#which was just a continuation of the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution but I digress 🚶♀️➡️

Text

The American Revolution, in my opinion, is one of the most misinterpreted events both in real life and in the hetalia fandom. It wasn't a revolution based on the rejection of all things English but an assertion of all things English, from Common Law to the (English!!!) Bill of Rights to the Constitution being inspired by the Magna Carta. Hell, even apple pie, the most American thing about this country, is English. And this was a very conscious choice, not something that happened miraculously, so when people say Alfred’s entire ambition in life is to be the complete opposite of Arthur, it doesn't quite make sense to me because that's simply not true (and historically illiterate and disingenuous)!!! The American Revolution in part happened because the colonists wanted to be treated like Englishmen, they believed they were Englishmen who desverved English rights despite half of them not being born in England, and when they understood they weren't going to be treated as such they departed on the hopes of creating a system where they could live as Englishmen in truth!!! Alfred purposefully mirrored himself after Arthur. Did he believe he exemplified/embodied English ideals better than Arthur ever could? Of course he did! But this only further proves my point.

#heavy usage of the word English but i really need to drive this point home lmao#hetalia#hetalia meta#aph america#aph england#alfred f jones#arthur kirkland#american revolution#which was just a continuation of the English Civil War and Glorious Revolution but I digress 🚶♀️➡️

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

... Remember the Russian Revolution au? Which ended with Fedyor's sister very sick and Fedyor searching for Ivan in hopes of getting help for her from him? Fedyor finding Ivan and offering to do "anything" in exchange for his sister's medical treatment? Ivan secretly wanting Fedyor, but refusing to take what he wants like that? Soooo... I would also like the big the big 3 of your coming projects to happen, but... y'know... just.... wanted to bring this au up again... ;)

Behold, the oft-requested follow-up to the first two Russian Revolution au ficlets. Ahem.

Fedyor does not sleep that night. He does not even think about sleeping. He only leaves the army headquarters long enough to think hard about what he is proposing to do, wonder if it is worth it, and decide that it is. Katya needs the medicine, he has no other recourse, and he is categorically unwilling to return home to his family as a failure, when they have placed all their trust and hope in him. Ivan has hinted that he might be able to obtain it, and so that, no matter what it takes, is what Fedyor will have to get him to do. And for that…

He knows that he is not unattractive. He has dark eyes, dark hair, a dimpled smile, a personable and friendly manner that, in happier times, attracted the attention of many an eligible young lady who wished to ice skate or promenade around the park or take a carriage ride, as courting Russian couples are wont to do. However, while Fedyor was perfectly happy to chat with ladies, or escort them to a ball, or fulfill his essential chivalric duty, he was not otherwise interested in wooing them. It was partly for that reason that he signed up to the military, where an enterprising young man can have other opportunities in the darkness of the barracks. So long as his family was kept conveniently unaware.

For all that the Bolsheviks have overthrown the government without a clear plan as to what to do next, and accordingly plunged them all into this miserable civil war, Fedyor does secretly sympathize with certain of their beliefs on the remaking of family life. They say that marriage is outdated and bourgeoisie, that monogamy is unnatural, that women should not be subject to patriarchal systems, and that homosexuality is an equally valid state of nature. Such a possibility of sexual classification and divergence is much discussed in Europe these days, and there is even a small but growing scholarly literature, written by eminent scientists. Sexual Inversion by Havelock Ellis, published in 1896, argues that the man-loving man is indeed even a possibly improved form of human, associated with superior intellectual and artistic achievement, and that nothing about his attachment is wrong or abnormal. Two years before that, Edward Carpenter wrote Homogenic Love, and in 1900, the German Elisar von Kupffer published an anthology of homosexual poetry, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur. Such texts are relatively easy for an educated, French- and English- speaking young Russian intellectual, such as Fedyor Mikhailovich Kaminsky, to lay his hands on. He is not sure what can come of it, but at least he knows that he is not alone.

The question remains as to Ivan Ivanovich Sakharov’s proclivities. Unless Fedyor is very much mistaken, Ivan was at least considering the possibility of accepting his offer, and turned it down for honorable, moral reasons, feeling it unjust to sexually extort a young gentleman in exchange for his sister’s care, rather than physical horror at the idea of such a coupling. If he’s a Bolshevik, he’s probably acceptably tolerant of their philosophy on an abstract level, but it’s less clear as to whether that extends to its personal practice. If Fedyor turns up in his bunkhouse – which, come to think of it, is probably shared, curse these Bolsheviks and their dratted communality, highly inconvenient for a midnight seduction attempt – scantily clad and willing, will Ivan’s objections hold out then? Or… or what?

Fedyor doesn’t know, but the uncertainty adds to the frisson of shameful excitement, rather than detracting from it. He searches through the streets of Chelyabinsk for some bread (it does not seem in much greater supply than in Nizhny Novgorod) and waits for the sun to go down. In March, the days, though getting steadily longer, are still short and chilly, and it’s bitingly cold when it gets dark. Then he pulls up his muffler, tells himself not to be unduly precious about it, and heads for the makeshift army quarters on Kirovka Street.

The buildings in downtown are beautiful, built in the Russian Revival style of neo-Byzantinian splendor, though the onion-domed Orthodox churches have all been converted into stables and armories, and anything that whiffs of an ideology contrary to the Red one has been economically discarded. Fedyor reaches the door, knocks, and when a disgruntled sergeant comes to answer it, expecting him to be a soldier out too late and in line for a ticking-off, Fedyor raises his hands apologetically. “I’ve come to join up,” he says. “The great socialist cause of the world’s workers is the only true one for a patriotic Russian man, and I vow it my full allegiance, if you will have me. I was speaking to my friend earlier, Ivan Ivanovich, and he suggested it. Is he still here?”

The sergeant eyes him squiggle-eyed, but they cannot afford to look gift horses too closely in the mouth, or turn aside willing recruits. It takes a while, but he shouts for someone who shouts for someone else, and this finally produces the startled personage of Ivan Sakharov, who clearly thought it was for the last time when they parted several hours ago. Upon sight of Fedyor, he stops short, looking alarmed, angry, and wary all at once. “What are you – ?”

“Can we talk?” Fedyor is resolved to do this, he truly is, but he feels it best to get it over with before that wavers in any degree. Whether he wants it too little does not seem like the problem; on the contrary, he fears that he wants it too much, and if he stops to reflect on it or delude himself with any nonsensical notions of it being more than once, that can only hurt the cause. “Somewhere… private?”

Ivan hesitates, as if asking to commune out of sight of the others is tantamount to heresy (though it’s not as if these damn hypocrites didn’t plot in secret, away from their own countrymen, for months and months, Fedyor thinks angrily). Then he jerks his head. “Fine. Five minutes. This way.”

