#august in the water

Text

august in the water (1995, dir. gakuryū ishii)

(available on archive.org)

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

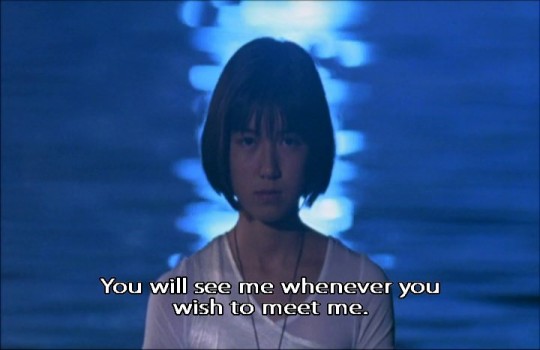

August in The Water dir. Gakuryū Ishii (1995)

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

August in the Water (1995) directed by Gakuryu Ishii

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

august in the water (1995) movie poster, dir. sogo ishii, photo by norimichi kasamatsu.

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

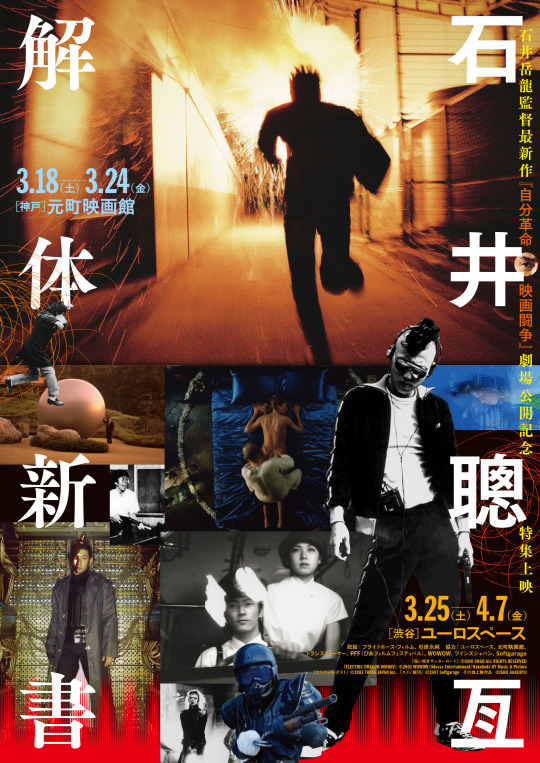

Special Screening Sogo Ishii Kaitai Shinsho

I wish I could go and see Angel Dust in 35mm

#sogo ishii#gakuryu ishii#石井 聰互#石井 岳龍#japanese film#Japanese Directors#cinema#film#movies#movie director#chirashi#angel dust#electric dragon 80000v#labyrinth of dreams#august in the water#burst city

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hazuki Izumi (Reno Komine) stands on the edge of a rooftop looking out at the city beneath her. A clutter of competing architecture styles and buildings at various points of development: scaffolding, newly-built, maturing, declining, abandoned, condemned. Traffic lights glow, cars drone, and roads curve. A web of powerlines connects every part of the city. Hazuki is deep in thought, contemplating something or other, almost as if she’s listening to something we can’t quite hear. Her friend Mao (Shinsuke Aoki) notices the rooftop figure and approaches her as he becomes concerned that she might jump.

This scene takes place in August in the Water (1995) but variations of it can be found in a number of Japanese films and anime of the late 1990s to early 2000s. At the time of release these films and series belonged to different genres and production cycles yet retrospectively we can identify a fascinating pattern of imagery, themes, characters and even locations that recur to form an enigmatic genre called denpa. Little has been written about it in English, so allow me to venture forward.

