#Svend Grundtvig

Text

Valravnen is less of a vættr and more of a fairytale creature. It's only known from medieval folk songs, and only from Denmark.

Valravnen shows up in two folk songs: The appropriately titled "Valravnen" and a version of "Germand Gladensvend," where Gammen is replaced by Valravnen. In the self-titled song, valravnen is a human who has been cursed to become a bird (sometimes a raven, sometimes an eagle) and is only returned to his human body when he drinks the blood of a baby. In Germand Gladensvend, valravnen is a monstrous bird who helps the main characters, but asks for their first-born in return, whom he then eats - he is, however, killed by the child's mother before it is revealed why he ate the child.

Even in the song commonly known as "Valravnen," this word only shows up in two of the nine versions of the song. In the other versions, the character is referred to as Wild Raven, Salmand Raven, or Verner Raven (Salmand and Verner being human names).

According to folklorists Holbek & Piø, "valravn" (battlefield raven) is not the original name for this figure, but is instead a misunderstanding of the more prevalent name "vilde ravn" (wild raven), as the figure never appears to have had anything to do with the battlefield, and "wild raven" is a far more common moniker in medieval sources.

However, during the early-1800s nationalistic romanticist wave, poet Adam Oehlenschläger showed a clear preference for the name "valravn" and chose to exclusively use that name in his reworkings of the folksongs. By the time folklorist Svend Grundtvig started his work, by the mid-1800s, "valravn" had overtaken the earlier "vilde ravn" name in popularity.

It is Holbek & Piø's opinion that valravnen is closely related to the werewolf, since they're both transformed humans who can be freed by drinking the blood of an infant, a belief that seems exclusive to Southern Scandinavia.

According to some modern authors, valravnen is a raven that haunts the battlefield, but I have not been able to trace back the origins of this belief. It seems fairly recent, and appears to be a result of the creature's name, more than its actual folkloric presence.

The heraldic combination of a wolf and a raven has been referred to as a valravn. This has seemingly nothing to do with the folkloric valravn, just as a heraldic antelope has nothing to do with a real life antelope. It does lend some credence to the idea that the valravn and the werewolf are related, though. The werewolf is also rarely described as "varulv" in folk songs, but is more often described as "vilde ulv" (wild wolf) or "grå ulv" (grey wolf).

Sources:

Holbek & Piø (1967) "Fabeldyr og Sagnfolk"

Poul Lorenzen (1960) "Vilde Fugle i Sagn og Tro"

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

🗣️

🗣️Talk about your favourite WIP

thank you for the ask omgg!!

So - The Monster and the Butterfly will forever be a favorite WIP, my fav brain child.🥺

but as of right now, in terms of projects I'm actively working on, Temperance & Mr. Wyrm has become a swift favorite!! Like... I'm not sure what to TALK about with this WIP that I haven't already said, but something I'm so excited to explore in terms of theme is related to this one quote from the Prince Lindworm fairytale:

“The Lindworm said again to her, ‘Fair maiden, shed a shift.’

The shepherd’s daughter answered him, ‘Prince Lindworm, slough a skin.’”

-Prince Lindworm by Svend Grundtvig.

shedding skins to become someone (or something) new is a huge theme in TAMW! Like... literally and metaphorically! Jack DOES undergo a physical change, but both he and Temp grow as people and they learn lessons! They're shedding parts of themselves to become new people! And GRRGRGRRRRrRRRRRRR I WANNA EXPLORE THIS MOREEEEE!!!!!

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danish folklore lovers: please help!

Does anyone have access to this book:

Folkeeventyr fra Kær herred (Folk tales from Kær Herred), by Nikolaj Christensen, published by Laurits Bødker with Akademisk forlag; København

1963-67.

As far as I can tell, it is the most complete publication of the folk tales that Nikolaj Christensen collected and sent to folklorist Svend Grundtvig. And the index even promises to have an English summary at the back!

Apart from the index I can find nothing of it online though, and I’m currently on a wild goose chase for an alternative version of the story “David Husmandssøn” (as collected by Jens Kamp) and I’m hoping it’s in here. Perhaps “Matrosen og kongen” (The sailor and the king) or “Et sømandsæventyr” (A seaman’s adventure)?

If you can help me, please let me know, I’ll be forever grateful!

EDIT: Several kind Danish folks are investigating their local libraries for me, so stay tuned!

EDIT 2: Quest completed! The Danish corner of my dash very kindly dove into research for me and confirmed that Et sømandsæventyr is indeed a version of David Husmandssøn (or vice versa)!

#my dash is always full of wisdom so I'm hoping this will work!#I want to have a look at that english summary so bad#Nikolaj Christensen#Laurits Bødker#Folkeeventyr fra Kær herred#danish folklore#danish fairy tale#danish folk tale#scandinavian folklore#danish folktale#laura researches

