#salishan languages

Text

Why is it so impossible to find something as basic as what Pacific Madrones were called in any of the dozens of Salishan languages where the damn tree is indigenous.

Finally found it via the glossary section of a txʷəlšucid (twulshootseed aka Puyallup Tribal language) program website after much variations on searches and also a Lummi Language Vocabulary by a 19th century ethnobotanist: ɡʷuƛ̕əc (and the anglified version: kō-kwéltsh).

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

That combining apostrophe above the letters is hell to find fonts for lemme tell ya...

49 notes

·

View notes

Note

Dictionary.com | Meanings & Definitions of English Words

Any of the words in here?

... no.

#it means large powerful or impressive#and as with most 'funny' words#is an english misspelling of an indigenous word#this case it comes from Salishan languages in the pacific northwest and sounds more like skwekwem. I think#ask#mackthecheese

1 note

·

View note

Text

something something american necropolitics the tillamook county creamery association found online on tillamook dot com that sells many dairy products in the united states under the brand name tillamook has no relationship and makes no acknowledgement of the tillamook people from whom it get its name. the name comes from the chinook translation of the people of nehalem. early contact with european sailing ships is dated to the 1770s. in 1805 lewis and clark's "discovery" expedition noted at the time that many large villages had been depopulated by pandemics and many adults had smallpox scars. this followed a period of fur trading with the involvement of hudson bay corporation. in 1850, the us govt passed the oregon donation land act, announcing over 2,500,000 acres of land as available for settlers to seize, which happened in patterns whose violence mirrors that of the continent. there was no treaty. in 1907, the tribe sued and was paid 23,500 dollars for the land the us govt has seized from them when it forced them onto the siletz reservation. the tillamook language is a salishan language that lost its last fluent speaker in 1970. many descendants are considered part of the confederated tribes of siletz. other nehalem are part of the unrecognized clatsop nehalem confederated tribes. the nehalem-tillamook were also socially and economically integrated with the clatsop peoples. today the town of tillamook has a population that is only 1.5% native american. the modern day corporation started as a settler coop created in 1909. it is the 48th largest dairy processor in north america and posted $1 billion in sales in 2021.

#sometimes i see an interesting word or name in the us and inevitably its history is something like this#but i hadn't seen an actually brand named after a tribe yet that made no acknowledgement of it#pnw#<- idk local history tag

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

We all can understand that Esperanto's system of using word-final vowels to denote word classes is not especially naturalistic and frankly is pretty clunky in many regards. However, there do appear to exist languages in numerous places around the world which exhibit some segmental correlates of word-class. Here's a list of those that I'm aware of off the top of my head.

Yoruba (and I'm guessing this is true of Kwa more broadly) appears to overwhelmingly have vowel-initial nouns in native vocabulary. This seems to tie in with a trend towards deriving nouns from consonant-initial verb roots using V-prefixes, as well as perhaps being a relic of a previous noun class system (more on that below).

Salishan languages (outside of Bella Coola) generally show an s- prefix, even on seeming root nouns, in part doubtless to do with it being a nominalising prefix and thus kinda essential in an omnipredicative language.

A number of Oceanic languages, mostly in Melanesia, have either vowel-initial or n-initial nouns from univerbation of one of the Proto-Oceanic articles (*qV and *na respectively). Often the distribution seems to fall along semantic lines, with *qi for humans and proper nouns and *na everything else, though some languages divide it differently, e.g. Torres-Banks, where *na has specifically ended up as an inalienable marker, though there it is still kind of an article. Notably, even in languages where this correlation does not hold for the majority of nouns, some 'article accretion' as François terms it often still occurs

Moskona, in a curious parallel to the Oceanic system, has native alienable nouns begin with m- and inalienable ones with a vowel, or rather the root begins with vowel to which possessor prefixes are added. No clues as to the etymology.

To this we might add systems where noun class also plays a role. For instance, in Berber languages masculine nouns seem to usually begin with a vowel, with a t-...-t circumfix for feminines, e.g. Amazigh 'Berber people' → Tamazight 'Berber language' (though for non-Tuareg varieties I think vowel syncope obscures this a little?). Similarly, some Bantu noun-class systems such as those of isiZulu have a vocalic 'augment' to their noun class prefixes which is basically an echo vowel of the prefix, which I suspect is related to what's going on in Yoruba, especially if Niger-Congo is a thing.

