#manifoldly

Text

Big cum from masterbation

Me la como entera la verga de mi tio

Busty Amateur Milf Fucked BVR

Dedeando a mi amiga bien rico

Gay sexy latin men naked xxx but he opened up hastily and told me all

Teen blonde rides dildo in bathroom This is our most extraordinary

I Trapped His Cock And Balls In My Tan Nylon Stocking Feet Footjob Creative Peds

Toe Sucking And Piss Play For Hot Lesbians

Gay sex young video free and sexy straight high school jocks wanking

Sexy Skinny Teen Creampied

#mistranscribing#housings#rayonnance#peanut's#Gogh#manifoldly#pharyngitis#faceclaims#Erythronium#serened#peised#nonresponsibilities#muscleworship#slinging#corymbiform#macrophotograph#rabblement#Fawkes#DGA#hypoderms

1 note

·

View note

Text

Verse 10.33 - Vibhuti Yoga

अक्षराणामकारोऽस्मि द्वन्द्वः सामासिकस्य च ।

अहमेवाक्षयः कालो धाताहं विश्वतोमुखः ॥ १०.३३ ॥

Among letters I am the letter 'A', and among compounds I am the dual. I am the endless time, and I am the creator Brahma, whose faces are everywhere.

- The letter 'A' is the first and most important letter in the Sanskrit alphabet, as it is the source of all other letters and sounds. It also represents the supreme self (ātmā), which is the origin of all beings and the essence of everything. By identifying himself with the letter 'A', the Lord reveals his supreme position as the source of all creation and the inner self of all.

- The dual compound (dvandva) is a grammatical form in Sanskrit that combines two words of equal importance, such as Rama-Lakshmana or Radha-Krishna. It signifies the unity and harmony of two entities that are distinct but inseparable. By identifying himself with the dual compound, Lord Krishna reveals his ability to manifest himself in various forms and relationships, such as the lover and the beloved, the master and the servant, or the friend and the companion.

- The endless time (akṣhaya kāla) is the eternal cycle of creation, maintenance, and destruction that governs the material universe. It is also the measure of change and transformation that affects all living beings. By identifying himself with the endless time, Lord Krishna reveals his power to control the destiny of all creatures and to transcend the limitations of time and space.

- The creator Brahma (dhātā viśhvatomukha) is the first-born being in the universe, who emerged from the lotus that sprouted from Lord Vishnu's navel. He is endowed with four faces that look in all directions, symbolizing his omniscience and creativity. By identifying himself with Brahma, Lord Krishna reveals his role as the originator and regulator of the cosmic order and the dispenser of the fruits of actions.

Some similar verses from Vedic texts that express the same idea of identifying oneself with various aspects of reality are:

- Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10:

अहमेव वेद्यो नान्यदतोऽस्ति द्रष्टा ।

अहं मनुरहं सूर्यश्चेति भेदान् प्रतिपद्यमानान् ॥

I alone am to be known, there is no other seer than me. I am Manu, I am the sun, etc., thus distinguishing myself in various ways.

- Chandogya Upanishad 3.14.1:

सर्वं ह्येतद् ब्रह्मायमात्मा ब्रह्म सोऽयमात्मा चतुष्पात् ।

All this is Brahman; this Self is Brahman; this Self has four quarters.

- Aitareya Upanishad 1.1.1:

प्रजापतिर्वै इदमेक आसीत् ।

तस्यैकमेव मुखं बहुधा विभक्तं प्रतिपद्यते ॥

Prajapati (the lord of creatures) alone was this (universe) in the beginning. His one face alone becomes manifoldly manifested.

These verses show how the supreme self or Brahman assumes various names and forms to create and sustain the universe, while remaining one and indivisible. They also show how one can realize one's identity with Brahman by knowing oneself as the source and essence of all.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Oneness in parts

Manifoldly mirrored,me in many partsor canvas oneness-art that drills belowmy complacent skininto my manic mindkaleidoscoped in fourpoint one dimensions,but when I squeezemy eyes, my focusinto two unfolds, andI am one, assembledfrom all divergentpieces lost before.’

“Portrait of Eivind Eckbo” by Thorvald Hellesen

Today Lillian hosts dVerse poetics with a prompt with pictures by Thorvald…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Amid the rising Southern border crisis in the United States, the need to regulate the immigrants has also increased manifoldly.

As Democrats passed their immigration bill, named the American Dream and Promise Act of 2021, from the House, the Republicans have also come up with a parallel bill proposing different policy measures than those of the Democrats.

The stark difference remains the border security, as Biden has already announced that the Mexico wall would not be built further during his administration.

On the other hand, Republicans are pushing hard to use the latest technology on the borders to safeguard national interests.

Republicans have even made border security with physical barriers a prerequisite of implementing other measures, which seems a political move from the men in red.

What are the stark differences between both the bills and which bill is likely to be passed from Congress? Let’s see.

Covering Up Southern Border: A Bone of Contention Between Both Parties in Immigration Bill

Fencing the US-Mexico border remains the bone of contention between the Republican congressmen and their Democratic counterparts.

On the one hand, Republicans have explicitly mentioned the need to fence the Mexico border with physical barriers and the inclusion of the latest technology in the process. On the other hand, Democrats have no mention of fencing the border in their passed legislation.

This is not a surprising approach from the Democrats as President Joe Biden was vocal about stopping border funding after coming to power. He once again reiterated his ambition not to fence the US-Mexico border any further.

So, the Democrats’ ambitions not to approve funding for the Mexico wall seems an explicit approach, and they are not going to compromise on this.

Republicans U-Turn on Dreamers

Republicans have also drifted away from their hardline approach on the Dreamers, who were subjected to discrimination by former President Donald Trump.

As Trump wrapped-up the protection for Dreamers introduced by Barack Obama, the Supreme Court refrained Trump from doing so.

This time, Republicans seem to change their approach on Dreamers as they are demanding an immediate legal status for Dreamers. Similarly, in the Democrats’ introduced immigration bill, Democrats are also seeking to give these children legal status for ten years.

Owing to the similarity of approach from both the parties, this provision is likely to be unchanged in the final bill.

Prioritizing Border Security: Republicans Plan to Play Politics on Immigrants’ Rights

The contentious point in the Republican proposed Dignity Plan is the security of the border before anything else. Republicans are trying to fence the border as a priority, and according to them, no measure should be taken before completing border security.

While Republicans seem to agree with many of the Democrats’ provisions, including the protection for Dreamers and the undocumented agriculture workers, apparently, it seems that Republicans want to capitalize on the Democrats’ approach of not fencing the border.

It seems a tricky approach, as opposing the bill directly would have given the notion of ignorance toward immigrants.

So, instead of adapting not such popular measures of completely rejecting the bill, they have introduced unacceptable provisions in it.

By introducing the demand of using the latest possible technology on the Mexican border with complete fencing, they know Democrats will not accept their demands, which will delay the legislation.

There is no doubt that Republicans’ plan seems to be ambitious with workable solutions, but their approach to making border-security a prerequisite makes the plan worthless.

As a matter of fact, if Biden agrees to Republicans’ demand of fencing the Mexico border with physical barriers, he would end up giving up on his campaign promises.

With this, there won’t be much difference between both the parti

es then.

Final Thoughts

The Democrats proposed immigration bill will also increase the annual Green card number to almost 1.5 million from its current value of 1.1 million.

Not only this, but the advanced degree holders and the first preference workers would also be incorporated into the plan on a priority basis.

As the bill moves to the Senate, it is unlikely to be passed from the upper house in its entirety due to a 50-50 divide in Senate. So, at the end of the day, both parties have to make a compromise to find a workable solution.

However, considering the extreme approach of border security by both parties, it is unlikely that any party will drift away from their stance, making the passage of the bill even more difficult.

Video Summary:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3qixwZ5yeU

0 notes

Text

All about Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI)- Mr Harish Jagtani

Lower Respiratory Infection or Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI) affects the lower airways of the lungs. This kind of infection is mostly caused by viruses like the COVID-19 but in certain cases, bacteria and other organisms are also capable of causing LRTI. According to the Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research (JCDR), LRTI affects 20-40% of people in developing countries and 3-4% in developed countries.

High-Risk Groups

Lower Respiratory Tract Infection can affect adults, young children and even infants. However, adults above 50 years of age are more likely to be affected by this condition (experts suggest that the maximum number of LRTI patients are aged between 31-40 or 51-60 years). However, the recovery rate of a person above 50 years of age is much lesser than those below due to weaker immunity.

High-Risk Agents

Generally, smoking, use of tobacco, and alcohol consumption increase the risk of getting Lower Respiratory Infection or Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI).