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

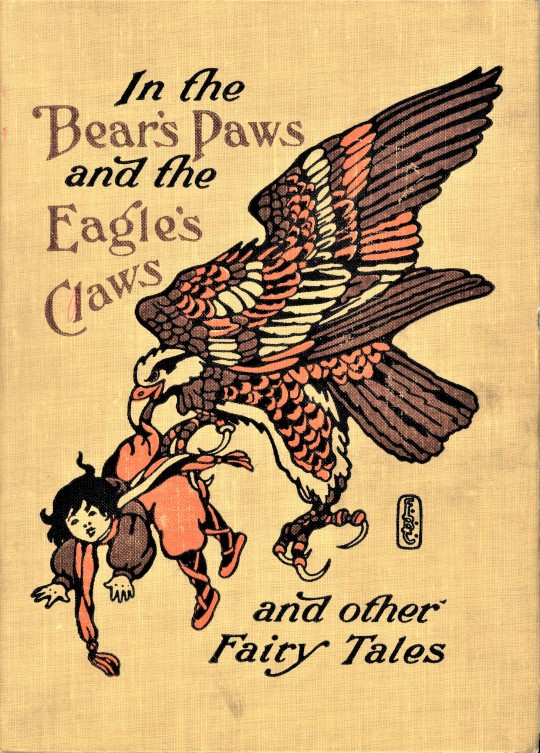

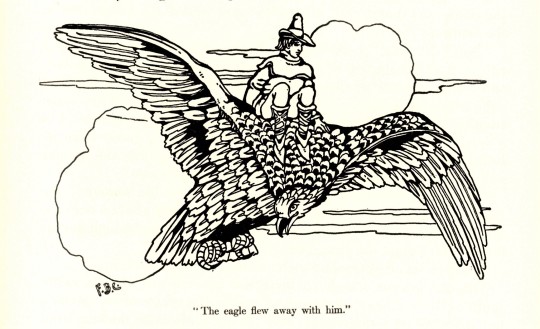

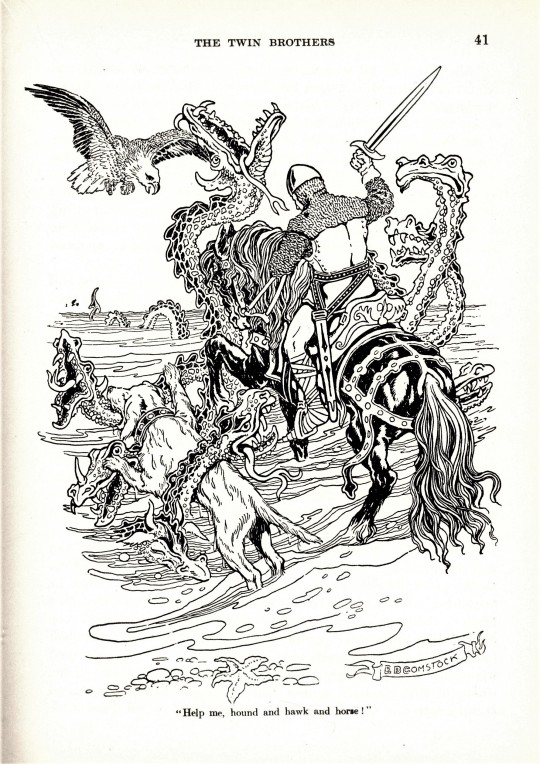

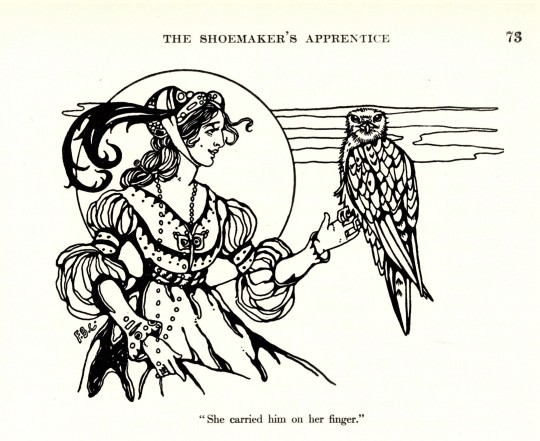

A Danish Fairy Tale Feathursday

Birds play significant roles in many to the Danish folk tales collected by Danish literary historian and ethnographer Svend Grundtvig. To demonstrate, we present a few illustrations from an English translation in our Historical Curriculum Collection of several tales collected by Grundtvig, In the Bear's Paws and the Eagle's Claws and Other Fairy Tales (Grundtvig is cited here as Ivend Grundtvig), with illustrations by the Milwaukee-born artist E. B. Comstock, published in New York by McLoughlin Brothers in 1909. The birds include hawks, eagles, owls, and doves. These bold birds help the heroes and thwart the bad guys! Now, these are our kind of birds!

View more Feathursday posts.

#Feathursday#Svend Grundtvig#fairy tales#folktales#Danish folktales#In the Bear's Paws and the Eagle's Claws#E. B. Comstock#Enos Benjamin Comstock#McLoughlin Brothers#Historical Curriculum Collection#illustrated books#children's books#birds#birbs!

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

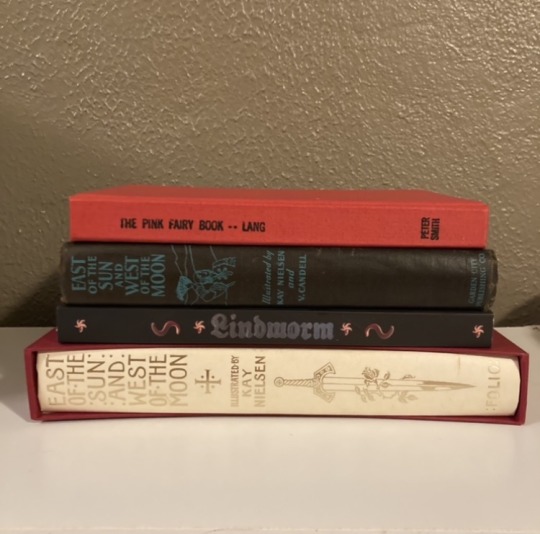

Every retelling of a Scandinavian folk tale I own, including - and this is key - *mine*! Preorder at https://www.waxheartpress.com/product-page/lindworm

