#i hope albert heals some of his trauma with her love too

Text

Shout-out to Mrs.Anne Lee the only parent who actually parented her sons (Kevin and Chim) without causing them trauma and loves them unconditionally.

#she's the best parent in the show#anne lee#chimney han#howard han#kevin lee#i hope albert heals some of his trauma with her love too#at least jee yun has one lovely grandma!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

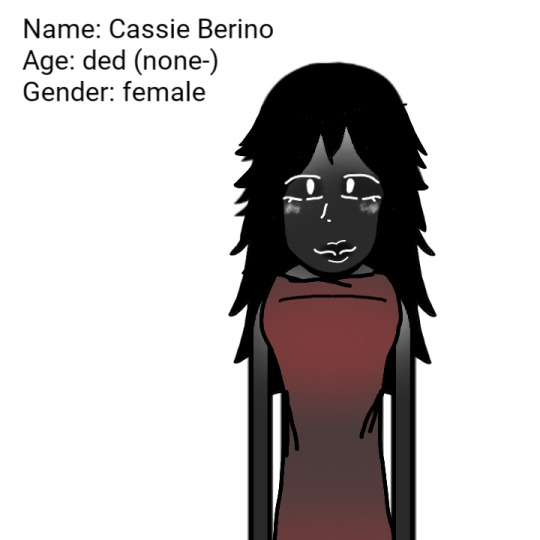

Guess I'm bored and wanted to make some little lores

So I make that old incer mental hospital owner an oc

I tried to make her look like the one I drew-

I were have no idea how she can look like so I just drew this shet, but now her re design is was gorgeous and even have a lore lol

Cassie Berino were an grown lady who owns the incer mental hospital, she were always loved to be an hospital owner due to her trauma about losing her father cause of his mental breakdown (he su!c!de after cause of it), she always wanted to help the once who's mental broken and heal them, that's why she study doctor, she were a sunshine person, always try her best to make everyone happy, and Dr Albert were her last victim of it, ever since they met, Cassie always try to make him laugh, no matter what he says she never leave him, and soon they become closer and one day Cassie didn't showed up, Cassie were having horrible lung pain and barely able to breathe, her mother take her to a hospital and she found out she has lung cancer, that broke her badly, when her friends find out, they start to get away from her, everyone expect Albert, Albert were also find Cassie's actions annoying but also felt bad that a sunshine like her got cancer, he and her start to hangout more and Albert try his best to help Cassie about her healthcare and beat her cancer, months pass and they both open their hospitals, they celebrate it with a picnic, it was nice, they were took out a radio and dance together, then Cassie thinks, and she got an doubt, she told Albert that what if she didn't survive till too long because that was killing her, Albert told her to not say those words and told her that everything will be fine and she will beat her cancer, then Cassie asks Albert "if something happens..can you take care of my hospital for me? And if something happens to you..ill take care of yours" that make Albert chuckle, he were fully believed that Cassie will beat the cancer but he kept the promise, after some days, it was the 2th anniversary of Cassie's hospital open so Albert wanted to surprise her with a rose, he when to her house and her mother greets him, she were not so healthy but seem alright, Albert realize that Cassie didn't woke up yet so he decided to surprise her in the bed, he go to her room and see her laying on her bed, he lean closer and whisper to her to wake up, Cassie didn't answer, so he thought "hm..you really like to make me embarrass myself, aren't you?" Get lean close and kiss her in the check, maybe she'll shock and woke up, but she didn't move at all, Albert start to get worried and shake her gently, calling her name, bit when his hand get to her chest, he didn't felt a heartbeat at all..Cassie were not breathing, Albert panic and carry her to the hospital, some hours later the doctors told him that she were died during her sleep, that hit Albert badly, he promised her that she will beat the cancer, but lung cancer had other ideas, after that day, Cassie Berino passed away, and like Albert promised, he took care of her hospital, no one know what happened to the body, Albert didn't tell anything about that, to be honest that so..weird, But he probably had some ideas for her, since he's like a scientist, you know what that mfs do.

I also draw them, look!

