#Also a BIBLICAL figure - one of the sons of moses

Text

Okay so I'm reading a pjo dark fic, Percy falls into tartarus without Annabeth, standard fare, it's really good, so I start to wonder about the spheres of power of each of his travelling companions (Bob and Damascus (+drakon)). Obviously both of them met percabeth in canon, else I wouldn't bring it up.

And I think there's something to be said for Percy Jackson, half blood, to befriend the titan of mortality and the giant of peace.

#Iapetus is the father of both prometheus and atlas btw#Apparently he had 4/5 kids each representing a folly of man or smth#Also a BIBLICAL figure - one of the sons of moses#In both he's occasionally called one of the forefathers of humanity which you know is KIND OF A BIG DEAL#Damasen is apparently only referenced in a poem where he's born with a spear and gets given a shield and the drakon had a sister#Who resurrected him with a plant someone else then found and gave to zeus to heal him#Think the 'titan of peace opposite of ares' thing is a riordan invention but luckily that's what we're talking about!#Anyway the fic in question is 'falling for you' and honestly at the point I'm at Annabeth is having a significantly worse time than Percy#Who is literally in tartarus with a smashed leg and a mysterious arai curse#While she's safe and warm on the argo 2 she's just stressing that bad. Meanwhile her bf is cozy riding a drakon as a hammock duel swords#Food and drink two friendly armed titan/giant bodyguards on either side. Literally what more could you want.#Pjo#pjo hoo toa#percy jackson#annabeth chase#iapetus#Rip to Nico but Percy's just built different... Let's see how long it takes for it to go downhill XD

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Could Izzy be Jewish? Some meta about the name Israel in the context of 17th/18th century English customs.

While I am perfectly fine with all kinds of headcanons behind Izzy's name, as an onomastics (the linguistic study of names) enthusiast and a philologist, I have to throw my hat into the ring. Let me tell you a bit more about the name in the context of English language itself. The canon does not tell us anything about Izzy's religious background, so I thought I'd spam you with some linguistic and historical knowledge lol.

Most people automatically connect the name Israel with the state of Israel, and it is, of course, a correct connection, as the name is the same in terms of etymology. The name is Hebrew and comes from the Book of Genesis. As a first name, it is ancient, as it was proven to have appeared on Eblaite language cuneiform tablets (on the lands of modern-day Syria).

However, we need to take into account that Israel Hands was born in the 18th century, when the naming customs were different from the BCE ones.

The most common naming custom in 18th century England was naming children after other family members - often the first son was named after the father's father, and the second son after the mother's father. The third son was named after the father himself. Of course, not every family followed that tradition, and sometimes (as it was a case with Stede) parents chose more unusual names.

Ever since the 10th century the Old Testament Hebrew names were popular in the Celtic areas of the world, with historical figures such as Israel the Grammarian bearing the name whilst having strong ties to the Latin Church.

In the late 1600s and 1700s England was predominantly Protestant, with the Church of England being the "default" church of the English people. However, the Anglicans of that era tended to identify their practices and traditions with Jewish ones over Catholic ones, as the Anglicans considered themselves to be one of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Puritans and many other non-conformist dissenters (Protestants not agreeing with the CoE) especially liked to give their children names from the Old Testament and often chose the Hebrew spelling. Puritans also adapted some of their religious customs from Jews.

Jews began to resettle in England in the 1650s (after being expelled and banned by king Edward I in 1290 with the rise of antisemitism in the kingdom) but by the 1700s their numbers were still very low in comparison with Protestants. In 1690 their number was reported as barely 400.

However, there are historical reports of larger numbers of Jews (many Dutch of Portuguese Sephardic Jewish origin like Moses Cohen Henriques) in Jamaica in that time, especially in Kingston.

Biblical names were usually given by religious families - among the most popular were Benjamin, Isaac and Abraham. Less religious people and royalists often chose names connected to the historical English royals (like William, Edward, or Henry).

It is also worth noting that Israel might have not been the real name of the historical pirate - in 1719 he is referred to as Hesikia (Hezekiah) Hands.

So, to sum up: From a linguistic point of view, having the name Israel does not simply imply that its bearer comes from a Jewish family or is Jewish themself. As the Hebrew names were extremely popular amongst the dissidents that fled England to avoid religious persecution and ended up in America, it is very likely that the historical Israel Hands came from such a family. There is no historical information about his place of birth, though, so he might have been born in Jamaica.

As for the OFMD's Izzy Hands? We have absolutely no idea - his austerity and stark personality, as well as the tendency to dress all in black, might suggest Puritan upbringing, but since we were not told anything explicitly, you can all safely create your own headcanons without offending anyone, I believe. While the historical pirate likely wasn't Jewish, OFMD mostly avoids the topic of religion altogether (except for Jim's case), so the fans are free to interpret the characters in a way they enjoy.

This post was meant to be a "fun fact" type of a post, giving some background to the name itself in the context of English language and culture. I am neither Jewish nor Anglican, but I am an academically educated philologist obsessed with the etymology and names.

I might write the next post about the name Stede, as it is quite a curious case.

#i just like names okay#izzy hands#israel hands#our flag means death#ofmd#ofmd meta#ofmd meta post#ofmd headcanon#you cant stop a philologist from overanalyzing language stuff#etymology#onomastics#english philology freaks and all

123 notes

·

View notes

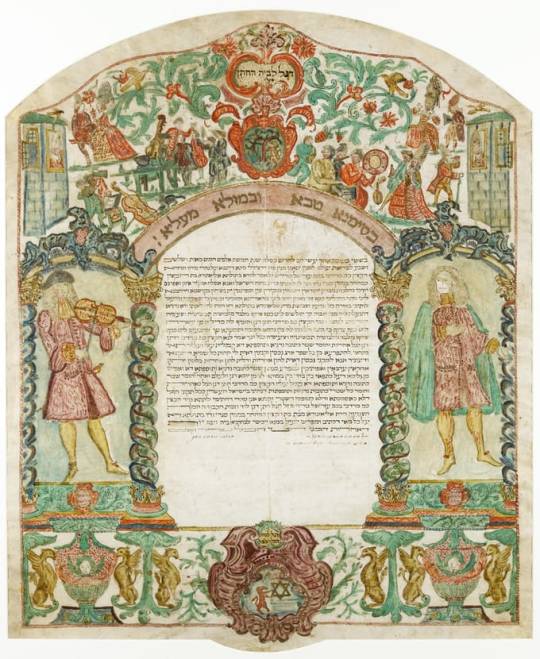

Photo

From the Jewish Museum, originally from Vercelli (Italy), Date:1776

Berger, Maurice et al. MASTERWORKS OF THE JEWISH MUSEUM. New York: The Jewish Museum, 2004, pp. 120-121, writes, “In Italy, ketubbot were commissioned by all Jews, including Sephardi, Ashkenazi, Levantine (from the eastern Mediterranean), and Italian- descendants of the old Roman community. Written on parchment, they usually featured lavish decoration, inspired by both Jewish and Christian art. For instance, the use of an archway to frame the text, as seen in this fine example from Vercelli, can be traced to the title pages of Hebrew printed books- northern Italy was a main center of Hebrew printing-but may also be linked to local architecture or sculpture. Figurative representation was also common in Italian ketubbot, although for centuries, most Jews had shied away from it because of their stern interpretation of the biblical prohibition against graven images. The inclusion of human figures, some allegorical and others portraying biblical or genre scenes, reflects a high degree of acculturation.

Other popular motifs in decorated Italian ketubbot include the signs of the zodiac and, as seen here, the emblems of the two families. The adoption of unofficial coats of arms was widespread among wealthy Italian Jews, in imitation of the practices of the local nobility Most ketubbot include a single shield, containing the insignia for both families, or just that of the groom, whose family usually commissioned the contract because he was obligated to furnish the bride-Eleonora- with a ketubboh. This example, however, features two separate emblems, possibly because the bride belonged to a family of prominent scholars, including Benjamin Segrè of Vercelli, who might have been her father. The coat of arms for the Segre family-a rampant lion facing right with a Star of David-is featured at the center of the lower border. No less distinguished was the Treves family, to which the groom-Mordecai, son of Azriel Treves- belonged. Their emblem-a rampant lion to the right of an apple tree-appears above the text at center, a prominent location, for the groom's family likely commissioned the document.

