#historical women are supposed to be passive agents !!

Text

so many people in the hotd/asoiaf fandom use the term 'girlboss' without a hint of irony because they can't see past their western, white views of women's rights and the status of a women in society. especially historical women - they can't see past the subjugated women archetype, passive and submissive, and to the core feminine. any woman that dare stick up for herself and her rights is immediately a girlboss because she supposedly does not follow the proper rules of society, she's not 'realistic' according to them. like i can't take the term seriously now because the white, western half of the fandom has such a rigid idea of historical women's rights and how women should react to their situations and completely ignorant of how black and women of color would and would react.

#hotd#asoiaf#house of the dragon#a song of ice and fire#anti hotd fandom#anti asoiaf fandom#historical women are supposed to be passive agents !!#x is a girlboss because she defied a man and stood up for herself#shut up !!! historical women esp women of color have been long known to be defiant and defy the roles given to them#like rhaenyra fighting for her rights is viewed negatively and a girlboss#but alicent accepting her fate and her duty while resentful is praised#both of them can be historically realistic btw and certainly not 'girlboss'#alicent hightower#rhaenyra targaryen

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

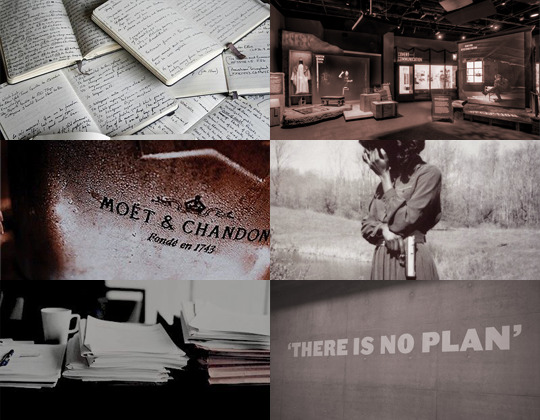

#steggyweek22 - day seven (belated) - free choice

peggy can’t say she wasn’t warned.

the official secrets act had prevented most of it thus far. but time marches on, as they say, and she’s now part of the historical record. and...there’s an exhibit. her first, a rite of passage among those like her. angie is an urban legend in her own right, and she’s tickled by the podcasts and the museum exhibits and the movies that try and fail to capture her many, many lifetimes. jarvis maintains his legendary stiff upper lip in the face of the conspiracy theories about his supposed time traveler status, while ana tries to get them in the background of as many photos as possible. peggy, as the newest of the lot, knows she should be proud of her tradecraft, since so little of her exploits have been uncovered (or linked to her, anyway), but really she’s just annoyed. the audacity of this museum and this curator to commit such lies and slander to plinth? well, she’s stayed undercover for this long for a good reason - she’s very good at what she does, and she knows how to mess with someone’s head. time to teach this steven grant rogers a thing or two.

steve will deny it under pain of death - but he’s always had a bit of a crush on agent peggy carter. he’s not the first historian to become a tad infatuated with a person they’re studying, but his level of regard (read: obsession) since doing his master’s thesis on the role of women in the post-war intelligence community is borderline concerning. which is why he was so excited to curate this exhibit on women in espionage for the international spy museum. and why he is afraid to admit...he’s pretty sure he’s being haunted. by peggy carter. or at least, someone who has her handwriting and feels very strongly about inaccuracies in his exhibit. there’s so little that’s known about her - born in hampstead in 1921, lied about her age to join the war effort, was seconded to the ssr, set up shield before going missing in action in 1951 - and steve did his best to represent her accurately in this new exhibit, but clearly someone objects to the historical record. strenuously.

through increasingly passive-aggressive sticky notes left on the museum labels, unsigned letters to the editor in the washington post, a series of anonymous twitter threads lambasting the museum, and a trove of handwritten notebooks mysteriously dropped in steve’s home mailbox, he begins to better understand who peggy carter was, and wishes more than anything that he could meet her for real. he begins to respond to the sticky notes and the twitter threads, hoping that he’ll find a relative or an old friend who can fill in the blanks that still remain.

is he in for the shock of his life...

or, a sitcom au where a (relatively) young immortal peggy carter trolls museum curator steve rogers

#steggyweek22#steggy#steggyedit#steggy au#steggyfanevents#HELLO this is so late but unfortunately it's crunch time with my dissertation#managed to finish this as a break from coding tweets for HOURS#idk this stuck in my head and I think it would be hilarious#imagine the hijinks - peggy trying to prove to Steve why XYZ minor detail is wrong#meanwhile he's convinced that he's being haunted or hallucinating the whole thing#his coworkers tease him about his ghost girlfriend#Peggy's friends laugh at her from their old immortal jadedness#etc etc

85 notes

·

View notes

Note

hiya!! i know that this is basically your whole blog jsnsjxnjd but do ya have more thoughts on the whole "retroactively grantin agency to female characters isnt always the best thing" thing?

I think this is a three-pronged thing and the points are Lavinia, Helen, and Persephone:

I talked about Ursula Le Guin’s Lavinia some here and specifically responded to that idea, because Le Guin does something really interesting in terms of agency. Lots of retellings function to resist the culture of the myth, a culture in which women, mythical or real, are not supposed to have power or agency or ability to make their own choices or take action. So they give the character the agency to stand outside of the text and chafe against those shackles. And Le Guin says that’s impossible, the character only exists within the text. She’s not imprisoned by the text that denies her agency, she IS the text. It’s not that Lavinia has no agency because she’s a woman, it’s that she has no agency because she’s a character. Aeneas equally has no agency. (I think this approach works specifically well with Vergil because the Aeneid is just Like That in terms of fate and the power of the author and the gods, not sure how it would go to come at Homer like that, although Helen in the Iliad does seem strikingly similar to Vergil’s Aeneas and Le Guin’s Lavinia in that regard, simultaneously able to look at the text as if from the outside and unable to separate herself from it and aware of her inability to escape it.)

And Helen really embodies how agency is sometimes equivalent to blame. Someone in this story did something wrong. Either Paris (and/or Aphrodite, by forcing Helen to fall in love with him) committed the wrong by abducting a woman against her will, in which case Helen did nothing wrong and was merely a passive figure and it’s Paris (and/or Aphrodite) on whom the blame for the Trojan War rests, or Helen went willingly with him and thus committed the wrong herself and is therefore to be blamed for all the men who died at Troy. To say that Helen has agency, has the ability to make her own choices, is to say that she actively, freely, and knowingly made the wrong choice and is to blame for it. And this is a conversation that has been happening since antiquity! Gorgias argues that Helen possesses neither agency nor blame. Stesichorus comes to the same conclusion, denying that she was in possession of agency or is deserving of blame. His denial that she has agency is an assertion that she is not the villain in this story. Agency doesn’t do much when you cannot change what happens in the story and who is harmed by those happenings and the only thing you can really ascribe is blame when you decide who wanted those things to happen as they did or who caused them.

