesa, Wadada Leo Smith, Günter Baby Sommer, Moisés P. Sánchez, otok o Count Basie acompañado de cuatro vocalistas de primera son los protagonistas de las primeras grabaciones que pasan por la sección.

Cada día diez del…

View On WordPress

#Aerophonic Records#Andrew Cyrille#Annie Ross#Antonio Lucaciu#Anzic Records#Audiographic Records#Claire Rousay (percusión); Ken Vandermark#Count Basie#Damon Locks#Dave Lambert#Dave Rempis#Elisabeth Harnik#Fabian Almazan#gene bertoncini#Günter Baby Sommer#Günter Baby Sommer And The Lucaciu 3#Hamza Touré#Han Bennink#Hans-Peter Pfammatter#Ike Sturm#Intakt#Jack DeJohnette#Jason Roebke#Javier Hagen#Joe Williams#Jon Hendricks#Josh Berman#Juan Vinuesa#Juan Vinuesa Quartet feat. Paul Stocker#Julien Catherine

0 notes

Text

Listening Post: Wadada Leo Smith

Regular Dusted readers probably require no preamble or primer when it comes to Wadada Leo Smith. A stalwart leader, innovator and educator in creative improvised music across six decades, Smith ascended to octogenarian status on December 18th of last year. The Finnish TUM imprint prefaced that momentous occasion with a series of physical releases organized around instrumentation and collaboration, with colleagues both longstanding and comparatively recent to Smith’s voluminous sound world.

Four were released in 2021, including the solo Trumpet, Sacred Ceremonies teaming Smith in duos and trio with Milford Graves and Bill Laswell, The Chicago Symphonies composed for his Great Lakes Quartet, and A Sonnet for Billie Holiday with Vijay Iyer and Jack DeJohnette. Production delays prevented the release of the final two entries until June 2022. Emerald Duets engages Smith in diverse dialogues with a revolving roster of drummers that includes DeJohnette, Andrew Cyrille, Han Bennink, and Pheeroan akLaff. String Quartets Nos. 1-12 delves deeply into an under-documented side of his oeuvre in featuring pieces for two string ensembles and a small cadre of guest soloists.

In sum, it’s a massive and magisterial amount of material, gorgeously recorded and lovingly presented. A fitting tribute to Smith at this milestone of his life and work and a noble case of “giving him his flowers while he’s still with us.” Dusted writers participating in this Listening Post were understandably daunted the prospect of digesting and discussing so much music. Smith’s sustained artistry and imagination were instant agents in assuaging and even allaying such fears. In the interests of expediency and economy our ensuing conversation focuses on the final two sets in TUM’s series, starting with Emerald Duets.

Intro by Derek Taylor

Derek Taylor: Precedence was on my mind a lot when listening to these discs. Trumpet and drums still aren’t a common combination. As far as I know, the first recorded example dates to Roy Eldridge and Alvin Stoller, who recorded a trio of duets while waiting for other players to show up at a Benny Carter studio session on March 21st, 1955. A fourth track featured Eldridge on overdubbed piano. They still sound striking today in their vibrant collisions of melody and rhythm. Smith’s most certainly intimately familiar with them.

youtube

Of the six releases in the 80th Birthday series, Emerald Duets and Trumpet feel the most allegiant to and resonant with the arc of Smith’s career from start to present. Percussion in the tradition of the AACM’s “little instruments” has been part of his personal palette from the beginning, featuring prominently in his solo Kabell projects from 1972 and 1979. Dialogues with drummers were a natural progression. There are a handful of recordings in that format that predate this set and show off Smith’s predilection for picking partners ready to go all in on the conversations. I’m really curious to learn what others have gleaned from many highlights of these meetings.

Bill Meyer: Duos in general, and duos with percussionists in particular, are an important facet of Smith’s work. While some recent efforts, such as Ten Freedom Summers, use larger ensembles to make grand artistic statements, the duos can be very personal encounters; personally, I find their intimacy very appealing. I remember reading somewhere that Smith said he thinks it is important to break bread with a duo partner, even when their dietary habits are very different than his. At the time, he was talking about Anthony Braxton. Of all the times I’ve seen Smith perform, the one that affected me most was a duo concert with the German percussionist, Günter Baby Sommer. They have decades of rapport, and it showed in the ways they supported each other making really poetic, beautiful statements. Besides Sommer, the drummers he has previously recorded duets with include Ed Blackwell, Adam Rudolph, Jack DeJohnette, Milford Graves, Sabu Toyozumi and Louis Moholo-Moholo. Emerald Duets enlarges that number by three. He’s worked in many other settings with Andrew Cyrille and Pheeroan akLaff; I’m not informed about Smith's history with Han Bennink. John Corbett did an interview with Smith in 2015 for Bomb magazine where Smith mentions seeing Bennink play, but I don’t know if he’s ever played with him before.