Issued in Vercelli, this ketubbah differs from other extant examples from the same Piedmontese city, characterized by an arcuated shape at bottom and a floral border. Although some Italian contracts depict the bride and groom, very few represent the wedding party-shown here in lavish costumes and hairdos-or the attendant musicians. Flirtatious interactions between various couples add a picaresque note, including a distinguished man with a cane peering through his spyglass at a lady at a window, at the upper right. A later example from Pesaro, dated 1853, at the Israel Museum ('79/339), also features a gathering of musicians and elegantly dressed couples, but the figures there were cut out from printed sources, painted, and pasted onto the parchment, instead of finely rendered, as seen here. The extravagance of examples such as this one might have prompted Italian rabbis to repeatedly enact laws limiting the amount of money that could be spent on the decoration of a marriage contract.

The secular nature of this ketubboh's decorative program, with figures of a musician and a young man elegantly dressed (perhaps a rendering of the groom?) in the niches often reserved for depictions of Moses and Aaron, indicates that it might have been the work of a Christian artist. Many other Italian examples, however, display a close relationship between text and image, with depictions of biblical scenes featuring heroes whose names were borne by the groom, the bride, or their fathers, with extensive use of Hebrew texts, attesting that they were decorated either by Jewish artists or by Christian makers under the strong guidance of their Jewish patrons.”

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Both Roman and Eastern rite Catholics celebrate the Church's Feast of the Transfiguration today, August 6, on its traditional date for both calendars.

The feast commemorates one of the pinnacles of Jesus' earthly life, when he revealed his divinity to three of his closest disciples by means of a miraculous and supernatural light.

Before his triumphal entry into Jerusalem, Christ climbed to a high point on Mount Tabor with his disciples Peter, James, and John.

While Jesus prayed upon the mountain, his appearance was changed by a brilliant white light, which shone from him and from his clothing.

During this event, the Old Testament figures of Moses and the prophet Elijah also appeared, and spoke of how Christ would suffer and die after entering Jerusalem, before his resurrection.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke all record that the voice of God was heard, confirming Jesus as his son (Matthew 17:5, Mark 9:6, Luke 9:35).

Peter and John make specific reference to the event in their writings, as confirming Jesus' divinity and his status as the Messiah (2 Peter 1:17, John 1:14).

In his address before the Angelus on 6 August 2006, Pope Benedict XVI described how the events of the transfiguration display Christ as the “full manifestation of God's light.”

This light, which shines forth from Christ both at the transfiguration and after his resurrection, is ultimately triumphant over “the power of the darkness of evil.”

The Pope stressed that the feast of the Transfiguration is an important opportunity for believers to look to Christ as “the light of the world” and to experience the kind of conversion, which the Bible frequently describes as an emergence from darkness to light.

“In our time too,” Pope Benedict said, “we urgently need to emerge from the darkness of evil, to experience the joy of the children of light!”

For Eastern Catholics, the Feast of the Transfiguration is especially significant.

It is among the 12 “great feasts” of Eastern Catholicism.

Eastern Christianity emphasizes that Christ's transfiguration is the prototype of spiritual illumination, which is possible for the committed disciple of Jesus.

This Christian form of “enlightenment” is facilitated by the ascetic disciplines of prayer, fasting, and charitable almsgiving.

A revered hierarch of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, the late Archbishop Joseph Raya, described this traditional Byzantine view of the transfiguration in his book of meditations on the Biblical event and its liturgical celebration, titled “Transfiguration of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ.”

“Transfiguration,” Archbishop Raya wrote, “is not simply an event out of the two-thousand-year old past, or a future yet to come. It is rather a reality of the present, a way of life available to those who seek and accept Christ’s nearness.”

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blessed Mother:

Not quite organized and I’m not trawling through Biblegateway to pull out all of my sources for the dozenth time, but here’s the gist of it.

Since Jesus Christ was fully God and fully man, Mary is the mother of God. God did not originate from her, nor did she precede God, but she bore God Himself in the second person of the Trinity. She is unique among all humanity for the way in which she was called to participate in the life of the Trinity as daughter of the Father, mother of the Son, bride of the Holy Spirit. This relationship is above anything that any other human ever has been or ever will be granted.

Sin is, at its simplest, rebellion against God. Grace is, at its simplest, participation in the life of God. The two are antithetical to each other. Where there is sin, there cannot be grace, and where there is grace, there cannot be sin. Original sin is inherited from our first parents, Adam and Eve, which means that human nature was in a state of rebellion against God and cut off from His grace. We are not able to be granted grace except through Christ: specifically, through the sacraments (Baptism, Reconciliation, Eucharist, and Confirmation especially), outward signs instituted by Christ for our benefit. However, the angel Gabriel hailed Mary as “Full of grace.” For that to be the case, she could not have been in a state of rebellion against God. She would have had to have been without original sin. Unlike the rest of us, who are born with original sin and brought into grace by baptism, Mary was brought into grace by God preserving her from original sin.

We are told that Christ submitted Himself to His parents, Mary and Joseph. This could only have been the case if, from the age of 12 years old to the age of 30, Mary and Joseph had never once asked anything of Him that was opposed to God’s will. For Mary (and Joseph!) to have been so aligned with the will of God speaks of a sanctity above that of any other biblical figure (with the obvious exception of Christ Himself.) Mary’s will was so aligned with God’s that Christ performed His first public sign — beginning the road to the Cross and elevating Marriage to a sacrament — at her request. The final recorded words we have of Mary’s are “Do whatever He tells you.” Whenever we look at Mary, she points us to God. Her soul magnifies the glory of the Lord.

We know that Jesus had no siblings because he scolded the Pharisees for allowing children not to take care of parents in their old age, but He entrusted Mary’s care to John while on the cross. This would have been wrong if Mary had had any other children. He also told Mary to behold her son. Giving the one apostle at the foot of the cross to Mary is also an entrustment of the Church to her: she is the mother of all Christians, just as Christ is our Brother and God is our Father.

The ark of the covenant bore within it signs of God’s covenant with Moses: Aaron’s staff, the tablets that the 10 commandments were inscribed upon, and manna: the power of the priesthood, the law, and the bread from heaven. Mary bore within her the new priest, the new law, and the bread of life from heaven. The ark of the covenant was so holy that even to lay a hand on it meant death. David, in joy, danced before the ark, and, in awe, asked “Who am I that the ark of the Lord should come to me?” John, in joy, leapt in the womb at the sound of Mary’s voice, and Elizabeth, in awe, asked “Who am I that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” If the old ark of the covenant was too holy for the touch of man, how could the new ark of the covenant be less holy?

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jehanna / ジャハナ, Ismaire / イシュメア, and Joshua / ヨシュア

Jehanna (JP: ジャハナ; rōmaji: jahana), romanized as Jyahana in Japanese, is the name of the desert kingdom ruled by Queen Ismaire in Fire Emblem: The Sacred Stones. Gehenna (JP: ゲヘナ; rōmaji: gehena) is the name of the valley in which the Old City of Jerusalem is found within. According to the Bible, some kings of Judah would have child sacrifices done at Tophet, a pagan shrine in the valley, causing the prophet Jeremiah to curse the valley. Later, Jewish rabbinic traditions would adopt the Hebrew name of the valley, Gehinnom, as a realm of punishment for the wicked after death, compared to the more general "underworld" of Jewish tradition, Sheol. It is believed that from Gehinnom, Islam would have Jahannam (ジャハンナム), their faith's land of punishment for evildoers in the afterlife. Both Gehinnom and Jahannam are said to burn their sinful with unending fires, which may have influenced the scorching desert location of Jehanna and the burning of Jehanna Hall. Of course, the arid environment also likely is due to the concepts of Gehenna and Jehannam coming from two major religions from the Middle East, typically associated with dry, desert land.

Ismaire (JP: イシュメア; rōmaji: ishumea), romanized as Ishumare in Japanese, is the Queen of Jehanna. She most likely gets her name from the Biblical figure Ishmael (JP: イシュマエル; rōmaji: ishumaeru), the first child of the patriarch Abraham. Abraham and his wife Sarah were unable to bear a child together, despite God's promised covenant claiming they would have numerous descendants. Sarah believed that the resolution to be for Abraham to lay with her handmaiden Hagar, and with her Ishmael would be born. However, he would not be the child promised to Abraham - that would be Isaac, born from the believed-to-be infertile Sarah. Tension between Sarah and Hagar had been brewing since Ishmael's birth, culminating in the servant and her son being ordered to leave, left to wander the deserted wilderness. However, God promised Abraham that, as Ishmael was still his child, he would make a people as well - the Ishmaelites. According to Muslim tradition, the prophet Muhammad was a descendant of Ishmael. Ishmael would be elevated in status, considered one of the Islamic prophets.

