#akua njeri

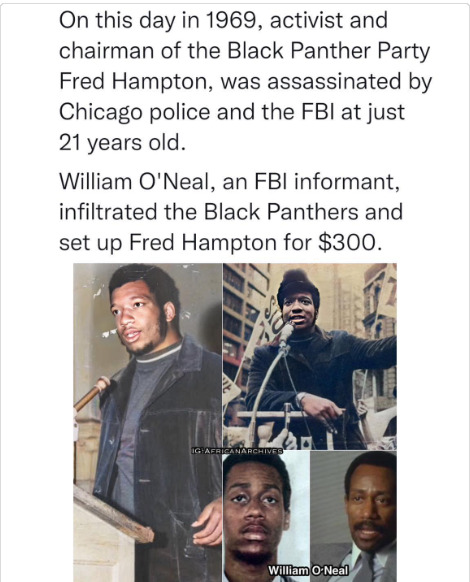

Text

In Illinois, where Fred Hampton was born, the police constantly harassed black people. Access to social goods too was made difficult, if not curtailed, in the areas with heavy black populations.

The party, a creation of Huey Newton and fellow student Bobby Seale, insisted on black nationalist response to racial discrimination. The party’s Illinois chapter was opened in 1967 and Hampton joined in 1968, aged just 20.

when Stokely Carmichael’s Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) split from the Panthers in 1969, Hampton headed the Illinois chapter of the Panthers.

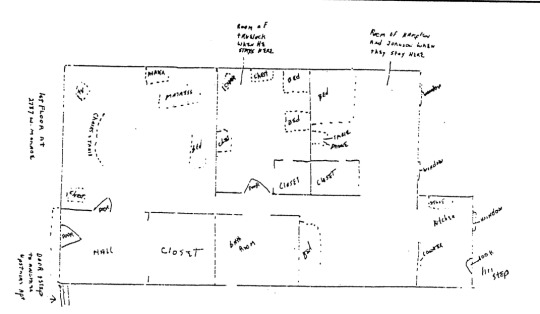

Then a petty criminal, O’Neal was coerced by the FBI into helping them silence Hampton and the Black Panther Party. And he did just that when he infiltrated the party and provided the FBI with a floor plan of the Chicago apartment where Hampton was assassinated in 1969.

His journey to becoming an FBI informant began in 1966 when he was tracked by FBI Agent Roy Martin Mitchell after stealing a car and driving it across state lines to Michigan.

He was told that he would forget about the stolen car charge if he infiltrate the Panthers for the FBI.

The Panther Party had then become infamous for brandishing guns, challenging the authority of police officers, and embracing violence as a necessary by-product of revolution.

O’Neal agreed to infiltrate the party and when he got accepted, he served as the group’s chief of security.

Reports said he even became in charge of security for Hampton and had keys to Panther headquarters and safe houses.

He eventually provided the floor plan of Hampton’s west-side apartment that was used to plan the raid that killed Hampton and his fellow Panther, Mark Clark.

Fred Hampton, was executed in his sleep by race soldiers, sleeping next to his pregnant wife, Akua Njeri.

O’Neal hardly spoke of his undercover years but in a 1984 interview with the Tribune, one of his last public interviews, he mentioned that he “thrived” on his work with law enforcement though in the end, he realized he had been ”just a pawn in a very big game.”

Source: African Archives

61 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 4 December 1969, Chicago Black Panthers Fred Hampton and Mark Clark were killed by police in Chicago. Hampton was murdered while asleep in his bed during a raid on his apartment by Chicago Police in conjunction with the FBI. Hampton had been drugged earlier in the evening by an FBI informant, who also told agents the location of Hampton's bed, where he slept alongside his nine-month pregnant fiancée, Akua Njeri. Several other Panthers were injured. Aged just 21, Hampton was an active, charismatic and effective organiser, who had been making significant inroads into making links with working class whites and building a "Rainbow Coalition" including Puerto Rican, Native American, Chicane, white and Chinese-American radicals. Hampton and Clark were amongst the most prominent victims of the FBI's COINTELPRO program, which amongst other things was directed by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover to "prevent the rise of a Black Messiah". https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.1819457841572691/2152221851629620/?type=3

477 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Video

vimeo

A Revolutionary Act, Part 1 from Troy J. Lewis on Vimeo.

The Black Panther Party did even more than stand up to a violent, racist policing system: they housed, fed, healed, educated, and loved their community unconditionally. The short digital film A REVOLUTIONARY ACT from director @malakaithebrave sets the record straight on the incredible contributions of the Panthers in Chicago — and beyond.

Their legacy lives on in @officialchairmanfredhamptonjr and former Black Panther Akua Njeri, who are working to immortalize the Hampton House, Chairman Fred Hampton’s childhood home, as a landmark and community center in Chicago. Learn more at the link in bio.

—

Production Credits:

Director: @malakaithebrave

Executive Producer: Anna Hashmi

Producer: @jlucky127

Line Producer: @cocoa_butter_gets_the_paper

DP: @aiden_macaroni

Editor: @troyjlewis

Composer: Aaron Shaw

Sound Design + Mix: Greer Vincent Rollier

Graphics/Animation: @mechats @improper.tv

Production Company: @cornershopprods

Brought to you by @participant

0 notes

Photo

Dominique Fishback as Deborah Johnson (now Akua Njeri) in Judas and the Black Messiah (2021)

#Dominique Fishback#Deborah Johnson#Akua Njeri#Judas and the Black Messiah#Judas and the Black Messiah 2021#gifs#film#Daniel Kaluuya#Fred Hampton#chairman Fred Hampton

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in Black Excellence: Akua Njeri—writer, activist and former member of the Illinois Chapter of The Black Panther Party.

“People are still being murdered in the houses, wrong houses, that are so-called 'raided by police’.”

—Akua Njeri

What was Akua Njeri like in her earlier years?

Akua Njeri, known as Deborah Johnson at the time, became an activist at the very young age of twelve. From marching with Martin Luther King, Jr. to protesting slumlords in the city as a teen, Nehru was committed to social causes in Chicago. In the late 1960s, 17-year-old Njeri attended an event sponsored by a Chicago college’s Black Student Union. It was at this event that she met her future fiance Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Black Panther Party, who was murdered on December 4, 1969, during an illegal raid of their home.

What has Njeri been up to?

Njeri has since continued to dedicate her life to the cause. She has served as president of the National People’s Democratic Uhuru Movement, an interracial organization dedicated to self-determination for Black Americans, and as chairperson of the December 4th Committee, which fights to defend and maintain the legacy of the Black Panther Party. In 1991, she published My Life with the Black Panther Party, recounting her experiences, including the deadly raid and its aftermath. She continues her lifelong commitment to serving communities in need, coordinating clothing and fresh vegetable drives.

Original portrait by Tumblr Creatr @princecanti

Akua Njeri's quote from the 50th anniversary of the fateful day in which officers murdered Chairman Fred Hampton is what inspired this piece. As such, I wanted to emphasize that statement by drawing attention to just how true that quote would continue to be into the following year—highlighting the dates of Fred Hampton’s death in 1969 and Breonna Taylor’s in 2020.

