#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society

Photo

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, May 12, 1910 / 2022

(image: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin assembling a molecular model. Photo: © Jorge Lewinski. Somerville College, University of Oxford, Oxford)

(plus: Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1964 (pdf here))

(plus: Guy Dodson, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994, «Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society», Volume 48, The Royal Society, 2002, pp. 181-219 (pdf here))

(plus: Jenny P. Glusker, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910-1994), «Protein Science», 1994 Dec; 3(12): 2465–2469, Cambridge University Press, The Protein Society (pdf here))

#chemistry#x ray crystallography#crystallography#biology#photography#journal#dorothy crowfoot#dorothy crowfoot hodgkin#birthday anniversary#jorge lewinski#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society#protein science#the protein society

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey, question, what the fuck were I sposed to do with all these "Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society"?

Monday can deal with them, wtf

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from Memoir of AMT Written by M. H. A. Newman

(원 텍스트는 turingarchive.org 의 AMT/A36 폴더 참조. 원 출처는 Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society, Vol.I, November 1955.)

"튜링을 알았던 사람이라면 그가 대화의 화제부터 과학적 난제까지, 자신의 관심을 끈 어떤 아이디어든 신나게 열정적으로 파고들었던 모습을 가장 생생하게 기억할 것이다. 하지만 탐구의 즐거움만이 그의 동기였던 것은 아니다. 그는 작은 일이건 큰 일이건, 자신의 친구들을 돕기 위해서라면 어떤 고생이든 할 수 있는 사람이었다. 그의 관심이 완전히 그의 생화학 이론에 쏠려 있을 때에도 (맨체스터 대학교) 계산기계 연구소의 동료들은 그가 언제나 그들의 문제를 도울 준비가 되어 있는 것을 볼 수 있었다. 또 다른 예로, 크리스마스 때면 그는 언제나 친구들과 그 아이들에게 줄 선물을 고르느라 심사숙고했다." - 맥스 뉴먼

0 notes

Text

Sir Samuel Hall Chair of Chemistry - Wikipedia

The Sir Samuel Hall Chair of Chemistry is the named Chair of Chemistry in the School of Chemistry at the University of Manchester, established through an endowment of £36,000 in 1913 by the Hall family.[1] Chairs have included the following chemists:

References

^ Portrait of a University, 1851-1951: To Commemorate the Centenary of Manchester University, Henry Buckley Charlton, Manchester University Press, 1951.

^ LEIGH, Prof. David Alan. ukwhoswho.com. Who's Who. 2015 (online Oxford University Press ed.). A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc.

(subscription required)

^ Jones, J. H. (2003). "Ewart Ray Herbert Jones". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 49: 263. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2003.0015. JSTOR 3650225.

^ Robinson, R. (1947). "Arthur Lapworth. 1872-1941". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 5 (15): 554. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1947.0018.

^ Brown, D. M.; Kornberg, H. (2000). "Alexander Robertus Todd, O.M., Baron Todd of Trumpington". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 46: 515. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1999.0099.

^ Alan Cook (2004). "Heilbron, Sir Ian Morris [formerly Isidor Morris". The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33799.

^ Robinson, R. (1947). "Arthur Lapworth. 1872-1941". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 5 (15): 554. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1947.0018.

0 notes

Text

[Free eBook] A Pride of Terrys by Marguerite Steen [Vintage Theatre Arts Family Biography]

A Pride of Terrys by the late English author Marguerite Steen, a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature whose works enjoyed a period of popularity in the 1930s and 1940s, is her vintage theatre artist group biography cum partial memoir, free for a limited time courtesy of publisher Endeavour Press' The Odyssey PRess imprint.

This was originally published in 1962 by Longmans, Green & Co Ltd.

This book comprises a biographical history and character studies of various members of the prominent Terry family of British actors who became a theatrical dynasty during the late 19th century and onwards, whose members included award-winning actor and film director John Gielgud. Many of the family were personal acquaintances or professional colleagues of the author, who was for a time a member of one of their theatre companies, as well as a close friend of Dame Ellen Terry.

