#pretentious cineasts

Text

“I prefer foreign and independent films.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

ask game: bergman

going to assume you're talking about ingmar and not ingrid:

Many people of my generation may have joined the National Film Theatre in London to see a retrospective survey of Bergman’s early films after The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries had come to represent “artistic” cinema. The first critical articles that I struggled with—as reader and writer—were on Bergman. Inevitably he suffered from being so suddenly revealed to a volatile world. Looking back, it seems no coincidence that those two films are his most pretentious and calculating. Within a few years he was being mocked and parodied for his earnestness and symbolism. The young cineastes led to the art houses were rediscovering the virtues of the American films that had delighted them as children. The new French cinema endorsed that love of development and replaced Bergman’s concentration with improvisation, humor, offhand tenderness, and a non-Northern feeling for the beauty of camera movements as opposed to the force of composition.

By about 1961 Bergman held the unenviable position of a discredited innovator in a fashion-conscious world. That reputation was, I think, deserved. So Close to Life, The Face, The Virgin Spring, and The Silence suffer because the artistic virtuosity seems complacent beside the professed anguish of the work. Far from being moving and engrossing, these films verge on a dreadfully clear-eyed and articulated morbidity. The gap between preoccupation and art was amounting to decadence.

It is worth stressing the dilemma Bergman found himself in at this time because of his response to it. He was not the first figure from Swedish cinema to be invited to more lavish production setups. His international success had made him possibly the best known of living Swedish artists, a spokesman for the rather precious political neutrality and social enlightenment that Sweden embraced, and the prophet of its overriding sense of guilt. What made Bergman a great director, it seems to me, is the recognition that he was (or had become) his own subject, that the anguish in his films could become central. For that to work, he had to decline attractive invitations and stay in Sweden.

this section was quite long, so i picked the heart of it for you

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Excerpt of the Essay: David Lynch Keeps His Head by David Foster Wallace

I know a lot of you love David Lynch and this is an EXCELLENT defense and deconstruction of his work. The full essay is largely about the film Lost Highway, which was about to be released, and is 67 pages with 61 footnotes. The whole essay is incredibly entertaining and if you like to read, is worth it. You can find it here: x. This excerpt mainly concerns Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. I put the footnotes at the end, I know it isn’t ideal, but it is hard when there aren’t pages.

9A. The cinematic tradition it’s curious that nobody seems to have observed Lynch comes right out of (w/ an epigraph)

“It has been said that the admirers of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari are usually painters, or people who think and remember graphically. This is a mistaken conception.”

—Paul Rotha, “The German Film”

Since Lynch was trained as a painter (an Ab-Exp painter at that), it seems curious that no film critics or scholars(42) have ever treated of his movies’ clear relation to the classical Expressionist cinema tradition of Wiene, Kobe, early Lang, etc. And I am talking here about the very simplest and most straightforward sort of definition of Expressionist, viz. “Using objects and characters not as representations but as transmitters for the director’s own internal impressions and moods.”

Certainly plenty of critics have observed, with Kael, that in Lynch’s movies “There’s very little art between you and the filmmaker’s psyche…because there’s less than the usual amount of inhibition.” They’ve noted the preponderance of fetishes and fixations in Lynch’s work, his characters’ lack of conventional introspection (an introspection which in film equals “subjectivity”), his sexualization of everything from an amputated limb to a bathrobe’s sash, from a skull to a “heart plug,”(43) from split lockets to length-cut timber. They’ve noted the elaboration of Freudian motifs that tremble on the edge of parodic cliche—the way Marietta’s invitation to Sailor to “fuck Mommy” takes place in a bathroom and produces a rage that’s then displaced onto Bob Ray Lemon; the way Merrick’s opening dream-fantasy of his mother supine before a rampaging elephant has her face working in what’s interpretable as either terror or orgasm; the way Lynch structures Dune’s labrynthian plot to highlight Paul Eutrades’s “escape” with his “witch-mother” after Paul’s father’s “death” and “betrayal.” They have noted with particular emphasis what’s pretty much Lynch’s most famous scene, Blue Velvet’s Jeffrey Beaumont peering through a closet’s slats as Frank Booth rapes Dorothy while referring to himself as “Daddy” and to her as “Mommy” and promising dire punishments for “looking at me” and breathing through an unexplained gas mask that’s overtly similar to the O2-mask we’d just seen Jeffrey’s own dying Dad breathing through.

