#before covid i was able to keep up w news and work on research projects and write multiple image descriptions every day and read books

Text

.

#meg talks#feeling really down and frustrated#ever since i caught covid over the new year ive just been doing so badly#it’s now halfway through may and not only am i having all sorts of weird new pain problems#to the point where i dragged myself to the er yesterday bc my usual meds didn’t do shit for me and i spent seven hours writhing in pain#but also mentally im just. constantly tapped out#before covid i was able to keep up w news and work on research projects and write multiple image descriptions every day and read books#and keep up w friends all while working full time#like even if i was in bed p much whenever i wasn’t at work i could still read and write and carry conversations#now it’s like i can only handle all of these things in small doses before my brain just shuts off#im still keeping up w news and describing what i can and working on my research projects and trying to make connections#but i feel so slow abt everything i do#it’s driving me up the wall#ive been trying for days to get through this one academic paper that’s rlly not even that long#and i just can’t do it. not for long anyway i have to read in small bursts#and then having to take muscle relaxants for these fucking spasms that make me really drowsy and sleep the whole day away…#idk. it might not even be abt covid i might be reading too much into it but it’s just pissing me off. thinking abt how nobody masks anymore#and how every time there’s a covid outbreak i won’t be able to properly protect myself or my brothers from it#bc of this fuckass job#idk im just tired and upset

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

been struggling real hard since the start of the year (2021, not academic year or whatever (although let’s be real the academic year as a whole has also been pretty bad)) and this culminated in me deciding to take a leave of absence from my research as of this week. I am already struggling to honor the things I was feeling that led me to this point, so here goes a diary post

first of all, I am increasingly convinced that I was just never really trained properly for the project I ended up working on. last year, prior to COVID shutdown, I was being trained on separatory techniques for carbon nanotubes. I was starting to independently push forward on new nanotube separations when COVID hit, and I spent all of shutdown reading papers about carbon nanotubes... But then when I came back to lab I was suddenly working on organic synthesis, which utilizes precisely zero of the skills I had been developing beforehand. There were a few reasons behind the change, and I initially gave it an ok when another grad student double-checked with me that I even wanted to do this new project, but what I didn’t realize at that time was that my in-lab mentor would not be able to help me with the majority of the work (basically she knew how to make one half of the molecule I wanted to make, but not the other half). that other half of the molecule turns out to be NOTORIOUSLY difficult to work with, and the only way to make any progress on it is to just work at such large scales that even a 5% yield is “good enough.” But no one working with me had the wherewithal (or cared enough) to tell me that, so all my newcomer enthusiasm died with months of failure trying to make that molecule.

so I’m working really long days, not really making anything other than “an earnest effort,” and then in November the most senior member of the lab who is a week away from defending his dissertation fucking loses it at me and one other second-year about how we are wasting time, etc, etc. We have since moved on from that as people, but it still sort of traumatized me and left me very very uncomfortable existing in that space. ended up feeling like I was under a microscope, any second not actively spent with my hands on something was a criminal offense, not eating/taking breaks... this was obviously not very sustainable and I ended up working even fewer hours, which made showing up at all even more agonizing, as I anticipated eventual future blowout. rinse and repeat. losing sleep and not getting anything done outside of lab with the anxiety of it all.

by January, I’m seriously losing it, and finally make a meeting with my advisor to try to explain things to him. I also disclose having ADHD and pin a lot of my struggle on “working on a treatment plan.” He is sympathetic and wants to help however he can, but I can’t think of anything he can do for me, so we leave things unfinished. A week later, he sets up a meeting with me (and two other second-years, all separately) to tell us we’re not spending enough time in lab, we are going to delay our prelim exams, and we’re now going to work one-on-one with a post-doc in the lab. While it was not very cool of him to do it the way he did, I actually did feel genuine relief at the time. Like maybe I would finally be able to fill in the gaps in my technical abilities with this change

HOWEVER, working with this post-doc was... not it. The first thing he suggested to me was to stick with one synthetic target (as opposed to the three I had in total), and just keep pushing on that front until it was done. This resulted in me making intermediate, purifying it, trying the next step in the synthesis, having it fail, and having to go back and make more intermediate OVER AND OVER AGAIN for weeks. It was about this time that I started uncontrollably weeping in the lab on a daily basis. (side note: the corner of lab I work in is pretty thinly populated, so no one ever saw me cry despite weeks of this going on! hooray isolation!) oh, and let’s not forget that the second-years are all TAing this semester, which conveniently chops of my schedule beyond the point of usefulness.

last week, I suddenly felt like this just wasn’t worth it anymore. could not even recognize what “it” was that was supposed to be worth it all along. professorship is a) extremely rare, b) very arduous to attain, with possibly a decade or more of grueling research, and c) possibly not even the dream job I thought it to be, once attained. I was thinking about how my husband is a fucking lawyer and can provide for us if needed. I was thinking about how this is the only life I get to live and I can’t justify spending over a decade of it literally tormenting myself and inhaling/pouring carcinogens on myself with no real promise of substantial payoff. spent all day Friday talking things out with senior lab members (actually the same guy who screamed at me in November, he’s an odd one), as well as the director of graduate studies. I resolved to get back on nanotube work, and just try to better manage my stress by getting support from others... by Sunday when I met with my advisor again, I had convinced myself that “I have all the resources I need to succeed, I just need to utilize them.”

Monday, I met with my psychiatrist, who literally asked me why I wanted to be in grad school at all. I floundered and said something vacuous, and she kinda nodded then prescribed me Prozac. I also spent Monday and Tuesday trying to get back into nanotube work, but by midday Tuesday I was already feeling the dread creeping in... and my threshold for adversity was just nil at that point, I guess, because I literally went and found both my the senior people I was working with and just flat out told them I quit. My friend helped me pack up my desk that day, and I was out the door by 3:30. Emailed my advisor after I got home. by the end of the day, I rationalized that the “precipitating event” was realizing that I don’t want to be on antidepressants, since I’ve been down that road before, and that this is not worth that.

so, spending the last couple of days talking to others and thinking about what to do next, I still don’t have an answer. everyone’s first piece of advice was to find some masters-level industry job, but right now I still feel too close to it to even see myself doing chemistry at all, or a 9-5 at all. like, part-time tutoring is the most I can entertain in my mind right now. but I know it’s better to keep the door open, and my advisor is still SOMEHOW my #1 fan, so this is just a leave of absence for the time being. the details of that will be hammered out once I meet with the director of my program, but right now I know I’ll continue my TA work (since I hope I’ll get to still be paid) and I’ll finish the class I’m taking since my advisor told me the whole grade is just going to be some 30 minute presentation at the end of the semester, and I am pretty sure I can pull that off rather than end with a W on my transcript.

the main things for me to figure out are: (1) do I want to pull together a non-thesis master’s defense in the next month, to secure a master’s in case I decide not to return after my leave of absence? (2) do I feel that a leave of absence will make a difference at all? Will coming back to the lab after some time away resolve the problems I’ve been having, or will it all just build up all over again? and (3) do I still want a Ph.D-dependent career? What do I even want to do?

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://techcrunchapp.com/trumps-america-first-presidency-all-but-ended-us-global-leadership-the-world-was-outgrowing-it-anyway/

Trump's America First presidency all but ended US global leadership. The world was outgrowing it anyway

But the global instruments Trump deserted haven’t crumbled, nor is the world crashing and burning with its long-time leader in the back seat. Strongman leaders may be emboldened, but they aren’t going entirely unchallenged. And old US allies have not fallen straight into the arms of China, as many analysts fear.

Instead, the world is adapting these agreements, it’s reshaping its institutions and, as for China, most countries are finding ways to balance their relations with Beijing as both a friend and foe.

This shift has been a long time coming. While US grand strategists who believe American world leadership is exceptional argue it could go on in its role indefinitely, most international relations experts agree that all unipolar models must come to an eventual end, as other powers rise and challenge its primacy.