Marc Medwin: If he has worked with Bennink before, I've not heard of it either. I heard about the food symbiosis from him directly, and yes, relating to Braxton, about 15 years ago. Performative intimacy has long been paramount to Smith, as we hear as far back as the Creative Construction Company material and the Kabell Years retrospective. What fascinates me is that, like Bill Dixon, even when Smith works in duo, his take on that intimacy can be quite malleable. The sound can be large, sometimes monumentally so. Maybe it's something about the space and dynamic range in his playing, or maybe it's simply the way the instrumentalists react and interact in the environment Smith has created via the score. Just as a point of comparison, on Coltrane's Interstellar Space, I do not hear that huge sense of physical space as

much as lines in intersection. Each piece on The Emerald Duets sounds very spacious to me, in a physical sense.

Michael Rosenstein: This series celebrating his 80th birthday has been a treasure trove of interesting work. What's particularly interesting about this batch of duos with drummers is how they draw on musicians he's had a longstanding association with. I can't find specific documentation but it seems likely that Smith and Jack DeJohnette crossed paths in Chicago in the 1960s as part of their activities with AACM if not at the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, NY in the 1970s. Smith's 1970s collaborations with Pheeroan ak Laff are better documented including a set from Studio Rivbea as part of the Wildflower series and as part of and early New Dalta Ahkri lineup from New Haven. I'm not sure if Smith and Bennink ever played together, but they were both part of Derek Bailey's Company 6 and Company 7 recordings from 1977 so they were at least traveling in the same circles. The earliest documentation I can find of his collaborations with Andrew Cyrille are from the late 1990s playing in a group assembled by John Lindberg. But it seems like their paths might have crossed earlier in New York.

That's a lot of collective experience in this set!

Bill Meyer: DeJohnette moved to NY from Chicago in 1966, and Smith came to Chicago after being in the army in January 1967. But it’s fair to suppose that Smith knew of him from the 1960s on, given DeJohnette’s involvement with Miles Davis as well as his Chicago roots. George Lewis mentions in his AACM study, A Power Stronger Than Itself, that DeJohnette was a frequent presence at Creative Music Studio.

youtube

Derek Taylor: Smith and Sommer have an excellent disc on Intakt, Wisdom in Time, from 2006 and the trio they shared with Peter Kowald from a quarter-century earlier is one of the touchstones of the FMP catalog. So much rapport and mutual listening on display, as Bill notes, and congruous willingness to go pretty much anywhere with the music. It’s a common thread in Smith’s work and I love the “food symbiosis” descriptor as a synopsis of the intentional cultivation of differences-intact cause and effect.

Among these duets, I had the greatest anticipation for the session with Bennink. I’m not aware of any earlier recordings of the two outside the Company disc that Michael mentions and Bennink’s singular brand of intensity, levity and piebald swing feels like a novel foil for Smith. It doesn’t disappoint in that regard. Smith’s penchant for verbose dedicatory titles is in florid bloom and there’s a fascinating emphasis on naming individuals and locales across time and space. Familiar figures (Louis Armstrong, Ornette Coleman, Albert Einstein) are named alongside others (Dorothy Vaughn, Mary Jackson) that had me referencing Google. The open dynamics that Marc notes are on full display with Bennink reigning in his more extravagant impulses. It's like an extended meditation with strong, sharp teeth occasionally bared.

youtube

Bill Meyer: Derek, your point about the titles that Smith gives to the music draws attention to one of the things that I think Smith has in common with Braxton or Dixon: he doesn’t just want to play, he wants to put out a lot of information. The immensity is part of the point. In Smith’s case, this involves spiritual, cultural, sensate, social, scientific and aesthetic concerns. But this can coexist with an attention to tonal and gestural detail; the music asks you to think both big and small. At its best, the music does both, and so far, I find that in the encounter with DeJohnette, where there’s an evident, cooperative give and take between the players, and also titles that reference rarified experiences and interdisciplinary inquiry.

I say so far because I’ve only listened to the duos once or twice each, and I think that the choice to package several full sessions in a box corresponds to a request to consider this music’s messages for a while now, and also for a long time afterwards. One spin is just getting started. On my first listen, the duo with Bennink sounds like two skilled musicians having some fun playing together.

Derek Taylor: Bill, I like your observation about immensity as intentionality and the comparison to output of Braxton and Dixon. The latter’s Odyssey set (five discs of mostly solo trumpet and flugelhorn and a sixth with spoken exegesis of the same) is a spiritual precursor to Smith’s Trumpet and a similarly deep, transportive dive. That kind of fecundity runs the risk of feeling like listener homework when engaged beyond a sampling, but I think Smith largely sidesteps the issue in the breadth and allure of these sets. Even with the economy of instrumentation on Emerald Duets, there’s a wealth of variety and interplay that’s consistently satisfying.

DeJohnette gets the most time with Smith over two complete sessions and I agree, there’s a very productive workshop feel to their encounters that goes well beyond that of a casual conclave. One of the dates is also set apart in that both men double on pianos (acoustic and electric). These are the discs I’ve spent the least time with so far, but that’s primarily because of a desire for repeat visits to the Bennink and Cyrille sessions.

