#philippe lebas

Text

Frev Friendships — Saint-Just and Robespierre

You who supports the tottering fatherland against the torrent of despotism and intrigue, you whom I only know, like God, through his miracles; I speak to you, monsieur, to ask you to unite with me in order to save my sad fatherland. The city of Gouci has relocated (this rumour goes around here) the free markets from the town of Blérancourt. Why do the cities devour the privileges of the countryside? Will there remain no more of them to the latter than size and taxes? Support, please, with all your talent, an address that I make for the same letter, in which I request the reunion of my heritage with the national areas of the canton, so that one lets to my country a privilege without which it has to die of hunger. I do not know you, but you are a great man. You are not only the deputy of a province, you are one of humanity and of the Republic. Please, make it that my request be not despised. I have the honour to be, monsieur, your most humble, most obedient servant.

Saint-Just, constituent of the department of Aisne.

To Monsieur de Robespierre in the National Assembly in Paris.

Blérancourt, near Noyon, August 19, 1790.

Saint-Just’s first letter ever written to Robespierre, dated August 19 1790

Citizens, you are aware that, to dispel the errors with which Roland has covered the entire Republic, the Society has decided that it will have Robespierre's speech printed and distributed. We viewed it as an eternal lesson for the French people, as a sure way of unmasking the Brissotin faction and of opening the eyes of the French to the virtues too long unknown of the minority that sits with the Mountain. I remind you that a subscription office is open at the secretariat. It is enough for me to point it out to you to excite your patriotic zeal, and, by imitating the patriots who each deposited fifty écus to have Robespierre's excellent speech printed, you will have done well for the fatherland.

Saint-Just at the Jacobins, January 1 1793

Patriots with more or less talent […] Jacquier, Saint-Just’s brother-in-law.

Robespierre in a private list, written sometime during his time on the Committee of Public Safety

Saint-Just doesn’t have time to write to you. He gives you his compliments.

Lebas in a letter to Robespierre October 25 1793

Trust no longer has a price when we share it with corrupt men, then we do our duty out of love for our fatherland alone, and this feeling is purer. I embrace you, my friend.

Saint-Just.

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a post-scriptum note added to a letter written by Lebas to Robespierre, November 5 1793. Saint-Just uses tutoiement with Robespierre here, while Lebas used vouvoiement.

We have made too many laws and too few examples: you punish but the salient crimes, the hypocritical crimes go unpunished. Punish a slight abuse in each part, it is the way to frighten the wicked, and to make them see that the government has its eye on everything. No sooner do we turn our backs than the aristocracy rises in the tone of the day, and commits evils under the colors of liberty.

Engage the committee to give much pomp to the punishment of all faults in government. Before a month has passed you will have illuminated this maze in which counter-revolution and revolution march haphazardly. Call, my friend, the attention of the Jacobin Club to the strong maxims of the public good; let it concern itself with the great means of governing a free state. I invite you to take measures to find out if all the manufactures and factories of France are in activity, and to favor them, because our troops would within a year find themselves without clothes; manufacturers are not patriots, they do not want to work, they must be forced to do so, and not let down any useful establishment. We will do our best here. I embrace you and our mutual friends.

Saint-Just

To Robespierre the older.

Saint-Just in a letter to Robespierre, December 14 1793

Paris, 9 nivôse, year 2 of the Republic.

Friends.

I feared, in the midst of our successes, and on the eve of a decisive victory, the disastrous consequences of a misunderstanding or of a ridiculous intrigue. Your principles and your virtues reassured me. I have supported them as much as I could. The letter that the Committee of Public Safety sent you at the same time as mine will tell you the rest. I embrace you with all my soul.

Robespierre.

Robespierre in a letter to Saint-Just and Lebas, December 29 1793

Why should I not say that this (the dantonist purge) was a meditated assassination, prepared for a long time, when two days after this session where the crime was taking place, the representative Vadier told me that Saint-Just, through his stubbornness, had almost caused the downfall of the members of the two committees, because he had wanted that the accused to be present when he read the report at the National Convention; and such was his obstinacy that, seeing our formal opposition, he threw his hat into the fire in rage, and left us there. Robespierre was also of this opinion; he believed that by having these deputies arrested beforehand, this approach would sooner or later be reprehensible; but, as fear was an irresistible argument with him, I used this weapon to fight him: You can take the chance of being guillotined, if that is what you want; For my part, I want to avoid this danger by having them arrested immediately, because we must not have any illusions about the course we must take; everything is reduced to these bits: If we do not have them guillotined, we will be that ourselves.

À Maximilien Robespierre aux enfers (1794) by Taschereau de Fargues and Paul-Auguste-Jacques. Robespierre and Saint-Just had also worked out the dantonists’ indictment together.

…As far from the insensibility of your Saint-Just as from his base jealousies, [Camille] recoiled in front if the idea of accusing a college comrade, a companion in arms. […] Robespierre, can you really complete the fatal projects which the vile souls that surround you no doubt have inspired you to? […] Had I been Saint-Just’s wife I would tell him this: the sake of Camille is yours, it’s the sake of all the friends of Robespierre!

Lucile Desmoulins in an unsent letter to Robespierre, written somewhere between March 31 and April 4 1794. Lucile seems to have believed it was Saint-Just’s ”bad influence” in particular that got Robespierre to abandon Camille.

In the beginning of floréal (somewhere between April 20 and 30) during an evening session (at the Committee of Public Safety), a brusque fight erupted between Saint-Just and Carnot, on the subject of the administration of portable weapons, of which it wasn’t Carnot, but Prieur de la Côte-d’Or, who was in charge. Saint-Just put big interest in the brother-in-law of Sijas, Luxembourg workshop accounting officer, that one thought had been oppressed and threatened with arbitrary arrest, because he had experienced some difficulties for the purpose of his service with the weapon administration. In this quarrel caused unexpectedly by Saint-Just, one saw clearly his goal, which was to attack the members of the committee who occupied themselves with arms, and to lose their cooperateurs. He also tried to include our collegue Prieur in the inculpation, by accusing him of wanting to lose and imprison this agent. But Prieur denied these malicious claims so well, that Saint-Just didn’t dare to insist on it more. Instead, he turned again towards Carnot, whom he attacked with cruelty; several members of the Committee of General Security assisted. Niou was present for this scandalous scene: dismayed, he retired and feared to accept a pouder mission, a mission that could become, he said, a subject of accusation, since the patriots were busy destroying themselves in this way. We undoubtedly complained about this indecent attack, but was it necessary, at a time when there was not a grain of powder manufactured in Paris, to proclaim a division within the Committee of Public Safety, rather than to make known this fatal secret? In the midst of the most vague indictments and the most atrocious expressions uttered by Saint-Just, Carnot was obliged to repel them by treating him and his friends as aspiring to dictatorship and successively attacking all patriots to remain alone and gain supreme power with his supporters. It was then that Saint-Just showed an excessive fury; he cried out that the Republic was lost if the men in charge of defending it were treated like dictators; that yesterday he saw the project to attack him but that he defended himself. ”It’s you,” he added, ”who is allied with the enemies of the patriots. And understand that I only need a few lines to write for an act of accusation and have you guillotined in two days.”

”I invite you, said Carnot with the firmness that only appartient to virtue: I provoke all your severity against me, I do not fear you, you are ridiculous dictators.” The other members of the Committee insisted in vain several times to extinguish this ferment of disorder in the committee, to remind Saint-Just of the fairer ideas of his colleague and of more decency in the committee; they wanted to call people back to public affairs, but everything was useless: Saint-Just went out as if enraged, flying into a rage and threatening his colleagues. Saint-Just probably had nothing more urgent than to go and warn Robespierre the next day of the scene that had just happened, because we saw them return together the next day to the committee, around one o'clock: barely had they entered when Saint-Just, taking Robespierre by the hand, addressed Carnot saying: ”Well, here you have my friends, here are the ones you attacked yesterday!” Robespierre tried to speak of the respective wrongs with a very hypocritical tone: Saint-Just wanted to speak again and excite his colleagues to take his side. The coldness which reigned in this session, disheartened them, and they left the committee very early and in a good mood.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûreté générale (Barère, Collot, Billaud, Vadier), aux imputations renouvellées contre eux, par Laurent Lecointre et declarées calomnieuses par décret du 13 fructidor dernier; à la Convention Nationale (1795), page 103-105

My friends, the committee has taken all the measures within its control at this time to support your zeal. It has asked me to write to you to explain the reasons for some of its provisions. It believed that the main cause of the last failure was the shortage of skilled generals, it will send you all the patriotic and educated soldiers that can be found. It thought it necessary at this time to re-use Stetenhofen, whom it is sending to you, because he has military merit, and because the objections made against him seem at least to be balanced by proofs of loyalty. He also relies on your wisdom and your energy. Salut et amitié.