#lindworm #waxheartpress #comingsoon #books #newrelease #indiepress #smallpress #writing #publishing #fantasy #folklore #fairytales #fairytaleretelling #scandinavianfolklore #princelindworm #eastofthesunandwestofthemoon

#writing#fairy tales#books#my writing#folklore#publishing#fairy tale retellings#prince lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#east of the sun and west of the moon#gamle dansk minder i folkemunde#svend grundtvig#asbjornsen and moe#edith pattou#sarah beth durst

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Spell of Gróa

>> "Groa's Incantation" by W. G. Collingwood

Gróagaldr or The Spell of Gróa is the first of two poems, now commonly published under the title Svipdagsmál found in several 17th-century paper manuscripts with Fjölsvinnsmál. In at least three of these manuscripts, the poems are in reverse order and separated by a third eddic poem titled, Hyndluljóð.

For a long time, the connection between the two poems was not realized, until in 1854 Svend Grundtvig pointed out a connection between the story told in Gróagaldr and the first part of the medieval Scandinavian ballad of Ungen Sveidal/Herr Svedendal/Hertig Silfverdal (TSBA 45, DgF 70, SMB 18, NMB 22).

Then in 1856, Sophus Bugge noticed that the last part of the ballad corresponded to Fjölsvinnsmál. Bugge wrote about this connection in Forhandlinger i Videnskabs-Selskabet i Christiania 1860, calling the two poems together Svipdagsmál. Subsequent scholars have accepted this title.

Gróagaldr is one of six eddic poems involving necromantic practice. It details Svipdag's raising of his mother Groa, a völva, from the dead. Before her death, she requested him to do so if he ever required her help; the prescience of the völva is illustrated in this respect. The purpose of this necromancy was that she could assist her son in a task set him by his cunning stepmother. Svipdag's mother, Gróa, has been identified as the same völva who chanted a piece of Hrungnir's hone from Thor's head after their duel, as detailed in Snorri Sturluson's Prose Edda.

There, Gróa is the wife of Aurvandil, a man Thor rescues from certain death on his way home from Jötunheim. The news of her husband's fate makes Gróa so happy, she forgets the charm, leaving the hone firmly lodged in Thor's forehead.

In the first stanza of this poem Svipdag speaks and bids his mother to arise from beyond the grave, at her burial mound, as she had bidden him do in life. The second stanza contains her response, in which she asks Svipdag why he has awakened her from death.

He responds by telling her of the task he has been set by his stepmother, i.e. to win the hand of Menglöð. He is all too aware of the difficulty of this: he presages this difficulty by stating that:

"she bade me travel to a placewhere travel one cannotto meet with fair Menglöð"

His dead mother agrees with him that he faces a long and difficult journey but does not attempt to dissuade him from it.

Svipdag then requests his mother to cast spells for his protection.