Diagnosis

LRTIs are diagnosed with the help of chest X-rays, pulse oximeters for blood saturation, mucus or blood samples, and even CT scan.

Causes & Symptoms

In infants and young children, common symptoms of LRTI are generally mild and include flu or influenza, pneumonia, coughing and fever. However, in adults, symptoms could be severe, like chest pain, breathlessness or shortness of breath, wheezing, irregular pattern of breaths, decreased energy, loss of appetite, fever, severe pneumonia, etc.

Complicated and Uncomplicated LRTI

It is important to note that the majority of infections of the lower respiratory tract are usually uncomplicated and do not require anything more than medications. However, in certain cases where severity exists, LTRI can result in-

· Lung abscesses

· Respiratory failure

· Sepsis

· Respiratory arrest

· Congestive heart failure

Complicated Lower Respiratory Tract Infection (LRTI) may have long term effects. However, most people make full recovery with uncomplicated infections of the respiratory tract.

Among young adults, the recovery time is generally 1 week. For older adults, it may take several weeks to fully recover.

Treatment

Antibiotics are less effective in case the respiratory infection is caused by viruses. LRTI generally resolves entirely on its own with prescribed medications and proper care. Oxygen supplements are given to those suffering from acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infection, with the help of nasal prongs, catheter, etc.

Prevention

To prevent getting an LRTI, one must follow certain hygiene and health practices. They include:-

· Frequently washing hands

· Distancing from those facing respiratory complications

· Disinfecting surfaces regularly

· Getting vaccinated

The bottom line

While most Lower Respiratory Tract Infections or LRTI get better with over-the-counter medications and plenty of rest, the severe ones may require hospitalisation- IV fluids, antibiotics, and breathing support. HJ hospital doctors and staff are experts trained and experienced in monitoring and nursing patients with Lower Respiratory Tract Infections. The hospital is equipped with the latest technology machines and infrastructure that could ease the process of recovery manifoldly.

Mr Harish Jagtani

Source: https://www.hjhospitals.org/en/blog/All-about-Lower-Respiratory-Tract-Infection-LRTI

0 notes

Text

What is the meaning of the horrific and horrible very terrible disasters and immense turmoil, the unmeasurable troubles, happening one after another. It is the very last days unfolding before our own very eyes! Now, more than ever is not the time to be thinking negatively about God. Now is the very last chance to offer ourselves as a living sacrifice to our Glorious Heavenly Creator, who has been so graciously and manifoldly extending the greatest work of propagation, on the face of the earth through the true Church of Christ, In these last days. Now even more God has every reason for His anger to Kindle, because not only when Christ was here was he so bitterly rejected by the Pharisees hypocrites kings and rulers but now in these last days people have all the more only become lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God not realizing the true reason for the advances of technology and communication for the greater purpose in completing the work of the first century Church of Christ, that began through the preaching of the apostles, before it fell into apostasy by the devil introducing false teachings into Christianity. The true Church of Christ has reemerged in these last days at the time for told by Christ at the beginning of world wars. Now, in just a little over 100 years, the Iglesia Ni Cristo, Church of Christ has began in the Far East already reaching the Far West, spreading to 159 countries to include 148 nationalities within its membership by the calling of God. The finishing touches are being placed on the work of salvation and the return of Christ is very eminent. The meaning of one disaster after another is the very last wake up call of God, letting all of mankind know the anger of God for ignoring our true purpose in the great gracious gift of salvation through his precious son is about to end with everlasting punishment. INCmedia.org

0 notes

Link

In case you guys didn’t know, I’m a librarian with the Memphis Public Libraries, a job I find manifoldly interesting. But tomorrow, July 28th 2020, at 2pm Central I get the chance to lead a virtual program called Creative Writing 101!

It’s open to all. You don’t have to be a library card holder to join. It uses Microsoft Teams, the chat/audio is muted for safety, but you’ll get to see my face and hear my voice... and maybe you’ll find something worthwhile in it.

I plan to share some tricks, tips, and pointers for those of you who are interested in writing fiction stories.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"The likeness of (the ones) who expend their riches in the way of Allah is as the likeness of a grain that grows seven ears, in every ear a hundred grains. And Allah gives manifoldly to whomever He decides." (Quran 2:261) 🌾 #Islam #IslamicGems #charity #wealth #donation #multiplicatiom #good #deeds https://www.instagram.com/p/B8lKXk9lp5y/?igshid=1cp5o9450tajw

1 note

·

View note

Text

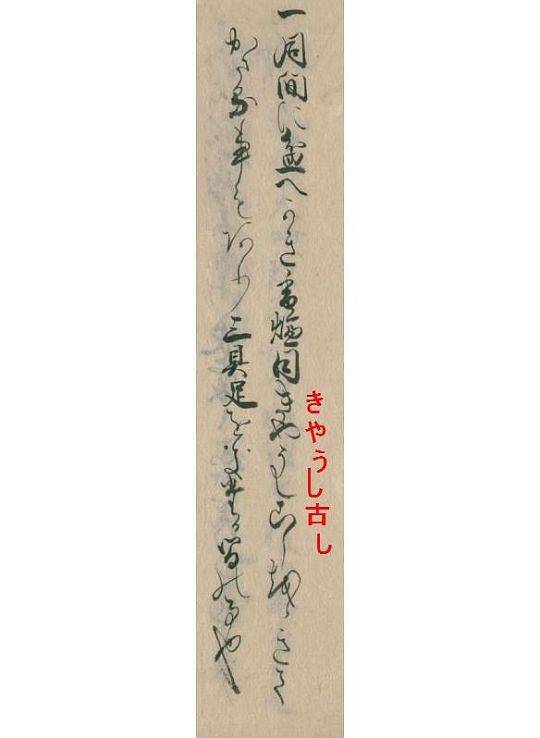

Nampō Roku, Book 4 (4): the Display of the Mitsu-gusoku [三具足] on the Oshi-ita [押板].

4) With respect to the mitsu-gusoku [三具足]¹ on the oshi-ita [押板], the orthodox way of displaying these things² encompasses multiple layers of ku-den [口傳]³.

_________________________

¹Mitsu-gusoku [三具足].

The set of three, usually bronze, implements that are traditionally arranged before the Buddha image(s) on a family altar*.

As shown above, these consist of a flower vase (left), a censer† (middle), and a candlestick (right). This particular set was made in the 20th century.

___________

*In a temple setting, the number is usually increased to five -- and so referred to as go-gusoku [五具足] -- by adding one more flower-vase and one more candlestick.

†The shape of the censer is determined by the type of incense that will be burned. In modern times, stick incense (which are said to have first appeared during the Ming dynasty) is commonly used, so the censer has a wide mouth (in order to catch the ash as it falls from the burning stick: such censers generally lack a lid); an example of this type of incense burner is shown on the left, below.

Burning incense by placing a piece of fragrant wood on top of a charcoal tadon [炭團] requires a more cup-like shape (middle), and which is only covered when not in use (to keep the ash clean and dry). Crushed incense (which resembles sawdust made from incense wood), which is formed into a cone by pressing a large pinch of incense against the bottom of the vessel, is burned in more constricted censers, usually provided with a slotted lid (the control of the atmosphere within the censer causes the incense to smolder away more slowly), and an example of this kind of censer is shown on the right..

²Hon-shiki no kazari [本式のかざり].

Hon-shiki [本式] means orthodox, formal, proper. The traditional way that these things have been arranged since ancient times.

³Jūjū ku-den ōshi [重〻口傳多し].

Jūjū [重々] means repeatedly, manifoldly, again and again -- in other words “the entire body” of associated ku-den, layer upon layer.

Ku-den [口傳] means orally transmitted [teachings]. These things were never supposed to be written down, but imparted directly by the teacher to his disciple (hence the name).

In this case, however, we must remember that Book Four of the Nampō Roku is essentially a collection of notes that Jōō wrote down while listening to discussions about these things during the Shino family’s kō-kai. The word ku-den, then, was probably interpolated by Jōō (or, possibly by his interlocutors -- it being unclear how deeply apprised these people may have been regarding the innermost teachings) -- because of a lack of a complete understanding of these matters on his part (these notes seem to have been made rather early in Jōō's career, probably many years before he came to be recognized as a meijin [名人]). Information not revealed (for whatever reason) was deemed “secret” -- and the usual way to describe secret information is to call it a ku-den.

The actual, historical, reference seems to be to the relevant body of teachings (such as they are) that were included in Sōami's O-kazari Ki -- which I will attempt to translate (in full) below (along with the brief comments from Shibayama Fugen’s and Tanaka Senshō’s commentaries).