—@princecanti

#black excellence#blackexcellence365#akua njeri#support black women#celebrate black women#trust black women#protect black women#today in black excellence#creators#black artist

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

#african/black experience#afrikan#war on afrikans#terrorism#culture#protest#freedom#revolutionary#Black Panther Party#Judas and the Black Messiah#Daniel Kaluuya#Dominique Fishback#Lakeith Stanfield#Mark Clark#Akua Njeri#Fred Hampton Jr#Fred Hampton Sr#Debra Johnson#Hampton House#Black Panther Party for Self Defense#Deacons for Defense

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

‘Akua Njeri w/ Child’ Greeting Card - Makeba Rainey

#Akua Njeri#Deborah Johnson#Fred Hampton#art#digital collage#photography#kiddos#Fred Hampton Jr.#Makeba Rainey

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just finished Judas and the Black Messiah

The FBI really said we don’t want that nigga in jail we want that nigga dead. Despite the fact that Fred Hampton was already headed back to jail (on a bogus charge at that) before his murder, the U.S. government still said oop — that’s not enough. Cointelpro assasintated Fred Hampton in his sleep (after drugging him). Drug his 19 year old 8.5 month pregnant fiancé out of their bedroom and pointed the barrel of their gun at her belly before going into the bedroom where Fred’s sleeping and drugged body laid and fired shots into him at point black range. About 99 shots altogether were fired during that raid. Then they turned around and charged the same men and women who they shot at and shot up with attempted murder. Then after 12 years and a 47 million dollar civil suit they awarded the victims with a little over 1 million to split. And even today, Fred Hampton Jr. has spoken about how local law enforcement have shot up his assasinated father’s tombstone annually. This is reminder that U.S. government ain’t shit, never was shit, and will never be shit. The U.S. has been and will always be trash. Bottom of the barrel ass trash.

#fred hampton#judas and the black messiah#also idc what anyone says 21 and 19 are kid ages#at 21 your entire life is ahead of you and you are legit a child by many standards#the fbi killed a child and it would’ve been nothing for them to kill akua njeri and her unborn child as well#cause they’re trash

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

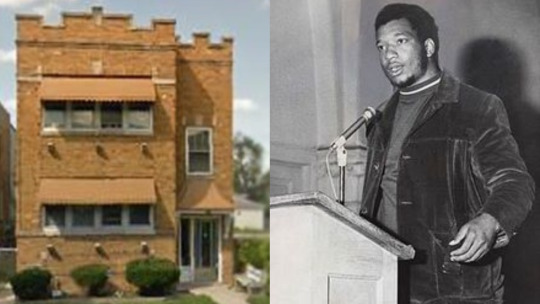

Childhood home of Fred Hampton gets historical landmark status

The Illinois childhood home of Fred Hampton, the iconic Black Panther Party leader who was fatally shot during a 1969 police raid, has been designated a historical landmark.

The Illinois childhood home of Fred Hampton, the iconic Black Panther Party leader who was fatally shot during a 1969 police raid, has been designated a historical landmark.

Childhood home of Fred Hampton historic landmark

Organizers of the Save The Hampton House initiative, led by Hampton’s son Fred Hampton Jr., and his mother Akua Njeri, announced that the Maywood Village Board voted to…

Photo: (GoFundMe)/(Fair Use Image)

View On WordPress

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

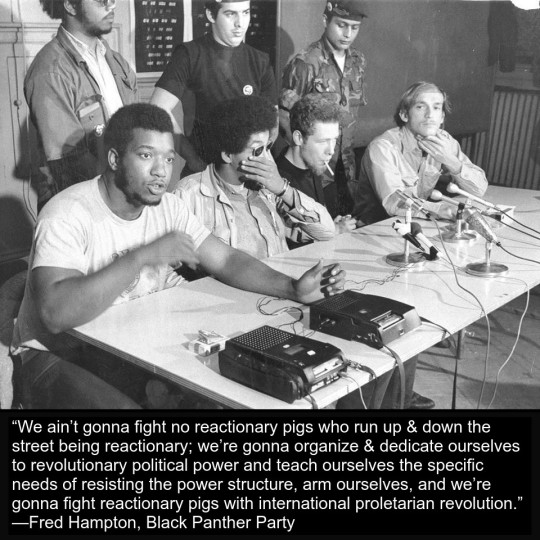

Fifty-one years ago today, Chicago police and FBI assassinated Fred Hampton and Mark Clark of the Black Panthers. If it happened in Central America, we'd call it "a right-wing death squad," but it happened in the middle of Chicago, so today it would be called a "police-involved shooting."

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover had said "the Black Panther Party without question represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country." They treated Hampton as such, and if you listen to him speak and see what he was doing, it's obvious why he frightened them so much.

Hampton was 21 years old.

1. “All Power to the People”

>> Transcript: https://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/fhamptonspeech.html

>> Recitation (by Michael B. Jordan): https://youtu.be/MnCK8wBAiKw?t=56

We got to face some facts. That the masses are poor, that the masses belong to what you call the lower class, and when I talk about the masses, I'm talking about the white masses, I'm talking about the black masses, and the brown masses, and the yellow masses, too. We've got to face the fact that some people say you fight fire best with fire, but we say you put fire out best with water. We say you don't fight racism with racism. We're gonna fight racism with solidarity. We say you don't fight capitalism with no black capitalism; you fight capitalism with socialism.

We ain't gonna fight no reactionary pigs who run up and down the street being reactionary; we're gonna organize and dedicate ourselves to revolutionary political power and teach ourselves the specific needs of resisting the power structure, arm ourselves, and we're gonna fight reactionary pigs with INTERNATIONAL PROLETARIAN REVOLUTION. That's what it has to be. The people have to have the power: it belongs to the people.

2. Akua Njeri, Widow of Fred Hampton, talking about the night of the assassination

>> Video: https://youtu.be/1DzzFEeHot8?t=14

>> Article: http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/079.html

Later the shooting stopped, "but Fred was not moving."

They (the police) grabbed my robe and started laughing, 'Well what do you know, we gotta broad here!'"

“I was very pregnant. They grabbed me by the hair and slung me into the kitchen area. I heard them say, 'He's barely alive' or 'He'll barely make it.' Then the shooting started again and then they said, 'He's good and dead now,' and I knew they had murdered Fred."

3. Fred Hampton on Revolution And Racism

>> Recording of Hampton Speaking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVzbSvWaMkc

>> Transcript: https://liberationschool.org/fred-hampton-on-revolution.../

When you leave here, leave here saying, the last words, before you go to bed tonight, say, “I am a revolutionary.” Make that the last words in case you don’t wake up.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The True History Behind 'Judas and the Black Messiah'

https://sciencespies.com/history/the-true-history-behind-judas-and-the-black-messiah/

The True History Behind 'Judas and the Black Messiah'

SMITHSONIANMAG.COM |

Feb. 11, 2021, 3:15 p.m.

When Chicago lawyer Jeffrey Haas first met Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, he was struck by the 20-year-old activist’s “tremendous amount of energy” and charisma. It was August 1969, and Haas, 26 years old at the time, and his fellow attorneys at the People’s Law Office had just secured Hampton’s release from prison on trumped-up charges of stealing $71 worth of ice cream bars. To mark the occasion, Hampton delivered a speech at a local church, calling on the crowd to raise their right hand and repeat his words: “I am a revolutionary.”

“I couldn’t quite say that, because I thought I was a lawyer for the movement, but not necessarily of the movement,” recalls Haas, who is white. “But as Fred continued saying that, by the third or fourth time, I was shouting ‘I am a revolutionary’ like everyone else.”

youtube

Judas and the Black Messiah, a new film directed by Shaka King and co-produced by Black Panther director Ryan Coogler, deftly dramatizes this moment, capturing both Hampton’s oratorical prowess and the mounting injustices that led him and his audience to declare themselves revolutionaries. Starring Daniel Kaluuya of Get Out fame as the chairman, the movie chronicles the months preceding Hampton’s assassination in a December 1969 police raid, detailing his contributions to the Chicago community and dedication to the fight for social justice. Central to the narrative is the activist’s relationship with—and subsequent betrayal by—FBI informant William O’Neal (LaKeith Stanfield), who is cast as the Judas to Hampton’s “black messiah.”

