#ancient epiros

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

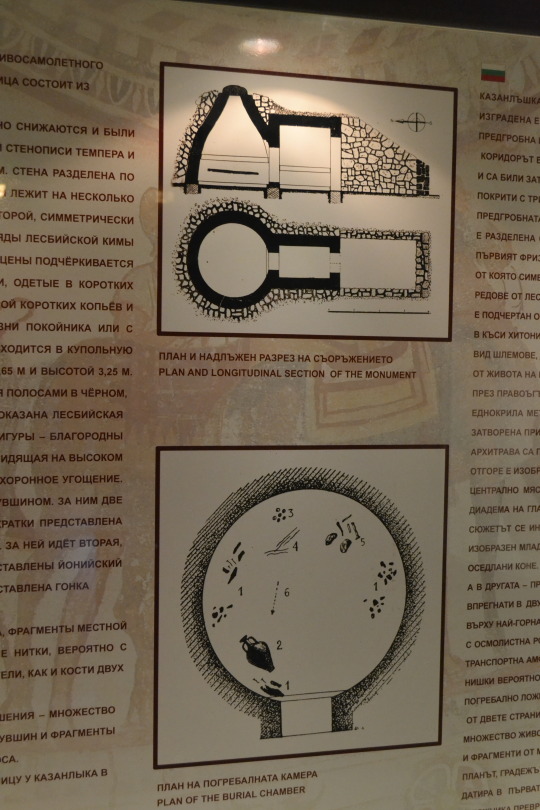

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oak branch with leaves. The sacred oak served as Zeus’ residence in Dodona. 4th-3rd cent. BC

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Aphrodite’s dark side | Epithets

Evidence of a cult of a warrior and dark Aphrodite has been widely studied. Aphrodite had been depicted with armor and prayed to for martial assistance in many places from Syria, to Corinth, Sparta, Argos, the Attika, Kypris, Rome, Naxos, and many, many, other places (but mainly Sparta. Surprising, no?). The cult of a warrior Aphrodite has been suspected to have emerged from Aphrodite’s “ancestral” correspondents like Istar or Astarte, who were both goddesses of sex and war. However, the evidence of a dark face of Aphrodite is there, and it can be too called upon today, even if it wasn't as popular as her holy and hevenly aspects.

Enoplios — weapon bearing

This is an epithet of Aphrodite attested by Plutarch, and is also epigraphically present in the Roman period. In the third century AD a priestess, Ponponia Kallistoneiké, set up a dedication to Artemis Ortheia in Lakonia attesting one of her fellow deities was Aphrodite Enoplios.

Summakhia — ally in war

Pausanias finds a cult of Aphrodite “ally in war” in Arkadia. This is all the comment I could find about it.

Nikephoros — victory bearer

In Argos, according to Pausanias, Aphrodite wore the epithet “victory-bearer”. Icons of Nikephoros and Hoplismene (armed) Aphrodite have been also attested in Syria and Eretria.

Areia — of Ares / war-like

At Sparta mainly, there is a lot of evidence of icons portraying an armed Aphrodite with inscriptions of this epithet. Pausanias tells us of one in a temple behind the Bronze House of Athena. There is another female wearing a peplos, a helmet and a spear, but without the aegis that characterizes Athena, thus many suspect it belongs to an armed Aphrodite.

HOWEVER Leonidas of Tarentum writes in the third century: “Eurotas once said to Kypris (Aphrodite), ‘Either take up arms,

or quit Sparta, the polis mad for arms.’

She, laughing, replied, ‘I shall be ever unarmed.’ She said ‘and I shall dwell in Lakedaimonia.’

Our Kypris is unarmed. Shameful are those tale-tellers who say

that our goddess bears arms!”

BUT from Antipater of Sidon, in the first century, there is a contradiction: “Even Kypris is Spartan. She is not dressed as in other towns

in soft garments;

But in full-force she has a helmet instead of a veil,

instead of golden branches a spear-shaft. For it is not proper for her to be without arms, the consort

of Thracian Enyalios (Ares) and a Lakedaimonian.” And this is not the only record we have of an actual Aphrodite wearing armor in Sparta; Plutarch, Nonnos, Julianus of Egypt and perhaps others tell us about the Spartan tendency to portray Aphrodite wearing an armor; either bow and quiver, spear and helmet, a shield, and even a sword. So perhaps Leonidas was either being sarcastic or lying (or the cult of Aphrodite Areia came after him, of course). This Epithet is thus related to Hoplismene. Julianus tells us that in the sanctuaries of armed Aphrodite girls revere her war-like nature and women give birth to courageous children.

Above all, Pausanias also claims that this Aphrodite was specifically worshipped as a female Ares. This gives us a clue whether this Aphrodite had been syncretized with Ares’ actual femenine counterpart, Enyo (Ares has an epithet related to her: Enyalios)

Androphonos — killer of men

This epithet is representative of her chthonic aspect. There is evidence of a sanctuary of hers and Aphrodite Anosia in Thessaly.

Anosia — the unholy

Aphrodite Anossia apparently was celebrated by women in Thessaly, and she is associated with homosexuality (although this is doubtful). Atheneus tells us a tale of a hetaira (courtesan) named Lais, that flee to Thessaly and fell in love with a man. A band of jealous women beat her to death at Aphrodite’s temple and thus the goddess in this temple became known as Anosia, the Unholy.

Tumborukhos — gravedigger

The Pythagoreans said there are two Aphrodites: one in heaven and one in the Underworld. Therefore she was called Tumborukhos as well.

Epitumbidia — she upon the graves

Couldn't find much information on this epithet either but it must be related to the previous one and representative of her Underworld connections.

Skotia — dark one

This epithet is referent of Aphrodite’s origins as a terrible goddess, and her associations with the planet venus, which were suppressed later by the pop cult (not the association with the planet, tho). This epithet appears to link her to the Erynies and Hekate, and may be referent of a “witch-star” (kakkab kassaptu in ancient Babylonian) nature. The lack of evidence for these type of epithets points at an unpopularity of them. It is important to highlight that some of them could be use against the goddess to give her a bad or “demonic” reputation in the christian sense so I suspect their suppression might have a relation to that.

Melanis — black

Related to the previous epithet. It appears that these “dark” and “unholy” aspects of her are related to the planet venus, as points her Ouraneia (“heavenly”) epithet as well. Venus was known as a “star of lamentation”.

Persephaessa — Queen of the Underworld

This epithet appears to be a syncretism between Aphrodite and Persephone. This is obviously mainly an epithet of Persephone. I could not find evidence for it being used to Aphrodite in the ancient world, just commentaries about it; however, by searching it on google you find an archeological source of it but sadly its written in german, and I have no idea how to read german.

Hoplismene — armed

Pausanias tells us about the sanctuary of Aphrodite at Kythera, saying that there “the goddess herself is an armed xoanon”. The xoanon were archaic wooden icons, and this one, according to Pausanias, was wearing an armor. Quintilian once asked why the Lakedaimonians (Spartans) have an armed Aphrodite, and Plutarch said that they like to portray every god in armor to show that all of them have excellence in warfare. This Aphrodite is present in Corinth as well.

