#Classical Manuscripts Ancient Literary Collections

Text

World’s oldest libraries

The World’s Oldest Libraries

Article Title: World’s oldest libraries

Author: Nicky Sinha Francis

Genres: Article

A heaven of books

When your world revolves around books, all you can think of a cozy beautiful place only for your books and you. For others, it’s point to laugh, but for you it’s your passion and your own personal space where you can escape from your stress and pain that you go…

View On WordPress

#Ancient Archives Library Origins#Ancient Knowledge Centers Heritage Libraries#Ancient Libraries#Antiquarian Libraries Oldest Manuscripts#Classical Libraries#Classical Manuscripts Ancient Literary Collections#Cultural Heritage Libraries Ancient Text Repositories#Early Library Collections#Historical Libraries#Legacy Libraries#Library History#Library Preservation#Medieval Libraries#Pre-modern Libraries

0 notes

Text

🍅🦇 @birdietrait did someone say vampire ?

Josiah, formerly known as Jafaar, carries the weight of centuries on his shoulders, a vampire born in the desolate landscapes of Somalia, forever bound to the shadows after a fateful encounter in the mid-1720s. Captured and turned by a Syrian vampire, he was whisked away to the unfamiliar terrain of Syria, where he was reluctantly introduced to a royal vampire family.

In his formative years, Josiah immersed himself in the pursuit of knowledge, studying languages and literature, and clandestinely devising intricate plans for the royal family that held him captive. However, the flame of his ambition was extinguished when the longing to find his birth parents, a desire he had harbored since adolescence, was abruptly silenced.

Growing up as an oppressed and envious teenager, Josiah transformed into a bitter young adult, seeking refuge in the intellectual haven of Europe—specifically England—during the mid-1840s. University life exposed him to capitalist and economist ideologies, molding his worldview as he delved into the intricacies of societal structures.

His journey into the nocturnal realm began with a sinister twist, as his first taste of blood was drawn from one of his professors. A predator in the shadows, he continued his nocturnal pursuits without ever being exposed. As the decades unfolded, he evolved with the changing times, returning to Somalia in the 1970s with a desperate quest to reunite with his birth parents, only to be met with the harsh reality of their long-departed lives.

Returning to the United States, Josiah adapted to the ever-evolving social landscape of the 21st century, attempting to blend in with the trends and norms of the time while clinging to his deep-seated beliefs. His younger sister, a relentless force of change, compelled him to undergo a transformation – tattoos, piercings, a new hairdo, and a wardrobe overhaul – all in an attempt to assimilate into contemporary society. Yet, beneath the superficial alterations, Josiah longs for the simplicity of his original attire, appearing almost robotic in his detachment from the ever-changing fashions.

In the present day of 2023, Josiah finds himself in the forgotten hollow, a place that holds a singular purpose for him. With an enigmatic goal set firmly in his immortal mind, he navigates the delicate balance between adapting to the current era and preserving the essence of his timeless existence, forever haunted by the echoes of his past and the insatiable thirst for the unknown.

TRIVIA:

Fashionable Anachronism: Despite his sister's attempts to modernize his appearance, Josiah secretly hoards a collection of clothing from various eras, finding comfort in the timeless elegance of garments that reflect the epochs he has traversed.

Literary Pursuits: Josiah's love for languages and literature extends beyond his mortal life. He has amassed a private library filled with rare manuscripts, preserving the stories that have shaped his understanding of the world. One of his prized possessions is an ancient tome written in a language long forgotten by mortals.

Musical Tastes: While he outwardly adapts to the music of the modern era, Josiah secretly cherishes classical compositions from his youth. He has been known to haunt hidden concert halls, drawn to the haunting melodies that echo the melancholy of his immortal existence.

Hidden Talents: Josiah possesses a keen talent for calligraphy, a skill he developed during his youth while studying languages. He often spends the quiet hours of the night crafting intricate scripts and inscriptions, each stroke a testament to his centuries-long pursuit of perfection.

Artistic Reflections: In a concealed chamber of his dwelling, Josiah maintains a gallery of portraits capturing moments from his past. Each painting tells a silent tale of the people he has encountered and the cities he has watched evolve, providing a haunting backdrop to his eternal existence.

Nocturnal Philanthropy: Unbeknownst to the mortal world, Josiah channels his capitalist inclinations into philanthropic endeavors during the night. He discreetly funds projects that align with his vision of societal improvement, drawing from the wealth accumulated over centuries.

Unquenchable Thirst for Knowledge: Josiah is a perpetual student of the world, and he continually enrolls in university courses under various aliases. His insatiable thirst for knowledge spans disciplines, from cutting-edge technology to ancient philosophies, allowing him to seamlessly blend into different intellectual circles over the years.

Classical Arabic: Being born in Somalia and later taken to Syria, Josiah mastered Classical Arabic, delving into its rich literature and linguistic nuances.

Syriac: A language with historical significance in the region, Josiah became fluent in Syriac during his time in Syria, connecting with the ancient roots of the supernatural world.

Latin: As a young adult in Europe during the mid-1840s, Josiah immersed himself in the study of Latin, a language that granted him access to the scholarly and philosophical works of the time.

English: Moving to England for university, Josiah not only learned English but excelled in it. His linguistic proficiency allowed him to navigate the rapidly evolving social and intellectual landscape of 19th-century England.

French: Embracing the cultural diversity of Europe, Josiah added French to his repertoire, finding himself captivated by the elegance of the language and its literary treasures.

Somali: Despite his nomadic existence, Josiah retained a deep connection to his roots, maintaining fluency in Somali to honor his heritage and communicate with those from his homeland.

Italian: In his pursuit of art and culture, Josiah picked up Italian during the Renaissance, allowing him to appreciate the masterpieces of the era and connect with the intellectual elite.

Spanish: Venturing into the exploration of the New World, Josiah acquired fluency in Spanish, enabling him to engage with the diverse cultures and civilizations flourishing in the Americas.

German: With a keen interest in the economic and philosophical discourse of the time, Josiah became fluent in German, immersing himself in the works of influential thinkers from the German-speaking world.

Mandarin Chinese: Embracing the advancements of the 20th century, Josiah learned Mandarin Chinese, recognizing its growing importance on the global stage and adapting to the changing geopolitical landscape.

#ts4#ts4 cas#ts4 screenshots#ts4 screenies#kristen's.sims#s: josiah#*coven of simblrs#he's dark academia coded.. very game of thrones#but his sister 😶 is like “get a fucking iphone we live in a society now”#he aspires to be a psychologist but who knows if he's set for that..#he has a love-hate relationship with his “family”

60 notes

·

View notes

Photo

National Library Lovers Month: Nonfiction

The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree

Famed across the known world, jealously guarded by private collectors, built up over centuries, destroyed in a single day, ornamented with gold leaf and frescoes, or filled with bean bags and children's drawings--the history of the library is rich, varied, and stuffed full of incident. In The Library, historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen introduce us to the antiquarians and philanthropists who shaped the world's great collections, trace the rise and fall of literary tastes, and reveal the high crimes and misdemeanors committed in pursuit of rare manuscripts. In doing so, they reveal that while collections themselves are fragile, often falling into ruin within a few decades, the idea of the library has been remarkably resilient as each generation makes - and remakes - the institution anew. Beautifully written and deeply researched, The Library is essential reading for booklovers, collectors, and anyone who has ever gotten blissfully lost in the stacks.

The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu by Joshua Hammer

In the 1980s, a young adventurer and collector for a government library, Abdel Kader Haidara, journeyed across the Sahara Desert and along the Niger River, tracking down and salvaging tens of thousands of ancient Islamic and secular manuscripts that had fallen into obscurity. The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu tells the incredible story of how Haidara, a mild-mannered archivist and historian from the legendary city of Timbuktu, later became one of the world’s greatest and most brazen smugglers.

In 2012, thousands of Al Qaeda militants from northwest Africa seized control of most of Mali, including Timbuktu. They imposed Sharia law, chopped off the hands of accused thieves, stoned to death unmarried couples, and threatened to destroy the great manuscripts. As the militants tightened their control over Timbuktu, Haidara organized a dangerous operation to sneak all 350,000 volumes out of the city to the safety of southern Mali.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean

On the morning of April 29, 1986, a fire alarm sounded in the Los Angeles Public Library. As the moments passed, the patrons and staff who had been cleared out of the building realized this was not the usual fire alarm. As one fireman recounted, “Once that first stack got going, it was ‘Goodbye, Charlie.’” The fire was disastrous: it reached 2000 degrees and burned for more than seven hours. By the time it was extinguished, it had consumed four hundred thousand books and damaged seven hundred thousand more. Investigators descended on the scene, but more than thirty years later, the mystery remains: Did someone purposefully set fire to the library - and if so, who?

Weaving her lifelong love of books and reading into an investigation of the fire, award-winning New Yorker reporter and New York Times bestselling author Susan Orlean delivers a mesmerizing and uniquely compelling book that manages to tell the broader story of libraries and librarians in a way that has never been done before.