Joshua (JP: ヨシュア; rōmaji: yoshua), romanized as Jhosua in Japanese, is the vagrant prince of Jehanna. In the Old Testament, Joshua of the tribe of Ephraim was an aide to Moses after the exodus from Egypt. He joined Moses in the first ascent of Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments from God. After the Israelites reached the borders of Canaan - the land promised to them by God, Joshua was sent as one of their twelve spies to assess the land and its inhabitants over 40 days. Joshua and Caleb reported favorably, believing that with the aid of God they could take the promised land from the Canaanites. The other spies instead exaggerated the strength and fortifications of the peoples of the land, convincing the Israelites that God lied to them and it was impossible for them to take the land. As punishment, God would make the people wander for 40 years, until all of that generation, bar Joshua and Caleb, had passed. After Moses' death, Joshua was selected by God to be the head of the Israelites, and blessed him with invincibility. The Book of Joshua then tells of how Joshua led his people in the conquest of the land of Canaan.

Ismaire and Joshua ruling over a desert kingdom is likely based on their namesakes both having wandered through the desert before founding a nation. Similarly, Joshua's wanderlust may be loosely based on the 40 years in the desert before the Israelites could enter the promised land. Joshua's ability to promote to the Assassin class may be in reference to the biblical Joshua's role as a spy - a role the series often gives to characters of the Thief and Assassin classes.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Influence of Biblical Mothers

From Eve, the first mother in the Bible, to Mary, the mother of Jesus, mothers have played a significant role in shaping the lives of their sons. The influence of these Biblical mothers can be seen throughout scripture, and their examples continue to inspire and encourage us today. In this blog post, we will explore the influence of Biblical mothers on their sons and the lessons we can learn from their stories.

Eve: The Mother of All Living

Eve is the first mother in the Bible, and her influence can be seen in the lives of her sons Cain and Abel. Although her story is one of tragedy and loss, Eve’s faith in God and her love for her sons provide a powerful example of the importance of family.

Sarah: The Mother of Isaac

Sarah was a woman of great faith who believed in God's promises, even when they seemed impossible. Her influence on Isaac can be seen in his own faith and trust in God, as well as in his obedience to God's will.

Rebekah: The Mother of Jacob and Esau

Rebekah played a pivotal role in the lives of her sons Jacob and Esau. Her influence can be seen in Jacob's cunning and resourcefulness, as well as in his love for his family. Her actions also had consequences, however, as her favoritism towards Jacob led to conflict and division in the family.

Jochebed: The Mother of Moses

Jochebed is a lesser-known figure in the Bible, but her influence on her son Moses was profound. She demonstrated great courage and faith in God, risking her life to save her son from Pharaoh's decree to kill all Hebrew baby boys. Her example of faith and trust in God set the foundation for Moses' own relationship with God and his leadership of the Israelites.

Hannah: The Mother of Samuel

Hannah's influence on her son Samuel can be seen in his devotion to God and his role as a prophet and judge in Israel. Hannah's faithfulness to God, her prayers for a son, and her willingness to dedicate him to God's service serve as an example of the power of prayer and devotion.

Mary: The Mother of Jesus

Mary is perhaps the most well-known of all Biblical mothers, and her influence on her son Jesus cannot be overstated. Her faith, obedience, and humility set the foundation for Jesus' own ministry, and her role as the mother of the Messiah continues to inspire and encourage believers today.

The stories of these Biblical mothers and their influence on their sons provide us with valuable lessons for our own lives. We can learn from their faith, devotion, and love for their families, as well as from their mistakes and shortcomings.

We can learn the importance of faith in God's promises, even when they seem impossible. We can learn the power of prayer and devotion, and the importance of setting a good example for our children. We can learn the consequences of favoritism and division in families, and the importance of treating all of our children with love and respect.

Above all, we can learn from the example of these Biblical mothers to be faithful and devoted followers of God, and to raise our children to love and serve Him as well.

0 notes

Text

The Christianity that eventually emerged from the tradition of Paul, Augustine, Anselm and Aquinas had strong Judaic elements. It spoke of faith, hope, charity, righteousness, love, forgiveness, the dignity of the human person and the sanctity of life. It valued humility and compassion. It spoke of a God who loves his creatures. But it also contained strands that were undeniably Greek and in striking contrast with the way Jews read the Hebrew Bible. The following are some of them.

The first and most obvious is universality. Judaism is a principled and unusual combination of universality and particularity: the universality of God, and the particularity of the ways in which we relate to God. The God of Israel is the God of all humanity, but the religion of Israel is not, and is not intented to be, the religion of all humanity. You do not have to be part of the Sinai covenant, or even the covenant of Abraham, to reach heaven and achieve salvation.

Pauline Christianity rejected this. The upside of this is its inclusivity, expressed most famously in Paul’s striking statement, ‘There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female’ (Galatians 3:28). The downside is its denial of any other route of salvation. Extra ecclesiam non est salus: ‘Outside the Church there is no salvation.’ Universality is supremely characteristic of Greek thought in the classic age between the sixth and third pre-Christian centuries (though of course it was not applied in their religious understanding). Above all it is the legacy of Plato, who utterly devalued particulars in favour of the universal form of all things. For Plato truth is universal and eternal or it is not truth at all. In that sense, Paul and Plato are soulmates.

The second is dualism. To a far greater extent that Judaism, Christianity after Paul develops a series of dualisms, between body and soul, the physical and the spiritual, earth and heaven, this life and the next, with the emphasis on the second of each pair. The body, says Paul in Romans, is recalcitrant. ‘What I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do’ (Romans 7:15). There is nothing like this in Jewish literature. To be sure there is the ‘evil inclination’, but no suggestion that because of our embodied condition we are slaves to sin. The entire set of contrasts — soul as against body, the afterlife as against this life — is massively Greek with much debt to Plato and traces of Gnosticism. Paul’s occasionally ambivalent remarks about sexuality and marriage also have no counterpart in mainstream Judaism.

Third is the Pauline reinterpretation, one of the most radical in the history of religion, of the story of Adam and Eve and ‘the Fall’, and the consequent tragic view of the human condition. There is no such interpretation of the passage in the Hebrew Bible. According to Judaism we are not destined to sin. In the very next chapter, before Cain murders his brother Abel, God reminds him of his essential freedom: ‘Sin is crouching at your door; it desires to have you, but you can dominate it’ (Genesis 4:7). The collective forgiveness of humankind occurs, in the Hebrew Bible, after the Flood. ‘Never again,’ says God, ‘will I curse the ground because of humans, even though every inclination of the human heart is evil from childhood’ (Genesis 8:21).

The human tragedy as described by Paul is more Greek than Jewish, and as for the idea of inherited sin, it is already negated in the sixth pre-Christian century by both Jeremiah and Ezekiel. Of course, in Christianity, tragedy is avoided by salvation: but salvation in this sense, the existential delivrance of the human person from the grip of sin, does not exist in Judaism. We choose. Sometimes we choose wrongly. We atone (in biblical times through the Temple service, post-biblically by repentance) and God forgives.

Fourth is the potential for the separation, unknown in Judaism, between ‘faith’ and ‘works’. In Judaism the two go hand in hand, Faithfulness is a matter of how you behave, not what your believe. Believing and doing are part of a single continuum, and both are a measure of a living relationship characterised by loyalty. In general one of the great differences between classical Greek and Hebraic thought thought is the immense emphasis in the latter on the will. We are, on a Jewish view, what we choose to be, and it is in the realm of choice, decision and action that the religious drama takes place. The Greek view emphasises far more the role of fate and the futility of fighting against it. Under its influence Christianity became more a religion of acceptance than protest — the characteristic stance of the Hebrew prophets.

