Link

0 notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Analysis of My Name is Pauli Murray

“You can’t teach American history without talking about Pauli Murray,” we’re told early on in “My Name is Pauli Murray.” By the end of viewing this documentary, you may have the same sentiment. Pauli Murray narrates her extraordinary life that went on to inspire students, civil rights leaders and future Supreme Court justices.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Thurgood Marshall used Murray’s ideas and research in their most famous court cases. The filmmakers also drew attention to how forward thinking Murray’s ideas were, showing how they were used by the ACLU as late as 2020 to ensure LGBTQ+ rights. And this is just some of the accomplishments highlighted in this documentary.

In 74 years of life, Pauli Murray was a lawyer, poet, activist, teacher and Episcopalian priest, becoming the first Black woman to become ordained in the church. Murray was also what we would now refer to as non-binary, proving that this is something that has existed even before there was the language to openly talk about it. We discover that Murray did try to express it, and at one point sought out exploratory surgery to see if undescended male genitalia were present. At times, and for safety during the Depression-era days of riding the rails, Murray’s appearance and dress was that of a teenage boy. Letters reveal someone who felt they were in the wrong body.

Something that was never disclosed in those letters were preferred pronouns, assumably because this was not an idea that existed during her time. Biographies refer to Murray with she/her pronouns, something she did in her own memoir. The directors give time to a non-binary activist who acknowledges the use of feminine pronouns but decides to use “they” when they refer to Murray. In any other situation, I would ask one’s pronouns, but this is not a possibly, thus, I will use I will use “she” and “her” here, with no malice or disrespect intended.

In fact, there’s a section of the documentary that’s all about identification and how the perceived wrong terminology can foster dissent. Murray taught students in the 60s, bringing with her decades of firsthand knowledge and expertise surrounding civil rights. Yet the students rejected her preference for using “Negro” instead of “Black,” going so far as to label their professor an Uncle Tom. We are told why behind this—“black” was never capitalized and was therefore considered demoralizing—but this was the “Black is Beautiful” era and, as one friend points out, these students were as fiery and outspoken as Murray was 30 years prior when Eleanor Roosevelt was getting pelted with typewritten letters chewing out FDR for his half-hearted anti-lynching statements.

From those letters, Murray was able to develop a deep friendship with Mrs. Roosevelt, who became a sort of a mother figure who also shared several life experiences. An example is that they were both orphaned and raised by older relatives. The Murray clan were a multi-ethnic group, some of whom could pass for White, and they all instilled the idea that a woman could do anything. Impressed by her friend’s strong will and fearlessness in confronting anyone regardless of their stature, Mrs. Roosevelt quite often suggested Murray as a valuable resource to people like JFK.

Before continuing, you may be wonder why I’m talking about a non-binary individual in a page attempting to highlight Black women in the LGBTQ+ community. There are a few reasons. To the world, Pauli Murray was a woman, and was treated as such. Sexism came from Blacks as well as Whites. “People talk about Jim Crow,” she wrote, “well, I’m dealing with Jane Crow.” This intersection of race and gender would become a constant talking point for Murray—again, far ahead of the times—and this included some clever uses of the 14th Amendment to force some semblance of equality in the law. After being denied acceptance in a PhD program, she enrolled in Howard University’s law school. “I don’t know why women would even consider the law,” a professor said. And during the first year, Murray “wasn’t even allowed to speak.” After graduating at the top of the class, Murray’s automatic acceptance into Harvard to continue studies was rescinded because it was for men only.

Not only is this a reason to talk about Pauli Murray here, but also because I’m drawing from Patricia Hill Collins and bell hooks and Black Feminist Thought and Collins’ Black Feminist Epistemology. According to Collins and hooks, Black women are agents of their own knowledge. In order to produce Black feminist thought, it requires the epistemology and lived experiences of Black women. Collins used the ‘Standpoint theory” which was introduced by Karl Marx (famous sociologist/theorist) to make her point about how Black women live through a unique and different social lens than people who are not Black women.

As someone who largely lived her life as a Black woman in the United States during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement, Murray’s lived experience was central in her attempts to provide civil rights to the Black community and rights to women in America. Without these experiences, without her wisdom, Black Feminist Thought may not have developed the way it did.

This documentary isn’t just a list of achievements, but it’s also a bit of a love story between Murray and Irene “Renee” Barlow. The two met at the law firm they both worked at, gravitating toward one another because they were two of the few women in a jungle full of men. We hear snippets of a few letters between the two, and Murray mentions her as “my closest friend” on the tapes that were recorded during the writing of a second memoir, Song in a Weary Throat: An American Pilgrimage. When Yale recently created Pauli Murray College, it made the pioneer the first Black and LGBTQ+ person to have an institute named after them.

