#Macedonian-Thracian similarities

Note

Hi Dr Reames!

Would you say that Macedon shared the same "political culture" with its Thracian and Illyrian neighbours, like how most Greeks shared the polis structure and the concept of citizenship?

I don't really know anything about Macedonian history before Philip II's time, but you've often brought up how the Macedonians shared some elements of elite culture (e.g. mound burials) with their Thracian neighbours, as well religious beliefs and practices.

I've only ever heard these people generically described as "a collection of tribes (that confederated into a kingdom)", which also seems to be the common description for nearby "Greek" polities like Thessaly and Epiros. So did these societies have a lot in common, structurally speaking, with Macedon? Or were they just completely different types of polities altogether?

First, in the interest of some good bibliography on the Thracians:

Z. H. Archibald, The Odrysian Kingdom of Thrace. Orpheus Unmasked. Oxford UP, 1998. (Too expensive outside libraries, but highly recommended if you can get it by interlibrary loan. Part of the exorbitant cost [almost $400, but used for less] owes to images, as it’s archaeology heavy. Archibald is also an expert on trade and economy in north Greece and the Black Sea region, and has edited several collections on the topic.

Alexander Fol, Valeria Fol. Thracians. Coronet Books, 2005. Also expensive, if not as bad, and meant for the general public. Fol’s 1977 Thrace and the Thracians, with Ivan Marazov, was a classic. Fol and Marazov are fathers of modern Thracian studies.

R. F. Hodinott, The Thracians. Thames and Hudson, 1981. Somewhat dated now but has pictures and can be found used for a decent price if you search around. But, yeah…dated.

For Illyria, John Wilkes’ The Illyrians, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, is a good place to start, but there’s even less about them in book form (or articles).

—————

Now, to the question.

BOTH the Thracians and Illyrians were made up of politically independent tribes bound by language and religion who, sometimes, also united behind a strong ruler (the Odrysians in Thrace for several generations, and Bardylis briefly in Illyria). One can probably make parallels to Germanic tribes, but it’s easier for me to point to American indigenous nations. The Odrysians might be compared to the Iroquois federation. The Illyrians to the Great Lakes people, united for a while behind Tecumseh, but not entirely, and disunified again after. These aren’t perfect, but you get the idea. For that matter, the Greeks themselves weren’t a nation, but a group of poleis bonded by language, culture, and religion. They fought as often as they cooperated. The Persian invasion forced cooperation, which then dissolved into the Peloponnesian War.

Beyond linguistic and religious parallels, sometimes we also have GEOGRAPHIC ones. So, let me divide the north into lowlands and highlands. It’s much more visible on the ground than from a map, but Epiros, Upper Macedonia, and Illyria are all more alike, landscape-wise, than Lower Macedonia and the Thracian valleys. South of all that, and different yet again, lay Thessaly, like a bridge between Southern Greece and these northern regions.

If language (and religion) are markers of shared culture, culture can also be shaped by ethnically distinct neighbors. Thracians and Macedonians weren’t ethnically related, yet certainly shared cultural features. Without falling into colonialist geographical/environmental determinism, geography does affect how early cultures develop because of what resources are available, difficulties of travel, weather, lay of the land itself, etc.

For instance, the Pindus Range, while not especially high, is rocky and made a formidable barrier to easy east-west travel. Until recently, sailing was always more efficient in Greece than travel by land (especially over mountain ranges).* Ergo, city-states/towns on the western coast tended to be western-facing for trade, and city-states/towns on the eastern side were, predictably, eastern-facing. This is why both Epiros and Ainai (Elimeia) did more trade with Corinth than Athens, and one reason Alexandros of Epiros went west to Italy while Alexander of Macedon looked east to Persia. It’s also why Corinth, Sparta, etc., in the Peloponnese colonized Sicily and S. Italy, while Athens, Euboia, etc., colonized the Asia Minor and Black Sea coasts. (It’s not an absolute, but one certainly sees trends.)

So, looking at their land, we can see why Macedonians and Thracians were both horse people with their wide valleys. They also practiced agriculture, had rich forests for logging, and significant metal (and mineral) deposits—including silver and gold—that made mining a source of wealth. They shared some burial customs but maintained acute differences. Both had lower status for women compared to Illyria/Epiros/Paionia. Yet that’s true only of some Thracian tribes, such as the Odrysians. Others had stronger roles for women. Thracians and Macedonians shared a few deities (The Rider/Zis, Dionysos/Zagreus, Bendis/Artemis/Earth Mother), although Macedonian religion maintained a Greek cast. We also shouldn’t underestimate the impact of Greek colonies along the Black Sea coast on inland Thrace, especially the Odrysians. Many an Athenian or Milesian (et al.) explorer/merchant/colonist married into the local Thracian elite.

Let’s look at burial customs, how they’re alike and different, for a concrete example of this shared regional culture.

First, while both Thracians and Macedonians had shrines, neither had temples on the Greek model until late, and then largely in Macedonia. Their money went into the ground with burials.

Temples represent a shit-ton of city/community money plowed into a building for public use/display. In southern Greece, they rise (pun intended) at the end of the Archaic Age as city-state sumptuary laws sought to eliminate personal display at funerals, weddings, etc. That never happened in Macedonia/much of the northern areas. So, temples were slow to creep up there until the Hellenistic period. Even then, gargantuan funerals and the Macedonian Tomb remained de rigueur for Macedonian elite. (The date of the arrival of the true Macedonian Tomb is debated, but I side with those who count it as a post-Alexander development.)

A “Macedonian Tomb” (above: Tomb of Judgement, photo mine) is a faux-shrine embedded in the ground. Elite families committed wealth to it in a huge potlatch to honor the dead. Earlier cyst tombs show the same proclivities, but without the accompanying shrine-like architecture. As early as 650 BCE at Archontiko (= ancient Pella), we find absurd amounts of wealth in burials (below: Archontiko burial goods, Pella Museum, photos mine). Same thing at Sindos, and Aigai, in roughly the same period. Also in a few places in Upper Macedonia, in the Archaic Age: Aiani, Achlada, Trebenište, etc.. This is just the tip of the iceberg. If Greece had more money for digs, I think we’d find additional sites.

Vivi Saripanidi has some great articles (conveniently in English) about these finds: “Constructing Necropoleis in the Archaic Period,” “Vases, Funerary Practices, and Political Power in the Macedonian Kingdom During the Classical Period Before the Rise of Philip II,” and “Constructing Continuities with a Heroic Past.” They’re long, but thorough. I recommend them.

What we observe here are “Princely Burials” across lingo-ethnic boundaries that reflect a larger, shared regional culture. But one big difference between elite tombs in Macedonia and Thrace is the presence of a BODY, and whether the tomb was new or repurposed.

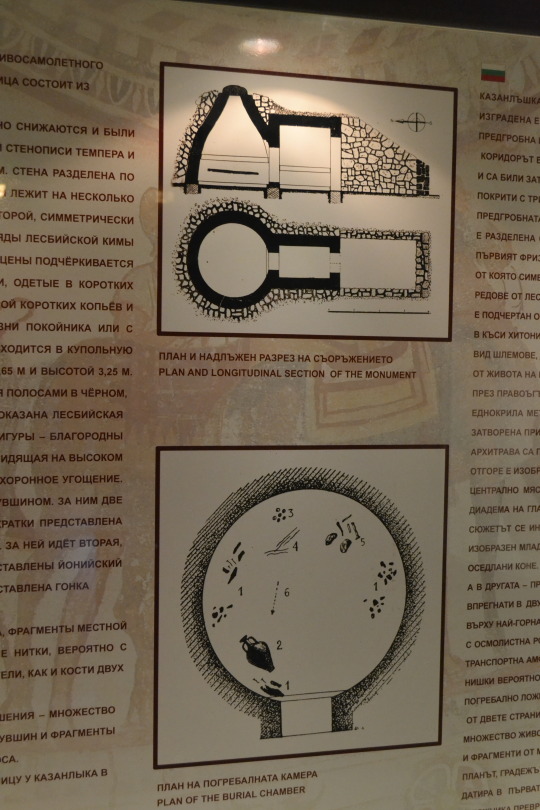

In Thrace, at least royal tombs are repurposed shrines (above: diagram and model of repurposed shrine-tombs). Macedonian Tombs were new construction meant to look like a shrine (faux-fronts, etc.). Also, Thracian kings’ bodies weren’t buried in their "tombs." Following the Dionysic/ Orphaic cult, the bodies were cut up into seven pieces and buried in unmarked spots. Ergo, their tombs are cenotaphs (below: Kosmatka Tomb/Tomb of Seuthes III, photos mine).

What they shared was putting absurd amounts of wealth into the ground in the way of grave goods, including some common/shared items such as armor, golden crowns, jewelry for women, etc. All this in place of community-reflective temples, as seen in the South. (Below: grave goods from Seuthes’ Tomb; grave goods from Royal Tomb II at Vergina, for comparison).