Offered worldwide, available at Amazon.

Free for a limited time @ Amazon (available worldwide)

Description

For more than a century the name of Terry stood for the aristocracy of the English theatre…

This great and prolific family, deriving from a Portsmouth publican, encapsulates in its ramifications the names of Craig, Hawtrey and Gielgud, which subsequently represent it in the theatre and on television and radio.

The subject of this enlightening insight into the family was first suggested by the late Dame Ellen Terry, with whom Marguerite Steen was on terms of close friendship.

As a member of the Julia Neilson-Fred Terry Company, she formed intricate ties with the family, unconsciously recording the material from which this dramatic panorama was formed.

First and Foremost, A Pride of Terrys reflects the life of a family.

It provides a series of character studies that portray the rare qualities that brought the Terrys from humble beginnings to their proud eminence in contemporary theatre and is an exhilarating and inspiring story full of hope.

#free ebook#marguerite steen#terry family#biography#theatre#memoir#ellen terry#john gielgud#the odyssey press

0 notes

Text

The Murder of Martha Reay: Victim Blaming in 18th Century England

by Lauren Gilbert

Martha Ray by Nathaniel Dance, 1777

It's a story that could be taken from 21st century news media. The evening of April 7, 1779, Miss Martha Reay left the theatre with a friend. As she started to get into her coach, James Hackman shot her in the face with a pistol, and then tried to kill himself with a second pistol. Within a year or so of her death, the victim was considered somehow at fault in her own murder, even though he did not deny killing her. This case was a sensation in the press of the day.

Who was Martha Reay? Strictly speaking, in terms of the society in which she was born, Martha Reay (or Ray, or Raye, or other variations depending on the source) was no one. She was born sometime between 1742-1746 in Elstree in Hertfordshire, the daughter of a corsetmaker and his wife(?), a servant. She was apprenticed to a milliner or dressmaker at the age of 13 or so by her father. When Martha reached the age of 16, her father allegedly took her to a procuress with a prospect of prostituting her. By all accounts, she was an attractive girl (not strictly a beauty, but fresh and pretty in appearance) with a good singing voice and a kind nature. Whether through the efforts of the procuress or by other means, Martha became the mistress of John Montagu, the 4th Earl of Sandwich, when she was somewhere between the ages of 17 and 19.

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, engraving, 1774

The Earl was a married man, aged about 44 years, and a career politician with a serious love of music. He had naval interests and was a patron of Captain John Cook, who named the Sandwich Islands for the Earl. (Contrary to the myth, the "sandwich" of bread and meat named for him was his quick meal to allow him more time at his desk, not the gaming table.) Unhappily married with only one living child (a son and heir also named John), he separated from his wife in 1755, shortly after which she was found to be insane by the Court of Chancery and was made a ward of the court. While his wife remained in permanent seclusion, he was unable to divorce and remarry.

When Lord Sandwich took Martha under his "protection", he first placed her in a little house in Covent Garden with a companion, where he provided her with music masters. Whether the sexual relationship started immediately or later, the Earl took her (and her companion) to his family home Hinchingbrooke and treated her for all intents and purposes as his wife. She served as hostess at dinners Lord Sandwich hosted at the Admiralty Club for fellow politicians, and sang in two seasons of oratorios sponsored by the Earl. Over a 10-year period, Martha bore him 5 living children (4 sons and a daughter), whom he acknowledged. Sources indicate she actually had 9 children by the Earl, but only 5 survived. All accounts indicate that they were an affectionate couple.