The fifth and most profound difference lies in the way the two traditions understood the key phrase in which God identifies himself to Moses at the burning bush. ‘Who are you? asks Moses. God replies, cryptically, Ehyeh asher ehyeh. This was translated into Greek as ego eimi ho on, and into Latin as ego sum qui sum, meaning ‘I am who I am’ or ‘I am he who is’. The early and medieval Christian theologians all understood the phrase to be speaking about ontology, the metaphysical nature of God’s existence. It meant that he was ‘Being-itself, timeless, immutable, incorporeal, understood as the subsiding act of all existing’. Augustine defines God as that which does not change and cannot change. Aquinas, continuing the same tradition, reads the Exodus formula as saying that God is ‘true being, that is being that is eternal, immutable, simple, self-sufficient, and the cause and principal of every creature’.

But this is the God of Aristotle and the philosophers, not the God of Abraham and the prophets. Ehyeh asher ehyeh means none of these things. It means ‘I will be what, where, or how I will be’. The essential element of the phrase is the dimension omitted by all the early Christian translations, namely the future tense. God is defining himself as the Lord of history who is about to intervene in an unprecedented way to liberate a group of slaves from the mightiest empire of the ancient world and lead them on a journey towards liberty. Already in the eleventh century, reacting against the neo-Aristotelianisn that he saw creeping into Judaism, Judah Halevi made the point that God introduces himself at the beginning of the Ten Commandments not as God who created heaven and earth, but by saying, ‘I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery.’

Far from being timeless and immutable, God in the Hebrew Bible is active, engaged, in constant dialogue with his people, calling, urging, warning, challenging and forgiving. When Malachi says in the name of God, ‘I the Lord do not change’ (Malachi 3:6), he is not speaking about his essence as pure being, the unmoved mover, but about his moral commitments. God keeps his promises even when his children break theirs. What does not change about God are the covenants he makes with Noah, Abraham and the Israelites at Sinai.

So remote is the God of pure being — the legacy of Plato and Aristotle, that the distance is bridged in Christianity by a figure that has no counterpart in Judaism, the Son of God, a person who is both human and divine. In Judaism we are all both human and divine, dust of the earth yet breathing God’s breath and bearing God’s image. These are profoundly different theologies.

— Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l, in The Great Partnership: God, Science and the Search for Meaning

176 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have opinions about The Prince of Egypt musical adaption and you’re going to listen to them: An Essay

So, quick disclaimer: The Prince of Egypt is one of my favourite movies of all time. The casting, the music, the animation, I think it’s one of the top-tier movies that have ever been made. I went into seeing the London West End production of PoE with a full expectation that nothing I saw on stage would ever live up to how much I love the movie. I was fully aware there are plenty of limitations to what can be shown live on a stage with human actors and props.

That being said, I was enormously disappointed with how the whole thing was handled.

The Good

Now before I launch into a whole tirade of what I didn’t like about the production, it does behoove me to say what I think they did do well.

The casting of the role of Moses was done fantastically, as was Miriam, Tzipporah, and Yocheved. The swings and the ensemble were really engaged and well placed, going through lots of quick changes to go from Hebrews to Egyptians to Midianites and back.

The two Egyptian queens, wifes of Seti and Ramses, are actually given names, lines, and character beyond being simply tacked onto their respective kings. We get to see how they feel about the events happening around them, and there’s even a scene where Ramses meets his wife and courts her, whereas in the movie, she stands in the background and says nothing. This is one of the areas I was hoping the musical, which would naturally have a longer run-time, would expand on, and I was pleased to see the opportunity was taken.

Light projections on enormous curtains were used to very good effect, taking us instantly inside the walls of the palace and then out to the desert.

Over all, the work was really put in to be engaging and emotional, and the orchestra really worked to deliver the right musical beats.

One of two stand out scenes as being done very well was the opening “Deliver Us”, which included a bone-chilling moment of Egyptians separating a mother and her baby, with her screams as she’s dragged off-stage, and the blood on the guard’s sword. It really brings home the fear as Yocheved tries to lead Aaron and Miriam to the river with her, not to mention Yocheved’s actress nailed the lullaby.

The second was at the other end of the show, “When You Believe” was beautifully performed by the whole cast, though it was somewhat stunted by what came before...

The Bad

Oh boy.

So the main problem with this show is not the music, not the staging, not even that sometimes the ensemble was a little off-beat (the lai-lai-lai section in Though Heaven’s Eyes comes to mind). Any mistakes there can all be forgiven, since sometimes things just happen in live performance, someone’s a bit off or something’s just not possible to do on the budget allotted.

The problem is in the script.

The Prince of Egypt movie is a story that stands not only on the shoulders of its fantastic music and visuals, but also on its emotive retelling and portrayal of the characters within - mainly Moses and Ramses. And while the stage musical does spend a lot of time with the two mains, it neglects two other, incredibly important characters.

Pharaoh Seti, and God.

In the movie, Seti strikes an intimidating figure. He is old, hardened, and wise in the ways of ruling his kingdom - and is voiced by Patrick Stewart, who brings his A-game to the role. Both Moses and Ramses admire him and look up to him immensely as young men, and the relationship he has with both of them deeply informs their characters as the story progresses. It’s from Seti that Moses learns that taking responsibility for your actions is the respectable thing to do (and later, the true horror of having your idol turn out to be not what you think), and it’s from Seti that Ramses takes a huge inferiority complex.

There are two lines that Seti gets in the movie, one spoken to Moses, and one to Ramses. These two lines define Moses and Ramses’ actions later on in the story:

To Ramses - “One weak link can break the chain of a mighty dynasty!”

To Moses - “Oh my son... they were only slaves.”

Guess which two lines are absent from the musical?

One Weak Link is turned into an upbeat song, rather than shouted at a terrified and cowed young Ramses. Instead of being openly a traumatic, internalised moment of negative character development for Ramses, it’s treated as a general philosophy that Seti passes down to his son. Instead of a judgement that is hung over Ramses’ head like a sword of Damocles, lingering in his mind through the whole story and coming up in a shouted argument with Moses later, it’s said and then moved on from.

The “they were only slaves” comment, on the other hand, is absent entirely. This changes Moses’ relationship with Seti enormously, as well as his relationship with the Hebrew people. Upon finding the mural depicting the killing of the slave children, Moses is appropriately horrified, and Seti shows up to comfort him and defend his terrible actions. Moses leaves this interaction... and then sings about how this is indeed all he ever wanted! He has no moment of horrific realisation that his father thinks of the slaves as lesser, as lives that can be thrown away. This means that the scene where he kills the guard doesn’t lead into a discussion of morality with Ramses as he runs away, but rather Moses breaking down about his heritage as though it’s a negative, instead of something he’s realised is just as valuable as his life as an Egyptian. Instead of Moses being shown as having a strong moral core that protests against the idea of any life being lesser, he bemoans his Hebrew blood loudly, and makes little mention of the man he killed. His issue that causes him to run away is being adopted, rather than his guilt that he’s a murderer, and nothing Ramses can say will change it.

Later on, we don’t see Ramses express this opinion either (in the movie - M:”Seti’s hands bore the blood of thousands of children!” R:“Hah, slaves!” M:“My people!”) so it seems the core reasoning for the necessity of the extremes God had to go to in order to convince Ramses to let the Hebrews go is completely gone.

Which leads us into God Himself, as a character.

God is a tricky topic in general. He is hard to talk about as a concept and as a character, and even harder to depict in a way that won’t offend someone. The Prince of Egypt movie always struck me as a very good depiction of the Old Testament God - vengeful and strong-willed, commanding and yet nurturing, capable of great mercy and great cruelty in one fell swoop. God is incredibly present in the story, a character in and of Himself, speaking with Moses rather than simply commanding him. The conversation at the Burning Bush is bone-chillingly beautiful. Moses is allowed to question, he’s allowed to enquire, he’s allowed to express how he feels about God’s choice, and God is given the chance to respond (and reprimand, and comfort).

In the musical, the Burning Bush scene lasts all of two minutes, during which God (the ensemble cast, acting as one moving flame, speaking in unison) monologues to Moses, and Moses is not given room to question, talk to, or build a relationship with God. Later on, once some of the plagues have gotten underway, Moses rails against God, flinches in his resolve, and tries to back out... and God says nothing. It’s Miriam and the spirit of Yocheved that convince Moses to keep going. As a character, God is nearly absent. Even when it comes to calling upon the Plagues, or parting the Red Sea, God’s voice is absent. Moses does not pray. He does not even use the staff that God encouraged him to pick up as a symbol of his becoming a shepherd of the Hebrews out of Egypt.