They’ve noted all this, critics have, and they’ve noted how, despite its heaviness, this Freudian stuff tends to give Lynch’s movies an enormous psychological power; and yet they don’t seem to make the obvious point that these very heavy Freudian riffs are powerful instead of ridiculous because they are deployed Expressionistically, which among other things means they’re deployed in an old-fashioned, pre-postmodern way, I.e. nakedly, sincerely, without postmodernism’s abstraction or irony. Jeffrey Beaumont’s interslat voyeurism may be a sick parody of the Primal Scene, but neither he (a “college boy”) nor anybody else in the movie ever shows any inclination to say something like “Gee, this is sort of like a sick parody of the good old Primal Scene” or even betrays any awareness that a lot of what’s going on is—both symbolically and psychoanalytically—heavy as hell. Lynch’s movies, for all their unsubtle archetypes and symbols and intertextual references and c., have about them the remarkable unselfish-consciousness that’s kind of the hallmark of Expressionist art—nobody in Lynch’s movies analyzes or metacriticizes or hermenteuticizes or anything(44), including Lynch himself. This set of restrictions makes Lynch’s movies fundamentally unironic, and I submit that Lynch’s lack of irony is the real reason some cineastes—in this age when ironic self-consciousness is the one and only universally recognized badge of sophistication—see him as a naif or a buffoon. In fact, Lynch is neither—though nor is he any kind of genius of visual coding or tertiary symbolism or anything. What he is is a weird hybrid blend of classical Expressionist and contemporary postmodernist, an artist whose own “internal impressions and moods” are (like ours) an olla podrida of neurogenic predisposition and phylogenic myth and psychoanalytic schema and pop-cultural iconography—in other words, Lynch is sort of G. W. Pabst with an Elvis ducktail.

This kind of contemporary Expressionist art, in order to be any good, seems like it needs to avoid two pitfalls. The first is a self-consciousness of form where everything gets very mannered and refers cutely to itself.(45) The second pitfall, more complicated, might be called “terminal idiosyncrasy” or “antiempathetic solipsism” or something: here the artist’s own perceptions and moods and impressions and obsessions come off as just too particular to him alone. Art, after all, is supposed to be a kind of communication, and “personal expression” is cinematically interesting only to the extent that what’s expressed finds and strikes chords within the viewer. The difference between experiencing art that succeeds as communication and art that doesn’t is rather like the difference between being sexually intimate with a person and watching that person masturbate. In terms of literature, richly communicative Expressionism is epitomized by Kafka, bad and onanistic Expressionism by the average Graduate Writing Program avant-garde story.

It’s the second pitfall that’s especially bottomless and dreadful, and Lynch’s best movie, Blue Velvet, avoided it so spectacularly that seeing the movie when it first came out was a kind of revelation for me. It was such a big deal that ten years later I remember the date—30 March 1986, a Wednesday night—and what the whole group of us MFA Program(46) students did after we left the theater, which was to go to a coffeehouse and talk about how the movie was a revelation. Our Graduate MFA Program had been pretty much of a downer so far: most of us wanted to see ourselves as avant-garde writers, and our professors were all traditional commercial Realists of the New Yorker school, and while we loathed these teachers and resented the chilly reception our “experimental” writing received from them, we were also starting to recognize that most of our own avant-garde stuff really was solipsistic and pretentious and self-conscious and masturbatory and bad, and so that year we went around hating ourselves and everyone else and with no clue about how to get experimentally better without caving in to loathsome commercial-Realistic pressure, etc. This was the context in which Blue Velvet made such an impression on us. The movie’s obvious “themes”—the evil flip side to picket-fence respectability, the conjunctions of sadism and sexuality and parental authority and voyeurism and cheesy ‘50s pop and Coming of Age, etc.—were for us less revelatory than the way the movie’s surrealism and dream-logic felt: the felt true, real. And the couple things just slightly but marvelously off in every shot—the Yellow Man literally dead on his feet, Frank’s unexplained gas mask, the eerie industrial thrum on the stairway outside Dorothy’s apartment, the weird dentate-vagina sculpture(47) hanging on an otherwise bare wall over Jeffrey’s bed at home, the dog drinking from the hose in the stricken dad’s hand—it wasn’t just that these touches seemed eccentrically cool or experimental or arty, but that they communicated things that felt true. Blue Velvet captured something crucial about the way the U.S. present acted on our nerve endings, something crucial that couldn’t be analyzed or reduced to a system of codes or aesthetic principles or workshop techniques.

This was what was epiphanic for us about Blue Velvet in grad school, when we saw it: the movie helped us realize that first-rate experimentalism was a way not to “transcend” or “rebel against” the truth but actually to honor it. It brought home to us—via images, the medium we were suckled on and most credulous of—that the very most important artistic communications took place at a level that not only wasn’t intellectual but wasn’t even fully conscious, that the unconscious’s true medium wasn’t verbal but imagistic, and that whether the images were Realistic or Postmodern of Expressionistic of Surreal of what-the-hell-ever was less important than whether they felt true, whether they rang psychic cherries in the communicatee.

