#Louis Krevel

Text

ab. 1833-1836 Louis Krevel - Heinrich Böcking

(Saarlandmuseum)

97 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1835 Marie-Louise Stumm by Louis Krevel (Saarland Museum, specific location ? - Saarbrücken, Saarland, Germany), From Wikimedia; darkened upper lft side and left side of top with Photoshop 2023X2599 @314 2.2Mj.

1830s Lady in Blue by Franz Schrotzberg (auctioned by Dorotheum). From costumecocktail.com/2016/08/11/lady-in-blue-ca-1830s/; expanded to fit screen 2326X2868 @144 6.4Mp

#1835#1830s#Romantic era fashion#late Georgian fashion#Marie-Louise Stumm#Louis Krevel#straight hair#bun#tiara#earings#necklace#off-shoulder scoop neckline#pleated bertha#Gigot sleeves#waist band#natural waistline#full skirt#Franz Schrotzberg#side curl coiffure#off-shoulder straight neckline#mameluke sleeves

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

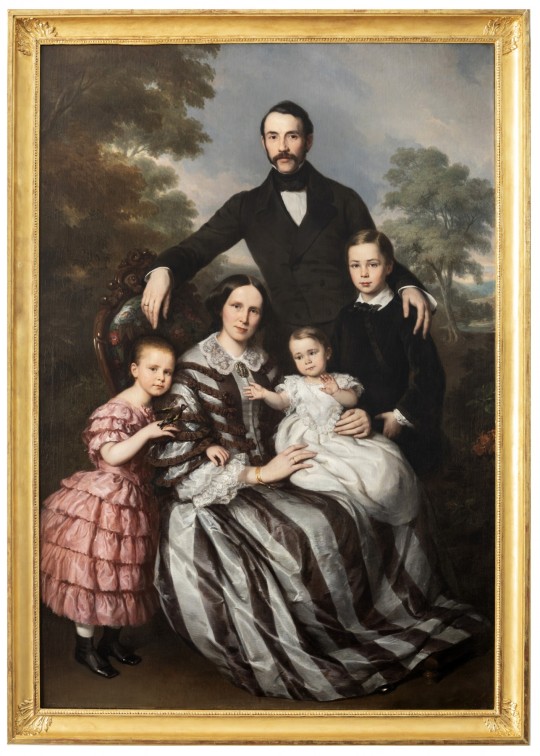

Louis Krevel (b.1801 - d.1876), 'Portrait of Emil Albano Korte and his Family', oil on canvas, c.1856, German, for sale for 32,000 EUR at Galerie William Diximus; Saint-Ouen, France.

From Antic Store:

Our portrait represents the industrialist Emil Albano Korte (1817-1895), his first wife Amalia Rolffs (1823-1864) and their three children. The eldest of the children, Gottlieb Albano Friedrich Korte (1848-1902) is shown in dark costume alongside his father. Julie Natalie Korte (1852-1921) on the left is wearing a pink ruffle dress. She leans on her hand a small bird distracting her sister Liuse Pauline (1855-1943) sitting on the lap of their mother, whose movement brightened the front pose of the group. The pyramidal composition of the painting accentuates the stability of this family portrait and the tender complicity between its members. The landscape in the background offers both a natural setting while suggesting the extent of the Korte family's landholding. (x)

#louis krevel#known artist#known sitter#oil on canvas#1850s#german#gallerie william diximus#saint ouen#known sitters

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fraldarius

Felix/Annette Version

Based on the famous painting "Family Portrait" by Louis Krevel

#felannie#netteflix#fire emblem#fire emblem three hopes#three hopes#tumblr radar#artists on tumblr#nintendo#commission#three houses#artists of tumblr#fire emblem three houses#annette fantine dominic#felix hugo fraldarius#fraldarius#fe3h#blue lions#black eagles#crimson flower#golden deer#azure moon#verdant wind#fe3h fanart#my art