Before this film, I didn’t know very much about Pauli Murray. It does what all good documentaries do: it made me want to read up and be educated more on its subject. And what a great and inspiring subject Pauli Murray is.

#pauli murray#my name is pauli murray#lgbtq+#lbgtq#gender noncomformity#gender non binary#black women#civil rights#sex rights#gender rights

0 notes

Text

Reblogged from my personal account

Analysis of The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

“If it wasn’t for drag queens, there would be no gay liberation movement.” So says a prominent transgender activist, adding: “Transgender women face the most severe violence within the LGBTQ community.” It’s these two assertions that form the heart and soul of the fascinating documentary “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson.”

By and large the film is seeking to determine who killed Marsha P. Johnson, the transgender LGBTQ+ rights pioneer. It also offers a historical perspective of the gay rights movement, with a very needed focus on transgender activism. It’s also a touching tribute to Johnson, whose body was found floating in the Hudson River in 1992. She had told friends earlier that a car had been following her. The police ruled her death a suicide, but most who knew Marsha dispute that allegation.

“It certainly was not a suicide,” said Randy Wicker, her roommate. “Police made up their mind because to them this was a nobody. This wasn’t a person.” Following her death protests spread in Greenwich Village, with people holding placards that read “Justice for Marsha.” She is depicted, often with flowers in her hair, as a beloved and charismatic figure with a wide, radiant smile.

Director David France (“How to Survive a Plague”) follows Victoria Cruz, from New York’s Anti-Violence Project, as she doggedly works to re-open the cold case and get to the truth.

Johnson was known for how vocal she was when it came to gay rights. She was a prominent figure during the Stonewall Riots in 1969, often credit with being the person to throw the first brick during the ordeal. She also was a founder of the Gay Liberation Front and co-founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with her good friend, Sylvia Rivera.

When thinking about the importance of shedding light to Marsha’s story and the stories of other queer and/or trans Black women, I’m reminded of Stuart Hall and his idea of representation. Stuart Hall believed representation was the “process by which members of a culture use language… to produce meaning”. It is the organization of signs, which we use to understand and describe the world, into a wider set of values of ideologies. These meanings are not fixed or “real”; they are produced and defined by society. In other words, things are given meaning because people give it meaning and these meanings can fluctuate based on the time period, the culture, etc.

Keeping this in mind allowed my viewing experience to be more enjoyable. One reason is because I can see the shift in how a Black trans woman is being represented. Although the documentary focuses on the mystery of Marsha’s death, it also has a powerful urgency as it notes that anti-trans violence is on the rise and a disproportionate number of those assaults and deaths remain unexamined. That escalating violence makes knowing Johnson’s story all the more crucial. The importance of this is how we see a shift in how trans lives, particularly the lives of trans women, is evolving. No longer are people simply brushing it off; people now care about their lives and want to protect Black trans women. The shift in viewing Black trans women as ‘Other’ into viewing them as human beings that deserve rights has begun and is continue to evolve as society becomes more and more progressive, which is a beautiful sight to behold.

Ultimately, the film has some important messages: 1) the early activists in the LGBTQ+ rights movement died for the rights people are able to enjoy now; 2) although the documentary does not offer a definitive answer on the mystery surrounding Johnson’s death, it is able to pay homage to an LGBTQ+ icon that is one of the most important people to come out of the movement; and 3) it is able to trace the tragic trajectory of anti-trans violence that has occurred since her death.

The film is vital for both its history and its currency. Above all, “The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson” works powerfully as a rallying cry for tolerance, love and understanding

#marsha p johnson#the death and life of marsha p. johnson#black women#black trans women#trans#trans rights#protect trans women#lgbtq+#lgbtq#lgbtq+ rights#human rights#civil rights#stuart hall#representation

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analysis of Paris is Burning

Paris Is Burning reveals the world of the “Children,” as Black gay men and women lovingly call themselves. This documentary examines the community’s flamboyant rituals of balls and voguing. It is not only a celebration of queer culture, but a chronicle of overcoming adversity by being vocally unapologetically yourself.

The overarching theme of Paris is Burning revolves around the influence that Black and Latine queer, trans, and gender non-conforming people had on the ballroom and drag scene. This influence stems from the resilience that these communities had in self-affirmation in the face of opposition from those who wanted to deny them their humanity.

