#critical queer theory

Text

==

This is really fascinating stuff, and it provides a biological basis for why society should be empathetic towards people with gender dysphoria. They're not just "crazy," they have a clinically recognizable neurological condition.

Question: how does someone "self ID" their own intrinsic network connectivity in their parietal-occipital and fronto-parietal networks? And why are we still entertaining this trans "self ID" crap as an "identity"?

🤔

#Zach Elliott#gender dysphoria#dimorphism#body image#self perception#own body processing#default mode network#cerebral midline#neurobiology#science#medicine#queer theory#critical queer theory#gender ideology#religion is a mental illness

129 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hannah Montana’s Guide to Life Under Capitalism

Haven’t posted in a while but made a new video :)

#queer#youtube#video essay#hannah montana#miley cyrus#lgbt#gay#commentary#sociology#critical theory#Judith butler#gender#trans#transgender

254 notes

·

View notes

Text

It seems like every year I end up writing an iteration of the same idea. But here I am! Writing it again! If you haven’t seen the tweet that sparked this conversation, I’ve screenshotted the tweet and artwork below. It’ll help inform this discussion. Full piece under the cut.

It would help to check out my essay from 2021 about the emasculation of Abdul Ali from Squid Game, since both pieces share similar references.

Maryam Khalid writes “Orientalist notions of the masculinity of the ‘Eastern’ male as uncivilized also inherently ascribe primitiveness, ineptness and a certain amount of weakness to the barbarized ‘other.’” Those doomed to the mythical Orient are automatically placed lower in masculinity than their white and colonial counterparts.

The reason for this emasculation is to defang them, to ensure they can never attain the same power conferred by white masculinity and to maintain racial purity: “This feminizing divests the male body of its virility and thus compromises its power not only to penetrate and reproduce its own nation (our women), but to contaminate the other's nation (their women) as well” (Puar, 99).

To be South Asian is to be pathologically queer, irrespective of the one’s true sexual orientation. “The Orient becomes a living tableau of queerness” by virtue of being from the Orient (Said, 103). There is already a robust amount of artwork depicting Pavitr with tons of gold jewelry and piercings, which to the West are typically feminine accessories. This essentially reduces Pavitr to a stereotype of South Asian culture.

Fanworks use the bejeweled, indulgent, exotic, and sultry attitude as a short-hand for their perception of South Asia. They are “caricatures stripped from movies like Disney’s Aladdin, the Arcana or people’s sexual fantasies about our men,” as allahrakhi writes in her essay on fandom's reception of Claude von Riegan from Fire Emblem: Three Houses, a character similarly mischaracterized by virtue of his brown identity.

Puar describes that the (implied white) nation defines “upright, domesticatable queernesses that mimic and recenter liberal subjecthood, and out-of-control, untetherable queernesses” (47). Nonwhite queerness is “untetherable,” leaving white queerness as “domesticatable.” This inability to engage brown queerness forces brown queer people to assimilate into white queerness.

In fandom’s and society’s mind, there is no such thing as a queer South Asian without them discarding their brown identity and adopting white queer practices, behaviors, and aesthetics. Queer South Asians are “either liberated (and the United States and Europe are often the scene of this liberation) or can only have an irrational, pathological sexuality of queerness” (Puar, 13).

Which brings us to the recent depictions of Pavitr in fanworks, stripping him of his masculinities to render him as a vapid, neutered, and yes, whitewashed queer boy, completely unrecognizable from the source material.

Interestingly, this reduced masculinity co-exists, paradoxically, with the idea that men from the Orient are simultaneously aggressive, belligerent, and violent. Elgin Brunner writes: “Such a framing—the association of the enemy with barbarism, as opposed to the self, which is civilized—includes two, often simultaneous, moves, that is: the ‘hypermasculinization’ of the enemy on the one hand, and his ‘effeminization’ on the other… The very same opponent is, by virtue of being categorized as a cowardly barbarian, rendered effeminate.”

The flip side of the effeminate brown man is the hypermasculine brown man, which can be seen through Miguel, one of Across the Spider-Verse’s antagonists. Both instances of brown masculinity confiscate personhood from characters who would have otherwise offered rich, nuanced, interesting perspectives to the story and to the audience.

It would be myopic of me to not mention the implicit genderings of other nonwhite ethnicities in this discussion. Brown men hold a unique positionality to other nonwhite men in a racial triangulation I’d like to examine further in another essay for the future. Brown men can either be gendered the way that East Asians are (feminine, asexual, neutered, timid, obedient) or the way that Black people are (hypersexual, predatory, dangerous, aggressive). Both misgenderings are in opposition to the “ideal” male gender, which is of course, the white man. This fallacy is why we see Hobie depicted as cruel, mean, and irritated in the exact same artwork from earlier.

Many people in this artist’s quoted replies have accused the artist of being white. I have seen some criticisms of the backlash, that people shouldn’t assume the artist’s ethnicity. I think both opinions miss the point: anyone can be orientalist. Membership within a nonwhite ethnic identity does not absolve the individual of perpetuating orientalist or racist depictions of characters of color.

As Edward Saïd said, “Everyone who writes about the Orient must locate himself vis-a-vis the Orient” (Orientalism, 20). That is to say, if you write and depict the Orient and people from the Orient, you have to consider your positionality in relation to the Orient. Naturally, this would mean that white people should always be cognizant of their depictions of Orientals. But East Asians can also orientalize, whether it is other ethnic groups like South Asians; or self-orientalization. Similar can be said for South Asians who self-orientalize.

Khalid writes “Gendered identities do not exist independently of other factors, and must be viewed as intertwined with, for example, race or ethnicity if we are to understand the hierarchical organization of identities.” There is no examination of gender without an accompanying racial context. And Pavitr’s emasculation in fandom certainly requires a critical eye for both race and gender, lest we repeat the same dehumanizing characterizations of him in further fanworks.

Works Consulted:

Brunner, E. M. (2008). Consoling display of strength or emotional overstrain? the gendered framing of the early “War on terrorism” in transatlantic comparison. Global Society, 22(2), 217–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600820801887223

Khalid, M. (2011). Gender, orientalism and representations of the ‘other’ in the War on Terror. Global Change, Peace & Security, 23(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781158.2011.540092

Puar J. K. (2007). Terrorist Assemblages: homonationalism in queer times. Duke University Press.

Said, E. W. (1994). Orientalism. 25th anniversary edition. With a new preface by the author. New York, Vintage Books.

