#labyrinthodon

Text

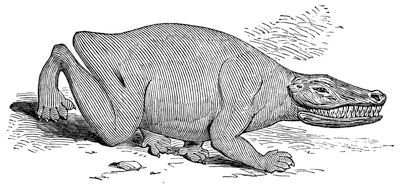

"Crapaud Labyrinthodon" [Toad-like Labyrinthodon] from Paris avant les hommes (Paris Before Man) written and illustrated by Pierre Boitard

Published posthumously as a novel with updated illustrations in 1861, first published in Musée des Familles – Lectures du Soir, 1836-1837

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6416941b/f96.item

162 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Labyrinthodon, 1854

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

LABYRINTHODON!, 2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Werewolf Fact #71 - Book Review: Sabine Baring-Gould's The Book of Werewolves

While it may not be a "werewolf fact" of the traditional nature, it's very important when studying folklore to know and understand one's sources.

One of the very best sources for werewolf folklore - and indeed other folklore and mythology besides - is Sabine Baring-Gould's The Book of Werewolves (or The Book of Were-Wolves as he called it), written in 1865. However, like any academic/rhetorical source, it shouldn't be taken at face value. Let's dive into why it's such a useful source - and why you shouldn't always take to heart everything Baring-Gould attempts to assert.

Already a scholar, Baring-Gould was a skeptical guy. It all began when, during his travels, Baring-Gould encountered several people terrified of a werewolf. He was baffled they truly believed in such a thing, and that it would stop them from wanting to traverse a road at night...

“If the loup-garou were only a natural wolf, why then, you see”—the mayor cleared his throat—“you see we should think nothing of it; but, M. le Curé, it is a fiend, a worse than fiend, a man-fiend,—a worse than man-fiend, a man-wolf-fiend.”

Baring-Gould, not intimidated, walked the road alone. However, along the way, the words of the others got to him, and he found himself frightened. The manner in which such preposterous superstition (naturally, he wasn't exactly a believer) would actually make him afraid at all made him very curious about such things and why people would believe in them...

This was my first introduction to werewolves, and the circumstance of finding the superstition still so prevalent, first gave me the idea of investigating the history and the habits of these mythical creatures.

I must acknowledge that I have been quite unsuccessful in obtaining a specimen of the animal, but I have found its traces in all directions. And just as the palæontologist has constructed the labyrinthodon out of its foot-prints in marl, and one splinter of bone, so may this monograph be complete and accurate, although I have no chained werewolf before me which I may sketch and describe from the life.

The traces left are indeed numerous enough, and though perhaps like the dodo or the dinormis, the werewolf may have become extinct in our age, yet he has left his stamp on classic antiquity, he has trodden deep in Northern snows, has ridden rough-shod over the mediævals, and has howled amongst Oriental sepulchres. He belonged to a bad breed, and we are quite content to be freed from him and his kindred, the vampire and the ghoul. Yet who knows! We may be a little too hasty in concluding that he is extinct. He may still prowl in Abyssinian forests, range still over Asiatic steppes, and be found howling dismally in some padded room of a Hanwell or a Bedlam.

Baring-Gould has his biases, but he also has an open mind about some topics, even if he's shut tighter than a bear trap on others, especially where anything scientific is concerned, as he was a big believer in the science of his time (not all of which is applicable to today). He's a complicated bag of tricks, and reading his work is quite an experience.

Whatever his biases and whatever one might think of his occasionally very judgmental and overly authoritarian words (i.e., he can sometimes think he knows better than everyone, including the people who actually lived during the time periods he's discussing), he is nothing short of phenomenal at his work of gathering and examining sources... even if he isn't always right. He contradicts his own research at least once, namely in relation to berserkers, but I won't go into all that (unless you read my edition of his book, of course; I discuss it extensively there).

He even spins some of his sources into thrilling tales. He honestly isn't bad at narration, able to paint an impressive and thrilling picture when retelling various werewolf (and other) legends...

