Photo

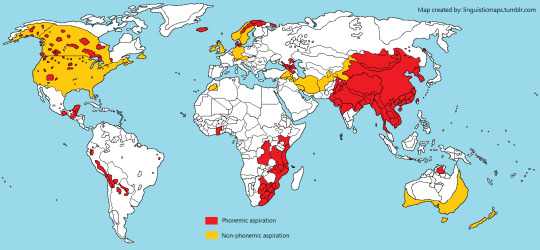

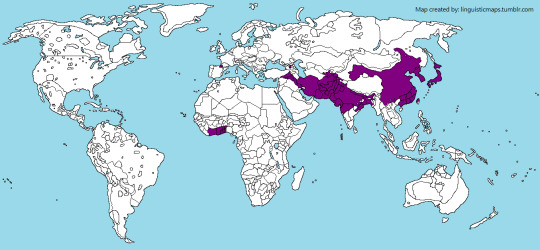

Aspirated plosives

Aspirations occurs in English in initial onsets like in ‘pat’ [pʰæt], ‘tack’ [’tʰæk] or ‘cat’ [’kʰæt]. It is not phonemic, since it doesn’t distinguish meanings, but it’s distinctive in Mandarin e.g. 皮 [pʰi] (skin) vs. 比 [pi] (proportion).

Non-phonemic aspiration occurs in: Tamazight, English, German, Swedish, Norwegian, Kurdish, Persian, Uyghur.

Phonemic aspiration: Sami languages, Icelandic, Faroese, Danish, Mongol, Kalmyk, Georgian, Armenian, North Caucasian languages, Sino-Tibetan languages, Hmong-Mien languages, Austroasiatic languages, Hindi-Urdu, Punjabi, Marathi, Gujarati, Odya, Bengali, Nepali, Tai-Kadai languages, Nivkh, many Bantu languages (Swahili, Xhosa, Zulu, Venda, Tswana, Sesotho, Macua, Chichewa, and many Amerindian languages (Na-Dene, Siouan, Algic, Tshimshianic, Shastan, Mayan, Uto-Aztecan, Mixtec, Oto-Manguean, Quechua, Ayamara, Pilagá, Toba, etc.)

#languages#linguistic maps#English#Icelandic#Mandarin#chinese#Thai#Vietnamese#Zulu#Swahili#Mongol#Hindi#Urdu#Punjabi#Georgian#Armenian#Danish#Maya#Navajo#Lakhota#Aymara#Quechua#Tibetan#Burmese#linguistics#phonology

317 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Glottal Stop

Languages that have a phonemic glottal stop /ʔ/ - about 40% of all human languages. This is a very widespread consonant except in Indo-European, Niger-Congo, Turkic, Uralic, Mongolic, Dravidian, Koreanic and Japonic languages.

It’s almost universally present in the indigenous languages of the Americas, in Afro-Asiatic languages, in Austroasiatic and Austronesian languages, in Papuan languages, North Caucasian langauges, and in some Khoe, Sino-Tibetan, Daic, Uralic, Iranian, Turkic and Chukotko-Kamchatkan languages. It’s also present in Estuary and Scouse English as in ‘watter’ as /woːʔɐ/.

#languages#linguistic maps#phonology#Arabic#Persian#Indonesian#Tagalog#Somali#Inuit#Guarani#Quechua#Maya#Nahuatl#Navajo#linguistics

582 notes

·

View notes

Photo

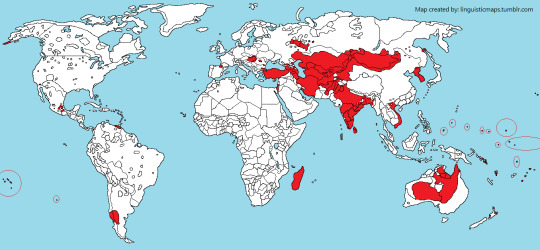

Tenseless languages

Language that do not possess the grammatical category of “tense”, although obviously, they can communicate about past or future situations, but they do it resorting to adverbs (earlier, yesterday, tomorrow), the context (pragmatics), but mostly aspect markers, that show how a situation relates to the timeline (perfective, continuous, etc.) or modal markers (obligation, need, orders, hipothesis, etc.)

Tenseless languages are mostly analytic/isolating, but some are not. They occur mainly in East and Southeast Asia (Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Austronesian, Kra-Dai, Hmong-Mien), Oceania, Dyirbal (in NE Australia), Malagasy, Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa, Ewe, Fon and many Mande languages of Western Africa, most creole languages, Guarani, Mayan languages, Hopi, some Uto-Aztecan languages, and Greenlandic and other Inuit dialects.

