#leo szilard

Text

You watched Christopher Nolan's "Oppenheimer" and now want to learn more about some of the scientists that were involved and the history of the Manhattan Project? Then I recommend "Pandora's Keepers" by Brian VanDeMark. The book takes a closer look at not just J. Robert Oppenheimer, but also Hans Bethe, Niels Bohr, Arthur Compton, Enrico Fermi, Ernest Lawrence, Isidor Isaac Rabi, Leo Szilard and Edward Teller. The book is a history book more so than a science book, most of the scientific explanations mentioned around the making of the bomb, aren't too complex to understand for readers who aren't experts on the matter.

#physics#oppenheimer movie#oppenheimer#nuclear physics#quantum physics#particle physics#hans bethe#niels bohr#edward teller#enrico fermi#leo szilard#ernest lawrence#arthur compton#isidor rabi#pandora's keepers#history#manhattan project

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

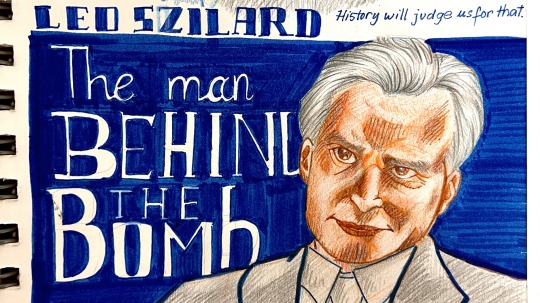

Daily warm-ups but make it Oppenheimer Characters Day 4:

Leo Szilard, played by Máté Haumann

Oppenheimer: Just because we are building it doesn’t mean we get to decide how it is used.

Szilard: History will judge us for that.

“You’re the great salesman of science. You can convince anyone of anything. Even yourself.”

Interestingly, Oppie basically said the same thing to Teller afterwards (check my last post for the quotes). On one hand, we have Szilard, the man conceived and patented nuclear chain reaction and unintentionally kickstarted the Manhattan Project, dedicated his life to prevent nuclear arms use. On the other, Teller went on creating the H-Bomb, which is said to be 1000 times more powerful than the A-bomb.

Intentionally or not, these two really represent the two faces of science.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

SZILÁRD LEÓ

Oppenheimer (2023)

#oppenheimer#leo szilard#szilárd leó#haumann máté#filmgifs#filmedit#movieedit#fyeahmovies#tvfilmsource#tvandmovies#userthing#userstream#martian gang in oppie lets goooooooo we won

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Barbenheimer Day!

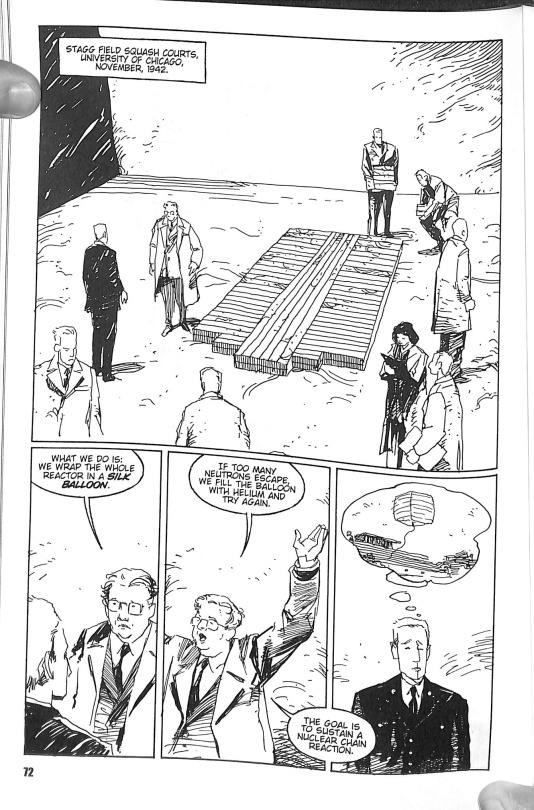

In celebration of both films being released, we thought we'd bring to you one of our books about J. Robert Oppenheimer: Fallout: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Leo Szilard, and the Political Science of the Atomic Bomb (2001) by Jim Ottaviani, Janine Johnston, Steve Lieber, Vince Locke, Bernie Mireault, and Jeff Parker. Fallout is illustrated by several artists, with a sample of their different styles shown here.

The Browne Popular Culture Library (BPCL), founded in 1969, is the most comprehensive archive of its kind in the United States. Our focus and mission is to acquire and preserve research materials on American Popular Culture (post 1876) for curricular and research use. Visit our website at https://www.bgsu.edu/library/pcl.html.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Popular responses to Christopher Nolan’s latest cinematic offering, Oppenheimer, have generally been positive, with the film generating unexpected commercial success given its length and subject matter. However, audience opinion has been polarized regarding the film’s political implications, bifurcating in accordance with the lines along which people have interpreted its ideological content. Some have read Oppenheimer as an indictment of its titular character, typically praising the film for not shying away from the physicist’s personal shortcomings (like his arrogance or infidelity) or attempting to justify them.

For them, the film also shows Robert’s complicity in the most devastating war crime ever committed by foregrounding such details as his justification for continuing the Manhattan Project post-Hitler’s suicide and his refusal to sign Leo Szilard’s petition against dropping the bombs on Japan. Another strand of popular discourse, however, has gone the other way and accused Nolan of whitewashing the image of J. Robert Oppenheimer by de-emphasizing the horrific outcomes of his actions (such as by keeping the harrowing images of Hiroshima and Nagasaki offscreen) and portraying him as skeptical when it comes to atomic weaponry by glossing over his moral culpability in making them possible.

For this latter camp, the film’s decision to utilize Oppenheimer’s victimization at the hands of the Gray board as a framing device to bookend the narrative meant a shift in perspective from ‘Oppenheimer as perpetrator’ to ‘Oppenheimer as victim.’ For still others, the film has seemed to be a balancing act between these two contradictory tendencies, with the criticism and the sympathy canceling each other out to varying effect: for some, a fair representation of a complicated historical figure, while for others, a politically-toothless blockbuster looking to cover all bases.

Despite the differences between these positions, the common axis around which they revolve concerns a moral assessment of Oppenheimer as an individual, both as a man sustaining frayed personal relationships and as the physicist who made nuclear warfare possible. The film gets read merely as an exploration of Oppenheimer’s guilt, with opinions differing as to the success or failure of the depiction. The questions implicitly posed by such discourse tend to be of the following type: How are we to think of Oppenheimer and his legacy more than eight decades after the inception of the Manhattan Project? How should history judge this complicated figure, and what lessons could we draw regarding brilliant (but flawed) individuals occupying positions of power during times of global crisis?

Such considerations, while valuable, nevertheless seem too restricted to the level of the individual and inevitably miss the most crucial point to be derived from Oppenheimer, one underscored by its closing scene involving an ominous exchange between Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) and Albert Einstein (Tom Conti) at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. “When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world,” says Robert, recalling a previous meeting between them.

Einstein confirms that he remembers the meeting well, and then Oppenheimer’s spine-chilling follow-up comes: “I believe we did.” The film ends with a montage of nuclear warheads launched, eventually engulfing the planet and triggering atmospheric ignition, cross-cutting with grief-stricken close-ups of Cillian Murphy’s face. Of course, Oppenheimer doesn’t refer here to having started an actual nuclear reaction and set fire to the atmosphere, which was the genuine worry at hand during his prior meeting with Einstein. Instead, he draws a revealing parallel between nuclear weapons and the scientific-military-industrial complex that facilitates them by analogizing the chain reaction that characterizes them both–forever threatening to spiral out of control with catastrophic consequences.

In these final images of the film, the fear and grief writ large on Oppenheimer’s face thus have little to do with either atmospheric ignition or even the specific dangers posed by nuclear weaponry. They reflect, instead, his confrontation with a final revelation – one that comes perhaps too late in his own life. It’s an acknowledgment of the tragic course taken by scientific reason in general (“the culmination of three centuries of physics,” as his colleague Isidor Rabi put it), which seems to lead inevitably to a paradox through its weaponization. The grand institution of science and technology, long heralded as the flagbearer of enlightenment rationality and progress, seems to produce scenarios that violently contradict its own utopian ambitions with the existential threats it generates.

