#joachim friedrich quack

Text

youtube

In this talk from the 2022-23 edition of the Herodotus Helpline, Alex Tarbet (Michigan) explores the impact of various Egyptian adventure stories and other tales drawn from oral folklore on Herodotus' Histories. As part of the talk, Alex looks at The Blinding of Pharos, preserved in both Demotic Egyptian (~3rd century BCE) and Herodotus’ Greek (5th century BCE).

Source: the youtube channel of Herodotus Helpline

Alex Tarbet is a PhD candidate in Classics and Sylvia 'Duffy' Engle Graduate Fellow at the University of Michigan (https://lsa.umich.edu/humanities/people/2022-23-fellows/alex-tarbet.html). According to the information given on his dissertation by the University (https://lsa.umich.edu/classics/people/graduate-students/language-and-literature-graduate-students/coleem.html ):

Alex studies humor at the expense of tyrants and authoritarians as it passed among storytellers of Greece and Egypt. His dissertation, Worlds Upside Down: Egyptian Folk Humor and Herodotus, explores comic anecdotes about the pharaohs Egyptians performed for Herodotus as he traveled along the Nile in the 5th century.

Good video, very similar to the text of the same author on Egyptian cats and Herodotus that I have reproduced almost one year ago (https://aboutanancientenquiry.tumblr.com/post/670193035428184064/herodotus-and-the-egyptian-cats ). But I think that Tarbet’s passion for the “decolonization’ of the Classics leads him too far when for instance he says that Aristophanes is a “huge celebrity” just because of an “accident of colonialism”!

Now, more particularly concerning Herodotus, I have the objection that Tarbet approaches the question of the Egyptian sources of Herodotus and of their agendas almost exclusively from the point of view of his specialty, which is humor and power in Egypt and Greece. I think that this is a real aspect of the story about what Herodotus heard from his Egyptian sources, in which there were for sure some tales with a humoristic element in them, but not the whole story. I think also that the question of the relationship of Herodotus with his Egyptian sources and the nature and degree of the historical consiousness and the agendas of the latter deserves a deeper approach and study. Moreover, I don’t think that describing Herodotus as a “tourist” conveys a very accurate picture of the reality: if it is true that Herodotus visited Egypt for a relatively short period of time, it is undeniable that his pursuits in Egypt were scholarly, not those of a modern “tourist” (and the more general ambience in the Egypt of the 440′s BCE, when Herodotus must have visited the country, was not particularly jovial and tourist-friendly, as it is generally accepted that the Persian rule of Egypt had become far more oppressive after the revolt of 460-454 BCE, which ended with the crushing defeat of the revolted Egyptians and of their Greek allies).

Now, the author who contributed the most to the discovery of the similarities about which Tarbet talks between what Herodotus records on the pre-Saite history of Egypt (before 664 BCE) and the Egyptian Demotic tradition is Joachim Friedrich Quack, German Egyptologist, Demotic language specialist, and professor of Egyptology at the University of Heidelberg (see in German J-F. Quack Einführung in die altägyptische Literaturgeschichte III. Die demotische und gräko-ägyptische Literatur, 2, Berlin 2009, and in English Joachim Friedrich Quack- Kim Ryholt Demotic Literary Texts from Tebtunis and Beyond, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2019). So, I think that it is important to see what conclusions drew from these similarities Pr. Quack.

First of all, as I have showed in an older post of mine, Quack believes that the similarities between Herodotus’ Book II and the Demotic Egyptian literature prove that Herodotus did have an important degree of knowledge of the Egyptian tradition, and therefore what he writes about Egypt is not some aggregate of lies or of arbitrary products of his own imagination, as some people foolishly claim on this site (see https://aboutanancientenquiry.tumblr.com/post/701378423007952896/egyptology-professor-j-fr-quack-on-herodotus ,with the further link to the entirety of Quack’s original text in French). As Pr. Quack says ( the translation to English is mine):

“Although it is undeniable that Herodotus is capable of modifying certain details in order to make them agree with his own way of thinking, this can by no means change the overall picture: Herodotus shows such a precise knowledge of the Egyptian traditions and realities that it is difficult to not admit the reality of the visit to Egypt of the “father of history”. The “Liar school” 98 which denies this visit is explicitly refuted. Also the tradition of research which sees above all in the relations of Herodotus with foreign peoples a mirror effect putting into relief their otherness in comparison to the Greeks, without taking enough into account the realities 99, is proved to be inadequate to deal with the complexity of the work of the historian from Halicarnassus.”

Moreover, Quack believes that Herodotus’ account of the pre-Saite history of Egypt is not the product of misunderstanding from Herodotus’ part of jokes of low rank Egyptian priests (or “priests’) or more generally of Herodotus’ confusions, but reflects rather the confusions and distortions in the historical consciousness of the Egyptian priests of his time (see again https://aboutanancientenquiry.tumblr.com/post/701378423007952896/egyptology-professor-j-fr-quack-on-herodotus , with the further link to Quack’s text). As Pr. Quack puts it (the translation from the French original is again mine):

“Herodotus often refers to what he has heard from Egyptian priests 96. The demotic texts that I have presented here originate largely in a priestly milieu, as it is showed clearly enough in the papyri of Tebtynis. This makes also abundantly clear that the traditions on the Egyptian past and the exploits of the heroes, which have often been characterized as “folkloric” 97, have a solid basis in the stories circulating among the priests of Late Egypt. And where Herodotus’ narrative seems to us strange, concerning the anecdotes on the Egyptian kings or their order of succession, it would be appropriate to impute this strangeness less to the errors and misunderstandings of the Greek historian or to the fancies of uncultured guides than to the confusions which had been already produced during the long transmission of the Egyptian culture.”