Paris, 15 floréal, year 2 of the Republic.

Robespierre.

Robespierre to Saint-Just and Lebas, May 4 1793

Dear collegue,

Liberty is exposed to new dangers; the factions arise with a character more alarming than ever. The lines to get butter are more numerous and more turbulent than ever when they have the least pretexts, an insurrection in the prisons which was to break out yesterday and the intrigues which manifested themselves in the time of Hébert are combined with assassination attemps on several occasions against members of the Committee of Public Safety; the remnants of the factions, or rather the factions still alive, are redoubled in audacity and perfidy. There is fear of an aristocratic uprising, fatal to liberty. The greatest peril that threatens it is in Paris. The Committee needs to bring together the lights and energy of all its members. Calculate whether the army of the North, which you have powerfully contributed to putting on the path to victory, can do without your presence for a few days. We will replace you, until you return, with a patriotic representative.

The members composing the Committee of Public Safety.

Robespierre, Prieur, Carnot, Billaud-Varennes, Barère.

Letter to Saint-Just from the CPS, May 25 1794, written by Robespierre. It was penned down just two days after the alleged attempt on Robespierre’s life by Cécile Renault.

Robespierre returned to the Committee a few days later to denounce new conspiracies in the Convention, saying that, within a short time, these conspirators who had lined up and frequently dined together would succeed in destroying public liberty, if their maneuvers were allowed to continue unpunished. The committee refused to take any further measures, citing the necessity of not weakening and attacking the Convention, which was the target of all the enemies of the Republic. Robespierre did not lose sight of his project: he only saw conspiracies and plots: he asked that Saint-Just returned from the Army of the North and that one write to him so that he may come and strengthen the committee. Having arrived, Saint-Just asked Robespierre one day the purpose of his return in the presence of the other members of the Committee; Robespierre told him that he was to make a report on the new factions which threatened to destroy the National Convention; Robespierre was the only speaker during this session. He was met by the deepest silence from the Committee, and he leaves with horrible anger. Soon after, Saint-Just returned to the Army of the North, since called Sambre-et-Mouse. Some time passes; Robespierre calls for Saint-Just to return in vain: finally, he returns, no doubt after his instigations; he returned at the moment when he was most needed by the army and when he was least expected: he returned the day after the battle of Fleurus. From that moment, it was no longer possible to get him to leave, although Gillet, representative of the people to the army, continued to ask for him.

Réponse de Barère, Billaud-Varennes, Collot d’Herbois et Vadier aux imputations de Laurent Lecointre (1795)

On 10 messidor (June 28) I was at the Committee of Public Safety. There, I witnessed those who one accuses today (Billaud-Varenne, Barère, Collot-d'Herbois, Vadier, Vouland, Amar and David) treat Robespierre like a dictator. Robespierre flew into an incredible fury. The other members of the Committee looked on with contempt. Saint-Just went out with him.

Levasseur at the Convention, August 30 1794. If this scene actually took place, it must have done so one day later, 11 messidor (June 29), considering Saint-Just was still away on a mission on the tenth.

Isn’t it around the same time (a few days before thermidor) that Saint-Just and Lebas would dine at your father’s house with Robespierre?

Lebas often dined there, having married one of my sisters. Saint-Just rarely there, but he frequently went to Robespierre’s and climbed the stairs to his office without speaking to anyone.

During the dinner which I’m talking about, did you hear Saint-Just propose to Robespierre to reconcile with some members of the Convention and Committees who appeared to be opposed to him?

No. I only know that they appeared to be very devided.

Do you have any ideas what these divisions were about?

I only learned about it through the discussions which took place on this subject at the Jacobins and through the altercation which was said to have taken place at the Committee of Public Safety between Robespierre older and Carnot.

Robespierre’s host’s son Jacques-Maurice Duplay in an interrogation held January 1 1795

Saint-Just then fell back on his report, and said that he would join the committee the next day (9 thermidor) and that if it did not approve it, he would not read it. Collot continued to unmask Saint-Just; but as he focused more on depicting the dangers praying on the fatherland than on attacking the perfesy of Saint-Just and his accomplices, he gradually reassured himself of his confusion; he listened with composure, returning to his honeyed and hypocritical tone. Some time later, he told Collot d'Herbois that he could be reproached for having made some remarks against Robespierre in a café, and establishing this assertion as a positive fact, he admitted that he had made it the basis of an indictment against Collot, in the speech he had prepared.

Réponse des membres des deux anciens Comités de salut public et de sûrété générale… (1795) page 107.

I attest that Robespierre declared himself a firm supporter of the Convention and never spoke but gently in the Committee so as not to undermine any of its members. […] Billaud-Varenne said to Robespierre, “We are your friends, we have always walked together.” This dishonesty made my heart shudder. The next day, he called him Peisistratos and had written his act of accusation. […] If you reflect carefully on what happened during your last session, you will find the application of everything I said: a man alienated from the Committee due to the bitterest treatments, when this Committee was, in fact, no longer made up of more than the two or three members present, justified himself before you; he did not explain himself clearly enough, to tell the truth, but his alienation and the bitterness in his soul can excuse him somewhat: he does not know why he is being persecuted, he knows nothing except his misfortune. He has been called a tyrant of opinion: here I must explain myself and shine light on a sophism that tends to proscribe merit. And what exclusive right do you have to opinion, you who find that it is a crime to touch souls? Do you find it wrong that a man should be tenderhearted? Are you thus from the court of Philip, you who make war on eloquence? A tyrant of opinion? Who is stopping you from competing for the esteem of the fatherland, you who find it so wrong that someone should captivate it? There is no despot in the world, save Richelieu, who would be insulted by the fame of a writer. Is it a more disinterested triumph? Cato is said to have chased from Rome the bad citizen who had called eloquence at the tribune of harangues, the tyrant of opinion. No one has the right to claim that; it gives itself to reason and its empire is not the in the power of governments. […] The member who spoke for a long time yesterday at this tribune did not seem to have distinguished clearly enough who he was accusing. He had no complaints and has not complained either about the Committees; because the Committees still seem to me to be dignified of your estime, and the misfortunes that I have spoken to you of were born of isolation and the extreme authority of several members left alone.

Saint-Just defending Robespierre in his last, undelivered speech, July 27 1794

One brings St. Just, Dumas and Payan, all of them shackled, they are escorted by policemen. They stay a good quarter of an hour standing in front of the door of the Committee’s room; one makes them sit down onto a windowsill; they have still not uttered a single word, pleasant people make the persons who surround these three men step aside, and say move back, let these gentlemen see their King sleep on a table, just like a man. Saint-Just moves his head in order to see Robespierre. Saint-Just’s figure appeared dejected and humiliated, his swollen eyes expressed chagrin.

Faits recueillis aux derniers instants de Robespierre et de sa saction, du 9 au 10 thermidor (1794) by anonymous.

The Committee of General Security was being spied on by Héron, D…, Lebas: Robespierre knew, through them, word for word, everything that was happening at said committee. This espionage gave rise to more intimate connections between Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre. The fierce and ambitious character of the latter gave him the idea of establishing the general police bureau, which, barely conceived, was immediately decreed.

Révélations puisées dans les cartons des comités de Salut public et de Sûreté générale ou mémoires (inédits) (1824) by Gabriel Jérôme Sénart.

