#Diana Arterian

Text

I the same mass

more down and away

I pluck & wilt & vanish

I stained the hollow floor

— Diana Arterian, from “Introduction,” published in Birdfeast

134 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Like so many writers, the activities that once challenged and nourished me have been disrupted by the flood of chaotic daily news....What does revitalize me most now is the solitude of a natural space, a garden or a trail....Moving in nature invites me to recognize my smallness in earth’s vast purpose—while simultaneously experiencing wonder in a vine’s reach and twist and leafing. In short: I gain perspective, and tap into feeling. Words often move into the space made there.

Diana Arterian, in this week’s Writers Recommend; read the rest at pw.org!

#Diana Arterian#Writers Recommend#Poets & Writers#on writing#true for writing#writing tips#writing advice#writing habits#writer's life#writing routine#writer's block#lit#literature#quote#quotes

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Ray Bradbury Challenge: Day 588

The Ray Bradbury Challenge: Day 588

Short story: The Explosives Expert by John Lutz, from Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, from December 2011. Recommended.

Poem: Agrippina the Younger, Age Thirteen by Diana Arterian, listened to on the PoetryNow podcast, from April 2018. Highly Recommended.

Essay: Maps of Meaning 6: The Neuropsychology of Symbolic Representation by Jordan B. Peterson. Highly Recommended.

What is the Ray…

View On WordPress

#books#challenge#Diana Arterian#essay#John Lutz#Jordan B. Peterson#poetry#Ray Bradbury Challenge#reading

0 notes

Text

With Deer (An Essay)

We are lying on the couch together, your arms around me. The sound of our animals running around, reminding me of the day we explored an abandoned bath house. As we ascended the stairs, we heard a feral skittering above. We gave quiet retreat.

Another part of the property, by the baths, the remnants of a deer. All that remained were the legs, tipped with those black hooves, the rusty fur in patches on the ground.

Now I see the deer bounding into a small break in the wooden wall, attempting for days to get out until succumbing to exhaustion.

Lying down.

Then starvation, the inner hollowing.

Blinking, breathing slower. Dying.

What are you thinking about? you ask.

Sergeant Calvin Gibbs is found guilty of killing Afghani citizens, pruning fingers from his victims. He also pulled a tooth from one man, saying in court that he had ‘disassociated’ the bodies from being human, that taking the fingers and tooth was like removing antlers from a deer…But he insisted that the people he took them from had posed genuine threats to him and his unit.

You and I go to a bar and strike up conversation with two aging Angelinos—a Filipino-American and Mexican-American, old friends. Somehow, we get to terrorism. One explains Israeli airlines don’t let Muslims on planes. How if you needed to get somewhere and the Israeli airline didn’t let you on, you were shit out of luck. We say this isn’t fair.

Do you think the terrorists are playing fair?

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t, I say. He tells me I’m naïve, his hand on my shoulder.

You little one, you little bunny, he says. You little fawn.

I buy budding sprigs for my room, the largest branch like a fine antler, nearly four feet in length. The tips brush the ceiling, purple petals beginning to work from grey buds.

The tips tremble almost continually.

Diana Arterian

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

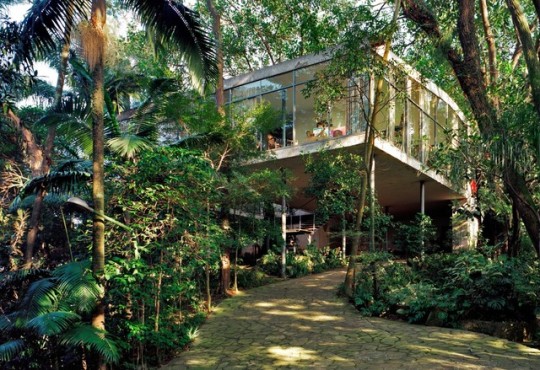

Lina Bo Bardi, Bardi House (Casa de vidro), São Paulo, Brazil, 1949-1952, view from the northeast, photograph by Nelson Kon, 2002, Courtesy Nelson Kon. Image courtesy of Palm Springs Art Museum.

Thursday, October 19

LATIN AMERICAN ARTISTS IN THE MARCIANO COLLECTION, Marciano Art Foundation (Mid-Wilshire), 11am–5pm.

CULTURE FIX: HEATHER SHIREY ON THE BAIANA AND AFRO-BRAZILIAN IDENTITY, Fowler Museum (Westwood), 12–1pm.

Paul Brach Visiting Artist Lecture Series: Dorit Cypis, CalArts (Valencia), 12pm.

Psychedelic Cello by Justin Lepard, CalArts (Valencia), 12–1pm.

Chicana Photographers L.A., WEINGART GALLERY (Westchester), 5–8pm.

Albert Frey and Lina Bo Bardi: Environments for Life, Palm Springs Art Museum (Palm Springs), 5pm.

Architects for Animals® Giving Shelter, HermanMiller Showroom (Culver City), 5:30–9:30pm. $50–500.

Artist and scholar walkthroughs: Micol Hebron, Hammer Museum (Westwood), 6pm.

THE CUT | EL CORTE: A Fitness Class & Papel Picado Workshop, Craft and Folk Art Museum (Miracle Mile), 6–8pm. $20.