After assuming the role of leader following World War II, the US proved its dominance with its victory in the Cold War, a consolidation of power that experts described as a “unipolar moment.” That moment has lasted 30 years.

There have been clear signs over the past two decades, however, that Americans are tiring of taking on this role, while much of the world, equally, is cooling on the US as its hegemon, and is eager to step into its shoes.

Germany, for example, is pitching itself as a global health leader. Even before the pandemic, German Chancellor Angela Merkel had put global health on the agenda at G20 meetings for the first time as the Trump administration showed signs of retreat from international cooperation. Germany has boosted funding for health research and development, and was even able to treat patients from neighboring countries for Covid-19 early in the European outbreak, so well-resourced were its hospitals at a time of crisis.

As the US attempted to lead reforms of the World Health Organization — despite its decision to abandon it — Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron proposed their own an alternative plan, after rejecting Washington’s, as Reuters reported.

Germany has pledged an extra 200 million euros ($234.1 million) to the WHO this year, making for a total of 500 million euros, to help plug the gap left by the US, traditionally the organization’s biggest donor. It’s not the only one. The UK announced last month it would boost its WHO funding by 30% over the next four years, which would make it the biggest donor, should the US follow through with its withdrawal.

China, under international pressure to resource the global response, has also pledged additional funding, as has France, Finland and Ireland, among others. It’s unclear whether they will be able to make up for the US’ shortfall in the years to come, but it’s at least a good start.

Merkel — often described as the world’s “anti-Trump” — said in May she wanted the European Union to take on more global responsibility for the pandemic and for the bloc to harness a more powerful voice overall on the values of “democracy, freedom and the protection of human dignity,” describing cooperation with the US as “more difficult that we���d like.”

Making comments in a speech ahead of Germany assuming the six-month presidency of the European Union, Merkel said she saw her country’s presidency as an opportunity to be an “anchor of stability” in the world that could shape change and assume responsibility for global peace and security.

“Itself a project between individual states, the European Union is inherently a supporter of rules‑based multilateral cooperation. This is truer than ever in the crisis,” Merkel said.

Macron too tried to pitch himself as the next leader of the free world in the earlier days of Trump’s presidency. His campaign lost steam, but he still often plays the democratic defender in the room where the US is missing, having confronted Russia’s Vladimir Putin on his country’s role in the Syrian conflict and on the deterioration of gay rights in Russia, and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman on the murder of his critic, Jamal Khashoggi, at a Saudi consulate in Turkey.

While EU leaders’ will to replace American leadership is strong, the lack of progress in the areas Macron has tried to address are a sobering reminder of the limited power the world has to uphold democratic values without the United States at the helm.

Putin had his wrist slapped, but the abuse of gay Russians continues, and Russia and its firepower has all but won the war for Syrian President Bashir al-Assad. Bin Salman has been forced to keep a lower profile, but Macron’s confrontation has done little to threaten his position of power.

The European Union is also losing its battle with the rise of autocracy in some of its eastern states, like Hungary and Poland, or countering Russian influence in that part of their bloc.

But they continue to try and their own alliances are strengthening. Take the E3. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson should be Merkel’s and Macron’s worst enemy, as tense Brexit trade talks crash out ahead of the UK’s December 31 withdrawal from the EU. Remarkably, the three are still chummy on topics other than Brexit.

The E3’s whole raison d’etre has been to counter US foreign policy, coming together informally during the Iraq war and to engage Iran on nuclear proliferation where the US wouldn’t. But it has become tighter knit in the Trump era — the trio have openly opposed US sanctions on Iran and increasingly cooperate in areas like Beijing’s territorial expansionism in the South China Sea and the Syrian conflict as the US shows less interest in those security challenges.

Members of the trans-Atlantic defense alliance, NATO, have also had to adapt to a less present US. The alliance has had plans to boost funding since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, an audacious move that the Obama administration did little about. Trump’s aggressive criticism of member nations contributing below their commitments of 2% of GDP applied further pressure on several members to pay their share.

A long time coming

There may be no easy replacement for US leadership, but Scott Lucas, a professor of international politics at the University of Birmingham, points out that Washington hasn’t achieved many of its recent international security objectives, either. “Asia, the Middle East, Africa, in many parts, disorder continues to a great extent,” he said.

The list of US failures in international security is long. The US hasn’t been able to build legitimate states in Iraq and Afghanistan, as it sought to. Israelis and Palestinians are no closer to peace deal. Both Iran and North Korea have developed nuclear weapons. The US hasn’t prevented Russia from exerting influence in Eastern Europe. It hasn’t convinced China to end its military aggressions in Asia. These were all true before Trump’s rise.

Lucas said that the Trump presidency hasn’t really been the turning point in this shift. President George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq was the “critical moment.”

“A lot of countries were discomforted, to say the least. They felt the war wasn’t justified — countries like France, Germany, Australia — that a unipolar America with the UK tagging along wasn’t working, especially when Iraq turned so horribly wrong, with so many people dying, and the instability that continues. So, the notion that the US leads and everyone follows was shot,” Lucas said.

Some experts say China is the only real contender here, and that a bipolar world in which the US and China compete is inevitable. Like in the Cold War, other countries will be forced to choose sides.

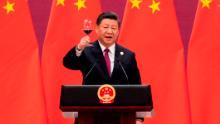

China too is finding areas in which to assert its growing power on the world stage with an increasingly absent US. At the UN General Assembly in September, Chinese President Xi called for the world to “join hands to uphold the values of peace, development, equity, justice, democracy and freedom shared by all of us.” In contrast, Trump devoted much of his speech to attacking China over its handling of the coronavirus, playing to his supporter base at home ahead of the November election.

Xi’s comments need to be taken with a grain of salt — Beijing has also taken elements of Trump’s presidency as an opportunity to vindicate its own heavy-handedness at home, in Hong Kong, for example, with its draconian national security law. But Xi does have a genuine appetite to be welcomed as a world leader, a role that will require him to conform somewhat to the rules-based order.

In the same speech in September, Xi made a pledge for China to become carbon neutral by 2060, an ambitious goal that has been met with both excitement and skepticism. Critics point out that China “off-shores” its carbon emissions, largely through its multi-trillion dollar Belt and Road Initiative, which includes development projects across more than 120 countries.

But Beijing is looking at ways to make these development endeavors more sustainable, and Xi’s announcement at least shows that China, the world’s biggest carbon emitter, is willing to lead and engage with the world on this crucial issue, where the US, the second-largest emitter, is not.

Shaun Breslin, a professor of politics and international studies at the University of Warwick, disagrees that the long-term future is necessarily a bipolar one where countries must choose sides between a competing China and US. Instead, he thinks the transition from a unipolar world will be “messy” and more likely give way to clusters of power.

“My problem with poles is we’re trying to use language from a different era and wedge the current era on that linguistic basis. What I think we’ll see is looser constellations of power and interests dependent on specific issue areas,” he said.

The world will see countries continuing to engage China in areas like trade and technology, but not necessarily replacing Washington with Beijing on issues like security or moral leadership. In many ways, that shift has already happened.

Democratic candidate Joe Biden is among those who believe the US should continue to lead. Though he has promised to rejoin institutions like the WHO and the Paris climate accord should he win on Tuesday, he won’t be able to reverse every foreign policy decision Trump has made.

For instance, it will be difficult for Biden to invest the troops and weapons needed to regain the influence the US once had in Syria. He may also find the US’ former Kurdish allies unwilling to work with him, having for years fought alongside the US to defeat ISIS, only to be abandoned last year as Trump gave Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan the green light to invade their territory in a quick phone call.

Biden’s comments during a debate last week on North Korea also suggest he may have no policy that differs from Obama’s, which did little to deter the pariah state.

Regardless of who wins the vote, the US’ role in the world has changed profoundly. Returning to where it was four years ago won’t be easy. Returning to its post-Cold War primacy is near impossible.