He leads Fedyor up a few narrow, creaking staircases, past closed doors that echo with snorting and snoring and coughing, the cacophony of his comrades, none of whom seem to be enjoying their glorious victory quite as much as they thought. Ivan, however, appears to be sufficiently high-ranking in the Red Guards that the room they finally arrive at, though not much larger than a closet, is at least private. It reminds Fedyor forcibly of Ivan’s room back in St. Petersburg, the one they slept in together, that first night after the Winter Palace. It sounds more intimate in his recollections than it actually was. Nothing happened, of course. But Ivan was kind to offer it, kind when he did not need to be, when a young tsarist soldier alone in the ferment of riot and revolution, such as Fedyor was, would not be likely to see the new red dawn. It is that which Fedyor keeps in mind as he shuts the door with assumed casualness, then turns around, meets Ivan’s eye in a significant fashion, and shrugs off his coat, cap, and muffler. Then, unmistakably, starts to unbutton his shirt.

He has almost gotten to the bottom by the time Ivan, who is staring at him as if he’s lost his marbles (it is unclear if this is an encouraging fashion or not) finally recovers his sense. He strides forward and covers Fedyor’s hands with his own large, callused rifleman’s fingers, sending a shock of attraction burning through Fedyor from head to toe, along with the death of any more illusion that he could continue to be casual about this. “What are you doing?”

“Isn’t it obvious?” Fedyor’s throat is as dry as a bone, but he forces himself to speak. “I said that I would do anything for my sister’s care, if you would help.”

He lingers suggestively on the word anything, just as he did before, in case there was any doubt (as if the undressing wasn’t enough) what he means here. Ivan looks like a cornered bear, but as his eyes catch Fedyor’s and flick across the lean, muscled torso thus revealed beneath the shirt, he swallows hard and has to glance away. The attraction trembles silently in the air between them, tense as a piano string, tuned to snapping. In the old days, that is, when people played pianos, and did not burn them for firewood, as Fedyor’s parents were preparing to do with theirs when he left home. It chokes raw and painful in his throat. He is attracted to Ivan – desperately attracted, in fact – and yet he still hates what the Bolsheviks have done, even if the Romanovs and the Provisional Government were no better. The deposed Tsar Nicholas II is under house arrest with his wife and five children, the four tsarevnas and the tsarevich, in Yekaterinburg. Little sick Alexei Romanov, whose hemophilia opened the door for Grigori Rasputin to control the queen, the royal household, the government of Russia, and so bring about the end of their house. He was like something from a fairytale monster, that Grisha. The rumors of his death, not quite two years ago in December 1916, is that it almost did not happen, he was so hard to kill. A demon. A beast.

“You cannot do this,” Ivan says, his voice too rough, his eyes still struggling to remain decorously averted. “It is not – it is not right.”

“Not right?” Fedyor flares. “So a little spot of armed treason and overthrowing the man who, however deficient he might be, was the heir of one of the oldest and greatest empires in the world? That part was entirely aboveboard, but this, when you want this – don’t lie to me, I’m well aware you do – to help my sister? That would be a sin?!”

Ivan backs up a step, glancing around shiftily. These walls are thin, and he clearly does not want his beloved brothers-in-arms to hear this. “Fedyor Mikhailovich – ”

“Have me.” Fedyor is done playing games. “I’m here, I’m yours for the taking. You can do whatever you want to me, as long as you give me the medicine at the end.”

For a long, spellbound moment, he thinks Ivan is on the brink of agreeing. Then once again, he shakes his head. “No,” he says. “I could not in good conscience consent to this. But I will fetch you the medicine. You do not have to give me anything in return.”

Fedyor gawks at him, shocked – and, it must be confessed, more than a little disappointed. “I thought it was fair trade,” he says. “Tit for tat.”

“It is…” Ivan shakes his head, eyes once more straying to Fedyor’s bare chest. “Button your shirt up,” he says, half-laughing, not angry, breathless and soft. “It is very distracting.”

“Good.” Fedyor takes another step. “I think you deserve it, you obnoxious bastard.”

“Be that as it may.” At least Ivan has the good sense not to dispute it. “I cannot do this,” he repeats, more gently. “You are a fine young man, Fedyor Mikhailovich. Perhaps in another life… but it would not be honorable to trade your virtue for this.”

“My virtue?” Fedyor has to laugh. “What makes you think I have that?”

Once again, Ivan wavers. But to give him (loathing) credit, he will not be swayed. “Button it,” he repeats. “I will arrange to have the money and medicine sent by your lodging by tomorrow, if you give me an address in the city.”

“I don’t have one.” Fedyor folds his arms. “Only here.”

Ivan looks even more startled. His lips part, he takes a step forward, and for a brief, wild, exquisite yearning of an instant, Fedyor thinks he is actually going to kiss him. They’re almost close enough – not quite, but almost – for it to happen. Then Ivan says, “Your family must be very proud of you.”

“I…” It catches in his throat. “I don’t know. I hope.”

“I would,” Ivan says. “I would be.”

And that, somehow, is all that seems to matter. Even as Fedyor spends a night in Ivan’s narrow camp cot of a bed, Ivan insisting on taking the hard floor out of an excess of gallantry, an echo of their first night in St. Petersburg. Ivan does as ordered, gives Fedyor some rubles and some medicine and a train ticket back home to Nizhny Novgorod. He personally escorts Fedyor to the train station to make sure he does not come to grief, then stands on the platform, staring after him like Vronsky watching Anna leave one more time. The train begins to huff and puff, spitting soot and embers, and Fedyor keeps his nose pressed to the glass, leaving a smudge, until long after, as it seems he is never destined to do anything but, Ivan Ivanovich Sakharov has vanished into the mist.

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

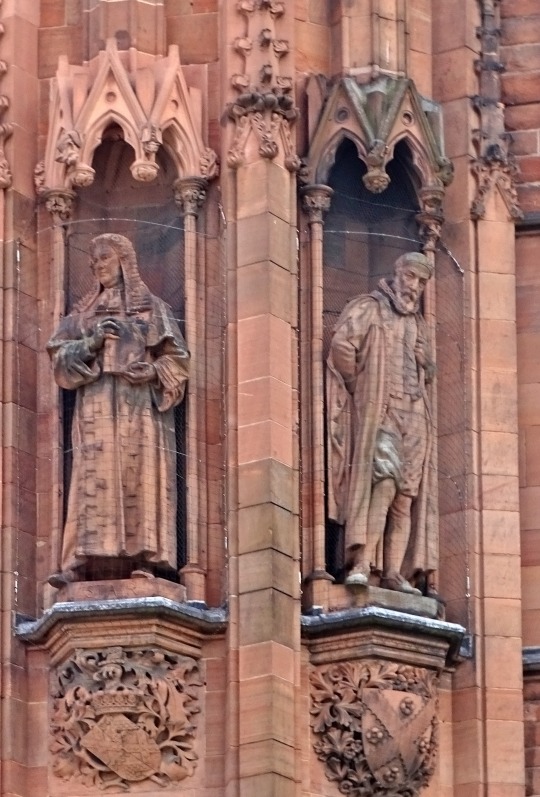

Scottish National Portrait Gallery Statues.