So, if some things are shared, others (connected to beliefs about the afterlife) are distinct, such as the repurposed shrine vs. new construction built like a shine, and the presence or absence of a body (below: tomb ceiling décor depicting Thracian deity Zalmoxis).

Aside from graves, we also find differences between highlands and lowlands in the roles of at least elite women. The highlands were tough areas to live, where herding (and raiding) dominated, and what agriculture there was required “all hands on deck” for survival. While that isn’t necessary for women to enjoy higher status (just look at Minoan Crete, Etruria, and even Egypt), it may have contributed to it in these circumstances.

Illyrian women fought. And not just with bows on horseback as Scythian women did. If we can believe Polyaenus, Philip’s daughter Kyanne (daughter of his Illyrian wife Audata) opposed an Illyrian queen on foot with spears—and won. Philip’s mother Eurydike involved herself in politics to keep her sons alive, but perhaps also as a result of cultural assumption: her mother was royal Lynkestian but her father was (perhaps) Illyrian. Epirote Olympias came to Pella expecting a certain amount of political influence that she, apparently, wasn’t given until Philip died. Alexander later observed that his mother had wisely traded places with Kleopatra, his sister, to rule in Epiros, because the Macedonians would never accept rule by a woman (implying the Epirotes would).

I’ve noted before that the political structure in northern Greece was more of a continuum: Thessaly had an oligarchic tetrarchy of four main clans, expunged by Jason in favor of tyranny, then restored by Philip. Epiros was ruled by a council who chose the “king” from the Aiakid clan until Alexandros I, Olympias’s brother, established a real monarchy. Last, we have Macedon, a true monarchy (apparently) from the beginning, but also centered on a clan (Argeads), with agreement/support from the elite Hetairoi class of kingmakers. Upper Macedonian cantons (formerly kingdoms) had similar clan rule, especially Lynkestis, Elimeia, and Orestis. Alas, we don’t know enough to say how absolute their monarchies were before Philip II absorbed them as new Macedonian districts, demoting their basileis (kings/princes) to mere governors.

I think continued highland resistance to that absorption is too often overlooked/minimized in modern histories of Philip’s reign, excepting a few like Ed Anson’s. In Dancing with the Lion: Rise, I touch on the possibility of highland rebellion bubbling up late in Philip’s reign but can’t say more without spoilers for the novel.

In antiquity, Thessaly was always considered Greek, as was (mostly) Epiros. But Macedonia’s Greek bona-fides were not universally accepted, resulting in the tale of Alexandros I’s entry into the Olympics—almost surely a fiction with no historical basis, fed to Herodotos after the Persian Wars. The tale’s goal, however, was to establish the Greekness of the ruling family, not of the Macedonian people, who were still considered barbaroi into the late Classical period. Recent linguistic studies suggest they did, indeed, speak a form of northern Greek, but the fact they were regarded as barbaroi in the ancient world is, I think instructive, even if not necessarily accurate.

It tells us they were different enough to be counted “not Greek” by some southern Greek poleis and politicians such as Demosthenes. Much of that was certainly opportunistic. But not all. The bias suggests Macedonian culture had enough overflow from their northern neighbors to appear sufficiently alien. Few Greek writers suggested the Thessalians or Epirotes weren’t Greek, but nobody argued the Thracians, Paiones, or Illyrians were. Macedonia occupied a liminal status.

We need to stop seeing these areas with hard borders and, instead, recognize permeable boundaries with the expected cultural overflow: out and in. Contra a lot of messaging in the late 1800s and early/mid-1900s, lifted from ancient narratives (and still visible today in ultra-national Greek narratives), the ancient Greeks did not go out to “civilize” their Eastern “Oriental” (and northern barbaroi) neighbors, exporting True Culture and Philosophy. (For more on these views, see my earlier post on “Alexander suffering from Conqueror’s Disease.”)

In fact, Greeks of the Late Iron Age (LIA)/Archaic Age absorbed a great deal of culture and ideas from those very “Oriental barbarians,” such as Lydia and Assyria. In art history, the LIA/Early Archaic Era is referred to as the “Orientalizing Period,” but it’s not just art. Take Greek medicine. It’s essentially Mesopotamian medicine with their religion buffed off. Greek philosophy developed on the islands along the Asia Minor coast, where Greeks regularly interacted with Lydians, Phoenicians, and eventually Persians; and also in Sicily and Southern Italy, where they were talking to Carthaginians and native Italic peoples, including Etruscans. Egypt also had an influence.

Philosophy and other cultural advances didn’t develop in the Greek heartland. The Greek COLONIES were the happenin’ places in the LIA/Archaic Era. Here we find the all-important ebb and flow of ideas with non-Greek peoples.

Artistic styles, foodstuffs, technology, even ideas and myths…all were shared (intentionally or not) via TRADE—especially at important emporia. Among the most significant of these LIA emporia was Methone, a Greek foundation on the Macedonian coast off the Thermaic Gulf (see map below). It provided contact between Phoenician/Euboian-Greek traders and the inland peoples, including what would have been the early Macedonian kingdom. Perhaps it was those very trade contacts that helped the Argeads expand their rule in the lowlands at the expense of Bottiaians, Almopes, Paionians, et al., who they ran out in order to subsume their lands.

My main point is that the northern Greek mainland/southern Balkans were neither isolated nor culturally stunted. Not when you look at all that gold and other fine craftwork coming out of the ground in Archaic burials in the region. We’ve simply got to rethink prior notions of “primitive” peoples and cultures up there—notions based on southern Greek narratives that were both political and culturally hidebound, but that have, for too long, been taken as gospel truth.

Ancient Macedon did not “rise” with Philip II and Alexander the Great. If anything, the 40 years between the murder of Archelaos (399) and the start of Philip’s reign (359/8) represents a 2-3 generation eclipse. Alexandros I, Perdikkas II, and Archelaos were extremely capable kings. Philip represented a return to that savvy rule.

(If you can read German, let me highly recommend Sabine Müller’s, Perdikkas II and Die Argeaden; she also has one on Alexander, but those two talk about earlier periods, and especially her take on Perdikkas shows how clever he was. For those who can’t read German, the Lexicon of Argead Macedonia’s entry on Perdikkas is a boiled-down summary, by Sabine, of the main points in her book.)

Anyway…I got away a bit from Thracian-Macedonian cultural parallels, but I needed to mount my soapbox about the cultural vitality of pre-Philip Macedonia, some of which came from Greek cultural imports, but also from Thrace, Illyria, etc.

Ancient Macedonia was a crossroads. It would continue to be so into Roman imperial, Byzantine, and later periods with the arrival of subsequent populations (Gauls, Romans, Slavs, etc.) into the region.

That fruit salad with Cool Whip, or Jello and marshmallows, or chopped up veggies and mayo, that populate many a family reunion or church potluck spread? One name for it is a “Macedonian Salad”—but not because it’s from Macedonia. It’s called that because it’s made up of many [very different] things. Also, because French macedoine means cut-up vegetables, but the reference to Macedonia as a cultural mishmash is embedded in that.

---------------

* I’ve seen this personally between my first trip to Greece in 1997, and the new modern highway. Instead of winding around mountains, the A2 just blasts through them with tunnels. The A1 (from Thessaloniki to Athens) was there in ’97, and parts of the A2 east, but the new highway west through the Pindus makes a huge difference. It takes less than half the time now to drive from the area around Thessaloniki/Pella out to Ioannina (near ancient Dodona) in Epiros. Having seen the landscape, I can imagine the difficulties of such a trip in antiquity with unpaved roads (albeit perhaps at least graded). Taking carts over those hills would be daunting. See images below.

#asks#ancient Macedonia#ancient Thrace#ancient Epiros#ancient Thessaly#Argead Macedonia#pre-Philip Macedonia#Late Iron Age Greece#Archaic Age Greece#Thracian tombs#Macedonian tombs#Classics#tagamemnon#Alexander the Great#Philip II of Macedon#Philip of Macedon#women in ancient Macedonia#ancient Illyria#women in Illyria#Macedonian-Thracian similarities#religion in ancient Thrace#religion in ancient Macedonia

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, thank you for the answer about Orpheus!

Yes, Tomasz Mojsik wrote a book? study? on it, The “Double Orpheus”: between Myth and Cult”, it's available online. He draws interesting conclusions and seems to be quoting original sources a lot, though I'm curious what you think on the whole logic behind myth-making as a political move in 5th c. Athens after getting familiar with it.

Have a good day!

At first I thought it was a book and I was scared but okay it’s just a scientific article phewwww 😂

To summarise, Tomasz Mojsik discusses that there was a duality in Orpheus’ ethnical identity. He was perceived as Thracian in general, but also mostly by the Athenians at a time during which they had created a powerful colony in Thrace and were interested in peace and alliance with the then Thracian King. On the other hand, many records regard Orpheus as Pierian Macedonian and this version probably rose at a time when King Archelaus of Macedon was trying to reinforce or persuade of the Hellenism of Macedonia and used this retelling of the Greek mythological figure being Macedonian as evidence of Macedonians being essentially Greeks.

