#eugeneodontida

Photo

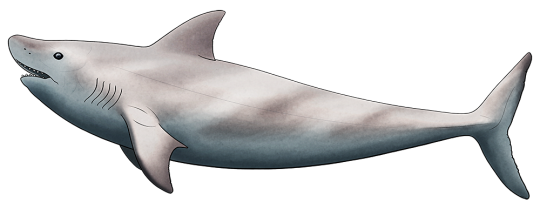

The eugeneodonts were a group of cartilaginous fish that convergently resembled sharks but were actually much closer related to modern chimaeras. They had unique "tooth whorls" in their jaws, and the most famous member of the group is probably Helicoprion, whose bizarre buzzsaw-like tooth arrangement was only properly understood within the last decade.

Ornithoprion hertwigi here was one of the first eugeneodonts found with fossilized skull material, and helped with the early understanding of just how their weird jaw anatomy actually worked.

It lived during the Late Carboniferous, about 315-307 million years ago, in a shallow tropical sea that covered what is now southwestern Indiana, USA.

At only around 50cm long (~1'8") it was one of the smaller eugeneodonts, and along with a small Helicoprion-like tooth whorl it also had a distinctive highly elongated chin. Similar to modern halfbeak fish this structure may have served a sensory function, helping Ornithoprion to detect prey in dark or murky waters.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#ornithoprion#caseodontidae#eugeneodontida#holocephali#chondrichthyes#cartilaginous fish#fish#art

376 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Helicoprion's Pelvic Fins (or lack thereof)

For about a year, now, I've been wracking my mind on the subject of the latest reconstruction of the extinct holocephalan[1] Helicoprion[2]. By all other accounts the latest reconstruction, which can be viewed below, is the best it's ever been. The iconic Eugeneodontid[3] tooth whorl fits into the jaw in a logical way and lends credence to our present understanding of its diet.

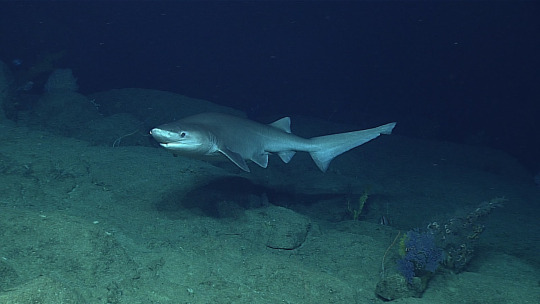

But, as you gaze further posterior, you may notice something queer: no pelvic or anal fins. Now, a not-insignificant number of living chondrichthyes[4] lack anal fins. This is not out of the realm of imagination. But the same cannot be said of the pelvic fins, which aid in control and stabilization and also serve as the girdle for which claspers are attached to in males. All living chondrichthyes possess pelvic fins; from chimaeras like Hydrolagus colliei[5], to sharks like Hexanchus griseus[6], to skates[7] like Raja binoculata[8].

(Hydrolagus colliei)

(Hexanchus griseus)

(Raja binoculata)

So, why are they missing in our latest reconstruction? I made attempts last year to reach out to the researcher responsible for our modern understanding of Helicoprion, Jesse Pruitt (whose lecture on his research set me off on this journey), through LinkedIn, but I never got a response. Looking through my message history, though, the conversation appears to have disappeared, making me wonder if I'd actually sent it at all.

This morning, I tried again. I drafted up my question and reasoning and sent it to Pruitt's LinkedIn and ResearchGate profiles, and I sent it to the Idaho Visualization Laboratory (IVL) which made the Helicoprion model. I had expected considerable delay, but to my mirth, I got a response this afternoon.

On behalf of IVL, Leif Tapanila responded to my email with answers. As it were, other Eugeneodontids from the Carboniferous and Permian periods were preserved better than our Helicoprion specimens. Specimens of Fadenia[9] and Romerodus[10] were preserved very well with full-body imprints in consistent shale rock.