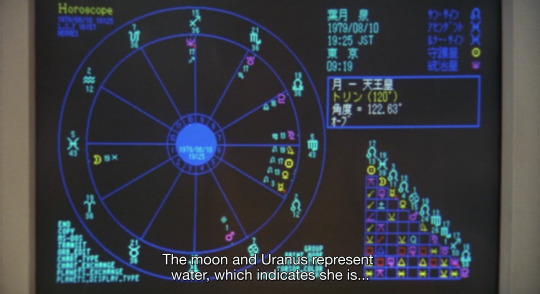

‘Denpa’ is a Japanese word that means electromagnetic wave or radio wave. Within the genre, characters tune into these waves and feel their effects: they sense things, hear voices and see spectres, indeed the stories of Chiaki J. Konaka begin this way, including his Lovecraft-inspired psychological horror Serial Experiments Lain (1998) and Marebito (2004). The characters are susceptible to the waves due to alienation caused by their oppressive surroundings which is depicted through a distinct, industrial aesthetic: antennas, chain link fences, telephone poles, a web of powerlines across the sky, trains, manholes and sewers, grainy and distorted footage, a muted colour palette. This imagery reoccurs across denpa fiction, from the visionary anime of Satoshi Kon (Perfect Blue 1997, Paranoia Agent 2004) to the live-action poetry Shunji Iwai crafts out of adolescent cruelty (Picnic 1996, All About Lily Chou-Chou, 2001).

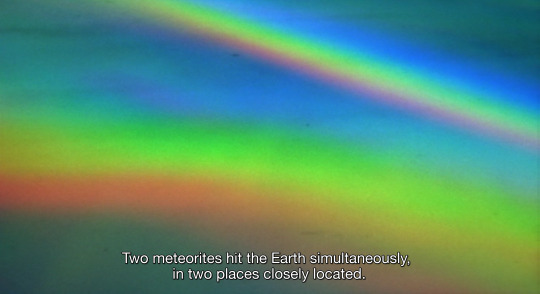

These bleak,alienated urban settings raise questions of tradition vs modernisation, mass-communication and a critical look at new technologies. Denpa situates these themes amongst references to folklore and the paranormal such as ESP, hauntings, aliens and spirits a combination explored by both the cult horror favourite Boogiepop Phantom (2000) and influential franchise starter Ring (1998). These supernatural beings are known to inhabit different realms and through electromagnetic waves these beings can cross over to our world, and humans can cross over to their worlds. The blurred lines between these spaces are illustrated with surreal imagery and experimental filmmaking. Such creative innovation can be found in the surreal psychological torment of Hideaki Anno (Neon Genesis Evangelion 1995-7, Love & Pop 1998, Ritual 2000) and in the breath-taking urban dreamscapes woven by Gakuryu Ishii (August in The Water, 1993’s Tokyo Blood). Within this cocktail of urban alienation and supernatural forces are plot points such as rumours, conspiracy, mental illness, and delusion often with cosmic and apocalyptic consequences, best embodied by the hypnotic horror of Kiyoshi Kurosawa (Cure 1997, Pulse 2001).

So far, denpa has only appeared as a loosely defined genre label on English-language databases for anime and videogames, on the occasional blog post, a handful of letterboxd lists and one lone essay [1]. It is at once both recognisable yet hard to define. I understand it on an emotional level, I can identify it as a vibe, yet I want to tease out the details and define it in more concrete terms: what makes something ‘denpa’?

The genre derives from ‘denpa-san’ or ‘denpa-kei’ a name for a type of person that emerged in the late 20th century. Think of denpa-san as analogous to ‘tin foil hatter’ – someone vulnerable to paranoia, conspiracy theories and delusions hoping that the foil will block out those invasive electromagnetic waves. Or maybe they’re already at their mercy, following instructions heard via the waves and doing unsavoury or even dangerous things. The term initially hit the mainstream consciousness in association with the 1981 ‘Fukugawa Street Murders’ where a 29-year-old man indiscriminately stabbed passers-by, killing several people and injuring more. The highly-publicised trial hinged on the controversial defence of insanity: the perpetrator argued that they were driven to murder after years of torment from electromagnetic waves [2]. Over time the term expanded to become associated with creepy, unpopular people in general, those on the fringes of society with unusual quirks and obsessions.