And Persephone is the other side of what it means to add agency when you cannot change what happens in the story but you can change who wants it to happen. Because to give Persephone agency in her story is to turn a story of rape into a story of romance. The only way you can have it so that she is in control of her own story is to say that actually she wanted her rape and abduction to happen. And I have said a LOT on here about that at this point but what I want to emphasize is that it’s okay to tell a story about a woman who does not have agency. It may even be a more important story to tell. @chthonic-cassandra talks some about agency here and @teashoesandhair makes a corollary point that I think is important: that to insist that Persephone is the agent of her own descent into the Underworld “sends the message that a strong woman always has agency”— that a loss of agency is permanent, that to have one’s personhood and autonomy violated at one time permanently strips a woman of them, that once a woman has been raped she can never again truly be the arbiter of her own decisions. And to insist that Persephone must have agency and be an active agent in her relationship to Hades and descent into the Underworld ignores the fact that real women historically were and still are stripped of their agency and ability to make decisions about their own lives and bodies. Is it not also important to tell those stories? Is it not important to acknowledge the reality that rape and assault and abuse and forced marriage happen, and that the women to whom those things happen are still people and still have futures and personhood and autonomy and still deserve stories? Do we not owe it to the ancient women whose experiences went into this story and Persephone’s lack of agency in it, and to the women today who are still reflected in that? It’s the “retroactively” part I want to get into— there’s a reason she doesn’t have agency already. I want to resist the pressure to add agency to this story and insist that Persephone’s LACK of agency does speak directly to a cultural reality in the society from which that story comes, and that same reality still exists in the cultures that read and receive the story today, and that’s important.

(Louise Gluck’s Persephone the Wanderer has, I think, a very interesting and complex reading of the story in terms of agency and where we want to see it and how and why we read for agency or a lack of agency)

#i really need to reread averno i keep coming back to individual poems but it is a full cycle as a whole#also i REALLY need to finally read that aimee hinds eidolon article#it is only an 11 minute read!#but something about eidolon giving a time estimate makes it very hard for me to start any article no matter how short#mine#ask#anonymous#retellings#persephoneposting#this is a torch song#Anonymous

334 notes

·

View notes

Text

toybox mentality

The thing about Milkman by Anna Burns, if it was described in the abstract, is that it might sound a bit dour. A bit unsettling. A bit difficult. This is a book about the Troubles, sometime in the late 1970s; it's written from the perspective of a woman who is being stalked by a man who may or may not be an intelligence agent; and the prose unfolds in long paragraphs dense with clauses. It is lucid, and sometimes exacting. Is it difficult? Kind of.

Certainly it was a surprising choice for winning the Booker Prize last year. 'Experimental' novels are sometimes nominated for that prize but frequently don't win. A Brief History of Seven Killings by Marlon James is perhaps the closest recent comparison – both are historical novels, both have a decidedly post-imperial slant, and both have a playful approach to their own textuality. But that's about where the similarities end. James’s novel was a comprehensive take on a very specific set of real events, shaped a great deal of the creative licence that we expect from historical fiction. It was a big, engrossing novel as they might have recognised it in the nineteenth century. Milkman is a very different beast. A more apt comparison might be with James Kelman's How Late it Was How Late, which won the Booker back in 1994. That, perhaps, was one of the last truly controversial prizewinners, with one of the judging committee threatening to resign if it won.

Bizarrely, wikipedia currently describes Kelman's book as belonging to the 'stream of consciousness' genre, which seems like a peculiar sort of inverse elitism. If we accept that description (though it is more or less meaningless) one might well file Milkman alongside Kelman’s book even though they are written in very different styles. What they do have in common is a certain way of thinking about life as it exists under a state of imperial power and near-constant conflict. The causes of said conflict are so far removed from the lives of ordinary people so as to be rendered incomprehensible to the reader. Clearly there is an occupation of some sorts but how it came about might as well be the stuff of legends. But for both authors, language becomes a refuge for the spirit of the individual, and a means of passive resistance.

There are a couple of mistakes it is easy to make with books of this nature. The first is the 'stream of consciousness' misconception – the idea that in scanning each line we are somehow plugged straight in to the narrator's thinking, talking, acting, being. Joyce has a good deal to answer for in this regard, but the blame oughtn't to be laid at his feet; the problem is more to do with what is done to Joyce than what he actually did, since there is a great deal more to Ulysses than Molly Bloom's chapter. Describing a thing as a 'stream of consciousness' is invariably reductive. It assumes that what we're reading is the sum total of an individual, more so perhaps than if they were telling us a story in a sort of campside voice. And it's a convenient way of treating language that might appear disorderly or unconventional as if it were a kind of aberration.

This leads us on to the second mistake one can make with a book like Milkman – mistaking the music of the text for a written recording of speech. Rather than looking at the words as words, if one takes this approach there's a tendency to become mired in concerns about historical and cultural accuracy. We start to make judgments line-by-line about accents, class, and status. Questions of meaning become sublimated to thoughts of whether or not what we read is accurate. And in most cases the only guide we have for this kind of accuracy is our own prejudice. Language is thus reduced to a signifier of authenticity.

Questions of authenticity sound throughout every page of Milkman. It begins with the title: the 'Milkman' himself is the aforementioned spy-stalker, and not really a milk-delivering-person at all; the narrator is careful to differentiate him from the 'real milkman', a totally different man who actually delivers the milk and maintains an active belligerence towards local partisan groups and, in fact, pretty much everyone in the community. Most of the other characters in the book aren't properly named, and are referred to only in relative terms – from 'maybe-boyfriend' to 'third brother-in-law' and all varieties of familial relations in between. The point is that in this community, naming names puts a person beyond the pale, or worse – but since gossip forms the metabolism of the community, talking about things without using their true names becomes an essential part of everyday life.

This creates a sort of puzzle for the reader. Part of the work necessary is in unpicking the narrator's oblique references to what has come before, and what will come after; we have to work a bit to decipher, to cross-reference. A family tree would have been helpful for the reader, if dangerous for the narrator: we get the impression that all this obscuring with name-confusion is part of the point. The impression is of a text that has been coded for safety. Yet it isn't coded in such a way as to truly anonymise everything. Ireland itself is never explicitly mentioned here, but it would be impossible to mistake this for a book about anywhere else.