My thoughts now… My impression is that there is a lot of assumption to be found in this research, which is to be expected in a way, since the author’s effort bears little promise from the beginning. We are talking about mythological retellings, which might as well have totally random explanations. I mean, it is a very risky area to draw safe scientific conclusions from.

Technically, it could make sense.

However while Mojsik notes this, he also then sort of ignores it in his reasoning; Greek Mythology sort of hellenizes all the known to the Greeks world. Progenitors and other notable mythological figures all have Greek names, speak fluently Greek, believe in the Greek gods, even when they come from different lands with different cultures. In this sense, Orpheus’ duality isn’t any different from all other supposedly non-Greek figures. They all have certain connections or distant origins from major or lesser deities of the Greek pantheon. As a result they do have a vague Greek origin or even not so vague, even though realistically they should have been total foreigners. If we had to explain everything in a similar way then a whole lot of mythological figures would just exist because Greeks were trying to form alliances with everyone. That’s unlikely IMO because we are just talking about an ancient people creating a lore for themselves. There was no need for accuracy or realism. It is a mystical lore putting gods living a few miles north, so essentially themselves, to the centre of all existence.

Therefore Orpheus being Thracian doesn’t stop him from technically being indistinguishable from all Greeks in all the myths associated with him. He doesn’t speak a different language, Chiron and Jason accept him, his mother is one of the freaking muses, some versions even have him to be the son of Apollo right away.

The actual Thracian equivalent of Orpheus was associated with some cult antagonism between solar and chthonic worshippers. This could have been transferred into Greek mythology via Orpheus being a son of Apollo and then entering Hades to bring back Eurydice. I believe all these might precede the 5th-4th centuries BC. So just because Athens then had these alliances with the Thracians it does not mean it called Orpheus a Thracian to cater to…whom, exactly? A Thracian king? All the Thracians? Please, let’s not forget we are talking about more than two millennias ago. Even if Athenian historians and poets chose to do that, it is certain that very very very very few Thracians would ever found out about it. And even if they sent messengers to the king, they would be like “Just so you know, King, we Athenians think a random mythological figure of ours was Thracian” and then surely the Thracian king would be like “Great! For this alone I am gonna be your ally in peace and war for all time!”.

I know I seem like I am making light of the article. I don’t deny that there might be a truth in Mojsik’s reasoning, but my point is that typically things don’t work this way. Whether propaganda or accurate information, it could not spread and be effective in ancient times as it is now through all the media. Even if the supposed propaganda targeted Athenians themselves, so that Athenians would want tighter bonds with Thracians, I still don’t see how this would guarantee success as in the same sense Athenians would have to want tight bonds with all nations with some associated mythological figure… Let alone that again, many Athenians wouldn’t find out and and even more wouldn’t care.

Besides, we need to stress again that the Thracian in the way he was presented in Greek mythology was very different from the actual living Thracian born in a Thracian family. The mythological one was just a Greek born in Thrace or having some obscure genealogical connection to a Thracian (who was also Greek-passing).

Now, as for the Macedonian version. Technically, in a version where Orpheus was the child of Calliope and Apollo, you can say that in fact Orpheus was an Olympian, and therefore a Pierian Macedonian! This completely eradicates his Thracian identity. Or, even if his father was the Thracian Oeagrus, that still makes him half-Macedonian Greek, half-Thracian, provided that you can call gods an ethnicity.

There is also this question: why was Orpheus’ ethnicity so important to Archelaus? If you already live in Pieria, under the shadow of Olympus, how and why is Orpheus the one expected to make a difference in the identity of the Macedonians?

My theory is that they would care enough for it only if being Thracian was perceived as a threat. The Macedonians did not want to worship a figure that was viewed as Thracian (even in a very loose sense of the term). True enough, the article confirms that at the time Macedonians and Thracians had many tensions.

We also should remember that ancient kingdoms and states did not have the concept of sovereignty and nationality in the way we do now. Macedonia and Thrace were neighbours and as such their populations blended and bled into each other’s region. There were surely Thracians and Macedonians practicing Orphism in Macedonia (and vice versa). If Archelaus considered Orphism was gaining a lot of ground and feared for the established “mainstream” Greek religion, perhaps he did try to macedonify and hellenise Orpheus. Or maybe he just wanted to weaken Thracians and solidify his kingdom in its Greek orientation. Mojsik didn’t analyse this as much but I guess more or less my theory can work with his study.

But all these are very unsafe theories since we are talking about scarce yet various tales associated with ancient beliefs. I don’t think we have enough evidence for any certain conclusion.

Hopefully this made some sense because it is super late at night (or super early in the morning!) and my speech might be a little incoherent.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythology

Early life

According to Apollodorus and a fragment of Pindar, Orpheus' father was Oeagrus, a Thracian king, or, according to another version of the story, the god Apollo. His mother was (1) the muse Calliope, (2) her sister Polymnia, (3) a daughter of Pierus, son of Makednos or (4) lastly of Menippe, daughter of Thamyris. According to Tzetzes, he was from Bisaltia. His birthplace and place of residence was Pimpleia close to the Olympus. Strabo mentions that he lived in Pimpleia. According to the epic poem Argonautica, Pimpleia was the location of Oeagrus' and Calliope's wedding. While living with his mother and her eight beautiful sisters in Parnassus, he met Apollo, who was courting the laughing muse Thalia. Apollo, as the god of music, gave Orpheus a golden lyre and taught him to play it. Orpheus' mother taught him to make verses for singing. He is also said to have studied in Egypt.

Orpheus is said to have established the worship of Hecate in Aegina. In Laconia Orpheus is said to have brought the worship of Demeter Chthonia and that of the Κόρες Σωτείρας (Kóres Sōteíras; 'Saviour Maidens'). Also in Taygetos a wooden image of Orpheus was said to have been kept by Pelasgians in the sanctuary of the Eleusinian Demeter.

According to Diodorus Siculus, Musaeus of Athens was the son of Orpheus.

Adventure as an Argonaut

Main article: Argonautica

The Argonautica (Ἀργοναυτικά) is a Greek epic poem written by Apollonius Rhodius in the 3rd century BC. Orpheus took part in this adventure and used his skills to aid his companions. Chiron told Jason that without the aid of Orpheus, the Argonauts would never be able to pass the Sirens—the same Sirens encountered by Odysseus in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. The Sirens lived on three small, rocky islands called Sirenum scopuli and sang beautiful songs that enticed sailors to come to them, which resulted in the crashing of their ships into the islands. When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew his lyre and played music that was louder and more beautiful, drowning out the Sirens' bewitching songs. According to 3rd century BC Hellenistic elegiac poet Phanocles, Orpheus loved the young Argonaut Calais, "the son of Boreas, with all his heart, and went often in shaded groves still singing of his desire, nor was his heart at rest. But always, sleepless cares wasted his spirits as he looked at fresh Calais."

Death of Eurydice

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife Eurydice (sometimes referred to as Euridice and also known as Argiope). While walking among her people, the Cicones, in tall grass at her wedding, Eurydice was set upon by a satyr. In her efforts to escape the satyr, Eurydice fell into a nest of vipers and suffered a fatal bite on her heel. Her body was discovered by Orpheus who, overcome with grief, played such sad and mournful songs that all the nymphs and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus traveled to the underworld. His music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone, who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until they both had reached the upper world. Orpheus set off with Eurydice following; however, as soon as he had reached the upper world, he immediately turned to look at her, forgetting in his eagerness that both of them needed to be in the upper world for the condition to be met. As Eurydice had not yet crossed into the upper world, she vanished for the second time, this time forever.

The story in this form belongs to the time of Virgil, who first introduces the name of Aristaeus (by the time of Virgil's Georgics, the myth has Aristaeus chasing Eurydice when she was bitten by a serpent) and the tragic outcome. Other ancient writers, however, speak of Orpheus' visit to the underworld in a more negative light; according to Phaedrus in Plato's Symposium, the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him. In fact, Plato's representation of Orpheus is that of a coward, as instead of choosing to die in order to be with the one he loved, he instead mocked the gods by trying to go to Hades to bring her back alive. Since his love was not "true"—he did not want to die for love—he was actually punished by the gods, first by giving him only the apparition of his former wife in the underworld, and then by being killed by women. In Ovid's account, however, Eurydice's death by a snake bite is incurred while she was dancing with naiads on her wedding day.

Virgil wrote in his poem that Dryads wept from Epirus and Hebrus up to the land of the Getae (north east Danube valley) and even describes him wandering into Hyperborea and Tanais (ancient Greek city in the Don river delta) due to his grief.