Ōshi [多し] means many; a large number -- though this may have been an exaggeration introduced into the narrative purely for Jōō’s benefit (for whatever reason, the people of the orthodox lineage seem to have been extremely careful to avoid revealing their secrets to this man).

==============================================

◎ The following are the references, which may be associated with the mitsu-gusoku, that are found in the O-kazari Ki. The entry numbers are according to the Gunsho Ruijū [群書類従] version of the O-kazari Ki (which agrees with the text of the manuscript copy that was preserved by the Imai family, from which the several illustrations are taken), as published in the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu [茶道古典全集]. (The Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu also includes a second version of this document, which corresponds to the early Edo period block-printed edition that was mentioned previously, at the bottom of the post entitled An Introduction to Book 4 of the Nampō Roku: Shoin [書院], Part 2 -- Sōami’s O-kazari Ki [御飾記], and the O-kazari Sho [御飾書]: https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/189154183823/an-introduction-to-book-4-of-the-namp%C5%8D-roku.)

The examples, by the way, provide a fairly representative view of the kind of information that the O-kazari Ki contains. I have quoted the original Japanese text first, and then translated it, while keeping my own comments (which are contained in the footnotes) to a minimum.

43) Mitsu-gusoku no kōgō ni ha, kō wo go-kire bakari iru-beshi. Kaki-kōro* no kō-bako† ni ha mei-kō wo tsutsumi nagara iru-beshi, shiki sadamarazu [三具足之香合には、香を五きれはかり入へし、かき香爐の香はこには名香を包なから可入、敷さたまらす].

The kōgō [placed] with the mitsu-gosoku should contain [only] five pieces‡ of incense; in the kōgō [arranged] with the kiki-kōro**, the mei-kō should be enclosed in a wrapper††, though whether [a piece of paper should also be placed] underneath [the wrapper] has not been fixed‡‡.

__________

*Kaki-kōro [かき香爐]. According to the other versions of the O-kazari Ki and O-kazari Sho, this word should be kiki-kōro [聞き香爐], a censer that is held in the hand while appreciating very special incense wood.

Perhaps this was a miscopying for kika-koro [きか香爐 = 聞 か香爐] -- though it appears consistently throughout this version of the O-kazari Ki, with the apparent meaning of “a hand-held censer used for appreciating incense.”

†Kō-bako [香はこ]. The kōgō [香合]. The kanji for kōgō was pronounced kō-bako during this period -- though I have generally used “kōgō” in the transliterations whenever the pronunciation was not spelled out (as here), to help modern readers avoid confusion.

‡Go-kire [五切れ] means five “slices” -- the original piece of incense wood was sliced into thin, roughly square, pieces, using a special chisel. The result was similar to the way byakudan [白檀] and jin-kō [沈香] are sold nowadays.

**Kiki-kōro [聞香爐], a small, ceramic censer intended to be held in the hands while sniffing the incense being burned in it.

††Mei-kō wo tsutsumi nagara iru-beshi [名香を包なから可入]. Mei-kō [名香] refers to high-quality incense wood (usually kyara [伽羅], which is jin-kō with an extremely high resin content). A kō-zutsumi [香包] is a sort of envelope, traditionally made either of heavy paper, or of paper coated with gold foil on one side and a piece of donsu cloth on the other. As with the chaire, the gold-foil prevented the loss of aromatics while also protected the incense from external smells. Generally two pieces of kyara were placed in each kō-zutsumi, as insurance against the accidental dropping of one of them. (Enclosing more than two pieces was discouraged, so as to prevent the guests from asking for them.)

‡‡The piece of paper was placed between the kō-tsutsumi and the bottom of the kōgō, to prevent the transfer of any aromatics that had infiltrated into the lacquer to the incense. If the mei-kō was in a kō-zutsumi made of gilded paper, then the danger of infiltration was low; however, if it were simply in an envelope made of heavy paper, prudence might dictate that this be, in turn, placed on top of a piece of paper, as added protection.

46) Mitsu-gusoku ni ha, ko-dō ni te, kō-saji no dai bakari chawan-no-mono ni te mo kurushikarazu [三具足は胡銅にて香匙之臺ばかり茶碗の物にてもくるしからず].

When the mitsu-gusoku are made of ko-dō [胡銅]*, only the stand for the kō-saji [and kyōji] should be [placed out together with them]†; however, there is no problem if a chawan [is also included in the arrangement]‡.

__________

*Ko-dō [胡銅] is a variety of bronze that has turned a deep black with age. This type of bronze was produced in both China and in Korea. The kanji ko [胡] means “barbarian,” and so may have referred to an early type of bronze: possibly the earliest varieties of the metal (dating from the bronze age) were imported from the regions to the west of China.

†Kō-saji no dai [香匙之臺] refers to a small, vase-like container, resembling a miniature shaku-tate, in which the kō-saji (a spoon used to handle the incense) and kyōji (a pair of ebony or ivory chopsticks that were also used to handle the incense) were stood. In the present day, a bundle of stick incense is often stood upright in the same sort of vessel, to keep the incense ready for when it is needed (though this practice appears to be a corruption, resulting from ignorance) -- thus the kō-saji no dai is often still present along with the mitsu-gusoku, even though its original purpose has been forgotten.

According to modern usage, the kō-saji was used to transfer the pieces of incense from the jin-bako [沈箱] (a compartmented vessel in which the pieces of incense were collected from the chopping block) into the kōgō, while the kyōji were used to place one piece of incense in the kōro. (The ash was sometimes shaped with a different utensil -- one which resembles a folded fan, and is termed a hai-oshi [灰押]: the hai-oshi should never be identified with the kō-saji, though people connected only with chanoyu are apparently inclined to do so on account of its similarity to the hai-saji [灰匙].)

‡Chawan-no-mono [茶碗の物] is used in the O-kazari Ki to refer to a kenzan-temmoku [建盞天目] resting on a temmoku-dai. This was the chawan used to serve tea to the most exalted guest.

51) Hito no mae [h]e dasu toki, hana-no-moto wo mukawasu-beshi [人之前へ出す時、花の本をむかはすへし].

When placing something* out in front of people, the root of the flower† should be toward them‡.

__________

*In the other versions of the O-kazari Ki and O-kazari Sho, this entry refers explicitly to the kōgō.

†Hana-no-moto [花の本] means “the root (end)” of the flower. In other words, when an object features a picture of a flower and its leaves, the piece should be oriented so that the leaves (and butt-end of the stem) are in the front, with the flowers slightly toward the rear.

‡The two sketches of kōgō show the way the pictures of plants should be oriented.

54) Hito ni dasu-toki ha, ashi hitotsu hito mae [h]e muku-beshi [人に出す時は、足一人のまへゝむくへし].

When [a kōro*] is brought out for people [to inspect on the oshi-ita, or on the chigai-dana], one foot should face toward the front of the person.

__________

*In the other versions, this entry actually begins with the word kōro [香爐]. Even though it has not been included here, the sketch eliminates any ambiguity caused by its absence (since it shows a picture of a kōro).

57) E ippuku kakete, san-gusoku oki koto kurushikarazu-sōrō, san-puku ittsui kakete, mitsu-gusoku nashi ha ryaku-gi nari [繪一幅懸て、三具足置事不苦候、三幅一對かけて、三具足無は略儀なり].

While there is no problem* with placing the mitsu-gusoku [in front of] a single scroll, in the case where three scrolls are displayed at the same time, the absence of the mitsu-gusoku is an informality†.

__________

*Kurushikarazu [不苦 = 苦しからず] means there is nothing wrong with doing something, literally "it is not a hardship to do (such and such)."

In other words, the host could place the mitsu-gusoku in front of a single scroll if he wants to do so. But there is certainly no rule stating that he must do this -- unlike in the case of a triptych (where the mitsu-gusoku should be arranged in front).

†Ryaku-gi nari [何も 略儀 也]. Ryaku-gi [略儀] means informality -- in the sense of taking a liberty, doing something irregular, or contrary to strict propriety. In other words, the mitsu-gusoku should be displayed in front of a triptych. Doing anything else, while not exactly wrong, deviates from the correct form.

62) Mitsu-gusoku ha tada mitsu-gusoku to iu, betsu ni mei nashi [三具足はたゝ三具足と云、別に名なし].

The mitsu-gusoku are simply called “mitsu-gusoku.” There is no other name.

71) Chū-ō-joku ha, mitsu-gusoku no mae ni oku nari [中央卓は、三具足のまへにをく也].