Alan Gutierrez: INTRO, Artist Curated Projects (Echo Park), 6–8pm.

San Pedro House History Workshop, Angels Gate Cultural Center (San Pedro), 6pm.

Climate Change and the Shaping of Asia, Getty Center (Brentwood), 7pm.

Bayard & Me Documentary Screening followed by a shorts program and Q&A, Vista Theater (Los Feliz), 7pm.

Adriana Varejao: Transbarrocco, Lloyd Wright Sowden House (Los Feliz), 7–9pm. Through October 21. RSVP here.

Dis Miss: Performing Gender, USC (Downtown), 7pm.

Film Night: Seven Cities of Gold, Laguna Art Museum (Laguna Beach), 7pm.

Rodrigo Valenzuela Lecture, Hammer Museum (Westwood), 7:30pm.

Film: Free Screening | 11/8/16, LACMA (Miracle Mile), 7:30pm.

Film Night: Seven Cities of Gold, Laguna Art Museum (Laguna Beach), 7:30pm.

Oscar David Alvarez, PØST (Downtown), 8pm.

Modernism week fall preview weekend, various locations (Palm Springs), various times. Through October 22.

Friday, October 20

Symposium – Art from Guatemala 1960 - Present, Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (Santa Barbara), 10am. $15.

International Orchid Show & Sale, The Huntington (San Marino), 10am–5pm. Through October 22.

School of Music Visiting Artist Series: Pascale Criton with Silvia Tarozzi and Deborah Walker, CalArts (Valencia), 10am–12pm.

STORY TIME AT THE FOWLER, Fowler Museum (Westwood), 11:30am–12:30pm.

Charles Phoenix: Addicted to Americana Live Comedy Slide Show Performance, Palm Springs Art Museum (Palm Springs), 3–5pm. $40.

Christopher Michlig and Jan Tumlir in Conversation, 1301PE (Miracle Mile), 5pm.

Inès Longevial: Sous Le Soleil, HVW8 Gallery (Fairfax), 6–9pm.

Stepping into the Radiant Future, LAST Projects (Lincoln Heights), 7–11pm.

Feathers of Fire: A Persian Epic, Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts (Beverly Hills), 7:30pm. $45–125. Through October 29.

Latin Rhythms: Cha Cha Cha Dance Class, Museum of Latin American Art (Long Beach), 7–9pm.

Mark Edward Rhodes & Jeanete Clough, Beyond Baroque (Venice), 8pm.

Book Launch: PLAYING MONSTER :: SEICHE by Diana Arterian, Human Resources (Chinatown), 8pm.

Princess Diana in Auschwitz, CalArts (Valencia), 8pm. Through October 24.

WHAP! Lecture Series: 'in/ibid./form', West Hollywood Public Library (West Hollywood), 7:30pm.

PST: LA/LA Santa Barbara Weekend, various locations (Santa Barbara), various times. Through October 22.

Saturday, October 21

UCLA ART HISTORY GRADUATE SYMPOSIUM, Fowler Museum (Westwood), 9am–5pm.

12th annual Los Angeles Archives Bazaar, USC (Downtown), 9am–5pm.

An Ephemeral History of High Desert Test Sites: 2002-2015, High Desert Test Sites (Joshua Tree), 9am. Continues October 22.

Family Festival, Getty Center (Brentwood), 10am–6pm.

The Beverly Hills Art Show, Beverly Gardens Park (Beverly Hills), 10am–5pm. Also October 22.

Frederick Hammersley: To Paint without Thinking, The Huntington (San Marino), 10am–5pm.

Modern Masters from Latin America: The Pérez Simón Collection, The San Diego Museum of Art (San Diego), 10am–5pm.

A Generative Workshop: Gathering Imagery from the Internal Well with Holaday Mason, Beyond Baroque (Venice), 11am–3pm.

Fall Yoga Series, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 10:30am–11:30am. $12–15.

Fall 2017 Brewery Artwalk, the Brewery (Downtown), 11am–6pm. Continues October 22.

Print making with recycled materials, Side Street Projects (Pasadena), 11am–1pm.

Strike a Pose: Improv Comedy in the Portrait Gallery, The Huntington (San Marino), 12:30, 1:30, and 2:30pm.

Festival For All Skid Row Artists, Gladys Park (Downtown), 1–5pm. Continues October 22.

The 3rd Space: Political Action Workshop, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 1–4pm. $5–10.

EXHIBITION TALK & TOUR: Eva J. Friedberg, Daria Halprin & Edward Cella, Edward Cella Art+Architecture (Culver City), 1:30pm.

ARTIST TALK: KAJAHL: Unearthed Entities, Richard Heller Gallery (Santa Monica), 3–5pm.

Alison Blickle: Supermoon, Five Car Garage (Santa Monica), 3–5pm. RSVP to [email protected].

The 2017 Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation, REDCAT (Downtown), 3, 5, and 8pm.

Jeffrey Schultz & F. Douglas Brown, Beyond Baroque Foundation (Venice), 4pm.

Jaime Guerrero & Bradley Hankey Artist Talks, Skidmore Contemporary Art (Santa Monica), 4pm.

Film: Mapa Teatro’s Project 24, LACMA (Miracle Mile), 4pm.