Continuing on with my pics from last week.

King Robert I. Known as Robert the Bruce, this is arguably our best known monarch, certainly amongst Scots. Long before Mel Gibson rode into town and used the term Braveheart, King Robert was known by this nickname.

Robert the Bruce was defeated in his first two battles against the English, and became a fugitive, hunted by both Comyn’s friends and the English, hence the title of the film, Outlaw King.

Legend has it whilst hiding, despondent, in a room or a cave he is said to have watched a spider swing from one rafter to another, time after time, in an attempt to anchor it’s web. It failed six times, but at the seventh attempt, succeeded. Bruce took this to be an omen and resolved to struggle on. Differing versions of the spider story exist, but the saying “If at first you don’t succeed” is said to have sprung from the medieval tale.

The Bruce sent the English homewards to think again in the year 1314 at Bannockburn, six years later he was instrumental in the drawing up of The Declaration of Arbroath but it wasn’t until 1328 that a formal peace treaty was drawn up between the Auld Enemy and Scotland. Robert the Bruce died just over a year later in June 1329 his place in our proud history firmly in place.

King James I. James was sent to France by his father for his own safety after his uncle The Duke of Albany was complicit in the death of his brother, the heir to the throne, David, Duke of Rothesay. On his way to France his ship was seized by pirates who “sold” him to the English.

James was held as a prisoner in England for 18 years, although he was afforded the education and trappings of his position. The English King Henry V took James to France during the Hundred Years' War where he asked Scots defending the French town of Melun during a siege to lay down their arms, which they dismissed out of hand. When the town fell the French prisoners were in the main spared as Prisoners of war, the contingent of Scots were hanged for treason against their king.

James, on his release purged the Scots court of many of the Nobility he took a dislike to and was eventually assassinated on 21st February 1437 at The Blackfriars Monastery which once stood in Perth.

Sir James Dalrymple 1st Viscount Stair. Born into a family descended from several generations of landed gentry who were involved in the Reformation, James fought during the War of the Covenant against the Stewart Kings Charles I and II who were interfering in their church affairs, it was all to do with the divine rights of Kings that the Stewarts believed so dearly in. He was educated mainly at The University of Glasgow and became one of our leading legal minds of the era. He wrote “The Institutions of the Law of Scotland” which provided the foundation for Scots law.

Dalrymple became Lord President of the Session in 1671 but resigned in 1681, the year in which the Institutions was published.

Stair's resignation was due to his reluctance to take the Test, an oath that asserted the supremacy of the King over the Church. He went into exile in the Netherlands until 1688, when he returned in the entourage of William of Orange after the Glorious Revolution and all his former positions were restored.

Walter Scott must have been a fan of the family writing that his descendants. "The family of Dalrymple produced within two centuries as many men of talent, civil and military, of literary, political and professional eminence, as any house in Scotland."

John Napier. Finally in this post, Napier was a Scottish scholar who is best known for his invention of logarithms, the bane of my life at High School, I detest logarithms, algebra and all that goes with it. That’s not arithmetic by the way, I can do mental arithmetic.

Anyway the Napier's were an important family in 16th Century Scotland, they hailed from Merchiston Castle, the castle dates from the mid 15th century and remarkably survives to this day surrounded by Edinburgh Napier University.

John Napier dabbled in alchemy, the occult and witchcraft, bear in mind this was in the days when you just needed to fall out with someone to be burnt as a witch! Well unless you had a title and money!

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sonic opinions - 4

Initially, the purpose of my fanfics was almost only to think of a possible continuation of the events of Sonic SatAM, adapting things from the Archie-Sonic comics (and taking some licenses in the process), and trying to better write Antoine's transition from his self in the cartoon to his self in the comics, give more importance to Tails and better portray his parents, Amadeus and Rosemary. But then I realized how abysmal the differences between the two versions of Antoine were, while it was also harder for me to think of a way to write Rosemary coherently.

In Antoine's case, lately, I came up with an alternative to make him develop and stop being what he was in the TV series:

Immediately after the original Robotnik has been defeated, Antoine leaves his team behind. He actually doesn't know how to fight, but he still has good marksmanship, so he becomes a hitman. However, he's eventually convinced to leave behind that life without honour, begins to train in real fighting skills and becomes a genuine Freedom Fighter once and for all. In any case, he develops an opinion of "the end justifies the means" and continues thinking it for the rest of the story, being critical of his former team; this, along with his lasting grudge against Sonic and Sally, leads him to fight against the Monarchy in the events of "Civil War".

As for Rosemary... I don't like to say it this way, but she was a total b**** in the comics. I came up with a way to show her in a better light, but in no way could it have worked with the comics' Rosemary as she was. I'll talk about it when I write my list of ideas for future fanfics.

--------------------------------------------------

I also addressed Politics in that fictional universe, trying to avoid the way this was done in the comics: there, Ian Flynn created the Council of Acorn and portrayed it as a bunch of stereotyped useless politicians obsessed with controlling the heroes and barely concerned with their country's security, and I think Flynn didn't do it to actually enrich the comics' universe or to add depth to the story or to communicate certain political ideas, but only to give readers someone to blame.

In the stories I wrote so far, I didn't go deep into what happened with my fictional universe's Council of Acorn after its creation; however, I did address its origin, and in doing so, I didn't make the Bems involved. Look... In the comics, Tails's parents were inspired by the Bems to try to establish a Democracy in Acorn, and this entails some inconvenience:

The Bems are terrible people. They roboticized Sonic and Tails to make them fight Robotnik and Snively, in order to verify the robots were better than flesh-and-blood beings (if things had happened differently, perhaps Mobius's Robians wouldn't have been de-roboticized); their society is entirely made of clones and almost lacks variety, not only in terms of the physical but also in terms of people's ideas; their judicial system is quite f***ed up (at least according to our standards), and... *sigh* they're just the worst. These traits of the Bems had been developed when Karl Bollers wrote the comics, and Flynn should have considered that they’re technically canon before having Tails's parents claim to have been inspired by those aliens.

Even if we cling to Moral Relativism with all our strength, claiming the Bems are just "different" and have different behaviour, mindset, psychology and culture, this keeps making things complicated: applying something in one society, solely because it succeeded in another, ain't exactly something smart to do.

And the craziest of all is that it could have been avoided very easily: Flynn could simply have said there were previous failed attempts to establish a Democracy in other countries of Mobius and Amadeus & Rosemary had always wanted a change in the government system, had learned about those historical events and knew (or believed they knew, at least) how to do it right this time. Moreover, Flynn could have said the decade spent by Tails's parents with the Bems gave them a clue about what they should not do when finally returning to their homeworld.

