#character: nina mccartney

Text

I cannot express how much Badalamenti’s collaborations with David Lynch meant to me. I listened to the Twin Peaks soundtrack over and over for years, and I had a VHS copy of Industrial Symphony No. 5 that I treasured but ultimately lost.

He changed the way I thought about music in film, largely by making me think about it at all… despite the emphasis that people like John Carpenter and Francis Ford Coppola placed on music, nothing about the audio ever moved me in their films. But Badalamenti’s music was an invisible, omnipresent character in every scene, either lurking at the margins or defining the rhythms of the characters we could see.

It’s impossible to watch Audrey Horne sway or walk around without hearing Freshly Squeezed. It’s impossible to see Sheryl Lee’s face without hearing Laura Palmer’s Theme.

And of course, this is doubly sad because we also lost Julee Cruise a few months back. And, I mean… The Nightingale is everything.

youtube

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Paul says he doesn't write autobiographically yet the lonely, single pigeon or seagull is him. But it can't be because he was happy in his marriage with Linda. Was he writing fictional autobiographical lyrics? I'm lost. Funny how this song came out right around the time that Yoko chucked John out and sent him on his Lost Weekend. Shame he didn't include Little Lamb Dragonfly from the same album in his Lyrics set. More about lonely nights and missing someone. Sometimes a lamb isn't just a lamb.

Hey there, dear anon!

Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts about this excerpt; it sure is an interesting one. For reference, here’s the quote in question, from the ‘Single Pigeon’ entry on Paul’s new book:

I had seen a single pigeon, just pecking around – a blue-grey pigeon on its own near some railings — and I thought the combination of those words was quite winning: ‘single pigeon’. I began to think about why the pigeon might be single. The minute you decide to make up a story about a pigeon, it’s not just a pigeon. It’s a character in a play. It’s a guy who’s had an argument with his girl the night before, and he’s got chucked out of the house. So here he is. He’s single now. All because of the ‘Sunday morning fight about Saturday night’.

Second verses are always interesting because you’re going somewhere else but you want to retain the feeling of the first verse. Now that I’ve established the single pigeon, the second verse introduces a ‘single seagull’ – another character in my little play. I’d often see a seagull gliding over Regent’s Park canal, but it’s also possible he flew in from Chekhov. The seagull in Chekhov’s play isn’t just a seagull but a symbol of a character, Konstantin, and his relationship to Nina.

The idea that the protagonist of the song is ‘a lot like you’ suggests that he, too, has been chucked out. He’s relating to the pigeon and seagull because he, too, has been turfed out into the cold morning rain. So, I’ve changed it from being just an ornithological observation to a representation of me. That pigeon is me, or that seagull is me, or a version of me.

The irony is that this song was written at a time when I was actually very happy in my personal life. People listening to the song might have recognised that the corner of my mouth was raised ever so slightly in a smile because my relationship with Linda was a very happy one. That’s why it was so lovely to have her singing backup on ‘Me too / I’m a lot like you’.

I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again: a lot of songwriters draw merely on their day-to-day autobiographical thoughts, but I like to take flights of fancy. That’s one of the great things about being an artist of any kind. I like songs and poetry that take off in unexpected ways.

— Paul McCartney, in The Lyrics (2021).

The process of making The Lyrics has been interesting in part for how it took Paul on a journey of close reading his own work. Something that Paul ‘I don’t examine myself that way’ McCartney would probably not have done unprompted. But now, with the safety of distance and time, it became an intriguing exercise:

Over time I came to see each song as a new puzzle. It would illuminate something that was important in my life at that moment, though the meanings are not always obvious on the surface. Fans or readers, or even critics, who really want to learn more about my life should read my lyrics, which might reveal more than any single book about The Beatles could do. Yet until my brother-in-law, friend and advisor, John Eastman, and my publisher, Bob Weil, provided the initial encouragement to do this book in 2015, I felt that the process of going over the hundreds of lyrics, some that I wrote in my teens, felt too cumbersome if not a bit too indulgent. It was a luxury of time I could not afford. I had always directed all my creative energies into the music. I would worry about the interior meanings, if I worried at all, only later. But once Paul Muldoon and I started discussing the origins and influences of all these songs, I became aware that delving into the lyrics of my songs could be a useful and revealing exploration.

[...]

I never thought I would want to analyse these lyrics, many from back in the 1960s and ’70s. Many of them I hadn’t thought about in years, and many I hadn’t played in concert for decades. But with Paul as my sounding board, it became a challenge – and a very pleasant one – to revisit the songs and pick them apart, to discover patterns that I never knew were there.

The act of writing a song is a unique experience, unlike anything else I know. You have to be in the right mood and start with a clear mind. You must trust your initial feelings because at the beginning you don’t really know where you’re going. Conversations with Paul were much the same. The only thing we knew in advance of each meeting was which songs we would be discussing; everything else was free rein. Inevitably, long-dormant memories were stirred up, and new meanings and patterns suddenly emerged.

— Paul McCartney, in The Lyrics (2021).

So now that Paul is willing to look, he starts recognizing himself and his life in a lot of his lyrics. And that’s how he comes to say “that pigeon is me, or that seagull is me, or a version of me”.

As John used to say:

I think everything that comes out of the songs – even Paul’s songs now, which are apparently about nothing – […] shows you everything about yourself.

— John Lennon (August 1980).

But what it shows may not always be literal and probably difficult to gauge for someone looking in from the outside, with incomplete knowledge of the situation.

So it can be both true that Paul’s feelings and experiences came out in the song, and that they weren’t necessarily about his marriage with Linda. Paul says that “he’s relating to the pigeon and seagull because he, too, has been turfed out into the cold morning rain.” This could be referring to a past experience, at another time and with another relationship. And even then, it could have been either being literally thrown out or more metaphorically.

But let’s look at the second verse:

Single seagull gliding over / Regent’s Park canal / Do you need a pal for a minute or two? / You do? / Me too

It’s fascinating that Paul brings up The Seagull (1895), Anton Chekhov’s subtext-filled play about the unrequited love and artistic struggles of its four main characters: the famous story writer Boris Trigorin, the ingenue Nina, the fading actress Irina Arkadina, and her son the playwright Konstantin Treplev. Basically, Trigorin and Arkadina are lovers, Nina likes Trigorin and Konstantin like Nina.

The seagull is a recurrent symbol throughout the play, as Nina is compared to one repeatedly, with morphing connotations. At one point, Konstantin gifts her with a seagull he has shot, which horrifies her. Trigorin later sees this and muses:

The plot for the short story: a young girl lives all her life on the shore of a lake. She loves the lake, like a gull, and she's happy and free, like a gull. But a man arrives by chance, and when he sees her, he destroys her, out of sheer boredom. Like this gull.

I wonder if Paul brought it up as just an example of another symbolic seagull, or if he feels some of Chekov’s seagull’s symbolism carries over to his own work. If so, it’s curious that Paul interpretes the seagull as “a symbol of a character, Konstantin, and his relationship to Nina”, when normally Nina’s the one that’s compared to the seagull. But after all, it is Konstantin and not Nina who ends up shot dead (and by his own hand again).

But getting out of the weeds and back to Paul’s song, the line “Do you need a pal for a minute or two?” could be read as more obviously autobiographical. ‘Single Pigeon’ was after all written around the same time as ‘Best Friend’, one of his songs from this period more widely believed to be about John. ‘Single Pigeon’ was first recorded in March 1972, and ‘Best Friend’ performed over the Wings European tour, in the summer of 1972. So you are right that the release more or less coincided with John’s separation from Yoko in 1973, though the song seems to predate that (the 1972 version is already almost complete).

Regarding ‘Little Lamb Dragonfly’, I share your sorrow that it’s not featured in The Lyrics. It’s one of my favorites of his, and one of the few that has really gotten me sobbing on occasion. I don’t know, it hits me more than even ‘Dear Friend’ does. These two are also contemporaries, by the way! The ‘Dear Friend’ home demos are believed to date back to circa 1970 and the first known version of ‘Little Lamb Dragonfly’ was recorded in November 1970, during the RAM sessions. [This would make them predate Imagine (September 1971) and, at least for ‘Little Lamb Dragonfly’, the Rolling Stone interview, AKA Lennon Remembers (January 1971).]

But yeah, I completely agree with you that sometimes a lamb’s not just a lamb, and dragonfly’s not just a dragonfly, a seagull’s not just a seagull and a pigeon’s not just a pigeon.

That said, I also empathize with Paul when he has difficulty pointing out what they are instead. He seems to have a very intuitive approach to songwriting (and life in general) and an unwillingness to make things heavy by reflecting on them too deeply. It’s only now, with almost half a century between himself and those events, that he’s plunging back into those feelings (and the consequences of stirring up those “long-dormant memories” are perceptible in book). So this new analysis will inevitably be colored by everything that happened since. And this is not at all a bad thing. But I just want us to keep in mind that this Paul interpreting his lyrics now is not necessarily the same as the Paul who first wrote them. And it’s not that one is truer than the other. But rather, this new insight is probably more informative of his state now (and potentially of what lied beneath the surface then) than what his intentions were at the time of writing these songs.