Los Angeles Filmforum presents Three screenings with Argentinian filmmaker Claudio Caldini, USC (Downtown), 4pm.

When Ice Burns: New works by Diane Best, Porch Gallery (Ojai), 5–7pm; artist talk, 4pm.

Astrid Preston: Upside Down World and Rose-Lynn Fisher: The Topography of Tears, Craig Krull Gallery (Santa Monica), 5–7pm.

VICTOR ESTRADA (IN CONJUNCTION WITH PACIFIC STANDARD TIME), MARTEL SPACE: RICHARD HAWKINS, MARTEL WINDOW PROJECT: MALISA HUMPHREY, Richard Telles Fine Art (Fairfax), 5–8pm.

ARCHAEOLOGY REINVENTED, R.B. Stevenson Gallery (La Jolla), 5–8pm.

The Xenomorph's Egg, Patrick Painter Gallery (Santa Monica), 6–8pm.

The Unconfirmed Makeshift Museum, Klowden Mann (Culver City), 6–8pm.

Personal Vacation and 3 Solo Shows, Los Angeles Art Association/Gallery 825 (West Hollywood), 6–9pm.

FRAY: Art and Textile Politics, Craft and Folk Art Museum (Miracle Mile), 6–8pm. $20.

Mike Kelley: Kandors, Hauser & Wirth (Downtown), 6–9pm.

Homeward Bound, Nicodim Gallery (Downtown), 6–8pm.

Kelly McLane: PECKERWOODS and Augusta Wood: PARTING AND RETURNING, DENK Gallery (Downtown), 6–8pm.

In Order of Appearance and Luke Butler: MMXVII, Charlie James Gallery (Chinatown), 6–9pm.

Jennifer Precious Finch (L7) & KRK Dominguez, Red Pipe Gallery (Chinatown), 6–10pm.

Open Studios, Keystone Art Space (Lincoln Heights), 6–10pm.

The Very Best of OMA Artist Alliance 2017, L Street Fine Art (San Diego), 6–8pm.

Dany Naierman: PORT CAPA, Angels Gate Cultural Center (San Pedro), 6pm.

Arco Iris, Giant Robot Store + GR2 Gallery (Sawtelle), 6:30–10pm.

South of the Border, The Loft at Liz’s (Mid-City), 7–10pm.

Killer Bees at MAR-A-LAGO, Tieken Gallery LA (Chinatown), 7–10pm.

Art Moura, The Good Luck Gallery (Chinatown), 7–10pm.

Rafael Cardenas - From The Holocene, Exhale Unlimited (Chinatown), 7–10pm.

Story Tellers: a DIA de los MUERTOS, Museum of Latin American Art (Long Beach), 7–11pm.

Yare: One More Dance by Cristobal Valecillos, Timothy Yarger Fine Art (Downtown), 7:30–10pm.

Laurel Atwell and Jessica Cook: Debris, Pieter (Lincoln Heights), 8–10pm. $15.

Sunday, October 22

Adrián Villar Rojas: The Theater of Disappearance, The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA (Downtown), 11am–5pm.

Healthy Urban Living Team Building, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 11am–1pm.

Origin Stories Workshop with Nicole Rademacher & Jerri Allyn, Self-Help Graphics & Art (Downtown), 12–3pm.

2017 A.G.Geiger Art Book Fair, 502 Chung King Plaza (Chinatown), 1–7pm.

Community Celebration, Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara (Santa Barbara), 1–4pm.

Talk: Conversation & Book Signing: Michael Govan and Walter Isaacson on Leonardo da Vinci, Lacma (Miracle Mile), 2pm.

Nature Deficit Disorder Workshop, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 2–6pm. $60–75.

BORDERS and NEIGHBORS screening and panel discussion, Los Angeles Central Library (Downtown), 2pm.

Lecture: Jens Hoffman, Santa Barbara Museum of Art (Santa Barbara), 2:30–4pm.

PUBLIC WALKING TOURS: Lawrence Halprin: Reconnecting the Heart of Los Angeles, various locations, 2:30pm. Also November 5 and 19 and December 17.

Constellations and Connections: A Panel Discussion on Axis Mundo, West Hollywood Council Chambers (West Hollywood), 3pm.

Neighborhood Walk and Draw, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 4–5:30pm.

Akio Suzuki and Aki Onda, Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook (Culver City), 4pm.

For Us By Us, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 6:30–10:30pm. $5 donation.

GALLERY TALK | Peter Frank with Robert Standish, KM Fine Arts (West Hollywood), 5–7pm.

FALL IN LOVE WITH FREY, Palm Springs Art Museum (Palm Springs), 6–9pm. $125–175.

Claudio Caldini, Echo Park Film Center (Echo Park), 7:30pm. $5.

Monday, October 23

Yare: One More Dance by Cristobal Valecillos, Timothy Yarger Fine Art (Beverly Hills), 10am–6pm.

Kellie Jones, Art + Practice (Leimert Park), 7pm.

Fantasmas Cromáticos: 8mm Visions of Claudio Caldini, REDCAT (Downtown), 8:30pm. $6–12.

Tuesday, October 24

The Bombay Sapphire Artisan Series, 101/EXHIBIT (West Hollywood), 10am–6pm.