PS: To my great amusement, I see that Alex Tarbet’s video on the youtube channel of Herodotus Helpline is used by some people on tumblr in order to vindicate the anti-Herodotus campaign of the gang of tumblr egyptologists or, in some cases, “egyptologists” (you know, the “Herodotus is my bitch”, “Fuck Herodotus”, “Fuck Herodotus and fuck yourself”, “most misconceptions about ancient Egypt can be traced back to Herodotus’ Greek ass” etc etc graceful and scholarly ladies, and their sycophants, maids, and ignorant and fanatical fanbase). I think that what I have written above is a sufficient reply to their ridiculous claims. But, just for the sake of completeness, I will return in some days with a more detailed post on Herodotus, the pre-Saite history of Egypt, and his Egyptian sources.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Les Echecs amoureux ("Amorous Chess") Manuscript made for Louise of Savoy, 15th c. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département des Manuscrits; Mss.fr.143, fo 20.

Detail of the plastered and painted cartonnage mummy case of Tayesmutengebtiu (abbreviated to Tamut), a daughter of Khonsumose who was a high-ranking priest of Amun-Re. She lived at Thebes in the early part of the 22nd Dynasty, perhaps about 900 BCE. Tamut being bathed in life-giving waters, poured over her by the gods Horus (left) and Thoth (right). The liquid consists of a stream of hieroglyphic signs for 'life' and 'dominion'.

“Before the pharaoh in ancient Egypt could participate in any religious ceremony his body had to be purified by a sprinkling with water and natron. The water, called "water of life and good fortune," was brought from the sacred pool that belonged to every Egyptian temple.”

CONCEPTIONS OF PURITY IN EGYPTIAN RELIGION

By Joachim Friedrich Quack

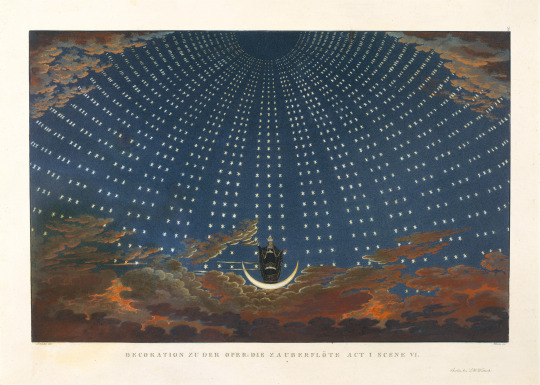

Design for The Magic Flute: The Hall of Stars in the Palace of the Queen of the Night, Act 1, Scene 6, Karl Friedrich Schinkel

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Basics of Kemetic Philosophy (without the appropriated shit from Judaism)

I'm starting a series on Kemetic philosophy because a lot of my readings on it have included things like Kabbalah (Kabala, Kabbala, Qabala, etc.) which is directly appropriated from Judaism, and definitely would not have been included in ancient Kemetic philosophy.

This series relies heavily on the following books/independent publications (this continues to be updated as the series continues):

The Instruction of Ptah-Hotep and the Instruction of Ka'Gemni: The Oldest Books in the World translated by John Murray

Teachings of Ptahhotep

Maat: The 11 Laws of God by Ra Un Nefer Amen (somewhat, this book literally has the Kabbalistic tree of life on its' cover so I don't take a lot from it--it's really just a good jumping-off point because it covers so much)

Maat: The Moral Idea in Ancient Egypt by Maulana Karenga

The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry edited with an introduction by William Kelly Simpson. Authors include Robert K. Ritner, Vincent A. Tobin, and Edward F. Wente.

I Am Because We Are: Readings in Africana Philosophy by Fred Lee Hord, Mzee Lasana Okpara, and Johnathan Scott Lee.

Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms by Miriam Lichtheim (2006 Edition)

Current Research in Egyptology 2009: Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Symposium by Judith Corbelli, Daniel Baotright, and Claire Malleson

Old Kingdom, New Perspectives: Egyptian Art and Archaeology 2750-2150 BC by Nigel Strudwick and Helen Strudwick

Current Research in Egyptology 2010: Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Symposium by Maarten Horn, Joost Kramer, Daniel Soliman, Nico Staring, Carina van den Hoven, and Lara Weiss

Current Research in Egyptology 2016: Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Symposium by Julia M. Chyla, Joanna Dêbowska-Ludwin, Karolina Rosińska-Balik, and Carl Walsh

Mathematics in Ancient Egypt: A Contextual History by Annette Imhausen

The Instruction of Amenemope: A Critical Edition and Commentary by James Roger Black

"The ancient Egyptian concept of Maat: Reflections on social justice and natural order" by R. James Ferguson

The Mind of Ancient Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs by Jan Assmann

Transformations of the Inner Self in Ancient Religions by Jan Assmann and Guy G. Stroumsa

Of God and Gods: Egypt, Israel, and the Rise of Monotheism by Jan Assmann

Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt by Jan Assmann

Cultural Memory and Early Civilization: Writing, Remembrance, and Political Imagination by Jan Assmann

From Akhenaten to Moses: Ancient Egypt and Religious Change by Jan Assmann

Book of the Dead: Becoming God in Ancient Egypt edited by Foy Scalf with new object photography by Kevin Bryce Lowry

It also relies on the following journal articles/book chapters:

"A Modern Look at Ancient Wisdom: The Instruction of Ptahhotep Revisited" by Carole R. Fontaine in The Biblical Archaeologist Volume 44, No. 3

"The Teaching of Ptahhotep: The London Versions" by Alice Heyne in Current Research in Egyptology 2006: Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Symposium

"One Among Many: A Divine Call for Gender Equity" by Sandra Y Lewis in Phylon (1960-) Volume 55, No. 1 & 2.