The more pertinent questions raised by the film then become the following: How come “three centuries of physics” ultimately lead to a paradoxical scenario where its progress becomes the foundation for an existential threat, despite peerless geniuses like Oppenheimer and Einstein being fully cognizant of such dangers? And what does this indicate regarding our pursuit of technological progress itself, usually widely accepted as an unquestioned universal good? This essay shall probe such questions through a reading of Oppenheimer, which aims to bring forth and examine these fundamental contradictions (mirrored by the film’s contradictory characterization of Oppenheimer himself) and thus interpret the film as an alarming representation of the tragedy afflicting the very heart of our project of scientific-technological modernity.

The Tragic Subject of Oppenheimer

As the film opens with Oppenheimer reading his statement to the members of the Gray board security hearing, the first introduction we get to this character is through a flashback to his days spent at Cambridge, where he attempts to poison his tutor Patrick Blackett (James D’Arcy) with a cyanide-laced apple after being antagonized for his subpar laboratory work. This early instance of a young Robert responding under duress and lacking control over a situation almost instinctively with the urge to kill seems to foreshadow his eventual historical legacy–as the man fated to spearhead the single most violent act of death and destruction in human memory.

It’s tempting to read this sign as indicative of the ‘tragic flaw’ within Oppenheimer, which, despite his best intentions, sets him down a dark, winding path and ultimately becomes his undoing. But, as we shall see, such attempts to locate the roots of tragedy within Oppenheimer, arising from his personal attributes, would be to misrecognize how the tragic element manifests across the film’s narrative.

As per the classic Aristotelian theory of tragedy, hamartia (most commonly translated as ‘tragic flaw’) is responsible for the series of events affecting a movement from a state of felicity to disaster for the tragic hero, bringing about their downfall. Traditionally, hamartia has been understood to be some inherent character defect that gets in the way of the (otherwise virtuous) hero’s attempts to retain control over their fate and, as such, the possibility of depicting the downfall of a wholly virtuous (or villainous) character, as tragedy, was ruled out.

Later critics like Jules Brody have contested this interpretation of hamartia and insisted that it be understood as a morally neutral term, indicating a chance accident. It’s deemed an unforced error that leads the hero to ‘miss the mark’ (literal translation of the verb hamartanein). Like an archer inadvertently missing their mark, not due to lack of trying or inherent moral deficiency, tragedy manifests as a contingency that unalterably sets the course towards downfall. As opposed to the classical notion, this interpretation of hamartia emphasizes its externality and autonomy relative to the character: tragedy, in this vein, is that which strikes not because one is inherently flawed (for then their downfall is merely the comeuppance they already deserved) but due to something that lies radically outside the bounds of one’s will.

However, neither of these two interpretations of hamartia fits the tragedy of Oppenheimer, for they oscillate between locating it either entirely within the character or entirely without them while positing the character’s actions as the site where the tragic element takes root. To take the classic example of Oedipus Rex, where Oedipus fails to recognize his father Laius at the crossroads and kills him, the tragic error is attributed either to Oedipus’ hasty behavior because of his hubris (as per the classical notion) or to sheer bad fortune. But in both cases, it’s something that Oedipus (and Oedipus alone) does that actualizes the tragedy.

In both cases, Oedipus’ actions evince regret in him, and if he could’ve gone back in time and done things differently, it’s clear that he would’ve avoided slaying the man he meets at the crossroads. This isn’t true, however, for Oppenheimer. As the character of Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.) reminds us, Robert never once admitted to having regrets over Hiroshima and that ���if he could do it all over, he would do it all the same.” Admittedly, the latter claim isn’t a factual observation but something that Strauss rhetorically puts forth to make his case against Robert. Still, it does lead one to wonder: What precisely could Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer have done differently, had he the chance to turn the clock back, so as to effect any different outcome?

He certainly couldn’t have stopped the nuclear race from ever starting, for that becomes inevitable the moment the atom is split by scientists in Nazi Germany and, a year later, World War II breaks out. Perhaps he could’ve more strongly opposed the decision to bomb Japan. Yet this argument misses the fact that the hindsight with which we now assert that the Japanese surrender wasn’t due to the bombs but rather the USSR’s entry into the war on 9th August 1945, was not something that was prophetically available to Oppenheimer who, like his fellow scientists, could only act based on information fed to him by the US military. Further, it is known that Generals Eisenhower and MacArthur, and even Truman’s chief of staff Leahy, went on record to condemn the atomic bombs as “either militarily unnecessary, morally reprehensible, or both,” and yet Truman went ahead anyway.

It’s fair to say that a “humble physicist” like Oppenheimer, especially with his personal “questionable associations,” could have done little to sway Truman. This isn’t to absolve Oppenheimer of all personal responsibility or claim that he always acted ideally. But it is to assert that the question of the violent trajectory taken by scientific rationality–culminating in nuclear weaponry but certainly not restricted to the bombings in Japan–cannot simply be reduced to the individual decisions taken (or not) by Oppenheimer (and other scientists like him), regardless of whether these decisions were motivated by inherent tragic flaws or brought about by chance circumstances.

We thus note how the existing notions of hamartia are ill-equipped to adequately account for the tragedy of Oppenheimer and preclude the possibility of deriving a politicized critique: the classical notion attributes all responsibility to the individual afflicted by the tragic flaw. In contrast, the latter notion leaves it all to accident. What’s necessary here is a way of configuring hamartia that situates it neither entirely within a character nor without them. Instead, it accounts for the dialectical relationship between inner subjectivity (acting upon outer reality) and external structures (determining and constraining the subject from within).

After all, the ‘tragic flaw’ manifests as most tragic precisely when it appears to be located within, leading us to proclaim the character as inherently flawed, even as its ultimate genesis lies elsewhere. Hamartia, in this case, must thus be located as being extimate to the character – deriving from the Lacanian concept of “extimacy,” a portmanteau of the two mutually contradictory words “external” and “intimacy.” Extimacy refers to a dissolution of the usual demarcation between interior and exterior and thus reframes the question of hamartia – no longer understood as some moral deficiency but rather as a mode of subjectivity volitionally adopted by the character as their own, but which nevertheless is founded in the external structure that produces the subject.

To view the ‘tragic flaw’ in the narrative as extimate to Oppenheimer is to insist that it operates through him, even as its origins remain radically outside him. As shall be discussed in the next section, this shows up in the film as Robert’s significant psychical investment in Enlightenment-era rationality–as embodied in the ideals of scientific progressivism and bureaucratic due diligence–a structure of which he is a product through and through. As the film unfolds, this structure unravels for Oppenheimer to reveal at its heart a gnawing irrationality, manifesting through his often contradictory behavior as well as the rising sense of a loss of control (which Einstein also brings up in the final scene) and the tragic realization of his own helplessness in the face of it all.

Enlightenment and its Discontents

Regardless of the wide variety of opinions out there regarding Oppenheimer, there seems to be a near-universal agreement in describing him as a deeply contradictory character, something that Nolan’s film also evokes in numerous ways. Edward Teller’s (Benny Safdie) testimony of Robert’s actions as “confused and complicated” may not have been entirely fictional, and we see how the Gray board leverages the apparent contradictions in Oppenheimer’s behavior (like his shifting position with respect to the H-bomb) to persecute him.

Additionally, Robert often behaves in ways that undermine his personal position, like admitting to prosecutor Roger Robb (Jason Clarke) that the communist Haakon Chevalier (Jefferson Hall) is still his friend. We also see him arguing more than once that the scientists’ role as creators of the bomb does not give them any greater right to dictate whether it’s used, even as we see him doing precisely the same while convincing his colleagues of the need to unleash the bomb despite Nazism no longer being a threat.

Oppenheimer’s contradictions can only be fathomed if we first recognize that he’s a Kantian liberal subject through and through, implicitly following the rational framework elaborated by Immanuel Kant in his seminal essay “What is Enlightenment?”. The path to Enlightenment, Kant wrote, lay in maintaining a clear separation between private and public uses of reason and in having a state form that freely allowed the maximization of both. Put simply, the difference is as follows: private use of reason refers to executing one’s assigned duties in the specific role (teacher/scientist/lawyer/banker, etc.) one occupies within civil society, whereas public reason refers to performing one’s greater duty towards society as a whole, i.e., by speaking out and protesting, according to one’s convictions, against that which threatens the so-called “common good.”