#pravitr prabhakar#across the spiderverse#spiderverse#meta analysis#critical race theory#gender studies#queer studies#khalid text

248 notes

·

View notes

Text

#radical feminists do interact#lgbtq community#lgbt pride#lgbtq#lgbtqia#lesbian#nonbinary#queer#sapphic#nonbinary lesbian#radical feminists do touch#radical feminism#radical feminist safe#radical feminist community#gay girls#radical feminist theory#gender critical#radical feminists please touch#terfsafe#radblr#terfblr#terfism#lgb drop the t

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

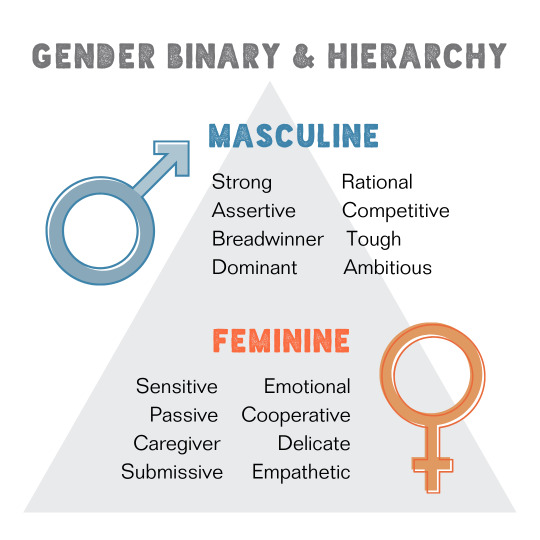

Gender Is A Hierarchy, Not A Spectrum or Identity

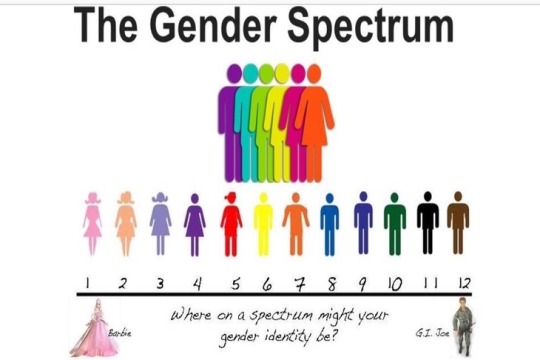

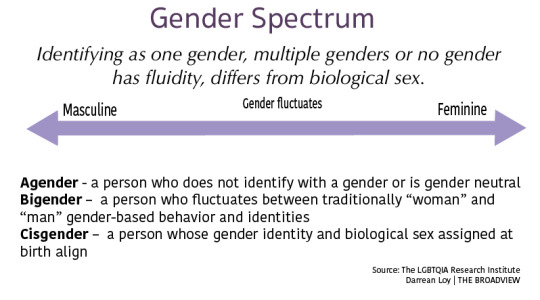

Within the last decade, I’m sure that we have all seen something like this in a sociology class or just from scrolling through social media…

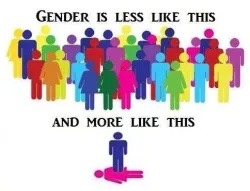

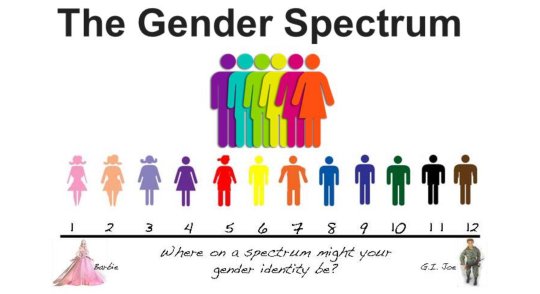

Queer theory is a postmodernist theory that has put forth the idea that gender exists on a spectrum as opposed to a binary. Important queer theorist, Judith Butler, says that gender is something fluid, always changing. Not only that, gender is also a performance. We do gender by how we act, what clothes we wear, what hobbies we enjoy. Queer theory says that gender is not tied to biology, it is socially constructed, and that, in theory, there can be an infinite amount of genders (Brown, 2019). While, I can definitely agree that gender is socially constructed, everything else that queer theory says about gender is a no from me. Here’s why I disagree and why I think all people need to think critically about what queer theory is really saying.

For thousands of years, femininity has been thrust upon females and masculinity has been thrust upon males. While some aspects of masculinity and femininity have changed throughout time and culture, some things have remained inherent about those constructs. Femininity enforces submission and weakness onto women. It puts women into the caretaking and child-rearing role based on their biological capacity to give birth. This keeps women dependent on men and prevents us from attaining social, political, and financial power. Femininity also sexualizes women, and causes us to become physically weak (foot binding, high heels, avoidance of gaining muscle mass, dresses and skirts which restrict movement). All of this because we are born female. We are put into the feminine gender because of our sex. As for males, they are put into the masculine gender. Masculinity enforces domination, leadership, and control. Due to those qualities, the masculine gender gives males social, political, and financial power, not just over themselves, but specifically over women. In essence, gender is the the imposed masculinity and femininity according to our sex, and one gender is put above the other. Society has created a hierarchy of gender where people who are given the masculine gender (males) are given power over those with the feminine gender (females).

Now of course, as a feminist, I am very against this gender binary/hierarchy, and many feminists in the 90s and early 2000s pushed back against this which is how queer theory started. The issue is that queer theory ignores the hierarchy part of gender. Gender is a social hierarchy just like race and class. In our white supremacist, capitalist society, white people unfortunately still hold power over other races, and the rich hold power over the poor. This same line of thinking applies to gender, because gender is a system that gives men power over women. Queer theory ignores/dismisses gender being a system that oppresses women based on our sex. Which leads to my next disagreement. Queer theory posits that gender is not actually tied to sex at all. This is a blatant lie. How have we decided for thousands of years who is put into the fem gender and who is put into the masc gender? We use sex. Females are put into the lower class of the gender hierarchy and males are put into the upper class of the hierarchy. So actually, sex and gender are intimately tied together. This is not to say that sex = gender. Gender, again, is a social construct of femininity and masculinity, but more than that, it’s a system of oppression that is based on sex. Now you could say, “well wouldn’t queer theory actually be good for women? It gets rid of the strict gender roles forced upon them?” Not true. It actually is dependent on gender roles and it implies that in order to get rid of oppressive gender, women can simply choose not to perform femininity. The issue with that is there is an abundance of research out there (and personal experiences of GNC women) to show that choosing to not be feminine doesn’t get rid of the social hierarchy that is attached to something we can’t change. Our sex. Queer theory of course says that sex is also a social construct.

“For Butler, the linguistic (discursive) norms we apply to talk about sex, sex organs and the body themselves create the idea of bodily sex (ibid.). Some theorists thus argue that the idea of male and female bodies with definitively different organs, hormones and chromosomes is an understanding that we have created through language and through the social meanings we inscribe on the body” (Brown, 2019).

Queer theorists like to argue that the only reason a body with testes, a penis, and flat chest is male, is because we as a society have all agreed that those characteristics make up a male body, that there is nothing innately male about that body. The same applies to the female body. The thing is, that just because us humans have the ability to categorize and name things found in nature, does not mean we constructed it. If it can be naturally observed, untouched by cultural ideas, then it is a natural phenomenon, not a social one. Humans were being born as males and females long before we had language or culture. Male and female are sexes found in many species, with or without understandings of gender.

Conclusion

So gender as a performance just doesn’t hold up. It reduces gender down to our actions, our clothing, etc… It is also dangerous, since it says that gender is not a hierarchy, but a spectrum of identities and outward expression. This causes feminists to ignore or dismiss the power struggle and oppressive systems at play between the sexes. The gender spectrum also relies heavily on oppressive gender roles and even perpetuates them. Take another look at the first two images from above. The first image shows gender as being a spectrum between traditional femininity and traditional masculinity. You are either a “Barbie” or a “GI Joe”. In fact, gender as a spectrum doesn’t get rid of gender at all. It doesn’t push back against gender norms or stereotypes at all. It simply says that there is a spectrum of gender between highly feminine and highly masculine. It is dependent on the two genders. It relies on the two genders to create gender identities that are a mix of the two. Queer theory’s gender identity relies on keeping this hierarchy alive, while simultaneously ignoring how this hierarchy puts men above women. Here is a quote and image I found that really sums up this entire post if some of you are still confused or if I just didn’t explain things that well.