“The Black Panthers are the single greatest threat to our national security,” says a fictionalized J. Edgar Hoover (Martin Sheen), echoing an actual assertion made by the FBI director, in the film. “Our counterintelligence program must prevent the rise of a black messiah.”

Here’s what you need to know to separate fact from fiction ahead of Judas and the Black Messiah’s debut in theaters and on HBO Max this Friday, February 12.

Is Judas and the Black Messiah based on a true story?

In short: yes, but with extensive dramatic license, particularly regarding O’Neal. As King tells the Atlantic, he worked with screenwriter Will Berson and comedians Kenny and Keith Lucas to pen a biopic of Hampton in the guise of a psychological thriller. Rather than focusing solely on the chairman, they opted to examine O’Neal—an enigmatic figure who rarely discussed his time as an informant—and his role in the FBI’s broader counterintelligence program, COINTELPRO.

“Fred Hampton came into this world fully realized. He knew what he was doing at a very young age,” says King. “Whereas William O’Neal is in a conflict; he’s confused. And that’s always going to make for a more interesting protagonist.”

Daniel Kaluuya (center) as Fred Hampton

(Glen Wilson / Warner Bros.)

Speaking with Deadline, the filmmaker adds that the crew wanted to move beyond Hampton’s politics into his personal life, including his romance with fellow activist Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback), who now goes by the name Akua Njeri.

“[A] lot of times when we think about these freedom fighters and revolutionaries, we don’t think about them having families … and plans for the future—it was really important to focus on that on the Fred side of things,” King tells Deadline. “On the side of O’Neal, [we wanted] to humanize him as well so that viewers of the film could leave the movie wondering, ‘Is there any of that in me?’”

Who are the film’s two central figures?

Born in a suburb of Chicago in 1948, Hampton demonstrated an appetite for activism at an early age. As Haas, who interviewed members of the Hampton family while researching his book, The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther, explains, “Fred just couldn’t accept injustice anywhere.” At 10 years old, he started hosting weekend breakfasts for other children from the neighborhood, cooking the meals himself in what Haas describes as a precursor to the Panthers’ free breakfast program. And in high school, he led walkouts protesting the exclusion of black students from the race for homecoming queen and calling on officials to hire more black teachers and administrators.

According to William Pretzer, a supervisory curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), the young Hampton was keenly aware of racial injustice in his community. His mother babysat for Emmett Till prior to the 14-year-old’s murder in Mississippi in 1955; ten years after Till’s death, he witnessed white mobs attacking Martin Luther King Jr.’s Chicago crusade firsthand.

“Hampton is really influenced by the desire of the NAACP and King to make change, and the kind of resistance that they encounter,” says Pretzer. “So it’s as early as 1966 that Hampton starts to gravitate toward Malcolm X … [and his] philosophy of self-defense rather than nonviolent direct action.”

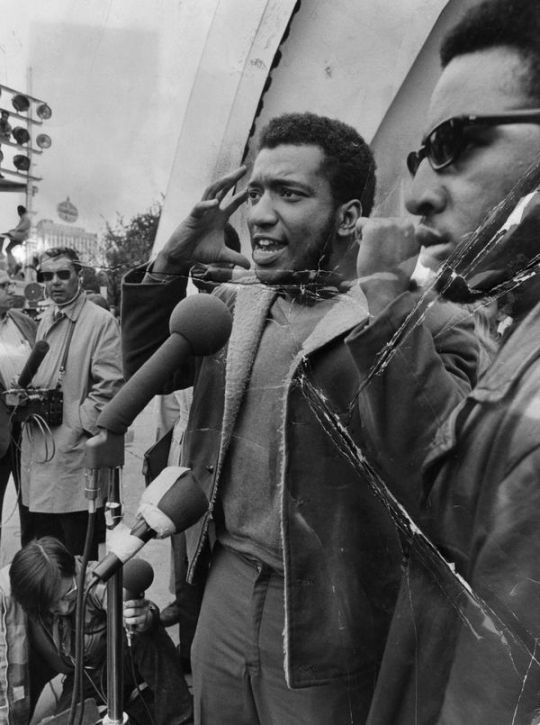

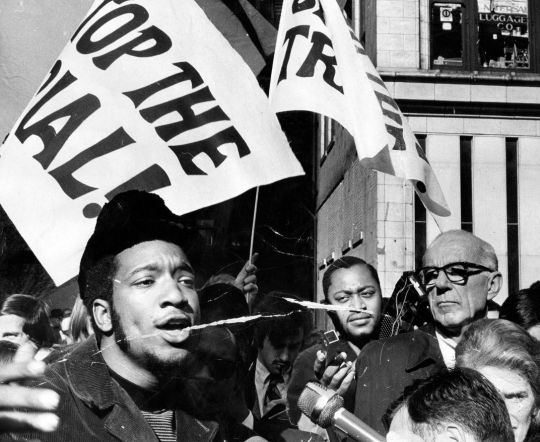

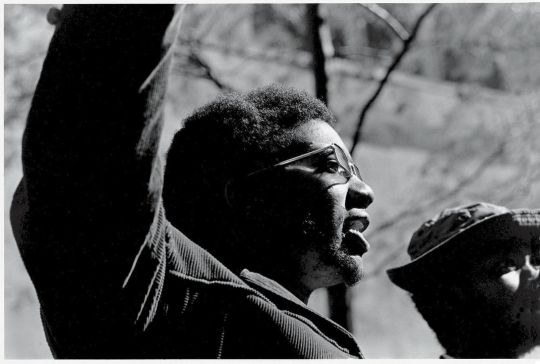

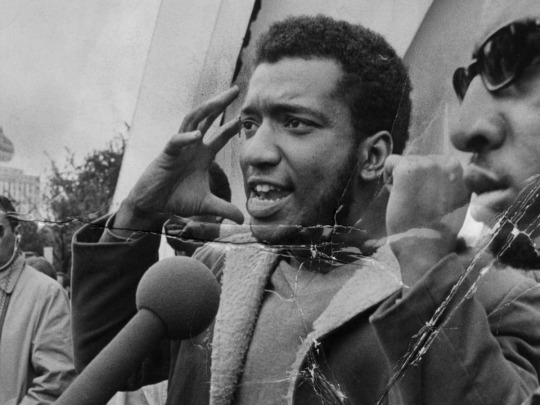

Fred Hampton speaks at a rally in Chicago’s Grant Park in September 1969

(Chicago Tribune file photo / Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

William O’Neal in a 1973 mugshot

(Fair use via Wikimedia Commons)

After graduating from high school in 1966, Hampton, as president of the local NAACP Youth Chapter, advocated for the establishment of an integrated community pool and recruited upward of 500 new members. In large part due to his proven track record of successful activism, leaders of the burgeoning Black Panther Party recruited Hampton to help launch the movement in Chicago in November 1968. By the time of his death just over a year later, he’d risen to the rank of Illinois chapter chairman and national deputy chairman.

O’Neal, on the other hand, was a habitual criminal with little interest in activism before he infiltrated the Panthers at the behest of FBI agent Roy Mitchell (portrayed in the film by Jesse Plemons). As O’Neal recalled in a 1989 interview, Mitchell offered to overlook the-then teenager’s involvement in a multi-state car theft in exchange for intel on Hampton.