I tried, in my work, to use this idea of Amadeus & Rosemary wanting to establish a Democracy in an attempt to succeed in what others in other parts of Mobius had failed throughout History. It was based upon what happened in the French Revolution (more precisely, the Jacobin period), the years immediately after the Russian Revolution, and mainly the First English Revolution: in 1648, the Monarchy was overthrown in England; the change was violent and chaotic, the government that took the place of the King ended up being also a despotic tyranny, and the final result was just the return of a King to power in 1660 (although, anyway, the Glorious Revolution established in 1688 the British parliamentary system as we know it); Thomas Hobbes, while watching those events unfold, wrote his book Leviathan, where he justified the need for an Absolute Monarchy by arguing humans were violent, selfish, chaotic and brutal by nature, so they had signed a symbolic pact where they ceded all their rights and their power to a single person in charge of ruling with an iron fist, in order to prevent humanity from destroying itself. In my fanfics' universe, it was mentioned those attempts at democratization in Mobius led to civil wars, ended with those same peoples clinging to ideas similar to those of Hobbes, quickly restoring the Monarchy and promising themselves not to try and establish a Democracy ever again.

I also mentioned the recurring conflicts between the Acorn Kings and the Southern Barons in the comics, as well as the connection between the Kings and the infamous Source of All, among other things. I also had Amadeus do what he should have done in the comics when he explained why he wanted there to be Democracy: to present historical events, such as those conflicts, the Kings' cult of the Source of All and the technological and cultural backwardness to which the people were subjected by them, as concrete examples of how the Monarchy had never worked well.

--------------------------------------------------

There are several Sonic fans, including @toaarcan and @robotnik-mun, who argue Politics shouldn't have been addressed at all in Sonic stories. Also, the vast majority of Sonic fans claim each and every one of the attempts to make this series more serious were some of the worst things that could have happened, even the addition of more characters was nothing but a cancer, and everything should have remained "simple" or the Sonic franchise shouldn't have gone beyond what it was at the time of the classic Genesis games. I praise the stories written by @toaarcan, and I agree with many of the opinions of both him and @robotnik-mun, but with all due respect, I totally disagree on this particular point.

I've always believed that, if it's done right, any topic should be able to be addressed in any kind of fiction, and Politics is no exception; more exactly, I think an author has two options when writing a work aimed at children and young people: to write something super light and soft where no serious topic is addressed, or to "go all-in" and address all serious topics, leaving nothing out; this includes not only Politics, but also tragedies, the complexities of love, toxic interpersonal relationships (whether abusive or otherwise), bullying, mental illness, trauma (for example, that caused by war), societal issues, and so on. That's one of the many whys of my love for RWBY: there's nothing that web-series doesn't talk about. As for the proper and respectful LGBTQ+ representation, rather than a serious topic reserved for serious fictional works, it's a requirement every fictional work should meet, whether serious or not, especially in the middle of the 21st century (this is something I think my work didn't meet satisfactorily).

With Sonic SatAM and the comics, it looked like the second option could have worked in the Sonic franchise too, and the TV series did it right to some extent. Unfortunately, Archie-Sonic's writers almost never did things right in regards to relationships between characters: Ken Penders's work, in particular, is an example of how relationships should never be, and Flynn's attempt to talk about Politics was a complete disaster, not much better than Penders's heinous handling of political stuff, more similar to a very low-quality North-American political satire, even when the conflict portrayed wasn't of the "Right versus Left" kind but of the "Monarchy versus Republic" kind, which should have been much easier to do without ruining everything. The only ones who didn't fall into those same mistakes were Gallagher and Angelo DeCesare, the comics' first writers, but only because they chose the first option: to write stories that weren't serious at all... with the notable exception of "Growing Pains", the B-story of issues #28 and #29, a typical Shakespearean tragedy where they presented us Auto-Fiona, a robot replica of who would later be one of the most controversial characters in the comics.

This, coupled with the resounding failure of Sonic 2006, is the only reason why now almost everyone in the Sonic fandom prefers stories without anything serious and/or a return to the Classic Sonic era, with very underdeveloped characters who are turned into mere plot devices and are only a shadow of their former self or of what they could have been.

#sonic fanfiction by mashounen#sonic opinions by mashounen#sonic#archie sonic#sonic comics#sonic the hedgehog#sonic 2006#ken penders#ian flynn#penders is an asshole#ian flynn is not much better#antoine d'coolette#rosemary prower#miles tails prower#amadeus prower#rwby#sonic satam

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Person from outside the UK who'd like some help understanding what's going on in British politics. If Parliament is extremely divided and there's a no-confidence vote on PM May and nobody likes how the Brexit pullout is going... does the Queen have any authority to step in at this point and convince Parliament to work some sort of compromise out? It was my understanding that the Queen/King was supposed to act as a unifying force in situations like this...

In theory? Yes. In practice? No, not really. It’s a lot more complicated than that.

Forgive me if I’m explaining things you already know but basically, what’s happened is that yesterday Theresa May finally brought the deal she’s negotiated with the EU over the last two years - which comprises both the conditions and the deal for the UK leaving the EU, and the agreements for trade and our relationship going forward - to Parliament to vote on, and they voted to reject it by 432 votes to 202, the largest ever defeat for a sitting government.

According to a previous vote, Theresa May and the government now have to bring a Plan B - i.e. an alternative deal - to Parliament to vote on. However, because the deal was defeated, Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, has chosen to table a motion of no confidence in the government as a whole.

This is different from a vote of no confidence just in Theresa May. If it was just in May herself then regardless of the outcome the current government would remain in power, but May would be removed as leader of the Conversatives and it would be up to the Tories to hold an internal election to choose a new leader who would succeed to the role of PM and the government would continue.

Corbyn is asking the House of Commons to declare whether they have confidence in the entire government. If his motion passes - i.e. Parliament declares they have no confidence in the government - then the government itself is suspended and a 14 day countdown starts. During that time, the Tories have to try to form a new government than can win a vote of no confidence, otherwise at the end of the 14 days a general election will have to be held. (I expect this is unlikely to happen, and the Tory MPs willing to vote against the Brexit Deal and even to try and oust Theresa May aren’t going to want to risk the Conservative Party losing power entirely and Corbyn having a chance at an election, and I doubt the DUP will want to lose their leverage in the House of Commons.)

Now as far as the Queen goes, her powers are largely ceremonial as she is a constitutional monarch - however, she does have some prerogative powers that she could theoretically exercise which include:

appointing and removing ministers

granting or refusing assent to Bills passed through Parliament

So in theory the Queen could step in to dismiss government ministers and appoint others in their place, and she could in theory refuse to give assent to any kind of Brexit deal that gets through Parliament.

Technically, the negotiations being entered into with the EU are also taken under Royal Prerogative with the Prime Minister and Cabinet Members acting as ambassadors of the Crown, so in theory the Queen could also choose to reclaim that Prerogative and exercise it for herself.