Groa then casts nine spells, or incantations.

~~~

#The Spell of Gróa#gróa#mythology#norse mythology#illustration#bw#nine spells#Groa's Incantation#W. G. Collingwood#Gróagaldr#Svipdagsmál

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

"An afternoon in May on Vestergade in Ærøskøbing, 1918". Peter Tom-Petersen.

Danish . 1861 - 1926.

Peter Tom-Petersen was a Danish painter and graphic artist, known primarily for cityscapes, interiors and other architectural paintings. His name was Peter Thomsen Petersen until 1920, when he had it legally changed to match his signature: "Tom P."

His father was a pharmacist. He attended grammar school in Maribo until 1876. The following year, he was enrolled at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, which he attended until 1881. His principle Professor there was C.V. Nielsen (da), who was primarily an architect and no doubt influenced his later choice of subject matter. After that, he studied at the Kunstnernes Frie Studieskoler and, from 1883 to 1884, worked with Léon Bonnat in Paris.

In 1889, he was awarded Honorable Mention at the Exposition Universelle. In 1891, he was married and, in 1892, received a travel stipend from the Academy, which allowed him to spend a year in Italy.

In 1900, already known for his landscapes and cityscapes, he decided to devote himself to creating illustrations; eventually producing more than 300 for magazines in Denmark and Germany; notably the Illustreret Tidende.[2] He began with old buildings and picturesque idylls, followed by colorful cities in Germany (such as Rothenburg ob der Tauber), Danish market towns and old neighborhoods in Copenhagen. They proved to be very popular and many are now of significant historical value.

In addition to his work for magazines, he illustrated Danish Folk Tales by Svend Grundtvig, The Fidget by Ludvig Holberg, Denmark in descriptions and photos of Danish Writers and Artists by Martinus Galschiøt (da) and The Story of a Bad Boy by the American writer, Thomas Bailey Aldrich.

In 1909, he was one of the co-founders of the "Graphic Artists' Society" and served on its governing board until 1911. In 1910, he was one of the organizers of the Faaborg Museum (da) and sat on its board until his death. From 1910 to 1915, he was also a member of the "Censorship Commission" for the Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition. In 1914, he was on the jury at the Baltic Exhibition

Source: Wikipedia".

> Christa Zaat > Painters from the North

1 note

·

View note

Text

2 days ago I:

Packed one more box

Put 7 boxes and most of my plants in my mom's car and sent her home. My room is looking sparser by the minute

Cleaned 2 terrariums

Moved my isopods and roaches to a plastic container so they'll be easier to transport

Cleaned my bathroom

Groceries

Failed to abstain from Runescape

Categorized a few bits of folklore

Yesterday I:

Took my meds

Met up with my partner

Went to a café with them and tried to figure out our plans for the near future

Went to the cinema and finally watched The Boy and the Heron

Talked to my mom on the phone

Went to Frederiksberg Have to look at the elephants but they weren't out :/

Went to Frederiksberg Ældre Kirkegård to pay my respects to Svend Grundtvig

Said goodbye to my partner bc they had a train o catch :(((

Went to Assistens Kirkegård to pay my respects to Just Mathias Thiele

Bought a dürüm

Played runescape for an hour or so

Today I:

Packed 6 boxes

Met with my mom who picked up those 6 boxes + the last of my plants + my boardgames

Cleaned the pig blankets so they're nice and fresh tomorrow

Groceries

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lindworm Promo Series Repost: Cite Your Sources

*This is a repost from 9/17/17*

I first read Prince Lindworm in a collection of Scandinavian fairy tales illustrated by Kay Nielsen, who, by the way, is awesome. The problem here is that it was a later edition of the book. At some point, I don’t remember why, I got super into finding out the history of Prince Lindworm. See, it was in this book, which was supposed to be stories from Asbjornsen and Moe. Those are the big Norwegian fairy tale dudes, for those of you who don’t know.

But I’m a little obsessive about my fairy tales. You may have noticed. And this book wasn’t even mine. It belonged to my grandparents. So of course I had my own Asbjornsen and Moe anthology. Or two. Maybe three. And I kind of kept buying these books because I wanted my own copy of this one wacky story. But it wasn’t there. So I googled the complete works of Asbjornsen and Moe. It wasn’t there.

I took advantage of my university’s interlibrary loan system to request every single book in the country that mentioned lindworms. Or lindorms. Or lindwyrms, or a variety of other spellings.

Have I mentioned that I’m a little obsessive about my fairy tales?

Several other books and authors and random people on the internet attributed the story to Asbjornsen and Moe. Who definitely didn’t record it. The reason for this, as far as I can tell? This book my grandparents had, really nice hardcover, fancy publisher, gorgeous illustrations—it was kind of a big deal. All sorts of people had read the story in this book, and only this book, and assumed the information provided was reliable.

And here’s where the publishers went wrong. There’s an editor’s note in the front. It explains that all but two of the stories in the volume are from one particular translation of the works of Asbjorsen and Moe. What they apparently neglected to mention is that one of those two stories was not only from a different translator, but a different source entirely.

So Prince Lindworm didn’t come from Norway. That’s settled. And, okay, I don’t know what to tell you about the one random outlier in my interlibrary loan adventure that said the story was from Sweden, but I’ve got this worked out.

Really, it could have been worse. When I wanted to read the earliest recorded version of Beauty and the Beast, and I couldn’t track down a translation anywhere, I spent months tearing the internet apart before I found a copy that was clearly printed well over one hundred years ago, given the spelling and lettering, in French, scanned in and saved as a pdf. I still have that saved on my computer somewhere. Given that I don’t know any French, dictionaries only provided modern spellings, and any given character could easily have been three to six different letters in that typeface, the several months I spent attempting to translate didn’t really get me anywhere. I don’t think I even translated the first paragraph successfully.

I did a little better with Prince Lindworm. It still took me a couple months to find the text, and it was still a crappy pdf with outdated spelling. Plus it was in Danish. But the lettering was slightly more modern, and I happen to be much better at slogging my way through Danish than French. A little bit of Norwegian, a little bit of Anglo-Saxon, a tiny bit of German. It’ll get you places. Sadly, my extensive background in Latin was utterly useless to French. (And Spanish. It seems my teachers lied to me. I strongly suspect Romani and Portuguese would also be a bust, but at least I can stumble blindly through basic Italian.)