This raises a question which I feel entirely unequipped to answer: does this process of un-naming render the book more equivocal than it would be otherwise? I found it hard to find much in the way of politics in Milkman. There's little here of the outright anti-imperialism we can find in James Kelman. Instead, the narrator maintains a sort of light contempt for both sides in the conflict. Their motivations are always obscure. History is expressed mainly in a record of tragedies, most of which seem more or less gruesome and inexplicable. The present conflict is a heap of local dogs with their throats cut by the state forces; it is the scurrilous rumours about a car part from a Bentley, which may or may not bear the British flag; it is the local agents threatening a group of second-wave feminists, before the local women calm them with a show of practical contempt for the ‘toybox mentality’ of the renouncers.

All of this seems horrible and absurd, all the more stark because it is stripped of much of the context that would enable an understanding of how the world came to be like it is. Everyone is about as bad as everyone else, except for the few who aren't. It is all only boys playing with their toys. Another unanswerable question: is the pursuit of this literary effect only a way of side-stepping awkward questions about cause and effect, or is it a sincere representation of how it felt to grow up in such a society? Milkman isn't exactly apolitical, but it doesn't seem especially invested, or interested, in any kind of ideology outside the survival of an individual consciousness.

Black comedy is very much the dominant tone here. At first something will happen that seems as though it's going to lead to disaster until (in most cases) the author slowly deflates the issue. There's a sort of tension between the constant aura of threat and the linguistic thicket thrown up by the narrator's incessant thinking and talking. Language becomes her only means of defense, and sometimes her means of attack. Absurdity is part of the comedy at play, but it's a very specific sort of absurdity. Flann O'Brien feels like a fair stylistic comparison: we have here the same relish in verbosity, that same arch, dilated, expansive use of language.

And yet for all the tension there is no quietude. The narrator is not actually threatened into silence. The overwhelming presence of the text is proof of that. There is no anxiety here – quite the opposite. In life we're given to understand the narrator is bookish and somewhat solitary but in her own story she is in absolute control. This is not a surreal novel in the way of O'Brien. The narrator here is always specific. Words are used to say precisely what they mean, but the narrative could be called a literal interpretation rather than a transcription. To put it another way: we are told exactly what the characters say, think and do, but we aren't told it in their own words. The question of reliability never seems to come up. We trust her, I suppose, because we must trust her. In a meaningful sense there isn't really anyone else in this novel.

Sometimes this feels suffocating. This is a long book: a tad under 350 close-set pages in paperback. It feels its length. I have sympathy for criticisms I've read that take aim at the narrator's tendency to repeat the same adjectives under slightly different names. This kind of repetition, recollection, raking-over (for that is what she does) isn’t the literary maximalism it could be mistaken for; I think it has more in common with a certain kind of minimalism, given the focus on a relatively small, specific quadrant of human experience.

It is exhausting to read because it attempts to be exhaustive. What we're left with is a book which tries obsessively to re-word, re-frame, re-cast a certain very specific sort of strange experience in a strange place in a strange time – a young powerless woman being followed obsessively by a powerful older man. Until eventually the sheer weight of the thing itself – the book – wrenches the situation around until this dynamic of power is neatly, effectively inverted. Would it work if the book weren't so weighty? I'm not sure.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Food rationing + women + frustration = Mobilized women in the political sphere

a) Providing an adequate meal became impossible because grocers raised the price of everything. It is important to note that Francophone housewives lived different than English housewives. Francophone housewives stored food in iceboxes, had larger families, less income causing them to make daily purchases (Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 494). Mundane items accessible to low-income families, such as cabbage and bread, became ridiculously expensive that some families were left to starve. Not to mention, margarine was illegal to purchase. The inflation of price and lack of substitution angered francophone women, urging them to take legal and passive-aggressive action towards the government and grocers. Francophone housewives blatantly boycott grocers forcing grocers to lower thier prices. For example, grocers raised the price of cabbage to 30 cents but dropped the price to 5 cents (Fahrni Magda. "Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940's Montreal", Pg. 493).

b) Francophone housewives also took legal action against the government for restricting the use of margarine. In 1886, Canada banned margarine production because margarine competed with the dairy industry and challenged Canadian morale (Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 496). However, butter was a staple of Canadian diet. Without butter, families were struggling to survive. Seeing the trouble of providing an adequate, francophone housewives pushed for the legalization of margarine as an ample substitute for butter. In 1948, the supreme court ruled that the federal government did not have the right to prohibit margarine manufacture (Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 498).

c) Toronto housewives worked alongside the government, specifically Donald Gordon, to monitor price inflation. In contrast to Francophone housewives, English housewives took aggressive actions against grocers. Donald Gordon appointed Bryne Hope Sanders to lead the 'blue book' agents. Under Sanders' leadership, 16,000 women were recruited to write up against grocers (Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, Pg. 33). As simple as a price difference of 3 cents for pork kidney was reported, forcing grocers to lower their prices and sometimes be fined (Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, Pg. 33). Whether how little or big the complain was, price control was necessary, and the only one suitable to enforce these laws were housewives.

d) Aside from women taking action against price inflation, women also challenged upper-class women's ideals. During wartime, the government gave upper-class and middle-class women the responsibility of educating low-income families about thrifting. Not to mention, the government also published advertisements that displayed upper-class women as the ideal “Mrs. Consumer.” This supposed "education" and ideal “Mrs.Consumer” infuriated low-income housewives because upper-class women did not know what budgeting was, nor were they complying with rationing rules. Margaret Graham Horton published a pledge card (something that upper-class women handed to low-class women while educating) to attack upper-class women for their ignorance and the government for placing a blind-eye on upper-class families (Donica Belisle. Purchasing Power: Women and the Rise of Consumer Culture Pg. 54).

Women accepted food rationing as a patriotic act, but the ridiculous price inflations and bias actions pushed women to engage in economic and political debates against grocers, the federal government, and women. Nearly, rationing made women realize their economic and political potential, forming pre-feminism.

End Notes:

Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Canadian Historical Review 83, no. 4 (2002): Pg. 493-498.

Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013), Pg. 28-33.

Donica Belisle. Purchasing Power: Women and the Rise of Consumer Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), Pg. 53.