"A Tale of Semantics and Suppressions: Reinterpreting Papyrus Mayer A and the So-called War of the High Priest during the Reign of Ramesses XI" by Kim Ridealgh in Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur

EDITORIAL: African Philosophy as a radical critique" by Alena Rettová in Journal of African Cultural Studies Volume 28, No. 2

"Sanctuary Meret and the Royal Cult" by Miroslav Verner in Symposium zur Königsideologie / 7th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology: Royal versus Divine Authority: Acquisition, Legitimization and Renewal of Power. Prague, June 26–28, 2013

"The Ogdoad and Divine Kingship in Dendara" by Filip Coppens and Jiří Janák in Symposium zur Königsideologie / 7th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology: Royal versus Divine Authority: Acquisition, Legitimization and Renewal of Power. Prague, June 26–28, 2013

"The Egyptian Temple as a Place to House Collections (from the Old Kingdom to the Late Period) by Roberto A. Diaz Hernández in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 103, No. 1

"Death and the Sun Temple: New Evidence for Private Mortuary Cults at Amarna" by Jacquelyn Williamson in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 103, No. 1

"Mery-Maat, An Eighteenth Dynasty iry '3 pr pth From Memphis and His Hypothetical Family" by Rasha Metawi in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 101, 2015

"A New Demotic Translation of (Excerpts of) A Chapter of The "Book of the Dead" by Joachim Friedrich Quack in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 100, 2014

"The Shedshed of Wepwawet: An Artistic and Behavioural Interpretation" by Linda Evans in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 97, 2011

"(De)queering Hatshepsut: Binary Bind in Archaeology of Egypt and Kingship Beyond the Corporeal" by Uroš Matić in Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory Volume 23, No. 3 "Binary Binds": Deconstructing and Gender Dichotomies in Archeological Practice.

"Egyptian Maat and Hesiodic Metis" by Christopher A. Faraone and Emily Teeter in Mnemosyne Volume 57 Fasc. 2

"Maat and Order in African Cosmology: A Conceptual Tool for Understanding Indigenous Knowledge" by Denise Martin in Journal of Black Studies Volume 38, No. 6

"Memphis and Thebes: Disaster and Renewal in Ancient Egyptian Consciousness" by Ogden Goelet in The Classical World Volume 97, No. 1

"A Radical Reconstruction of Resistance Strategies: Black Girls and Black Women Reclaiming Our Power Using Transdisciplinary Applied Social Justice, Ma'at, and Rites of Passage" by Menah Pratt-Clarke in Journal of African American Studies Volume 17, No. 1

"Emblems for the Afterlife" by Marley Brown in Archaeology Volume 71, No. 3

"Human and Divine: The King's Two Bodies and The Royal Paradigm in Fifth Dynasty Egypt" by Massimiliano Nuzzolo in Symposium zur ägyptischen Königsideologie/8th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology: Constructing Authority. Prestige, Reputation and the Perception of Power in Egyptian Kingship. Budapest, May 12-14, 2016

"The Block and Its Decoration" by Josef Wegner in The Sun-shade Chapel of Meritaten from the House-of-Waenre of Akhenaten

"The African Rites of Passage and the Black Fraternity" by Ali D. Chambers in Journal of Black Studies Volume 47, No. 4

"Review: Translating Ma'at" by Stephen Quirke in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 80, 1994

"Additions to the Egyptian Book of the Dead" by T. George Allen in Journal of Near Eastern Studies Volume 11, No. 3

"Types of Rubrics in the Egyptian Book of the Dead" by T. George Allen in Journal of the American Oriental Society Volume 56, No. 2

"Book of the Dead, Book of the Living: BD Spells as Temple Texts" by Alexandra Von Lieven in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 98, 2012

"Fragments of the "Book of the Dead" on Linen and Papyrus" by Ricardo A. Caminos in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Volume 56, 1970

"Herodotus and the Egyptian Idea of Immortality" by Louis V. Z̆abkar in Journal of Near Eastern Studies Volume 22, No. 1

"Theban and Memphite Book of the Dead Traditions in the Late Period" by Malcolm Mosher Jr. in Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt Volume 29, 1992

"The Conception of the Soul and the Belief in Resurrection Among the Egyptians" by Paul Carus in The Monist Volume 14, No. 3

"It's About Time: Ancient Egyptian Cosmology" by Joanne Conman in Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur Volume 31, 2003

"Egyptian Parallels for an Incident in Hesiod's Theogony and an Episode in the Kumarbi Myth" by Edmund S. Meltzer in Journal of Near Eastern Studies Volume 33, No. 1