#languages#linguistics#language maps#linguistic maps#grammar#tense#Chinese#Mandarin#Maya#Thai#Indonesian#Malay#Hopi#Greenlandic#Inuktitut#Vietnamese#Burmese

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

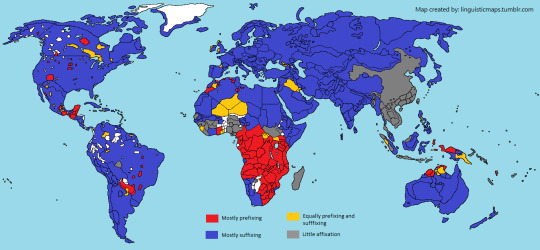

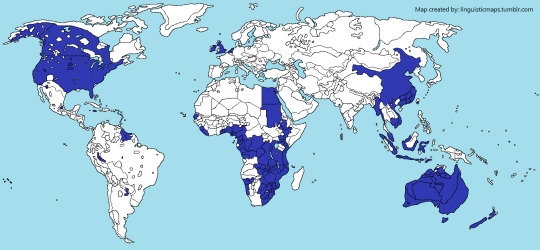

Prefixing and suffixing languages

Mostly prefixing - Most Berber languages, Bantu languages, Guarani, many Macro-Ge languages, Mayan languages, Oto-Manguean, Mixtec, Siouan, Navajo and many Na-Dene languages, some languages in northwest Papua and northwest Australia.

Mostly suffixing - Indo-European, most Afro-Asiatic, Turkic, Mongolic, Dravidian, Austronesian, Northeast Caucasian, Eskimo-Aleut, Uralic, Koreanic-Japonic, most Pama-Nyungan languages.

Equally prefixing and suffixing - Cree, Ojibwe, O’odham, Tarahumara, Pilagá, Carib, Central Atlas Tamazight, Tuareg, Iraqi Arabic, Zande, Krio languages, Ewe, Toba, many languages in east Papua-New-Guinea, Basque, Nortwest Caucasian, Celtic.

Little affixation - typical of isolating languages, in Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Hmong-Mien, Nilo-Saharan, Mande, languages of West Africa, many Austronesian languages.

Based off and simplified from: https://wals.info/feature/26A#2/22.6/153.1

301 notes

·

View notes

Photo

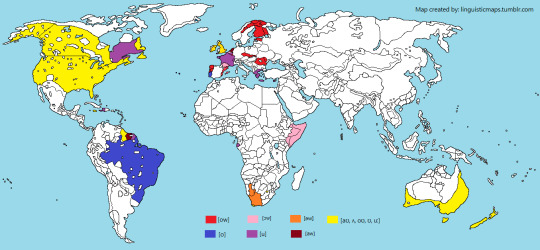

Pronounciation of the digraph <OU>

[ow] - Spanish (very rarely), Northern European Portuguese and formal register of Brazilian Portuguese, Galician, Catalan, Romanian, Czech, Slovak, Finnish, Karelian, Estonian, Sami languages.

[o] - Portuguese (European, and informal Brazilian)

[ɔw] - Somali, Occitan, Catalan and Flemish.

[əw] - Afrikaans, Europen Portuguese (Oporto city region).

[aw] - Dutch.

[u] - French (also for /w/), Breton, Cornish, and Greek, shown here for comparison althoug it is more precisely <ου> (o+ipsilon).

[aʊ, ʌ, oʊ/əʊ, ʊ, u:] - English as in <out>, <trouble>, <soul>, <could> and <group>, respectively.

Maybe I missed a few languages that use <ou>; if you know any more, point them out, please.

212 notes

·

View notes

Note

re: Relativization strategies. Bambara (and related Mandé languages) have a weird mix of the listed strategies that may be translated as [man REL ate bread] [that one disappeared]: "the man who ate bread disappeared". "that one" being a regular relative pronoun, as I understand it. The relative marker is applied to whichever noun in the relative is being referred to in the principal clause, not the verb. (African Languages: An Introduction, pp. 256-257, you can see the pages on Google books.)

thank you!

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

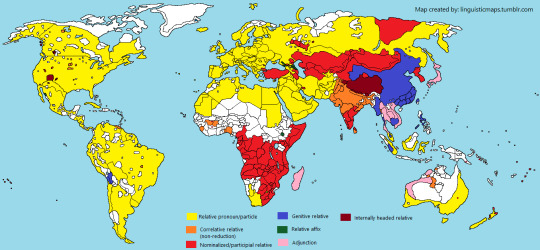

Relativization strategies

How do languages form relative clauses like “the man that ate bread went home”.