But when dusk settled down over the forest, and one by one the windows of the castle became illumined, peasants would point to one casement high up in an isolated tower, from which a clear light streamed through the gloom of night; they spoke of a fierce red glare which irradiated the chamber at times, and of sharp cries ringing out of it, through the hushed woods, to be answered only by the howl of the wolf as it rose from its lair to begin its nocturnal rambles.

Something to note with Baring-Gould is that some of his sources are actually no longer with us. They did clearly exist, and he could access them during his own time, but they've since been lost, especially in such original formats (or they might be gone altogether). This is just another reason why Baring-Gould's work is irreplaceable as a source for many, many fields, not just werewolf studies. He cites and discusses works about many kinds of folklore, mythology, and even history, and he even provided the first English translation of the trail of Giles de Rais, a famous killer (and basis for the fairy tale Bluebeard). It's a fascinating read, even if you're just there for general folklore and mythology or if you're there specifically for werewolves or, broader spectrum, all manner of shapeshifters - he even talks a little bit about dragons!

However, when reading, bear in mind that Baring-Gould is not without his biases, as I mentioned before. He can be very judgmental of other scholars, especially from the past, but that isn't exactly uncommon even in modern scholarship. It's easy enough to read around, as long as you don't take everything he writes as fact. No scholar is perfect, no matter how impressive their work is, and that certainly includes Baring-Gould. He also approaches his work with werewolves specifically with the determination to relate them to "madmen" and serial killers, which is a consistent theme throughout the book. He will discuss werewolf legends and detail them well, but toward the end of each section, when providing his own assessment, he will generally offer how such things could be rationalized in his own mind. In doing so, of course, he does offer interesting discussion and food for thought, regardless of whether you agree with him (I agree with him at times but can also find him very disagreeable; it's like that with most everything one reads, so no shocker there). And, of course, his work even if only used for informational purposes is still impressive.

Biases is no reason to pass on what might be the best single source on these many topics. Besides, reading around potential biases is a skill everyone should learn.

One of his biggest downsides is that he doesn't provide English translations of all his quoted passages and sources. This was a problem in the original publication from the 1800s, and it continues into today with nearly all editions...

However, if you do want translations of nearly all of his quoted passages from various sources (as well as extensive annotations discussing werewolf studies, mythology, and more, and putting his scholarship into a modern context and even pointing out his errors, such as when he contradicts himself), then you need to see my edition of his work!

I personally translated and annotated The Book of Werewolves this year, and it's now available for purchase both through Amazon.com and my personal website, with a cover that's a different take on the book's original 1865 release...

Be sure to check it out at Amazon.com and my personal website!

If you buy it directly from me, I'll sign it for you, too. You can also download an ebook, if you prefer.

I assure you it's the best edition of this book you'll find. I know because I've bought nearly all of them trying to find one that's at all easy to reference. My edition even includes a bibliography that will assist you with further related reading, among other useful things. I've made sure the formatting is easily readable, so it's good for both casual reading and citation/quotation in research/academic projects. This was a lot of work, and I'm very proud of how it turned out, especially as I myself have worked with this book for years.

Final words: even with all my own personal biases about werewolves, the study of werewolf and other legends, and my opinions on some of Baring-Gould's assertions, I have to give Baring-Gould's work a 10/10 for being a must-read for anyone interested in werewolves. Trust me - if you love werewolves and studying their folklore like I do, you won't be able to put this book down, and you'll walk away with far more knowledge than you had before. Reading this book alone will give you a decent foundational knowledge of werewolf studies, while also touching upon other fields.

However, of course, I do recommend reading mine. Obviously. Especially because Baring-Gould is just so wrong about berserkers (hence, my own assertions)! But anyway.

That's all for now. Until next time, and be sure to check out my newsletter linked below!

( If you like my blog, be sure to follow me here and elsewhere for more folklore and fiction, including books, especially on werewolves! You can also sign up for my free newsletter for monthly werewolf/vampire/folklore facts, as well as free fiction and nonfiction book previews.

