#so much well-documented evidence of queer history from all over the world

Text

Trying to keep my history thoughts on the matter to myself online so that I don't get turbo cancelled but I just have to point out that there is a huge difference between THE British Museum and A British museum.

For Christ's sake.

#like that's just factually incorrect#THE British Museum made no such proclamation#one small museum in hertfordshire did#also all sources about this person were written by enemies#and should not be regarded as an unbiased account of firsthand statements#it's just...... such an ahistorical sloppy decision#like there is so much queer history#so much well-documented evidence of queer history from all over the world#and you pick this#and attach an uncontemporaneous modern-lens category to it based on political slander#i suppose it did its job though by generating press for the museum

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

This is a transcript of a speech by developmental biologist Dr Emma Hilton delivered on 29 November 2020 for the ‘Feminist Academics Talk Back!’ meeting. This talk was originally published by womentalkback.org

Sex denialists have captured existing journals

We are dealing with a new religion

Thank you for the invitation to speak today, as a feminist academic fighting back.

As ever, let’s begin with a story. And, trust me, by the end of this talk, you’re going to know a lot more about creationism that you expected:

1. In the 1920s, in concert with many other American states, the Tennessee House of Representatives passed the Butler Act, making it illegal for state public schools to: “teach any theory that denies the Story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible.” In other words, banning schools from teaching the theory of evolution.

Three months later, Tennessee science teacher John Scopes was on trial, charged with teaching the theory of evolution, a crime he was ultimately found guilty of. He was fined £71 – about £1064 in today’s money – so it could have been an expensive affair for him, had he not got off on a really boring administrative technicality.

Yet, despite the evidence against him and his own confession, he was an innocent man. Scopes was not guilty of teaching the theory of evolution. He admitted to a crime he had not committed. He even coached his students in their testimonies against him. So why would he admit to this wrongdoing of which he was entirely innocent? Why would he contrive apparent guilt? In protest. In protest against a law he viewed as fundamentally incompatible with the pursuit of scientific truth.

2. The history of creationism and education laws in the US is turbulent and often opaquely legalese, especially for those of us unfamiliar with US law. Some of the methods of the wider creationist movement, however, will be immediately recognisable as they are employed by a new movement, one which seeks to erase another scientific truth, the fact of sex.

Method 1. The framing of human classifications, whether it’s species or sex, as “arbitrary”. This leads to the premise that such phenomena are “social constructs” that need not exist if we chose to reject them. That truth must be relative and consensual. Never mind that these “arbitrary” classifications appear to be surprisingly similar classifications across all cultures and civilisations.

It also necessarily spotlights tricky boundary cases – not really a personal problem for the long-dead evolutionary missing links, but a very real problem in the modern world for people whose sex is atypical and who are constantly invoked, even fetishized, as “not males” or “not females” to prove sex classification is somehow no more than human whimsy.

People with DSDs have complex and often traumatic medical histories, perhaps struggling to understand their bodies, and they deserve more respect than to be casually and thoughtlessly used as a postemodernist “gotcha” by the very people so horribly triggered by a pronoun.

Method 2. The distortion of science and the development of sciencey language to create a veneer of academic rigour. Creationists invented “irreducible complexity” and “specified complexity” while Sex denialists try to beat people over the head with their dazzling arrays of “bimodal distributions arranged in n-dimensional space”.

Creationists, unable to publish in mainstream science journals because they weren’t producing, well, science, established their own journals. “Journals”. Sex denialists have captured existing journals – albeit limited to more newsy ones and to occasional editorials and blogs about gender (which is not sex), about how developmental biology is soooo complicated (which does not mean sex is complicated – I mean, the internal combustion engine is complicated but cars still fundamentally go forwards or backwards), about how discussing the biology of sex is mean (OK, good luck with that at your doctor’s surgery). Many such blogs and articles are written by scientists who simultaneously deny sex to their social media audience while writing academic papers about how female fruitflies make shells for their eggs (no matter how queer they are), about the development of ovaries or testes in fish and about how males make sperm.

The current editor-in-chief at Nature, the first female to hold this position, studied sex determination in worms for her PhD, and she now presides over a journal with an editorial policy to insert disclaimers about the binary nature of sex into spotlight features about research on, for example, different death rates in male and female cystic fibrosis patients.

The authors of the studies are not prevaricating or handwaving about sex, but the editorial team is “bending the knee”. I used to research a genetic disorder that was male-lethal – that is, male human babies died early in gestation. I’d love to know if this disclaimer would be applied there.

Method 3. Debate strategies like The Gish Gallop. This method is named for Duane Gish, who is a prominent creationist. What it boils down to is: throw any old argument, regardless of its validity, in quick succession at your opponent and then claim any dismissal or missed response or even hesitation in response as a score for your side. In Twitter parlance, we know this as “sealioning”, in political propaganda as the “firehose of falsehood”, although Wikipedia also suggests that it is covered by the term “bullshit”. So, what about intersex people? what about this article? what about an XY person with a uterus? what about the fa’afafine? what about that article? look at this pretty picture. what about what about whataboutery what about clownfish? The aim is not to discuss or debate, it is to force submission from frustration or exhaustion.

Method 4. The reification of humans as separate from not just monkeys but the rest of the living world. The special pleading for special descriptions that frame humans as the chosen ones, such that the same process of making new individuals, common to humans and asparagus, an observation I chose because it seems superficially silly – it could have been spinach – requires its own description, one that accounts for gender identity.

3. In the Scopes trial, which saw discussion of whether Eve was actually created from Adam’s rib and ruminations on where Cain got his wife, Scopes was defended by a legal group who had begun scouting for a test case subject as soon as the Tennessee ban was enacted. This legal group claimed to advocate for:

“Freedom of speech for ideas from the most extreme left such as anarchists and socialists, to the most extreme right including the Ku Klux Klan, Henry Ford, and others who would now be considered more toward the Fascist end of the spectrum.”

The legal group so keen to defend the right to speak the truth, in this case a fundamental, observable scientific truth? The American Civil Liberties Union, a group whose modern day social media presence promotes nonsense like:

“The notion of biological sex was developed for the exclusive purpose of being weaponized against people.”

and

“Sex and gender are different words for the same thing [that is] a set of politically and socially contingent notions of embodied and expressed identity.”

and shares articles asserting that biological sex is rooted in white supremacy.

Since the Scopes case, the ACLU have fought against many US laws preventing, or at least compromising, the teaching of evolution. I cannot process the irony of a group of people historically and consistently prepared to robustly defend the truth of evolution while now denying one of the most important biological foundations of evolution.

4. How do we fight this current craze of sex denialism? A major blow for creationism teaching was delivered in 1986 while the US Supreme Court were considering a Louisiana state law requiring creationism to be taught alongside evolution. The Louisiana law was struck down, in part influenced by the expert opinions, submitted to the court, of scientists who put aside their individual and, as one of them has since described “often violent” differences on Theory X and Experiment Y, to present a unified defence of scientific truth over religious belief. 76 Nobel laureates, 17 state academies of science and a handful of scientific organisations all got behind this single cause, and made a very real change.

Support for creationism has slowly ebbed away and the US is in a much more sensible position these days, although I still meet the occasional student from a Southern state who didn’t learn about evolution until college.

Sadly, one of the Nobel laureates has highlighted how unusual this collective response was and that he could not imagine any other issue that would receive the same groundswell of community support. Although he forged his career listening out for the Big Bang, so maybe I need to go through the list and find the biologists.

Part of the problem petitioning biologists to speak out is not necessarily fear of being cancelled or whatever, but simple lack of awareness of the issue, or incredulity that it is being taken remotely seriously. I’ve been working on a legal document and was discussing with a colleague about my efforts to find a citation for the statement, “there are two sexes, male and female”. He laughed at the idea that this would require a citation, told me to check a textbook, then realised that this statement is so simple that it would not even be included in a textbook.

And he’s right. I can find chapters in textbooks and hundreds of academic papers dedicated to how males and females are made, how they develop, how they differ, yet very few that feel the need to preface any of this with the statement “There are two sexes, male and female”. It is apparently something that biologists do not think needs to be said.

But of course, I think they are wrong, and that we live in a time where it does need to be said, where some aspects of society are being restructured around a scientific untruth, and where females will suffer.