👉👀👈

Their last dance ✨

I want what they had-

Lmao

Damn, that series gave me insane lore ideas, I'm glad I created that series

Dr Albert Morgan belongs to @weirdsillycreature btw-

Hope you like the lore and the arts brah :3💖💖💖💖

#incredibox#orin ayo#breakthrough#tragibox#incredibox breakthrough#incredibox e.v.a.c.u.a.t.e#incredibox orin ayo#incredibox fanart#incredibox oc#wekiddy

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

healing in 5b

this season was all about healing, and we got so many lovely arcs out of it, and especially in the finale.

the big arcs obviously, Maddie's and Eddie's: those two literally went through hell in 5a and 5b both, and they fought to heal themselves, to feel better, for their family. the finale did such an amazing job of bringing together 18 episodes of setup as it finally brought both Maddie and Eddie back to where they belong: with their families and at the dispatch/118

Eddie and Bobby/Ramon was such a fun journey to see. We went from Eddie completely blowing up at Bobby (who was trying to support him in the best way that he could) to Bobby being there for Eddie in the wake of his breakdown to Eddie using the things he learned from Bobby (and his therapist) to try and fix his relationship with his actual father. And then the scene in the finale? Well, if you can't say full circle relationship there, where can you say it? Therapy!Eddie is healthy, wealthy, and thriving, and he's doing his best to share that emotional strength as he accidentally saves Bobby from himself.

Madney as a whole have been through so much this season, but even individually, Maddie and Chim went through huge trauma and doubt. Maddie about her capability as a mother, Chim about his capabilities as a partner, and I think the choice to let them both heal and grow on their own before (HOPEFULLY) bringing them back together only makes their relationship all the stronger.

I've always felt that BuckTaylor was an unhealthy relationship. Not the couple itself, they definitely had some chemistry, and both of them were genuinely trying to make things work, but the way that they got together in the first place. Buck was so shaken(literally) in the aftermath of the shooting, and he latched onto the first person who offered him their hand. The way they broke up, well, we could have seen it coming from a mile out. Buck and Taylor unfortunately will always be on opposite sides when it comes to this kind of argument, simply because of who they are as people. They might have tried to overlook each other's faults, but neither of them could hold on. Buck and Taylor both knew that it was time to separate, and doing so was good for both of them, they way she finally left, it wasn't bitter, it wasn't a typical break-up scene, it was a mutual understanding between two people who (I hope) will be friends in the long run.

Henren had a lot of new starts and revelations too, especially in the back half of s5. We got some beautiful scenes of Hen and Karen finding themselves again, becoming at peace with who they are, with no regrets. Plus the conversation in the finale was one that was so sweet, my heart especially felt for Karen not being mad at Toni for her sake, but for Hen's. Karen has been through a lot with the drama with Hen and Eva, and I think they've finally settled into their relationship and family together, at peace.

Honorable mention to Albert, who opened himself up to Chimney, even thinking that Chimney might reject him for how he was feeling about firefighting. Chim not only assuaged his fears abut also encouraged him to do what he really wants to, a marked difference for Albert from what he ran from their Father for.

over all, 5b has been an amazing season, with literally no bad episodes. 911 writers y'all are doing the GOOD shit recently, keep it up. but stop fucking doing insect episodes those are the fucking worst

#911 show#911 on fox#911 meta#911 s5#911 spoilers#eddie diaz#evan buckley#bobby nash#henrietta wilson#karen wilson#maddie buckley#chimney han#albert han#taylor kelly#ramon diaz#krowabbey

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

with the comfort of a billion stars (and you)

chimney and eddie get high in eddie's backyard and talk about what it means to be a good father

because of @hetheybuck's tags on this post about chimney and eddie being blaze buddies

drug use | sweet conversations | stargazing

1,691 words

AO3 link

Chimney wrapped his arms around himself instinctively as he slipped out into Eddie’s backyard, rubbing his hands rapidly along the tops of his arms as he breathed out, watching his air puff out into the cold like white smoke before quickly dissipating. The bite of the cold air against his skin was a welcome reprieve to the flush brought on by too many bodies in too small of a space.