“[A] fast-talking, conniving West Side black kid who thought he knew all the angles,” O’Neal, according to the Chicago Tribune, joined the party and quickly won members’ admiration with his bravado, mechanical and carpentry skills, and willingness to place himself in the thick of the action. By the time of the police raid that killed Hampton, he’d been appointed the Panthers’ chief of security.

“Unlike what we might think of an informer being a quiet person who would appear to be a listener, O’Neal was out there all the time spouting stuff,” says Haas. “People were impressed by that. … He was a ‘go do it’ guy. ‘I can fix this. I can get you money. I can do these kinds of things. And … that had an appeal for a while.”

Why did the FBI target Hampton?

Toward the beginning of Judas and the Black Messiah, Hoover identifies Hampton as a leader “with the potential to unite the Communist, the anti-war, and the New Left movements.” Later, the FBI director tells Mitchell that the black power movement’s success will translate to the loss of “[o]ur entire way of life. Rape, pillage, conquer, do you follow me?”

Once O’Neal is truly embedded within the Panthers, he discovers that the activists are not, in fact, “terrorists.” Instead, the informer finds himself dropped in the midst of a revolution that, in the words of co-founder Bobby Seale, was dedicated to “trying to make change in day-to-day lives” while simultaneously advocating for sweeping legislation aimed at achieving equality.

The Panthers’ ten-point program, penned by Seale and Huey P. Newton in 1966, outlined goals that resonate deeply today (“We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of Black people”) and others that were certain to court controversy (“We want all Black men to be exempt from military service” and “We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails”). As Jeff Greenwald wrote for Smithsonian magazine in 2016, members “didn’t limit themselves to talk.” Taking advantage of California’s open-carry laws, for instance, beret-wearing Panthers responded to the killings of unarmed black Americans by patrolling the streets with rifles—an image that quickly attracted the condemnation of both the FBI and upper-class white Americans.

Fred Hampton (far left) attends an October 1969 rally against the trial of eight people accused of conspiracy to start a riot at the Democratic National Convention.

(Don Casper / Chicago Tribune / Tribune News Service via Getty Images)

According to Pretzer, law enforcement viewed the Panthers and similar groups as a threat to the status quo. “They are focused on police harassment, … challenging the authority figures,” he says, “focusing on social activities that everybody thinks the government should be doing something about” but isn’t, like providing health care and ensuring impoverished Americans had enough to eat.

The FBI established COINTELPRO—short for counterintelligence program—in 1956 to investigate, infiltrate and discredit dissident groups ranging from the Communist Party of the United States to the Ku Klux Klan, the Nation of Islam and the Panthers. Of particular interest to Hoover and other top officials were figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X and Hampton, many of whom endured illegal surveillance, explicit threats and police harassment. Details of the covert program only came to light came to light in 1971, when activists stole confidential files from an FBI office in Pennsylvania and released them to the public.

Though Hampton stated that the Panthers would only resort to violence in self-defense, Hoover interpreted his words as a declaration of militant intentions.

“Because of COINTELPRO, because of the exacerbation, the harassment, the infiltration of these and agent provocateurs that they establish within these organizations, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy from the FBI’s point of view,” Pretzer explains, “[in that] they get the violence they were expecting.”

As Haas and law partner Flint Taylor wrote for Truthout in January, newly released documents obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request confirm the lawyers’ long-held suspicion that Hoover himself was involved in the plan to assassinate Hampton.

LaKeith Stanfield (left) as William O’Neal and Jesse Plemons (right) as FBI agent Roy Mitchell

(Glen Wilson / Warner Bros.)

What events does Judas and the Black Messiah dramatize?

Set between 1968 and 1969, King’s film spotlights Hampton’s accomplishments during his brief tenure as chapter chairman before delving into the betrayals that resulted in his death. Key to Hampton’s legacy were the Panthers’ survival programs, which sought to provide access to “fundamental elements of life,” per Pretzer. Among other offerings, the organization opened free health clinics, provided free breakfasts for children, and hosted political education classes that emphasized black history and self-sufficiency. (As Hampton said in 1969, “[R]eading is so important for us that a person has to go through six weeks of our political education before we can consider [them] a member.”)

On an average day, Hampton arrived at the Panthers’ headquarters with “a staccato of orders [that] gave energy to everyone around him,” says Haas. “But it wasn’t just what he asked people to do. He was there at 6:30 in the morning, making breakfast, serving the kids, talking to their parents.”

In addition to supporting these community initiatives—one of which, the free breakfast program, paved the way for modern food welfare policies—Hampton spearheaded the Rainbow Coalition, a boundary-crossing alliance between the Panthers, the Latino Young Lords, and the Young Patriots, a group of working-class white Southerners. He also brokered peace between rival Chicago gangs, encouraging them “to focus instead on the true enemy—the government and the police,” whom the Panthers referred to as “pigs,” according to the Village Free Press.

Fred Hampton raises his right hand at an October 11, 1969, rally in Chicago.

(Photo by David Fenton / Getty Images)

Speaking with Craig Phillips of PBS’ “Independent Lens” last year, historian Lilia Fernandez, author of Brown in the Windy City: Mexicans and Puerto Ricans in Postwar Chicago, explained, “The Rainbow Coalition presented a possibility. It gave us a vision for what could be in terms of interracial politics among the urban poor.”

Meanwhile, O’Neal was balancing his duties as an informant with his rising stature within the party. Prone to dramatic tendencies, he once built a fake electric chair intended, ironically, to scare informers. He also pushed the Panthers to take increasingly aggressive steps against the establishment—actions that led “more people, and Fred in particular, [to become] dubious of him,” says Haas.

The months leading up to the December 1969 raid found Hampton embroiled in legal troubles as tensions mounted between police and the Panthers. Falsely accused of theft and assault for the July 1968 ice cream truck robbery, he was denied bail until the People’s Law Office intervened, securing his release in August 1969. Between July and November of that year, authorities repeatedly clashed with the Panthers, engaging in shootouts that resulted in the deaths of multiple party members and police officers.

Daniel Kaluuya as Fred Hampton (far left) and LaKeith Stanfield as William O’Neal (far right)

(Glen Wilson / Warner Bros.)

By late November, the FBI, working off O’Neal’s intel, had convinced Cook County State’s Attorney Edward Hanrahan and the Chicago Police Department to raid Hampton’s home as he and his fiancée Johnson, who was nine months pregnant, slept. Around 4:30 a.m. on December 4, a heavily armed, 14-person raiding party burst into the apartment, firing upward of 90 bullets at the nine Panthers inside. One of the rounds struck and killed Mark Clark, a 22-year-old Panther stationed just past the front door. Though law enforcement later claimed otherwise, the physical evidence suggests that just one shot originated within the apartment.

Johnson and two other men tried to rouse the unconscious 21-year-old Hampton, who’d allegedly been drugged earlier that night—possibly by O’Neal, according to Haas. (O’Neal had also provided the cops with a detailed blueprint of the apartment.) Forced out of the bedroom and into the kitchen, Johnson heard a cop say, “He’s barely alive. He’ll barely make it.” Two shots rang out before she heard another officer declare, “He’s good and dead now.”

What happened after Hampton’s assassination?

Judas and the Black Messiah draws to a close shortly after the raid. In the film’s final scene, a conflicted O’Neal accepts an envelope filled with cash and agrees to continue informing on the Panthers. Superimposed text states that O’Neal remained with the party until the early 1970s, ultimately earning more than $200,000 when adjusted for inflation. After he was identified as the Illinois chapter’s mole in 1973, O’Neal received a new identity through the federal witness protection program. In January 1990, the 40-year-old, who’d by then secretly returned to Chicago, ran into traffic and was struck by a car. Investigators deemed his death a suicide.