Library: An Unquiet History by Matthew Battles

Through the ages, libraries have not only accumulated and preserved but also shaped, inspired, and obliterated knowledge. Now they are in crisis. Former rare books librarian and Harvard metaLAB visionary Matthew Battles takes us from Boston to Baghdad, from classical scriptoria to medieval monasteries and on to the Information Age, to explore how libraries are built and how they are destroyed: from the scroll burnings in ancient China to the burning of libraries in Europe and Bosnia to the latest revolutionary upheavals of the digital age. A new afterword elucidates how knowledge is preserved amid the creative destruction of twenty-first-century technology.

#national library lovers month#libraries#books & libraries#nonfiction#nonfiction reads#nonfiction books#book recommendations#reading recommendations#book recs#reading recs#TBR pile#tbr#to read#booklr#book tumblr#library blog#book blog

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

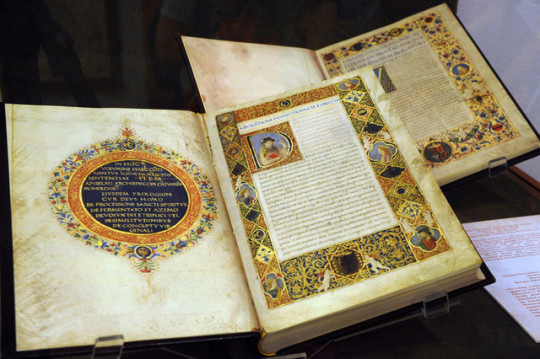

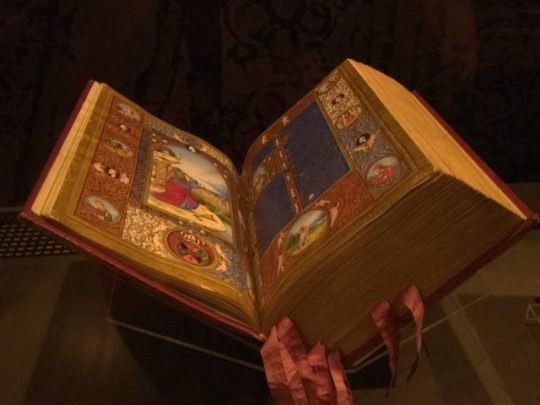

“I started to wonder about the history of Latin”

This post was written by Natasha Skorupski, a Department of Classics Intern in Archives & Special Collections for the Spring of 2022.

During my internship with the Hillman library and the Classics Department of the University of Pittsburgh I worked in the Archives & Special Collections, looking over Latin manuscripts. While looking through these I started to wonder about the history of Latin and how the spoken language fell yet the written word continued.

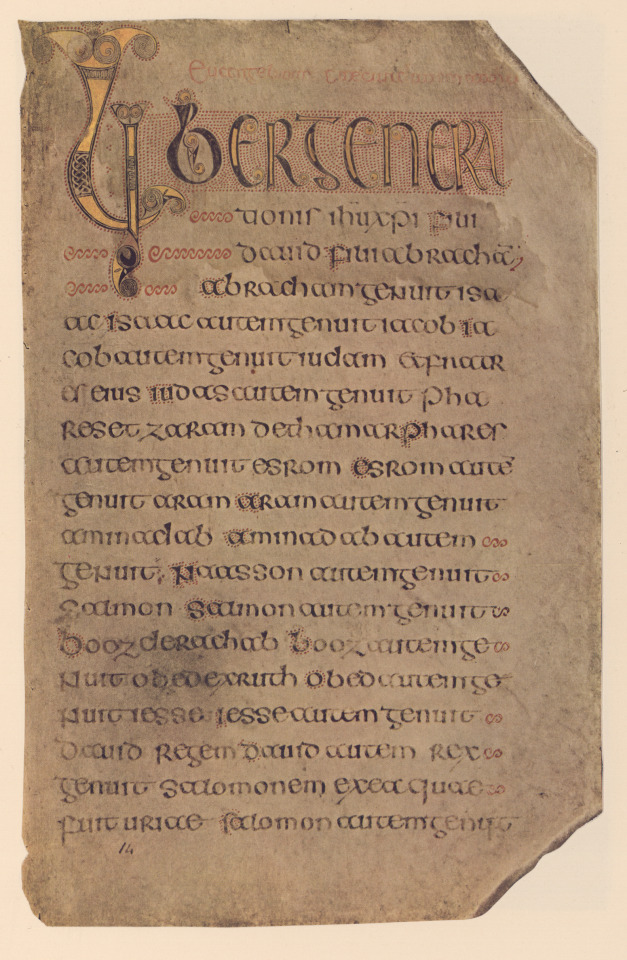

(Above) Evangeliorum quattuor Codex Durmachensis or The Book of Durrow, Olten: Urs Graf; sole distributors in the United States: P.C. Duschnes, New York by Arturus Aston Luce, 1960 facsimile. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Due to that I have found out the following information. Latin is thought to be derived from ancient Greek and Italic languages. Italy used to be made up of many different tribes that spoke many different languages, and these languages are called Italic languages today. The first evidence of Latin is an inscription on a cloak pin that was found from the sixth century BCE. On the pin it says, “Manius me fhefhaked Numasioi” which translates to “Manius made me [this] for Numerius”. The first literary records of Latin have been dated back to 250-100 BCE. The popularity of Latin increased with the rise of Roman political power. This spread was initially in Italy and then continued to most of Western Europe and parts of coastal Africa.

Latin has been classified into three groups. There is the written Latin, oratorical Latin (public speaking), and colloquial Latin (common speaking) (When Did Latin Die? and Why). The later Latin saw the greatest variation in its use and continuous divergence from it eventually evolved into Vulgar Latin. From Vulgar Latin we get the Romance Languages we know today, which include Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian.

The beginning of the end of the western Roman empire occurred in 395 CE. It fell for multiple reasons, some of them being military invasions, economic troubles, overreliance on enslaved labor, overexpansion and overspending of the military, political instability and corruption, among others (Andrews). With this fall came the decline of colloquial and Vulgar Latin.

There was a small period of resurrection for Latin under the “Roman Emperor” Charlemagne during 768-814AD. At this point in time, Latin was spoken, written, and read predominantly in religious settings as Italian, French and Spanish were rapidly evolving, allowing for a great decline of Latin (When Did Latin Die? and Why). During the mid-14th century, the Black Death Plague occurred. It killed millions of people, including numerous scholars and professors, creating a negative ripple effect on the entire education system (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

During the 15th and 16th centuries, there was another slight resurgence as people started to read Latin literature from classical authors. This was the time of the renaissance that spread mostly through Italy, France and later Britain. With the greater developments in science, Latin terminology was put into place as a way to regulate findings and encourage international research (When Did Latin Die? and Why).

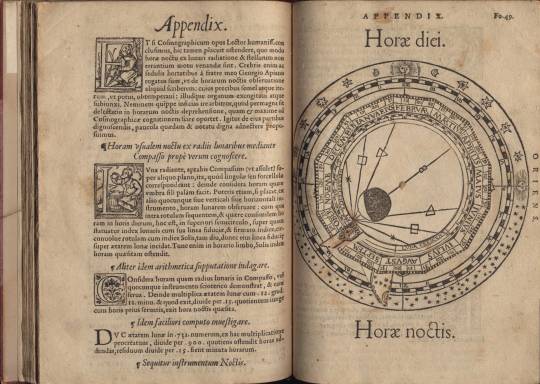

(Above) Cosmographia Petri Apiani. Antwerp: Veneunt Antuerpiæ Gregorio Bontio sub Scuto Basiliensi .. by P. & Gemma Apian, 1553. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Latin was seen as a status symbol at this point—you were seen as educated if you could read and write it. Though it was no longer spoken, it was used predominantly in literature and religion. Until the 19th century, Latin was a requirement for all that attended college. College was usually attended by white males of a privileged background (When Did Latin Die? and Why). However, this changed around the mid 1960s when the younger generation decided they also shared the right to higher education.

