#Tamar Herzig

Text

[Storia di un ebreo convertito][Tamar Herzig]

Tamar Herzig getta luce sulle relazioni ebraico-cristiane, il mecenatismo e l’omosessualità nelle città italiane del XV e XVI secolo

Nato a Firenze a metà del Quattrocento da una famiglia ebraica, l’orafo Salomone da Sessa si trasferì a Ferrara, dove i suoi raffinati gioielli e le sue spade riccamente decorate erano ritenute di altissimo pregio dalle donne e dagli uomini di potere allora più importanti in Italia. Voci scandalose sul suo conto iniziarono a circolare all’interno della comunità ebraica, che lo denunciò alle…

View On WordPress

#2023#A Convert&039;s Tale#Art#arte#Crime and Jewish Apostasy in Renaissance Italy#criminalità e religione nell&039;Italia del Rinascimento#Donatella Downey#nonfiction#Rinascimento#Saggi#Saggistica#Stefano U. Baldassarri#storia#Storia di un ebreo convertito#Tamar Herzig#Viella Editrice

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Stupri e schiavitù, una ricerca mette in cattiva luce Borromei primo Gonfalone di Livorno, la storia su Il Venerdì di Repubblica

Stupri e schiavitù, una ricerca mette in cattiva luce Borromei primo Gonfalone di Livorno, la storia su Il Venerdì di Repubblica

La lettera di Gadi Polacco

Lo screenshot dell’articolo sul Venerdì di Repubblica

Livorno 11 giugno 2022

Bernaddetto Borromei, il primo Gonfalone di Livorno, ancora oggi onorato da una via nella nostra città labronica, e impersonato dai sindaci di Livorno durante la ricorrenza del compleanno della città sembra perdere di prestigio agli occhi della storia.

Nuovi documenti portati alla luce da Tamar Herzig, professore di…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

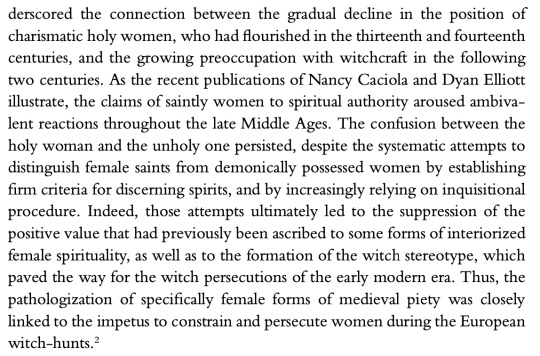

Tamar Herzig, excerpt from Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics

3 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[T]he charismatic and ascetic leaders of such [heretical] groups in Bohemia and Moravia often enjoyed a popular reputation as holy men because of the great austerity and purity of their lives. Some of the Bohemian heretics engaged in prophetic activities, while others were popular healers, and their healing powers were regarded as an indication of their holiness. Although they opposed the veneration of saints, some of them were perceived as "living saints," and were even addressed as "sancti viri." Their saintly reputation doubtlessly contributed to the relative success of the heretical sects that flourished in the Kingdom of Bohemia - despite the heavy persecution that they suffered - during the years 1470-1500.

Tamar Herzig, “Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics” in Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft (2006) 1(1):24-55

#quotes#original post#european#bohemian#czech#slavic#moravian#bohemia#moravia#christian#christianity#tamar herzig

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Science of Demons: Early Modern Authors Facing Witchcraft and the Devil (Routledge Studies in the History of Witchcraft, Demonology and Magic), edited by Jan Machielsen, Routledge, 2020. Info: routledge.com.