“I think he was sorry he did what he did,” O’Neal’s uncle, Ben Heard, told the Chicago Reader after his nephew’s death. “He thought the FBI was only going to raid the house. But the FBI gave [the operation] over to the state’s attorney and that was all Hanrahan wanted. They shot Fred Hampton and made sure he was dead.”

The attempt to uncover the truth about Hampton and Clark’s deaths began on the morning of December 4 and continues to this day. While one of Haas’ law partners went to the morgue to identify Hampton’s body, another took stock of the apartment, which the police had left unsecured. Haas, meanwhile, went to interview the seven survivors, four of whom had been seriously injured.

A floor plan of Fred Hampton’s apartment provided to the FBI by William O’Neal

(People’s Law Office)

Hanrahan claimed that the Panthers had opened fire on the police. But survivor testimony and physical evidence contradicted this version of events. “Bullet holes” ostensibly left by the Panthers’ shots were later identified as nail heads; blood stains found in the apartment suggested that Hampton was dragged out into the hallway after being shot in his bed at point-blank range.

Public outrage over the killings, particularly within the black community, grew as evidence discounting the authorities’ narrative mounted. As one elderly woman who stopped by the apartment to see the crime scene for herself observed, the attack “was nothing but a Northern lynching.”

Following the raid, Hanrahan charged the survivors with attempted murder. Haas and his colleagues secured Johnson’s release early enough to ensure she didn’t give birth to her son, Fred Hampton Jr., in jail, and the criminal charges were eventually dropped. But the attorneys, “not content with getting people off, decided we needed to file a civil suit” alleging a conspiracy to not only murder Hampton, but cover up the circumstances of his death, says Haas.

Over the next 12 years, Haas and his colleagues navigated challenges ranging from racist judges to defendants’ stonewalling, backroom deals between the FBI and local authorities, and even contempt charges brought against the attorneys themselves. Working from limited information, including leaked COINTELPRO documents, the team slowly pieced together the events surrounding the raid, presenting compelling evidence of the FBI’s involvement in the conspiracy.

Hampton’s fiancée, Deborah Johnson (sitting in middle, as portrayed by Dominique Fishback), gave birth to their son, Fred Hampton Jr., 25 days after the raid.

(Glen Wilson / Warner Bros.)

Though a judge dismissed the original case in 1977 following an 18-month trial, Haas and the rest of the team successfully appealed for a new hearing. In 1982, after more than a decade of protracted litigation, the defendants agreed to pay a settlement of $1.85 million to the nine plaintiffs, including Clark’s mother and Hampton’s mother, Iberia.

“I used to describe being in court like going to a dog fight every day,” says Haas. “Everything we would say would be challenged. The [defendants’ lawyers] would tell the jury everything the Panthers had ever been accused of in Chicago and elsewhere, and [the judge] would let them do that, but he wouldn’t let us really cross examine the defendants.”

Hampton’s death dealt a significant blow to the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, frightening members with its demonstration of law enforcement’s reach and depriving the movement of a natural leader.

According to Pretzer, “What comes out is that the the assassination of Hampton is a classic example of law enforcement’s malfeasance and overreach and … provoking of violence.”

Today, says Haas, Hampton “stands as a symbol of young energy, struggle and revolution.”

The chairman, for his part, was keenly aware of how his life would likely end.

As he once predicted in a speech, “I don’t believe I’m going to die slipping on a piece of ice; I don’t believe I’m going to die because I got a bad heart; I don’t believe I’m going to die because of lung cancer. I believe that I’m going to be able to die doing the things I was born for. … I believe that I will be able to die as a revolutionary in the international revolutionary proletarian struggle.”

#History

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

On this day, 4 December 1969, Chicago Black Panther leader Fred Hampton was murdered while asleep in his bed during a raid on his apartment by Chicago Police in conjunction with the FBI. Hampton had been drugged earlier in the evening by an FBI informant, who also told agents the location of Hampton's bed, where he slept alongside his nine-month pregnant fiancée, Akua Njeri. Fellow Panther activist Mark Clark was also killed in the attack, and several others injured. Aged just 21, Hampton was an active, charismatic and effective organiser, who had been making significant inroads into making links with working class whites and building a "Rainbow Coalition" including Puerto Rican, Native American, Chicane, white and Chinese-American radicals. Hampton and Clark were amongst the most prominent victims of the FBI's COINTELPRO program, which amongst other things was directed by FBI director J Edgar Hoover to "prevent the rise of a Black Messiah". Learn more about the Panthers in these books by former members: https://shop.workingclasshistory.com/collections/books/black-panthers https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.1819457841572691/1869207689931039/?type=3

789 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“You can’t murder FREEDOM” - Chairman Fred Hampton Sr. Happy for my beautiful brother @officialchairmanfredhamptonjr, and even more so, my revolutionary mother, mama Akua Njeri. Happy and honored that BOTH parents’ stories are being told. I woke up today crying cuz I know for a fact how long this road has been with them dealing with the making of this film. I woke up also with a feeling of relief. Although today is the release of @JudasandtheBlackMessiahFi, the fight isn’t over. If you care about the film, care about saving the Hampton House. to ALL of the Cubs, to all of the children of MOVE... in EVERY state, EVERY country:: I know it is hard being black. I know it is hard to live thru pain. I know the war is uncertain. I know carrying the loads of legends is heavy. I know the expectations are high. I know the assumptions are loaded. And I definitely know the accuracies in passed down stories have been stretched. But even thru all of that, we still are lucky af to be BLACK. May we all one day be free. I love y’all. Sincerely. #freeEmALL ✊🏿✊🏾✊🏽 #weRIDE ✊🏿✊🏾✊🏽 https://www.instagram.com/p/CLMjBDEFWW5/?igshid=4r8qodys6iho

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Police officers with the body of Black Panther Illinois Party leader, Fred Hampton, who was killed sleeping in his bed next to his pregnant girlfriend, Akua Njeri (Deborah Johnson at the time). Featured in 13th (2016).

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fred Hampton

Fred Hampton (August 30, 1948 – December 4, 1969) was an American activist and revolutionary, chairman of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party (BPP), and deputy chairman of the national BPP. Hampton was assassinated while sleeping at his apartment during a raid by a tactical unit of the Cook County, Illinois State's Attorney's Office, in conjunction with the Chicago Police Department and the Federal Bureau of Investigation in December 1969. A civil lawsuit filed in 1970 resulted in 1982 in a settlement of $1.85 million The background and events of Hampton's murder have been chronicled in several documentary films.

Early life and youth

Hampton was born on August 30, 1948, in present-day Summit, Illinois, and grew up in Maywood, a suburb west of the city. His parents had moved north from Louisiana, and both worked at the Argo Starch Company. As a youth, Hampton was gifted both in the classroom and on the athletic field, and strongly desired to play center field for the New York Yankees. He graduated from Proviso East High School with honors in 1966. Following his graduation, Hampton enrolled at Triton Junior College in nearby River Grove, Illinois, where he majored in pre-law. He planned to become more familiar with the legal system, to use it as a defense against police. He and fellow Black Panthers would follow police, watching out for police brutality, and used this knowledge of law as a defense.