Any other examples you're aware of feel free to add, as I'm wondering if this might be a good thing to do a paper on sometime.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Hawks’s Name

So. I got curious about what Two Hawks’s name would be in his own language. I mean, I’m curious about what all of Kaya’s contemporaries would be named, but a few weeks ago I got hit with a strong desire to look into Two Hawks’s name specifically while doing research on the Salish nations.

As Two Hawks lives in the general Washington area, he would liikely use the Kalispel or Spokane dialect of his language. In both Kalispel and Spokane, “Esel” means “two,” but it was a bit hard to find a word for “hawk” or “hawks.”

So I ended up on native-languages.org, a non-profit organization site dedicated to the survival of Native languages. They have a specific page in which you can email their experts and request to know a word in exchange for a $10 donation. So I did send them a request, telling them that a character in a book I liked was named “Two Hawks” in the Salish Kalispel-Spokane language and I would like to know what his name would be.

They actually did respond to it, which I’m very excited about! I’m posting the email they sent to me below w/ a transcription under it. (Note: I wasn’t sure if Ms Redish’s email was from the site or personal? So to be safe I blacked it out). The tl;dr is there’s three possibilities for Two Hawks’s name, which is very exciting!

Thanks for taking part in our fundraiser!

Well, the Salish word for "Two" is "esel," but there are several different words for hawks in Salish. A fish hawk or osprey is c'ixʷc'xʷ. It's very typical of Salish words to be eye-popping tongue-twisters like this, the Salishan languages are considered to be among the most difficult in the world for English speakers to pronounce. The c' is pronounced like the "ts" in "cats" but with a clicking sound, and the "xʷ" sounds a bit like the "hw" sound you might make blowing out a candle. So c'ixʷc'xʷ is pronounced a little like tseets only with extra clicking and guttural blowing sounds.

A red-tailed hawk is c'lc'lšmu, which is easier to pronounce, it sounds a little like chull-chull-shmoo only with clicks.

A sparrow hawk or falcon is the easiest to say, Aatat (pronounced ah-tot.)

So this character's name could have been something like Esel C'ixʷc'xʷ, Esel C'lc'lšmu, or Esel Aatat.

Hope that is interesting to you, have a good day!

Laura Redish

Native Languages of the Americas

Everyone say thank you Laura Redish!!

What do you think is most likely to be Two Hawks’s name? Personally I think Esel C'lc'lšmu is the most likely, as I feel the translated name would have reflected it if he was named after an osprey or falcon, but any of them are possible.

#american girl#american girl dolls#american girls#kaya'aton'my#two hawks#beforever#salish#1764#native languages#mine

177 notes

·

View notes

Text

I spent a lot of my childhood growing up on the rez. And at home, we spoke some Salish in our day-to-day dealings. Not much, just a word or phrase here and there (that I've mostly forgotten).

One of those phrases was "Q'lal'ŝ", which just means "suppertime", or something similar. And it was how my family would call everybody to the table for a meal. Mom would say "go get your siblings for supper" and so we would just holler "q'lal'ŝ!!" down the hallway.

But as a kid, I didn't know that we were speaking Salish, a dead language that nobody really speaks anymore. I just thought that was a normal regular American thing to do. And so like, even when staying at a friend's house, that's how I would call them to supper.

Nobody pointed it out to me until middle school, when my friend Tyler's mom very politely asked me "what the HELL did you just say?", and I found out that, no, in fact. The average American does not sprinkle phrases in upper Salishan dialects into their day-to-day vernacular.

#jackieposting#gotta sprinkle some nativeposting in every now and again otherwise people will assume i am white#just a little linguistic lesson for the hoes#don't remember much salish#plus there's so many different dialects#this okay to reblog btw#all of my funny stories selfies and photography okay to reblog

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

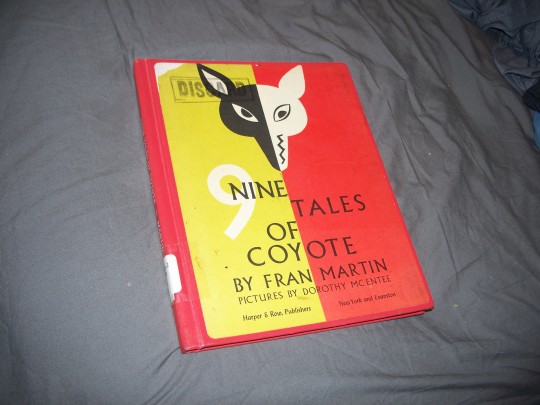

the yardsale gods were tossing me tasty crumbs

So here is what I came away with after 3 hours of driving around through HOA neighborhoods and the ruralities...