All of this to say that most of his lyrics are probably consciously fictional and subconsciously autobiographical.

Irrespective of this, I truly applaud Paul’s courage to let both us and him peer inside himself. And I appreciate the chance you’ve given me to reflect more on all of this!

#asks me why#the beatles#paul mccartney#John Lennon#Single Pigeon#The Lyrics#The Seagull#Anton Chekhov#best friend#Little Lamb Dragonfly#Dear Friend#Imagine (album)#Paul Muldoon#songwriting is like psychiatry#tell me why why why do you make me so sad so sad#when you're the best friend that i have ever had#1970#1972#meta#my stuff

42 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lylah Cullman *Supporting Character

Voice Claim: (Rachel Bilson) https://youtu.be/kUOtDRy7DWs?t=100

Partner(s): None

Parents: Andy & River.

Kids: None.

Siblings: Willow, Sam, Oscar, Aishlynn, Annie, Aedan, Liv and Juniper.

Age: Immortal, but translates into early 20′s

Birthday: May 11.

Height: 163cm

Body type: Skinny.

Eye color: Very light green/blue

Classification: Immortal/supernatural.

Known powers: Botanical healing (healing both botanical matter, and also healing humans/animals through botanical matter)

About:

~ Quiet, Elegant, Friendly, Helpful, Kind, Fair, Creative, Honest, Graceful, Compassionate, Cheerful, Gentle, Calm, Positive, Echo Friendly, Free Spirited, Supportive, Shy, Sweet, Artistic, Nurturing, Hopeful, Daydreamer, Humble, Feminine, Loving, Patient, Wholesome, Polite and Generous.

~ Nature is her closest friend.

~ Demisexual.

~ Has long wavy blonde hair.

~ Is a virgin and proud of it.

~ Saves herself for marriage.

~ Wants a big family with lots of kids.

~ Very family oriented.

~ Can be a bit awkward and insecure.

~ Is a phenomenal cook.

~ Is very skilled at drawing and painting.

~ Lives with her sisters Liv & Joon.

~ Plays piano, guitar, violin, harp, flute and harmonica.

~ Has never had alcohol.

~ Enjoys stargazing.

~ Smells like white/pale pink roses and Daisies.

~ Is actively speaking against bullying, animal abuse, child abuse, slavery and environmental issues.

~ Is quite handy at sewing.

~ Very skilled at writing, and hopes to be able to get published in the future.

~ Wants to become a children’s nurse or doctor.

~ Doesn’t like/trust technology.

~ Dislikes rude people, most people in power and politics.

~ Loves her family, her friends, animals, kids, nature, cooking, baking, traveling, meeting new cultures, learning, reading, writing, drawing/painting, learning new instruments, poetry, flowers, sun, spring, fruits, berries, cake icing, whipped cream, running on fields, daydreaming, laying on a field watching the clouds, fresh lemonade, politeness and kindness.

~ Is a bit of a picky eater.

~ Dresses very elegant and feminine, mostly in white or pale colors.

~ Doesn’t hate.

Lylah’s tag

Lylah’s house/home

Lylah’s moodboard

Handwriting/ask answer pic:

One Gif to describe her:

One song to describe her: Katie Melua - Wonderful Life

Personal play list:

1. WILD - Here We Go

2. Nina Simone - Feeling Good

3. Janis Joplin - Maybe

4. Tracy Chapman - Give Me One Reason

5. The Beatles - Let It Be

6. Paul McCartney - Maybe I'm Amazed

7. Tracy Chapman - All that you have is your soul

8. Judith Hill - You Shook Me All Night Long - AC/DC - FUNK cover

9. Tom Speight - Willow Tree

10. Leo Stannard x Frances - Gravity

11. The Beatles - Eleanor Rigby

12. Judy Garland - Over The Rainbow

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Defending the Duke: David Bowie’s “problematic” actions debunked

You’d think that after two years people would have figured it out by now, and yet here we are. Alright let’s get started.

“David Bowie was a sexual predator.”

TW: CSA, statutory rape, rape

This claim originated from an interview with former groupie Lori Mattix of the “Baby Groupie” scene of the 1970s that was republished on The Thrillist the day after David’s death, where she claimed she lost her virginity to him in 1973 when she was 15 years old and he was 26. Additionally, she claimed that she kept seeing him over ten years, however this causes a problem with consistency because David’s personal life was scrutinized more than the average rock star (most likely because of him coming out as bisexual), and the two were never photographed together unlike Mattix’s relationships with other rock stars during the 1970s. More problems with the consistency of her claims include that in some interviews she said she lost her virginity to David and in others she said she had her first time with Jimmy Page of Led Zeppelin, and certain circumstances that contradict her side of the story (or stories).

For example, in an 1985 interview with Stephen Davis, she stated that she had her first time with Jimmy Page in 1972 while the band was in California for their summer tour. She later said that she was having sex with David before Page. This provides an inconsistency because David’s Ziggy Stardust tour came to California in October 1972, months after Led Zeppelin’s summer tour. In a later interview, which was made available online in 2009, she said she was a virgin when she met Page.

In an 1986 interview with Peter Gillman, she said that while eating at the Rainbow Bar in March 1973 with her friend and fellow groupie, the late Sable Starr, David spotted her and got his bodyguard to invite her to his suite, and she accepted. She said they had sex for five or six hours and she convinced him to let Starr join them, and all fell asleep afterwards, and the two snuck out before David’s then-wife Angie would arrive. In a different interview with Paul Trynka however, she said that in October 1972 she and Starr snuck into his Beverly Hilton suite and convinced a tired David to sleep with them before they snuck out without being seen.

In the Thrillist interview, Mattix said David approached her in October 1972, but she rejected him. When he came back in March 1973, he called her and invited her to dinner. John Lennon and Yoko Ono joined them for dinner before she and David left for his Beverly Hilton suite, they and Sable Starr had a threesome, and Angie walked in on them the next morning. In addition to her earlier interviews contradicting this so-called recollection, David didn’t meet Lennon until September 1974 when they were introduced to each other by Elizabeth Taylor at one of her parties. And David stayed at the Hyatt hotel in March 1973, not the Beverly Hilton.

In the same interview, she said she attended a recording session in 1975 when she was 17, where John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, Mick Jagger, and a bunch of other artists were there, and she slept with Jagger after the session wrapped up. Another inconsistency with this is that the only time Lennon and McCartney jammed together after the Beatles broke up was the year before, in march 1974. Not only that, there is no evidence to suggest that Jagger was at that session in 1975.

Mattix’s claims were further contradicted by Pamela Des Barnes, another former groupie who was in her 20s during the 1970s (one year younger than David), in her memoir, I’m with the Band. Des Barnes was in a relationship with Jimmy Page by 1972, however she ended their relationship and moved in with Frank and Gail Zappa and worked for them as a nanny in February 1972, because he was sleeping with Mattix and leaving Des Barnes in the dust. The breakup and move happened a month before David’s tour came to Long Beach, when Mattix claims she lost her virginity to him.

(Additionally, along with changing her story about it many times including how old she was when it happened, she said once how she met him in LA in 1973 five months beforehand, but the his tour didn’t have a stop in California at that point, and the last time he really visited LA at that point was 1972. She said it happened at the Beverly Hilton in 1973, but the only time he is photographed there is in 1972.)

Sources: X X

In 1987, he was falsely accused of rape by 30 year-old Wanda Nichols who claimed he exposed her to AIDS. They were both tested and both their results were negative. He was cleared of the charges. (x) (x)

Not to mention that this kind of behavior sounds completely out of his character. On one of his later tours, he threatened to fire his drummer for directing teenage girls to his hotel room (x), according to one of the commentaries of the 1986 Jim Henson film Labyrinth, a kiss scene was originally written but he refused to do it because his co-star Jennifer Connelly was 14 at the time (x), and when he was in the band Tin Machine he wrote the song “Shopping for Girls” which is about and brings awareness to child prostitution in Thailand (x).

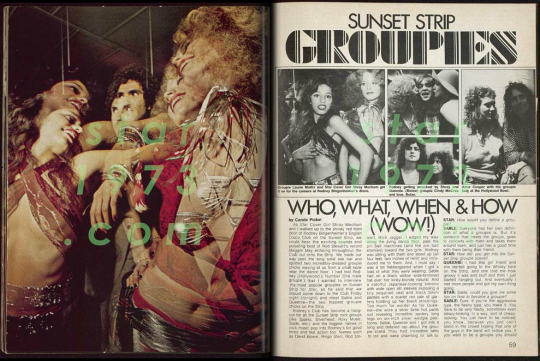

Now with that said, this isn’t to say that the “Baby Groupie” scene never happened. Although Mattix obviously lied about him, there are perverts in the rock music industry like Kim Fowley and Gary Glitter, and the whole Baby Groupie scene and the idea of teens having sex with adults were being encouraged in the 70s, according to the June 1973 issue (pages 59–61) of Star Magazine

and this quiz in the March 1973 issue (pages 62–63) of Star to see if you have what it takes to make an older guy like you.