Intimately linked with Robespierre, [Saint-Just] had become necessary to him, and he had made himself feared perhaps even more than he had desired to be loved. One never saw them divided in opinion, and if the personal ideas of one had to bow to those of the other, it is certain that Saint-Just never gave in. Robespierre had a bit of that vanity which comes from selfishness; Saint-Just was full of the pride that springs from well-established beliefs; without physical courage, and weak in body, to the point of fearing the whistling of bullets, he had the courage of reflection which makes one wait for certain death, so as not to sacrifice an idea.

Memoirs of René Levasseur (1829) volume 2, page 324-325.

Often [Robespierre] said to me that Camille was perhaps the one among all the key revolutionaries whom he liked best, after our younger brother and Saint-Just.

Mémoires de Charlotte Robespierre sur ses deux frères (1834) page 139.

After the month of March, 1794, Robespierre's conduct appeared to me to change. Saint-Just was to a great degree the cause of this, and this leader was too youthful ; he urged him into the vain and dangerous path of dictatorship which he haughtily proclaimed. From that time all confidences in the two committees were at an end, and the misfortunes that followed the division in the government became inevitable. […] We did not hide from [Robespierre] that Saint-Just, who was formed of more dictatorial stuff, would have ended by overturning him and occupying his place ; we knew too that he would have us guillotined because of our opposition to his plans; so we overthrew him.

Memoirs of Bertrand Barère (1896), volume 1, page 103-104.

About this time Robespierre felt his ambition growing, and he thought that the moment had come to employ his influence and take part in the government. He took steps with certain members of the committee and the Convention, asking them to show a desire that he, Robespierre, should become a member of the Committee of Public Safety. He told the Jacobins it would be useful to observe the work and conduct of the members of the committee, and he told the members of the Convention that there would be more harmony between the Convention and the committee if he entered it. Several deputies spoke to me about it, and the proposal was made to the committee by Couthon and Saint-Just. To ask was to obtain, for a refusal would have been a sort of accusation, and it was necessary to avoid any split during that winter which was inaugurated in such a sinister manner. The committee agreed to his admission, and Robespierre was proposed.

Ibid, volume 2, page 96-97

The continued victories of our fourteen armies were as a cloud of glory over our frontiers, hiding from allied Europe our internecine struggles, and that unhappy side of our national character which acts and reacts so deplorably as much on the whole population as on our nghts and our manners. The enthusiasm with which I announced these victories from the tnbune was so easily seen that Saint- Just and Robespierre, being in the committee at three in the morning, and learning of the taking of Namur and some other Belgian towns, insisted for the future that the letters alone of the generals should be read, without any comments which might exaggerate their contents. I saw at once at whom this reproach was directed, and I took up the gauntlet with the deasion of a man willing to once more merit the hatred of the enemies of our national glory, and the bravery of our armies. Then Samt-Just cried, “ I beg to move that Barère be no longer allowed to add froth to our victories.” […] While Saint-Just was reproving me, Robespierre supported the longsightedness of his friend… […] The next day my report on the taking of Namur was somewhat more carefully drawn up, and I alluded to the observation of my critics, who were envious of the power of public opinion in favour of our troops, then busied in saving the country. This phrase in my report was much commented on, although its meaning was only clear to those who had heard the debate in the committee on the previous evening “Sad are the tunes, sad is the period, when the recital of the triumphs and glories of the armies of the Repubhc is coldly hastened to in this place! Henceforth liberty will be no longer defended by the country, it will be handed over to its enemies!”This pronouncement was not of a nature to be forgiven by Saint-Just and Robespierre, so they determined to supplant me with regard to these reports. They forced that idiot Couthon to attend the Committee of Public Safety at eleven in the morning, before I got there Couthon asked for the letters of the generals that had come in during the night, and took his usual seat at the back of the hall, waiting until the assembly was sufficiently full for him to announce the victones. About one, Couthon, being paralysed and unable to stand up in the tribune, coldly read the news from the armies from his place. This time, no effect was produced in the Assembly, or upon the public. This attempt, authorised by Robespierre and Saint-Just, having missed fire completely, the committee signified its dissatisfaction at the innovation.

Ibid, volume 2, page 123-125

After his return from Fleurus, Saint-Just remained some time in Paris, although his mission as representative to the armies of the Sambre and Meuse and the Rhine and Moselle was unfinished. The campaign was only beginning, but he had several projects in hand, and he stayed in committee, or rather his office, where he was always absorbed and thoughtful. Robespierre, in speaking of him at the committee, said familiarly, as if speaking of an intimate friend: ”Saint-Just is silent and observant, but I have noticed, in his personality, he has a great likeness to Charles IX.” This did not flatter Saint-Just, who was a deeper and cleverer revolutionist than Robespierre. One day, when the former was angry about several legislative propositions or decrees that did not please him, Saint-Just said to him, “Be calm, it is the phlegmatic who govern.”

Ibid, volume 2, page 139

This tyrannical law was the work of Saint-Just Consult the Momteuv of the 22nd of Germinal, where it is reported with the explanation of his motives, and you will see that, if there had been no committee, SamtJust would have used his power with as much dictatorial fanaticism as did Manus, that great enemy of the Roman anstocracy. Robespierre’s fnend never forgave me for having dimmished the force of this blow. Whilst I was at the tnbune of the Convention, he came, with someone unknown, and perused my register of requisitions. He took down certain names, and some days after, towards midnight, Robespierre and Saint-Just entered the committee, where they did not usually come (for they worked in a private office, under pretext that their duties were completely private) A few moments after their entry Saint-Just complained of the abuse I had made of the requisitions, which had been granted, said he, in such profusion that the law of the 21st of Germinal had become null and void.

Ibid, volume 2, page 146

Robespierre, Saint-Just and Couthon were inseparable. The first two had a dark and duplicitous character; they pushed away with a kind of disdainful pride any familiarity or affectionate relationship with their colleagues. The third, a legless man with a pale appearance, affected good-nature, but was no less perfidious than the other two. All three of them had a cold heart, without pity, they interacted only with each other, holding mysterious meetings outside, having a large number of protégés and agents, impenetrable in their designs.

Révélations sur le Comité de salut public by Prieur-Duvernois

Robespierre, who had great confidence in Le Bas because he knew his wise and prudent character well, had chosen him to accompany Saint-Just, whose burning love of the fatherland sometimes led to too much severity, and who had a tendency to get carried away. […] [Saint-Just] also had friendship for me and came often enough to our house. […] Finally our providence, our good friend Robespierre, spoke to Saint-Just to engage him to let me depart with them, along with my sister-in-law Henriette. He consented, but with some conditions.

Memoirs of Élisabeth Lebas (1901)

Volume 8 — page 153. ”Saint-Just, his (Robespierre’s) only confident.” His only confident?

Élisabeth Lebas corrects a passage in Alphonse de Lamartine’s Histoire des Girondins (1847)

The Lamenths and Péthion in the early days, quite rarely Legendre, Merlin de Thionville and Fouché, often Taschereau, Desmoulins and Teault, always Lebas, Saint-Just, David, Couthon and Buonarotti.

Élisabeth Lebas regarding visitors to the Duplay’s during the revolution

—

When arriving in Paris in September 1792, Saint-Just first lived on No. 7 rue de Gaillon up until March 1794, and then on No. 3 rue de Caumartin (today’s No. 5) up until his death. Both those places were within a ten minute walking distance from Robespierre’s home on 398 Rue Saint-Honoré.

Saint-Just was away from Paris (and therefore Robespierre) on missions between March 9 to March 31, October 17 to December 4, December 10 to December 30, January 22 to February 13, April 30 to May 31 and June 10 to June 29.

