#im realizing that not only was i wrong about this but i also severely overestimated my ability

Text

i think the most frustrating thing about being upset for whatever reason is trying to voice it and then being misunderstood because you can’t word it properly

#like im genuinely#so upset lmao#rant in the tags ig bc i need to get it off my chest#i finished this ux design course thinking that because i like design and am.. slightly good at graphic design stuff enough to#sell commissions for rp stuff#that it would be pretty good for me#but as soon as i finished it and started working on my portfolio for it i had this overwhelming sense of making a mistake#and now my portfolio is at an okay place where i can use it to apply ( or i thought lmao but thats another story entirely )#im realizing that not only was i wrong about this but i also severely overestimated my ability#and i keep trying to put it into words and all that comes out is that#i feel like i made a mistake#because i don't have the experience#and to get the experience you need networking skills and to know people and all of that#but that's legitimately the One thing i know for a fact i fucking suck at#and no one i talk to is /listening to me/ about it#so i've just been sinking deeper into this hole and i can't see myself crawling out of it#and i feel like i keep wasting time and wasting opportunities to try and save money or make money so i can leave this#shitty ass house and my shitty abusive family#and ALL OF THAT is bleeding into literally everything else lmao#anyways i hate myself

1 note

·

View note

Text

[00:15]

pairing: (now) Boyfriend! Donghyuck (who has a problematic family) x reader (who also has a very problematic family)

genre: fluff, crack

warnings: hyuck hurts his shoulder LMAOO

word count: 813 words

a/n: IM LEAVING FOR LIKE 12 DAYS IN 5 HOURS HAVE THIS SHORT ASS (continuation of the last hyuck x reader) DRABBLE AS A GOODBYE AND APOLOGY :') THANKS BABES <33

networks: @knet-bakery @neoturtles @kokonomi

part i, part ii, part iii, part iv

2 weeks ago, (now) boyfriend! Donghyuck proposed running away, a week ago your parents had their biggest fight yet, not with each other, but with you.

Today—no, tonight, you plan on running away with Donghyuck.

There are familiar taps at your window, from pebbles, that cause you to instantly spring up from your seat and open the window. There he stood, a small smirk on his face as he flicked a pebble at you.

“Ow- what the fuck?”

“Shhh, give me your bag.”

You stick your tongue out at him for a second, before you’re running back in to retrieve your duffle bag. It’s finally happening, you’re running away from your parents, with the only person who actually cared about you.

Donghyuck feels just as relieved, he can do whatever he wants now, without a care of if his family caught him doing it. He’s got a whole luggage full of his stuff in the backseat of his car, and it’s filled with years worth of belongings.

Donghyuck feels just as relieved, he can do whatever he wants now, without a care of if his family caught him doing it. He’s got a whole luggage full of his stuff in the backseat of his car, and it’s filled with years worth of belongings.

You appear back at the window with your large bag, carefully dropping it into Donghyuck’s grasp with a small thump. You wince at the sound, for it is literally dead in the night, where everything is asleep. You can’t afford to make loud noises that could wake your parents.

Donghyuck shoves your bag right next to his, making sure it’s secure and won’t topple over when the car’s moving. He then sprints back to the window, the whole story high window, where you sat and got ready on the window sill.

“Hooooly shit okay uhhh,” you mumble nervously, watching your legs dangle several feet off the ground. Your gaze adverts to your boyfriend, who’s arms are stretched out and ready to catch you. You give him a confused look, “The fuck? Hyuck I thought you said you’d bring a ladder?”

His confident stare wavers as he bites his lip, “Uhhh it was too risky to get out of the shed...”

A hard facepalm drags across your face, as thoughts of how this dumbo is the one saving you from your parents.

“Come on, just jump! I’ll catch you!”

“Do you think that’s enough for me to jump?! You’re fucking lanky!”

Donghyuck holds back the urge to argue how he’s been working out recently, instead just sighing and reaching his arms further up for you. A silent groan erupts from your chest, and you only look down nervously.

Well, he can’t be that weak, right?

With one last pro in mind, and many many moments of hesitation, you jump off your window, holding your breath to try not to scream. Your arms reach out for Donghyuck, as he tries to catch you as swiftly as he can.

Unfortunately, swift is not a very good word in his dictionary, as he stumbles the second he’s caught you. He takes you two down onto the grass, noises of pain emitting from the both of you. You were wrong, he does not have the muscle to catch a person from a story high.