Movement and Landscape: Celebrating the Halprin Legacy, Central Library (Downtown), 12pm.

PUBLIC DANCE PERFORMANCE: Heidi Duckler Dance Theatre, Central Library (Downtown), 12pm.

Film: The Invisible Man, LACMA (Miracle Mile), 1pm.

The Music of Latin America in Los Angeles, The Artform Studio (Highland Park), 6:30–9pm.

FLAVORS OF MEXICO, Skirball Cultural Center (Brentwood), 7:30–9pm. Also November 14 and December 12.

No Mas Bebes, Hammer Museum (Westwood), 7:30pm.

El Automóvil Gris, Skirball Cultural Center (Brentwood), 8pm.

Sounding Limits: The Music of Pascale Criton, REDCAT (Downtown), 8:30pm. $12–20.

Wednesday, October 25

FOWLER OUT LOUD: SAMANTHA BLAKE GOODMAN, Fowler Museum (Westwood), 6–7pm.

LAND's 2017 Gala, Carondelet House (MacArthur Park), 6–11pm.

Screening and Conversation with Filmmakers Ben Caldwell, Barbara McCullough, and Curator Erin Christovale, Fowler Museum (Westwood), 7–9pm.

We Wanted a Revolution, Black Radical Women 1965–85 curatorial walkthrough, Lezley Saar: Salon des Refusés, California African American Museum (Downtown), 7–9pm.

Making Athens Great (Again?): Modern Lessons from the Age of Pericles, Getty Villa (Pacific Palisades), 7:30pm.

Kellie Jones: South of Pico, Hammer Museum (Westwood), 7:30pm.

Soundbath With Chakra Crystal Singing Bowls Series, Women’s Center for Creative Work (Frogtown), 7:30–8:30pm. $16–20.

Performance: Live/Work, Honor Fraser Gallery (Culver City).

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Friday, Oct 6th, 2017 @ 7PM, Minneapolis College of Art and Design

Join Next Poetix as we welcome Diana Arterian, Gabrielle Civil, Sawako Nakayasu, and Chaun Webster to the MCAD mic. RSVP HERE.

ALL ARE WELCOME. Bring your friends. LOCATION: MCAD Main Auditorium (first floor) NEXT POETIX: What's next in poetry and hybrid writing and performance beyond the neoliberal apocalypse. IMAGE CREDIT: Diane Guzman.

#poetry#poems#poem#creativewriting#minnesota#minneapolis#twincities#art#performance#hybridwriting#experimentalwriting#mcad

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

PW Poetry Annex October 2017

It’s October, which means that holiday lists are coming out because some organizations think they’re supposed to. Here’s a link to PW’s holiday gift guide; I’ve screencapped the poetry list since it’s all behind a paywall.

Eco-Dementia. Janet Kauffman (Wayne State)

Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric. Henry Wei Leung (Omnidawn)

Good Bones: Poems. Maggie Smith (Tupelo)

The Interrogation. Michael Bazzett (Milkweed)

Landscape with Sex and Violence. Lynn Melnick (YesYes)

Obscenity for the Advancement of Poetry. Kathryn L. Pringle (Omnidawn)

Playing Monster :: Seiche. Diana Arterian (1913)

Subwoofer. Wesley Rothman (New Issues)

Testify. Simone John (Octopus)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos

By DIANA ARTERIAN

The writing in Reines’s new collection is queer and raunchy, raw and occult and vulnerable as she moves between worlds in search of the divine and the self.

Published: June 17, 2019 at 04:30AM

from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2RhzoL2

0 notes

Text

In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos

By DIANA ARTERIAN

The writing in Reines’s new collection is queer and raunchy, raw and occult and vulnerable as she moves between worlds in search of the divine and the self.

Published: June 17, 2019 at 09:00AM

from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2RhzoL2

via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

"In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos" by DIANA ARTERIAN via NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2RhzoL2

0 notes

Text

In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos

By Diana Arterian

The writing in Reines’s new collection is queer and raunchy, raw and occult and vulnerable as she moves between worlds in search of the divine and the self.

Published: June 17, 2019 at 12:56PM

from NYT Books https://nyti.ms/2RhzoL2

via IFTTT

0 notes

Quote

I wish I could be sated by the wine of his beauty

or, burned in the flames of his love, become the master of his heart

I wish I could be a teardrop blooming on the flower of his face

or a curl of his perfumed hair

I wish I could be the dust sitting in his path

or under the sun of his gaze, melting bit by bit

I wish I could be a secret parading before him

or become rare words on his still lips

I wish I could accompany my friend, like a shadow in each breath,

or stay up until dawn from the thrill of his presence

I am devoting my mind to my heart’s hope, which breaks from separation

I am closing the door on grief, becoming moonlight from head to toe

“I wish” (ghazal)

Nadia Anjuman

translated by Diana Arterian and Marina Omar

#Nadia Anjuman#there is a decided difference in aesthetics b/w trad. English & Middle-East/Spanish poetry#namely the fervent emotion that boils over in the latter#national poetry month#ghazal#poetry

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

"In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos" by DIANA ARTERIAN via NYT https://t.co/vrt3o5D1Rq https://t.co/vuKxUxhqFl