Today very few people can read Latin, even fewer can write it, and almost no one speaks it. However, it is one of the official languages of Vatican City and plays a vital role in Catholicism. Latin words are all over Catholic scripture and there are many recited terms that come from it (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

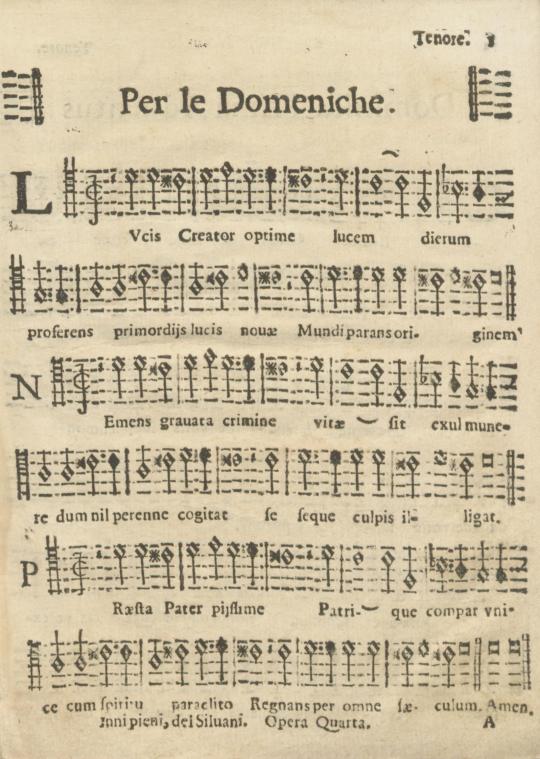

(Above) Inni sacri, per tutto l’anno : à quattro voci pieni, da cantarsi con l’organo e senza ... : opera quarta by G. A Silvani, 1705. Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

A fun fact, Pope Francis is the most influential Latin speaker today with about 40 million followers between his multiple accounts that vary in languages. One of these accounts posts solely in Latin! With his bio stating “Tuus adventus in paginam publicam Papae Francisci breviloquentis optatissimus est” which roughly translates to “Your arrival to the public page of the Tweeting Pope Francis is most welcome” (Pope Francis).

Latin words also dominate in modern science as names of medicine, drugs, diseases, body parts, and it is especially used in binomial nomenclature (the system for naming plants and animals). It is also greatly prevalent in the legal field. Amicus curiae, habeas corpus, and ex post facto being just a few of the more common ones. A fun fact is the jury comes from the Latin word “jurare” meaning “to swear” (Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?).

Latin is a dead language as it is no longer spoken. However it is not extinct, and still can be encountered more than most people in the world today would expect.

Works Cited

Andrews, Evan. “8 Reasons Why Rome Fell.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 14 Jan. 2014, https://www.history.com/news/8-reasons-why-rome-fell.

“Is Latin a Dead Language? Let's Explore Why?” The Language Doctors, 14 Mar. 2022, https://thelanguagedoctors.org/is-latin-a-dead-language/.

Pope Francis. “Pope Francis Tweeter Account.” Twitter, Twitter, 23 Apr. 2022, https://twitter.com/pontifex_ln?lang=en.

“When Did Latin Die? and Why?” Global Language Services, Global Language Services Ltd, 3 Feb. 2022, https://www.globallanguageservices.co.uk/did-latin-die/.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring the Boundless Realm of Books: Navigating the World of Literature and Learning

In a world saturated with digital media and technological distractions, the timeless allure of books continues to captivate and inspire readers of all ages. From ancient manuscripts to contemporary bestsellers, literature offers a gateway to knowledge, imagination, and personal growth. In this article, we embark on a journey through the boundless realm of books, exploring the transformative power of literature and the profound impact it has on individuals and societies.

The Magic of Reading:

Unlocking Doors to Imagination and Empathy: At its core, reading is an act of discovery and exploration, transporting readers to distant lands, introducing them to intriguing characters, and immersing them in captivating narratives. Whether delving into the pages of a classic novel, exploring the realms of fantasy and science fiction, or uncovering the depths of historical accounts, readers embark on a journey of imagination and empathy. Through literature, readers gain insights into diverse cultures, perspectives, and lived experiences, fostering empathy, understanding, and compassion for others.

The Power of Knowledge:

Empowering Minds and Enriching Lives: Books serve as repositories of knowledge, wisdom, and human achievement, offering readers access to a wealth of information and ideas. From academic textbooks to literary classics, books cover a vast array of subjects and disciplines, empowering readers to expand their intellectual horizons and deepen their understanding of the world. Whether seeking to master a new skill, explore a scientific theory, or ponder life's existential questions, books provide the tools and resources for personal and professional growth.

Lifelong Learning:

A Journey of Intellectual Exploration and Self-Discovery: The pursuit of knowledge through reading is a journey that transcends the boundaries of formal education. It is a lifelong endeavour marked by intellectual exploration and self-discovery. Lifelong learners recognize books as invaluable companions in their quest for personal growth and enrichment. With each page turned individuals embark on a voyage of discovery, encountering new ideas, perspectives, and worlds. Engagement with books cultivates a thirst for learning that extends far beyond the confines of classrooms and lecture halls. Lifelong learners approach reading with curiosity and an insatiable appetite for knowledge. They embrace books as portals to new realms of understanding, where they can delve into diverse topics, challenge their assumptions, and expand their intellectual horizons. Moreover, reading fosters critical thinking skills essential for navigating the complexities of the world. Lifelong learners analyze and evaluate the information presented in books, discerning between fact and fiction, truth and opinion. Through this process, they develop a nuanced understanding of the world and cultivate the ability to think critically and independently.

Ultimately, lifelong learning through reading is a journey of self-discovery. As individuals engage with books that resonate with their interests and passions, they uncover new facets of themselves and their place in the world. Reading provides moments of introspection and reflection, allowing individuals to explore their values, beliefs, and aspirations. In this way, books become not only sources of knowledge but also companions on the journey of self-discovery and personal growth.

The Role of Literature in Society:

Shaping Culture, Identity, and Progress: Literature occupies a central place in society, serving as a mirror that reflects the collective experiences, values, and aspirations of humanity. It plays a vital role in shaping culture, identity, and societal progress, capturing the essence of the human condition and preserving cultural heritage for future generations. Through literature, societies transmit shared values and traditions, fostering a sense of continuity and belonging. Classic works of literature serve as touchstones of cultural identity, providing insight into the beliefs, customs, and struggles of past generations. By revisiting these timeless texts, individuals gain a deeper appreciation for their cultural heritage and the values that bind communities together. Moreover, literature has the power to challenge prevailing norms and conventions, sparking conversations and inspiring social change. Authors use their creative voices to shine a light on injustice, inequality, and oppression, giving voice to marginalized perspectives and fostering empathy and understanding. Books become catalysts for empathy and social transformation, encouraging readers to confront difficult truths and envision a more just and equitable society.

In today's rapidly changing world, literature continues to play a vital role in shaping the cultural landscape and driving progress. Contemporary authors explore pressing issues facing society, from climate change and globalization to social justice and human rights. Their works provoke thought, stimulate dialogue, and inspire action, contributing to the ongoing evolution of society and the quest for a better future for all.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the boundless realm of books offers a gateway to knowledge, imagination, and personal growth. Through the magic of reading, individuals embark on journeys of discovery, empathy, and self-discovery, enriching their lives and expanding their horizons. By embracing literature as a lifelong pursuit, individuals and societies can harness the transformative power of books to navigate the complexities of the world, foster empathy and understanding, and inspire positive change for generations to come.

In the vibrant community of Uptown, schools play a pivotal role in fostering a love for literature and lifelong learning. With a commitment to excellence in education and a focus on holistic development, school in uptown provide students with the tools and resources needed to explore the world of literature and embark on their intellectual journeys. Through engaging curricula, passionate educators, and a supportive learning environment, these schools empower students to develop a deep appreciation for literature and its role in shaping culture, identity, and progress.

Moreover, school in uptown recognize the importance of instilling a lifelong love of reading in students from a young age. By integrating literature into various aspects of the curriculum and providing access to a diverse range of books and resources, these schools nurture a culture of literacy and intellectual curiosity. Through reading, students not only expand their knowledge and understanding of the world but also develop critical thinking skills, empathy, and a sense of empathy and understanding. As students graduate from school in uptown and embark on their journeys beyond the classroom, they carry with them a lifelong appreciation for literature and a commitment to intellectual exploration and self-discovery. Whether they pursue further education, enter the workforce, or become active members of their communities, they continue to draw inspiration from the world of books and literature, driving positive change and shaping the world around them for the better.

0 notes

Text

Cao Zhi Composing Poetry - China - second half of the 17th century

The link: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77025 - Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "The Printed Image in China: From the 8th to the 21st Centuries," May 5–July 29, 2012.

This print depicts Cao Zhi (192–232), a renowned poet with a tragic life, as a fragile youth standing on the foreground stairs. Resented for his literary talent by his powerful elder brother, the large figure sitting at the table, he was ordered to compose a poem within the time span of seven steps or suffer capital punishment. The monumental landscape screen transforms the finely detailed terrace into a stagelike space in which the human drama plays out.

Bequeathed to British Library by Sir Hans Sloane (1660 - 1753), part of Sloane manuscript 5293. Transferred from the Library to the British Museum in 1906.

About - Cao Zhi (192-232 AD) was a Chinese poet of the Han Dynasty.

He was the third son of the famous military commander Cao Cao, a prominent figure in Chinese history and one of the main characters in the epic novel "The Romance of the Three Kingdoms". Cao Zhi is known for his literary skills, especially in composing poems.

Cao Zhi is recognized for his poetic skill, and his poems often express intense emotions, philosophical reflections, and observations of nature. His works are considered an important part of classical Chinese literature.

One of his most famous works is “Ode to the Splendid Peacock”. This poem is an expression of his emotions and feelings regarding the decline of the Han dynasty, and he compares the beauty of the peacock to the lost splendor of the dynasty.