“Gender is a hierarchy that enables men to be dominant and conditions women into subservience. As gender is a fundamental element of white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (hooks, 1984) it is particularly disconcerting to see elements of queer discourse argue that gender is not only innately held but sacrosanct. Far from being a radical alternative to the status quo, the project of “queering” gender only serves to replicate the standards set by patriarchy through its essentialism. A queer understanding of gender does not challenge patriarchy in any meaningful way – rather than encouraging people to resist the standards set by patriarchy, it offers them a way to embrace it. Queer politics have not challenged traditional gender roles so much as breathed fresh life into them – therein lies the danger.To argue that gender could or should be “queered” is to lose sight of how gender functions as a system of oppression. Hierarchies cannot, by definition, be assimilated into the politics of liberation. Structural power imbalances cannot be subverted out of existence – reducing gender to a matter of performativity or personal identification denies its practical function as a hierarchy” (sisteroutrider.Wordpress.com).

Sources:

Extra Readings that I think are helpful in understanding this topic:

Gender heriarchy and the social construction of femininity; the imposed mask by Kouadio Germain N’ Guessan

It’s not about the gender binary, it’s about the gender hierarchy: a reply to “letting go of the gender binary” by Jeanne Ward (especially page 291-294)

#gender abolition#gender hierarchy#gender critical#queer theory#gender is a performance#gender is a social construct#radfem ideology#radfem#radblr

297 notes

·

View notes

Text

oh andrea long chu normal fucking life paragraph we;re rlly in it now

#tgis article criticizing da entire field is tge only queer theory ive ever read & tjis paragraph is all i rememver from it but i think#abt it all da time

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary: Chapter 4 of Critical Intersex

For many of us, Chapter 4 of Critical Intersex (2009) turned out to be a particularly rich source of information about intersex history. So I (Elizabeth) have decided to give a fairly detailed summary of the chapter because I think it’s important to get that info out there. I’m gonna give a little bit of commentary as I go, and then a summary of our book club discussion of the chapter.

The chapter is titled “(Un)Queering identity: the biosocial production of intersex/DSD” by Alyson K. Spurgas. It is a history of ISNA, the Intersex Society of North America, and how it went from being a force for intersex liberation to selling out the movement in favour of medicalization. (See here for summary of the other chapters we read of the book!)

Our high level reactions:

Elizabeth (@ipso-faculty): Until I read chapter 4, I didn't really realise how reactionary “DSD” was. It hadn't been clear to me how much it was a response to the beginning of an organized intersex advocacy movement in the United States.

Michelle (@scifimagpie): I could feel the fury in the writer's tone. It was a real barn burner.

Also Michelle: the fuckin' respectability politics of DSD really got under my skin, as a term! I know the importance, as a queer person, of not forcing people to ID as queer, but this was a lot.

Introducing the chapter

The introduction sets the tone by talking about how in the Victorian era there was a historical shift from intersex being a religious/juridical issue to a pathology, and how this was intensified in the 1950s with John Money’s invention of the optimal gender rearing model.

Spurgas briefly discusses how the OGR model is harmful to intersex people, and how it iatrogenically produces sexual dysfunction and gender dysphoria. “Iatrogenic” means caused by medicine; iatrogenesis is the production of disease or other side-effects as a result of medical intervention.

This sets scene for why in the early 1990s, Cheryl Chase and other intersex activists founded the Intersex Society of North America (ISNA). It had started as a support group, and morphed significantly over its lifetime. ISNA closed up shop in 2008.

Initially, ISNA was what we’d now call interliberationist. They were anti-pathologization. Their stance was that intersexuality is not itself pathological and the wellbeing of intersex people is endangered by medical intervention. They organized around the abolition of surgical intervention. They also created fora like Hermaphrodites With Attitude for the deconstruction of bodies/sexes/genders and development of an intersex identity that was inherently queer.

The early ISNA activists explicitly aligned intersexuality in solidarity with LGB and transgender organizing. There was a belief that similar to LGBT organizing, once intersex people got enough visibility and consciousness-raising, people would “come out” in greater numbers (p100).

By the end of the 90s, however, many intersex people were actively rejecting being seen as queer and as political subjects/actors. The organization had become instead aligned with surgeons and clinicians, had replaced “intersex” with “DSD” in their language.

By the time ISNA disbanded in 2008 they had leaned in hard on a so-called “pragmatic” / “harm reduction” model / “children’s rights perspective”. The view was that since infants in Western countries are “born medical subjects as it is” (p100)

Where did DSD come from?

In 2005, the term “disorders of sexual differentiation” had been recently coined in an article by Alice Dreger, Cheryl Chase, “and three other clinicians associated with the ISNA… [so as] to ‘label the condition rather than the person’” (p101). Dreger et al thought that intersex was “not medically accurate” (p101) and that the goal should be effective nomenclature to “sort patients into diagnostically meaningful groups” (p101).

Dreger et al argued that the term intersex “attracts the interest of a large number of people whose interest is based on a sexual fetish and people who suffer from delusions about their own medical histories” (Dreger et al quoted on p101)

Per Spurgas, Dreger et al had an explicit agenda of “distancing intersex activism from queer and transgressive sex/gender politics and instead in supporting Western medical productions of intersexuality” (p102). In other words: they were intermedicalists.

According to Dreger et al, an alignment with medicine is strategically important because intersex people often require medical attention, and hence need to be legible to clinicians. “For those in favor of the transition to DSD, intersex is first and foremost a disorder requiring medical treatment” (p102)

Later in 2005 there was a “Intersex Consensus Meeting” organized by a society of paediatricians and endocrinologists. Fifty “experts” were assembled from ten countries (p101)... with a grand total of two actually intersex people in attendance (Cheryl Chase and Barbara Thomas, from XY-Frauen).

At the meeting, they agreed to adopt the term DSD along with a “‘patient-centred’ and ‘evidence-based’ treatment protocol” to replace the OGR treatment model (p101)

In 2006, a consortium of American clinicians and bioethicists was formed and created clinical guidelines for treating DSDs. They defined DSD quite narrowly: if your gonads or genitals don’t match your gender, or you have a sex chromosome anomaly. So no hormonal variations like hyperandrogenism allowed.

The pro-DSD movement: it was mostly doctors

Spurgas quotes the consortium: “note that the term ‘intersex’ is avoided here because of its imprecision” (p102) - our highlight. There’s a lot of doctors hating on intersex for being a category of political organizing that gets encoded as the category is “imprecise” 👀

Spurgas gets into how the doctors dressed up their re-pathologization of intersex as “patient centred” (p103) - remember this is being led by doctors, not patients, and any intersex inclusion was tokenistic. (Elizabeth: it was amazing how much bs this was.)

As Spurgas puts it, the pro-DSD movement “represents an abandonment of the desire for a pan-intersexual/queer identity and an embrace of the complete medicalization of intersex… the intersex individual is now to be understood fundamentally as a patient” (p103)

Around the same time some paediatricians almost came close to publicly advocating against infant genital mutilation by denouoncing some infant surgeries. Spurgas notes they recommended “that intersex individuals be subjected (or self-subject) to extensive psychological/psychiatric, hormonal, steroidal and other medical” interventions for the rest of their lives (p103).