It is here that the term overlaps with another: ‘otaku’. A social outcast who obsesses over a hobby to the detriment of their social life. Think ‘geek’ but usually uttered with more contempt. Otaku is typically associated with anime, but contrary to popular belief can be about many subjects from videogames to cars. What ties them together is the negative effect it has on the self. Much like denpa, the term otaku gained traction in association with a horrific crime; in the 1990s it was elevated from merely a pejorative label to the centre of a moral panic in relation to the years-long trial of a serial killer nicknamed by the media as ‘the otaku killer’ for his extensive video collection of pornography and horror films [3]. In the years since, the collective otaku have shaken off the worst of these associations and become a phenomenon as they developed a distinct culture and became a major economic force that has been embraced by the media they obsess over. On the darker end of the subculture some favour the fantasy world of their hobby over the real world and get lost in it, which in itself has become a common denpa narrative with an iconic example being the idol otaku in Perfect Blue.

Critics ascribe the emergence of denpa-san and otaku to society at the time. The Japanese economic bubble burst in 1991 and the decade that followed became known as ‘The Lost Decade’. The population faced a recession which stunted young people as they came of working age. And yet Japan was known on the global stage to be at the forefront of home electronics and new technology. This was in tension with traditions of the past and complicated their national identity as new cultural connotations outpaced traditional ones posing the question: can an old culture survive as a new one emerges?

The development of these new technologies also introduced new issues as they quickly became part of everyday life. Camcorders in every hand, phones in every pocket, so easy to use that soon everyone had one without knowing how they really worked. Life was changing as there was now constant recording, growing access and intimate conversations were now held not in person but via phones and on internet forums. As people became increasingly reliant on these technologies, people began to wonder, what is the existential cost of these new conveniences?

From moral-panics and national identity crises to new technologies denpa fiction responds to this new cultural landscape.

The war between tradition and modernization often forms the backdrop of denpa fiction in urban spaces where a dedicated few keep old customs alive, while others push on for progress. Gakuryu Ishii (previously known as Sogo Ishii) depicts the tension of this conflict well in August in the Water where participants of the centuries-old festival in Hakata pulse through the city in historical costumes with traditional matsuri floats surrounded by modern buildings and stopped traffic; Ishii finds strange beauty in the cityscapes that engulf and imprison his characters. Investigations lead Detective Takabe (Koji Yakusho) in Cure to abandoned buildings and disused factories which signal the failure of a once-promising industry. In Love & Pop and Tokyo Blood, supporting characters are construction workers who signify this changing landscape as they meet on noisy building sites that are the eyesore we must endure for another dubious future.

The rooftop is a recurring location for these films. It can be a place for a clandestine conversation with a confidante, or a place for solo contemplation. The sight of a lone person on a rooftop can be startling to passers-by: the threat of suicide looms and in denpa often does happen. Cinematographically speaking it’s an opportunity to view an urban vista: the buildings, antennas and powerlines that populate the skyline. Again and again characters are drawn to the rooftop where they can get the clearest signal to the electromagnetic waves that mesmerise and influence them.