#sj and max holding hands 🤗💓#robespierre#saint-just#maximilien robespierre#louis antoine de saint just#barère#élisabeth lebas#philippe lebas#frev#frev friendships#long post#saintspierre

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

Original picture

#french revolution#frev#frev memes#almost half of these people are not even from pas-de-calais#but still#so... let's start the list#gracchus babeuf#philippe le bas#philippe lebas#joseph le bon#joseph lebon#camille desmoulins#desmoulins#antoine quentin fouquier-tinville#fouquier-tinville#martial herman#augustin robespierre#charlotte robespierre#maximilien robespierre#robespierre#louis antoine saint just#saint just#saint-just

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

lebas and élisabeth

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

UN DÎNER AVEC JULES SIMON ET CHARLOTTE ROBESPIERRE

Here is (finally) the anecdote as recorded by Jules Simon, followed by the summary given by Lenôtre, and the interpretation Coutant makes of it from the latter. Also some of my annotations coming from the part of my thesis where I reproduced the anecdote. (It's all in French obviously so anyone feeling brave enough to translate to English is more than welcome!)

(Source: Jules Simon, Premières années, Paris, Flammarion, 1901, p. 181-187.)

[…] C’est par un universitaire que je fus vraiment introduit dans le monde républicain. M. Philippe Le Bas, mon professeur d’histoire à l’École normale, m’accueillit chez lui, et me fit accueillir dans quelques familles restées fidèles aux souvenirs de 1793[1].

C’était le fils du conventionnel Le Bas, ami et disciple de Robespierre. Il était fier de la renommée de son père. On raconte même qu’avant d’être membre de l’Institut, il se faisait annoncer dans les salons sous ce titre : « M. Philippe Le Bas, fils du conventionnel ». J’avais désiré voir de près des survivants de la Révolution : mon succès dépassait mes espérances, puisque je me trouvais d’emblée dans le monde de Robespierre. J’étais comme un jeune débutant qui aurait voulu goûter d’un vin généreux, et à qui on aurait versé abondamment de l’alcool. J’avais assez de fermeté pour m’accommoder à peu près des Girondins, mais je fus sur le point de perdre l’esprit en me trouvant au milieu des amis de Robespierre.

La veuve du conventionnel Le Bas qui accoucha quelques semaines après de celui qui devait être mon professeur, était une des filles du menuisier Duplay. Cette famille Duplay était devenue la famille de Robespierre. Il y demeurait ; il était, quand il mourut, fiancé de Mademoiselle Éléonore, la sœur de Mme Le Bas. La fiancée prit le deuil de Robespierre et le porta jusqu’à sa mort. Toute cette famille était étroitement unie, et le souvenir du grand mort ne contribuait pas peu à cette union. Le Comité de Salut Public, universellement condamné et maudit, avait encore quelques amis dans ce coin du monde ; et pour ces survivants, pour ces persistants, la famille Le Bas était l’objet d’un respect particulier.

Du reste, le menuisier Duplay avait donné à ses filles une éducation excellente. Ce menuisier était un entrepreneur en menuiserie ; il remplit pendant quelque temps les fonctions de juge au Tribunal révolutionnaire. Son petit-fils, celui qui fut mon maître à l’École normale, était l’homme le plus doux et le plus bienveillant du monde. Quand il n’avait plus à s’expliquer sur son père et les amis terribles de son père, il parlait et agissait en homme cultivé, ami de la paix, et préoccupé, par-dessus tout, de ses recherches d’érudition. Il avait été précepteur d’un prince. Il est vrai que ce prince était le prince Louis-Napoléon, celui-là même qui, contre toute attente, devint Empereur des Français. L’avènement de son élève au rang suprême ne changea rien ni aux idées de Philippe Le Bas, ni à sa conduite, ni à son langage, ni à sa vie. Il resta jusqu’à la fin tel que je l’avais connu en 1834, M. Philippe Le Bas, fils du Conventionnel.

On savait parmi les familiers de M. Le Bas, que je ne connaissais personne à Paris ; et c’était une raison pour eux de m’inviter à dîner ou à déjeuner le dimanche. Je fus invité une fois avec des formes solennelles et mystérieuses qui me donnèrent lieu de penser que j’allais assister à quelque événement d’importance. J’arrivai à l’heure dite. Il y avait quelques convives, tous républicains avérés et rédacteurs des journaux du parti. Près d’une heure s’écoula ; la personne qui avait donné lieu à la réunion se faisait attendre. Je pense que tout le monde, excepté moi, était dans le secret ; mais j’étais trop timide pour faire une question. Enfin un grand mouvement se produisit, la famille se porta tout entière dans l’antichambre pour rendre la réception plus solennelle, et nous nous rangeâmes autour de la porte, pendant qu’à côté de nous on échangeait des propos de bienvenue.

On n’annonçait pas dans cette modeste maison. Je vis entrer une femme âgée qui marchait péniblement et qui donnait le bras à la maîtresse de maison. Elle était venue seule. On la salua très profondément ; elle répondit à ce salut en reine qui veut être aimable pour ses sujets. C’était une femme très maigre, très droite dans sa petite taille, vêtue à l’antique avec une propreté toute puritaine. Elle portait le costume du Directoire, mais sans dentelles ni ornements. J’eus sur le champ, comme une intuition que je voyais la sœur de Robespierre. Elle se mit à table, où elle occupa naturellement la place d’honneur. Je ne cessai de l’observer pendant tout le repas. Elle me parut grave, triste, sans austérité cependant, un peu hautaine quoique polie, particulièrement bienveillante pour M. Le Bas, qui la comblait d’égards ou, pour mieux dire, de respect. Quand la conversation devint générale, elle y prit peu de part ; mais écouta tout avec politesse et attention. S’il lui arrivait de dire un mot, tout le monde se taisait à l’instant. Je me disais qu’on n’aurait pas mieux traité une souveraine.

Le nom de Robespierre ne fut pas même prononcé. Au fond, c’est à lui que tout le monde pensait, et c’est de lui qu’on parlait sans le nommer. C’était l’habitude dans ces familles dévouées. Je ne l’attribue à aucune appréhension de se compromettre en prononçant ce nom qui était là, révéré, et exécré partout ailleurs. On ne le prononçait pas, parce qu’il était sous-entendu dans tous les discours.

Il y a deux Robespierre : le Robespierre féroce et le Robespierre raisonneur et sentimental. Le culte de ses fanatiques s’adressait également au dictateur et à l’orateur humanitaire. Les revenants avec lesquels j’étais attablé n’appartenaient pas à 1834. Ils voulaient être, ils étaient de 1793. Les grandes tueries n’étaient pour eux que des actes nécessaires de gouvernement. À peine les Thermidoriens eurent-ils renversé le Comité de Salut Public qu’ils s’exercèrent à le copier. Au 18 Fructidor, La Réveillère-Lépeaux, le plus dur des hommes, déporta des Directeurs, des représentants et des journalistes à Sinnamari. Pendant un quart de siècle, la proscription fut dans les mœurs. Je crois bien qu’on excusait les tueries de 1793 autour de moi, que peut-être même on les glorifiait. Mais on pensait surtout au disciple de Jean-Jacques Rousseau, aux discours contre la peine de mort et sur l’Être suprême, à l’auteur de tant d’homélies attendrissantes sur la fraternité et la vertu. Je suis sûr que Charlotte le revoyait dans ses rêves, précédant la Convention à l’autel, le jour de la fête religieuse, en habit bleu clair et en cravate blanche, et portant dans ses bras une gerbe de fleurs.

Melle Robespierre avait soixante-quatorze ans lorsque je la vis. Je savais qu’elle avait passionnément aimé ses deux frères et que, quand Maximilien s’était installé chez les Duplay, elle s’était montrée irritée et jalouse. Elle faisait à ces nouveaux amis un crime de leur amitié. Elle allait jusqu’à prétendre qu’Éléonore avait employé la ruse pour se faire épouser. Elle vécut loin d’eux après la catastrophe. Le Premier Consul lui fit une pension de 3.600 livres, qui fut plus tard réduite de plus de moitié, mais qu’elle toucha presque sans interruption jusqu’à sa mort. Elle vivait de cette faible ressource dans un isolement absolu. Elle publia des Mémoires qui roulaient sur des événements connus, et ne piquèrent point la curiosité. Je suppose qu’elle consentit à laisser faire cette publication dans un moment de détresse[2]. Sans doute, elle avait voulu, aux approches de la mort, oublier son ancienne rancune. Elle s’était souvenue avec attendrissement d’une femme vénérable qui avait failli être la sœur de son frère. Elle avait voulu se rapprocher un moment de cet homme déjà célèbre, dont le père avait été le plus fidèle ami de Maximilien. Elle sentit enfin que ceux qui s’étaient rencontrés dans ces jours lugubres devaient être réunis dans le souvenir comme ils l’avaient été dans la vie.