This call to instead focus on non-surgical medical interventions then got amplified by other clinicians and intermedicalist intersex advocacy organizations.

The push for non-surgical pathologization hence wound up as a sort of “compromise” path - it satisfied the intermedicalists and anti-queer intersex activists, and had the allure of collaborating with doctors to end infant surgeries. (Note: It is 2024 and infant surgeries are still a thing 😡.)

The pro-DSD camp within the intersex community

Spurgas then goes on to get into the discursive politics of DSD. There’s some definite transphobia in the push for “people with DSDs are simply men and women who happen to have congenital birth conditions” (p104). (Summarizer’s note: this language is still employed by anti-trans activists.)

The pro-DSD camp claimed that it was “a logical step in the ‘evolution in thinking’” 💩 and that it would be a more “humane” treatment model (p105) 💩

Also that “parents and doctors are not going to want to give a child a label with a politicized meaning” (p104) which really gives the game away doesn’t it? Intersex people have started raising consciousness, demanding their rights, and asserting they are not broken, so now the poor doctors can’t use the label as a diagnosis. 🤮

Spurgas quotes Emi Koyama, an intermedicalist who emphasized how “most intersex people identify as ‘perfectly ordinary, heterosexual, non-trans men and women’” (p104) along with a whole bunch of other quotes that are obviously queerphobic. Note from Elizabeth: I’m not gonna repeat it all because it’s gross. In my kindest reading of this section, it reads like gender dysphoria for being mistaken as genderqueer, but instead of that being a source of solidarity with genderqueers it is used as a form of dual closure (when a minority group goes out of its way to oppress a more marginalized group in order to try and get acceptance with the majority group).

Koyama and Dreger were explicitly anti-trans, and viewed intergender type stuff as “a ‘trans co-optation’ of intersex identity” (p105) 🤮

Most intersex people resisted “DSD” from its creation

On page 106, Spurgas shifts to talking about how a lot intersex people were resistant to the DSD shift. Organization Intersex International (OII) and Bodies Like Ours (BLO) were highly critical of the shift! 💛 BLO in particular noted that 80-90% of their website users were against the DSD term. Note from Elizabeth: indeed, every survey I’ve seen on the subject has been overwhelmingly against DSD - a 2015 IHRA survey found only 3% of intersex Australians favoured the DSD term.

Proponents of “intersex” over “DSD” testified to it being depathologizing. They called out the medicalization as such: that it serves to reinforce that “intersex people don’t exist” (David Cameron, p107), that it is damaging to be “told they have a disorder” (Esther Leidolf, p107), that there is “a purposeful conflation of treatment for ‘health reasons’ and ‘cosmetic reasons’ (Curtis Hinkle, p107), and that it’s being pushed mainly by perisex people as a reactionary, assimilationist endeavour (ibid).

Interliberationism never went away - intersex people kept pushing for 🌈 queer solidarity 🌈 and depathologization - even though ISNA, the largest intersex advocacy organization, had abandoned this position.

Spurgas describes how a lot of criticism of DSD came from non-Anglophone intersex groups, that the term is even worse in a lot of languages - it connotes “disturbed” in German and has an ambiguity with pedophilia and fetishism in French (p111).

The DSD push was basically entirely USA-based, with little international consultation (p111). Spurgas briefly addresses the imperialism inherent in the “DSD” term on pages 118/119.

Other noteworthy positions in the DSD debate

Spurgas gives a well-deserved shout out to the doctors who opposed the push to DSD, who mostly came from psychiatry and opposed it on the grounds that the pathologization would be psychologically damaging and that intersex patients “have taken comfort (and in many cases, pride) in their (pan-)intersex identity” (p108) 🌈 - Elizabeth: yay, psychiatrists doing their job!

Interestingly, both sides of the DSD issue apparently have invoked disability studies/rights for their side: Koyama claimed DSD would herald the beginning of a disability rights based era of intersex activism (p109) while anti-DSDers noted the importance in disability rights in moving away from pathologization (p109).

Those who didn’t like DSD but who saw a strategic purpose for it argued it would “preser[ve] the psychic comfort of parents”, that there is basically a necessity to coddle the parents of intersex children in order to protect the children from their parents. (p110)

Some proposed less pathologizing alternatives like “variations of sex development” and “divergence of sex development” (p110)

The DSD treatment model and the intersex treadmill

Remember all intersex groups were united that sex assignment surgery on infants needs to be abolished. The DSD framework that was sold as a shift away from surgical intervention, but it never actually eradicated it as an option (p112). Indeed, it keeps ambiguous the difference between medically necessary surgical intervention and culturally desired cosmetic surgery (p112). (Note from Elizabeth: funny how *this* ambiguity is acceptable to doctors.)

What DSD really changed was a shift from “fixing” the child with surgery to instead providing “lifelong ‘management’ to continue passing” (p112), resulting in more medical intervention, such as through hormonal and behavioural therapies to “[keep] it in remission” (p113).

Cheryl Chase coined the “intersex treadmill’: the never-ending drive to fit within a normative sex category (p113), which Spurgas deploys to talk about the proliferation of “lifelong treatments” and how it creates the need for constant surveillance of intersex bodies (p114). Medical specialization adds to the proliferation, as one needs increasingly more specialists who have increasingly narrow specialties.

There’s a cruel irony in how the DSD model pushes for lifelong psychiatric and psychological care of intersex patients so as to attend to the PTSD that is caused by medical intervention. (p115) It pushes a capitalistic model where as much money can be milked as possible out of intersex patients (p116).

The DSD treatment model, if it encourages patients to find community at all, hence pushes condition-specific medical support groups rather than pan-intersex advocacy groups (p115)

Other stuff in the chapter

Spurgas does more Foucault-ing at the end of the chapter. Highlight: “The intersex/DSD body is a site of biosocial contestation over which ways of knowing not only truth of sex, but the truth of the self, are fought. Both intelligibility and tangible resources are the prizes accorded to the winner(s) of the battle over truth of sex” (p117)

There’s some stuff on the patient-as-consumer that didn’t really land with anybody at the book club meeting - we’re mostly Canadians and the idea of patient-as-consumer isn’t relatable. Ei noted it isn’t even that relatable from their position as an American.

***

Having now summarized the chapter, here's a summary of our discussion at book club...

Opening reactions

Michelle (M): the way the main lady involved became medicalized really made my heart sink, reading that.

Elizabeth (E): I do remember some discussion of intersex people in the 90s, and it never really grew in the way that other queer identities did! This has kind of helped for me to understand what the fuck happened here.

E: It was definitely a very insightful reading on that part, while being absolutely outraging. I didn't know, but I guess I wasn't surprised at how pivotal US-centrism was. The author was talking about "North American centric" though but always meant the United States!!! Canada was just not part of this! They even make mention of Quebec as separate and one of the opposing regions. I was like, What are you doing here, America? You are not the entirety of our continent!!!

E: The feedback from non-Anglophone intersex advocates that DSD does not translate was something that I was like, "Yes!" For me, when I read the French term - that sounded like something that would include vaginismus, erectile dysfunction - it sounds far more general and negative.