However the reason I say all of this is in theory is because in practice, it just won’t happen.

To give some context, the last monarch to refuse to give assent to an Act of Parliament was Queen Anne in 1708. Other times that the monarch has gone up against Parliament has resulted in:

the English Civil War in the 1640s, which ended with Charles I’s execution

the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when James II was deposed and William III and Mary II installed in his place

Edward VIII abdicating the throne in 1936

So in a general sense the Queen exercising any of her powers at this point does not look good in terms of historical precedent. This would be a far cry from Prince Charles’ Black Spider Memos which just give voice to his concerns, but would be seen as her overruling the sovereignty of Parliament, who have been democratically elected by the people, and would be hugely unpopular.

In your hypothetical scenario, there’s also the question of what would she be trying to unifying the country around? What would her compromise be? Would she insist on Brexit being put through or would she be using her powers to try and undo it?

As a Constitutional Monarch, the Queen’s role can be consulted by Parliament, she can encourage them and she can warn them - but she must be politically neutral in doing so. The Queen has stuck very scrupulously to that throughout her reign, which is one of the reasons she has been so successful and the royal family has survived, but there is no way to be apolitical when taking any kind of stance on Brexit.

At best, the Queen might speak privately with the Prime Minister and other members of Parliament but stepping in publicly in any way is likely to make tensions over Brexit worse and cause possible long term damage to the monarchy itself.

The government and Parliament have created this mess, and it’s going to be up to them to find a way out of it. What that’s going to look like, though, is anyone’s guess at this point.

#brexit#uk politics#british politics#I mean it would be highly ironic if all this yelling about taking back control ended wwith the queen stepping in and saying fuck you all#but it's not gonna happen#liz is not going to walk into that minefield#Anonymous

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paper代写:British parliamentary system

本篇paper代写- British parliamentary system讨论了英国议会制度。英国议会制度可以追溯到13世纪,迄今已有近800多年的历史。发展到现在,英国议会制度已经改革了很多次,促使着英国的议会制度走向进一步的成熟和完善。尽管英国议会在实际活动中受到许多人的批评,但是从历史和长远看,我们仍然能够发现英国议会活动的高效率,从而保证了国家的稳定和发展。本篇paper代写由51due代写平台整理,供大家参考阅读。

The early parliament was a way for the emerging social class to try to share power, just as the king's advisory body, which gradually evolved into one of the three powers of the country's public power separation and balance. The modern parliament is a legislature of a sovereign state or region whose members are known as "parliamentarians". Members can be directly or indirectly elected or appointed. In general, parliament has the power to sign diplomatic treaties, declare war or ratify peace talks, elect or overthrow the government, and approve government budgets in addition to legislation. In some countries parliament and the power to elect a head of state are the means by which parliamentarians exercise democratic rights on behalf of citizens. The United Kingdom is the initiator of the parliamentary system. As a thing of universal social, political and economic value, the parliamentary system has been recognized, adopted and learned by most countries in the modern world, and has become one of the modern ways of exercising democratic rights. Therefore, the British parliamentary system is called the "mother of parliament".

The British parliamentary system dates back to the 13th century and has a history of nearly 800 years. In 1258, king Henry's intervention in the Italian war, regardless of the crop failure and famine, asked the aristocrats to pay one-third of their income for military expenditure, which aroused the aristocrats' dissatisfaction. King Henry iii's cousin and brother-in-law, Simon? DE? Baron DE montfort led armed soldiers into the palace, forcing Henry to agree to a meeting to sign the Oxford ordinance, which limited the crown. According to the Oxford ordinance, the power of the state is in the hands of a council of 15 men controlled by the aristocracy. A new special term "Parliament" was introduced. The word comes from French and means "consultation", and later in English means parliament. The Oxford ordinance states that the king shall not make any decision without the consent of the council. During the reign of Henry iii, the assembly attended by the monastic and secular aristocracy became the name of parliament, but the king was not willing to lose power and often provoked trouble. In 1264, with the support of the nobles, knights and citizens, DE montfort fought and captured the king. In January 1265, DE montfort, in the name of the regent, convened a meeting under the magna carta of liberty, known as the great conference. Thus began the rudiments of the British parliament. As the representative body of the feudal aristocracy, the grand council consisted of five earls and 17 barons, two more knights and a few lower priests in each county, and citizens were represented in several large cities. However, the parliament at that time could not be equated with the modern parliament.

In 1295, king Edward I summoned a parliament, history says the "model parliament", Kings, nobles, knights and affluent urban citizens political coalition formation, besides big nobility and priest, this session of parliament is fixed to send two knights from each county on behalf of, each two citizen representatives to participate in the big cities, and therefore "grand meeting" a step forward. As the knight and citizen representatives are closely related to each other in fundamental interests and have more common topics, they often gather together to exchange information and discuss countermeasures when such a parliament is held. From 1343, they began to meet alone in Westminster Abbey, gradually forming a house of Commons. Nobles and church elders also form the house of lords. The British bicameral system originated from this. But neither the model parliament, nor the parliament of both houses in 1343, is the modern parliament of universal suffrage.

In 1297, parliament obtained the power to approve taxation. By the 14th century, parliament had gained the power to enact laws. Parliament is also the highest arbiter of political affairs and especially of malfeasance committed by the king's ministers. The formation of the parliament made the king's feudal advisory body gradually become the representative body of the state. The participation of city representatives and the formation of the house of Commons are of great significance to the future development of British history. The rising class of citizens united with the lower nobles, using the power of parliament to approve taxes and pass bills, to limit the power of the crown.

In the early years of the Tudor dynasty, the despot strengthened the role of parliament to some extent. The social foundation of the tudors was the new aristocracy and the new urban bourgeoisie, and the alliance of the crown with these new bourgeoisie and the new bourgeoisie was strengthened by the house of Commons, composed of the middle aristocracy and some representatives of businessmen, while the house of lords was weakened. With the support of parliament, Henry viii carried out a religious reform that freed the church of England from the control of the Pope. The parliament, following the king's will, passed bills which were good for the king and for the new aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, and its activities were expanded. At that time, the parliament was still the king's instrument, and the expansion of the parliament also meant the strengthening of the autocratic monarchy. By the 17th century, this practice of passing various ACTS by parliament, assisted by parliament, had become the legal basis for the bourgeois and new aristocracy to oppose the throne. During queen Elizabeth's reign, when the monopoly of many goods on her minions was so detrimental to the development of industry and commerce, there was an outcry in parliament. The queen reluctantly agreed to stop selling exclusivity to appease parliament. Parliament was also dissatisfied with the king's religious policy. In the 1670s and 1880s, the number of puritans in England increased greatly, and they demanded to leave the church of England, create their own church groups, and guarantee the full independence of the new bourgeoisie in church affairs. And Elizabeth was extremely hostile to puritans, and puritans were persecuted like catholics, but the number of puritans continued to increase. This heralds a rift in the alliance between the authoritarian monarchy and the bourgeoisie. Some of the pilgrims later migrated to North America.