Tom Thumb steel toy cash register, because heavy things with sharp edges are what adults gave kids to play with in the 1950s-1960s, and each of the keys and price slips work! Only issue is the cash drawer -- the only plastic part on the entire toy beside the keycaps -- has a small chunk taken out of the right bottom side (it’s vaguely visible in the photo), but when I can get for $5 what the antique stores sell for $50...

Nine Tales of Coyote, “by” Fran Martin (actually by centuries-old Native Americans), for $1. The writer of the book got her stories from a Nez Perce storyteller and also were derived from two collections of Salishan and Sahaptin tales, published in 1917 and 1891. Since I was raised on the Yakama Reservation and the elders speak Sahaptin, this has some relevance to me. I’ve only heard a couple of stories about the trickster Coyote (his actual name is Speel-yi) so this will let me catch up on things, plus I’m sure my best friend’s mother who is an elder and for years taught tribal preschoolers the language would appreciate it.

Atari 2600 joystick for $1. Because you can never have too many.

A mess of Perler beads and grids, $6 after some haggling. Because she had them and wanted to get rid of them but knew she’d invested a bunch of money into all this so wanted to recoop the cost of at least one set.

The real finds of the day were two hand drills. The smaller one was $1 at one yardsale and moved great in the field, plus has 7 bits in the handle, so it was a no-brainer. The larger with the shoulder brace was TWENTY-FIVE CENTS and worked a little sporadic, so just needed a good dousing with WD-40 and an adjustment to one collet to get the gear teeth to mesh without slipping. I am super-happy to have found these for ridiculously low prices.

Bonus image of something I didn’t buy, which was at the same garage sale as the smaller drill:

The ice man cometh! This is a pair of tongs used to carry a block of ice before refrigeration was a thing, and one thing I’d never expected to see for $4.

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ingush Grammar

[Ingush Grammar. Johanna Nichols. First Edition: March 2011. University of California Press. Series: UC Publications in Linguistics. Pages: 830. Trim Size: 7 x 10 inches. Illustrations: 1 map. Paperback. ISBN: 9780520098770]

Readers of my book reviews cannot help but notice my interest in – nay, my fascination with – linguistics and languages. I am no stranger to Professor Nichols’s work: I read her award-winning treatise Linguistic Diversity in Time and Space a few years ago and was captivated by her command of language reconstruction principles. Recently, it came to my attention that there might (in principle) be a call for persons to assist in national security-related activities who are fluent in, or at least familiar with, the Northeast Caucasian languages, especially Chechen and Dagestani. The language discussed here, Ingush, is a closely-related language with a relatively high degree of mutual intelligibility with Chechen, Dagestani and Baltsi. Since I couldn’t find a suitable book from which to learn Chechen, I thought I’d check this tidy little volume out.

“Tidy” is not the correct word for this work. It tips the scales at almost 800 pages. However, it is an undeniable tour-de-force of scholarship in the documenting of a comparatively obscure language. Prof. Nichols herself acknowledges that this tome is the culmination of about 30 years of work with Ingush, at least ten of which were spent in the homeland of the language itself, a region now known as Ingushetia in southern Russia adjacent to the Republic of Georgia and Chechnya.

The Northeast Caucasian languages are a small primary language family spoken almost exclusively in the region between the Republic of Georgia and the north end of the Caspian Sea. Significant cities in this region are Ongusht (whence the name Ingush), Groznyy (the capital of Chechnya) and Makhachkala (the capital of Dagestan). Though these languages share many features with Georgian (known as Kartuli to its speakers) and the similarly-named Northwest Caucasian languages (examples are Abkhazi and Cherkessian), they are not, in fact, related to them in any meaningful way. This may seem surprising when one looks at a map of the region. The area covered by these three language groups (Georgian is part of its own tiny language family called the Kartulian languages) is fairly small. However, the area is peppered with mountain ranges that have carved it up geographically to a point where very ancient steppe peoples had settled in individual valleys and had no direct contact with even neighboring valleys for centuries. Little wonder, then, that language families developed independently from a still-more-ancient proto-language (as yet unidentified or classified).