Witches, ghosts, fairies. Premodern Europe was filled with strange creatures, with the devil lurking behind them all. But were his powers real? Did his powers have limits? Or were tales of the demonic all one grand illusion? Physicians, lawyers, and theologians at different times and places answered these questions differently and disagreed bitterly. The demonic took many forms in medieval and early modern Europe. By examining individual authors from across the continent, this book reveals the many purposes to which the devil could be put, both during the late medieval fight against heresy and during the age of Reformations. It explores what it was like to live with demons, and how careers and identities were constructed out of battles against them — or against those who granted them too much power. Together, contributors chart the history of the devil from his emergence during the 1300s as a threatening figure — who made pacts with human allies and appeared bodily — through to the comprehensive but controversial demonologies of the turn of the seventeenth century, when European witch-hunting entered its deadliest phase. This book is essential reading for all students and researchers of the history of the supernatural in medieval and early modern Europe.

Contents:

List of figures

Notes on contributors

Acknowledgements

Editor’s nore

Introduction: The Science of Demons – Jan Machielsen

Part 1: Beginnings

1. The Inquisitor’s Demons: Nicolau Eymeric’s Directorium Inquisitorum – Pau Castell Granados

2. Promoter of the Sabbat and Diabolical Realism: Nicolas Jacquier’s Flagellum hereticorum fascinariorum – Martine Ostorero

Part 2: The First Wave of Printed Witchcraft Texts

3. The Bestselling Demonologist: Heinrich Institoris’s Malleus maleficarum – Tamar Herzig

4. Lawyers versus Inquisitors: Ponzinibio’s De lamiis and Spina’s De strigibus – Matteo Duni

5. The Witch-Hunting Humanist: Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola’s Strix – Walter Stephens

Part 3: The Sixteenth-Century Debate

6. ‘Against the Devil, the Subtle and Cunning Enemy’: Johann Wier’s De praestigiis daemonum – Michaela Valente

7. The Will to Know and the Unknowable: Jean Bodin’s De La Démonomanie – Virginia Krause

8. Doubt and Demonology: Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft – Philip C. Almond

9. Demonology and Anti-Demonology: Binsfeld’s De confessionibus and Loos’s De vera et falsa magia – Rita Voltmer

10. A Royal Witch Theorist: James VI’s Daemonologie – P. G. Maxwell-Stuart

11. Demonology as Textual Scholarship: Martin Delrio’s Disquisitiones magicae – Jan Machielsen

Part 4: Demonology and Theology

12. ‘Of Ghostes and Spirites Walking by Nyght’: Ludwig Lavater’s Von Gespänsten – Pierre Kapitaniak

13. A Spanish Demonologist During the French Wars of Religion: Juan de Maldonado’s Traicté des anges et demons – Fabián Alejandro Campagne

14. Scourging Demons with Exorcism: Girolamo Menghi’s Flagellum daemonum – Guido Dall’Olio

15. The Ambivalent Demonologist: William Perkins’s Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft – Leif Dixon

16. Piety and Purification: The Anonymous Czarownica powołana – Michael Ostling

Part 5: Demonology and Law

17. An Untrustworthy Reporter: Nicolas Remy’s Daemonolatreiae libri tres – Robin Briggs

18. The Mythmaker of the Sabbat: Pierre de Lancre’s Tableau de l’inconstance des mauvais anges et démons – Thibaut Maus de Rolley and Jan Machielsen

19. An Expert Lawyer and Reluctant Demonologist: Alonso de Salazar Frías, Spanish Inquisitor – Lu Ann Homza

Critical editions and English translations of demonological texts

Index

#book#essay#weird essay#witchcraft#demonology#Studies in the History of Witchcraft Demonology and Magic

17 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[Heinrich] Kramer argues that women's minds are "naturally more impressionable" than the minds of men, and are therefore "more ready to receive the influence of a disembodied spirit." This contention is based on the assumption that, because of their moist and cool bodily humors, women receive impressions more easily, retain them better, and are less capable of critically evaluating them than are men. In the Malleus [Maleficarum], he acknowledges the fact that not all the impressions that women uncritically receive have a diabolical origin. In fact, he contends that "when they [women] use this quality [of their greater impressionability] well they are very good, but when they use it ill they are very evil." ... Kramer apparently assumes that only members of the female sex, deprived as they are of the capability to critically evaluate the images that influence their minds, can reach such a perfect degree of Imitatio Christi.