Hegemone — leader (of the troops)

This Epithet of Aphrodite is found in the Athenian Agora, and their border fortress at Rhamnous. The city council also offered dedications to this Aphrodite. There are figures of her engaged in combat with the giant Mimos, and other portrays Aphrodite in a chariot wearing Athena's aegis (although it lacks the gorgon face), along with Poseidon. Hesikhios confirmed this epithet in the sixth century AD saying it applies to Artemis as well. This Aphrodite was also offered sacrifices with Themis and Nemesis, in honor of Aeneas, her son.

Strateia — campaigner

In the Hellenistic period, Aphrodite was called Strateia in western Asia Minor. There is an inscription from Mylasa refers to a priest of Aphrodite Strateia, and a calendar of offerings specifies sacrificing to Aphrodite Strateia along with Arete and Herakles. In Paros and Epiros, strategoi (military generals) are known to have sacrificed to Aphrodite, along with other deities.

Enkheios — spear-bearer

Hesikhios, an author from the 6th century AD, tells us about a terracotta Aphrodite in Cyprus depicted holding a helmet in one hand, a spear, and a shield leaning against one of her legs.

Conclusions

Can we use these aspects of Aphrodite even if they have been exaggerated and weren't actually very much present in ancient cult? Of course. Because worship changes and evolves, if you find one of these epithets symbolic in your life and devotion, you can totally use them and even give them a different dimension. As a witch, for example, I could use the dark and unholy epithets of Aphrodite as a symbol of how witchcraft has been regarded as evil in superstition and a reminder of the persecution women have gone through, and it would be an act of devotion to the Goddess and an act of empowerment. The unpopularity of many of these epithets is also representative of stigma against women and thus using them today could be attested as an act of rebellion.

References

Stephanie L. Boudin, Aphrodite Enoplion

The Other Side of Aphrodite

William Manning, The Double Tradition of Aphrodite’s Birth and her Semitic Origins

Yulia Ustinova, The Supreme Gods of the Bosporan Kingdom: Celestial Aphrodite & the Most High God

Laura McClure, Courtesans at Tables: Gender and Greek Literary Culture in Athenaeus.

John Opsopaus, The Ancient Greek Esoteric Doctrine of the Elements: Water.

Aeon Journal, Aphrodite

#hellenic pagan#theoi#hellenic polytheism#aphroditedeity#hellenic polytheist#hellenic paganism#pagan#greek polytheism#aphrodite worship#aphrodite devotee#aphrodite offerings#greek myth#mythology#greek mythology#hellenismos

728 notes

·

View notes

Photo

EMPIRE OF NICAEA:

THE Empire of Nicaea was a successor state to the Byzantine Empire, or rather a Byzantine Empire in exile lasting from 1204 to 1261 CE. The Empire of Nicaea was founded in the aftermath of the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade and the establishment there of the crusader-run Latin Empire in 1204 CE and was ruled by the Laskarid Dynasty. When the forces of Michael VIII Palaiologos recaptured Constantinople in 1261 CE, the Empire of Nicaea, an empire in exile no more, effectively became the Byzantine Empire once again, until it ultimately fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE.

The sacking of the Byzantine capital of Constantinople shattered the Byzantine Empire. As the Latin crusaders and their Venetian backers established themselves in Europe and in the Aegean islands, three Greek successor states rose up at the peripheries of the empire. The first, and furthest away, was the Empire of Trebizond on the southeastern edge of the Black Sea. Next was the Despotate of Epiros, in modern-day Albania and northwestern Greece. Finally, there was the Empire of Nicaea, centered on the ancient city of Nicaea and controlling northwestern Anatolia.

In addition to the maelstrom of new states were the Bulgarians to the north and the Turks to the east. Battles were fought frequently, alliances were made and broken just as quickly, and who was preeminent in the region was decided by an ever-changing game of thrones. Trebizond was too far away from the center for it to be a serious candidate to reunify Byzantium, and thus it was the Latins, Epirotes, Nicaeans, and the Bulgarians who became the chief contenders for Constantinople.

Read More

473 notes

·

View notes

Text

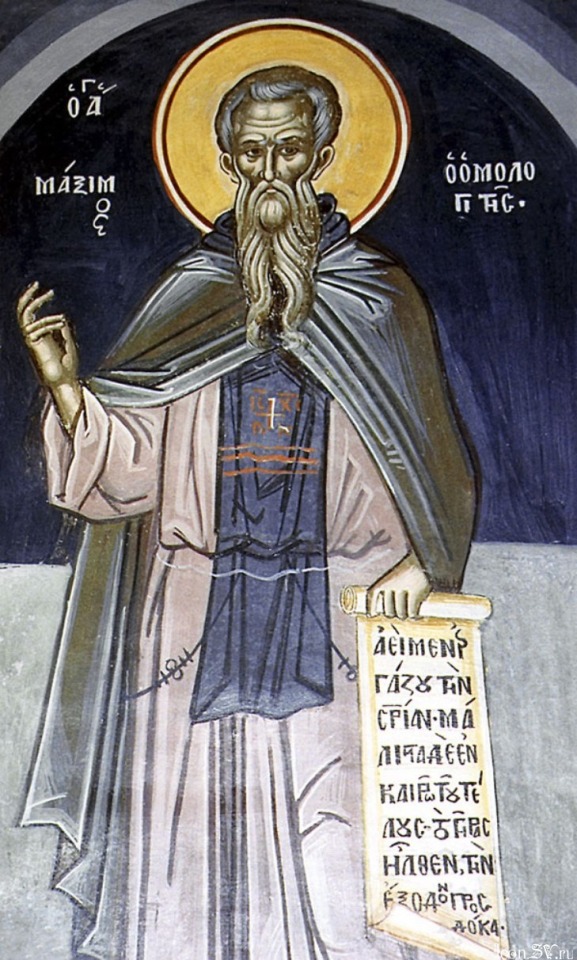

Saints&Reading: Tue., Jan. 21, 2020

Venerable Maximus the Confessor

Saint Maximus the Confessor was born in Constantinople around 580 and raised in a pious Christian family. He received an excellent education, studying philosophy, grammar, and rhetoric. He was well-read in the authors of antiquity and he also mastered philosophy and theology. When Saint Maximus entered into government service, he became first secretary (asekretis) and chief counselor to the emperor Heraclius (611-641), who was impressed by his knowledge and virtuous life.

Saint Maximus soon realized that the emperor and many others had been corrupted by the Monothelite heresy, which was spreading rapidly through the East. He resigned from his duties at court, and went to the Chrysopolis monastery (at Skutari on the opposite shore of the Bosphorus), where he received monastic tonsure. Because of his humility and wisdom, he soon won the love of the brethren and was chosen igumen of the monastery after a few years. Even in this position, he remained a simple monk.

In 638, the emperor Heraclius and Patriarch Sergius tried to minimize the importance of differences in belief, and they issued an edict, the “Ekthesis” (“Ekthesis tes pisteos” or “Exposition of Faith),” which decreed that everyone must accept the teaching of one will in the two natures of the Savior. In defending Orthodoxy against the “Ekthesis,” Saint Maximus spoke to people in various occupations and positions, and these conversations were successful. Not only the clergy and the bishops, but also the people and the secular officials felt some sort of invisible attraction to him, as we read in his Life.