Ingush, as alluded to in the previous paragraph, was named after a prominent community in its sprachbund, or speaking area. Ingush people do not use this term, referring to their language as vai mott (our language) or, if speaking to non-Ingush speakers, vai neaxa mott (our people’s language). Given that the homeland for this language has at least three well-defined geographic zones (alpine highlands, piedmont, and plains), it is not surprising that various dialects of Ingush have emerged. All of these dialects are highly mutually intelligible, far from any objective criteria that would categorize them as distinct languages in their own right.

Nichols herself, in the introductory material, lists Ingush as one of the most morphologically complex languages in her experience, outstripping even daunting native American languages like Lakhota (a Siouan language of the northern Great Plains) and Halkomelem (a Salishan language from the Pacific Northwest in the USA). Ingush has unusually large inventories of elements (phonemes, etc.), a high degree of inflectional synthesis in the verb (this is similar to some native American languages, especially the Athapaskan group) and a variety of categories of words, many of which do not have an analogue in English or any Indo-European language. She comments that this might go some way toward explaining why this book took 30 years to produce!

Since the volume is so detailed, I will simply summarize my observations of its style and completeness. I confess that I haven’t actually read the entire volume – I’ve probably read about 150 pages, or nearly 20% of it all told – but I have dipped into it in various places along its length to see what it was all about. It is impossible for me to imagine that Prof Nichols missed anything; every conceivable component of Ingush seems to be covered here. The book has 35 major sections, any one of which is worthy of at least a semester-long course of study (for the subject itself, not necessarily for Ingush per se). Her writing tone and style strike an admirable balance between being very scholarly (it certainly is that) and yet being profoundly informative to a non-specialist like myself who is also not a trained linguist.

The best affirmation I can make of this book is that it is quite possibly the best template for any field linguist to follow when documenting and characterizing a language. This is certainly true for someone working with an Endangered language, of which there are literally thousands still being spoken (some just barely) in the world today. The level of commitment Prof Nichols has brought to bear on this work seems nothing short of miraculous.

This is definitely not a book for just anyone. Like attempting to read all of Proust in the original French while not actually speaking French, a true appreciation of this book requires enormous patience and strong memory skills. Prof Nichols refers to sections back and forth across the book, of necessity since linguistic elements do not exist in a vacuum. That said, to truly appreciate the scope and even grandeur of this volume will command great mental agility and focus. For anyone who is up to the challenge, I say, “Good luck – and enjoy!” Even if you never speak Ingush or travel to that part of the world, this book will teach you something useful, edifying, and mind-expanding.

[Photo credits with thanks to : Book cover © 2011 University of California Press / Portrait © 2012 Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin]

Kevin Gillette

Words Across Time

28 September 2022

wordsacrosstime

#Kevin Gillette#Ingush Grammar#Words Across Time#wordsacrosstime#September 2022#University of California Press#Johanna Nichols#Linguistics.#Language Reconstruction#Northeast Caucasian Languages#Chechen#Dagestani#Ingush#Baltsi#Ingushetia#Southern Russia#Republic of Georgia#Chechnya#Caspian Sea#Ongusht#Groznyy#Makhachkala#Dagestan#Kartuli#Northwest Caucasian Languages#Kartulian#vai mott#Lakhota#Siouan#Halkomelem

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

I don’t think that word from Sasquatch comes from the salish language (flathead nation, it’s the only language that is thee salish language), but I think it did come from a different salishan language, Nlaka'pamuctsin (Thompson River). “Ogopogo” is also a syilx spirit we call nx̌ax̌aitkʷ. Dhfjgk I hope this doesn’t come across as rude, I really appreciate the time you took to make such a big list!!! Just a few lil corrections

No I appreciate it!! Ty :)

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

countries most closely correlated with a single language family (roughly ranked)

Japan, Japonic

Georgia, Kartvelian

Central African Republic, Ubangian (controversial classification as Niger-Congo)

Mongolian, Mongolic (point of diversity is in Mongolia, but most of the branches/subbranches are centered in Russia or China)

Australia, Pama-Nyungan (pre-contact; non-Pama-Nyungan was historically only spoken in a small part of the country)