He thought he was alone for a moment, leveling out his breaths and staring up at the sky, squinting as if he could stare just long enough to actually be able to make out some stars in the black of the LA sky—before he heard another sharp intake of breath from his side. He turned, staring down the line of Eddie’s backyard, surprised to find Eddie there, alone, curled up on a lawn chair, head tipped back as he blew out a soft puff of smoke, a joint dangling from his fingers. Chimney blinked, hesitating just for a second, before he stepped off Eddie’s porch and made his way over to the chairs.

“I didn’t know you smoked,” Chimney called out as he neared him. Eddie’s head tipped back forward, eyes wide, then squinting in the dark as he tried to make out who was approaching him. The corners of his lips curled up into a soft smile.

“Every once in a while. It was a bit much in there,” He explained with a shrug. Chimney smiled back at him before settling down into the chair next to Eddie.

“I hear ya.”

Eddie smiled again, glancing down at the ground and nodding a bit before stretching his arm out towards Chimney. He shuffled the joint between his fingers, holding it out in offering. Chimney considered it and then looked back at Eddie, eyebrows raised.

“You sure?”

“Course, Chim. It’s my house. What kind of host would I be if I didn’t share?”

Chimney nodded appreciatively, taking the joint and holding it up to his mouth, inhaling gently. It’d been a while since the last time he smoked and he struggled to maintain a cough, tipping his head back against the chair like Eddie had and releasing the smoke back into the air.

“God,” He said on the exhale. “It’s been a while.”

Eddie hummed in acknowledgment, taking the joint back from Chimney’s stretched out hand.

They didn’t say anything for a couple of minutes, both of them staring up at the night sky, trading off the joint every once in a while, in comfortable silence.

It was nice, Chimney thought, getting to have this quiet moment with Eddie. They didn’t get to do this often; always racing off to different emergencies or juggling conversations with everyone else on the team. This was nice. He felt loose and relaxed—and maybe that had something to do with the weed—but he was also pretty sure it had something to do with Eddie, and maybe something to do with how dark the sky was, and how instinctively he knew that staring up there were actually billions of stars in the sky, and how actually he wasn’t staring at some flat surface but rather the entire universe that expanded all around them, and how even though he couldn’t see any stars, light from those stars was currently traveling at speeds he’d never ever be able to comprehend, and how some of those stars that he couldn’t see but could see under different circumstances were actually dead, like long dead, and how some stars were dying at right this very second, and how some stars were being born this very second, and how all of that made him feel very small and comforted and insignificant and important all at the same time.

He was a little high.

When Eddie’s hand knocked against his, joint stretched out between his fingers, Chimney laughed a little and waved him off. Eddie smiled, taking one last drag before tapping it out on the ashtray next to him and setting it down.

Another moment of silence stretched between them. Chimney furrowed his eyebrows.

“I’m scared of being a terrible dad,” He said suddenly, no idea where the thought came from. He saw Eddie nod slowly from the corner of his eye, like he was fully expecting Chimney to say that.

“How do you do it?” He asked, turning to face Eddie, who turned back towards him, eyebrows raising. “With Christopher. How do you...how do you...not mess it up?”

Eddie snorted and took a deep breath before answering, the corners of his lips curling softly.

“I mess up all the time, Chim.”

Chimney frowned. That’s not at all what he wanted Eddie to say.

“You’ll mess up,” Eddie continued, turning forward again, his face serious. He looked back up at the sky and sighed, rolling his neck from side to side. Chimney waited for him to say more but he didn’t.

“That doesn’t actually make me feel better, Eddie,” Chimney pointed out. Eddie giggled a little. It made Chimney giggle a little, though he kept trying to force his face back down into a scowl. This was serious. He was serious.

“No, I know,” Eddie straightened up in his chair. “I think...I think the sooner you realize that you will mess up—the less you’ll...mess up.” Chimney blinked and Eddie frowned, face scrunching up like he was trying to work exactly what he was trying to say. “I mean. We’re in charge of this...little life, now, you know? Sometimes I still feel like a kid myself but—I’ve got to be responsible for my actual kid now. And...I don’t know what I’m doing most of the time. My parents weren’t...the best examples. So I’m just...doing my best. That’s all we can do.”

He nodded again, more confidently this time, solid. Eddie turned back to Chimney.

“I think Christopher’s okay, right?”

“Eddie,” Chimney said, voice stern. “Christopher is amazing. And you do this all on your own. I can’t imagine. I’m...so lucky to have Maddie.”