M: the fuckin' respectability politics of DSD really got under my skin, as a term! I know the importance, as a queer person, of not forcing people to ID as queer, but this was a lot.

E: it was very assimilationist in a way that was very upsetting. I knew intellectually that this was going on. There was such a distinct advocacy push for that. The coddling of parents and doctors at the expense of intersex people was such a theme of this chapter, in a way that was very upsetting. They started out with this goal of intersex liberation, and instead, wound up coddling parents and doctors.

Solidarities

M: I feel like there's a real ableist parallel to the autism movement here… It dovetails with how the autism movement was like, "Aww, we're sorry about your emotionless monster baby! This must be so hard for you [parents]!" And it felt like "aw, it's okay, we'll fix your baby so they can interface with heterosexuality!" [Note: both of us are neurodivergent]

E: A lot of intersexism is a fear that you're going to have a queer child, both in terms of orientation and gender.

E: You cannot have intersex liberation without putting an end to homophobia and transphobia.

M: We're such natural allies there!

E: I understand that there are these very dysphoric ipsogender or cisgender people, who don't want to be mistaken as trans, but like it or not, their rights are linked to trans people! When I encounter these people, I don't know how to convey, "whether you like it or not, you're not going to get more rights by doing everything you can to be as distant as possible."

M: it reminds me of the movements by some younger queers to adhere to respectability politics.

E: Oh no. There are younger queers who want respectability politics????

M: well, some younger queers are very reactionary about neopronouns and kink at pride. they don't always know the difference between representation and "imposing" kinks on others. In a way, it reminds me of the more intentional rejection of queer weirdos, or queerdos, if you will, by republican gays.

E: I feel like a lot of anti-queerdom that comes out of the ipso and cisgender intersex community reads as very dysphoric to me. That needs to be acknowledged as gender dysphoria.

M: That resonates to me. When I heard about my own androgen imbalance, I was like, "does that mean I'm not a real woman?" And now I would happily say "fuck that question," but we do need an empathy and sensitivity for that experience. Though not tolerance for people who invalidate others, to be honest.

E: The term "iatrogensis" was new to me. The term refers to a disease caused or aggravated by medical intervention.

M: So like a surgical complication, or gender dysphoria caused by improper medical counselling!

The DSD debate

ei: i think the "disorder" discussion is really interesting. in my opinion, if someone feels their intersex condition is a disorder they have every right to label it that way, but if someone does not feel the same they have every right to reject the disorder label. personally i use the label "condition". i don't agree with forcing labels on anyone or stripping them away from anyone either.

M: for me, it felt like a cautionary tale about which labels to accept.

ei: i'm all around very tired of people label policing others and making blanket statements such as "all people who are this have to use this label”... i also use variation sometimes, i tend to go back and forth between variation and condition. I think it's a delicate balance between being sensitive to people's label preferences vs making space for other definitions/communities.

We then spoke about language for a bunch of communities (Black people, non-binary people) for a while

E: one thing that was very harrowing for me about this chapter is that while there was this push to end coercive infant surgery, they basically ceded all of the ground on "interventions" happening from puberty onward. And as someone who has had to fight off coercive medical interventions in puberty, I have a lot of trauma about violent enforcement of femininity and the medical establishment.

ei: i completely agree that it's psychologically harmful tbh…. i was assigned male at birth and my doctors want me to start testosterone to make me more like a perisex male. which is extremely counterproductive because i'm literally transfem and have expressed this many times

Doctors Doing Harm

M: for me, the validation of how doctors can be harmful in this chapter meant a lot.

E: something that surprised me and made me happy was that there were some psychiatrists who spoke out against the DSD label. As someone who routinely hears a lot of anti-psychiatry stuff - because there's a lot of good reason to be skeptical of psychiatry, as a discipline - it was just nice to see some psychiatrists on the right side of things, doing right by their patients. Psychiatrists were making the argument that DSD would be psychologically harmful to a lot of intersex people.

ei: like. being told that something so inherently you, so inherently linked to your identity and sense of self, is a disorder of sexual development, something to be fixed and corrected. that has to be so harmful

ei: like i won't lie i do have a lot of severe trauma surrounding the way i've been treated due to being intersex. but so much of my negative experiences are repetitive smaller things. Like the way people treat me like my only purpose is to teach them about intersex people …. either that or they get really creepy and gross. I’m lucky in that i'm not visibly intersex, so i do have the privilege of choosing who knows. but there's a reason why i usually don't tell people irl.

M: intersex and autism have overlap again about how like, minor presentation can be? As opposed to the sort of monstrous presentation [Carnival barker impression] "Come see the sensational half-man, half-woman! Behold the h-------dite!" And like - the way nonverbal people are also treated feels relevant to that, because that's how autism is often treated, like a freakshow and a pity party for the parents? And it's so dehumanizing. And as someone who might potentially have a nonverbal child, because my wife is expecting and my husband and she both have ADHD - I'm just very fed up with ableism and the perception of monstrosity.

Overall, this was a chapter that had a lot to talk about! See here for our discussion of Chapters 5-7 from the same volume.

#intersex#intersex studies#queer theory#gender studies#actually intersex#intersex rights#intersex activism#intersex books#book reviews#book summaries#paper summaries#lit review#critical intersex#intersex history

52 notes

·

View notes

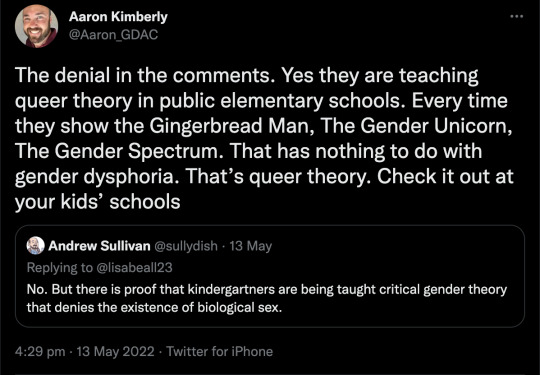

Photo

Step 1. Denial: “LiTeRaLLy nO oNe Is TeAcHiNg X!”

Step 2. Motte and Bailey: “X iS JuSt AbOuT tEaChiNg Y!!”

Step 3. Reversal: “OnLy a BiGoT wOuLdN’T wAnT uS tEaChInG X!!!”

Every. Time.

#Aaron Kimberly#Gender Dysphoria Alliance#queer theory#critical queer theory#gender ideology#denial#gaslighting#biological sex#genderbread person#gender unicorn#gender spectrum#gender dysphoria#ideological indoctrination#child indoctrination#childhood indoctrination#indoctrination#gender pseudoscience#gender woo#corruption of education#biology denial#gender cult#woke#wokeism#woke activism#cult of woke#wokeness as religion#religion is a mental illness

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think there is some connection between this post and this post

the increasing tendency to treat flaws as justification to declare something wholly “problematic” is a big piece of the anti-intellectualism on the left

the entire point of criticism in academia is to refine & improve understanding in your field. when you level criticism, you are seeking to create dialogue, not shut it down—you engage in criticism to understand not just that a thing has problems, but to seek to understand those problems so you can contribute to a solution

it’s for that reason that the once valid image of a bunch of rich white dudes sitting around smoking cigars in a white tower isn’t accurate anymore. by no means does that mean all problems of systemic inequality are fully “solved”, but we live in a world where academia can and does adjust to criticism, and is now full of diverse perspectives from all intersections of minority voices

but when your approach to criticism is just finding any flaws to declare something wholly “problematic” and the only solution you have is “throw it all out!” “burn it all down!” the fact that institutions of higher learning are flawed and can be criticized leads you to embracing anti-intellectualism. rather than seeing the limitations of privileged perspectives as just that—limitations, which need to be filled out by combining them with perspectives that historically were overlooked—any perspective that may have been privileged in the past becomes trash that needs to be thrown out entirely

#discourse is the mind killer#the left#leftist#leftwing#leftism#academia#higher learning#education#anti-intellectualism#women in stem#queer studies#feminist critique#literary criticism#media criticism#critique#critical theory

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pat's Shirts: An Extended Analysis

Since Bad Buddy's on the brain, I'd like to present an analysis of a show through a Pat's-shirts-centered critical lens.