When Saint Maximus saw what turmoil this heresy caused in Constantinople and in the East, he decided to leave his monstery and seek refuge in the West, where Monothelitism had been completely rejected. On the way, he visited the bishops of Africa, strengthening them in Orthodoxy, and encouraging them not to be deceived by the cunning arguments of the heretics...keep reading

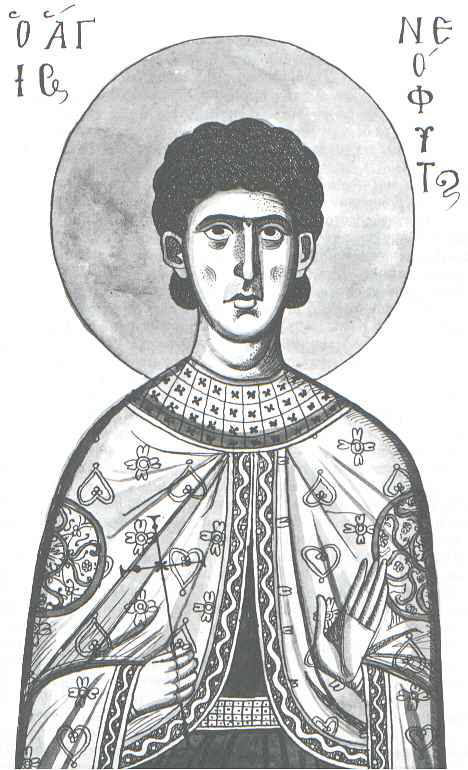

Martyr Neophytus

The Holy Martyr Neophytus, a native of the city of Nicea in Bithynia, was raised by his parents in strict Christian piety. For his virtue, temperance and unceasing prayer, it pleased God to glorify Saint Neophytus with the gift of wonderworking, while the saint was still just a child!

Like Moses, the holy youth brought forth water from a stone of the city wall and gave this water to those who were thirsty. In answer to the prayer of Saint Neophytus’ mother, asking that God’s will concerning her son might be revealed to her, a white dove miraculously appeared and told of the path he would follow. The saint was led forth from his parental home by this dove and brought to a cave on Mt. Olympus, which served as a lion’s den. It is said that he chased the lion from the cave so that he could live there himself. The saint remained there from the age of nine until he was fifteen, leaving it only once to bury his parents and distribute their substance to the poor.

During the persecution by Diocletian (284-305), he went to Nicea and boldly began to denounce the impiety of the pagan faith. The enraged persecutors suspended the saint from a tree, they whipped him with ox thongs, and scraped his body with iron claws. Then they threw him into a red-hot oven, but the holy martyr remained unharmed, spending three days and three nights in it. The torturers, not knowing what else to do with him, decided to kill him. One of the pagans ran him through with a sword (some say it was a spear), and the saint departed to the Lord at the age of sixteen...From Orthodox Church of America_ OCA

Venerable Maxime the Greek

Saint Maximus the Greek was the son of a rich Greek dignitary in the city of Arta (Epiros), and he received a splendid education. In his youth he travelled widely and he studied languages and sciences (i.e. intellectual disciplines) in Europe, spending time in Paris, Florence, and Venice.

Upon returning to his native land, he went to Athos and became a monk at the Vatopedi monastery. And with enthusiasm he studied ancient manuscripts left on Athos by the Byzantine Emperors Andronicus Paleologos and John Kantakuzenos (who became monks).

During this period the Moscow Great Prince Basil III (1505-1533) wanted to make an inventory of the Greek manuscripts and books of his mother, Sophia Paleologina, and he asked the Protos of the Holy Mountain, Igumen Simeon, to send him a translator. Saint Maximus was chosen to go to Moscow, for he had been brought up on secular and ecclesiastical books from his youth. Upon his arrival, he was asked to translate patristic and liturgical books into Slavonic, starting with the Annotated Psalter...keep reading From Orthodox Church of America

James 3:1-10 NKJV

The Untamable Tongue

3 My brethren, let not many of you become teachers, knowing that we shall receive a stricter judgment. 2 For we all stumble in many things. If anyone does not stumble in word, he is a [a]perfect man, able also to bridle the whole body. 3 [b]Indeed, we put bits in horses’ mouths that they may obey us, and we turn their whole body. 4 Look also at ships: although they are so large and are driven by fierce winds, they are turned by a very small rudder wherever the pilot desires. 5 Even so the tongue is a little member and boasts great things.

See how great a forest a little fire kindles! 6 And the tongue is a fire, a world of [c]iniquity. The tongue is so set among our members that it defiles the whole body, and sets on fire the course of [d]nature; and it is set on fire by [e]hell. 7 For every kind of beast and bird, of reptile and creature of the sea, is tamed and has been tamed by mankind. 8 But no man can tame the tongue. It is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. 9 With it we bless our God and Father, and with it we curse men, who have been made in the [f]similitude of God. 10 Out of the same mouth proceed blessing and cursing. My brethren, these things ought not to be so.

Footnotes:

James 3:2 mature

James 3:3 NU Now if

James 3:6 unrighteousness

James 3:6 existence

James 3:6 Gr. Gehenna

James 3:9 likeness

Mark 11:11-23 NKJV

11 And Jesus went into Jerusalem and into the temple. So when He had looked around at all things, as the hour was already late, He went out to Bethany with the twelve.

The Fig Tree Withered

12 Now the next day, when they had come out from Bethany, He was hungry. 13 And seeing from afar a fig tree having leaves, He went to see if perhaps He would find something on it. When He came to it, He found nothing but leaves, for it was not the season for figs. 14 In response Jesus said to it, “Let no one eat fruit from you ever again.”

And His disciples heard it.

Jesus Cleanses the Temple

15 So they came to Jerusalem. Then Jesus went into the temple and began to drive out those who bought and sold in the temple, and overturned the tables of the money changers and the seats of those who sold doves. 16 And He would not allow anyone to carry wares through the temple. 17 Then He taught, saying to them, “Is it not written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it a ‘den of thieves.’ ”

18 And the scribes and chief priests heard it and sought how they might destroy Him; for they feared Him, because all the people were astonished at His teaching. 19 When evening had come, He went out of the city.

The Lesson of the Withered Fig Tree

20 Now in the morning, as they passed by, they saw the fig tree dried up from the roots. 21 And Peter, remembering, said to Him, “Rabbi, look! The fig tree which You cursed has withered away.”

22 So Jesus answered and said to them, “Have faith in God. 23 For assuredly, I say to you, whoever says to this mountain, ‘Be removed and be cast into the sea,’ and does not doubt in his heart, but believes that those things he says will be done, he will have whatever he says.

New King James Version (NKJV) Scripture taken from the New King James Version®. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. All rights reserved. from Biblegateway

0 notes

Text

KDHX, “Music from the Hills,” 26 March 2017

As I am growing (baby steps) as a Celtic rhythm guitar player, I have been thinking more about Breton music. When I got a two week stint on this show, I knew I wanted to go to Brittany. Next week will look at the Albania/Macedonia/Epiros Greece nexus.