"The Book of the Dead" by Geo. St. Clair in The Journal of Theological Studies Volume 6, No. 21

"The Egyptian "Book of the Two Ways"" by Wilhelm Bonacker in Imago Mundi Volume 7, 1950

"The Papyrus of Nes-min: An Egyptian Book of the Dead" by William H. Peck in Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts Volume 74, No. 1/2

#kemeticism#kemetic#kemetism#kemet#history#ra#anubis#hathor#egypt#ancient egypt#gods of egypt#egyptian#egyption#judaism#culturalappropriation#culture#linguistics#language#cosmology#astrology#astronomy#philosophy#philosophical#basics of kemetic philosophy#resources#basics

327 notes

·

View notes

Text

Egyptology professor J. Fr. Quack on Herodotus’ Egyptian sources and “precise knowledge” of the Egyptian realities and traditions (text in French with translation to English)

“ Remarques finales

En somme, les études actuelles montrent bien qu’apparaissent de plus en plus de parallèles entre les récits d’Hérodote et la documentation démotique égyptienne, aussi bien pour les traditions concernant l’histoire de l’Egypte que pour la section “ethnographique”. La question spécifique des sources devrait devenir plus claire grâce à cet apport. Hérodote se réfère souvent à ce qu’il a entendu des prêtres égyptiens 96. Les textes démotiques que j’ai présentés ici proviennent largement d’un milieu de prêtres, comme le montrent assez clairement les papyrus de Tebtynis. Cela montre aussi à l’évidence que les traditions sur le passé égyptien et les hauts faits des héros, que l’on a souvent qualifiés de “ folkloriques” 97, ont une base solide dans les récits qui circulaient parmi les prêtres de l’Egypte tardive. Et là où le récit d’Hérodote nous semble étrange, s’agissant des anecdotes sur les rois égyptiens ou leur ordre de succession, il serait approprié d’imputer cette étrangeté moins aux erreurs et mécompréhensions de l’historien grec ou aux fantaisies de guides incultes qu’ aux confusions qui se sont déjà produites pendant la longue transmission de la culture égyptienne. Qu’Hérodote soit quand même aussi capable de modifier certains détails pour mieux les faire s’accorder à ses propres manières de pensée est indiscutable, mais ne peut aucunement changer l’image globale: Hérodote montre une connaissance si précise des traditions et réalités égyptiennes qu’il est difficile de ne pas admettre la réalité de la visite en Egypte du “père de l’histoire”. L’ “école des menteurs 98”, qui nie cette visite, se trouve donc formellement démentie. Ainsi la tradition de recherche qui voit dans les rapports d’Hérodote avec les peuples étrangers surtout un mirroir mettant en relief leur altérité vis-à-vis les Grecs, sans assez prendre en compte les réalités 99, s’avère inadéquate pour traiter la complexité de l’oeuvre de l’historien d’Halicarnasse.”

[ Final Remarks

In summary, the current studies show well that more and more parallels appear between Herodotus’ narrative and the Egyptian demotic documentation, for both the traditions on the history of Egypt and the “ethnographic” section. The specific question about the sources should become clearer thanks to this contribution. Herodotus often refers to what he has heard from Egyptian priests 96. The demotic texts that I have presented here originate largely from a priestly milieu, as it is showed clearly enough in the papyri of Tebtynis. This makes also abundantly clear that the traditions on the Egyptian past and the exploits of the heroes, which have often been characterized as “folkloric” 97, have a solid basis in the stories circulating among the priests of Late Egypt. And where Herodotus’ narrative seems to us strange, concerning the anecdotes on the Egyptian kings or their order of succession, it would be appropriate to impute this strangeness less to the errors and misunderstandings of the Greek historian or to the fancies of uncultured guides than to the confusions which had been already produced during the long transmission of the Egyptian culture. Although it is undeniable that Herodotus is capable of modifying certain details in order to make them agree with his own way of thinking, this can by no means change the overall picture: Herodotus shows such a precise knowledge of the Egyptian traditions and realities that it is difficult to not admit the reality of the visit to Egypt of the “father of history”. The “Liar school” 98 which denies this visit is explicitly refuted. Also the tradition of research which sees above all in the relations of Herodotus with foreign peoples a miror effect putting into relief their otherness in comparison to the Greeks, without taking enough into account the realities 99, is proved to be inadequate to deal with the complexity of the work of the historian from Halicarnassus.]

J-Fr. Quack “Quelques apports récents des études démotiques à la compréhension du Livre II d’ Hérodote” (”Some recent contributions of the demotic studies to the understanding of Book II of Herodotus”) in L.Coulon- P. Giovannelli-Jouanna- F. Kimmel-Clauzet (editors) Hérodote et l'Égypte. Regards croisés sur le Livre II de l'Enquête d'Hérodote, Actes de la journée d’étude organisée à la Maison de l’Orient et de la Méditerranée – Lyon, le 10 mai 2010. Lyon : Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, 2013, available on https://www.persee.fr/doc/mom_0151-7015_2013_act_51_1_2256

Joachim Friedrich Quack is German Egyptologist and Demotic language specialist, professor of Egyptology at the University of Heidelberg. Among his works, we should mention his edition (with Kim Ryholt) of the papyri of Tebtynis and of other texts of demotic literature.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some remarks on a text about Herodotus and his Egyptian sources circulating on this site