Tamar Herzig, “Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics” in Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft (2006) 1(1):24-55

2 notes

·

View notes

Quote

[Heinrich] Kramer assumes that holy women can represent the divine, but that their ability to do so reflects their being essentially different from men, and especially their inherent psychological and intellectual depravity ... Kramer's insistence on women's greater proclivity to witchcraft actually went hand-in-hand with his admiration for the traditional features of medieval female sanctity.

Tamar Herzig, “Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics” in Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft (2006) 1(1):24-55

1 note

·

View note

Quote

Because secure banking facilities were not easily available to all, burying amassed wealth was a prevalent practice in late medieval and early modern Italy. Thus, it was not implausible to imagine that the knowledge of such hidden treasures would sink into oblivion upon the death of the individuals who had originally buried them, and that they could be discovered with supernatural assistance. Contemporaries also assumed that owners of hidden treasures often pronounced some sort of curse to protect them from potential thieves, or had resorted to demonic assistance in guarding their buried riches. Demons, who were generally believed to have supernatural knowledge of human affairs, could reveal the location of large sums of money or jewelry buried in secret places, and could also protect the treasure hunters from supernatural dangers. Necromantic books that circulated in the late fifteenth century, such as the popular Clavicula Salomonis (Lesser Key of Solomon), instructed the practitioners of learned magic how to obtain demonic assistance in locating buried treasures. Treasure hunting was the most common pastime of clerical necromancers, and priests and friars continued to be the central figures in groups engaged in the pursuit of hidden riches in Northern Italy well into the seventeenth century.

Tamar Herzig, “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna” in Renaissance Quarterly (2011) 64(4):1025-1028

49 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The rites of demonic magic were contained in books and presupposed a command of Latin. Hence, most practitioners of demonic magic in the late Middle Ages belonged to Europe's educated elite. Necromancers were commonly individuals who were clerics, including university students and men in minor orders - often monks, friars, or diocesan priests. These shadowy figures of what Richard Kieckhefer calls the clerical underworld deliberately engaged in what they knew to be forbidden practices, although some of them probably persuaded themselves that they were merely following Jesus in coercing demons with divine assistance. Necromancers usually performed complex ceremonies in order to summon demons who would enable them to win sexual favors from women or to discover hidden treasures. To protect themselves from potentially harmful supernatural powers, they undertook specific ascetic practices, such as fasting, before calling up demons.

Tamar Herzig, “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna” in Renaissance Quarterly (2011) 64(4):1025-1058

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tamar Herzig, excerpt from Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics

50 notes

·

View notes

Quote

In the Franciscan tradition, stigmata were reserved for the holy man Francis. Moreover, as Franciscan theologians strove to emphasize the visible dimension of the Poverello's divine gifts, they were concurrently intent on discouraging devout women within their order from publicizing accounts of their paramystical experiences - that is, of physical phenomena attesting to their unmediated contacts with the divine ... In the Dominican order, in contrast, stigmatization came to be regarded as a specifically female religious experience. Prominent Dominicans strove to promote the fame for sanctity of ecstatic women affiliated with their order who desired to imitate the suffering of the crucified Christ.

Tamar Herzig, “Stigmatized Holy Women as Female Christs” in Archivio italiano per la storia della pietà 26 (2013) edited by Gábor Klaniczay

0 notes

Quote

Clerical necromancers often employed virgin boys in the process of invoking demons in the hope of learning hidden things, and especially for discovering the location of buried treasures. The practitioners of demonic magic assumed that young boys, not yet sexually mature, would alone be able to see conjured spirits, and that their interpretation of the spirits' responses would be unbiased. Italian priests also sometimes resorted to exorcising demoniacs before embarking on a treasure hunt, in order to obtain helpful information from the diabolic entities that possessed them.