Free Newsletter - maverickwerewolf.com (personal site + book shop) — Patreon — Wulfgard — Werewolf Fact Masterlist — Twitter — Vampire Fact Masterlist — Amazon Author page )

#werewolf#werewolves#werewolf fact#werewolf facts#werewolf wednesday#werewolfwednesday#folklore#folklore facts#book reviews#book review#sabine baring-gould#the book of werewolves#the book of were-wolves#mythology#wolf#wolves#early modern period#lycanthrope#lycanthropes#lycanthropy#books#clinical lycanthropy#therianthropy#shapeshifting#shapeshifters#sources#sourcebooks#resources#academic writing#reference

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stoa

“Dinosaur hybrids: Bunyip” © Richard Kuulme, accessed at his ArtStation page here

[I’m wrapping up my coverage of monsters based on hoaxes, and transitioning to monsters from literary sources. So here’s one that’s both. The stoa originally appears in The Lost World by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, where it’s depicted as being some sort of giant toad-like creature. It’s not well described, but I suspect it’s intended to be a reference to the “labyrinthodon” sculptures at the Crystal Palace.

As Karl Shuker discusses, the Czech cryptozoologist Jaroslav Mareš claims that the stoa is a creature native to the Kurupira tepui, described by the native people as being much like a modern day Carnotaurus. This is, to me, incredibly suspicious. First off, naming a tepui Kurupira is essentially calling it “Mount Monster”, and the landform is described or discussed nowhere except for in Mareš‘ books. Secondly, Mareš claims that his expeditions occurred in the 1970s, but he only published them in the 1990s... late enough for him to just copy and paste a description of a Carnotaurus, which wasn’t described until the mid 80s. Thirdly, the only link between the stoa and a Carnotaurus is the claim that its horns are like those of the horned frog, which is a comparison no actual expert would make, since the horned frog’s horns are little triangular flaps of skin and the Carnotaurus’ are bone (and probably covered with a keratinous sheath in life). And the stoa, which is described by Doyle as being like a toad, doesn’t even have horns!

So this is sort of a hybrid of the Doyle stoa and the Mareš version. I considered making it an actual chimera of a dinosaur and a toad, but I’ve done a lot of chimeras and magical beasts lately. So I made it an animal. My conception is that it’s a capitosaur, the group to which the “Labyrinthodon” fossils have been reassigned, that has convergently evolved a bipedal, dinosaur-like body plan.]

Stoa

CR 8 N Animal

This creature is larger than an elephant, with enormous jaws and short horns above its eyes. It moves on two legs, its hind legs overdeveloped and frog like and its short forelegs having flabby hands with a single clawed finger. Its skin shines with an iridescent sheen, like an oily fish, and is covered in warts and irregular scales.

Stoas are ravenous carnivores that specialize on eating smaller, man-sized prey. A stoa leaps into the air and lands on its prey, pinning them beneath its feet while tearing at them with oversized jaws. Their nervous systems are simple and resilient, making them insensitive to pain and difficult to kill. Stoas often kill more than they can eat at once, caching prey in bogs to consume later.

Stoas are native to tepuis, strange plateaus sometimes referred to as “lost worlds”. Although they closely resemble dinosaurs, they are actually large, bipedal amphibians. The oversized claw on their stubby forelimbs is used primarily as a grooming tool, but can double as a weapon in close quarters and in battles over mating rights. Stoas spend most of their time wallowing in water, but move onto land in order to hunt in order to avoid competition with crocodiles or other aquatic predators. Stoas are poor climbers, and people who live near stoa congregations often keep shelters up in tall trees or cliff faces to protect themselves.