It was, when I found it, three or four pages of a quite large collection. I haven’t gotten into the rest of it yet—soon, hopefully. Gamle dansk Minder i folkemunde, it’s called. I’m good at general ideas in Germanic languages, not so much actual translations, so bear with me here, but I’m going to tentatively call this “Old Danish Memories from the Mouths of the People.” Sounds better in Danish, right? This is why I keep my translations to myself.

The compiler of this book is listed as Svend Grundtvig, and he’s generally known for collecting Danish folk songs, but as far as I can tell, in my admittedly spotty Danish comprehension, there’s no music for this one.

And, okay, I know I talk a lot about how stories, especially folk stories, don’t belong to anyone, because they’re so mutable, because a story is really a community, a conversation. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to know where the conversation started.

For crying out loud, people, cite your sources! I dedicated months of my life to this. Do you have any idea how many utterly worthless books I had to read in search of some tiny hint of origins? How many incorrect attributions I had to read? How much respect I lost for researchers in this field in general?

Look, sometimes tracking down crap pdfs of source material can be fun, okay? I love pulling random linguistic data from obscure folklore and stuff like that. But really. Really. How hard can it possibly be to say, “hey, this historically and culturally significant story that I’m making a profit on because it’s been in the public domain for a hundred years originally came from Denmark”?

There is no excuse not to give fairy tales the correct attribution. Like, anthology and picture book based fairy tales have got to be the easiest writing to make a profit on. The story has been marinating in your brain forever, right? Do you even remember a time before you knew Cinderella? Just tell it in your own words, and someone else will come along and slap some beautiful illustrations on, and you’re good to go. It costs five minutes and zero dollars to add in a little note saying, “This adaptation was inspired by the French version of the story as recorded by Charles Perrault.”

But no, that’s too much work for you. Instead you’ll just go and publish a wildly popular book that heavily implies incorrect information, and let it spin wildly out of control until poor innocent college kids are staying up all night on the internet reading languages they don’t understand and enlisting the help of just about every library in the continental United States.

Ugh.

Anyway, Grundtvig is a really awesome dude who absolutely knows how to cite his stories. Kong Lindorm was told in 1854 by Maren Mathisdatter, age 67, in Fureby. It was recorded by Adjunct A. Levisen.

See? Was that so hard?

#lindworm#prince lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#kong lindorm#folklore#fairy tales#svend grundtvig#asbjornsen and moe

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

All books currently in my possession that have English translations of the fairy tale “King Lindorm.” You can buy mine at at https://www.waxheartpress.com/product-page/lindworm

#lindworm #waxheartpress #comingsoon #books #newrelease #indiepress #smallpress #writing #publishing #fantasy #folklore #fairytales #fairytaleretelling

#writing#fairy tales#books#folklore#publishing#translations#Andrew Lang#svend grundtvig#Lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#prince Lindworm#east of the sun and west of the moon#the pink fairy book#gamle dansk minder i folkemunde

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Missing Half

So if you’ve been around for a while, you’ve probably heard me talking about Prince Lindworm, and not just recently, as I prepare to release my book. I’ve been obsessed with this story for a long time, I’ve written several blog posts and essays about it, and it’s even the source of my username on many websites—konglindorm.

But today, I’m going to talk about something new: the second half of the story.

I honestly didn’t know until very recently that this story did not end with the lindworm being transformed and everyone living happily ever after. I’ve been working for a long time on my own translation of the story, from a 100+ year old Danish book, and last month I finally reached the end of it.

And then saw that there were three more pages.

Now, I’m preparing to publish my first novel, and I don’t have the time or the energy to translate another three pages. But I did a quick read-through, enough to get the basic idea, and I did some more research. Then I ran it through Google translate, which produced something that’s…pretty rough, but it’s useful to having something in English to glance back at as I work on this post.

So it’s not relevant to my retelling at all, and it’s actually a really common fairy tale type that I’ve encountered many times before, but I’m really excited about this. Quick recap, before we start: Barren queen wants baby. Queen is instructed to eat one flower if she wants a son, another if she wants a daughter, but not, under any circumstances, both. Queen eats both. Queen gives birth to lindworm. Lindworm eventually demands bride. Eats her. Demands second bride. Eats her. Demands third bride, third bride does some really weird stuff that somehow turns him into a human. Great rejoicing, etc., etc.

Now on to part two. I’m gonna be honest; some really weird stuff happens here. Which shouldn’t be surprising, coming from the same fairy tale that brought us “To turn a snake into a man, make him molt ten times, dip some whips in lye, whip him a bunch, and dunk him in a tub of milk.” My understanding of the story is hindered somewhat by lack of a complete and accurate English translation, but it looks like at some point our girl helps break the spells on two other enchanted princes by feeding them her breast milk? It’s, um. It’s something, and something I’ll need to fully translate eventually to understand better. I think I’m missing a fair amount of context and nuance.

(Between the two halves, I ‘m thinking I need to do a lot of research on the healing properties of milk in folklore. Is that a thing? Does it come up elsewhere? This story is Danish; anyone from Denmark know if there’s some cultural element to this or something?)

But for now we’re going to focus on the main thing, the basic plot of the second half.

Our girl gets pregnant. Lindworm and his dad go off to war, leaving pregnant girl with Lindworm’s mother the queen. Now, normally, that would cause some trouble in the fairy tale world, because usually, old queens are not fond of their daughters-in-law, and often try to frame them for horrible crimes.

But not our queen. She gave birth to a monster. Her only heir was a dragon, and he was eating people. Then our girl came along and turned him into an upstanding member of human society. This queen loves her daughter-in-law. So we need a different bad guy.

Our girl gives birth to twins. She sends a letter to the lindworm, letting him know. Normally, in this story type, the queen swaps it out with a letter saying she gave birth to something else, but not our queen, so that role is filled by the Red Knight. No information on who this dude is, what he has against our characters, or why it’s his job to run letters back and forth between the palace and the war zone.