John Hackman, hand-coloured copper engraving, 1810

In 1774, John Hackman (a birth date of 1752 put his age at 22 at this time ) met the Earl while riding with a neighbour of the Earl's, and was invited to dinner. At this point, he met Martha. Born in Hampshire, he was a handsome young man with the rank of ensign in the 68th regiment of the foot, of a respectable lower middle class family (originally destined for a trade, he went into the military instead.) Apparently, he conceived a romantic desire to rescue Martha from the Earl's clutches. Martha was several years older than Hackman and there is no indication she had feelings for him. Being in the neighbourhood, they met multiple times. Hackman asked her to marry him and she turned him down. Accounts indicate Martha cited her loyalty to Lord Sandwich and that she had no desire to marry a military man. Shortly afterwards, Hackman was posted to Ireland. In 1776 he was promoted to lieutenant, but subsequently had resigned from the army to become a clergyman, supposedly in hope that Martha would change her mind and marry him. In February of 1779, he was ordained as a deacon, then a priest, and was assigned as rector of Wiveton in Norfolk.

Apparently, Hackman's infatuation with Martha continued, possibly even grew, throughout this separation, and career change. (There is no indication he actually served in his clerical capacity.) He went to London, and sent Martha a note asking her to meet him. Accounts indicate she refused and told him to give it up, in essence. (This response appears to be the only letter known to have been written by Martha in the case.) Accounts indicate that his acquaintances noted that he was increasingly depressed. Shortly after this, on April 7, he followed Martha to the theatre, where he saw her in company including Lord Coleraine, who he decided was her current lover. He went to get 2 pistols, waited in a nearby coffee house, then, when he saw her leaving the theatre, committed the crime.

Stunned by her murder, Lord Sandwich had Martha buried next to her mother in Elstree. (Some accounts indicate he had her name engraved on a silver plaque which was mounted on her coffin.) In the meantime, during his murder trial, John Hackman pleaded innocent, saying he had not intended to kill Martha but only himself and that shooting her was a sudden impulse or frenzy, and his attorney said that he was insane. Judge and jury did not agree, especially because he had 2 pistols with him, and found him guilty. (Several witnesses also testified, which did not help his cause.) He was hanged at Tyburn April 19, 1779. Accounts indicate he met his end with bravery, asking to be buried near Martha, which did not happen. (His body was dissected at Surgeon's Hall in London.)

The newspapers reported the case heavily, initially objectively. The supposed love triangle made it irresistible. Subsequently, Hackman's handsome appearance, his despair over his failed courtship and the death of his love resulting from his crime of passion made him a more sympathetic character. Speculation that Martha had somehow led him on then spurned him began circulating. Subsequently, a pamphlet (author anonymous) was published by G. Kearsley in Fleet Street, portraying John Hackman as good hearted yet misguided young man overwhelmed by his desire to save an undeserving woman. The romance combined with the facts that Hackman was a clergyman while Martha was a fallen woman appealed to the public's imagination.

In March of 1780, G. Kearsley brought out a book titled LOVE AND MADNESS: A STORY TOO TRUE (written by Herbert Croft but published anonymously), to be the correspondence of John Hackman and Martha Reay over several years, supporting the view of Martha as the older woman taking advantage of a naive younger man then casting him aside, leading him to desperation. The book went into 9 editions. Even though the correspondence was forged and the book considered an epistolary novel when the author's identity became known, many accepted it as factual. Public opinion leaned towards sympathy with the murderer, and a feeling that the victim had brought her death on herself.

Although Martha was known to have been concerned about financial security for herself and her children (given that the Earl was significantly older than she was and not overly wealthy), she had actually considered becoming a professional singer. There is no indication that she was ever unfaithful to the Earl or that she encouraged Hackman to believe she had feelings for him. Hackman's known letters indicated that he chose to believe that she might marry him; this belief may have had roots in his obsession with an attractive woman whom he felt needed to be rescued or, even more simply, a refusal to accept that she did not want to be with him. In my opinion, evidence does not support the theory that Martha toyed with him then cast him aside.

After Martha's death, Lord Sandwich took care of their children who continued to live with him. Although one son died, the other 3 had opportunities and their daughter married an admiral. Lord Sandwich died in April of 1792. Mary Hervey, Lady Fitzgerald, was shown as his last mistress by one source, but another referred to her as a good friend to the Earl. Most biographical references for the Earl that I found do not mention a mistress after Martha. It seems he remained faithful to Martha's memory. I found nothing to indicate that he believed that Martha enticed Hackman. Sadly, you can still find speculation that Martha led James Hackman on in accounts today.