With the one hand, you oil the wheel that turns (for that is your job), and with the other, you mend the spokes that are broken –this seems to be the model of Enlightenment rationality that also governs Oppenheimer. “Argue as much as you like and about whatever you like, but obey!” wrote Kant, his blueprint acting as an injunction to people to speak out against the status quo as and when necessary, but not at the cost of neglecting their duties (for without the latter, society itself would break down).

One clearly sees this tension between ‘arguing’ and ‘obeying’ play out in the film through (among other things) Oppenheimer’s engagement with the communists, neither officially joining them nor entirely giving up on their cause. Oppenheimer is quick to ‘argue’ alongside his fellow members of the F.A.E.C.T when it comes to showing solidarity with “farm laborers and dock workers” and insisting that “academics have rights too.”

He is also quick to ‘obey’ when Lawrence (Josh Hartnett) convinces him of the need to tone down his political activity so that he can do his duty, showing the ability to be “pragmatic.” It’s fascinating to see how Robert goes out of his way to inform the authorities about Eltenton (Guy Burnet) because it’s his duty as a law-abiding citizen to report espionage attempts. Yet, he also resists the persistent Colonel Pash (Casey Affleck) to keep Chevalier’s name concealed, spinning lies that would return to hurt him later.

In fact, Robert’s lifelong commitment to ‘arguing,’ i.e., not letting the exigencies of private ends trammel over public reason, is precisely what separates him from Lewis Strauss, whose perspective is taken up in the parallelly-running storyline shot in black and white. While Strauss has spent his whole life climbing the social ladder by greasing the right palms and pleasing the right people, Oppenheimer, in contrast, was (in)famous for speaking his mind (almost to the extent of seeming arrogant) and standing up for causes he believed in, regardless of potential political backlash.

It’s telling that when the senate aide (Alden Ehrenreich) was pushing the question of who targeted Oppenheimer and why, Strauss mentions that “Robert didn’t take care not to upset the power brokers in Washington” (which undoubtedly Strauss always took care to), before recounting the tale of his humiliation in the case of exporting isotopes to Norway. Oppenheimer’s real ‘crime,’ for which Strauss takes it upon himself to punish him, lay in this insistence on always keeping private and public reason separate and for not backing down on his stance against further nuclear armament or paying enough importance to influential individuals to bow to them. His folly, perhaps, lay in thinking that the state structure was rational enough to tolerate the same.

Underlying this two-pronged mode of rationality that Oppenheimer embodied is the assumption that the exercise of reason can act as it’s own corrective, i.e., the threat of rationality leading us into error and excess is countered by rationality itself, in recognizing such dangers and undertaking appropriately rational countermeasures. Yet this would be to presume a state form that also functions rationally, where private and public uses of reason can be kept separate, which is only possible in an age of globalization under the aegis of something akin to “world government” as Lewis Strauss puts it in the film, which Oppenheimer imagines functioning through “the United Nations as Roosevelt intended.”

However, nearly two centuries after Kant, the world in which Oppenheimer finds himself is ruled by division and strife, where the imagined separation between private and public usage of reason often collapses – such as when it becomes the very duty of scientists to help fashion weapons of mass destruction, which contradicts their greater responsibility as rational agents to society at large. The Kantian model presupposes a state form that allows for both obedience and argument and thus leads to contradiction in situations where argument itself amounts to disobedience, like when Oppenheimer’s continued opposition to the H-bomb project is framed as a betrayal of his patriotic duties.

Nolan’s film shows us how nation-states’ fractured and warring imaginaries constantly undermine the promises of Enlightenment rationality – promises of scientific progress and peaceful prosperity – both on micro and macro scales. One of the dominant antagonisms staged throughout the film is between the US military’s policy of compartmentalization and the values of transparency and open communication that are key to the institution of science. “All minds have to see the whole task to contribute efficiently,” as Oppenheimer tells General Groves (Matt Damon), which really applies not just to the scientists working at Los Alamos but also to humankind in general, engaged in the Enlightenment project of reaping the benefits of scientific progress while protecting against its dangers. All humanity, setting aside mutual differences, must together see to dangers that threaten us on a planetary scale, whether nuclear bombs or the worry of climate change.

The essence of compartmentalization, which lies in damming the tendency of knowledge and information to circulate freely, shows itself to be irrational insofar as it seeks only to further private interests (in Oppenheimer’s case, that of the US military) at the cost of public ones. As Oppenheimer discovers, to his great horror, his hopes of international cooperation preventing the nuclear race from spiraling out of control seem utterly fanciful given the utmost hostility between the two world superpowers. The contradiction is made explicit with great force in the scene where Oppenheimer meets President Truman (Gary Oldman). He assures the President that the Soviets, too, have abundant resources to build a nuclear arsenal, hoping his reasoning sufficiently convinces the President to shut down Los Alamos and enter arms talks with the USSR.

In response, Truman’s Secretary of State James Byrnes (Pat Skipper) takes Robert’s observation to conclude the exact opposite, arguing that the USSR’s nuclear potential means that they have to “build up Los Alamos, not shut it down,” which shows how incompatible Oppenheimer’s rationality is within such a fundamentally irrational state. At this moment, Robert realizes the error he has been led to with his investment in Kantian rationality, its inherent contradictions growing steadily apparent, as he remarks to the President, “I feel like I have blood on my hands.” It’s one thing to imagine this blood to be representative of the deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, massacres which (as previously discussed) Oppenheimer wasn’t entirely responsible for and nor could have prevented singlehandedly.

But insofar as the line follows Byrnes’ conclusion, the blood on Oppenheimer’s hands should indicate something far ominous: that is, his involvement within the institution of science and technology – itself a part of the greater Enlightenment project of modernity – leading to a scenario where he has given humankind “the power to destroy themselves,” as Neils Bohr (Kenneth Branagh) puts it. The idea of Enlightenment, a word referring to the state of being illuminated, of the production of light to cast out darkness, thus attains perversion in the spectacle of the atomic explosion–popularly held to be “brighter than a thousand suns”– which paradoxically for Oppenheimer back then also necessarily represented the zenith of scientific progress that he had helped reach.

Technology as Revelation

That the zenith of scientific progress should appear as an act of bringing to light in Oppenheimer perhaps hints at something of the essence of this act of putting science into use, of “taking theory and turning it into a practical weapons system,” as Robert tells Groves. For the German philosopher Martin Heidegger, the essence of technology lay in revelation–understood as the movement from a state of concealment to unconcealment. “Technology is a mode of revealing,” wrote Heidegger in his essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” referring to how science apprehends the natural world to bring forth what would have eluded us otherwise.

We need only think of some of the earliest examples of human technology to get the point across: the harnessing of fire, for example, reveals the nutritional value concealed within plants and animals to be used as sustenance, while the plow that turns the earth reveals the fertility of the soil that’s otherwise inaccessible. It was crucial for Heidegger that we do not fall into the usual trap of imagining technology as something neutral in itself, as merely instrumental means to ends, its purpose defined entirely by how humans use it. To imagine technologies as disparate as the windmill and the atomic bomb as mere instruments at the mercy of humans, while not technically incorrect, reduces them to a false equivalency that obscures their vastly differing essences.

More importantly, it obscures their telos, i.e., their ultimate (intended) purpose, which must also be held responsible for their creation in the first place, for no one imagines that the telos driving the manufacture of windmills and atomic bombs to be anything similar. Thus, for Heidegger, it’s important that we apprehend technology’s essence as ‘revelation’ so that we may better appreciate how the technologies we use constrain (and are constrained by) the realities they bring forth. Revelation in this manner, for Heidegger, thus involves a “bringing-forth,” i.e., something is brought forth from obscurity and into sight. The windmill, for example, can tap into currents of air and bring forth the same as electrical currents, which can then be harnessed as electricity.

The idea of technology as a mode of revealing is acknowledged most directly in Oppenheimer during the scene where Secretary of War Henry Stimson (James Remar) discusses dropping the bomb on Japanese cities, and Robert describes it as “a terrible revelation of divine power.” That the bomb’s power is defined as divine (god-like and thus not of the world of humans) is, of course, no mere coincidence, and harks back to the now-infamous line from the Bhagavad Gita quoted by Oppenheimer, “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds,” typically misunderstood to imply Robert’s identification with the figure of death, given his role in pioneering the atomic bomb.