The defiant joy we witness in the ball walkers at so many moments of the film, despite the AIDS pandemic, racism, homophobia, transphobia, poverty, homelessness, violence, harassment, addiction, and whatever other hardships they may have been dealing with at any given time, was infectious in 1990, when the film premiered, and remains so today. In this era of fake news, hate speech, anti-trans legislation, the resurgence of white-supremacist ideology, immigration blockades, and mass violence to suppress social change and human-rights advancements, Paris Is Burning still provides a vision of vibrant resistance—a fierce proclamation that queer and trans lives matter, now as they did then. That message, along with the unique performance culture and the everyday lives that Paris illuminates for us, made it a global revelation when it was released and has since elevated it to legendary status.

The film is an education: a way into a lifestyle that even many of us who share an identity with the people onscreen otherwise had no access to, because this culture felt—still feels—so specific to a time and place. Which is part of the reason the movie’s legacy remains so complicated. It was directed by a white filmmaker with relative financial and social privilege: a complete outsider to ball culture. It went on to win a prize at Sundance, get a distribution deal with Miramax, and land raves from publications like the New Yorker and the New York Times—all signs, to some, that the movie was intended from the outset to be consumed by white audiences.

At least one star has spoken out against the film over the years. “I love the movie. I watch it more than often, and I don’t agree that it exploits us,” said LaBeija, mother of the House of LaBeija, and one of the documentary’s most memorable storytellers, to the New York Times in 1993. “But I feel betrayed. When Jennie first came, we were at a ball, in our fantasy, and she threw papers at us. We didn’t read them, because we wanted the attention. We loved being filmed. Later, when she did the interviews, she gave us a couple hundred dollars. But she told us that when the film came out, we would be all right. There would be more coming.” The film went on to make $4 million, according to Miramax, and a battle raged between some of the featured performers and the distributor over compensation. In the end, about $55,000 was divided among 13 performers, based on screen time.

Another problem with Livingston’s depiction of the ballroom and drag culture is that it virtually erases the impact that Black queer women and gender nonconforming people had in the scene. Although some were featured in the documentary, such as Octavia St. Laurent, they were relegated to such little screen time that you could’ve blinked and missed them.

I’m reminded of bell hooks and her works surrounding Black Feminist Theory and oppositional gaze and how this influenced how I consumed this piece of media. The idea that the liberation of Black women would lead to the liberation of all people was something that hooks felt really strongly about and this documentary was an opportunity to not only uplift the LGBTQ+ community, but to uplift Black women. And, as is usually the case, Black women were forgotten.

bell hooks was the founding mother of a critical discussion that focused on the role of the black female spectators and their relation to white and black representation on film. She contends that, despite a long history of oppression on screen and in real life, black people had the right to gaze, or observe, and at times this right was repressed, leading to a further ‘rebellious desire’ to gaze. This rebellious desire of looking is what hooks defined as ‘the Oppositional Gaze’. With this gaze, Black women can have the opportunity to be critical of Paris is Burning, because although it is important, it is not enough. Representation matters. Inclusivity matters. This is a start, but should NOT be the end.

#paris is burning#documentary#analysis#lgbtq+ community#lgbtq#lgbtq+#ballroom#drag#ball#black women#trans#nonbinary#gender noncomformity#representation#bell hooks#black feminist theory#oppositional gaze

15 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Dr. Rosalind Rosenberg discusses how she came to write about the remarkable life of Pauli Murray and the struggle of gender identity. Dr. Rosenberg specializes in women's, social, and legal history and is currently Professor Emeritus at Barnard College.

0 notes

Video

youtube

Why You Should Know About Marsha P. Johnson

1 note

·

View note

Photo

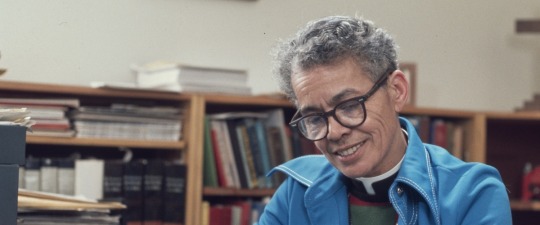

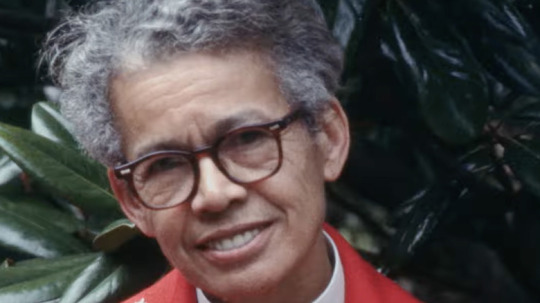

Pauli Murray was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1910. She was assigned female at birth, and felt her gender was only understood by a few people.