My plan was to trace my earliest exposures to this captivating music, show some of the basic elements (singing, bombarde, box, harp), use the Chieftains medley as a synthesis and a breather (I had also done the previous show), show the folk revival and folk rock (some quite raucous) bands that build on the tradition, and then note the ways in which Breton musicians have interacted with Galifuna and Balkan traditions.

Here’s how it played out:

04:02PM-04:07PM (5:37) Celtic Fiddle Festival “Teolena / Marche de Roskonval / Sandizan” from ENCORE (2006) on Green Linnet

04:07PM-04:11PM (3:48) Kornog “Laridé / An Dro” from Music from Brittany (2006) on Green Linnet

04:11PM-04:16PM (5:20) Ad Vielle Qui Pourra “An dro pitaouer / An dro evit jakeza” from New French Folk Music on Green Linnet

04:16PM-04:21PM (4:14) Dan Ar Baz, L'Heritage Des Celtes, Gilles Servat, Alan Stivell, Tri Yann, Armens “Tri Martold” from Bretagnes À Bercy [Disc 2] on Sony

04:23PM-04:26PM (3:23) Fransou Menez & Loeiz Ropars “Gavotten ar menez (Ton Doub)” from Musiques , chants et danses de Bretagne (Celtic music from Brittany - Keltia Musique) on Keltia Musique

04:26PM-04:29PM (3:14) John Skelton “Son Ar Skorff” from One At A Time (1993) on Pan Records

04:29PM-04:31PM (2:06) Dominig Bouchaud “Al leanez (La religieuse)” from Vibrations (Harpe Celtique) on Keltia Musique

04:31PM-04:37PM (5:30) Christian Desnos “Suite de ronds de loudeac” from Diatonic Accordion from Brittany (Celtic Instrumentals Music from Brittany -Keltia Musique - Bretagne) on Keltia Musique

04:39PM-04:59PM (20:11) The Chieftains “Celtic Wedding (A Medley of Song and Dance Describing the Famous Ancient Breton Ceremony)” from Celtic Wedding on BMG

05:01PM-05:06PM (5:10) Skolovan “Gavotte pourlette” from Skolovan on ADIK

05:06PM-05:12PM (5:39) Lors Landat Ha Thomas Moisson “M'em Es Choéjet Un Dous - Ridée” from En Public (2015) on Lenn Production

05:12PM-05:16PM (3:46) Storvan “Kas ha barh” from Digor'n abadenn on Keltia Musique

05:16PM-05:19PM (3:37) Dan Ar Braz et Bagad Kemper “La Costa de Galicia” from Dan Ar Braz et l'Heritage des Celtes - "Finisterres" (1997) on St.George (now Sony)

05:20PM-05:23PM (2:41) Armens “Ar-Men” from Bretagnes a Bercy on Sony

05:23PM-05:28PM (4:33) Dan Ar Braz et Bagad Kemper “Evit ar Braz” from Dan Ar Braz et l'Heritage des Celtes - "Finisterres" (1997) on St.George (now Sony)

05:28PM-05:32PM (4:04) Tri Yann “Fransozig (Live)” from Le concert des 40 ans de Tri Yann (Live) on Marzelle

05:32PM-05:38PM (6:14) The House Band “War Hent Berc'hed / Le Bon Chien / Derobee de Broons / Derobee” from October Song on Green Linnet

05:40PM-05:45PM (5:05) Breizh Amerika & Garifuna language musicians “An Teir Seienn - d'an Hanter-dro / D'ar ride / Yalifu - Hüngühüngü” from Breizh Amerika Collective - Asambles.Uwarani.Together (2015) on self

05:45PM-05:49PM (4:20) The House Band “An Dro D'Ogham/Au Place De Serbie” from Word of Mouth (1988) on Green Linnet

05:49PM-05:54PM (4:35) Christian Lemaitrre and Jean-Pierre Cornoux “Melodie et danse du Thrace” from Affinites on Rouge

05:52PM-05:56PM (3:48) Trio Erik Marchand “Madam O” from An Tri Breur - Chants Du Centre Bretagne (Songs From Central Brittany) (1991) on Silex

05:56PM-06:00PM (4:27) Celtic Fiddle Festival “Two Andros>Andro psg (partial)” from ENCORE (2006) on Green Linnet

0 notes

Note

Hello! Dropping by to say that I’ve been loving how much attention DwtL has been getting and I’m devouring the new Cambridge Companion edition on ATG lol. Super interesting stuff, and it’s explained in a way that makes sense to someone like me who has no official humanities research background—and thank you for always entertaining our questions :)

A little unrelated to ATG, and more so an overall question. Something that has always intrigued me was the dichotomy between revered goddesses in Ancient Greek religious practices, and the way the society treated its own women. (Athena = goddess of intelligence, among others = super derogatory attitudes toward women’s intellectual capacity?) Not limited to Greece only, of course: so many ancient cultures worshipped female deities, but suppressed their own women. I’m wondering if you had any theories for why this phenomenon persisted, because it’s been something I was mystified by for a while now.

First, thanks. I'm glad that more people seem to be discovering the novels, and apparently liking them well enough. And YES, the Companion is a great new addition. I'm especially pleased that Cambridge decided to price it such that more people can actually afford to buy it, besides academic libraries. That was one big problem with the prior one (2003) from Brill.

Down the decades (centuries) a lot of folks have asked your question! It’s one reason I point out that the status of goddesses (and heroines) shouldn’t be taken as indicative of the actual power or even agency of women in ancient Greece—although that also varied from place to place.

Time for my periodic reminder: ancient Greece wasn’t a single country. It was a series of independent city-states. Each of those belonged to one of three major (and a couple minor) linguistic dialects with their own unique social and religious traditions.

E.g., there’s not really such a thing as “ancient Greece.” That was a post-Persian War construct that owed more to propaganda than reality.* “The Greeks” fought each other more than they fought anybody else until quite late.

It’s very easy, especially at an intro-level, to accidentally conflate Athens with ancient Greece. Partly, it’s an evidence problem. Most of our evidence about ancient Greece comes from ancient Athens.

When it comes to women, this results in a particularly negative picture of female agency in pre-Hellenistic/pre-Roman Greece. Women in Athens were particularly disempowered, both (te) legally and (kai) actually. Let me explain that last.

Legal power = what a society ostensibly allows

Agency = what actually prevails, positively or negatively, in contrast to actual power

It’s important to recognize this distinction. Down the millennia, women have got rather good at circumventing legal restrictions via “subversive” power. We all know this. It’s why someone like Olympias got slammed by the likes of Plutarch. She didn’t “know her place.” Never mind that her legal “place” in Epiros versus Macedon versus various southern Greek city-states varied. Women in ancient Greece often found ways to exercise power outside legal bounds. Rather than “illegal,” we should refer to this as “alegal.”

Yet supposed legal power can be deceptive the other way too: it my imply more power than women actually have…just ask any rape survivor who has to testify in court in the face her reputation being smeared by the defense.

So, all that laid out as a basis, let’s look at mortal women vs. immortals.

Next point of definition: immortals are immortals not because they’re “good” or should be imitated but because 1) they don’t die (although some can be killed), and 2) they’re more powerful than mortals. They don’t play by the same rules and aren’t held to the same standards of “proper” behavior. Afterall, Zeus married two of his own sisters (Demeter, then Hera).