0 notes

Text

1. Women + food rationing= engagement in the political sphere

a) Providing an adequate meal became impossible because grocers raised the price of everything. It is important to note that Francophone housewives lived different than English housewives. Francophone housewives stored food in iceboxes, had larger families, less income causing them to make daily purchases (Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 494). Mundane items accessible to low-income families, such as cabbage and bread, became ridiculously expensive that some families were left to starve. Not to mention, margarine was illegal to purchase. The inflation of price and lack of substitution angered francophone women, urging them to take legal and passive-aggressive action towards the government and grocers. Francophone housewives blatantly boycott grocers forcing grocers to lower thier prices. For example, grocers raised the price of cabbage to 30 cents but dropped the price to 5 cents (Fahrni Magda. "Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940's Montreal", Pg. 493).

b) Francophone housewives also took legal action against the government for restricting the use of margarine. In 1886, Canada banned margarine production because margarine competed with the dairy industry and challenged Canadian morale (Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 496). However, butter was a staple of Canadian diet. Without butter, families were struggling to survive. Seeing the trouble of providing an adequate, francophone housewives pushed for the legalization of margarine as an ample substitute for butter. In 1948, the supreme court ruled that the federal government did not have the right to prohibit margarine manufacture (Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Pg. 498).

c) Toronto housewives worked alongside the government, specifically Donald Gordon, to monitor price inflation. In contrast to Francophone housewives, English housewives took aggressive actions against grocers. Donald Gordon appointed Bryne Hope Sanders to lead the 'blue book' agents. Under the leadership of Sanders, 16,000 women were recruited to write up against grocers (Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, Pg. 33). As simple as a price difference of 3 cents for pork kidney was reported, forcing grocers to lower their prices and sometimes be fined (Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, Pg. 33). Whether how little or big the complain was, price control were necessary and the only one suitable to enforce these laws were housewives.

d) Aside from women taking action against price inflation, women also challenged the ideals of upper-class women. During wartime, the government gave upper-class and middle-class women the responsibility of educating low-income families about thrifting. Not to mention, the government also published advertisements that displayed upperclass women as the ideal “Mrs. Consumer”. This supposed "education" and ideal “Mrs.Consumer” infuriated low-income housewives because upper-class women did not know what budgeting was nor were they complying with the rules of rationing. Margaret Graham Horton published a pledge card (something that upper-class women handed to low-class women while educating) to attack upper-class women for their ignorance and the government for placing a blind-eye on upper-class families (Donica Belisle. Purchasing Power: Women and the Rise of Consumer Culture Pg. 54).

Women accepted food rationing as a patriotic act but it was the ridiculous price inflations and bias actions that pushed women to engage in economic and political debates against grocers, the federal government and women. Essentially, rationing made women realize their economic and political potential, forming pre-feminism.

End Notes:

Fahrni Magda. “Counting the Cost of Living: Gender, Citizenship and a Politics of Prices in 1940’s Montreal”, Canadian Historical Review 83, no. 4 (2002): Pg. 493-498.

Graham Broad. A Small Price To Pay Consumer Culture on the Canadian Home Front, 1939-45, (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2013), Pg. 28-33.

Donica Belisle. Purchasing Power: Women and the Rise of Consumer Culture (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020), Pg. 53.

0 notes

Text

william golding, gender, and the historical context of lord of the flies

OK, thanks to the proposed all-female remake of Lord of the Flies, I’ve been seeing a bunch of Discourse about LotF on my dash. And to provide some useful factual information for those conversations, this post is my attempt at filling in the historical context that suggests that Golding really, really was implicating British imperial masculinity in Lord of the Flies.

As p. much everyone knows from all those posts that have gone viral, Golding wrote LotF in response to The Coral Island, a 19th century novel for boys by British author R. M. Ballantyne, in which three boys shipwrecked in the Pacific succeed in bringing some modicum of “civilization” to the “savages” around them before returning home

The Coral Island was supposed to provide young British boys with a model of British imperial boyhood

In the preface, the narrator declares, “I present my book specially to boys, in the earnest hope that they may derive valuable information, much pleasure, great profit, and unbounded amusement from its pages.” (emphasis mine)

In his account of his time as a member of the British imperial machine in Canada, Ballantyne declared it “the duty of Christian Britain” to send out (male) missionaries to ~civilize and Christianize~ the natives; The Coral Island was just a different version of the same trick, an attempt to recruit boys for the empire through fiction rather than nonfiction

The book was a classic in male British boarding schools (for instance, one article in an early twentieth century publication for teachers listed it as among ideal “Stories for Boys in Easy Style”)

In these single sex schools, young British boys were indoctrinated into the British imperial mission, carried out by upper class white Englishmen like them, who supposedly represented the pinnacle of civilization and were uniquely capable of spreading their ~civilized ways~

LotF itself depicts the ways in which reading practices were gendered in this period (and therefore books like The Coral Island were uniquely designed to provide British men with a suitable education), when Ralph notes that he never read a “bright, shining” book on his childhood bookshelf because “it was about two girls,” but instead read books with titles like The Boy's Book of Trains, The Boy's Book of Ships, and The Mammoth Book for Boys

William Golding was deeply familiar with the ways in which single sex boarding schools imposed this imperial British masculinity on pupils: he both studied at one such school and taught for many years in another

In this specific strain of literature of empire, women were not depicted as the primary agents who spread British civilization

In The Coral Island, the only significant named female character is an islander who is converted to Christianity by male British characters and becomes a passive damsel whom they save

Describing his experience of the (primarily male) work of British imperialism in Canada, Ballantyre wrote that “throughout this immense country there are probably not more [British] ladies than would suffice to form a half-a-dozen quadrilles” (= roughly two dozen, for those curious as to what that implies)

Ballantyre declared that the only real roles in the machinery of British imperial expansion for any women present were those of “tailors and washerwomen,” who could “make all the mittens, moccasins, fur caps, [and] deer-skin coats”; if officers sent for their wives, they arrived (often unhappily) long after the process of ~civilizing~ had begun

Discussing his own decision to write about young boys instead of girls, William Golding said that he believed that “if you land with a group of little boys, they are more like scaled-down society than a group of little girls would be ... you cannot ... take a bunch of them and boil them down, so to speak, into a set of little girls who would then become a kind of image of civilization, of society”

I’d suggest that this remark is best understood in the context of British imperial masculinity, and not solely as a statement about gender in the abstract: little British boys were supposed to be the perfect “image of civilization,” were supposed to be the ones who reproduced new “scaled-down societ[ies]”