The chū-ō-joku is placed in front of the mitsu-gusoku.

81) Onaji ma ni bon [h]e kaki-kōro, onaji kōji koji wo okite kazaru-koto mo ari, mitsu-gusoku oki-taru aida no koto nari [同間に盆へ聞き香炉、同きやうしこしをゝきてかさる事もあり、三具足をきたる間の事也].

In the same room*, a tray, on which are a kaki-kōro, [a pair of] kyōji† and [a pair of] koji‡, is displayed. This is similar to the placement of the mitsu-gusoku [on the oshi-ita].

__________

*This follows on from entry 80, which describes a (wooden) pillow being arranged in a toko in a bed-chamber (the toko is used as a bed), “according to the (size of the) body (of the person who will sleep there);” or else something like a kara-bako [唐箱] (a “Chinese-box,” perhaps for night-clothes or bedding) could be placed there.

†Kyōji [きやうし = 香筋] are chopsticks made of ebony or ivory, used to handle the pieces of incense wood.

‡Koji [こし = 火筋] are chopsticks made of metal (silver and bronze were the most common), that are used to lift the tadon [炭團] (a small, cylindrical, briquette formed from crushed, high-quality charcoal, that is used to heat the kōro) into the kōro. Sometimes it is also used to shape the ash into a cone around the burning tadon.

While the original text (shown above) clearly has kiyaushi koshi [きやうし古し -- ko 古 is a hentai-gana for the sound ko こ], which would be read kyōji koji, these names seem somewhat out of place in this treatise, since I have not seen them used elsewhere in Sōami's writings (when he writes about the implements used to prepare the censer and transfer the incense, he usually speaks of the kō-saji no dai [香匙の臺], while the sketches include representations of both a kō-saji, and a pair of kyōji, ebony chopsticks used to pick up the pieces of incense wood, standing in the kō-saji no dai)*. The use of these words seems to be closer to the terminology employed by the specialist practitioners of kōdō [香道].

Changes such as this may be the result of editorial interpolations made when Sōami’s text (which has not survived) was hand-copied during the mid-sixteenth century†.

___________

*The editor of the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu edition of the O-kazari Ki / O-kazari Sho attempts to rectify things by seemingly changing the pronunciation of kō-saji [香匙] to kō-bashi [かうばし = こうばし], meaning “incense chopsticks.” But this solution does not really satisfy, since it then appears to ignore the “incense spoon” that kō-saji actually means, and which is clearly represented in the sketches.

Furthermore, “kō-bashi” [香箸] (as a name for what practitioners of kōdō refer to as the kyōji [香筋, or 香箸]) is actually the pronunciation preferred by practitioners of chanoyu (rather than incense) -- the Sadō Ko-ten Zen-shu’s intended audience -- leading to further doubts about the authenticity of this interpretation.

†The surviving period copies -- such as the one that was preserved in the Imai family -- were made for personal reference (and it is likely that they were all based on a single hand-made copy, rather than the original, since they all seem to agree in these kinds of anachronisms), rather than for the purpose of accurately preserving the original, historical text written by Sōami.

This differs from copies made of Rikyū’s densho, for example, where the intention was clearly to make a facsimile of the original (even insofar as imitating Rikyū’s handwriting).

○ In addition to the above entries, one is supposed to understand the correct arrangement of the mitsu-gusoku (if not the yin-yang reasoning behind the placement of the flower-vase and candlestick) from the following sketch*:

The sketch that is found later in Book Four of the Nampō Roku is similarly informative:

[The writing reads (from right to left): oshi-ita (押板); tori hidari migi ari (鳥左右アリ)†; mitsu-gusoku ・ ku-den ōshi (三具足・口傳多)‡.]

While some of the above entries are, indeed, the kinds of things typically transmitted as “ku-den,” their actual number is not especially large. So, unless large portions of the O-kazari Ki have been lost (which seems unlikely), it is possible that Jōō’s interlocutors exaggerated the number of ku-den in the hopes of mystifying and frustrating their auditor**.

___________

*I have digitally altered this sketch, to remove the scrolls that were hanging in the background, as well as the two stands with large flower-vases that were placed on the left and right sides of the oshi-ita -- since none of these things have any relevance to the way that the objects on the oshi-ita are arranged.

†Tori hidari migi ari [鳥左右アリ]. These candlesticks were originally made in pairs, with one facing right, and the other facing left. In this instance, the one that faces toward the left is the one that should be used.

In the original examples of this type of candlestick, the bird is not straight upright, but inclines in the direction toward which it faces, as can be seen more clearly in the sketch from Book Four of the Nampō Roku. The purpose of this was to throw the candle’s light in that direction, while minimizing any impact from the shadow.

‡Mitsu-gusoku ・ ku-den ōshi [三具足・口傳多]. As in the statement that forms the text of this entry, ku-den ō-shi [口傳多] means “there are many ku-den.”

**What little we know of Jōō‘s interactions with Kitamuki Dōchin (and these are found only in memoranda left by tea people, who would be inclined to represent Jōō’s interactions in the most favorable light) -- that he was always asking questions of Dōchin when the two were discussing chanoyu -- suggests that Jōō was inclined to pester the cognoscenti with questions about the secret details of gokushin-no-chanoyu, perhaps because such men were not inclined to be especially forthcoming (since they would have regarded Jōō as a potential competitor, rather than a disciple, if he were casually initiated into the deeper secrets). It is thus at least possible that some of these people were inclined to frustrate his accumulation of the facts through dissimulation and obfuscation.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

In addition to the things mentioned above (none of which is found in any of the commentaries on the Nampō Roku), the scholarly commentators have limited their own input to a surprising degree:

◎ Shibayama Fugen says only that the table on which the mitsu-gusoku will be displayed should be covered with a piece of kinran or donsu*; though, again, this is really not the kind of thing that was generally reserved for oral transmission from teacher to student -- and is also clear from the sketch that is included in the Nampō Roku, in which an elaborate uchi-shiki is depicted draping the oshi-ita†.

◎ Tanaka Senshō, rather curiously‡, uses most of his commentary to discuss the language of this final statement (jūjū ku-den ōshi [重〻口傳多し]) -- specifically noting that jūjū [重〻] is equivalent to the modern-day expression iro-iro [色々], meaning “various (things).”

And while he muses that there must be many relevant teachings that would qualify as ku-den (he mentions the material quoted by Shibayama Fugen, albeit at greater length than is strictly necessary, since anyone can gather as much during a brief visit to a shop specializing in family altars), he declines to introduce any of them in his commentary.

___________

*The way a Buddhist altar is draped with an uchi-shiki [打敷], altar-cloth. Shibayama bases his comments on one of the secret books that accompany the Nampō Roku (though this material -- contained in two volumes -- was not compiled until the decades that followed Tachibana Jitsuzan’s presentation of the Nampō Roku to the Enkaku-ji).

†Curiously, though, one is not seen in the corresponding sketch that was included in the O-kazari Ki) -- not even in the later version of this work, entitled the Higashiyama-dono O-kazari Sho, which is roughly contemporaneous with the Enkaku-ji version of the Nampō Roku.

‡The impression one gets it that, since the statement he is discussing indicates that there are a large number of ku-den associated with the display of the mitsu-gusoku on the oshi-ita, he does not want to leave his commentary page blank. Yet, in fact, aside from repeating the same point as Shibayama Fugen, regarding the spreading of an uchi-shiki on the oshi-ita under the mitsu-gusoku, Tanaka really says nothing at all about any secret teachings connected with the display of the mitsu-gusoku -- or anything else, for that matter.