Stoas as Animal Companions

Starting Statistics: Size Medium; Speed 40 ft.; AC +3 natural; Attack bite (1d8), 2 claws (1d3); Ability Scores Str 10, Dex 19, Con 13, Int 1, Wis 12, Cha 6; Special Qualities immune to pain effects, low-light vision, scent, weak claws

7th level Advancement: Size Large; AC +3 natural armor; Attack bite (2d6), 2 claws (1d4); Ability Scores Str +8, Dex -2, Con +4; Special Attacks crush (Small); Special Qualities ferocity, mighty leaper

Stoa CR 8

XP 4,800

N Huge animal

Init +6; Senses low-light vision, Perception +9, scent

Defense

AC 20, touch 11, flat-footed 17 (-2 size, +2 Dex, +1 dodge, +9 natural)

hp 104 (11d8+55)

Fort +12; Ref +9, Will +5

Defensive Abilities ferocity, fortification (50%); Immune pain

Offense

Speed 40 ft.

Melee bite +14 (2d10+8), 2 claws +9 (1d6+4)

Space 15 ft.; Reach 15 ft. (5 ft. with claws)

Special Abilities crush (2d8+12)

Statistics

Str 26, Dex 15, Con 21, Int 1, Wis 12, Cha 6

Base Atk +8; CMB +18; CMD 31

Feats Dodge, Improved Initiative, Iron Will, Mobility, Toughness

Skills Acrobatics +10 (+22 jumping), Perception +9, Swim +15; Racial Modifiers +8 Acrobatics when jumping, +4 Swim

SQ mighty leaper, weak claws

Ecology

Environment warm and temperate hills

Organization solitary, pair or congregation (3-6)

Treasure none

Special Abilities

Crush (Ex) A leaping stoa can land on Medium or smaller creatures as a standard action. A crush attack affects as many creatures as fits on the stoa’s space. Creatures in the affected area must succeed on a DC 23 Reflex save or be pinned, automatically taking 2d8+10 bludgeoning damage during the next round unless the stoa moves off them. If the stoa chooses to maintain the pin, it must succeed at a combat maneuver check as normal. Pinned foes take damage from the crush each round if they don't escape. The save DC is Strength based.

Mighty Leaper (Ex) A stoa does not suffer a penalty to Acrobatics checks made to jump if it doesn’t take a running start. If it does take a running start, its distance traveled is doubled.

Weak Claws (Ex) A stoa’s claw attacks are secondary natural weapons.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mastodonsaurus

By Tas Dixon

Etymology: Nipple-toothed reptile

First Described By: Jaeger, 1828

Classification: Biota, Archaea, Proteoarchaeota, Asgardarchaeota, Eukaryota, Neokaryota, Scotokaryota Opimoda, Podiata, Amorphea, Obazoa, Opisthokonta, Holozoa, Filozoa, Choanozoa, Animalia, Eumetazoa, Parahoxozoa, Bilateria, Nephrozoa, Deuterostomia, Chordata, Olfactores, Vertebrata, Craniata, Gnathostomata, Eugnathostomata, Osteichthyes, Sarcopterygii, Rhipidistia, Tetrapodomorpha, Eotetrapodiformes, Elpistostegalia, Stegocephalia, Tetrapoda, Temnospondyli, Limnarchia, Stereospondylomorpha, Stereospondyli, Capitosauria, Mastodonsauridae

Referred Species: M. jaegeri, M. cappalensis, M. giganteus, M. torvus

Status: Extinct

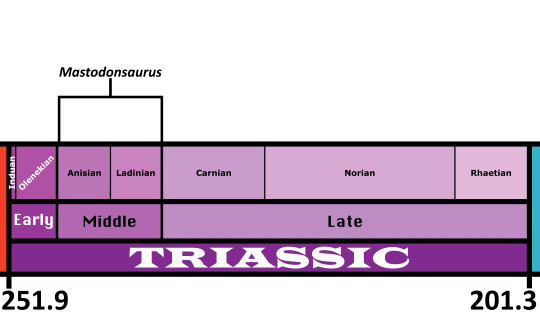

Time and Place: 247 to 237 million years ago, from the Anisian to the Ladinian of the Middle Triassic

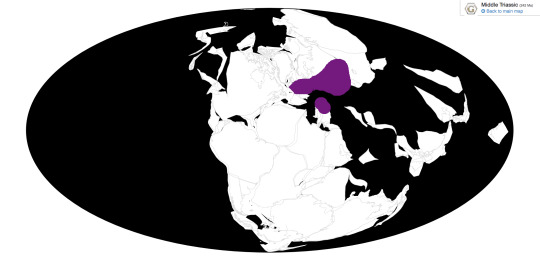

Mastodonsaurus is known mostly from Germany and Russia.

