#waria jakarta

Text

Tak Puas Dilayani Saat Kencan, Pemuda Aniaya Seorang Waria

Tak Puas Dilayani Saat Kencan, Pemuda Aniaya Seorang Waria

Tak Puas Dilayani Saat Kencan, Pemuda Aniaya Seorang Waria

Jakarta, Sumbarlivetv.com – Tak Puas dilayani saat kencan, pemuda aniaya seorang waria, pukulan bertubi-tubi diarahkan oleh seorang pria berinisial AA (24) ke wajah waria. AA merasa hasratnya tak terpuaskan padahal sudah merogoh kocek Rp 40 ribu.

Kanit Reskrim Polsek Cengkareng, AKP Arnold menjelaskan, kejadian bermula ketika pelaku…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Islam, heteronormativity, and lesbian lives in Indonesia

Selections from Heteronormativity, Passionate Aesthetics and Symbolic Subversion in Asia by Saskia Wieringa, 2015.

These passages discuss some general social developments related to sexuality and gender in Indonesia, and then describe stories from different (mostly lesbian) narrators. They also touch on the creation of a religious school for waria (trans women), and include two trans men narrators, one of whom talks about his struggle to get sex reassignment surgery in the 70s. I also included a story from a divorced woman whose sexuality was questioned when her husband complained that she couldn’t sexually please him. Accusations of lesbianism can be directed toward any woman as a method for managing her sexuality/gender and prodding her into compliance with expectations of sexual availability.

In spite of protests by religious right-wing leaders, Islam does not have a single source of its so-called 'Islamic tradition'. There are many different interpretations and, apart from the Quran, many sources are contested. Even the Quran has abundant interpretations. Feminist Muslim writers, such as Fatima Mernissi (1985), Riffat Hassan (1987), and Musdah Mulia (2004 and 2012), locate their interpretations in the primary source of Islam--the Quran. According to those readings, sexuality is seen in an affirmative, positive light, being generally described as a sign of God's mercy and generosity toward humanity, characterised by such valued qualities as tranquillity, love, and beauty. The California-based Muslim scholar Amina Wadud (1999) describes the jalal (masculine) and jamal (feminine) attributes of Allah as a manifestation of sacred unity. She maintains that Allah's jamal qualities are associated with beauty that, although originally evaluated as being at the same level as Allah's masculine qualities that are associated with majesty, have en subsumed in the 14 centuries since the Quran was revealed.

The Quran gives rise to multiple interpretations. Verse 30:21 is one of my favorites:

“And among Allah's signs is this. That Allah created for you spouses from among yourselves, that you may dwell in tranquillity whit them, and Allah has put love and mercy between your [hearts]: verily in that there are signs for those who reflect.”[2]

The verse is commonly used in marriage celebrations, and I also used it in my same-sex marriage ritual. It mentions the gender-neutral term 'spouse,' which leaves room for the interpretation that same-sex partners are included.

Indonesian waria (transwomen) derive hope from such texts. In 2008, Maryani, a well-respected waria, opened a pesantren (traditional Islamic religious school) for waria, named Al-Fatah, at her house in Yogyakarta. After her death in March 2014, it was temporarily closed, but fortunately soon reopened in nearby Kotagede. A sexual-rights activist, Shinta Ratri, opened her house to waria santri (santri are strict believers, linked to religious schools) so they could continue to receive religious education. At the official opening, Muslim scholar Abdul Muhaimin of the Faithful People Brotherhood Forum reminded the audience that, as everyone was made by God: "Everyone has the right to observe their religion in their own way...", and added: "I hoped the students here are strong, as they must face stigma in society."[3]

Prior to her death (after she had made the haj),[4] Maryani herself, a deeply-religious person, said: "Here we teach our friends to worship God. People who worship are seeking paradise, this is not limited to our sex or our clothing..."[5] So far, hers is the only waria pesantren in Indonesia, perhaps even globally, and may be due to the fact that Maryani was an exceptionally strong person who spoke at many human-rights meetings. In October 2010, I also interviewed her and was struck by her warm personality, courage, and clear views.

In spite of those progressive readings of the Quran, women's sexuality is interpreted in light of their servility to men in practice, and has been linked to men's honour rather than women's pleasure. Although marriage is not viewed as too sacred to be broken in Indonesia, it is regarded as a religious obligation by all. An unmarried woman over the age of 20 is considered to be a perawan tua ('old virgin'), and is confronted by a continuous barrage of questions as to when she will marry.

Muslim (and Christian) conservative leaders consider homosexuality to be a sin. Women in same-sex relations find themselves in a difficult corner, as exclusion from their religion is a heavy burden. Some simply pray at home, privately hoping that their God will forgive them and trusting in the compassion taught by their holy books. However, outside their private space, religious teachers and society at large denounce their lives as sinful and accuse them of having no religion.

Recent Indonesia legislation strengthens the conservative, heteronormative interpretations of Islam. Apart from the 2008 anti-pornography law (discussed below), a new health law was adopted that further tightened conservative Islam's grip on women's reproductive rights and marginalised non-heteronormative women. That 2009 health bill replaced the law of 1992, which had no chapter on reproductive health. The new law states that a healthy, reproductive, and sexual life may only be enjoyed with a 'lawful partner' and only without 'violating religious values'--which means that all of our narrators would be banned from enjoying healthy, sexual, and reproductive lives.[6]

Conservative statements are also made by women themselves; for example, members of the hard-line Islamic group Hizbut Tahrir, who not only want to restrict reproductive services (such as family planning) to lawfully-wedded heterosexual couples but also see population control as a 'weapon of the West' to weaken the country.[7] They propose to save Indonesia by the imposition of sharia laws. Hard-line Islamic interpretations are widely propagated and creep into the legal system, thus strengthening heteronormativity and further expelling non-normative others.

Yet strong feminist voices are also heard in Indonesia's Muslim circles. Even in a relation to one of the most controversial issues in Islam--homosexuality--a positive, feminist interpretation is possible. Indonesia's prominent feminist Muslim scholar, Siti Musdah Mulia, explains that homosexuality is a natural phenomenon as it was created by Allah, and thus allowed by Islam. The prohibition, however, is the work of fallible interpretations by religion scholars.[8] In her 2011 paper on sexual rights, Mulia bases herself on certain Indonesian traditions that honour transgender people, referring to bissu in south Sulawesi, and warok[9] in the reog dance form in Ponorogo. In those cases, transgender is linked to sacred powers and fertility. She stresses that the story of Lot, always cited as evidence of Quranic condemnation of homosexuality, is actually concerned with sexual violence--the people of Sodom were not the only ones faced with God's wrath, as the people of Gomorrah were also severely chastised even though there is no indication that they engaged in same-sex behaviour. Nor is there any hint of same-sex behaviour in relationship to Lot's poor wife, who was transformed into a pillar of salt. Mulia advances a humanistic interpretation of the Quran that stresses the principles of justice, equity, human dignity, love, and compassion (2011: 7). Her conclusion is that not Islam itself but rather its heterosexist and patriarchal interpretation leads to discrimination.

After the political liberalisation (Reformasi) of 1998, conservative religious groups (which had been banned at the height of the repressive New-Order regime) increased their influence. The dakwah ('spreading of Islam') movement, which grew from small Islamist usroh (cell, family) groups and aimed to turn Indonesia into a Muslim state, gathered momentum.[10] Islamist parties, such as the Partai Kesejahteraan Sosial (PKS), or Social Justice Party, gained wide popularity, although that was not translated into a large number of seats in the national parliament (Hefner 2012; Katjasungkana 2012). In the early Reformasi years, official discourse on women was based on women's rights, taking the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action as its guide, but recent discourse on an Islamic-family model--the so-called keluarga sakinah ('the happy family')--has become dominant in government circles (Wieringa 2015, forthcoming). The growing Islamist emphasis on a heteronormative family model, coupled with homophobia, is spreading in society. During KAN's [Kartini Asia Network for Gender and Women's Studies in Asia] September 2006 TOT [Training of Trainers] course in Jakarta, the following conversation was recorded:

“Farida: Religious teachers go on and on about homosexuality. They keep shouting that it is a very grave sin and that people will go straight to hell. My daughter is in the fifth form of primary school. She has a best friend and the two were inseparable. But the teachers managed to set them apart, as they were considered to be too close. The mother of my daughter's friend came to me crying; she was warned that she had to be careful with her child, or else she might get a daughter who was different. And now the new school regulations stress that a woman must wear the jilbab [headscarf].[11] This has put a lot of stress on tomboyish girls. They cannot wear the clothes they are comfortable with any more.