He gets rid of the letter saying our girl had twins, replaces it with a letter saying she had puppies. Lindworm gets the letter, thinks, “well, that’s super weird, but who am I to judge, my mom didn’t give birth to a human either.” Sends back a letter saying, “Okay, we’ll sort that all out when I get home.”

Red Knight was apparently hoping for a less go-with-the-flow type answer, because he replaces that letter with one telling the queen to set our girl and her babies on fire.

The queen gets the letter, and I guess she’s probably thinking that maybe the transformation didn’t quite work after all, maybe her son still has some monster in him, because what the heck, dude? I’m not burning my grandbabies.

So she doesn’t know when the lindworm is coming home, and she’s afraid of what he’ll do to his family when he does; she sets our girl up with some supplies and sends her and the babies out into the world where they’ll be safe.

(This is when she turns a couple birds into princes by nursing them, and apparently hangs out with them in their palace for quite some time. Not clear on the nature of their relationships, a little concerned, will update you guys someday when I’ve sorted it all out; if anyone’s read this entire story in Danish and fully understands it, or if you’ve encountered a complete English translation, please do let me know!)

Lindworm comes home, looking for his wife. Queen is pissed at her son. Son isn’t sure what she’s so upset about; he thought he was pretty chill about the whole gave-birth-to-puppies thing. Queen isn’t sure what puppies have to do with anything, but setting your family on fire is in no way chill. They argue for a while, eventually get to the bottom of things, Red Knight is in big, big trouble. Lindworm goes looking for his wife and kids. Eventually finds them hanging out with these two other princes.

This is where Google translate really breaks down on me, and things just make less and less sense, and I can’t go down to the source material with my Danish-English dictionary and sort it out right now; I’m on a bit of a tight schedule. But it’s looking like the Lindworm and the two other princes sort of fight over our girl, all three of them drink her milk (it seems like it’s been long enough that she shouldn’t be producing milk anymore; it also seems like these two dudes are drinking her milk regularly? I am so concerned about so many things.)

Somehow the conflict is resolved, the other two princes marry other princesses, and our girl and the twins go home with the lindworm.

Now, there’s a lot to unpack here, obviously, and a lot of it is going to have to wait until another time. It is nice to know that King Lindorm is consistently just absolutely bizarre through both halves.

But what I really, really like about the second half is that some new dude is our bad guy, and the queen is fully and firmly on our heroine’s side.

Before I made any effort at even the crappiest translation of the second half, I did some research on what it was about. And I was so concerned about it as soon as I found out what story type it was, because some sort of mother figure is almost always the bad guy. (Shout out to the Grimms for not doing that in “The Girl Without Hands,” too.) And it just seemed really awful that the queen would turn around and try to sabotage our girl after she fixed the lindworm. So I was really relieved to find the Red Knight in my first quick skim-through.

I’m just really impressed with Grundtvig, Adjunct Levisen, and Maren Mathisdatter for deviating from the norm here.

(Another notable deviation, aside from “The Girl Without Hands,” listed above, is the French fairy tale “Bearskin,” by Marie-Madeleine de Lubert; I doubt it’s a coincidence that women were definitely involved in the telling/recording of 2 of these 3 stories where people are not out to get their daughters-in-law.)

Also, like. Can we just take a moment to appreciate the incredible stupidity of the Red Knight? The lindworm was born as a giant snake monster, and for some reason Red thinks he’ll be shocked and horrified that his children were born as puppies? The lindworm is pretty much the only person in the world who has no right to be upset by that. He, of all people, should know that these things just happen sometimes, and they’re totally fixable, though not, perhaps, without bloodshed.

(Also, also. As I said above, I don’t know who the Red Knight is or what he has against our characters. It’s possible that the text does tell us and it just didn’t come across in my incredibly quick and crappy translation. But my theory is that he’s somehow connected to one of our two dead and eaten princesses. In which case he’s entitled to be upset, even if he’s handling it poorly.)

Preorder my book here!

#lindworm#prince lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#kong lindorm#folklore#fairy tales#svend grundtvig

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Lindworm: Version Comparison

Over the years, I have managed to find three different versions of King Lindorm—the one that appears in Svend Grundtvig’s Gamle Dansk Minder i Folkemunde, the one that appears in Andrew Lang’s Pink Fairy Book, and the one that appears in the Folio Society’s East of the Sun and West of the Moon. (There is no indication of where this story came from originally or who translated it, so we’re just going to call it the Folio version here.)

I’ve talked a lot before about the origins of this story; the earliest version, Grundtvig’s, is from Denmark. The Folio Society attributes theirs to Asbjørnsen and Moe, in Norway, which we know is incorrect as it doesn’t appear in any other edition of their work. Lang attributes his version to Sweden.

So today, we’re just going to work our way through the three versions and compare/contrast.

They all start the same way. Queen wants baby, queen can’t have baby, old woman tells her how to make it happen. Lang’s version deviates most from the others in the beginning. In the other two versions, the queen encounters the old woman while out on a walk; in Lang’s, the old woman comes to the palace and seeks out the queen specifically to impart her wisdom.

In both Gruntvig’s version and the Folio version, the queen is to eat only one of two differently-colored roses that will grow up overnight under a two-handled cup left in the garden. Very specific, perfectly identical. The lindworm comes because the queen eats both roses.

In Lang’s version, the queen is to take a bath in her room. Two red onions will appear under the bathtub afterwards, and she is to peel and eat both. Her mistake is that she eats the onions without peeling them. (Note that in this version the queen is not given the option to choose the gender of her child.)

Another little deviation in Lang’s version is that the queen apparently doesn’t know she’s given birth to a lindworm? Her waiting woman tosses the lindworm out of the window as soon as it’s born, and the queen doesn’t notice it at all.