“I don’t really do it alone,” Eddie smiled. “Buck helps a lot. And we have Carla.”

“You're his dad,” Chimney felt the need to remind him. Eddie ducked his head, smiling wider, prouder.

“I am.”

There was a pause. Chimney watched, transfixed as Eddie dug the heel of his shoe into the dirt in front of him, dragging abstract patterns into the ground. It was fascinating.

“I think we’re too hard on ourselves,” Chimney said. Eddie snorted again.

“That’s what Buck says.”

“He would know.”

“He would know.”

Another pause.

“I don’t want to be like my dad.”

“You won’t be.”

“Are you sure?”

Eddie sighed, flattening his foot and dragging it through all of the lines he had just made. Chimney was pretty sure he heard his heart break. Over the dirt art.

“Well, you will be, sometimes, in tiny ways. But you’re not him. You’re...parts of him, parts of your mom, and parts of you, you know?”

“I hope I’m mostly parts of my mom.” His voice sounded wistful.

“You’re mostly parts of you.” Eddie didn’t see the way Chimney’s face pinched in disappointment, still staring at the patch of dirt on the ground.

“I’m not sure that’s a good thing.”

“It is,” Eddie’s tone was determined and final—and with that he pulled his legs back up into the chair and leaned back, blinking back up at the stars. He looked strikingly childlike, loose and relaxed.

Chimney sniffed. He felt—he felt warm. It was cold out but he felt this warmth radiating from somewhere in his chest or maybe his stomach—somewhere in his core, he wasn’t really sure—and it spread everywhere throughout his body. He almost felt like it spread even further, encompassing Eddie and his backyard and his house along with everyone inside it and all of LA.

The last few months had been hard. The last couple of years had been hard. Hell—life had been hard. And sometimes it was easy for Chimney to get lost in that; to look at Maddie fighting to pick herself back up, to look at Albert pushing to become a firefighter, to watch the Lees take on his kid brother and watch him go through the same process their dead son had, to watch Eddie and Bobby recover from their shootings, to watch Bobby and Athena mend their relationship, to watch Buck fall apart and stitch himself back together, to watch Hen and Karen grow attached to Nia only to lose her when they had expected it all along and somehow that hurt worse, to pretend through it all that he could shoulder the responsibility of having it all together, to be the friend and partner and father that he knew he needed to be.

It wasn’t about him—but it was. And he felt heavy and tired.

But sitting next to Eddie, a little high, comforted by Eddie’s sincere words—Eddie who would never sugarcoat it, would never lie, who always chose his words with careful intention—he felt lighter. Looking up at the sky, feeling the presence of stars young and old, alive and dead, feeling but not seeing, knowing that just inside were all his friends and family, laughing and reconnecting and healing after months and years of trauma, knowing that all around them billions of lives were being lived. And while bad things happened and people got hurt—good things happened too.

Good things like his baby girl being born. Good things like his baby brother making it out of a terrible car accident.

Good things like survival and healing and happiness and love. Things that persisted.

It was all around him constantly. He didn’t feel it all the time—but he did then.

“Hey, Eddie? I love you.”

Eddie stilled for just a second before his face cracked into a wide grin and his shoulders started to shake as he giggled, again.

“I love you too, man.” Chimney swiveled around in his seat.

“No, seriously, I mean it. Family we chose, right?”

Eddie’s giggles died down and he studied Chimney’s face carefully, smile softening, before nodding.

“Yeah, Chim. Family we chose.”

#my fic#title *sounds* romantic but its not fjjfjd#haven't written in like a month and this is what just...came out#*shrug*#911 fox#i think eddie would be a v comforting presence while high#drugs tw#al talks

34 notes

·

View notes

Link

October 22, 2019 at 08:00AM

In 1978, at the age of 18, Celine Sabag took a trip to Israel. There, she met a 25-year-old bus driver and spent three weeks touring Jerusalem with him. “He was nice and polite,” she recalls. When the man invited her to his parents’ empty apartment, she accepted the invitation. The pair had been sitting together and laughing for about an hour when the door opened. “I turned to look,” says Sabag, “and my gut told me: ‘Something awful is about to happen.’” Four young men were standing in the doorway. They entered the living room, the fourth locking the door behind him. “I believe they had done it before,” she says.

