#Hispano-Suiza

Text

Hispano-Suiza K6 "Break de Chasse" 1937. - source Cars & Motorbikes Stars of the Golden era.

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

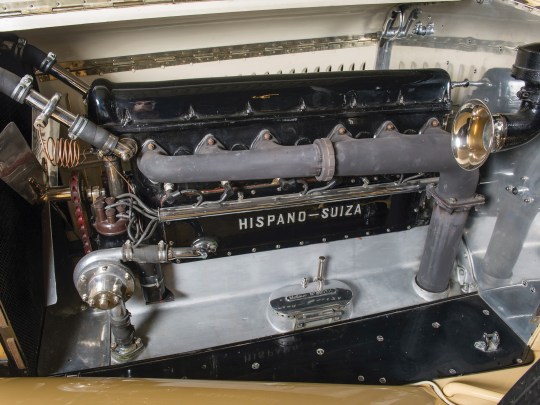

1928 Hispano-Suiza H6C Transformable Torpedo by Hibbard & Darrin

85 notes

·

View notes

Photo

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

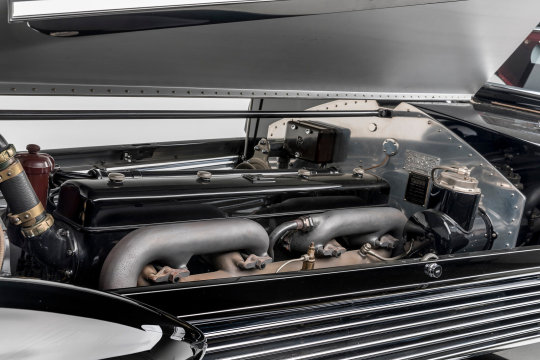

The Mullin Collection’s 1933 Hispano-Suiza J12 Cabriolet,

Coachwork by Carrosserie Vanvooren,

Michael Furman for the Mullin Automotive Museum,

Courtesy of Gooding & Company.

Parisian coachbuilder was responsible for this J12 Cabriolet’s

#art#design#vintage cars#vintage car#luxury cars#luxury car#luxury lifestyle#hispano-suiza#cabriolet#luxurylifestyle#luxurycar#luxurycars

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Rolls-Royce Phantom I Jonckheere Coupe

The first Rolls-Royce Phantom — then called the New Phantom, presently called the Phantom I — was introduced in 1925 in response to competition from European luxury marques like Hispano-Suiza and Isotta Fraschini and from premium American automakers like Packard and Pierce-Arrow. Based on the chassis of the outgoing 40/50 model, now known as the Silver Ghost, the Phantom introduced Rolls-Royce's first overhead valve engine and four-wheel brakes (although some sources say front brakes were introduced in late production Silver Ghosts). The OHV engine was taller than the sidevalve motor. That affected styling. The bodies coach built for the Phantom I had higher hoods, radiator shells and cowls.

In 1934, an as-yet-unidentified owner took the Phantom to the Jonckheere body company near Roeselare, Belgium to be rebodied. Though Henri Jonckheere built his first luxury automobile in 1902, the company had transitioned to making mostly bus and coach bodies by the 1930s. It still exists today as VDL Jonckheere.t’s not known who designed it, but Jonckheere built a radically different coupe body. Some say it was inspired by the aero designs of stylists Jacque Saoutchik and Joseph Figoni — but, to my eyes, it’s not nearly as elegant and flowing as their work. The squarish Rolls-Royce grill was retained, but it was sloped back to give the tall grill a more streamlined look. It is perhaps the only classic era Rolls-Royce whose grill is not vertical. To say the least, the car is a bit controversial with traditional Rolls-Royce enthusiasts. The windshield is also steeply raked. Bullet headlights and very long and flowing fenders continue the streamlined theme, but the car is so massive it’s hard for me to call it sleek. To finish off the aero look, Jonckheere put a big tailfin down the length of the middle of the trunk lid. Such fins were popular with European coachbuilders in the 1930s and you can see them on Bugattis, Delahayes and other custom-bodied cars of the era. Designer Raymond Loewy added one to his customized 1939 Lincoln Continental.