Lang and Folio both feature a normal, human prince born after the lindworm. In Gruntvig’s version the lindworm is an only child. Since Gruntvig’s version has no siblings, he approaches the king directly to ask for a bride. In the other two, he waits until the prince goes out to find a bride, and then goes up to him and says, “Hey, I’m your secret brother, and since I’m older, I get to get married first.”

Here, again, Lang’s version deviates significantly. The other lindworms both marry (and eat) two foreign princesses, then a local shepherd’s daughter selected by the king. Lang’s lindworm marries and then eats an unspecified number of slave women before a wicked stepmother offers up her stepdaughter as a bride. Specifically, she tells the king that her stepdaughter would like to marry the lindworm, and the king apparently doesn’t question this? He for some reason finds it believable that a young woman would volunteer to marry a monster who’s already eaten multiple previous wives, without asking for any kind of compensation for her family or anything?

And, okay, Lang is going full German-Cinderella here. After the stepmom screws her over, girl goes to her mom’s grave, where she’s given three nuts. This is what happens in the place of her meeting an old woman and getting instructions in the other two versions.

Lang’s main girl goes through similar basic wedding prep steps to the others, with no indication of where she got the idea from; while the other girls have a tub of lye, tub of milk, whips, and ten gowns/shifts, Lang’s girl has the tube of lye, only seven shifts, and three scrubbing brushes. After they go through the whole take-off-your-shift-take-off-your-skin situation, Lang’s girl just, like, scrubs all the lindworm-iness out of him? She just scrubs until he turns into a dude.

The other two versions, of course, have the much more complex and disgusting transformation sequence of dip whips in lye, whip lindworm, dunk lindworm in milk, take lindworm to the bed, embrace.

The Folio version ends immediately after this, with the girl and the transformed prince living happily ever after. The other two stories continue.

In the second half of Lang’s version, the old king dies, the lindworm becomes king, the lindworm goes to fight in a war, and the girl’s stepmother steals a bunch of letters and tells a bunch of lies that result in the girl and her two young sons fleeing the palace until the lindworm comes to find them. During this time, the girl uses her magic nuts to save a man named Peter.

In the second half of Gruntvig’s version, the old king and the lindworm both go off to war, it’s a character called the Red Knight who switches the letters, and while she and the babies are away, our girl somehow uses her breast milk to help two other men who’ve been transformed into animals? IDK, I don’t have a full English translation yet, but what we do have to work with is seriously weird.

Lang’s version definitely deviates significantly from the others; it has no points in common with Grundtvig’s aside from the most basic plot—barren queen, ignoring food instructions=lindworm, brides eaten, transformation involving shedding/undressing and lye, heroine flees into the woods with children due to mail-tampering, saves someone else before reunion with lindworm.

The Folio version deviates from Grundtvig’s only in that it ends halfway through and includes a second prince.

Today is the first time I’ve read through Lang’s version in several years, at least, and somehow, despite its differences from the others, it feels the least unique? I was definitely first drawn to “Prince Lindworm,” as a child, because despite falling into my much-beloved Enchanted Bridegroom category, it felt very different from any other story I’d read. The beast as a snake-like creature, the brides being eaten, the unsettling transformation sequence—it was all just great. This was the Folio version, that I was reading as a child. But when I first encountered the second half of the story in Grundtvig’s version, it was also delightfully unique and bizarre, even if I can’t fully understand it. The lindworm’s mother—the girl’s mother-in-law, often a villainous figure—is 100% on her side, and the main person to try to help her through what happens next. And the milk situation is just—well, it’s something.

Lang’s version, despite being the same basic story, just feels bland and unoriginal. There’s an evil stepmother, which is just, sort of cliché, you know? The transformation sequence has been cut down and seriously sanitized. And then the situation where he marries an unspecified number of slave women in the place of two princesses—well, I have a number of issues with that.

Firstly, the number three is so often symbolic in fairy tales, and to replace the three total marriages with an unspecified number is lame, but that’s a dumb, nitpicky issue. The marriages to slave women indicate that this is a country that holds slaves, which I don’t love. But my big issue with this is that a significant part of the charm of the other versions is just the absolute, idiotic absurdity of marrying your monster son to a second princess after he eats the first. Like, you know what’s going to happen now—the same thing that happened last time. He’s gonna eat the princess and another powerful king is going to be rightfully angry with you. Marrying him instead to someone who won’t be missed lowers the stakes and raises the rationality in a way that bores me, and also implies that some potential brides are worth less? Like, with the first couple brides as princesses, we know they matter even though we never properly meet them, because their deaths put the threat of war over our heads—which is probably why the king and the lindworm go off to war shortly after the spell is broken in Grundtvig’s version. “A whole bunch of random slave girls died with no consequences and then we met our main character” just seems sort of…cheap.

So! While I did enjoy reading Lang’s version, I don’t think I would have fallen in love with this story if it was the first I encountered. I think the other versions are both more absurd and more meaningful.

Preorder my book based on this story here!

#lindworm#prince lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm#folklore#fairy tales#fairy tale analysis#svend grundtvig#Andrew Lang

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Preorder at https://www.waxheartpress.com/product-page/lindworm

#lindworm #waxheartpress #comingsoon #books #newrelease #indiepress #smallpress #writing #publishing #fantasy #folklore #fairytales #fairytaleretelling

#writing#fairy tales#books#folklore#publishing#translation#denmark#svend grundtvig#gamle dansk minder I folkemunde#my book#Lindworm#king lindorm#kong lindorm

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Danish folklore has a ton of different dragons, but this one from “Sagn og Gode Historier fra Det Sydlige Sjælland” by Svend C. Dahl has got to be one of my favorites, just because of how unique it is:

Usually dragons are thought of as great and ferocious. The dragon from this story was rather small and had outwardly human-like traits, but was still referred to as “the mean dragon,” perhaps because it “guarded a treasure”. What the treasure was is not mentioned.

An elderly woman told, in the middle of the 1800s, that when she was a kid, she once walked across Brandelev Field with some other kids when they spotted a figure lying next to a small hill. It resembled a naked human, except it glowed like embers.