"In ‘A Sand Book,’ Ariana Reines Finds Ecstasy in Chaos" by DIANA ARTERIAN via NYT https://t.co/vrt3o5D1Rq pic.twitter.com/vuKxUxhqFl

— Alejandro Ruiz Criado (@alejandroruizcr) June 17, 2019

from Twitter https://twitter.com/alejandroruizcr

June 17, 2019 at 09:17PM

via IFTTT

0 notes

Link

PART I: Diana Arterian Interviews Andrew Wessels

Andrew Wessels’s book traces a day’s walk through Istanbul, placing itself in dialogue with the flâneur figure in W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. Yet A Turkish Dictionary also regards the profound impact a nation’s leader can have on language, historical record, and artifacts. It can be chilling to read, considering the tack many current world leaders are taking, the echoes of the past into the present. The collection is a thoughtful investigation of these concerns in conjunction with the self, curiosity, documentation, religiosity. So few poets can hold all these subjects in a single volume with such poise. Andrew and I only began to know one another after meeting randomly and agreeing to exchange our first manuscripts, and, even while reading an early draft, I was thrilled by the engines of the book, its lineage — and where it might lead. It reminded me of Barthes: “Is not the most erotic portion of a body where the garment gapes? […] it is this flash itself which seduces, or rather: the staging of an appearance-as-disappearance.” What the body of A Turkish Dictionary reveals is a complex act of guiding that Wessels accomplishes with apparent ease.

¤

DIANA ARTERIAN: Andrew, I’m so thrilled to have the opportunity to speak with you about A Turkish Dictionary. I saw an earlier iteration of it years ago, and it matured to an even richer text than the one I had originally encountered.

Last year you were living in Turkey at a time when the pendulum, which once swung hard in the direction of Westernization (via Atatürk), was pushed toward extreme nationalism (via Erdoğan), forcing you out of the country. Though books are often written far ahead of publication (and I know ATD was, too), there is a puncture of the present moment in a footnote regarding a suicide bomber attacking a place you wrote about in the book. Erdoğan’s increasingly despotic acts in conjunction with the publication of ATD made you decide to leave in order preserve your safety, which seemed beyond unlikely years before. When you were writing the book did it feel like you were documenting this transition?

ANDREW WESSELS: The book was written before the current upheaval in Turkey (failed coup attempt, terrorist attacks, government’s hard move toward authoritarianism). That moment of the suicide bomber came after the book was finished but during the final editing and production process, so the present was continuously pushing into the book. Istanbul is, if anything, proof of constant change and the impossibility of true stasis. So the current changes are a continuation of that reality. I’ve noticed how some lines in the book mean new things now: “Oh Atatürk, where did they put your words” initially was written to interact with the Turkish language reforms. But now, with Erdoğan’s rise toward dictatorial powers, the curtailing of secular institutions, and the general move away from Atatürk’s Kemalist policy, that line has taken on a different significance. Everything changes, including the meaning of the words in this book.

This feels ironically apt considering the book is, in fact, a sort of dictionary, shining a light on Atatürk’s decision regarding the Turkish language’s speedy metamorphosis.

The Turkish language reform was two primary things. First, Atatürk transitioned the Turkish language from Arabic script to Latin script. Second, as part of creating a Turkish nationalistic identity, the Ottoman Turkish language was purged of any words that had been borrowed over the course of previous centuries. The idea was to create a “pure” Turkish language written in Latin script. So, virtually overnight, a huge chunk of the language suddenly ceased to exist, at least officially. New words had to be created on the spot to replace words that had ceased to exist.

What I was interested in with the opening section “&language” is seeing what happens when words are used in different ways. What happens when this word is placed next to this word? What happens when this word is removed or erased? I wanted to explore that process in real time, and, as I mentioned before, what I’ve learned is that these words have continued to change meaning as the world changes rapidly.

ATD circles predominantly around a kind of awe and terror in the face of such absolute power, and how that power influences historical legacy and knowledge. There is the power of extreme linguistic modification that Atatürk enacted, or Erdoğan demanding the destruction of a recently erected statue meant to signify peace between Turkey and Armenia. In the face of this, you state, “I must accept the rate at which information degrades as time carries it forward, away from its source.” This can be read as flippant considering the circumstances, no?

I thought a lot about power as I wrote this, and specifically about the power to tell the stories of the past. Standing in Sultanahmet Square, one can see the Hagia Sophia, the Blue Mosque, and the remnants of the Hippodrome. It’s a space that has been fought over for thousands of years. To stand there is to stand where countless wars and deaths have occurred and, as the recent suicide bombing shows, continue to occur. I began to be interested in what names remained and what names were erased. Constantine and Justinian and Enrico Dandolo and Fatih and Atatürk and Erdoğan: These are the leaders whose names remain inscribed over and over and over again, and thus the names that are the hardest to erase. But to stand there is to recognize that there were countless people who were beneath these leaders, sent to their deaths. If we look for them, we won’t see their names, but the tracings of their ghosts might still remain.

In ATD you see how those who had power made quick work of altering that space in order to hew a particular narrative that served the vision of what they wanted for Turkey. Thus in your book you document the physical palimpsest of a city that Istanbul is, once being Byzantium and then Constantinople, while also a prodding at what is visible, dormant, or invisible. The images are so evocative, as with the Christian mosaics covered in plaster by the Ottomans, which archeologists are now carefully uncovering. I found your investigation destabilizes trust in the visible and the powerful in the face of curated cultural or historical spaces.