Cao Zhi is known for his participation in the famous "Dispute for the Throne" (Xuanjuan zhi zheng), a legendary event in which the brothers Cao Zhi and Cao Pi, Cao Cao's eldest son, fought for the right to inherit the throne of their father. Cao Zhi is said to have presented a poem called "The Splendid Peacock" as part of his argument.

After his defeat in the Throne Contest, Cao Zhi was not executed by his brother, but his later life is less documented. He continued to write poetry and, after his death, his literary work was preserved and appreciated throughout the centuries.

Cao Zhi is remembered as one of the great poets of ancient China, and his contributions to classical Chinese poetry are still studied and appreciated.

source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77025

#edisonmariotti @edisonblog

.br

Cao Zhi Compondo Poesia - China - segunda metade do século XVII

O link: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77025 - Devido a restrições de direitos, esta imagem não pode ser ampliada, visualizada em tela inteira ou baixada.

Nova Iorque. O Museu Metropolitano de Arte. "A imagem impressa na China: do século 8 ao 21", 5 de maio a 29 de julho de 2012.

Esta gravura retrata Cao Zhi (192–232), um poeta renomado com uma vida trágica, como um jovem frágil parado na escada em primeiro plano. Ressentido por seu talento literário por seu poderoso irmão mais velho, a grande figura sentada à mesa, ele foi condenado a compor um poema no intervalo de sete passos ou sofreria a pena capital. A monumental tela paisagística transforma o terraço minuciosamente detalhado em um espaço semelhante a um palco no qual o drama humano se desenrola.

Legado à Biblioteca Britânica por Sir Hans Sloane (1660 - 1753), parte do manuscrito Sloane 5293. Transferido da Biblioteca para o Museu Britânico em 1906.

Sobre - Cao Zhi (192-232 DC) foi um poeta chinês da Dinastia Han.

Ele era o terceiro filho do famoso comandante militar Cao Cao, figura proeminente na história chinesa e um dos personagens principais do romance épico "O Romance dos Três Reinos". Cao Zhi é conhecido por suas habilidades literárias, especialmente na composição de poemas.

Cao Zhi é reconhecido por sua habilidade poética, e seus poemas muitas vezes expressam emoções intensas, reflexões filosóficas e observações da natureza. Suas obras são consideradas uma parte importante da literatura clássica chinesa.

Uma de suas obras mais famosas é “Ode ao Esplêndido Pavão”. Este poema é uma expressão de suas emoções e sentimentos em relação ao declínio da dinastia Han, e ele compara a beleza do pavão ao esplendor perdido da dinastia.

Cao Zhi é conhecido por sua participação na famosa "Disputa pelo Trono" (Xuanjuan zhi zheng), evento lendário em que os irmãos Cao Zhi e Cao Pi, filho mais velho de Cao Cao, lutaram pelo direito de herdar o trono de seus pai. Diz-se que Cao Zhi apresentou um poema chamado "O Esplêndido Pavão" como parte de seu argumento.

Após sua derrota na Disputa do Trono, Cao Zhi não foi executado por seu irmão, mas sua vida posterior está menos documentada. Continuou a escrever poesia e, após a sua morte, a sua obra literária foi preservada e apreciada ao longo dos séculos.

Cao Zhi é lembrado como um dos grandes poetas da China antiga, e suas contribuições para a poesia clássica chinesa ainda são estudadas e apreciadas.

fonte: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/77025

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

10 Exquisite Destinations to Explore in Yokohama, Japan

When the allure of Japan beckons, travelers often find themselves enticed by the captivating blend of traditional charm and modern innovation. While Tokyo casts its shimmering skyscrapers and neon glow, a hidden gem awaits just a stone's throw away – Yokohama. Renowned for its maritime heritage, stunning landscapes, and cultural marvels, Yokohama offers an experience that seamlessly fuses history and modernity. Embark on a journey as we unveil the ten finest destinations that Yokohama has to offer.

Sankeien Garden: Where Time Stands Still

Step into a realm of serenity at Sankeien Garden, an oasis of tranquility that transports visitors to the elegance of the Edo period. Adorned with meticulously preserved historic buildings, lush flora, and meandering pathways, this haven of beauty radiates the essence of Japanese aesthetics.

Yamashita Park: A Waterfront Marvel

Behold the majestic panorama of Yokohama Bay at Yamashita Park, a verdant waterfront expanse that offers a respite from the urban bustle. As sea breezes gently embrace you, the iconic Hikawa Maru ship and the vibrant Marine Tower stand as silent witnesses to maritime history.

Landmark Tower: Ascending Beyond Borders

Elevate your experience at the Landmark Tower, an architectural triumph that pierces Yokohama's skyline. Gaze in wonder at the metropolis from the observation deck, or indulge in retail therapy at the sprawling shopping complex – all beneath one soaring roof.

Red Brick Warehouse: Fusion of Commerce and Culture

Immerse yourself in the allure of history at the Red Brick Warehouse, a duo of 20th-century edifices that now house a treasure trove of boutiques, dining establishments, and cultural events. This beguiling blend of past and present serves as a testament to Yokohama's transformation over the ages.

Yokohama Chinatown: A Gastronomic Odyssey

Embark on a culinary expedition through the vibrant Yokohama Chinatown, a lively district that tantalizes taste buds with an array of delectable Chinese cuisines. From intricate dim sum to fiery Szechuan delicacies, this culinary haven beckons gastronomes from near and far.

Hakkeijima Sea Paradise: Subaquatic Symphony

Dive into a world of aquatic marvels at Hakkeijima Sea Paradise, a marine-themed amusement park that merges entertainment and education. Discover the enigmatic dance of dolphins, the grace of jellyfish, and the vibrant colors of coral reefs – a celebration of oceanic wonders.

Mitsuike Park: Nature's Resplendence

Nature enthusiasts find solace at Mitsuike Park, a lush sanctuary boasting three mesmerizing ponds surrounded by diverse flora and fauna. Stroll along serene trails, listen to the symphony of birds, and witness the ever-changing canvas of seasonal hues.

Nogeyama Zoo: A Biodiverse Haven

Delve into the animal kingdom at Nogeyama Zoo, a compact yet comprehensive establishment that houses an assortment of creatures from around the globe. Encounter exotic species, including red pandas, capybaras, and rare avian wonders, fostering an appreciation for Earth's biodiversity.

Yokohama Museum of Art: A Cultural Voyage

Satisfy your cultural yearnings at the Yokohama Museum of Art, an architectural masterpiece that showcases an eclectic collection of Japanese and Western artistic treasures. Engage with avant-garde exhibitions, classic compositions, and thought-provoking installations.

Kanazawa Bunko: Bibliophile's Haven

For the literary connoisseur, Kanazawa Bunko stands as a testament to knowledge and heritage. This repository of ancient texts and manuscripts beckons intellectuals and curious minds alike, offering a glimpse into Japan's intellectual evolution.

In the heart of Yokohama's multifaceted tapestry, these 10 best places to visit in Yokohama Japan weave an enchanting narrative that showcases the city's rich history, cultural diversity, and contemporary allure. As you traverse these remarkable locales, each step whispers tales of a bygone era and whispers of a promising future, a harmonious symphony that defines Yokohama's unique essence.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Charon, the Lord of Death

According to Britannica:

In Etruscan mythology [Charon] was known as Charun and appeared as a death demon, armed with a hammer. Eventually he came to be regarded as the image of death and of the world below. As such he survives in Charos, or Charontas, the angel of death in modern Greek folklore.

This is further explored in Modern Greek folklore and ancient Greek religion: a study in survivals by John Cuthbert Lawson. According to Lawson:

There is no ancient deity whose name is so frequently on the lips of the modern peasant as that of Charon. About Charos the peasants will always, according to my experience, converse freely. Neither superstitious awe nor fear of ridicule imposes any restraint. They feel perhaps that the existence of Charos is one of the stern facts which men must face; and even the more educated classes retain sometimes, I think, an instinctive fear of making light of his name, lest he should assert his reality. For Charos is Death. He is not now, what classical literature would have him to be, merely the ferryman of the Styx. He is the god of death and of the lower world.

Lawson then goes on to describe how the importance of Charos has been elevated, for ‘Hades is no longer a person but a place, the realm over which Charos rules’. The author then goes into details surrounding Charos’ family.

On his physical depiction:

Sometimes he is depicted as an old man, tall and spare, white of hair and harsh of feature; but more often he is a lusty warrior, with locks of raven-black or gleaming gold [...] ‘his glance is as lightning and his face as fire, his shoulders are like twin mountains and his head like a tower’. His raiment is usually black as befits the lord of death, but anon it is depicted bright as his sunlit hair, for though he brings death he is a god and glorious.