It’s these little changes, these little absences of such vital lines and presences, that ends up changing the whole vibe of the show. Seti is more like a dad than an emotionally distant authority figure, and God is more like an emotionally distant authority figure than a character at all. Ultimately, the whole feeling that one is left with at the end…

The Ugly

… is that the script doesn’t like God, or religion in general.

A bold statement to make, considering the source material is one of the central biblical stories in EVERY Abrahamic religion. Moses as a figure is considered so important and close to god, that The Prince of Egypt, even with its sensitive portrayal, cannot be aired in a number of Islamic states, because it’s considered disrespectful to depict any of the prophets, especially an important one like Moses. Moses is arguably the MOST important prophet in the Jewish canon.

However, I haven’t highlighted one of the most noticeable script changes - the elevation of Hotep, the high priest, to main antagonist.

In the original movie, Hotep is a secondary villain, a crony to the Pharaohs, bumbling and snide and two-faced. He and his fellow priest Hoy are there primarily to juxtapose how charlatans can control power through flattery and slight of hand, reassuring Ramses that Moses’ miracles are merely magic the same as what they can do. They even get a whole villain song, “Playing With The Big Boys” which is a lovely deconstruction of lyrics vs visuals, where while the priests boast that their gods and magic are much more powerful, in the background the staff, transformed into a snake by god, devours and defeats the priests’ snake handily. The takeaway from the song is that God’s power is true, and doesn’t need theatrics.

It’s a good little nugget of wordless world building. And it is completely absent from the stage musical, with only a vague reference to the chant of all the gods names.

Hoy is gone, and Hotep is the only priest. He actively speaks out against the Pharaoh, boasts about having all the power, and is played as bombastic and proud. He’s a wildly different character, even threatening Ramses at one point. In the end, it’s shown that Ramses won’t let the Hebrews go not because he has inherited his father Seti’s cruel attitude towards the lives he considers beneath him, but because he is being actively bullied by the priest, and will lose his power and credibility if he doesn’t do as he’s told. Ramses is even given a whole song about how little power he really has. The script desperately wants us to feel sorry for Ramses’ position and hate the unrepentantly, cartoonishly evil priest.

That’s another matter as well - a LOT of time is dedicated to making the Egyptians more human and sympathetic, portraying them as largely ignorant of the suffering beneath them, rather than actively participating in slavery. Characters speak out of turn without regard for formality and class, even to the royal family. They are casual, chummy even. And this would be fine - in fact, it’s good to have that sort of third dimension to characters, even ones who are doing reprehensible things, to show the total normalcy and banality of evil - if it were not for the fact they still include a completely open-and-shut case of evil right next to them.

Hotep has no redeeming features. And on the other side, God is barely present, certainly not in a relatable context. Moses has several lines about how cruel and unnecessary God’s plagues are - and you know what, in this version, they are unnecessary! Ramses is not the stone-hearted ruler that his movie counterpart is, he has no baggage over being a potential failure, because it was never really given to him in the same way! By taking away Ramses’ threatening nature, numbers like the Plagues lose half their appeal, as the back-and-forth ‘you who I called brother’ lines between Moses and Ramses are completely absent. Moses is faithless, and is less torn between the horror of what he’s doing and the necessity of it for the freedom of his people, and more left scrabbling for meaning that he doesn’t find. And the only thing hanging over Ramses is Hotep nit-picking everything he does and threatening him, which is considerably less compelling than the script seems to think it is.

This is best exemplified at the end, when all the issues come to a head. The angel of Death comes and takes the Egyptian first borns (which was actually a well done scene), and the Hebrews leave to a rousing rendition of When You Believe. But then we cut to Ramses and Hotep, with Hotep openly threatening to revolt against the Pharaoh - whom was believed, especially by the priesthood, to be a living god! Hotep is so devoid of redeeming features he cannot even be trusted to stand by his beliefs! - unless Ramses agrees to chase after the Hebrews. Reluctantly, Ramses is badgered into the attempt.

Back with the Hebrews, Moses parts the Red Sea… not with his faith, not by praying to God for another miracle, not even by using his staff as in the most famous scene of the movie… but by holding out his hand and demanding the ‘magic’ work. Setting aside the disrespect of Abrahamic religions to call one of the most famous miracles “magic” (and my oh my, if there was a fundamentalist of any religion in the audience they might have gasped to hear it), it again belittles the work of God, and puts all the onus on Moses, not as a conduit for God’s work, but as the worker himself. Then, the Egyptians arrive in pursuit, lead by Hotep, not Ramses. Moses sends the Hebrews through first, lead by Miriam, and stays behind with Tzipporah… to offer his life in penance to Ramses! The script has completely stripped both Ramses and Moses of their convictions towards their causes, and Moses cannot even stand by his decision to lead his people.

Then, in a moment of jarring melodrama, Moses has a sudden vision that Ramses, his brother, will one day be called Ramses the Great (an actual historical Pharaoh who reigned 1279-1213 BCE). There is no historical evidence that this was the Ramses that ruled over the Hebrews (there are 11 Pharaohs called Ramses through the history of Ancient Egypt), and maybe if the scene was acted a little better, it wouldn’t have been so sudden or jarring. Even more jarring, is that then Hotep arrives with the rest of the army, and Ramses refuses to lead the charge into the parted sea. Hotep does so himself, and is the one to have the final dramatic moment, being crushed under the water.

The Takeaway

After watching the show, I’m afraid I could never recommend it as either a play, an adaption, or even as a faithful retelling of a bible story. Its character drama isn’t compelling enough to be good as a standalone play, with it two main characters declawed and their core motivations reduced to a squabble between brothers rather than a grand interplay between two cultures and ideas and trauma handed down from their father. As an adaption of the movie it’s upsettingly bad, with grand numbers like the Plagues rendered piecemeal and fan favourites like Playing With The Big Boys missing entirely. As a retelling of the bible story, it’s insulting, completely cutting God out of the equation, taking no opportunity to reintroduce Aaron as an important character (which he was, in the bible, as Moses was a notoriously bad public speaker, with a stutter, and Aaron often interpreted for him) and more importantly, completely erasing God’s influence from the narrative.

I don’t know who this show was… for, in that case. If it wasn’t for drama lovers, movie fans, or people of the faith, then who the hell was it for? Why change such a critically acclaimed and well-beloved story? Why take away all these defining moments? If you wanted to tell a story about how religion is the true evil, how God can command people to do terrible things, and how those who uphold organised religion like Hotep are unrepentant, one-dimensional monsters… why would you tell that through the Prince of Egypt?

Underwhelming at best, infuriating at worst… just watch the movie. Or read Exodus. At least the Bible’s free.

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

OC Bio: Defenders Saga

Name: Madison Marie Murdock

Name Meaning: Madison: “Madison is a surname of English origin, which has become a popular given name in the United States. Madison, commonly spelled Maddison in Northeastern England, is a variant of Mathieson, meaning son of Matthew”//Marie: “The name Marie also has Hebrew origins being derived from Miryam, which is believed to come from the Egyptian element "myr," meaning "beloved." Miryam is also the biblical name of Moses's sister from the book of Exodus and is believed to mean "rebellious" and "wished-for child."”

Nickname(s): Maddy, Mads, kiddo, shorty, gremlin, Devil’s Daughter (ironically),

Alias(es): n/a

Occupation: Student, legal assistant (unofficially)

Alignment: Neutral Good//INTJ-T

Gender: Female

Sexuality: —

Age/Birthday: March 13, 2002

Height: 5’6”

Hair Color/Type/Length: Brown/Wavy/Mid-Shoulders

Eye Color: Brown

Body Markings: —

Family: Matthew Murdock (Father), Rebecca Cole (Estranged Mother), Foggy Nelson (“Uncle”)

Love Interest(s): —

Birthplace: New York, NY

Languages: English, Spanish, Braille, Basic ASL

Skills/Powers: childhood karate/boxing lessons, can read braille, honors student, extensive legal knowledge, basic medical skills, preparedness

Likes: arguing, being right (all the time), cartoons, free food, ice cream, hanging out with Foggy, violence (occasionally), sarcasm

Dislikes: Daredevil, homework, when Matt doesn’t come home, when Matt needs her to patch him up, when Matt tells her “no,” Elektra, drama

Catchphrase: “bitch and a half”

Backstory: Born when Matt was just seventeen years old, Maddy has always been his inspiration. Her mother, Rebecca, wanted nothing to do with her after she was born and that was just fine with Matt, good riddance. He became her sole caregiver and protector, naming her himself: Madison Marie Murdock, heavily inspired by the Bible he stood by. And his matching alliterated name. Madison meant “child of Matthew,” and later he would find Marie, “rebellious child,” just as fitting for his daughter.