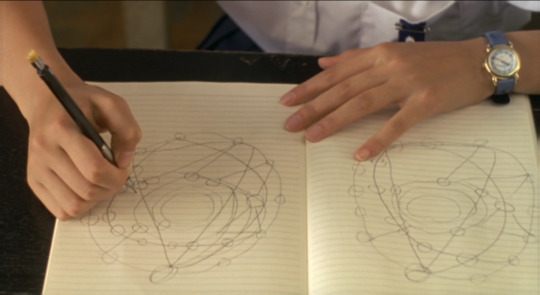

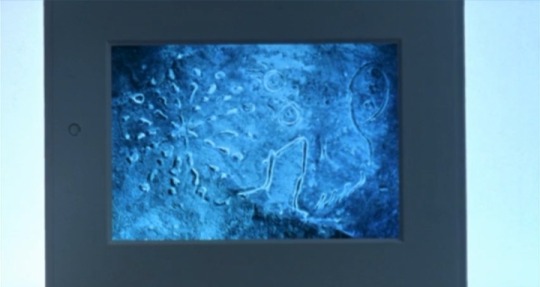

Alternatively, the clearest signal can be found by going right to the source. In Serial Experiments Lain we meet Lain’s father (Ryusuke Obayashi) at his impressive 6 monitor desktop and over the course of the series Lain’s (Kaori Shimizu) simple computer set-up evolves to be larger and larger. A soundscape is built from keyboard tapping, mouse clicking and monitors gently beeping. Denpa characters are often found hunched over a desk or workstation in the dark, the only light source being the glow of a screen or the small bulbs of a switchboard that gently whir as a pen scratches while detailed notes are being made. It’s an image with unhealthy connotations indicating obsession and someone losing touch with the outside world. In Boogiepop Phantom, the deskbound character is a videogame otaku finding solace in a fictional fantasy world. In Cure they’re a detective and in Ring a journalist whose respective investigations turn fanatical as they uncover disturbing histories. In each instance the foundations of their worldview will soon be shaken and their mental health questioned as conspiracies and paranormal explanations become more and more likely. Are the characters’ paranoid, or are they seeing things clearly for the first time?

These paranoid thoughts or deteriorating mental states are often heard through voice-over narration. Depending on the film the voice-over could be the trademark psychological introspection of Neon Genesis Evangelion, or the expansive philosophical musings of August in the Water or even the sinister and somewhat incoherent rambling of Marebito. Though superficially different, what they share is a painfully personal and poetic type of soliloquy.

Alongside narration, different psychological states are expressed through surreal imagery and experimental filmmaking, which often leads to a striking use of mixed-media with live-action moments in anime. In Boogiepop Phantom, a drug-addled videogame otaku experiences visions which are depicted by heavily edited live-action footage in a break from the traditional animation of the series. In Serial Experiments Lain there are animated character figures over live-action backgrounds which has the uncanny effect of blurring the lines between the different worlds that Lain traverses. In the case of Neon Genesis Evangelion: End of Evangelion, the sequence of live-action footage breaks the diegetic barrier between the text and audience, seeming to directly address not only the delusions of its’ characters but its own otaku fandom.

This subtle sense of self-awareness can be seen in the eerie experience of watching characters watching screens. Frames within frames or looking at a picture within a picture, voyeurism becomes infinite. New technologies allow people to see people through a thick glass lens or a pixelated screen. Distant yet paradoxically seeing each other more intimately than ever. In Perfect Blue this newfound intimacy fuels the obsessions and delusions of both Mima and her otaku fan.

The spectre of denpa is not limited to Japan. The same themes and same motifs can be found in English-language films from around the same time. There is Donnie Darko (2001), Richard Kelly’s film about a schizophrenic teenager who is told to commit crimes by a phantom in a rabbit suit and whose survival of a near-death-experience has apocalyptic consequences. You can find denpa in the films of M. Night Shyamalan: from the delusion of Bruce Willis in The Sixth Sense (1999), to the haunting image of mass rooftop suicides in The Happening (2008) and to the potent mix of aliens and religion in Signs (2002). Even in the music video of Eminem’s Stan (2000)– in which a disturbed otaku hunches over a desk under a perpetual raincloud. When I recognise denpa motifs in films made outside Japan, I begin to think of denpa less as a genre and more as a zeitgeist. A restless, nihilistic gen x moan of exasperation. That feeling of living in The Matrix (1999); groaning at the end of the century and looking to the new one with only pessimism. Yes, there are new technologies but there are as many negative possible outcomes as there are positive ones. It seems inevitable that people will succumb to their worst impulses.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