The story of Eurydice may actually be a late addition to the Orpheus myths. In particular, the name Eurudike ("she whose justice extends widely") recalls cult-titles attached to Persephone. According to the theories of poet Robert Graves, the myth may have been derived from another Orpheus legend, in which he travels to Tartarus and charms the goddess Hecate.

The myth theme of not looking back, an essential precaution in Jason's raising of chthonic Brimo Hekate under Medea's guidance, is reflected in the Biblical story of Lot's wife when escaping from Sodom. More directly, the story of Orpheus is similar to the ancient Greek tales of Persephone captured by Hades and similar stories of Adonis captive in the underworld. However, the developed form of the Orpheus myth was entwined with the Orphic mystery cults and, later in Rome, with the development of Mithraism and the cult of Sol Invictus.

Death

According to a Late Antique summary of Aeschylus' lost play Bassarids, Orpheus, towards the end of his life, disdained the worship of all gods except the sun, whom he called Apollo. One early morning he went to the oracle of Dionysus at Mount Pangaion to salute his god at dawn, but was ripped to shreds by Thracian Maenads for not honoring his previous patron (Dionysus) and was buried in Pieria. Here his death is analogous with that of Pentheus, who was also torn to pieces by Maenads; and it has been speculated that the Orphic mystery cult regarded Orpheus as a parallel figure to or even an incarnation of Dionysus. Both made similar journeys into Hades, and Dionysus-Zagreus suffered an identical death. Pausanias writes that Orpheus was buried in Dion and that he met his death there. He writes that the river Helicon sank underground when the women that killed Orpheus tried to wash off their blood-stained hands in its waters. Other legends claim that Orpheus became a follower of Dionysus and spread his cult across the land. In this version of the legend, it is said that Orpheus was torn to shreds by the women of Thrace for his inattention.

Ovid recounts that Orpheus ...

had abstained from the love of women, either because things ended badly for him, or because he had sworn to do so. Yet, many felt a desire to be joined with the poet, and many grieved at rejection. Indeed, he was the first of the Thracian people to transfer his affection to young boys and enjoy their brief springtime, and early flowering this side of manhood.

— Ovid. trans. A. S. Kline, Ovid: The Metamorphoses, Book X

Feeling spurned by Orpheus for taking only male lovers (eromenoi), the Ciconian women, followers of Dionysus, first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, but his music was so beautiful even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the women tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies. In Albrecht Dürer's drawing of Orpheus' death, based on an original, now lost, by Andrea Mantegna, a ribbon high in the tree above him is lettered Orfeus der erst puseran ("Orpheus, the first pederast").

His head and lyre, still singing mournful songs, floated down the River Hebrus into the sea, after which the winds and waves carried them to the island of Lesbos, at the city of Methymna; there, the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honour near Antissa; there his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo. In addition to the people of Lesbos, Greeks from Ionia and Aetolia consulted the oracle, and his reputation spread as far as Babylon.

Cave of Orpheus' oracle in Antissa, Lesbos

Orpheus' lyre was carried to heaven by the Muses, and was placed among the stars. The Muses also gathered up the fragments of his body and buried them at Leibethra below Mount Olympus, where the nightingales sang over his grave. After the river Sys flooded

Leibethra, the Macedonians took his bones to Dion. Orpheus' soul returned to the underworld, to the fields of the Blessed, where he was reunited at last with his beloved Eurydice.

Another legend places his tomb at Dion, near Pydna in Macedon. In another version of the myth, Orpheus travels to Aornum in Thesprotia, Epirus to an old oracle for the dead. In the end Orpheus commits suicide from his grief unable to find Eurydice.

"Others said that he was the victim of a thunderbolt."

From Wikipedia

••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

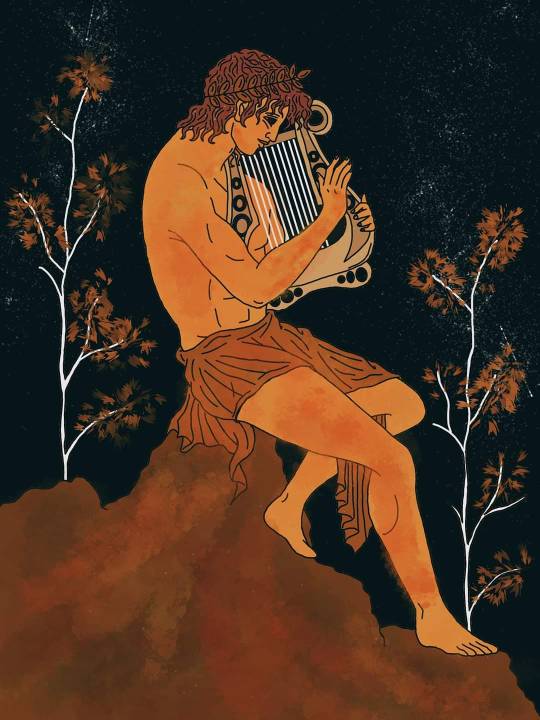

Orpheus the musician & beast tamer.

Art by Brittany Beverung @artistfuly

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anonymous asked: Who are some women in history that would be comparable to Napoleon or Alexander? Women who rose to power because they sought greatness and not because they used the feminine form to seduce for an easier life? How can the feminine mind come out of the mentality of being “the weaker sex”?

The short answer is that there are no women in history comparable to Napoleon or Alexander but equally I would quickly add that there are no other men in history either. These two contrasting men are unique. Alexander and Napoleon share similarities in their warfare, and how they used it to conquer and establish new lands. Both left legacies in which their very name has been equally loathed and loved down the ages. But they were unique.

Both were outsiders whose personal qualities rose above obstacles. Alexander was Macedonian and the Greeks looked down upon him as uncultured barbarian in the same way Napoleon was Corsican nobility and the old French aristocracy pulled up their noses in snobbish superiority. And yet able to rise through the grit of discipline and learning, luck and skill.

Both were great battle field commanders with a greater understanding of how to use one’s forces at hand to the terrain. Both were not quite true innovators as many might imagine. Alexander's military brilliance is beyond dispute but the groundwork for his superior tactics and strategies were laid by his father Philip of Macedon. Much of Napoleon’s greatness relied on the conscription model that the French revolutionary wars ushered in.

Alexander used new technology in new ways, invented new formations, and used his battlefield successes to accomplish his strategic goals with the innovative use of propaganda that was unseen before. Alexander was very unmatched in winning battles against much larger enemy formations as he was often outnumbered 2:1. He was a tactical genius in finding the weakness in the enemy’s lines and making the surgical strike necessary to ensure victory. He was quick witted at being able to make quick tactical decisions in the thick of the battle.

He was able to snatch victory from the claws of certain defeat, time and again, always against overwhelming enemy superiority in numbers, always in a terrain that his enemies had carefully chosen to maximise their advantages.

Any city he ever attacked he conquered. His own father the great Philip II failed to take Byzantium, and was defeated by Thracian tribesmen, but not Alexander. He made land out of a sea and conquered the heavily fortified island city of Tyre, and he used rock climbers to take the Sogdian Rock in Bactria/Afghanistan, an impregnable citadel that was compared to an eagle’s nest. Moreover he never lost a battle.

Napoleon was a brilliant general and even in his time earned grudging respect from his enemies. Napoleon was very successful in most of his military campaigns, and that laid the foundation necessary for his political achievements.

He fought 60 battles in his career, losing only 8 with two being considered “tactical victories” only (Second Bassano and Aspern-Esseling) . Nevertheless in the vast majority of his defeats (as well as victories) he was horrendously outnumbered, logistical suffocated, or betrayed by his allies.

He was exceptionally talented both strategically and tactically. In campaign after campaign he defeated larger armies with a smaller force, through methods like moving boldly and quickly, defeating them in detail, cutting off their lines of retreat, and doing what his enemies least expected.

Less glamorously but even more important he was great at logistics. One of his most famous maxims is that, “An army marches on its stomach.” If troops are not well equipped and well fed, they can not be expected to fight well. Napoleon had his armies live off the land, and marched faster than his enemies. While Napoleon still had supply lines, much of the food, clothing, and pay for his men was looted from conquered territory. This allowed him to march faster, and he often did forced marches where his men would march twice as far each day as the enemy predicted.

His opponents were often shocked at how quickly he outmanoeuvred them. At Ulm he surrounded an enormous Austrian army and forced them to surrender - while they thought he was over a hundred miles to the west and were waiting for reinforcements. Again, another thing that got him into trouble in Russia: the Russians retreated even faster, and burned everything in their wake, so there was nothing to loot.

He was innovative too in his use of light horse artillery - smaller cannons were pulled by fast horses, ridden by their crew - who could get into position rapidly and move into a new area when required. Napoleon loved these guys and used them in combination with his slower artillery to great effect often in support of heavy artillery.