0 notes

Photo

Consumer Guide / No.98 / American television, film and stage actress, Bernadette Quigley with Mark Watkins.

MW : What’s new?

BQ : Currently, work is sparse as most of my businesses have been shut down because of the COVID-19 pandemic. No films or television shows are being shot in NYC at this moment in time and most of my side businesses are on pause as well. This season’s gardening work didn’t happen at all (because NYC had not yet deemed gardening an essential service).

Thankfully, I have a few coaching (acting) clients I work with often and I had one job before this pandemic hit that I’m still working on - a press and radio campaign for Irish singer-songwriter Ultan Conlon’s beautiful new record, ‘There’s a Waltz’. It’s been gratifying to see reviewers agreeing with me that it’s Ultan’s finest record thus far!

MW : Tell me about your role in Law & Order...

BQ : Well, I had four Law & Order roles, actually. Two are on Law & Order: SVU and two are on the mothership Law & Order.

My first big role on SVU was of a victim, Jean Weston, on the season finale of their 2nd season, many moons ago. This character was a mother and wife from Oregon whose husband and son got stabbed to death by a serial killer – played by Richard Thompson.

I’ll never forget this role for many reasons but primarily it was a job where I discovered I could cry on cue. The director and producers decided they wanted to end the episode with a huge close up of my character, breaking down in the gallery in the courtroom. One of the producers shouted out, “Bernadette…can you cry on cue!?” I meekly replied, “Sure.” Next thing I hear was…”rolling….” and “ACTION”… I looked up, terrified I wouldn’t be able to summon up tears but imagined the hell my character went through and looked deeply into Chris Meloni’s eyes and …phew!...started to cry!

The Law & Order franchise has been a godsend for many actors. Not just financially, which it has and still is but for me, the experience I gained working on those shows led to a lot more television and film work over the years, so I’m forever grateful to creator/producer, Dick Wolf.

MW : What are your own views on law & order? Anything you’d like to see relaxed or tightened up on?

BQ : Feels very naïve and idealistic to say this, but I’d love to see major, police reform. Police brutality is despicable and out of control, especially in Black communities.

I believe we’re beginning to see the power of the Black Lives Matter movement resulting in some of these police officers losing their jobs and sometimes being arrested themselves for their unspeakable acts of violence, but I imagine we, as a nation, need to keep the pressure on. The police brutality simply has to stop. There has to be more consequences for those senseless deaths. There has to be better training, etc...

I’d also love to see major gun control in this country. I would love to see guns banned. Period. But that’s highly unrealistic as this country tragically has a major addiction to their gun culture. Perhaps someday we’ll have some common-sense gun control again such as background checks, and high-capacity magazine and semi-automatic assault weapon bans.

MW : What was it like working with Kenneth Branagh?

BQ : I suggested Kenneth’s play “Public Enemy” to the Irish Arts Center’s Artistic Director at the time, Nye Heron, and was emailing and talking with Kenneth’s assistant quite a lot before setting up a meeting with Kenneth and Nye.

I was flying high that I helped to secure the rights to his play. Kenneth then came to our first read-through, and he came back to see a preview or two. He was an absolute prince, kind, intelligent, caring, witty.

However, this success was so bittersweet because my dad died right before we opened the play, a performance I had dedicated to him before he died (because my dad loved Jimmy Cagney, and the main character of the play was obsessed with Cagney). The play got great reviews and we ran for five months. It was so difficult for me to fully appreciate the success of this show as I was mourning the most devastating loss of my life.

MW : Which "shelved" film appearance of yours should have seen the light of day?

BQ : There’s a provocative film I am in about a racial experiment that is under the radar called, “The Suspect” (2014), which stars Mekhi Phifer, Sterling K. Brown and William Sadler.

By the way, I am currently in three indie films that I’m psyched for the world to see: I play a lead role in “Darcy” which is available (worldwide) to stream on Herflix.com; “The Garden Left Behind” has just landed international distribution, so stay tuned for the release date! And finally, I have an interesting supporting role in a film called “Tahara” which had its world premiere at Slamdance in January and is slated for more film festivals.

MW : What makes a good film/TV critic? Can you name any?

BQ : One that doesn’t give the plot, or too much dialogue away. I often don’t read reviews of films, or television shows, I want to watch because I love going in – not being influenced by another’s opinion. But sometimes, I’ll read reviews afterwards to learn more about the evolution of a film or TV show. I often find myself agreeing with A.O.Scott’s (NY Times) film reviews.

MW : How do you usually prepare for an acting role, and has a character ever taken you over?

BQ : The first thing I do is read the script several times and see what the words are telling me about the character, and how other characters view that person. If it’s a period piece, I research the era or history surrounding the event in the play, or screenplay. Eventually, I forget my research, learn my words and hopefully let the character inhabit me emotionally, physically and psychologically, spiritually etc…and try my best to be fully present with the other actors I’m working with moment-to-moment. Every project is different.

Yes, there were times, I found it difficult to shut off the pain of a character after some performances. Two that come to mind are two intensely emotional theatre roles I performed at the Repertory of St. Louis, Elizabeth Proctor in “The Crucible”, and Agnes in “Bug”.

MW : Is performing on film different to TV as an acting discipline?

BQ : I think it all depends on the style of the film, or television show. With a TV show like Law & Order, it’s formulaic and heightened realism (acting style) and so one makes sure one knows every single word, and hits one’s marks, and if it calls for emoting then one must emote! Some films I’ve done are grittier-kitchen-sink realism. A very minimalistic style of acting.

MW : Has your song-writer husband ever penned a song for you?

BQ : Yes, many….Don (Rosler) primarily writes for and with other artists – on the John Margolis: Christine’s Refrigerator CD, there’s many tunes that speak to many moments within the course of our lives: the title track (altho’ the name was changed), “Scrap of Hope” (a pep talk to me when I was stuck at a temp job I hated), “Here’s Something You Don’t See Every Day” (a wedding reverie that literally started in Don’s mind when I fell asleep on his shoulder), and he wrote an exquisite lyric for Bobby McFerrin’s Grammy-nominated record VOCAbuLarieS, a song called “Brief Eternity”… where his words infuse my love for gardening: “Working in the garden has you... ...Breathing in the bloom and then you View the sunset view to move you Close to truly understanding Life and death but nothing ending Voices living on”…..

MW : Tell me about some of your favourite music...

BQ : My music tastes are pretty eclectic – besides all the indie artists I’ve done publicity for, I love so many styles of music from classical to folk to country but here’s some of my fave artists: Tom Waits, Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder, Pink, Beyonce, Billie Holiday, Ani DiFranco, Ibeyi, Sinead O’Connor, Prince, Bjork, Leonard Cohen, Kacey Musgraves, K.D. Lang, Laura Mvula, Frank Sinatra, Ray Charles, Billy Bragg, and Randy Newman, among many others.

MW : ...and your favourite films....

BQ : Ohhhhh-so-many faves but a few, in no particular order :

Portrait Of A Lady On Fire (2019)

Parasite (2019)

Secrets & Lies (1996)

Vera Drake (2004)

Pain And Glory (2019)

Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind (2004)

BlacKkKlansman (2018)

A Fantastic Woman (2017)

Babette’s Feast (1987)

Coco (2017)

To Kill A Mockingbird (1962)

Nights of Cabiria (1957)

The 400 Blows (1959)

12 Years A Slave (2013)

Jean de Florette (1986)

Trees Lounge (1996)

My Left Foot (1989)

In America (2002) (I know I’m biased but still…such a beautiful film)!

Annie Hall (1977)

My Beautiful Laundrette (1985)

My Brilliant Career (1979)

And I also love documentaries and a ton of old movies from the 1930’s and 1940’s, such as The Lady Eve (1941).

MW : ...plus your favourite books....