He also became active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and assumed leadership of the Youth Council of the organization's West Suburban Branch. In his capacity as an NAACP youth organizer, Hampton began to demonstrate his natural leadership abilities; from a community of 27,000, he was able to muster a youth group 500-members strong. He worked to get more and better recreational facilities established in the neighborhoods, and to improve educational resources for Maywood's impoverished black community. Through his involvement with the NAACP, Hampton hoped to achieve social change through nonviolent activism and community organizing.

Chicago

About the same time that Hampton was successfully organizing young African-Americans for the NAACP, the Black Panther Party (BPP) started rising to national prominence. Hampton was quickly attracted to the Black Panthers' approach, which was based on a ten-point program that integrated black self-determination on the basis of Maoism. Hampton joined the Party and relocated to downtown Chicago, and in November 1968 he joined the Party's nascent Illinois chapter—founded by Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organizer Bob Brown in late 1967. Over the next year, Hampton and his associates made a number of significant achievements in Chicago. Perhaps his most important accomplishment was his brokering of a nonaggression pact between Chicago's most powerful street gangs. Emphasizing that racial and ethnic conflict between gangs would only keep its members entrenched in poverty, Hampton strove to forge a class-conscious, multi-racial alliance between the BPP, the Young Patriots Organization, and the Young Lords under the leadership of Jose Cha Cha Jimenez.

Fred Hampton met Cha Cha and the Young Lords in the Chicago Lincoln Park Neighborhood, the day after the Young Lords were in the news after they had occupied a police community workshop meeting, held on the second floor hall of the Chicago 18th District Police Station. Later, the Rainbow Coalition was joined nationwide by the Students for a Democratic Society ("SDS"), the Brown Berets, and the Red Guard Party. In May 1969, Hampton called a press conference to announce that this "rainbow coalition" had formed. It was a phrase coined by Hampton and made popular over the years by Rev. Jesse Jackson, who eventually appropriated the name in forming his own, unrelated, coalition, Rainbow/PUSH.

Hampton's organizing skills, substantial oratorical gifts, and personal charisma allowed him to rise quickly in the Black Panthers. Once he became leader of the Chicago chapter, he organized weekly rallies, worked closely with the BPP's local People's Clinic, taught political education classes every morning at 6am, and launched a project for community supervision of the police. Hampton was also instrumental in the BPP's Free Breakfast Program. When Brown left the Party with Stokely Carmichael in the FBI-fomented SNCC/Panther split, Hampton assumed chairmanship of the Illinois state BPP, automatically making him a national BPP deputy chairman. As the Panther leadership across the country began to be decimated by the impact of the FBI's COINTELPRO, Hampton's prominence in the national hierarchy increased rapidly and dramatically. Eventually, Hampton was in line to be appointed to the Party's Central Committee's Chief of Staff. He would have achieved this position had it not been for his assassination on the morning of December 4, 1969.

FBI investigation

While Hampton impressed many of the people with whom he came into contact as an effective leader and talented communicator, those very qualities marked him as a major threat in the eyes of the FBI. It began keeping close tabs on his activities. Subsequent investigations have shown that FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover was determined to prevent the formation of a cohesive Black movement in the United States. Hoover saw the Panthers, Young Patriots, Young Lords, and similar radical coalitions forged by Hampton in Chicago as a frightening steppingstone toward the creation of such a revolutionary body that could, in its strength, cause a radical change in the U.S. government. The FBI opened a file on Hampton in 1967. Hampton's mother's phone was tapped in February 1968, and Hampton was placed on the Bureau's "Agitator Index" as a "key militant leader" by May. In late 1968, the Racial Matters squad of the FBI's Chicago field office brought in an individual named William O'Neal, who had recently been arrested twice, for interstate car theft and impersonating a federal officer. In exchange for having his felony charges dropped and a monthly stipend, O'Neal apparently agreed to infiltrate the BPP as a counterintelligence operative. He joined the Party and quickly rose in the organization, becoming Director of Chapter security and Hampton's bodyguard. In 1969, the FBI special agent in San Francisco wrote Hoover that the agent's investigation of the BPP revealed that in his city, at least, the Panthers were primarily feeding breakfast to children. Hoover fired back a memo implying the career ambitions of the agent were directly related to his supplying evidence to support Hoover's view that the BPP was "a violence-prone organization seeking to overthrow the Government by revolutionary means".

By means of anonymous letters, the FBI sowed distrust and eventually instigated a split between the Panthers and the Rangers, with O'Neal himself instigating an armed clash between the two on April 2, 1969. The Panthers became effectively isolated from their power base in the ghetto, so the FBI went to work to undermine its ties with other radical organizations. O'Neal was instructed to "create a rift" between the Party and SDS, whose Chicago headquarters was only blocks from that of the Panthers. The Bureau released a batch of racist cartoons in the Panthers' name, aimed at alienating white activists, and launched a disinformation program to forestall the realization of the Rainbow Coalition but nevertheless it was formed with an alliance of the Young Patriots and Young Lords. In repeated directives, Hoover demanded that the COINTELPRO personnel investigate the Rainbow Coalition and "destroy what the [BPP] stands for" and "eradicate its 'serve the people' programs".

Documents secured by Senate investigators in the early 1970s revealed that the FBI actively encouraged violence between the Panthers and other radical groups, which provoked multiple murders in cities throughout the country. On May 26, 1969, Hampton was successfully prosecuted in a case related to a theft in 1967 of $71 worth of Good Humor Bars in Maywood. He was sentenced to two to five years but managed to obtain an appeal bond, and was released in August. On July 16, there was an armed confrontation between party members and the Chicago Police Department, which left one BPP member mortally wounded and six others arrested on serious charges. In early October, Hampton and his girlfriend, Deborah Johnson (now known as Akua Njeri), pregnant with their first child (Fred Hampton Jr.), rented a four-and-a-half room apartment on 2337 West Monroe Street to be closer to BPP headquarters. O'Neal reported to his superiors that much of the Panthers' "provocative" stockpile of arms was being stored there and drew them a map of the layout of the apartment. In early November, Hampton traveled to California on a speaking engagement to the UCLA Law Students Association. While there, he met with the remaining BPP national hierarchy, who appointed him to the Party's Central Committee. Shortly thereafter, he was to assume the position of Chief of Staff and major spokesman.

1969 raid and assassination

Fred Hampton was quickly moving up the ranks in the Black Panther Party, and his talent as a political organizer was described as remarkable. In 1968, he was on the verge of creating a merger between the BPP and a southside street gang with thousands of members, which would have doubled the size of the national BPP. Moreover, it meant an alliance extending the Black Panther Party reach and influence united with white and Latino organizers, a step which Hoover viewed as an untenable ultimate threat and ordered an intensified FBI crackdown to the level of "any means necessary" to decimate the BPP.

In November 1969, Hampton traveled to California and met with the National BPP leadership at UCLA. It was there that they offered him a position on the Central Committee as the chief of staff and asked him to serve as the national spokesman for the BPP. While Hampton was out of town, two Chicago police officers, John J. Gilhooly and Frank G. Rappaport, were killed in a gun battle with Panthers on the night of November 13. A total of nine police officers were shot; a 19-year-old Panther named Spurgeon Winter Jr. was killed by police and another Panther, Lawrence S. Bell, was charged with murder. In an editorial headlined "No Quarter for Wild Beasts", the Chicago Tribune urged that Chicago police be given the order to approach all Panther suspects prepared to shoot. The FBI, determined to prevent any enhancement of the BPP leadership's effectiveness, decided to set up an arms raid on Hampton's Chicago apartment. FBI informant William O'Neal provided them with detailed information about Hampton's apartment, including the layout of furniture and the bed in which Hampton and his girlfriend slept. An augmented, 14-man team of the SAO—Special Prosecutions Unit—was organized for a pre-dawn raid armed with a warrant for illegal weapons.