I don’t know whether any of this makes sense. But it’s basically why David Lynch the filmmaker is important to me. I felt like he showed me something genuine and important on 3/30/86. And he couldn’t have done it if he hadn’t been thoroughly, nakedly, unpretentiously, unsophisticatedly himself, a self that communicates primarily itself—an Expressionist. Whether he is an Expressionist naively or pathologically or ultra-pomo-sophisticatedly is of little importance to me. What is important is that Blue Velvet rang cherries, and it remains for me an example of contemporary artistic heroism.

10A (w/ an epigraph)

“All of Lynch’s work can be described as emotionally infantile…Lynch likes to ride his camera into orifices (a burlap hood’s eyehole or a severed ear), to plumb the blackness beyond. There, id-deep, he fans out his deck of dirty pictures…”—Kathleen Murphy of Film Comment

One reason it’s sort of heroic tot be a contemporary Expressionist is that it all but invites people who don’t like your art to make an ad hominem move from the art to the artist. A fair number of critics(48) object to David Lynch’s movies on the grounds that they are “sick” and “dirty” or “infantile,” then proceed to claim that the movies are themselves revelatory of various deficiencies in Lynch’s own character, (49) troubles that range from developmental arrest to misogyny to sadism. It’s not just the fact that twisted people do hideous things to one another in Lynch’s films, these critics will argue, but rather the “moral attitude” implied by the way Lynch’s camera records hideous behavior. In a way, his detractors have a point. Moral atrocities in Lynch movies are never staged to elicit outrage or even disapproval. The directorial attitude when hideousness occurs seems to range between clinical neutrality and an almost voyeuristic ogling. It’s not an accident that Frank Booth, Bobby Peru, and Leland/“Bob” steal the show in Lynch’s last three films, that there is almost a tropism about our pull toward these characters, because Lynch’s camera is obsessed with them, loves them; they are his movies’ heart.

Some of the ad hominem criticism is harmless, and the director himself has to a certain extent dined out on his “Master of Weird”/“Czar of Bizarre” image, see for example Lynch making his eyes go in two different directions for the cover of Time. The claim, though, that because Lynch’s movies pass no overt “judgement” on hideousness/evil/sickness and in fact make the stuff riveting to watch, the movies are themselves a-or immoral, even evil—this is bullshit of the rankest vintage, and not just because it’s sloppy logic but because it’s symptomatic of the impoverished moral assumptions we seem not to bring to the movies we watch.

I’m going to claim that evil is what David Lynch’s movies are essentially about, and that Lynch’s explorations of human beings’ various relationships to evil are, if idiosyncratic and Expressionistic, nevertheless sensitive and insightful and true. I’m going to submit that the real “moral problem” a lot of cineastes have with Lynch is that we find his truth morally uncomfortable, and that we do not like, when watching movies, to be made uncomfortable. (Unless, of course, our discomfort is used to set up some kind of commercial catharsis—the retribution, the bloodbath, the romantic victory of the misunderstood heroine, etc.—I.e. unless the discomfort serves a conclusion that flatters the same comfortable moral certainties we came into the theater with.)

The fact is that David Lynch treats the subject of evil better than just about anybody else making movies today—better and also differently. His movies aren’t anti-moral, but they are definitely anti-formulaic. Evil-ridden though his filmic world is, please notice that responsibility for evil never in his films devolves easily onto greedy corporations or corrupt politicians or faceless serial kooks. Lynch is not interested in the devolution of responsibility, and he’s not interested in moral judgments of characters. Rather, he’s interested in the psychic spaces in which people are capable of evil. He is interested in Darkness. And Darkness, in David Lynch’s movies, always wears more than one face. Recall, for example, how Blue Velvet’s Frank Booth is both Frank Booth and “the Well-Dressed Man.” How Eraserhead’s whole postapocalyptic world of demonic conceptions and teratoid offspring and summary decapitations is evil…yet how it’s “poor” Henry Spencer who ends up a baby-killer. How in both TV’s Twin Peaks and cinema’s Fire Walk with Me, “Bob” is also Leland Palmer, how they are, “spiritually,” both two and one. The Elephant Man’s sideshow barker is evil in his exploitation of Merrick, but so too is good old kindly Dr. Treeves—and Lynch carefully has Treeves admit this aloud. And if Wild at Heart’s coherence suffered because its myriad villains seemed fuzzy and interchangeable, it was because they were all basically the same thing, I.e. they were all in the service of the same force or spirit. Characters are not themselves evil in Lynch movies—evil wears them.