Sources include:

CASE and MEMOIRS of Miss MARTHA REAY, to which are added, REMARKS, by Way of Refutation on The CASE and MEMOIRS of the Rev. Mr. Hackman. London: M. Folingsby and C. Fourdrinier, 1779. (ECCO Print Edition)

Stebbins, Lucy Poate. LONDON LADIES True Tales of the Eighteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1952.

EverythingExplained.com. "John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich explained" (no author or post date shown). HERE

ExecutedToday.com "1779: James Hackman, sandwich wrecker" by Headsman, posted April 19, 2015. HERE

Plagiary. "LOVE AND MADNESS: A Forgery Too True" by Ellen Levy, 2006. HERE

Pen and Pension. "The Rev. James Hackman and the Murder of Martha Reay" posted June 10, 2015 by William Savage. HERE

Royal Favourites. "English Earls' and Countesses' Lovers and Mistresses" posted by Eu Royales (no date provided). HERE

Smithsonian.com. "Fatal Triangle" by John Brewer, Smithsonian Magazine, May 2005. HERE

Watford Observer. "Martha Ray" (no author or post date shown). HERE

Illustrations:

Martha Ray: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

John Hackman: Wikimedia Commons, HERE

~~~~~~~~~~

Lauren Gilbert, author of HEYERWOOD: A Novel, holds a B.A. in English and is a long-time member of JASNA. She lives in Florida with her husband, and is working on her second book A RATIONAL ATTACHMENT. Please visit her website here for more information.

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Text

Radio Astronomy: Not Just for the Far-out Invisible Universe

In honor of the 2017 total solar eclipse over the continental United States on Monday, October 21, I've done some digging into radio astronomy's history involving the Sun. While radio astronomy is often considered "exploring the invisible universe" (to quote the NRAO) in the context of the interstellar medium (ISM) and far-away planetary systems, the field also has an intimate past with our own solar system.

The Sun has been a player in radio astronomy history since the field's earliest beginnings, first making an appearance in Karl Jansky's notebook. Karl Jansky—an American radio engineer at Bell Labs who laid the foundation for radio astronomy in the 1930s—was searching for the source of static "of unknown origin" using a large radio antenna. Jansky ruled out thunderstorms, power lines, and radio transmitters as sources of the mysterious steady hiss because of how the signal sometimes disappeared depending on the position of his antenna. Initially, the static seemed to follow the Sun, coming from the east in the morning, the south at midday, and the west in the afternoon. After about a month, however, the radio noise no longer aligned with the Sun, and six months later the source of static seemed opposite the Sun. Eventually, the radio noise was determined to be radio waves from the center of the Milky Way galaxy.