Without recognition of and language to describe our anatomy, and the experiences that stem from that anatomy, mostly uninvited, we can neither detect nor measure things like rates of violence against women, the medical experiences, the social experiences of women and girls.

And, as for creationism, the reality of sex perhaps needs to be said by those with scientific authority, in unambiguous terms. Otherwise, we are living in a society that tolerates nonsense like there is no such thing as male or female, that differences evident to our own eyes are not real, that anatomies readily observable and existing in monkey and man alike do not actually exist. I’m sure this last assertion has the full support of the creationist community. And perhaps, as for creationism, a true tipping point will be tested when it is our children being taught these scientific untruths, or worse, when it is illegal to say different.

5. At the end of his trial, the only words Scopes uttered in court were these:

“Your honor, I feel that I have been convicted of violating an unjust statute. I will continue in the future, as I have in the past, to oppose this law in any way I can. Any other action would be in violation of my ideal of academic freedom—that is, to teach the truth as guaranteed in our constitution, of personal and religious freedom.”

I do not exaggerate when I say we are dealing with a new type of religion, a new form of creationism and a new assault on scientific truth. I also do not exaggerate when I say it may take a high profile court case to rebalance the public discourse around sex. There is only so far letters and opinion articles can go.

Two things I predict: 1. It will not be defended by the ACLU, and 2. With the recent proposals on hate speech law, it will probably involve a Scottish John Scopes, who finds themself in front of a judge for the seditious crime of discussing the sex life of asparagus at their dinner table.

Dr Emma Hilton is a developmental biologist studying aspects of human genetic diseases, and her current research focuses on a congenital motor neurone disease affecting the genitourinary tract, and on respiratory dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. She teaches reproduction, genes, inheritance and genetic disorders. Emma has a special interest in fairness in female sports. A strong advocate for women and girls, Emma tweets as @FondofBeetles.

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 1 – A Mental Mindfuck Can Be Nice – an introduction to EMP theory

I amused myself whilst writing this meta by coming up with referential chapter titles – the song to title this chapter can be found here! (X)

I’m not the first person to propose EMP [extended mind palace] theory and I certainly can’t claim to take the credit for it! After TFP (well, after Apple Tree Yard aired really) I left the fandom, and only rejoined tjlc this year during lockdown and discovered the theory that the entirety of S4 takes place in Sherlock’s Mind Palace, not just TAB, and that even more crucially, the EMP section of the narrative doesn’t happen because of Sherlock’s overdose but rather after Mary shoots him in HLV. Other people have elaborated as to why this is in greater detail and I certainly don’t want to steal their thunder – you can find some of my favourite metas on this here! X X X The original founders’ post is here and great X – it should be noted that the concept of EMP theory appeared way before the superficial shitshow that was series 4, so it was not invented as a fix-it – far from it!

As well as that, tweets from Arwel Wyn Jones (production designer) and Douglas MacKinnon (TAB director) here X X suggest that a lot of the inconsistencies that make HLV onwards quite dreamlike are absolutely deliberate, which has never been explained in the context of the show. In fact, Douglas MacKinnon specifically suggests that the plane could be in Sherlock’s mind, which has no bearing on the superficial plot unless you buy into EMP theory. We’ve also already been shown that the modern day, particularly when it’s fucky, can be in a mind palace illusion in TAB, and we can read that as a kind of rehearsal for the proper fucky mind palace stuff in S4, a clue that everything is not as it seems – much like the Mayfly Man’s murder rehearsal in TSoT.

It's worth pointing out that there are several different versions of EMP theory – I personally subscribe to the idea that this is Sherlock’s mind palace after being shot by Mary, but there are plenty of popular theories on John’s ‘Mind Bungalow’, blog theory, which I don’t want to dismiss out of hand. However, I think the obsession with the figure of Sherlock Holmes and who that might be throughout the fourth series is thematically consistent with it being from Sherlock’s perspective, as is the precedent from TAB.

The other thing I want to lay on the table as foundational to this theory is the fandom’s obsession with TPLoSH [1970 Billy Wilder queer Holmes adaptation, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes]. Mofftiss have long stated their love for TPLoSH and even that it is the adaptation that has most inspired them, and I don’t know a single tjlcer who doesn’t have this quotation from Wilder emblazoned onto their memory.

I should have been more daring. I have this theory. I wanted to have Holmes homosexual and not admitting it to anyone, including maybe even himself. The burden of keeping it secret was the reason he took dope. X

What I’m proposing here is that whilst we’ve thought about this quote quite a lot, we’ve always focused on the first half – that Sherlock Holmes is a homosexual – and not the second, which is that that’s the reason he’s on dope. We talk a bit about Sherlock being upset in HLV about John’s marriage and that being why he turns back to drugs, and likewise when TAB first aired a lot of people (myself included) thought he was ODing because he wasn’t going to see John again. I now think – and will provide evidence through the meta! – that it isn’t his feelings of (seemingly) unrequited love which are sending him to drugs, nor that the EMP is a place where he’s discovering his feelings – my meta here X is not the first to point out that Sherlock almost definitely deduces his own feelings for John in TSoT, in a case of the worst timing in television history. Instead, much like Wilder’s Holmes, I think our Sherlock is dealing with a huge amount of shame and internalised homophobia, which has metafictionally* been building up since Conan Doyle started writing – hence the trip back to 1895 in TAB. S4 is about breaking through over a century of Holmes adaptations which have formed Sherlock’s own version of himself, so that he can break out of them into a ‘Private Life’ outside of established canon.

*Metafictionality is the defining idea around my version of EMP theory, so for anybody who’s not familiar I’m going to do a quick run down. The idea behind metafictionality is that Sherlock is aware of itself as being a work of fiction and deliberately plays with that – in this case, I’m arguing that the character Sherlock is subconsciously aware of the history of book/film/tv adaptations of Sherlock Holmes, and his existence outside Sherlock builds up to create his internalised homophobia. Sounds mad? Maybe. But stick with me here. The reason it’s taking so long for Sherlock to process his sexuality is not just because he’s repressed, but because he’s dealing with the weight of other Holmes adaptations – which is the reason arguably that a modern audience would also take so long to accept it, longer than were this character not such a huge part of the Western psyche.

My aims from this meta:

1. To prove that tjlc remains endgame (eh, if there’s a series 5)

2. To show that s4 is about Sherlock trying to break out of his MP coma after being shot by Mary

3. That s4 engages with the history of Sherlock Holmes adaptations through the character of Sherlock investigating his psyche

4. That in the real (non-MP) world, John is suicidal, and Sherlock has to wake up to save him.

Chapter 1 – A Mental Mindfuck Can Be Nice: a quick summary of EMP theory

Chapter 2 – Look up here, I’m in Heaven: the height metaphor

Chapter 3 – Death Cannot Stop True Love [HLV 1/1]

Chapter 4 – It is always 1895 [TAB 1/1]

Chapter 5 – Hey, Soul Sister: Who is Eurus?

Chapter 6 – So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish [TST 1/2]

Chapter 7 – There’s Something About Mary [TST 2/2]

Chapter 8 – Dream a Little Dream of Me: parallels with Doctor Who

Chapter 9 – Rock’n’roll Suicide [TLD 1/2]

Chapter 10 – Oh No Love, You’re Not Alone [TLD 2/2]

Chapter 11 – The Importance of Being Earnest [TFP 1/3]

Chapter 12 – Three Men in a Boat [TFP 2/3]

Chapter 13 – Out of My Dreams [TFP 3/3]

I’ll (ideally) be uploading a chapter a day for the next 13 days. Some of these chapters will contain links to later chapters; if that chapter isn’t uploaded yet, I’ll add in the link retrospectively, so that might be why the links don’t all work on first read. With chapters that have an episode in parentheses beside, I strongly recommend either watching the episode before reading the meta, or even better to do a simultaneous read and watch through with your finger on the pause button. The only episode which doesn’t do a play by play is TLD 1/2 , purely for time reasons (my college term starts very soon and I really needed this meta put to bed for the sake of my degree!).

The other thing worth saying is that if you want this meta as a word document for some reason, drop me a message – I’m more than happy to share it that way as well. It is a cool 50k so takes some reading. This chapter has been a bit of a nothing, but I hope it lays the groundwork for what to expect from the next 12 – I’ll see you over the next 12 days!