Physical Description: Mastodonsaurus was a very large temnospondyl, growing up to 6 meters (20 feet) long. It’s one of the largest “amphibians” (if you accept the term to mean non-amniote tetrapods) known from actually decent remains. This thing’s downright badass. Its head was large, wide and flattened, with the eyes positioned at the top about ⅔ of the way back. The head was roughly-textured, being covered in rugosities that suggest a tight covering of skin. The upper and lower jaws were filled with spikelike teeth, of which there were two rows in the upper jaw. Each tooth has a complex labyrinthine structure in cross section, leading to the colloquialism “labyrinthodont” for big temnospondyls like this. Two teeth in the front of the lower jaw had developed into large tusks, which were so large that there are holes on the top of the jaw for the tusks to go through when the mouth was closed. I repeat: IT HAD HOLES IN ITS SKULL BECAUSE ITS TEETH WERE SO BIG. That’s downright gnarly. The upper jaw also had enlarged fanglike teeth on the palate, but they weren’t that huge. Postcranially Mastodonsaurus was similar to other temnospondyls, with short, sprawling limbs and a powerful tail.

Diet: Mastodonsaurus’s diet likely consisted of any living or until-recently-living animal that happened to be in the water (including if it was pulled in).

Behavior: Mastodonsaurus likely lived similarly to modern crocodiles, lurking in waterways waiting for prey. In the water it may have done short chases after prey such as fish and other temnospondyls, but it probably ambushed tetrapod prey. Its limbs were quite small relative to the rest of its body, indicating that it likely spent most of, or even almost all of, its time in the water. It may have been able to attack animals on the banks of waterways, but that’s probably the most it did on a regular basis: grabbing prey on the shore of the water and dragging it back in to be eaten.

Ecosystem: Mastodonsaurus lived in environments with lots of freshwater. Some Mastodonsaurus-preserving environments also bear marine fossils, suggesting it may have also lived in coastal deltas or estuaries. M. jaegeri, M. cappalensis and M. giganteus lived in what is now west-central Europe. This area was evidently very wet, as evidenced by the variety of aquatic animals discovered there. These include fellow temnospondyl Gerrothorax, the nothosaurs Nothosaurus and Simosaurus, the early turtle Pappochelys, Tanystropheus, sharks, mollusks, and our old friends Ceratodus and Saurichthys. Some terrestrial animals also lived in this area, like cynodonts and the pseudosuchians Batrachotomus and Ctenosauriscus. Meanwhile, M. torvus lived in what is now Russia, alongside fellow temnospondyls Plagioscutum and Plagiorotus, the prolacertid Malutinisuchus, the rauisuchid Energosuchus, the erythrosuchid Chalishevia, and Elephantosaurus, a dicynodont with a horrible name.

Other: I try not to be an awesomebro, but this thing was pretty cool.

~ By Henry Thomas

Sources under the cut

Moser, M., Schoch, R. 2007. Revision of the type material and nomenclature of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (Jaeger) (Temnospondyli) from the Middle Triassic of Germany. Palaeontology 50(5): 1245-1266.

Owen, R. 1842. On the Teeth of Species of the Genus Labyrinthodon (Mastodonsaurus of Jaeger), common to the German Keuper formation and the Lower Sandstone of Warwick and Leamington. Transactions of the Geological Society of London 2(5). 503-513.

Schoch, R.R. 1999. Comparative osteology of Mastodonsaurus giganteus (JAEGER, 1828) from the Middle Triassic (Lettenkeuper: Longobardian) of Germany (Baden-Wurttemberg, Bayern, Thuringen). Stuttgarter Beitrage zur Naturkunde B 278: 1-175.