Over the next decade, there was little buzz over radio waves coming from outer space. During World War II, English physicist James Stanley Hey detected radio waves that were in fact coming from the Sun. Hey was employed by the Army Operational Research Group in 1940 to research anti-aircraft radar in an effort to combat the Germans who were jamming radio communications among the Allied Forces. In February 1942, radar stations along the south coast of England saw a significant increase in radio interference. While the interference was thought to be the result of Axis operatives on the French coast, the source could not be verified. Hey observed patterns in the interference, noting that the strongest radio interference came from the direction of the Sun. He was initially skeptical that the Sun could be jamming the Allies' communications, but after consulting with the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, he was convinced; the Sun was experiencing particularly strong sunspot activity at that time, resulting in the emission of strong solar radio emissions. After World War II, Hey continued to investigate radiation from the sun and how it correlated with solar activity.

Curious about the strength of radio emissions from the Sun, British-born Australian scientist (John) Paul Wild joined the Radiophysics Division of Australia's Council for Scientific and Industrial Research in 1947. Over the course of several decades, Wild's team built several solar radio-observatories, including a radio spectrograph that pointed at the Sun 12 hours a day from Dapto and a huge radiotelescope near Narrabri at Culgoora Observatory—a radioheliograph comprising of 96 antennas in a three-kilometer ring that gave astronomers a look at the Sun's corona.

The Australian team jump-started solar research using radio astronomy techniques, specifically to study the solar corona. Their first major discovery was reported in 1950; using the spectrograph they had discovered three types of solar burst (Type I, Type II, Type III) which is the now-accepted international standard. With the radioheliograph a decade later, they observed the mysterious solar corona—the Sun's upper atmosphere that extends millions of kilometers into space. Phenomena in the corona are invisible to optical telescopes so had not been studied by the 1960s. Keeping in mind that sunspots are regions of intense magnetic field, the team devloped the telescope such that oppositely polarized radiation (think of sunspots as opposite poles of a magnet) would be recorded separately. When the recorded data were superimposed, an image of the Sun was generated, showing unpolarized regions in white. As a result of this work in radio astronomy, the foundation for solar plasma research was set in place.

The invisible Sun has long been illuminated by the field of radio astronomy. Since the field's humble of beginnings by amateur astronomers, solar radio astronomy has grown into a science that sheds light on our closest star. A solar eclipse, during which the Moon obscures not only the Sun's visible light but also some of its radio waves, provides an excellent opportunity to study the Sun and its corona. Plenty of professional astronomers and amateurs alike will certainly have their (properly protected) eyes—and dishes!—on the sky.

References