Of course, the Rolls’ most distinctive features are its large rear-hinged round doors, which allow ingress for both front and rear passengers. Because of the odd door shape, the side windows are split vertically and open up like a scissors as they retract into the doors. Round fender skirts for the rear wheels echo the shape of the doors.

The car is almost 20-feet long and finished in dark black. It’s a big, almost ominous looking vehicle that would be at home in a Batman movie, driven by the villain.

It’s not a very practical car. With ponderous weight and no power assist, the steering is difficult, particularly at low speed. The non-synchro transmission needs to be double clutched and, even though the car features Rolls-Royce’s servo-assisted mechanical brakes, the weight makes it hard to stop. The large turning radius, low ground clearance and extended rear end make maneuvering the vehicle difficult. The steeply sloping fastback roofline forces rear passengers to slouch. There is no back window to speak of, just louvers, so visibility isn’t the best. To make the most of the limited trunk space, there is a set of fitted luggage.

#Rolls-Royce Phantom I#Hispano-Suiza#Isotta Fraschini#Packard#Pierce-Arrow#Jonckheere#Lincoln Continental

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

1937 Hispano-Suiza K6, complete with an original, one-of-one woody wagon body by Franay.

Technically, it’s not a “wagon” but a “Break De Chasse,” which is French for “Shooting Brake,” and no doubt it was intended as a utility for hunting and other activities. There might be more opulent longroofs, but you’d probably have to go to the Sultan of Brunei’s warehouse to find them. Instead, we went to the Mullin Museum last week.

Somewhat ironically, the K6 was actually a simplified lower-end model when it was new, as the French side of the company was struggling in the mid-1930s with a bunch of amazingly exotic cars that very few people could afford, but all Hispanos are serious exotica today, and 1937 was the last full year of production at Bois-Colombes before the French side became strictly an aero-engine company, though the Spanish side continued on longer.

While cars like this are still blue-chip collector cars and probably always will be, there isn’t as much interest in pre-war exotics as there once was. Their stories are still worth telling, however, and this Hispano is still a work of art.

Though often thought of as a French automaker, and this K6 was built in France, Hispano-Suiza means “Spanish-Swiss,” and was founded in Barcelona by Swiss engineer Marc Birkigt, along with financial manager Damián Mateu in 1904. Born in Geneva in 1878, Birkigt was mechanically gifted from an early age and graduated from engineering school in 1898, briefly working in the watch trade and a gunsmith during his military service, but it was railways and electric locomotive work that brought him to Spain.

Hispano-Suiza was an outgrowth of two earlier, failed ventures Birkigt had worked for. The first was an electric vehicle company, La Cuadra, that wanted to make an electric bus, later followed by a two-cylinder, Panhard-like car. When that failed the company was taken over by José María Castro Fernández, who took over and had Birkigt engineer another car, the four-cylinder Castro, only for his finances to fail and the firm become as Hispano-Suiza in June 1904.

Birkigt was an engineer on par with Frederick Henry Royce, and the early Hispanos boasted lots of innovations, including combining the engine and gearbox into a structural unit that could add rigidity to the chassis, and they were well-liked. The company’s fortunes were greatly boosted when King Alfonso XIII bought a trio of 20-24 Tourers at the 1905 Barcelona show, and when Birkigt designed his first truly great sporting car in 1908, he returned the favor by naming the T-headed, high-revving monster the “Alfonso XIII.”

Royal patronage was great, but Spain was a poor country with terrible roads, and Hispanos were expensive cars. In 1911, the firm set up a satellite factory at Levallois-Perret in Paris and later moved to Bois-Colombes, with Birkigt soon taking up residence there. While the Alfonsos and other Hispano Suizas had lots of competition success, WW1 was spent mainly on aero engines, and Birkigt’s OHC airplane V8s were light, powerful, and durable, and their design later informed Hispano’s cars.

After the war, the ultimate Hispano-Suiza car, the H6, debuted in 1919. Production would last until 1933, although a few were finished in 1934 and, if you had enough money, you could buy one as a one-off even later.