Madison was eight years old when her father started law school, and due to “unique circumstances,” was able to live in the dorms with her dad and his roommate, Foggy Nelson, who thought she was a feral gremlin at first, but grew to love her as time went by, even earning the title “Uncle Foggy.” Matt enrolled Maddy in karate classes to keep her busy, active, and supervised after her school days while he was in his own classes, befriending her deaf classmate, Maya, while in the dojo.

She grew closer to Foggy in the months after Matt had met Elektra, creating a burning hatred for her dad’s new girlfriend. But her and Foggy bonded over reposted cartoons on YouTube and sharing famous college student snacks like uncooked ramen and grilled cheese made with an iron. They were perfect nights to look back on, but when Matt and her split, he was a mess. It was Maddy who inspired him to crawl out of bed and finish his degree, sitting next to him while he worked and learning with him (comprehension of the subjects wasn’t always there, but still she learned).

Sooner or later, Matt and her moved back to Hell’s Kitchen and it was a brand-new ballgame. In more ways than one. New school, new apartment, Nelson & Murdock, Devil of Hell’s Kitchen. And it didn’t take her long to figure out that last one. Needless to say, she was not all that happy.

Faceclaim: Bailee Madison

9 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re: bethyl... Are you working a ‘seven years for Rachel to get Leah instead’ angle? 👀 (Trying to figure out from your semi-cryptic message on your other blog)

Anon!

When I saw the name I went into hyperdrive. I love all the Old Testament allusions in The Walking Dead. Sometimes they’re overt, sometimes they’re implied. This one feels like both. And now I’m just going to go into it:

Season 10 Spoilers Ahead

Reading Daryl and Beth Through a Biblical Lens: Who is Leah?

FIRST: Who is Jacob? Jacob and his brother Esau are important characters in the book of Genesis. I have thought of Daryl as a Jacob character before. Jacob was one of the three Biblical Patriarchs of the Israelites, born in Canaan. He’s a patriarch for his people at the beginning of a new world, a younger brother, “the good son,” cunning, brave, but more a lover, a traveler, not a fighter like his older brother Esau. He sleeps alone on the riverbanks, has visions, wrestles an angel all night long and never gives up. When Jacob’s mother, Rebecca, was pregnant, she asked God why she felt so unwell. God told her that she was carrying fraternal twins, and that they were fighting in the womb, and that they would fight forever. He told her that one day, “the elder would serve the younger.” Esau was born first, then Jacob, holding onto his heel. Jacob means “heeled” or “supplanted,” superseded, undermined. Like Daryl, living in the shadow of his brutish older brother who will hamper him for much of his young life, but who he is destined to overtake.

Jacob and Esau. Merle, like Esau, is a big, mean brute. He is even described as being covered in red hair. Esau itself means “red” in Hebrew, echoed by Merle’s “redneck” past. By far the less intelligent, the less compassionate, a hawk where his younger brother is a dove. They are patriarchs for separate nations (in the Bible: the Israelites and the Edomites). In the Bible, Jacob flees Canaan after his brother threatens to kill him for usurping his birthright (which Esau “sold” to him, btw, for a simple bowl of stew). Similarly, Daryl must beat or outrun or escape his older brother’s abuse, sometimes directly, sometimes metaphorically, and eventually Merle is at his mercy and “serves” him in the end--re: “the elder will serve the younger”--by sacrificing his life to save Daryl and his people from the Governor.

Jacob’s Ladder. There are two episodes of TWD with big Jacob’s Ladder themes, in which Daryl is directly involved: “Chupacabra” (2.5) and “Chokepoint” (9.13). Jacob’s Ladder refers to a vision that Jacob has of a tall staircase leading up to heaven, with angels climbing up and falling down. The angels that fall represent the coming, various exiles of the Israelites, falling down to signal that the Jews will overcome; however, one angel, representative of the Edomites, or Esau’s descendants, gets very close to the top, signaling Jacob’s fear that he/his people will never be able to overcome his older brother’s power. God promises Jacob from the top of the ladder that Esau, too, will eventually fall.

The season 2 episode “Chupacabra" shows Daryl falling down and then climbing up a steep hillside, injured, to a bright light at the top, while battling visions of his angry big brother, who he ultimately vanquishes. In “Chokepoint,” Daryl fights Beta (also a total David and Goliath allusion) at the top of a high tower, and he pushes Beta down a steep elevator shaft. Jacob and his people, the Israelites, like Daryl and his group, must overcome numerous trials and exiles, escaping their captors, again and again.

Meanwhile it is interesting, though perhaps purely in my own self-interest to note that the little house on the way to Haran where Jacob slept and had his vision of the ladder, he named Bethel, aka “House of God.”

Rachel vs. Leah. And then there are Jacob’s two wives: Rachel and Leah. This is where my Jacob comparison starts to come together on a new level. This Jacob character gets paired with a Leah? Like, no. In Genesis, after leaving Canaan, while on the run from Esau, Jacob goes to his uncle Laban’s farm in Haran. Laban has two daughters: Leah the eldest and Rachel the youngest. Rachel is described as a fair and beautiful shepherdess who Jacob falls in love with. Jacob promises Rachel’s father that for seven years he will work for him, and in return, he will be allowed to marry Rachel.

BUT

After seven years, on their wedding night, Jacob is tricked into marrying Leah instead. Leah is older and described as having sad or “soft” eyes. She appears to him in a veil with her true identity concealed. After the wedding, Jacob is obviously upset. He is in love with Rachel. He waited seven years to marry Rachel. But her father thought he should marry the older girl instead. Laban agrees to then let Jacob marry Rachel as well, if he works on his farm for seven more years. Jacob agrees.

The story goes on. Leah has many children with Jacob, but Rachel struggles to conceive. Still and always, Jacob favors Rachel, his first love. Eventually, Rachel has a son with Jacob--Joseph, who, as Jacob’s favorite son, Jacob would later gift with the “technicolor dream coat.” Even after Rachel’s death, Jacob does not favor Leah. He takes up with Rachel’s handmaiden instead.

In this story, Beth will represent the Rachel character: A fair and beautiful shepherdess, younger sister, and farmer’s daughter. Like Beth, Rachel is also characterized as outspoken and brave, having questioned God’s treatment of the Israelites, and questioning with such force, that God responded to say that basically, he was sorry, and they would eventually make it back to their homeland. Rachel is a classically maternal character who famously cries for and defends her children.

Timeline. The timeline is suspicious. Seven years Jacob waited for Rachel, only to, as you put it “get Leah instead.” If we look at the approximate timeline for The Walking Dead, we can deduce that, at the time of season 10c, and our very convenient Leah spoilers, roughly 7-8 years have passed since the prison's fall and the subsequent events of “Still” and “Alone.” If we apply this to the Daryl/Jacob and Beth/Rachel lens, we can deduce that Daryl has waited for Beth for ~seven years and is now being served, in a surprise twist, someone named Leah. Someone we have never met before, who, up until now, has been “in disguise.”

Biblical Allegory. It’s worth mentioning that The Walking Dead uses a lot of Biblical imagery and allegory in its storytelling. Whether it’s Rick as Abraham to Carl’s Isaac, or smaller examples such as with characters like Samuel (prophecy kid) or Aaron (Moses’s spokesman). There are many more. The trials and tribulations of Rick’s people can also be looked at through the same lens as the trials and tribulations of the Israelites in Exodus. I mean, think frogs and pestilence, contaminated rivers, diseased livestock, massive storms. Daryl is not a character in the comic books, and neither is Beth. Their characters and character arcs would make sense as extensions of the showrunners’ obvious love for Old Testament storytelling and symbolism. Jacob’s deception and love for Rachel is a good story, and tbh, it kind of makes sense here?

Conclusion. This is a Biblical analysis of a character arc. I’m not trying to argue that this is foreshadowing Beth’s return. Please don’t quote me on that. BUT: it can be read that way, if you want to use this as meta-analysis of how the show sets patterns for its storytelling. I do recall hearing things about how the showrunners possibly “cancelled’ Bethyl at the last minute, due to backlash over the age difference. If they wanted to make her into Rachel instead, bring her back seven years later, so that she’s no longer nineteen and has lived a little in the world, without Daryl, and to double down on the Daryl/Jacob allusions, while also solving the “Beth is too young” conundrum, I think that would be.....interesting, to say the least. If it is intentional, and I’m not saying it is, but if it is, it’s possible it was planned farther in advance as well? Who knows.