Indonesia, Austronesian (while Taiwan is clearly the point of diversity for Austronesian, and there are several branches not spoken in Indonesia, i.e., Palauan, Chamorro, Polynesian, various Philippine branches... and there are Papuan languages spoken in Indonesia, Indonesia contains most Austronesian speakers and contains many Malayo-Polynesian branches)

India, Dravidian (~20% of the country speaks a Dravidian language, and the only language centered outside India is Brahui)

Thailand, Kra-Dai (~60% of speakers of languages in this family are Thai speakers, and 96% of Thailand speaks it as L1 or L2)

Sudan, Nilo-Saharan (This may be one of the most arbitrary. Assuming settlement of native ethnic groups was similar before Arab settlement, almost everyone in what is now Sudan spoke a language classified as Nilo-Saharan. Of course, Nilo-Saharan is a very controversial language family. Also, there were [controversial?] Niger-Congo speakers in the Kordofan/Nuba Mountains, and Beja on the Red Sea. Several few Nilo-Saharan branches aren't spoken in Sudan at all; Kunama, Nara, Surmic, Songhay and Kuliak. A few are barely spoken in the country, like Nilotic or Maban. There are so many holes to poke in this, but if you assumed the demographics of non-Arabs in the country would be directly extrapolated to 100% pre-contact, I think it would make the top 15 in the world in correlation between language family and political borders)

Korea, Koreanic (if it was a unified country)

Bougainville, Northern Bougainville & Southern Bougainville (It's hard to determine speaker counts for these languages; while the largest language in the hypothetical future country is Austronesian, these two Papuan [non-Austronesian] language families dominate the main island)

Guatemala, Mayan (Mamean, K'iche'an and Q'anjob'alan are centered in the country. Yucatecan, Huastecan and Ch'olan-Tzeltalan are not.)

Nicaragua, Misumalpan

Bolivia, Aymara (there are many language families with members in Bolivia, and isolates in Bolivia, but... about 80% of speakers are in Bolivia, and about 40% of indigenous language speakers in Bolivia speak Aymara)

Paraguay, Tupi-Guarani (While there are many minor Tupi-Guarani languages spoken outside of Paraguay, and several other language families and isolates spoken in Paraguay, the majority of people in Paraguay speak Guarani, there are still monolingual speakers, etc.)

Panama, Chibchan (pre-contact)

Uruguay, Charruan (pre-contact)

Namibia, Khoe-Kwadi (Kwadi was centered in Angola and Kalahari Khoe is centered in Botswana, but the majority of speakers of a Khoe language are Khoekhoe speakers, and 11% of people in Namibia speak Khoekhoe. Certainly not as close a correlation as in many of these countries)

East Timor, Timor-Alor-Pantar

In terms of US states, the following stick out:

Oklahoma, Caddoan (pre-contact; I know nomadic groups can be hard to pin down, apply that disclaimer to some of the items above, too)

New York, Iroquoian (there were also Algonquian languages spoken in New York, and Tuscarora, Nottoway and Cherokee were spoken further south, while Huron-Wyandot was spoken in Canada... please note that Lake Iroquoian was not the point of diversity for the family. This situation is a lot like Mongolia, with other branches being spoken outside of the state, and the sister branch, Huron-Wyandot, being spoken elsewhere, too)

Washington, Salishan (it's bizarre that anywhere on the west coast could be very closely correlated to a single language family, given the west coast is overall the most diverse area in North America, linguistically, by far. There are Chimakuan languages and a Wakashan language, Makah, spoken at the northern end of the Olympic peninsula. There are Chinookan and Sahaptian/Plateau Penutian languages spoken at the southern and eastern edges of the state. Kwalhoquia-Tlatskanai is a subbranch of Northern Athabaskan spoken in the state, too. And of course, Bella Coola and Tillamook are divergent branches of the family spoken outside of Washington, and there are Coast Salish languages in BC; the Interior Salish area also extends into BC, Idaho and Montana. However, probably at least 80% of land in Washington was settled by Salishan peoples at the time of contact)

Florida, Timucua

A lot of this is really hard to quantify, but it's an interesting overlap of figures to consider.

0 notes

Text

The Salish Language Dictionary is a valuable online resource that documents and aids in the preservation of numerous endangered Salishan languages native to the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. Central Salish languages such as Lushootseed, Nisqually-Puyallup, and Southern Puget Sound Salish are included, as are Northern Coast Salish languages such as Straits Salish. It contains thousands of Salish vocabulary phrases with headwords, parts of speech, meanings, and example sentences. There are also audio recordings of native speakers reciting numerous words. The purpose of the dictionary is to help language revitalization by gathering and organizing Salish language data into one publicly accessible database. It is a great resource for linguists, anthropologists, educators, and Salish community members who want to study or teach their ancestral dialects.