With 6.6 or 8.0-liter straight sixes, the H6s were glamorous in the same way Isotta-Fraschinis were, but often much nicer to drive and far superior handlers thanks to their very rigid frame, friction dampers, and other advances. Hispano-Suiza was an early adopter of four-wheel brakes and brake boosters, and H6s could hit up to 85 mph. They were also beautiful, and when Harley Earl was tapped to design the 1927 LaSalle, he essentially copied the H6.

Over time, the Spanish and French factories, separated by management and geography, grew apart in ways that few modern concerns would. Barcelona often fielded a wider range of more humble products and also built lots of commercial trucks and wagons. Bois-Colombes built only the finest cars and aeronautical engines. In many cases, Spain built a design far longer than France would. Both were happy for the success of the H6, and there were many other types in the 1920s that came and went.

The depression threw a big monkey wrench into this situation just as Bois-Colombes was getting ready to launch the 54CV, 9.4-liter V-12-powered J12 in 1931. Although it had some lesser models, Hispano-Suiza’s French side was essentially all-in on top-tier luxury cars. In 1933 even the “Junior” chassis cost more than a fully-assembled Bugatti Type 57.

The K6, with a simple OHV 5.2-liter, ~120-hp straight-six, and 3-speeder with a dry-plate clutch, was created to offer something more affordable but preserve the quality and image that the H6 had so carefully cultivated. It could not reverse the economic tide for the company, but it did sell pretty well for a very expensive car during a time of economic calamity. Plus, it was well-made and nice to drive. Carrosserie Vanvooren provided the “off-the-rack” K6 bodies, but this was always a coachbuilt car.

While less expensive than the 220-hp J12s, the K6 was nevertheless a car for the privileged few. This one, chassis 15121, was first owned by Maurice Solvay, businessman grandson of Belgian chemist and inventor Ernest Solvay and husband of French actress Josette Day. By the time Solvay bought it, however, the end was near for the car line at Bois Colombes.

The Spanish Civil War threw that side of the company into chaos, though car production continued in Barcelona until 1943, while the French side was slyly taken over by the Government in 1937. They had it focus on aviation and defense contractor projects, and car production was wound down in 1938. The company continued as a defense contractor for another 30 years, but the two sides were permanently split.

Chassis 15121 was originally a cabriolet sedan, but in 1948 Solvay decided to turn it into a Break de Chasse, and turned to Franay, an old-line coachbuilder founded by former carriage interior maker Jean-Baptiste Franay in 1903 and later run by his son Marius.

Franay was one of many automotive ateliers in Levallois-Perret, the beating heart of France’s custom coachbuilding scene before WW2 and after (Chapron and Figoni et Falaschi were very nearby). While postwar Franay creations are usually pretty over the top like those of Saoutchik, the order here was functionality and beauty. Mission accomplished.

The car had a series of owners after Solvay’s death in 1960, including Renault designer Philippe Charbonneaux. It had a light restoration in the 1980s, and then a more comprehensive one when Peter Mullin bought the car in 2002, including replacing its Water Buffalo-hide interior

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1938 Hispano-Suiza Dubonnet Xenia. Commissioned by Andre Dubonnet in 1937 to showcase his company's latest suspension development. Art Deco.

Photo by kitchener.lord

#1938#car#hispano-suiza#art deco#hispano-suiza dubonnet xenia#andre dubonnet#30s cars#art deco car#dubonnet#auto#dieselpunk#steamline#30s auto#30s#1930s#1930s cars#30a auto#1930s auto

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Evolution 2: Far Off Promise has a rare piece of artwork featuring Mag, Chain and Pepper in a car (said artwork has, to my knowledge, only been featured in Dreamcast Magazine).

The car in question appears to be a Hispano-Suiza make car. I specifically drew a comparison with the Hispano-Suiza J12 as that one has the “strips” on the front half of the car (though a bit hard to see in the photo due to them being the same color as the car itself).

In-game, the Launcher Residence has a garage, though the player can’t enter it, leaving its interior a mystery. One of the earliest concept art pieces does show Mag, Linear and Gre in a similar luxury car while being chased by an airship. Both of these fit with the implication that the Launchers used to be wealthy before falling into spiraling debt.