Getting back to meaning-rich titles, the Cyrille has a canny mix of dedicatory pieces and refreshingly political ones. Jeanne Lee, Donald Ayler and Mongezi Feza get the shoutouts and “The Patriot Act, Unconstitutional Force that Destroys Democracy” (a piece also interpreted on the first DeJohnette session) leaves no equivocation as to Smith’s political and humanist sensibilities. Gratifying to see local Representative Ilhan Omar garner a piece on the Cyrille session. It makes me wonder if she’s heard it, and if not, invites the temptation to drop a copy off at her office in downtown Minneapolis.

Jennifer Kelly: I know a lot less about Smith than most of you, though once, on a trip to Chicago, I met up with Bill Meyer at the University of Chicago to see him play and accept some kind of award? (Bill do you remember the details?) It was an incredible evening, very warm and welcoming. I remember one of his grandchildren running around, and everyone very tolerant of that, kind of a family vibe. I think I had already heard a little bit of his work, maybe Ten Freedom Summers?

vimeo

In any case, I am also enjoying the drummer duets and finding that I really like Smith's trumpet tone, which is full of air and seems softer and less piercing than other players. It's very ruminative and evocative to my ears. We've been talking about him primarily as a composer, which, fair enough...but what do we think about him as a performer and interpreter of his music?

I've also been dipping into the string quartets and wanted to draw your attention to a piece in the New York Times, which talks about his unusual notation ...one of the reasons that this material is not performed very often.

The difference between his drummer duets and these very lush, romantic classical string is really striking. What do you guys see as the common thread?

Derek Taylor: Jenny, I agree about the inviting nature of Smith’s brass tone(s). There’s clarity and elasticity to it across time that’s extraordinary. He can play harsh and discordant with a mastery of wide array of extended techniques. Although more often there’s a sonorousness suffusing his phrases that’s disarming, but also direct. He found his instrumental voice early and has shaped it to so many different settings to the degree that he’s pretty easy to single out, no matter the ensemble size. A similar singularity informs his architectures for strings, which I was initially surprised by, but then realized I probably shouldn’t have been.

Separating Smith’s composing and playing is difficult for me. There seems to be so much overlap and interaction between the two disciplines. That’s true of many improvising musicians, but it feels particularly so with Smith. The Duets are an excellent example of this intersectionality with each drummer confidently bringing their individual tool kits to bear on the cues and structures, which don’t just encourage, but entreat such interplay.

Probably an unfair and perhaps unanswerable question, but is there a drumming partner amongst the four that resonates most with folks?

Bill Meyer: Jen, I think we saw him play in October 2015 with a version of the Golden Quartet, with (iirc) Anthony Davis on piano, John Lindberg on bass, and Mike Reed on drums. I don’t recall an award, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. That concert stood out to me because I felt like Smith was kind of playfully messing with Davis and Lindberg. Most times, Smith has a kind of esteemed elder air about him. They were playing some of his graphic scores, and I particularly remember Davis seeming a bit flummoxed.

Smith has incorporated elements of classical instrumentation and forms for decades; on the Spirit Catcher album, which was recorded c. 1979, he performs with a harp trio, and on Ten Freedom Summers, the four-disc work that was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 2013, the music switched between the Golden Quartet, a ten-piece chamber ensemble, and a merger of the two. I haven’t dipped too far into the string quartets yet, but in general I really value the presence of Smith as a player in his music. His trumpet brings things into focus for me.

youtube

Marc Medwin: I love the description of the quartets as Romantic! In a very fundamental way, they are, not that they sound like Mahler or Tchaikovsky. I'm listening to the 9th quartet as I type, and harmony's this wonderfully open and malleable thing, certainly not atonal! The more I think about it, I hear the duets as pretty Romantic as well, and I mean that in the sense of size, as we've been discussing, and in the sense of fluidity as one event melds with another, forms and spaces in which boundaries aren't so much transgressed as disappear. Smith's trumpet tones can sound like that. One pitch can take on many

shades and even…what, characters?

Christian Carey: The duets are so captivating. Without a harmony instrument (except the few places when piano is introduced, which I particularly liked), it is up to Wadada Leo Smith to fill in the implications of harmony with single trumpet lines, which he does with a keen sense of progression. That said, the duets are primarily about Smith's soaring melodic style and the sharing of rhythmic ideas between him and the various drummers.

There is a bridging of the gap between duet partners. Smith plays differently with each of the drummers, acknowledging their musicality. All of the drummers bridge the gap as well, doing a fine job of arriving in Smith's orbit. I was particularly struck by how Smith and Han Bennink met in the middle, with the drummer discarding some of his more manic incursions to truly inhabit Smith's compositions.

Bill Meyer: Yeah, Bennink eschews both the antic side of his late free approach and his pre-bebop swinging brushes approach. He meets Wadada where he’s at and just plays.

So far, my favorite duets are the ones with DeJohnette. I think they share an inclination to compose in real time, which leads to their music having an especially patient, thoughtful quality.