The kids got scared and ran away, but when she returned home, her father scolded her and called her a fool. If she had been braver she could have snuck up on the dragon and stabbed him with her knife, then she would’ve been able to take all his treasure. For what she had seen was the dragon who rarely lets himself be seen, and who for once had laid outside his hill, dozing in the sunlight.

Originally collected in Carlsen 1861, book 15, & Grundtvig 1854-61, book 3

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

http://konglindorm.blogspot.com/2021/03/prince-lindworm-version-comparison.html?m=1

#writing#fairy tales#my writing#folklore#fairy tale analysis#Lindworm#prince Lindworm#king lindworm#king lindorm

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

I first read Prince Lindworm in a collection of Scandinavian fairy tales illustrated by Kay Nielsen, who, by the way, is awesome. The problem here is that it was a later edition of the book. At some point, I don’t remember why, I got super into finding out the history of Prince Lindworm. See, it was in this book, which was supposed to be stories from Asbjornsen and Moe. Those are the big Norwegian fairy tale dudes, for those of you who don’t know.

But I’m a little obsessive about my fairy tales. You may have noticed. And this book wasn’t even mine. It belonged to my grandparents. So of course I had my own Asbjornsen and Moe anthology. Or two. Maybe three. And I kind of kept buying these books because I wanted my own copy of this one wacky story. But it wasn’t there. So I googled the complete works of Asbjornsen and Moe. It wasn’t there.

I took advantage of my university’s interlibrary loan system to request every single book in the country that mentioned lindworms. Or lindorms. Or lindwyrms, or a variety of other spellings.

Have I mentioned that I’m a little obsessive about my fairy tales?

Several other books and authors and random people on the internet attributed the story to Asbjornsen and Moe. Who definitely didn’t record it. The reason for this, as far as I can tell? This book my grandparents had, really nice hardcover, fancy publisher, gorgeous illustrations—it was kind of a big deal. All sorts of people had read the story in this book, and only this book, and assumed the information provided was reliable.

And here’s where the publishers went wrong. There’s an editor’s note in the front. It explains that all but two of the stories in the volume are from one particular translation of the works of Asbjorsen and Moe. What they apparently neglected to mention is that one of those two stories was not only from a different translator, but a different source entirely.

So Prince Lindworm didn’t come from Norway. That’s settled. And, okay, I don’t know what to tell you about the one random outlier in my interlibrary loan adventure that said the story was from Sweden, but I’ve got this worked out.

Really, it could have been worse. When I wanted to read the earliest recorded version of Beauty and the Beast, and I couldn’t track down a translation anywhere, I spent months tearing the internet apart before I found a copy that was clearly printed well over one hundred years ago, given the spelling and lettering, in French, scanned in and saved as a pdf. I still have that saved on my computer somewhere. Given that I don’t know any French, dictionaries only provided modern spellings, and any given character could easily have been three to six different letters in that typeface, the several months I spend attempting to translate didn’t really get me anywhere. I don’t think I even translated the first paragraph successfully.

I did a little better with Prince Lindworm. It still took me a couple months to find the text, and it was still a crappy pdf with outdated spelling. Plus it was in Danish. But the lettering was slightly more modern, and I happen to be much better at slogging my way through Danish than French. A little bit of Norwegian, a little bit of Anglo-Saxon, a tiny bit of German. It’ll get you places. Sadly, my extensive background in Latin was utterly useless to French. (And Spanish. It seems my teachers lied to me. I strongly suspect Romani and Portuguese would also be a bust, but at least I can stumble blindly through basic Italian.)

It was, when I found it, three or four pages of a quite large collection. I haven’t gotten into the rest of it yet—soon, hopefully. Gamle dansk Minder i folkemunde, it’s called. I’m good at general ideas in Germanic languages, not so much actual translations, so bear with me here, but I’m going to tentatively call this “Old Danish Memories from the Mouths of the People.” Sounds better it Danish, right? This is why I keep my translations to myself.

The compiler of this book is listed as Svend Grundtvig, and he’s generally known for collecting Danish folk songs, but as far as I can tell, in my admittedly spotty Danish comprehension, there’s no music for this one.

And, okay, I know I talk a lot about how stories, especially folk stories, don’t belong to anyone, because they’re so mutable, because a story is really a community, a conversation. But that doesn’t mean I don’t want to know where the conversation started.

For crying out loud, people, cite your sources! I dedicated months of my life to this. Do you have any idea how many utterly worthless books I had to read in search of some tiny hint of origins? How many incorrect attributions I had to read? How much respect I lost for researchers in this field in general?

Look, sometimes tracking down crap pdfs of source material can be fun, okay? I love pulling random linguistic data from obscure folklore and stuff like that. But really. Really. How hard can it possibly be to say, “hey, this historically and culturally significant story that I’m making a profit on because it’s been in the public domain for a hundred years originally came from Denmark”?

There is no excuse not to give fairy tales the correct attribution. Like, anthology and picture book based fairy tales have got to be the easiest writing to make a profit on. The story has been marinating in your brain forever, right? Do you even remember a time before you knew Cinderella? Just tell it in your own words, and someone else will come along and slap some beautiful illustrations on, and you’re good to go. It costs five minutes and zero dollars to add in a little note saying, “This adaptation was inspired by the French version of the story as recorded by Charles Perrault.”

But no, that’s too much work for you. Instead you’ll just go and publish a wildly popular book that heavily implies incorrect information, and let it spin wildly out of control until poor innocent college kids are staying up all night on the internet reading languages they don’t understand and enlisting the help of just about every library in the continental United States.

Ugh.

Anyway, Grundtvig is a really awesome dude who absolutely knows how to cite his stories. Kong Lindorm was told in 1854 by Maren Mathisdatter, age 67, in Fureby. It was recorded by Adjunct A. Levisen.

See? Was that so hard?

Remember to come and read my version on Patreon next month.

7 notes

·

View notes