This kind of lit isn’t my field of expertise, but Alan Frost’s “The Pacific Ocean: The Eighteenth Century’s ‘New World’” and Joseph Bristow’s Empire Boys: Adventures in a Man's World are good places to start if you’re interested in the cultural dynamics of British imperial masculinity; I’m more familiar with how imperial femininity was formulated in French and American contexts, so I’ll defer to anyone who actually studies that, but suffice to say, British women were not figured as active ~civilizers~ in Ballantyre’s work, and are present solely as assistants in the background whose activities are dictated by men, while non-British women are ~objects to be civilized~

Lord of the Flies, which was written during the decline of the British Empire in the 1950s, rejects this cult of imperial manhood, in which young boys are supposed to be perfectly trained to grow into the sort of white British men who would “civilize” colonies. Instead, the book depicts a group of young boys failing to be perfect missionaries of British civilization and instead revealing the violence inherent in the brand of toxic, imperialist masculinity in which they’ve been raised

The class markers and references to gendered reading practices (as discussed above) imply that the boys in the novel attended one of those upper class boarding schools, where the ethos of British imperial masculinity was supposed to have been inculcated into them, making them both the ideal exemplars and transmitters of ~civilization~ - two roles they utterly fail to fulfill

It is therefore no accident that at the end of the novel, the naval officer says, “I should have thought that a pack of British boys - you're all British, aren't you? - would have been able to put up a better show than that” (emphasis mine)

He also specifically suggests that their experience must have been “like the Coral Island” - an intentionally ironic juxtaposition

Look, you could try to argue that a contemporary adaptation is within its rights to change the story and attack some new cultural institution, instead of British imperialist masculinity, in order to make its point. Maybe, although I’m not convinced, the two guys creating it are trying to offer new commentary on the role of women in contemporary imperialist contexts. You could evaluate the casting news separate from any discussions of themes/interpretation and argue that Hollywood needs to offer more roles for actresses and this is progress.

But pretending that the original novel wasn’t specifically responding to the idea that little British boys were uniquely trained to absorb and replicate the British Empire ignores the original context of the work. Pretending that switching the gender of the protagonists doesn’t change that message ignores all the ways in which British imperialism was heavily gendered. It ignores the extent to which this text about a bunch of white British boys failing to establish ~civilization~ on an island in the Pacific was written in a cultural context in which the trope of ~white British men civilizing Pacific islands~ was an omnipresent image of empire. From Robinson Crusoe to Gulliver’s Travels to the journals of James Cook, the Coral Island to Lord of the Flies, any work written and read in this hegemonic context cannot escape the cultural history with which it is freighted. Those aren’t just texts about how humanity establishes civilization: they are texts responding to a history of the world in which white men claimed to adopt the “burden” of “civilizing” the rest of the world and modern Western speculation about ~the nature of humanity in the wild and the start of civilization~, from Locke to Rousseau to Golding himself, has always responded to these inescapable global power dynamics (if reading this makes you angry, go read Larry Wolff’s “Discovering Cultural Perspective: The Intellectual History of Anthropological Thought in the Age of Enlightenment” in The Anthropology of the Enlightenment and then try to claim that Enlightenment era conceptions of how human nature developed into human civilization weren’t shaped by their imperialist context). I’m tired of seeing people and thinkpieces suggest that ~those feminists haven’t even read the book~ and ~Golding was really just writing about human nature~; they ought to read the book themselves and do a little reading on its publication history.

#lord of the flies#sexism#the coral island#william golding#lord of the flies movie#history#the discourse tm#scheduling this post for a more reasonable time of day lol#racism tw#imperialism tw#long post

253 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meta Repost Project: Fandom Studies and the Personal Favorite White Boy

(note, this is an article I originally posted on therainbowhub and fandomfollowing two years ago but has been lost to caches and bad decisions on my art. Here it is again, non-caches and in full. This article has some errors and is out of date, but I wanted to preserve the original even if it is flawed. It works well as a reference and I may add/alter it again, but I wanted to post is and have it here, untouched, first)

This one’s gonna hurt…

Personal Favorite White Boy (n.): A (usually white) male character who can commit acts ranging from “pretty damn douchey” to “outright atrocities”, but is constantly defended by or stanned for by a furious fan base who will go to any lengths to excuse their actions and vilify critics. A male fave who is portrayed as a precious cinnamon roll who are only ever victims and heroes, and anyone who says differently is evil or illiterate. Who will have their fangirls who “understand” them furiously warp their characters, outright ignore their flaws, and attack anyone who points out anything remotely negative about their faves. Any woman who rejects them is an evil bitch, as is anyone who dares to hold them accountable for their actions. Everything they do is justifiable due to past abuse, “true love”, or a protective instinct. The figure from which Draco in Leather Pants, along with other modern fandom tropes, has spawned.

Fifty Shades of Grey fans will dox you online for saying Christian Grey is an abusive stalker despite the fact that he tracks a woman through her cellphone and uses faux-BDSM to hurt his wife for the crime of going out for drinks with a friend.

Twilight fans will lose their shit if you point out how not-okay it is that Edward Cullen took a piece of Bella Swan’s car engine out to keep her from going to see Jacob. Or if you make the point that Jacob forcing a kiss on Bella is, in fact, sexual assault.

You’re a total simpleton if you think that Thomas Raith from the Dresden Files is rapist. Sure, he uses magic to compel humans into having sex with him, but he acknowledges he’s a monster and also consent doesn’t matter to vampires! He’s a hero because he feels bad about it. Can’t you just understand context?!

If you dare to mention that you’re not supposed to stand with Ward (or you get shot in the head because he’s a traitorous neo-Nazi rapist), some Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. fans will want your blood.

Finn Collins from The 100 has great hair and calls the lead female character Clarke “Princess”, but he also killed nearly twenty unarmed men, women, and children. That makes him a war criminal and the Grounders wanting him dead as an offering to insure their peace treaty (the one that will likely insure the safety and health of hundred, if not thousands of innocents) is pretty reasonable. As is how the lead character, Clarke, stabbed Finn to spare him a torturous death. But some fans of The 100 insist that Clarke is “a bitch” for doing this and not killing Grounder leader Lexa— even though that would surely result in the deaths of everyone she’s ever loved.

…I know, right? It’s maddening. How much media utterly idolizes men even if they’re shits? Or at the very least problematic?