1 note

·

View note

Text

NoViolet Bulawayo Allegorizes the Aftermath of Robert Mugabe

NoViolet Bulawayo Allegorizes the Aftermath of Robert Mugabe

GLORY By NoViolet Bulawayo

Early on in NoViolet Bulawayo’s manifoldly clever new novel, “Glory,” she completely removes the vocabulary of “people” from the story and the language of its characters, who are all animals. The book is set in Jidada, a fictional African country that can be understood as a sort of fantasia of Zimbabwe in the period between the 2017 military overthrow of its president,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

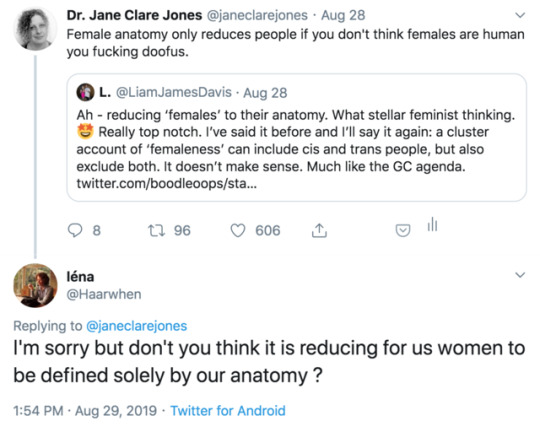

Photo

The Radical Notion That Women Are People — Jane Clare Jones So, after a summer recess of trying to forget that the world is manifoldly going to hell in a handcart, this week’s exciting ‘Back to Twitter’ experience has involved a good deal of feminists being berated for ‘reducing women to their genitals/biology/anatomy/whatever.’ This woke-approved soundbite has been around for an AGE, and my usual reaction […] via The Radical Notion That Women Are People — Jane Clare Jones

0 notes

Quote

Thus then are we to see him in a new independent capacity, though perhaps far from an improved one. Teufelsdrockh is now a man without Profession. Quitting the common Fleet of herring-busses and whalers, where indeed his leeward, laggard condition was painful enough, he desperately steers off, on a course of his own, by sextant and compass of his own. Unhappy Teufelsdrockh! Though neither Fleet, nor Traffic, nor Commodores pleased thee, still was it not *a Fleet*, sailing in prescribed track, for fixed objects; above all, in combination, wherein, by mutual guidance, by all manner of loans and borrowings, each could manifoldly aid the other? How wilt thou sail in unknown seas; and for thyself find that shorter Northwest Passage to thy fair Spice-country of a Nowhere?—A solitary rover, on such a voyage, with such nautical tactics, will meet with adventures. Nay, as we forthwith discover, a certain Calypso-Island detains him at the very outset; and as it were falsifies and oversets his whole reckoning.

Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Rather than a big figure, I guess you could say I'm more of an influential minority symbol. " —Takashi Murakami

The artist was born today, February 1, in Tokyo, Japan. TakashiMurakami #ArtistBirthday #Gagosian

___________

Image: "Self-Portrait of the Manifold Worries of a Manifoldly Distressed Artist," 2012, acrylic on canvas mounted on board 59 × 59 inches (150 × 150 cm) © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

So in your introduction you say "Every subversion of freedom..." What do you mean by 'freedom', what is freedom to you?

That quote is from a 1954 issue of the Journal of International Affairs. I pulled it because I thought it nicely encapsulated the way 1950s Americans thought about the Cold War and the Communist enemy. This is the context in which it appears:

In today's highly interdependent world, events in even the remotest of areas can assume critical significance. Whenever and wherever the Soviets succeed in extending their influence, the threat to American security becomes manifoldly greater. Every subversion of freedom, no matter where it occurs, brings the goal of Communist world hegemony closer to realization. Every action by the United States in support of those countries threatened by Soviet expansionism is a formidable obstacle to this threat and greatly strengthens the American position.

If the question is, what did the author mean by the word “freedom”, then I’d say that its most immediate definition within the context of the article is “the absence of Communist subversion.”

More generally, Cold War Americans were deeply shaped by the experience of WWII, and their conception of freedom would have matched up with Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. After far as Americans were concerned, Communist/Soviet rule (Americans didn’t distinguish between the two) violated all four of them: the freedom of speech and expression (the Party determined what ideas could be expressed – and even, according to more sensationalist depictions like Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, thought); the freedom to worship God in his own way (Communism was Godless and oppressed believers through its insistence on conformity to Party ideology); freedom from want (it was obvious that most Russians lived in poverty); and freedom from fear (Communists ruled through terror, making heavy use of secret police, show trials, concentration camps, etc).

If Communism is un-freedom by definition, and all the world is interconnected, then the appearance of Communism anywhere in the globe threatens freedom everywhere. From that flowed the Cold War, containment, the domino theory, and America’s involvement in proxy wars from Vietnam to Afghanistan.

If the question is, how do I, personally, define freedom, then the short of it is I don’t know, at least not right now, and coming up with an answer would demand a lot more time and thought.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archaeologists and construction workers are teaming up to unearth historic relics

Workers exhume rows of graves near London’s Euston Station, the terminus of a new train line. (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images/)

Matthew Flinders is barely 40, but he looks 70. His once dark hair gleams white, his already slight frame skeletal. As a captain in the British Royal Navy, he’s survived shipwreck, imprisonment, and scurvy, but this kidney infection will do him in. Facing death, he finishes writing a book that will change the world as Europeans know it. Flinders completed the first circumnavigation of the “Terra Australis Incognita,” or “Unknown South Land,” in 1803. A decade later, he compiles his writings, maps, charts, and drawings of the rugged coasts, extensive reefs, fertile slopes, unusual wildlife, and other features of the faraway continent that he suggests naming “Australia.”

His wife places a copy of the freshly printed book, A Voyage to Terra Australis, in his hands as he lies unconscious in their central London home the day before his death in July 1814. Later, he’s interred at St. James’s burial ground, but within a few decades, the tombstone is missing. When the railways at nearby Euston Station expand in the mid-1800s, workers relocate, pave over, or strip graves. Lost in a subterranean terra incognita, the explorer might lie somewhere under track 12. Or 15. Or the garden that’s replaced the cemetery. No one knows.

Today, a bronze Flinders at the station entrance crouches over a map alongside his beloved cat Trim, who also made the trip around Australia. If the statue could lift its head, it would see commuters rushing across the plaza past construction barriers. The hub is expanding again, now as a new terminus of the huge HS2 high-speed rail project, which will connect the capital with points north.

This time, though, a team is carefully exhuming and documenting remains before the tunnel-boring, track-laying, and platform-building begins. They know that Flinders and an estimated 61,000 others were buried here between 1789 and 1853. But, with only 128 out-of-place headstones remaining, they don’t know who they’ll find.

Caroline Raynor, an archaeologist with the construction company Costain, leads the excavation. On a typically overcast day in January 2019, she oversees work beneath what she calls her “cathedral to archaeology,” a white bespoke tent so massive that it could house a Boeing 747. It shields a hard-hat-clad crew of more than 100—and the dead, sometimes stacked in columns of up to 10 as much as 27 feet deep.

Where the London clay is waterlogged and oxygenless, delicate materials survive. Clearing earth by hand and trowel over the course of a yearslong job, Raynor’s diggers uncover bodies wearing wooden prosthetics, as well as the Dickensian bonnets that used to hold the deads’ mouths closed. One man still sports blue slippers from Bombay. Even plants and flowers remain. “Some of them were still green,” Raynor says.

Suddenly, a crewmember runs over with news about a grave fairly near the surface. Very little of the coffin is intact—wood doesn’t fare well in the granular, free-draining topsoil—so there’s nothing to open. A lead breastplate rests atop a bare skeleton: “Capt. Matthew Flinders R.N. Died July 1814 Aged 40 Years.”

The discovery is one small chapter in the saga the HS2 project promises to tell. If the first stage of the $115 billion initiative is fully realized, the train will cut through ancient woodlands, suburbs, and cities along the 143 miles between Birmingham in the north and London in the south—though not before teams like Raynor’s uncover any underground treasures. “It looks like we’re finding archaeology from every phase of post-glacial history,” says Mike Court, the archaeologist overseeing the more than 60 planned digs for HS2 Ltd., the entity carrying out the rail initiative. “It’s going to give us an opportunity to have a complete story of the British landscape.”

With more than 1,000 scientists and conservators involved, the scale of HS2’s excavations is unprecedented in the UK, and perhaps all of Europe. However, it’s hardly an outlier. As development continues to tear through hidden civilizations across the continent, investigations like this are becoming common; in fact, they’re often required by legislation. While researchers once bored trenches exclusively on behalf of museums and universities, many now work on job sites. These commercial archaeologists dig up and analyze finds for private companies like the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), a primary contractor on HS2. Because their work is tied to the pace and scale of building projects, their targets are quite random, and discoveries can be boom or bust. Sometimes they’ll unearth just a few graves during housing construction; other times they’ll turn up dizzying amounts of data on battlefields and cemeteries in the path of huge public works.

When efforts at Euston wrapped in December 2019, Raynor’s crew had uncovered some 25,000 of the boneyard’s residents, including ghosts like auction-house founder James Christie and sculptor Charles Rossi, whose caryatids watch over the nearby Crypt of St. Pancras Church. Gazing at the site from her makeshift office, Raynor marvels at the scope of the work still ahead: “It’s very difficult to dig a hole anywhere in the UK without finding something that directly relates to human history in these islands.”