They were encouraging these young girls to go out, dress up and wear makeup to make themselves look older, act older by smoking and drinking, carry fake IDs, and lie about their ages. Even though I don’t trust her word, I do feel really sorry for her for being manipulated by disgusting men and bad influences in the 70s into thinking this was okay. It’s especially horrid once you consider how rape culture was at a high point in the 70′s and how a lot of disgusting things were being romanticized and encouraged.

(The Runaways promotional poster from the 70s with bodice, ass and crotch shots of the then teenage girls and a then 24 year old Tony Parsons calling them nymphets and saying the “young and extremely horny teenage females was a bonus”)

(Love’s Baby Soft Perfume ad from 1975)

Disgusting. Moving on.

“David Bowie was a racist and a n@zi sympathizer.”

This claim came from Bowie’s comments in 1976 under his persona the Thin White Duke that supposedly supported fascism. However, at this time his diet consisted only of milk, red peppers and cocaine, and he really was out of his mind at that time because he was at the height of his cocaine addiction, when he was convinced Jimmy Page was trying to steal his soul, that witches were trying to steal his semen, and wanted an exorcism done on his swimming pool because he believed Satan lived in it. When he was getting clean and coming back to his senses, he became horrified and disgusted of how his image was being used by neo-nazis. With all that crazy shit and more, do you honestly think he meant all the garbage he said? He was so out of it, he barely had any recollection of recording the album for Christ’s sake. Also, around this time he was photographed supposedly giving a n*zi salute but he was really just waving hello to his fans. He retracted and apologized for his statements in a 1977 interview for Melody Maker and later called the Duke an “ogre,” and again looked back at that period with unkind words in 1983.

Additionally, while making his blue-eyed soul album Young Americans, he gave credit to where credit was due, saying, “It’s the squashed remains of ethnic music as it survives in the age of Muzak rock, written and sung by a white limey,” and collaborating with Ava Cherry, Luther Vandross, and Carlos Alormar to give the album an authentic soul sound. (x) (x) He also encouraged Nina Simone to continue performing, and a huge supporter of Tina Turner’s career. (x)

David wrote many songs and videos with anti-nazi and anti-racism themes. The “China Girl” video serves to parody Asian female stereotypes as well as to protest colonization by making the lyrics in the POV of a colonizer to show how fucked up the mindset is, and the video, as well as the Let’s Dance video, were made as statements against racism. The Let’s Dance video in particular was very influential in Australia. David even openly criticized MTV for not playing videos from black artists. The first Tin Machine album had a direct anti-fascism and anti-neo n*zi stance. He continued to protest racism throughout his career.

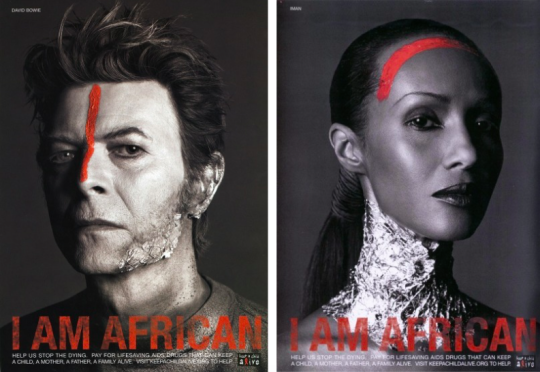

And also marrying Iman. Yes, yes I know. It’s true that many white celebrities who enter relationships with black partners often do it either as a front or to satisfy some eldritch fetish, and usually try to start relationships with black people who are either naive or ignorant (like, “my black boyfriend said it’s okay” and shit like that). *cough cough* K*rdashians *cough cough* But here’s the thing, this is Iman Abdulmajid we’re talking about here. This is the same woman who started her own cosmetic company for women of color, protested the lack of black models on runways with Naomi Campbell and Bethann Hardison, and supports many charities and human rights causes. Just take a look at her Twitter page. She is absolutely not ignorant or naive. She and David worked on many charitable activities and events together, including her I Am African campaign.

And I know what you’re thinking, he could have used his charity support for publicity or as a front like many celebrities in the past. *cough cough Sp*cey, W*instein, H*ffman *cough cough* But when Iman was given a Voice Award at the Save The Child’s Illumination Gala in 2016, she dedicated the award to him, saying “David was also a staunch supporter of human rights and devoted an innumerable amount of time and resources, which he chose to do anonymously. [...] I share this award with him, knowing that the fire in him lit the fire in me, and vice versa. [...] Good partnerships have a habit of doing that.”

And finally,

“David Bowie was never bisexual.”

(X)

Okay, but let’s talk serious. This claim is more specifically saying he used bisexuality as shock value and he isn’t a good icon for the LGBT community. In 1983 he called his coming out a “mistake,”said he was only experimenting, and called himself a “closet heterosexual,” in 1993. However, there are things to heavily consider. In the 1980s he was going through a depressive period in his life with alcohol problems. In addition, he felt that his sexuality overshadowed his music in America and and wanted to change his image to appeal to a more mainstream audience (to make his career survive during that time when homophobia was on the rise so he had to shield himself; may I remind you of when he was falsely accused of giving Wanda Nichols AIDS, not to mention dealing with ignorant interviewers acting so clueless over such a simple concept). In 1993, Tin Machine failed to revive his career after the critical failures of his last two solo albums of the late 1980s, of course those problems continued. And if you think I’m reaching, take a look at what he said in an interview for Blender in 2002.

You once said that saying you were bisexual was "the biggest mistake I ever made." Do you still believe that?

WHOODAAMANN, SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA

Interesting. [Long pause] I don't think it was a mistake in Europe, but it was a lot tougher in America. I had no problem with people knowing I was bisexual. But I had no inclination to hold any banners or be a representative of any group of people. I knew what I wanted to be, which was a songwriter and a performer, and I felt that [bisexuality] became my headline over here for so long. America is a very puritanical place, and I think it stood in the way of so much I wanted to do. (x)

And it’s not like his impact on the LGBT+ community is nonexistent.

He was bi and a damned good LGBT icon.

And with that said, just because his most high-profile relationships were with women that doesn’t mean he wasn’t bi. A bi person can have a preference towards one sex or gender but that does not in any way diminish their attraction to the other sex or genders. There are plenty of examples of bisexual people who enter monogamous relationships with people of the opposite sex. That doesn’t make them any less bi.

Reflections & Conclusion

One of the biggest problems I see when the Bowie/Classic rock fandom talk about this is how they completely derail the conversation to how “feminism and sjw culture is toxic and spreads lies” and other dumb shit like that. You can’t blame an entire movement for trouble caused by a few assholes on a site like this. This is Tumblr, remember? You can’t expect people to be perfect to know everything about everyone famous. Newsflash: I’ve made mistakes too. There are many more people who make up for their mistakes than you give credit for. It should only be a real problem if they refuse to believe you or ignore you after you give them solid corrections. Chances are the people like that have generally shitty views or have something to hide (like every TERF blog on here). It also upsets me when people, who I will not name (you know who you are) defend him by slut-shaming Lori Mattix or the other groupies (I won’t say why, I hope you can figure that out for yourselves).

So in conclusion, don’t believe everything you read, be patient with people but don’t take shit from anyone, don’t use people screwing up as an excuse to spread your own ignorance, stay away from books written about David by Lesley-Ann Jones, Dylan Jones, and “Backstage Passes” by Angie Bowie, and if you have written a callout post about David Bowie, don’t ever fucking do that shit again. Have a nice day.

926 notes

·

View notes

Photo

GOOD MUSIC MASTERPOST: 8 playlists. No characters of themes or overarching aesthetics, just 8 sets of 20 maybe-not-so-well-known great songs from several countries and in several languages.

SIMPLE BUT BRILLIANT MELODIES: 20 songs that show that sometimes with music, less is more. [LISTEN]

1. CHARLES AZNAVOUR la bohême 2. LUIZ GONZAGA ana rosa 3. EDITH PIAF sous le ciel de paris 4. THE WHITE BUFFALO oh darlin’ what have I done 5. BARBARA la joconde 6. ANDY WILLIAMS speak softly love 7. TOM ZÉ menina jesus 8. CHARLES TRÉNET la mer 9. ADONIRAN BARBOSA o trem das onze 10. ELLA FITZGERALD & THE INK SPOTS I’m making believe 11. PAUL MCCARTNEY my valentine 12. MARLENE DIETRICH lili marleen 13. RENATO CAROSONE maruzzella 14. HENRI SALVADOR marchand de sable 15. BOBBY VINTON blue velvet 16. CHATS SAUVAGES & DICK RIVERS derniers baisers 17. LUIZ GONZAGA asa branca 18. BORIS VIAN le déserteur 19. CARTOLA divina dama 20. HANS ZIMMER deliver us (The Prince of Egypt OST)

THE ART OF WRITING GOOD LYRICS: 20 songs that, either through wordplay or through verbal punches to the gut, prove that it takes an artist to write good lyrics. [LISTEN]

