#lebrecht

Photo

The National Theatre has just announced it will ‘reduce activity’ over the next four years due to ‘financial challenges’. English National Opera is on its final year of funding. The BBC Singers have been abolished. Britten Sinfonia has launched a £1 million appeal to enable it to survive Arts Council cuts. A quarter of the seats in BBC orchestras are to be unwaged. Cities the size of Liverpool, Norwich and Southampton have been left without opera. The post-1945 English artistic renaissance has gone into abrupt reverse, without much political debate.

Darkness descends.

Discuss.

- Norman Lebrecht

The axe of cultural vandalism is in full swing against anything classical. The BBC is the biggest employer of musicians in the UK, and to lose one in five of their orchestral players will create a black hole for musicians already stymied by visa restrictions and thus wider opportunities traditionally afforded them. The end of the BBC Singers, in particular, is heartbreaking - founded nearly 100 years ago, they have given both comfort and joy to the nation.

Photo: The BBC Singers.

#lebrecht#norman lebrecht#quote#arts#BBC#culture#britain#cuts in funding#funding of the arts#BBC singers#national theatre#britten sinfonia#arts council#BBC orchestras#decline and fall

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Maid, Wilhelm August Lebrecht Amberg, 1862

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Wilhelm August Lebrecht

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The celebrated french music composer and pianist Claude Debussy (1862 - 1918), French, ca. 1905 - Lebrecht Music Arts

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

the ever-incredible natalie rose lebrecht

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A new variant has been added!

Lappet-faced Vulture (Torgos tracheliotos)

© Jean Lebrecht Reinold

It hatches from aggressive, bluish, broad, brown, bulky, bullish, diagnostic, loose, massive, naked, open, other, puffy, rare, small, white, widespread, wrinkled, and yellow eggs.

squawkoverflow - the ultimate bird collecting game

🥚 hatch ❤️ collect 🤝 connect

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Norman Lebrecht: Straussov novogodišnji koncert i nacizam

Bečki novogodišnji koncert je možda jedno od poslednjih opuštenih okupljanja svetske televizije. Prvog jutra nove godine, u 11 sati i 15 minuta po centralnoevropskom vremenu, na mestu koje sebe smatra epicentrom Evrope, grupa muškaraca u svečanim odelima penje se na pozornicu Dvorane Bečkog muzičkog društva (Musikverensaal) da bi izvela ritual koji slovi za simbol kulture i tradicije. A koji,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Prana by Natalie Rose LeBrecht