Smith’s notation system is called Ankhrasmation. Here’s an interview that includes some discussion of it. https://bombmagazine.org/articles/wadada-leo-smith/

Derek Taylor: Smith elucidates influences on his string quartet writing in the set’s accompanying book, starting with Ornette’s Town Hall 1965 piece “Dedication to Poets and Writers” and moving through the works of Bartok, Beethoven, Debussy, Webern and Shostakovich. Alongside a broad list of African American composers from Scott Joplin to Alvin Singleton, he weaves in B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf and John Lee Hooker. Smith also parcels his compositions into four temporal periods. The dozen pieces documented in the box comprise three of these periods, with a fourth consisting of three more compositions as yet unrecorded corresponding to 13th, 14th, and 15th Constitutional Amendments ratified during the Lincoln Presidency.

In Smith’s words: “My aspiration was to create a body of music that is expressive and that also explores the African American experience in the United States of America. My music is not a historical account. I intend that my inspiration seeks a psychological and cultural reality.”

He continues, “I therefore construct a music that relies on non-traditional components and concepts that allows a shared responsibility for the horizontal flow of the music, including the creative ability to reshape recurrences of musical moments both with interpretations and expressions, to introduce new and different languages into a single work and use that language as a form of expansion and not as a development.”

Lots to unpack and ponder there, and titles once again become dedicatory guideposts in signifying inspiration. The four movements of the first quartet correspond to four African American composers. The two movements of the ninth are named after Ma Rainey and Marian Anderson, respectively. The first movement of the twelfth is for Billie Holliday.

The guests that join the Redkoral Quartet on four of the 12 pieces obviously break with the conventions of the string quartet format. Christian, given your experience as a composer and theorist, I’m curious how you see Smith aligning with and diverging from the lineage of this instrumentation.

Just a side note on the presentation of these sets. As with the earlier releases in the series, the physical packaging and contents of theses final two entries are superlative. The price point is steep, but TUM spared no expense in covering the curatorial and annotative bases. It’s all appealing, from color photographs and reproductions of accompanying artwork to detailed and diverse essays and a sturdy, handsome cardboard exterior. Even interior sleeves within sleeves for the discs. As a collective 80th birthday present to an American treasure, it’s a homerun.

youtube

Justin Cober-Lake: Catching up after a few days away, I hope I don't derail things by looping back. I'm most interested in his duets with Pheeroan akLaff, mainly because America’s National Parks was my entry into serious consideration of Smith's work. akLaff told me at the time that there's an "ethos connecting the player and the score.” Listening to these duet combinations in parallel (especially given the recurrence of "The Patriot Act" allows for some thinking on that topic. How does a player connect to these complex scores, and how does that change among players? How do a pair of artists connect to each other over the same score in different ways. akLaff's work on "The Patriot Act" is my favorite of the batch, but maybe only because I feel a certain resonance there. DeJohnette seems to have more freedom; while he certainly has more time, I may be reading into the collaborative nature of that performance. I'd be curious to learn more about the process. In this case, how does Smith — who composed the piece — adjust his playing to his duet partner? Does he have something different in mind ahead of time, knowing who he's playing with (he knows these artists well) or is approach more reactive?

Derek Taylor: Thanks for linking to your piece, Justin. Even more grist to chew on. The duets feel different from Smith’s ensemble pieces to me on several fronts. Most obviously, they’re dialogues, so the material is geared towards dyadic interplay interlaced with solo expression. Something cellist Ashley Walters notes in your piece seems germane to the differences, too: “Wadada’s music is not completely fixed nor completely free: it lies somewhere in the middle where parts can slide across each other or align depending on the performance. In this way, performing with [his] ensemble is the ultimate chamber music experience: you know each part so well that you can react and create music with each other in real time.”

Each of these drummers is a deft and experienced improviser. Smith recognizes and relies on that throughout, according ample latitude to their decisions and contributions. Bennink’s a great example of that trust placed paying off in an unexpected way. Certain of his more idiosyncratic percussive trademarks are left absent in the service of preserving the tenor and poise of Smith’s compositions. It’s still identifiably Bennink behind the kit, but magnanimously attenuated to Smith and vice versa.

Justin Cober-Lake: The idea of magnanimity remains crucial to Smith's work, in various ways. His titles, his inspirations, and his culture statements make that clear in one way, but his way of interacting with his collaborators always seems to be one of clear conversation and generosity. He has very specific ideas in his compositions, but even those lend themselves toward further communication, between him and other artists and between the artists and the audience. Ankhrasmation and graphic scores are complex, academic concepts, but they're also languages that let people speak to each other in new ways while encouraging a certain amount of improvisation (Watlers' point is certainly relevant). His partners have to study this language, and part of the fun is recognizing what new sorts of ideas come out of conversation within a new discourse community. Listening to the duets lets us see that paired down to its most essential qualities.

This may point to a separate rabbit trail not worth following, but I tend to think of him working on a grand scale, taking on ideas like the national park system or the Civil Rights Movement, and the duets seem to me to be a distillation of how he works. Another way to approach them would be to start with his solo pieces (like the Monk album) and see how he builds into something with a duo, trio, strings, etc. Or maybe the solo work is just totally different, more of him as a player and less as a composer.