In the Gita, however, it is told to Arjuna by Krishna, the latter taking on the form of Vishnu’s multi-armed self and thus refers to a moment of identification between death and divinity. Death appears to Arjuna in the form of Vishnu (and to Oppenheimer in the form of the atomic explosion) as something terribly divine, something so otherworldly that he, a mere mortal, cannot possibly hope to comprehend or control it. Later, following the Hiroshima bombing, we hear Truman on the radio describe the bomb as “a harnessing of the basic powers of the universe.” Read together, the technology of the atomic bomb can thus be described as a harnessing of the basic powers of the universe so as to effect a revelation of divine power.

The paradox becomes apparent: what’s harnessed is that which belongs to the fundaments of this world, even as what’s revealed feels like something otherworldly (transcending the limits of the human) – as if to imply the presence of the otherworldly (albeit concealed) within the very building blocks of our reality. Once again, we have here a relation of “extimacy,” in that technology takes the base matter of our world (its natural resources and the physical laws governing them) and contrives it to reveal something that appears external to us insofar as it threatens to exterminate the world.

It is this trait of modern technology, as seen most visibly in atomic bombs but certainly not limited to them, to ultimately objectify its subjects (i.e., human beings), becoming external and even opposed to them concerns Heidegger. He characterizes the logic governing modern tech as a “challenging-forth,” a “setting-upon,” that separates it from older technology where the revelation involved was merely a “bringing-forth.” He contrasts the windmill, which simply taps into air currents already flowing, with the modern activity of coal mining: “. . . a tract of land is challenged in the hauling out of coal and ore.

The earth now reveals itself as a coal mining district, the soil as a mineral deposit”. The difference between the windmill’s “bringing-forth” and the coal miner’s “challenging-forth” is that the former resembles receiving gifts from Mother Nature doled out generously. At the same time, the latter is active exploitation of nature, motivated by the single capitalist logic of “maximum yield at minimum expense.”

Revelation as “challenging-forth” thus affects a pretty different kind of unconcealment that Heidegger describes: “Everywhere everything is ordered to stand by, to be immediately on hand, indeed to stand there just so that it may be on call for a further ordering. Whatever is ordered about in this way has its own standing. We call it the standing-reserve”. The phrase derives from the idea of standing armies forming the military reserve forces. It refers to a peculiar ordering of natural elements wherein they stand by, at hand, and ready for use instead of being freely scattered within the world in their natural forms.

Oppenheimer neatly illustrates the idea through the recurring imagery of spherical glass bowls being gradually filled with marbles, representing increasing quantities of refined uranium and plutonium, standing by, ready to be used as fissile material. This process represents how science and technology reveal the contents of our world as mere means, as things to be used to achieve our desired ends, and not as ends in themselves. The logic of technology subjects humans to a view of the natural world as something that exists only for the purpose of being harnessed for profit, overriding the idea of its existence in its own right.

The problem with this logic of turning nature into the “standing-reserve” is, of course, that eventually, it extends to humans themselves – humans who, as part of the same natural world, are also made part of the “standing-reserve” of science and technology. “The current talk about human resources, about the supply of patients for a clinic, gives evidence of this,” writes Heidegger. It is to effect a depreciation in the value assigned to humanity itself. It marks that moment wherein technological revelation starts appearing as something external to humanity – external insofar as technology now seems turned against humans themselves and thus out of their control. Indeed, that is how the “terrible revelation of divine power” must have appeared to the hundreds of thousands massacred at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who became mere fodder for imperialist war games and who tellingly don’t appear in Oppenheimer except in the form of mere statistics.

Modern technology, thus, as a form of revealing that “challenges-forth” and turns nature into the “standing-reserve”, contains within itself a paradox: As humans keep utilizing scientific knowledge to exploit the natural world for profit and using the profit to further its technologies to better exploit nature (not unlike a chain reaction), eventually the logic of natural exploitation – now magnified manifold – threatens to engulf humankind itself.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of Oppenheimer is the realization that this existential threat is not well appreciated until it gets displayed in some form, as when Robert justifies continuing the Manhattan Project despite Hitler’s death, claiming this would encourage deterrence. By insisting that “they won’t fear it until they understand it, and they won’t understand it until they’ve used it,” Oppenheimer directly invokes the logic of revelation–for if technology is a mode of revealing, as Heidegger insists, it seems like the culmination of technological progress must consist in the revelation of its own catastrophic potential, so that we may learn to curb the same before it’s too late.

Oppenheimer beyond Oppenheimer

In an interview about the film, Oppenheimer’s co-producer Emma Thomas describes it as a “cautionary tale,” hoping it leaves viewers with more troubling questions than straightforward answers. But it’s hard to see how Oppenheimer can function as a cautionary tale as long as the discourse around it centers on an assessment of Oppenheimer himself and the story of his moral culpability and guilt. Understandably, popular opinion has fixated upon the depiction of the individual more so than anything else, given that Oppenheimer has been marketed as a biopic. Additionally, the buzz around Nolan’s decision to write his screenplay in the first person so as to tell the story from Oppenheimer’s subjective perspective undoubtedly contributed to prejudice regarding the film’s ambitions, shifting the focus to the man himself rather than the story unfolding around him.

But what this decision does for the film is actually quite the opposite, i.e., by locking the viewer onto Oppenheimer’s perspective, the film eschews a moral judgment of Oppenheimer himself (for that requires us to view him objectively). It encourages a questioning of the structures that made this tragedy possible. In watching the film, the audience is made to feel like “we’re on this ride with Oppenheimer” (as Nolan put it), and this formal identification with the protagonist dissuades attempts to make it all about him, as has primarily been the case with previous attempts at telling the story of the atomic bomb. The idea isn’t dissimilar to the proverbial walking of a mile in someone else’s shoes, which indicates a movement away from making that person the sole object of one’s critique.

It is here that popular discourse around the film, centering on a moral judgment of Oppenheimer and his guilt, falls short: the more significant point alluded to by the film’s closing moments isn’t about whether Oppenheimer was the devil for having commandeered the Manhattan Project to success or a saint for advocating arms control. It certainly isn’t about the role of individual responsibility in overseeing projects of seismic importance (as if a different set of personnel could’ve ensured a different historical outcome). It’s easy enough to investigate some tragic event and have the buck stop with some individual figure to arrive at some scapegoat upon whom responsibility is pinned in order to be relieved of the labor necessary to interrogate systemic factors that keep reproducing such tragedies.

To the extent that Oppenheimer portrays its titular character as flawed, it’s also careful to show us that Robert himself was acutely aware of his flaws and felt remorseful. And as his friend Chevalier notes: “Selfish and awful people don’t know they are selfish and awful.” But it’s precisely by presenting this sympathetic portrayal of the man Oppenheimer that the film encourages a more careful reading of his position within the scientific-bureaucratic apparatus, one that transcends individual specificities, suggesting a sense of fatality with which the events of the movie are tainted and imploring us to derive a critique of this apparatus itself.

Of course, the film is about Oppenheimer’s life and work and depicts the same in detail, but this focus on the man himself is not an end in itself but merely the means to get beyond the man and explore what made, drove and ultimately tormented him. Paradoxical as it may sound, given the film’s text, the title of Oppenheimer may be less of a reference to the famous physicist himself and more of an indication of the historical subject position that was once occupied by Robert but now endures despite him.

In numerous interviews, Nolan has mentioned how scientists working in AI often refer to the current AI explosion as their ‘Oppenheimer moment.’ In revisiting and rethinking the story of the nuclear bomb, perhaps it’s time that we stopped obsessing over what Oppenheimer could or should have done differently and instead broach the question of how such ‘Oppenheimer moments’ arise in the first place and how to tackle them. How come new developments in science and technology often strike us with fear and alarm when we should be rejoicing in the potential benefits they could bring us all? How come when news of developments in computerization, automation, and AI technologies hit the stands, the popular reaction is often one of dismay, stemming from fears of losing livelihoods rather than one of celebration?

“Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man; for this, he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity,” the movie’s opening frames inform us. Going by the film’s narrative, it’s easy to imagine that this refers to Oppenheimer’s persecution by the Gray Board under the animus of Lewis Strauss. But Prometheus was punished by the gods from whom he stole fire, not by men. Neither was Prometheus punished for regretting and having hopes of going back on his act, which happens in the case of Oppenheimer and the bomb. So, the ‘torture’ referred to in the quote has nothing to do with the tarring and feathering Oppenheimer undergoes throughout the film, culminating in him losing his security clearance for trying to minimize the fallout from his invention.