#the walking dead#daryl dixon#beth greene#bethyl#daryl x beth#team delusional#team defiance#td#beth greene lives#twd meta#biblical analysis

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Top 10 Things I Love About Supernatural

It’s been almost half a year since the show ended and now that the dust has settlIed, I just want to list ten reasons I love this show. Despite it’s flaws, it’s been quite the ride.

1. Team Free Will

When I first got the idea to make this list, I originally planned on doing entirely separate entries for “Sam & Dean” and “Destiel”. Except then I wanted to pay tribute to “Sastiel”. And then I wanted to do an entry for “Team Free Dads”. By that point, I was already halfway through the list and I hadn’t even moved on from the main characters. A few months ago, I made a post about why I love every single pairing in this group. Obviously, Sam and Dean are a legendary duo. Obviously, Dean and Cas have an unparalleled story. Obviously, Sam and Cas are an underrated team. As for Team Free Dads, I’ve always had a soft spot for father/mentor figure characters and and all three tackle the role in different ways. I love Jack, too. I love how everyone in this bizarro family is “broken” in some way. We’ve got the Allistair’s prized pupil, the spawn of satan, the boy with demon blood, and the angel who nearly obliterated all of heaven. But they help each other heal by being supportive and seeing the good in each other. They all love each other so deeply and when together, nothing can stand in their way. Not Michael, not Lucifer, and not God himself. They tore up the book and wrote their own story. And it was a pleasure to watch it all unfold.

2. The Suppporting Characters

To list every single supporting character I have loved and lost in this show would take way too long. I don’t know if it’s the writing or acting performances, but I love pretty much every single supporting character on this show. Even villains like Azazel or Allistair are top-notch villains. Hell, I even like characters like Metatron, Lucifer, Mary, and John! Characters like Rufus, Charlie, Crowley, Rowena, Kevin, Ellen, Jo, Bobby, Gabriel, Balthazar, Mick...how am I not supposed to love them??? All of their stories were cut so short. I’d watch a show about any of these characters. The Wayward Sisters were robbed. So many ships were gone too soon (Sam/Rowena, Dean/Jo, Cas/Meg, Etc.). So many heartbreaking deaths. I want to be best friends with all these characters. Why be a “dean-girl” or a “sam-girl” when you can be a garth-girl? A kevin-girl? A claire-girl? A bela-girl? There are so many great characters with interesting and compelling backstories and so much untapped potential. I could go on forever on this, but I digress.This show has one of the best supporting casts I have ever had the pleasure of watching.

3. The Themes

It’s no accident that I got addicted to this show at the time that I did. Namely, my Senior Year of College and 2020. Graduating college and entering the “real world” felt like it’s own sort of apocalypse. 2020 definitely exacerbated my worst tendencies. Messages like “family don’t end in blood”, “you can write your own story”, and “always keep fighting” really resonated with me. I could definitely relate to the feelings of insecurity these character’s felt and the ways they suppressed/repressed their issues instead of facing them. I could relate to the feelings of not fitting in and I could definitely relate to the loneliness. This show helped remind me that I’m not alone. That it’s okay if my values and identity don’t line up with the what I envisioned for myself. And, most importantly, that there is a light at the end of the tunnel and that I should never give up. If Dean, Sam, and Cas can keep moving forward despite their demons and despite how bad it gets, so can I. Regardless of how the story ended, these themes resonated with me and I’ll still hold them with me. A single episode can’t take that away.

4. The Fun Episodes

This show has so many legendary standalone episodes. Changing Channels. Ghostfacers. The French Mistake. Fan Fiction. Tall Tales. Bad Day at Black Rock. When this show goes for the absurd, it goes all-in. It takes the risks it needs to take, it gets completely insane, and it pulls it off. So many of these episodes could have easily been the moment that the show “jumped the shark”. Yet, time after time, the show delivered on it’s potential. I don’t know how much I can say about these episodes except that they made me laugh out loud, made me fall even harder for these characters, and that they’re the episodes I remember best. If I were to rewatch any episode, it would be one of the fun ones. This show knew how to not take itself too seriously and how to poke fun at itself. I’ve always had a soft spot for shows that can make me laugh and cry (X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer/Angel, Doctor Who, etc.), and this show definitely nails the fun part.

5. The Sad Episodes

Death’s Door. Hammer of the Gods. Despair. Carry On. Abandon All Hope. In My Time of Dying. Swan Song. When this show wants you to cry, it doesn’t pull the punches. It gets downright devastating. No character is safe. Literally every character you love will either be forgotten or will die. Or both. The amount of trauma Sam and Dean have to go through is insane. Both have literally been to hell and back. Both have killed countless people, including innocents. When this show decides it wants to wreck you, it’s overwhelming. I sobbed when Bobby died. I sobbed when every single member of Team Free Will died for the final time (I still can’t watch any of those scenes). I still wish Jo, Ellen, Charlie, Kevin, Mick, and Gabriel had been given more time to tell their stories. Being a hunter means a life of endless angst. Being an angel or demon doesn’t get you off the hook, either. I remember going into this show thinking it couldn’t hurt me. My favorite character type is “mentor/father figure”. But holy hell...I don’t think every single sad moment was necessarily good writing, but when it was? Damn.

6. The Biblical Themes

I’m not a relgious person. But, despite this show being steeped in Christian mythology, it really touched on my feelings about the Old Testament in a profound way. Well, really just Ben Edlund and Robbie Thompson did. I’ve never seen a show really hit the overall feel of the bible the way this show does. The idea of Angels as mystical and terrifying creatures. The idea of God as a flawed father figure with a penchant for wrath. The sheer epicness of the biblical stories. The idea of family members constantly being turned on each other. Cain and Abel. Jacob and Essau. Moses and Ramses. Moses and Aaron. Abraham and Isaac. The bible is full of stories of family drama. This show doesn’t always give angels and demons weight. Sometimes it’s silly and stupid and cheesy. But when it hits right? It’s epic. This is more of a personal thing I love about the show, but definitely a plus!

7. The Music

The early seasons music is so good. I really miss the classic rock of the golden era of the show. I mean, there are still some great musical moments later on, but damn. I loved hearing songs I recognized and I loved learning new songs. I loved when the song and the scene hit perfectly in time (Death’s intro. Cas’s return in Season 13.). Also Supernatural wouldn’t be Supernatural without the ‘Carry On My Wayward Son’ song at the end of every season. Even at the end of a season I didn’t love, that recap would always get me pumped. Also Chuck singing Fare Thee Well? Dean and Lee singing together? Fan Fiction? All great.

8. The Cast & Crew

I never care about the actors or actresses in a show. I definitely don’t bother with the names of specific writers and directors or their styles of writing/directing. They’re just random people who happen to write for or play these characters I love. They’re not actually the characters. But these guys? Well, for one, I’m pretty sure half this cast actually is their character. At least to some degree. They’re also just...really cool people? Who are all friends? They make a point to do community service, to interact with fans, and to promote positive ideas. Jared’s Always Keep Fighting campaign. Misha and GISH. The fact that they all participate in fundraising opportunities and encourage fan engagement. Do they all have issues? Definitely. Have they said stupid things? Yes. But the good far outweighs the bad. They’re an entertaining bunch whether onscreen or not and I hope they all do well in whatever their future endeavors may be.

9. The Fandom

I joined this fandom late. To be honest, I thought this fandom was obnoxious before I found myself a part of it. Now that I’ve been in the trenches? It’s got it’s ups and downs like any fandom. There are some parts that are more toxic than others. A lot of people yelling that their opinion is the only opinion. But overall? The good outweighs the bad. And the good? The good is great. Some fanfictions I’ve read are better than actual books I’ve read and just as moving. The fanart? Incredible. I love reading all the metas about random aspects of the show I never would have noticed. I love the music videos and I love the analytical videos. In real life, I’ve made many friends through our mutual love of this show. Hell, even getting sucked into GISH once or twice has given me some solid memories and brought me closer to friends. I wish all fandoms were this much like family. I’m so glad I got to be a part of this fandom and I can’t wait to continue being a fan. After all, nothing ever stays dead in Supernatural.