Marc Medwin: I would venture that the solo work, or rather I should say his solo work in particular, straddles the lines you draw. The solo set in the birthday series, Trumpet, contains compositions that also speak to all of the issues, political or otherwise, that have formed the substance of our discussion. I am drawn again and again to the inculcation of a moment's implications in Smith's work, which all of us have been mentioning in one way or another, whether in recording or performance.

There is something of the elder's wisdom in what Smith says or plays, a distillation of the spiritual and cultural continua that we often separate for convenience, and he brings similar modes of thinking and construction out of his collaborators. I find the idea of chamber music being such a huge part of the music we're discussing so close to my own thinking! He loves the term "Research," to which he refers quite a lot when discussing his work, and as those who've spent any time with him or read his interviews know, he can bring in wildly disparate notions of science, art, literature and politics at a moment's notice but somehow unify the entire discussion around a concept, opening up terminological meaning beyond expectation. So, I keep thinking, what is chamber music anyway?! What is a symphony, a string quartet, and who gets to delineate those boundaries?

Derek Taylor: Marc, I really like this passage of yours, “there is something of the elder’s wisdom in what Smith says or plays, a distillation of the spiritual and cultural continua that we often separate for convenience, and he brings similar modes of thinking and construction out of his collaborators.”

It’s an assignation that could be applied to a number of Smith’s peers. I’m thinking Henry Threadgill, Roscoe Mitchell, Braxton… even William Parker to a degree. Although magical realism and extrasensory erudition as often informs Parker’s cross-cultural cosmology isn’t really an emphasis in Smith’s perspective. Smith seems more interested in existence and reality as shaped by and expressed in tangible historical manifestations. His themes and cues transcend temporal boundaries, but they’re still grounded in factual people, places, events, etc. although not limited to those. They’re also tools in deconstructing and reconstructing or replacing established and hierarchical terminology and ideas. Chamber music in Smith’s conception feels much more inclusive and holistic than the Western classical definition, for example.

The String Quartets are customary string quartets in the sense that the members of the RedKoral Quartet play instruments associated with the conventions and traditions of that format, but how they play them and the soloists that occasionally join them resist and redefine that codification.

Marc Medwin: Yes! Threadgill and Mitchell exhibit a similarly inclusive historical bent, though you're spot on regarding Smith's spirituality, a layered tradition he takes very seriously. With Mitchell, we have transmogrifications like the semi-autobiography of Bells for the South Side, while Threadgill transfigures creative music's history with a degree of earthiness that Smith tends to eschew. An overstatement to be sure but I hope useful!

Bill Meyer: Yeah, Smith works with the sound possibilities and historical associations of the string quartet, but he certainly isn’t bound by them, any more than he’s bound by the conventions of the modern jazz combo format in the Gold Quartet.

Marc Medwin: One of the most fascinating things about Smith's music is how often he broke with those conventions, going way back to that first trio with Braxton and Leroy Jenkins when they recorded those gorgeously transparent compositions The Bell and Silence!

Derek Taylor: Smith's placed himself in so many fertile contexts over the years that I often lose track of the taxonomy. The pioneering work with Braxton that you mention, Marc, but also straight up free jazz dates with Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Marion Brown, Frank Lowe, and others, although he would likely call such idiomatic pigeon-holing unnecessary and reductive. The Yo Miles! fusion projects with Henry Kaiser and various encounters with John Zorn offer additional avenues. And Michael mentioned the Company conclaves earlier. Even the formats and assemblages he returns to (solo, duo, Golden Quartet...) share an enviable trait of retaining freshness.

Christian Carey: Others have touched on this, but the duos are primarily between musicians in their eighties. So many musicians, from Marshall Allen to Roy Haynes, have shown us that music keeps you young thinking and acting.

vimeo

Wadada Leo Smith’s 80th Birthday Celebration from Wadada Leo Smith on Vimeo.

Derek Taylor: Definitely true of Wadada, Christian. His beaming visage looks easily 20 years younger than his octogenarian age would suggest.

Michael Rosenstein: Sorry to have been lurking on this for a bit but July was a bit of a hectic month.

It’s intriguing to note that the duos with akLaff, Cyrille, and DeJohnette were all recorded within a fairly short period of time — the duo with Cyrille in September 2019, the duo with akLaff in December 2019 and the two discs with DeJohnette in early January 2020. (The duo with Bennink is from 2014, so quite a bit earlier.) The proximity of the sessions, the pieces he assembled and the history Smith had playing with each of his collaborators provides a certain through-thread to the set. But each of his partners bring their own sensibilities which comes through in each of the sessions. In the liner notes, Smith talks about wanting to see how he would respond “in each situation with a new drumming philosophy.”