Both were inspirational leaders of men in battle. In Alexander’s case he almost killed himself jumping into the Indian city of the Malians alone, a wound which weakened his body and eventually probably contributed to his death.

He was simply fearless. Like the Carthagenian Hannibal, and all ancient Greek military leaders, Miltiades, Epameinondas, Philipos II, etc, and Romans, like Caesar, Alexander was always leading from the front line. In Napoleon’s case he too was fearless At Arcole he tried to inspire his men to attack, by grabbing a flag and stood in the open on the dike about 55 paces from the bridge. Both were loved by their men and their very presence on the battlefield was an inspiration to their fighting men.

Both were superb political strategists who were able to build on military gains with statecraft skills. Alexander the Great’s strong perseverance and incredible battle strategies led to increase his power over his empire. Napoleon used his intelligence and skill of manipulation to earn respect and support from the French people, which gained him great power.

For all this, they were both losers in the end. Both lost because they failed the most valuable lesson history can give: success is a bad teacher. Their military victories made them increasingly cocky and their political gains made them overreach. In the end their own personal qualities that brought them so much unprecedented success was the harbinger of their downfall.

So we are left with the question: what is greatness? The judgement of history seems to suggest that glory is fleeting but true greatness lasts the test of time.

There are simply too many women to list that would be worthy of anyone’s attention to show that women have achieved greatness throughout history.

Here is a good basic list of warrior women in recorded history https://www.rejectedprincesses.com/women-in-combat

Indeed one doesn’t have to stray too far from antiquity to show that women as warriors did make an impact.

I shall just focus on a few from antiquity that stand out for me and and a few more modern choices that are very personal to me.

Penthesilea

I had heard of Penthesilea and the Amazons before as a small girl. But the first time I really understand just how impressive and unusual it was in the ancient world to be a woman who “fights with men” was when I was taking Latin at my English girls’ boarding school.

Contrary to popular belief, Penthesilea’s story isn’t actually told in the Iliad (which ends with Hector’s funeral, before the Amazons arrive), but in a lost ancient epic called Aethiopis. This poem continued the story of Achilles’ great deeds, which included the killing of several famous warriors—Memnon, King of Aethiopia, and Penthesilea most prominent among them.

The Amazons had a number of famous Queens, but Penthesilea is perhaps the most storied. She was a daughter of the war-god Ares, and Pliny credits her with the invention of the battle-ax. She was also sister to Hippolyta, who married the hero Theseus, after being defeated by him in battle. Penthesilea ruled the Amazons during the years of the Trojan war—and for most of that time stayed away from the conflict. However, after Achilles killed Hector, Penthesilea decided it was time for her Amazons to intervene, and the group rode to the rescue of the Trojans—who were, after all, fellow Anatolians. Fearless, she blazed through the Greek ranks, laying waste to their soldiers.

During the battles, Penthesilea was not a queen who sat by and watched the men fight. She was a warrior in the truest sense. It is said that she blazed through the Greeks like lightning, killing many. It is written that she was swift and brave, and fought as valiantly and successfully as the men. She wanted to prove that the Amazons were great warriors. She wanted to kill Achilles to avenge the death of Hector, and she wanted to die in battle. I love Vergil’s glorious description of her in battle: “The ferocious Penthesilea, gold belt fastened beneath her exposed breast, leads her battle-lines of Amazons with their crescent light-shields…a warrioress, a maiden who dares to fight with men.”

Although Penthesilea was a ferocious warrior, her life came to an end, at the hands of Achilles. Achilles had seen her battling others, and was enamored with her ferocity and strength. As he fought, he worked his way towards her, like a moth drawn to a flame. While he was drawn to her with the intention of facing her as an opponent, he fell in love with her upon facing her. However, it was too late.

Achilles defeated Penthesilea, catching her as she fell to the ground. Greek warrior Thersites mocked Achilles for his treatment of Penthesilea’s body after her death. It is also said that Thersites removed Penthesilea’s eyes with his sword. This enraged Achilles, and he slaughtered Thersites. Upon Thersites’ death, a sacred feud was fought. Diomedes, Thersite’s cousin, retrieved Penthesilea’s corpse, dragged it behind his chariot, and cast it into the river. Achilles retrieved the body, and gave her a proper burial. In some stories, Achilles is accused of engaging in necrophilia with her body. In other legends, it is said that Penthesilea bore Achilles a son after her death. Yes, I agree, that does feel creepy.

Penthesilea’s life and death were tragic. She is portrayed as a brave and fierce warrior who was deeply affected by the accidental death of her sister. This grief, compounded with her desire to be a strong warrior who would die an honourable death on the battlefield, led her to Troy, where her tragic death weakened Troy, but also led to unrest in the Greek camps due to her death’s impact on Achilles and his revengeful acts. In the end, she died the ‘honorable’ death on the battlefield that she had longed for, at the hands of the legendary Achilles, no less.

The heroines of Greek mythology tend towards thoughtfulness, fidelity and modesty (Andromache, Penelope), while the daring and headstrong personalities generally go to the antagonists–Medea, Clytemnestra, Hera. But Penthesilea is something else entirely: a woman who meets men on her own terms, as their equal. Perhaps in honour of this, Virgil doesn’t give her the standard heroine epithet of “beautiful.” For him, it is her majesty and obvious power that make her notable, not her looks.

By the way, the word that Virgil uses for warrioress is bellatrix, the inspiration for Bellatrix Lestrange’s name in the Harry Potter books. So she lives on in immortality through our modern day Virgil, J.K. Rowling (just kidding)

Cynane (c. 358 – 323 BC)

Cynane was the daughter of King Philip II of Macedon and his first wife, the Illyrian Princess Audata. She was also the half-sister of Alexander the Great. Audata raised Cynane in the Illyrian tradition, training her in the arts of war and turning her into an exceptional fighter – so much so that her skill on the battlefield became famed throughout the land. Cynane accompanied the Macedonian army on campaign alongside Alexander the Great and according to the historian Polyaenus, she once slew an Illyrian queen and masterminded the slaughter of her army. Such was her military prowess. Following Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, Cynane attempted an audacious power play. In the ensuing chaos, she championed her daughter, Adea, to marry Philip Arrhidaeus, Alexander’s simple-minded half-brother who the Macedonian generals had installed as a puppet king. Yet Alexander’s former generals – and especially the new regent, Perdiccas – had no intention of accepting this, seeing Cynane as a threat to their own power. Undeterred, Cynane gathered a powerful army and marched into Asia to place her daughter on the throne by force.

As she and her army were marching through Asia towards Babylon, Cynane was confronted by another army commanded by Alcetas, the brother of Perdiccas and a former companion of Cynane. However, desiring to keep his brother in power Alcetas slew Cynane when they met – a sad end to one of history’s most remarkable female warriors. Although Cynane never reached Babylon, her power play proved successful. The Macedonian soldiers were angered at Alcetas’ killing of Cynane, especially as she was directly related to their beloved Alexander. Thus they demanded Cynane’s wish be fulfilled. Perdiccas relented, Adea and Philip Arrhidaeus were married, and Adea adopted the title Queen Adea Eurydice.

Olympias and Eurydice

The mother of Alexander the Great, Olympias was one of the most remarkable women in antiquity. She was a princess of the most powerful tribe in Epirus (a region now divided between northwest Greece and southern Albania) and her family claimed descent from Achilles. Despite this impressive claim, many Greeks considered her home kingdom to be semi-barbarous – a realm tainted with vice because of its proximity to raiding Illyrians in the north. Thus the surviving texts often perceive her as a somewhat exotic character.

In 358 BC Olympias’ uncle, the Molossian King Arrybas, married Olympias to King Philip II of Macedonia to secure the strongest possible alliance. She gave birth to Alexander the Great two years later in 356 BC.

Further conflict was added to an already tempestuous relationship when Philip married again, this time a Macedonian noblewoman called Cleopatra Eurydice.

Olympias began to fear this new marriage might threaten the possibility of Alexander inheriting Philip’s throne. Her Molossian heritage was starting to make some Macedonian nobles question Alexander’s legitimacy. Thus there is a strong possibility that Olympias was involved in the subsequent murders of Philip II, Cleopatra Eurydice and her infant children. She is often portrayed as a woman who stopped at nothing to ensure Alexander ascended the throne. Following Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BC, she became a major player in the early Wars of the Successors in Macedonia. In 317 BC, she led an army into Macedonia and was confronted by an army led by another queen: none other than Cynane’s daughter, Adea Eurydice.

This clash was the first time in Greek history that two armies faced each other commanded by women. However, the battle ended before a sword blow was exchanged. As soon as they saw the mother of their beloved Alexander the Great facing them, Eurydice’s army deserted to Olympias. Upon capturing Eurydice and Philip Arrhidaeus, Eurydice’s husband, Olympias had them imprisoned in squalid conditions. Soon after she had Philip stabbed to death while his wife watched on.