These men— the Grant Wards, the Spikes, the Finn Collinses, the Tyrion Lannisters, the Edward Cullens—- are the Personal Favorite White Boys, and they get psychotic fandom defenses more passionate than anything. These PFWBs will be absolved of anything— be it rape, abuse, massacres, mistakes that lead to the violent deaths and starvation of thousands— by certain fans with defenses going from “He was abused as a child” to “He cried once.”

Which brings us to the first prong of my theory regarding the rabid Personal Favorite White Boy Defense phenomenon: male characters in media, agency, and our changing views of what we view as acceptable and unacceptable.

First, there are the roles of female characters in stories, and how the primary actors or aggressors in most stories are men.

Men were almost always the active players. Even in stories that feature main female protagonists, such as Snow White and Sleeping Beauty, those main female characters are so passive to the point of unconsciousness— and need to be saved by men in the form of what is considered modern day sexual assault.

But men were the primary agents, the true heroes, and so they had actions that could be judged for good or ill– choices they actually made. Whereas even the females’ characters choices were usually framed as a thing they did because “they couldn’t help it.” Still utterly passive, with no agency. So there is no instinct to defend female romantic leads in text much because there was never a real need. Even when they were objectively messed up people, they were always framed as a prize and their flaws had more to do with them being weak and dependent than letting us see their own choices and real motivations— think Daisy Buchanan (who was awful, but very much built up simply as an object rather than a person). So there simply has never been much encouragement for men to feel like they need to justify their fictional crushes. Once a woman did something bad, it was done. She was just bad. But she was always, always passive and always an object. There are some exceptions, of course, but often even those stories are altered or ignored. Compare and contrast how the stories of Joseph and his coat of many colors or David defeating Goliath are well known and publicized. Meanwhile few people could tell you much of Judith, who saved the Hebrew people by slaying the Assyrian general Holofernes.

In modern media, we’ve improved by increasing the actions of female protagonists, but in a world where the ratio of male to female characters in mainstream film is 2:1 and The Bechdel Test actually has to be a thing, we’re still used to having women as non-entities.

And that’s the narrative tradition we have. So while we can up female agency, men are pretty much NEVER without agency, even in woman-centric media unless it’s aimed at little girls. Men are still very often the heroes, the aggressors, the people who take active part in everything and have real choices to examine. And since we’re encouraging more progressive views, it means that arguing of the morality regarding men becomes far more complicated and nuanced.

Look at the changing views of characters like John Harker or Heathcliff, or any Byronic hero. Once they were an ideal, but now that our lens has changed, particularly when it comes to romantic/sexual matters, heroes get challenged in a new way, and are challenged to their potential romantic audience— primarily women. So the pressure is on the women to justify their fictional romances.

As said before, we’re used to, and comfortable with, judging women both fictional and factual. Women are encouraged to defend men, and expected to do it now with the rapidly changing social views that we have. And unfortunately, while the complex issues of things like personal autonomy, consent, and justice have been progressing, there are many people who are still woefully uneducated about certain issues. For instance, when I wrote in a blog post how in the A Song of Ice and Firebooks, the character of Tyrion Lannister molests his crying, terrified, twelve-year-old POW of a bride, I had a very sweet teenage reader go, “Wait, Tyrion rapes Sansa WTF???” When I replied that no, I said he molests her, the young woman asked, “Wait, are molestation and rape not the same thing?” She seemed pretty happy to learn this, even though she, like all other young people out there, deserve to have learned this at a much younger age.

We still have a ton of women these days who don’t know that sexual assault encompasses more than rape, that consent can be revoked, and are still heavily influenced by rape culture and sexist ideals. People who still think it’s not abuse unless the boyfriend gives his girlfriend a black eye. Who don’t understand that S&M is meant to be built upon clear, informed consent and communication.

So as a result, when you point out to someone that taking apart Bella Swan’s car engine totally qualifies as abuse, you have many fangirls who are shocked and furious. To them, domestic abusers are drunken stepfathers in wife beaters breaking bones, not well-dressed, sophisticated, “protective” Edward Cullen.

When you say that Christian Grey is an abuser since he manipulates ridiculously-innocent and ignorant Anastasia Steele into a “BDSM” relationship and continues it even after it’s confirmed that she doesn’t understand concepts like butt plugs and orgasm denials, then shames her for using the safe word (which is, like, a totally normal thing to use), they become enraged.

When you mention Damon Salvatore raped someone, the response is often, “But she expressed interest in sleeping with him! They flirted!”

Now, everyone is happy to judge women, but rarely to ever examine their choices. Those judgments have always been simple: Virgin/Whore.

There’s never been any sort of need for men to try and justify their romantic choices, partly because heroines were so bland so often, portrayed as objects not people, and you can’t really examine the morality of an object that doesn’t make real decisions. Whereas male characters have historically always had agency.

But men aren’t objects. They are the people who, historically, have controlled the world in really messed up ways and we’re coming to realize that. So women will have put emotional stock in a character, and now are pressured to examine a male character’s choices in a way that men haven’t really had to, especially not through a lens of characters they find attractive.

For instance, guys will talk your ear off about how much Bella Swan from Twilight sucks, but were they ever in a position to get emotionally attached or attracted to her? No. Female characters are either identifiable with women or just titillation or prizes for men. Bella Swan was never meant to be lusted after or won by a male audience. Whereas women throughout history have been actively encouraged to think of Heathcliff or whomever as a romantic interest, and now that sort of thing is being challenged. Women are encouraged to be on the defensive about their romantic/sexual feelings, and that is their default setting.

Let’s face it: throughout history, those things that have been viewed as appealing to women, especially young women, are often denigrated and seen as “lesser” pieces of art than those marketed or made by men.

Sure, the word “fan” originally comes from the word “fanatic”, but that seems to only get recognized when women are involved. Male fans are just that— fans. Female fans are half-fan, half “lun-ATIC.” And no amount of football riots, soccer riots,hockey riots, or actual history will do much to dissuade people of this idea.

When Elvis Presley and The Beatles took over the popular consciousness, much was made of their legions of screaming fans— most of them young women. These “Beatlemaniacs” were a joke, a joke which ended up extending to the band itself.

Today, The Beatles are seen as one of the most important, artistically capable, and revolutionary musical acts of all time. Whereas before, during the height of Beatlemania, critics were quick to make snide remarks about their lack of artistic merit. “Is this the King’s English?”, one snide reporter wrote. They were seen as nothing but mop-topped sex symbols…

…Right.

Indeed, fangirls have had to defend their media preferences for a very, very long time– just as much for modern media as classic works. Plenty of people these days will sneer at a “feminine” love for classic knightly tales of chivalric romance— “All that stupid fairy tale romantic BS. That’s not how it was in the real Middle Ages!”