Instead, the idea of ‘stealing fire from gods’ in Oppenheimer’s case refers instead to the laws of physics and their harnessing by the institution of science and technology, which gives men such terribly divine powers as the atomic bomb. Being tortured for eternity, then, in this case, means living with the horror and fear that our technological progress can, at any moment, become our undoing. “Chances are near zero,” as we are told repeatedly, but that doesn’t stop Fermi from taking side bets on atmospheric ignition. It is this element of non-zero chance, this uncertainty that paradoxically (re)appears at the end of a long process of scientific inquiry and development based on values of certitude, that strikes as most tragic – that the hallowed project of gaining control over the natural world for human benefit has led to a real possibility of loss of control and human extinction.

In the film, Einstein astutely notes this to be a trait characterizing the “new physics” when Robert first comes to him with Teller’s troubling calculations, observing how they are “lost in your (i.e., Oppenheimer’s) quantum world of probabilities, and needing certainty.” But of course, it isn’t as if quantum mechanics itself introduces uncertainties into our world so as to destabilize it; rather, quantum mechanics – itself the culmination of “three centuries of physics”– only reveals the uncertainties that have long inhered in the world and in the scientific project itself, but which so far have remained concealed. Small wonder then that Bohr’s character insists that what they have is not just a new weapon but a new world.

Thus, rather than deriving a critique of Oppenheimer himself, a man long dead and gone, a far more fascinating and important discussion to be had from Nolan’s Oppenheimer would be regarding the ‘criticality’ of scientific reason itself. The notion of criticality, as used in the film, refers to that stage during which a nuclear chain reaction becomes self-sustaining, beyond which it becomes ‘supercritical’ and proceeds towards explosion. The institution of science in today’s world is similarly self-sustaining insofar as its narrative of technological progress requires no additional justification, insofar as even our response to science’s dangers usually tends to be more science.

Like a chain reaction, scientific progress feeds capital, which in turn feeds science and so on – a juggernaut advancing so autonomously as to almost be insulated against external criticism and the possibility of applying brakes. And carrying with it, all the time, the risk of ‘supercriticality’ – from CO2 emissions causing global warming to developments in AI causing job losses or worse, and so on. It’s precisely this tragic course of events, from rationality and control to irrationality and loss of control, irreducible to the individual and instead requiring deeper systemic interrogation of the fundamental assumptions underlying technological modernity, that Oppenheimer allegorizes in its tale of the atomic bomb and the man who fathered it.

The film lays bare the irrationality at the heart of the Enlightenment project of scientific progress and the paradoxes it leads to, mirrored by the paradoxes of the quantum world and manifesting in Oppenheimer’s contradictory subjectivity and the final tragic realization that despite his crucial role in the making of the bomb there was perhaps very little he alone could have done to change the course of history, a history that through his participation he also helps actualize.'

#Oppeneimer#AI#Emma Thomas#Albert Einstein#Christopher Nolan#The Manhattan Project#Leo Szilard#Cillian Murphy#Tom Conti#Institute for Advanced Study#Princeton#Isidor Rabi#Gray Board#Patrick Blackett#James D'Arcy#Lewis Strauss#Robert Downey Jr.#Edward Teller#Benny Safdie#Haakon Chevalier#Jefferson Hall#Roger Robb#Jason Clarke#Ernest Lawrence#Josh Hartnett#Boris Pash#Casey Affleck#George Eltenton#Guy Burnet#Alden Ehrenreich

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oppenheimer - Movie Review

Epic-maker movie “Oppenheimer”, directed by Christopher Nolan tells the story leading up to atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki towards the end of World War II that changed the course of history forever. The film is based on the Pulitzer Prize-winning book “American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer” by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.

Deeply heartrending…

View On WordPress

#atom bombs#“American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer”#“Oppenheimer”#“quantum mechanics”#Christopher Nolan#Cillian Murphy#cyclotron#Dylan Arnold#Earnest Lawrence#Emily Blunt#Epic-maker#Hiroshima#Josh Hartnett#Kai Bird#Leo Szilard#Lewis Strauss#Lt. Gen Leslie Groves Jr.#Manhattan Project#Martin J. Sherwin#Matt Damon#McCarthy era#McCarthyism#movie#Nagasaki World War II#Pulitzer Prize-winning#Robert Downey Jr.#Werner Heisenberg

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

He saw through the traps laid for him.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quote#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#leo szilard#debate#congress

0 notes

Text

Szilard's account of this first important conversation runs as follows:

The possibility of a chain reaction in uranium had not occurred to Einstein. But almost as soon as I been to tell him about it he realized what the consequences might be and immediately signified his readiness to help us and if necessary 'stick his neck out', as the saying goes. But it seemed desirable, before approaching the Belgian government, to inform the State Department at Washington of the step contemplated. Wigner proposed that we should draft a letter to the Belgian government and send a copy of the draft to the State Department, giving it a time limit of a fortnight in which to enter a protest if it believed that Einstein should abstain from any such communication. Such was the position when Wigner and I left Einstein's place on Long Island.

"Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists" - Robert Jungk, translated by James Cleugh

#book quotes#brighter than a thousand suns#robert jungk#james cleugh#nonfiction#leo szilard#eugen wigner#recollection#chain reaction#uranium#atomic race#albert einstein#belgium#belgian government#state department#washington#letter#protest#long island

0 notes

Text

Protocole Quap de Wells

est le 4e texte publié par Caroline Hoctan sur D-FICTION |

Herbert Georges Wells est l’inventeur de l’expression ” bombe atomique” ; son roman ” La destruction libératrice” a inspiré le physicien hongrois Leo Szilárd, qui permettra au scientifique de mettre au point la réaction en chaîne nucléaire. |

Je poursuis cette enquête qui vise à mesurer l’impact du phénomène nucléaire sur l’imaginaire…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

dreading the oppenheimer biopic. the way people romanticize him as a tragic figure makes me feel violent

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

PAKİSTANLI MÜSLÜMAN BİR BİLİM ADAMININ İLGİNÇ ARAŞTIRMASI..

Dünyada yalnızca 14 milyon Yahudi var;

~Amerika'da 7 milyon,

~Asya'da 5 milyon,

~Avrupa'da 2 milyon,

~Afrika'da 100 bin

Adet Musevi yaşıyor..

Soru: Pekiyi de kaç adet Müslüman İnsan var?

Cevap: 1,4 milyar Müslüman;

~1 milyar Asya,

~400 milyon Afrika,

~44 milyon Avrupa,

~6 milyon Amerika

Kıt'asında Yaşıyor.

👉Yâni Dünyada 1 Musevi’ye Karşın 100 Müslüman Var...

İyi ama Yahudiler Müslümanlardan niçin 100 kat daha güçlü ve daha zengin ve daha eğitimli ve daha mucitler?

Tarafsız ve Bilimsel Yollarla tespit edilmiş nedenlerini öğrenmek istiyorsanız lütfen okumayı sürdürün.

👉Tüm zamanların en etkin bilim adamı Albert EİNSTEİN bir Yahudiydi.

👉Psikanalizin babası Sigmund FREUD bir Yahudiydi.

👉Karl MARKS Yahudiydi.

Tüm İnsanlığa zenginlik ve sağlık katmış Yahudilere bakalım;

👉Benjamin Rubin insanlığa aşı iğnesini armağan etti.

👉Jonas Salk ilk çocuk felci aşısını geliştirdi.

👉Gertrude Elion lösemiye karşı ilaç buldu.

👉Baruch Blumberg Hepatit-B aşısını geliştirdi.

👉Paul Ehrlich frengiye karşı tedaviyi buldu.

👉Elie Metchnikoff bulaşıcı hastalıklarla ilgili buluşuyla Nobel ödülü kazandı.

👉Gregory Pincus ilk doğum kontrol hapını geliştirdi.

👉Bernard Katz nöromasküler iletişim kaslarla sinir sistemi arası iletişim alanında Nobel ödülü kazandı.

👉Andrew Schally endokrinoloji metabolik sistem rahatsızlıkları, diyabet, hipertiroid tedavilerinde kullanılan yöntemi geliştirdi.