Again, there is really no stasis. The Hagia Sophia (which is actually the third Hagia Sophia built on that site) was a great cathedral. Then, upon first conquering the city, Fatih rode in on his horse and consecrated the space as a mosque, eventually adding minarets to the building, covering the interior designs in plaster, and adjusting the prayer space to face Mecca. After the formation of the Turkish Republic, it became a museum space designed to show this split history. Most recently, Erdoğan’s government has allowed for the call to prayer to emanate from the minarets for the first time (other than very special occasions) in nearly a century. Buildings and cities are nexus points or sites for change, and thus are places for power to exert themselves and to display their exertion.

In the United States, we see that on a grand and totalizing scale with the nearly total destruction of Native American histories and archaeologies at least outside of museum exhibits. A function of power is to control what we see. By not seeing these Native American histories, we are freed from realizing our history of genocide and destruction. We can be absolved of (or at least forget that we need to impose upon ourselves) guilt. We can rationalize our actions.

While I hadn’t considered this topic as one so clearly connected to your book until now, I would be remiss if I didn’t bring up the violence in our own country in response to the removal of statues and markers of our past violence and bloody history, particularly in the South. The poet Robin Coste Lewis recently stated that the Confederate statues need to be put in a museum so we don’t forget. I was so grateful for that insight as the removal of the statues terrified me nearly as much as the white supremacists’ responses to their removal. Pulling these statues down blots out not only the physical markers of the Civil War and slavery here in the United States, but, more important, the desire to commemorate those brutal practices — and the vocal portion of the white American population’s enduring interest in saluting what they represent.

I think this is a great and important connection to make. In The Patria, one of the oldest histories of Constantinople written in approximately the ninth century, there is a famous section on statues that outlines a walking tour of the city. It was designed to guide a tourist through the Greek and Roman sculptures that had been brought to Constantinople by the various rulers, statues that were quite strange and unknowable to the now-Christian populace. Within a few centuries of the initial writing of this text, virtually all of these monuments had been lost or destroyed, and as the city has continued to change, it is impossible to accurately describe on a map what the walking tour itself was.

Keeping problematic monuments up is obviously wrong to hold up violent, oftentimes evil values or histories. Destroying them creates an erasure that can paper over the past and absolve without restitution. But institutionalizing them creates its own problems. A museum can contextualize, but a museum can also contextualize in equally problematic ways depending on who is doing the curating. By taking monuments in and presenting them as critique, these institutions also coalesce greater power themselves. There is also the ethics of acquirement as moving cultural capital from one location to another, such as the Pergamon Altar in Berlin or the Elgin Marbles in London. It is hard to find a good, firm answer because we’re talking about the most inhumane things that humans can possibly do to each other.

The thing I find most strange is the belief that a monument is static in some way. That a statue that we know was erected 85 years ago didn’t exist before then. That we believe, despite all evidence to the contrary, that it will remain. That the monument is anything more than an expression of power and belief at a single point in time, and thus a site for us to reevaluate power and belief now. These representations, whether in Istanbul or in the United States, are sites of power struggles and determinations of who gets to say how we see and represent ourselves right now.

Absolutely — and I believe we discussed Thessaloniki, Greece, (Atatürk’s birthplace) months ago when I traveled there and saw physical palimpsests and traces of struggle between Greece, the Roman Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. There was an ancient cathedral in particular with the last standing minaret from the Ottoman period in its courtyard. Above the cathedral’s entryway is Arabic script from when it functioned as a mosque, as well as a more modern painting of Saint George just above that text. In the spirit of ATD, I’ll include the photo I snapped of that doorway.

Having these physical remnants feels so urgent to learning what took place throughout the world (if the remnants survive conflict, governments, and/or erosion). As a traveling outsider, it is an entry point to a more comprehensive understanding of a place. How did you decide to engage with the city of Istanbul this way through your writing? Though you have substantive connections to Turkey, did it ever give you pause to write about the country and its capital, especially concerning the long and checkered history of an Anglo male body moving through an “exotic” space and attempting to document it?

This has been a deep concern of mine and a line of interrogation as I wrote the book, and as I traveled in and lived in Istanbul and Turkey over the years. The short and personal answer is that this book is, in large part, about my faith and conversion. I’m a straight, white man, and I am also a Muslim man, and at least for me writing this book was part of my coming into my faith. Istanbul is where and how that happened. Additionally, writing this book was about me building a dual-cultural life with my partner Zeliha, who is Turkish. It is a space that is not my home but that has become my home.

The history of Istanbul at least in the Western imaginary is primarily seen through the lens of Western travelers. For a variety of reasons, very few Ottoman-era writers are translated, and while there have been more modern Turkish writers translated, they still are largely ignored outside of a certain subset of readers. So I sought to engage these histories and these elisions and the ongoing transformation of the city alongside my own personal transformations. I wrote a little bit more about this larger question for LARB in response to Suzy Hansen’s recent book on Turkey and American imperialism.