Je croyais rêver et je rêvais en effet. Les deux femmes qui étaient là, quel que fut leur nom, avaient vécu dans l’intimité de Robespierre, écouté sa parole comme celle d’un pontife, admiré sa vie comme celle d’un héros et d’un sage. Les questions se pressaient en tumulte dans mon esprit, et je me demandais avec effroi si j’oserais interroger mon maître et si je ne me laisserais pas opprimer une fois de plus par ma maudite timidité.

Il me conduisit jusqu’à la porte pour me dire d’un air triomphant : « Comment la trouvez-vous ? » Je m’enfuis et je me dis tout en courant à travers les rues de Paris, que je n’étais pas à ma place dans ce monde-là. Tout, dans ce temple, était respectable, excepté le Dieu. J’eus le souvenir de mes morts et, en même temps, de ma haine[3].

Version rapportée par G. Lenôtre :

Un jour, écrivait-il, il y a quelques années dans un de ses articles du Temps, un jour que je déjeunais chez mon professeur d’histoire, M. Philippe Lebas, je vis entrer dans le salon une vieille demoiselle, bien conservée, se tenant très droite, vêtue, à peu près comme sous le Directoire, sans aucun luxe, mais d’une propreté recherchée. Mme Lebas, la mère (autrefois Mlle Duplay) et M. Lebas l’entouraient de respects, la traitaient presque en souveraine. Elle parla peu pendant le repas, poliment, avec gravité. « Comment la trouvez-vous ? me dit M. Lebas quand nous fûmes seuls dans son cabinet – Mais qui est-ce ? – Comment ? Je ne vous l’avais pas dit ? C’est la sœur de Robespierre. » J’étais alors élève de première année à l’École normale.

(Source : G. Lenôtre, Paris révolutionnaire, Firmin-Didot, Paris, 1895. p. 48.)

Version rapportée par Paul Coutant :

Charlotte Robespierre a davantage occupé l’opinion. M. Lenôtre, dans son dernier volume[4], lui a consacré tout un chapitre, et le fils du conventionnel Le Bas a tracé sa biographie, en quelques lignes qui détruisent, par leur sévérité, la portée d’une historiette racontée jadis par Jules Simon dans le Temps :

« Un jour que je déjeunais chez mon professeur d’histoire, M. Philippe Le Bas – dit Jules Simon – je vis entrer dans le salon une vieille demoiselle, bien conservée, se tenant très droite, vêtue, à peu près, comme sous le Directoire, sans aucun luxe, mais d’une propreté recherchée. Mme Le Bas, la mère, (autrefois Mlle Duplay) et M. Le Bas l’entouraient de respects, la traitaient presque en souveraine. Elle parla peu pendant le repas, poliment, avec gravité : « Comment la trouvez-vous ? me dit M. le Bas quand nous fûmes seuls dans son cabinet. –Mais qui est-ce ? –Comment ? Je ne vous l’avais pas dit ? C’est la sœur de Robespierre. » J’étais alors élève de première année à l’École normale. »

L’élève de première année à l’École normale fut, depuis, un homme éminent, un philanthrope remarquable, et pourtant il lui arriva de manquer d’indulgence pour ceux de ses anciens professeurs qui l’avaient accueilli, pourtant, avec bonté : le cœur étant excellent chez lui, j’aime à croire que la mémoire seule était en défaut ; rien d’étonnant à ce qu’elle l’ait mal servi lorsqu’il écrivit sa chronique.

« Charlotte Robespierre – dit Philippe Le Bas dans son Dictionnaire encyclopédique de l’Histoire de la France – ne rougit pas de recevoir des assassins de ses frères une pension qui, de 6,000 fr. d’abord, puis réduite successivement jusqu'à 1,500, lui fut servie par tous les gouvernements qui se succédèrent jusqu'à sa mort (1834). Elle a laissé des Mémoires qui contiennent de curieux renseignements, mais où le faux se trouve trop souvent mêlé au vrai. »

Je ne pense pas que le savant consciencieux qui traça ces lignes ait jamais traité Mlle Robespierre en « souveraine » : c’est « solliciteuse » qu’a voulu écrire Jules Simon.

Aussi bien, Charlotte Robespierre ne saurait m’intéresser que par les lettres ou souvenirs où elle a parlé de son frère Maximilien, et, sur ce point, le document que reproduit M. Lenotre a le plus grand intérêt, parce qu’il dissipe des malentendus copieusement utilisés par certains écrivains ; c’est le testament que voici, conservé dans les archives de Me Dauchez, notaire à Paris :

« Voulant, avant de payer à la nature le tribut que tous les mortels lui doivent, faire connaître mes sentiments envers la mémoire de mon frère aîné, je déclare que je l’ai toujours connu pour un homme plein de vertu ; je proteste contre toutes les lettres contraires à son honneur, qui m’ont été attribuées, et, voulant ensuite disposer de ce que je laisserai à mon décès, j’institue pour mon héritière universelle, Mlle Reine-Louise-Victoire Mathon.

« Fait et écrit de ma main, à Paris, le 6 février 1828.

« Marie-Marguerite-Charlotte DE ROBESPIERRE. »

On ne peut guère discuter la sincérité de ceux qui vont mourir.

(Source : Paul Coutant, Autour de Robespierre : Le conventionnel Le Bas, d’après des documents inédits et les mémoires de sa veuve, Paris, E. Flammarion, 1901, p. 85-87.)

Annotations:

[1] Le souvenir de 1793 continue de lier plusieurs familles, dont la famille Le Bas-Duplay, comme l’écrit Florent Hericher, Philippe Le Bas (1794-1860), Un républicain de naissance, Paris, Librinova, 2021, p. 191, n. 276.

[2] Ce n’est pas tout à fait exact, vu la participation d’Albert Laponneraye au projet.

[3] Il est né à Lorient, en Bretagne, l’une des régions insurgée contre la Révolution et foyer de la Chouannerie. Le refus de la constitution civile du clergé (1791) et les tensions causées par la conscription du 15 août 1792 et la « levée de 300 000 hommes » décrétée le 24 février 1793 mènent à l’insurrection.

[4] Paul Coutant (Autour de Robespierre.., p. 85, n. 2) fait référence à l’ouvrage Vieilles maisons, vieux papiers (1900).

#jules simon#paul coutant#g. lenôtre#testimonials and commentaries#elisabeth duplay#philippe le bas fils#élisabeth duplay lebas#élisabeth duplay#élisabeth lebas#charlotte robespierre#19th century

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint-Just Speech: 10 October 1793

Excerpt from Saint-Just's Convention Speech << La nécessité de déclarer le gouvernement provisoire de la France révolutionnaire jusqu'à la Paix. >> given 19 vendémiaire an II (10 octobre 1793), which was recently read at the Pantheon in honor of 8-10 Thermidor, courtesy of a collaboration of the ARBR, Friends of Philippe LeBas and the DuPlay Family, and The Association of the Safeguarding of the House of Saint-Just. Special thanks to McPhee for forwarding the event details to me; I'm really glad they decided to upload this.

I really recommend reading this whole speech, and listening to it all if possible. Here's the link to the uploaded video. I say this about all the speeches but this one is really a good one. The actor they had reading did a really great job!

Speech + translation under the cut!

Anyways here's an excerpt of one of my favorite parts, towards the end.