On his functions, Lawson states:

His functions are clearly defined. He visits this upper world to carry off those whose allotted time has run, and guards them in the lower world as in a prison whose keys they vainly essay to steal and to escape therefrom. But the spirit in which he performs those duties varies according as he is conceived to be a free agent responsible to none or merely a minister of the supreme God. Which of these is the true conception is a question to which the common-folk as a whole have given no final answer; and the character of Charos consequently depends upon the view locally preferred.

The depiction of Charos has also been influenced by Christianity.

Those who regard him as simply the servant and messenger of God, find no difficulty in accommodating him to his Christian surroundings; for, as I have said, the peasant does not distinguish between the Christian and the pagan elements in his faith which together make his polytheism so luxuriant. We have already seen Charos' name with the prefix of ‘saint’; and though this Christian title is not often accorded him, yet his name appears commonly on tomb-stones in Christian churchyards. At Leonidi, on the east coast of the Peloponnese, I noted the couplet: 'Me too Charos pitied not but took, even me the fondly-cherished flower of my home.'

So too in popular story and song he is represented as working in concord with the Angels and Archangels, to whom sometimes falls the task of carrying children to his realm-. Indeed one of the archangels, Michael, who as we saw above has ousted Hermes, the escorter of souls, and assumed his functions, is charged with exactly the same duties as Charos in the conveyance of men's souls to the nether world, so that in popular parlance the phrases ‘he is wrestling with Charos’ and 'he is struggling with an angel' are both alike used of a man in his death-agony.

The author goes on to describe how the Christianized conception of Charon has made him appear kinder, as evidenced by many folk tales where it is shown that:

‘The duties imposed upon him by the will of God are sometimes repugnant to him, and he would willingly spare those whom he is sent to slay’

Some folk tales are then described. Also:

‘Sometimes then the doomed man will seek to tempt Charos with meat and drink, that he may grant a few hours' delay, but against offers of hospitality he is obdurate. Or again his victim refuses to yield to death 'without weakness or sickness' and challenges him to a trial of athletic skill, in wrestling or leaping, whereon each shall stake his own soul. And to this Charos sometimes gives consent, for he knows that he will.

In contrast...

The other and more pagan conception of Charos excludes all traits of kindness and mercy; and men do not stint the expression of their hatred of him. He is 'black,' 'bitter,' 'hateful’. He is the merciless potentate of the nether world, independent of the God of heaven, equally powerful in his own domain, but more terrible, more inexorable: for his work is death and his abode is Hades. Thence he issues forth at will, as a hunter to the chase. ‘Against the wounds that Charos deals herbs avail not, physicians give no cure, nor saints protection’ [...] But most commonly he is the warrior preeminent in all manner of prowess—archer, wrestler, horseman.

Charos is sometimes depicted to be collecting souls to adorn his kingdom. Examples being:

[...] he gathers children from the earth to be the flowers of it and young men to be its tall slim cypresses; more rarely he is a vintager, and tramples men in his vat that their blood may be his red wine, or again he carries a sickle and reaps a human harvest.

It became evident that ‘Charos of modern Greece would seem to have little in common with the Charon of ancient Greece’. Fauriel believes that ‘the usual tendencies of tradition have been reversed, in that it is the name that has survived, while the attributes have been changed’. However, Lawson disagrees. He states that:

I suspect that in ancient times the literary presentation of Charon was far more circumscribed than the popular, and that out of a profusion of imaginative portraitures as varied as those seen in the folk-songs of to-day one aspect of Charon became accepted among educated men as the correct and fashionable presentment. Hades was, in literature, the despot of the lower world, and for Charon no place could be found save that of ferryman. But this, I think, was only one out of the many guises in which the ancient Charon was figured by popular imagination; for at the present day the remnants of such a conception are small, in spite of the fact that there has remained a custom which should have kept it alive—the custom of putting a coin in the mouth of the dead.

In Alcestis, a play written by Euripides, Death seemed to have taken on the role of Charon, to the point where ‘the copyist of one of the extant manuscripts of the Alcestis was so impressed with the likeness of Death to Charon as he knew him, that he altered the name of the dramatis persona accordingly’. The conception of Charon as a Lord of Death occurs even further back than that though.

On the Etruscan Charun:

Hesychius states that the title [greek word] was shared by two gods, Charon and Uranus. Charon therefore, as son of Acmon and brother of Uranus, is earlier by two long generations of gods than Zeus himself, and belongs to the old Pelasgian order of deities. Was Charon then the god of death among the old Pelasgian population of Greece, before ever the name of Hades or Pluto had been invented or imported? Yes, if the corroboration from another Pelasgian source, the Etruscans, is to count for anything. On an Etruscan monument figures the god of death with the inscription 'Charun'; and the same person is frequently depicted on urns, sarcophagi, and vases [...] In appearance he is most often an old bearded man (though a more youthful type is also known) bearing an axe or mallet, and more rarely a sword as well, wherewith he pursues men and slays them. In effect the Etruscan Charun closely corresponds with the modern Greek Charos in functions as well as in name.

In classical times the primitive conception of Charon was in abeyance. Hades had assumed the reins of government in the nether world; and a literary legend, which confined Charon to the work of ferryman, had gained vogue and supplanted or rather temporarily suppressed the older conception. But this version, it appears, never gained complete mastery of the popular imagination, and to the common-folk of Greece from the Pelasgian era down to this day Charon has ever been more warrior than ferryman, and his equipment an axe or sword or bow rather than a pair of sculls. More is to be learnt of the real Charon of antiquity from modern folk-lore than from all the allusions of classical literature.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOMINANT THEMES AND STYLES LITERATURE

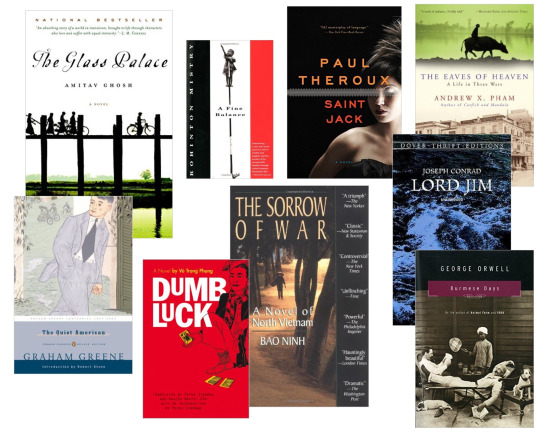

SOUTH EAST ASIA

This area, which embraces the region south of China and east of India, includes the modern nations of Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, The Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia. The earliest historical influence came from India around the beginnings of the Christian era. At a later period, Buddhism reached mainland Southeast Asia. Its influence was a major source of traditional literature in the Buddhist countries of Southeast Asia. Vietnam, under Chinese rule, was influenced by Chinese and Indian literature. Indonesia and Malaysia were influenced by Islam and its literature. All of the countries, except for Thailand, underwent a colonial experience and each of the countries reflects in its literature and in other aspects of its culture the influence of the colonizing power, including the language of that power. Education in the foreign language was to bring with it an introduction to a foreign literature and this, in turn, was to have considerable impact upon their modern forms of literary expression. One finds, then, all the well-known literary genres of Western literature, the novel, the short story, the play, and the essay. Poetry had been the most popular form of the traditional literature over the centuries but was rigid in form. However, through increased acquaintance with Western poetry, the poets of Southeast Asia broke the bonds of tradition and began to imitate various poetic types. A reading list of books is included.

EAST ASIA

Thinkers of the East is a collection of anecdotes and ‘parables in action’ illustrating the eminently practical and lucid approach of Eastern Dervish teachers.

Distilled from the teachings of more than one hundred sages in three continents, this material stresses the experimental rather than the theoretical – and it is that characteristic of Sufi study which provides its impact and vitality.

The emphasis of Thinkers of the East contrasts sharply with the Western concept of the East as a place of theory without practice, or thought without action. The book’s author, Idries Shah, says ‘Without direct experience of such teaching, or at least a direct recording of it, I cannot see how Eastern thought can ever be understood’.

SOUTH AND WEST ASIA

Chicana/o literature is justly acclaimed for the ways it voices opposition to the dominant Anglo culture, speaking for communities ignored by mainstream American media. Yet the world depicted in these texts is not solely inhabited by Anglos and Chicanos; as this groundbreaking new book shows, Asian characters are cast in peripheral but nonetheless pivotal roles.

Southwest Asia investigates why key Chicana/o writers, including Américo Paredes, Rolando Hinojosa, Oscar Acosta, Miguel Méndez, and Virginia Grise, from the 1950s to the present day, have persistently referenced Asian people and places in the course of articulating their political ideas. Jayson Gonzales Sae-Saue takes our conception of Chicana/o literature as a transnational movement in a new direction, showing that it is not only interested in North-South migrations within the Americas, but is also deeply engaged with East-West interactions across the Pacific. He also raises serious concerns about how these texts invariably marginalize their Asian characters, suggesting that darker legacies of imperialism and exclusion might lurk beneath their utopian visions of a Chicana/o nation.