On the evening of December 3, Hampton taught a political education course at a local church, which was attended by most members. Afterwards, as was typical, several Panthers retired to the Monroe Street apartment to spend the night, including Hampton and Deborah Johnson (also known as Akua Njeri), Blair Anderson, Ronald "Doc" Satchell, Harold Bell, Verlina Brewer, Louis Truelock, Brenda Harris, and Mark Clark. Upon arrival, they were met by O'Neal, who had prepared a late dinner, which the group ate around midnight. O'Neal had slipped the barbiturate sleep agent, secobarbitol, into a drink that Hampton consumed during the dinner, in order to sedate Hampton so he would not awaken during the subsequent raid. O'Neal left at this point, and, at about 1:30 a.m., Hampton fell asleep mid-sentence talking to his mother on the telephone. Although Hampton was not known to take drugs, Cook County chemist Eleanor Berman would report that she ran two separate tests which each showed evidence of barbiturates in Hampton's blood. An FBI chemist would later fail to find similar traces, but Berman stood by her findings.

The raid was organized by the office of Cook County State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, using officers attached to his office. Hanrahan had recently been the subject of a large amount of public criticism by Hampton, who had made speeches about how Hanrahan's talk about a "war on gangs" was really rhetoric used to enable him to carry out a "war on black youth". At 4:00 a.m., the heavily armed police team arrived at the site, divided into two teams, eight for the front of the building and six for the rear. At 4:45 a.m., they stormed into the apartment. Mark Clark, sitting in the front room of the apartment with a shotgun in his lap, was on security duty. He was shot in the chest and died instantly. His gun fired a single round which was later determined to be caused by a reflexive death convulsion after the raiding team shot him; this was the only shot the Panthers fired. Automatic gunfire then converged at the head of the south bedroom where Hampton slept, unable to awaken as a result of the barbiturates the FBI infiltrator had slipped into his drink. He was lying on a mattress in the bedroom with his fiancée, who was eight-and-a-half months pregnant with their child. Two officers found him wounded in the shoulder, and fellow Black Panther Harold Bell reported that he heard the following exchange:

"That's Fred Hampton.""Is he dead?... Bring him out.""He's barely alive."He'll make it."

Two shots were heard, which were later discovered were fired point blank in Hampton's head. According to Johnson, one officer then said:

"He's good and dead now."

Hampton's body was dragged into the doorway of the bedroom and left in a pool of blood. The officers then directed their gunfire towards the remaining Panthers, who had been sleeping in the north bedroom (Satchel, Anderson, and Brewer). Verlina Brewer, Ronald "Doc" Satchel, Blair Anderson, and Brenda Harris were seriously wounded, then beaten and dragged into the street, where they were arrested on charges of aggravated assault and the attempted murder of the officers. They were each held on US$100,000 bail.

Hampton's fiancée, Deborah Johnson, was sleeping next to him when the police raid began. She was forcibly removed from the room by the police officers while Hampton lay unconscious in bed. The seven Panthers who survived the raid were indicted by a grand jury on charges of attempted murder, armed violence, and various other weapons charges. These charges were subsequently dropped. During the trial, the Chicago police department claimed that the Panthers were the first to fire shots; however, a later investigation found that the Chicago police fired between ninety and ninety-nine shots while the Panthers had only shot once. After the raid, the apartment was left unguarded, which allowed the Panthers to send some members to investigate. They were accompanied by a videographer and the footage was later released in the 1971 documentary The Murder of Fred Hampton. After a break-in at an FBI office in Pennsylvania, the existence of COINTELPRO, an illegal counter-intelligence program, was brought to light. The awareness of this program caused many to suspect that the police raid and the shooting of Fred Hampton were parts of the program's initiative. One of the documents that were released after the break-in was a floor plan of Hampton's apartment. Another document outlined a deal the FBI brokered with the deputy attorney general to conceal the FBI's role in the assassination of Hampton and the existence of COINTELPRO.

Aftermath

At a press conference the next day, the police announced the arrest team had been attacked by the "violent" and "extremely vicious" Panthers and had defended themselves accordingly. In a second press conference on December 8, the assault team was praised for their "remarkable restraint", "bravery", and "professional discipline" for not killing all the Panthers present. Photographic evidence was presented of "bullet holes" allegedly made by shots fired by the Panthers, but this was soon challenged by reporters (although the Chicago Tribune initially published these photos in support of the police action). An internal investigation was undertaken, and the assault team was exonerated of any wrongdoing. Hampton's funeral was attended by 5,000 people, and he was eulogized by such black leaders as Jesse Jackson and Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King's successor as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In his eulogy, Jackson noted that "when Fred was shot in Chicago, black people in particular, and decent people in general, bled everywhere." On December 6, members of the Weather Underground destroyed numerous police vehicles in a retaliatory bombing spree at 3600 N. Halsted Street, Chicago.

The police described the police raid as a "shootout". The Black Panthers countered Hanrahan’s claim of a "shoot out" by describing it as a "shoot-in", not a shootout, because all but one bullet was fired by the police. A firestorm erupted on December 11 and 12 between the two competing daily newspapers, the Chicago Tribune and the Chicago Sun-Times. At that time, the Chicago Tribune was considered the politically conservative newspaper, and the Chicago Sun-Times was considered the politically liberal newspaper. On December 11, the Chicago Tribune published a page 1 article titled, "Exclusive – Hanrahan, Police Tell Panther Story." The article included photographs supplied by Hanrahan’s office that depicted bullet holes in a thin white curtain and door jam as evidence that the Panthers fired multiple bullets at the police. The firestorm was triggered in part by Jack Challem, editor of the Wright College News, the student newspaper at Wright Junior College in Chicago. Challem visited the Hampton apartment on Saturday, December 6, and took numerous photographs. The house was not sealed as a crime scene, and a member of the Black Panthers was allowing visitors to tour the apartment. Challem’s photographs did not show any bullet holes. On the morning of December 12, after the Chicago Tribune article was published, Challem contacted a reporter at the Chicago Sun-Times, showed him the photographs, and encouraged him to visit the apartment. That evening, the Chicago Sun-Times published a page 1 article with the headline: “Those ‘bullet holes’ aren’t.” According to the article, the alleged bullet holes (supposedly the result of the Panthers shooting in the direction of the police) were nail heads.

But Challem’s story and photographs, published in the Wright College News, tell a different story and pose unanswered questions. First, there were no nail heads (or bullet holes) in his photographs. The implication, though speculative, is that someone tampered with the crime scene between December 6 and December 12 to make it appear as though the “nail heads” were innocently mistaken as “bullet holes.” Second, it is difficult, if not impossible, to photograph a bullet hole in a thin white curtain without retouching the photograph, another sign that evidence had been tampered with. Four weeks after witnessing Hampton's death at the hands of the police, Deborah Johnson gave birth to Fred Hampton Jr. Civil rights activists Roy Wilkins and Ramsey Clark (styled as "The Commission of Inquiry into the Black Panthers and the Police") subsequently alleged that the Chicago police had killed Fred Hampton without justification or provocation and had violated the Panthers' constitutional rights against unreasonable search and seizure. "The Commission" further alleged that the Chicago Police Department had imposed a summary punishment on the Panthers. The federal grand jury did not return any indictment against anyone involved with the planning or execution of the raid. The officers involved in the raid were cleared by a grand jury of any crimes. The FBI informant, William O'Neal, committed suicide in 1990 after admitting his involvement in setting up the raid.