One concept you’ve brought up a couple of times that I haven’t engaged with yet directly is the idea of the palimpsest. The city is always recognizable as itself and yet is always changing. As I converted, my body felt similarly. Some physical aspect (discounting the fact that our cells themselves are constantly regenerating us anew) stayed the same, while something else — my perspective, my belief system — was revealed to me as similarly fluid and negotiable. I was simultaneously the same and different. And as I explored this in my walk and in compiling the final book, this palimpsest arose again and again, in the word, in the image, in history, in faith itself.

¤

Part II. Andrew Wessels Interviews Diana Arterian

The most direct thing I can say about Diana Arterian’s writing is that the more time I spend with her work, the more engaged, challenged, and enlightened I am by it. Playing Monster :: Seiche is a blistering and important work of poetry, a book whose impact far exceeds the boundaries of a typical debut collection. As I write this introduction and return again to this book, I find myself unable to stop myself from reading it again in full. So often, we talk of how much we like and enjoy a book. Arterian’s work demands that weightier conversation as each page investigates the fallout of our personal histories and traumas, the possibilities and boundaries of confession, and the ways that we can create, heal, and recreate ourselves through writing and reading.

¤

ANDREW WESSELS: I read Playing Monster :: Seiche first in manuscript form, and when you see a book designed and published, something happens to it. I think this overall design changes the book in really wonderful ways.

DIANA ARTERIAN: Indeed the work, once designed and printed, is a totally different animal. I have to give credit where it is due, and you’ve given me the opportunity: Joseph Kaplan designed the book, making it totally gorgeous and modern while simultaneously giving it the necessary markers to relay a complicated form. It moves between two (or, really, three) different threads, and I had a lot of anxiety leading up to Joseph’s work on how exactly this would manifest itself.

It really is gorgeous, and the design helps a reader navigate the various threads and complexities naturally. I want to start our conversation talking about the subtitle of your collection: Seiche. Would you explain what a “seiche” is and how that concept relates to your collection?

Your question points to the complicated nature of the form of this book, actually — “Seiche” is a second title, rather than a subtitle (initially these were two books with those two titles). “Seiche” is a standing wave that moves across a body of water without ever breaking. This doesn’t necessarily happen on its surface, but also can occur in its depths. Oftentimes a seiche is precipitated by a traumatic event, such as an earthquake.

As I read, I couldn’t help but apply the concept of the seiche to everything, from the overarching narrative threads weaving through the book to the interplay between words. I’d like to investigate some of these a bit deeper, if you don’t mind. First, can you talk about how the seiche relates to some of the main narratives: the binary of the father and mother, the relationship between the speaker and her family/history, the saga of the mother?

I gravitated toward the seiche image predominantly because it so perfectly encapsulates a feeling of dread. Or an image of simultaneous stasis and movement. In the “Playing Monster” pieces, you’re seeing the impact of an abusive sociopath on a family from the perspective of his child (myself). This damage is rarely enacted through instances of rupture, but rather through the cultivation of extreme psychological terror between those moments.

In the narrative ascribed to the “Seiche” thread, my mother is years beyond extracting her children and herself from that life, yet finding herself terrorized by several people, predominantly a stalker. I also included the abuse sustained by the woman who helped care for us as children — the prevalence of danger to us, her, and so many other (often) women and children, felt important.

This book is acting simultaneously as a witnessing of these events and as a confessional. Your collection intersects with various approaches to the confessional that make me think of how Alice Notley incorporates the real, the remembered, the abstracted, the surrealed, the felt, the sensed, the predicted, and the propheted, all within the confessional. Can you talk more about how you’ve approached the confessional?

When I started writing “Playing Monster,” which came before the “Seiche” poems, I wasn’t really thinking all that much about what I was doing. It was during the final year of my MFA and I needed to write a collection for my thesis — I wasn’t thinking about how these poems were possible in large part to many poets who laid the groundwork for exposure of the personal on the page and the feeling that nothing is sacred. This was a thoroughly naïve act in many ways, not simply for its lack of regard for literary history. I became aware of this naïveté through the emotional responses to the completed thesis from those close to me, which gave me serious pause. I had many friends write me and provide a list of page numbers that caused them to break down into tears. In addition, my mother, with my permission, began sending the manuscript to friends. These friends would often write back with similar reactions (which she then forwarded back to me). I didn’t much know what to make of this strange circuit of sadness, and it provoked a deep anxiety regarding the production of such material in the world that often seems defined by suffering. It felt, for the most part, like a spreading of pain or an attempt at emptying my own pain into the reader, which was not my intention. After some years of hand-wringing I decided it felt important to publish predominantly because the stability of the home is often a false facade — the home of the educated, white, middle-class family, in particular.

I’m really interested in how you see the manuscript. It seems like you still see the dividing lines between “Playing Monster” and “Seiche.” As a reader, the collection feels like such a complete whole. I couldn’t begin to parse out what would be in one versus in the other. I want to look at the untitled poem on pages 64–65, which presents an “I” speaking that isn’t you, and then there’s the story of a woman and her mental illness, life, and death in two different versions. How do these doublings, these binaries, these two separate manuscripts, both break apart and fuse?