This point is worth emphasizing. Lynch’s movies are not about monsters (i.e. people whose intrinsic natures are evil) but about hauntings, about evil environment, possibility, force. This helps explain Lynch’s constant deployment of noirish lighting and eerie sound-carpets and grotesque figurants: in his movies’ world, a kind of ambient spiritual antimatter hangs just overhead. It also explains why Lynch’s villains seem not merely wicked or sick but ecstatic, transported: they are, literally, possessed. Think here of Dennis Hopper’s exultant “I’LL FUCK ANYTHING THAT MOVES” in Blue Velvet, or of the incredible scene in Wild at Heart when Diane Ladd smears her face with lipstick until it’s devil-red and then screams at herself in the mirror, or of “Bob”’s look of total demonic ebullience in Fire Walk with Me when Laura discovers him at her dresser going through her diary and just about dies of fright. The bad guys in Lynch movies are always exultant, orgasmic, most fully present at their evilest moments, and this in turn is because they are not only actuated by evil but literally inspired(50): they have yielded themselves up to a Darkness way bigger than any one person. And if these villains are, at their worst moments, riveting for both the camera and the audience, it’s not because Lynch is “endorsing” or “romanticizing” evil but because he’s diagnosing it—diagnosing it without the comfortable carapace of disapproval and with an open acknowledgment of the fact that one reason why evil is so powerful is that it’s hideously vital and robust and usually impossible to look away from.

Lynch’s idea that evil is a force has unsettling implications. People can be good or bad, but forces simply are. And forces are—at least potentially—everywhere. Evil for Lynch thus moves and shifts, (51) pervades; Darkness is in everything, all the time—not “lurking below” or “lying in wait” or “hovering on the horizon”: evil is here, right now. And so are Light, love, redemption (since these phenomena are also, in Lynch’s work, forces and spirits), etc. In fact, in a Lynchian moral scheme it doesn’t make much sense to talk about either Darkness or about Light in isolation from its opposite. It’s not just that evil is “implied by” good or Darkness by Light or whatever, but that the evil stuff is contained within the good stuff too, encoded in it.

You could call this idea of evil Gnostic, or Taoist, or neo-Hegelian, but it’s also Lynchian, because what Lynch’s movies(52) are all about is creating a narrative space where this idea can be worked out in its fullest detail and to its most uncomfortable consequences.

And Lynch pays a heavy price—both critically and financially—for trying to explore worlds like this. Because we Americans like our art’s moral world to be cleanly limned and clearly demarcated, neat and tidy. In many respects it seems we need our art to be morally comfortable, and the intellectual gymnastics we’ll go through to extract a black-and-white ethics from a piece of art we like are shocking if you stop and look closely at them. For example, the supposed ethical structure Lynch is most applauded for is the “Seamy Underside” structure, the idea that dark forces roil and passions seethe beneath the green lawns and PTA potlucks of Anytown, USA.(53) American critics who like Lynch applaud his “genius for penetrating the civilized surface of everyday life to discover the strange, perverse passions beneath” and his movies are providing “the password to an inner sanctum of horror and desire” and “evocations of the malevolent forces at work beneath nostalgic constructs.”

It’s little wonder that Lynch gets accused of voyeurism: critics have to make Lynch a voyeur in order to approve something like Blue Velvet from within a conventional moral framework that has Good on top/outside and Evil below/within. The fact is that critics grotesquely misread Lynch when they see this idea of perversity “beneath” and horror “hidden” as central to his movies’ moral structure.

Interpreting Blue Velvet, for example, as a film centrally concerned with “a boy discovering corruption in the heart of a town”(54) is about as obtuse as looking at the robin perched on the Beaumonts’ windowsill at the movie’s end and ignoring the writhing beetle the robin’s got in its beak.(55) The fact is that Blue Velvet is basically a coming-of-age movie, and, while the brutal rape Jeffrey watches from Dorothy’s closet might be the movie’s most horrifying scene, the real horror in the movie surrounds discoveries that Jeffrey makes about himself—for example, the discovery that part of him is excited by what he sees Frank Booth do to Dorothy Vallens. (56) Frank’s use, during the rape, of the words “Mommy” and “Daddy,” the similarity between the gas mask Frank breathes through in extremis and the oxygen mask we’ve just seen Jeffrey’s dad wearing in the hospital—this kind of stuff isn’t there just to reinforce the Primal Scene aspect of the rape. The stuff’s also there to clearly suggest that Frank Booth is, in a certain way, Jeffrey’s “father,” that the Darkness inside Frank is also encoded in Jeffrey. Gee-whiz Jeffrey’s discovery not of dark Frank but of his own dark affinities with Frank is the engine of the movie’s anxiety. Note for example that the long and somewhat heavy angst-dream Jeffrey suffers in the film’s second act occurs not after he has watched Frank brutalize Dorothy but after he, Jeffrey, has consented to hit Dorothy during sex.