“Oh shit! I overestimated myself way too much- ah!” Donghyuck winces in pain with every move he makes, carefully pushing you off him and grasping at his shoulder.

The second his fingers push down at his shoulder blade, he starts to groan loudly at the pain. You quickly swat his hand away from his shoulder, shushing him almost violently.

Donghyuck gives you a quick glare, but the pain in his expressions say otherwise when you break out into a grin.

You start to laugh as silently as you can in the asscrack of night, leaning to rest against Donghyuck’s other arm. A soft laugh shakes from his chest as well, as he finds the situation somehow funny as well.

Suddenly, the atmosphere is filled with relief and joyful laughter, as you eventually flop down to the grass and push at each other.

After your hard fit of (attempted) silent laughter, you pant, and turn to observe Donghyuck’s happy and pure smile you haven’t been able to see the past week.

You brush the dirt and grass out of his hair, grinning from ear to ear, “Are we really doing this?”

His gaze grows incredibly soft and comforting, it’s so hard to look away from his warm chocolate eyes. Donghyuck reaches up to hold your hand, “We’ve suffered too much.”

Pure bliss fills your body as you stand up to go to Donghyuck’s car, the adrenaline pumping throughout your emotions like it replaced the blood in you.

You’re finally free, you don’t have to deal with petty bickering and spiteful insults. You don’t have to dread going home because you realize now, that the person next to you, who’s driving his car, who’s holding your hand and stroking it lovingly, who was willing to help you escape, to catch you from a story high, is your home.

#knet bakery#neoturtles#lee donghyuck imagines#lee donghyuck#lee donghyuck fluff#lee donghyuck x reader#lee haechan#lee haechan x reader#haechan imagines#nct imagines#nct fluff#nct x reader#nct 127 imagines#nct 127 x reader#nct dream imagines#nct dream x reader#nct scenarios#nct timestamps#nct drabbles#nct blurbs#nct 127#nct dream#nct haechan#fullsun

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

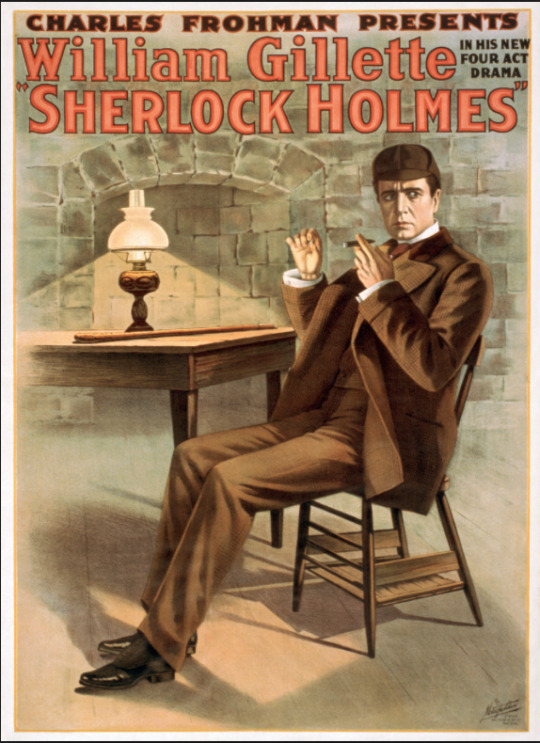

Sherlock Holmes, 1899: Detective 2.0 (Part 1)

Note: As always, please let me know if you want to be tagged or untagged :)

… Look, I said I wasn’t going to write about this one. And I know that it hardly counts as an. ‘obscure’ adaptation, although to be fair it doesn’t appear often in tumblr discussions. But Sherlock Holmes by William Gillette is the first ever licensed Holmes adaptation, so of course I had to read it, and then I had thoughts and—well, here we are.

This is the fourth installment of my series on obscure Sherlock Holmes adaptations. For a master-list of previous write-ups, see this post.

Production and Reception

William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes exists in two primary iterations. The first is a play released in 1899 (you can read the script here), and the second is a 1916 silent-film starring several of the stage actors, including Gillette as Holmes. This post will discuss the play only; I will review the film in part 2.

