#catholic worker movement

Text

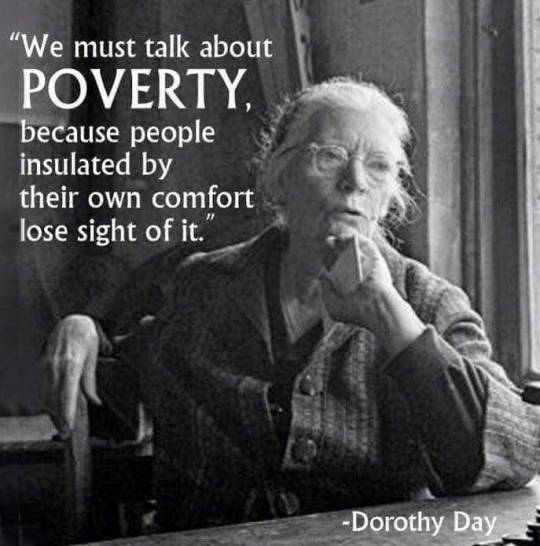

But I am sure that God did not intend that there be so many poor. The class structure is of our making and our consent, not His. It is the way we have arranged it, and it is up to us to change it. So we are urging revolutionary change.

Dorothy Day, "Poverty Is to Care And Not to Care"

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Left side: In clockwise order from the top left, Dorothy Day (Catholic Worker Movement), Daniel Berrigan (Anti-Vietnam War/Ploughshares Movement/Peace activist, imprisoned for draft resistance activities), Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Anti-German government from 1933-1945, when he was murdered by that same German government), and Oscar Romero (now a saint, human rights and social reform advocate in El Salvador (Liberation Theology adjacent), murdered with the approval of the CIA in 1981). And then MLK.

Right side: Christofascists you are probably very familiar with. The least persecuted people ever crying the loudest that they are being repressed. Fuck 'em all.

It's weird to think my dad knew Daniel Berrigan (fairly well, they were in the Jesuits at the same time and Berrigan influenced him to become a CO during Vietnam, though his draft number was never called (he ripped up his draft card when he received it, kept half of it in his wallet for a long time, I think it's now somewhere in his office)) and Dorothy Day (through folks who had been with CW for a long time, he said she was great but the way some Catholic Worker folks revered her was a little culty, and this was in 1960s-1970s San Francisco, where most things were a little culty to begin with) along with several people who knew Romero and Merton (not featured here but Thomas Merton is tops). Small world, I guess.

#catholic left#dietrich bonhoeffer#daniel berrigan#dorothy day#catholic worker movement#oscar romero#mlk jr#christofascists

39 notes

·

View notes

Note

Servant of God Dorothy Day!

DOROTHY DAY AND THE CATHOLIC WORKER MOVEMENT UHHHHH YESSS PLEASE AND THANK YOU @pierre-menard FOR BRINGING HER IN

This is her first nomination, so she'll need more votes for the beatified category!!

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

22 notes

·

View notes

Note

you totally don’t have to answer this but do you live in a catholic worker movement house??? what’s it like? do you love it?

hey nicki, thank you so much for this question! an opportunity to monologue about my most beloved topic!

I lived at a Catholic Worker house for one semester before law school. I got obsessed with the Catholic Worker Movement in high school, and I’m (kinda) involved in my new town and am currently working on a conference presentation about the CWM. if anyone is interested in getting involved/newspaper subscriptions/etc please DM me!

the CWM is based in voluntary poverty, community, pacifism, and personalism. I believe that it is the highest form of union with the Mystical Body of Christ readily available to laypeople. the only way our faith can thrive is to reject the complacency of the status quo and “blow the dynamite inherent in the Church’s message.” God’s will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

my House focuses on accepting recent migrants and serving our city’s broader migrant community. an average day would be liturgy of the hours, then around 4 hours of food distribution through the food bank, lunch (beans and rice), accepting new arrivals and figuring out guests’ travel plans, dealing with immigration paperwork, driving people to healthcare appointments, organizing donations, filling prescriptions, writing our daily chore list to keep the house running, cleaning EVERYTHING, and teaching in any spare time.

it’s honestly a stretch to say that I LOVED my time at our specific House. I had a lottttt of high ideals after years of scholarship, but people are still people even with the grace of the Holy Spirit. we were all exhausted with almost no nutrition, and I got MEAN pretty fast, to my eternal horror. I also didn’t speak Spanish very well, and the language barrier made personalism very difficult in practice. I think God pranked me personally by giving us the worst cockroach infestation in years.

however, the House also taught me in a brutal way that my own comfort is not the priority, and that I am called to be a little stepping stone to ease someone’s sorrows on their journey.