More than 60 excavation sites dot the first phase of the HS2 rail project. (Violet Reed/)

Construction and archaeology weren’t always so close-knit. Through much of the 20th century, builders in the UK often haphazardly regarded artifacts and ruins. Sites were rescued only by the goodwill of developers or ad hoc government intervention.

The chance discovery of the Rose in the late 1980s spurred England to adopt new rules. Among the brothels, gaming dens, and bear-baiting arenas on the south bank of the River Thames, the Rose was one of the first theaters to stage the works of William Shakespeare, including the debut of Titus Andronicus. The construction team had the right to pave over it after only a partial excavation, and the government wasn’t eager to step in to fund a preservation.

Actors like Sir Ian McKellen, Dame Judi Dench, and Sir Laurence Olivier joined calls to save the 16th-century playhouse. At 81, Dame Peggy Ashcroft was on the front line blocking bulldozers. The builders wound up saving the theater, spending $17 million more than planned.

To avoid future conflicts, in 1990 the country adapted a “polluter pays” model for mitigating harm to cultural heritage. Now developers must research potential discoveries as part of their environmental-impact assessment, avoid damaging historic resources, and fund the excavation and conservation of significant sites and artifacts.

That tweak led to “vast changes” in the UK, says Timothy Darvill, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University in England. “Just the sheer number of projects that were undertaken increased manifoldly.” According to his research, thousands of digs occurred per year in Britain from 1990 to 2010, increasing tenfold from decades prior.

Other governments followed suit. Most European countries have signed the 1992 Valletta Convention, a treaty that codified the practice of preservation in the face of construction. Findings published by the European Archaeological Council in 2018 show that developers now lead as much as 90 percent of investigations on the continent.

Archaeologists have opportunities to uncover enormous swaths of history on sites that logistically and financially might have been inaccessible before—especially in the course of major civil-engineering initiatives. Infrastructure authorities have funded multimillion-dollar projects to turn up mass graves on Napoleonic battlefields in the path of an Austrian highway, and 2,000-year-old ruins under Rome during a subway expansion.

Before HS2 became Britain’s banner big dig, Crossrail was the nation’s largest such program. Beginning in 2009, efforts ahead of the 73-mile train line across London revealed thousands of gems at 40 sites: fragments of a medieval fishing vessel, Roman skulls, a Tudor-era bowling ball, and 3,000 skeletons at the graveyard of the notorious Bedlam mental asylum.

To carry out all this work, many nations have competitive commercial markets for research and excavation. MOLA, an offspring of the Museum of London, is one of the largest British firms, and HS2 is one of its major clients. Its field crew surfaces thousands of objects destined for cataloging by a team of staffers on the other side of town.

MOLA headquarters sits in an old wharf building on the edge of a canal in East London’s Islington borough. The ground-floor loading bay leads to a labyrinth of rooms of dusty 20-foot-high shelves packed with dirt-caked finds trucked in from the field. Pallets and containers full of architectural stones, pottery fragments, and tubes of sediment flank narrow aisles. Thanks to the glut of construction-backed excavations, spaces like these see a constant flow of goods demanding attention.

In a small office near the maze, a researcher holds a human skull. Alba Moyano Alcántara is a “processor,” using a paintbrush to dab away soil on the centuries-old cranium. Like a triage nurse, she’ll decide the next steps for these remains and other artifacts. Damp bones will dry slowly on racks in a warm room down the hall; pieces of metal get X-rayed to reveal their original forms.

Eventually, they’ll head upstairs, where MOLA’s specialists catalog the minute details of the finds. In an open-plan office, senior osteologists Niamh Carty and Elizabeth Knox inspect a pair of incomplete skeletons. Carty studies the top half of a young woman; Knox, the bottom half of a man. Truncated bodies are common in old boneyards, where new graves often cut into old ones. Confidentiality agreements with clients keep the researchers mum on the exact origin of the remains, but they offer that these are from a “post-medieval cemetery.” If it wasn’t St. James’s, it was a place like it.

The thousands of skeletons that pass through MOLA contribute to a database of London’s population-wide rates of pathology, injuries, and other bioarchaeological information from prehistory to the Victorian era. “Every skeleton we look at is adding to the bigger picture,” Carty says.

She lingers over a rotted-out tooth, which likely caused a painful abscess before this young woman died. Knox’s skeleton’s lower legs have an irregular curvature, perhaps a sign that he suffered from rickets in his youth; his spine has Schmorl’s nodes, little indentations on the vertebrae created by age or manual labor. “Archaeologists probably all have them,” Knox quips.

Sometimes a small sample can shed light on nationwide phenomena. The Crossrail dig uncovered a burial pit from the 17th-century Great Plague of London, which killed nearly one-quarter of the population. In teeth from that site, researchers discovered the DNA of the bacteria that caused the outbreak. Analysis of all the HS2 remains might one day reveal migration and disease patterns from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution.

MOLA employees also gain insight from individual artifacts. Across the office, Owen Humphreys and Michael Marshall—so-called finds specialists—study uncommon relics weeded out from the pottery pieces, nails, animal bones, and other abundant objects destined for bulk inventorying. “I once likened our job to being the seagull in The Little Mermaid,” Humphreys says. “People bring us things, and we take a wild stab in the dark as to what they are—”

“—a very well-informed stab,” Marshall adds. He holds the wooden leg of a Roman couch found on the Thames waterfront, its paint still red nearly 2,000 years later. “You very rarely get things like this in Britain,” he says. “It’s lucky that we got an opportunity to find out a bit more about what people’s homes looked like.”

These inspections can help determine the objects’ fates. The Museum of London houses the world’s largest archaeological archive of more than 7 million items from more than 8,000 excavations awaiting further study, placement in a collection, or, in the case of the St. James’s bones, reburial. A precious few finds will earn spots on public display.

An archaeologist carefully cleans one of the thousands of bodies uncovered in St. James’s burial ground in London. (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images/)

Leather shoes, wooden combs, an amber carving of a gladiator’s helmet, and some 600 other Roman artifacts adorn the ground floor of Bloomberg LP’s new European headquarters in central London. The nine-story structure sits on the site of a 3rd-century Roman temple dedicated to the god Mithras. First discovered during construction of an office building in the 1950s, the Mithraeum suffered an infamously botched reconstruction deemed ��virtually meaningless” by the site’s lead archaeologist.

After MOLA reexcavated in 2014 on behalf of Bloomberg, the developers had another shot to tell the temple’s story. Now visitors descend several flights of stairs into a darkened room. Light and mist create the illusion of complete walls extending from the stubby foundations of the subterranean temple. Footsteps and ominous Latin chanting piped in from the speakers crescendo, transforming this ruin into the site of secret cult rituals.

To be sure, many builders see archaeology as a compulsory, time-consuming, and expensive hurdle. There’s little publicly available information on the costs for these investigations, even for HS2, but according to the research of Bournemouth archaeologist Darvill, digging might add an extra several million dollars, depending on the scope of the plans. Still, the flashy new Mithraeum is evidence that some have found a symbiosis in using the past to try to make their projects more palatable to locals. Across the city in Shoreditch, a once-gritty East London neighborhood now synonymous with gentrification, the remains of a 16th-century Shakespearean playhouse called the Curtain Theatre will be incorporated into a new multipurpose development. According to the ad copy, the Stage will be an “iconic new showcase for luxury living,” and the “first World Heritage Site in East London.”

The archaeology story of HS2 will be too sprawling to fit neatly in a basement or lobby. It will take years to process and analyze all its finds. As of fall 2019, only the two biggest digs had finished: St. James’s and the excavation of another 6,500 graves from an Industrial Revolution-era cemetery at the Birmingham station.

HS2 archaeologists are now running test trenches to decide precisely which spots they’ll uncover in between. “Some of them are once-in-a-generation archaeological sites, and some are smaller, still interesting, but not large scale,” says project field lead Court. We already know that HS2 will cut through a mysterious prehistoric earthwork called Grim’s Ditch in the hills outside London, and farther north, a Roman town and a millennia-old demolished church. Researchers also hope to find traces from the Battle of Edgecote Moor, which broke out in Northamptonshire in 1469 during the Wars of the Roses.

The fate of HS2’s archaeological ambitions, however, is entangled with what has become an increasingly unpopular infrastructure project. Prime Minister Boris Johnson ordered a review to determine whether the rail should be scrapped because of ballooning costs and delays. Critics argue that the benefits won’t outweigh the environmental disruption, the land seizures, and the financial burden to taxpayers. The community around Euston Station protested the construction, which gouged a green space, and leveled homes, offices, and hotels, displacing longtime residents who complained about shoddy compensation. The vicar of a nearby church even chained herself to a tree.