Literature review: Many very smart people that I will try to link to have analyzed Bad Buddy through this lens already, but I would like to contribute to the discussion, specifically focusing on the iconography and text on the shirts. For great analysis that also incorporates colour, look to @dribs-and-drabbles whole series (x). Thesis statement: Pat's shirts convey his inner thoughts directly to the audience, generally going unnoticed by other characters, like a soliloquy. They provide insight into his emotional state and aspirations as they shift throughout the stages of his narrative arc.

Pran is more reserved about his feelings, and often expresses them through external signs such as the smiley face on his door. Pat can also be interpreted through the same lens, using external signifiers such as t-shirts to show what he is thinking. Pat is so expressive that he needs to literally wear his feelings on his sleeve (or chest).

In the first several episodes, there is a sense of optimism and possibility. In episode 1, Pat wears a shirt that reads "turn up the saturation" while talking with Pa in his old room. He looks over at Pran's house, Pran obviously on his mind. This showcases how things are just getting started. His feelings for Pran have been reignited after seeing him on campus. Pat wants to turn up the saturation in his life, make it more vivid, and already he's connecting that sentiment to Pran.

The feeling of hopefulness continues when Pat wears his Lucky (Charms) shirt. When their friends get into another fight, while Pat's wearing this shirt, his professor tells them they're lucky no one got seriously hurt, but there's more luck at play in this moment; they're lucky that they have found each other and are in each other's lives again. They have their first real conversation while they're patching themselves up, where they decide to work together to stop their friends from fighting and exchange chat IDs. Things are (slowly) starting to come together.

Pat next wears a Tim Hortons shirt from the Smile Cookie charity campaign. This is an interesting adaptation of Pran's signature motif, Pat mirroring the smiley faces that Pran surrounds himself with. Pat wears this shirt when they eat together at the food truck, so the food-related shirt is thematically relevant, especially one associated with sharing and giving. Pat and Pran share food (or more accurately, Pat steals Pran's wonton) but it’s a playful moment that they'll return to later in the show when Pran gets an extra wonton for Pat to steal. The shirt represents Pat's happiness at being close to Pran again, at being back in the game they play.

The optimism embodied in these shirts is also reflected in a shirt that Pat doesn't wear yet, but is instead hinted at. On top of Pat's pile of laundry is another smiley face shirt that he will wear five years later in the finale. Pat holds onto this shirt that represents Pran and his aesthetic, long before they start dating. The teasing of this shirt is the ultimate symbol of optimism, brimming with possibility.

We then move on to Pat's confusion and realization arc. The first shirt I'd like to discuss is the Salome shirt he wears at the photoshoot with Ink. There are two literary and artistic references here: Salome, the biblical story and its adaptations, and Picasso's painting of his close friend Jaime Sabartés.

Picasso painted many portraits of Sabartés, and dedicated many more to him, but this specific painting is from 1939, humorously portraying Sabartés as a sixteenth-century courtier. This might reflect Ink and Pat's relationship in this moment. Ink gives Pat this shirt, putting him into a costume like Picasso did with Sabartés, and there is an interesting juxtaposition between subject and artist at play.

Sabartés recalled about a previous painting, “When he put the painting up on the easel, I was astonished to see myself … the spectre of my solitude, seen from without.” About the 1939 painting, he wrote, "[it] has all the characteristics of my physiognomy, though only the most essential ones. If the way Picasso put them together does not coincide with the way the majority of people see them, this is because, thinking about me, he took them from his memory, with the intention of giving them form in a picture […] while people who look at me directly as I am forget me when they are trying to remember me." (x)

This is reminiscent of the way that Ink seems to knows Pat's feelings maybe more than he knows himself and her lack of surprise that Pat and Pran get along. From her perspective, they have always been friends. As artists, Ink and Picasso see their subjects in a different light. It is in direct relation to Ink that Pat comes to realize his feelings for Pran, by testing out Pa's patented technique. This whole situation discombobulates him, which is captured in Picasso's Cubist style.

The second aspect of the shirt is the biblical story of Salome. @dribs-and-drabbles (x) made the excellent connection between the femme fatale in this story to the faen fatale in Bad Buddy (Ink), although Bad Buddy explicitly subverts this trope. I also find it interesting that one of the most famous adaptations of Salome was written by Oscar Wilde, so some queer connection could be teased out. It is also worth noting that one of the themes of the play is the dangers of looking, especially since the shirt is worn during a photoshoot. Herod begs Salome to free him of his promise, apologizing for looking at her too much: "Neither at things, nor at people should one look. Only in mirrors should one look, for mirrors do but show us masks." Perhaps Pat can also be seen as wearing a mask, one he is not aware he is wearing all the time.

There seems to be little connecting Salome and Picasso that I could find, though both are playing with ideas of historical adaptation, from the biblical play to Sabartés in costume. Bad Buddy also toys themes of the past as Ink is introduced, casting new light both on Pat and Pran's historical relationship and their relationship now.

The next shirt is another one that is given to Pat. Pat borrows the friend/unfriend shirt from Pran when he sleeps over in Pran's room. They are figuring out how to relate to each other, and especially in this scene, how the other feels about Ink. Pat wears this shirt on a "date" with Ink at the food truck, another relationship that he is trying to determine how he feels. The friend/unfriend shirt reflects a pivotal question about Pat and Pran's relationship. They are not friends, but what does that make them instead? What is "unfriend", the negation of friend? Is it enemy? Is it lover? They both desperately need it to be something, to be in each other's lives in some way.

During and after his next "date" with Ink, Pat wears a black shirt with an abstract face on the front. This echoes the Cubist style of the Picasso shirt. However, in this design, the face is even more abstracted, configured with just a few white lines on a black background in unrealistic proportions. Just as the Picasso shirt implied Pat's burgeoning confusion, here he is slammed with the new revelation that he likes Pran as more than a friend. @dribs-and-drabbles pointed out the splash of red right over his heart, signifying his newly discovered feelings (x). This design is stark, impressionistic, boiled down to the bare essentials of a face and disassembled. Pat is taken apart and feeling lost knowing how much he wants Pran. The shirt speaks to the confusion Pat feels in this moment.

The next phase is about yearning and seeking connection. Pat knows how he feels about Pran; he has fallen, and fallen hard. Now that he has discovered this, he changes into the Baseball Mom shirt to tell Pran of his feelings on the rooftop. In this scene, Pat tells Pran he doesn't want them to just be friends, and through his shirt he tells Pran he sees a future with him. The shirt evokes a future of love and family (though not confined to the heteronormative idea of family). It is about closeness and partnership and possibilities.