0 notes

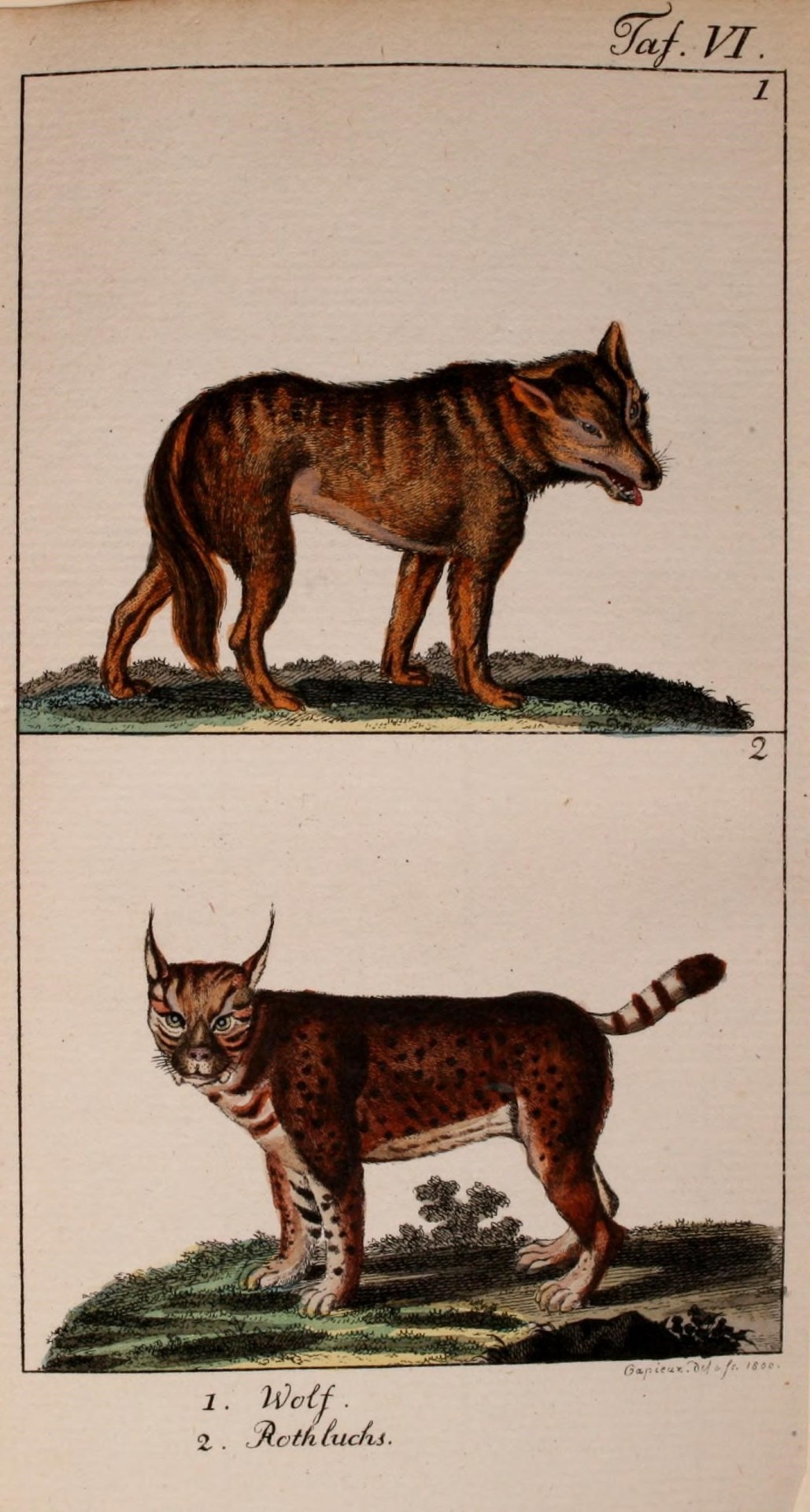

Photo

🐼 Gemeinnützige Naturgeschichte Deutschlands nach allen drey Reichen Leipzig: Bey Siegfried Lebrecht Crusius, 1801-1809.

35 notes

·

View notes

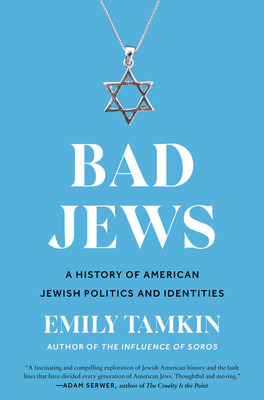

Photo

Nonfiction Recommendations: Jewish American Heritage Month

Black, White and Jewish by Rebecca Walker

The Civil Rights movement brought author Alice Walker and lawyer Mel Leventhal together, and in 1969 their daughter, Rebecca, was born. Some saw this unusual copper-colored girl as an outrage or an oddity; others viewed her as a symbol of harmony, a triumph of love over hate. But after her parents divorced, leaving her a lonely only child ferrying between two worlds that only seemed to grow further apart, Rebecca was no longer sure what she represented. In this book, Rebecca Leventhal Walker attempts to define herself as a soul instead of a symbol—and offers a new look at the challenge of personal identity, in a story at once strikingly unique and truly universal.

Bad Jews by Emily Tamkin

What does it mean to be a Bad Jew? Many Jews use the term “Bad Jew” as a weapon against other members of the community or even against themselves. You can be called a Bad Jew if you don’t keep kosher; if you only go to temple on Yom Kippur; if you don’t attend or send your children to Hebrew school; if you enjoy Christmas music; if your partner isn’t Jewish; if you don’t call your mother often enough. The list is endless.