Tamar Herzig, “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna” in Renaissance Quarterly (2011) 64(4):1025-1058

0 notes

Text

Christianity - Articles

Last edited 2020-05-14

Anton, A. E. “’Handfasting’ in Scotland.”The Scottish Historical Review 37, no. 124 (October 1958): 89-102.

Bailey, Michael D. “From Sorcery to Witchcraft: Clerical Conceptions of Magic in the Middle Ages.” Speculum 76, no. 4 (2001): 960-990.

* Beichtman, Philip. “Miltonic Evil as Gnostic Cabala.” Esoterica 1 (1999): 61-78.

* Blécourt, Willem de. “Witch doctors, soothsayers and priests: On cunning folk in European historiography and tradition.” Social History 19, no. 3 (1994): 285-303.

Boer, Roland. “Religion and Socialism: A. V. Lunacharsky and the God-Builders.” Political Theology 15, no. 2 (March 2014): 188-209.

Boyd, Lydia. “The gospel of self-help: Born-again musicians and the moral problem of dependency in Uganda.” American Ethnologist 45, no. 2 (May 2018): 241-252.

* Bylina, Stanisław. “The Church and Folk Culture in Late Medieval Poland.” Acta Poloniae HIstorica 68 (1993): 27-42.

* Campagne, Fabián Alejandro. “Witches, Idolaters, and Franciscans: An American Translation of European Radical Demonology (Logroño, 1529 - Hueytlalpan, 1553).” History of Religions 44, no. 1 (August 2004): 1-35.

* Chakraborty, Suman. “Women, Serpent and Devil: Female Devilry in Hindu and Biblical Myth and its Cultural Representation: A Comparative Study.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 18, no. 2 (January 2017): 156-165.

Chatman, Michele Coghill. “Talking About Tally’s Corner: Church Elders Reflect on Race, Place, and Removal in Washington, DC.” Transforming Anthropology 25, no. 1 (April 2017): 35-49.

* Cianci, Eleonora. “Maria lactans and the Three Good Brothers: The German Tradition of the Charm and Its Cultural Context.” Incantatio 2 (2012): 55-70.

Collins, David J. “Albertus, Magnus or Magus? Magic, Natural Philosophy, and Religious Reform in the Late Middle Ages.” Renaissance Quarterly 63, no. 1 (2010): 1-44.

* Daǧtaş, Seçil. “The Civilizations Choir of Antakya: The Politics of Religious Tolerance and Minority Representation at the National Margins of Turkey.” Cultural Anthropology 35, no. 1 (2020): 167-195.

* Díaz, Mónica. “Native American Women and Religion in the American Colonies: Textual and Visual Traces of an Imagined Community.” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers 28, no. 2 (2011): 205-231.

* Draper, Scott and Joseph O. Baker. “Angelic Belief as American Folk Religion.” Sociological Forum 26, no. 3 (September 2011): 624-643.

* Elder, D. R. “’Es Sind Zween Weg’: Singing Amish Children into the Faith Community.” Cultural Analysis 2 (2001).

Elisha, Omri. “Dancing the Word: Techniques of embodied authority among Christian praise dancers in New York City.” American Ethnologist 45, no.3 (August 2018): 380-391.

* Fanger, Claire. “Things Done Wisely by a Wise Enchanter: Negotiating the Power of Words in the Thirteenth Century.” Esoterica 1 (1999): 97-132.

Friedner, Michele Ilana. “Vessel of God/Access to God: American Sign Language Interpreting in American Evangelical Churches.” American Anthropologist 120, no. 4 (December 2018): 659-670.

* Galman, Sally Campbell. “Un/Covering: Female Religious Converts Learning the Problems and Pragmatics of Physical Observance in the Secular World.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 44, no. 4 (December 2013): 423-441.