Interestingly, the recording session with Bennink in Amsterdam in 2014 is what kicked off Smith’s idea to put together this recording project of drum duos. Bill references how Bennink “eschews both the antic side of his late free approach and his pre-bebop swinging brushes approach.” But, of all the sessions, not surprisingly based on his musical roots, I hear Bennink’s playing digging in most deeply to the jazz drum traditions. Of course, he extends and abstracts them, but hearing this session, I think back to hearing Smith play with Ed Blackwell (a fantastic meeting that Smith ended up releasing on Kabell.) Listen to the simmering snare rolls he calls up in “Louis Armstrong in New York City and Accra, Ghana” which swings like mad and elicits searing retorts from Smith. While more angular and pointillistic, “Ornette Coleman at the Worlds Fair of Science and Art in Fort Worth, Texas” also digs into those free-bop tendencies and Smith responds in kind. It’s also worth noting that, on this disc, in contrast to the rest of the boxed set, most of the tunes are collective improvisations credited to both players.

AkLaff’s playing is imbued with a free sense of pulse, bringing out Smith’s meditative. The name of their disc, “Litanies, Prayers and Meditations” comes through in the pacing and a markedly spare sensibility. Take the evolving miniatures of “Rumis Masnavi: A Sonic Expression” where the drummer parries with Smith’s soaring introspection. On “A Sonic Litany on Peace,” Smith’s piano playing is pared back in both is placement of notes and his choice of damping the strings to minimize the sustain of the instrument against AkLaff’s feints and bobs. Cyrille is a much more open player, often placing cymbals in the fore of his approach to the kit. On a piece like “Donald Ayler: The Master of the Sound and Energy Forms,” that metallic sizzle drives Smith to some particularly heated playing, with a burred edge to his tone. “Mongezi Feza” is a poignant ode to the South African and the tinge of reverb of the recording brings a sense of reverence. Smith’s declaratory playing meshes really well with Cyrille’s tuned kit.

The two discs with DeJohnette are more expansive and seem to reveal much more of a compositional bent, though that may be a more extensive use of the harmonic richness of keyboards. It’s been a while since I’ve listened to the duo’s Tzadik release where neither musician used keyboards so one wonders what inspired the use of keyboards on disc 4, particularly the inclusion of a piece like the lush, contemplative “Meditation: A Sonic Circle of Double Piano Resonances.” That said, the choice is quite effective both on its own and as a complement to the overall boxed set. The five-part “Paradise: The Gardens and Fountains” which comprises the final disc is an astute close to the set, giving the two the time and space to explore Smith’s considered, lyrical form. This disc deserves more time than I’ve been able to devote so far but I know I’ll return to it often.

Derek rightfully points out the deluxe packaging of the box and it is fantastic to see a label so deeply devoted to presenting Smith’s music. Of all the sets comprising this 80th celebration, the solo trumpet set edges out to the top. But The Emerald Duets comes up as a close second.

Derek Taylor: Michael, thank you for this astute summation/annotation of Emerald Duets. It captures details of each dialogue and knits them together with some insightful holistic observations. I hadn't even considered the import of the Bennink encounter as the impetus for the others and agree that it limns the more familiar aspects of a jazz-rooted duet between trumpet and drums without sounding the least bit conventional or rote. And Bennink does swing doesn't he, inimitably!

I want to express gratitude to everyone who participated; I definitely learned some things and enjoyed the opportunity to collate and communicate thoughts of my own. For an artist who’s already brought a literal library of music into the world, we have much to look forward to from Wadada Leo Smith. The unrecorded string quartets were mentioned, but I’m sure his robust relationship with TUM will yield other aural treasures. In the meantime, the 80th Birthday Series and its last two entries are here to tide us all over.

#wadada leo smith#listeningpost#emerald duo#string quartets#dusted magazine#jazz#classical music#jack dejohnette#hans bennink#Pheeroan akLaff#Redkoral Quartet#derek taylor#bill meyer#michael rosenstein#marc medwin#justin cober-lake#jennifer kelly#christian carey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Peter Brötzmann on avant-garde, playing solo and radio

"Peter Brötzmann is a revered free jazz musician from West Germany whose over 50-year career has taken him from the interdisciplinary radicalism of the late 20th-century Fluxus art movement to extensive collaborative and solo recording and performance. Peter Brötzmann talked about learning from the ’60s avant-garde, why he doesn't believe in teaching jazz and how improvisation comes down to fitting or fighting in his lecture at RBMA Berlin 2018.

Primarily a saxophonist and clarinetist, Brötzmann has worked with experimental greats such as Dutch drummer Han Bennink, British fellow saxophone powerhouse Evan Parker, and Japanese sound artist Keiji Haino, exploring an avant-garde, largely improvisational style of free jazz with his signature rough timbre. His octet album Machine Gun remains a seminal free jazz album of the late ‘60s, a genre-expanding work that aurally articulated the anxieties surrounding the Vietnam War and his country’s uncertain future. With over 100 releases to his name, including some with jazz supergroup Last Exit, Brötzmann’s creative passions have not diminished. In 2017, he released Sex Tape with steel guitarist and singer/songwriter Heather Leigh and a live album with trombonist Steve Swell and drummer Paal Nilssen-Love."