In Bad Jews, Emily Tamkin argues that perhaps there is no answer to this timeless question at all. Throughout American history, Jewish identities have evolved and transformed in a variety of ways. American Jewish history is full of discussions and debates and hand wringing over who is Jewish, how to be Jewish, and what it means to be Jewish. In this book, Emily Tamkin examines the last 100 years of American Jewish politics, culture, identities, and arguments. Drawing on over 150 interviews, she tracks the evolution of Jewishness throughout American history, and explores many of the evolving and conflicting Jewish positions on assimilation; race; Zionism and Israel; affluence and poverty, philanthropy, finance, politics; and social justice. From this complex and nuanced history, Tamkin pinpoints perhaps the one truth about American Jewish It is always changing.

Genius & Anxiety by Norman Lebrecht

In a hundred-year period, a handful of men and women changed the way we see the world. Many of them are well known—Marx, Freud, Proust, Einstein, Kafka. Others have vanished from collective memory despite their enduring importance in our daily lives. Without Karl Landsteiner, for instance, there would be no blood transfusions or major surgery. Without Paul Ehrlich, no chemotherapy. Without Siegfried Marcus, no motor car. Without Rosalind Franklin, genetic science would look very different. Without Fritz Haber, there would not be enough food to sustain life on earth.

What do these visionaries have in common? They all had Jewish origins. They all had a gift for thinking in wholly original, even earth-shattering ways. In 1847 the Jewish people made up less than 0.25% of the world’s population, and yet they saw what others could not. How? Why?

Norman Lebrecht has devoted half of his life to pondering and researching the mindset of the Jewish intellectuals, writers, scientists, and thinkers who turned the tides of history and shaped the world today as we know it. In Genius & Anxiety, Lebrecht begins with the Communist Manifesto in 1847 and ends in 1947, when Israel was founded. This robust, magnificent volume, beautifully designed, is an urgent and necessary celebration of Jewish genius and contribution.

People Love Dead Jews by Dara Horn

Renowned and beloved as a prizewinning novelist, Dara Horn has also been publishing penetrating essays since she was a teenager. Often asked by major publications to write on subjects related to Jewish culture—and increasingly in response to a recent wave of deadly antisemitic attacks—Horn was troubled to realize what all of these assignments had in common: she was being asked to write about dead Jews, never about living ones. In these essays, Horn reflects on subjects as far-flung as the international veneration of Anne Frank, the mythology that Jewish family names were changed at Ellis Island, the blockbuster traveling exhibition Auschwitz, the marketing of the Jewish history of Harbin, China, and the little-known life of the "righteous Gentile" Varian Fry. Throughout, she challenges us to confront the reasons why there might be so much fascination with Jewish deaths, and so little respect for Jewish lives unfolding in the present.

Horn draws upon her travels, her research, and also her own family life—trying to explain Shakespeare’s Shylock to a curious ten-year-old, her anger when swastikas are drawn on desks in her children’s school, the profound perspective offered by traditional religious practice and study—to assert the vitality, complexity, and depth of Jewish life against an antisemitism that, far from being disarmed by the mantra of "Never forget," is on the rise. As Horn explores the (not so) shocking attacks on the American Jewish community in recent years, she reveals the subtler dehumanization built into the public piety that surrounds the Jewish past—making the radical argument that the benign reverence we give to past horrors is itself a profound affront to human dignity.

#jewish american heritage month#jewish heritage#judaism#nonfiction#nonfiction books#Nonfiction Reading#history#Reading Recs#reading recommendations#Book Recommendations#book recs#TBR pile#tbr#tbrpile#to read#Want To Read#Booklr#book tumblr#book blog#library blog

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miles Davis and Wayne Shorter in Berlin Germany 1964,

Photo © JazzSign/Lebrecht Music & Arts/Corbis

https://www.facebook.com/TheWorldOfJazz

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Passover Is One of Judaism’s (of The Real Jews Not of The Zionist 🐷 🐖 🐗 🐖) Most Important Holidays

Passover, one of Judaism's most revered holidays, honors the ancient Israelites' freedom from slavery in Egypt.