Zeinab: When we were taught fiqih [Islamic law], we never discussed homosexuality. When we studied the issue of zinah [adultery], one of our group asked: "But how about a woman committing zinah with another woman, or a man with another man?" Our teacher just shook is head and muttered that that was not a good thing. The only story we learnt was about the prophet Luth [Lot]. But when we went to study the hadith [Islamic oral law], we found the prophet had a very close friend, Abu Harairah, who never married, while all men were always showing off their wives. There were some indications that he might have had a male lover. Yet the prophet is not known to have warned him. So, while the mainstream interpretation of Islam is that they condemn homosexuality, there are also other traditions that seem to be more tolerant, even from the life of the prophet himself.”

The above fragment shows how fundamentalist practices creep into every nook and cranny of Indonesian people's lives--the growing suspicion toward tomboys, forcible separation of close school friends, and enforcement of Muslim dress codes. But we also see a counter-protest arising. At the TOT training course, the women activists realised that patriarchal interpretations of religion had severely undermined women's space, and started looking for alternative interpretations, such as the story of the prophet's unmarried friend.

However, for many of our narrators, religion is a troubling issue. Putri, for instance, does not even want to discuss the rights of gays and lesbians in Indonesia; she thinks the future looks gloomy, with religious fundamentalism on the rise, and her dream of equal rights is buried by the increasing militancy of religious fanatics. [...]

Women-loving women

Religion is a sensitive aspect of the lives of our women-loving-women narrators, who are from world religions that, although propagating love and compassion in their distinct ways, interpret same-sex love negatively. In some cases, our narrators are able to look beyond the patriarchal interpretations of their religions, which preach hatred for what are emotions of great beauty and satisfaction to them, while others are devastated by guilt and shame. [...]

Indonesian male-identified Lee wonders why "people cannot see us as God's creatures?" but fears that Islam will never accept homosexuality. He knows the story of the prophet Lot, and how the city of Sodom was destroyed by God as a warning so others would not commit the sin of sodomy. Lee was raised as a good Muslim, and tries to follow what he has been taught are God's orders. For some time, he wore a man's outfit for praying.[16] At that time, he thought that religious duties--if conducted sincerely--were more important than his appearance but, after listening to some religious preachers, he felt that it was not right to wear men's clothing: "Sometimes I think it is not right, lying to myself, pretending to be someone else. We cannot lie to God, right? Even if I try to hide it, definitely God knows." So, after attending religious classes, he decided to wear the woman's outfit--the mukena--when praying at home.

Lia grew up in a strict Muslim family. When she pronounced herself to be a lesbian, it came as a shock to her relatives, who invoked the power of religion to cure her. When her mother went on the haj, she brought 'Zamzam water' from Mecca. The miraculous healing powers of the liquid from Mecca's Zamzam well were supposed to bring Lia back to the normal path. Dutifully, Lia drank from it and jokingly exclaimed: "Ah, my God, only now I realise how handsome Delon is!"[17] Yet she found succor in her religion when she went through a crisis in her relationship with Santi:

"When Santi hated me very much and avoided me, I prayed: "God, if it is true that you give me a guiding light, please give me a sign. But if it is a sin...please help me..." Was my relationship with Santi blessed or not? If it wasn't, surely God would have blocked the way, and if it way, would God broaden my path? As, after praying so hard, Santi and I became closer, God must have endorsed it. Does God listen to my prayer, or does God test me?"

So, even though she got together again with Santi after that fervent bout of praying, uncertainty gnaws at Lia, who realises that mainstream Islamic preachers prohibit homosexuality. Ideally, she feels that a person's religion must support people, but Islam does not do that because she is made to feel like a sinner. But, she says, the basic principle that Islam teaches is to love others. As long as she does that, Lia sees nothing wrong in herself as one of God's creatures. She realises that, particularly in the interpretation of the hadith (Islamic oral tradition), all manner of distortions have entered Islamic values, and wonders what was originally taught about homosexuality in Islam. She is aware that many Quranic texts about the status of women were manipulated in order to marginalise them, and avidly follows debates on feminist interpretations that stress that the real message of the Quran does not preach women's subordination.

Lia knows that there are lesbians in the pesantren who carry out religious obligations, such as praying and doing good deeds. If someone has been a lesbian for so long that it feels like natural character, and has been praying and fasting for many years, they cannot change into a heterosexual, she decided.

Religious values are also deeply inculcated in Sandy, who is tortured by guilt and shame about her lesbian desires. Although masculine in appearance and behaviour, she wears the mukena while praying both at home and at the mushola (small mosque) that she frequents. Since she was 23, when her mother died, she realised that what she did with her lover, Mira, was a sin and started reading religious books to discover what they said about people like her. She accepted the traditional interpretation of the story of Lot and the destruction of Sodom. When she was 25 years old, Mira left her to marry a man. Sandy was broken hearted and considered suicide. In that period of great distress, she realised that God prohibits suicide and just wanted her to give up her sinful life. She struggled hard against her desires for women and the masculinity in her:

"If I walk with women, I feel like a man; that I have to protect them. I feel that I am stronger than other women. But I also feel that I am a woman, I am sure that I am a woman, that is why I feel that I am different from others. I accept my own condition as an illness, not as my destiny. ... Yes, an illness, because we follow our lust. It we try to contain our lust, as religion teaches us, we would never be like this. So I try to stay close to God. I do my prayers, and a lot of zikir.[18] I even try to do tahajjud.[19]"

Sandy believes in the hereafter and does not want to spoil her chances of eternal bliss by engaging in something so clearly disproved of by religion, although she has not found any clear prohibitions against lesbianism in either the Quran or hadith.

Bhima, who considers himself to be a secular person, was brought up in a Muslim family. His identity card states that he is a Muslim, which got him into serious trouble when he went for his first sex-change operation at the end of the 1970s. He went through the necessary tests but the doctors hesitated when they looked at his ID, fearing the wrath of conservative clerics. Bhima was desperate:

"Listen, I have come this far! I have saved up for this, sold my car, relatives have contributed, how can you do this to me? Tell me what other religion I should take up and I will immediately get my identity card changed. I have never even been inside a mosque. I don't care about any institutionalised religion!"

The doctors did not heed his plea, instead advising him to get a letter of recommendation from a noted Muslim scholar. Undaunted, Bhima made an appointment with a progressive female psychologist who had been trained in Egypt and often gave liberal advice on Muslim issues on the radio. He managed to persuade her to write a letter of introduction to the well-known Muslim scholar Professor Hamka. Letter in hand, Bhima presented himself at the gate of Hamka's house, and was let in by the great scholar himself. Bhima pleaded his case, upon which Hamka opened the Quran and pointed to a passage that read "when you are ill, you must make all attempts to heal yourself":

"Are you ill?" Hamka asked.

Bhima nodded vehemently.

"Fine, so then tell them that the Quran advises to heal your illness."

"It is better, sir," Bhima suggested, "that you write that down for them."

With that letter, Bhima had no problem to be accepted for the first operation, in which his breasts were removed.

Widows

[...]

In Eliana's case religion played an important role in her marriage--and subsequent divorce. While still at school, she had joined an usroh group (created to teach students about religious and social issues in the days of the Suharto dictatorship). Proper sexual behaviour played an important role in their teachings. According to usroh, a wife must be sexually subservient to her husband and accept all his wishes, even if they involve him taking a second wife. Eliana felt close to her spiritual leader and tried to sexually behave as a good Muslim wife would. She forced herself to give in to all her husband's sexual wishes, including blow jobs and watching pornography with him. Yet the leader blamed Eliana for not doing enough to please her husband, saying that is why he needed a second wife. Her teacher even asked if she was a lesbian, because she could not satisfy her husband. As both her spiritual leader and husband agreed that it was not nice for a man to have an intellectually-superior woman, she played down her intelligence. Eventually she divorced her husband.

Internalised lesbophobia and conservative-religious (in this case, Muslim) norms prevented Jenar for enjoying the short lesbian relationship that she had between her two marriages. It is interesting how she phrases the conversation, starting on the topic by emphasising how much she distrusted men after her divorce (because her husband did not financially provide for their family). The relationship with her woman lover was not long underway, and had not advanced beyond kissing, but she immediately felt that, according to religion, what she did was laknat (cursed). Anyway, she added, she was a 'normal,' heterosexual woman and did not feel much aroused when they were touching. A middle-aged, male friend added to her feeling of discomfort by emphasising that she would be cursed by God if it would continue. He then took her to a dukun (shaman), where she was bathed with flowers at midnight in order to cure her. That was apparently successful, for she gave the relationship up. However, even though she had stressed that she was 'normal' and did not respond sexually to her lover's advances, she ended the conversation by saying that she felt lesbianism was a 'contagious disease'. That remark stresses her own internalised homophobia but also emphasises her helplessness and lack of agency--contagion is something that cannot be avoided. It also hints at the strength of the pull she felt for a contagion that apparently could not be easily ignored. The important role of the dukun indicates that she follows the syncretist stream of Islam, mixed with elements of the pre-Islamic Javanese religion--Kejawen. [...]