Sabag returned that night to her hotel, and then fled back to her home in France. She felt guilt and shame, and did not tell anyone that five men had raped her that night in the apartment. Shortly after her homecoming, she tried to commit suicide, the first of many attempts. Desperate for help, Sabag entered therapy. She saw psychiatrists and psychologists and started taking psychiatric medication. She also tried alternative approaches like movement therapy. Though some of the treatments helped, they didn’t eliminate the relentless flashbacks of the rape, her overwhelming fear of unknown men in corridors and on elevators and stairways, and other symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

In 1996, Sabag, who is Jewish, immigrated to Israel in the hopes of finding some kind of closure. She volunteered at a hotline for sexual assault survivors. “I wanted to let victims have someone who would listen,” she says. “Because I didn’t ask for help, so I wasn’t listened to.” Yet the suicide attempts did not cease until 2006, when a friend suggested that Sabag enroll in a specialized self-defense course offered by El HaLev, an Israeli organization founded in 2003 to offer self-defense training to women who have been traumatized by sexual assault, as well as other vulnerable groups. At first, Sabag was dubious. “I said: ‘Fighting? No way. What do I have to do with fighting?’”

But in fact, a growing body of research indicates that self-defense training can enable women to cope with the threat of sexual violence by providing a sense of mastery and personal control over their own safety. Within this field, some studies have examined a unique and pressing question: Can therapeutic self-defense training be an effective tool for sexual assault survivors who experience PTSD and other symptoms of trauma? Though the research is preliminary, some therapists and researchers believe the answer is yes.

“While ‘talk-based’ therapies are undoubtedly helpful, there is a need for additional modalities,” says Gianine Rosenblum, a clinical psychologist based in New Jersey who has collaborated with self-defense instructors to develop a curriculum tailored to female trauma survivors.

Researchers who study self-defense for sexual assault note its similarities to exposure therapy, in which individuals in a safe environment are exposed to the things they fear and avoid. In the case of self-defense training, however, participants are not only exposed to simulated assaults, they also learn and practice proactive responses, including — but not limited to — self-defense maneuvers. Over time, these repeated simulations can massively transform old memories of assault into new memories of empowerment, explains Jim Hopper, a psychologist and teaching associate at Harvard Medical School.

Sabag was not familiar with these theories back in 2006; however, she eventually decided to enroll in the self-defense training. Perhaps, she thought, it would help her be less fearful of others.

In a 2006 video she shared with Undark, Sabag can be seen lying on the floor of a gym at El HaLev. She’s surrounded by roughly a dozen women showering her with encouragement. A large man dressed in a padded suit and a helmet — referred to as “the mugger” — approaches with heavy footsteps and lies on top of her. The women continue to cheer, encouraging Sabag to kick her assailant. A female trainer leans in, providing instruction. Sabag sends up a few weak kicks, connecting with the mugger. Then she gets up, swaying, and returns to the line of trainees.

In that moment of confrontation, Sabag says she felt disoriented, not sure of where she was. She had been nauseous while waiting her turn, and then when the mugger was finally standing in front of her, she froze. “My body refused to cooperate, and there was a split. My mind left my body and I was looking at my body from the outside, like in a nightmare,” she says. “Without this split, I wouldn’t have found the power to react.”

This dissociation is a coping response that can allow some people to function under stress, says Rosenblum. But, she adds, “it is preferable for any therapeutic or learning environment to facilitate non-dissociative coping.” In a 2014 paper describing the curriculum they developed, Rosenblum and her co-author, clinical psychologist Lynn Taska, emphasize that care must be taken to ensure students remain within their so-called window of tolerance: the range of emotional arousal that an individual can effectively process. “If external stimuli are too arousing or too much internal material is elicited at once,” they write, “the window of tolerance is exceeded.” In these cases, they suggest, therapeutic benefit is lost and individuals may be re-traumatized.

Sabag often struggled to fall asleep on nights after training sessions, but she stuck with the course and even enrolled a second time. Knowing what to expect made a difference, she says. Though she still experienced flashbacks and disassociation, the nausea and shivers subsided in the second course, and she felt increasingly present in her body. Sabag explains that these changes allowed her to concentrate and hone her actions: “The kicks were precise, the punches were correct,” she says. “In the sharing circles, I wouldn’t stop talking.”