#mastodonsaurus#temnospondyl#labyrinthodont#triassic#triassic madness#triassic march madness#prehistoric life#paleontology

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Labyrinthodon from Outlines of Creation by Elisha Noyce, 1858

https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/48876/pg48876-images.html

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Labyrinthodon, Nothosaurus, Mastodonsaurus, and Dyoplax, 1877, by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

I never really knew what to do with the Australian Bunyip in my Mythika project... I really wanted to include the Bunyip as it is really famous and I already have too few creatures from Australia in my list. But whatever I thought up, I was was never satisfied with it, and even in the myth itself it has SO many forms that it can go anywhere, sometimes it looks like a hippopotamus, in other versions it is a giant starfish.

But then my old interest for Prehistoric Creatures was triggered again and I encountered an old favorite of mine called the Gorgonopsid (cool name), which I really wanted one way or another in Mythika, and those huge sabretooth’s are often aso mentioned with the Bunyip’s stories. There isn’t a creature in mythology, folklore or cryptid sightings that resembles the Gorgonopsid, so why not.

Now Mythika’s Bunyip pretty much looks like a more monstrous (yes it is possible) and aquatic version of this prehistoric mammalian-lizard horror.

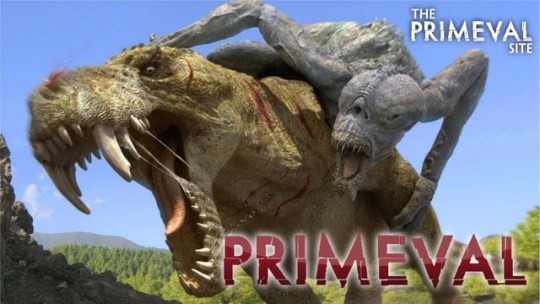

P.S: I loved Gorgonopsid (which I then called by it’s other name: Lycaenops) LONG before the (pretty bad) series Primeval used them, the only cool thing in Primeval was the model for the Gorgonopsid, the Arthropleura (giant Centipede) and the Giant Salamander horror (Labyrinthodon)

The first time I ever saw the Gorgonopsid was when I was five years old and I was reading/watching pictures through my fathers old Dinosaur books. Unlike the overused Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops which I never found that interesting, I instantly became an Gorgonopsid fan.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panorama showing animals of the Secondary, Tertiary, and Quaternary Eras, folding hand-colored engraving, from Isabelle Duncan, Pre-Adamite Man, 1860

https://www.lindahall.org/about/news/scientist-of-the-day/isabelle-duncan/

#megatherium#mammoth#irish elk#deinotherium#pterodactyl#megalosaurus#iguanodon#labyrinthodon#ichthyosaurus#hylaeosaurus#benjamin waterhouse hawkins#1860#isabelle duncan

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Long, Strange Tale of the Hand Beast Footprints

https://sciencespies.com/nature/the-long-strange-tale-of-the-hand-beast-footprints/

The Long, Strange Tale of the Hand Beast Footprints

In Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, the legendary sleuth Sherlock Holmes observes: “There is no branch of detective science which is so important and so much neglected as the art of tracing footsteps. Happily, I have laid great stress upon it, and much practice has made it second nature to me.”

Holmes is able to distinguish the separate tracks of two men from the many footmarks of the constables on the scene. He can calculate when the men arrived, and by the length of their stride, can determine their height. He also determines that one man is fashionably dressed “from the small and elegant impression left by his boots.”

Countless crime scene investigators have used footprints to apprehend culprits, but footprints are also a valuable resource for studying ancient animals. In many rock formations, tracks are the only remaining record that paleontologists can find of animals that lived millions of years ago.

We can identify the creatures who made fossil footprints if the imprints are well-preserved. The details in these will often reveal the configuration of the bones in the hands or feet and even show traces of skin on the palms and soles. From the length of the stride, researchers can also calculate the speed at which the animal moved.