Women in same-sex relationships [...]

As in India, the human-women's-lesbian-rights discourse is gaining momentum in Indonesia. It could only develop after 1998, when the country's dictator was finally forced to resign and a new climate of political openness was created. The new sexual-rights organisations not only opened a public space to discuss women's and sexual rights but also impacted on the behaviour of individuals within their organisations (as discussed in more detail in chapter 9). Before Lee joined a lesbian-rights group, he had decided to undergo sex-reassignment therapy (SRT) to physically become a man as much as possible. Activists warned him of the operations' health risks and asked whether he really needed such a change in order to live with his spouse. Lee feels secure within the group, and is happy to find like-minded people with whom he can share many of his concerns. Lee actively sought them out after reading a newspaper article about a gay male activist: he tracked him down at his workplace and obtained the address of the lesbian group. Lee is less afraid of what will happen when their neighborhood find out that Lee's body is female--as he says: "I have done nothing wrong, I haven't disturbed anyone, I have never asked anyone for food." However, Lee is worried about the media, where gay men and lesbian women are often represented as the sources of disease and disaster.

Lia had no idea what a lesbian was when she first fell in love with a woman. There were many tomboys like her playing in the school's softball team, and she once spotted a female couple in another school's softball team. Her relationship with Santi developed without, as Lia says, any guidance of previous information. Only at college in Yogyakarta did she start reading about homosexuality on the internet. Through the Suara Srikandi portal (one of the first lesbian groups in Jakarta), she came to know of other Indonesian lesbians. Another website that she frequently visited was the Indonesian Lesbian Forum, and one of her lecturers introduced her to the gay and lesbian movement in her city. In 2004, she publicly came out at a press conference. She first joined the KPI, which has an interest group of sexual minorities, but found the attitude of her feminist friends to be unsupportive and decided to join a lesbian-only group. The women activists only wanted to discuss the public role of women and domestic violence, and told her that lesbianism was a disease and a sin.

Lia wants to broaden the lesbian movement. She feels the movement is good in theory but lacking in practice--particularly in creating alliances with other suppressed groups, such as farmers and labourers. In focusing only on lesbians, not on discrimination and marginalisation itself, she asserts that it has become too exclusive. By socialising with other movements, she argues, they will better understand lesbian issues, and, in turn, that will help the lesbian movement. It is true, she concedes, that lesbians are stigmatised by all groups in society but, since 1998 (the fall of General Suharto), the country has seen a process of democratisation. "We must take up that opportunity and not be scared of stigma," she exhorts her friends in the lesbian movement. Lia herself joined a small, radical political party, the PRD,[33] and faced stigma ("we have a lesbian comrade; that's a sin, isn't it?"), but feels that she has ultimately been welcomed. Now, her major problem is to find the finances to conduct her activism. At the time of the interview, she had lost her job and could not find the means to print handouts for her PRD comrades.

Lia is a brave forerunner. At the time of the interview, her lesbian friends were too scared to follow in her footsteps and told her that she was only dreaming. However, her heterosexual friends (in the labour movement) said that they were bored with her, and found her insistence of a connection between the struggle for sexual and labour rights to be too pushy.

Lia dreams of equal rights for lesbians. First, she would like to see a gay-marriage law implemented in Indonesia, which would ensure that the property rights of surviving spouses are protected in case one passes away. She also would like to set up a shelter for lesbians, as she knows many young lesbians who have been thrown out of their family homes and are in need of support.

Sandy is rather hesitant about the rights she would like to see introduced to Indonesian society. Most of all, she wants to be accepted as a normal human being, where no one says bad things about or harasses lesbians like her. What women do in the privacy of their bedrooms is one thing. Women should have the right to have sex, for it comes straight from the heart--it is pure love. But, in public, their behavior should be impeccable: no kissing, no hugging, no holding of hands. However, Sandy thinks that marriage rights for lesbians will not happen in Indonesia, and are only possible in Christian countries. But, minimally, she hopes to lead a life without discrimination or violence:

"If they see us as normal, they won't bother us. We are human, but if we act provocatively then it is ok for them to even hang us ... [I just hope they] won't harass us, or humiliate us. That is all I ask, that if we are being humiliated there is a law to prevent it. That a person like me is protected. To be laughed at is okay, but it is too much if they throw stones at us and if we are not allowed to work."

Sex workers want the right to work without being harassed, and women in same-sex relationships want to be treated like 'normal' human beings and enjoy socio-sexual rights, such as health benefits or the right to buy joint property. Yet the state does not provide those rights and does not protect its citizens in equal measure. As a major agent of heteronormativity, it restricts its benefits and protection to those within its margins. Couples with social stigma and conservative-religious interpretations, some of our narrators have reached deep levels of depression.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

- Giorgio Taraschi

“In the heart of Jakarta’s bustling business district [...] Mami Joyce and her girls make their home. Taking in those as young as eighteen, the human rights activist has built a safe haven for transgender women—or “waria,” as they are often called in Indonesia—to call their own.“

“Until 2011, being transgender was classified as a mental illness, and groups like the Islamic Defenders Front have not been kind to progress.“

https://www.featureshoot.com/2016/07/a-look-at-the-lives-of-transgender-women-in-indonesia/

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

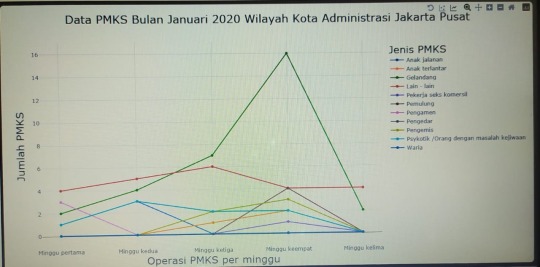

Tugas Matematika Minat

Latar Belakang:

Memasuki tahun 2020, berbagai hal yang dapat terjadi pada masyarakat Indonesia. Ada hal baik maupun hal buruk yang menanti. Di dalam masyarakat Indonesia sendiri khususnya di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat, banyak masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial atau yang disebut juga PMKS. Masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial dapat dibagi menjadi beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, anak terlantar, gelandang, pekerja seks komersil, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik atau orang dengan masalah kejiwaan, waria, dan lain-lain. Oleh karena itu kami ingin melihat proses kenaikan ataupun proses penurunan jumlah Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial (PMKS) yang terjadi di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat khususnya pada bulan Januari.

Macam-macam data dalam dataset:

1. data nominal: Jenis PMKS

2. data interval: Per Minggu

3. data rasio: Jumlah PMKS

Penjelasan Grafik:

Dari data yang kami dapat banyak sekali kasus kasus PMKS yang terjadi di bulan Januari , Dapat kita lihat di minggu pertama bulan Januari terdapat beberapa kasus yang terjadi , Psykotik terdapat 1 kasus:Gelandang terdapat 2 kasus;Pengamen 3 kasus;dan kasus lainnya terdapat 4 kasus.

Diminggu kedua terjadi beberapa kasus yang meningkat dan menurun, kasus psykotik meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 1 kasus di minggu ke-2 meningkat menjadi 3 kasus; Kasus gelandangan meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 2 kasus di minggu kedua menjadi 4 kasus; Kasus pengamen mengalami penurunan yang di minggu pertama 3 kasus menjadi 0 kasus;Kasus lainnya mengalami peningkatan yang di minggu pertama 4 kasus meningkat menjadi 5 kasus.

Di minggu ketiga banyak yang mengalami penurunan tetapi ada beberapa juga yang mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus baru. Kasus psykotik dari 3 kasus menjadi 2 kasus; kasus gelandangan dari 4 kasus menjadi 7 kasus; kasus lainnya dari 5 kasus menjadi 6 kasus; kasus anak terlantar terdapat 1 kasus; kasus pengemis 2 kasus.

Di minggu keempat banyak sekali mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus kasus baru, kasus PSK terdapat 1 kasus; Kasus pemulung terdapat 4 kasus; Kasus anak terlantar dari 1 kasus menjadi 2 kasus;Kasus psykotik tidak mengalami penurunan atau peningkatan;kasus pengemis dari 3 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus lainnya mengalami penurunan dari 6 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus gelandangan mengalami peningkatan yang sangat drastis dari 7 kasus menjadi 16 kasus. Di minggu kelima semua kasus mengalami penuruan.

Uji hipotesis H1 dan H2:

H1 = Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

H2= Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria tidak mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

Kesimpulan:

Dari data diatas yang telah kumpulkan dapat disimpulkan bahwa masih terlihat PMKS yang khususnya berada di wilayah kota administrasi Jakarta pusat yang pada bulan januari 2020 masih naik dan bertahan. Oleh karena itu masih banyak sekali pr untuk pemerintah agar mengurangi tingkat kenaikkan pada PMKS ini, agar masyarakat di Indonesia khususnya di Jakarta dapat hidup dengan sejahtera.