Religious festivals were also known for allowing “transgressive” behavior normally restricted in regular/normal/profane time. So, for instance, during the annual Thesmophoria, married women left their families to camp out together and form their own “city-state,” even electing temporary magistrates to run this 3-day city-of-women within the larger polis. Young girls on the cusp of their periods in Attika went camping to play the bear for Artemis at Brauron (and apparently other places). Etc.

Religious festival served an important function in ancient Greece, providing much-needed interruptions to the drudgery of daily life. In antiquity, relatively few cultures had regular “breaks” like weekends. Rather, religious festivals provided this function; these might range from a half-day break to something a week long or more. Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that divine behavior was considered exceptional. The sacred (numinous) was sharply divided from the profane (normal).

Additionally, it’s no surprise if farming societies, or any society with a strong connection to the earth, should develop powerful goddesses. There are, of course, male fertility deities, but Mother Nature/Mother Earth is nearly universal. The only religion I can think of where the earth is male and the sky is female is ancient Egypt. (Recall Isis’s starry robe!) There are probably more, but it’s not exactly typical.

I’m not getting into the much-fraught debate about why women’s power in most historical societies has been less than men’s. Theories breed like hydra heads. But it is pretty well recognized that in societies where women had some control over their fertility (when to have babies, and how many), as well as independent control over their finances, their social status was higher. Beyond that, the best we can say is that which societies developed higher status for women depended on a constellation of factors.

Ironically—and perhaps counterintuitively—these factors didn’t involve the relative importance of female deities. Perhaps for reasons outlined above. Not all societies saw their divinities as living in ways mortals should imitate.

In her groundbreaking Goddesses, Whores, Wives, and Slaves—one of the first books to really look at the role of women in ancient Greece—Sarah Pomeroy herself noted the problem with the status of goddesses versus the status of flesh-and-blood women. Discussion of women in ancient Greece has grown more nuanced since. For a great little overview, let me recommend Lin Foxhall’s Studying Gender in Classical Antiquity (2013). I love this book because it looks at more than just texts (which is Pomeroy’s more traditional, Classical approach). Foxhall uses a lot of archaeology, which, when it comes to women (and slaves, for that matter) really fleshes out our perspectives. There’s also the more recent Exploring Gender Diversity in the Ancient World (Allison Surtees, Jennifer Dyer eds., 2020). It’s one of those great “collections” where you get the advantage of multiple voices contributing. It’s more about gender variance than women, but I quite like it. Last, let me also recommend Helen Morales’ Antigone Rising, which looks at Classical myth today, or reception studies. Morales is one of those Classicists who (like me) thinks it important to engage with the wider public, but she’s rather more prominent and respected. 😉

So, there’s some good, reliable literature to get you off the ground too, most intended for a non-specialist audience. (I’d tackle the first two and last before trying the collection, which is more specialized with some linguistic discussions, etc.)

——-

* Even in the Greco-Persian Wars, more Greek city-states didn’t fight the Persians than did!

#asks#Greek women vs Greek goddesses#women in ancient Greece#why is the status of Greek women so low when they also worshiped goddesses?#ancient Greece#Classics#religion and the status of women

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

What was Alexander's relationship, if there was enough interaction that he would remember, with Lanike like (I don't know if that's how her name was spelled)? Would it be different or similar, or nothing at all, to what someone feels for their mother? Was Alexander the type to form lasting bonds with people? Mary Renault wrote him as affectionate and loving with people, but I honestly don't really know what to believe when I read about him. Things are usually conflicting, or as I've come to realize, made up entirely.

Thanks!

There are really two questions here, so let me deal with the larger one first: Alexander’s ability to feel real affection.

I don’t think his reputation for forming intense bonds with people is false, or even much exaggerated. Nor is his tendency to fly off the handle in a rage. These are, really, two sides of one coin.*

In general, the Greeks were (and still are) more emotionally expressive than most Anglophone societies. Furthermore, in ancient Greece, to help one’s friends and hurt one’s enemies was considered model ethical behavior. Both Alexander and his father Philip were actively competitive in displays of generosity. The times they act uncharacteristically like a bull in a China shop are part of constructed narratives meant to make them conform to ideas about barbarian tyrants, particularly in the hands of later Roman authors such as Curtius, but also Plutarch of the Second Sophistic. Or with Philip, Demosthenes’ and Theopompos’ need to portray Philip as a despot who Tyche (Fortune) allowed to beat the Truly Hellenic Athens/South Greece. So, when they seem to act weirdly against their own diplomatic interests, perhaps consider the source. (Literally. Consider the source, and when he was writing.)

Macedonia, in contrast to (some of) the cities to the south such as Athens who had sumptuary laws, was a gift-exchange society. For that matter, so was earlier (Archaic and prior) Greece, as well as other city-states (not-Athens). One achieved more honor and fame for how much one gave away, not necessarily how much one had.

Generosity made the Man. It also made the Woman. An important social function of the wives of Macedonian kings, as well as of other wealthy citizens in Macedonia and elsewhere (including into the Hellenistic and later Roman eras), was to give donations to this or that city project, temple, building, etc.

Eurgetism.

By all accounts, Alexander took real joy in giving things away. Sometimes lavishly. This cemented his status as The Bestest King in the Whole Wide World. Certainly the richest. Near the end of his life, he spent ridiculous amounts of money every evening just on royal suppers.

ALL of this is about Display as Status. As well as rules of hospitality.

I explain all that to help give some cultural context to Alexander’s fabled generosity. Yes, I think it was very real. It was also absolutely culturally expected of him.

So his reputation for honoring friends and allies in lavish ways shouldn’t be unexpected. He also appears to have been affectionate and even thoughtful towards those he considered friends and allies. Ergo, I think his affection for his childhood nurse would be quite genuine.

Now to the second question, which involves the role a nurse had in an infant’s life…. In cultures that strongly emphasize the nuclear family, and for those of us who didn’t grow up wealthy enough to have “house staff,” it may feel unclear how to understand the role of a wetnurse. So let’s quickly frame that role in traditional Greek (and Macedonian) society.

Wetnurses were typically either slave women or from poor families who needed to supplement income. That Alexander had a noblewoman as a wetnurse was extraordinary. (Just as it was to have a prince [of Epiros] as a lesson-master.)

Ancient Greece had two “house-slave” categories devoted to the caretaking of children: the wet-nurse and the paidogogos (pedagogue). The former was, for wealthier families, the caretaker of children of both genders while the mother saw to the business of running an estate (or at least a larger farm). The paidogogos, however, was exclusively for male children old enough to leave the home (go to school, to the gymnasion, etc.), largely as a baby-sitter, to keep the kid out of trouble. There appears to have been genuine affection between some children and their slave caretakers. But also examples of wetnurses and paidogogoi who just didn’t give two figs. No doubt this reflected how they were, themselves, treated by their owners. (And that could devolve into a complicated discussion about slavery in antiquity, but… go and read my friend and colleague, Peter Hunt’s book, Ancient Greek and Roman Slavery.)