An internet friend of mine sent me privately the following text, which circulates in some egyptological quarters of tumblr as proof of the “unreliability” of Herodotus’ sources in Egypt and, therefore, of Herodotus himself as historian, and asked me for some comments on it. So, first of all let us enjoy this piece of excellent wisdom:

“I can't believe I'm going to do this. Who wants a presentation on Herodotus' sources for Book 2 (the Egypt book)? It was given by PhD student Alex Tarbet for the Herodotus Helpline and it's 46 minutes long. Folks, this is a scholar who is explicitly arguing that Herodotus' Egyptian sources can not be trusted for factual information on the lives of the Pharaohs. The specific topic is how the stories of the Pharaohs appear to be humorous "Tourist Trap" stories rather than factual narratives from reputable, educated sources. And that the "priests" Herodotus talked to might not have been real priests. While Tarbet is clearly fond of Herodotus, he is also critical of the source material (he also straight up calls Herodotus a tourist). This is an attitude that more people need to have.

“It’s very possible that if Herodotus asked to talk to a priest he could have gotten somebody with a little bit of attitude, a little bit of salt, drawing on these popular traditions. It’s like if someone wandered around Italy asking to talk to the Pope and the locals instead said things like, ‘I’m the Pope,’ or they drew upon all these jokes about the Pope’s hat that they knew, and in some ways it was a way of brushing off a tourist. This is the sort of thing that happens at a festival along the Nile, you get all sorts of interactions between people, and Herodotus had a kindof difficult time figuring out when people were just joking with him or they were telling him true facts.”

In other words, sure, you can learn stuff from The Histories, but only if you remember and accept that it's not all true, and that you can't just trust it and accept it at face value, especially the Egypt part. You know...the thing the Egyptologists have been trying to hammer into people's heads for a couple of years now.

(My stance on Herodotus remains unchanged, and now has another scholar to back it up.)”

I remind that I have posted some days ago Alex Tarbet’s video from the youtube channel of Herodotus Helpline with some first observations on it ( https://aboutanancientenquiry.tumblr.com/post/701207851115462656/in-this-talk-from-the-2022-23-edition-of-the).

And now my remarks on the text that has been sent to me and I have reproduced above:

1/ There is no comparison between Tarbet’s views on Herodotus and those of the group of tumblr egyptologists on the same topic, contrary to what the author of the text rather disingenuously claims. Tarbet’s approach has its merits and flaws (more about this later), but his main point is that Herodotus preserves genuine Egyptian popular traditions and, therefore, Herodotus’ Book II (on Egypt) is for him of great value. On the contrary, the tumblr egyptologists claim that Herodotus’ work about Egypt is totally wrong and worthless, an aggregate of lies and fabrications, and the main sourse of misconceptions about ancient Egypt (I omit here any further reference to the other antics of the same group of people).

Moreover, contrary to what the author of the same text claims, Tarbet does not say anything about the existence or not of Egyptian “reputable, educated sources’ that Herodotus should have contacted but he didn’t. In other words, Tarbet says nothing about the histrorical consciousness of the Egyptian intellectual elites of the time of Herodotus’ visit to Egypt and on whether these elites had or not solid historical knowledge of the past of Egypt that they could convey to Herodotus. But more about this later.

2/ Now, to clarify things, most of the stories to which Tarbet refers belong to the part of Book II of Herodotus’ Histories (2.99 to 2.151) having as subject the pre-Saite period of Egypt (before 664 BCE). And of course this is the most problematic part of Book II, because, if each period of the Egyptian history is represented in it (with the exception of the Hyksos) and what the Pharaohs do according to it corresponds to the traditional functions of the Egyptian kingship (see A.B. Lloyd in “A Commentary on Herodotus Books I-IV” of Asheri-Lloyd-Corcella, p. 238), it contains also many tales but also some important factual errors. On the contrary, Herodotus’ account of the Saite period (2.152 to 2.182) is much more solid and a main source for that period, and of course the geographical part of the same Book (2.4 to 2.34) is very interesting as proto-scientific approach and its ethnographical part (2.35 to 2.98) contains much accurate and useful information. So, no one claims that we should take at face value the story of Pheros or of Rhampsinitos, as the author of the text sent to me foolishly insinuates.

But what is more important is that Herodotus himself is aware of the problematic character of what his Egyptian sources (the priests) told him about the pre-Saite Egypt. Thus, he warns us that (translation A. D. Godley):

(2.99,1, 2): So far, all I have said is the record of my own autopsy and judgment and inquiry. Henceforth I will record Egyptian chronicles, according to what I have heard, adding something of what I myself have seen. The priests told me..,

And he continues with the story of Min, the first Pharaoh. And again:

(2.123,1): These Egyptian stories are for the use of whosoever believes such tales: for myself, it is my rule throughout this history that I record whatever is told me as I have heard it.

And again, explaining that with the reign of Psammetichos I (the founder of the Saite dynasty) and the settlement of Greeks and Carians to Egypt there are not only Egyptian, but also foreign sources on the Egyptian history and there was thus for the Greeks the opportunity of a much better knowledge of the history of Egypt under the Saite rulers:

(2.147,1): Thus far I have recorded what the Egyptians themselves say. I will now relate what is recorded alike by Egyptians and foreigners to have happened in that land, and I will add thereto something of what I myself have seen.