Sometimes, however, the shape of the footprints can be misleading. Take for example, a set of footprints found in 1833, in a small town in Germany. The fossil footprints, discovered during a construction project, confounded the great naturalists of the day. And, therein lies a tale.

The peculiar foot prints of the hand beast showed hind feet imprints that looked like large human hands with prominent thumbs alongside much smaller front feet.

(Hans-Dieter Sues)

More

Friedrich Sickler, the high-school principal in the town of Hildburghausen, first discovered the fossils. He was building a garden house when he noticed strange imprints on the sandstone slabs that were used for this construction project. The sediment was part of what today is termed the Buntsandstein, meaning “colored sandstone,” which represents the early part of the Triassic Period in much of Europe—about 252 to 248 million years before the present.

Sickler offered rewards for more tracks to the workers in the sandstone quarry and soon a large surface covered with the footprints was exposed. The hind feet imprints looked like large human hands with prominent thumbs. The much smaller front feet left only imprints of the fingers. Unable to identify the maker of these tracks, Sickler published an “open letter” in 1834 describing his discovery to the famous German physician and naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.

Word of Sickler’s find quickly spread and many naturalists weighed in with interpretations of the track maker. Europe’s natural history museums rushed to acquire track-bearing slabs cut from the quarry’s sandstone surface. Researchers made learned guesses at what sort of creature could have left the tracks. The legendary explorer Alexander von Humboldt believed that they were made by a marsupial. Another naturalist insisted the prints were the tracks of a giant ape and still others offered up animals as varied as giant toads and bears. Finally, the German naturalist Johan Kaup named the unknown creature Chirotherium, which means simply “hand beast” in Greek.

A few years after Sickler’s discovery, Chirotherium tracks were found in Cheshire, England, and later also in France and Spain. Naturalists remained at a loss. The unusual footprints were turning up in other locations but without any known skeletal remains of backboned animals to help identify what could have left them.

Recently restored reconstructions for one contender, the giant toad-like Labyrinthodon, can still be found in Sydenham, London.

( Tom Page, Wikimedia Commons)

More

In the 1840s, two famous Victorian scientists, Sir Richard Owen and Sir Charles Lyell, developed theories about the animal responsible for the Chirotherium footprints.

From rocks in Warwickshire, Owen identified a few bones similar in age to those from Cheshire as belonging to large amphibian precursors. He named these animals Labyrinthodon because of the labyrinthine folding of the dentine in their teeth. Owen surmised that Labyrinthodon could have made the tracks of Chirotherium. A few years later, Owen began working with the British artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins to build the first life-sized reconstructions of prehistoric animals for the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. (The models, recently restored, are still on view in a park in Sydenham, London.) The two men envisaged Labyrinthodon as a giant toad-like creature that looked like it had escaped from the nightmarish paintings of Hieronymus Bosch.

Lyell, who is considered the father of modern geology, meanwhile, wondered how the Chirotherium would have ambulated because the “thumbs” of the tracks were pointed to the outside of the foot. Using the Owen-Hawkins model of Labyrinthodon, Lyell surmised that the animal must have walked with its feet crossed! Other researchers found Lyell’s reconstruction implausible, but they could do no better.

In 1855, Sir Charles Lyell took a stab at modeling how Chirotherium might have walked, surmising that because of the thumbs, the poor creature had to get around with its feet crossed.

(Hans-Dieter Sues)

More

Little changed until 1925. That’s when a German paleontologist named Wolfgang Soergel decided to review all available specimens of Chirotherium held in German collections.

Looking at the feet of many living reptiles, he realized that the “thumb” had been misidentified because previous researchers had been so heavily influenced by its similarity to a human thumb. It was, in fact, Soergel pointed out, the fifth toe sticking out from a five-toed hind foot. Measuring the trackways, Soergel, then, reconstructed the limb posture and proportions of the Chirotherium track-maker. In Soergel’s model, the creature would have had strong hind legs and short forelegs, both of which were held much more upright than in living reptiles. The hind feet left large impressions whereas the front feet barely touched the ground. Much like our fingers and toes, well-preserved footprints had distinct crease lines, which allowed Soergel to reconstruct the arrangement of bones in the digits.