1. DANNY SCHMIDT this too shall pass 2. REGINA SPEKTOR pavlov’s daughter 3. CHICO BUARQUE geni e o zepelim 4. BOB MARLEY redemption song 5. TOM WAITS walking spanish 6. LENINE todas elas juntas num só ser 7. AGAINST ME! haunting haunted haunts 8. ARCTIC MONKEYS arabella 9. CAETANO VELOSO & GILBERTO GIL baião atemporal 10. JACQUES BREL les bourgeois 11. JANELLE MONÁE mushrooms & roses 12. ELIS REGINA o bêbado e a equilibrista 13. DAN DEACON when i was done dying 14. TWENTY ONE PILOTS car radio 15. JUSTIN CROSS drink the water 16. ADRIANA CALCANHOTO saiba 17. BORIS VIAN le déserteur 18. NICK DRAKE day is done 19. ELIS REGINA & ADONIRAN BARBOSA tiro ao álvaro 20. FIONN REGAN 100 acres of sycamore

TOE TAPPING GOOD: 20 songs with a great sense of rhythm that make you tap your feet and dance. [LISTEN]

1. MAX ROACH the drum also waltzes 2. BAABA MAAL fulani rock 3. MAVIS STAPLES down in mississippi 4. EMIR KUSTURICA djinji djinji bubamara 5. AGAINST ME! animal 6. JANELLE MONÁE sincerely, jane 7. BAMBOLEO ya no hace falta 8. DOM UM ROMÃO escravos de jo 9. OTIS REDDING sitting on the dock of the bay 10. SON HOUSE john the revelator 11. JACQUES BREL la valse à mille temps 12. BOMBINO tar hani 13. ZZ TOP la grange 14. ABRAHAM INC fred the tzadik 15. LA TROBA KUNG-FÚ petit rumbero 17. BO DIDDLEY, LITTLE WALTER & MUDDY WATERS my babe 18. THE CAT EMPIRE the wine song 19. SONGHOY BLUES soubour 20. PEGGY LEE fever

LAUGHING SONGS: 20 songs that will (hopefully) make you laugh. [LISTEN]

1. SCREAMIN’ JAY HAWKINS constipation blues 2. FRANK ZAPPA he’s so gay 3. UTOPIA mina 4. WITCH DOCTOR ooh eeh ooh ah aah ting tang walla walla bing bang 5. ELECTRIC SIX gay bar 6. KALEIDOSCOPE hesitation blues 7. BILL BAILEY old macdonald 8. BONZO DOG DOO DAH BAND ali baba’s camel 9. BORIS VIAN j’suis snob 10. THE GOONS the raspberry song 11. FOLK UKE motherfucker got fucked up 12. ENA PÁ 2000 colhão colhão 13. ELLA FITZGERALD & LOUIS JORDAN stone cold dead in the market (he had it coming) 14. BONZO DOG DOO DAH BAND hawkeye the gnu 15. RENATO CAROSONE io, mammeta e tu 16. ELIS REGINA alô alô marciano 17. BO BURNHAM straight white man 18. FRANK ZAPPA penguin in bondage 19. BEZERRA DA SILVA sequestraram minha sogra 20. GEORGE MCKELVEY my teenage fallout queen

CRYING SONGS: 20 songs that might make you emotional. [LISTEN]

1. NINA SIMONE stars (Janis Ian cover) 2. EARTHA KITT angelitos negros 3. CLARA ROCKMORE valse sentimentale (Tchaikovsky) 4. ELIS REGINA como nossos pais 5. TOM WAITS i’m your late night evening prostitute 6. ELZA SOARES mulher do fim do mundo 7. TRACY CHAPMAN behind the wall 8. ADONIRAN BARBOSA iracema 9. TWENTY ONE PILOTS neon gravestones 10. HANNAH SZENES eli eli 11. JANELLE MONÁE cold war 12. CAETANO VELOSO & GILBERTO GIL haiti 13. BOB MARLEY redemption song 14. CHRISTIAN SINDING suite im alten stil, op. 10 (adagio) 15. SUFJAN STEVENS john wayne gacy jr. 16. CHARLES AZNAVOUR comme ils disent 17. ERIC CLAPTON tears in heaven 18. JP SIMÕES lenda do homem pássaro 19. AGAINST ME! the ocean 20. CONCHA BUIKA volver, volver

WEIRD BUT GOOD: 20 songs that sound kinda weird. [LISTEN]

1. MR. BUNGLE goodbye sober day 2. FRANK ZAPPA g-spot tornado 3. THE FREE DESIGN bubbles 4. NINA HAGEN african reggae 5. MATMOS family dance 6. SORONPRFBS secure the galactic perimeter 7. EINSTÜRZENDE NEUBAUTEN weil weil weil 8. MAGMA stöah 9. MR. BUNGLE none of them knew they were robots 10. ORNETTE COLEMAN science fiction 11. ANIMAL COLLECTIVE floridada 12. THE VOIDZ qyurryus 13. TEENAGE JESUS AND THE JERKS my eyes 14. BUBBLES bidibodi bidibu 15. KOENJIHYAKKEI nivraym 16. HERMETO PASCOAL quebrando tudo 17. NINA HAGEN naturträne 18. LORI FREEDMAN spasm 19. EDGARD VARÈSE ionisation 20. TALKING HEADS i zimbra

INSTRUMENTAL MASTERPIECES: 20 (mostly) instrumental songs that showcase music as the universal language, capable of moving people without the need for lyrics. [LISTEN]

1. CHARLES MINGUS moanin’ 2. KING CRIMSON discipline 3. CARLA BLEY reactionary tango 4. DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH jazz suite no. 1 (foxtrot) 5. FRANK ZAPPA the gumbo variations 6. QUINCY JONES the pink panther theme (study on Mancini) 7. ERNESTO LECUONA malagueña & andalucia 8. GUSTAV MAHLER symphony no.1 in D major, 3rd movement 9. DAVE BRUBECK take five 10. SUN RA space is the place 11. DJANGO REINHARDT minor swing 12. CAMILLE SAINT-SAËNS aquarium 13. ALICE COLTRANE turiya and ramakrishna 14. GEORGE GERSHWIN rhapsody in blue 15. MILES DAVIS miles runs the voodoo down 16. DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH walktz no. 2 17. MOONDOG & THE LONDON SAXOPHONIC ORCHESTRA bird’s lament 18. RYO FUKUI early summer 19. IBRAHIM MAALOUF lily will soon be a woman 20. FRANZ LISZT magyar fantázia

NICE PIPES!: Just 20 great and iconic voices. [LISTEN]

1. SARAH VAUGHAN broken hearted melody 2. NINA HAGEN personal jesus (Depeche Mode cover) 3. MIRIAM MAKEBA m’bube 4. WOODKID the other side 5. ELLA FITZGERALD hard hearted hannah 6. CONCHA BUIKA mi niña lola 7. POST MODERN JUKEBOX FEAT. AUBREY LOGAN here (Alessia Cara cover) 8. TOM WAITS trampled rose 9. UTE LEMPER lola 10. CHARLES AZNAVOUR la bohême 11. LOTTE LENYA moon of alabama 12. BASIA BULAT little waltz 13. NINA SIMONE feeling good 14. ARNALDO ANTUNES naturalmente naturalmente 15. PEARL BAILEY big spender 16. ZAZ je saute partout 17. JOANNA NEWSOM sapokanikan 18. JP SIMÕES tango do antigamente 19. LHASA DE SELA la celestina 20. PAUL ROBESON joe hill

#jakedotchin#userorynn#mine#fanmix#not really but that's the tag and i'm sticking with it#i know this post is huge and i know nobody cares bc everyone's focused on tumblr dying#but i worked hard on this and i'm gonna put it out there or so help me

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tags:

Games:

Dark Souls — Dark Souls 2 —Dark Souls 3

Characters:

Allfather Lloyd — Anastacia of Astora — Andre of Astora — Artorias the Abysswalker — Bighat Logan — Ceaseless Discharge — Chaos Witch Quelaag — Crossbreed Priscilla — Dark Sun Gwyndolin — Domnhall of Zena — Dragonslayer Ornstein — Executioner Smough — Fair Lady Quelaan — Fina the Fateful — Flann, God of Fire — Griggs of Vinheim — Gwyn, Lord of Cinders — Gwynevere, Princess of Sunlight — Hawkeye Gough — Ingward the Sealer — Kirk, Knight of Thorns — Lady of the Darkling — Laurentius of the Great Swamp — Lautrec of Carim — Lord’s Blade Ciaran — Maneater Mildred — Oscar of Astora — Oswald of Carim — Princess Dusk of Oolacile — Quelana of Izalith — Rhea of Thorolund — Rickert of Vinheim — Shiva of the East — Shiva’s Bodyguard — Sieglinde of Catarina — Solaire of Astora — Trusty Patches — Velka, Goddess of Sin — Witch Beatrice — Witch of Izalith