#salish language dictionary to date#online buy salish dictionary in usa#salish language dictionary buy online#salish language dictionary usa

0 notes

Text

Morris Swadesh, "Internal Relationships in Salish", International Journal of American Linguistics, year 1950, volume #16, pages 157-167.

Morris Swadesh, “The Origin and Diversification of Language”, 1968, PART TWO (II) was the topic of an earlier blog post.

Here I present: Morris Swadesh’, “Salish Internal Relationships”, International Journal of American Linguistics, year 1950, volume #16, pages 157-167.

The map BELOW shows where the Salish family (or called Salishan) is located in North America. This is a family of…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

I feel like the cobra of a snake charmer when listening to Arabian or Arabian-themed music, what with the drums, the flutes, the stringed instruments... I just wanna like, vibe while slithering from side to side, or fall asleep in my basket, while listening to this stuff. Or maybe ride a camel in a merchant caravan. That kind of Ali Baba-type stuff, y'know?

#I don't even know who Ali Baba is#is he one of the characters from that fuckin. the fuckin uh.#what was it fuckin called#1000 nights or some shit like that#??#idek#makes me feel weird that I barely known anything about islam#and the only arabic i know is 'islam' 'muslim' 'hijab(i)' and 'al-yahud'#also because i live in a desert#even though the desert i live in is the columbia plateau#this isn't even an arabic desert. this isn't a desert in 'the old world'#this desert is a salishan and sahaptin desert#in territory occupied by the colonialist usa#camels don't live here. some muslims live here but aren't the majority.#and english spanish russian chinese languages and probably nahua are the best ones to know here#in terms of the amounts of speakers#and yet even so. deserts just feel fundamentally arabic to me#i've never even been to arabia and i'm literally a white american. what the fuck would i know about arabia.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nonconcatenative morphology

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

It may involve apophony (ablaut), transfixation (vowel templates inserted into consonantal roots), reduplication, tone/stress changes, or truncation.

It is very developed in Semitic, Berber, and Chadic branches of Afro-Asiatic. It also occurs extensively among other language families: Nilo-Saharan, Northeast Caucasian, Na-Dene, Salishan and the isolate Seri (in Mexico).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonconcatenative_morphology

#languages#linguistics#language maps#linguistic maps#morphology#grammar#Arabic#Berber#Maltese#Navajo#Athabaskan#Salishan#Chechen#Hausa

386 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bigfoot

Thousands of people have claimed to have seen a Bigfoot, which is most often described as a large, muscular, bipedal ape-like creature, roughly 1.8–2.7 metres (6–9 ft), and covered in black, dark brown, or dark reddish hair. Some descriptions have the creatures standing as tall as 3.0–4.6 metres (10–15 ft). A pungent, foul smelling odor is sometimes associated with reports of the creatures, commonly described as similar to rotten eggs or skunk.

The face of a Bigfoot is often described as human-like, with a flat nose and visible lips. Common descriptions also include broad shoulders, no visible neck, and long arms. The eyes are commonly described as dark in color and have been alleged to "glow" yellow or red at night. However, eyeshine is not present in humans or any known great ape.

The enormous footprints for which the creature is named are claimed to be as large as 610 millimetres (24 in) long and 200 millimetres (8 in) wide.

According to anthropologist David Daegling, Bigfoot legends existed long before there was a single name for the creature. These stories differed in their details both regionally and between families in the same community.

On the Tule River Indian Reservation in California, petroglyphs created by a group of Yokuts at a site called Painted Rock are alleged by some to depict a group of Bigfoots called "the Family". The local tribespeople call the largest of the glyphs "Hairy Man" and they are estimated to be between 500 and 1000 years old.

Ecologist Robert Pyle argues that most cultures have accounts of human-like giants in their folk history, expressing a need for "some larger-than-life creature". Each language had its own name for the creature featured in the local version of such legends. Many names meant something along the lines of "wild man" or "hairy man", although other names described common actions that it was said to perform, such as eating clams or shaking trees. Chief Mischelle of the Nlaka'pamux at Lytton, British Columbia told such a story to Charles Hill-Tout in 1898; he named the creature by a Salishan variant meaning "the benign-faced-one".