There are enough heavy clues like this to set up, for any marginally attentive viewer, what is Blue Velvet’s real climax, and its point. The climax comes unusually early,(57) near the end of the film’s second act. It’s the moment when Frank turns around to look at Jeffrey in the back seat of the car and says “You’re like me.” This moment is shot from Jeffrey’s visual perspective, so that when Frank turns around in the seat he speaks both to Jeffrey and to us. And here Jeffrey—who’s whacked Dorothy and liked it—is made exceedingly uncomfortable indeed; and so—if we recall that we too peeked through those close-vents at Frank’s feast of sexual fascism, and regarded, with critics, this scene as the film’s most riveting—are we. When Frank says “You’re like me,” Jeffrey’s response is to lunge wildly forward in the back seat and punch Frank in the nose—a brutally primal response that seems rather more typical of Frank than of Jeffrey, notice. In the film’s audience, I, to whom Frank has also just claimed kinship, have no such luxury of violent release; I pretty much just have to sit there and feel uncomfortable.(58)

And I emphatically do not like to be made uncomfortable when I go to see a movie. I like my heroes virtuous and my victims pathetic and my villains’ villainy clearly established and primly disapproved of by both plot and camera. When I go to movies that have various kinds of hideousness in them, I like to have my own fundamental difference from sadists and fascists and voyeurs and psychos and Bad People unambiguously confirmed and assured by those movies. I like to judge. I like to be allowed to root for Justice To Be Done without a slight squirmy suspicion (so prevalent and depressing in real moral life) that Justice probably wouldn’t be all that keen on certain parts of my character, either.

I don’t know whether you are like me in these regards or not…though from the characterizations and moral structures in the U.S. movies that do well at the box-office I deduce that there must be a lot of Americans who are exactly like me.

I submit that we also, as an audience, really like the idea of secret and scandalous immoralities unearthed and dragged into the light and exposed. We like this stuff because secrets’ exposure in a movie creates in us impressions of epistemological privilege, of “penetrating the civilized surface of everyday life to discover the strange, perverse passions beneath.” This isn’t surprising: knowledge is power, and we (I, anyway) like to feel powerful. But we also like the idea of “secrets,” “of malevolent forces at work beneath…” so much because we like to see confirmed our fervent hope that most bad and seamy stuff really is secret, “locked away” or “under the surface.” We hope fervently that this is so because we need to be able to believe that our own hideousnesses and Darkness are secret. Otherwise we get uncomfortable. And, as part of an audience, if a movie is structured in such a way that the distinction between surface/Light/good and secret/Dark/evil is messed with—in other words, not a structure whereby Dark Secrets are winched ex machina up to the Lit Surface to be purified by my judgement, but rather a structure in which Respectable Surfaces and Seamy Undersides are mingled, integrated, literally mixed up—I am going to be made acutely uncomfortable. And in response to my discomfort I’m going to do one of two things: I’m either going to find some way to punish the movie for making me uncomfortable, or I’m going to find a way to interpret the movie that eliminates as much of the discomfort as possible. From my survey of published work on Lynch’s films, I can assure you that just about every established professional reviewer and critic has chosen one or the other of these responses.

I know this all looks kind of abstract and general. Consider the specific example of Twin Peaks’s career. Its basic structure was the good old murder-whose-investigation-opens-a-can-of-worms formula right out of Noir 101—the search for Laura Palmer’s killer yields postmortem revelations of a double life (Laura Palmer=Homecoming Queen & Laura Palmer=Tormented Coke-Whore by Night) that mirrored the whole town’s moral schizophrenia. The show’s first season, in which the plot movement consisted mostly of more and more subsurface hideousnesses being uncovered and exposed, was a huge smash. By the second season, though, the mystery-and-investigation structure’s own logic began to compel the show to start getting more focused and explicit about who or what was actually responsible for Laura’s murder. And the more explicit Twin Peaks tried to get, the less popular the series became. The mystery’s final “resolution,” in particular, was felt by critics and audiences alike to be deeply unsatisfying. And it was. The “Bob”/Leland/Evil Owl stuff was fuzzy and not very well rendered,(59) but the really deep dissatisfaction—the one that made audiences feel screwed and betrayed and fueled the critical backlash against the idea of Lynch as Genius Auteur—was, I submit, a moral one. I submit that Laura Palmer’s exhaustively revealed “sins” required, by the moral logic of American mass entertainment, that the circumstances of her death turn out to be causally related to those sins. We as an audience have certain core certainties about sowing and reaping, and these certainties need to be affirmed and massaged.(60) When they were not, and as it became increasingly clear that they were not going to be, Twin Peaks’s ratings fell off the shelf, and critics began to bemoan this once “daring” and “imaginative” series’ decline into “self-reference” and “mannered incoherence.”