The original script for Sherlock Holmes was written by Doyle, but his script was rejected and heavily reworked by William Gillette. Gillette’s script showcases an original plot, although it features Moriarty and Alice Falukner, a loose Irene Adler analogue. Disappointingly, the parallel between Alice and Irene is purely circumstantial: Alice has much of Irene’s courage but none of her active cleverness, and is reduced to a paper-thin damsel-in-distress. This is even more unfortunate given that—contrary to Doyle’s wishes—Gillette makes her Holmes’s love interest, thus initiating the hellish proliferation of Adler/Holmes storylines. So … thanks for that one, Gillette.

The play was wildly successful, and Alan Barns asserts that it has been “crucial to the development of Sherlock Holmes on film … [i]ts impact cannot be overestimated.” Even Doyle appears to have softened towards the play after seeing it performed, and is quoted by Vincent Starrett as saying: “I was charmed both with the play, the acting, and the pecuniary result." Whether Doyle was more pleased by the art or the currency is perhaps unclear.

For myself, insofar as it is the first Holmes adaptation I find this play fascinating; but insofar as it is just one of many retellings, my feelings are mixed. I confess I kept comparing it to Doyle’s stage adaptation of The Speckled Band (you can read the script here and my analysis here), and Gillette’s play seldom looked better for it. I found Doyle’s plot more compelling, his villain more threatening, and his characters more vibrant. All the same I was not bored reading Gillette’s play, got a few laughs, appreciated Gillette’s Watson and was intrigued—if not wholly pleased—by his Holmes.

But I hope you don’t think me terribly petty if I confess that I struggle to entirely forgive Gillette for launching the legacy of Holmes adaptations with a ‘straight’ Holmes.

William Gillette as Sherlock Holmes

There are things I quite like about Gillette’s Holmes. He is deeply composed, but fully capable of action and self-defense. He has plenty of snark, is openly affectionate with his Watson, yet is deeply troubled—he cannot be accused of being without feeling.

Nevertheless, I suspect that he played a large role in establishing the stereotype of the hard-boiled detective, the DFP, the detached and cold-hearted reasoning machine. Gillette consistently leans into Holmes darker and more reserved qualities: his Holmes is almost always composed and never excited—although he is often quietly amused—and there is little sense of his love for an audience. The extremity of his cocaine habit is emphasized, to the point that he is clearly suicidal—an aspect that is belabored rather frequently.

But the thing that really irks me is the case. The case is loosely based on A Scandal in Bohemia, in which Holmes is working for a prince in an attempt to gain incriminating letters/pictures from a woman. Scandal is an anomaly in the canon insofar as Holmes is not strictly on the side of justice—either in the audience’s eyes or his own—and yet goes through with it (x). This is distinctly unusual for a man who ordinarily allows nothing, including the law, to sway him from what he sees as true justice. And yet it is this dark deviation that Gillette chooses as the framework for presenting Holmes to a new and wider audience.

And look—there’s nothing wrong with exploring Holmes’s darker side. But I still struggle with the characterization on two levels:

I’m not saying the persistence of this darker Holmes in public imagination was Gillette’s fault; he’s hardly responsible for all adaptations that followed his. I just … I just would have liked the legacy of Holmes adaptations not to begin with a straight, hard(er)-hearted Holmes.

Frankly, I find the ‘borderline-cruel straight white guy is redeemed because a pretty young girl saw his secret golden heart’ plot infinitely more tired and less compelling than the complex, transgressive, damaged, but deeply kind character Doyle created.

Edward Fielding as John Watson

If Gillette perpetuated some of my least favorite Holmes stereotypes, on the whole the same cannot be said of his portrayal of Watson. Yes, Watson is sidelined to make room for Alice, and like the other characters in the script I found him a bit … flat. But he is never portrayed as a fool, his role was somewhat larger than I expected, his connection to Holmes is palpable, and if I had a checklist of characteristics a good Watson ought to posses, he would do a surprisingly good job checking them off.

The first thing we know of Watson is Holmes’s affection for him. The second is Watson’s protectiveness of Holmes as he expresses his distress over Holmes’s cocaine habit and the danger posed by Moriarty. We also get a sense of Watson’s attraction to danger when he observes, “this is becoming interesting,” as matters become tense.

My favorite moment, however, comes near the end when Watson is alone and two false patients come in, attempting to set a trap for Holmes. Watson not only catches on to their facades immediately, he also notices that the blind had been raised when he briefly stepped out of the room. So thanks to Gillette’s script, we get to see Watson be clever, observant, and a great doctor all at once—a rare occurrence in early adaptations.