But the question still remained: what animal left the Chirotherium footprints?

After an extensive search, Soergel noted that a two-foot-long reptile named Euparkeria roaming South Africa early in the Triassic also had a foot with its fifth toe sticking out to the side. Euparkeria is an ancient precursor of both crocodilians and dinosaurs. Although the reptile that made the Chirotherium tracks was quite a bit larger than little Euparkeria, Soergel inferred that the Chirotherium track-maker was probably related to the South African reptile.

Enter the famous German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene, who in the late 1920s was conducting fieldwork in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul. A German doctor had sent him crates of unusual bones found there and dating from the Triassic. While in Brazil, Huene became acquainted with a local resident named Vincentino Presto, who knew of a promising deposit of such bones. In 1942, Huene recovered the remains of a large predatory reptile that he christened in honor of Presto, Prestosuchus. This creature attained a length of at least 20 feet and is distantly related to crocodilians.

Batrachotomus is a slightly younger relative of Ticinosuchus. It has the same foot structure with a spread-out fifth toe that created the “thumb” imprint of Chirotherium.

( Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, Wikimedia Commons)

More

When Huene reassembled its foot bones he noted a striking resemblance to the foot skeleton that Soergel had reconstructed for the maker of Chirotherium. Huene had come across a major clue about the track-maker. The Chirotherium tracks were probably left by a reptile related to Prestosuchus.

However, at that time, nothing like Prestosuchus had ever been recognized in Europe and other scientists remained unconvinced by Huene’s interpretation.

It was decades later, in 1965 that another major clue emerged, when the French paleontologist Bernard Krebs described the nearly complete skeleton of a ten-foot-long crocodile relative found in Triassic rocks of the Ticino region in Switzerland. Krebs named his creature Ticinosuchus, Latin for “crocodile from the Ticino,” noting that its feet were near-perfect matches to the Chirotherium footprints and its body form closely matched Soergel’s reconstruction. Furthermore, the rocks containing the remains of Ticinosuchus were the same geological age as those with Chirotherium. It was a promising connection.

Meanwhile in 2004, the town of Hildburghausen, looking for its rightful place in history, dedicated a monument to the decades-long long search for the track-maker. It featured the reconstructed original sandstone surface with the Chirotherium tracks but the bronze reconstruction of a crocodile-like reptile was still not quite accurate.

After decades, researchers finally found the culprit. It was Ctenosauriscus, (reconstruction above) which had very tall spines on its backbone that probably supported a sail.

(Hans-Dieter Sues)

More

There was one last chapter in this long saga. It involved another reptile—Ctenosauriscus, which is Greek for “comb reptile,” and was from the Buntsandstein of Germany. Very tall spines on its backbone probably supported a sail along the back of the animal. The 2005 publication of a skeleton of the closely related Arizonasaurus in the Moenkopi Formation of Arizona established that the German Ctenosauriscus belonged to the same group of crocodile-like reptiles as Prestosuchus and Ticinosuchus. The Moenkopi Formation is nearly the same geological age as the German Buntsandstein and has also yielded many footprints of Chirotherium.

Now at long last, the Holmesian quest for the maker of the Chirotherium footprints has come to an end. It was crocodile precursors like Arizonasaurus, Ctenosauriscus, Prestosuchus and Ticinosuchus, that had left these prints.

Tracks that resemble those of Chirotherium have now been found on most continents. Some possibly represent precursors of dinosaurs. Many other kinds of fossil footprints have been found, hinting at the existence of as-yet-unknown animals awaiting future discovery. As Sherlock Holmes would have said: “The game is afoot.”

Join us on Facebook or Twitter for a regular update.

#Nature

0 notes

Photo

“Last night she dreamed she was wandering through a labyrinth of teeth.” —Cai Emmons, His Mother’s Son (2002)

The pictured section of a labyrinthodon tooth appears in Cosmopolitan Magazine, 1892.

82 notes

·

View notes