#emp theory#thewatsonbeekeepers#my meta#chapter one#mine#introduction#then I get the fun job of working out how to actually organise my tumblr so people can actually find the shit i write

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Review: “Queer City” by Peter Ackroyd

Thanks to @kyliebean-editing for the review request! I have a list of books I’ve read recently here that I’m considering reviewing, so let me know if you’re looking for my thoughts on a specific book and I’ll be sure to give it a go!

2.5 ⭐/5

Hey all! I’m back with another book review and this time we’re taking a dip into nonfiction with Peter Ackroyd’s Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day. Let’s dive right in.

The good: Peter Ackroyd is a hugely prolific writer and a historian clearly trained for digging through huge archives of history and his expertise shows. This particular volume--his 37th nonfiction book and 55th overall published work--provides a startlingly comprehensive timeline of London’s gay history, just as promised. Arguably, the book’s subtitle short sells the book’s content; Queer City actually rewinds the clock all the way back to the city’s origins as a Celtic town before it became Roman Londinium. From there, Ackroyd’s utilizes his extensive historical experience to trace proof of gay activity through the ages. From the high courts of medieval times to the monks of the Tudor era, the gaslit back alleys of Victorian London to the raging club scene of the 1980s--gay people have lived and even thrived in London for literal millennia, and Ackroyd has the receipts to back it up. If you need proof that homosexuality has been a staple of civilization since the Romans--and the homophobia has often recycled the same arguments for the same period of time--then look no further.

The mediocre: All that being said, Ackroyd’s “receipts” often tend towards the salacious, the scandalous, and often the explicit. It seems that legal edicts and court cases made up the foundation of his research, so us readers get to hear in full detail the punishments levied against historical queer individuals, from exile to the pillory to the gallows. Occasionally, Ackroyd dips into the written pornagraphic accounts of the time to describe salacious sexual encounters, which add little to the overarching narrative except proof that gay people do, in fact, have sex. Later down the historical record, once newspapers became more common, we also receive extensive account of the gossip pages of the day, complete with rants about the indecency of “buggery” and the moral decay of “the homosexual.” Throughout the book, ass puns and phallic wordplay run rampant, so much so that it occasionally feels like it’s only added for shock value.

While I’m not a professional historian, as a queer person I can’t help but feel that there must be more to the historical record than these beatings, back alley hookups, etc. In focus on the concrete evidence of gay activity--that is, gay sex and all the official documents surrounding the subject--it feels like Ackroyd neglects the emotional side of queerness in favor of the physical side. Even the queer poetry excerpts or diary entries of the time (which I’m nearly positive exist throughout the historical record, though once again I’m not a professional) sampled in this book are all focused on the physical act of sex. No queer person wants a pastel tinted, desexed version of our history--but we also don’t need to hear a dozen explicit accounts of gay park sex. Queer love and queer sex go hand in hand and to focus on one without the other is disingenuous, not to mention dangerous in promoting the idea that queer people are hypersexual and predatory. Admittedly, I do think the omission of queer love is an unintentional byproduct of Ackroyd’s fact-checking and editorial process. He may not have intended to leave out tenderness, but his intentional choice to focus on impersonal records--court cases, royal decrees, newspapers, etc.--rather than personal ones--diaries, poetry, art, etc.--meant that emotion was largely excluded anyway.

The bad: Though Queer City does a good job of following queer history through the ages, Ackroyd fails to connect his cited historical examples with larger sociocultural movements of the time. He discusses queer coding in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales but not the larger (oft homoromantic/homoerotic) courtly love traditions that Chaucer drew on. He describes the cult followings around boy actors playing female parts in Elizabethan and Jacobian London but neglects to put those theaters and the public reaction to them within the context of the ongoing Renaissance. Similarly, Ackroyd omits explicit connections to the Enlightenment, Romanticism, Neoclassicism, free love, and countless other cultural movements that undoubtedly shaped both the social and legal responses to the queer community. This exclusion, unlike the exclusion of queer love, had to be intentional on Ackroyd’s part; it’s hugely unlikely that a historian with his bibliography accidentally forgot to mention the last millennium’s worth of Western civilization cultural movements. It’s a massive oversight that utterly fails to place London’s queer history within the context of wider history.

And finally, last but definitely not least, oh boy does Ackroyd have some learning to do when it comes to gender, gender presentation, and gender identity. From the very first chapter, it’s apparent that Ackroyd’s research and writing focused largely on MLM cisgender men, with WLW cisgender women as a far secondary priority. While there are chapters on chapters dedicated to detangling homosexual men’s dealings, homosexual women are often pushed to the fringes of London’s queer history. They receive paragraphs, here and there, and occasionally the closing sentence of a chapter, but overall they’re clearly downgraded to a secondary priority within Ackroyd’s historical narrative. Some of this can once again be blamed on the type of records Ackroyd uses; sex between women was never criminalized or discussed in the public sphere in the same way that sex between men was, so it was a less common topic in London’s courts and newspapers. (And, once again, I have the sneaking suspicion that turning to less traditional sources would’ve helped resolve this issue, though in part the omission can likely be pinned on Ackroyd’s demonstrable preference towards male history.)

Additionally, Ackroyd tends to treat crossdressing as undeniable proof of homosexuality. While it’s true that historically queer individuals found freedom or relief in dressing as the opposite sex, the latter didn’t necessarily equal the former. Additionally, if the crossdressing individual in question was female, dressing as a man was often a way for a woman to secure more freedoms than she would receive while wearing traditional feminine outfits. (Also, he tended to use “transvestite” over “crossdressing,” and while I tend to think of the latter as more preferred, the former may be more in use among queer studies circles or British slang). Though Ackroyd briefly acknowledges that women could and may have crossdressed to more easily navigate a misogynistic world, he nevertheless continually dredges out records of crossdressing women as concrete proof of historical sapphics.

Which brings us to the elephant in the room; in clearly identifying crossdressers as homosexuals, Ackroyd entirely overlooks the existence of transgender and nonbinary people in London’s historical record. This omission, arguably unlike the others, seems definitively intentional and malicious. In the entire book, I could probably count on one hand the number of times Ackroyd mentions the concept of gender identity, and I could use even fewer fingers for the number of times he does so respectfully and thoughtfully. Though he largely neglects to discuss transgender history as a subset of queer history, when he does bring up historical non-cisgender identities it’s often as a component of his salacious narratives rather than a vibrant and storied history all on its own. In the final chapter on modern gay London, Ackroyd’s casual dismissal of the concept of myriad gender identities felt dangerously close to modern day British “gender criticism,” which is likely more familiar to queer readers as TERFism masquerading under the guise of concern for women and gay rights (JK Rowling is a very public example of a textbook gender critical Brit, if you’re wondering). By the end of the book, Ackroyd’s skepticism of so-called “nontraditional gender identities” is so glaringly evident that he might as well proclaim it outright.

The verdict: For a book supposedly focused on queerness, the focus on male cisgender homosexuality is both disappointing and honestly not surprising. This book is a portrait of gay London, yes--but it’s also a portrait of Peter Ackroyd as a historian and a professional. It’s clear from early on that he’s writing from the perspective of an older white gay man (I think queer WOC know what I’m talking about when I say that that POV is very distinct, and his clear idolation of 1960s-1980s gay culture makes his age quite evident as well). As you progress through the book, his blindspot in regards to gender and gender politics become increasingly clear, as does his simultaneous obsession and criticism with transgender identities. Overall, Queer City is a clear example of how “nonfiction” doesn’t necessarily mean unvarnished truth--or at least not all of it--and how individual historian’s methods and biases bleed into their research.

A dear London friend suggested Matt Houlbrook’s Queer London: Perils and Pleasures of the Sexual Metropolis as a more gender inclusive review of the famous city’s queer history. While I take a break from London for a bit, I would welcome any and all thoughts on either Queer City or Queer London, the latter which I fully intend to get to eventually so I can properly compare the two.