BQ : I’m currently reading this years New York Times Bestseller American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins (it’s excellent!).

Some of my all-time faves are :

Of Human Bondage ~ W. Somerset Maugham (1915)

A Confederacy Of Dunces ~ John Kennedy Toole (1980)

Angela’s Ashes ~ Frank McCourt (1996)

The Grapes Of Wrath ~ John Steinbeck (1939)

Lady Chatterley's Lover ~ D.H Lawrence (1960)

Olive Kitteridge ~ Elizabeth Strout (2008)

Americanah ~ Chimanda Ngozi Adichie (2013)

The Feast of Love ~ Charles Baxter (2000)

Everything Here Is Beautiful ~ Mira T. Lee (2008)

An American Tragedy ~ Theodore Dreiser (1925)

Sister Carrie ~ Theodore Dreiser (1900)

Act One ~ Moss Hart (1959)

Born A Crime ~ Trevor Noah (2016)

Wild : From Lost To Found On The Pacific Crest Trail ~ Cheryl Strayed (2012)

MW : You enjoy gardening. How is yours designed and tended to?

BQ : I don’t have my very own garden. I live in NYC and dream of having a country house with a garden of my own one day!

This is the reason I started a side business of urban gardening. My dad was an extraordinary gardener and after he died, I started tending to my mother’s flower gardens. Then I found myself volunteering at a neighborhood garden and that led to me working in other people’s gardens. Primarily small back gardens and some rooftop or balcony gardens.

I specialize in flowers, shrubs and trees and love planting lots of perennials (flowers and plants) with annuals so there’s lots of varying blossoms of different heights and textures, throughout spring, summer and fall.

When possible, if space allows, I also love incorporating foot paths, rock walls, or other elements in gardens – art/birdbaths/benches/statues that might be a sweet focal point but primarily I love the combinations of plants, trees, shrubs and flowers to be the focal points.

MW : Recommend five flowers...that every good garden should have!

BQ : Daffodils - one of the first signs of spring! Muscari (aka grape hyacinths) – the color (blue) is gorgeous, as is the scent. Climbing roses – the beauty and romantic history of roses. Anemone Robustissima (late blooming perennial flower). Lady Ferns (okay not a flower, but I’m a fern freak and I love ferns of all kinds!, but Lady ferns in particular are stunning when they sit beside most flowers or surround trees).

MW : How opinionated are you on current events? Would you like to be more, or less opinionated?

BQ : I’m extremely opinionated on current events but find it difficult to find ways to communicate my thoughts without screaming angrily from the rooftops and then of course not being heard. There are those that say we have an obligation to try to talk sense into people whose viewpoints are much more extreme than one’s own (either extreme conservative or extreme liberal).

I’m very liberal but am more pragmatic when it comes to progress, not perfection, so I’m very happy to enthusiastically vote for someone like Joe Biden or in 2016, Hillary Clinton, but I honestly don’t know how to reach people whose minds are already made up – people who either continue to justify their support for the current racist/narcissist/sexist/pathological liar-in-chief, or that justify their “protest” vote by falsely equivocating both candidates as “the same” or “the lesser of two evils”.

So yeah, I offend people at times because yes, I’m judgmental when it comes to politics and I most definitely believe in the power of protests, but believe just as strongly in the collective power of one’s vote and it drives me insane when others don’t show up and vote for local elections, and national ones.

I find I do hold back on Facebook, not because I’m afraid to voice my opinions but because it becomes too much of a time suck for me.

MW : What character traits frustrate you?

BQ : Impatience (in myself). Aggression (in myself and others).

MW : What’s the kindest thing another person has done for you?

BQ : I find this question so complex to answer. There are so many inexplicable moments in my life, where I’ve been blown away by many seemingly small gestures or kind words from strangers. And professionally, I’ve been truly blessed to work with some top-notch directors that gave me the gift of encouraging me to fully trust my artistic instincts.

When I was a child, my parents were not the type of people who conveyed their love in typically demonstrative ways, in ways that I honestly craved, so on the rare occasions when either one of them did utter something like “We’re proud of you”, or “I love you”, I was very moved by them going past their own comfort zones to express that kind of sentiment!

I’ve had many personal and professional challenges in my life and many of my siblings have been there for me over the years in ways I can’t really articulate without choking up. I also think having the courage to face one’s disagreements and past hurt, which comes with the territory of most friendships and relationships, is an act of kindness that I most value. Those I feel closest to have stuck it through with me by navigating through some painful, complex and messy misunderstandings. I’ll never forget those acts of kindness and generosity.

MW : What have you lost, growing older... and gained?

BQ : My mom died in January, and as I mentioned, my dad died many years ago. Sometimes I feel the depths of that loss – the fact that I don’t have my parents to share the ups and downs of the events of the rest of my life. Of course, I do have them close to my heart and their spirits live on….but damn I miss them! I’ve definitely gained a profound appreciation for them and their influence on me in countless ways.

On a professional level, as an older actress, unfortunately it’s easy to become invisible but I’m not ready to disappear and am joining the fight against ageism! I’m drawn to stories and filmmakers that include women and men of all ages, genders and ethnicities.

Perhaps if enough roles are not forthcoming in the next number of years, I’ll venture into writing and directing at some point.

MW : Where can we find out more / keep in touch?

BQ : Thanks so much, here’s a few links…!

https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0703489/

https://twitter.com/quigdette

https://www.instagram.com/quigdette/

https://www.facebook.com/bernadette.quigley.3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernadette_Quigley

https://bernadettequigleymedia.wordpress.com/

https://bernadettetheconstantgardener.wordpress.com/bio/

© Mark Watkins / July 2020

0 notes

Text

Give Some, Take Some: How the Community Fridge Fights Food Insecurity

A Free Fridge for the community at 1144 Bergen Street in Crown Heights

At these community-run sites, anyone is welcome to take or leave food

One afternoon in May, artist and community gardener Sade Boyewa was scrolling through her Instagram feed when she caught a photo of a commercial fridge sitting outside a brownstone in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was stocked full with squash, canned chickpeas, carrots, and bread, and above it, there was a sign painted in bright letters that read “FREE FOOD.” “I remember thinking, this is what we need in Harlem,” she told me. “The line to the food pantry snakes around two blocks. Not everyone is fit to go and stand on line for several hours.”

Like millions of other Americans, Boyewa had been laid off from her day job in March. As she worked to put together other paid projects from home, she used any leftover time she had to coordinate a free fridge of the same kind at 352 W. 116th Street in Harlem, across the street from where she’s lived for 25 years. Through Instagram, she got in touch with A New World In Our Hearts, the anarchist community organizers behind the Bed-Stuy fridge, and after a week they were able to find and deliver a donated fridge to her doorstep. After she plugged it into an outlet at her local bodega (with the enthusiastic permission of her deli guys), and stocked the stainless steel home fridge with yogurt, plantains, apples, and lettuce, some donated and some purchased, Boyewa joined the ranks of volunteer citizens running free community fridges all over the country right now. The sign on the door read, “Take what you need. Leave what you don’t,” and in Spanish, “Comidas gratis.” “People couldn’t believe it,” Boyewa said. “‘Is this for real? Is this free?’”

The fallout from the coronavirus touching down in the U.S. earlier this year has been devastating, especially for New York City. When restaurants, bars, and nonessential businesses closed as a mandate of the state-imposed shutdown on April 29, millions of people found themselves out of jobs, unable to pay rent, and lacking the food they needed to survive. An estimated 1 million New Yorkers consistently went without food before the global pandemic began, and in only three months, that number had more than doubled. By mid-May the city pledged to deliver 1.5 million meals a day to the 1 in 4 New Yorkers who were now food insecure, but the $170 million plan was stretched thin and flawed. In a CBS New York report, some New Yorkers said they found the city’s food deliveries to be lacking in nutrition, or worse, spoiled. These solutions started to look like Band-Aids over a growing wound.