On Christmas Day 317, Olympias sent Eurydice a sword, a noose, and some hemlock, and ordered her to choose which way she wanted to die. After cursing Olympias’ name that she might suffer a similarly sad end, Eurydice chose the noose. Olympias herself did not live long to cherish this victory. The following year Olympias’ control of Macedonia was overthrown by Cassander, another of the Successors. Upon capturing Olympias, Cassander sent two hundred soldiers to her house to slay her.

However, after being overawed by the sight of Alexander the Great’s mother, the hired killers did not go through with the task. Yet this only temporarily prolonged Olympias’ life as relatives of her past victims soon murdered her in revenge.

Artemisia I of Caria (5th Century BC)

Named after the Goddess of the Hunt (Artemis), Artemisia was the 5th century BCE Queen of Halicarnassus, a kingdom that exists in modern-day Turkey. However, she was best known as a naval commander and ally of Xerxes, the King of Persia, in his invasion of the Greek city-states. (Yes, like in the action movie 300: Rise of an Empire.)

She made her mark on history in the Battle of Salamis, where the fleet she commanded was deemed the best against the Greeks. Greek historian Herodotus wrote of her heroics on this battlefield of the sea, painting her as a warrior who was decisive and incredibly intelligent in her strategies. This included a ruthless sense of self-preservation. With a Greek vessel bearing down on her ship, Artemisia intentionally steered into another Persian vessel to trick the Greeks into believing she was one of them. It worked. The Greeks left her be. The Persian ship sank. Watching from the shore, Xerxes saw the collision and believed Artemisia had sunk a Greek enemy, not one of his own.

For all of this, her death was not one recorded in a great battle, but in legends written by the victors, the Greeks - so one must obviously be skeptical of accepting what they said as 100% truth. It's said that Artemisia fell hard for a Greek man, who ignored her to his detriment. Blinded by love, she blinded him in his sleep. Yet even with him disfigured, her passion for him burned. To cure herself, she set to leap from a tall rock in Leucas, Greece, which was believed to break the bonds of love. Instead, it broke Artemisia's neck. She's said to be buried nearby.

But much like Penthesilea, she lives on in our modern culture, but arguably more dubiously through Hollywood in the sub-par action movie 300: Rise of an Empire. Now I forever think of Artemisia as the beautiful and sultry French actress, Eva Green.

Boadicea (also written as Boudica)

Boadicea was a Celtic queen who led a revolt against Roman rule in ancient Britain in A.D. 60 or 61. As all of the existing information about her comes from Roman scholars, particularly Tacitus and Cassius Dio, little is known about her early life; it’s believed she was born into an elite family in Camulodunum (now Colchester) around A.D. 30.

At the age of 18, Boudica married Prasutagas, king of the Iceni tribe of modern-day East Anglia. When the Romans conquered southern England in A.D. 43, most Celtic tribes were forced to submit, but the Romans let Prasutagas continue in power as a forced ally of the Empire. When he died without a male heir in A.D. 60, the Romans annexed his kingdom and confiscated his family’s land and property. As a further humiliation, they publicly flogged Boadicea and raped her two daughters. Tacitus recorded Boudicca’s promise of vengeance after this last violation: “Nothing is safe from Roman pride and arrogance. They will deface the sacred and will deflower our virgins. Win the battle or perish, that is what I, a woman, will do.”

Like other ancient Celtic women, Boadicea had trained as a warrior, including fighting techniques and the use of weapons. With the Roman provincial governor Gaius Suetonius Paulinus leading a military campaign in Wales, Boadicea led a rebellion of the Iceni and members of other tribes resentful of Roman rule. After defeating the Roman Ninth Legion, the queen’s forces destroyed Camulodunum, then the captain of Roman Britain, and massacred its inhabitants. They went on to give similar treatment to London and Verulamium (modern St. Albans). By that time, Suetonius had returned from Wales and marshaled his army to confront the rebels. In the clash that followed–the exact battle site is unknown, but possibilities range from London to Northamptonshire–the Romans managed to defeat the Britons despite inferior numbers, and Boadicea and her daughters apparently killed themselves by taking poison in order to avoid capture.

In all, Tacitus claimed, Boadicea’s forces had massacred some 70,000 Romans and pro-Roman Britons. Though her rebellion failed, and the Romans would continue to control Britain until A.D. 410, Bouadicea is celebrated today as a British national heroine and an embodiment of the struggle for justice and independence.

Queen Zenobia

In the 3rd century AD, Queen Zenobia, natively know as Bath Zabbai, was a fierce ruler of Palmyra, a region in modern day Syria. Throughout her life, Zenobia became known as the ‘warrior queen’. She expanded Palmyra from Iraq to Turkey, conquered Egypt and challenged the dominance of Rome.

“Zenobia was esteemed the most lovely as well as the most heroic of her sex,” Gibbon wrote in an awestruck account of her brief reign. “She claimed her descent from the Macedonian kings of Egypt, equaled in beauty her ancestor Cleopatra, and far surpassed that princess in chastity and valour.” The only contemporary representation we have of Zenobia is on a coin, which makes her look rather witchlike, but Gibbon’s description of her pearly-white teeth and large black eyes, which “sparkled with uncommon fire,” cast a spell over future historians, both in the West and in the Arab world, who quarrel over nearly everything having to do with Zenobia and her confounding legacy.

Many legends have arisen about Zenobia’s identity, but it seems she was born into a family of great nobility who claimed the notorious Queen Dido of Carthage and Cleopatra VII of Egypt as ancestors. She was given a Hellenistic education, learning Latin, Greek, the Syriac and Egyptian languages. According to the Historia Augusta her favourite childhood hobby was hunting, and she proved to be a brave and brilliant horsewoman.

Despite this, many ancient sources seem to gravitate to one quality – that she was an exceptional beauty who captivated men across the whole of Syria with her ravishing looks and irresistible charm.

She was probably in her twenties when she took the throne, upon the death of her husband, King Odenathus, in 267 or 268. Acting as regent for her young son, she then led the army in a revolt against the Romans, conquering Egypt and parts of Asia Minor. By 271, she had gained control of a third of the Roman Empire. Gibbon sometimes portrays the warrior queen as a kind of well-schooled Roman society matron. “She was not ignorant of the Latin tongue,” he writes, “but possessed in equal perfection the Greek, the Syriac, and the Egyptian languages.” Palmyra’s abundant wall inscriptions are in Latin, Greek, and an Aramaic dialect, not Arabic. But to Arab historians, such as the ninth-century al-Tabari, Zenobia was a tribal queen of Arab, rather than Greek, descent, whose original name was Zaynab, or al-Zabba. Among Muslims, she is seen as a herald of the Islamic conquests that came four centuries later.

This view, popular within the current Syrian regime, which boasts Zenobia on its currency, also resonates within radical Islamic circles. Isis radical fighters have believed Palmyra to be somehow a distinctively Arab place, where Zenobia stood up to the Roman emperor.” Indeed, Isis fighters, after seizing Palmyra, released a video showing the temples and colonnades at the ruins, a unesco World Heritage site, intact. “Concerning the historical city, we will preserve it,” an Isis commander, Abu Laith al-Saudi, told a Syrian radio station. “What we will do is pulverise the statues the miscreants used to pray to.” Fighters then set about sledgehammering statues and shrines.

Zenobia’s nemesis was the Roman emperor Aurelian, who led his legions through Asia Minor, reclaiming parts of the empire she had taken. Near Antioch, she met him with an army of seventy thousand men, but the Roman forces chased them back to their desert stronghold. During the siege of the city, Aurelian wrote to Zenobia, “I bid you surrender, promising that your lives shall be spared.” She replied, “You demand my surrender as though you were not aware that Cleopatra preferred to die a queen rather than remain alive.” Zenobia attempted to escape to Persia, but was captured before she could cross the Euphrates. Palmyra was sacked after a second revolt. Aurelian lamented in a letter to one of his lieutenants, “We have not spared the women, we have slain the children, we have butchered the old men.”

Some Arab sources adhere to the theory that Zenobia committed suicide before she could be caught. Gibbon follows Roman accounts that place her in Rome as the showpiece of Aurelian’s triumphal procession. “The beauteous figure of Zenobia was confined by fetters of gold; a slave supported the gold chain which encircled her neck, and she almost fainted under the intolerable weight of jewels,” he writes. The grand homecoming apparently elicited a snarky response from the commentariat. According to the “Historia Augustus,” Aurelian complained, “Nor would those who criticise me, praise me sufficiently, if they knew what sort of woman she was.” Instead of beheading her in front of the Temple of Jupiter, once a common fate of renegades, he awarded her a villa in Tivoli. The historian Syncellus reported that she married a Roman senator; their descendants were listed into the fifth century. She is said to have died in 274 AD in Rome.