#book review#queer history#queer city#text heavy tw#sex mention tw#long post for tw#wow this got really long sorrt#kinda starts rambling by the end oops

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi im a history major and enjoyed reading your essay 'an atypical affair'. I wish there were more essays that covered queer things in the widest sense in this professional manner. so I was wondering if you know of similar (but maybe also newer) sources or essays about homo erotism from antiquity (macedonia, persia, greece, egypt, everything mesopotamia geographically speaking), especially sth where there are conclusions possible about the everyday life or laws concerning that? thanks a lot (:

Greek homoeroticism (a term I prefer to “homosexuality,” which is modern) had it’s heyday from about 1978 (publication of Kenneth J. Dover’s seminal Greek Homosexuality) through the first decade of the 21st century, and there was a veritable explosion in the 1990s and 20-aughts, in particular. Some key books included John J. Winkler’s The Constraints of Desire—still my personal favorite treatment!—and David M. Halperin’s A Hundred Years of Homosexuality, as well as Before Sexuality, which he edited with Froma Zeitlin and Jack (John J.) Winkler, etc., plus a veritable landslide of articles (mine among them, along with one by Daniel Ogden, Mark Golden, Thomas Hubbard, and a few others whose names are escaping me).

In the last decade, that’s slowed, as the topic has been picked over pretty thoroughly, and it’s largely text- and art-history-based. So without new evidence, it’s getting harder to have much new to say. Plus, the lines of camps are pretty well drawn by now. Also, while I’m familiar with bibliography for Greece, I’m far less so for Rome.

For further reading, I’d direct you to the bibliography in my article, “An Atypical Affair: Alexander the Great, Hephaistion Amyntoros, and the Nature of Their Relationship.” (I know you’ve already got it, but putting in a link for anybody else reading this who doesn’t.) Plumbing bibliography is the Number One Rule for all history students, grads and undergrads, both. Again, you may well already know that, but I mention it, in case not. I regularly get even grad students in our Ancient Mediterranean Studies Program who forget to look at bibliographies for further resources.

Yet as my article came out in 1999, there’s some late ‘90s/2000+ era material that just isn’t in it. Remember, any article appearing in print was probably written at least a year, and sometimes several years, before it appears, so the bibliography will reflect that time gap.

Ergo, here is some additional bibliography on homoeroticism in Greece (and Rome) appearing since my article. First, I list Blackwell’s Companion, even though it’s recent, as it’s a good overview of all angles of current (well, early 2010s) research, PLUS BIBLIOGRAPHY, for each chapter. Following that are a short list of books, more or less in publication order. These are books, so I offer the usual caution…a lot of the cutting-edge research in ancient history (until quite recently) tends to appear in ARTICLE form first. So, again, plumb the bibliographies of these books for other important and salient articles.

Thomas K. Hubbard, ed. (Blackwell’s) Companion to Greek and Roman Sexualities (Yes, Hubbard is a deeply problematic figure, but his books can’t be left off; especially the sourcebook and the collection.)

James N. Davidson, Courtesans and Fishcakes: the Consuming Passions of Classical Athens

Thomas K. Hubbard, Homosexuality in Greece and Rome, a Sourcebook of Basic documents

James N. Davidson, The Greeks and Greek Love: a Bold New Exploration of the Ancient World (I prefer his original Courtesans & Fishcakes, actually.)

Marilyn B. Skinner, Sexuality in Greek and Roman Culture, 2nd ed.

Martha Nussbaum & Juha Sihvola, The Sleep of Reason: erotic experience and sexual ethics in ancient Greece and Rome (collection of essays)

Daniel Ogden, Alexander the Great: Myth, Genesis, and Sexuality (We agree on a lot, but disagree on some significant things.)

Sandra Boehringer, Female Homosexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome.

Ken Moore, ed. Routledge Companion to the Reception of Ancient Greek and Roman Gender and Sexuality.

#Greek Homoeroticism historiographic essay#Classics#Greek homoeroticism#Greek homosexuality#Homosexuality in the classical world#Homosexuality in ancient Greece#Homosexuality in Ancient Rome#Alexander the Great#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#tagamemnon#asks

117 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alfredo Guttero

Who: Alfredo Guttero

What: Artist and Art Promoter

Where: Argentinian (active in Argentina and throughout Western Europe)

When: May 26, 1882 - December 1, 1932

(Image Description: Retrato del pintor, Victorica, 1929 [a self portrait]. It shows Guttero in his apartment. Outside is a very geometric skyline of smokestacks, steep roofs, and a brown sky. His room is slate colored and he sits in a chair in the foreground. He has a jacket thrown over the back of his chair. His pose is casual and he looks as if we [the viewer] have just distracted him from painting. He sits with his legs to one side, turned almost unnaturally toward the viewer. One leg is lifted slightly and one hand is on the chair's seat as if he is in the middle of turning completely to the viewer. He is a man with a receding hairline and a high forehead. He has a dark mustache and dark hair and low eyebrows. He is wearing a white shirt and bowtie and has his sleeves rolled up to the elbow and his collar is ruffled and loosened. The whole thing hangs very loose but you can still see some of his body's lines of musculature. His tie undone and hanging around his neck. His pants are ordinary and green/brown. His expression is calm but confident and he looks directly at the viewer. The colors are bold but not really bright. The style blends geometry and flatness and realism in a way I am explaining very poorly. End ID)

Guttero is not terribly well remembered today, which is too bad. Looking through his oeuvre I quite like his work. Maybe it is because he lacked the bombastic personality of many modernist artists, maybe it is due to his diversity of styles without one that seems to define his work, or maybe it is because he was one of so many talented artists of his generation. He was well renown in his era, however, and used his popularity and skill to foster the next generation of Argentinian artists.

Guttero's life began mundanely enough. He always loved art, appreciating it and creating it, but pursued a legal career instead. But he was unhappy with his life as a lawyer, so Guttero left it to become a painter. He pursued his dream and passion, inspired and pushed by other Argentine artists. In 1904 his reputation was good enough that the Argentinian government sponsored his move to Paris, then the epicenter of the truly exciting and revolutionary art world, its influence expanding outward. He studied there for a few years under Maurice Denis before appearing in the Salon.

He remained in Paris until 1916 when he began to travel extensively across Western Europe for more than a decade, first to Spain, then Germany, Austria, and beyond. He traveled to nearly every country in the area between the years of 1916 and 1927. His work was shown in various exhibitions around the continent from being featured in the Salon in Paris to a major solo exhibition in Genoa.

After that he returned to Argentina for the first time since his initial departure in 1904. Guttero remained active in his native country including creating free art classes called, aptly enough, Cursos Libres de Arte Plástico, with other Argentine artists. During this time he focused on his work as an art promotor, perhaps even more than his own art. During this time he introduced and showed new Argentinian artists to a wider audience. Indeed he created an organization for this purpose: the Hall of Modern Painters. He was dedicated to promoting and preserving modern art in the face of a world growing increasingly dark and reactionary. He died young and without much warning.

His art is undeniably modernist but trickier to pin to a specific movement. He has many different styles he utilizes with different degrees of naturalism and curves vs geometry. His scenes are by and large mundane and human, he uses bright colors, often huge central subjects, kinetic poses and positions, modern settings, and by and large human or urban subjects. He often painted on plaster using a "cooked plaster" technique of his own devising.

(Image Description: Martigues for Charles Jacques [1909], a brightly colored painting showing a scene in a Martigues canal. It is not completely realistic nor completely geometric and abstract. He favors color over outlines. In the background is a bright blue sky interrupted by yellow buildings with tile roofs, maybe houses, lit by the unseen sun. One of the building's lower doors is open. There is a small tree to the far right. In the foreground in the sparkling water of the canal are several small work boats, probably fishing boats judging by the silvery nets lying over the hulls. On the right a boat is coming in, there is a pale skinned, dark haired man working on one of the nets. His sail is red and white. On the left is a pale man in an orange hat and yellow shirt. He is stooped and just by his pose appears older, both of the men are too far away for many identifying details. End ID)

Possible Orientation: Mspec ace, gay ace, or aroace with an aesthetic attraction to multiple genders. (I am so unsure I have changed "probable" to "possible.")

I admit this one is a stretch on my part.