Southwest Asia provides a fresh take on the Chicana/o literary canon, analyzing how these writers have depicted everything from interracial romances to the wars Americans fought in Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. As it examines novels, plays, poems, and short stories, the book makes a compelling case that Chicana/o writers have long been at the forefront of theorizing U.S.–Asian relations.

ANGLO -AMERICA AND EUROPE

ANGLO - AMERICA

The Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections has considerable holdings in Anglo-American literature from the 17th century onward, with notable strengths in the 18th century, Romanticism, and the Victorian and modern periods. Among the seventeenth-century holdings is a complete set of the Shakespeare folios, and works by John Milton and his contemporaries. Eighteenth-century highlights include near comprehensive printed collections of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, and substantial holdings on John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Addison, Sir Richard Steele, William Cowper, Fanny Burney, and others. Related materials include complete runs of periodicals, such as the Spectator and the Tatler.

EUROPE

The history of European literature and of each of its standard periods can be illuminated by comparative consideration of the different literary languages within Europe and of the relationship of European literature to world literature. The global history of literature from the ancient Near East to the present can be divided into five main, overlapping stages. European literature emerges from world literature before the birth of Europe—during antiquity, whose classical languages are the heirs to the complex heritage of the Old World. That legacy is later transmitted by Latin to the various vernaculars. The distinctiveness of this process lies in the gradual displacement of Latin by a system of intravernacular leadership dominated by the Romance languages. An additional unique feature is the global expansion of Western Europe’s languages and characteristic literary forms, especially the novel, beginning in the Renaissance.This expansion ultimately issues in the reintegration of European literature into world literature, in the creation of today’s global literary system. It is in these interrelated trajectories that the specificity of European literature is to be found. The ongoing relationship of European literature to other parts of the world emerges most clearly at the level not of theme or mimesis but of form. One conclusion is that literary history possesses a certain systematicity. Another is that language and literature are not only the products of major historical change but also its agents. Such claims, finally, depend on rejecting the opposition between the general and the specific, between synthetic and local knowledge.

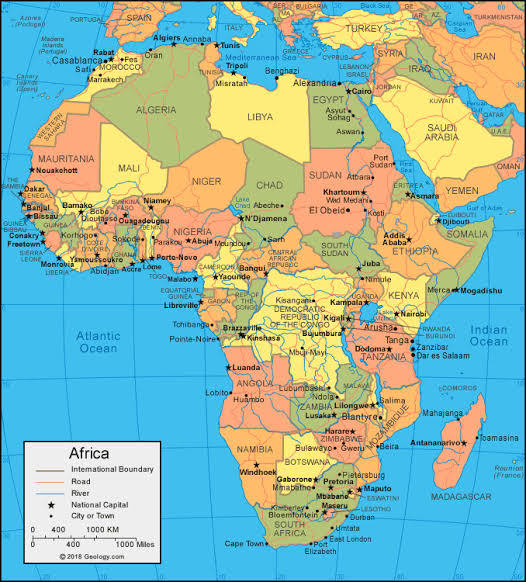

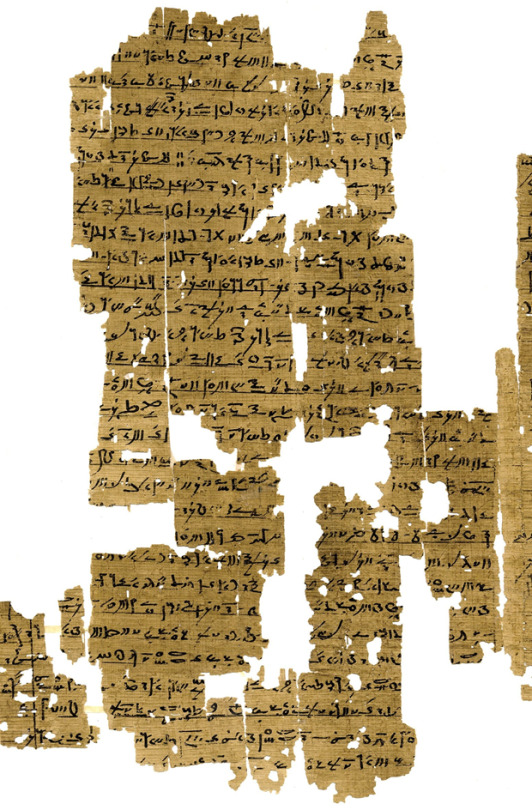

Africa

African literature has origins dating back thousands of years to Ancient Egypt and hieroglyphs, or writing which uses pictures to represent words. These Ancient Egyptian beginnings led to Arabic poetry, which spread during the Arab conquest of Egypt in the seventh century C.E. and through Western Africa in the ninth century C.E. These African and Arabic cultures continued to blend with the European culture and literature to form a unique literary form.

Africa experienced several hardships in its long history which left an impact on the themes of its literature. One hardship which led to many others is that of colonization. Colonization is when people leave their country and settle in another land, often one which is already inhabited. The problem with colonization is when the incoming people exploit the indigenous people and the resources of the inhabited land.

Colonization led to slavery. Millions of African people were enslaved and brought to Western countries around the world from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. This spreading of African people, largely against their will, is called the African Diaspora.

Sub-Saharan Africa developed a written literature during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This development came as a result of missionaries coming to the area. The missionaries came to Africa to build churches and language schools in order to translate religious texts. This led to Africans writing in both European and indigenous languages.

Though African literature's history is as long as it is rich, most of the popular works have come out since 1950, especially the noteworthy Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe. Looking beyond the most recent works is necessary to understand the complete development of this collection of literature

LATIN AMERICA

Latin American literature consists of the oral and written literature of Latin America in several languages, particularly in Spanish, Portuguese, and the indigenous language of America as well as literature of the United States written in the Spanish language. It rose to particular prominence globally during the second half of the 20th century, largely due to the international success of the style known as magical realism. As such, the region's literature is often associated solely with this style, with the 20th Century literary movement known as Latin American Boom, and with its most famous exponent, Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Latin American literature has a rich and complex tradition of literary production that dates back many centuries

Bocar, Mark Jason P.

Stem 11- St. Alypius

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

WORLD’S LITERATURE

Southeast Asia

From the point of view of its “classical” literatures, Southeast Asia can be divided into three major regions: (1) the Sanskrit region of Cambodia and Indonesia; (2) the region of Burma where Pali, a dialect related to Sanskrit, was used as a literary and religious language; and (3) the Chinese region of Vietnam.

There are no examples of Chinese literature written in Vietnam while it was under Chinese rule (111 BC–AD 939); there are only scattered examples of Sanskrit inscriptions written in Cambodia and Indonesia; yet most of the literary works produced at the court of Pagan in Burma (flourished c. 1049–1300) have survived because the texts were copied and recopied by monks and students. But in the 14th–15th centuries, vernacular literatures suddenly emerged in Burma and Java, and a “national” literature appeared in Vietnam. The reasons behind the development of each were the same: a feeling of nationalistic pride at the final defeat of Kublai Khan’s invasions, the desire of the people to find solace in literature amidst change and struggles for power, and the lack of wealth and patronage to channel artistic expression into building temples and tombs. In Vietnam and Java literary activity centred on the courts; but in Burma the first writers were the monks and, later, the laymen educated in their monasteries. In the new Burmese kingdom of Ava (flourished after 1364), the Shan kings were proud of their Burmese Buddhist culture, and they appointed the new writers into royal service, with the result that courtiers became writers also. The Tai kings of Laos and Siam led their courts in learning Pali from the Mon, whom they had conquered, and Sanskrit from the Khmer, whom they harassed; nevertheless, seized with national pride and influenced by the Burmese example, they developed their own vernacular literature. But Cambodia itself declined. Although the monks in the Theravada Buddhist (i.e., the Southeast Asian form of Buddhism) monasteries produced a few works in Pali, no vernacular literature emerged until finally Khmer-speaking people (those living in the area comprised approximately of modern Cambodia) were borrowing many words from the Tai.For its vernacular literatures, Southeast Asia can be divided into (1) Burma; (2) Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia; (3) Vietnam; (4) Malaysia and Indonesia; and (5) the Philippines (which produced a vernacular literature only in the 20th century, after the imposed Spanish and English languages and literatures had made their impact).