41 Comments "Last Exit is one of the all time greatest bands period"

Peter Brötzmann, the heart — and lungs — of European free jazz, dead at 82

June 23, 2023 READ MORE https://www.npr.org/2023/06/23/1184005533/peter-brotzmann-the-heart-and-lungs-of-european-free-jazz-dead-at-82

"Brötzmann also recorded with titans like pianist Cecil Taylor, drummer Andrew Cyrille and guitarist Sonny Sharrock; a 1987 duo summit with Sharrock saw release roughly a decade ago, under a typically unprintable title."

5 notes

·

View notes

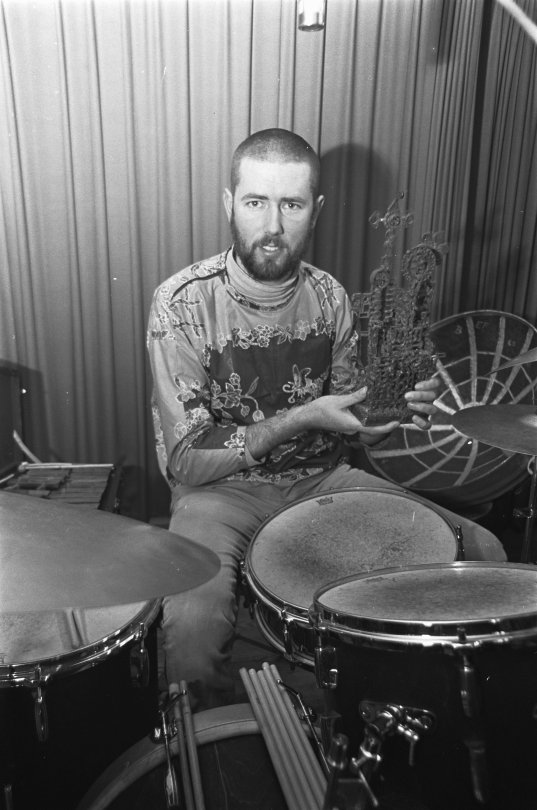

Photo

Han Bennink

18 December 1967

source: commons.wikimedia

photo: Jack de Nijs

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peter Brötzmann in the Black Forest 1977 by Han Bennink

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

impLOG! Water Damage! Misha Mengelberg, Peter Brötzmann, Evan Parker, Peter Bennink, Paul Rutherford, Derek Bailey, Han Bennink! David Toop + Peter Cusack + Steve Beresford + David Day! The Dwarfs Of East Agouza! Sharkiface! Paul Kelday! Jeff Carney! Roland Kayn! Tongue Depressor! Maxine Funke!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

And so we end this project, a little over 2,000 albums in about a year and a half. Gonna do some Sum Up things for it later, but wowzers. So much good shit. I was probably overly charitable with my 9.0's this time around, but oh well. They're celebratory I suppose.

Alias- Muted (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Aloe Island Posse- Aloe Island Adventures (6.0/10, deleted from library)

Angkor Wat- When Obscenity Becomes the Norm… Awake! (8.5/10)

Annie Gosfield- Flying Sparks And Heavy Machinery (8.5/10)

Arthur Russell- Tower of Meaning (7.0/10, probably deleting from library)

Awenden- Golden Hour (9.0/10)

Barbaro- Nolte (9.0/10)

Bone Sickness- Theater Of Morbidity (8.0/10)

Breather Resist- Charmer (8.0/10)

BT- ESCM (9.0/10)

Califone- Everybody’s Mother (Volume 1) (7.5/10)

Carlos Giffoni- Welcome Home (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Caroliner Rainbow Solid Handshake and Loose 2 Pins- Transcontinental Pinecone Collector (7.5/10)

Charli XCX- Crash (8.5/10)

The Cherry Point & John Wiese- White Gold (8.0/10)

Chicane- Far From the Maddening Crowds (9.5/10)

Chris Corsano- The Young Cricketer (8.5/10)

Cities Last Broadcast- The Cancelled Earth (8.0/10)

Cobalt- Eater of Birds (8.5/10)

Constance Demby- Novus Magnificat: Through the Stargate (8.0/10)

Cristian Vogel- Specific Momentific (8.5/10)

critical_grim- Beach Party (6.0/10, deleted from library)

Daniel Menche- Guts (8.0/10)

Dark Angel- Time Does Not Heal (9.0/10)

David Holland & Derek Bailey- Improvisations For Cello And Guitar (7.5/10)

Deathpile- Final Confession (7.5/10)

Demolition Squad- Hit It (6.5/10, deleted from library)

Derrick May- Innovator: Soundtrack for the Tenth Planet (8.0/10)

Dip in the Pool- Silence (8.0/10)

Easley Blackwood- Microtonal Compositions (7.0/10, might delete later)

Eat Static- Implant (8.0/10)

Ellen Fullman- Through Glass Panes (8.5/10)

The Ex- Mudbird Shivers (7.5/10)

Faust- So Far (8.0/10)