And then Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lynch’s theatrical “prequel” to the TV series, and his biggest box-office bomb since Dune, committed a much worse offense. It sought to transform Laura Palmer from dramatic object to dramatic subject. As a dead person, Laura’s existence on the television show had been entirely verbal, and it was fairly easy to conceive her as a schizoid black/white construct—Good by Day, Naughty by Night, etc. But the movie in which Ms. Sheryl Lee as Laura is on-screen more or less constantly, attempts to present this multivalent system of objectified personas—plaid-skirted coed/bare-breasted roadhouse slut/tormented exorcism-candidate/molested daughter—as an integrated and living whole: these different identities were all, the movie tried to claim, the same person. In Fire Walk with Me, Laura was no longer “an enigma” or “the password to an inner sanctum of horror.” She now embodied, in full view, all the Dark Secrets that on the series had been the stuff of significant glances and delicious whispers.

This transformation of Laura from object/occasion to subject/person was actually the most morally ambitious thing a Lynch movie has ever tried to do—maybe an impossible thing, given the psychological text of the series and the fact that you had to be familiar with the series to make even marginal sense of the movie—and it required complex and contradictory and probably impossible things from Ms. Lee, who in my opinion deserved an Oscar nomination just for showing up and trying.

The novelist Steve Erickson, in a 1992 review of Fire Walk with Me, is one of the few critics who gave any indication of even trying to understand what the movie was trying to do: “We always knew Laura was a wild girl, the homecoming femme fatale who was crazy for cocaine and fucked roadhouse drunks less for the money than the sheer depravity of it, but the movie is finally not so much interested in the titillation of that depravity as [in] her torment, depicted in a performance by Sheryl Lee so vixenish and demonic it’s hard to know whether it’s terrible or a de force. [But not trying too terribly hard, because now watch:] Her fit of the giggles over the body of a man whose head has just been blown off might be an act of innocence or damnation [get ready:] or both.” Or both? Of course both. This is what Lynch is about in this movie: both innocence and damnation; both sinned-against and sinning. Laura Palmer in Fire Walk with Me is both “good” and “bad,” and yet also neither: she’s complex, contradictory, real. And we hate this possibility in movies; we hate the “both” shit. “Both” comes off as sloppy characterization, muddy filmmaking, lack of focus. At any rate that’s what we criticized Fire Walk with Me’s Laura for.(61) But I submit that the real reason we criticized and disliked Lynch’s Laura’s muddy bothness is that it required of us empathetic confrontation with the exact muddy bothness in ourselves and our intimates that makes the real world of moral selves so tense and uncomfortable, a bothness we go to the movies to get a couple hours’ fucking relief from. A movie that requires that these features of ourselves and the world not be dreamed away or judges away or massaged away but acknowledged, and not just acknowledged but drawn upon in our emotional relationship to the heroine herself—this movie is going to make us feel uncomfortable, pissed off; we’re going to feel, in Premiere magazine’s own head editor’s word, “Betrayed.”

I am not suggesting that Lynch entirely succeeded at the project he set for himself in Fire Walk with Me. (He didn’t.) What I am suggesting is that the withering critical reception the movie received (this movie, whose director’s previous film had won a Palme d’Or, was booed at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival) had less to do with its failing in the project than with its attempting it at all. And I am suggesting that if Lost Highway gets similarly savaged—or, worse, ignored—by the American art-assessment machine of which Premiere magazine is a wonderful working part, you might want to keep all this in mind.

Premiere Magazine, 1995

42. (Not even the Lynch-crazy French film pundits who’ve made his movies subject of more than two dozen essays in Cahiers du Cinema— the French apparently regard Lynch as God, though the fact they also regard Jerry Lewis as God might salt the compliment a bit…)

43. (Q.v. Baron Harkonen’s “cardiac rape” of the servant boy in Dune’s first act)

44. Here’s one reason why Lynch’s characters have this weird opacity about them, a narcotized over-earnestness that’s reminiscent of lead-poisoned kids in Midwestern trailer parks. The truth is that Lynch needs his characters stolid to the point of retardation; otherwise they’d be doing all this ironic eyebrow-raising and finger-steepling about the overt symbolism of what’s going on, which is the very last thing he wants his characters doing.

45. Lynch did a one-and-a-half-gainer into this pitfall in Wild at Heart, which is one reason the movie comes off so pomo-cute, another being the ironic intertextual self-consciousness (q.v. Wizard of Oz, Fugitive Kind) that Lynch’s better Expressionist movies have mostly avoided.

46. (=Master of Fine Arts Program, which is usually a two-year thing for graduate students who want to write fiction and poetry professionally)

47. (I’m hoping now in retrospect this wasn’t something Lynch’s ex-wife did…)

48. (E.g.: Kathleen Murphy, Tom Carson, Steve Erickson, Laurent Varchaud)

49. This critical two-step, a blend of New Criticism and pop pyschology, might be termed the Unintentional Fallacy.

50. (I.e. “in-spired,”=“affected, guided, aroused by divine influence,” from the Latin inpsirare, “breathed into”)

51. It’s possible to decode Lynch’s fetish for floating/flying entities—witches on broomsticks, sprites and fairies and Good Witches, angels dangling overhead—along these lines. Likewise his use of robins=Light in BV and owl=Darkness in TP: the whole point of these animals is that they’re mobile.