(Fadenia)

(Romerodus)

These imprints lack pelvic fins. Considering their close relation to Helicoprion, this absence was assumed for the visualization. I've inquired after Edestus[11], another Eugeneodontid of the same era, since there are many specimens and imprints, however fragmentary. I have yet to receive an answer, but when I do, I will update this post.

(Edestus)

I was determined to find some oversight, since holocephalan specimens from the Devonian period include pelvic fins in their reconstruction, but it seems the facts have dissolved my suspicions. I wanted to share this with you all, since I cannot edit Wikipedia articles (much to my dismay, as I have learned much and more in my studies of H. griseus that I want to add to its page). This knowledge deserves to be shared, since I find it ponderous.

Until next time,

[1] Subclass of chondrichthyes, containing contemporary chimaeras.

[2] Extinct eugeneodontid. Etymology translates to "Spiral saw"

[3] Order of holocephalan characterized by tooth "whorls" and inability to shed teeth.

[4] Class of chordate (vertebrate) characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton

[5] Chimaera known as the "spotted ratfish"

[6] Hexanchiform known as "bluntnose sixgill shark"

[7] Order of elasmobranch "Rajiformes," adjacent to rays.

[8] Rajiform known as "big skate" (no, really. haha)

[9] Eugeneodontid from the Carboniferous, Permian, and Triassic period

[10] Eugeneodontid from the Carboniferous period

[11] Eugeneodontid from the Carboniferous period characterized by its scissor-like teeth and jaws.

#helicoprion#edestus#romerodus#fadenia#holocephalan#chimaera#chimera#chondrichthyes#eugeneodontida#jesse pruitt#idaho state university#idaho visualization laborator#ivs#paleontology#marine biology#fish

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ornithoprion

Ornithoprion — це вимерлий рід суцільноголових євгенеодонтів, близький до Caseodus. Він жив під час пізнього карбону, приблизно 315-307 мільйонів років тому, у мілководному тропічному морі, яке охоплювало територію сучасної південно-західної Індіани, США. Типовий вид — Ornithoprion hertwigi. У різних видів була подовжена нижня щелепа. Відкриття та опис Ornithoprion допомогли встановити багато аспектів анатомії черепа євгенеодонтів,…

Повний текст на сайті "Вимерлий світ":

https://extinctworld.in.ua/ornithoprion/

#ornithoprion#indiana#usa#north america#eugeneodontida#sea#art#fish#paleoart#late carboniferous#ornithoprion hertwigi#carboniferous#риби#carboniferous period#paleontology#prehistoric#illustration#fossils#сша#палеонтологія#палеоарт#ukraine#ukrainian#мова#daily#prehistory#extinct#українська мова#арт#україна

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Animal Crossing Fish - Explained #53

Brought to you by a marine biologist who thinks ancient fish are rad...

Click Here for the AC Fish Explained Masterpost!

Hmmmm...really dating myself by saying “rad”, huh? Sometimes I feel pretty old and using ‘80′s/90′s lingo doesn’t help. But I think bringing you all into the world of antiquated words and thoughts is a good idea when talking about today’s fossil and the animal it came from - the Tooth Whorl of Helicoprion.

Yeah, after (how many?!) fish explained posts, we’re finally covering another fossil fish. I believe, by now, if you’re like me and been playing since launch, you’ve discovered every single fossil ACNH has to offer and now you’re either selling them, giving them to friends who foolishly started late, or you’re putting them all over your island and house like you see me doing above. Whatever way, you probably got this already.