Sumber : Sudin Sosial Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat

Referensi data: data.jakarta.go.id

Anggota Kelompok :

1. Grace Michaella

2. Jevan Emmanuel

3. Michella Clarista

4. Michelle Huang

5. Misael Efraim

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Lo ngapain sih Chrys, ngajakin gue kesini!" ucap Samudera kesal.

"Liat air."

"Ya gue tahu Chrystal! Ini kan pantai! Orang mah kalo kebanyakan cewe ngajak cowo itu ke Mall. Nah ini lo ngajaknya kesini!" Samudera mendengus.

Chrystal membuang napas kasar. Matanya masih menatap lurus pantulan sinar matahari diatas air. Lengkungan indah tidak lepas dari wajahnya. Angin berhembus membelai wajahnya perlahan. Sesekali matanya ikut terpejam, menikmati belaiannya.

"Lo cowok atau cewek si Sam? Mulut lo lemes banget."

"Waria."

Chrystal mengeluarkan kotak dari tasnya. Lalu menyerahkannya kepada Samudera.

"Nih buat lo," ucap Chrystal ketika kontaknya sudah berada ditangan Samudera.

"Apaan nih?"

"Buka bodoh!"

Samudera langsung membuka kotak tersebut dengan terburu-buru. Penasaran!

"Cupcake?" lirih Samudera.

"Bentar, jangan dimakan dulu," ucapan Chrystal menghentikan Samudera yang hendak menyuap cupcake tersebut kemulutnya.

Chrystal mengeluarkan korek api dari tasnya.

"Tutup mata lo!"

Samudera langsung menuruti perkataan Chrystal. Dia memejamkan matanya erat.

Chrystal langsung membakar lilin yang ada di cupcake tersebut. Sesekali apinya mati dan dia berusaha menjaga agar api itu tetap menyala sampai Samudera berhasil meniupnya.

"Udah belum?" tanya Samudera.

"Udah."

"Selamat hari lahir kembali di Bumi, Samudera Mars Gibrano," kalimat lembut Chrystal menyambut penglihatan Samudera ketika dia membuka matanya.

"Najis! Sok romantis banget lo!" Samudera mencoba mengalihkan perhatiannya. Biar gak kelihatan geer!

"Lo bener-bener ya!" Chrystal memukul lengan Samudera kesal.

"Heheh... Bercanda Chrys."

"Hmm.." gumam Chrystal.

"Lo gak mau niup ini?" tanya Samudera.

"Kan yang ulang tahun lo, bodoh!"

"Berdua aja ya?"

"Gue mau niup lilin ini bareng-bareng sama lo," sambung Samudera.

"Kenapa?"

"Gue mau selamanya sama lo, Chrys. Gak peduli walaupun nanti gue jauh sama lo. Gue bakal berusaha bikin jarak kewalahan misahin gue sama lo. Dan akhirnya dia menyerah. Gue gak tahu, gue ngomong apa. Sebenarnya lo gak perlu repot-repot beliin kayak gini. Lo ada di bumi bareng gue aja udah sangat cukup buat gue, Chrys."

"Ayo tiup! Jangan lupa ucapin keinginan lo pas nanti kita tiup bareng-bareng, " ucap Samudera.

Mereka langsung meniup lilin itu bersama-sama. Angin dan pantai menjadi saksi bahwa dua insan saling menatap teduh didalam dirinya masing-masing.

"Gue berharap, asap yang terbang. Bisa buat keinginan gue sama lo terwujud."

"Lo mau tahu gak, apa keinginan gue tadi?"

"Apa?"

"Gue minta supaya waktu berjalan lambat ketika gue sedang bersama lo."

Selamat hari lahir ke bumi,

Samudera Mars Gibrano.pf

Jakarta, 20 Maret 2020.

1 note

·

View note

Link

A gang of dozens of men attacked two transgender women in Bekasi, West Java on Monday (19 November). It comes amid increasing hostility against LGBTI people in Indonesia. The men chased the two waria, an Indonesian trans female identity, stripped their clothes and attacked them with a metal rod, the Jakarta Post reports.

Some of the 50-strong gang were reportedly as young as 14. They pulled off one of the victim’s wig and cut the other’s hair.

‘You are a man, right? And your friend is a banci [transvestite]? Don’t you know that it’s a sin [to be transgender]’ the gang shouted, according to the post.

Onlookers reportedly assisted the two waria after the attack. They urged the two victims to report the incident to police, but they declined.

CLICK THE HEADER LINK TO READ THE FULL ARTICLE.

#indonesia#lgbtq#trans#transgender#gender non-conforming#hate crimes#violence tw#assault tw#misgendering tw#bigotry#oppression#transmisogyny#transphobia#cissexism#discrimination#human rights#waria#trans issues#trans visibility

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Team Pemburu Preman Polres Jakbar Bekuk Pemuda Penganiaya Waria

Team Pemburu Preman Polres Jakbar Bekuk Pemuda Penganiaya Waria

BERITA JAKARTA – Team pemburu preman Polres Metro Jakarta Barat mengamankan seorang pemuda berinisial AA (24) yang melakukan penganiayaan terhadap korban HI (28) seorang waria di Jalan Daan Mogot RT01/RW02, Rawa Buaya, Cengkareng, Jakarta Barat, Rabu (14/4/2021) kemarin.

Kasat Samapta Polres Metro Jakarta Barat, AKBP Agus Rizal mengatakan, bahwa saat team pemburu preman Polres Metro Jakarta Barat…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

Jakarta, CNN Indonesia --

Seorang pria berinisial AA (24) ditangkap lantaran melakukan penganiayaan terhadap seorang waria berinisial HI (28), di Cengkareng, Jakarta Barat, Rabu (14/4)

Penangkapan itu bermula saat tim pemburu preman Polres Metro Jakbar sedang melakukan patroli di sekitar wilayah tersebut

"Setibanya di Jalan Daan Mogot kemudian pihaknya mendapati laporan dari warga adanya seseorang waria yang mengalami penganiayaan" kata Kasat Samapta Polres Metro Jakbar AKBP Agus Rizal dalam keterangannya, Kamis (15/4)

Dari laporan itu, tim dibantu oleh warga langsung melakukan pengejaran terhadap pelaku dan akhirnya berhasil ditangkap Pelaku kemudian dibawa ke Polsek Cengkareng untuk proses pemeriksaan

Sementara itu, korban HI dilarikan ke RSUD Cengkareng untuk mendapatkan perawatan medis atas penganiayaan yang dialaminya

Sementara itu, Kepala Unit Reserse Kriminal Polsek Cengkareng AKP Arnold menjelaskan aksi penganiayaan berawal saat pelaku sedang mengendarai sepeda motor seorang diri

Kata Arnold, pelaku saat itu memang mencari seorang waria untuk memuaskan nafsu Pelaku kemudian melihat korban yang sedang mangkal dan menghampiri serta dilanjutkan dengan proses tawar menawar

"Pertama korban mematok harga sebesar Rp50 ribu, namun pelaku tawar menjadi Rp40 ribu dan disetujui oleh korban lalu langsung pelaku bayar," tutur Arnold

Setelahnya, pelaku mengajak korban ke balik pohon yang berada di pinggir jalan Keduanya kemudian melakukan tindakan asusila

Korban sempat menggerutu dan membuat pelaku kesal

Infografis Kota dengan Kekerasan Seksual Tertinggi Sepanjang 2017 (Foto: CNN Indonesia/Timothy Loen)

Arnold menyebut pelaku dan korban berdebat Pelaku yang emosi langsung memukul korban dengan menggunakan tangan Saat itu, korban sempat melawan AA lantas mengambil sebuah batang pohon dan memukul kepala HI berulang kali

"Setelah itu korban teriak minta tolong hingga warga dan tim pemburu preman Polres Metro Jakbar berdatangan mengamankan pelaku dan korban," kata Arnold

Atas perbuatannya itu, pelaku AA dikenakan dengan Pasal 351 KUHP tentang penganiayaan

(dis/arh)

[Gambas:Video CNN]

Pak Ogah menemukan artikel ini di google dengan link : https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20210415083117-12-630195/pemuda-mesum-aniaya-waria-di-cengkareng

0 notes

Text

Kasus Serda Aprilia Manganang, Dalam Islam Disebut "Khuntsa", Beda dengan "Takhannuts" (Waria/Banci/LGBT)

Nah inilah kasus yang di dalam fiqih disebut sebagai "Khuntsa".

Inilah yang harus dibantu bersosialisasi dengan benar dan dikoreksi kelaminnya sesuai dengan keadaan fisik dan DNA yang sebenarnya. Bukan atas dasar "kecenderungan perasaan" (baca: hawa nafsu) belaka.