Alsanna, Queen of Eleum Loyce — Benhart of Jugo — Caffrey, Goddess of Fortune — Caitha, Goddess of Tears — Cale the Cartographer — Carhillion of the Fold — Covetous Demon — Creighton the Wanderer — Duke of Tseldora — Elana, the Squalid Queen — Felkin the Outcast — Grave Warden Agdayne — Hanleth, Goddess of Bliss — Ivory King — Laddersmith Gilligan — Licia of Lindelt — Lonesome Gavlan — Lord Aldia — Lost Sinner — Lucatiel of Mirrah — Magerold of Lanafir — Milibeth — Mytha, the Baneful Queen — Nadalia, Bride of the Ashes — Nahr Alma, God of Blood — Nashandra, Queen of Drangleic — Nehma, Goddess of Love — Old Iron King — Quella, God of Dreams — Raime, Fume Knight — Rosabeth of Melfia — Royal Sorcerer Navlaan — Saint Serreta — Scorpioness Najka — Shanalotte, the Emerald Herald — Sir Alonne — Stone Trader Chloanne — Straid of Olaphis — Sunken King — Targray of the Blue Sentinels — Throne Watcher — Tichy Gren — Velstadt, the Royal Aegis — Vendrick, King of Drangleic — Witch Zullie

Anri of Astora — Company Captain Yorshka — Cornyx of the Great Swamp — Cuculus of the Great Swamp — Dancer of the Boreal Valley — Daughter of Crystal Kriemhild — Dorhys, the Deranged Evangelist — Eleonora — Eygon of Carim — Firekeeper — Gertrude, the Heavenly Daughter — Halflight, Spear of the Church — Hawkwood the Deserter — High Lord Wolnir — Irina of Carim — Lorian, Elder Prince — Lothric, Younger Prince — Nameless King — Oceiros the Consumed King — Orbeck of Vinheim — Painting Woman — Pale Shade of Londor — Pontiff Sulyvahn — Princess Filianore — Queen of Lothric — Ringfinger Leonhard — Rosaria, Mother of Rebirth — Shira, Knightess of Filianore — Shrine Handmaiden — Siegward of Catarina — Sir Vilhelm — Sirris of the Sunless Realms — Sister Friede — Vordt of the Boreal Valley — Witch Karla — Yellowfinger Heysel — Yuria of Londor — Zoey, Desert Pyromancer

Enemies/NPCs

Character Types:

Old Gods — Royals/Nobles — Warriors — Clerics — Mages — Pyromancers — Merchants/Traders — Handmaidens — Blacksmiths/Craftspeople

Colors:

Red — Orange — Yellow — Green — Azure — Blue — Violet — Purple — Pink — Brown — Black — Grey — White — Gold — Silver — Multicolor/Rainbow

Garment Type:

Dresses/Gowns — Coats/Jackets — Headwear — Blouses/Shirts — Skirts — Trousers — Suits — Tunics/Capes — Costumes — Undergarments/Stockings — Jewelry — Footwear — Gloves — Hats — Bags

Designers:

AF Vandevorst — Alex Perry — Alexander McQueen — Ann Demeulemeester — Armani Privé — Ashi Studio — Antonio Berardi — Balmain — Burberry — Chanel — Christian Dior — Christian Lacroix — Dolce & Gabbana — Elie Saab — Emilio Pucci – Galia Lahav — Georges Hobeika — Gucci — Hamda al Fahim — Hermès — House of Dorville — Inbal Dror — Jacques Fath — Jasper Conran — John Galliano — Joseph Helbert — Kosmas Pavlos — Lanvin — Lelia Khashagulgova — Marc Jacobs — Monique Ihuillier — Nina Ricci — Norman Norell — Norman Powell — Paolo Roversi — Paolo Sebastian — Pierre Balmain — Rami Kadi — Ralph & Russo — Reem Acra — Rodarte — Sara Mrad — Sophie Couture — Stella McCartney — Steven Maisel — Svarovski — Teuta Matoshi Duriqi — Tony Ward — Ulyana Sergeenko — Valdrin Sahiti — Versace — Vivetta — Walone — Yiqing Yin — Yolancris — Yves Saint Laurent — Ziad Nakad — Zuhair Murad

Other Sources:

Movies — Tv Shows — Ancient/Historical – Handmade/Artisan — Unknown

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

(PDF) The Character Of Music Genres

Throughout the United States people are obsessed with all forms of music, however have you ever ever questioned which musical genres are most popular during which areas. Americana; the music in regards to the working class. The hopes and goals of the free American individuals. Driving rock that you could hear in bars and stadiums alike. Jazz, rock or classical are terms regularly used to distinguish between different genres" of music. However they is also described as completely different styles". In that sense, style" would denote the more basic and genre" the more specific characteristics of the music concerned. Be that as it might, it's useful to regard genre" as an outline of the social function of music.

As an instance you are in a shop that's enjoying music and you want to know the identify of the tune or who's singing it. Simply hold down the House button on your iOS machine. Inform Siri Shazam this" and bretedments777471.wikidot.com Siri will give you the track title and artist. Warning: you would possibly lose a whole hour to this… Each Noise at As soon as is a one-web page map of playable audio samples for more than 1500 musical genres, from deep tech house to Finnish metallic to easy jazz to geek people to klezmer to deep opera.

In 2017, more DJs took advantage of the one detail that makes their artwork kind truly unique: they'll play anything. Nina Kraviz, regardless of the absurd controversy it as soon as brought on her, continued colouring exterior the strains, be it with a hundred and fifty BPM techno or straight up drum & bass, on the principle stage at EXIT Competition or in room one at Unsound's Lodge Forum. Avalon Emerson, armed with wildly eclectic music on impeccably organized USB sticks, drifted seamlessly from straight four-4 into hip-hop and R&B. On the final morning of Sustain-Launch, PLO Man appeared intent on encompassing as a lot as possible of all the panorama of digital music in one set, with separate chapters devoted to jungle, garage, deep home, dub techno and ambient.

Rock and pop bands use the identical quantity of instrumentation on stage, which is normally two guitars, one set of drums, and one bass guitar. One other similarity is the variety of musicians on stage which includes: vocals, guitar players, bass player, drum participant, and again vocals. The last similarity is the way both type bands perform. Both styles carry out with a robust stage presence, being very energetic on stage. Some examples of bands which might be pop bands and are confused as rock bands are: ‘N Sync, Backstreet Boys, and Justin Bieber.

Music in America is at the moment in an interesting place. The internet has made it easier than ever for artists to release their music for the world to hear, but on the same time it might probably feel like a smaller group of artists is capturing the highest of the charts. Still, with regards to touring exhibits and local scenes rock and nation musicians are serving to to carry followers together all throughout the country. While the charts is likely to be dominated by music that's streamed over telephones and computer systems the local concert venues are filled with people searching for that traditional combination of drums, a guitar, and a singer that can make them really feel something.

Solo: This can be used anytime, ideally after a round or two of refrain and verse, to add just a little jam feel. Used loads in jazz and can really create cool sections in music. When you find yourself thinking of live performance Solo components are always unbelievable, even if it's not in your released monitor. we fell in love with this music, and it's not one thing you typically grow out of, so long as the music evolves with you. and as long as there is a demand, there will likely be like minded folks supplying.

Eminem!? Eminem is amazing. I like to recommend looking into his music. My favourite genres are Various, Grunge, and Rock. Eminem has meaningful music. I am okay with you not liking him, but categorizing him with the others talked about? No. Just. No. Before John Lennon and http://www.audio-transcoder.com Paul McCartney's songwriting partnership turned the dominant drive of ‘60s fashionable music, there was Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, who were a hit-making duo in rock & roll's earliest days. Elvis made their song Hound Dog"—recorded quite a few times by numerous artists as early as 1953—famous in 1956, and when Presley's new film 'Jailhouse Rock' got here out the next year, they had a monitor ready just for him.

Music based upon a rhythm style, which is characterized by regular chops on the backbeat, performed by a rhythm guitarist. Reggae is an African-Caribbean style of music developed on the island of Jamaica and carefully linked to the faith of Rastafarianism (though not universally popular amongst its members). Some school students discover that one of the best music to study by is so-called put up-rock music. It's a numerous genre that includes many bands that focus totally on enjoying instrumental music with none vocals. Nevertheless, some bands do embrace restricted vocals with hard-to-discern lyrics. In consequence, their songs typically present perfect background music for learning since they do not draw quite a lot of consideration to themselves.The effect of various musical styles on serum cortisol levels, blood stress, and heart fee is presently unknown. Yes, we have mentioned this earlier than- however ya'll do not listen so we are going to say it again. What you are calling EDM falls below the umbrella term of electronic dance music - but it surely's not EDM. The rationale why, is that there is no EDM subgenre. Wait, you imply EDM isn't a subgenre of EDM? STUNNING. music a sort of contemporary electronic music that developed in the Nineteen Eighties, changing disco as the most well-liked form of dance music. It combines deep bass sounds with components that are sung or performed on a synthesizer.3. Tone and Intonation. Jazz musicians will be obsessive about their sound and their tone quality, however overall I'd say it's less a precedence than it's within the classical world. Sometimes jazz musicians additionally go for bigger fairly than higher on this regard, for the above-stated causes. this is nowhere close to a whole listing of musical genres… what about witch hop or s3rl… or comfortable hardcore… or future base. was just wanting to level that out… there is approach to much music for anyone but a big group of lots of to listing and research.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Louise Maxwell

Louise Maxwell is an award-winning hair and make-up stylist. Her fresh, naturally beautiful styles feature in campaigns and editorial for fashion brands and publications worldwide. She also styles individuals and creates original looks for weddings and events.