In the mid-17th century, with the progress of the revolution of the new class in Britain, the royal opposition was formed in the parliament, with the industrial and trading class as the main force. They took the parliament as a front, leading workers and peasants to fight against the feudal monarchy, and finally established their own rule through the civil war. However, the feudal forces did not completely disappear from the British political arena since then, and various vassal states remained. The bourgeoisie and the new aristocracy also feared that the populist revolution would finally shake their rule. Therefore, the two parties reached a compromise and formally established the constitutional political system through the "glorious revolution" in 1688.

In 1689 and 1701, the bill of rights and the law of succession were passed, and parliament was confirmed as the highest legislature above the king, marking the true establishment of the parliamentary system in England. Over the next two centuries, the bourgeois revolutions of England and France and the reforms of Prussia and Russia finally brought an end to the feudal autocracy, with parliamentary systems mushrooming above the ruins of feudal royalty and modern parliamentary democracy at its peak.

In the international political practice, many countries are satisfied with the institutional arrangement of the UK, believing that the national machinery has been very perfect and there is no point to it, especially the parliamentary system. But Britain, as the "mother of parliament", is not stagnating, but changing and perfecting the parliamentary system. In addition to the three major changes I have highlighted here, there have actually been several changes and changes in the British parliamentary system. In 1529, a bills committee was formed; In 1554, the voice and the count went together; The third reading of the bill of 1581 was established; James I and Stuart dissolved parliament three times, and even ordered the arrest of members of parliament; In 1628, Charles I's petition of power established the principle of the protection of private property, again emphasizing the supreme power of parliament over taxation; At the end of the 20th century, the upper house reform passed and so on. All this has promoted the further maturity and perfection of the British parliamentary system.

As walter reed, an English scholar, put it, In his letter to the economist in 1865, he argued that Britain's parliament was not "a mysterious entity, but an invention of reason. The advantage of it is simply that it achieves some good objectives, and therefore parliament can be improved by adhering to these objectives and carefully shaping the British constitution towards them. There is no reason to think that our laws, political institutions and governance should not be made to operate like a scientific machine.

Although the British parliament has been criticized by many people for its numerous procedures, complicated procedures, red tape and low efficiency in practical activities, on the other hand, it should be well established and well-formed, and its activities and results can stand the test of time. As the exercise of state power, the handling of public affairs, broad and far-reaching power activities, people have to be cautious, not cautious. In fact, historically and in the long run, we can still find the high efficiency of parliamentary activity in the UK, thus ensuring the stability and development of the country.

要想成绩好,英国论文得写好,51due代写平台为你提供英国留学资讯,专业辅导,还为你提供专业英国essay代写,paper代写,report代写,需要找论文代写的话快来联系我们51due工作客服QQ:800020041或者Wechat:Abby0900吧。

0 notes

Text

Myths

Nations are forged in the fires of history but they remain molten, recast with each generation in the imperfect furnace of memory and imagination.

The controversial French philologist Ernest Renan was right when he once remarked that: “In order for a nation to exist, it had to remember certain things, and also forget certain things.”

The remembering of history often involves simplification, whereas I’d rather reflect its true complexity, with the result that the “agreed-upon facts,” to borrow a phrase from Gore Vidal, regularly need re-examination.

The most critical event in Irish history, without doubt, was the Norman conquest of Ireland in 1169. This was the beginning of English rule in Ireland, which would continue, in one form or another, down to the present day.

The 12th century “Anglo-Norman” conquest of Ireland was, in point of fact, largely Franco-Hibernian in nature. It consisted in an alliance of the Angevin King Henry II (Court Manteau) and the exiled King of Leinster, Dermot MacMurrough.

Henry II was born in France, spoke Norman French, married Eleanor of Acquitane, and spent fully two-thirds of his reign on the continent. The French Normans, in the person of William the Conquerer, had invaded Britain just a century earlier, defeating Harold at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Dermot MacMurrough allied himself with Henry II because he wanted to regain the Kingdom of Leinster, which had been taken from him by Rory O’Connor, the last High King of Ireland.

Jonathan Swift jokingly said that Henry had arrived in Ireland “half by force, half by consent.” The Irish History Reader, published by the Christian Brothers in 1905, puts it succinctly: “Ireland was once an independent nation. She lost her independence not so much through the power of her enemies, as by the folly of her sons.”

Interestingly, one of the first references to Ireland in the historical record, courtesy of Tacitus, the Roman historian, mentions a very similar scenario, in which an unnamed Irish chief, possibly Túathal Techtmar, exiled in the first century, sought refuge with General Agricola, who also thought of invading the Land of Winter.

The Normans were not the only invading power in the British Isles. Scots (Scoti in Latin) was the term used by Roman Britons in referring to the marauding Irish Gaels. In the 6th century, Dál Riata, a Gaelic kingdom in Northern Ireland and Scotland, became so powerful that Gaelic became the language of Northern Britain, hence the provenance of Scottish Gaelic and the etymology of Scotland itself. So, the Normans might have brought English (which is half Norman French anyway) to Ireland, but the Irish brought Gaelic to Scotland. And while we may not speak much Gaelic anymore, at least it’s survived. The Scots (in Scotland) can’t say the same about poor old Pictish. One other example: in 1111, Domnall Ua Briain, the great-grandson of Brian Boru, famous High King of Ireland, became King of the Isles (Hebrides, isles of the Firth of Clyde, and the Isle of Man) by sheer force of arms.

Indeed, the Normans weren’t the only ones boldly interfering in the affairs of a neighbouring kingdom. In 1051, prior to the Norman conquest of England itself, Harold Godwinson sought refuge in Ireland, with Diarmait mac Maíl-na-mBó in Leinster. Harold’s sons, Godwine and Edmund, fled here in 1066, and attempted to retake Britain from their base in Ireland, with fleets supplied by Diarmait, in 1068 and 1069. The colonial history of these islands might have been reversed in the event of their success.

The Vikings were not the only raiders and plunderers on the island of Ireland. According to the Annals, for example, Clonmacnoise was much more often attacked by the native Irish than by the Vikings. Indeed, even the monasteries themselves went to war with one another. Clonmacnoise went to war with Birr in 760, and with Durrow in 764. In 817, during a battle between the monasteries of Taghmon and Ferns, four hundred were slain.

The Battle of Clontarf, in 1014, is often imagined as the last stand of the Gaelic High King of Ireland, Brian Boru, against the marauding foreigner, the Norse King of Dublin, Sigtrygg Silkbeard. In actual fact, Sigtrygg was born in Ireland; he was also married to Brian Boru’s daughter. Brian himself was supported by Vikings from Limerick; and Sigtrygg was supported by Máel Mórda, King of Leinster, and Sigtrygg’s uncle!