Adapun kalau yang menyaru merupa-rupakan diri sesuai keinginan hawa nafsu belaka, padahal sebenarnya fisiknya jelas bukan itu, dalam fiqih namanya "Takhannuts", dan perlakuannya menurut Syari‘at justru harus dikucilkan dari masyarakat karena merusak.

Lebih detil soal "Khuntsa" dan "Takhannuts" dijelaskan di bagian akhir tulisan.

***

Ucapan Syukur Aprilia Manganang Usai Dipastikan sebagai Laki-laki

Mantan pemain Timnas Bola Voli Putri, Sersan Dua (Serda) Aprilia Manganang, mengaku bersyukur setelah dirinya dipastikan berjenis kelamin pria dari hasil pemeriksaan medis di RSPAD Gatot Subroto, Jakarta.

Hal itu diungkapkan Aprilia Manganang dalam konferensi pers bersama Kepala Staf Angkatan Darat (KSAD) TNI, Jenderal Andika Perkasa, pada Selasa (9/3/2021) sore WIB.

Pada konferensi pers tersebut, Aprilia Manganang memberikan keterangan secara virtual dari RSPAD Gatot Subroto.

Aprilia Manganang saat ini sedang dirawat di RSPAD Gatot Subroto setelah menyelesaikan corrective surgery tahap pertama perubahan jenis kelamin dari perempuan ke laki-laki.

Terdekat, Aprilia Manganang akan kembali naik meja operasi sebagai tahapan terakhir dari proses perubahan jenis kelaminnya.

Ketika hadir dalam konferensi pers virtual, Aprilia Manganang terlihat sehat dan sesekali menampakkan senyum ke kamera.

Aprilia Manganang di ruang perawatan didampingi oleh kedua orang tuanya, yakni Akip Zambut Manganang dan Suryati Bori Lano.

Saat diminta keterangan, Aprilia Mananang sangat bersyukur karena telah dibantu menjalani proses perubahan jenis kelamin ini.

"Ini momen yang sangat saya tunggu. Saya sangat bahagia. Saya berterima kasih kepada semua dokter yang sudah membantu saya," kata Aprilia Manganang.

"Selama 28 tahun, saya sudah menunggu hal ini. Saya bersyukur karena tahun ini bisa tercapai," tutur Aprilia Manganang.

Aprilia Manganang dipastikan berjenis kelamin laki-laki dari hasil pemeriksaan medis yang sudah dilakukan sejak 3 Februari 2021.

Menurut Kepala Staf TNI AD Jenderal Andika Perkasa, Aprilia Manganang mengalami hipospadia atau kelainan organ reproduksi ketika dilahirkan.

Karena keterbatasan peralatan medis ketika itu, Aprilia Manganang ditetapkan berjenis kelamin perempuan hanya dari tampilan fisik.

Aprilia Manganang ketika lahir tidak mendapatkan perawatan atau pemeriksaan lanjutan meskipun diketahui mengalami hipospadia.

Hal itu tidak lepas dari keterbatasan ekonomi keluarga Aprilia Manganang.

Aprilia Manganang pada akhirnya tercatat sebagai perempuan di akta kelahiran maupun di kartu tanda penduduk (KTP).

Hal itu kemudian berubah ketika Andika Perkasa dan pejabat TNI lainnya melihat ada kejanggalan dari fisik Aprilia Manganang.

Dari hasil pengamatan fisik tersebut, Andika Perkasa pada akhirnya langsung meminta Aprilia Manganang menjalani pemeriksaan medis hingga operasi perubahan jenis kelamin.

Jajaran TNI juga akan mengakomodasi seluruh proses dokumen-dokumen terkait perubahan identitas, termasuk di antaranya pergantian nama dan jenis kelamin.

Perubahan nama sesuai dengan UU Nomor 23 Tahun 2006 tentang Kependudukan. Andika berharap Pengadilan Negeri Tondano memberikan dan menetapkan perubahan nama tersebut.

"Dari nama sebelumnya, kepada nama yang nanti akan dipilih oleh Sersan Manganang dan orang tuanya," ujar Andika.

Sebagai atlet voli putri, Aprilia Manganang berhasil meraih banyak prestasi di level klub maupun timnas.

Aprilia Manganang tercatat pernah empat kali meraih gelar juara Proliga pada 2015, 2016, 2017 dan 2019.

Di level timnas putri, prestasi terbaik Aprilia Manganang adalah meraih medali perak SEA Games 2017.

Aprilia Manganang memutuskan pensiun sebagai atlet voli pada 2020. Setelah pensiun, Aprilia Manganang fokus melanjutkan sebagai prajurit TNI AD yang sudah dia emban sejak 2016.

(Sumber: Kompas)

***

Khuntsa dan Takhannuts

Identitas seseorang itu menjadi laki-laki atau perempuan, tidak ditentukan oleh omongan dirinya. Tetapi ditentukan oleh bentuk pisik dan fungsi-fungsi faat tubuhnya secara biologis atau medis.

Biarpun secara hukum sekuler telah ditetapkan bahwa seorang waria menjadi wanita, namun dalam pandangan hukum Islam harus dikembalikan secara pisik dan fungsi biologis itu tadi.

Biarpun si waria mengatakan bahwa dirinya 100 % perempuan, tapi semua itu tidak bisa dijadikan landasan sama sekali. Dalam syariat Islam dikenal dua hal berkaitan dengan fenomena tersebut. Pertama, adalah istilah Khuntsa dan kedua adalah Takhannuts. Keduanya meski mirip-mirip tapi berbeda secara mendasar.

A. Khuntsa

Khuntsa adalah orang yang secara faal dan biologis berkelamin ganda. Namun diantara sekian banyak fenomena di dunia ini, kasus ini tergolong sangat sedikit seseorang yang memiliki kelamin laki-laki dan kelamin wanita sekaligus.

Dan Islam sejak dahulu telah memiliki sikap tersendiri berkaitan dengan status jenis kelamin orang ini. Sederhananya, bila alat kelamin salah satu jenis itu lebih dominan, maka dia ditetapkan sebagai jenis kelamin tersebut. Artinya, bila organ kelamin laki-lakinya lebih dominan baik dari segi bentuk, ukuran, fungsi dan sebagainya, maka orang ini meski punya alat kelamin wanita, tetap dinyatakan sebagai pria. Tentunya sebelum dilakukan operasi perubahan atau suntik silikon. Dan sebagai pria, berlaku padanya hukum-hukum sebagai pria. Antara lain mengenai batas aurat, mahram, nikah, wali, warisan dan seterusnya.

Dan sebaliknya, bila sebelum operasi organ kelamin wanita yang lebih dominan dan berfungsi, maka jelas dia adalah wanita, meski memiliki alat kelamin laki-laki. Dan pada dirinya berlaku hukum-hukum syariat sebagai wanita.

Namun ada juga yang dari segi dominasinya berimbang, yang dalam literatur fiqih disebut dengan istilah “Khuntsa Musykil”. Namanya saja sudah musykil, tentu merepotkan, karena kedua alat kelamin itu berfungsi sama baiknya dan sama dominannya. Untuk kasus ini, dikembalikan kepada para ulama untuk melakukan penelitian lebih mendalam untuk menentuakan status kelaminnya.

B. Takhannuts

Yang paling sering kita temukan kasusnya justru kasus takhannuts, yaitu orang yang berlagak atau berpura-pura jadi khuntsa, padahal dari segi pisik dia punya organ kelamin yang jelas. Sehingga sama sekali tidak ada masalah dalam statusnya apakah laki atau wanita. Pastikan saja alat kelaminnya sebelum operasi, maka statusnya sesuai dengan alat kelaminnya.

Memang ada sebagian mereka yang melakukan operasi kelamin, tapi operasi itu sifatnya cuma aksesoris belaka dan tidak bisa berfungsi normal. Karena itu operasi tidak membuatnya berganti kelamin dalam kacamata syariat. Sehingga status tetap laki-laki meski suara, bentuk tubuh, kulit dan seterusnya mirip wanita.

Sedangkan yang berkaitan dengan perlakuan para waria ini, jelas mereka adalah laki-laki, karena itu ta‘amul/perlakuan kita dengan mereka sesuai dengan etika mereka sebagai laki-laki. Dan karena tetap laki-laki, maka pergaulan mereka dengan wanita persis sebagaimana adab pergaulan laki-laki dengan wanita. Para wanita tetap tidak boleh berkhalwat, ihktilat, sentuhan kulit, membuka aurat dan seterusnya dengan para waria ini. Termasuk bila waria mati, wajib dimandikan sebagai mayat laki-laki, karena mereka pada hakikatnya adalah laki-laki 100 %.