Relative pronoun/particle/complementizer - “the man [that/who ate bread] went home”. Typical of Indo-European, Uralic and Semitic languages.

Correlative relative (non-reduction) - “the man [who ate bread], [that man] went home or "the man [he ate bread] went home” - this strategy involves an anaphor, repeating the antecedent with a noun/pronoun. Pronoun retention is also lumped in here. This strategy occurs in Indo-Aryan languages (Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, etc.), in Mande languages (e.g Bambara in Mali), Yoruba, Lakhota, Warao, Xerente, Walpiri, etc.

Nominalized/participial relative - “the [bread eating] man went home" or "the [bread eaten] man went home" - I lumped this two together because the behaviour is very similar - used in Turkic, Mongolic, Koreanic, Dravidian, and Bantu languages.

Genitive relative - “[ate bread]'s man went home" - used in Sino-Tibetan, Khmer, Tagalog, Minangkabau, and Aymara.

Relative affix - “the man [ate-REL bread] went home” - used in Seri, Northwest and Northeast Caucasian languages and Maale (Omotic).

Adjunction - “the man [ate bread] went home”, with no overt marker just justapositions modifying the main clause. Used in Japanese, Thai, Shan, Lao, Malagasy.

Internally headed relative - "[the man ate the bread] went home", the nucleous is in the relative clause itself. Used in Navajo, Apache, Haida.

If you know about the languages left in blank, please let me know!

#linguistics#syntax#relative clauses#languages#linguistic maps#language maps#Indo-European#Turkish#Hindi#Navajo#Mandarin#Japanese#grammar

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nonconcatenative morphology

Nonconcatenative morphology, also called discontinuous morphology and introflection, is a form of word formation in which the root is modified and which does not involve stringing morphemes together sequentially.

It may involve apophony (ablaut), transfixation (vowel templates inserted into consonantal roots), reduplication, tone/stress changes, or truncation.

It is very developed in Semitic, Berber, and Chadic branches of Afro-Asiatic. It also occurs extensively among other language families: Nilo-Saharan, Northeast Caucasian, Na-Dene, Salishan and the isolate Seri (in Mexico).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nonconcatenative_morphology

#languages#linguistics#language maps#linguistic maps#morphology#grammar#Arabic#Berber#Maltese#Navajo#Athabaskan#Salishan#Chechen#Hausa

386 notes

·

View notes

Photo

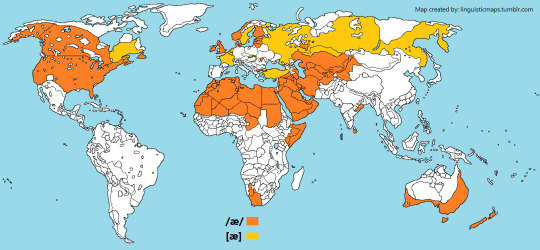

(near) Open/low front unrounded vowel

This is the vowel used in English “sad”. It exists as an allophone of other vowels in Turkish, Russian, Dutch, Slovak, Swedish and French (as a nasal vowel).

Phonemically, it exists in English, all Arabic languages/dialects, all Berber languages, Somali, Afrikaans, Norwegian, Finnish, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Danish, Kurdish, Azeri, Persian, Qazaq, Uzbek, Turkmen, Uyghur, Bashkir, Orya, Sinhalese, and in some dialects of Portuguese, Andalusian Spanish, Greek, Romanian.

216 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Light verb constructions

A light verb is a verb deprived of its basic meaning. Many languages employ them in extensive constructions of verb+noun, instead of forming new verbs.

In English, the verb “make” can be a light verb, as in “make the bed”. It doesn’t mean that you are going to literally “build a bed”. But in many languages these constructions are the norm for new verbs that enter the language and are extremely common.

In many languages, like Basque, Persian, Hindi, or Japanese, instead of “to clean” one can have “do cleaning”, or instead of “to speak”, “to make talk”, or instead of “to hug”, “to give hug”.

A light verb is in the midway between a full lexical verb and an auxialiry verb. In English a few verbs can function as light verbs (do, make, give, take, have) but these constructions are not the norm.

If you know more languages that use these constructions frequently (I’m not sure about Turkic languages), please inform me.

#languages#linguistics#syntax#grammar#linguistic maps#Indo-European languages#language geography#Basque#japanese#persian#Mandarin#Hindi#Akan

473 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Languages where 3rd person singular pronouns are the same or derived from demonstrative determiners

For example, “o” in Turkish is both “he/she/it” and “that”.