(2.154): The Ionians and Carians who had helped him to conquer were given by Psammetichus places to dwell in called The Camps, opposite to each other on either side of the Nile; and besides this he paid them all that he had promised. Moreover he put Egyptian boys in their hands to be taught the Greek tongue; these, learning Greek, were the ancestors of the Egyptian interpreters. The Ionians and Carians dwelt a long time in these places, which are near the sea, on the arm of the Nile called the Pelusian, a little way below the town of Bubastis. Long afterwards, king Amasis removed them thence and settled them at Memphis, to be his guard against the Egyptians. It comes of our intercourse with these settlers in Egypt (who were the first men of alien speech to settle in that country) that we Greeks have exact knowledge of the history of Egypt from the reign of Psammetichus onwards. There still remained till my time, in the places whence the Ionians and Carians were removed, the landing engines of their ships and the ruins of their houses.

So, Herodotus, far from being some kind of naive fool, has some very clear and innovative ideas about the methods and tools of collection and evaluation of information. Moreover, he is fully aware of the fact (and warns about it his readers) that what his Egyptian informants told him about the pre-Saite period should not be taken at face value as representation of the historical reality. Herodotus records, however, these stories because this was the material that he managed to collect about the pre-Saite Egyptian history and because he judged that this material deserved to be preserved, as it came from the Egyptians themselves.

3 / Now, again about Alex Tarbet and Herodotus, as I said above I find that Tarbet’s approach on Herodotus and Egypt has merits but also flaws. Tarbet (a PhD candidate in Classics at the University of Michigan) presents his project like this (https://lsa.umich.edu/humanities/people/2022-23-fellows/alex-tarbet.html ):

Ancient Egyptians had rich and complex humor traditions long before Greeks set foot in Africa. In the 5th century BCE, a few of their jokes, anecdotes, tales, and histories were picked up by the Greek tourist Herodotus as he traveled down the Nile. Herodotus met and listened to local storytellers in relaxed settings, and so preserved a bundle of playful and humorous African oral folk performances for his Greek democratic audience. My project imagines that transmission: a local world of brilliant Egyptian folk storytellers engaging with an audience of foreign travelers, tourists, and inquirers, through whom some of their lore passed around the Mediterranean. Humorous and even obscene critiques of authoritarians or tyrants tend to travel easily across languages, identities, and ethnicities, as expressions of popular resistance from below. Drawing on modern Arab and North African folk traditions by analogy, I explore the way ancient Egyptian popular commentaries on matters like power, gender, and colonialism passed obliquely into Greek democratic prose.

What I find valuable in Tarbet’s approach is his effort to show the influence of the Egyptian popular tradition on Herodotus, but also the existence and importance of an Egyptian folk humoristic tradition, often at the expense of rulers. And of course in some cases (for example the tale of Rhampsinitos and the clever thief) this approach seems totally valid.

On the other hand, what I find objectable in his approach is first of all his rather schematic and simplistic considerations in his video on the Greek philosophers and their views. More particularly concerning Herodotus, Tarbet approaches Herodotus’ interactions with the Egyptians exclusively from the angle of the Egyptian humoristic folk tradition and of jokes (or even pranks) performed by the Egyptians for or at the expense of foreigners. But I think that it should be obvious that most things Herodotus heard in Egypt were not just expression of humor and that most tales circulating in Egypt in Herodotus’ time were not perceived just as humoristic fiction by those who told and heard them. I think also that it is obvious that having fun could not have been the only motivation in the Egyptian attitudes toward foreigners and that the desire to impress the latter, but also curiosity and in some cases willingness for some genuine and serious interaction with them must have played at least some role in these attitudes. With Tarbet we have often the image of joyful Egyptians constantly joking, something which rather contrasts with what we know about the period of Herodotus’ visit to Egypt (which very probably must have taken place somewhere in the late 440′s BCE), a period of oppressive foreign (Persian) rule. And in some places his approach veers toward clichés of the type “the clever Egyptians made fun at the expense of stupid Greek tourists”.

Moreover, some of the tales Tarbet invokes are not so humoristic: thus, the story of Pheros has an important aspect of misogyny in it (the theme that most women are unfaithful), but also an aspect of horror (the Pharaoh has in the end the unfaithful women burnt alive, something very probably seen as a just punishment by Herodotus’ Egyptian source which told him this version of the story). And, to my knowledge, Tarbet is the only scholar who sees the story of the linguistic experiment of Psammetichos as humoristic or expressing a criticism toward this Pharaoh.

Of course I disagree with Tarbet’s statement in his video and texts that Herodotus was a “tourist”. Tarbet presents Herodotus as a “tourist” because this is convenient for his thesis about the influence of an Egyptian folk humor tradition on more or less naive Greek “tourists” (a characterization which, moreover, is rather anachronistic). However, if it is true that Herodotus went to Egypt for a brief period of time (perhaps half a year), his purpose was undoubtedly scholarly, not that of a tourist. And we should not forget that, despite all the evident flaws of the Book II on Egypt from a modern perspective, as the preeminent Egyptologist Barry Kerry puts it:

“In the history of the objective study of the human society he [ my- aboutanancientenquiry’s-note : Herodotus] represents a milestone (there is absolutely nothing like his narrative from ancient Egypt before his day)…Herodotus “History” contains by far the earliest eyewitness account of life in ancient Egypt written by an outsider for the benefit of his own people and should be treasured for that“ (Barry Kemp Egypt-Anatomy of a Civilization).