Inquest

Shortly afterwards, Cook County coroner Andrew Toman began forming a special six-member coroner's jury to hold an inquest into the deaths of Hampton and Clark. On December 23, Toman announced four additions to the jury which included two African-American men: physician Theodore K. Lawless and attorney Julian B. Wilkins, the son of J. Ernest Wilkins, Sr. He stated the four were selected from a group of candidates submitted to his office by groups and individuals representing both Chicago's black and white communities. Civil rights leaders and spokesmen for the black community were reported to have been disappointed with the selection. An official with the Chicago Urban League said: "I would have had more confidence in the jury if one of them had been a black man who has a rapport with the young and the grass roots in the community." Gus Savage said that such a man to whom the community could relate need not be black. The jury eventually included a third black man who was a member of the first coroner's jury sworn in on December 4.

The blue-ribbon panel convened for the inquest on January 6, 1970, and on January 21 ruled the deaths of Hampton and Clark to be justifiable homicide. The jury qualified their verdict on the death of Hampton as "based solely and exclusively on the evidence presented to this inquisition"; police and expert witness provided the only testimony during the inquest. Jury foreman James T. Hicks stated that they could not consider the charges of the Black Panthers in the apartment who stated that the police entered the apartment shooting; those who survived the raid were reported to have refused to testify during the inquest because they faced criminal charges of attempted murder and aggravated assault during the raid. Attorneys for the Hampton and Clark families also did not introduce any witnesses during the proceedings, but described the inquest as "a well-rehearsed theatrical performance designed to vindicate the police officers". State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan said the verdict was recognition "of the truthfulness of our police officers' account of the events".

Civil rights lawsuit

In 1970, a $47.7 million lawsuit was filed on behalf of the survivors and the relatives of Hampton and Clark stating that the civil rights of the Black Panther members were violated. Twenty-eight defendants were named, including Hanrahan as well as the City of Chicago, Cook County, and federal governments. The following trial lasted 18 months and was reported to have been the longest federal trial up to that time. After its conclusion in 1977, Judge Joseph Sam Perry of United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois dismissed the suit against 21 of the defendants prior to jury deliberations. Perry dismissed the suit against the remaining defendants after jurors deadlocked. In 1979, the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit in Chicago stated that the government had withheld relevant documents thereby obstructing the judicial process. Reinstating the case against 24 of the defendants, the Court of Appeals ordered a new trial. The Supreme Court of the United States heard an appeal but voted 5–3 in 1980 to return the case to the District Court for a new trial. In 1982, the City of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government agreed to a settlement in which each would pay $616,333 to a group of nine plaintiffs, including the mothers of Hampton and Clark. The $1.85 million settlement was believed to be the largest ever in a civil rights case.

Legacy

Legal and political impacts

According to a 1969 Chicago Tribune report, "The raid ended the promising political career of Cook County State's Atty. Edward V. Hanrahan, who was indicted but cleared with 13 other law-enforcement agents on charges of obstructing justice. Bernard Carey, a Republican, defeated him in the next election, in part because of the support of outraged black voters." The families of Hampton and Clark filed a US$47.7 million civil suit against the city, state, and federal governments. The case went to trial before Federal Judge J. Sam Perry. After more than 18 months of testimony and at the close of the Plaintiff's case, Judge Perry dismissed the case. The Plaintiffs appealed and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit reversed, ordering the case to be retried. More than a decade after the case had been filed, the suit was finally settled for $1.85 Million. The two families each shared in the settlement. Jeffrey Haas, who, together with his law partners G. Flint Taylor and Dennis Cunningham and attorney James D. Montgomery, were the attorneys for the plaintiffs in the federal suit Hampton v. Hanrahan, wrote in his book about the Hampton assassination that Chicago was worse off without Hampton:

In 1990, the Chicago City Council unanimously passed a resolution, introduced by then-Alderman Madeline Haithcock, commemorating December 4, 2004, as "Fred Hampton Day in Chicago". The resolution read in part: "Fred Hampton, who was only 21 years old, made his mark in Chicago history not so much by his death as by the heroic efforts of his life and by his goals of empowering the most oppressed sector of Chicago's Black community, bringing people into political life through participation in their own freedom fighting organization."

Monuments and streets

A public pool was named in his honor in his home town of Maywood, Illinois. In March 2006, supporters of Hampton's charity work proposed the naming of a Chicago street in honor of the former Black Panther leader. Chicago's chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police opposed this effort. On Saturday September 7, 2007, a bust of Hampton was erected outside the Fred Hampton Family Aquatic Center.

Weather Underground reaction

In response to the killings of Fred Hampton and Mark Clark in December 1969, on May 21, 1970, the Weather Underground issued a "Declaration of War" against the United States government, using for the first time its new name, the "Weather Underground Organization" (WUO); they also adopted fake identities, and decided to pursue covert activities only. These initially included preparations for a bombing of a U.S. military non-commissioned officers' dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in what Brian Flanagan said had been intended to be "the most horrific hit the United States government had ever suffered on its territory".

We've known that our job is to lead white kids into armed revolution. We never intended to spend the next five to twenty-five years of our lives in jail. Ever since SDS became revolutionary, we've been trying to show how it is possible to overcome frustration and impotence that comes from trying to reform this system. Kids know the lines are drawn: revolution is touching all of our lives. Tens of thousands have learned that protest and marches don't do it. Revolutionary violence is the only way.

Media and popular cultureIn film

A 27-minute documentary entitled Death of a Black Panther: The Fred Hampton Story was used as evidence in the civil suit. Although Hampton had criticized the predominantly white Weather Underground (also known as the Weathermen) two months earlier for being "adventuristic, masochistic and Custeristic", Bernardine Dohrn of the Weathermen, which had a close relationship with the Black Panthers in Chicago at the time of Hampton's assassination, said in the documentary The Weather Underground (2002) that the killing of Fred Hampton caused them to "be more grave, more serious, more determined to raise the stakes, and not just be the white people who wrung their hands when black people were being murdered." The events of Hampton's rise to significance, J. Edgar Hoover's targeting of him, and Hampton's subsequent assassination are recounted with footage in the 2015 documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.

In literature

Haas wrote an account of Hampton's murder, entitled The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther (2009). Stephen King refers to Hampton in the novel 11/22/63 (2012), where a character discusses the ripple effect of traveling back in time to prevent President John F. Kennedy's assassination, which the character postulates would give rise to a series of events that could prevent Fred Hampton's assassination, as well.

In music

Lyrics that reference Hampton include:

"Nashville" star Ronee Blakley's solo LP, "Ronee Blakley" (1972), includes the lyrics "I want to be a part of Fred Hampton / I want to be a part of his purity / You've got to heal the wounds".

Spoon’s "Loss Leaders", from the "Soft Effects" EP, says "Fred tried to change their ways 'til he got some bullet holes / now he lives in outer space".

Rage Against the Machine's "Down Rodeo" says: "They ain't gonna send us campin' like they did my man Fred Hampton".

Ramshackle Glory refers to Fred Hampton in "First Song, Part 2", followed by an explanation that "justice doesn't flow from police guns, I'm reminded of that all the time".

Jay-z mentions Fred Hampton on "Murder to Excellence" on Watch The Throne in the lyric "I arrived on the day Fred Hampton died, real n*ggas just multiply".

Kendrick Lamar mentions Fred Hampton in his song "HiiiPoWeR" from Section.80. In it, Lamar says "Fred Hampton on your campus, you can't resist his... HiiiPoWeR."

Wikipedia

46 notes

·

View notes