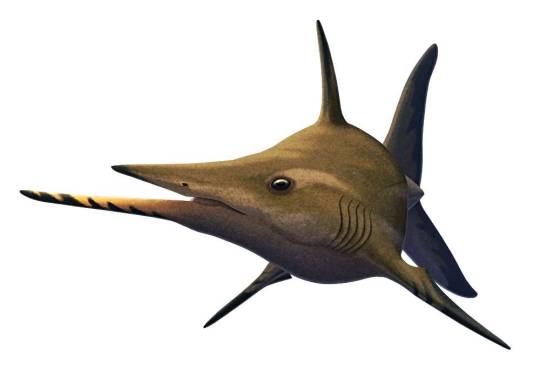

The Shark Tooth Whorl...I don’t expect anyone to know what it is or what it represents unless they’re a big prehistory or fish buff or are standing at the magical junction of both those things like I do. But the thing I want you to get out of this is that, even though it’s called “Shark” tooth-whorl, it didn’t belong to a shark, but a distant cousin. The animals are called “Helicoprion” (it’s a genus with 3 species; I pronounce it hell-uh-coh-PRY-on...if that’s not right, PLEASE TELL ME), and they are estimated to have been quite large, some estimates putting them at 33 ft (10m). Here’s what the fossils look like in real life:

Discovered in the late 1800′s, no one knew what to make of this. Nothing like it exists today, and it took about +100 years, until 2013, for scientists to finally piece together where the tooth whorl fit on the animal. I mean, really, take 5 minutes to look up the tooth whorl and Helicoprion and see all of the hilarious proposals of where they thought this might fit, including at the tip of the snout, the tail, and ya know, everywhere including the mouth.

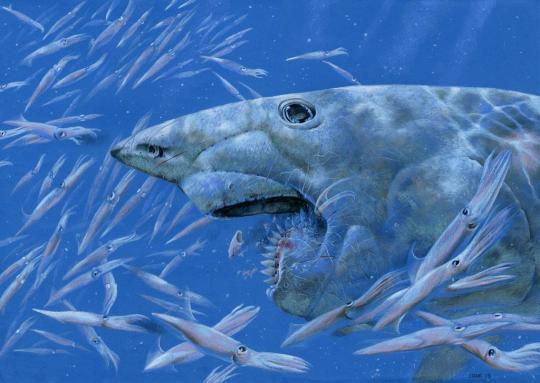

But science did learn in 2013, in this study, how the tooth whorl fit into the fish’s jaw, with bigger teeth replacing the smaller ones as the animal grew, pushing the small teeth forward around into the jaw, making this whorl. Using CT scans and 3D modeling techniques, we now know Helicoprion spp. looked kinda like this:

Top picture from one of my favorite science illustrators -> his DeviantART SharkeyTrike; the bottom picture from renowned scientific illustrator, Ray Troll.

Now, like I said above, Helicoprion wasn’t a shark, although, for a long time, scientists assumed it was. We now know Helicoprion was actually more closely related to the fish of Holocephali, the chimeras, also known as ratfishes. Of course, this relation is still distant - Helicoprions were so derived and unique, that they belong in their own, now completely extinct, Order Eugeneodontida. Just like the sharks, fish of Holocephali have cartilaginous skeletons, meaning their skeletons are made of cartilage, as is the running theme of cartilaginous fish, like sharks, rays, and the chimeras. Millions of years ago, they were incredibly diverse. Unfortunately, cartilage absolutely sucks when you’re trying to leave behind a fossil, so lots of ancient sharks and relatives are only known from their teeth, as was the case for Helicoprion. Now we know what Heli’s face looked like, but because the fossils are so poor, the rest of the body is a mystery, even though we can make our best guesses based on how we think it fed and what it fed on and where it lived. Given how weird living ratfish are, though, who knows what Helicoprion really looked like.

Here’s a living relative ratfish because I bet you’ve never seen one before:

Helicoprion lived in the world’s oceans before the dinosaurs during the Permian Period, some 290 million years ago.

And there you have it. Fascinating stuff, no?