4/ Did Herodotus talk to “real” Egyptian priests, as he claims?

Tarbet disbelieves that Herodotus talked to real Egyptian priests, in the sense of the permanent staff of the temples and of the religious and intellectual elite of Egypt. As he explains (https://antigonejournal.com/2021/10/egyptian-cats-greek-curiosity/ ):

Temples had thousands of personnel, from groundskeepers to cooks to guards to the high priest himself. Many of these had seasonal priesthoods only for three or four months of the year with temporary prestige and pay. Perhaps Herodotus had a brief encounter with a farmer, merchant, craftsman, local guide, tourist-trapper, traveling bard, streetside raconteur – any of them a ‘priest’ only part of the year.

When someone, say, a metalworker or fishmonger, worked in a temple for a few months as a priest, creative lore from his daily home life could easily trickle in with him. Fresh stuff sourced from the family household: children’s tales, fables, rumors, jokes, myths, news, gossip, insults, spells, problems with the neighbor’s cats – you name it. And then it trickled out. Herodotus could have heard anything anywhere.

But, although I like his description of the life in an Egyptian temple, I don’t think that Tarbet’s reasoning is solid here. Herodotus was not a naive and foolish “tourist’, but a man with intelligence and vast experience of the world. And I think that even an average person with some experience of life could tell the difference between on the one hand a real priest with permanent office and on the other hand manual workers who were temporary ‘priests”, in the sense of the auxiliary personel of the temples. I say this because I think that the quality of a person as elite or subordinate in the Antiquity could be perceived rather easily through their clothes, adornment, and body language, but also because the manual workers-temporary priests of the Egyptian temples obviously performed their tasks as manual workers, something that Herodotus or any other visitor would have perceived immediately. Moreover, I don’t think that Herodotus would have arrived at least at Memphis and Heliopolis without recommendations from Greeks active in Egypt and having some acquaintances in the Egyptian priesthood, something which corroborates the view that he knew the kind of persons he went to meet and that such persons (priests in the full sense of the term) had reasons to receive him well and talk to him.

What I say is confirmed by the fact that most Demotic Egyptian texts having similarities with what Herodotus records about the pre-Saite Egypt have been found in the library of the temple of Tebtynis. I am not talking only about the story of Pheros that Tarbet invokes in his video, but also about this of Sesostris and others. So, it seems that these stories were not just some kind of pop Egyptian culture circulating among the temporary manual workers- “priests” of the temples and more generally among the Egyptian population, but they were the possession and were read by the Egyptian priests in their temple libraries, and perhaps priests played an important role in their formation. This confirms of course Herodotus’ claim that he talked to Egyptian priests in the ordinary sense of the term and that these priests were the sources for his account of the pre-Saite history of Egypt.

German Egyptology professor Joachim Friedrich Quack, the scholar who edited the texts from Tebtynis some years ago and stressed their similarities with Herodotus’ record in Book II, has no doubts that the discovery and study of the papyri from the library of the temple of Tebtynis confirms Herodotus when he says that he heard what he writes about the history of Egypt from Egyptian priests (J-Fr. Quack “Quelques apports récents des études démotiques à la compréhension du Livre II d’Hérodote” -”Some recent contributions of the demotic studies to the understanding of Book II of Herodotus”, in Hérodote et l'Égypte. Regards croisés sur le Livre II de l'Enquête d'Hérodote. Actes de la journée d'étude organisée à la Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée – Lyon, le 10 mai 2010, available on https://href.li/?https://www.persee.fr/doc/mom_0151-7015_2013_act_51_1_2256 , in my translation into English):

In summary, the current studies show well that more and more parallels appear between Herodotus’ narrative and the Egyptian demotic documentation, for both the traditions on the history of Egypt and the “ethnographic” section. The specific question about the sources should become clearer thanks to this contribution. Herodotus often refers to what he has heard from Egyptian priests 96. The demotic texts that I have presented here originate largely from a priestly milieu, as it is showed clearly enough in the papyri of Tebtynis. This makes also abundantly clear that the traditions on the Egyptian past and the exploits of the heroes, which have often been characterized as “folkloric” 97, have a solid basis in the stories circulating among the priests of Late Egypt. And where Herodotus’ narrative seems to us strange, concerning the anecdotes on the Egyptian kings or their order of succession, it would be appropriate to impute this strangeness less to the errors and misunderstandings of the Greek historian or to the fancies of uncultured guides than to the confusions which had been already produced during the long transmission of the Egyptian culture.