In Alexander’s case, these individuals weren’t slaves, which simplified (and complicated) his relationships with them. On the one hand, it removed the utter dependence/lack of autonomy any slave (however well-treated) would have experienced. But—as with the institution of the Pages, who were nobility doing slave work as body-servants to the king—it involved the “reduction” of elites to unfree occupations. That hovered between honor and humiliation. It’s an honor because he's royalty, but….

For most of us, who, again, didn’t grow up wealthy, having “house staff” is unfamiliar. Ergo, the complicated dynamics of such is equally unfamiliar. That said, I think seeing the wetnurse as another mother may not be the best analogy (except in cases where the mother might really have been distant/absent).

I’d compare it to AUNTIES. A lot of societies have aunties (both literal and honorary) who play super-important roles in children’s lives. Those aunties may even have children of their own (cousins, again literal and honorary), but that doesn’t lessen their impact on their nieces and nephews. Or how they can be loved in a way similar to, but different than a mother. (Or how they can be exasperating in a way similar to, but different than a mother!)

So, for many of us, probably the best analogy for Lanike’s role in Alexander’s life would be a beloved auntie.

* This is also why I find attempts to paint him as a psychopath/sociopath or megalomaniac (e.g., narcissistic personality disorder) unfounded. A characteristic of both is inability to empathize or have strong emotions for people outside the self (and occasionally a very few select others). If he were any of those, he’d manipulate the hell out of people, but not feel much himself. His affections and rages seem far too spontaneous for that.

#asks#Alexander the Great#wetnurses in Greek society#generosity in ancient Greek society#Lanike#Alexander the Great's affection for friends and family#Classics#ancient history#ancient Greek family ties

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Kind of related to the ask on Cleopatra, and even your one way earlier on Krateros… What do you think Alexander would’ve been like if he weren’t an Argead, and instead fated to be a Marshal for whoever else was meant for the throne? Do you think he would’ve been rebellious? Or cutthroat and ambitious like Krateros? Or more-so disciplined and loyal? I kind of see him as a combination of all three because I don’t peg Alexander for someone who can be contained, lol.

To answer this, we must keep in mind that, for the ancient Greeks, belief in divine parentage for certain family lines was very real. A given family and/or person ruled due to their descent. The heroes in Homer had divine parents/grandparents/great-grandparents. This notion continued into the Archaic period with oligarchic city-states ruled by hoi aristoi: “the best men.” (Yes, our word “aristocrat” comes from that.) Many of these wealthy families claimed divine ancestry; that’s why they were “best.”

In the south, this began to break down from the 5th century into the 4th. But not in Macedonia, Thessaly, or Epiros. In fact, even by Alexander’s day, many Greek poleis remained oligarchies, not democracies. And in democracies, “equality” was reserved for a select group: adult free male citizens. Competition (agonía) was how to prove personal excellence (aretȇ), and thereby gain fame (timȇ) and glory (kléos). All this was still regarded as the favor of the gods.

Alexander believed himself destined for great things because he was raised to believe that, as a result of his birth. Pop history sometimes presents only Olympias as encouraging his “special” status. But Philip also inculcated in Alexander a belief he was unique. He (and Olympias) got Alexander an Epirote prince as a lesson-master, then Aristotle as a personal tutor. Philip made Alexander regent at 16 and general at 18. That’s serious “fast track.” Alexander didn’t earn these promotions in the usual way; he was literally born to them.

If Alexander hadn’t been an Argead, that would have impacted his sense of his place in the world no less than it did because he was an Argead. What he might have reasonably expected his life path to take would have depended heavily on what strata of society he was born into.

Were he a commoner, in the Macedonian military system, his ambitions might have peaked at decadarch/dekadarchos (leader of a file). Higher officer positions were reserved for aristocrats through Philip’s reign. With Alexander himself, after Gaugamela, things started to change for the infantry, at least below the highest levels (but not in the cavalry, as owning a horse itself was an elite marker). Under Philip, skilled infantry might be tagged for the Pezhetairoi (who became the Hypaspists under ATG). But Alexander himself wouldn’t have qualified because those slots weren’t just for the best infantrymen, but the LARGEST ones. (In infantry combat, being large in frame was a distinct advantage.) So as a commoner, Alexander’s options would have been severely limited.

Things would have got more interesting if he’d been born into the ranks of the Hetairoi families, especially if from the Upper Macedonian cantons.

Lower cantons were Macedonian way back. If born into those, he (and his parents) would have been jockeying for a position as syntrophos (companion) of a prince. Then, he’d try to impress that prince and gain a position as close to him as possible, which could result in becoming a taxiarch/taxiarchos or ilarch/ilarchos in the infantry or cavalry. But he’d better pick the RIGHT prince, as if his wound up failing to secure the kingship, he might die, or at least fall under heavy suspicion that could permanently curtain real advancement.

That was the usual expectation for Lower Macedonian elites. Place as a Hetairos of the king and, if proven worthy in combat, relatively high military command. Yes, like Krateros. But hot-headedness could curtail advancement, as apparently happened to Meleagros, who started out well but never advanced far. The higher one rose, the more one became a potential target: witness Philotas, and later Perdikkas. In contrast, Hephaistion was Teflon (until his death). Yet Hephaistion’s status rested entirely on his importance to Alexander. And he probably wasn’t Macedonian anyway; nor was Perdikkas from Lower Macedonia, for that matter.

The northern cantons were semi-independent to fully autonomous earlier in Macedonian history. Their rulers also wore the title “basileus” (king); we just tend to translate it as “prince” to acknowledge they became subservient to Pella/Aigai. Philip incorporated them early in his reign, and I think there’s a tendency to overlook lingering resentment (and rebellion) even in Philip’s latter years. Philip’s mother was from Lynkestis, and his first wife (Phila) from Elimeia. Those marriages (his father’s and his) were political, not love matches.

Similarly, Oretis was independent, and originally more connected to Epiros. Note that Perdikkas, son of Orontes, was commanding entire battalions when he, too, was comparatively young. Like Alexander, he was “born” to it. Carol King has a very interesting chapter on him in the upcoming collection I’m editing, one that makes several excellent points about how later Successors really did a number on Perdikkas’s reputation (and not just Ptolemy).

If Alexander had been born into one of these royal families from the upper cantons, quasi-rebellious attitudes might be more likely. Much would depend on how he wanted to position himself. Harpalos, Perdikkas, Leonnatos, Ptolemy…all were from upper or at least middle cantons. They faired well. For that matter, Parmenion himself may have been from an upper canton and decided to throw in his hat with Philip.

By Philip’s day, trying to be independent of Pella was not a wise political choice, but if one came from a royal family previously independent, we can see why that might be seductive. Lower Macedonia had always been the larger/stronger kingdom. But prior to Philip, Lynkestis and Elimeia both had histories of conflict with Macedonia, and of supporting alternate claimants for the Macedonian throne. At one point in (I think?) the Peloponnesian War, Elimeia was singled out as having the best cavalry in the north. Aiani, the main capital, had long ties WEST to Corinthian trade (and Epirote ports). It was a powerful kingdom in the Archaic/early Classical era, after which, it faded.

So, these places had proud histories. If Alexander had been born in Aiani, would he have been willing to submit to Philip’s heir? Maybe not. But realistically, could he have resisted? That’s more dubious. By then, Elimeia just didn’t have the resources in men and finances.