The island of Ireland was not politically united until after the arrival of the Anglo-Normans, notwithstanding the exceptional High Kingships of Brian Boru and Rory O’Connor. There never existed a unified political entity called Ireland until about the 16th century, with the Tudor Conquest, the establishment of the Kingdom of Ireland, and the legal process of Surrender and Regrant; even then it took centuries of consolidation. Clearly there was a common heritage amongst the inhabitants of our little island prior to this, in terms of language and customs, but the country was made up of rival kingdoms, each vying for power and glory, just like everywhere else on God’s green Earth.

The omnipresent Catholic Church actually gave its imprematur to the Norman invasion of Ireland, as Henry II was granted the Lordship of Ireland by Pope Adrian IV, the first (and last) English Bishop of Rome. Laudabiliter, the papal bull granting this privilege, is extremely controversial, with many claiming it as a forgery. It matters not. The “Donation of Adrian” was subsequently recognised in many official writings. For example, in 1318, Domhnall O’Neill, along with other Irish kings, appealed to Pope John XXII in an attempt to overthrow Laudabiliter, a copy of which they enclosed. The Pope simply wrote to King Edward II of England urging him to redress some of the grievances of the Irish.

The Irish Rebellion of 1641, a result of anger at plantation and subjugation, gave rise to the Irish Catholic Confederation, which pledged its allegiance to the Royalists in the English Civil War. This is what brought Cromwell to Ireland, and though he was brutal (vicious, really) in his campaign, he was not the first military leader to massacre innocents, and exacerbate famine in Ireland. Robert the Bruce, and his brother Edward, who was proclaimed High King of Ireland in 1315, invaded the North and engaged in total war with the Anglo-Irish, slaughtering all of the inhabitants of Dundalk, for example.

Maurice Fitzgerald, who led one of the Cambro-Norman families which accompanied Strongbow in his invasion of Ireland, founded a famous dynasty in Kildare. The Fitzgeralds, like many of the Old English, eventually became “more Irish than the Irish themselves,” Hiberniores Hibernis ipsis. In fact, two descendants, separated by more than two-hundred years, would lead the Irish in rebellion against the crown: “Silken” Thomas Fitzgerald, in 1534, and Lord Edward Fitzgerald, in 1798. Such are the vagaries of history.

I like to remind Nationalists and Unionists alike that, during the 1680s, Pope Alexander VIII supported William of Orange, the Protestant usurper, in his battle for the English Crown, against the legitimate (though Catholic) King James II. The Orange Order, which refuses Catholic members, should make an honourary exception for the Pope. The Catholic Church, not for the first time in history, placed its own interests to the fore, as a member of the Grand Alliance, the League of Augsburg. The Battle of the Boyne in 1690 more or less decided the outcome of this conflict in favour of William.

This “Glorious Revolution,” so-called, is often celebrated as a victory for the liberal co-regency of William and Mary, over the authoritarian regime of James II. Edmund Burke thought of it as a final settlement and as freedom in full fruition. James was indeed an advocate for absolutist monarchy and a believer in the Divine Right of Kings.

However, it was James who made the declaration of indulgence, otherwise known as liberty of conscience, in 1687, a first step towards the freedom of religion. Indeed, the Patriot Parliament, which met in Dublin for the first and only time in 1689, granted full freedom of worship and civic and political equality for Roman Catholics and Dissenters. And yet, the indulgence also reaffirmed the king as absolute, so these pronouncements depended on the will of the monarch. (They were also made with a view to reinforcing support for his reign amongst Catholics and Dissenters.)

The founding members of the United Irishmen, the fons et origo of Irish republicanism, were all Protestant. This was an astonishing development. In the wake of the American and French revolutions, the Protestant planters, who had been brought to Ireland to pacify the country and bring it under English control, were now making common cause with the Gaelic and Old English Catholics to throw off the yoke of external domination. Wolfe Tone would state his aims boldly:

To subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country – these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of all past dissentions, and to substitute the common name of Irishman, in the place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic, and Dissenter – these were my means.

In the aftermath of the 1798 rebellion, Catholics supported the Act of Union, because they believed that Catholic emancipation would be more easily achieved through Westminster than through College Green.

Daniel O’Connell, a native speaker of Irish, was utilitarian enough to “witness without a sigh the gradual disuse” of the language. Rather surprisingly, it was not the Duke of Wellington who said that being born in a stable — Ireland — does not make one a horse, it was the Liberator, speaking about the Duke, at trial in 1843.

O’Connell desired Catholic emancipation, of course, and the re-establishment of the Irish Parliament, but he wasn’t a separatist. In fact, he actually coined, or at the very least popularised, the term “West Brit,” then understood in a wholly positive sense. Here he is speaking in the House of Commons in 1832:

The people of Ireland are ready to become a portion of the Empire, provided they be made so in reality and not in name alone; they are ready to become a kind of West Britons if made so in benefits and in justice; but if not, we are Irishmen again.

O’Connell, who witnessed the beginning of la terreur in France, believed in peaceful agitation for change, “moral force” nationalism, and wholeheartedly rejected violence. “Let our agitation be peaceful,” he said, “legal, and constitutional.”

The principle of my political life…is that all ameliorations and improvements in political institutions can be obtained by persevering in a perfectly peaceable and legal course, and cannot be obtained by forcible means, or if they could be got by forcible means, such means create more evils than they cure, and leave the country worse than they found it.

In his non-violence he would be an example to Gandhi and to Martin Luther King, but not to the rebels of 1916. Strangely, though, you can find Robert Emmet’s blunderbuss in O’Connell’s home in Derrynane.

Two UK prime ministers were born and raised on the island of Ireland, part of the Protestant ascendancy: William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelbourne (1782-1783) and Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1828-1830). These men also share the distinction of being the only two prime ministers who were also army generals. Wellington is not well-remembered in Ireland, because he was a staunch unionist and opposed to parliamentary reform (the reason Lord Byron called him Villainton), but he was Prime Minister during the passage of the 1829 Catholic Relief Act, and it would not have passed without his forthright support. The Wellington Testimonial in the Phoenix Park celebrates, somewhat amusingly, his encouragement of religious and civil liberty.

Irish soldiers fought with the British Army in almost every battle in the Empire’s history, including a large contingent in the Napoleonic wars alongside Wellington and, of course, in the Great War. At least 200,000 Irish soldiers fought in the First World War, all of them volunteers. Conscription for Ireland was eventually passed in 1918, but never enforced. The history of the British Empire is also our history, whether we like it or not. In fact, many of the troops who battled with the rebels in 1916 were fellow Irishmen, particularly from the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Ireland being an integral part of the Empire meant, for example, that the bugle used to sound the Charge of the Light Brigade at the famous Battle of Balaclava in 1854 was made in Dublin, at McNeill’s on Capel Street, and sounded by a Dubliner, Billy Brittain. It meant too that Winston Churchill’s “first coherent memory” is of cavalry on parade in the Phoenix Park in Dublin, when his grandfather, the Duke of Marlborough, was Viceroy. (Speaking of historical myths: it’s actually Lord Kitchener, as Secretary of War, and not Churchill, who bears most responsibility for the disaster which was the campaign in Gallipoli. He was the chief advocate for a naval attack in the first place and for a subsequent landing of ground troops.)