While the city’s coordinated food service worked to correct its failings, New Yorkers were busy taking matters into their own hands. In seven locations in under four months, conventional and commercial fridges, plastered with signs of free food, were plugged into extension cords tethered to apartment buildings, corner bodegas, and businesses in three out of the five boroughs: the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Thadeaus Umpster, a member of A New World In Our Hearts, said the organization will soon set up fridges in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, D.C., and several more locations in New York. Many of the fridges, like one that was set up outside Playground Coffee Shop in Bed-Stuy, have social media accounts that provide updates on their daily stocks — today, blueberries and radishes; tomorrow, it could be anything.

In Brownsville, a predominantly black neighborhood in East New York, a free fridge was set up in early June by folks running Universe City, an urban aquaponic farm and workspace. The space and the fridge at 234 Glenmore Avenue have become hubs for organizers in the Black Lives Matter movement since the protests began at the end of May, and protesters who have taken to the streets to demand justice have inherited boxes of donated fresh produce to sustain their energy in the fight. “We’re incubating the political and social education of people in our community,” Alexis Mena, the co-founder of Universe City and one of the free fridge’s organizers, said, “so they can better understand how to take power back from the institutions who have taken it from them.”

Using food as a form of protest has long and storied roots in black communities, and urban farming and the Brownsville free fridge are acts of resistance to the food apartheid that leaves many BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of color) neighborhoods without access to fresh, healthy food. Black people have experienced vastly disproportionate COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths to white people, so the Brownsville free fridge hopes to draw attention to the racist city-planning that has affected the health of their communities as well. “It’s the quality of our air, how close we are to landfills,” Mena said, so why should they trust the government to properly feed them?

By extension of the fact that the free fridges are maintained by people in the community for people in the community, Boweya, Mena, and Pam Tietze, an artist who organized the Friendly Fridge in Bushwick, said that everyone begins to feel protective ownership over the fridges. “The deli next door has a hose and they spray down the fridge sometimes to keep it clean,” she said. “The superintendent of the building next to the fridge has become its guardian angel. He interviews people who come to the fridge; he reports to the group chat what the current stock levels are like.” On Mother’s Day, a local florist left a box of individually portioned flower bouquets with a sign: “Take a flower for mom!” Tietze set up a Venmo account to receive donations for groceries and a local artist painted a friendly face on the fridge. This was the community-centered result that Tietze had hoped for. “I wanted the fridge to self-regulate,” she said. “I’m not the fridge’s mom. I’m just the person who put it out there.” As the protests against police brutality began at the end of May, Friendly Fridge organizers set up a memorial to George Floyd with a framed photo, bouquets of flowers, and santeria candles.

On a rolling gate behind the fridge, Hugo Girl, the artist who had given the Friendly Fridge a face, painted, “NO CURFEW ON JUSTICE. LET’S EAT THE 1%.”

The community fridge system, while relatively novel in New York, is not an unfamiliar concept in other parts of the world. The movement was popularized in Berlin, when a volunteer-run organization called Foodsharing that has done peer-to-peer community food saving and sharing since 2012 began setting up community fridges (known as fair-teiler) across Germany in 2014. At one point, there were 350 fridges around Germany, with 25 in Berlin alone, all with the purpose of saving and redistributing perfectly good food that would otherwise go to waste. But in 2018, the German government’s food and safety regulators in Berlin cracked down on fair-teiler, causing a large number of them to be locked by their stewards or moved to more private spaces, instead of remaining free and open on the street for anyone to use any time of the day.

In a paper for Geoforum in 2019, Dr. Oona Morrow, a researcher at the Wageningen University in the Netherlands, found that the regulatory fears governments have around community fridges often stem from “fear of unknowable risks.” (Namely, liability around food contamination and spoilage, and lack of official labeling and processing.) “These fears are stoked by a technocratic risk regime that places trust in businesses, scientists, and markets, but not the public,” she writes. But, as she told me by phone from Holland, the research she performed while working with SHARECITY suggests that “sharing food is not how food safety crises happen.” Findings around the E. coli outbreak in romaine lettuce in 2019, for example, pointed to the proximity of cattle to produce-growing fields in Salinas, California, as the likely source of the spread. “It’s through industrial food systems that risk is amplified.”

“Community fridges are an opportunity for people to reimagine what the infrastructure of cities could be like,” Morrow said. “Fridge volunteers are prototyping a different kind of urban infrastructure that could be more caring.” Free fridges in the U.S. have some advantages over their EU counterparts, she added, because our food safety regulations are not nearly as strict as they are in countries like Germany. “With public infrastructure, there is this idea that it can’t work, people aren’t caring enough, people don’t know how to cooperate or take care of each other,” but her research has found those fears to be unfounded, she said. Plus, with the high need for food sharing and other forms of mutual aid in our current crisis, “more things are tolerated in an emergency.”

Right now, there are free community fridges on every continent except Antarctica, and any community fridge coordinator can add theirs to a growing global database on Freedge.org, a volunteer community fridge network started by Ernst Bertone Oehninger in 2014. Bertone Oehninger, a Brazilian Ph.D. candidate in ecology at UC Davis in California, set up a community fridge on his front lawn in 2014. “We didn’t ask for permission before we looked into the food laws or liability laws,” he told me. “The county impounded the fridge because they said it was illegal food distribution.” But, as Bertone Oehninger pointed out in the local news at the time, the food regulation laws Freedge was being held to weren’t written to include individual food sharing. Freedge isn’t a restaurant, he reasoned, so why was it being treated that way?

With help from city officials, Freedge was soon protected under California’s gleaner laws, meaning it could safely distribute produce but not home-cooked food. Now, whenever someone reaches out to Freedge asking how they can set up one in their town, the volunteer organization provides resources like information on liability, as well as open-source guides to solar-powering fridges and adding cameras to make sure stocks within the fridge are fresh. Their primary recommendations are to check the fridge once a day and clearly outline what foods are not allowed, as those regulations will vary state to state.

The Community Fridge Network, which began in 2017 in the U.K., takes a more centralized, regulated approach. The fridges are donated to local communities through the country by Hubbub, an environmental nonprofit. The Community Fridge Network has clear guidelines on what can and cannot be accepted — no raw cheeses and home-cooked meals, for example, to both limit liability around allergens and prevent foods in the fridge from becoming spoiled. Each fridge has at least one coordinator who checks it daily, each fridge maintains a similar aesthetic design, and the people running each unit can receive grant money from Hubbub for maintenance and support. The primary challenge that CFN faces is that the fridges can run out of food too quickly after the stores are replenished. Clare Davies, the coordinator of a community fridge in Dorking, England, said that is only a reflection of the high need of the communities that the fridges serve. “That’s not a problem that is caused by the community fridge, that’s a problem that’s existed before the community fridge was even there.”

Food pantries and government food assistance programs should in theory help to solve the problem of food insecurity, but these systems come with their own set of problems. Mel Paola Murillo, an immigrant from Honduras who is currently seeking asylum in the U.S., has found that the major advantage of the free fridge she uses in New York is that she can get food from the fridge without judgment or questions about her documentation, identity, or needs. “To find free resources is a very important part of my surviving experience in New York,” she told me. The fridge also provides a wider range of culturally relevant foods, as the donations typically come from within her neighborhood. “I like to cook food from my country, and [in the fridge] I’ve found cilantro, plantains, and nopales.” There are also pervasive stigmas around visiting food pantries to get something to eat, as one neighborhood woman told organizers of the Free Fridge. “I feel embarrassed accepting handouts,” she said, but at the Friendly Fridge, “Nobody pays any mind. It’s a big deal that I’ve had breakfast every day this week and I’ve had dinner. It’s changed everything.”