<< Il faut donc que notre gouvernement regagne d'un côté ce qu'il a perdu de l'autre; il doit mettre tous les ennemisde la liberté dans l'impossibilité de lui nuire à mesure que les gens de bien périssent. Il faut faire la guerre avec prudence, et ménager notre sang, car on n'en veut qu'à lui ; l'Europe en a soif : vous avez cent mille hommes dans le tombeau qui ne défendent plus la liberté! Le gouvernement est leur assassin; c'est le crime des uns, c'est l'impuissance des autres et leur incapacité. Tous ceux qu'emploie le gouvernement sont paresseux; tout homme en place ne fait rien lui-même et prend des agents secondaires; le premier agent secondaire a les siens, et la République est en proie à vingt mille sots qui la cor- rompent, qui la combattent, qui la saignent; Vous devez diminuer partout le nombre des agents, afin que les chefs travaillent et pensent. Le ministère est un monde de papier. Je ne sais point comment Rome et l'Egypte se gouvernaient sans cette res- source; on pensait beaucoup; on écrivait peu. La prolixité de la correspondance et des ordres du gouvernement est une marque de son inertie; il est impossible que l'on gouverne sans laconisme. Les représentants du peuple, les généraux, les administrateurs, sont environnés de bureaux comme les anciens hommes de palais; il ne se fait rien, et la dépense est pourtant énorme. Les bureaux ont remplacé le monarchisme; le démon d'écrire nous fait la guerre, et l'on ne gouverne point.>>

Translation:

"Our government must therefore regain on one side what it has lost on the other; it must make all the enemies of liberty in the impossibility of harming it as the good perish- good people perish. We must wage war with prudence, and spare our blood, for it is only wanted; Europe is thirsty for it: you have a hundred thousand men in the grave who are no longer defending liberty! The government is their murderer; it's the crime of some, it's the impotence of others and their incapacity. All those employed by the government are lazy; every man in power does nothing himself and hires secondary secondary agents; the first secondary agent has his own, and the Republic is prey to twenty thousand fools who corrupt, abuse and bleed it dry. Reduce the number of agents everywhere, so that the leaders work and think. The Ministry is a world of paper. I don't know how Rome and Egypt governed themselves without this resource; they thought a lot; they wrote little. The complexity of government correspondence and orders is a mark of stagnation; it is impossible to govern without precision. People's representatives, generals and administrators are surrounded by offices like the old palace men. yet the expense is enormous. Offices have replaced monarchism; the demon of writing is waging war on us, and we're not governing at all."

#saint-just#french rev#saint just#french rev resources#saint just speeches#discours de saint-just#my translations#queue

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

PHILIPPE-GÉRARD (compositeur), “Léo FERRÉ, mon ami” (extraits), L’Humanité-dimanche du 29 janvier 1961 (et Les Copains d’la neuille n°33, p9) : LÉO FERRÉ, mon ami. Oui, depuis plus de quinze ans déjà. Et peut-être qu’aujourd’hui cette amitié grandit encore, comme sans cesse mon estime pour son talent. Aujourd’hui, c’est pour lui le triomphe. Son récital au Vieux-Colombier, c’est un évènement de la saison artistique à Paris… …J’ai rencontré Léo pour la première fois à Paris chez Edith Piaf. C’était peu après la Libération. Il arrivait de Monte-Carlo avec une pointe d’ail dans sa parole et des rayons de soleil méditerranéen cachés derrière son large front. Sa façon de se coiffer et ses lunettes cerclées de métal le faisaient un peu ressembler à un enfant de Beethoven et de Schubert, mais à beaucoup d’autres titres, même physiques, il était déjà Léo Ferré. Bien sûr, nous n’étions pas nombreux à nous en rendre compte, mais nous le savions au fond de nous-mêmes et c’était un peu de réconfort dans les moments difficiles que nous avons alors traversés ensemble. Car nous en avons mangé, à cette époque, de la vache enragée !… …Edith Piaf, à qui nous venions présenter, lui son remarquable “Opéra du ciel” et moi l’une de mes premières chansons sur des paroles de Francis Carco, “Le Voyageur”, ne chanta jamais ni l’une ni l’autre. Bien qu’elle nous accueillit toujours avec beaucoup de sympathie et même de chaleur, il nous fallut attendre quelques années pour qu’elle interprète, de lui, “Les Amants de Paris” qui fut la seule chanson de Léo à son répertoire, et de moi, “Pour moi toute seule”, qui marqua mon départ dans ce métier… http://www.frmusique.ru/texts/f/ferre_leo/operaduciel.htm , L'Opera Du Ciel Léo Ferré : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/104075228 EDITH PIAF - LES AMANTS DE PARIS Paroles: Léo Ferré, musique: Léo Ferré et Eddie Marnay, enr. 11 juin 1948, que l’on entend aussi dans le film de Jean Eustache LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pTr0zizDA8 Edith Piaf - Pour Moi Toute Seule (Guy Lafarge; Philippe-Gérard; Flavien Monod. Blues; “Edith Piaf Sings”; French; …): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4OA1jy-cj8 Renée Lebas , Le Voyageur sans bagage (ou Le Voyageur) - (Auteur : Francis Carco, F.Moslay. Compositeur : Philippe-Gérard ) : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/138826035 Catherine Sauvage, Le Voyageur (sans bagage) : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/74805675

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, you're the Lebas expert here so I would like to ask, do you know who Philippe Jr's godparents were?

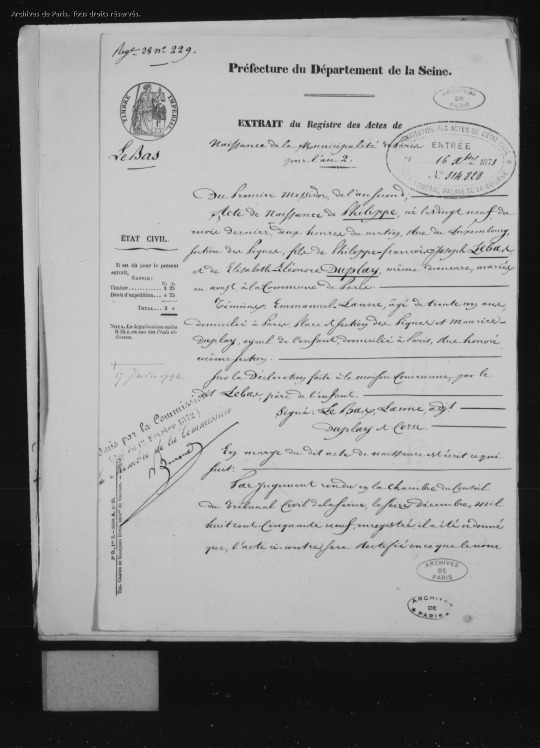

Philippe Le Bas son was born on 29 Prairial Year II (17 June 1794) at 2 AM. His birth was registered by his father two days later. It was not a religious ceremony so we can't talk about godparents. However, the witnesses were Maurice Duplay (the baby's maternal grandfather) and Emmanuel Lanne (I assume this dude).

Here is Philippe's reconstructed record of birth:

Source (pages 43-45 of that document)

And it's flattering to call me a Le Bas expert (aww), but I can't really claim to be so. @saintjustitude is an expert on this so he might want to clarify things if I missed something of importance.

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

The Robespierre siblings babysit Philippe Lebas jr, Horace Desmoulins and Danton’s sons. Who survives?

Aww, this sounds like the sweetest disaster!

I assume it would all start calmly; the remaining kids are dropped off at Danton's place, the most comfortable and the biggest one, where the uncles and aunt can look after them. After a few "remember, our son cannot be given any sugars" and "please remember to change his stockings three times during the day", the parents eventually leave for whatever important tasks they have to do.

Bonbon is overjoyed to be the crazy uncle and arranges all kind of games for the kids to participate in. Unfortunately, he underestimated the skills of toddlers and eventually remains the only one doing puzzles and the kids start to get out of control.