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204)

Eleanor was a formidable Queen twice over – first as Queen of France, then of England! Her father William X died in 1137, leaving Eleanor to inherit his titles, lands and enormous wealth at just 15. Suddenly one of France’s most eligible bachelorettes, she married Louis, son of the French King, and not long after became Queen of France, still in her teens.

Famously fierce and tenacious, Eleanor exerted considerable influence over Louis, and accompanied him on the Second Crusade of 1147-49. After their marriage was annulled in 1152, she stayed single for just two months before marrying the heir to the English throne Henry Plantagenet, and in 1154 they were crowned King and Queen of England. Eleanor took a leading role in running the country, directing church and state affairs when Henry was away, and travelling extensively to consolidate their power across England. This was all while raising eight children, and finding time to be a great patron of courtly love poetry!

Eleanor and Henry separated in 1167, and after Eleanor sided with her children over Henry during a revolt, she became Henry’s prisoner. She was held under house arrest for over a decade, and it was only in 1189 after Henry died and her son Richard the Lionheart became king that Eleanor was freed.

By now a widow in her 70s, instead of retiring to a quiet life away from court politics, Eleanor became more badass than ever. While Richard was away on crusade she took a leading role once again in running the realm and fending off threats of attack, and when he was taken hostage by the Duke of Austria she personally collected his ransom money and travelled to Austria to deliver it and ensure his safe return to England.

After spending many of her final years criss-crossing France and Spain on diplomatic and military missions, Eleanor died in 1204 at a monastery in Anjou. The nuns there described her as a queen ‘who surpassed almost all the queens of the world’.

Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603)

Elizabeth I is one of my favourite Queens of all time. She reigned for 45 years and is well remembered for her defeat of the Spanish Armada, her progresses, her economic policies, and her patronage of the arts – as well as her virginity. The history books talk much of her make-up and spinsterhood, but there is no doubt that she was one of the most badass monarchs England ever had.

Elizabeth’s early life did not start well. By the age of three, her father had had her mother executed, and Elizabeth had been deemed illegitimate. Nonetheless she was given a rigorous education. One tutor even noted that her mind showed “no womanly weakness”. She excelled at Greek, Latin, French and Italian, as well as theology – knowledge that would equip her for diplomatic leadership so necessary in later life.

In 1554, under the reign of her devout Catholic sister Mary, Elizabeth became the focus of a Protestant rebellion. She was arrested and sent to the Tower of London, but was found innocent and escaped with her life a few months later. Her true commitment to the reformed church was only openly revealed upon her accession to the throne.

Indeed, as Queen Elizabeth promptly expressed her support for the Protestant church, and yet her reign is celebrated for bringing relative religious stability to the country. She adopted a policy to not “make windows into men’s souls”, which allowed for a margin of freedom beyond that of the monarchs before her. Her astute appointment of ministers and officials along with careful housekeeping also led to a period of relative economic stability, which in turn allowed for the arts to flourish during this time. Elizabeth attended the first performance of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and appointed the acclaimed miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard as a court painter.

Elizabeth’s choice not to marry was radical (and wholly understandable given her monster for a father and abusive step-father.) Yet, throughout her reign the expectation remained that she would find a husband and give birth to an heir. Instead, the Queen used her ‘eligible bachelor’ position as a political tool, while creating an image of herself as married to the nation. Her popularity with her subjects and her own self-styled image as Gloriana made Good Queen Bess into a legendary figure; today, she has been portrayed in more films and television shows than any other British monarch.

Her most amazing achievement is the fact that her name defined a chapter of Western history so that even today we talk of Elizabethan era. A feat matched only by Queen Victoria to define the 19th Century.

Tomoe Gozen

When I was living in Japan as a child I began to appreciate Japanese history. I also took an interest in the Japanese martial arts as well as being thrown in at the deep end to struggle to learn the language. So as an outsider I was happy to discover that Japanese women were not always demure and subservient or even passive witnesses to history. Some even made it. Outsiders don’t truly know how some Japanese women had shaped their own destiny as well as their country’s within the constraints of the rigid social structures of Japanese society. Contrary to what many think there were indeed female samurai. Not many but one or two who became the stuff of legend and lore.

The most famous onna-bugeisha (female samurai) in Japanese history was Tomoe Gozen. Gozen was a title of respect bestowed on her by her master, shogun Minamoto no Yoshinaka. She fought alongside male samurais in the Genpei War, which lasted from 1180 to 1185. While a woman fighting among men was highly unusual, it seems Yoshinaka's high esteem for Tomoe and her fighting skills overcame prejudice.

In the history tome The Tale of Heike, Tomoe was described as "a remarkably strong archer, and as a swordswoman she was a warrior worth a thousand, ready to confront a demon or a god, mounted or on foot." She was also said to be beautiful, fearless, and respected.

Her hobbies included riding wild horses down intimidatingly steep hills. She regularly led men into battle and to victory. Her last was the Battle of Awazu, where Minamoto no Yoshinaka was killed. Tomoe escaped her enemies there, and gave up her sword and bowed to retirement. From there, some say she married. Years later, when her husband died, it's believed Tomoe became a nun.

Nakano Takeko

The other known onna-bugeisha (female samurais) in Japan's history, Takeko was educated in literary and martial arts before distinguishing herself in the Boshin War, a Japanese civil war that lasted from January 3rd May 1868 to 18th May 1869.

In the Battle of Aizu in the fall of 1868, she and other females who chose to fight were not recognised as an official part of the Aizu army. Nonetheless, Takeko led her peers in a unit that was later dubbed Jōshitai, which translates to the "Women's Army." Her weapon of choice was the naginta, a Japanese pole arm. But while it helped her earn glory, it would not safeguard her through the war.

Takeko was shot in the chest while leading a charge against the Imperial Japanese Army of the Ogaki domain. Fearing that her enemies would defile her body and make her head a gruesome war trophy, she asked her sister to cut it off and bury it. This was her final wish, and her head was subsequently buried beneath a pine tree at the Hōkai-ji Temple in modern-day Fukushima. Today, a monument to her stands nearby, where girls come each year to honour her and her Women's Army during the Aizu Autumn Festival.

Laxmibai, the Rani of Jhansi (1828-1858)

Laxmibai would have made any of warrior women of Classical antiquity proud. She was the last of the true warrior queens. The fact she was Indian and bitterly fought the British to the death doesn’t deter me from admiring her hugely in the same way the British still admire Joan of Arc.

Like many other families scattered across the British Empire, my family lost brave relatives who died during the tragic Indian Mutiny of 1857 (the Indians call it the First War for Independence). But however ugly and bloody that chapter of British imperial history was, I find myself in awe of the life of Laxmibai, the Rani of Jhansi.

When as a family we moved to India I learned a little about her from Indian school friends. I learned a lot more from a couple of Indian officer cadets at Sandhurst (Sandhurst takes in officer cadets from the Commonwealth and other countries) with whom I struck an affable friendship because I could speak Hindi and we used to watch Bollywood movies with our platoon mates. Laxmibai is every bit as remarkable as Jeanne d’Arc and much more. I can say I am humbled when I try to retrace her steps of her life when I visit India from time to time.

By the time Laxmibai (or Lakshmibai) was a teenager, she had already violated many of the expectations for women in India’s patriarchal society. She could read and write. She had learned to ride a horse and wield a sword. She talked back to anyone who tried to tell her to live her life differently. But where those spirited ways might have been scorned in another young Indian woman, they would prove to serve her well as she went on to leave an indelible mark on Indian history.

In the mid-19th century, what became the modern nation of India was dotted with hundreds of princely states, one of which, Jhansi, in the north, was ruled by Queen Laxmibai. Her reign came at a pivotal time: The British, who were expanding their presence in India, had annexed her realm and stripped her of power. Laxmibai tried to regain control of Jhansi through negotiations, but when her efforts failed she joined the Indian Rebellion of 1857, an uprising of soldiers, landowners, townspeople and others against the British in what is now known as India’s first battle for independence. It would be 90 years before the country would finally uproot the British, in 1947.

The queen, or rani, went on to train and lead her own army, composed of both men and women, only to perish on the battlefield in June 1858. In the decades that followed, her life became a subject of competing narratives. Indians hailed her as a heroine, the British as a wicked, Jezebel-like figure. But somewhere between these portrayals she emerged as a symbol not just of resistance but of the complexities associated with being a powerful woman in India.

Laxmibai wasn’t of royal blood. Manakarnika, as she was named at birth, is widely believed to have been born in 1827 in Varanasi, a city in northeast India on the banks of the Ganges River. She was raised among the Brahmin priests and scholars who sat atop India’s caste system. Her father worked in royal courts as an adviser, giving her access to an education, as well as horses. In 1842, Manakarnika married Maharaja Gangadar Rao, the ruler of Jhansi, and took on the name Laxmibai. (It was — and, in some parts of the country, still is — a common practice for women to change their names after marriage.)