52. (With the exception of Dune, in which the good and bad guys practically wear color-coded hats—but Dune wasn’t really Lynch’s film anyway)

53. This sort of interpretation informed most of the positive reviews of both Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks.

54. (Which most admiring critics did—the quotation is from a 1/90 piece on Lynch in the New York Times Magazine)

55. (Not to mention ignoring the fact that Frances Bay, as Jeffrey’s Aunt Barbara, standing right next to Jeffrey and Sandy at the window and making an icky-face at the robin and saying “Who could eat a bug?” Then—as far as I can tell, and I’ve seen the movie like eight times—proceeds to PUT A BUG IN HER MOUTH. Or at least if it’s not a bug she puts in her mouth it’s a tidbit of sufficiently buggy-looking to let you be sure Lynch means something by having her do it right after she’s criticized the robin for its diet. (Friends I’ve surveyed are evenly split on whether Aunt Barbara eats a bug in this scene—have a look for yourself.))

56. As, to be honest, is a part of us, the audience. Excited, I mean. And Lynch clearly sets the rape scene up to be both horrifying and exciting. This is why the colors are so lush and the mise en scene is so detailed and sensual, why the camera lingers on the rape, fetishizes it: not because Lynch is sickly or naively excited by the scene but because he—like us—is humanly, complexly excited by the scene. The camera’s ogling is designed to implicate Frank and Jeffrey and the director and the audience all at the same time.

57. (Prematurely!)

58. I don’t think it’s an accident that of the grad-school friends I first say Blue Velvet with in 1986, the two who were most disturbed by the movie—the two who said they felt like either the movie was really sick or they were really sick or both they and the movie were really sick, the two who acknowledged the movie’s artistic power but declared that as God was their witness you’d never catch them sitting through that particular sickness-fest again—were both male, nor that both singled out Frank’s smiling slowly while pinching Dorothy’s nipple and looking out past Wall 4 and saying “You’re like me” as possibly the creepiest and least pleasant moment in their personal moviegoing history.

59. Worse, actually. Like most storytellers who use mystery as a structural device and not a thematic device, Lynch is way better at deepening and complicating mysteries than he is at wrapping them up. And the series’ second season showed that he was aware of this and that it was making him really nervous. By its thirtieth episode the show had degenerated into tics and shticks and mannerisms and red herrings, and part of the explanation for this was that Lynch was trying to divert our attention from the fact that he really had no idea how to wrap the central murder case up. Part of the reason I actually preferred Twin Peaks’s second season to its first was the fascinating spectacle of watching a narrative structure disintegrate and a narrative artist freeze up and try to shuck and jive when the plot reached a point where his own weaknesses as an artist were going to be exposed (just imagine the fear: this disintegration was happening on national TV).

60. This is inarguable, axiomatic. In fact what’s striking about most U.S. mystery and suspense and crime and horror films isn’t these films’ escalating violence but their enduring and fanatical allegiance to moral verities that come right out of the nursery: the virtuous heroine will not be serial-killed; the honest cop, who will not know his partner is corrupt until it’s too late to keep the partner from getting the drop on him, will nevertheless somehow turn the tables and kill the partner in a wrenching confrontation; the predator stalking the hero/hero’s family will, no matter how rational and ingenious he’s been in his stalking tactics throughout the film, nevertheless turn into a raging lunatic at the end and will mount a suicidal frontal assault; etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. The truth is that a major component of the felt suspense in contemporary U.S. suspense movies concerns how the filmmaker is going to manipulate various plot and character elements in order to engineer the required massage of our moral certainties. This is why the discomfort we feel at “suspense” movies is perceived as a pleasant discomfort. And this is why, when a filmmaker fails to wrap his product up in the appropriate verity-confirming fashion, we feel not disinterest or even offense but anger, a sense of betrayal—we feel that an unspoken but very important covenant has been violated.