Auntie Charlotte tries her best with the little ones; she offers them games like hide and seek, and tries to keep her brothers engaged as well, as long as none of them wants to work in the meantime. Despite good intentions, a few pieces of furniture are damaged when Bonbon tries to hide with the kids in a cupboard, at least two kids begin to cry and have to be offered a sweet snack (against their parent's request) to calm down. Fueled by sugar and disastrous uncle only more misfortunes follow, including children hanging from a chandelier, Charlotte screaming, and her brother dramatically trying to rescue little Horace with a window curtain that rips apart once he takes it off the curtain rod.

Robespierre avoided a heart attack only because he was changing little Philippe's stockings in the other room and tried to put him to sleep. He comes back to the salon, that is all torn to pieces, when everything has already calmed down. He takes the exhausted kids (and equally tired siblings) to a most decent sofa left and reads them comforting fairytales goodnight. He'd rather avoid thinking of how Danton will react to half of his goods destroyed, but despite guilt hopes it will teach him more sense of modesty. Together, they are found peacefully asleep by the returning parents.

#ask#anon#awww just thinking lf them trying to babysit is hilarious xD#(probably) childless siblings trying their best

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite quotes from the fictional documentary on Robespierre :

Somebody : Don't you like foods ?

Robespierre : I do. I love fruits a lot, especially those wonderful fruits called oranges.

---

Catherine : Do you know Maximilien, you're the most attractive man in our society and maybe even in our city of Arras.

Maximilien laugh : Don't mock me. Dear Catherine, it's necessary that I reveal to you the secret of my heart : I haven't known happiness until this hour.

Catherine laugh : Maximilien. What a gallant man you are.

Maximilien resentful face : Excuse me...I must leave you.

---

Speaker : Can you give us your proof that Hebert was Danton's accomplice and paid by foreign country ?

Robespierre begins his speech.

Speaker : I repeat the question. Do you have any evidence ?

---

Journalist : But don't you think revolutionaries could form a new caste ?

Vadier : I don't understand...

Journalist : A new aristocracy based on administrative power ?

Vadier's brain stops working.

---

Augustin : I'm as guilty as my brother. I share his virtue, I want to share his fate. I also ask for the decree of accusation against me !

Maxime : No ! Augustin, no ! My brother was always away on missions. You can take my life but don't touch my brother !

Lebas : I refuse to share the opprobrium of this decree. I also demand my arrest !

Maxime : No Philippe ! Think about Élisabeth ! Think about your son !

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mémoires d'Elisabeth LeBas par Charlotte R, par E.Hamel et autres, sur sa vie, sur le plan de la maison de son père avant et après le 9 thermidor...

Lapeyronnet l'avait rencontrée aussi Charlotte

1 note

·

View note

Note

Do we have access to saint-just's personal letters if there any of them even exists? (I mean by personal is the letters he wrote to his family and relatives or friends etc.)

(The same question for robespierre, marat, camille, danton, desmoulins, the duplay family and other people from your personal choice if you find something)

We don’t have any complete correspondence from Saint-Just that I’m aware of, but some of his letters have been published within Oeuvres de Saint Just (1908) volume 1 (7 letters), volume 2 (2 letters). Of these, I would say the most personal ones are this letter SJ sent his brother-in-law in December 1791, congratulating him on his marriage, as well as this letter to Daubigny written the following year, which contains the (in)famous words: ”go and see Desmoulins, embrace him for me, and tell him I shall never see him again.” There’s also Lettres inédites de Saint-Just (five letters, half of which are work related and written while on mission) and Deux nouvelles lettres de Saint-Just à Garat (two letters). This last article includes the following letter, which I suppose also qualifies as personal:

Paris, July 8

Citizen and friend,

It’s been a while since I’ve given you news of mine, nevertheless I have forgotten none of the testimonies of friendships that you’ve given me. When shall I have the pleasure of seeing you here again, the same time as last year when we saw each other?

I have little leisure, I do what I can to respond to your trust and provided that I give an account of my moments to the people, friendship will not be more severe.

I’m going to occupy myself with citizen Chassie, with the affair of citizen Bailli whom I pray you to assure of my most sincere attachment. If it pleases you, tell our common acquaintances that I have not forgotten them. I embrace your wife, your children and you.

Saint-Just.

Aside from that:

Correspondance de Maximilien et Augustin Robespierre (1926) (I’ve already talked about in which letters you might find the most personal details in this old post)

La correspondance de Marat (1908) (not looked enough on this to say how many letters are personal and how many are strictly business related)

Correspondance de George Couthon (1872) (only work related letters as far as I’m aware, no letters to loved ones etc)

Correspondance inédite de Camille Desmoulins (1836) (quite a lot of personal details in the many letters Camille sent his father. English translations of letters to his father, Lucile and her mother can be found here. Here is also a long, personal letter Camille wrote in 1782, the oldest conserved one from him that I’m aware of.)

Danton — for being a ”main revolutionary” we have surprisingly few letters from him. All I know of at this point are presented in this post.

Duplays — the only personal Ietter I’m aware of is this one which Madame Duplay adressed to her second oldest daughter Sophie written 1793. Two letters from Robespierre to Maurice Duplay can also be found in the former’s correspondence.

Correspondance de Brissot (1912)

Lettres de Madame Roland (1900)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Correspondance inédite de Marie-Antoinette (1864)

Lettres de Louis XVI: correspondance inédite, discours, maximes, pensées, observations etc (1862)

Memoirs, Correspondence and Manuscripts of General Lafayette (1837)

Volume 1

Volume 2

Volume 3

Two cute letters from Philippe to Élisabeth Lebas, both from November 1793. Many letters from Lebas to his father can also be found within Le Conventionnel Le Bas… (1901)

Philippeaux’ three prison letters to his wife

#saint-just#robespierre#marat#desmoulins#danton#frev#ask#brissot#manon roland#louis xvi#marie antoinette#lafayette#philippe lebas#pierre philippeaux

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hörbücher u.ä. mit André Kaczmarczyk

bis 2022

Ich gehe in ein anderes Blau – Lange Nacht über Novalis, Deutschlandfunk 2022. DLF

Sister Morphine – Musiker und Drogen. Feature von Burkhard Reinartz, Deutschlandfunk 2022. DLF

Entführung in die Zukunft (Lesung?). Kurzgeschichte von Robert Heinlein, WDR 1LIVE 2022.

Tick Tack (Ungekürzte Lesung, Rolle: Jo). Von Julia von Lucadou, Tacheles Verlag 2022. Spotify (auch als mp3-CD + Download)

Gespräch über Orlando. WDR3 Mosaik 2022. WDR

Die Irrfahrten des Sergej Sergejewitsch (Rolle: Sergej Prokofjew). Von Lucius Plessner, WDR3 2022. WDR

Preussen - Im Kopf (Rolle: Historiker). Von Tom Peuckert, WDR3 2021. gratis-hoerspiele.de

Wo die Freiheit wächst (Rolle: Franz). Von Frank Maria Reifenberg, WDR3 2021. ARD-Audiothek

Dein haploides Herz (Rolle: Pax Patton). Von James Tiptree Jr., WDR3 2021. WDR

Überredung (Rolle: Mr. Eliot). Von Jane Austen, HR2 2021. Teil 1 Teil 2 (auch als Audio-CDs)

Medium Rare (Lesung?). Kurzgeschichte von Bella Bender, WDR 1LIVE 2021.