By most accounts she was an unconventional queen, and a compassionate one. She refused to abide by the norms of the purdah system, under which women were concealed from public view by veils or curtains. She insisted on speaking with her advisers and British officials face to face. She wore a turban, an accessory more common among men. And she is said to have trained women in her circle to ride and fight. She attended to the poor, regardless of their caste, a practice that even today would be considered bold in parts of India. While she was queen, the powerful British East India Company was beginning to seize more land and resources. In 1848, Lord Dalhousie, India’s governor general, declared that princely states with leaders lacking natural born heirs would be annexed by the British under a policy called the ‘Doctrine of Lapse’.

Laxmibai’s only child had died, and her husband’s health was starting to deteriorate. The couple decided to adopt a 5 year-old boy to groom as successor to the throne, and hoped that the British would recognize his authority despite the declaration. “I trust that in consideration of the fidelity I have evinced toward government, favour may be shown to this child and that my widow during her lifetime may be considered the Regent,” her husband, the maharaja, wrote in a letter, as quoted in Rainer Jerosch's book, “The Rani of Jhansi: Rebel Against Will” (2007). His pleas were ignored. Soon after he died, in 1853, the East India Company offered the queen a pension if she agreed to cede control. She refused, exclaiming: “Meri Jhansi nahin dungee” (“I will not give up my Jhansi”) - a Hindi phrase that to this day is etched into India’s memory, stirring up feelings of pride and patriotism.

Beyond Jhansi’s borders, a rebellion was brewing as the British imposed their social and Christian practices and banned Indian customs. The uprising spread from town to town, reaching Jhansi in June 1857. Dozens of British were killed in the ensuing massacre by the rebels. The British turned on Laxmibai, accusing her of conspiring with the rebels to seek revenge over their refusal to recognize her heir. Whether or not she did remains disputed. Some accounts insist that she was wary of the rebels and that she had even offered to protect British women and children during the violence.

Tensions escalated, and in early 1858 the British stormed Jhansi’s fortress.

“Street fighting was going on in every quarter,” Dr. Thomas Lowe, the army’s field surgeon, wrote in his 1860 book “Central India During the Rebellion of 1857 and 1858.” “Heaps of dead lay all along the rampart and in the streets below….Those who could not escape,” he added, “threw their women and babies down wells and then jumped down themselves.” As the town burned, the queen escaped on horseback with her son, Damodar, tied to her back.

Historians have not reached a consensus on how she managed to pull this off. Some contend that her closest aide, Jhalkaribai, disguised herself as the queen to distract the British and buy time for her to get away.

In the end, the British took the town, leaving 3,000 to 5,000 people dead, and hoisted the British flag atop the palace. Left with no other options, Laxmibai decided to join the rebel forces and began training an army in the nearby state of Gwalior.

The British troops, close on her heels, attacked Gwalior on a scorching summer morning in June 1858. She led a countercharge — “clad in the attire of a man and mounted on horseback,” the British historians John Kaye and George Malleson wrote in “History of the Indian Mutiny” (1890) — and was killed. However accounts differ on whether she was stabbed with a saber or struck by a bullet. It was the last battle in the Indian Rebellion.

“The Indian Mutiny had produced but one man,” Sir Hugh Rose, the leader of the British troops, reportedly said when fighting ended, “and that man was a woman.”

The violence left thousands dead on both sides. The British government dissolved the East India Company over concerns about its aggressive rule and brought India under the control of the Crown. It then reversed Lord Dalhousie’s policy of annexing kingdoms without heirs.

Today, Queen Laxmibai of Jhansi has been immortalised in India’s nationalist narrative. There are movies, TV shows, books and even nursery rhymes about her. Streets, colleges and universities are named after her. Young girls dress up in her likeness, wearing pants, turbans and swords. Statues of her on horseback, with her son tied to her back, have been erected in many cities throughout India.

And, almost a century after her death, the Indian National Army formed an all-female unit that aided the country in its battle for independence in the 1940s. It was called the Rani of Jhansi regiment.

There are plenty of other women that one could write about of great women leaders who while not on the front line of battle did lead their countries to greatness or skilfully pulled the strings from behind the throne. History is littered with many examples.

What metrics we determine to define ‘greatness” is very much in the eye of the beholder. It’s not a matter of masculine or feminine virtues - although they are important in their own way. Above all I would say what makes a leader great is character.

There is no ‘weaker sex’ - that would be a terribly unfair slur on our men.

I’m joking of course. But my point stands. I don’t believe it’s about who is the weaker sex. But let’s talk of character instead.

Character defines the essence of leadership. I say this because I often encounter a perception among women that they need to become more like men to be considered equal to them. Nothing could be further from the truth. What makes you uniquely who you are as a woman is highly important.

We are all called to become the best versions of ourselves, and as women, we don’t do that by trying to be more like men. It would be a mistake to put one’s heroines on a pedestal because they are all flawed and have feet of clay - just like men. Character knows no gender. Character is virtuous. Character is rising to greatness despite one’s flaws.

As early as the 1300s, Catherine of Sienna wisely said, “Be who you were created to be, and you will set the world on fire.” More than 500 years later, Oscar Wilde reiterated that notion: “Be yourself, everyone else is already taken.”

So be the best version of yourself.

Thanks for your question.

#question#ask#warrior#women#femme#leadership#history#military history#heroines#napoleon#alexander#personal

105 notes

·

View notes

Photo

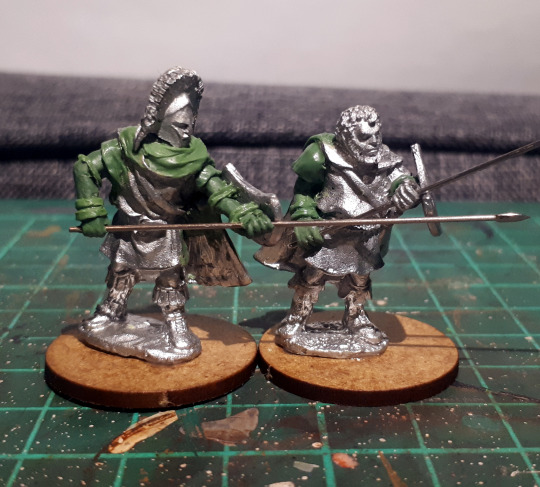

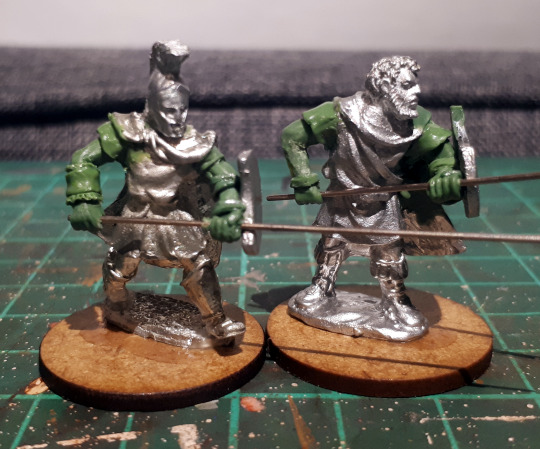

Back to actual hobby, not business, stuff: Thracian spearmen. Long-winded historical nonsense under the cut.

Reading about the ancient Thracians you often come across the idea that they had quite an influence on the military thinking of their Greek neighbours, particularly the Macedonians. Most people are familiar with the idea that Thracians introduced peltasts to Greece, but the most eye-catching idea that crops up is that Thracian spearmen may have inadvertently inspired the Macedonian pike phalanx, either through the infantry reforms of an Athenian general called Iphicrates who was, in turn, inspired by Thracian tactics ~or~ through Philip II getting stabbed in the leg by an anonymous Triballi spearman while campaigning in western Thrace. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

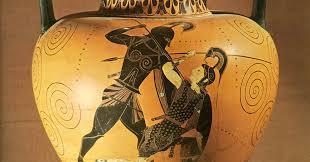

Anyway, there doesn’t seem to be anyone making miniatures that reflect any similarity between Macedonian phalangites and Thracian spearmen. Fortunately, ancient Greek pottery artists were on the case!

These images are a teeny bit frustrating to the modern-day model-making type because they don’t show what’s going on with the interior side of the shield, but you can clearly see these Thracians adopting a very unusual underarm grip with their spears (by contrast, hoplites in combat are pretty much always depicted using their spears overarm) and it would be plausible (not certain!) for the shield hand to be used as a second grip on the spear because the pelte is light enough to be strapped to the arm. So that’s what I’m trying to make here.

#thracians#peltasts#spearmen#Historical Wargames#ancients#hail caesar#impetus#dba#a little bit of history#wip#macedonians#philip II#iphicrates

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Here’s scenario I spun a while back on the Constructed Languages list serve:

Philip of Macedon isn’t assassinated. As Hegemon of the League of Corinth, he invades the Achaemenid Empire. Under the command of Alexander, the invasion is successful.