Hewish, Antony. "James Stanley Hey, M.B.E. 3 May 1909 – 27 February 2000. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 2002, 48, 167-178

"John Paul Wild [1923-2008]." CSIROpedia

"New radio waves traced to centre of the Milky Way." The New York Times, 5 May 1993

Penley, Bill. "Dr James Stanley Hey MBE FRS." Purbeck Radar, Purbeck Radar Museum Trust. January 2011.

"Radio Astronomy — Observing Explosions on the Sun." CSIROpedia

Stokely, James. Atoms to Galaxies: An Introduction to Modern Astronomy. New York: Ronald Press, 1961, 37-39

0 notes

Link

A guide to finding obituaries can be found here.

Readers can now access all content that is over one year old. This includes memoirs of distinguished Fellows such as Albert Einstein, Dorothy Hodgkin, Sir Alan Parkes, Alan Turing, Dame Miriam Rothschild and John Bernal.

0 notes

Photo

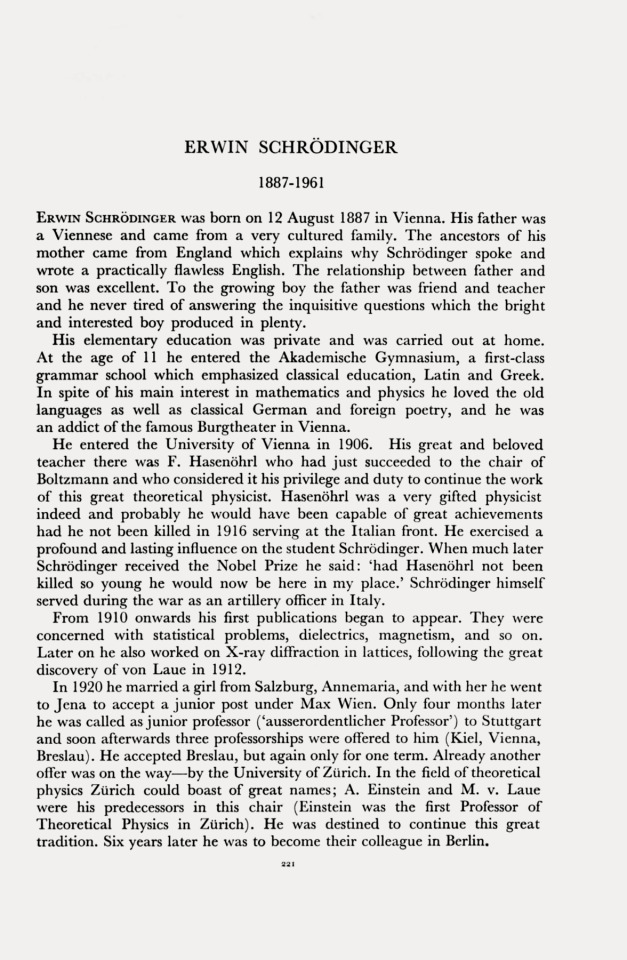

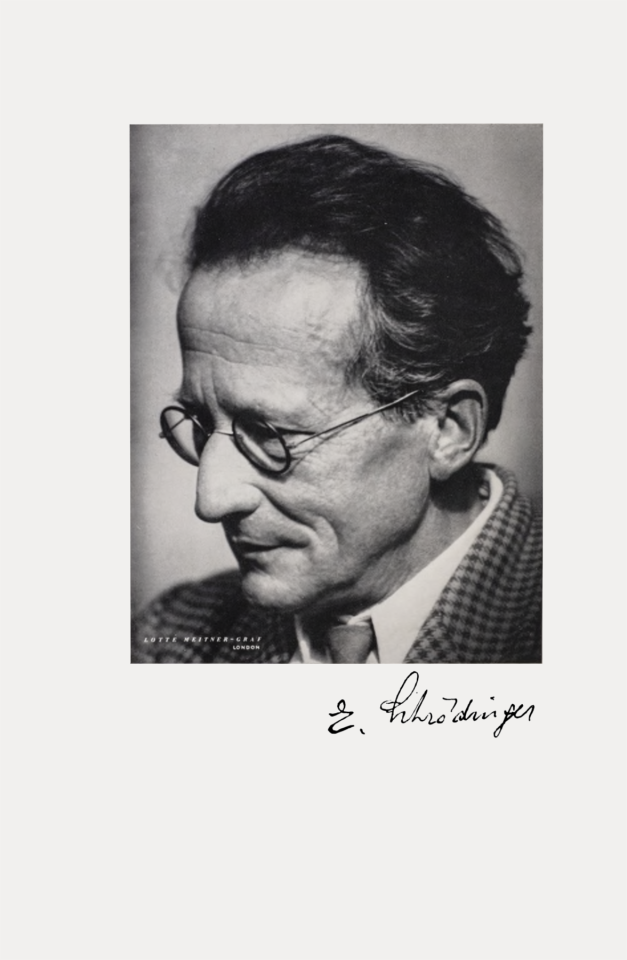

Erwin Schrödinger, August 12, 1887 / 2022

(images: Walter Heinrich Heitler, Erwin Schrödinger, 1887-1961, «Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society», Volume 7, The Royal Society, November 1961, pp. 221-228)

#graphic design#physics#journal#erwin schrödinger#birthday anniversary#walter heitler#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society#1880s#1960s#2020s

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

«First drawing of the electron density projection calculated for hexachlorobenzene.», in Dorothy M. C. Hodgkin, Kathleen Lonsdale. 28 January 1903 – 1 April 1971, «Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society», Vol. 21 (Nov., 1975), (pp. 447-484), p. 458

#physics#chemistry#crystallography#x ray crystallography#manuscript#kathleen lonsdale#dorothy m. c. hodgkin#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society#royal society#1970s

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Inge Lehmann, May 13, 1888 / 2021

(image: «The seismological discovery of the earth's inner core. From I. Lehmann, P', Bureau Central Seismologique International, Series A, Travaux Scientifiques, 14, 88, 1936»; in Bruce A. Bolt, Inge Lehmann. 13 May 1888-21 February 1993, «Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society», Vol. 43, November, 1997, (286-301), p. 294)

#graphic design#seismology#geophysics#geometry#journal#inge lehmann#publications du bureau central scientifiques#bureau central séismologique international strasbourg#bruce a. bolt#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society#1880s#1930s#1990s#2020s

164 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Henry Dalitz and Rudolf Ernst Peierls, Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac, 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984, «Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of The Royal Society», Volume 32, The Royal Society, December 1986, p. 142 (pdf here)

#graphic design#physics#history of science#history of physics#journal#p. a. m. dirac#henry dalitz#rudolf ernst peierls#biographical memoirs of fellows of the royal society#royal society#1980s

7 notes

·

View notes