Dosa Besar Takhannuts

Orang yang melakukan takhnnuts ini jelas melakukan dosa besar karena berlaku menyimpang dengan menyerupai wanita.

Rasulullah s.a.w. pernah mengumumkan, bahwa perempuan dilarang memakai pakaian laki-laki dan laki-laki dilarang memakai pakaian perempuan. Di samping itu beliau melaknat laki-laki yang menyerupai perempuan dan perempuan yang menyerupai laki-laki. Termasuk diantaranya, ialah tentang bicaranya, geraknya, cara berjalannya, pakaiannya, dan sebagainya.

Sejahat-jahat bencana yang akan mengancam kehidupan manusia dan masyarakat, ialah karena sikap yang abnormal dan menentang tabiat.

Rasulullah s.a.w. pernah menghitung orang-orang yang dilaknat di dunia ini dan disambutnya juga oleh Malaikat, diantaranya ialah laki-laki yang memang oleh Allah dijadikan betul-betul laki-laki, tetapi dia menjadikan dirinya sebagai perempuan dan menyerupai perempuan; dan yang kedua, yaitu perempuan yang memang dicipta oleh Allah sebagai perempuan betul-betul, tetapi kemudian dia menjadikan dirinya sebagai laki-laki dan menyerupai orang laki-laki (Hadis Riwayat Thabarani).

http://www.daarulmuwahhid.org/dm/index.php/artikel/bacaan-islami/185-khuntsa-dan-takhannuts

source https://www.kontenislam.com/2021/03/kasus-serda-aprilia-manganang-dalam.html

source https://www.ayojalanterus.com/2021/03/kasus-serda-aprilia-manganang-dalam.html

0 notes

Text

Reception of Gender Diversity in Indonesia and Women’s Erotic Literature

Selections from "Between sastra wangi and perda sharia: debates over gendered citizenship in post-authoritarian Indonesia," Susanne Schröter, Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs (RIMA), 48(1), 2014.

In Indonesia, we encounter a somewhat paradoxical situation where gender deviance is tolerated in many quarters while there is, at the same time, an increasingly repressive-patriarchal gender mainstream. This becomes particularly apparent in the issue of acceptance of queer lifestyles. After the end of the New Order period, the emerging liberalisation in the urban areas included that aspect as well. A group called Q-Munity has organised an annual queer film festival, the Q!Festival, in Jakarta since 2002 and activists join in public debates, trying to reduce prejudice and to put an end to discrimination. Within the women’s rights network, Kartini, a training manual was developed to strengthen the position of non-heteronormative life models (Bhaiya und Wieringa 2007), and Siti Musdah Mulia proclaimed in the newspaper Jakarta Globe of 23 September 2009 that lesbian desire was created by God just like its heterosexual counterpart and hence must be accepted as natural. Until today, her statement triggers controversial discussions within Indonesia and beyond.

As could be expected, this unusual awakening was criticised by Islamist hardliners as an adoption of Western decadence. Performance venues of the Q! Festival were repeatedly raided by ‘goon squads’ and in 2010 Surabaya became the site of an éclat that was even covered by the international media. It was sparked by plans of the Asian branch of the International Lesbian and Gay Association to hold an international conference in March of that year. There had been similar conventions before in Mumbai, Cebu and Chiang Mai. The organisers were eager to be as discrete as possible in order to avoid protests. There was to be no Gay Pride Parade, and the organisers planned to publish a press release only on the last day of the event. Due to an unlucky coincidence, however, the local media learned about the planned event in its run-up and there were quick reactions by Islamic organisations. Statements were issued by religious authorities, claiming that homosexuality is irreconcilable with both Indonesian culture and Islam. Such language immediately mobilised the Islamic Defenders Front (Front Pembela Islam) and the Indonesian fraction of Hizb-ut Tahrir[14] to take militant action against the organisers. As a result, the local authorities prohibited the conference and those participants who had already arrived were besieged at their hotels by the mob until they were brought to safety under police protection (Vacano 2010).

These incidents appear to be at odds with the supposedly tolerant attitude towards gender variances in Indonesia as described by anthropologists such as Boellstorff (2005), Peletz (2009), Davis (2010) and Blackwood (2010). These scholars base their claims on the existence of so-called third and fourth genders rooted in local social orders. An often-cited example of this are the Bugis of South Sulawesi who use five gender terms: besides women and men, there are calalai (masculine women), calabai (feminine men), and bissu (ritual experts and shamans who are ambiguous in terms of gender). The bissu have always particularly attracted the attention of anthropologists, who interpreted them as a culturally-accepted variant of non-binary gender. In the Bugis system of gender categories, they are classified as calabai, that is, individuals with a male body and a feminine or ambivalent habitus. They are viewed as embodying a pre-Islamic, double-gendered Supreme Being which is attributed the ability to mediate between humans and spirits; hence, they act as healers and shamans. There is some debate, however, among anthropologists about whether the existence of this phenomenon can actually be interpreted as an indicator of tolerance and liberalism. Birgit Röttger-Rössler, who has done fieldwork among the Bugis, is sceptical, and even objects to applying the term ‘third gender’. According to her, calabai are ‘institutionalised, socially-accepted variants or subcategories of the male gender’ (Röttger-Rössler 2009:287, translation mine). She adds that these types of transgenderism can by no means be interpreted as a negation of heteronormative gender concepts. The reverse is true: they reinforce the latter. As Röttger-Rössler sees it, the order legitimated by this exception is not only ‘defined clearly and rigidly’(Röttger-Rössler 2009:287–8), but also asymmetrical, putting women at a disadvantage.

On top if this, the mere existence of a local ‘third gender’ does not allow the conclusion that local communities are generally characterised by a liberal attitude towards gender issues. This becomes particularly evident when modern phenomena of transgression, which are usually referred to as queer, meet local forms of deviance. The mobilisation of queer activists in Indonesia and the resulting Islamic counteroffensive is a well-documented example of this.

The same applies to shifts in local gender structures that were triggered by the general climate of open-mindedness after the end of the New Order. In the year when the conference in Surabaya was wrecked by conservative moral ideas, there was also a remarkable public debate on local Indonesian transgenders who are subsumed by the collective term of waria.[15] The debate was sparked by a ‘Miss Aceh Transsexual’ beauty pageant held in February 2010. Many people in Aceh have ambivalent and contradictory attitudes towards waria. On the one hand, they view the latter’s existence as a disgrace for the community; on the other hand, waria are tolerated half-heartedly, not least because men secretly relish their sexual services. Waria often use their beauty parlours and hairdressing salons as brothels and engage in prostitution in the semi-clandestine red light district of the capital Banda Aceh. It is obvious that neither Aceh society nor the police intend to actually eliminate this option for extramarital sex, which is punishable under current legislation. Representatives of the authorities, however, take advantage of the waria’s extralegal status and arbitrary arrests as well as rape in police custody are common. Everyday discrimination, humiliation, and assaults by the sharia police are rampant. In the wake of the devastating tsunami in 2004, which was interpreted by Islamic clerics as a warning to disobedient believers, waria were repeatedly expelled from their homes and businesses because their neighbours feared that their presence might evoke the wrath of God to descend upon them again.

In Indonesia, both the human rights and the Qur’an and Sunna are invoked in the discussion about whether or not the existence of waria is legitimate. In Aceh, more importance is attached to the religious narratives of justification, however, than to secular reasoning, because Islam is viewed as the measure of all things. In the end, phenomena that are incompatible with the commandments of Allah will not gain acceptance. The experts disagree, however, about what is compatible with Islam, particularly if waria make their appearance in modern contexts. The pageant mentioned above, where they performed in burlesque costumes, sparked a pan-Indonesian controversy which dominated the headlines of the local and national press for several days. Well-known politicians, activists, and Islamic clerics piped up to express their opinion. The majority of the religious contributions condemned waria as being immoral and sinners, while secular commentators came to their defence, referring to minority rights.

I had the opportunity to discuss that issue in March 2010 with students at the State Islamic University (Universitas Islam Negeri, UIN) in Yogyakarta and at the Gadjah Mada University (UGM) which is also located in Yogyakarta. The Islamic students, in particular, engaged in a lively debate about whether the Qur’an makes a clear statement about the matter and what the prophet Muhammad said about it. This was their sole criterion for tolerating or condemning waria. On the personal level, the subject did not trigger any emotions in them; it was a purely matter-of-fact discussion without any recourse to moral categories. My colleague Sahiron Syamsuddin, a respected Islamic scholar with whom I held the event, eventually made an important point. He said that three gender categories were already known in Muhammad’s time: men, women, and khunta--transgenders who resembled the waria. He went on to explain that the third gender had fallen into oblivion due to subsequent patriarchal developments. This was acceptable to the students. Sahiron’s reasoning is typical of so-called ‘progressive’ Muslims who attempt to substantiate liberal ideas with little-known data from the Islamic past or new interpretations of the Qur’an and Sunna.