I am classifying Guttero based largely on absence, i.e. the absence of a remembered/recorded spouse, sexual/romantic partner, or liasian. I have no quotes or historical documents to prove my point. I have none of his personal philosophy or writings to draw from. Just the fact that he dedicated his life to art more than human relationshipa. That this is something I have seen before: Cause and its role in the life of many aros/aces/aroaces (outlined in Weil's entry the other day) and the fact that he had no recorded romantic/sexual partners that I can find in hours of research.

This illustrates why it is so, so difficult to find aspecs in history. We are not, as aphobes believe, impossible to locate, there is externally visible evidence, but it is less obvious than most other orientations. And cishets would rather we didn't exist so we are often buried under excuses. The easiest ways to find them are 1) if they were notably "married to their job" in their lifetimes (e.g. Jeanette Rankin and Carter Woodson), they talked/wrote about it in some capacity (e.g. T.E. Lawrence or Frédéric Chopin), they were distrusted because of it (John Ruskin and James Barrie), they made it part of their persona (Nikola Tesla and Florence Nightingale), aside from that I really need to search deep into their personal lives. Information not always available.

And often even when people essentially say "I am aromantic and/or asexual" the general population will not accept that. After all Newton is often remembered as allo and gay, despite never expressing interest in men. Chopin is often listed as allo and bi. Rankin is often considered cishet but too deeply concerned with her work. Barrie gets called a pedophile despite showing no interest in children. For eccentric aspecs like Weil/Tesla/etc. their being aspec becomes part of their oddness. If they weren't Like That they would be allo. Their being aspec becomes a symptom of their weirdness and would be unacceptable in a "normal" person.

History with a capital H does not want to acknowledge aspecs and, as with other queer identities, will go to insane measures to erase them. But even other queer historians will do this to aspecs. I am shocked how many people do exactly to Newton/Lewis/and the like what cishet historians do to Alexander the Great. In the case of Alexander the cishets ignore the obvious accounts that he loved Hephestian in nearly every way possible and queer historians and history buffs call them out, then often the non-aspec ones look at Newton and Lewis who had no interest in men and say they must have been gay. And it isn't really just history, Tim Gunn is by his own admission both gay and ace and the second part of that statement is either erased or, even crazier, I have seen aphobes say that he is mistaken about his own identity.

Anyway the root cause of this lack of nuance in the discussion of sexual orientation is a long sidebar that this is not the place to explore. I have left Guttero behind paragraphs ago. I have written a lot about how aces and aros end up getting erased from history and this isn't about that.

This is about Guttero and the difficulty of finding aros and aces. The presence of something is so much easier to find than the alternative, obviously, like if Historical Figure X exclusively slept with/courted men and was a man we can say he was (most likely) gay. But if Historical Figure Y didn't sleep with anyone/court anyone it is harder to prove. This is obviously severely simplifying identity but for the purposes of this example I beg your apology.

Long Story Short: the absence of evidence of something is not proof of the absence of something. A lot of aphobes will point this out and utterly ignore the fact that sometimes it is.

So, Guttero. The only thing I can say conclusively is that he never married and he was romantically or sexually tied to anyone as far as I can find. He was, in his time, very active in the art world. If he had been involved someone would probably have taken note. Especially considering his art is often very appreciative of the human form, especially the male one, it would not be hard to believe he was allo and gay or mspec.

I am going to take his art another way putting some dusty analysis/critique/art history skills to good use. Here's the thing, those who follow me on my personal blog or even here know I find the Death of the Author extremely important but it is also extremely complicated (it was actually the topic of my senior thesis). I don't want to use an artist's work to talk about their personal lives because art is often not reflective of life, but there is always some cross contamination in one way or another. I am going to explain what I mean on a superficial level, using myself as an example so I can say this is 100% accurate. I love the found family trope, and I think those relationships are the best in the world. So whenever I write something you can be damned sure if I can get some found family goodness in there I will. What I am saying is, I don't love or even approve of everything I write about, but I do write about some things because I love them and want to explore them and experience them on some level. The same may be true for Guttero and the subjects he painted.

Guttero often pays a lot of attention to human form. Look at his work The Market (I couldn't find a large enough image to put it in this post) and you will see his appreciation for amab musculature and on the other side of the male spectrum...

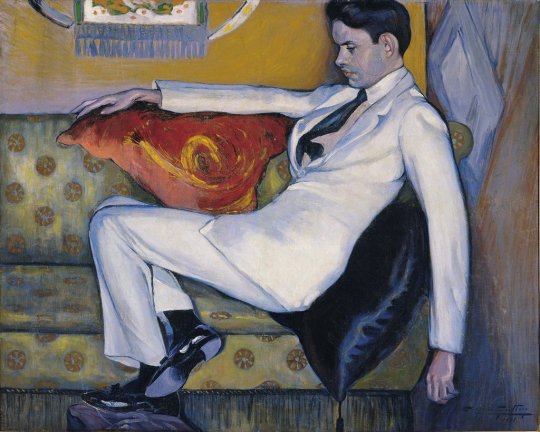

(image description: Retrato de Lucien Cavarry [1911] It shows a thin, lanky, and well dressed young man reclining on a green floral patterned couch and a black pillow. He is pale with neat, dark hair. He has a shadow of 5 o'clock shadow on his super hero jaw. His suit is white, his slightly rumpled tie is black, as are his socks and polished shoes. One arm is across the back of the couch and a red and gold pillow the other is dangling. This style is very different from the other portraits I showed/referenced. Still a modern but more realistic style, more flowing, less geometric. The man is drop dead gorgeous by Western beauty standards. End ID)

As for women...he seems to find them colder, more distant, but there is still a physical appreciation there. (Linking Mujeres Indolentes so I don't get flagged for "female presenting nipples" or whatever Tumblr's BS is. [The name alone tells you a lot]). Or the somewhat judgemental gaze of the woman below:

(Image Description: Georgelina. It shows a portrait of a pretty young woman sitting in front of a field. She is pale and long and beautiful. She has red hair, sharp eyes, a long flowing white dress with a gold sash around her waist, and a white hat with a black bow that is blowing in the wind. She takes up most of the frame and her expression is challenging and she holds eye contact with the viewer. The colors are bright and she is almost porciline in color. The background is mostly flat planes of color. In style it is somewhere between the self portrait and the portrait of Cavarry. End ID.)

Not all of his portraits of women have them so sour/distant but they all have a sort of challenging look. Beauty tinged with something dangerous, while the men always seem more innocent.

So here is why I say aspec rather than allo using his work alone, none of his work is particularly sexually inviting even with the sexiness/physical European attractiveness. The men are bashful or unaware of the viewer, the women are certainly not interested.

And back to the self portrait at the top: Guttero is in a fairly sexy pose, but it is sexy without being sexual. He is rumpled but the thing he was doing was painting, there is a sexless explanation. He is looking at the viewer, but you are distracting him from working. At first glance I thought his legs were spread, but they are simply in motion so he can face his guest more comfortably. This all could mean nothing, but I found it striking that this is how he chose to depict himself, at first he appears to be inviting the viewer in for a more physical interaction, but then it seems he is doing exactly the opposite, his passionate energy has been instead put into painting.

And in reality toward the end of his life that was what he did. He dedicated himself to his own art and the art of others.

So again, this could mean nothing. But...it could mean he is aspec.

And that is how the person I am least sure about got the longest entry.

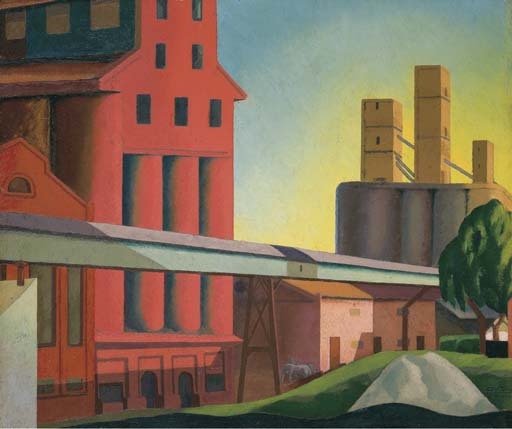

(image description: Elevadores [1928]. A painting showing a factory complex. There is a raised platform running around it and several buildings in bright colors. There is a tree to the right side and a green hill. The building in the near-center [lightly left] is red. The sky is yellow and blue, perhaps the unseen sun is rising up behind the right-hand buildings. In style it is mostly geometric and flat color. End ID.)