Source: https://wals.info/feature/43A#3/32.99/28.92

395 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Double object construction

Some languages, instead of a dative construction (He gave the meat to the dog), exhibit a double object construction, like English: He gave the dog the meat. In this case there is no marker to indicate the indirect object, just the justaposition of both the direct and indirect objects, without any case marking. Both objects are treated as the same. This contrasts with a dative or indirect object construction, and with a secondary-object marking.

English, of course, behaves in a mixed way, allowing for either dative or double object constructions. In the map, all languages with either mixed or only double object constructions are marked.

385 notes

·

View notes

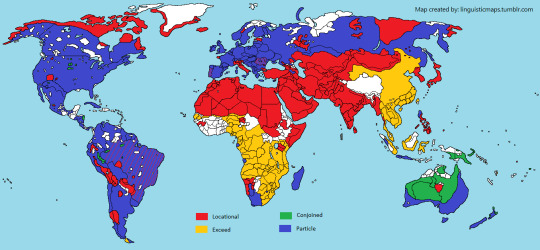

Photo

Comparative constructions

Ex: "My father is older than my mother".

Types:

1. Locative comparatives: "From my mother, my father is old" - a movement pre/postposition or case like "from, to, at, on, for" (includes genitive constructions).

2. Exceed comparatives: "My father old exceed my mother" - a verb meaning "to exceed" or "to surpass".

3. Conjoined comparative: "My father old, my mother young" - two clauses, with antonyms or a negation of the opposite, or just justaposition of the terms.

4. Particle comparative: "My father is older than my mother" - particle "than" with or without a marker on the adjective.

Some languages use a mixed strategy, like Russian, Romanian, Portuguese or Italian. Only the most used strategy is shown in some cases.

Source: https://wals.info/chapter/121

547 notes

·

View notes

Note

(...) Clearly, all three languages possess an 'exist' verb; in the third person singular (il) existe, existís/existeish and existeix in French, Occitan/Gascon and Catalan respectively. At the same time, apart from this Latin loan, all three use essentially the same possessive-locative construction, In the same order, il y a (y avoir), i a (i aver), hi ha (haver-hi). Nothing else comes to mind as far as existential verbs for any of the three languages. Did you have something else in mind?

I was mistaken about Occitan, but the differences are that in French “avoir” has a possession meaning (to have), so it’s a “possessive existential” (the same goes for Occitan...) but in Catalan, ‘haver’ no longer has the possession meaning, now it’s only an auxiliary verb and used to form existential phrases so it’s an “existential verb”. In all three cases, a locative particle is used (y, i, hi), and in the map you can see the superimposed purple lines for a “locative existential”. I hope I’ve answered your question.

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just wanted to say I think you're doing some great work that has sparked many trips down the wiki-rabbit hole for me! I'm sorry you have to deal with nationalist jerks in anon 💙 Thank you for helping me keep up with my interest in linguistics

Thanks for the support!

24 notes

·

View notes

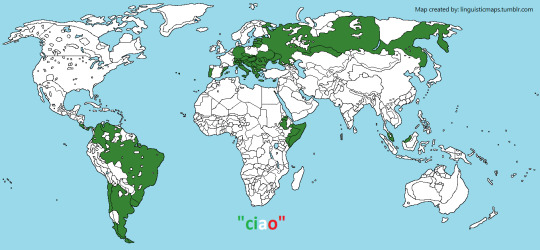

Photo

Languages that use “ciao” or a similar version descended from Italian as a greeting or an informal goobye

Present in: Portuguese (tchau), Spanish from Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Paraguay, Colombia, Venezuela, Panama, Costa Rica, Catalan, Sicilian, Maltese, Venetian, Lombard, Romansh, German (tschau), Swiss German, every Slavic language except Polish and Belarussian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Estonian (tsau), Greek, Albanian (qao), Romanian (ceau), Hungarian (csaó), Somali, Amharic, Tigrinya, Malaysian. The Vietnamese “chào” is not related to Italian, so it’s unmarked there.

Edit: the map only includes those languages that use ‘ciao’ as the most common informal way of greeting/goodbye, not as part of slang, argots or people who use it just to sound cool. For example, in Portuguese, Maltese or Latvian it has surpassed the older forms of saying goodbye in informal situations for all social classes.

#languages#linguistics#sociolinguistics#Italian#Italy#Brazil#russian#argentina#somali#german#serbian#croatian#portuguese#colombia#linguistic maps#language maps#lexicon#borrowing

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

Ideophones- Turkish- tiril tiril / güm güm- the gun or ball songs / tak tak- the door songs/ car car - talking so much

Thanks, I took note.

6 notes

·

View notes