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

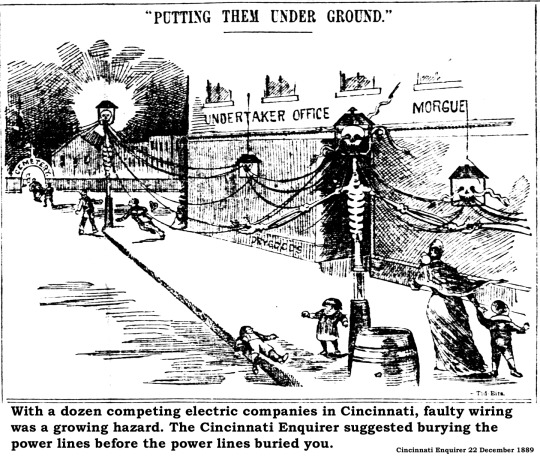

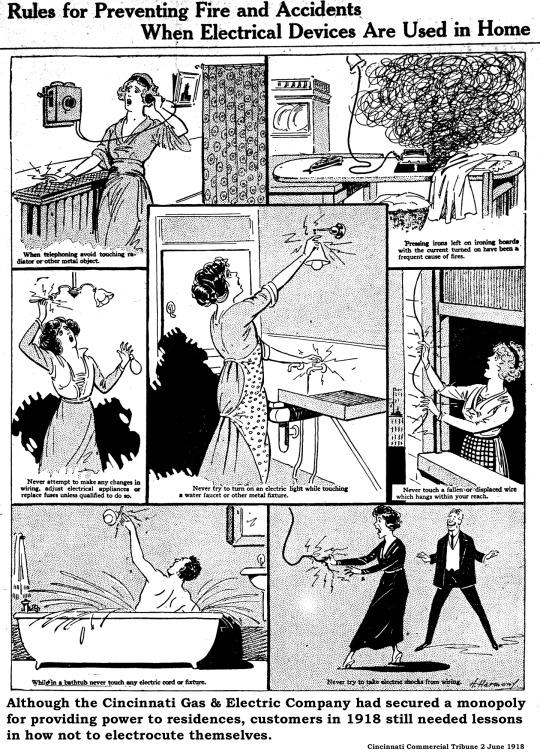

Cincinnati Cautiously – And Dangerously – Accepted Electricity Over Several Decades

Cincinnati was shocked, so to speak, in 1898 when Father John Van Krevel, pastor of St. Francis Xavier Church on Sycamore Street approved the installation of 216 electric lights on the church’s altar. The very idea of substituting electricity for candle-power was contentious. The Cincinnati Post [31 January 1898] reported that Philadelphia’s archbishop had prohibited electric lights in that city’s churches, while prelates in New York, Milwaukee, St. Louis and Detroit were more open to progress.

Some hesitation was likely generated by the fly-by-night nature of many electrical contractors back then. Louis H. Rockafellow, the electrician behind the St. Xavier project, split town just a few months after controversially electrifying that church, leaving behind a pile of bills and a jilted fiancé. In 1898, eight companies offered electrical service in Cincinnati, each using proprietary methods and machinery that were incompatible with any of their competitors. Until the Edison Company built a distribution station on Plum Street, there was no electric service as such – if you wanted electric lights, you installed your own generator.

Cincinnati adopted electricity gradually, in fits and starts, over five decades. The first mentions of electric lights in Cincinnati involved special events and exceptional venues. The city’s 1873 Industrial Exposition featured a bright electric torch illuminating Elm Street outside the Exposition Buildings (soon to be replaced by Music Hall). In 1878. the Highland House atop Mount Adams experimented with electric illumination, prompting a review [24 May 1878] in the Daily Gazette:

“Two burners were put up in the hall and they fairly flooded the place with a pure white light that made the bar gaslights within sight appear dull and yellow.”

A lot of hesitation was based on the inherent dangers of electricity. There is no question that open flames generated by candles and gas fixtures caused a lot of fires but, in most cases, people could quickly extinguish most such blazes with a bucket of water or a smothering blanket.

Electricity was unquenchable and killed quickly, sometimes horribly. Aaron Lyman, stringing wire on Vine Street between Ninth and Court for the Cincinnati Electric Light Company, caught hold of a poorly insulated wire and was roasted alive within view of a hundred spectators. According to the Cincinnati Post [3 May 1895]:

“Blue tongues of flame, large in some places and minute in others, spit and darted from all over his body. From the finger tips rolled green balls that danced from wire to wire and finally spent their force and disappeared. From his eyes darted fiery flames, while every hair on his head was the receptacle of the deadly fluid that was rapidly destroying life.”