— By Erin Blakemore | April 15, 2024

Rabbi Pinsk Karlin and other ultra-Orthodox Jews collect water from a spring to make matzoh, a traditional handmade unleavened bread for Passover, at a mountain spring in the outskirts of Jerusalem. Jews are forbidden to eat leavened foodstuffs during Passover. Photograph By Ariel Schalit, AP

As the days brighten and spring kicks into full swing, Jews all over the world prepare for Passover, a weeklong holiday that is one of Judaism’s most widely celebrated and most important observances. Also known by its Hebrew name Pesach, Passover combines millennia of religious traditions—and it’s about much more than matzoh and gefilte fish.

The Origins of Passover

The story of Passover can be found in the book of Exodus in the Hebrew Bible, which relates the enslavement of the Israelites and their subsequent escape from ancient Egypt.

Fearing that the Israelites will outnumber his people, the Egyptian Pharaoh enslaves them and orders every newly born Jewish son murdered. One son is Moses, whose birth has been foretold as the savior of the Israelites. He is saved and raised by the pharaoh’s daughter.

William Brassey Hole's "The Passage of the Red Sea" depicts the biblical story from Exodus in which God, acting through Moses, parts the Red Sea to allow the Israelites to cross to safety out of Egypt. Lebrecht History/Bridgeman Images

In adulthood, God speaks to Moses, urging him to tell Pharaoh to let his people go. But the pharaoh refuses. In return, God brings ten consecutive plagues down on Egypt (think: pestilence, swarms of locusts, and water turning to blood), but spares the Israelites.

During the final plague, an avenging angel goes door to door in Egypt, smiting every household’s firstborn son. God has other plans for the Israelites, instructing Moses to tell them to slaughter a lamb, then brush its blood on the sides and tops of their doorframes so that the avenging angel will “pass over.” Then they are to eat the sacrificial lamb with bitter herbs and unleavened—without yeast—bread. This is the last straw for Pharaoh, who frees the Israelites and banishes them from Egypt.

What’s on a Seder Plate

Modern Passover celebrations commemorate and even reenact many of the biblical events. The seder (“order”), the ritual meal that is the centerpiece of Passover celebrations, incorporates foods that represent elements of the story.

Bitter herbs (often lettuce and horseradish) stand for the bitterness of slavery. A roasted shank bone commemorates the sacrificial lamb. An egg has multiple interpretations: Some hold that it stands for new life, and others see it as standing for the Jewish people’s mourning over the struggles that awaited them in exile. Vegetables are dipped into saltwater representing the tears of the enslaved Israelites. Haroset, a sweet paste made of apples, wine, and walnuts or dried fruits, represents the mortar the enslaved Israelites used to build Egypt’s store cities.

The centerpiece of modern Passover celebrations is the seder, a ritual meal commemorating the Israelites' escape from enslavement in Egypt. The dinner involves readings from a manuscript called the Haggadah. The Sarajevo Haggadah, pictured here, is one of the oldest, dating back to the 14th century. Photograph By Zev Radovan, Bridgeman Images

During a traditional seder, participants eat unleavened bread, or matzoh, three times, and drink wine four times. They read from a Haggadah, a guide to the rite, hear the story of Passover, and answer four questions about the purpose of their meal. Children get involved, too, and search for an afikomen, a piece of broken matzoh, that has been hidden in the home. Every seder is different, and is governed by community and family traditions.

How is Passover Celebrated

Passover observances vary in and outside of Israel. The holiday lasts one week in Israel and eight days in the rest of the world, in commemoration of the week in which the Israelites were pursued by the Egyptians as they went into exile.

During those days, many Jews refrain from eating leavened bread; some also abstain from work during the last two days of Passover and attend special services before and during Passover week. Orthodox and Conservative Jews outside of Israel participate in two seders; Reform Jews and those inside Israel only celebrate one.

But no matter where or how you observe Passover, its celebrations underscore powerful themes of strength, hope, and triumph over adversity and anti-Semitism.