Members of the Lummi tell tales about Ts'emekwes, the local version of Bigfoot. The stories are similar to each other in the general descriptions of Ts'emekwes, but details differed among various family accounts concerning the creature's diet and activities. Some regional versions tell of more threatening creatures: the stiyaha or kwi-kwiyai were a nocturnal race, and children were warned against saying the names so that the "monsters" would not come and carry them off to be killed. The Iroquois tell of an aggressive, hair covered giant with rock-hard skin known as the Ot ne yar heh or "Stone Giant", more commonly referred to as the Genoskwa. In 1847, Paul Kane reported stories by the natives about skoocooms, a race of cannibalistic wild men living on the peak of Mount St. Helens in southern Washington state. Also related to this area was an alleged incident in 1924 in which a violent encounter between a group of miners and a group of "ape-men" occurred. These allegations were reported in the July 16, 1924, issue of The Oregonian and have become a popular piece of Bigfoot lore, with the area now being referred to as Ape Canyon. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt, in his 1893 book, The Wilderness Hunter, writes of a story he was told by an elderly mountain man named Bauman in which a foul smelling, bipedal creature ransacked his beaver trapping camp, stalked him, and later became hostile when it fatally broke his companion's neck in the wilderness near the Idaho-Montana border. Roosevelt notes that Bauman appeared fearful while telling the story, but attributed the trapper's folkloric German ancestry to have potentially influenced him.

Less-menacing versions have also been recorded, such as one by Reverend Elkanah Walker from 1840. Walker was a Protestant missionary who recorded stories of giants among the natives living near Spokane, Washington. These giants were said to live on and around the peaks of the nearby mountains, stealing salmon from the fishermen's nets.

In the 1920s, Indian Affairs Agent J. W. Burns compiled local stories and published them in a series of Canadian newspaper articles. They were accounts told to him by the Sts'Ailes people of Chehalis and others. The Sts'Ailes and other regional tribes maintained that the creatures were real and they were offended by people telling them that the figures were legendary. According to Sts'Ailes accounts, the creatures preferred to avoid white men and spoke the Lillooet language of the people at Port Douglas, British Columbia at the head of Harrison Lake. These accounts were published again in 1940. Burns borrowed the term Sasquatch from the Halkomelem sásq'ec and used it in his articles to describe a hypothetical single type of creature as portrayed in the local stories.

Some Bigfoot researchers claim that Bigfoot supposedly throws rocks as territorial displays and for communication. Other claims include wood knocking behavior theorized to be communicative. Skeptics argue that these behaviors are easily hoaxed. Additionally, structures of broken and twisted foliage seemingly placed in specific areas have been attributed by some to Bigfoot behavior. In some reports, lodgepole pine and other small trees have been observed bent, uprooted, or stacked in patterns such as weaved and crisscrossed, leading some to theorize that they are potential territorial markings. Some instances have also included entire deer skeletons being suspended high in trees. In Washington state, a team of amateur Bigfoot researchers called the Olympic Project claimed to have discovered a collection of nests, and they had primatologists study them, with the conclusion being that they appear to have been created by a primate.

Many alleged sightings are reported to occur at night leading to some speculations that the creatures may possess nocturnal tendencies. However, mainstream science largely disputes this claim as all known apes, including humans, are diurnal with only lesser primates exhibiting nocturnality. Most anecdotal sightings of Bigfoot indicate the creatures being observed as solitary, although some reports have described groups being allegedly observed together.

Alleged vocalizations such as howls, moans, grunts, whistles, and even a form of supposed language have been reported. Some of these alleged vocalization recordings have been analyzed by individuals such as retired U.S. Navy cryptologic linguist Scott Nelson. He analyzed audio recordings from the early 1970s said to be recorded in the Sierra Nevada mountains dubbed the "Sierra Sounds" and stated, "It is definitely a language, it is definitely not human in origin, and it could not have been faked". Les Stroud has spoken of a strange vocalization he heard in the wilderness while filming Survivorman that he stated sounded primate in origin. Some researchers claim Bigfoots can produce infrasound. Others argue that the source of the sounds attributed to Bigfoot are either hoaxes, anthropomorphization, or likely misidentified and produced by known animals such as owl, wolf, coyote, and fox.