As much as I enjoy this scene, however, it also gets at my one major disappointment with Gillette’s Watson: although he is entirely capable, he is never given anything to do. In this instance, when Watson realizes his ‘patients’ are setting a trap he begins to act; but then Holmes appears and takes charge. Later Watson blocks the window and closes the blinds to avoid a signal being sent out to Moriarty—but only at Holmes’s instructions. And this, sadly, is the consistent pattern of the play.

In the end, I was left with a confusing dual sense that on the one hand Gillette seems to have a fairly good grasp of Watson and his capabilities, but on the other doesn’t really seem to know what to do with him. He seems to know that Watson is important, but not how he is important.

So … What About Johnlock?

After everything I’ve said, that’s clearly a hard ‘no,’ right? Well, sort of—they certainly aren’t riding off into the sunset together, but I still find myself with rather too much to say on this topic. To my mind, there are four categories worth touching on: a). The relative strength of the Holmes/Alice relationship vs the Holmes/Watson relationship, b). subtext carried over from Doyle’s stories, c). queer elements of the Holmes/Alice relationship, and d). assorted moments.

a). Holmes/Alice vs Holmes/Watson

Here’s the thing: my complaints about the Holmes/Alice romance aren’t just because Holmes is gay and in love with Watson. They are also because Gillette couldn’t have written more of a dime-a-dozen (+vaguely sexist) hetero romance if he tried. Here is a point-by-point summary of their ‘relationship’:

Holmes is on the point of further stripping agency away from a helpless girl who has been physically and psychologically abused for months.

Alice cries.

Holmes doesn’t do the cruel thing (he’s still planning to do it, but Alice doesn’t know).

They are now in love.

I’m not exaggerating here: in terms of length the above scene is hardly a blip in the play, and yet next time they see each other Alice is saying that if Holmes dies she wants to die too. Yep.

On the other hand, the relationship between Sherlock and Watson is established and their care for one another is palpable. Watson first appears immediately after Holmes refuses to see Mrs. Hudson, clearly wishing to be alone. But then his boy Billy comes up, and this exchange follows:

BILLY: It's Doctor Watson, sir. You told me as I could always show 'im up.

HOLMES: Well! I should think so. (Rises and meets WATSON.)

BILLY: Yes, sir, thank you, sir. Dr. Watson, sir!

(Enter DR. WATSON. BILLY, grinning with pleasure as he passes in, goes out at once.)

HOLMES (extending left hand to WATSON): Ah, Watson, dear fellow.

WATSON (going to HOLMES and taking his hand): How are you, Holmes?

HOLMES: I'm delighted to see you, my dear fellow, perfectly delighted, upon my word.

The affection, intimacy, eagerness for one another’s company, and trust evident in these first lines remains throughout the script, and puts Holmes and Alice’s hurried and stilted relationship to shame.

Ultimately Holmes marries Alice and Watson is sidelined, but the relationship between him and Watson remains the more palpable and affecting.

b). Subtext carried over from Doyle’s stories

There are at least two threads that are strongly reminiscent of subtextual cornerstones in Doyle’s canon. Perhaps they are intentional, or perhaps Gillette borrowed them from the stories/Doyle’s original script without reading them the way we do, but they exist nonetheless.

The first is Holmes’s cocaine use. In the canon Holmes occasionally claims that he uses drugs to escape the crushing boredom of inactivity between cases, but The Sign of Four in particular makes it clear that he also uses them for emotional comfort—specifically to cope with loosing Watson to Mary. A similar pattern is evident in Gillette’s play: his Holmes claims that

the threat of Moriarty “saves me any number of doses of those deadly drugs,” and yet Watson points out that Holmes has been using the drugs “in ever-increasing doses” despite the fact that he has been engaged in his most all-consuming case—fighting Moriarty—for fourteen months. But the cause of Holmes’s increasing drug use and attendant suicidal depression is far less clear in here than it is in the canon.

Hollow as his semi-frequent ‘because I’m bored’ explanations ring in light of Moriarty, I am inclined to think Holmes is most honest near the end when describing his distress over his treatment of Alice:

HOLMES (turning suddenly to WATSON): Watson—she trusted me! She—clung to me! … and I was playing a game! … a dangerous game – but I was playing it! It will be the same to-night! She'll be there —I'll be here! She'll listen—she'll believe—and she'll trust me—and I'll—be playing—a game. No more – I've had enough! It's my last case!