Louise has over 30 years’ experience in the fashion and beauty industry. Her professional expertise spans many years as an art director and educator for beauty brands including L’Oreal, Schwarzkopf and Redken. She has worked on shows and photoshoots across the globe and has twice won the British Hairdressing Awards for her distinctive cutting style.

Inspired by a less-is-more ethos, Louise’s passion is natural beauty with a subtle, sexy edge. Her styles focus on flawless skin and hair, with effortlessly beautiful cuts that require minimal styling. Each look is produced with premium products, including organic and sustainable lines. All draw out an individual’s style to create a feeling of beauty and confidence from within.

Louise’s love of Ibiza brought her to live on the island in 2005. She now works across the Balearics and internationally.

Alongside her individual styling work, Louise has also created the Louise Maxwell Collective, a curated team of expert style, beauty and wellbeing professionals.

Clients

365 Productions, Alana Productions, Amal Clooney, Amanda Wakeley, Amber Le Bon,

Cindy Crawford, Charlotte Tilbury, Clara Paget, David Guetta, Deliciously Sorted, Golshifteh Farahani, Idris Elba, Jack Savoretti, Jade Jagger, Jessica Simon, Jodie Kidd, Loft Studios, Meg Matthews, Melanie Blatt, Natalia Vodianova, Pete Tong, Rosetta Getty, Sarah Brightman, Solomun, Tamara Beckwith, The Shop, Zoe Ball

Editorial

Assouline, Condé Nast Traveller, Company, Glamour NL, Grazia, GQ, InStyle, Le Monde, Marie Claire, Red Magazine, The Sunday Times Style, Vogue

Advertising / PR

Alice Temperley, Barbara Bonner, ba&sh, Chasin’, Chiemsee, Ciroc, David Guetta, De La Vali, Derek Rose London, Essie, Heidi Klein, H&M, Ibiza Rocks, Jerome Dreyfuss, Lara Bohinc, Lily and Lionel, Loewe, Martini, Mimi Holliday, MTV, Nina Ricci, Pacha, Pikes Ibiza, Reiss, Renault, Stella McCartney, The White Company, Vanessa Sposi

Photographers

Alan Sim, Anders Brogaard, Benjamin Wheeler, Bryan Adams, Dan Emmerson, David Titlow, Denis Boulze, Diana Gomez, Gypsy Westwood, Harley Weir, Iain McKell, Jane Mcleish-Kelsey, Jon Compson, Laurie Bartley, Maria Simon, Pascal Chevallier, Phillip R Lopez, Robert Astley Sparke, Steve Emberton, Tim Beddows, Tracey Taylor, Wolfgang Mustain

Testimonials

Gemma Bowman – Founder, Ibiza Wedding

‘We have worked with Louise for several years now and have always found her to be committed, professional and of course very creative. Her relaxed character is a real bonus for potentially nervous brides and her skill and technique as both a hair stylist and make-up artist means that brides look like more polished versions of themselves on the day, which is ultimately what all brides (and grooms!) are looking for.’

For more details on our products and services, please feel free to visit us at: beauty artist, artistic make up, the makeup artist, make up and hair artist & make up and hair stylist.

0 notes

Text

Q&A: Nina Nesbitt Might Be The Britney Spears of our Generation

Already off to an impressive start to 2018, which includes numerous sold-out tour dates and amassing upwards of 100 million streams to date, Scottish singer-songwriter Nina Nesbitt is just getting started. Nesbitt’s vibrant voice is derived from her musical influences Britney Spears and Whitney Houston, and her rapid growth as an artist only further contributes to her confident classic pop style. Her flair for catchy pop and R&B blended with her own confessional songwriting has gathered fans such as Chloe Grace Moretz and Taylor Swift, who included ‘The Best You Had’ on her “Favorite Songs Playlist.”

Earlier this year, Nina Nesbitt partnered with Spotify for their Louder Together program to record the first ever collaborative Spotify Single Original called “Psychopath” with fellow Ones To Watch Sasha Sloan and Charlotte Lawrence.

Fresh off her summer tour supporting Jesse McCartney, Nina released a brand new single, “Loyal To Me,” which was inspired by the “independent-women spirit of the 90s and is a self-help to dating.” She plans on releasing a full-length album in early 2019.

Ones to Watch recently chatted with Nina Nesbitt to chat about her musical journey, Spotify’s Louder Together program, post-tour plans, and more. Read more below and be sure to catch the rising songstress on her upcoming fall tour with MAX:

10/4, Neumos, Seattle, WA

10/5, Fortune Sound Club, Vancouver, BC

10/6, Hawthorne Theater, Portland, OR

10/9, Holy Diver, Sacramento, CA

10/10, Slim’s, San Francisco, CA

10/11, Voodoo Room @ House of Blues, San Diego, CA

10/12, The Observatory, Santa Ana, CA

10/13, El Rey Theatre, Los Angeles, CA

10/16, The Crescent Ballroom, Phoenix, AZ

10/17, Sunshine Theater, Albuquerque, NM

10/19, The Complex, Salt Lake City, UT

10/20, Bluebird Theater, Denver, CO

10/23, Scoot Inn, Austin, TX

10/24, Bronze Peacock @ House of Blues, Houston, TX

10/25, Cambridge Room @ House of Blues, Dallas, TX

10/26, Voodoo Lounge @ Harrah’s Kansas City, Kansas City, MO

10/27, Delmar Hall, St. Louis, MO

youtube

OTW: Let’s start from the very beginning. Why music? What made you realize music was path you wanted to pursue?

NN: It’s something I have loved doing ever since I was a kid. I was the only child--I had a lot of spare time by myself, and so my parents often times encouraged me to do something that I enjoy and that is creative. I did a lot of art, story writing, and music. Music was my favorite thing out of all the creative arts. Eventually, I put my stories into music and so I started songwriting. It’s something I never thought I could do as a career but I really enjoyed it. Suddenly, one day, I ended up doing it as a career I guess and earning a living from it, and it kind of just stuck.

OTW: How have you grown musically and personally since you’ve released your first EP “Live Take” in 2011?

NN: I’m from a little small village in Scotland, which is very far from the music industry and anything else, so the only opportunity I had was to buy an acoustic guitar and put my music out that way. There were no studios or really any other artists that I could work with. I really liked acoustic music and once I got signed, I moved to London. I feel like the move was key to my sound and style changing and just overall growing as a person. Coming from a small place to one of the biggest cities in the world is a culture shock. You have to grow up. You get to know a lot of different characters as people, and you figure out how things work a bit more. I think that’s what personally matured me. And musically, I had the chance to collaborate with so many amazing people like writers and other artists that have influenced my music. I have a studio set up as well where I produced “The Moment I’m Missing.” I wrote all of the new album there.

OTW: Which of your songs took the longest to write and why?

NN: “The Best You Had.” I had the lyrics, “It’s crazy that you’re moving on so fast but baby it’s okay if I am still the best you had,” in my notebook for a good six months. I was really pleased with that line but kept trying to get it into a song. It means a lot to me. Those lyrics have been in about five different songs that never came out. I kept persevering with it and one day, I was in the studio with my friend Jordan, who I write quite a lot with, and we played these chords, and the song literally wrote itself within twenty minutes. I’m glad I kept trying to better it because I wasn’t happy with it before. It was a nightmare to write but in the end, it was actually one of the easiest songs.

youtube

OTW: What has it been like supporting the Jesse McCartney tour?

NN: Great! So many different audiences from what I’m used to playing to. I wasn’t familiar with his music until before the tour. All my friends absolutely love him, but I never had Nickelodeon as a kid so I never knew about him. He’s great. He knows how to work the stage. He’s so lovely.

OTW: Do you have any traditions you like to do pre-show/on tour?

NN: I try to stay healthy but in America, it’s impossible because you have so much space here. Like sometimes the drive is 10 hours some days and the only thing available is fast food, so I’m just enjoying being unhealthy. My tour ritual for this tour is to enjoy food and eat as much as I can.

OTW: Most memorable moment from your music career so far?

NN: There’s quite a lot of different memorable moments especially because I’ve been doing this for about six to seven years. I would have to say playing to ten thousand people at festivals -- that’s something I’ll never forget. “The Best You Had” got over 30 million streams, which is a really crazy number to me. It was so unexpected. I signed an independent deal with a label, a very casual record deal, just to put out songs that I like, and then suddenly I had over 30 million streams, I’m on a billboard in Times Square with Spotify, and all these things just happened so fast which I’m so grateful for. I feel like a lot of times you only get one shot as an artist and so I feel blessed.

OTW: What’s a city you’d like to someday perform in?