* Henderson, Frances B. and Bertin M. Louis, Jr. “Black Rural Lives Matters: Ethnographic Research about an Anti-Racist Interfaith Organization in the United States.” Transforming Anthropology 25, no. 1 (April 2017): 50-67.

* Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna.” Renaissance Quarterly 64, no. 4 (2011): 1026-1058.

* –. “Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics.” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 1, no. 1 (2006): 24-55.

* Hobgood-Oster, Laura. “Another Eve: A Case Study in the Earliest Manifestations of Christian Esotericism.” Esoterica 1 (1999): 48-60.

* Jakobsson, Sverrir. “Mission Miscarried: The Narrators of the Ninth Century Missions to Scandinavia and Central Europe.” Bulgaria Medievalis 2 (2011): 49-69.

* Johanson, Kristiina. “The Changing Meaning of “Thunderbolts.” Folklore 42 (2009): 129-174.

* Kulik, Alexander. “How the Devil Got His Hooves and Horns: The Origin of the Motif and the Implied Demonology of 3 Baruch.” Numen 60 (2013): 195-229.

* Láng, Benedek. “Characters and Magic Signs in the Picatrix and Other Medieval Magic Texts.” Acta Classica Universitatis Scientiarum Debreceniensis 47 (2011): 69-77.

* Nelide, Romeo, Olivier Gallo, and Giuseppe Tagarelli. “From Disease to Holiness: Religious-based health remedies of Italian folk medicine (XIX-XX century).” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 11, no. 50 (June 2015).

* Oak, Sung-Deuk. “Competing Chinese Names for God: The Chinese Term Question and Its Influence upon Korea.” Journal of Korean Religions 3, no. 2 (October 2012): 89-115.

* Ostling, Michael. “The Wide Woman: A Neglected Epithet in the Malleus Maleficarum.” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 8, no. 2 (Winter 2013): 162-170.

Perlmutter, Jennifer R. “Knowledge, Authority, and the Bewitching Jew in Early Modern France.” Jewish Social Studies 19, no. 1 (Fall 2012): 34-52.

Ramirez, Michelle and Margaret Everett. “Imagining Christian Sex: Reproductive Governance and Modern Marriage in Oaxaca, Mexico.” American Anthropologist 120, no. 4 (December 2018): 684-696.

Robbins, Joel. “Keeping God’s distance: Sacrifice, possession, and the problem of religious mediation.” American Ethnologist 44, no. 3 (August 2017): 464-475.

* Russell, Caskey. “Cultures in Collision: Cosmology, Jurisprudence, and Religion in Tlingit Territory.” The American Indian Quarterly 33, no. 2 (Spring 2009): 230-252.

* Stryz, Jan. “The Alchemy of the Voice at Ephrata Cloister.” Esoterica 1 (1999): 133-159.

* Vaz da Silva, Francisco. “Cosmos in a Painting - Reflections on Judeo-Christian Creation Symbolism.” Cosmos: The Journal of the Traditional Cosmology Society 26 (2010): 53-78.

* –. “The Madonna and the Cuckoo: An Exploration in European Symbolic Conceptions.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 46, no. 2 (2004): 273-299.

* Versluis, Arthur. “Western Esotericism and The Harmony Society.” Esoterica 1 (1999): 20-47.

* Yamauchi, Edwin M. “Magic in the Biblical World.” Tyndale Bulletin (1983): 169-200.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Christianity - Chapters

Last edited 2019-07-04

Becker, Michael. “Paul and the Evil One.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 127-141. London, UK: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Bernstein, Alan E. “The Ghostly Troop and the Battle Over Death: William of Auvergne (d. 1249) Connects Christian, Old Norse, and Irish Views.” In Rethinking Ghosts in World Religions, edited by Mu-chou Poo, 115-162. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Birman, Patricia. “Sorcery, Territories, and Marginal Resistances in Rio de Janeiro.” In Sorcery in the Black Atlantic, edited by Luis Nicolau Páres and Roger Sansi, 209-231. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Bozóky, Edina. “Mythic Mediation in Healing Incantations.” In Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, edited by Sheila Campbell, Bert Hall, and David Klausner, 84-92. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

* Cusack, Carole M. “Brigit: Goddess, Saint, ‘Holy Woman’, and Bone of Contention.” In On a Panegyrical Note: Studies in Honour of Garry W. Trompf, edited by Victoria Barker and Frances Di Lauro. Sydney, Australia: University of Sydney, 2007.