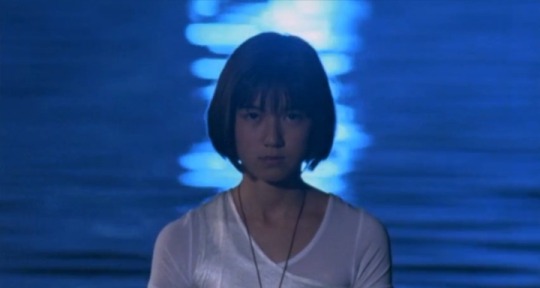

mizu no naka no hachigatsu / august in water, 1995

dir. gakuryu ishii

#august in the water#1995#gakuryu ishii#jmovie#japanese cinema#movie recommendation#asian cinema#japanese#japan

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

August In The Water (1995)

Been thinking about this one today. Dreamy, cozy, immersive, full of contrasting colors and ideas, and a deep longing for…something.

Desperately want to find a higher quality version of this movie. As is, you can watch it on YouTube in glorious 360p! (Downloads I found were of similar quality, but the subtitles seemed to have a slightly better translation…if you can find it)

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

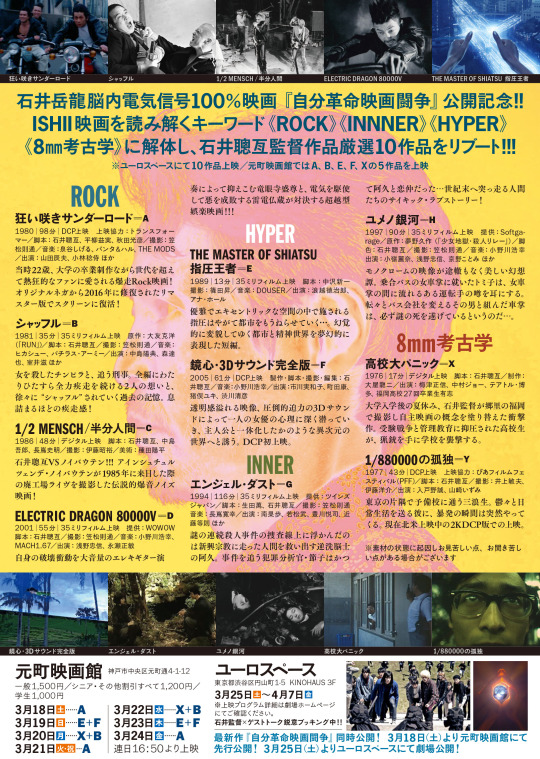

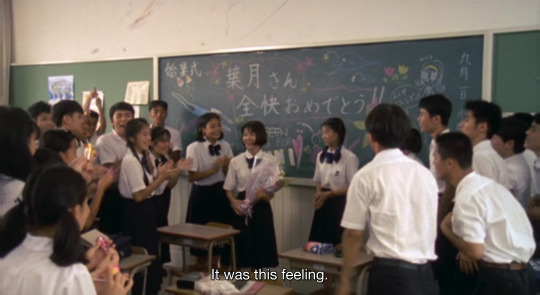

august in the water dir. gakuryū ishii

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

#undercurrent#still the water#august in the water#taste of emptiness#movie#movie posters#film poster#poster

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

August in The Water dir. Gakuryū Ishii (1995)

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

just watched august in the water!!!!!!! really cool movie!!!!!!!!!! not exactly amazing plot wise. not bad tho! i think its just very reminiscent of a certain sub-flavor of adolescent melancholy-iyashikei from it's time a la saikano and friendly ghost kana. a style of sad teens effected by things beyond them and impossible to understand with stakes as big as the world, changed irrevocably, and ending in death/transcendence with lots of quiet empty space and warm synth and whatnot. this doesnt mean the plot is bad but i think instead of blowing me out of the water i just put it next to other similar sorts of stories ive read/seen like it. which is an honor i think cus i rly enjoy those

3 notes

·

View notes