As becomes apparent from the abovementioned examples, upon closer examination, the much-cited Indonesian open-mindedness with regard to gender variances turns out to be a restrictive straightjacket into which some phenomena can be fitted, while others cannot. Transgender individuals are tolerated and may even hold respected positions, provided that they stay within narrow, strictly-defined social confines or already-accepted cultural constructs. Above all, they are expected to be inconspicuous. As long as a beauty pageant is held in a village, whether or not the event is made into a scandal depends on the social relations between the individual actors. At the national level, it is not possible to rely on such local relations. Other narratives of justification then take effect, particularly narratives backed by Islam. It appears that only a minority of the Indonesian Muslims subscribe to progressive interpretations of the Qur’an and the Islamic traditions, and my colleague Syamsuddin would certainly have had a hard time if rhetorically-versed Islamists had participated in the discussion. According to a study conducted in 2013 by the Pew Research Center, 93 per cent of all Indonesians disapprove of homosexuality. Thus, in terms of tolerance, the country is behind Malaysia (86 per cent) and Pakistan (87 per cent) and at the same level as Palestine. As has been noted by Jamison Liang, homophobia is on the rise (Liang 2010). This development is due not only to the strength gained by a conservative, partly militant Islam, but also to the fact that by now there is a public debate on the issue of gender deviance.

----

The virulently liberal face of Indonesian culture, despite Islamist zealotry, is also represented by the genre of female erotic literature. Called sastra wangi (fragrant literature) it caused an international sensation.[12] Writers such as Djenar Maesa Ayu, Ayu Utami, Fira Basuki, Dewi Lestari, and Nova Riyanti Yusuf picked out incest, extramarital sex, and homosexuality as central themes. They were not afraid of giving drastic descriptions of sexuality and they played offensively with the breach of all social conventions (Hatley 1999; Listyowulan 2010). One of the most prominent examples is Ayu Utami’s book Saman, of which more than one hundred thousand copies were sold in Indonesia. The novel is about the sexual adventures of three young women from good families, about split identities and the transgression of patriarchal moral ideas. Shakuntala, one of the protagonists, deflowers herself with a spoon and feeds the hymen to a dog. Later, she enters into a lesbian relationship in which she takes the male-connoted part. These are the scandal-provoking parts of the novel. It also has, however, another, political dimension which centres on the priest Saman. During a conflict, he takes sides with oppressed rubber farmers who are struggling against dispossession. He is denounced as their leader, arrested and tortured.

[cw for discussion of incest, child sexuality/assault]

In Djenar Maesa Ayu’s Menjusuh Ayah (Suckled by the Father), a woman recounts the sexual childhood experiences she had with older men, including her father. She states that as a baby she was not fed her mother’s milk, but her father’s semen. When she confronts her father with that story, he accuses her of lying and hits her with his belt. She insists, however, on her version of the past. The first-person narrator tells the reader that her father eventually refused to feed her any longer. Hence, she turned to his friends as a child. ‘I liked the way they slowly pushed down my head and allowed me to suckle there for a long time’ (Ayu 2008:95). When one of her father’s friends penetrates her, she kills him: ‘I am a woman, but I am not weaker than a man’, she writes, ‘because I have not suckled on mother’s breast’ (Ayu 2008:97).

[end cw]

The new erotic women’s literature led to a controversial discussion in Indonesia. The term sastra wangi itself alludes to the public erotic self-staging of the women, which was eagerly picked up by the media. Many stories about the young writers opened with exact descriptions of their looks, mentioning the high heels, the strapless t-shirts, the long loose hair, or the fact that the audience smoked and consumed alcohol during the readings. Like the provocative titles and texts, the media stagings brought fast fame and high sales figures. On the other hand, the women were accused of using sex as a marketing strategy. Not surprisingly, criticism of the taboo breaches came from the religious side, while secular-urban intellectuals mostly appreciated the new literary awakening. Saman won several awards, including a writing contest of the Jakarta Art Institute in 1997 and an award of the Jakarta Art Council (Dewan Kesenian Jakarta) for best novel in 1998. In 2000, Ayu Utami won the Claus Award in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, there has been some reserve on the part of literary scholars. Katrin Bandel criticises the unquestioned male perspective of the sastra wangi (Bandel 2006:115), Arnez and Dewojati find fault with the virulent phallocentrism (Arnez and Dewojati 2010).[13] Positive appraisal, however, prevails in the overall judgment. According to Arnez and Dewojati, the issue of whether sastra wangi can be called emancipatory is still controversial, but nevertheless ‘it can be claimed that in modern Indonesian literature such an open discussion of sexuality and female desire has not taken place before, especially not in such an outspoken language’ (Arnez and Dewojati 2010:20).

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

TUGAS MTK MINAT

Latar Belakang:

Memasuki tahun 2020, berbagai hal yang dapat terjadi pada masyarakat Indonesia. Ada hal baik maupun hal buruk yang menanti. Di dalam masyarakat Indonesia sendiri khususnya di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat, banyak masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial atau yang disebut juga PMKS. Masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial dapat dibagi menjadi beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, anak terlantar, gelandang, pekerja seks komersil, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik atau orang dengan masalah kejiwaan, waria, dan lain-lain. Oleh karena itu kami ingin melihat proses kenaikan ataupun proses penurunan jumlah Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial (PMKS) yang terjadi di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat khususnya pada bulan Januari.

Macam-macam data dalam dataset:

1. data nominal: Jenis PMKS

2. data interval: Per Minggu

3. data rasio: Jumlah PMKS

Penjelasan Grafik:

Dari data yang kami dapat banyak sekali kasus kasus PMKS yang terjadi di bulan Januari , Dapat kita lihat di minggu pertama bulan Januari terdapat beberapa kasus yang terjadi , Psykotik terdapat 1 kasus:Gelandang terdapat 2 kasus;Pengamen 3 kasus;dan kasus lainnya terdapat 4 kasus.

Diminggu kedua terjadi beberapa kasus yang meningkat dan menurun, kasus psykotik meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 1 kasus di minggu ke-2 meningkat menjadi 3 kasus; Kasus gelandangan meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 2 kasus di minggu kedua menjadi 4 kasus; Kasus pengamen mengalami penurunan yang di minggu pertama 3 kasus menjadi 0 kasus;Kasus lainnya mengalami peningkatan yang di minggu pertama 4 kasus meningkat menjadi 5 kasus.

Di minggu ketiga banyak yang mengalami penurunan tetapi ada beberapa juga yang mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus baru. Kasus psykotik dari 3 kasus menjadi 2 kasus; kasus gelandangan dari 4 kasus menjadi 7 kasus; kasus lainnya dari 5 kasus menjadi 6 kasus; kasus anak terlantar terdapat 1 kasus; kasus pengemis 2 kasus.

Di minggu keempat banyak sekali mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus kasus baru, kasus PSK terdapat 1 kasus; Kasus pemulung terdapat 4 kasus; Kasus anak terlantar dari 1 kasus menjadi 2 kasus;Kasus psykotik tidak mengalami penurunan atau peningkatan;kasus pengemis dari 3 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus lainnya mengalami penurunan dari 6 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus gelandangan mengalami peningkatan yang sangat drastis dari 7 kasus menjadi 16 kasus. Di minggu kelima semua kasus mengalami penuruan.

Uji hipotesis H1 dan H2:

H1 = Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

H2= Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria tidak mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

Kesimpulan:

Dari data diatas yang telah kumpulkan dapat disimpulkan bahwa masih terlihat PMKS yang khususnya berada di wilayah kota administrasi Jakarta pusat yang pada bulan januari 2020 masih naik dan bertahan. Oleh karena itu masih banyak sekali pr untuk pemerintah agar mengurangi tingkat kenaikkan pada PMKS ini, agar masyarakat di Indonesia khususnya di Jakarta dapat hidup dengan sejahtera.

Sumber : Sudin Sosial Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat

Referensi data: data.jakarta.go.id

Anggota Kelompok :

1. Grace Michaella

2. Jevan Emmanuel

3. Michella Clarista

4. Michelle Huang

5. Misael Efraim

0 notes

Photo

Latar Belakang:

Memasuki tahun 2020, berbagai hal yang dapat terjadi pada masyarakat Indonesia. Ada hal baik maupun hal buruk yang menanti. Di dalam masyarakat Indonesia sendiri khususnya di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat, banyak masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial atau yang disebut juga PMKS. Masyarakat yang menjadi Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial dapat dibagi menjadi beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, anak terlantar, gelandang, pekerja seks komersil, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik atau orang dengan masalah kejiwaan, waria, dan lain-lain. Oleh karena itu kami ingin melihat proses kenaikan ataupun proses penurunan jumlah Penyandang Masalah Kesejahteraan Sosial (PMKS) yang terjadi di wilayah Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat khususnya pada bulan Januari.