Fire for Effect- The Beach (7.0/10)

Future City Love Stories- 油尖旺 District (8.0/10)

Gary Clail And Tackhead Sound System- Tackhead Tape Time (8.0/10)

The Gero-P- The Gero-P (8.0/10)

Gil Evans- The Individualism of Gil Evans (8.5/10)

goreshit- with all my heart. (7.0/10)

Greg Kelley / Olivia Block- Resolution (8.0/10)

GUDSFORLADT / non-- GUDSFORLADT / non- Split (7.5/10)

Han Bennink- Solo (8.5/10)

Hantasi- Tusop® (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Hash Jar Tempo- Well Oiled (9.0/10)

Horde- Hellig Usvart (8.5/10)

Incapacitants- Unauthorized Fatal Operation 990130 (6.5/10, deleted from library)

James Rushford & Joe Talia- Manhunter (8.0/10)

Joanne Robertson & Dean Blunt- WAHALLA (9.0/10)

John Butcher- Invisible Ear (9.0/10)

John Wiese- Circle Snare (8.5/10)

Kano- Kano (7.5/10)

Kim Cascone- cathodeFlower (8.5/10)

Kit Clayton- Lateral Forces (Surface Fault) (8.5/10)

Lancaster_- Press Play (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Legal Weapon- Death of Innocence (7.5/10)

Logos- Cold Mission (8.5/10)

Magik Markers- I Trust My Guitar, Etc. (8.5/10)

Malfeitor / Strid- Strid (8.0/10)

Mammal- Lonesome Drifter (9.0/10)

Maren Morris- Hero (9.0/10)

Marina Rosenfeld- P.A. / Hard Love (9.5/10)

Mathieu Ruhlmann- The Earth Grows in Each of Us (9.0/10)

Michel Chion- Requiem (7.0/10)

Milanese- Extend (8.5/10)

Miles Davis- Sorcerer (8.5/10)

Morton Feldman- The Viola in My Life (9.0/10)

N.Y. House'n Authority- APT. (8.0/10)

New Dreams Ltd.- Eden (8.5/10)

Nile- Ithyphallic (7.5/20)

Olivia Block / Kyle Bruckmann- Teem (8.0/10)

OSCOB- Everywhere, Beyond The Skybox (7.5/10)

Pacific Despair- ~~~Devour~~~ (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Peter Brötzmann- Nipples (8.5/10)

Philip Jeck- Vinyl Coda IV (9.0/10)

Pierre Boulez- The Three Piano Sonatas (8.5/10)

Pissgrave- Posthumous Humiliation (8.5/10)

Prosumer & Murat Tepeli- Serenity (8.0/10)

Prurient- Fossil (9.0/10)

Rajlib- Palm Readings (8.0/10)

Recloose- Cardiology (7.5/10)

The Rita- Lake Depths Lurker (8.5/10)

Robert Rich- Somnium (8.5/10)

Rollergirl!- Rollergirl (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Ryoji Ikeda- Matrix (8.0/10)

Sea Of Voices- Softcore Mall Inc. (7.0/10, deleted from library)

Sierra On-Line- Glass Shutters (8.5/10)

Soft Machine- Third (9.5/10)

Spokane- Able Bodies (6.5/10, deleted from library)

Steve Lehman- Sélébéyone (8.5/10)

Tim Berne- Fulton Street Maul (9.0/10)

Trist- Zrcadlení melancholie (9.0/10)

Tristan Murail- Gondwana/ Désintégrations / Time and Again (9.5/10)

Vatican Shadow- Kneel Before Religious Icons (6.0/10, deleted from library)

VentureX- Noctis Labyrinthus (8.0/10)

Whitehouse- Erector (8.0/10)

Whitehouse- Mummy and Daddy (8.0/10)

Yoshimi- Tokyo Restricted Area (6.5/10, deleted from library)

Yukiko Okada- Venus Tanjou (7.5/10)

死夢VANITY- f a n t a s y 真夜中のアパート (8.0/10)

14 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Nica's dream - Wes Montgomery 1965.

Wes Montgomery playing Nica's Dream

with three Dutch musicians:

Pim Jacobs: piano,

Ruud Jacobs: bass

Han Bennink: drums

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE TAKEOVER (2022) Crime thriller on Netflix on Nov 1st - trailer

THE TAKEOVER (2022) Crime thriller on Netflix on Nov 1st – trailer

The Takeover is a 2022 Dutch crime thriller film about an ethical hacker who is framed for murder and must evade the police.

Framed for murder after uncovering a privacy scandal, while trying to track down the criminals blackmailing her.

Directed by Annemarie van de Mond from a screenplay co-written by Hans Erik Kraan and Tijs van Marle. Produced by Femke Bennink and Annemieke van Vliet.

The…

View On WordPress

#2022#Annemarie van de Mond#crime thriller#Dutch#ethical hacker#Frank Lammers#Geza Weisz#Holly Mae Brood#movie film#Netflix#Susan Radder#The Takeover#trailer

3 notes

·

View notes