Jesus is a migrant. God reveals Himself in the face of the migrant. a mugging victim whose head is ringed with blood like a crown of thorns. a little girl who sprints towards her father after they were separated in detention. the teenager who suffered such violence at the hands of cartels that she can’t even speak anymore, can’t remember how to write her own name. the diabetic patients with all their limbs amputated because insulin is fatally expensive.

the CWM is always going to be my spiritual home because it always reminds me that whatever you did to the least of my brothers, you did unto me. community is hard but it’s worth it. “we have all known the long loneliness, and we have found that the solution is love, and that love comes with community.”

#sorry for the rant this is genuinely my favorite thing to talk about#I am so obsessed#catholic worker movement#about me#catholicism#dorothy day

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Dorothy Day, whose work I read in medical school upon the recommendation of a Catholic classmate and friend, co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement, which created Catholic Worker Houses (where my friend worked) to serve those who are poor or marginalized. The Catholic Worker community here in town, Casa Juan Diego, says that they offer 'hospitality and services for immigrant women, men, and children.' They also have a clinic and food distribution program. So they are meeting people’s basic needs in the community. For Day and others in the movement, working in these settings was not only a way to serve the community but to build community, which was fundamental to a person’s faith. Faith — and one’s practice of works grounded in faith — was a communal, not individual, experience:

Together with the Works of Mercy, feeding, clothing and sheltering our brothers and sisters, we must … 'give reason for the faith that is in us.' Otherwise we are scattered members of the Body of Christ, we are not 'all members one of another.' Otherwise our religion is an opiate, for ourselves alone, for our comfort or for our individual safety or indifferent custom. We cannot live alone. We cannot go to Heaven alone.

'Community is good' seems obvious, but Day’s words always struck me as rather profound, as I grew up in a Catholic family but always felt that no one in the Church (priests, Sunday catechism teachers) ever talked about the social responsibilities of Catholics or about how faith ought to be expressed in social, or communal, and not individual, ways. (My Catholic friend also introduced me to liberation theology, which, with its emphasis on political liberation of oppressed people, was, I discovered, more my speed.)

I don’t think Day’s ideas only apply to Catholics or to matters of how to practice one’s faith. I’ve always interpreted Day’s quote about 'the long loneliness' not just as a metaphor for her journey toward Catholicism (she converted as an adult) but as a metaphor for the loneliness each of us experiences in our lives — the physical and emotional and existential loneliness of modern life, or even the search for meaning and purpose in life. The solution, according to Day — love — must come about through active engagement in community, not just being an individual actor alongside other actors in an increasingly impersonal society. The Catholic Worker movement was also about the concept of personalism, which 'emphasized the freedom and dignity of each person' and moved 'away from a self-centered individualism toward the good of the other.' This is such an important concept for people who live in hyper-individualistic societies like the U.S."

- Lily Sánchez, from "The Surgeon General Should Stop Telling People to Solve the Loneliness Crisis on Their Own." Current Affairs, 3 May 2023.

#lily sánchez#quote#quotations#community#relationships#liberation theology#catholic worker movement#christian theology#taking action#praxis#dorothy day#democratic socialism#activism#catholicism#personalism#loneliness#individualism