Sabag went on to become an instructor for IMPACT, an organization with independent chapters around the world, including El HaLev in Israel. IMPACT offers classes in what is sometimes referred to as women’s empowerment self-defense, which was initially developed in the 1960s and ’70s, although its roots go back even further. Traditional forms of self-defense, such as martial arts, were developed by and for men. Though they can be effective for women, they require years of training and don’t address the dynamics of sexual violence. Most sexual assaults are committed by someone the victim knows, for example, but traditional self-defense classes don’t offer the special knowledge and skills needed to fend off an assailant who is known, possibly even loved, by the victim.

In 1971, the empowerment self-defense course called Model Mugging was the first to use simulated muggings, with the goal of helping women overcome the fear of being raped. With roots in Model Mugging, IMPACT courses were developed with input from psychologists, martial artists, and law enforcement personnel.

Today, empowerment self-defense courses are offered by a variety of organizations. Though the trainings vary depending on who is offering them, they share some commonalities, including the use of a female instructor who teaches the self-defense techniques, and a male instructor who dons a padded suit and simulates attack scenarios. In some of the scenarios, the male instructor plays a stranger. In others, he plays a person known to the victim. A therapist also provides guidance in helping participants set appropriate interpersonal boundaries.

Over time, specialized empowerment self-defense courses were developed for sexual assault survivors, as well as for men, transgender people, persons with disabilities, and others. Crucially, the therapeutic classes for survivors of sexual assault require collaboration with mental health professionals. In some cases, psychotherapists provide support during the trainings. In other cases, they may recommend that their clients take a course and then provide support during psychotherapy appointments.

“Participants in this kind of course have to be in treatment,” says Jill Shames, a clinical social worker in Israel who has spent more than 30 years teaching self-defense courses to sexual assault survivors. In Shames’ courses, participants sign an agreement allowing her to communicate with their therapists. “The therapist has to agree to be involved in the process,” she says.

In the early 1990s, researchers began to study the psychological effects of empowerment self-defense classes, with multiple studies finding that women who participate experience increased confidence in their ability to defend themselves if assaulted. This sense of self-efficacy, in turn, has been linked to a range of positive outcomes.

In a paper published in 1990 in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Stanford researchers Elizabeth M. Ozer and Albert Bandura described the results of a study in which 43 women participated in a program based on Model Mugging. The trainings occurred over a period of five weeks. Among the participants, 27 percent had been raped. Before the program, the women who had been raped reported a lower sense of self-efficacy regarding their ability to cope with interpersonal threats, such as coercive encounters at work. These women also felt more vulnerable to assault and exhibited more avoidant behavior. They experienced greater difficulty distinguishing between safe and risky situations, and reported being less able to turn off intrusive thinking about sexual assault.

During the self-defense program, participants learned how to convey confidence, how to deal assertively with unwanted personal encroachments, and how to yell to frighten off an attacker. “Should the efforts fail,” the authors wrote, the participants were “equipped to protect themselves physically.” In the trainings, the women learned how to disable an unarmed assailant “when ambushed frontally, from the back, when pinned down, and in the dark.” Because women are thrown to the ground in most sexual assaults, the authors wrote, “considerable attention was devoted to mastering safe ways of falling and striking assailants while pinned on the ground.”

Each woman was surveyed before, during, and six months after the program’s completion. To identify non-treatment effects, roughly half the subjects participated in a “control phase” in which they took the survey, waited five weeks without the intervention, and then took the survey again just before the program commenced. (Researchers found no significant changes in the survey results during the control phase.)

For program participants, sense of self-efficacy increased in several realms, including their ability to defend themselves and control interpersonal threats. Perhaps most notably, in the months after the training, the women who had been raped no longer differed on any measures from the women who had not been raped.

More than a decade and a half later, in 2006, researchers from the University of Washington in Seattle and the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, which provides medical services to veterans and their families throughout the Pacific Northwest, conducted a study that looked specifically at female veterans with PTSD from military sexual trauma. Because all of the participants had been trained in physical and military fighting techniques, the study could test the idea that specialized self-defense courses foster a better sense of safety and security than military or martial arts training.