Lost and Sound. Podcast von und mit André Kaczmarczyk und Janine Ortiz, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus 2020–2021. dhaus.de - zum Download: podcast.de

Der Seiltänzer (Lesung eines Ausschnitts). Von Jean Genet, nachtkritik.de-Adventskalender2020. YouTube

Die USA im Jahr 2020 – Die Schattenseiten des amerikanischen Traums. Feature von Sabine Schmidt, DLF 2020. radiohoerer.de

Beethovens Blues – Was hört, wer nichts hört? Feature von Stefan Zednik, Deutschlandfunk 2020. radiohoerer.de

Der zerbrochene Spiegel – Über die Angst vor der Hässlichkeit. Feature von Uta Rüenauver, DLF 2020. radiohoerer.de

Schweigen oder Schreiben – Eine lange Nacht über die Verwandlung von Leid in Literatur. Von Burkhard Reinartz, DLF 2020. radiohoerer.de

Die Pop-Inklusion - Die Band Station 17 wird 30. Von Joachim Palutzki, Deutschlandfunk 2019. DLF

Marlov in Jerusalem (Rolle: Inspektor Kravitz). Von David Zane Mairowitz, WDR 2019. YouTube

Die Jaguarschamanen sterben aus – Expedition in den Amazonaswald. Feature von Thomas Fischermann, DLF 2019. radiohoerer.de

Das ganz, ganz große Glück - Ein Reihenhaus Blues im Schlagertakt. Feature von Tabea Soergel & Martin Becker, NDR 2019. ARD-Audiothek

*neu* Brüder (Rolle: Philippe-François-Joseph Lebas). Von Hilary Mantel, WDR 2018. ARD-Audiothek

Das Fundament der Ewigkeit (Rolle: Pierre Aumand - jung). Von Ken Follett, WDR 2018. Spotify (auch als Audio-CD)

Ausschnitte und O-Töne aus Stücken im Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus 2016– . dhaus.de

Gold. Revue von Jan Wagner (Rolle: Der Boss), R: Leonhard Koppelmann, Deutschlandfunk 2016. ARD-Audiothek (auch als Audio-CD)

Allerleirauh - Hörspiel zum ARD Märchenfilm (Rolle: König Jakob). Von Brüder Grimm, ARD 2012. gratis-hoerspiele.de

The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum (Narrator). By Heinrich Böll, R: Polly Thomas, BBC London Radio4 2012. avenita.net

Goodbye To Berlin (Bernhard Landauer). By Christopher Isherwood, R: Polly Thomas, BBC London Radio4 2010. avenita.net

*neu* Erzählungen aus Kolyma (Rolle: Kolja). Von Warlam Schalamow, R: Martin Heindel, rbb 2010. archive.org

Das Wismutspiel, Szenen nach Rummelplatz von Werner Bräunig (Rolle: Erzähler), R: Gabriele Bigott, rbb 2010.

Schnipsel: eins zwei drei

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

@anotherhumaninthisworld

It's a very small part of my thesis actually! (Which is 578 pages long.) I must submit the final version on April 3rd so I'm working on small revisions concerning typos, grammar, syntax, repetitions, one or two factual mistakes, weird phrasings, etc. amd re-reading the whole thing of course.

Shortly after it's been officially accepted, it will be available as a pdf file via my university.

There will definitely be a published version eventually, though it's still unclear what it could cover. They could choose the whole thing, or just my commented edition of Élisabeth's memoirs + other relevant documents such as Jules Simon's anecdote. It depends on the publishers.

I've been thinking about this. We need to compare and consider the dates: when this meeting happens (sometime in 1833), when Laponneraye publishes Charlotte's memoirs (1834, after her death on August 1st), when Le Bas fils writes a critique of them (1845). There's also the fact Élisabeth starts writing her memoirs circa 1843-1844 which is still a few years for resentment towards Charlotte to grow again, plus the political context is changing fast, and Philippe fils himself gets involved in politics. (I think I might have forgotten to reflect on this specific detail in my thesis. There's a lot to cover lol.)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Léo FERRÉ, mon ami

PHILIPPE-GÉRARD (compositeur), “Léo FERRÉ, mon ami” (extraits), L’Humanité-dimanche du 29 janvier 1961 (et Les Copains d’la neuille n°33, p9) : LÉO FERRÉ, mon ami. Oui, depuis plus de quinze ans déjà. Et peut-être qu’aujourd’hui cette amitié grandit encore, comme sans cesse mon estime pour son talent. Aujourd’hui, c’est pour lui le triomphe. Son récital au Vieux-Colombier, c’est un évènement de la saison artistique à Paris... ...J’ai rencontré Léo pour la première fois à Paris chez Edith Piaf. C’était peu après la Libération. Il arrivait de Monte-Carlo avec une pointe d’ail dans sa parole et des rayons de soleil méditerranéen cachés derrière son large front. Sa façon de se coiffer et ses lunettes cerclées de métal le faisaient un peu ressembler à un enfant de Beethoven et de Schubert, mais à beaucoup d’autres titres, même physiques, il était déjà Léo Ferré. Bien sûr, nous n’étions pas nombreux à nous en rendre compte, mais nous le savions au fond de nous-mêmes et c’était un peu de réconfort dans les moments difficiles que nous avons alors traversés ensemble. Car nous en avons mangé, à cette époque, de la vache enragée !... ...Edith Piaf, à qui nous venions présenter, lui son remarquable “Opéra du ciel” et moi l’une de mes premières chansons sur des paroles de Francis Carco, “Le Voyageur”, ne chanta jamais ni l’une ni l’autre. Bien qu’elle nous accueillit toujours avec beaucoup de sympathie et même de chaleur, il nous fallut attendre quelques années pour qu’elle interprète, de lui, “Les Amants de Paris” qui fut la seule chanson de Léo à son répertoire, et de moi, “Pour moi toute seule”, qui marqua mon départ dans ce métier... http://www.frmusique.ru/texts/f/ferre_leo/operaduciel.htm , L'Opera Du Ciel Léo Ferré : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/104075228 EDITH PIAF - LES AMANTS DE PARIS Paroles: Léo Ferré, musique: Léo Ferré et Eddie Marnay, enr. 11 juin 1948, que l’on entend aussi dans le film de Jean Eustache LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pTr0zizDA8 Edith Piaf - Pour Moi Toute Seule (Guy Lafarge; Philippe-Gérard; Flavien Monod. Blues; "Edith Piaf Sings"; French; ...): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4OA1jy-cj8 Renée Lebas , Le Voyageur sans bagage (ou Le Voyageur) - (Auteur : Francis Carco, F.Moslay. Compositeur : Philippe-Gérard ) : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/138826035 Catherine Sauvage, Le Voyageur (sans bagage) : http://www.deezer.com/fr/track/74805675

#Léo Ferré#Philippe-Gérard#Edith Piaf#L'Opéra du ciel#Francis Carco#Le Voyageur#Les amants de Paris#Pour moi toute seule#L'Humanité-dimanche#Les Copains d'la neuille#Eddie Marnay#Jean Eustache#la maman et la putain#Renée Lebas#Le Voyageur sans bagage#Catherine Sauvage

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Philippe Drecq & Joséphine Lebas-Joly,

“Jeux d'enfants” (Yann Samuell, 2003).

#haidagiffare#amami se hai coraggio#donna#jeux d'enfants#gif#cucinare#dieta#depilazione#philippe drecq#josephine lebas-joly#yann samuell

238 notes

·

View notes

Photo

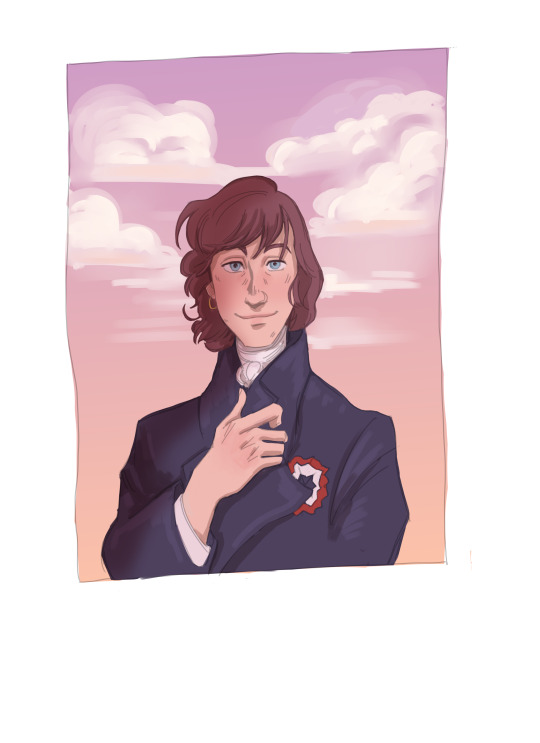

pov; you are philippe lebas and you’re one of the few lucky people who get to see saint-just smile

225 notes

·

View notes