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

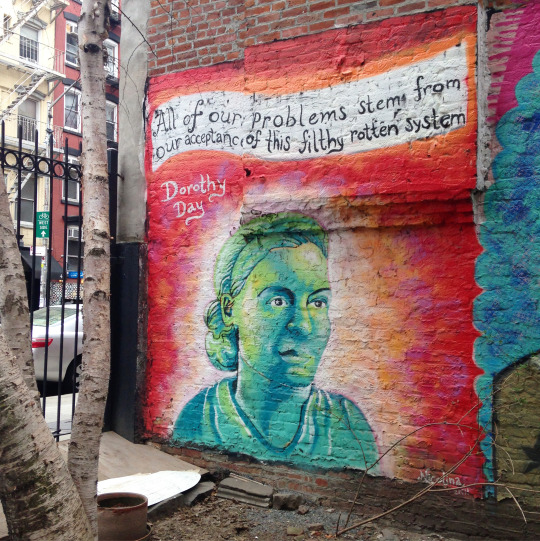

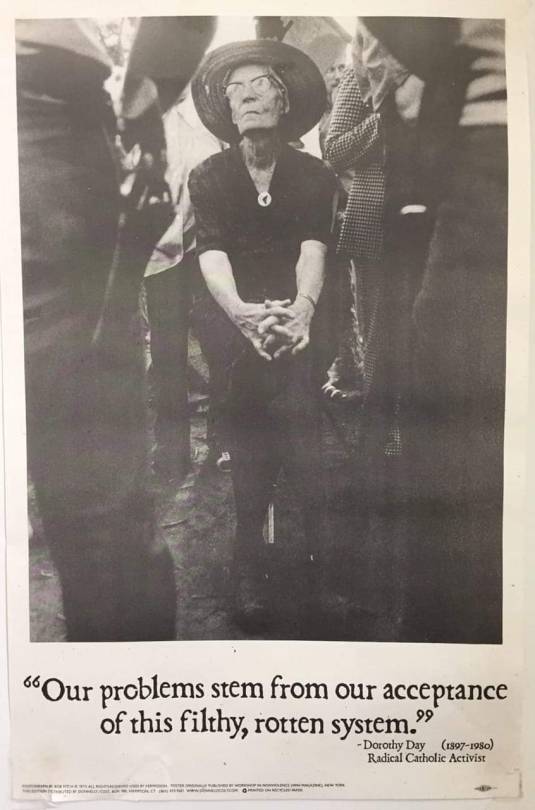

Dorothy Day, born today, November 8th, was an American journalist and social activist who co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement in the early 1930s. This portrait is located in the First Street Community Garden, in NYC.

On November 4th, 2022, the newest vessel in the Staten Island Ferry fleet was named for her, and will enter service in the coming weeks. Day lived on Staten Island for several decades.

Interestingly the quote in the portrait above that reads “All of our problems stem from our acceptance of this filthy, rotten system”, although probably her most famous, may never have been said by her. For more on that debate, this article is pretty informative.

#dorothy day#filthy rotten system#nyc street art#street art#street art nyc#murals#portraits#staten island ferry#catholic worker#catholic worker movement#first street community garden#nyc murals#famous quotes.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thinking a lot about pacifism as a response to living in an empire where violence is directly oppressive vs. violence as a tool for liberation and where I fall in it.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Pro-Life Profile: Gwendolyn Loop

Pro-Life Profile: Gwendolyn Loop

Pro-life Profile is a new series I will be publishing regularly. These brief interviews will highlight pro-life leaders in order to dispel the preconceptions that predominate in the mainstream press and the minds of pro-choice people. I’ll begin with my Vita Institute classmates.

Gwendolyn Loop

Gwendolyn Loop currently lives in Madison, Wisconsin, and is the Outreach Director for New Wave…

View On WordPress

#Abortion#Catholic Worker Movement#consistent ethic of life#New Wave Feminists#Notre Dame University#pro-choice#pro-life#Pro-life Profile#Vita Institute

0 notes

Quote

But living in community is saving Ammon. He is learning not to give the ready answer to every problem, not to be surprised at criticism, at the nagging that goes with community life. He is learning to recognize that all men have their various talents, physical, mental and spiritual. That the vocation of one is not the vocation of all.

Dorothy Day on her friend, at the time a fellow-Catholic Worker and always an activist, Ammon Hennacy, who later of a heart attack that came while picketing the Death Penalty in Salt Lake City.