#helicoprion#shark#chimera#marine biology#animal crossing#fossil#animal crossing new horizons#science in video games#animal crossing fish explained

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

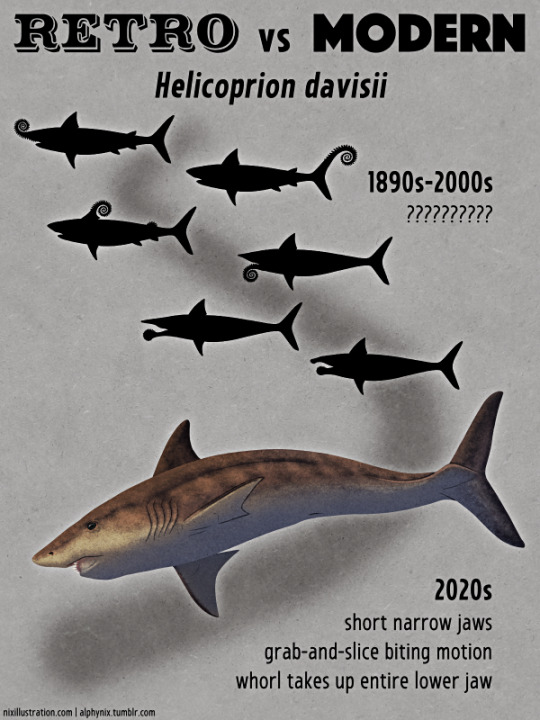

Retro vs Modern #08: Helicoprion davisii

First discovered in Western Australia in the mid-1880s, the bizarre-toothed eugeneodont cartilaginous fish Helicoprion davisii was initially mistaken for a species of the equally weird Edestus. It was eventually recognized as part of a separate genus over a decade later, when similar fossils of its close relative Helicoprion bessonowi were found in the Ural Mountains.

1890s-2000s

With Helicoprion only known from strange buzzsaw-like spiral whorls, the function and location of this structure in the fish's body was a huge source of confusion for over a century.

The earliest interpretation was a defensive structure curling upwards from the snout, then as part of the tail or dorsal fins. It was soon realized to probably be part of the lower jaw instead, but the exact arrangement was still a mystery.

A downward-curling position was popular in reconstructions for much of the 20th century. From the 1960s onwards, however, discoveries of preserved skull cartilage and soft-tissue body outlines of other eugeneodont species began to give a better idea of what these fish were and what they looked like. They were identified as being related to modern chimaeras, but with a very different appearance – they had streamlined shark-like bodies with large triangular pectoral fins, a single dorsal fin, no pelvic or anal fins at all, and broad keels along the sides of their tails.

A single tooth whorl sat in the middle of the lower jaw, with its sides covered by skin, and the largest and youngest teeth formed at the back before spiralling forwards, downwards, and inwards.

In the 1990s a "pizza-cutter" reconstruction gave Helicoprion long narrow jaws with the whorl positioned very far forwards, sawing and crushing prey against the underside of the snout. A version with the whorl very deep inside the throat was also proposed in 2008, but only a year later a new variant of the pizza-cutter saw-jaw model suggested the presence of a specialized "pocket" in the upper jaw lined with teeth.

2020s

Finally, in 2013, CT scanning of a Helicoprion specimen originally discovered in the 1960s revealed something incredibly special – an almost complete three-dimensionally preserved and articulated set of jaws. It showed narrow jaws that were shorter than the previous reconstructions, with the whorl occupying the entire lower jaw and braced by cartilage on each side.

We now know Helicoprion davisii was found worldwide during the early-to-mid Permian, about 272-268 million years ago, and based on some of the biggest known tooth whorls it may have reached sizes of up to 8m long (~26'), similar in size to modern basking sharks. It continuously added new and larger teeth to its whorl throughout its life, with the smaller older teeth being retained instead of shed, slowly pushed into a tight spiral deep inside the lower jaw.