A Brief History of Matzoh: 'It's Not Supposed To Taste Good'

Restrictions around matzoh are meaningful and refreshing to many: here’s why.

— By April Fulton | Published: May 17, 2023

Matzoh is central to Passover, when Jews are prohibited from eating leavened food. Matzoh must be baked within around 18 minutes to prevent rising. Photograph By Becky Harlan, National Geographic Image Collection

Matzoh, known by Jews worldwide as “the bread of affliction,” is a cracker-like food made of flour and water eaten to commemorate the Hebrew slaves’ exodus from Egypt. The bland crisp takes the place of bread for the eight days of Passover.

While the aforementioned affliction may have changed over the years from one of desert-trekking deprivation to palatal hardship, most Hebrew scholars agree on one thing: It is not supposed to taste good.

Yet, for at least the first day of the holiday, many people actually crave it. Why?

For answers to this burning question about the nature of matzoh, we turn to Michael Wex, the author of Rhapsody in Schmaltz: Yiddish Food and Why We Can’t Stop Eating It.

“Now we eat it because we don’t have to eat it,” he says. In other words, because God’s chosen people have other choices the rest of the year, they look forward to eating matzoh to commemorate when Jews had no other choice but matzoh. And when it pops up in the grocery stores, many non-Jews pick up a few boxes, too.

According to the Hebrew bible, after a long protracted battle that featured God-directed plagues like frogs, boils, locusts, and the slaughter of first-born sons, the Egyptians freed the Hebrew slaves. The Jews left hastily, without time to let their bread rise. God basically tells them to take their dough and go, and that they’ll be cut off from Him if they eat anything leavened, i.e. yeasted or risen, for seven days. Hence—the first matzoh—the “roadside fast food from the ancient near East,” as Wex calls it.

The Passover seder dinner is centered around the matzoh, and is a virtual reenactment of the story of Exodus. In our family, the long, ritualistic dinner is frequently summed up for uninitiated guests in this way: “They tried to kill us, we’re still here, let’s eat.”

And so we eat matzoh, both plain and in forms that attempt to make it more palatable by adding salt and egg to create dumpling-like matzoh balls for chicken soup; or by topping it with sugary jam. Kids particularly love chocolate-covered matzoh for dessert.

Yes, there are other foods served at Passover, much of which varies according to where you’re from or what your grandma always made. Ours almost always includes brisket, kugel (a kind of casserole), and some kind of token vegetable. But matzoh is front and center.

There are strict specifications for making matzoh, of course. (Judaism is all about rules.) First of all, you only have 18 minutes from adding water to the flour to bake it. That’s the amount of time scholars say you have before the dough starts to rise, which would make the whole business un-kosher for Passover.

The result is a thin, flat plate-sized wafer “without even a kiss of salt,” Wex says. The first matzoh were probably round. The advent of machine-made matzoh led to the rise of the easier to pack and stack square marvel many of us know today. But the flavor? Pretty much the same, to my taste.

Traditional matzoh is broken ceremoniously at the beginning of the Jewish Passover seder.

There are also prescriptions for the matzoh to be harvested at a certain time of day and when it is dry enough, as prescribed by a rabbi, to prevent fermentation (i.e. leavening.) Dan Barber, back-to-the-land advocate and chef, made the case that the result of this close supervision may mean the wheat harvested is of higher quality, and therefore Jewish law may actually make food taste better.

But Wex and other scholars say this is beside the point. From Rhapsody in Schmaltz:

“There are those who say that God gave us cardboard so that we could describe the taste of matzoh, but taste is what matzoh is not about...Matzoh doesn’t need to be good, it only needs to be there—inside of 18 minutes. Or 22, according to some authorities; however long it took to walk to Tiberias from Migdal Nunia, the probable home of Mary Magdalene—a single Roman mile.”

Wex argues that the creation of Jewish dietary laws, particularly as they relate to matzoh, create for Jews a sense of otherness. While rules like no pork and no cheeseburgers may seem oppressive these days, in ancient times, it gave the Jewish people a new way of thinking. Once they were no longer slaves, they were “free to act in ways that have nothing to do with Egypt,” including, throwing out all their learned notions of what to eat.