In such a controversial effort, any incidental cultural benefits are bound to conjure a degree of suspicion. “I’m fascinated by the stories that the dig at St. James’s Gardens is helping to bring to light,” says Brian Logan, the artistic director of the Camden People’s Theater, located at the doorstep of the site. “But I think you can be enthusiastic about archaeology while being a little skeptical of the purposes to which it’s being put.” In the first act of a 2019 performance that dealt with those issues, Logan knocked the project’s PR department for casting the rail as a bonanza for discovery: “Is archaeology really a profession we want to run on a bonanza basis?”

In the era of developer-led digging, that’s a question practitioners are reckoning with too. Costain archaeologist Raynor, whose focus now turns from St. James’s to the 15 miles of track leading out of Euston Station, would at least agree that her profession lacks sustainability. According to Darvill, half of archaeologists work in jobs tied to construction.

Bonanza-like conditions also create a gold rush of information—a blessing and a curse. With overstuffed basements, museums around the world face a storage crisis, and more digging might only compound the problem, especially now that archaeologists consider sites as recent as World War II worthy of study. Raynor sees the management of all that information as the bigger challenge—not just for scientific analysis, but also for public consumption. The excavation at St. James’s alone generated 3.5 terabytes of data. “It loses meaning if you don’t communicate it,” she says.

Luckily, communication is the easier piece of the puzzle. In Raynor’s experience, people viscerally react to pots, bowls, tools, and other bric-a-brac from the past. “As human beings, our wants, needs, and desires haven’t changed that much,” she says.

While the saga of HS2 is still being written, those small finds might resonate as much with the public as the discoveries of icons, like Matthew Flinders, whose life stories are embedded in the UK’s ever-changing stratigraphy. Flinders himself wouldn’t recognize Euston Station today, nor would he have thought he’d be an interesting scientific specimen. For better or worse, he helped chart a course through history, only to find himself in its path.

This story appears in the Spring 2020, Origins issue of Popular Science.

0 notes

Text

Archaeologists and construction workers are teaming up to unearth historic relics

Workers exhume rows of graves near London’s Euston Station, the terminus of a new train line. (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images/)

Matthew Flinders is barely 40, but he looks 70. His once dark hair gleams white, his already slight frame skeletal. As a captain in the British Royal Navy, he’s survived shipwreck, imprisonment, and scurvy, but this kidney infection will do him in. Facing death, he finishes writing a book that will change the world as Europeans know it. Flinders completed the first circumnavigation of the “Terra Australis Incognita,” or “Unknown South Land,” in 1803. A decade later, he compiles his writings, maps, charts, and drawings of the rugged coasts, extensive reefs, fertile slopes, unusual wildlife, and other features of the faraway continent that he suggests naming “Australia.”

His wife places a copy of the freshly printed book, A Voyage to Terra Australis, in his hands as he lies unconscious in their central London home the day before his death in July 1814. Later, he’s interred at St. James’s burial ground, but within a few decades, the tombstone is missing. When the railways at nearby Euston Station expand in the mid-1800s, workers relocate, pave over, or strip graves. Lost in a subterranean terra incognita, the explorer might lie somewhere under track 12. Or 15. Or the garden that’s replaced the cemetery. No one knows.

Today, a bronze Flinders at the station entrance crouches over a map alongside his beloved cat Trim, who also made the trip around Australia. If the statue could lift its head, it would see commuters rushing across the plaza past construction barriers. The hub is expanding again, now as a new terminus of the huge HS2 high-speed rail project, which will connect the capital with points north.

This time, though, a team is carefully exhuming and documenting remains before the tunnel-boring, track-laying, and platform-building begins. They know that Flinders and an estimated 61,000 others were buried here between 1789 and 1853. But, with only 128 out-of-place headstones remaining, they don’t know who they’ll find.

Caroline Raynor, an archaeologist with the construction company Costain, leads the excavation. On a typically overcast day in January 2019, she oversees work beneath what she calls her “cathedral to archaeology,” a white bespoke tent so massive that it could house a Boeing 747. It shields a hard-hat-clad crew of more than 100—and the dead, sometimes stacked in columns of up to 10 as much as 27 feet deep.

Where the London clay is waterlogged and oxygenless, delicate materials survive. Clearing earth by hand and trowel over the course of a yearslong job, Raynor’s diggers uncover bodies wearing wooden prosthetics, as well as the Dickensian bonnets that used to hold the deads’ mouths closed. One man still sports blue slippers from Bombay. Even plants and flowers remain. “Some of them were still green,” Raynor says.

Suddenly, a crewmember runs over with news about a grave fairly near the surface. Very little of the coffin is intact—wood doesn’t fare well in the granular, free-draining topsoil—so there’s nothing to open. A lead breastplate rests atop a bare skeleton: “Capt. Matthew Flinders R.N. Died July 1814 Aged 40 Years.”

The discovery is one small chapter in the saga the HS2 project promises to tell. If the first stage of the $115 billion initiative is fully realized, the train will cut through ancient woodlands, suburbs, and cities along the 143 miles between Birmingham in the north and London in the south—though not before teams like Raynor’s uncover any underground treasures. “It looks like we’re finding archaeology from every phase of post-glacial history,” says Mike Court, the archaeologist overseeing the more than 60 planned digs for HS2 Ltd., the entity carrying out the rail initiative. “It’s going to give us an opportunity to have a complete story of the British landscape.”

With more than 1,000 scientists and conservators involved, the scale of HS2’s excavations is unprecedented in the UK, and perhaps all of Europe. However, it’s hardly an outlier. As development continues to tear through hidden civilizations across the continent, investigations like this are becoming common; in fact, they’re often required by legislation. While researchers once bored trenches exclusively on behalf of museums and universities, many now work on job sites. These commercial archaeologists dig up and analyze finds for private companies like the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA), a primary contractor on HS2. Because their work is tied to the pace and scale of building projects, their targets are quite random, and discoveries can be boom or bust. Sometimes they’ll unearth just a few graves during housing construction; other times they’ll turn up dizzying amounts of data on battlefields and cemeteries in the path of huge public works.

When efforts at Euston wrapped in December 2019, Raynor’s crew had uncovered some 25,000 of the boneyard’s residents, including ghosts like auction-house founder James Christie and sculptor Charles Rossi, whose caryatids watch over the nearby Crypt of St. Pancras Church. Gazing at the site from her makeshift office, Raynor marvels at the scope of the work still ahead: “It’s very difficult to dig a hole anywhere in the UK without finding something that directly relates to human history in these islands.”

More than 60 excavation sites dot the first phase of the HS2 rail project. (Violet Reed/)

Construction and archaeology weren’t always so close-knit. Through much of the 20th century, builders in the UK often haphazardly regarded artifacts and ruins. Sites were rescued only by the goodwill of developers or ad hoc government intervention.

The chance discovery of the Rose in the late 1980s spurred England to adopt new rules. Among the brothels, gaming dens, and bear-baiting arenas on the south bank of the River Thames, the Rose was one of the first theaters to stage the works of William Shakespeare, including the debut of Titus Andronicus. The construction team had the right to pave over it after only a partial excavation, and the government wasn’t eager to step in to fund a preservation.

Actors like Sir Ian McKellen, Dame Judi Dench, and Sir Laurence Olivier joined calls to save the 16th-century playhouse. At 81, Dame Peggy Ashcroft was on the front line blocking bulldozers. The builders wound up saving the theater, spending $17 million more than planned.

To avoid future conflicts, in 1990 the country adapted a “polluter pays” model for mitigating harm to cultural heritage. Now developers must research potential discoveries as part of their environmental-impact assessment, avoid damaging historic resources, and fund the excavation and conservation of significant sites and artifacts.

That tweak led to “vast changes” in the UK, says Timothy Darvill, an archaeologist at Bournemouth University in England. “Just the sheer number of projects that were undertaken increased manifoldly.” According to his research, thousands of digs occurred per year in Britain from 1990 to 2010, increasing tenfold from decades prior.

Other governments followed suit. Most European countries have signed the 1992 Valletta Convention, a treaty that codified the practice of preservation in the face of construction. Findings published by the European Archaeological Council in 2018 show that developers now lead as much as 90 percent of investigations on the continent.

Archaeologists have opportunities to uncover enormous swaths of history on sites that logistically and financially might have been inaccessible before—especially in the course of major civil-engineering initiatives. Infrastructure authorities have funded multimillion-dollar projects to turn up mass graves on Napoleonic battlefields in the path of an Austrian highway, and 2,000-year-old ruins under Rome during a subway expansion.