#I feel like day's descriptions of her non-catholic friends are most revealing#like obviously in this passage he's still catholic#but it's one of the few sections in which she admits to her own critical thoughts on the church#but also it sort of shows why Catholicism and the Catholic worker movement might appeal to her so#in that it couldn't really support the arrogance or singular personalities that flourish in revolutionary spaces#dorothy day#by little and by little#ammon hennacy

0 notes

Text

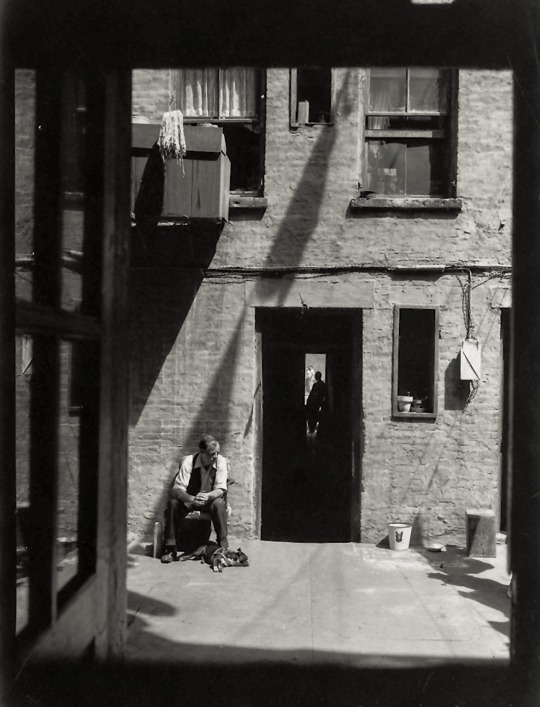

The Catholic worker movement, St. Joseph’s House, ca. 1939 - by Aaron Siskind (1903 - 1991), American

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

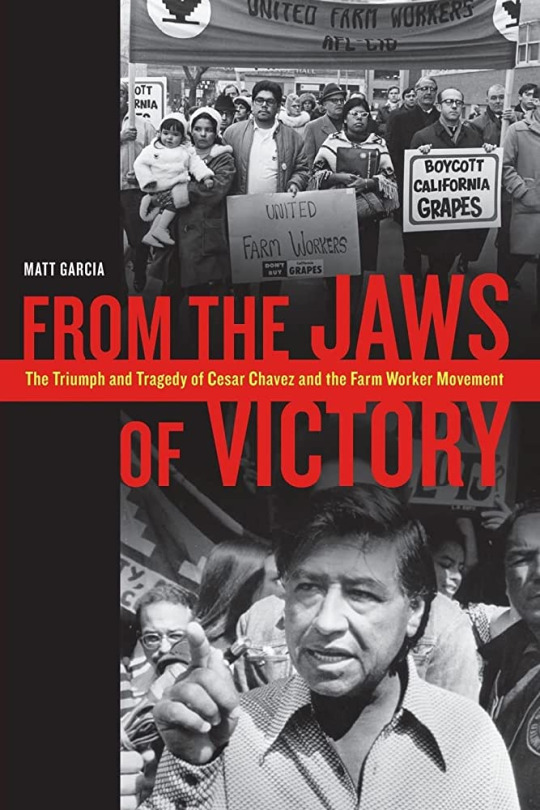

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

#history#u.s history#labor history#ufw#united farm workers#cesar chavez#dolores huerta#trade unions#social history#social movements#unions

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

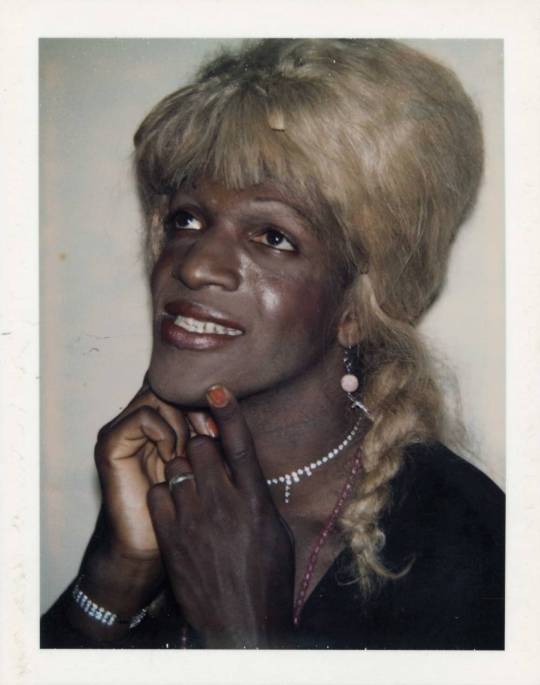

Celebrating Black Queer Icons:

Marsha "Pay It No Mind" Johnson

Johnson was born August 24, 1945. A drag queen and sex worker, after moving to New York City from Elizabeth, New Jersey, Johnson is probably best known for participation in Queer Liberation and AIDS activism from 1969 until her death in 1992. While often associated with transgender women, Johnson self identified as gay, a transvestite, and a queen and actively distinguished her identity from the contemporary transsexual community. As for Johnson's gender? Well, pay it no mind. Johnson's activism began in 1969 after being involved in the Stonewall Inn Riots. She is often attributed as being in the riot's vanguard, alongside Zazu Nova and Jackie Hormona. Johnson would later go on to deny this, and is quoted as saying she did not arrive until after the riots had already started. Johnson would later go on to join the Gay Liberation Front and co-found STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), with Silvia Rivera. STAR would open the STAR House in 1970, which acted as a home for gay and trans homeless youths. In 1973 Johnson and Rivera were both temporarily banned by a gay/lesbian committee, from participating in pride parades, because it was said queens were giving the movement "a bad name". This did not deter Johnson. Starting in 1980 Johnson began living with fellow activist, Randy Wicker, and his partner. Johnson, who was HIV positive, would later become Wicker's partner's caregiver as they became terminally ill due to AIDS. After visiting Wicker's partner in the hospital Johnson became dedicated to spending time with AIDS patients and engaged in street actions with groups like ACT UP. Johnson was a deeply religious person throughout her life. Primarily Catholic, Johnson was said to have a very direct and personal relationship with divinity. On July 6, 1992, Johnson's body was found in the Hudson River. Johnson was cremated and after a march down 7th Avenue her ashes were spread in the Hudson. While initially ruled a suicide by the NYPD, this is highly contested to this day, with good reason. In 2002 Johnson's death was reclassified as Undetermined, and efforts in 2012 and 2016 have seen moderate success in getting the case reopened and re-investigated.

In the wake of her death Marsha P Johnson has become a nigh universal icon in queer communities and seemed like a good starting point for Black History Month. Moving forward I hope to focus on people less known, at least in melanin deficient circles. In a perfect world this would be daily, but I sadly don't have the spoons for it. I will effort to post at least 2-3 of these each week and have a list sufficient enough to carry me through February, and a little beyond. I plan on doing Willmer Broadnax next and have a list going that should cover at least the month of February, and hopefully beyond. Corrections and suggestions are welcome and much desired.

#celebrating black queer icons#black history#black history month#black history is queer history#black history is american history#marsha p johnson#marsha pay it no mind johnson#gay liberation front#street transvestite action revolutionaries#STAR Home#stonewall

315 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your pinned post allows the beatified so here is my vote for bestie Dorothy Day. She’s a Servant of God and i believe wholeheartedly she’s going to be canonised soon. Anti-capitalism, feminism, anarchism, and she was still getting arrested in the name of civil disobedience when she was 75!! The people of the Catholic Saint Tournament love St Oscar Romero so I think they must love her too.

YESSSSSS HOORAY FOR BESTIE DOROTHY DAY

She's on the beatified list and doing REALLY well!

Yay for Dorothy Day! Yay for the Catholic Worker Movement! Yay for ladies getting arrested for speaking their minds!

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy birthday, Ammon Hennacy! (July 23, 1893)

An influential Catholic anarchist and pacifist, Ammon Hennacy was involved in left-wing politics from a young age as a member of the Socialist Party of America. Resisting the draft in World War I, Hennacy was imprisoned alongside other socialists including leading socialist Eugene Debs. While in prison he came to embrace anarchism and pacifism, and after his release spent time wandering, learning, and organizing. He became involved with the Catholic Worker movement, and in 1961 moved to Salt Lake City, organizing the Joe Hill House of Hospitality. While there, Hennacy continued his activism while also mentoring younger anarchists including folksinger Utah Phillips. Hennacy refused to pay taxes to fund war and protested against the death penalty many times throughout his life, among other actions. He died in Salt Lake City in 1970.

"Your damn laws! The good people don't need them, and the bad people don't obey them."

91 notes

·

View notes