* DeConick, April D. “What Is Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism?” In Paradise Now: Essays on Early Jewish and Christian Mysticism, edited by April D. DeConick, 1-24. Atlanta, GA: Society for Biblical Literature, 2006.

Dochhorn, Jan. “The Devil in the Gospel of Mark.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich, 98-107. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

* Epstein, Mikhail. “Daniil Andreev and the Russian Mysticism of Femininity.” In The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, edited by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, 325-355. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

* Fanger, Claire. “Complications of Eros: The Song of Songs in John of Morigny’s Liber Florum Celestis Doctrine.” In Hidden Intercourse: Eros and Sexuality in the History of Western Esotericism, edited by Wouter J. Hanegraaff and Jeffrey J. Kripal, 153-174. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

* –. “God’s Occulted Body: On the Hiddenness of Christ in Alan of Lille’s Anticlaudianus.” In Histories of the Hidden God: Concealment and Revelation in Western Gnostic, Esoteric, and Mystical Traditions, edited by April D. DeConick and Grant Adamson, 101-119. New York: Acumen, 2013.

* –. “Introduction: Theurgy, Magic, and Mysticism.” In Invoking Angels: Theurgic Ideas and Practices, Thirteenth to Sixteenth Centuries, edited by Claire Fanger, 1-33. University Park: Penn State University Press, 2012.

* –. “Magic.” In The Oxford Guide to the Historical Reception of Augustine, edited by Karla Pollman and Willemien Otten, 860-865. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

* –. “Necromancy, Theurgy, and Intermediary Beings.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Medieval Studies, edited by Paul Szarmach, 1-5. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

* –. “Sacred and Secular Knowledge Systems in the “Ars Notoria” and the “Flowers of Heavenly Teaching” of John of Morigny.” In Die Enzyklopadie Der Esoterik; Allwissenheitsmythen und universalwissenschaftliche Modelle in der Esoterik der Neuzeit, edited by Andreas Kilcher and Philipp Thiesohn, 157-75. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2010.

* Frankfurter, David. “The Threat of Headless Beings: Constructing the Demonic in Christian Egypt.” In Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits: “Small Gods” at the Margins of Christendom, edited by Michael Ostling, 57-78. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Gaffney, James. “The Relevance of Animal Experimentation to Roman Catholic Ethical Methodology.” In Animal Sacrifices: Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science, edited by Tom Regan, 149-170. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1986.

Gordon, Stephen. “Domestic magic and the walking dead in medieval England: A diachronic approach.” In The Materiality of Magic: An artifactual investigation into ritual practices and popular beliefs, edited by Ceri Houlbrook and Natalie Armitage, 65-84. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2015.

Hakola, Raimo. “The Believing Jews as the Children of the Devil in John 8.44: Similarity As a Treat to Social Identity.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 116-126. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Hand, Wayland D. “Deformity, Disease, and Physical Ailment as Divine Retribution.” In Magical Medicine: The Folkloric Component of Medicine in the Belief, Custom, and Ritual of the Peoples of Europe and America, edited by Wayland D. Hand, 57-67. Berkeley: University of California,

Harrison, Beverly Wildung. “The Power of Anger in the Work of Love: Christian Ethics for Women and Other Strangers.” in Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 212-225. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

* Herzig, Tamar. “Stigmatized Holy Women as Female Christs.” In Archivio italiano per la storia della pietà 23, edited by Gábor Klaniczay, 149-174. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2013.