#queer#lgbtq#asexual#ace#history#aromantic#aro#gay#mspec#20th century#artists#south america#Argentina#Argentinian#Alfredo Guttero

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE GENIUS AND HIS BETTER HALF

This sharp and witty revival of Mart Crowley’s 1968 hit is a winsome window to the past that entertainingly evidences how much, and how little, things have moved on for gay men in the last almost-half-a-century.

Originally produced one year before the Stonewall riots, and predating the horror of the AIDS crisis yet to come, The Boys In The Band is a snapshot of queer history that laid down the foundations for so much LGBT theatre that was to follow. Set over one evening, the piece explores the lives and loves of eight gay men – plus one ‘straight’ interloper – as they celebrate a birthday with a house party that descends into an alcohol fuelled game of dangerous dares.

This faithful recreation is a glittering triumph, carried out with consummate craft by an enviably well-assembled ensemble, led by Ian Hallard and Mark Gatiss. As Harold, the birthday boy, Gatiss gives us a graceful grotesque – in the character’s own words: “A thirty-two year old, ugly, pock-marked, jew fairy.” Simmering with self-loathing and liberally ‘throwing shade’, this is sumptuous stagecraft that pierces any potential pomposity with scathing scrutiny and an acid tongue. A scene-stealing success.

Hallard, as Michael – our host for the evening – has the bulk of the narrative to carry here, and does so with aplomb. His transition from cheerful chappie to inexorable inebriate as events play out and drinks are downed is subtle and skilful – making it difficult to spot the exact moment at which he shrugs off social convention and launches into attack mode, all guns blazing. A deft depiction of depression with which Hallard seriously impresses – sensitively sensational.

The remainder of the all-star cast each bring something particular to the party. James Holmes is magnificently memorable as Emory – demonstrating a mastery of mincing that ought to earn him an award for outstanding command of campery. Nathan Nolan and Ben Mansfield, as Hank and Larry, have an engaging narrative of their own threaded throughout the piece – horn-locked lovers unable to agree on the status of their relationship. Theirs is a tale that echoes through the ages and one that’s resolved here with visceral verisimilitude.

John Hopkins has an unusual challenge, in that his part of Alan is the only one that’s possibly affected to any great degree by the fifty year gap between then and now. As the ostensibly heterosexual married gatecrasher, and old college friend of Michael, Alan is quite literally the ‘straight man’ in terms of plot function – an outsider excluded from the secret bond, and, in this production, a patsy for us to laugh at. We can’t help wondering though, if back in 1968, Alan was intended as more of an audience identification figure – to take Joe Public by the hand and lead them gently into an unfamiliar world of decadence and debauchery. Regardless, Hopkins’ interpretation here succeeds completely, and is enhanced by a pleasingly puzzlingly ambiguity that leaves us all guessing.

A special mention has to go to Jack Derges as the young hooker, so objectified and fetishised that he doesn’t get a name beyond Cowboy. Derges blows us away with a character that was surely the inspiration for the phrase ‘young, dumb, and full of cum’. Gift-wrapped and tagged, his rippling physique and endlessly endearing missing-of-the-point is a joy from beginning to end. Adorable.

Set and costume are detailed and precise – nailing the period with precision. And of particular note is lighting by Jack Weir – subtly shifting focus without shouting from the rooftops. A ‘light touch’ that’s bold with understatement.

While partially an historical document, this production is so bursting with life that it feels as fresh and relevant as ever. Add some technology, remove some period racism, and this could be taking place right now. Great leaps have been made, legally and socially, but what’s so well demonstrated here is that *we’ve* always known who we are and what we want, despite having to wait for the rest of society to play catch-up. Heartfelt and hilarious – unmissable!

GT gives The Boys in the Band — 5/5

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Remarks about my writing Grell as Jewish

Firstly, I am not Jewish.

I’m not Christian either, and in fact am Muslim. So I understand the feeling of belonging to a marginalized faith, and underrepresented or misrepresented faith, a demonized faith, probably a lot better than most Western Christians would, and so I come with that background. I also know many people of the Jewish faith, religious and non-religious.

But I am not Jewish. Nor do I claim to understand at all the Jewish experience.

So why would I dare headcanon a London serial killer as Jewish? Let me explain--

Firstly, I not only warn you, but ask for forgiveness, in making my decision solely based upon analytical patterns and tropes of Jewish characters throughout history, without at all considering the ramifications of enforcing stereotypes, of demonizing a people. I ask for forgiveness for originally using the faith as a plaything for dress-up for my little shitty fanfiction, entirely forgetting that Judaism is not only a very real and very deep faith, but that antisemitism is still alive and well.

So here goes my original decision making process--

I had been reading up a lot on Jack the Ripper’s history, mainly because I wished to start my own project involving the subject matter, and had found some interesting bouts of historical antisemitism throughout. Forgive my naivety, but they don’t really teach this sorta shit in American schools, the fact that antisemitism originated and existed before the Holocaust. I was dimly aware, having toured many European nations and recalling remarks that tour guides made about certain architectural choices due to historical antisemitism, and having read one book by accident that was a series of monologues from documented middle-ages life stories, several of the monologues dealing with historical antisemitism. But somehow it never all came together than in 19th century London, anti-Jewish attitudes were a thing, until I researched, and I became fascinated by this strange stereotype--that Jack the Ripper must have been Jewish because only Jews could be capable of such savagery. It was weird to me, never having considered Jewish persons to be anything outside of heavily involved in musical theater, and it reminded me of the stereotypes facing my own people, Muslims, of us being bombers and rapists capable of savagery.

And knowing that the name “Grell” was a German name, it got me wondering--a German Jew?

It was a smaller headcanon of mine, where I somehow kept going “ah yay, representation!” in my head without understanding the ramifications of negative representation.

But it only ran deeper when I was introduced to Judaism in Shakespeare and other English literature. I learned of Shakespeare’s Shylock, of Dickens’s Fagin, their wickedness in English society. Thieving, maniacal, malevolent, melodramatic, and--Jewish?

I couldn’t help but be brought back to cartoons I had seen of my own people, with big white turbans and big, thick beards, holding guns with dumb looks on their faces as they held goats in their arms and addressed them as “wives”. I thought of Ahmed the Dead Terrorist, of The Dictator, of Tintin and the Land of Black Gold, of Homeland, of American Sniper, of Raiders of the Lost Ark, of Call of Duty, and couldn’t help but wonder if Grell had been handled by a Victorian English author, would he have been coded as Jewish?

What really was the kicker was this article, this article, and this article, that made me adopt wholeheartedly the idea that Grell, in a Victorian-English context, would have been coded and Jewish, as there have been depictions or written remarks throughout all of history of Judas, David, and Esau having red hair. Due to this, in literature throughout history, red hair has been an identifier of malevolence, of hot-headedness, and of Jewishness. Both Shylock and Fagin were often depicted with red hair, after all, Grell only doubly so.

So my conclusion, in the end, is that a case can be made for coding Grell as Jewish--

Unfortunately, that is not the conclusion of this post...

Recall my earlier apology?

In my research and soul-searching of Jewish stereotypes, relating them to the Muslim stereotypes I know so well--I had forgotten about how much those stereotypes hurt. Perhaps it is the Muslims who are now being depicted as big-nosed and hairy, rather than the Jews, but it wasn’t too long ago that the Jews were where my people are today. Not only was it not that long ago, but even the slaughter of my people is under the guise that these are “Islamic terrorists”-- “terrorist” being the keyword that defends Islamophobes, making the rape of the Muslim world seem justified. Jews weren’t even afforded this title of “terrorist” or anything of the like, the word “Jew” alone being bad enough as far as I am aware.

So now I must finish my apology--I am sorry for neglecting the fact that writing a serial killer known for his savagery and brutality as Jewish, especially a serial killer from a time period where such traits were ascribed the Jews, is highly offensive and misrepresentative of the Jewish community. It’s as bad as the stereotype of the brown, grinning, sooty-eyed, fang-toothed Arab Muslim sheikh, leering over young maidens as he puffs on a thick cigar bought with blood money. It’s as bad as the black as night, absurdly strong savage warrior, who dons a loincloth of leopard print and prowls the land as some half-human, half-animal hybrid. It’s as bad as the thick-lensed, creepy, mathematically inclined Asian who speaks in a high, effeminate stutter and masturbates to animated women.