To me this clearly reads as an ongoing distress which was brought to a head by Holmes’s association with Alice rather than originating with it—“I’ve had enough! It’s my last case” indicates that the dilemma is linked to Holmes’s work as a whole, not the affair with Alice particularly. The surface (and likely intended) reading of this is that the work was a decent antidote for boredom for a time, but was ultimately too empty of real connection to be fulfilling in the long term, resulting in Holmes’s ultimate spiral into depression.

However, it also works surprisingly well for a queer reading: Holmes’s prior life was in some way a facade, “a dangerous game” perhaps involving the ongoing deception of someone he cared about. Interesting ...

A queer reading of his deterioration is further supported by the fact that Watson is married in this story. While we don’t now how long he has been married, one wonders whether his absence might coincide with the increase in Holmes’s drug habits—it seems possible that Gillette recognized the link between cocaine and Watson’s marriage in the cannon and intended committed fans to likewise make the connection in the play.

Another interesting moment comes when Holmes is lamenting ‘the good old days,’ and in theory he is complaining about the un-originality of criminals. But although he begins by speaking of what “I” used to do, later he slips into “we.” Is he really missing the old days of criminal creativity, or is he missing the time when he had a constant companion to share them with?

In short, although Gillette is likely appropriating the cocaine and never-quite-explained melancholy of the canon merely to portray Holmes having a mid-life crisis, it works surprisingly well—and in my opinion more compellingly—to read it as the fallout from the loss of his companion for whom he had socially inadmissible feelings which kept him playing a duplicitous game. (Unfortunately the side-effect of this reading might be that the solution is for Holmes to step out of the ‘dangerous game,’ leaving his old life in Baker Street in literal ashes, and into the clear light of a heterosexual relationship, which is, uh … Wrong).

One other brief matter of note: to my great amusement this play also joins canon in playing the game of the vanishing wife. Watson has scarcely entered the story before Holmes comments on Mary’s (timely as ever) absence on “a little visit,” and near the end we discover that Holmes and Watson have planned a trip to the continent (!). How long is the trip? Is Mary coming? Does she have other plans? How does she feel about her husband gallivanting off to another country with a man pursued by a master criminal??? Meh. Who knows.

Miss Plot Device does, however, appear briefly and silently offstage when Watson wants Holmes to peek in at her for a quick lesson on domesticity.

c). Queer elements of the Holmes/Alice relationship

We’ve established that their relationship is as dime-a-dozen and cringey as literary relationships come. However, in the final scenes Holmes has admitted his affection for her to Watson but believes he must set them aside for the following reasons:

HOLMES: That girl!—young—exquisite—just beginning her sweet life—I—seared, drugged, poisoned, almost at an end! No! no! I must cure her! I must stop it, now—while there's time!

And again, when Alice has confessed her love for him:

HOLMES: no such person as I should ever dream of being a part of your sweet life! It would be a crime for me to think of such a thing! There is every reason why I should say good-bye and farewell! There is every reason—

So essentially, he sees his love for almost as some sort of disease, even a crime, something that would endanger the one he loves, that he ought to resist for their sake; only he is quite wrong and that love is in fact the way to happiness for them both … Hmm. Well then.

d). Assorted

There were a few moments in the script which do not fit within a wider thematic arc, but which I couldn’t go without mentioning.

1. Upon Watson’s first appearance, Holmes greets him and then says:

HOLMES: I'm delighted to see you, my dear fellow, perfectly delighted, upon my word—but—I'm sorry to observe that your wife has left you in this way.

Okay, so Mary has only left for a visit and is back the next day, but is it just me or did Holmes make it sound like she’d left Watson for good?? Because if that was intentional, that a first-class Petty Gay antic.

2. The cocaine scene near the beginning ends with these line:

WATSON (going near HOLMES—putting hand on HOLMES' shoulder) Ah Holmes—I am trying to save you.

HOLMES (earnest at once—places right hand on WATSON'S arm): You can't do it, old fellow—so don't waste your time.

Partly I’m just struck by the tenderness of the moment, which is heightened by the stage directions. But I also wonder—why couldn’t Watson save Holmes when Alice presumably can? Apparently Holmes needs romantic affection to move forward. If he believed that Watson was capable of offering him that, would Gillette’s Holmes accept it?

3. In a confrontation with the criminals, one of them reveals that they struck Watson at an earlier stage of the conflict. Holmes’s response?

HOLMES (to ALICE without turning—intense, rapid): Ah!