Well, you’ve caught me in my being slow to accept these books as one. My continued discussion of them as two has mostly to do with the fact that they were two books for longer than they have been a single volume, so I’m excited for its lifetime as a unified entity as it always should have been! They are indeed one story, as so much of life is — particularly the lives of those who survive abuse, which, more often than not, include the resurfacing of that reality again and again despite one’s best efforts (a kind of terrible subconscious self-sabotage frequently experienced by survivors). In addition, so much of adult life can feel like a recognition of echoes of your past.

What I hope is formally compelling in Playing Monster :: Seiche is that it illustrates moments of clear intersection between past and present while simultaneously honoring the depth and difference of each reality. Including my mother’s voice in a poem (and other voices in other pieces) felt important for this reason. I’m not the only player in this series of events. So maybe the book feels less like a binary than a diptych, to me.

Forgive me, but I’m in the middle of watching the new season of Twin Peaks, so I’m thinking a lot about Americana and how America is both filled with highly unique locations due to its geography as well as this uniform Americanness that blankets the country. How did you see location and place while writing this, and how did you let it embody and inform your poetry?

In terms of location, the events in the book take place in central Arizona (“Playing Monster”) and upstate New York (“Seiche”). These two regions felt and feel to be, in many ways, polar opposites from one another. Playing Monster :: Seiche has a “uniform Americanness” not so much due to the physical landscapes within the book but rather because abuse has happened and is happening everywhere in this country. The events in the “Playing Monster” poems took place at a time when that fact was receiving more and more attention — divorce proceedings began to include information regarding abusive spouses and parents in the 1990s. Prior to that point it was considered a private affair of the family or — particularly in the height of heteronormative 20th-century America — a father’s appropriate means of running his household. This is not to say that abuse is an American phenomenon (in the least), but rather the “Playing Monster” poems are an attempt to give insight into the abusive American household that is domestic, middle class, very educated, and white when it is otherwise often an experience ascribed to the foreign, poor or working class, less educated, and/or families of color.

Beyond this, to include the “Seiche” thread in this response, the overarching aim of the book is an attempt to document the ubiquitousness yet simultaneous invisibility of the patriarchal oppressions in the United States, and the many forms in which those oppressions manifest themselves.

One thing I’ve noticed as my book comes out is that there is a divergence or at least a distance between my own purpose for writing the book and a reader’s purpose for reading the book. I think the personal nature of poetry especially highlights this difference. How do you see this distance between your purpose and a reader’s purpose, and how do you think that might add to the ultimate impact of your collection?

Considering a “reader’s purpose” is a tough charge — especially a reader of poetry. It is often a moving target (to be moved? to learn something? to complete a reading assignment?). I suppose my hope is that my readers do learn something — and that something is beyond merely the fact that patriarchy is a drag (to put it lightly). I’m not entirely sure what I hope that takeaway is, or that it is easy to label. Overall, my deepest hope is that my work does not simply upset people.

My mother read a galley of the book and her takeaway was that everyone can and often does function as a monster to one person or another. That slippery shifting of victim to perpetrator and vice versa is one most of us have witnessed or experienced. While that was not my impulse, I think she’s right.

In addition to this book, you’ve previously published two chapbooks, and have a second manuscript in a final draft state. How do you see Playing Monster :: Seiche interacting with these other works, and how does it undergird, add to, and expand upon the work you do and want to do as a writer?

M. NourbeSe Philip writes, “As with most writers, an issue chooses you.” The issue that chooses me again and again is the role of the witness in oppressive environments. Often I find myself pulled in a direction only to recognize later that what provoked me to write Playing Monster :: Seiche also drew me to translate the late Afghan poet Nadia Anjuman, write poems on an ancient Roman Empress, and pen hybrid nonfiction about my romantic relationship with a Pakistani-American man while we watch Islamophobia reach the point of fever pitch. So who the witness is and what they are witnessing may change, but it is always present in my work.

Often witnessing can feel like the final means of exacting agency when a person, group, or system has thoroughly stripped it from you. You become a recorder, anxiously waiting for the opportunity to recall what you have endured before someone who can enact justice (at best) or recognition (at least). I felt like so much of my childhood was defined by what I was seeing and watching for (which are ultimately different endeavors). This is why I include a poem early on in the book in which my father told me to look at a deer and “remember for the rest of [my] life.” I followed his instructions, but with a more damning and personal focus than he intended, and an extended interest in “remembering” other horrors, both personal and public.

¤

Diana Arterian is the author of the poetry collection Playing Monster :: Seiche (1913 Press), the chapbooks With Lightness & Darkness and Other Brief Pieces (Essay Press) and Death Centos (Ugly Duckling Presse), and co-editor of Among Margins: Critical & Lyrical Writing on Aesthetics (Ricochet).

Andrew Wessels is a poet and translator who currently lives in Los Angeles. He has lived in Istanbul, Turkey, where he taught writing at Koç University. His first book of poems, A Turkish Dictionary, was published by 1913 Press in 2017, and Semi Circle, a chapbook of translations of Nurduran Duman’s poems, is available from Goodmorning Menagerie.

The post A Dialogue on First Books, in Two Parts appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books http://ift.tt/2FCU0rC

0 notes

Link

Among Margins made it onto SPD’s October bestsellers list!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Don't rush—this road is a dead end!

Why gallop toward infinity?

*

from “Drink! Drink!” by Nadia Anjuman (translated by Diana Arterian and Marina Omar)

10 notes

·

View notes