The Ulster unionists, latter-day proponents of democracy, law, and order, would do well to remember that it was their forebears who first introduced the gun into Irish politics in the 20th century, with the Larne gun-running in 1914. These were German guns for the Ulster Volunteer Force, who were determined to oppose Home Rule, the democratic will of the majority, by any means necessary.

The Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), the majority nationalist party at Westminster, was opposed to partition, but acquiesced in the creation of Northern Ireland as a stop-gap in securing Home Rule for Ireland, which was delayed until after the First World War. John Morley, previously Chief Secretary for Ireland, wrote to Asquith in 1914 very wisely telling him that his special plan for Ulster “would not work,” because “there is a strong Catholic minority, and the effect would be to reproduce in Ulster, with a reversal of the political conditions, the very antagonisms that you now hope to relieve.” The creation of “a Protestant Government for a Protestant people” in Northern Ireland would lead directly to the so-called Troubles, in which Catholics were thwarted in their pursuit of basic civil rights.

The 1916 Rising was organised while Home Rule was on the statute books. The best defense of this action was probably given by Roger Casement, the campaigning British consul who had exposed the human rights abuses in the Congo and Peru, at his trial in 1916 before he was hanged for treason:

If small nationalities were to be the pawns in this game of embattled giants [the Great War], I saw no reason why Ireland should shed her blood in any cause but her own, and if that be treason beyond the seas I am not ashamed to avow it or to answer for it here with my life.

Tom Clarke, the mastermind of the Rising, had been arrested in London in 1883, found in possession of large quantities of nitroglycerin, intent on bombing London Bridge, the busiest part of the city.

Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin, had suggested the formation of a dual monarchy, in emulation of Hungary’s settlement with Austria, essentially a return to the constitution of 1782, prior to the union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and he had opposed all physical force nationalism in favour of passive resistance and abstentionism.

Patrick Pearse talked in the language of race theory, and welcomed the spilling of blood in the world war: “the old heart of the earth needed to be warmed with the red wine of the battlefields.” One might dismiss this as representative of the militarism of the age, but there were many who completely disagreed. James Connolly condemned this sentiment as belonging to that of a “blithering idiot.” Indeed, Pearse was “half-cracked,” according to Yeats, and a man “made dangerous by the Vertigo of Self Sacrifice.”

It must also be remembered, though, that John Redmond also called for a blood sacrifice, in encouraging the Irish Volunteers to join the war effort on the continent: “No people can be said to have rightly proved their nationhood and their power to maintain it until they have demonstrated their military prowess.”

Independence finally came in 1922, with the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the formation of the Free State. The Dáil ratified the Treaty, and the 1922 general election was a de facto referendum resulting in a clear majority in favour of the Treaty. The anti-Treaty republicans rejected this result, and brought the country to civil war. This anti-democratic element of republicanism is discussed not nearly enough.

Was the Treaty a worthy intermediate, a legitimate stepping stone to full independence? or was it a simple betrayal of the Republic? If you believe it was for the Irish people to decide, the Treaty was their choice. If, however, you believe that the Republic itself takes precedence over the voice of the people, then the fight would go on. Margaret Pearse rubbished the Treaty because she was haunted by the “ghosts of her sons.” In the end, the Republic was declared in 1949, not through force of arms, but through legislation.

In retrospect, the old unionist concern that Home Rule meant Rome Rule wasn’t entirely unfounded. Our constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann, which was written in 1937, defined the state as explicitly secular, and, remarkably, provided recognition to the “Jewish congregations,” then under increasing attack in Europe. Nevertheless, the Catholic Church had inordinate influence on social policy. This would drive a wedge into the midst of the nation, to paraphrase W. B. Yeats. A 1925 prohibition on divorce prompted Yeats, then a senator in Seanad Éireann, to give an impressive speech.

I think it is tragic that within three years of this country gaining its independence we should be discussing a measure which a minority of this nation considers to be grossly oppressive.

Ironically, in the office of the ultra-Catholic Patrick Pearse at St. Enda’s in Rathfarnham sits a bust of the poet John Milton. It was Milton who had written so powerfully in favour of divorce in the 17th century, and Yeats invokes his name in support of the rights of the Protestant people.

The prohibition went ahead anyway, having a predictable effect on progressive society: in 1951, for example, the state rejected the donation of a painting from Louis le Brocquy, Ireland’s foremost artist. A Family was a pessimistic depiction which he painted while going through a public divorce in the UK.

Yeats predicted that the ban would eventually be removed. “There is no use quarreling with icebergs in warm water,” he said. “I have no doubt whatever that, when the iceberg melts [Ireland] will become an exceedingly tolerant country.” The iceberg finally melted in 1995, when divorce was legalised, by the smallest of margins, through popular referendum.

In the 1950s, in the wake of the failure of the “controversial” Mother and Child Scheme, which witnessed overt interference from the Catholic Church in the affairs of a supposedly secular state, and following the resignation of the courageous Dr. Noel Browne, then Minister of Health, Taoiseach John A. Costello was bold enough to state:

I am an Irishman second, I am Catholic first, and I accept without qualification in all respects the teaching of the hierarchy and the church to which I belong.

Is it really any wonder that Catholics were viewed with suspicion by protestants in the UK and elsewhere? Indeed, Martin Luther King Sr., a Baptist pastor and the father of the great civil rights leader, could not bring himself to support John F. Kennedy in the presidential race of 1960 solely because he was a Catholic. Kennedy eventually settled this matter once and for all in a brilliant speech to an antagonistic audience, all members of the Protestant Greater Houston Ministerial Association. He said, in essence, the complete opposite to John A. Costello.

In the 1960s, the provisional IRA gained a foothold providing protection to the Catholic community in the North who were agitating for basic civil rights. They abandoned their moral high-ground, though, by exploding bombs and killing civilians. In 1885, the Fenians had simultaneously bombed the Tower of London and the House of Commons; in 1974, the provisional IRA did the exact same thing. Again echoing history, their goal of a united republic was never achieved. The old IRA had fought for a Republic but settled for a Free State, the provisional IRA fought for a Republic but settled for a Power Sharing Executive.

The Irish History Reader, reflecting on the divisions of the past, encourages its students to “avoid dissension, and shun all that might tend to create disunion.” I would suggest the opposite, we are a diverse nation of contradictions. There’s room for all points of view. We should give oxygen to all traces of disagreement, welcome any tentative hints of polarisation. After all, friction creates heat and heat produces light.

0 notes