(CRAIGIN stops dead.)

HOLMES: Don't forget that face. (Pointing to CRAIGIN.) In three days I shall ask you to identify it in the prisoner's dock.

Its not necessarily romantic, but I can’t pass over protective!Holmes, especially given its slight Garridebs vibe. I also can’t resist mentioning that this bit all but interrupts the first clearly romantic moment between Holmes and Alice.

4. Near the end, when Moriarty is captured and spewing threats of revenge, he declares that Holmes will encounter his retribution during his planned trip to the continent with Watson. Ever the optimist, Watson suggests that they cancel the trip, but Holmes replies:

It would be quite the same. What matters it here or there—if it must come.

There is nothing strange in the moment; what is curious is that, for all Holmes’s fears about the damage a relationship with Alice might do her, the very real threat of Moriarty is never mentioned. Realistically this is likely a bit of sloppy writing, and yet the resultant image of an omnipotent web (and yes, the spider’s web metaphor is used for Moriarty in the play) which will inescapably pursue Holmes and Watson wherever they flee and yet leaves the appropriately heterosexual Holmes at Alice alone is, um, Really Something.

5. Finally, as I wrap up I cannot resist calling your attention to a number of lines and stage directions which are (almost definitely) meaningless in context, but out of context are too delightfully gay to ignore. Here they are, presented entirely without context for your viewing pleasure:

HOLMES: Mrs. Watson! Home! Love! Life! Ah, Watson!

HOLMES: I must have that. (Turns away towards WATSON.) I must have that.

HOLMES: (Saunters over to above WATSON'S desk.)

HOLMES: Why, this is terrible! (Turns back to WATSON. Stands looking in his face.)

… I’ll just leave those there.

After everything, the question of whether Gillette might have seen or suspected a romance between Holmes and Watson is unresolved. For myself, I vacillate regularly on how likely I think it is. This excellent post gets into why it is quite likely that Gillette may at the least have seen Holmes and Watson's relationship as a homoerotic (but strictly sexless and ultimately woman-mediated) friendship. Thus at minimum he could have intended to hint at the pain of moving away from such a deeply bonded friendship. From there it is not difficult to imagine the that he could have speculated the possibility that something in their relationship or desires moved beyond what was acceptable in Victorian society. Even if he did there remain two very distinct possibilities: a). That he was secretly supportive and despite protecting himself with a socially acceptable paring tried to hint at the pain of a forbidden love and even queer-coded the heterosexual resolution, or b). That he saw himself as ‘saving’ Holmes from ‘self-destructive game’ of his old love, redeeming him through the all-healing power of heterosexuality (ugh).

On the other hand, there is also a highly eminent possibility that I’m just looking too hard, and nothing I thought I might see was intended to mean anything in that way.

Ultimately, at this stage my only conclusion is that the evidence is inconclusive. But I will say this: regardless of intention, the relationship between Holmes and Watson remains the strongest and most poignant in the play, and faithfulness to elements of the cannon results in moments that sure do make it look like something is up. If nothing else, that made me smile.

Conclusion: Should You Read It?

Well, it depends on what you’re looking for. If you’re looking for a particularly compelling/unique/vibrant take on Sherlock Holmes, or even just a story with a thrilling plot, intriguing concepts, and living characters, this isn’t a bad choice—but you could do better. (This is where I remind you that Doyle’s play, The Adventure of the Speckle Band, is genuinely excellent). But if you’re looking for an entertaining play which also happens to be the first Sherlock Holmes adaptation in existence and which had an enormous impact on every adaptation that came after—then yeah. Go read it. It’s right here! Have fun! And if you post about it, whoever you are, I would deeply appreciate a tag :)

@devoursjohnlock @thespiritualmultinerd @a-candle-for-sherlock @ellinorosterberg @cuttydarke @inevitably-johnlocked @alemizu @astronbookfilms @battledress @disregardedletters @materialof1being @sarahthecoat @spenglernot @authordrawingmusic @hewascharming @infodumpingground @rsfcommonplace @the-elephant-is-pink @johnhedgehogwatson @lokis-warrior-queen @sonnet59 @sherlocks-final-resolve-is-love @artemisastarte @tjlcisthenewsexy @nottoolateforthegame

#william gillette#sherlock holmes 1899#sherlock film meta#sherlock holmes adaptations#johnlock#sherlock holmes#John watson#Arthur conan doyle

29 notes

·

View notes