Pauli graduated from college in 1933, one of four black students in a class of 232. After being rejected from further study at the University of North Carolina on account of his race, she became involved with the NAACP, and eventually returned to university to study law, graduating top of her class in 1944.

During her time at university, Pauli pioneered a new strategy of fighting racial segregation through protesting its unconstitutionality, which would eventually be successfully used in the 1954 landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education, which ruled the segregation of public schools unconstitutional.

Pauli passed the bar exam in California in 1945 and began working as a lawyer. She focused her work on fighting for civil rights and women’s rights, and wrote on intersectionality, pioneering the concept of “Jane Crow” to explain to dual oppression experienced by African-American people assigned female at birth. He also penned States’ Laws on Race and Color - a foot-thick book referred to as the Bible of civil rights legislators.

In 1973, Pauli’s partner Renee passed away from a brain tumor. Following this, Pauli, who had always been Episcopalian, began to study to join the priesthood - although people assigned female at birth could not be admitted at the time. She finished his coursework in 1976, and in 1977, when people assigned female at birth were allowed to become Episcopalian priests for the first time. Pauli was ordained, becoming the first black person assigned female at birth to do so.

Pauli passed away in 1985, aged 74. Her groundbreaking legal theories and ideas about intersectionality remain as important today as they were over 50 years ago.

#pauli murray#my name is pauli murray#queer representation#lgbtq+#lgbtq#lgbtq+ rights#lgbtq rights#trans man#trans#transgender#black trans man#gender noncomformity

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

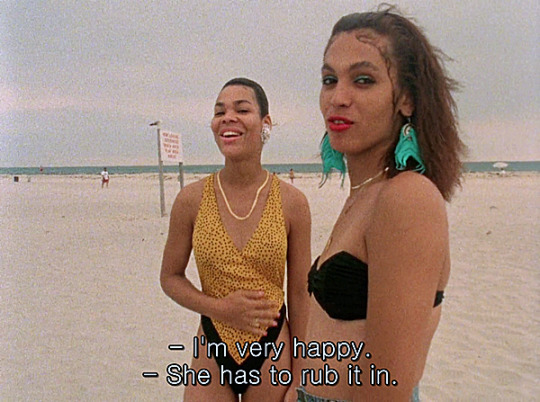

This documentary highlighted members of the LGBTQ+ community, particularly drag queens in the ballroom scene. Here, we see some exposure for Black trans women that are part of the community.

Paris Is Burning (Jennie Livingston, 1990)

15K notes

·

View notes

Photo

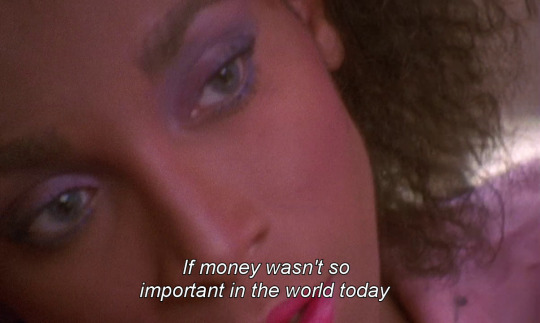

Octavia St. Laurent, Paris is Burning (1990)

Octavia rose to prominence due to being part of in the House of St. Laurent and their involvement with voguing and the Harlem ballroom scene.

Octavia would go on to give educational talks about HIV and being transgender.

Source: https://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/22663/1/octavia-st-laurents-last-interview

#octavia saint laurent#paris is burning#house of st laurent#voguing#ballroom#harlem ballroom#hiv#transgender

499 notes

·

View notes

Video

Reblogging from my original account to this account

Scenes from the 1969 Stonewall uprising. Footage courtesy of The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson

Source: Reuters Graphics

#stonewall riots#marsha p johnson#lgbtq#lgbtq+#lgbtq+ community#the death and life of marsha p. johnson#black woman#trans woman#black trans woman

250 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Marsha P. Johnson, was an American gay liberation and trans rights activist. She was one of the founders of the Gay Liberation Front and co-founded Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (S.T.A.R.) with her close friend and fellow activist, Sylvia Rivera, as a way to help trans youth.

Sources: https://ucnj.org/mpj/about-marsha-p-johnson/ ; https://wams.nyhistory.org/growth-and-turmoil/growing-tensions/marsha-p-johnson/

#marsha p johnson#gay liberation#trans rights#trans activism#black woman#s.t.a.r#sylvia rivera#lgbtq#lgbtq+#gay liberation front#trans black woman

8 notes

·

View notes