East Asia

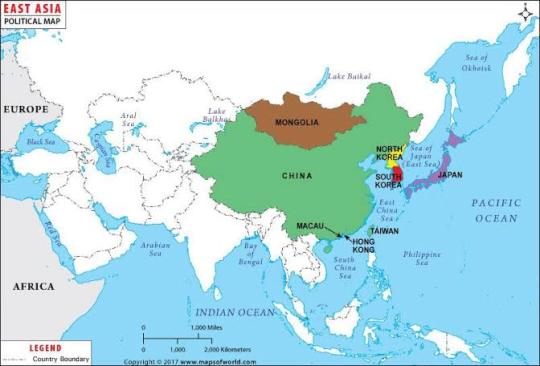

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms.The modern states of East Asia include China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. The East Asian states of China, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan are all unrecognized by at least one other East Asian state due to severe ongoing political tensions in the region, specifically the division of Korea and the political status of Taiwan. Hong Kong and Macau, two small coastal quasi-dependent territories located in the south of China, are officially highly autonomous but are under de jure Chinese sovereignty. North Asia borders East Asia’s north, Southeast Asia the south, South Asia the southwest and Central Asia the west. To the east is the Pacific Ocean and to the southeast is Micronesia (a Pacific Ocean island group, classified as part of Oceania). Countries such as Singapore and Vietnam are also considered a part of the East Asian cultural sphere due to its cultural, religious, and ethnic similarities. East Asia was one of the cradles of world civilisation, with China developing its first civilizations at about the same time as Egypt, Babylonia and India. China stood out as a leading civilization for thousands of years, building great cities and developing various technologies which were to be unmatched in the West until centuries later. The Han and Tang dynasties in particular are regarded as the golden ages of Chinese civilization, during which China was not only strong militarily, but also saw the arts and sciences flourish in Chinese society. It was also during these periods that China exported much of its culture to its neighbors, and till this day, one can notice Chinese influences in the traditional cultures of Vietnam, Korea and Japan. Korea and Japan had historically been under the Chinese cultural sphere of influence, adopting the Chinese script, and incorporating Chinese religion and philosophy into their traditional culture. Nevertheless, both cultures retain many distinctive elements which make them unique in their own right.

East Asian Writers

South and West Asia

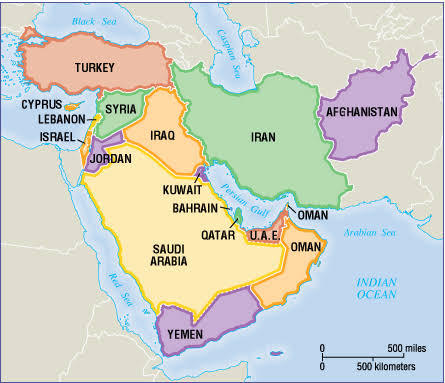

In the Hellenistic period literature and culture flourished in Western Asia. Traditional literary forms such as lists continued to be produced by the native population and were adapted by the new rulers. While there is little evidence for the creation of new narrative literature, which may in part be due to the fragmentary nature of our sources, existing epics, wisdom texts, and folktales were retold, rewritten, and transmitted. Greeks living in Western Asia created historiographical, ethnographical, and geographical works about their surroundings, inspiring in turn the Babylonian priest Berossus to write a reference work on Babylonia in Greek. Much as during the Persian Empire, political instability and changes in power led to a diverse and independent culture of writing. Continuity in all genres, writing systems, and languages remains the most important characteristic of Western Asian literature at least to the beginning of the Christian era.

Artists of western Asia are heirs to the first civilizations known to man, and their landscape is rich with examples of art, from the first human-form statues to Islamic and modern art. In the twentieth century, artists borrowed elements from their respective ancient patrimonies in an effort to create a national and regional cultural identity. Several artists’ groups formed between the 1930s and ’60s adopted European artistic modes of expression to produce works inspired by their heritage and by a rapidly disappearing landscape victim to urban migration and industrialization. This trend was most evident in Iraq, Jordan, and, to a limited extent, Israel and the Arabian Peninsula. Each country had its unique stages of development characterizing its artistic production, forging a synthesis of ancient western Asian cultures and Western styles. This unique synthesis is represented in the work of the Baghdad Modern Art Group in Iraq, and the Jewish Bezalel school of the early 1920s in Jerusalem. Jewish artists, traumatized by the Holocaust, rejected their European roots and turned to “Canaanite” myths and symbols in their quest for a national Hebrew identity. At the dawn of the twentieth century, life in many villages of western Asia had much in common with ancient life. Intrigued by this reflection of their heritage, artists depicted idyllic scenes of village life in areas such as the marshes of southern Iraq, a region ravaged in the 1980s when Saddam Hussein’s regime drained the wetlands and relocated the inhabitants.

Anglo-America and Europe

The Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections has considerable holdings in Anglo-American literature from the 17th century onward, with notable strengths in the 18th century, Romanticism, and the Victorian and modern periods. Among the seventeenth-century holdings is a complete set of the Shakespeare folios, and works by John Milton and his contemporaries. Eighteenth-century highlights include near comprehensive printed collections of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope, and substantial holdings on John Dryden, Samuel Johnson, Joseph Addison, Sir Richard Steele, William Cowper, Fanny Burney, and others. Related materials include complete runs of periodicals, such as the Spectator and the Tatler.

The history and literature of Continental Europe has been a specialty of the Newberry since its beginning, but like many other such broad fields, there are particular areas of great strength and others that are less well developed.In general, materials concerning Central and Western Europe from the fourteenth century to the end of the Napoleonic era are in scope for the library. Italy, France, and Germany are best represented. The Spanish and Portuguese collections tend to emphasize the imperial experiences of those countries but include major literary works, religious history, and pamphlets in abundance. There are significant but less extensive collections for Switzerland, Austria, the Low Countries, and some other areas. Literature and cultural history are strongest, including politics, theology, Romance and Germanic philology, education, and the classics. Philosophy, fine arts, architecture, law, and the natural sciences are more unevenly included, though the library owns many important individual works in these fields.In recent years, we have added only original sources in their original form, reference guides, bibliographies, textual editions, and a select number of monographs. The retrospective collections are also strong in monographs and scholarly periodicals. The Newberry does not systematically acquire new monographs or microform sets for European history and literature.

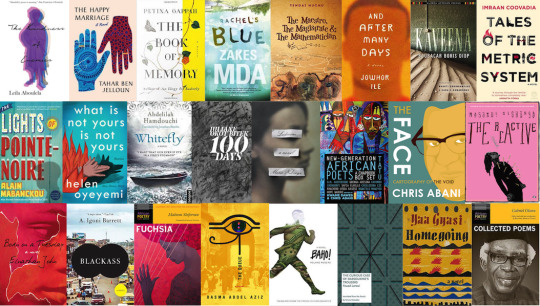

Africa

African literature, the body of traditional oral and written literatures in Afro-Asiatic and African languages together with works written by Africans in European languages. Traditional written literature, which is limited to a smaller geographic area than is oral literature, is most characteristic of those sub-Saharan cultures that have participated in the cultures of the Mediterranean. In particular, there are written literatures in both Hausa and Arabic, created by the scholars of what is now northern Nigeria, and the Somali people have produced a traditional written literature. There are also works written in Geʿez (Ethiopic) and Amharic, two of the languages of Ethiopia, which is the one part of Africa where Christianity has been practiced long enough to be considered traditional. Works written in European languages date primarily from the 20th century onward. The literature of South Africa in English and Afrikaans is also covered in a separate article, South African literature. See also African theatre. The relationship between oral and written traditions and in particular between oral and modern written literatures is one of great complexity and not a matter of simple evolution. Modern African literatures were born in the educational systems imposed by colonialism, with models drawn from Europe rather than existing African traditions. But the African oral traditions exerted their own influence on these literatures.

New books by African writers you should read

Latin America

Latin American literature consists of the oral and written literature of Latin America in several languages, particularly in Spanish, Portuguese, and the indigenous languages of the Americas as well as literature of the United States written in the Spanish language. It rose to particular prominence globally during the second half of the 20th century, largely due to the international success of the style known as magical realism. As such, the region's literature is often associated solely with this style, with the 20th Century literary movement known as Latin American Boom, and with its most famous exponent, Gabriel García Márquez. Latin American literature has a rich and complex tradition of literary production that dates back many centuries.

The Latino community has always excelled in its contributions to different academic fields, including the arts! When it comes to literature, there’s no exception. Some Latin American authors, whether they be poets, novelists or essayists, have influenced the world of writing with their creativity and originality.Since 1940, when Latin American literature has become an important reference in universal literature. Nowadays it continues to grow thanks to its various movements such as realism, antinovel and magical realism.Literature is an important part of Hispanic culture. Therefore, it is important to remember great figures of literature who, thanks to their creativity and originality in their writings, have achieved worldwide recognition and admiration. Listed below are some of the big names that have revolutionized Latin American literature:

by: Dominic Christian P. Cariaga

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE TRUE ORIGIN OF COUNT DRACULA

Dracula. The most famous vampire in history, created by the pen of Bram Stoker. Did he got inspired simply from Vlad Tepes, prince of Valachia, or are there any other figures who inspired him? The vampire figure has always been in the collective imagination and these creatures were born much earlier, and in some ancient civilizations there are already traces. In 1800, for example, there was a belief in Greece that all people with red hair could feed on blood.The cradle of vampires is Romania and it has always been believed that Dracula was modeled on the figure of Count Vlad, called "The Impaler", a member of the order of the Dragon, an order created to protect Christianity in Eastern Europe, in a time when the Turks was the most powerful empire in the world. he was ruthless and brutal and his reputation spread across Europe. Initially the novel was not titled "Dracula" but the original manuscript was simply titled "the undead" and the protagonist was called Count Vampyr.