#Evolution#The World of Sacred Device#Far Off Promise#Evolution 2#Evolution Worlds#Mag Launcher#Chain Gun#Pepper Box#Hispano-Suiza

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

La belle Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia

Nouvel article publié sur https://www.2tout2rien.fr/la-belle-hispano-suiza-h6b-dubonnet-xenia/

La belle Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia

#années 1930#art deco#course#custom#dubonnet#Hispano-Suiza#pilote#tuning#vidéo#vintage#voiture#automobile#imxok

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1928 Hispano-Suiza Type 49 Coach

Collection Pierre Héron

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

1924 Hispano-Suiza H6C "Tulipwood"

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hispano-Suiza H6 Dubonnet “Xenia” Coupe 1938 by André Dubonnet. - source Cars & Motorbikes Stars of the Golden era.

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

1935 Hispano-Suiza J-12 Pillarless Sedan by Carrosserie Kellner

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

This car charmed the eye. Like a huge yellow insect that had dropped to earth from a butterfly civilisation, this car, gallant and suave, rested in the lowly silence of the Shepherd's Market night. Open as a yacht, it wore a great shining bonnet, and flying over the crest of this great bonnet, as though in proud flight over the heads of scores of phantom horses, was that silver stork by which the gentle may be pleased to know that they have just escaped death beneath the wheels of a Hispano-Suiza car, as supplied to His Most Catholic Majesty.

Michael Arlen, The Green Hat

#quote#quotation#Michael Arlen#The Green Hat#car#insect#butterfly#Shepherd's Market#yacht#bonnet#crest#stork#Hispano-Suiza

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hispano-Suiza (1929)

#cars#cool#cool cars#car#classic car#vintage#motor#classic#drive#driving#friday#weekend#christmas#1920s cars#1920s fashion#1920s style#1920s art#1920s#hispano suiza

281 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia (1938)

The history of the Hispano-Suiza marque begins in 1898, with Spanish artillery captain Emilio de la Cuadra starting electric car production in Barcelona under the name ‘La Cuadra’. Along the way he met Swiss engineer Marc Birkigt and hired him to work for the company in Spain, before they ultimately got bought out by José María Castro Fernández in 1902 and were renamed ‘Fábrica Hispano-Suiza de Automóviles’ (Spanish-Swiss Automobile Factory). A bankruptcy followed, but a 1904 restructuring saw them return as ‘La Hispano-Suiza Fábrica de Automóviles’, introducing four new engines over the next two years: a 3.8-litre; a 7.4-litre four-cylinder; and two large six-cylinder units. During World War I, Hispano-Suiza designed and produced aircraft engines under Birkigt’s direction, and is credited with the first practical ‘cast-block’ aero engine, and the first V8 aero engine.

Hispano-Suiza introduced the Marc Birkigt-designed H6 at the 1919 Paris Motor Show. It used a straight-six engine inspired by Birkigt’s aero efforts, but essentially half of his aero V12 design with a new overhead camshaft mechanism that made 160 bhp with a 6.6-litre displacement. It also excelled in the form of braking, using alloy drums all-round with the first power assist the industry had seen – under deceleration, the car would use its own momentum to provide braking power. This technology was later licensed to various other manufacturers, including Rolls-Royce.

This car is completely unique. The car you are looking at is a Hispano-Suiza H6B (a later model, with slightly more power) by clothed in a bespoke body by Saoutchik. The story starts with André Dubonnet, an inventor, racing driver and World War I fighter pilot who made fortunes from his engineering brilliance. To showcase a new independent suspension system he had developed for cars, he purchased a Hispano-Suiza H6 chassis and engine (slightly upgraded to H6C specs) and collaborated with Jean Andreau on its exterior design. The ‘Xenia’ (named after his deceased wife) was fitted with ‘Hyperflex’ suspension of his own design, with him claiming it had “the suppleness of a cat”, hence the Dubonnet logo. This technology was leaps and bounds ahead of the competition and was later used by General Motors with their Cadillac, Buick and Oldsmobile brands. The Xenia was also the first car to use curved windows, of which moved in a ‘gullwing’ fashion (as the doors hinged back rather than out).

The Xenia was Dubonnet’s personal car and was hidden during World War II, until the opening of the Saint Cloud tunnel in June 1946, where Xenia led the parade.

25 notes

·

View notes