But I am not taking down the headcanon--and here is why.

I wish instead to make Judaism less a cause of his savagery and cunning, and more a simple trait. Grell Sutcliff is the savage Jack the Ripper, but is also the brilliant engineer, the talented singer, the queer, and the born and raised Jew.

I choose instead of reinforcing Jewish stereotypes, to research and respects customs and cultural traditions, and to use faith as moments of the split from savage animal to a ponderous human, who recalls the hymns his mother sang to him--Hine Ma Tov and Oseh Shalom--in moments when he almost reaches humanity. For psychopathy is not raised in a vacuum, and religion is not taught only to the righteous. Grell will never be excused of his actions nor his perverse worldview, but a human being, even a psychopath is not simply made up of their perversions. There are multiple facets to each human being.

I know it’s hard to swallow, that serial killers are indeed human, even if their actions and perversions are not deserving of such a distinction. There is no humanity in their actions, as they are unimaginably cruel, but they were born from a mother and father, sometimes even raised by said mother and father or other guardians, they had a childhood and a life, perhaps even a faith. And that is what I wish to explore with Grell...

That is what compelled me to Grell’s story in the first place--that he is an awful, terrible, cruel person, but is (or was) certainly a person--a person who does not confine to the social norms of the da. Grell may be a horrendous person, but Grell is also written as a marginalized person. The following information is canon after all:

Grell is a person of the LGBT community, a community that was shamed, disgraced, and even killed by the law itself, as it had maimed and killed notable English minds such as Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing.

Grell suffered mental health illnesses (conditions that were not only overlooked in the era but even cause for brutal, violent force and abuse), that led him to suicide.

Grell’s actions are inexcusable, but Grell himself is complicated, full of such richness (that Yana Toboso unfortunately did not exploit thus far) and story that is so often ignored in Victorian English history. Thus I wish to write him for another seldom talked about group, the English Jews and Jewish immigrants, as I have evidence to back up my claim. And I feel that I can wholeheartedly relate to the feeling of being a demonized minority in a majority nation as an American, immigrant Muslim.

****NOTE: The precocious among you may remark that the name “Sutcliff” is not a Jewish name, hence why I must remark here that I also headcanon him as biracial, having a Jewish mother and an English father. Unfortunately, it did not come up in the post, but the remark still stands.

#tw: judaism#tw: religion#tw: goyim#tw: gentiles#tw: antisemitism#tw: holocaust#tw: long post#please read to the end before arguing with me#it's nebulous and meandering but trust me on this

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Plumbing Tree by Medium Judith

Sylvan Oswald on The Plumbing Tree

The queer family has a gas leak. A character named Miasma, the voice of the gas itself, narrates its encroaching occupation of what might be an ordinary household. But for Medium Judith, the collaborative experimental theater “host” entity of Amanda Horowitz and Bully Fae Collins, this oddball clan is under siege from within. This is the exhausted American Family Play as civic debacle – the kind in which poisoned water contaminates entire towns, and even air in some public housing is not safe to breathe. The queer theater of Medium Judith, posits that the family play itself may be unfit for consumption.

Polarized politics play out among the queer spawn of Celetta (Flannery Silva) in her pregnant-Orthodox-Jewish-matriarch drag. When the gender nonconforming Yves (Christiane Oyen) proposes a “dragabond” flag with “Islamic aesthetics” for the front lawn, his* sister Jodi, an androgynous nationalist in a pilgrim outfit (the subversively charming Julia Yerger), worries what the neighbors will think. As the argument ensues, the Homer Simpson-eque subletter Lars (Arne Gjelten) and neighbor Augustine (Elizabeth Sonenberg) weigh in. Jodi’s riposte is a shrine to female military veterans decoupaged onto a huge yellow ribbon. Yves fires back, planting his flag with such vigor that a pipe bursts, spewing septic ooze and vapors that put the family in a trance. “A character is best played in a less than conscious state,” intones Miasma as the existential front lawn drips with Shit. The Plumbing Tree is not just a battle over national/personal domestic politics, but over the soul of the well-made-play.

The latter may appear to be of less pressing urgency given our moment in history. However, the American Family Play has often functioned as a referendum on national shame. Whether the revelation is fraud, addiction, abuse, or beyond, our post-Freud playwrights have built structures that reveal the repressed. We can trace this from the likes of Arthur Miller and Lorraine Hansberry through newer plays like Paula Vogel’s And Baby Makes Seven (1993), Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins’s Appropriate (2013), Taylor Mac’s Hir (2014), and Jackie Sibblies-Drury’s Fairview (2018) (and many more – it’s a vast genre).

The Plumbing Tree critiques blind spots within the queer community, such as thinking of ourselves as part of “the solution,” to what ails society. If “perfection is for assholes,” as Taylor Mac says, then with our glorious deviance we hold a space of inclusion, acceptance, and process-as-constant. These are values queer folks ostensibly represent. Yet, Queer is no monolith. We cannot ignore that the white supremacy and institutional oppression that exist in society-at-large exist within our own communities – and our own non-profits as well. It’s all too easy to police the boundaries of otherness.

As the queer family onstage crawls over each other, out of their minds from Miasma’s attack, I saw one lost world inside another. But it didn’t feel like nostalgia. Medium Judith’s The Plumbing Tree ends with a rousing punk number. The cast wrinkles their noses, “and smells the audience as if they smell like shit.” We’re full of it. And it’s time to look it in the face.

*Medium Judith has informed me that the character Yves uses male pronouns while exploring transfemininity but does not yet formally identify that way.

Sylvan Oswald is an interdisciplinary artist who makes plays, texts, publications, and video. He is an Assistant Professor of Playwriting at UCLA’s School of Theater, Film & Television.

Fiona Duncan on The Plumbing Tree

I suffer from claustrophobia in elevators, relationships, discourse, and media. The first act of The Plumbing Tree had right wing vlogging, trans and queer worship, uncouth men as the butt of jokes—hyper contemporary hot topics in the U.S. I was raised in Canada, and in the last 3 years, have come to appreciate how subtly different our nations are, as I witness my age and same ideals proclaiming peers here, in the States, mostly incapable so far, in their shares at least, of imagining true collective difference; their politics tend to be reactionary in content and form (loud, advertorial me meme forms), which is fair-ish re: content (the powers that be are powerful and awful! it's hard out here). But, what if: she who opposes force with counterforce reinforces that which she opposes and is formed by it. Anyway, I was happy when The Plumbing Tree devolved into collective shit, figuratively and figurally. Sewage burst from below the set of the house, like colonial, industrial, and patriarchal history is beyond haunting us now. The stage was brown and mucky and its character all got puke and mad sick from a stink indifferent to their differing identities and ideals.

I refuse to talk about shit with most anyone. I don’t find poo jokes funny. You should leave the room if you’re going to fart. It’s my one prudery; notorious, friends make fun of me for it. And yet I loved The Plumbing Tree’s shit brown metaphor and set, something about it not being just my shit, or your shit, or their shit, but so much shit, a world of shit, made it less cringeworthy, embarrassing, disgusting. This shit was even, refreshing.

Fiona Alison Duncan is an LA-based Can-American writer, bookseller, and organizer. She is the organizing host of Hard to Read, a monthly lit series, and Pillow Talk, community organizing on sex, love, and communication.

Brian Getnick on The Plumbing Tree

For the last year and a half I’ve watched Amanda and Bully’s The Plumbing Tree grow at PAM, from an installation of sculptures and diagrams in the stairwell to public readings of the script and workshop productions of the play. At its recent debut at Highways Performance Space, The Plumbing Tree has blossomed and grown some very bitter fruit.

At Highways, the stage was littered with abstract brown assemblages, a quilted flag and an enormous yellow ribbon adorned with regiments of proud female soldiers. These objects are sculptures that pose as props. They don’t sit meekly in service of the plays narrative; their surfaces are worked with detailed, micro narratives of their own. And, because their material processes are explicit, they also function as psychological prosthetics of the characters that made them. The flag is meticulously quilted by non binary-artist Yves, the soldier ladies are crudely rendered in local color by Jodi, the neocon daughter.