This may mean that at first the writer had not directly connected him to Count Vlad. In 1998 Elizabeth Millard, a literary scholar, published an essay in which she supported the thesis that in reality Stoker did not have great knowledge on the figure of the notorious Romanian count, he certainly knew its history, but not so well. In 2010, Bob Carran, professor of Celtic history and mythology, publishes an interesting article that answers the question of who was inspired by Stoker for his vampire. Being the writer an Irishman, he may have been inspired by the legend of Abhartach, a fifth-century Irish chief known for his habits of feeding on the blood of his enemies and subjects.

In the 17th century, Geoffrey Keating translated a legend rooted in Celtic mythology. In his work "History of Ireland" he talks about a real historical figure: Abertach. He was a warlord, governor of a small kingdom. He was much feared by the local population as he was believed to have magical powers. Fear led the population to seek help from a chief of a nearby kingdom, Katayn, and that if he were able to kill him, the rival's kingdom would end up in his hands.

He succeeded, killed him and buried him in an upright position as was the custom. But during the night Abertach emerged from his grave, recovered his strength by feeding on the blood of one of his subjects and began the hunt for his assassin. Katayn killed him a second time, but Abertach continued to rise from his grave. Katayn asked for help from a shaman who told him that his rival was an "undead" and that to defeat him he had to bury him upside down and stick a wooden stake in his heart. Following the advice, Abertach was finally defeated.

The Celtic word "dreach - fhuola" means "corrupt blood" and it is believed that it is from this word that Stoker called Dracula its protagonist. When Bram Stoker was researching one of his biggest influences was a woman born in a healthy family in the Lanarkshire town of Airdrie, her name was Emily Gerard and she wrote books about Transylvanian folklore titled “ The land beyond the forest”. Those books introduced to Stoker the concept of the “nosferatu”, a vampire creature. She wrote the books after spending 2 years in Romania with her husband, who was there as an officer in the Austro – Hungarian army.

I agree that for sure Stoker has been inspired by several different sources since Ireland mythology is vast and has many tales and legends. I have always been really interested in the figure of the vampire. it’s something ancient, almost “ primordial”, and in my opinion, it’s the most famous horror creature in literature. The classic and the modern one. I read Dracula for the first time when I was 11 years old and it has been a life changing book. It was not just an horror novel but much more. It marked the beginning of my passion / obsession for Gothic and Horror Literature and it’s something that accompanies me to these days. I never get tired to study the book and the new literary discoveries about it.

Photo: a photo portrait of Bram Stoker.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

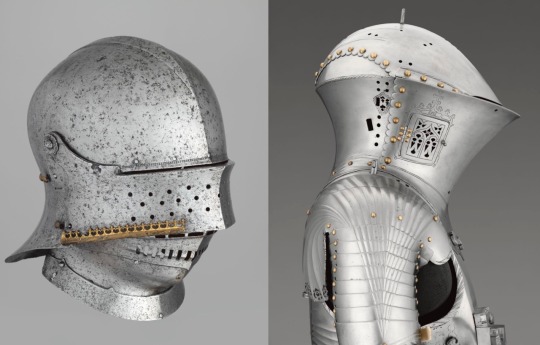

KAISER MAXIMILIAN I

THE TWELFTH OF JANUARY 2019 was the 500th snniversary of the death of the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilan I (1457/1519).

The son of Emperor Frederick III assumed the imperial throne in 1493, but never went to Rome to be crowned. He was married three times, all advantageously. His first wife, Mary of Burgundy, was the richest woman in Europe and her massive dowry included the manuscript collection of the Dukes of Burgundy. Maximilian never met his second wife, Anne de Bretagne, who was forced to repudiate him and marry his archenemy, Charles VIII (upon the death of Charles, Anne married Louis XII, making her the only woman to be Queen of France twice). Maximilian abandoned his third wife, the wealthy, yet vapid, Bianca Maria Sforza, through whom gained suzerainty over Milan. Upon her death, he renounced women as part of a program of religious austerity.

Throughout his reign, and despite the wealth of his wives, Maximilian lacked the financial means to fund his many wars and projects and resorted to loans from German bankers. Some of the loans were put to questionable use: one million gulden were borrowed from the Fugger bank for the purposes of bribing the German electors to secure the election of Maximilian’s grandson, Charles V, as the next emperor. At the time of his death, Maximilian owed German banks over 6 million gulden—the quivalent of 10 years of the annual revenues from the Hapsburg lands. These debts were not paid off until the end of the 16th century.

The notable areas of Maximilian’s artistic patronage were portraits, prints, and armor. Portraiture occupied a central role in the dissemination of official ideology in the early modern period. Maximilian’s court artist, Bernhard Strigel turned out dozens of portraits illustrating the various virtues and capacities of the emperor. Imperial patronage of Albrecht Dürer, Joos van Cleve and Giovanni Antonio di Predis reflected the artistic diversity of the far-flung Hapsburg dominions.

Throughout his early life, Maximilian closely identified with the culture of chivalry. This interest in knights in shining armor and tournements was probably greatly enriched by his 8-year sojourn in the Burgundian lands. Lucas Cranach the Elder portrayed Maximilian in the guise of Saint George, his hero as a youth, displaying his bravery and plumage, while rescuing the lady in distress. The emperor was also the author of Weißkunig (1506) and Theuerdank (1517), thinly-disguised autobiographical accounts of his early reign cast as chivalric romances. The printed books were illustrated with woodcuts by Hand Burgkmair and set in a stylish, blackletter typeface designed by Vinzenz Rockner. Maximilian circulated copies of these works to his allies and vassals as a means of controlling his public image.

The love of chivalry is most evident in the collection of suits of armor commissioned by Maximilian. Working closely with their patron throughout the design process, master armoirers turned out spectcular steel visions of knightly grace and strength. The style of armor favored by the emperor featured fluting, pleating, bird’s beak visors and other sculptural manipulations, with allusions to contemporary clothing. This stylem, which differed from the superficial engraving and gilding of the Milanese style, is known today as Maximilian armour.

As the nominal descendant of the western Roman emperors, Maximilian alluded to the ancient Romans in his arts patronage. The assertions of continuity with classical antiquity were often made using the most modern technologies available at the time. Die Triumphzug, an ambitious project depicting Maximilian celebrating a Roman triumph, was executed entirely in the new medium of print.

The artists including Hans Burgkmair, Dürer, and Dürer’s student, Albrecht Altdorfer, provided drawings of the various components of a Roman triumph, including a triumphal arch and chariot, which were transferred to woodblocks. The triumphal arch, by Dürer and his students, is composed of 195 woodcut images printed on 36 large sheets of paper. The triumpal procession, largely by Burgkmair, commemorates the expansion of Hapsburg territory under Maximilian. In all, 136 blocks were required to create an image 177 m long. Maximilian intended to send printed sets of these images to German princes, electors, and bishops, who were expcted to assemble and display the vast, composite images in palaces and public buildings. At the time of his death, the Triumphzug was unfinished. A truncated version was published in 1526. Several early copies were hand-colored.

Maximilian’s use of the new print technologies for his literary and artistic projects has often been described as a low budget choice forced by necessity on a financially-strapped ruler. While it is certain that Maximilian would have chosen more expensive and prestigious materials for some of his commissions (as evidenced by the Golden Roof in Innsbück), his choice of woodcut prints had an ideological value. By promoting a medium in which German artists excelled, he demonstrated the advanced cultural achievements of his Empire and the flourishing of the arts guided by his innovative patronage.

#holy roman empire#maximilian i#woodcut#albrecht dürer#german art - 16thc.#mary of burgundy#anne de bretagne#charles viii#charles v#hapsburg

26 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Dickinson’s “items” have been successively and carefully framed to give the impression that something, or someone, is missing. While the recovery of Dickinson’s manuscripts may be supposed to have depended on the death of the subject, on the person who had, by accident or design, composed the scene, the repeated belated “discovery” that her work is yet in need of sorting (and of reading) may also depend upon the absence of the objects that composed it. These objects themselves mark not only the absence of the person who touched them but the presence of what touched that person: of the stationer that made the paper, of the manufacturer and printer and corporation that issued guarantees and advertisements and of the money that changed hands, of the butcher who wrapped the parcel, of the manuals and primers and copybooks that composed individual literacy, of the expanding postal service, of the modern railroad, of modern journalism, of the nineteenth-century taste for continental literary imports. All of these things are the sorts of things left out of a book, since the stories to be told about them open out away from [a] narrative of individual creation or individual reception … This is to say that what is so often said of the grammatical and rhetorical structure of Dickinson’s poems—that, as critics have variously put it, the poetry is “sceneless,” is “a set of riddles” revolving around an “omitted center,” is a poetry of “revoked . . . referentiality”—can more aptly be said of the representation of the poems as such. Once gathered as the previously ungathered, reclaimed as the abandoned, given the recognition they so long awaited, the poems in bound volumes appear both redeemed and revoked from their scenes or referents, from the history that the book, as book, omits.

…