Granted, it is true that the knight in shining armor trope isn’t exactly historically accurate. But what many people seem to forget was the context under which many of these fairy tales and stories of courtly love were written. These stories were not just written to make naive women soak their petticoats. In fact, many of the codes of romantic chivalry were established by and for men in order to instill a more sustainable and less chaotic way of life for men at arms— a way of giving knights a code in order to keep any guy with a sword from randomly slaughtering and raping everyone he encountered. Indeed, many fairytales and fantasies— from Snow White to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight— were written with the intent of positively influencing and representing the cultures that spawned them; they were not only entertaining and educating their contemporary audiences, but serving as significant historical and social texts for people to study today. “Fairy tales” and myths of knights and ladies have huge academic and intellectual significance to the modern day. And yet, many call it “Fairy tale bullshit.”

As a result of this cultural bias, women just naturally feel the need to automatically be on the defensive about things they like, regardless of the artistic merit of said media. This includes the need to justify almost any sexual/emotional/romantic feeling they have for a male character. Men? Not so much.

We’re just not used to questioning the agency of men. We’re supposed to accept men as heroes and accept what they do “for love.” We have to always make excuses because they’re men being men. Women should be prizes for these men. And we should stand by our men.

Unfortunately, there are changing standards for acceptable behavior. What does and doesn’t count as sexual assault. What does and doesn’t count as stalking. What does and doesn’t count for abuse. What can and can’t be excused on the basis of age or history of abuse. Edward Cullen was “protecting” Bella. Grant Ward was abused as a child. Finn Collins was traumatized and was desperate to find Clarke, who he was in love with. Christian Grey is just into S&M.

Any excuse must and should be found. Or certain actions should just be brushed aside as no big deal, especially if they did it “for love” (often the excuse with Finn Collins defenders).

Now, it’s true that certain Personal Favorite White Boys are in fact characters with complexity. But the strange thing is is how often those very complexities that are praised by fans are in fact erased via white-washing, all while female characters are vilified for infractions as horrible as “crying too much”, “not falling in love with the guy who wanted her”. Tyrion Lannister from A Song of Ice and Fire is a great example (known more popularly by his show counterpart, who has most if not all of the character’s flaws erased… Yeah, the Personal Favorite White Boy can be extended to dudebros like David Benioff and D.B. Weiss making “adaptation” decisions as well). He’s a severely messed up person who has moments of great compassion and courage, but also sometimes does horrible things. This is not because he’s pure evil, but because the man is completely warped. But that does not make excuses, validate, or erase the horrible things he does. They do not make him a good person. Tyrion is still a character with agency, and oftentimes he uses that agency to do awful, awful things.

And if you bring that up, you’re an ableist douchebag who thinks people who have been abused should just “get over” things.How dare you call the man who willingly married a twelve year old POW selfish and sexist! His Dad was the one who offered him that marriage (along with another match as an alternative, with no threats of violence), and his dad has abused him, so therefore Tyrion did no wrong!

Just like Thomas Wraith can’t help hypnotizing people into sex, because he’s a vampire and vampires in the Dresden Files don’t care about consent.

It’s okay as long as he acknowledges that he’s a monster.

Even when a guy is a rapist, neo-nazi terrorist, the fact that his father beat him means #IStandWithWard.

That is not to say that all fans are like this. Nor is it to say that there is something necessarily wrong with having a problematic fave— as long as you acknowledge and don’t try to white-wash these things. There are tons of fanboys and fangirls who are perfectly ready and happy to admit the faults of their characters, gleefully call them “shitheads”, and examine the issues at play in the media they consume. But unfortunately, the Personal Favorite White Boy phenom is great enough that it sort of sets the stereotype for empty-headed female fandom (which, by the way, is bullshit).

This mentality comes from a strong social background. One in which we are expected to find reasons and explanations for the heinous acts committed by white men. Where the Aurora shooter was described as bullied and mentally ill, and will be nonviolently taken into custody for a life sentence after killing a dozen innocent people; where Jeffrey Dahmer is given due process and only restrained during arrest after killing and eating several people, but Walter Scott is shot point blank for running and 15-year-old Dejerria Becton is forced to the ground because of a noisy pool party. One where women are not expected to have agency. One where rape culture and bigoted social mores are institutionalized. Where women expected (and are expected) to be judged for everything. Where women in media are sex objects, so there is no urge for the heterosexual males who want her to feel the need to defend her actions or choices. Meanwhile, women are actively encouraged to feel persecuted or defend “their men” no matter what. Where they’re automatically defensive because female audiences are so automatically looked down upon, and where media is being constantly re-examined through a rapidly evolving social lens. Where the issues of sexual assault and consent are so poorly explored and communicated that there are tons of people who still don’t get that hypnotizing people into having sex with you is still rape.

As a result, we’ve produced the culture of #IStandWithWard.

And then there’s just how female fans in general are treated– but that’s a different article.

(This is the first in a series of articles exploring fandom and its idiosyncrasies. Tune in next time, when Wendy deconstructs all the reasons fangirls are so automatically defensive of everything in the first place!)

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beyond Polarity: A New Encounter between Women and Men by Elizabeth Debold

The essence of the masculine and feminine polarity, then, is attraction: opposites attract, so we say. Magnetic poles, electric current, the workings of the atom are all examples of the force of polarity. Breaking the bonds forged from the polarities between atomic particles creates a nuclear explosion. “Sexual attraction,” explains David Deida, “is based on sexual polarity, which is the force of passion that arcs between masculine and feminine poles.” Or as he continues, “you always attract your sexual reciprocal,” so that in sexual passion “you need a ravisher and a ravishee,” or what he sees as the masculine and the feminine. While Deida says that we can change our role as ravisher or ravishee every day if we choose, “most men and women also have a more masculine or more feminine core,” respectively. So, if the way that we tend to think about ourselves as women and men is that we possess relatively immutable interiors that are (or should be) feminine and masculine, then the undercurrent of communication will be this polarity of sexual attraction. Sexuality is the subtext.