The throughline between all free fridges — whether part of a centralized network or not, in a major city or not — is that they attempt to do the work that more bureaucratic and structural systems like the government won’t and formal food pantries can’t do. “The city, state, and federal government have failed on multiple levels in regards to this crisis,” Umpster, of A New World In Our Hearts, told me. The free fridge model is one way that communities can work together to support each other, while also mitigating the omnipresent excess of food waste in America. “[Unlike food pantries], we don’t coordinate or cooperate with the government. We’re not asking people to give us personal information. We’re not asking people to pray with us, we’re not a charitable organization. We’re a mutual aid group.” That distinction is important — the stigmas that come with having to ask for help are all but eradicated when anyone, anywhere, no matter their situation, can both give to and take from the fridge.

While no city officials have yet to interfere or raise questions about any of the community fridges that have shown up around New York’s boroughs, Umpster said that he doesn’t anticipate strong pushback, as the “response has been universally positive.” Fridges in other cities haven’t always been so lucky — one community fridge owner in Washington state has become the center of a legal battle after authorities shut her fridge down twice. This kind of response isn’t uncommon, Bertone Oehninger explained, because “if you present the idea where the idea doesn’t exist yet, ‘no’ is very easy to say.”

New York’s fridge organizers remain undeterred. “This is a people’s movement,” Boyewa told me. “And right now, people are hurting.” While Boyewa and Tietze welcome outside support and outreach from more formal systems, Mena is less optimistic that something like that could, or even should, actually happen. “No one is going to save us. They’ve proven that they don’t care,” Mena said, adding that racism has pushed his community to take matters of food distribution into their own hands. “Black, indigenous, and people of color have been set up to fail,” he added, “so the people have to come together to take the power back.”

Dayna Evans is a freelance writer. Clay Williams is a Brooklyn-based photographer.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3hEUvng

https://ift.tt/37CEpGk

A Free Fridge for the community at 1144 Bergen Street in Crown Heights

At these community-run sites, anyone is welcome to take or leave food

One afternoon in May, artist and community gardener Sade Boyewa was scrolling through her Instagram feed when she caught a photo of a commercial fridge sitting outside a brownstone in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was stocked full with squash, canned chickpeas, carrots, and bread, and above it, there was a sign painted in bright letters that read “FREE FOOD.” “I remember thinking, this is what we need in Harlem,” she told me. “The line to the food pantry snakes around two blocks. Not everyone is fit to go and stand on line for several hours.”

Like millions of other Americans, Boyewa had been laid off from her day job in March. As she worked to put together other paid projects from home, she used any leftover time she had to coordinate a free fridge of the same kind at 352 W. 116th Street in Harlem, across the street from where she’s lived for 25 years. Through Instagram, she got in touch with A New World In Our Hearts, the anarchist community organizers behind the Bed-Stuy fridge, and after a week they were able to find and deliver a donated fridge to her doorstep. After she plugged it into an outlet at her local bodega (with the enthusiastic permission of her deli guys), and stocked the stainless steel home fridge with yogurt, plantains, apples, and lettuce, some donated and some purchased, Boyewa joined the ranks of volunteer citizens running free community fridges all over the country right now. The sign on the door read, “Take what you need. Leave what you don’t,” and in Spanish, “Comidas gratis.” “People couldn’t believe it,” Boyewa said. “‘Is this for real? Is this free?’”

The fallout from the coronavirus touching down in the U.S. earlier this year has been devastating, especially for New York City. When restaurants, bars, and nonessential businesses closed as a mandate of the state-imposed shutdown on April 29, millions of people found themselves out of jobs, unable to pay rent, and lacking the food they needed to survive. An estimated 1 million New Yorkers consistently went without food before the global pandemic began, and in only three months, that number had more than doubled. By mid-May the city pledged to deliver 1.5 million meals a day to the 1 in 4 New Yorkers who were now food insecure, but the $170 million plan was stretched thin and flawed. In a CBS New York report, some New Yorkers said they found the city’s food deliveries to be lacking in nutrition, or worse, spoiled. These solutions started to look like Band-Aids over a growing wound.

While the city’s coordinated food service worked to correct its failings, New Yorkers were busy taking matters into their own hands. In seven locations in under four months, conventional and commercial fridges, plastered with signs of free food, were plugged into extension cords tethered to apartment buildings, corner bodegas, and businesses in three out of the five boroughs: the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Thadeaus Umpster, a member of A New World In Our Hearts, said the organization will soon set up fridges in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, D.C., and several more locations in New York. Many of the fridges, like one that was set up outside Playground Coffee Shop in Bed-Stuy, have social media accounts that provide updates on their daily stocks — today, blueberries and radishes; tomorrow, it could be anything.

In Brownsville, a predominantly black neighborhood in East New York, a free fridge was set up in early June by folks running Universe City, an urban aquaponic farm and workspace. The space and the fridge at 234 Glenmore Avenue have become hubs for organizers in the Black Lives Matter movement since the protests began at the end of May, and protesters who have taken to the streets to demand justice have inherited boxes of donated fresh produce to sustain their energy in the fight. “We’re incubating the political and social education of people in our community,” Alexis Mena, the co-founder of Universe City and one of the free fridge’s organizers, said, “so they can better understand how to take power back from the institutions who have taken it from them.”

Using food as a form of protest has long and storied roots in black communities, and urban farming and the Brownsville free fridge are acts of resistance to the food apartheid that leaves many BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of color) neighborhoods without access to fresh, healthy food. Black people have experienced vastly disproportionate COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths to white people, so the Brownsville free fridge hopes to draw attention to the racist city-planning that has affected the health of their communities as well. “It’s the quality of our air, how close we are to landfills,” Mena said, so why should they trust the government to properly feed them?

By extension of the fact that the free fridges are maintained by people in the community for people in the community, Boweya, Mena, and Pam Tietze, an artist who organized the Friendly Fridge in Bushwick, said that everyone begins to feel protective ownership over the fridges. “The deli next door has a hose and they spray down the fridge sometimes to keep it clean,” she said. “The superintendent of the building next to the fridge has become its guardian angel. He interviews people who come to the fridge; he reports to the group chat what the current stock levels are like.” On Mother’s Day, a local florist left a box of individually portioned flower bouquets with a sign: “Take a flower for mom!” Tietze set up a Venmo account to receive donations for groceries and a local artist painted a friendly face on the fridge. This was the community-centered result that Tietze had hoped for. “I wanted the fridge to self-regulate,” she said. “I’m not the fridge’s mom. I’m just the person who put it out there.” As the protests against police brutality began at the end of May, Friendly Fridge organizers set up a memorial to George Floyd with a framed photo, bouquets of flowers, and santeria candles.

On a rolling gate behind the fridge, Hugo Girl, the artist who had given the Friendly Fridge a face, painted, “NO CURFEW ON JUSTICE. LET’S EAT THE 1%.”

The community fridge system, while relatively novel in New York, is not an unfamiliar concept in other parts of the world. The movement was popularized in Berlin, when a volunteer-run organization called Foodsharing that has done peer-to-peer community food saving and sharing since 2012 began setting up community fridges (known as fair-teiler) across Germany in 2014. At one point, there were 350 fridges around Germany, with 25 in Berlin alone, all with the purpose of saving and redistributing perfectly good food that would otherwise go to waste. But in 2018, the German government’s food and safety regulators in Berlin cracked down on fair-teiler, causing a large number of them to be locked by their stewards or moved to more private spaces, instead of remaining free and open on the street for anyone to use any time of the day.

In a paper for Geoforum in 2019, Dr. Oona Morrow, a researcher at the Wageningen University in the Netherlands, found that the regulatory fears governments have around community fridges often stem from “fear of unknowable risks.” (Namely, liability around food contamination and spoilage, and lack of official labeling and processing.) “These fears are stoked by a technocratic risk regime that places trust in businesses, scientists, and markets, but not the public,” she writes. But, as she told me by phone from Holland, the research she performed while working with SHARECITY suggests that “sharing food is not how food safety crises happen.” Findings around the E. coli outbreak in romaine lettuce in 2019, for example, pointed to the proximity of cattle to produce-growing fields in Salinas, California, as the likely source of the spread. “It’s through industrial food systems that risk is amplified.”