👉Aaaron Beck Cognitive Terapi’yi akli bozuklukları, depresyon ve fobi tedavilerinde kullanılan psikoterapi yöntemini geliştirdi.

👉Gerald Wald insan gözü hakkındaki bilgilerimizi geliştirerek Nobel ödülü kazandı.

👉Stanley Cohen embriyoloji embriyon ve gelişimi çalışmaları dalında Nobel aldı.

👉Willem Kolff böbrek diyaliz makinesini yaptı.

👉Peter Schultz optik lif kabloyu, Charles Adler trafik ışıklarını,

👉Benno Strauss paslanmaz çeliği,

👉Isador Kisse sesli filmleri,

👉Emile Berliner telefon mikrofonunu,

👉Charles Ginsburg ilk bantlı video kayıt makinesini geliştirdi.

👉Stanley Mezor ilk mikro işlem çipini icat etti.

👉Leo Szilard ilk nükleer zincirleme reaktörünü geliştirdi.

Peki, ama;

~Son 100 Yıl içinde Yahudiler sadece Bilimsel alanda 104 Nobel Ödülü kazanırken,

~1.4 milyar Müslüman neden yalnızca 3 Nobel kazandı

Yahudiler niçin bu kadar yaratıcı ve neden bu kadar güçlüler? Yahudi inancına bağlı ve küresel çapta büyüyüp tanınmış şu yatırımcılara ve işadamlarına ve markalarına bakalım;

* Ralph Lauren (Polo),

* Levi Strauss (Levi's Jeans),

* Howard Schultz (Starbuck's),

* Sergei Brin (Google),

* Michael Dell (Dell Bilgisayarları),

* Larry Ellison (Oracle),

* Donna Karan (DKNY),

* Irv Robbins (Baskins & Robbins),

* Bill Rosenberg (Dunkin Doughnuts)

* Richard Levin (Yale Üniversitesi'nin kurucu başkanı).

Yahudi inancına bağlı ve küresel çapta büyüyüp tanınmış şu sanatçılara bakalım:

* Michael Douglas,

* Dustin Hoffman,

* Harrison Ford,

* Woody Allen,

* Tony Curtis,

* Charles Bronson,

* Sandra Bullock,

* Billy Crystal,

* Paul Newman,

* Peter Sellers,

* George Burns,

* Goldie Hawn,

* Cary Grant,

* William Shatner,

* Jerry Lewis,* Peter Falk...

Yönetmenler ve Yapımcılar arasındaki Yahudiler:

* Steven Spielberg,

* Mel Brooks,

* Oliver Stone,

* Aaaron Spelling (Beverly Hills 90210),

* Neil Simon (The Odd Couple),

* Andrew Vaina (Rambo 1 /2 / 3),

* Michael Mann (Starzky and Hutch),

* Milos Forman (One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest, Amadeus),

* Douglas Fairbanks (TheThief of Baghdat),

* Ivan Reitman (Ghostbusters) ,

* Kohen Kardeşler,

* William Wyler.

* William James Sidis

Sorun kendinize;

250’lik IQ derecesiyle Dünyaya gelmiş en parlak insan hangi dine mensuptur?

Sorun kendinize;

Neden Yahudiler bu kadar güçlüdür?

Cevabı şudur;

Her çocuğa ve her gence kaliteli eğitim verirler...

Bu eğitim türü sorgulayıcı (teslimiyetçi değil), araştırıcı (ezberci değil) ve yaratıcıdır (bilgi üretmek/bulmak içindir)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

by Jordan Hoffman

In Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer, the decision of Cillian Murphy's J. Robert Oppenheimer to make the leap from theoretical physics to practical applications is a personal one. "It's not your people they're herding into camps," he says to Josh Hartnett's Ernest Lawrence. "It's mine."

Oppenheimer's Jewish background (and that of many of the brilliant people portrayed in the film, like Albert Einstein, Edward Teller, Isidor Isaac Rabi, Richard Feynman, Leo Szilard and others) is a key component in their determination to prevent the Nazis from being first to create an atomic bomb. You would not know this, however, if you saw the movie in Arabic.

As reported in The National, an English-language news outlet based in the United Arab Emirates, the Lebanon-based company that translated the film for the region has dodged the specific word for Jews and, instead, has opted to use word ghurabaa that translates as stranger or foreigner.

Egyptian film director Yousry Nasrallah criticized the decision, saying "The Arabic translation of the dialogue was strikingly poor. There is nothing to justify or explain the translation of Jew to ghareeb or ghurabaa. It is a shame."

An unnamed representative for the film told The National that this is not atypical for Middle Eastern censor boards. "There are topics we usually don't tackle, and that is one of them. We cannot use the word 'Jew', the direct translation in Arabic, otherwise it may be edited, or they ask us to remove it."

They continued, "In order to avoid that, so people can enjoy the movie without having so many cuts, we would just change the translation a little bit. This has been an ongoing workflow for the past 15 or 20 years." (In 2013, though a large section of the Brad Pitt action film World War Z was set in Israel, Turkish translations changed all references to simply "The Middle East.")

There are several moments in the film in which the impact is blunted by this censorship. Oppenheimer's foe, Lewis Strauss (played by Robert Downey Jr.), is also Jewish, and mentions it in the film — but then is particular about the Americanized way his name ought to be pronounced. When Oppenheimer meets Rabi, who is first to voice ethical concerns about the creation of the bomb, he refers to himself and Oppenheimer as "a couple of New York Jews," marking themselves as distinct from mainstream American culture. The National reports that the translation reads as "inhabitants of New York."

Oppenheimer has seen tremendous box office success both domestically and internationally, with a cumulative gross of $650 million — a remarkable achievement for a historical drama. Last week it became the highest-grossing World War II film of all time, has extended its 70mm IMAX run in several markets, and even surpassed Star Wars: The Force Awakens as the biggest earner at Hollywood's Chinese Theatre.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

question on the chase: in which european country were physicists edward teller, leo szilard and john von neumann born?

me: (gets so hard i get nauseous) yeah

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Oppenheimer is a movie devoted to two related stories – how, under the scientific direction of Robert Oppenheimer the US produced an atom bomb in time to be used against Japan at in the Second World War, and how after that achievement Oppenheimer, by now the Director of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton had his security clearance revoked and was removed from advising the US government on nuclear weapons work.

Australian (and British) viewers will benefit from knowing about the role which Mark Oliphant (then in Birmingham) played behind the scenes in getting the atomic project going.

The movie was exciting and kept you on the edge of your seat. One expects that movies distort or omit historical or scientific facts, in the effort to produce a good spectacle and a good story. As I was enjoying the story, and the spectacle, I found myself becoming more and more annoyed by these distortions and omissions.

The critical fact which was omitted was that the determination that an atomic bomb could be constructed in a small enough package to be delivered by air was made in Britain, and that information was provided to the US early in 1941, but initially the US did not act on it. Mark Oliphant late in 1941, forcefully reminded the US of those discoveries and work started. Without the British action it is unlikely that the atomic bomb would have been available before the Allied invasion of Japan.

The distortion which I found irritating was the prominence given to the 1939 work of Oppenheimer, with his PhD student H. Snyder on black holes. This paper had no impact on the work on the production of the atom bomb. Perhaps it was introduced into the movie to provide an excuse for the endless and irrelevant images of stars and galaxies. Artistic licence – yes, but very annoying to me.

When the process of nuclear fission was discovered in 1938 in Germany and elucidated and explained in Europe and the US in 1939, the possibility of a nuclear fission bomb was obvious to many physicists. It was not immediately apparent what the dimensions of such a bomb would be, whether it could be readily delivered by air or not. The famous 1941 letter (composed by Szilard) from Einstein to President Roosevelt was not able to hint at the answer, and the Uranium Commission set up by the President to investigate concentrated its activity on the possible use of nuclear reactors to power submarines.

The breakthrough was made by Rudolf Peierls and Otto Frisch, two Jewish refugees working at the Department of Physics at the University of Birmingham. Mark Oliphant, the Head of the Physics Department had arranged jobs for them. Oliphant had a large group working on radar. That work was secret and Peierls and Frisch, being German aliens were not allowed to join the secret war work. Instead, they worked together on the calculation of how large a Uranium bomb would be, and what effects it would have. Peierls hand typed the now famous Peierls Frisch Memorandum and handed it to Oliphant. The now unclassified memorandum is available from several sources, one of which points out they make an error and instead of their estimate that 600 gram of uranium 235 would make a bomb, the correct estimate is 18 Kg.