* Heyward, Carter. “Sexuality, Love, and Justice.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 293-301. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Hutton, Ronald. “Afterword.” In Fairies, Demons, and Nature Spirits: “Small Gods” at the Margins of Christendom, edited by Michael Ostling, 349-356. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

Inclusive Language Lectionary Committee of the National Council of Churches. “Selections from The Inclusive Language Lectionary.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 163-169. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Killen, Patricia O’Connell. “Conclusion: Religious Futures in the None Zone.” In Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone, edited by Patricia O’Connell Killen and Mark Silk, 169-184. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Kornblatt, Judith Deutsch. “Russian Religious Thought and the Jewish Kabbala.” In The Occult in Russian and Soviet Culture, edited by Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal, 75-97. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997.

Koskenniemi, Erkki. “Miracles of the Devil and His Assistants in Early Judaism and Their Influence on the Gospel of Matthew.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 84-97. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Labahn, Michael. “The Dangerous Loser: The Narrative and Rhetorical Function of the Devil as Character in the Book of Revelation.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 156-179. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Li, Shang-jen. “Ghost, Vampire, and Scientific Naturalism: Observation and Evidence in the Supernatural Fiction of Grant Allen, Bram Stoker and Arthur Conan Doyle.” In Rethinking Ghosts in World Religions, edited by Mu-chou Poo, 183-210. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Linzey, Andrew. “The Place of Animals in Creation: A Christian View.” In Animal Sacrifices: Religious Perspectives on the Use of Animals in Science, edited by Tom Regan, 115-148. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1986.

* Macfarlane, Alan. “A Tudor Anthropologist: George Gifford’s Discourse and Dialogue.” In The Damned Art: Essays in the Literature of Witchcraft, edited by Sydney Anglo, 140-155. Abingdon: Routledge, 2011.

* Martín Hernández, Raquel. “Appealing for Justice in Christian Magic.” In Cultures in Contact: Transfer of Knowledge in the Mediterranean Context: Selected Papers, edited by Sofía Torallas Tovar and Juan Pedro Monferrer-Sala, 27-41. Córdoba, Spain: Cordoba Near Eastern Research Unit, 2013.

Matter, E. Ann. “My Sister, My Spouse: Woman-Identified Women in Medieval Christianity.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 51-62. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

McFague, Sallie. “God as Mother.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 139-150. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

* Mildnerová, Kateřina. “’Obscene and diabolic and bloody fetishism’: European conceptualisation of Vodun through the history of Christian missions.” In Knowledge Production In and On Africa, edited by Hana Horáková and Kateřina Werkman, pp. 177-206. Zurich, Switzerland: Lit Verlag, 2016.

Nakashima Brock, Rita. “On Mirrors, Mists, and Murmurs: Toward an Asian American Thealogy.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 235-243. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Newall, Venetia. “Birds and Animals in Icon-Painting Tradition.” In Animals in Folklore, edited by J. R. Porter and W. M. S. Russell, 185-207. Cambridge, Ipswich, and Totowa: D. S. Brewer and Rowman & Littlefield, 1978.

* Ostling, Michael. “Introduction: Where’ve All the Good People Gone?” In Fairies, Demons and Nature Spirits: “Small Gods” at the Margins of Christendom, edited by Michael Ostling, 1-53. New York: Springer, 2017.

Paxton, Frederick S. “Anointing the Sick and the Dying in Christian Antiquity and the Early Medieval West.” In Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, edited by Sheila Campbell, Bert Hall, and David Klausner, 93-102. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Pereira, Luena Nunes. “Families, Churches, the State, and the Child Witch in Angola.” Sorcery in the Black Atlantic, edited by Luis Nicolau Páres and Roger Sansi, 187-208. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Ruether, Rosemary Radford. “Sexism and God-language.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 151-162. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. “In Search of Women’s History.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 29-38. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Shibley, Mark A. “Secular But Spiritual in the Pacific Northwest.” In Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone, edited by Patricia O’Connell Killen and Mark Silk, 139-167. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Soder, Dale E. “Contesting the Soul of an Unlikely Land: Mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Reform and Conservative Jews in the Pacific Northwest.” In Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone, edited by Patricia O’Connell Killen and Mark Silk, 51-78. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2004.