I hope this gives some insight into how much one’s social rank influenced how one learned to think about one’s self. Also, it gives some insight into political factions in Macedonia itself. As noted, I believe we fail to recognize just how much influence Philip had in uniting Lower and Upper Macedonia. Nor how resentment may have lingered for decades. I play with this in Dancing with the Lion: Rise, as I do think it had an impact on Philip’s assassination.

(Spoiler!)

Philips discussion with his son in the Rise, and his “counter-plot” (that goes awry) may be my own invention, but it’s based in what I believe were very real lingering resentments, 20+ years into Philip’s rule.

#asks#Alexander the Great#Alexander alternate history#ancient Macedonia#ancient Macedonian politics#Upper Macedonia#Lower Macedonia#Macedonian internal politics#Philip II of Macedon#ancient history#Classics

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just saw the cat publication and it came to my attention that Polyxena/ Myrtatle/Olympia/ Stratonike and Hephaistion had similar personalities I need to know more!

I should be more forthright. This is my reading of them, for the novels, as we don’t know a lot about the real Hephaistion, personality-wise.

In Dancing with the Lion: Becoming, part of why Alexandros latches onto Hephaistion so quickly owes to the fact he feels vaguely familiar. I don’t mean that in a creepy way, and specify as much because Oliver Stone has said, in interviews, that he cast Rosario Dawson as Roxana because she resembled Angelina Jolie in certain respects, and he wanted the Oedipal Thing.

I manifestly do NOT, nor do I think it applicable (see this post for an explanation of why).

Even so, we are drawn to people who remind us of those we love (and understand).

My Hephaistion and Myrtalē are both FIERCE in their devotion to those they love. They’re also intense and so, a bit scary. And they both have a jealous bone. Also like Hephaistion, Myrtalē as I envision her got on very well with and cares deeply about her siblings. I think readers can pick up a sense of that between the sisters at least, when Myrtalē is exiled in Epiros in DwtL: Rise.

I also see Myrtalē and Hephaistion as having similar styles of psychological manipulation (of those they perceive to be enemies). That was what I had a little fun with in the short story, “Two Scorpions.” Myrtalē/Olympias goes after him because she sees him as a threat to Alexandros. He tries to fight back, but is essentially dealing with an older, more experienced version of himself. So, we see her drop him to the (virtual) mat a few times. In the end, he “kinda” wins, but only because he walks out before she can get in a retort. LOL The confrontation is written in his POV, but I hope it’s still evident she is (overall) getting the better of him.

In “Two Scorpions,” both act out of love for Alexandros, and what they perceive as the best for him. Myrtalē/Olympias isn’t jealous of nor “hates” Hephaistion. She tells him, quite bluntly, that she didn’t really have much of an opinion about him until he made himself Alexandros’s lover. And she explains why (she perceives) that to be dangerous. She’s brutal, but she’s completely transparent—and knows how to use that honesty to undermine her opponent, just as she has a knack for guessing her opponent’s weak spots. Hephaistion often employs the same tactics. And both pair that with an apparently unflappable façade. But she’s better at it than he is. 😉 Because she’s almost fifteen years older than he is.

Too often, Olympias in literature is portrayed as irrational, vindictive, and jealous. But that’s an ancient Greek male projection of what drives “meddling” women who get above themselves by trying to “do” politics. How dare they?!

I hope that explains why I, at least, see the two as quite similar, at least in the novels. Again, we don’t know enough about the real Hephaistion to say what he was like, although I did build my fictional character on what seemed to me a feasible extrapolation from the source material.

#asks#Hephaistion#Hephaestion#Olympias#Myrtale#Two Scorpions#historical fiction#ancient Greek historical fiction#DwtL

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

hello dr. Reams, I wanted to ask why Alexandros is associated with Achilles and not with Heracles?

Actually, that's a MODERN thing. I’ve 'complained' about it before HERE, and more extensively with better discussion HERE, both in responses to asks.

If you read the ancient sources, Herakles trumps every other deity or hero in terms of association with Alexander, and in all sources. Only in Plutarch is it more even. But in others, such as Arrian, Diodoros, and Curtius, Herakles is by far the most mentioned, followed by Dionysos and Zeus, then Athena and Ammon, and only then Achilles. (Yes, I’ve counted.)

Alexander did use Achilles as a model now and then, but it seems to have been specific and localized. So, when he landed at Troy to start his grand campaign against “Asia,” he styled himself after the great Greek mythic warrior: a new Achilles. He did sacrifice at Achilles’ “tomb” (a cenotaph), but also went to Athena’s temple, and even sacrificed to Priam, so he wouldn’t be upset. Ha. In short, it was a Grand Tour of the tourist attractions at ancient Troy.

The connection of Hephaistion to Patroklos is even looser and may have been a later Roman fabrication rather than anything they claimed in their lifetimes, although I’m inclined to think Alexander did make the allusion…but specific and localized as well, just as he did with himself to Achilles. So, at Troy, and again after Hephaistion’s death. Later authors seized on it and made more of it. My colleague and friend Sabine Müller, who has probably published as much about Hephaistion as I have, disagrees, but largely because she thinks the entire childhood friendship is a later invention, and Hephaistion didn’t join the campaign until Alexander was already in Asia or about to land there. (She agrees with my assessment that he had Athenian ancestry, but she’s proposed that he came from Athens to join Alexander as an adult. Her arguments are not without merit; I just don’t happen to agree.)

In any case, I did make use of the Achilles/Patroklos allusion in Dancing with the Lion: Becoming, but did so because it solved a “problem” for Alexandros. You’ll notice mentions of Achilles or Patroklos are rather lacking in Rise. 😉 That wasn’t accidental.

So yes, Herakles was very much ALEXANDER’S first choice as heroic model, not least because he believed himself descended from him. And while he was also supposedly descended from Achilles, that was through Mamma, and he wasn’t king of Epiros. He was king of Macedon, so he needed those Heraklean connections to be a proper Temenid.

This was also reflected in iconography in the ancient world. You’ll not infrequently see a Herakles statue that has a distinctive “Alexander-ish” cast. (see above) Is it Alexander as Herakles, or Herakles-Alexander? Also there are some Alexander as Helios (the sun god, see below), and even one of Alexander as Pan. Sometimes Alexander is “heroized” and shown naked, but that doesn’t make him Achilles. So the association of Alexander with Herakles was continued in antiquity, but we just don’t see the same for Alexander and Achilles. The references are literary, and mostly late (after ATG’s own lifetime sometimes by a few centuries).

The Alexander-Achilles connection really is modern. Some of it rests on the romanticism of the Achilles-Patroklos … Alexander-Hephaistion parallel, but not all of it. I’m not sure Alexander would necessarily have objected. As noted, he made the connection too. But I do think he’d be a bit puzzled as to why Achilles is so favored and not Herakles, who was Alexander’s own real stan.

#asks#Achilles#Alexander the Great#Herakles#Hercules#Alexander the Great and Hercules#Alexander the Great and Herakles#Alexander the Great and Achilles#Achilles and Patroklos#Achilles and Patroclus#Heroic modeling in the ancient world

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello professor !