“Community fridges are an opportunity for people to reimagine what the infrastructure of cities could be like,” Morrow said. “Fridge volunteers are prototyping a different kind of urban infrastructure that could be more caring.” Free fridges in the U.S. have some advantages over their EU counterparts, she added, because our food safety regulations are not nearly as strict as they are in countries like Germany. “With public infrastructure, there is this idea that it can’t work, people aren’t caring enough, people don’t know how to cooperate or take care of each other,” but her research has found those fears to be unfounded, she said. Plus, with the high need for food sharing and other forms of mutual aid in our current crisis, “more things are tolerated in an emergency.”

Right now, there are free community fridges on every continent except Antarctica, and any community fridge coordinator can add theirs to a growing global database on Freedge.org, a volunteer community fridge network started by Ernst Bertone Oehninger in 2014. Bertone Oehninger, a Brazilian Ph.D. candidate in ecology at UC Davis in California, set up a community fridge on his front lawn in 2014. “We didn’t ask for permission before we looked into the food laws or liability laws,” he told me. “The county impounded the fridge because they said it was illegal food distribution.” But, as Bertone Oehninger pointed out in the local news at the time, the food regulation laws Freedge was being held to weren’t written to include individual food sharing. Freedge isn’t a restaurant, he reasoned, so why was it being treated that way?

With help from city officials, Freedge was soon protected under California’s gleaner laws, meaning it could safely distribute produce but not home-cooked food. Now, whenever someone reaches out to Freedge asking how they can set up one in their town, the volunteer organization provides resources like information on liability, as well as open-source guides to solar-powering fridges and adding cameras to make sure stocks within the fridge are fresh. Their primary recommendations are to check the fridge once a day and clearly outline what foods are not allowed, as those regulations will vary state to state.

The Community Fridge Network, which began in 2017 in the U.K., takes a more centralized, regulated approach. The fridges are donated to local communities through the country by Hubbub, an environmental nonprofit. The Community Fridge Network has clear guidelines on what can and cannot be accepted — no raw cheeses and home-cooked meals, for example, to both limit liability around allergens and prevent foods in the fridge from becoming spoiled. Each fridge has at least one coordinator who checks it daily, each fridge maintains a similar aesthetic design, and the people running each unit can receive grant money from Hubbub for maintenance and support. The primary challenge that CFN faces is that the fridges can run out of food too quickly after the stores are replenished. Clare Davies, the coordinator of a community fridge in Dorking, England, said that is only a reflection of the high need of the communities that the fridges serve. “That’s not a problem that is caused by the community fridge, that’s a problem that’s existed before the community fridge was even there.”

Food pantries and government food assistance programs should in theory help to solve the problem of food insecurity, but these systems come with their own set of problems. Mel Paola Murillo, an immigrant from Honduras who is currently seeking asylum in the U.S., has found that the major advantage of the free fridge she uses in New York is that she can get food from the fridge without judgment or questions about her documentation, identity, or needs. “To find free resources is a very important part of my surviving experience in New York,” she told me. The fridge also provides a wider range of culturally relevant foods, as the donations typically come from within her neighborhood. “I like to cook food from my country, and [in the fridge] I’ve found cilantro, plantains, and nopales.” There are also pervasive stigmas around visiting food pantries to get something to eat, as one neighborhood woman told organizers of the Free Fridge. “I feel embarrassed accepting handouts,” she said, but at the Friendly Fridge, “Nobody pays any mind. It’s a big deal that I’ve had breakfast every day this week and I’ve had dinner. It’s changed everything.”

The throughline between all free fridges — whether part of a centralized network or not, in a major city or not — is that they attempt to do the work that more bureaucratic and structural systems like the government won’t and formal food pantries can’t do. “The city, state, and federal government have failed on multiple levels in regards to this crisis,” Umpster, of A New World In Our Hearts, told me. The free fridge model is one way that communities can work together to support each other, while also mitigating the omnipresent excess of food waste in America. “[Unlike food pantries], we don’t coordinate or cooperate with the government. We’re not asking people to give us personal information. We’re not asking people to pray with us, we’re not a charitable organization. We’re a mutual aid group.” That distinction is important — the stigmas that come with having to ask for help are all but eradicated when anyone, anywhere, no matter their situation, can both give to and take from the fridge.

While no city officials have yet to interfere or raise questions about any of the community fridges that have shown up around New York’s boroughs, Umpster said that he doesn’t anticipate strong pushback, as the “response has been universally positive.” Fridges in other cities haven’t always been so lucky — one community fridge owner in Washington state has become the center of a legal battle after authorities shut her fridge down twice. This kind of response isn’t uncommon, Bertone Oehninger explained, because “if you present the idea where the idea doesn’t exist yet, ‘no’ is very easy to say.”

New York’s fridge organizers remain undeterred. “This is a people’s movement,” Boyewa told me. “And right now, people are hurting.” While Boyewa and Tietze welcome outside support and outreach from more formal systems, Mena is less optimistic that something like that could, or even should, actually happen. “No one is going to save us. They’ve proven that they don’t care,” Mena said, adding that racism has pushed his community to take matters of food distribution into their own hands. “Black, indigenous, and people of color have been set up to fail,” he added, “so the people have to come together to take the power back.”

Dayna Evans is a freelance writer. Clay Williams is a Brooklyn-based photographer.

from Eater - All https://ift.tt/3hEUvng

via Blogger https://ift.tt/3fxd8aV

0 notes

Text

Give Some, Take Some How the Community Fridge Fights Food Insecurity added to Google Docs

Give Some, Take Some How the Community Fridge Fights Food Insecurity

A Free Fridge for the community at 1144 Bergen Street in Crown Heights

At these community-run sites, anyone is welcome to take or leave food

One afternoon in May, artist and community gardener Sade Boyewa was scrolling through her Instagram feed when she caught a photo of a commercial fridge sitting outside a brownstone in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. It was stocked full with squash, canned chickpeas, carrots, and bread, and above it, there was a sign painted in bright letters that read “FREE FOOD.” “I remember thinking, this is what we need in Harlem,” she told me. “The line to the food pantry snakes around two blocks. Not everyone is fit to go and stand on line for several hours.”

Like millions of other Americans, Boyewa had been laid off from her day job in March. As she worked to put together other paid projects from home, she used any leftover time she had to coordinate a free fridge of the same kind at 352 W. 116th Street in Harlem, across the street from where she’s lived for 25 years. Through Instagram, she got in touch with A New World In Our Hearts, the anarchist community organizers behind the Bed-Stuy fridge, and after a week they were able to find and deliver a donated fridge to her doorstep. After she plugged it into an outlet at her local bodega (with the enthusiastic permission of her deli guys), and stocked the stainless steel home fridge with yogurt, plantains, apples, and lettuce, some donated and some purchased, Boyewa joined the ranks of volunteer citizens running free community fridges all over the country right now. The sign on the door read, “Take what you need. Leave what you don’t,” and in Spanish, “Comidas gratis.” “People couldn’t believe it,” Boyewa said. “‘Is this for real? Is this free?’”

The fallout from the coronavirus touching down in the U.S. earlier this year has been devastating, especially for New York City. When restaurants, bars, and nonessential businesses closed as a mandate of the state-imposed shutdown on April 29, millions of people found themselves out of jobs, unable to pay rent, and lacking the food they needed to survive. An estimated 1 million New Yorkers consistently went without food before the global pandemic began, and in only three months, that number had more than doubled. By mid-May the city pledged to deliver 1.5 million meals a day to the 1 in 4 New Yorkers who were now food insecure, but the $170 million plan was stretched thin and flawed. In a CBS New York report, some New Yorkers said they found the city’s food deliveries to be lacking in nutrition, or worse, spoiled. These solutions started to look like Band-Aids over a growing wound.