NN: Tokyo. I’m obsessed with Japan and I’ve never been. I’ve been to Hong Kong. I’m really obsessed with Asian culture because it’s so different from British culture. I’ve heard from other artists that go there just have the most amazing time.

OTW: We love your recent release “The Sun Will Come Up, The Seasons Will Change.” What does that song mean to you?

NN: That song was released because it was on a TV show, Life Sentence. That one is part of a collection of songs and represent a journey from start to finish. For example, “The Moments I’m Missing” is the intro track, and it’s about losing yourself and feeling lost. The middle point is “Somebody Special” because you feel like you’ve found your worth again and remember who you are. The last one is “Sun Will Come up, The Seasons Will Change,” and it sums up the whole album for me as a concept and represents the light at the end of the tunnel. I’m hoping people listen to it and take what they want from it. It’s also the message I keep with me in life. Nothing is permanent. Whatever you’re going through whether it’s really shit or really great, don’t take anything for granted. Don’t think your life will be like this forever. If you’re having a bad day, just remember things keep changing all the time.

OTW: What is the first thing you’re going to do once you return home post-tour?

NN: Give my dog a big hug. I’m also shooting a new music video the day I get back.

OTW: Wow! Can you tell us about that?

NN: Yes! I’m really excited for the video I’m shooting because I think it’s going to be something people won’t expect.

OTW: We can’t wait to see it. “Psychopath” was the first ever collaborative single from Spotify’s ‘Louder Together’ program. What was it like being a part of that with Sasha Sloan and Charlotte Lawrence?

NN: It was great! I’ve never actually collaborated with other female artists before and I think like for so long, we’ve been conditioned to think that other females are competition -- don’t work with them, don’t support them. And it’s like come on, we can all have space here to put out music. I think Spotify has done given girls a platform, especially girls in pop. They put you on so many playlists to get your streams up, which means more people come to the gigs, and it really helps. This collaboration was really cool because I’m a big fan of both of them and Sasha is an amazing song writer and Charlotte is an amazing new artist. It’s cool to get in a room with like-minded females that also do pop and understand what we do on a daily basis.

OTW: Who are some of your Ones to Watch artists?

NN: So later this summer, I will be touring with Lewis Capaldi, who I think is amazing. He’s Scottish. He’s great. I think he’s going to do really well and everyone should check him out.

1 note

·

View note

Text

5 Things to Know About Gabriela Hearst, the Designer Behind Meghan Markle’s ‘Nina’ Bag

Gabriela Hearst is one of those fashion designers whose name is frequently used in conjunction with words like ‘cult’ and ‘insider.’ Which is to say she might not be a household name like, oh, Marc Jacobs or Stella McCartney, but has quietly cemented her place within the fashion community, amassing a loyal clientele sans fanfare. Her approach to slow fashion, with an emphasis on high-quality, luxurious fabrics, has found favour with—yes—fashion insiders, and earned her—yes—a cult following. For a label that launched just three years ago, she has made some very large strides in a very short time. Read on for a few things to know about the New York-based designer whose handbag Meghan Markle just carried on a royal engagement in Sussex, most certainly shattering whatever under-the-radar status she had before.

Photography via Beretta/Sims/REX/Shutterstock

1. She grew up on a ranch in Uruguay, which she now runs

New York has been Hearst’s home for over a decade (she lives in the West Village with her husband, publishing scion Austin Hearst, and their children) but she goes back several times a year to the ranch in Uruguay where she grew up, and which her father bequeathed to her upon his death in 2011. “It really formed a very specific aesthetic and point of view,” Hearst tells MatchesFashion.com. “Growing up in a remote landscape with objects and structures that were made to last, quality was a needed characteristic while opulence was not. Things needed to last from a utilitarian perspective and nothing got thrown out – things were re-purposed. The objects and my surroundings had character, formed by the lives that were lived and the passing of time.”

View this post on Instagram

The Source #gabrielahearst

A post shared by Gabriela Hearst (@gabrielahearst) on Apr 24, 2018 at 10:03am PDT

2. Sustainability lies at the heart of her brand

Given her upbringing and connection to nature, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that sustainability forms the crux of her eponymous label. 99% of her textiles are sustainable, reports Financial Times, and her commitment to zero waste, upcycling and eco-conscious processes is well-documented. She only uses certified natural fibres and viscose for her designs; utilizes leftover materials like cashmere and silk from previous collections for her accessories; and uses compostable packaging for the brand’s shipments. The company also aims to be plastic-free by 2019. “The two things I ask about every decision are: ‘is this sustainable and environmentally friendly?’ and ‘is this good for the long-term view?’ Because this is an endurance race,” she tells the FT.

3. She’s also a philanthropist

Hearst has worked with several non-profit organizations over the years to raise both money and awareness for their causes. In 2016, she collaborated with Tod’s on a limited edition sneaker; 20% of the proceeds from its sales went to Save the Children (where she now serves on the Board of Trustees). Last year, she produced a limited run of ovary-embroidered sweaters, the profits of which went towards Planned Parenthood. She also partnered with Net-a-Porter and Bergdorf Goodman, making her handbag collection available for online purchase for one week only, in order to raise awareness about the terrible drought in Kenya.

View this post on Instagram

A year ago exactly to date, I had the honor to accompany Carolyn Miles CEO of @savethechildren to Turkana, Kenya and experience first hand the damage that the severe drought (climate change) had and still has on millons of people at risk of famine. I was so fired up by what I saw as well as witnessing the determination of the Turkana mothers to have their children survive, that it propelled my team and I on a mission. To raise 600K that would be able to cover basic feeding for 1000 families. While it was a drop in the bucket of what it is needed, it was a great challange for us to achieve. What an amazing gift it is to be able to help other people and further ignite the ambition to do more. Thank you #SaveTheChildren for all you do for the mothers and children of the world.

A post shared by Gabriela Hearst (@gabrielahearst) on Jul 19, 2018 at 8:32am PDT

4. Her first handbag, the Nina, has spawned crazy waiting lists

Only 20 pieces were initially produced of the Nina bag, which Hearst launched back in October 2015 in just two colours—black and cognac. “I did a limited edition of 20 bags; I didn’t do it for commerce, I just wanted to launch it,” she tells Vogue. “And I gave them to friends of mine and to women I work with. The woman who makes my shoes has it. And Brie Larson, the actress, has it.” The bag quickly gained cult status, racking up a waiting list in just a few short months. The bag now comes in two sizes and a slew of different colours and materials, from denim to silk to crocodile leather, but can be ordered only on her website, where customers need to sign up via their email address to get on the waiting list. If you want to get your hands on it ASAP, you’re in luck because her line of handbags—including the brand new lunchbox-style Patsy—is popping up for two weeks only on Net-a-Porter, from October 1 to 15. “They represent an amazing window,” Hearst tells the FT. “They have the bag for just two weeks, and it’s going to give it tremendous exposure. Because of the amount of copies happening, it’s good to open the door a little and then close it, so that people can access the products in the right way, and understand what they are.”

View this post on Instagram

“The research process is one of my favorite parts. My motto is to understand our history to know where we came from and where we are going. For the Patsy, I was inspired by the lunchboxes of women entering the work force during the 1940s.” Gabriela Hearst Authentic Handbags with Block Chain technology Available for two weeks only @netaporter (Patsy Crocodile coming soon…)

A post shared by Gabriela Hearst (@gabrielahearst) on Oct 1, 2018 at 9:00am PDT

5. Meghan Markle’s not her only A-list fan

Hearst created a custom-made dress for Laura Dern for the 2017 Met Gala, and has also found fans in celebs like Anne Hathaway, Selena Gomez, Emma Stone and Gugu Mbatha-Raw. Upon awarding Hearst the 2017/18 International Woolmark Prize, Victoria Beckham, one of the judges involved in the selection process, said, “I was very much in support of Gabriela. For me, she is a worthy winner. I love what she does and she’s clearly very talented. I like her eye, she has great products and she’s a strong woman. I have a huge amount of respect for her.”

0 notes

Text

Transcript of How to Develop the Right Idea at the Right Time

Transcript of How to Develop the Right Idea at the Right Time written by John Jantsch read more at Duct Tape Marketing

Back to Podcast

Transcript

John Jantsch: Hello and welcome to another episode of the Duct Tape Marketing podcast. This is John Jantsch, and my guest today is Allen Gannett. He is the CEO and founder of TrackMaven, a marketing insights platform. He’s also the author of a book we’re going to talk about today called The Creative Curve: How to Develop the Right Idea at the Right Time. Allen, thanks for joining me.

Allen Gannett: Thanks for having me, man.

John Jantsch: A big premise of the book is to kind of debunk the creativity myth that you sit around and get this inspiration from a muse at some point in your life and that, in fact, there’s a science behind it. You want to tell me kind of your … it’s really the big idea of the book, I suppose, so you want to unpack that for us?

Allen Gannett: Creativity is one of those things that we talk about a lot in our culture. It’s on the cover of all these magazines. It’s this big topic in boardrooms. In Western culture, we have this notion of creativity as this magical, mystical thing that strikes a few certain people each generation, and there’s the Elon Musk and Steve Jobs of the world and the Mozarts and the JK Rowlings, but for the rest of us normies, we’re just sort of left out in the cold.