This has serious implications for communication between women and men. In a chapter entitled “Women Are Not Liars,” Deida explains that, in emotional situations, women cannot be held accountable for the truth of what they say: “The ‘truth’ of the feminine is whatever she is really feeling, in this present moment.” (Italics in original.) Given that women are defined as emotional by nature, that is, according to the polarity in which rationality is masculine and emotionality is feminine, I would imagine that it’s difficult to know exactly where to draw the line in terms of when to take what a woman says seriously and when to just “listen to her as you would the ocean, or the wind in the leaves.” Deida gives men a helpful guideline to figure this out:

The basic rule is this: Don’t believe the literal content of what your woman says unless love is flowing deeply and fully in the moment when she says it. And even then, know that she is probably talking about her current feelings, not necessarily about the subject of whatever she is talking about. Never base your plans on what your woman says she wants to do, unless she is in the full flow of love when she says it. And then, expect her to change her mind at any time when her feelings change.

The gist is that a man should never trust what “his” woman says, because it is only true as long as she feels it. He advises men to listen deeply (hearing her words like the babbling of a brook?) and try to distinguish between her “shifting moods [which can be discounted] and her sensitive wisdom,” which he never explains. Throughout the book, Deida explains that women’s moodiness or bitchiness is usually a signal to the man that she needs to experience his presence and strength or, in other words, he should schtupp her immediately—on the kitchen table, on the floor, take her down wherever she was standing. This is called “f***ing her open to God.” Deida’s roots in the Pick Up Artist community are showing: the subtext is conquest, constant conquest even in the context of a committed relationship. Apparently, real communication between men and women is basically a process of reinterpreting verbiage as a desire for submission—because women don’t mean what they say anyway and what’s really going on is getting it on with each other.

Putting aside the “date rape” overtones of Deida’s advice to men, the most damaging part to me is the view that one cannot expect rationality or accountability from women. The identification of the feminine, or women, with feeling and the non-rational raises questions for me about communication between the sexes. In Deida’s assumption that women in intimate settings should not be taken at their word, the interpretation of what women actually mean is left to the man. The woman is left wordless. I don’t doubt that many women struggle to articulate their experience and desires in relationship, particularly if men choose, as Deida suggests, to engage with women who are their “complementary opposite.” If an older, mature man then selects a woman who is younger and less developed, then being a superior man, or at least a man who is superior to “his” woman, is fairly guaranteed. Admittedly, too, women’s historical role in the emotional give-and-take of care-taking and lack of engagement with intellectual life has had an impact on contemporary women’s sense of being female. At the same time, men’s historical absence from the domestic space of care has left many nearly tone-deaf to the music of emotional intimacy. But not expecting women to say what they mean and mean what they say places women outside the expectations for adult discourse. It turns women into children.

The laundry list of opposites that are contained in the supposed masculine-feminine polarity—reason vs. emotion, active vs. passive, agentic vs. receptive—have a dangerous subtext of adult vs. child. We expect children to be emotionally driven (and later to develop reasoning capacities), to be passive and directed by their parents and teachers, and to receive guidance so that they can develop into independent agents who direct their own lives. In Deida’s polarity, women stay as children, whose spunk and wildness (read: childlikeness) drive his “newly evolving man” wild.

This is nothing but retromodernism. Modernity divided society into the masculine public sphere and the feminine private sphere, each inhabited by “opposites.” The gulf between these two polar opposites was as unbridgeable as the superiority of the masculine over the feminine was undeniable. The effect was disrespect. Men could have sympathy and protective feelings for their womenfolk, but not the kind of respect one reserves for an equal. But likewise, men’s unavailability and cluelessness about the delicate nature of relationship led to women feeling emotionally superior to men. Polarity is not partnership. Opposites attract, yes, but in a context in which the dynamic of dominance and subordination sparks passion. In such a social space, the subtext is always sexual, and men and women come from, and end up on, different planets.

Ultimately, communication between women and men who are embodying this opposition ends up being merely superficial. Even though these are deep grooves in our culture and consciousness, this opposition is not an expression of the depth of who we are. Deeper than our personality, sexuality or cultural role is our shared humanity—the truth that the entire range of qualities and capacities that have been divided by gender are all aspects of our selves. From the unity of the being that we share, and each accountable for the complexity of making meaning from our experience, a new capacity for communication can become possible between men and women. No longer opposites, the creative work of embracing and integrating differences reveals a new potential for being human together.

0 notes

Text

Beyond Polarity: A New Encounter between Women and Men by Elizabeth Debold

Apparently, when it comes to conversation between women and men, I might be. At least according to some in the spiritual and Wilberian integral world. Since 2006, when Wilber published Integral Spirituality, his integral theory has included “masculine” and “feminine” as types of individual interiors—which is supposed to indicate a basic orientation to life that is persistent across levels of development. While many give lip service to “masculine doesn’t mean ‘man’ and feminine doesn’t mean ‘woman,’” pretty much of the time we use masculine to indicate things or aspects of self that are socially appropriate for men, and the same goes for the feminine. Wilber himself often uses man, male or masculine (or woman, female or feminine) interchangeably. Even though both women and men can and do express both (of course we do—they are, after all, human capacities and qualities), I am referring to the normative use of these terms in which men are supposed to be masculine and women, feminine. Masculine and feminine are often seen as representing a polarity, like opposite poles of a magnet that attract each other.

What happens to communication when this polarity is mapped onto living, breathing human beings, male and female? That is the domain of Wilber’s erstwhile friend and colleague, David Deida, who in his book, The Way of the Superior Man, helps those with masculine essences understand how to have a satisfying, passionate relationship with the feminine essence—primarily for those in relationship, but also for those who are on the lookout for one. Of course, this requires communication. What kind of communication is possible between individuals whose identities are rooted in ideas of masculine and feminine? From my view, using the masculine and feminine as the context of meaningful conversation between the sexes is as misguided as the TV doctor’s attempt to appropriate my passion. Inherently, it does not create the mutual respect needed for co-creative engagement between women and men.

I’ve written quite a bit questioning why evolutionary integralists so often gravitate toward the common (read: stereotypical) usage of “masculine” and “feminine.” To me, dividing fundamental human attributes in two and giving half to women and half to men as polar opposites is a throwback to a much earlier time. To put it more precisely than Freud, this makes your genitalia your personality. The sex act itself becomes the determinant of one’s core self: active/agentic or passive/receptive. Hormones, neurology, and brain function are all brought in to lend an air of biological determinism to these stereotypes. Of course, there are profound historical reasons, based in the differences between women’s and men’s biological roles in reproduction, that lay the ground for differences between men and women. But at this point in time, among those of us aspiring integralists, the idea that these polarities should govern interactions between women and men is a form of retro-modernism rather than an integrative, integral perspective. Moreover, upholding this polarity as fundamental to who we are as men and women makes sex and sexual attraction the subtext for all of our interactions.

0 notes