10. The Chaos & Insanity

Season 16 has been a time. First, Destiel went canon. Then suddenly Sherlock was having a 5th season, Putin was retiring, and Georgia was going blue. Destiel going “canon” and Joe Biden winning the presidency will always be correlated in my mind now. Things in the fandom went from quiet to blaringly loud real fast. Carry On happened. The fandom went into a civil war. I can’t even remember half of what happened in Season 16, but it’s been a wild ride. There’s been ups (my personal favorite being the french dub and the Saileen wedding). There’s been downs (Jared’s controversial statements and the original scripts being leaked). At one point Misha Collins had sex with Bill Clinton???? It’s been a wild time. It’s honestly gotten me through the end of this pandemic. At least it’s entertaining. I would say that at least all the craziness is over, but is it ever really over? Every time I say that something else completely insane happens. But it’s been fun. I’m glad I started watching this show despite my reservations and here’s to whatever happens next.

#team free will#team free will 2.0#castiel#jack kline#sam winchester#dean winchester#sam and dean#destiel#wayward sisters#supernatural#spn#misha collins#jared padalecki#jensen ackles

17 notes

·

View notes

Video

Asherah haElah .:. 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 .:. אשרה .:. μακαρία .:. from Yonah Ben-Ashera on Vimeo.

.:.

Asherah haElah, "Asherah, the Goddess", is a short movie which presents a conjectural reconstruction of the original text of Proverbs 31:28.

One of the most common methods which was used by the priestly editors of the Tanakh (the basis of "the Old Testament") in order to obfuscate all traces of earlier polytheistic tradition was to replace words which they intended to suppress with others that had similar-sounding syllables.

In order to enforce an orthodox interpretation of the texts, subtle changes were made to the original words by the addition of vowel points (niqqud) from the early Middle Ages onward.

Both strategies were considered legitimate especially where the name of a deity was concerned and there was ample ancient precedents to be found in the earlier scribal tradition.

Even though Asherah had revered as the wife of El (the name which predated that of YHWH, which according to the scriptures was first revealed to Moses) the later monarchs and religious reformers did their best to remove Her from veneration with a zeal that was repeated many centuries later during the anti-Marian extremism of the Protestant Reformation.

Asherah (Ugaritic: 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 : 'ṯrt ) (Hebrew: אשרה) was the original mother of the Elohim ("the Gods") in ancient Semitic religion as Her title, Qaniyatu Elima, meaning "the Creatrix of the Elohim" (Ugaritic : 𐎖𐎐𐎊𐎚 𐎛𐎍𐎎 : qnyt ʾlm) fully attests.

In the Ugaritic texts (before 1200 BCE) Athirat is called 'Lady Athirat of the Sea' (Ugaritic : 𐎗𐎁𐎚 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 𐎊𐎎 rbt ʼaṯrt ym : rabat ʼAṯirat yammi) or as more fully translated 'She who walks upon the sea' (Yam Kinnereth - Lake Galilee), the name understood by various translators and commentators to be from the Ugaritic root ʼaṯr 'stride' cognate with the Hebrew root ʼšr of the same meaning.

In Biblical Hebrew the same root word may be translated as both "happy" and "blessed", exactly the same as the Greek word μακαρία "Makaria" which also has both of these meanings and appears in the Septuagint as a translation of the name that women gave to Leah at the birth of her son.

Genesis 30:13

Leah said:

I have been blessed!

Women will call me "Blessed."

So she named him Asher [Blessing].

Proverbs 31:28

And her children shall call her "Blessed"

In the Ugaritic epic of Keret the coastal cities of Tyre and Sidon are named as especially sacred to Her and are document as divine epithets :

Athirat of Tyre

Elath of Sidon

Asher, the son of Leah, was the eponymous ancestor of the Tribe of Asher whose limited territory significantly included both Tyre and Sidon, famous in the ancient world as the sacred temple sites of Asherah.

_____________________________

The memory of Asherah was never fulled erased from Jewish mystical tradition.

It resurfaces in Qabalistic works such as the Pardes Rimmonim ("The Orchard of Pomegranates") and the Book of Zohar as one of the earliest names of the Shekinah, the Holy Spirit who is the Bride of G-d.

The Shekinah is still invoked in Sabbath hymns which contain the chorus of "Bo-i Kallah, Shekinah" (come to us, O Bride, Shekinah).

_____________

from "An Altar of Earth:Reflections on Jews, Goddesses and the Zohar" by Rabbi Jill Hammer

_____________

Yet the Zohar, steeped in multiple personalized, sexualized, gendered images of the deity, chooses to read this passage (Deuteronomy 16:21) in a radically different way.

The Zohar writers do not equate Asherah with Lilith or another demonic figure, which would be an easy theological move.

Instead, they reread the verse.

It is not, they say, that the Torah wants to tell us not to plant an asherah by the altar because it is an idolatrous object.

If the Torah had wanted to tell us that, it simply would have said: "Do not plant an asherah anywhere."

Rather, the Torah wants to tell us that Asherah is a name for the Shekhinah, the feminine Divine presence, already at the altar.

...

The Zohar redefines the word Asherah as the feminine form of Asher: the Spouse of Asher, the Spouse of God.

The verse now means, in the Zohar's reading, that we must not plant an asherah by the altar because Asherah already resides in the altar in the form of the Shekhinah. We do not need a pillar to remind us of Her.

The Zohar does not choose to say that the goddess Asherah is evil or false and that worshipping her is a theological mistake.

Rather, it says that the theological mistake would be to assume that Asherah (the tree) is separate from Shekhinah (the altar), when in fact they are one.

The Zohar seems to be saying is that the object used to worship (i.e. the altar) God must be single rather than multiple, just as all the faces of the feminine and masculine Divine are ultimately unified.

...

Yet the Zohar does not take this easy approach. Instead, it comes up with a statement even more shocking than the first:

The only reason we may not worship the Shekhinah as Asherah is that the name Asherah, as translated by the Zohar, means "happy."

(The Zohar proves this by connecting the matriarch Leah, who herself is an image of feminine divinity in the mystical tradition, to the root alef-shin-reish, which translates as "happy" or "fortunate.")

The Shekhinah is in exile among the enemies of the Jewish people, and therefore we cannot call Her happy.

That separation and not idolatry is the error.

The Zohar implies that we abstain from using the name Asherah, not out of theological exactness, but out of courtesy: we abstain in order to empathize with the pain of the Shekhinah.

The unspoken implication of this is that in the world to come, when the Messiah has arrived, we will be able to call the Shekhinah Asherah.

אהיה אשרה יהוה

Ehyeh Asherah YHWH

_______________

Rabbi Jill Hammer, PhD, is a senior associate at Ma'yan: the Jewish Women's Project of the Jewish Community Center in Manhattan.

She is an author, poet, midrashist, and ritual-maker.

Her book is entitled "Sisters at Sinai: New Tales of Biblical Women" (JPS, 2001).

ONLINE SOURCE :

zeek.net/spirit_0407.shtml

.:.

SEE ALSO :

facebook.com/group.php?v=wall&gid=45359906174

____

Compare the phrase from the Lekhah Dodi which is hidden behind the phrase which is usually translated as "crown of Her husband"

Astarte-Baalat

𐎓𐎘𐎚𐎗𐎚 𐎁𐎓𐎍𐎚

בואי בשלום עטרת בעלה

בואי כלה בואי כלה

בואי כלה שבת מלכתא

לכה דודי

Both layers of meaning (the outer and the inner - the exoteric and the esoteric) complement and enhance each other which is as it should be.

Lecha Dodi was composed by Rabbi Shlomo Halevy Alkabetz (1505-1584), one of the Kabbalists of Safed.

He arranged the poetical composition so that the first letters of each stanza spells out the name of the author, a practice quite common among liturgical poets.

Although several versions of a hymn by this name had been circulating at that time, this is the one that was adopted by Rabbi Issac Luria, the foremost authority among the Kabbalistic masters.

It seems that it was not only the Rabbi's name which had been encoded into the words of this invocation.

____

.:.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 3/?

Previous post

I don’t agree with everything in this post, specifically it claiming that evolution is false. I’m honestly still studying that and thinking about it. But, I’m sure you get the main idea, the main audience or rather the target audience is Christians.

Made in God's Image: Then God said, "Let Us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness…" –Gen. 1:26