While the city’s coordinated food service worked to correct its failings, New Yorkers were busy taking matters into their own hands. In seven locations in under four months, conventional and commercial fridges, plastered with signs of free food, were plugged into extension cords tethered to apartment buildings, corner bodegas, and businesses in three out of the five boroughs: the Bronx, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Thadeaus Umpster, a member of A New World In Our Hearts, said the organization will soon set up fridges in Los Angeles, Minneapolis, D.C., and several more locations in New York. Many of the fridges, like one that was set up outside Playground Coffee Shop in Bed-Stuy, have social media accounts that provide updates on their daily stocks — today, blueberries and radishes; tomorrow, it could be anything.

In Brownsville, a predominantly black neighborhood in East New York, a free fridge was set up in early June by folks running Universe City, an urban aquaponic farm and workspace. The space and the fridge at 234 Glenmore Avenue have become hubs for organizers in the Black Lives Matter movement since the protests began at the end of May, and protesters who have taken to the streets to demand justice have inherited boxes of donated fresh produce to sustain their energy in the fight. “We’re incubating the political and social education of people in our community,” Alexis Mena, the co-founder of Universe City and one of the free fridge’s organizers, said, “so they can better understand how to take power back from the institutions who have taken it from them.”

Using food as a form of protest has long and storied roots in black communities, and urban farming and the Brownsville free fridge are acts of resistance to the food apartheid that leaves many BIPOC (black, indigenous, and people of color) neighborhoods without access to fresh, healthy food. Black people have experienced vastly disproportionate COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths to white people, so the Brownsville free fridge hopes to draw attention to the racist city-planning that has affected the health of their communities as well. “It’s the quality of our air, how close we are to landfills,” Mena said, so why should they trust the government to properly feed them?

By extension of the fact that the free fridges are maintained by people in the community for people in the community, Boweya, Mena, and Pam Tietze, an artist who organized the Friendly Fridge in Bushwick, said that everyone begins to feel protective ownership over the fridges. “The deli next door has a hose and they spray down the fridge sometimes to keep it clean,” she said. “The superintendent of the building next to the fridge has become its guardian angel. He interviews people who come to the fridge; he reports to the group chat what the current stock levels are like.” On Mother’s Day, a local florist left a box of individually portioned flower bouquets with a sign: “Take a flower for mom!” Tietze set up a Venmo account to receive donations for groceries and a local artist painted a friendly face on the fridge. This was the community-centered result that Tietze had hoped for. “I wanted the fridge to self-regulate,” she said. “I’m not the fridge’s mom. I’m just the person who put it out there.” As the protests against police brutality began at the end of May, Friendly Fridge organizers set up a memorial to George Floyd with a framed photo, bouquets of flowers, and santeria candles.

On a rolling gate behind the fridge, Hugo Girl, the artist who had given the Friendly Fridge a face, painted, “NO CURFEW ON JUSTICE. LET’S EAT THE 1%.”

The community fridge system, while relatively novel in New York, is not an unfamiliar concept in other parts of the world. The movement was popularized in Berlin, when a volunteer-run organization called Foodsharing that has done peer-to-peer community food saving and sharing since 2012 began setting up community fridges (known as fair-teiler) across Germany in 2014. At one point, there were 350 fridges around Germany, with 25 in Berlin alone, all with the purpose of saving and redistributing perfectly good food that would otherwise go to waste. But in 2018, the German government’s food and safety regulators in Berlin cracked down on fair-teiler, causing a large number of them to be locked by their stewards or moved to more private spaces, instead of remaining free and open on the street for anyone to use any time of the day.

In a paper for Geoforum in 2019, Dr. Oona Morrow, a researcher at the Wageningen University in the Netherlands, found that the regulatory fears governments have around community fridges often stem from “fear of unknowable risks.” (Namely, liability around food contamination and spoilage, and lack of official labeling and processing.) “These fears are stoked by a technocratic risk regime that places trust in businesses, scientists, and markets, but not the public,” she writes. But, as she told me by phone from Holland, the research she performed while working with SHARECITY suggests that “sharing food is not how food safety crises happen.” Findings around the E. coli outbreak in romaine lettuce in 2019, for example, pointed to the proximity of cattle to produce-growing fields in Salinas, California, as the likely source of the spread. “It’s through industrial food systems that risk is amplified.”

“Community fridges are an opportunity for people to reimagine what the infrastructure of cities could be like,” Morrow said. “Fridge volunteers are prototyping a different kind of urban infrastructure that could be more caring.” Free fridges in the U.S. have some advantages over their EU counterparts, she added, because our food safety regulations are not nearly as strict as they are in countries like Germany. “With public infrastructure, there is this idea that it can’t work, people aren’t caring enough, people don’t know how to cooperate or take care of each other,” but her research has found those fears to be unfounded, she said. Plus, with the high need for food sharing and other forms of mutual aid in our current crisis, “more things are tolerated in an emergency.”

Right now, there are free community fridges on every continent except Antarctica, and any community fridge coordinator can add theirs to a growing global database on Freedge.org, a volunteer community fridge network started by Ernst Bertone Oehninger in 2014. Bertone Oehninger, a Brazilian Ph.D. candidate in ecology at UC Davis in California, set up a community fridge on his front lawn in 2014. “We didn’t ask for permission before we looked into the food laws or liability laws,” he told me. “The county impounded the fridge because they said it was illegal food distribution.” But, as Bertone Oehninger pointed out in the local news at the time, the food regulation laws Freedge was being held to weren’t written to include individual food sharing. Freedge isn’t a restaurant, he reasoned, so why was it being treated that way?

With help from city officials, Freedge was soon protected under California’s gleaner laws, meaning it could safely distribute produce but not home-cooked food. Now, whenever someone reaches out to Freedge asking how they can set up one in their town, the volunteer organization provides resources like information on liability, as well as open-source guides to solar-powering fridges and adding cameras to make sure stocks within the fridge are fresh. Their primary recommendations are to check the fridge once a day and clearly outline what foods are not allowed, as those regulations will vary state to state.

The Community Fridge Network, which began in 2017 in the U.K., takes a more centralized, regulated approach. The fridges are donated to local communities through the country by Hubbub, an environmental nonprofit. The Community Fridge Network has clear guidelines on what can and cannot be accepted — no raw cheeses and home-cooked meals, for example, to both limit liability around allergens and prevent foods in the fridge from becoming spoiled. Each fridge has at least one coordinator who checks it daily, each fridge maintains a similar aesthetic design, and the people running each unit can receive grant money from Hubbub for maintenance and support. The primary challenge that CFN faces is that the fridges can run out of food too quickly after the stores are replenished. Clare Davies, the coordinator of a community fridge in Dorking, England, said that is only a reflection of the high need of the communities that the fridges serve. “That’s not a problem that is caused by the community fridge, that’s a problem that’s existed before the community fridge was even there.”

Food pantries and government food assistance programs should in theory help to solve the problem of food insecurity, but these systems come with their own set of problems. Mel Paola Murillo, an immigrant from Honduras who is currently seeking asylum in the U.S., has found that the major advantage of the free fridge she uses in New York is that she can get food from the fridge without judgment or questions about her documentation, identity, or needs. “To find free resources is a very important part of my surviving experience in New York,” she told me. The fridge also provides a wider range of culturally relevant foods, as the donations typically come from within her neighborhood. “I like to cook food from my country, and [in the fridge] I’ve found cilantro, plantains, and nopales.” There are also pervasive stigmas around visiting food pantries to get something to eat, as one neighborhood woman told organizers of the Free Fridge. “I feel embarrassed accepting handouts,” she said, but at the Friendly Fridge, “Nobody pays any mind. It’s a big deal that I’ve had breakfast every day this week and I’ve had dinner. It’s changed everything.”