I was wondering how children were raised in general in Macedon.. and if Alexandros had a daughter how would she be raised (educated? Would he treat her differently than most might since he was such a mammas boy?) Or what about if he survived to raise his son, I know the general stuff about his childhood but would the child be raised in pella or would he stay on the road with Alexandros?

Your answers are always very fun to read!! Thank you for taking the time to answer them!! :)

First, let me point to Mark Golden’s 2015 second edition of his original 1990 Children and Childhood in Classical Athens. It’s an important revision to a classic and includes new evidence, an updated discussion and bibliography. You can get it used for c. $20.

The obvious caveat applies, right there in the title: …in Classical Athens. This reflects a problem for studies of ancient Greek to which I’ve referred before: we’re prisoners of our evidence and the bulk of our evidence is Athenian. Ergo, too often, discussion of “ancient Greek culture” is really “ancient Athenian culture.”

Why does that matter? Greece was a patchwork of different-but-related linguistic and religious groups. Ionic-Attic populations (which includes Athens) were different from Doric (which includes Sparta), who were different again from Aeolic, and then you have oddballs like Macedon. And Epiros. And Thessaly. And Crete. And Cyprus (areas on the perimeter).

You get the idea.

So general assumptions would apply, but specifics might not, such as specific religious festivals or dedications to this or that god. Nonetheless, broad characteristics of childhood and the family seem to have been pretty universal in Magna Graecae. When did newborns become persons (not at conception or even at birth, but a few days after). What was family life like? When did boys separate from their mothers to be raised as little men? What sorts of toys were available? When did childhood end?

Given those broad brushstrokes we can say a few things.

Pregnancy, childbirth, and infancy were very much the purview of women. Male physicians were brought in only for a problem. At a child’s birth, the midwife presented the baby to the father to acknowledge; if he turned his back, that was the cue to expose it. Fathers didn’t have a great deal of hands-on experience with infants, who stayed in the nursery, but especially in normal households, they'd have been exposed to them regularly. (The scene between Hektor, Andromake, and Astyanax in the Iliad is heartbreaking, but demonstrates that even elite fathers interacted with their children.) The birth of a son, especially the first, was a cause for celebration. The birth of a daughter, less so; she might be more celebrated if a son (or two) were already on deck. That’s not to say fathers didn’t love their daughters. We’ve plenty of evidence to the contrary. But excitement at the birth of a girl depended on other factors.

Infant mortality rates were relatively high, so there was a lot of “wait and see” following birth. Around day 7 or 10, the baby was brought into the family (i.e., became a person), and after the first year, more interest was taken in their future, including by the father.

Life for children (even elite children like Alexander) would have been a “whole family affair.” The Greeks had nuclear families but modified by several factors. The father’s elderly parents might live with them, especially when children were young. A widowed/unmarried sister (with no children) possibly also, but rarer. The family might also have a slave, possibly two. (Three+ tended to be a sign of wealth.) If two slaves, the second was probably a woman to help the mother with housework and childcare. Upper-class families would also have a nurse for young children, and a paidogogos (pedagogue, an elderly male slave who’d aged out of fieldwork), who kept an eye on boys outside the home (especially between 7-12/13). Children could become very fond of these non-relatives. Alexander reportedly loved his nurse, Lanikē, and his pedagogue, Lysimakos, although neither were slaves.

The notion that childcare is the mother’s primary or sole job is absurdly recent (and patently ridiculous). Even non-elite children would have had people in their lives besides parents and siblings; if the oikia (house) was occupied by Mama, Papa, and the kids, all around in the village or hamlet lived relatives. By-in-large, Greeks stayed where they were born, connected to land ownership and polis citizenship. Urban centers were a tad different, but not that much. Uncles and aunts lived nearby. “Distant” relatives were often sisters or nieces married to a man in a different town. Ergo, one grew up not only with siblings, but also cousins and other extended family. Given the rate of childhood death from disease, plus the dangers of warfare, most men wanted to have 2-3 boys, and 1-2 daughters. So 4-5 children was an ideal number. In a lot of fictional portrayals of Alexander, the fact he was 1 of 5 kids not that far apart in age (plus his cousin Amyntas), is often overlooked. He reads almost like an only child. He was anything but. (One reason I was keen to include his siblings in Dancing with the Lion.)

In any case, I think it important to keep in mind that children growing up had siblings, cousins, second- and third-cousins, maybe even the children of their slaves—all as playmates, babysitters, partners-in-crime, and sometimes antagonists. If gender divisions certainly existed, perhaps (in childhood) less than we might imagine.*

Until about the age of seven, all children remained with their mothers, living in the nursery and women’s rooms, although boys may have been taken out during the day to begin acquiring basic skills such as horsemanship, if the family were wealthy enough to own horses. And even young boys were encouraged to play with appropriately manly toys (miniature swords and armor, etc.)

In a boy’s seventh year, he left the women’s quarters to sleep with the men and, depending on his social status, to undergo basic education. If not elite, he’d have begun to work the farm with his father or learn his father’s craft. If he got any education (not free), it would have been what the family could afford and spare him for. Literacy among farmers, fisherman, and non-elite others was spotty, but the quantity of inscriptions by the 4th century argues for a rudimentary ability to read even among the lower classes (if not the abject poor).

After 12, non-elite boys would graduate to work with their fathers full time. In cities, they might have some free time for jobs on the side to get spending coin (fetch-and-carry, act as torch boys at night to lead home tipsy revelers: all the ancient version of lawn-mowing)—but this is pretty exclusively urban. In farming villages and hamlets, boys were working with Papa early. If they lived near enough to a large town with a gymnasion, they might engage in sports in late afternoon. A non-elite boy who showed promise in a sport might (like today) find a sponsor and be trained for a career in it on the Circuit (the Games).

Elite boys had a different path. They also left the nursery at 7 but were then carefully groomed to take their place as city leaders as well as to run their estates. They’d travel their properties with their fathers to learn the business, attend school, and the gymnasion to train physically. Once that initial schooling ended c. 12, they might attend lectures by sophists for some years, if in a sizable enough city—or be sent to one for such an education. This was less formal, the goal to train elite boys in rhetoric (giving speeches) and eristics (the art of argument), for a career in politics. (Sparta had their own system, but the training of elite Spartans bore commonalities with that of other elite boys around Greece.)

Girls never left the women’s rooms but began to learn skills quite young. That doesn’t mean they never played, or had pets, or had fun. Like boys, their education in wifely skills intensified after 10/11/12. Elite women almost certainly learned some letters, but it’s dubious how much farmer-class girls acquired. Reading wasn’t a necessary skill. Arithmatic was, to keep track of the larder, for counting in weaving patterns, etc. But they’d have been taught this by their mothers. Girls had no formal education (Sparta being something of an exception).

After a girl’s first menses, she occupied liminal space, considered “dangerous”: wild and emotional, so it was important to marry her off as soon as seemly and get her pregnant to anchor her wombs and thus ground her. First menses in antiquity occurred c. 13-14. She might then be betrothed at 14-15, and married at 15-16. Elite girls could be promised even earlier as those marriages were political and for business, but she wasn’t usually married until after her first menarch.

Ergo, except for elite boys (who might experience an “adolescent moratorium”), for most Greeks, “childhood” ended c. 12/13/14.