There are entire Jewish communities, of course, who follow the ancient prescriptions to the letter for Passover and beyond. But do modern Jews still need to follow these ancient laws? Wex says you can have a strong Jewish conscience and not follow the dietary laws, but you should understand them “if you want your religion to stick around.”

The Very Ancient Passover of One of the Smallest Religions in the World

For thousands of years, the tiny Samaritan community has observed Passover according to its biblical laws.

— By Kristin Romey | Published: April 19, 2019

Samaritan boys wrangle a goat towards the sacrifice grounds on Passover eve in Kiryat Luza, West Bank. Photograph By Simon Norfolk

Samaritans are one of the world’s smallest religious groups, claiming descent from three of the 12 tribes of ancient Israel. They consider themselves the true observants of Israelite religion, and view Judaism as a religious practice corrupted during the Babylonian exile. This separation is clearly delineated in the geography of the Holy Land: While Mount Moriah in Jerusalem is where the Jewish Temple was decreed by God, the Samaritans followed the command of that same God and built their temple on the peak of Mount Gerizim, some 30 miles to the north.

Samaritan elders gather during the Passover eve sacrifice. There are a little more than 800 people in the Samaritan community, almost evenly divided between the Tel Aviv suburb of Holon and the West Bank village of Kiryat Luza. Photograph By Simon Norfolk

Today, Mount Gerizim, at an elevation of almost 3,000 feet, is one of the highest points in the Palestinian territories, and commands a sweeping view of the bustling city of Nablus and the West Bank villages that surround it. On its ridge is the village of Kiryat Luza, where, on the eve of each Passover, the roughly 800 members of the Samaritan community gather to pray and observe their liberation from slavery in Egypt.

Left: A young Samaritan boy wears a distinctive red hat known as a tarbush. Right: worshipers and visitors mingle as the sacrificed goats roast for hours in large pit ovens. Photographs By Simon Norfolk

In remembrance of that event, the Samaritans follow the Torah mandate that a sheep or lamb be sacrificed on Passover eve and consumed before dawn of the next day. In Kiryat Luza, this is a communal event, in which prayers are recited and dozens of animals are dispatched simultaneously by men dressed in all white and then roasted in enormous earthen pits. In the hours after midnight, the meat is heaped on trays alongside bundles of bitter herbs and dished out in a celebratory community gathering under the stars.

Following a group countdown, these Samaritan men will simultaneously plunge their skinned and dressed offerings into the blazing earthen oven. All of the meat must be eaten or burned before the sun rises on the first day of Passover. Photograph By Alessio Romenzi

Seven days later, the Samaritan community marks the end of Passover with a more solemn event. Once again under the stars just a few hours before dawn, the white-robed men of the community gather in front of their small synagogue, young sons beside them, rubbing the sleep from their eyes.

Led by their head priest cradling a silver Torah case, the men ascend Mount Gerizim in the darkness, climbing stone steps past the remains of their temple, destroyed by the Hasmoneans in the early second century B.C., and the rubble of a church built on their sacred peak by the Byzantine emperor Zeno some 600 years later. At points along the ascent, they stop to pray and then continue on as the dawn sky turns periwinkle and the paper-thin blossoms of scarlet poppies begin to unfurl.

On the seventh day of Passover, white-robed Samaritan men climb to the peak of Mount Gerizim, where their ancient temple once stood. Photograph By Simon Norfolk

The procession ends near a stone slab believed by Samaritans to be the site where Abraham intended to sacrifice his son Isaac. The sun breaks above the horizon and the high priest raises the shining Torah case above his head as he concludes the group prayer. It’s a spring day on Mount Gerizim, and once again this tiny community has gathered together to fulfill its sacred duties before God.

#Judaism ✡️ | Holidays | Bible | Traditions | Diseases#History | Culture#Civilization#People#Water 💦#Ancient Egypt 🇪🇬#Religion#Baked Goods#Food 🍲🍱🥘

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

warraw track 8 wednesday

22 notes

·

View notes