During the flirt-off, Pat shows up to the Kwan and Riam audition with a blue shirt mostly covered by a burgundy button-up. The only clearly visible words are "YOUR / MAN?" This is a declaration, he wants to be with Pran. He's asking, can I be your man? as @dribs-and-drabbles writes (x). He's almost staking a claim on Pran, but subverts this by instead declaring himself to be Pran's, similar to when he cedes the competition to Pran.

Looking at the text more closely, however, a few words are visible. The shirt has a quote from On the Road by Jack Kerouac: "What's your road, man? - holyboy road, madman road, rainbow road, guppy road, any road. It's an anywhere road for anybody anyhow. Where body how?" Combining the full text and the selective framing visible on screen, Pat seems to be asking to go on this road together, wherever it may lead.

Once Pat and Pran start dating, Pat's shirts reflect the joys and tribulations of a newly established relationship. He wears the "Proud to be a [Noles] Hater" when practicing the play with Pran. Pride is written clearly on his chest, but it also hints to insecurities. Pat is being perhaps too proud for Pran, posting pictures on Instagram and flirting to openly. Moreover, this shirt is a reference to the sports rivalry between the University of Miami and Florida State University, and as the previous scene showed Pat playing rugby, the shirt signals the continuing rivalry between the architecture and engineering faculties. The theme of rivalry is also ever-present in their families' rivalry, which as @dribs-and-drabbles discusses (x), originated with university. This showcases that while Pat and Pran are happy together, there are external forces working against them.

After a tense argument with his father, Pat wears a white shirt with [SELECT] written on the front. In this scene, Pat is asking Pran to choose him—to select him. The framing of the text in square brackets is also reminiscent of a hyperlink or code, perhaps further emphasizing the act of clicking/selecting. He wants comfort from Pran but is unwilling to ask for it directly, to bother him with his problems. Pran hears the unspoken message and comes home to cheer Pat up, prioritizing him.

When Pat gets out of the hospital, Ming surprises them both by thanking Pran for helping Pat get his name cleared. During this scene, Pat wears his California shirt, which @karometeenk has deciphered. To summarize, it is a slogan for a German pharmacy that reads "Here I am human, here I shop" which is a play on the Faust quote which can be translated as "Here I am human, here I can / am allowed to be one" (full credit to @karometeenk for translation and analysis, along with @dribs-and-drabbles and @airenyah's discussion (x) (x) (x). There is something sinister underneath this message. This shirt alludes to Pat's desire to escape, to be free, but also signals the obstacles to this, especially as he wears this when talking to his dad, who seems to be behaving decently, but there will be future complications. The slogan appropriates a quote about one's humanity commodified to sell products, commercializing people's identity. While Pat and Pran are happy together, they cannot yet just be.

The theme of seemingly cheerful shirts with a sinister undertone continues later in the episode. Pat wears a shirt with the words "SUN SUN SUN", reflecting the happiness he feels to be with Pran, as well as directly mirroring Pran's "radiate positivity" rainbow shirt. Together they depict the sun emerging after a period of rain. However, the optimism conveyed by these shirts is undermined by the peril they find themselves in, the danger of getting caught in Pran's father's office and the looming revelations about their families' rivalry that could destroy their relationship. The storm is not yet over.

You may be wondering why I have skipped over a crucial subsection of Pat's wardrobe: his Hawaiian shirts. Fear not! I would like to discuss these shirts collectively, as they convey a similar theme that does not fall neatly into the chronology of the other shirts. They reflect an idea that the show keeps returning to every time Pat wears them. They stand outside of time.

These shirts symbolize hope and yearning, but they are often tainted by a feeling of despair and desperation. Dreams thwarted. These shirts are aspirational for Pat, conveying the sense of peace and freedom that he wants but cannot yet achieve. He often wears them in moments of crisis. In episode 5, Pat wears the blue pineapple shirt when he gets in the fight with Wai. He is seeking clarification about their relationship but winds up in a physical altercation and Pran leaves without giving him any answers.

He wears the Golden Gates Bridge shirt when he gets shot—this was a chance to reconcile their two friend groups, but it ends in disaster. However, in the end, that event literally builds bridges between them (I am including this shirt in this section though it may not be a Hawaiian shirt). The elephant shirt Pat dons in episode 11, as @dribs-and-drabbles has discussed (x), shows Pat wanting to forget, wanting to start anew on the beach with Pran without their families interfering, but the elephants belie this message as elephants never forget.

Pat wears a lot of Hawaiian shirts at the beach, both times. On the first beach trip, there is a feeling of opportunity, now that they have kissed. But at the same time, while Pat wants Pran to open up to him more, Pran is trying to protect himself. The beach symbolizes a chance at freedom, a chance to be open about their feelings. It makes sense that Pat would wear these shirts there. Except they are not confined to the beach, they traverse space and time.

I'd like to look specifically at the shirt Pat wears when he runs away. He is wearing it when his dad finds them together at the mall, and during the confrontation with both their parents. Here in the city it seems out of place, but it reflects Pat's desperation to love Pran freely, to escape the restrictions being placed on them. And then they do escape to freedom, to the beach where there is hope that they can be together, and Pat continues to wear the shirt. It depicts a dream that seems so close to being realized.

When they get back home, Pat is once again wearing the shirt he wore when they ran away. Nothing has really changed, despite their temporary escape, the same problems with their families persist. The repetition of the shirt brings this message home. But it also an interesting choice for both of them to wear the same shirts, it feels intentional. Like a disguise. They are going home, pretending that nothing has changed, that they broke up, but are keeping the truth hidden.

The shirt Pat wears in the finale is a callback to the first episode when we saw it in Pat's laundry basket. Pat has incorporated Pran's style into his own, reflecting smiles back at him. He wears it in front of his family, a hidden signal of their relationship. This shirt shows that the optimism of before paid off, that they can achieve the open-ended future they are fighting for. That there is hope.

#bad buddy#on this rewatch i analyzed the show using 2 critical lenses#1. literary allusions and queer theory#and 2. pat's shirts#how is this the longer meta of the 2 i wrote this weekend? it was supposed to be a joke#sometimes i just like to have thoughts recreationally#bad buddy series#bad buddy meta#bad buddy shirts#thinking thoughts#thai drama fashion#bad buddy the series

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

Could you please interrogate why you need this thrice-heterosexual white billionaire to be sapphic, please? Could you please ask yourself why you *need* it so badly? Please?

#Taylor Swift critical#anti Taylor Swift#except it’s really more anti-her-fanbase#it is completely valid to have queer readings of cishet artists’ work#(I do it!)#but if she and her camp have come out *three times* to deny her being sapphic (&c.)#you need to consider that your theories are rooted in white supremacy and classism!#racism mention#antisemitism mention#(because so much of it is not just racism but antisemitism too)

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

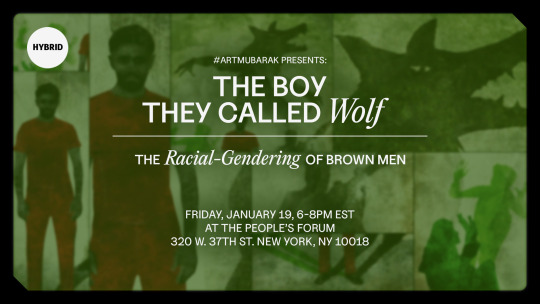

THE BOY THEY CALLED WOLF: THE RACIAL-GENDERING OF BROWN MEN

We are witnessing the horrific genocide of Palestinians in real-time, with watchdog groups around the world denouncing Israel’s siege and urging for ceasefire and humanitarian aid. But notably absent from the discussions around relief are Palestinian and more broadly Arab and brown men and boys.