Before HS2 became Britain’s banner big dig, Crossrail was the nation’s largest such program. Beginning in 2009, efforts ahead of the 73-mile train line across London revealed thousands of gems at 40 sites: fragments of a medieval fishing vessel, Roman skulls, a Tudor-era bowling ball, and 3,000 skeletons at the graveyard of the notorious Bedlam mental asylum.

To carry out all this work, many nations have competitive commercial markets for research and excavation. MOLA, an offspring of the Museum of London, is one of the largest British firms, and HS2 is one of its major clients. Its field crew surfaces thousands of objects destined for cataloging by a team of staffers on the other side of town.

MOLA headquarters sits in an old wharf building on the edge of a canal in East London’s Islington borough. The ground-floor loading bay leads to a labyrinth of rooms of dusty 20-foot-high shelves packed with dirt-caked finds trucked in from the field. Pallets and containers full of architectural stones, pottery fragments, and tubes of sediment flank narrow aisles. Thanks to the glut of construction-backed excavations, spaces like these see a constant flow of goods demanding attention.

In a small office near the maze, a researcher holds a human skull. Alba Moyano Alcántara is a “processor,” using a paintbrush to dab away soil on the centuries-old cranium. Like a triage nurse, she’ll decide the next steps for these remains and other artifacts. Damp bones will dry slowly on racks in a warm room down the hall; pieces of metal get X-rayed to reveal their original forms.

Eventually, they’ll head upstairs, where MOLA’s specialists catalog the minute details of the finds. In an open-plan office, senior osteologists Niamh Carty and Elizabeth Knox inspect a pair of incomplete skeletons. Carty studies the top half of a young woman; Knox, the bottom half of a man. Truncated bodies are common in old boneyards, where new graves often cut into old ones. Confidentiality agreements with clients keep the researchers mum on the exact origin of the remains, but they offer that these are from a “post-medieval cemetery.” If it wasn’t St. James’s, it was a place like it.

The thousands of skeletons that pass through MOLA contribute to a database of London’s population-wide rates of pathology, injuries, and other bioarchaeological information from prehistory to the Victorian era. “Every skeleton we look at is adding to the bigger picture,” Carty says.

She lingers over a rotted-out tooth, which likely caused a painful abscess before this young woman died. Knox’s skeleton’s lower legs have an irregular curvature, perhaps a sign that he suffered from rickets in his youth; his spine has Schmorl’s nodes, little indentations on the vertebrae created by age or manual labor. “Archaeologists probably all have them,” Knox quips.

Sometimes a small sample can shed light on nationwide phenomena. The Crossrail dig uncovered a burial pit from the 17th-century Great Plague of London, which killed nearly one-quarter of the population. In teeth from that site, researchers discovered the DNA of the bacteria that caused the outbreak. Analysis of all the HS2 remains might one day reveal migration and disease patterns from the Middle Ages to the Industrial Revolution.

MOLA employees also gain insight from individual artifacts. Across the office, Owen Humphreys and Michael Marshall—so-called finds specialists—study uncommon relics weeded out from the pottery pieces, nails, animal bones, and other abundant objects destined for bulk inventorying. “I once likened our job to being the seagull in The Little Mermaid,” Humphreys says. “People bring us things, and we take a wild stab in the dark as to what they are—”

“—a very well-informed stab,” Marshall adds. He holds the wooden leg of a Roman couch found on the Thames waterfront, its paint still red nearly 2,000 years later. “You very rarely get things like this in Britain,” he says. “It’s lucky that we got an opportunity to find out a bit more about what people’s homes looked like.”

These inspections can help determine the objects’ fates. The Museum of London houses the world’s largest archaeological archive of more than 7 million items from more than 8,000 excavations awaiting further study, placement in a collection, or, in the case of the St. James’s bones, reburial. A precious few finds will earn spots on public display.

An archaeologist carefully cleans one of the thousands of bodies uncovered in St. James’s burial ground in London. (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images/)

Leather shoes, wooden combs, an amber carving of a gladiator’s helmet, and some 600 other Roman artifacts adorn the ground floor of Bloomberg LP’s new European headquarters in central London. The nine-story structure sits on the site of a 3rd-century Roman temple dedicated to the god Mithras. First discovered during construction of an office building in the 1950s, the Mithraeum suffered an infamously botched reconstruction deemed “virtually meaningless” by the site’s lead archaeologist.

After MOLA reexcavated in 2014 on behalf of Bloomberg, the developers had another shot to tell the temple’s story. Now visitors descend several flights of stairs into a darkened room. Light and mist create the illusion of complete walls extending from the stubby foundations of the subterranean temple. Footsteps and ominous Latin chanting piped in from the speakers crescendo, transforming this ruin into the site of secret cult rituals.

To be sure, many builders see archaeology as a compulsory, time-consuming, and expensive hurdle. There’s little publicly available information on the costs for these investigations, even for HS2, but according to the research of Bournemouth archaeologist Darvill, digging might add an extra several million dollars, depending on the scope of the plans. Still, the flashy new Mithraeum is evidence that some have found a symbiosis in using the past to try to make their projects more palatable to locals. Across the city in Shoreditch, a once-gritty East London neighborhood now synonymous with gentrification, the remains of a 16th-century Shakespearean playhouse called the Curtain Theatre will be incorporated into a new multipurpose development. According to the ad copy, the Stage will be an “iconic new showcase for luxury living,” and the “first World Heritage Site in East London.”

The archaeology story of HS2 will be too sprawling to fit neatly in a basement or lobby. It will take years to process and analyze all its finds. As of fall 2019, only the two biggest digs had finished: St. James’s and the excavation of another 6,500 graves from an Industrial Revolution-era cemetery at the Birmingham station.

HS2 archaeologists are now running test trenches to decide precisely which spots they’ll uncover in between. “Some of them are once-in-a-generation archaeological sites, and some are smaller, still interesting, but not large scale,” says project field lead Court. We already know that HS2 will cut through a mysterious prehistoric earthwork called Grim’s Ditch in the hills outside London, and farther north, a Roman town and a millennia-old demolished church. Researchers also hope to find traces from the Battle of Edgecote Moor, which broke out in Northamptonshire in 1469 during the Wars of the Roses.

The fate of HS2’s archaeological ambitions, however, is entangled with what has become an increasingly unpopular infrastructure project. Prime Minister Boris Johnson ordered a review to determine whether the rail should be scrapped because of ballooning costs and delays. Critics argue that the benefits won’t outweigh the environmental disruption, the land seizures, and the financial burden to taxpayers. The community around Euston Station protested the construction, which gouged a green space, and leveled homes, offices, and hotels, displacing longtime residents who complained about shoddy compensation. The vicar of a nearby church even chained herself to a tree.

In such a controversial effort, any incidental cultural benefits are bound to conjure a degree of suspicion. “I’m fascinated by the stories that the dig at St. James’s Gardens is helping to bring to light,” says Brian Logan, the artistic director of the Camden People’s Theater, located at the doorstep of the site. “But I think you can be enthusiastic about archaeology while being a little skeptical of the purposes to which it’s being put.” In the first act of a 2019 performance that dealt with those issues, Logan knocked the project’s PR department for casting the rail as a bonanza for discovery: “Is archaeology really a profession we want to run on a bonanza basis?”

In the era of developer-led digging, that’s a question practitioners are reckoning with too. Costain archaeologist Raynor, whose focus now turns from St. James’s to the 15 miles of track leading out of Euston Station, would at least agree that her profession lacks sustainability. According to Darvill, half of archaeologists work in jobs tied to construction.

Bonanza-like conditions also create a gold rush of information—a blessing and a curse. With overstuffed basements, museums around the world face a storage crisis, and more digging might only compound the problem, especially now that archaeologists consider sites as recent as World War II worthy of study. Raynor sees the management of all that information as the bigger challenge—not just for scientific analysis, but also for public consumption. The excavation at St. James’s alone generated 3.5 terabytes of data. “It loses meaning if you don’t communicate it,” she says.

Luckily, communication is the easier piece of the puzzle. In Raynor’s experience, people viscerally react to pots, bowls, tools, and other bric-a-brac from the past. “As human beings, our wants, needs, and desires haven’t changed that much,” she says.

While the saga of HS2 is still being written, those small finds might resonate as much with the public as the discoveries of icons, like Matthew Flinders, whose life stories are embedded in the UK’s ever-changing stratigraphy. Flinders himself wouldn’t recognize Euston Station today, nor would he have thought he’d be an interesting scientific specimen. For better or worse, he helped chart a course through history, only to find himself in its path.

This story appears in the Spring 2020, Origins issue of Popular Science.

0 notes