Michael Landrigan, a lineman for the Brush Electric Light Company, escaped a similar fate in 1889. Each morning, Landrigan cleaned and trimmed the electric arc lamp in front of Havlin’s Theater on Central Avenue between Fourth and Fifth. One day in November, he climbed an iron ladder to reach the lamp, but had not properly shut off the power. As he grabbed the lamp, he was shocked into paralysis, unable to let go as he screamed for help. A crowd of 500 gathered, but no one knew how to assist until a clerk in a nearby clothing store climbed a pole on the opposite side of the street and switched the power off.

Lena Standigal, a janitress at City Hall, was almost electrocuted in 1897 while dusting an electric fan in the water Works Office.

The Findlay Street bridge over the Miami & Erie Canal was electrified in 1904 when an overhead trolley wire came undone and draped across the iron railing of the bridge.

“A drove of hogs first discovered the new condition of things. The peculiar thrills of an electric shock were evidently not to their liking. Refusing to proceed, they stood as if paralyzed, lifting one foot at a time and trying to shake off the tingling current. A chorus of squeals accompanied this exercise.”

Horses unleashed showers of sparks from their horseshoes as they pranced over the bridge, leaping about like frisky colts until a passing electrician shut off the current.

Adolph Drach’s saloon on Walnut Street south of Fifth exploded on Monday, 4 May 1896. Eleven people died and a dozen more suffered serious injuries. An electrical generator installed by the Triumph Electric Company in the basement of Drach’s saloon was gasoline-powered, supplied by a 60-gallon fuel tank that leaked fumes. To turn on the generator, an operator descended into the dark cellar, carrying a candle or lantern. Drach’s saloon was basically a large Molotov cocktail. The explosion completely flattened Drach’s building and a neighboring structure, punched holes through the walls shared with a barber shop to the north and another saloon to the south. All the windows in the Gibson Hotel across the street blew out, and two street cars got knocked off the tracks

By 1900, it was obvious that the electrical free-for-all set loose in Cincinnati had to stop. It was also obvious who was going to win the competition. General Andrew Hickenlooper, president of the Cincinnati Gas, Light and Coke Company was deeply imbedded in the political machinery of the city. Hickenlooper tended to resist innovation – he didn’t replace toxic “town gas” with natural gas until years after other cities made the switch – but recognized that a monopoly position was attractive to his shareholders. The consolidation deal was signed in May 1901 and the new monopoly, christened as the Cincinnati Gas & Electric Company, began buying up previous competitors, large and small. The biggest company to be swallowed up was the Cincinnati Edison Company, valued at more than $7 million. Smallest was the Brush Electric Light Company, valued at just over $14,000.

Well into the 1920s, the new CG&E had to address electrical nightmares left behind by shoddy workmanship. A 1922 report by the Chamber of Commerce blamed several fires on unsafe wiring installed by incompetent electricians:

“Combination gas and electric fixtures were hung without insulating joints, wires were in contact with gas pipes, fuses were strapped and too large to be of any value, bell wires and flexible cords were stapled to the woodwork and strung through cellars and across floors, sometimes in contact with pipes.”

Somehow, Cincinnati survived until building codes caught up with the emerging technology. The future was clearly electric and even Procter & Gamble resigned to the inevitable and ceased making candles in the 1920s.

As for St. Xavier Church, the Cincinnati Post [31 January 1898] gave the new electric lights a good review:

“The altar when lighted up is an imposing spectacle.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Louis Krevel - Carl Friedrich Stumm (ab. 1836) and Marie Louise Stumm, née Böcking (1835)

(Saarland Museum)

372 notes

·

View notes

Photo

ab. 1856 Louis Krevel - Emil Albano Korte with his family

(Private collection via AnticStore)

177 notes

·

View notes

Photo

1840 Louis Krevel - Children of the Kraemer family

(Stadtmuseum Simeonstift Trier)

61 notes

·

View notes