Allen Gannett: The thing that always bothered me is I’d always been someone who’d been a big reader of autobiographies and some of the literature around creativity. I run a marketing analytics company, so I spend a lot of time with marketers, and I didn’t realize the extent to which this had internalized with people. I thought people sort of knew that was the story but knew that, of course, that’s not actually how it works. I realized that, no, no, this is really how people believe creativity works, and so the book sort of came out of this frustration I had that I saw all these very smart people limiting their potential.

Allen Gannett: The book is split into two halves. The first half of the book I interviewed all of the living academics who study creativity, and I break down the myths around how creativity works using science and some of the real histories. I tell some of the real stories behind things like Paul McCartney’s creation of the song Yesterday, which has been over-hyped and over-sold for decades, and Mozart, which there was a whole bunch of, literally, things like forged letters and forged articles about Mozart that have become part of our common myths around Mozart.

Allen Gannett: In the second half of the book, I interviewed about 25 living creative geniuses. These are everyone from billionaires like David Rubenstein, Ted Sarandos, the chief content officer at Netflix, Nina Jacobson, the former president of Walt Disney Motion Pictures. She’s the producer of The Hunger Games. I interviewed even folks like Casey Neistat from YouTube and … really eclectic set of creative geniuses with the goal of saying, okay, if the science shows us that you can actually learn to become more creative, well then how have people actually done that? How have they accomplished that? The book is meant to both be a sort of myth-busting book but also actually be a practical guide to actually leveraging this yourself.

John Jantsch: I think there’s actually a lot of misunderstanding or misuse of the word creativity anyway.

Allen Gannett: Oh, totally.

John Jantsch: I do think that a lot of people that I run into, “Oh, I’m not creative,” which means, “I can’t paint like Picasso,” or something when, in fact, in my business, I’m not … If you set me down and say, “Make something,” I’m not a maker, but I could … I’ve built my entire career around taking other ideas and seeing how they fit together better, and I think that’s a creative science.

Allen Gannett: Oh, and totally, and this is one of the things that people … We have sort of a book cover mentality of creativity, I like to call it, where I wrote a book, there’s one name on the cover, but there’s so many people involved who are creative who make that happen. I mean there’s agents, editors, marketers, copy editors, proofreaders, research assistants, feedback readers, right? Every creative endeavor you see actually has a lot of different people involved, but we sort of have this book cover phenomenon, or I sometimes call it the front man phenomenon. In a band, we talk about the lead singer all the time even though there’s five people in the band. With creativity, we sort of talk about Steve Jobs and Elon Musk as if they’re these sort of Tony Stark-esque characters, and we forget the fact that Steve Jobs had Steve Wozniak. Elon Musk literally has the world’s best rocket scientists working for him.

Allen Gannett: The idea that these people are rolling these boulders up a hill by themselves is just not true, and so I think we’re surprisingly susceptible to these sort of PR person propagated narratives around creativity, because I also think, John, we kind of like it. We kind of like the idea that there’s something out there for all of us that’s going to be easy. When we talk about our passion, I think we’re slightly actually talking about, well, waiting for something to be easy, but nothing in life is easy.

Allen Gannett: You look at Mozart, and we talk about him as if he popped out of the womb playing the piano, but the reality is, when he was three years old, his dad, who’s basically a helicopter dad, was like, “You need to become a great musician.” Under the conditional love of his father, he started taking lessons with literally the best music teachers in all of Europe, and he practiced three hours seven days a week his entire childhood. This is not the story of it being easy for Mozart. This is the story of him doing the really hard part when he was young. I think we like this idea that, for some people, it’s easier, for some things it easy, because it kind of gives us an excuse.

John Jantsch: Well, and I also think that the narrative that is simple is a really useful device too because people can then share it, and they don’t have to … What you just went through, nobody wants to tell that story.

Allen Gannett: Of course, 100%. Everyone wants to believe it’s just straightforward.

John Jantsch: Yeah. I think you go as far as saying that just about anybody with the right motivation and the right process could practice and develop a skill, so let’s … Since I mentioned Picasso, could I paint if I had the right motivation?

Allen Gannett: Yes.

John Jantsch: I mean, right now, I will tell you I can’t.

Allen Gannett: Yes.

John Jantsch: I don’t think I could paint anything that anybody would see commercially interesting, but-

Allen Gannett: Totally.

John Jantsch: Right.

Allen Gannett: There’s two different parts of creativity. There’s the technical skill, and then there’s creating the right idea at the right time. On the technical skill side, we actually have now decades of research on talent development. What’s amazing, this is something I didn’t … I didn’t expect it to be this much of a consensus when I started writing the book, but the people, the researchers who spend their time studying talent development have come to the conclusion that, at best, natural-born talent is very rare and [wholefully 00:06:47] overblown, but more likely than not, the idea of natural-born talent actually doesn’t really exist.

Allen Gannett: It’s really that these people typically start very young. They have access to a lot of resources or maybe they were working on another skill, like the daughter who always played baseball in the backyard with her dad and then, by the time she was 12 and she went to her first-ever track practice, she was such a fast runner, and they’re like how did she learn this? It’s like, well, she was playing baseball in the backyard for seven years.

Allen Gannett: In the book, I actually profile the story … It’s actually one of the few stories we have of someone tracking their skill development over a long period of time. It’s the story of Jonathan Hardesty, who’s this painter who, at the age of 22, having never painted before, decided that he wanted to become a professional painter, and he proceeded to … For whatever reason, he was active on a online forum, and he created this forum thread which said that, “Every day, I’m going to post a picture of my painting. I’m going to paint every single day,” and for the next 13 years he did this, 13 years.

Allen Gannett: It’s a really amazing story being able to see he was such a terrible painter when he started. I got permission from him to use one of his first-ever sketches in the book and one of his sketches from much later, and it’s shocking. What he did is he followed, actually, all of the best practices that we have from research on talent and skill development on becoming a great painter, and now he teaches all these courses and classes on becoming a fine art painter and all this stuff, and his paintings sell for five figures, and so he’s a really great rare example of someone starting when they’re old. I think it’s hard because, when you’re older, you’re busy. You don’t have that much time, and there’s not a father or mother figure sort of bearing down on you, forcing you to get through the hard part.

John Jantsch: Well, and I do want to get to your four laws of the creative curve because I think that’s … obviously, that’s a big part of the book, but I think it’s also … I think people need to hear that process, but I want to start with something before that. One of the things that I have observed in my own life and in watching a lot of other people is that motivation has a tremendous amount to do with this.

John Jantsch: I’ll give you an example. I taught myself how to play the guitar when I was in junior high, and it wasn’t because I ever envisioned becoming a famous rock star. I saw it as a great … It turns out junior high girls love guitar players. That was a huge motivation for me to just take this thing on and do it myself. As silly as that example is, I think that that is probably the key to unlocking the whole thing. Isn’t it?

Allen Gannett: I mean this is one of the things that people sort of don’t realize. I think the reason why we see so many young people who seem to be very creative, it’s because their parents forced them. Right?

John Jantsch: Right, right.

Allen Gannett: That’s powerful [inaudible 00:09:37]. It’s Freudian. It’s developmental, whatever sort of psychological perspective you want to put on it, but over and over again we see that the idea of a stage parent is actually … plays a huge role in a lot of these young, creative lives. It’s a lot easier to be world-class by the time you’re 30 if you started when you were 3 than if you started when you were 25.

John Jantsch: Right, right, right. Yeah, I had to beg my parents to buy a used guitar, by the way. All right, so let’s talk about, then, the four laws because I do think that a lot of … there are definitely a lot of people, this is kind of ironic, a lot of people that are more left brain, and they need a process to be creative. I mean it makes total sense. You should pick up the bird, the book, I’m sorry, The Creative Curve.

Allen Gannett: And the bird.

John Jantsch: And the bird, to get really in-depth in this, but I’d like Allen to introduce his four laws.

Allen Gannett: Yeah. Basically, when we talk about creativity, there’s two types of creativity. There’s lower-case C creativity, and there’s upper-case C creativity. This is how academics differentiate them. Lower-case C creativity is just like creating something new. Upper-case C creativity is what most of us actually want to do, which is creating something that’s both new and valuable. Value is a subjective assessment, right? Creating something that we deem society to be valuable, well, people have to see it. They have to experience it. They have to deem it valuable, so there’s a bit of a circular phenomenon that happens.

Allen Gannett: The back half of the book deals with this sort of upper-case C creativity. How do you actually get this? How do you actually develop the right idea at the tight time? It turns out that we actually have a lot of really good science about what drives human preference. I explained it a lot more in detail in the book, but the short version is that we like ideas that are a blend of the familiar and the novel. They’re not too unfamiliar to be scary, because we’re biologically worried to fear the unfamiliar because we worry it might kill us, like if we went to a cave as a caveman that we’d never been in before versus a cave we’ve been in many times, but then we also … turns out we like things that are novel because they represent potential sources of reward. You can think about when we were hunter-gatherers why this was important.