61. (Not to mention for being (from various reviews) “overwrought,” “incoherent,” “too much”)

#i hope this post isnt horrifyingly long and doesnt annoy anymore#im gonna tag it#long post#cause i know some people filter that tag#BUT THIS IS SO FREAKING AMAZING AND ABOUT THE ESSENCE OF FILM AND ART IN GENERAL#and is a great example of how wallace was able to write in a way that makes the reader feel more intelligent rather than intimidated#by his intelligence#david foster wallace#david lynch#a supposedly fun thing i'll never do again

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There is sometimes a fine line between genius and failure and Terrence Malick has certainly been both sides of it in recent years. But at his best he is able to see (and show) the presence of God in nature and in the hidden lives of ordinary people - so we may in turn be sometimes blessed by seeing the presence of God in his creativity portrayed on the big screen. Whilst I understand how for some this slow, three hour film would be boring and/or pretentious - for me it became a meditation which was a highly moving and ultimately spiritual experience – more so than many church services I attend! Of course it also engendered conversations afterwards about how people of faith should balance their loyalty to God with the practicalities of living in a broken world (as the lead character risks his life by refusing to swear loyalty to Hitler) but for me it was the texture and depth of A Hidden Life as a whole which not just lifted it above its filmic flaws but lifted me beyond myself so as to make it a transcendent experience. This is what film at is best is able to do, and why the cinema is my second church. . . . . . . . . . . . #terrencemalick #filmsandfaith #godintheordinary #church #spiritual #nazi #nazis #hitler #ahiddenlife #ahiddenlifemovie #spirituality #god #martyr #transcendence #transcendent #cinema #slowcinema #meditation #prayer #cineaste #cinephile #cinephilecommunity #cinephiles #cinéaste #film #faith #filmandtheology https://www.instagram.com/p/B7tE_j5lsEC/?igshid=177mtwosjc7ce

#terrencemalick#filmsandfaith#godintheordinary#church#spiritual#nazi#nazis#hitler#ahiddenlife#ahiddenlifemovie#spirituality#god#martyr#transcendence#transcendent#cinema#slowcinema#meditation#prayer#cineaste#cinephile#cinephilecommunity#cinephiles#cinéaste#film#faith#filmandtheology

0 notes

Photo

03-08-2017

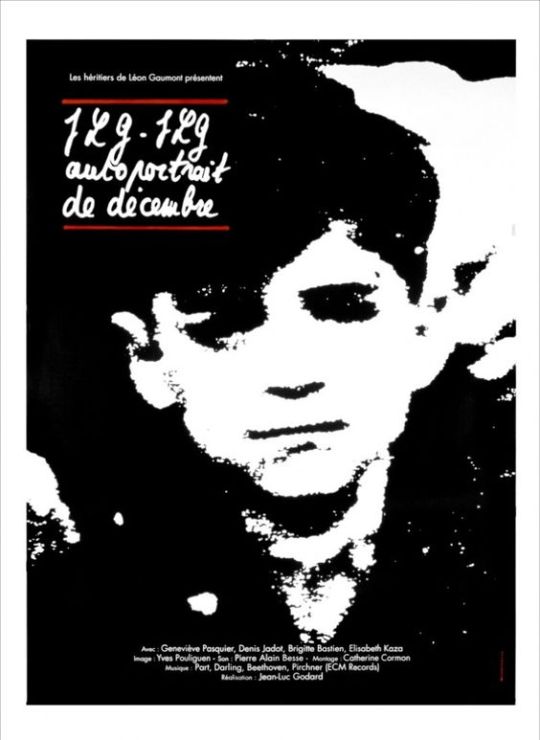

JLG/JLG - Autoportrait De Décembre (1994)

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0110173/

I have watched my share of Jean-Luc Godard films, both narrative and experimental (or video essays). I liked some them, Bande à Part (1964) for instance, and I could even enjoy his experimental Adieu Au Langage (2014), despite both of them being very, obviously, Godardesque, or pretentious, self-involved and pseudo-philosophical. I have mostly had issues watching his films though, and my appreciation for the cineast has reached new lows after watching JLG/JLG - Autoportrait De Décembre (English title: JLG/JLG - Self-Portrait In December). This is the most self-indulgent and narcissistic piece of work by a man who considers himself a legend. It is almost dangerous.

I don't need a narrative to understand a film, or to watch it, but I certainly don't need this either. At one point I saw a reflection of myself in the screen as I was watching this movie, and I felt sorry for myself. Sorry that I came to a point in my life that I was watching this. We are presented with quotes that come seemingly out of the blue, uttered by a heavily breathing (why precisely I do not know) Godard himself: ’my soul tripped over my body’, or ’Jeannot, that rhymes with stereo’. Top-level amateur rhymes. Is Godard serious? Or is this a joke? Making fun of the countless cinephiles who adore him?

Godard has some interesting things to say, especially when the movie nears its end. The sequence with the blind editor for instance is pretty good, but mostly this is us watching Godard, showing us his book collection (paperback mostly), how well-read he is, how smart he is. ’Je suis une légende’, he writes, get out of here.

3

#jean-luc godard#jlg#jlg/jlg#adieu au langage#bande a part#bande à part#jlg/jlg - autoportrait de décembre#jlg/jlg - autoportrait de decembre#jlg/jlg - self-portrait in december

0 notes