The study participants attended a 12-week pilot program that consisted of education about the psychological impacts of sexual assault, self-defense training, and regular debriefings. By the end of the study, participants reported improvements on a number of measures, including the ability to identify risky situations and to set interpersonal boundaries. They also experienced decreased depression and PTSD symptoms.

Because the VA study was small, self-selected, and lacked a control group, its authors noted that further study is necessary to determine whether wide-scale adoption within the VA is warranted. This echoes the views of self-defense proponents who say the field is promising, but in need of more research. For now, Hopper explains that the healing reported by participants of these classes may be due, in part, to a process known as extinction learning. In therapeutic self-defense classes, extinction learning occurs when the mugger provides a reminder of the assault memory. But this time, the scenario occurs in a new context, so that one’s typical responses “are over-ridden by new, nontraumatic responses.”

Whatever its potential merits, the use of self-defense training as therapy is far from universally accepted, and not all mental health providers are on board. “My therapist colleagues are wary of self-defense,” says Rosenblum. “They often are anxious about the class re-traumatizing clients.” Several years ago, she attempted to run a therapist-only self-defense class, but had trouble filling it. For this reason, Rosenblum believes it is important to emphasize that specialized classes do not push students outside their window of tolerance, and that students are, in fact, encouraged to set boundaries.

But a lack of standardization can be problematic. “Self-defense started as a grassroots movement, but it’s becoming an industry,” says Melissa Soalt, a former therapist and pioneer in the women’s self-defense movement. “Today I hear about instructor-training courses that take as little as a week, with instructors who have no clinical experience or knowledge,” she says. “Also, self-defense is not easy and it doesn’t always work. If someone is telling you otherwise, they’re not telling the truth.”

Soalt herself served as an expert witness in a trial where a young woman sued a self-defense instructor and won. According to her, the instructor was not properly trained, and he caused the woman to become re-traumatizated. “Safety is number one here,” says Soalt, who stresses that this was an extreme case. Nonetheless, she adds: “When choosing a self-defense course, it’s essential to check out the instructors.”

Indeed, when self-defense is taught with or by professionals with a background in trauma treatment, “the few studies that exist consistently demonstrate its potential,” said Shames, the clinical social worker in Israel, though she acknowledges that self-defense as a therapeutic modality remains a tough sell.

To encourage further standardization, Rosenblum and Taska’s paper describes the features of an IMPACT self-defense class. “The next step for research would be to obtain a grant [to] create a formal therapeutic class protocol and have that same protocol used in a number of locations by staff who had all underwent the same training,” says Rosenblum.

The now-defunct National Coalition Against Sexual Assault (NCASA) developed guidelines for choosing a self-defense course. While originally written for women, they were later updated by a member of the original NCASA committee to include men as well. These guidelines stress that “people do not ask for, cause, invite, or deserve to be assaulted.” Therefore, self-defense classes should not cast judgement on survivors. Further, during an assault, victims deploy a range of responses. Many even experience a state of involuntary paralysis. According to the guidelines, none of these responses should be used to cast blame on the victim. Instead, “a person’s decision to survive the best way they can must be respected.”

Ideally, a course will cover assertiveness, communication, and critical thinking, in addition to physical technique, the guidelines state. And while some women may benefit from a female instructor, “the most important aspect is that the instructor, male or female, conducts the training for the students geared to their individual strengths and abilities.”

Self-defense courses and instructors that say they aim to meet these or similar criteria are currently available through IMPACT, and through the U.S.-based National Women’s Martial Arts Federation and the U.K.-based empowerment self-defense nonprofit Action Breaks Silence.

Sabag recently turned 60. She currently works as a fitness coach for older persons, and she assists students who immigrate to Israel. She is a devout yoga practitioner and has developed an interest in Eastern philosophy. Over time, she says, she has gradually managed to reconnect with her body.

Sabag estimates that she trained considerably more than 100 women and teenage girls in empowerment self-defense. “In the future, or in my dreams, I would like to go back to teaching girls how to set boundaries and show self-confidence,” she says. “I believe that this is where everything starts.”

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

0 notes