Thistlethwaite, Susan Brooks. “Every Two Minutes: Battered Women and Feminist Interpretation.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 302-313. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Thurén, Lauri. “1 Peter and the Lion.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 142-155. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Tzvetkova-Glaser, Anna. “’Evil Is Not a Nature’: Origen on Evil and the Devil.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 190-202. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Van Fleteren, Frederick. “Augustine and Evil.” In Evil and the Devil, edited by Ida Frölich and Erkki Koskenniemi, 180-189. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

* Vidal, Fernando. “Ghosts of the European Enlightenment.” In Rethinking Ghosts in World Religions, edited by Mu-chou Poo, 163-182. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

Wellman, James K. “The Churching of the Pacific Northwest: The Rise of Sectarian Entrepreneurs.” In Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone, edited by Patricia O’Connell Killen and Mark Silk, 79-105. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, 2004.

* Williams, Delores S. “Womanist Theology: Black Women’s Voices.” In Weaving the Visions: New Patterns in Feminist Spirituality, edited by Judith Plaskow and Carol P. Christ, 179-186. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 1989.

Wortley, John. “Three Not-So-Miraculous Miracles.” In Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, edited by Sheila Campbell, Bert Hall, and David Klausner, 160-168. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

Zier, Mark. “The Healing Power of the Hebrew Tongue: An Example from Late Thirteenth-Century England.” In Health, Disease and Healing in Medieval Culture, edited by Sheila Campbell, Bert Hall, and David Klausner, 103-118. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Italy

Last edited 2018-07-12

Articles

* Herzig, Tamar. “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna.” Renaissance Quarterly 64, no. 4 (2011): 1026-1058.

* --. “Witches, Saints, and Heretics: Heinrich Kramer’s Ties with Italian Women Mystics.” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 1, no. 1 (2006): 24-55.

* Nelide, Romeo, Olivier Gallo, and Giuseppe Tagarelli. “From Disease to Holiness: Religious-based health remedies of Italian folk medicine (XIX-XX century).” Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 11, no. 50 (June 2015).

Chapters

Burke, Peter. “Witchcraft and Magic in Renaissance Italy: Gianfrancesco Pico and His Strix.” In The Damned Art: Essays in the Literature of Witchcraft, edited by Sydney Anglo, 32-52. Abingdon: Routledge, 2011.

* Herzig, Tamar. “Stigmatized Holy Women as Female Christs.” In Archivio italiano per la storia della pietà 23, edited by Gábor Klaniczay, 149-174. Rome: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2013.

Lopasic, Alexander. “Animal Lore and the Evil-eye in Shepherd Sardinia.” In Animals in Folklore, edited by J. R. Porter and W. M. S. Russell, 59-69. Cambridge, Ipswich, and Totowa: D. S. Brewer and Rowman & Littlefield, 1978.

* Vaz da Silva, Francisco. “Fairy-Tale Exchanges.” In Interactions: Centuries of Commerce, Combat, and Creation, Temporary Exhibition Catalogue, edited by Costanza Itzel and Christine Dupont, 177-182. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017.

* Weinstein, Roni. “Kabbalah and Jewish Exorcism in Seventeenth-Century Italian Jewish Communities: The Case of Rabbi Moses Zacuto.” In Spirit Possession in Judaism: Cases and Contexts from the Middle Ages to the Present, edited by Matt Goldish, 237-256. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2003.

Journals

* FOLD&R

4 notes

·

View notes