The concept of what Bigfoot would consume for sustenance is a debated issue. Most mainstream scientists maintain that it is unlikely that a breeding population would be able to sustain themselves in North American forests as great apes historically thrive only in the tropics of Africa and Asia. In addition, they would face competition with bears and other large predators and would be leaving behind feces and other identifiable evidence. Others argue that like bears, the creatures likely have an omnivorous diet and are opportunistic much like humans. Anecdotal accounts indicate that the creatures consume roots, berries, nuts, fruit, fungi, salmon and other fish, small mammals like rabbit and squirrel, birds, and hooved ungulates including deer and elk. There have also been alleged reports of Bigfoots consuming carrion and killing or stealing livestock. In 2016, Centralia College anthropology professor and "Bigfoot enthusiast" Mitchel Townsend presented forensic research at the 69th Annual Anthropology Research Conference that he and his team completed after studying three different prey bones recovered near Mount St. Helens. They claim that the bite marks found on the bones provide evidence of a large, unknown hominid having made them based on their characteristics.

Alleged interactions with humans have been reported. Many Indigenous American cultures traditionally fear and respect these creatures. An incident in 1924, often referred to as the "Battle of Ape Canyon", tells of miners being attacked by large, hairy "ape men" that hurdled rocks onto their cabin roof from a nearby cliff after one of the miners allegedly shot one with a rifle. A miner was supposedly knocked unconscious by a rock which crashed through the roof, and the creatures slammed into the cabin walls, causing the entire structure to shake. Canadian prospector Albert Ostman reported that he was abducted by a Bigfoot and held captive with its family for six days near Toba Inlet, British Columbia in 1924. He reported that they did not cause him harm, but were instead amused by his presence. In Fouke, Arkansas in 1971, a family reported that a large, hair-covered creature startled a woman after reaching through a window. This alleged incident caused panic in the area. According to the BFRO, there have been no credible modern reports of any humans being killed by a Bigfoot, but harassment and stalking-like behaviors toward people have been reported. The 2021 documentary film entitled Sasquatch describes marijuana farmers telling stories of Bigfoots harassing and killing people within the Emerald Triangle region in the 1970s through the 1990s; and specifically the alleged murder of three migrant workers in 1993.Investigative journalist David Holthouse attributes the stories to illegal drug operations using the local Bigfoot lore to scare away competition, specifically superstitious immigrants, and that the high rate of murder and missing persons in the area is attributed to human actions.

There have also been reports of dogs allegedly being killed by a Bigfoot. In the early 1990s, 9-1-1 audio recordings were made public in which a homeowner in Kitsap County, Washington called law enforcement for assistance with a large subject, described by him as being "all in black", having entered his backyard. He previously reported to law enforcement that his dog was killed recently when it was thrown over his fence. Anthropologist Jeffrey Meldrum notes that any large predatory animal is potentially dangerous to humans, specifically if provoked, but indicates that most anecdotal accounts of Bigfoot encounters result in the creatures hiding or fleeing from people.

Some amateur researchers have reported the creatures moving or taking possession of intentional "gifts" left by humans such as food and jewelry, and leaving items in their place such as rocks and twigs. Skeptics argue that many of these alleged human interactions are easily hoaxed, the result of misidentification, or are outright fabrications.

The History Channel television series MonsterQuest investigated a 2002 incident in which a remote wilderness fishing cabin on Snelgrove Lake in Ontario, accessible only by floatplane, was broken into and ransacked sometime during the winter months. Entire kitchen appliances had been ripped from the walls and shelves were torn down, but nothing appeared to have been stolen. Initial blame was placed on a bear as they are occasionally the culprits of home invasions and property damage in their search for food. Wildlife biologist Lynn Rogers of the North American Bear Center, after reviewing the insurance video of the cabin's damage, believes it was unlikely to have been caused by a bear due to hibernation patterns and because the refrigerator insulation, which would smell like an ant colony to a bear due to the presence of formic acid, was not ripped out and no claw or bite marks appeared present. Some have attributed the damage to have been caused by a Bigfoot as well as other strange incidents allegedly occurring near this cabin, while others maintain it was likely the result of human vandals or a bear. Other alleged incidents of vehicles being damaged with rocks has been attributed to Bigfoot behavior but skeptics argue it is likely the result of human actions such as pranks, or simply misidentification.

62 notes

·

View notes