Macam-macam data dalam dataset:

1. data nominal: Jenis PMKS

2. data interval: Per Minggu

3. data rasio: Jumlah PMKS

Penjelasan Grafik:

Dari data yang kami dapat banyak sekali kasus kasus PMKS yang terjadi di bulan Januari , Dapat kita lihat di minggu pertama bulan Januari terdapat beberapa kasus yang terjadi , Psykotik terdapat 1 kasus:Gelandang terdapat 2 kasus;Pengamen 3 kasus;dan kasus lainnya terdapat 4 kasus.

Diminggu kedua terjadi beberapa kasus yang meningkat dan menurun, kasus psykotik meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 1 kasus di minggu ke-2 meningkat menjadi 3 kasus; Kasus gelandangan meningkat yang di minggu pertama terjadi 2 kasus di minggu kedua menjadi 4 kasus; Kasus pengamen mengalami penurunan yang di minggu pertama 3 kasus menjadi 0 kasus;Kasus lainnya mengalami peningkatan yang di minggu pertama 4 kasus meningkat menjadi 5 kasus.

Di minggu ketiga banyak yang mengalami penurunan tetapi ada beberapa juga yang mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus baru. Kasus psykotik dari 3 kasus menjadi 2 kasus; kasus gelandangan dari 4 kasus menjadi 7 kasus; kasus lainnya dari 5 kasus menjadi 6 kasus; kasus anak terlantar terdapat 1 kasus; kasus pengemis 2 kasus.

Di minggu keempat banyak sekali mengalami peningkatan dan terdapat kasus kasus baru, kasus PSK terdapat 1 kasus; Kasus pemulung terdapat 4 kasus; Kasus anak terlantar dari 1 kasus menjadi 2 kasus;Kasus psykotik tidak mengalami penurunan atau peningkatan;kasus pengemis dari 3 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus lainnya mengalami penurunan dari 6 kasus menjadi 4 kasus;kasus gelandangan mengalami peningkatan yang sangat drastis dari 7 kasus menjadi 16 kasus. Di minggu kelima semua kasus mengalami penuruan.

Uji hipotesis H1 dan H2:

H1 = Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

H2= Pada bulan januari beberapa jenis PMKS yaitu, anak-anak jalanan, terlantar, pemulung, pengamen, pengedar, pengemis, psykotik, atau orang yang mengalami masalah kejiwaan dan waria tidak mengalami proses kenaikan jumlah penyandang masalah kesejahteraan sosial (PMKS).

Kesimpulan:

Dari data diatas yang telah kumpulkan dapat disimpulkan bahwa masih terlihat PMKS yang khususnya berada di wilayah kota administrasi Jakarta pusat yang pada bulan januari 2020 masih naik dan bertahan. Oleh karena itu masih banyak sekali pr untuk pemerintah agar mengurangi tingkat kenaikkan pada PMKS ini, agar masyarakat di Indonesia khususnya di Jakarta dapat hidup dengan sejahtera. Sumber : Sudin Sosial Kota Administrasi Jakarta Pusat Referensi data: data.jakarta.go.idAnggota Kelompok :

1. Grace Michaella

2. Jevan Emmanuel

3. Michella Clarista

4. Michelle Huang

5. Misael Efraim

0 notes

Text

Sekolah Islam Khusus Waria Pertama Dibuka di Bangladesh

Sekolah Islam Khusus Waria Pertama Dibuka di Bangladesh

HIDAYATUNA.COM, Jakarta – Kabar mengejutkan datang dari Bangladesh. Di mana pertama dalam sejarahnya, sebuah sekolah Islam yang dikhususkan bagi kelompok waria (transgender) diresmikan.

Pada kesempatan peresmian, sekolah Islam khusus waria ini juga menggratiskan buku buku ke siswa mereka untuk periode ajaran baru. Sekolah dengan nama Madrasah Gender Ketiga Dawatul Quran berada di ibukota…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Tarif pijat panggilan hotel Khusus pria & waria Kawasan jakarta barat & selatan Rp 700.000/ 3jam Biaya sudah termasuk jasa dan transportasi #pijattamananggrek #pijatcengkareng #pijattomang #pijatjajartabarat #pijatjakartalivingstarapartemen #pijatpermatahijau #pijatkebunjeruk #priapanggilanjakarta #priapanggilanpria #priapanggilanwaria #pijatmurahjakarta #pijatpanggilanpasarrebo #pijatkedoya #pijatslipi #pijatpanggilanhoteldijakarta #pijatpanggilantante #pijatpanggilancewek #pijatpanggilanmahasiswi #pijatpanggilanemak #pijatpanggilantangsel #pijatpanggilanbsd #pijattangsel #pijatpanggilanrumah #pijatpanggilanapartemen #sensual_shots_ #sensualmassages #sensualmassagejakarta #sensualmassagespabali #handjobmassagejakarta #priapijatpriajakarta (di Jakarta, Indonesia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CJxdCSnjRs1/?igshid=163bk6gm3cd7v

#pijattamananggrek#pijatcengkareng#pijattomang#pijatjajartabarat#pijatjakartalivingstarapartemen#pijatpermatahijau#pijatkebunjeruk#priapanggilanjakarta#priapanggilanpria#priapanggilanwaria#pijatmurahjakarta#pijatpanggilanpasarrebo#pijatkedoya#pijatslipi#pijatpanggilanhoteldijakarta#pijatpanggilantante#pijatpanggilancewek#pijatpanggilanmahasiswi#pijatpanggilanemak#pijatpanggilantangsel#pijatpanggilanbsd#pijattangsel#pijatpanggilanrumah#pijatpanggilanapartemen#sensual_shots_#sensualmassages#sensualmassagejakarta#sensualmassagespabali#handjobmassagejakarta#priapijatpriajakarta

0 notes

Photo

Robert Levinson, profesor psikologi di University of California Berkeley, meneliti serta mengundang beberapa pasangan ke laboratoriumnya. Ia meminta masing-masing pasangan untuk mendiskusikan sesuatu yang membuat dia kesal tentang pasangannya. Hasilnya didapat bahwa pasangan yang berdiskusi sambil tertawa dan senyum bisa merasakan emosi yang lebih baik. Lalu dengan tertawa, pasangan tersebut juga merasakan tingkat kepuasan lebih tinggi dalam hubungan asmaranya dan menjalin hubungan lebih langgeng. Manfaat Tertawa untuk Kesehatan:😃 Mengurangi stres. Tertawa dapat mengurangi tingkat stres yang Anda alami. 😃Menyehatkan jantung. Tertawa juga bisa menyehatkan jantung. 😃Meningkatkan sistem kekebalan tubuh. Tertawa dapat meningkatkan jumlah dan fungsi sel-sel dalam sistem imun. 😃 Mengurangi depresi. #Tertawa sudah sejak lama dipercaya sebagai obat mujarab untuk mengembalikan semangat dan membuat seseorang lebih sehat. Selain itu, ternyata ada beragam manfaat tertawa yang perlu Anda ketahui. Saat tertawa, hormon endorfin akan dilepaskan sehingga Anda akan merasa lebih baik. Selain bermanfaat untuk kesehatan mental, tertawa juga berpengaruh positif terhadap banyak organ tubuh. . . . . . . . . . #humoris #humorreceh #ketawabareng #ketawangakak #dagelanviral #dagelanlucu #anaksma #twiterreceh #twitterviral #emakemakjamannow #gondrongindonesia #ngakak #ngakakkocak #ngakaksehat #anakhits #emakhits #beritaunik #keluargamuslim #mahasiswaindonesia #korea #anaksekolahan #toilet #waria (at Pondok Indah Jakarta Selatan) https://www.instagram.com/p/CJINXHcAvqi/?igshid=18eazfr98nhyv

#tertawa#humoris#humorreceh#ketawabareng#ketawangakak#dagelanviral#dagelanlucu#anaksma#twiterreceh#twitterviral#emakemakjamannow#gondrongindonesia#ngakak#ngakakkocak#ngakaksehat#anakhits#emakhits#beritaunik#keluargamuslim#mahasiswaindonesia#korea#anaksekolahan#toilet#waria

0 notes

Photo

[E. van de Wall-Assé] seorang wanita yang berperan sebagai waria dalam sebuah drama dengan lakon (Pangeran Negoro Joedho: moral kerajaan dalam empat babak / V.Ido - Weltevreden: Visser & Co.) di Batavia, sekitar tahun 1918. • 📸: Leiden University Libraries • #potolawas #potolawasjakarta #jakartatempodoeloe #jakarta #batavia #jakarta #theatre #drama (di Jakarta, Indonesia) https://www.instagram.com/p/CHJboXVnMSd/?igshid=efw8sbcpr7kd

0 notes