Brown womenandchildren are subject to a default perfect victimhood, whereas the brown man is already dangerous, killed for his “yet-to-be-committed errors.” The “womenandchildren” framing assumes that brown men are less worthy of life, that it is not also a horror to slaughter our brothers and fathers and husbands.

This event outlines the myriad ways in which brown men are subjected to Orientalist depictions such as hypersexual, savage, and brutish, and examines how these caricatures serve to dehumanize brown men and justify their maiming and extinction. We will also explore brown men in relation to brown women and marginalized genders, and what constitutes the “perfect victim” in the eyes of the colonizer.

Friday, January 19, 6-8PM EST

The People's Forum

320 W. 37th St., New York, NY 10018

RSVP here!

This event has a hybrid option for those unable to attend in-person.

#palestine#critical race theory#gender studies#orientalism#the people's forum#queer theory#intersectional feminism#please come. rare celicalms public appearance

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chap 12. Melancholy Natures, Queer Ecologies by Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands (part 3, final)

Queer Ecologies

‘what it might mean to inhabit the natural world having been transformed by the experience of its loss’?

‘[the queer artist's] natures are not saved wildernesses; they are wrecks, barrens, cutovers, nuclear power plants: unlikely refuges and impossible gardens. But they are also sites for extraordinary reflection on life, beauty, and community’ (344)

AIDS and Other Clear-Cuts

The artist (Jan Zita Grover’s North Enough) writes about moving from San Francisco, where she has worked as a personal caregiver to many individuals who were dying, and died of, AIDS, eventually to the woods of Northern Wisconsin and Minnesota hoping for ‘a geographic cure’ to her burnout and grief. (344)

‘in their persistence [grief, mourning], generate a form of imagination—an awareness of the persistence of loss—that allows her to conceive of the natural world around her in ways that challenge the logic of commodity substitution characterizing contemporary relations of nature consumption” (344)

“The north woods did not provide me with a geographic cure. But they did something much finer. Instead of ready-made solutions, they offered me an unanticipated challenge, a spiritual discipline: to appreciate them, I needed to learn how to see their scars, defacement, and artificiality and then beyond those to their strengths—their historicity, the difficult beauties that underlay their deformity. AIDS, I believe, prepared me to perform these imaginative feats. In learning to know and love the north woods, not as they are fancied but as they are, I discovered the lessons that AIDS had taught me and became grateful for them” (344)

Rather than the landscape of her dreams, the land looks more like a candidate for reclamation. Through Grover’s research we learn that the region is one that been ‘systematically abused: logged several times, drained, subjected to failed attempts at agriculture, depleted, abandoned, eroded, invaded, neglected.”

Jack pines are predominant in the region; tenacious, ‘the first conifers to reestablish themselves after a fire” (16), in their own way remarkable even as they are useless for lumber, short lived, and not at all the sorts of trees about which adjectives like ‘breathtaking’ circulate” (345) they are a loud testament to the violence that has generated them.

“the diminishment of this landscape mortified and disciplined me. Its scars will outlast me, bearing witness for decades beyond my death to the damage done here” (20) But still: the love emerges, painfully, gradually, intimately. (345)

She experiences the landscape in terms of loss and change, rather than idyll and replacement. It is all personal; it is all about developing a way of making meaning that recognizes the singularities of the past and takes responsibility for the future in the midst of intimate devastation. (345)

‘Environmental hubris’—fly fishing, the introduction of non-native fish to the river, changing temperatures of rivers caused by logging and diversion; specific policies, politics, and technologies that have had effects on the rivers, the fish, and the other species throughout the river and the north woods (356)

A refusal to demonize the ‘invasive’ species; Grover herself is ‘invasive’ both culturally and personally (white settlers and big city imports) thus her ethical claim is not for purity but for an active and thoughtful remembering of historical violences in the midst of ongoing necessity of movement and change (346)

Seek relationships with Clear-cuts and landfills in order to bring to the foreground the massive weight of human devastation of the natural world; “a discerning eye can see how unstewarded most of this land has been. The charm lies in finding ways to love with such loss and pull from it what beauties remain” (81) (347)

“she does not romanticize the dying even as she might mourn their loss to the world; instead [through Grover] we witness each loss as particular, irrevocable, and concrete: she is their witness” (347)

Can we learn to see these landscapes as creation as well as destruction?

Rather than mourn the loss of the pristine, she carefully cultivates an attitude of appreciation of what lies before her, beyond the aesthetic wilderness to the intricate details of human interactions with the species and landscapes of the region. In this manner she comes to be able to find the beauty in, for example, landfills and clearcuts; far from naivete or technophilia, this ability is grounded in a commitment to recognizing the simultaneity of death and life in these landscapes, the glut of aspen-loving birds in the clear-cut, the swallows, turkey vultures, and bald eagles near the landfill.

--

It is necessary to face our fear and pain; we have to make room in our relationships with the natural world, queer and otherwise, for the recognition that that is what we might be feeling in the first place (355)

#queer ecologies: sex nature politics desire#queer ecology#queer theory#ecofeminism#critical ecology#environmental politics#ecology#aids crisis#mourning nature#ecogrief#colonialism#environmental degradation#melancholia#queer politics#melancholy#environmentalism#climate and environment#environmental justice#forests

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almost all the media coverage of AIDS has been aimed at the heterosexual groups now minimally at risk, as if the high-risk groups were not part of the audience. And in a sense, as Watney suggests, they’re not. The media targets “an imaginary national family unit which is both white and heterosexual” (p. 43). This doesn’t mean that most TV viewers in Europe and America are *not* white and heterosexual and part of a family. It does, however, mean, as Stuart Hall argues, that representation is very different from reflection: “It implies the active work of selecting and presenting, of structuring and shaping: not merely the transmitting of already-existing meaning, but the more active labour of *making things mean*” (quoted p. 124). TV doesn't make the family, but it makes the family *mean* in a certain way. That is, it makes an exceptionally sharp distinction between the family as a biological unit and as a cultural identity, and it does this by teaching us the attributes and attitudes by which people who thought they were already in a family actually only *begin to qualify* as belonging to a family. The great power of the media, and especially of television, is, as Watney writes, “its capacity to manufacture subjectivity itself” (p. 125), and in so doing to dictate the shape of an identity. The “general public” is at once an ideological construct and a moral prescription. Furthermore, the definition of the family *as an identity* is, inherently, an exclusionary process, and the cultural product has no obligation whatsoever to coincide exactly with its natural referent. Thus the family identity produced on American television is much more likely to include your dog than your homosexual brother or sister.

—Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?” (1987)

#queer theory#queer studies#HIV/AIDS#1980s#reaganism#leo bersani#stuart hall#cultural studies#critical theory#intellectual history

23 notes

·

View notes