I understood the cartoonishly frenzied energy of the performers as a way to grapple with the fact that the characters they played are more or less composites of ideological signs and symbols that Amanda and Bully have poetically strung together as a script. If one mistakes their competitions, attacks, and craft making with the complexity and paradoxical nature of being it is because we, in our daily rhythmic interface with social media, resemble them.

For instance, the mother, Celetta, wants only the signs and none of the burdens of motherhood: an engorged but hollow belly. Her children appeal to her dreamily as floating potentialities of her creative powers. Celetta: “I saw my children before they were born and they were smoke. And they could be anything.” Celetta resents that her actual children have abandoned their post inside the belly and are beside her warring for attention. In Act III, she pantomimes the agonies of birth to regain it.

When the language in The Plumbing Tree makes a shift away from parody and into a nearly autonomous materiality the characters release word torrents reminiscent of Asher Hartman and Reza Abdoh. This became most evident in the character Jodi, the Pilgrim hatted conservative. The polemics she espouses read like an Antifa passion play. Jodi: “Knock knock, who’s there?, Socialism, Socialism who? Socialism is a failed a system Shame on you America!” Then: “Fuck your faggot prophets. Here my hate has stewed me through. Prosper porridge, pungent forest sow and owl fertilize. Taste my musket, piggy squalor, measles mumps disease deceased repeat repent release your lands and logs in rolling throngs.” The language invites ecstatic interpretation, a song, a scream. It bursts through a parody of conservative rants and goes down, flung from Jodi’s mouth, into a witch’s cauldron.

In the third act, the performers crawl, they attack, they sing and dance, they blow a cluster of rape whistles and begin a chant. I remembered this line: “An object named is a fish out of water” It seemed to point to what the authors want and don’t want from writing for theater. I spoke with Amanda about this sentence and her answer was (I paraphrase here): that to name a thing is to isolate it from the force that gives the thing movement, agency, breath, and life. But these artists don’t write in a breath of fresh air; it’s a gamey fart that erupts when a flag is staked in the yard breaking open a subterranean sewer. At this rupture, the voice of the fumes bellows forth and the inhabitants that have piled out of the house indulge in a collective hallucination. The shit smell is named Miasma: all powerful language unleashed from the body.

Brian Getnick is an artist, curator and writer about contemporary performance in Los Angeles. He is the director of PAM Residencies, a showcase and residency program for performers making long form work (30+ minutes). He is the founder and co-director with Tanya Rubbak of Native Strategies, a journal documenting performance art in LA since 2011.

The Plumbing Tree happened at Highways on October 19 and 20, 2018.

Medium Judith is a host for an interdisciplinary methodology for writing experimental theater works. The company originated in 2012 in Baltimore, MD with works composed by Bully Fae Collins and Amanda Horowitz.

Video stills by Pete Ohs.

0 notes

Text

Misogynoir trolling on the socials: When men have fun saying crappy things about Black women.

It’s obvious how amazing it is to see women become great people who go on to do equally great things. Socially, it’s not hard to tell that we’ve always been expected to take and accept the back end of, well, everything. While this is true of women in the general sense, I can’t help but throw my focus towards black women, in particular. Being part of a gender that comes from a strong and painful history of incidents including racism and sexism like slavery and Apartheid, it’s not hard to say; we’ve been through a lot. Maybe a little bit too much, if we’re honest.

However, as the digital age becomes the home of our thoughts, opinions and influences, it seems the vortex of racism and sexism endured by Black women from men deepens and reaches unimaginable masses by the minute. As the successful Black women becomes the Beyonce (in the “I’m obviously the best and most influential person in my group worthy of a solo career” sense) of her career, somehow the rise of the Internet troll is unearthed. So much so, that there had to be a special word created to categorise this version of online torment by men - mysoginoir.

Misogynoir is a phrase coined by Moya Boyer, a black queer Feminist, in order to encapsulate the intertwined presence of sexism and anti-Blackness ( Boom, 2015). This definition, broken down further, simply directs to racist and sexist comments and thoughts made by men of ANY race, towards Black women. Yes, Black men sitting at the back; ducking so you’re hopefully not included, you too.Even further, for anyone who may not have noticed, it does NOT include comments and thoughts made by non-Black women. This one’s specifically for the guys. These men often choose to continuously torment women online, to make them feel unsafe and unworthy.

Sometimes it is a group of men, other times it’s just one loser, who make it a point to try and push someone’s buttons to the unbearable extent of fear and restriction of freedom. Moreau defines the source of the word ‘troll’ as “an ugly, dirty, angry creature that lives in dark places, like caves or underneath bridges, waiting to snatch up anything that passed by for a quick meal.” (2017). That defines the workings of an Internet troll, as they mimic the behaviour of the mythical troll by twiddling their fingers while staring at their computer or cell phone screen, just waiting to cause trouble for people on the Internet.

On the socials, there have been plenty of examples where we’ve watched successful Black woman thrive through their milestones. Think Dr Ncumisa Jilata - South Africa’s youngest Black female neurosurgeon who received praise across platforms for her achievement. Or, think multi Grand slam winning tennis player Serena Williams, who just keeps dominating social media whenever she does what she does best. You could even throw in reality star turned rapper Cardi B, who won the Internet by becoming the first female rapper since Lauryn Hill to hold a #1 spot on the Billboard Hot 100. These ladies, among many other women of colour, have used their abilities and talents to make a name for themselves. While there are schools of individuals who appreciate and admire them on social media, we obviously have a troll waiting in the peripheries to completely ruin the jubilation. In this particular case, I’m going to discuss Leslie Jones’ frightening experiences with an Internet troll who was just so pressed about her being in the Ghost Busters movie (*eye rolls on three*).

When the trailer for Ghostbusters went live on March 3rd, 2016, to unveil an all-female reboot of the film. Let’s just say, the Internet’s misogynists were reeling with anger anyway. However, it is worthy to note that besides the leading cast being composed of women, Leslie was the only black woman with a lead role in the film. Popular alt-right ‘professional troll’ Milo Yiannopulous, who is unfortunately popular based on being the ultimate social media nightmare, was at the very depths of Leslie’s Internet trolling experience. When he targeted her on Twitter, it encouraged a flood of his followers to directly tweet her as well; tormenting the actress to the point of choosing to leave the social media platform entirely. According to Silman (2016) the wrath continued, with Leslie’s website being hacked and uploaded with naked photos of the actress, pictures of Harambe the gorilla, and evidence of her driver’s license and passport amongst other things. What had begun on Twitter began to spill over to her personal life while it remained a very public display of her privacy and selfhood on the digital space.

It is worthy to note that Milo is a right wing, white man. He identifies as gay (he married a black man, so revolutionary), which some people may argue excludes him from the heteronormative patriarchal dominance that men often use to their advantage. In this instance, however, it can be argued that despite his sexual orientation, his given identity and a slew of his comments and political positioning, allow him to have the appeal to target a black woman just to ruin her life for fun. Misogynoir - there it is. This case, apart from its racial connections, shows the role which male hegemony plays in the existence and comfort of women in the practical and digital space.

Vera-Gray (2017) explains that the documentation of men intruding on women’s space on social media in academic literature does not exist enough, which can almost distance men trolling women specifically from the reality, magnitude and presence of this phenomenon as a problem. What’s more, since the general concept of men trolling women online hardly gets acknowledge, it’s even more obvious that the trolling of Black women particularly is likely to fade into the background.

Bibliography:

Boom, K. (2015). 4 Tired Tropes That Perfectly Explain What Misogynoir Is - And How You Can Stop It. Everyday Feminism, Retrieved 31/10/2017 via the World Wide Web. https://everydayfeminism.com/2015/08/4-tired-tropes-misogynoir/

Moreau, E. (2017). What is a troll and Internet trolling? Lifewire, Retrieved 31/10/2017 via the World Wide Web. https://www.lifewire.com/what-is-internet-trolling-3485891

Silman, A. (2016). A Timeline of Leslie Jone’s Horrific Online Abuse. The Cut, Retrieved 31/10/2017 via the World Wide Web. https://www.thecut.com/2016/08/a-timeline-of-leslie-joness-horrific-online-abuse.html