The upper jaw formed a sheath-like pocket lined with a "pavement" of numerous tiny rounded teeth, and as Helicoprion closed its jaws the various parts of the whorl simultaneously grabbed, sliced, and pulled prey further into its mouth – a mechanism possibly specialized for efficiently de-shelling cephalopods like ammonites and nautiloids.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#retro vs modern 2022#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#helicoprion#helicoprionidae#eugeneodontida#holocephali#chondrichthyes#cartilaginous fish#fish#art

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Weird Heads Month #11: Scissor-Toothed "Sharks"

The eugeneodontidans were a group of cartilaginous fish which convergently evolved to resemble sharks but were much closer related to modern chimaeras. Due to their cartilage skeletons usually little more than their teeth are found as fossils, and for a long time their ecology and life appearance has been poorly understood because of just how weird those teeth were.

These fish had unique "tooth whorls" in their lower jaws, and the most famous member of the group is probably Helicoprion, with the exact anatomical placement of its buzzsaw-whorl only being properly figured out in 2013.

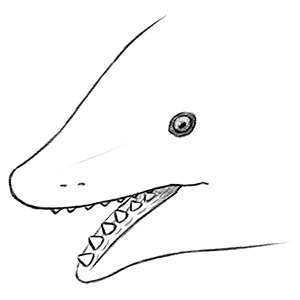

But another eugeneodontidan named Edestus was equally strange.

Living during the late Carboniferous, about 306-299 million years ago, Edestus giganteus was the largest species in the genus, reaching estimated lengths of up to 6m (19'8"), similar in size to a modern orca or a particularly large white shark.

Let's take a closer peek at that mouth.

Yes, that's a single central row of teeth in both its upper and lower jaws.

Edestus' whorls grew in curving "banana-shaped" brackets that resembled an enormous pair of pinking shears, with new teeth being added on at the back and the oldest teeth occasionally being ejected off from the front. How this jaw arrangement worked was a longstanding paleontological mystery, with various bizarre ideas being proposed over the years – until a particularly well-preserved skull was analyzed in early 2019, revealing a two-jointed system in its lower jaw that allowed it to move its tooth brackets quickly back and forth, using a "snap-and-slice" motion to grab hold of prey like fish and soft-bodied cephalopods and cut them in half.

Along with body impressions from other related eugeneodontidans like Fadenia, showing a shark-like tail and a complete lack of rear fins, we now have a much better picture of what this bizarre fish probably looked like.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Pillowfort | Twitter | Patreon

#weird heads 2020#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#edestus#edestidae#eugeneodontida#holocephali#chondrichthyes#cartilaginous fish#fish#art#probably much more accurate than my last attempt at edestus#it's just a slightly weird shark rather than an ugly chimaera now#go home evolution you're drunk

463 notes

·

View notes

Note

This probably won't have a clear answer but how did eugeneodontidans get about reproducing? They don't seem to have any claspers or similar structures (or anything past the pectoral fins really).

We don’t know!

They might have evolved some form of internal fertilization, but since body fossils of eugeneodontians are so rare it’s also possible we’ve just only ever found females.

There’s a similar problem with the Devonian shark Cladoselache.

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Edestus, a holocephalan fish from the Late Carboniferous (~315-299 mya) of Eurasia and North America. A relative of the “spiral-saw-mouthed” Helicoprion, it continuously grew a single row of teeth in each jaw, creating an arrangement often compared to a pair of pinking shears.

Multiple species of this genus have been named, with varying degrees of tooth bracket curvature, and the largest may have had body sizes similar to modern white sharks -- about 6m long (19′8″).

Since Edestus is only known from fossilized tooth brackets, how exactly its jaws worked and what it ate with them is still a mystery. Many reconstructions end up either goofy or horrifying as a result, and so I’ve attempted to make this one look a bit more “normal”. And capable of closing its own mouth.

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#edestus#scissor-tooth shark#edestidae#eugeneodontida#holocephali#chondrichthyes#fish#art#go home evolution you're drunk#seriously what's with all the HORRIFYING PROTRUDING SKINLESS JAWS?

176 notes

·

View notes