Oliphant passed the memorandum to those responsible for considering the likely use of Uranium in the war, and the MAUD committee was set up to verify and work through the implications of the Peierls Frisch memorandum. The report is now unclassified and is available here. They recognised that the Atomic Bomb was feasible with Uranium in which the Uranium 235 isotope was enriched, but that the resources required for program were far beyond what the British could afford. Although the US was not yet in the war, the report of the MAUD committee was shared with the US early in 1941, but no response had been received.

Oliphant flew to the United States in late August 1941 in an unheated bomber to ostensibly consult about the radar program but was actually charged with inquiring why the United States was ignoring the MAUD Committee’s findings. Oliphant stated the following: “The minutes and reports had been sent to Lyman Briggs (Director of the Uranium Committee) and we were puzzled to receive virtually no comment. I called on Briggs in Washington, only to find out that this inarticulate and unimpressive man had put the reports in his safe and had not shown them to members of his committee. I was amazed and distressed.”

Oliphant then met with the Uranium Committee. Samuel K. Allison was a new committee member, a talented experimentalist and a protégé of Arthur Compton at the University of Chicago. Oliphant “came to a meeting,” Allison recalls, “and said ‘bomb’ in no uncertain terms. He told us we must concentrate every effort on the bomb and said we had no right to work on power plants or anything but the bomb. The bomb would cost 25 million dollars, he said, and Britain didn’t have the money or the manpower, so it was up to us.” Allison was surprised that Briggs had kept the committee in the dark.

To further champion his cause, Oliphant contacted Ernest O. Lawrence at the University of California at Berkeley. After visiting with Lawrence and receiving his support, Oliphant visited with both James B. Conant and Vannevar Bush and then went to see Enrico Fermi before returning to Birmingham, England.

Oliphant’s heroic efforts are generally felt to be the “catalyst” that finally pushed the American bomb effort over the top.

As described in Wizards of Oz {Bret Mason 2022, New South Publishing, Sydney ISBN 9781742237459}, the visit to Lawrence, who had been a colleague of Oliphant at Cambridge was prompted by Oliphant’s frustration with the lack of action by the Uranium Committee and the apparent lack of understanding by Conant and Bush that a bomb was possible. Note that the visits were not in the order described in the official US history quoted above. Oliphant was not authorised to visit Lawrence, who did not have the necessary security clearance, but Oliphant flew to Berkeley. Oliphant described the work of the Maud Committee in detail, persuading Lawrence that the atomic bomb could and must be built, by the US. Oppenheimer joined them during the conversation. Oliphant wrote detailed letters to both Oppenheimer and Lawrence. All were concerned about the lack of action in the US and the need for speed because the basic physics behind the atom bomb had been developed before the war in Germany.

Histories differ on the extent to which Oliphant’s intervention speeded up the production of the Bomb, and whether or not it would have been ready to use before the invasion of Japan. In general US histories suggest that, although speeded up it was not enough to change the outcome of the war, and British histories suggest that it was critical. The October 1945 issue of Reviews of Modern Physics contains the US and British histories, work it out for yourself. Groves said that “without active and continuing British interest there would probably been no atomic bomb to drop on Hiroshima” but downplayed their scientific input. As the US repeated the British scientific work and developed the plutonium bomb in spite of that route being put on the shelf by the MAUD committee, that can be understood. Left open is the question of when it would have been started without the British input, and Oliphant’s push.

“If Congress knew the true history of the atomic energy project, I have no doubt that it would create a special medal to be given to meddling foreigners for distinguished services, and Dr. [Mark] Oliphant would be the first to receive one.” – Leo Szilard; speaking after the war and referring to Britain’s “manipulation” of America’s government officials to put the bomb effort on a “fast track.” From the US Nuclear Museum of Science and History.

The US Congress did establish such a medal, the Medal of Freedom, and it was received by Peierls and Frisch in 1947, but not Oliphant. He was to be the only meddling foreigner to be awarded the Medal of Freedom with Gold Palm, but he had been described as an “Australian Citizen” and the award was referred to the Australian Government for approval, which had decided that such awards should not be awarded to civilians and did not approve. In 1947 there were no Australian Citizens. Australians were a British Subjects. Had he been correctly described he would have received the medal. [Wizards of Oz p 322]

Australian and British viewers of the movie Oppenheimer should be aware British Science and Mark Oliphant’s personal persuasion made a vital part in the timely production of atomic bomb in 1945.'

#Oppenheimer#Medal of Freedom#Ernest Lawrence#Mark Oliphant#Institute for Advanced Study#Princeton#Leo Szilard#Albert Einstein#President Roosevelt#H. Snyder#Rudolf Peierls#Otto Frisch#Lyman Briggs#Arthur Compton#Vannevar Bush#James B. Conant#Enrico Fermi

0 notes

Text

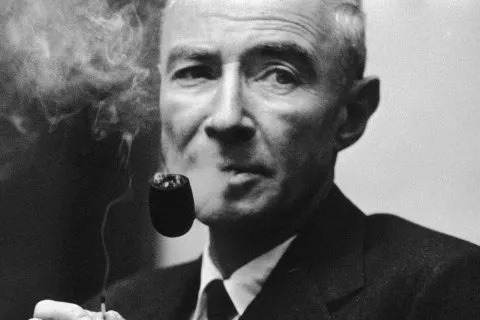

Why Robert Oppenheimer's Atomic Bomb Still Haunts Us

— By Richard Rhodes | Published May 15, 2013

Oppenheimer spearheaded the creation of the atom bomb. René Burri/Magnum

Robert Oppenheimer oversaw the design and construction of the first atomic bombs. The American theoretical physicist wasn't the only one involved—more than 130,000 people contributed their skills to the World War II Manhattan Project, from construction workers to explosives experts to Soviet spies—but his name survives uniquely in popular memory as the names of the other participants fade. British philosopher Ray Monk's lengthy new biography of the man is only the most recent of several to appear, and Oppenheimer wins significant assessment in every history of the Manhattan Project, including my own. Why this one man should have come to stand for the whole huge business, then, is the essential question any biographer must answer.

It's not as if the bomb program were bereft of men of distinction. Gen. Leslie Groves built the Pentagon and thousands of other U.S. military installations before leading the entire Manhattan Project to success in record time. Hans Bethe discovered the sequence of thermonuclear reactions that fire the stars. Leo Szilard and Enrico Fermi invented the nuclear reactor. John von Neumann conceived the stored-program digital computer. Edward Teller and Stanislaw Ulam co-invented the hydrogen bomb. Luis Alvarez devised a whole new technology for detonating explosives to make the Fat Man bomb work, and later, with his son, Walter, proved that an Earth-impacting asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. The list goes on. What was so special about Oppenheimer?

He was brilliant, rich, handsome, charismatic. Women adored him. As a young professor at Berkeley and Caltech in the 1930s, he broke the European monopoly on theoretical physics, contributing significantly to making America a physics powerhouse that continues to win a freight of Nobel Prizes. Despite never having directed any organization before, he led the Los Alamos bomb laboratory with such skill that even his worst enemy, Edward Teller, told me once that Oppenheimer was the best lab director he'd ever known. After the war he led the group of scientists who guided American nuclear policy, the General Advisory Committee to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He finished out his life as director of the prestigious Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where he welcomed young scientists and scholars into that traditionally aloof club.

August 9, 1945: Nagasaki is hit by an atom bomb. Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum/EPA

Those were exceptional achievements, but they don't by themselves explain his unique place in nuclear history. For that, add in the dark side. His brilliance came with a casual cruelty, born certainly of insecurity, which lashed out with invective against anyone who said anything he considered stupid; even the brilliant Bethe wasn't exempt. His relationships with the significant women in his life were destructive: his first deep love, Jean Tatlock, the daughter of a Berkeley professor, was a suicide; his wife, Kitty, a lifelong alcoholic. His daughter committed suicide; his son continues to live an isolated life.

His Choices or Mistakes, Combined with his Penchant for Humiliating Lesser Men, Eventually Destroyed Him.