And we come now to the problem of the historical consciousness and historical knowledge of the priestly milieus with which Herodotus had contacts. We know that these priests had at their disposal rather accurate king lists (thus Herodotus 2.100), but on the other hand we know that the transmission of the knowledge of the past in ancient Egypt was far from flawless and that many legends and tales about this past circulated among the Egyptian priests who, at least to some degree, believed in them (this is proved not only by the library of Tebtynis, but also by the surviving fragments of the 3d century BCE priest-historian Manetho, the first Egyptian who wrote a continuous history of Egypt, following but also criticizing Herodotus). We know also that the ancient Egyptian priests and scribes were totally capable of manipulating history in order to serve their agendas. To what degree the problematic character of much of what the Egyptian priests related to Herodotus about the pre-Saite history of Egypt was just the result of their confusions and of distortions in their historical consciousness resulting from flawed transmission of the knowledge of the past and from the influence of legend, and to what degree they served agendas by consciously manipulating history in their interactions with a foreigner like Herodotus is a different and very interesting question that I will try to approach in a future post.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

An important multidisciplinary collective work about Herodotus’ logos on the Persian King Cambyses in Egypt

Andreas Schwab, Alexander Schütze

Herodotean Soundings

The Cambyses Logos

This volume is dedicated to the logos of Cambyses at the beginning of Book 3 in Herodotus' Histories, one of the few sources on the Persian conquest of Egypt that has not yet been exhaustively explored in its complexity. The contributions of this volume deal with the motivations and narrative strategies behind Herodotus' characterization of the Persian king but also with the geopolitical background of Cambyses' conquest of Egypt as well as the reception of the Cambyses logos by later ancient authors. “Herodotean Soundings: The Cambyses Logos” exemplifies how a multidisciplinary approach can contribute significantly to a better understanding of a complex work such as Herodotus' Histories.

Contents

Alexander Schütze & Andreas Schwab: Introduction

I CLOSE READINGS: LINGUISTIC, NARRATOLOGICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL PERSPECTIVES

Elizabeth Irwin: Just Who is Cambyses? Imperial Identities and Egyptian Campaigns

Anna Bonifazi: Herodotus’ verbal strategies to depict Cambyses’ abnormality

Anthony Ellis: Relativism in Herodotus: Foreign Crimes and Divinities in the Inquiry

II SOUNDINGS: GEOPOLITICAL, HISTORICAL AND EGYPTOLOGICAL ASPECTS

Melanie Wasmuth: Perception and Reception of Cambyses as Conqueror and King of Egypt: Some Fundamentals

Alexander Schütze: Remembering Cambyses in Persian Period Egypt

Gunnar Sperveslage: On the historical and archaeological background of Cambyses’ alliance with Arab tribes (Hdt. 3.4-9)

Damien Agut-Labordère: An “Ammonian Tale”: Cambyses in the Egyptian Western Desert

Olaf Kaper: The revolt of Petubastis IV during the reigns of Cambyses and Darius

Andreas Schwab: “Psammis”: just a sandstorm or a rebel?

Joachim-Friedrich Quack: Cambyses and the sanctuary of Ptah

Fabian Wespi: Cambyses’ Decree

III RECEPTION

Reinhold Bichler: A comparative look at the Post-Herodotean Cambyses

Andreas Schwab is Assistant Professor of Classics at the Ruprecht-Karls-University of Heidelberg in Germany

Alexander Schütze is currently Assistant Professor at the Institute for Egyptology and Coptology at Ludwig Maximilian University Munich.

Source: https://www.narr.de/herodotean-soundings-18329-1/

This important and interdisciplinary collective work on Herodotus, the Persian conquest of Egypt, and the rule and end of Cambyses will appear on April 24 of this year.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herodotus as source for conceptions of purity in Late Period Egypt

“A further important question concems behavior towards foreigners. At least for the Late Period, there is evidence for a demarcation via purity conceptions. However, there are relatively few sources for this phenomenon in the Egyptian language. Although there are a few texts forbidding access to the temple for certain persons,77 it must be noted that these mostly concem not the whole temple complex but only certain areas, such as the crypts, to which only a few Egyptian priests had access. In addition, the original ethnic names ’im and s?s became, in the vernacular of the Late Period, professional names for herdsmen of cattle and sheep. In any case, there is concrete evidence that foreigners could become priests in an Egyptian temple.78

Furthermore, the biblical story of Joseph stresses that the Egyptians would not eat ffom the same table as the Hebrews (Gen 43:32)79 Other than this, the main external source is certainly Herodotus. He indicates that the Egyptians were very much concerned with purity, even cleaning the bronze beaker on a daily basis, wearing freshly washed linen garments, practicing circumcision for purity, and requiring that the priest shave his whole body daily and wear only a linen garment and sandals made of papyrus, in addition to washing twice a day and twice a night with cold water. They were not allowed to eat fish and beans (2.37). In addition, we also leam that they did not slaughter cows but only male cattle, and for this reason did not kiss any Greeks and would not use any Greek kitchenware (2.41). Another point in Herodotus indicative of differences in purity concepts between the two ethnicities is the treatment of the head of the sacrificial animal. At an Egyptian offering, many maledictions would be spoken over it and afterward, if there were any Greek traders nearby, it would be sold to them; otherwise it would be thrown into the river. All in all, the classification of Egyptians in contrast to other peoples where purity rules are concemed is not very explicit.”

From Joachim Friedrich Quack, “Conceptions of Purity in Egyptian Religion”, in : Christian Frevel, Christophe Nihan (ed.), Purity and the forming of religious traditions in the ancient Mediterranean world and ancient judaism (Dynamics in the history of religion 3), Leiden ; Boston 2013, p.115-158

On line source: https://d-nb.info/1232919330/34

Joachim Friedrich Quack is German Egyptologist, professor of Egyptology at the University of Heidelberg.

#herodotus#ancient greek classics#egyptology#ancient egypt#ancient egyptian religion#joachim friedrich quack

1 note

·

View note