Oppenheimer's achievements as a theoretical physicist never reached the level his brilliance seemed to promise; the reason, his student and later Nobel laureate Julian Schwinger judged, was that he "very much insisted on displaying that he was on top of everything"—a polite way of saying Oppenheimer was glib. The physicist Isidor Rabi, a Nobel laureate colleague whom Oppenheimer deeply respected, thought he attributed too much mystery to the workings of nature. Monk notes his curiously uncritical respect for the received wisdom of his field.

Monk's discussion of Oppenheimer's work in physics is one of his book's great contributions to the saga, an area of the man's life that previous biographies have neglected. In the late 1920s Oppenheimer first worked out the physics of what came to be called black holes, those collapsing giant stars that pull even light in behind them as they shrink to solar-system or even planetary size. Some have speculated Oppenheimer might have won a Nobel for that work had he lived to see the first black hole identified in 1971.

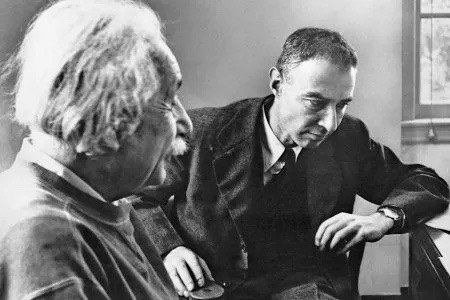

Oppenheimer with Albert Einstein, circa the 1940s. Corbis

Oppenheimer's patriotism should have been evident to even the most obtuse government critic. He gave up his beloved physics, after all, not to mention any vestige of personal privacy, to help make his country invulnerable with atomic bombs. Yet he risked his work and reputation by dabbling in left-wing and communist politics before the war and lying to security officers during the war about a solicitation to espionage he received. His choices or mistakes, combined with his penchant for humiliating lesser men, eventually destroyed him.

One of those lesser men, a vicious piece of work named Lewis Strauss, a former shoe salesman turned Wall Street financier and physicist manqué, was the vehicle of Oppenheimer's destruction. When President Eisenhower appointed Strauss to the chairmanship of the AEC in the summer of 1953, Strauss pieced together a case against Oppenheimer. He was still splenetic from an extended Oppenheimer drubbing delivered during a congressional hearing all the way back in 1948, and he believed the physicist was a Soviet spy.

Strauss proceeded to revoke Oppenheimer's security clearance, effectively shutting him out of government. Oppenheimer could have accepted his fate and returned to an academic life filled with honors; he was due to be dropped as an AEC consultant anyway. He chose instead to fight the charges. Strauss found a brutal prosecuting attorney to question the scientist, bugged his communications with his attorney, and stalled giving the attorney the clearances he needed to vet the charges. The transcript of the hearing In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer is one of the great, dark documents of the early atomic age, almost Shakespearean in its craven parade of hostile witnesses through the government star chamber, with the victim himself, catatonic with shame, sunken on a couch incessantly smoking the cigarettes that would kill him with throat cancer at 63 in 1967.

Rabi was one of the few witnesses who stood up for his friend, finally challenging the hearing board in exasperation, "We have an A-bomb and a whole series of it [because of Oppenheimer's work], and what more do you want, mermaids?" What Strauss and others, particularly Edward Teller, wanted was Oppenheimer's head on a platter, and they got it. The public humiliation, which he called "my train wreck," destroyed him. Those who knew him best have told me sadly that he was never the same again.

For Monk as for Rabi, Oppenheimer's central problem was his hollow core, his false sense of self, which Rabi with characteristic wit framed as an inability to decide whether he wanted to be president of the Knights of Columbus or B'nai B'rith. The German Jews who were Oppenheimer's 19th-century forebears had worked hard at assimilation—that is, at denying their religious heritage. Oppenheimer's parents submerged that heritage further in New York's ethical-culture movement that salvaged the humanism of Judaism while scrapping the supernatural overburden. Oppenheimer, actor that he was, could fit himself to almost any role, but turned either abject or imperious when threatened. He was a great lab director at Los Alamos because of his intelligence—"He was much smarter than the rest of us," Bethe told me—because of his broad knowledge and culture; because of his psychological insight into the complicated personalities of the gifted men assembled there to work on the bomb; most of all because he decided to play that role, as a patriotic citizen, and played it superbly.

Monk is a levelheaded and congenial guide to Oppenheimer's life, his biography certainly the best that has yet come along. But he devotes far too many pages to Oppenheimer's Depression-era flirtation with communism, a dead letter long ago and one that speaks more of a rich esthete's awakening to the suffering in the world than to Oppenheimer's political convictions. He doesn't always get the science right. Most of the errors are trivial, but a few are important to the story.

Their Fundamental Objection Was to Giving up Production of Real Weapons so That Teller Could Pursue His Pipe Dream, a Dead-end Hydrogen Bomb Design.

A fundamental reason Oppenheimer opposed a crash program to develop the hydrogen bomb in response to the first Soviet atomic-bomb test in 1949 was the requirement of Edward Teller's "Super" design for large amounts of a rare isotope of hydrogen, tritium. Tritium is bred by irradiating lithium in a nuclear reactor, but the slugs of lithium take up space that would otherwise be devoted to breeding plutonium. To make tritium for a hydrogen bomb that the U.S. did not know how to build would have required sacrificing most of the U.S. production of plutonium for devastating atomic bombs the U.S. did know how to build. To Oppenheimer and the other scientists on the GAC, such an irresponsible substitution as an answer to the Soviet bomb made no strategic sense. It's true that the hydrogen bomb with its potentially unlimited scale of destruction made no military sense to them either—and was morally repugnant to some of them as well. But their fundamental objection, which Monk overlooks, was to giving up production of real weapons so that Teller could pursue his pipe dream, a dead-end hydrogen bomb design that never worked.

Julius Robert Oppenheimer (April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967)

More egregious is Monk's notion that the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, Oppenheimer's mentor during the war on the international implications of the new technology, pushed for the bomb's use on Japan to make its terror manifest. He did not. He pushed, to the contrary, for the Allies, the Soviet Union included, to discuss the implications of the bomb prior to its use and to devise a framework for controlling it. Bohr foresaw that the bomb would stalemate major war, as it has, but correctly feared that U.S. secrecy about its development would lead to a U.S.-Soviet arms race. He conferred with both Roosevelt and Churchill about presenting the fact of the bomb to the Russians as a common danger to the world, like a new epidemic disease, that needed to be quarantined by common agreement. Churchill vehemently disagreed, and Roosevelt was old and ill. The moment passed. The arms race followed, as Bohr foresaw, and with diminished force, among pariah states like Iran and North Korea, continues to this day.

Monk's Oppenheimer is a less appealing figure than the Oppenheimer of previous biographies, perhaps because, as an Englishman, Monk is less susceptible to Oppenheimer's rhetorical gifts and more candid about calling out his evasions. He pulls together most of what several generations of Oppenheimer scholars have found and offers new revelations as well. Yet there's a faint whiff of condescension in his portrait, and the real Oppenheimer, the man whom so many loved and admired, still somehow escapes him. He misses the deep alignment of Robert Oppenheimer's life with Greek tragedy, the charismatic hubris that was his glory but also the flaw that brought him low. But maybe I'm expecting too much: maybe only a large work of fiction could assemble that critical mass.

#Robert Oppenheimer#Atomic Bomb#Richard Rhodes#World War II#Manhattan Project#Ray Monk#Gen. Leslie Groves#Pentagon#Hydrogen Bomb#Edward Teller | Stanislaw Ulam#Nobel Prize#Princeton University#Albert Einstein#President Eisenhower#Lewis Strauss#Hydrogen | Tritium | Plutonium#Roosevelt | Churchill#US — Soviet Union

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Making of the Atomic Bomb details Leo Szilard's catty attempts to wrest control over atomic energy from the military during the Manhattan Project and then Vannevar Bush's similarly catty attempts to shut him down. In typical academic/scientist/policy advisor/bureaucrat/eminence grise fashion, the language they use is always polite and legalistic, even with the trappings of unimpeachable charity and patience, but if you can read between the lines at all, you can see where the dagger is being twisted. If you don't know what this looks like, I recommend watching Yes Minister.

It reminds me of something I noticed at an NSF-funded summer school for PhD students: that becoming a successful academic seems to depend on coming from a culture that has at least a dozen polite ways of saying, "go fuck yourself."

9 notes

·

View notes