#wifeliness

Text

Sex with Russian

Ember Stone Tiny Teen Creampie Hookup

musclle rough

Succubus Karma RX struck with big cock and cum sprayed

Pale busty bbw whipped at orgy

Fat gay old men young boys and latin nude first time Sleepy Movie

Melissa Lynn the MILF porn goddess fucked POV style

Topless bikini teen catches and sucks voyeur

Cum hungry milf gloryhole first time Noise Complaints make messy

Alexis Fawx disguised herself to fucked her stepdaughter Mackenzie Moss again

#lacquer#stakes#resipiscent#gaspers#solicitrix#Midland#unparched#raison#self-ruling#Kure#dallack#semiflosculous#McAndrews#pyro-acid#Leonato#OMM#generalized#founce#wifeliness#detinet

0 notes

Text

if aymeric is Our Lady Wife and nori is my daughter than does that make him noris Honorable Stepmother or is he her Lady Wife as well

#ffxiv#aymeric de borel#the answer is nori is included in the Our#aymerics wifeliness transcends gender sexuality or relationship status it simply Is

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

ECLIPSE IS NOT WIFELINESS ANYMORE Hehehehe

sketch heheh

oc :@angyy-eugh

AU: @sunnys-aesthetic

Eclipse from fanfic 'Sleuth Jesters' by @naffeclipse

#moondrop#fnaf moon#sundrop and moondrop#sundrop#moon#fnaf sun#new moon#sun and moon au#sun and moon fnaf#sun and moon fanart#he is not wifeless anymore btw#sleuth jesters#cute boy i love him :)🥹💕

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

I mean yeah it fucking sucked but like

The sheer wifeliness of season 6.

21 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Anne has always been the star of the Six Wives show; a fit match for Katherine of Aragon; not in length of stay (Katherine was officially queen for more than two decades, Anne for only the famous thousand days), but in influence; in the neat counterpoise of old religion and new; in seeming to reflect different models not just of queenship but of wifeliness and femininity. By comparison with these two titans the other four wives, as David Starkey pointed out, were "creatures of the moment"; Starkey being the latest of the high street big hitters - Antonia Fraser, Alison Weir - to tackle all six.

Eric Ives revisits the life of Henry VIII's most influential queen [...], Sarah Gristwood

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

>>

question

what to y'all think my voice sounds like? like, how do you read my posts, any accents or weird pitches or whatnot?

if you can't describe it, then just tell me, like, a character or person that sounds similar

<<

Since, you're Hera, you're the Goddess of crafts, queenliness, and wifeliness, and since old brits are the people who get cast as Gods, you would sound like Dame Maggie Smith in my head, if my brain didn't have a bit of aphantasia in that range and I heard a voice in my head for the text I read.

I mean, i don't sound THAT old

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A very long-winded essay about why I love Night in the Woods and The Ramayana makes me Big Mad ft. Lets Talk About Mental Illness™

So I was in this class called 'The Ecology of Language". Excellent class, 10/10 would recommend - and especially relevant in the Indian context in particular, but that's a topic for another day.

One of the things we talked about was the concept of 'relatibality' in media, which, I'm sure we can all agree is a large component of contemporary character or story-line development. Considering the context of modern readers, what that sometimes ends up looking like (in our society that is built on constantly being told we are lacking, and the subsequent need to satisfy manufactured desires), is some wonderfully nuanced characters in stories stories that are three-dimensional, well rounded, and well developed and written. It's pretty great.

And sometimes, what that means is that we have excellent characters that don't conform to the standard 'protagonist' stereotype. They might not even be 'good' (this is NOT a villain-apologist post). In fact, they might be complete idiots. They might be the people in stories who make all the wrong choices.

One such relatable character is Mae, and it's because she's an unmitigated train-wreck.

Anyone who knows the game probably knows what I'm talking about when I say the illustration style and character designs are gorgeous. Anyone who's ever dissociated probably knows what I'm talking about when I say that illustration style and character design were excellently used to create the sort of subliminal, surreal state of Mae's mind. And as you play the game, you see how that state of mind plays with the other characters, and - spoiler - it isn't great.

This is the first of the relatable aspects of Mae’s character; there are people around her who love her and are worried about her, but at the same time, are angry and irritated about her behaviour. At what point does it become too much to ask of those around you to forgive all your continuous and repetitive mistakes? Even if you have a good reason for it, mental illness is not an excuse for being exploitative, even if it is unintentional. Mae is not trying to hurt the people around her, but she constantly needs emotional labour from them – it’s exhausting, and people’s patience is going to run out eventually, as is their right.

Another aspect of this behaviour is the lack of reciprocity, an example of this being when Bea’s mother died of cancer – and Mae didn’t even notice.

There are several instances of Mae’s thoughtless behaviour throughout the game; she gets completely wasted and makes a scene at the party, gets jealous of of Greg and Angus because they’re leaving the town without her, and ends up destroying the radiator Bea was supposed to fix, getting her in trouble.

The thing is though, that Mae is given the opportunity to fix her mistakes.

A large part of relatability is the want so see yourself in a character. Mae is relatable to me because there are several circumstances and events in our lives that match up, but more than that; the game is an interactive visualization of her healing process. Her nine steps, if you will. She is given a second chance – and that chance is hard won, particularly in the context of the game.

Mae talks about feeling like she’s falling behind, of knowing that she is, in a way, wasting an opportunity that was a privilege in the first place, especially considering her family’s financial situation – but at the same time, being literally unable to help herself. And the aspects of the gameplay that hint at the supernatural elements of the story possibly being a figment of Mae’s imagination – well. All us depressed losers know what it's like to not be able to trust your own judgement and point of view. She talks about why she dropped out of college, and her description of the dissociation, and the mental and emotional deadening that it causes is spot on and so well represented.

It underscores the point that the logical brain knows that mental illness is an illness like any other – but the emotional brain doesn’t care.

The game does a brilliant job of laying bare the realities of middle class life, and makes painfully clear the fact that, at that level, it doesn’t matter how difficult things are for you. The world isn’t going to wait for you to get back on your feet.

Mae’s mental state and the limitations it imposes on her cultivates a state of extreme frustration. Again, relatable. It’s an understated aspect of illness of any kind; the anger at yourself, and how that anger carries over into a lot of things in your day to day life. After a point, it becomes a habit. Mae does this too; she's belligerent, and instigative, and unrepentant of consequences, because anger blinds you.

It's not how things will always be. I have the privilege of hindsight, so I can say that with authority. But, this isn’t the kind of thing that ever fully leaves you, either. If you break a kneecap, it’s going to bother you for the rest of your life, and similarly, mental illness has a ‘no return, no refund’ policy. So you grow up, and you try to adapt those habits and impulses into a more positive context. Recycling, right? Maybe you set your sights on things that actually deserve your anger, and you go from there. You find people who, for their own reasons, perhaps or perhaps not related to your own, are angry.

And you don’t understand the people who are not.

A large part of the anger and frustration surrounding mental illness is due to the stigma surrounding it. It’s frustrating to be so powerless and dependent, but this is exacerbated by the attitude of ‘it can’t be that bad’, which makes it so difficult to reach out, to be able to say, ‘I need a break’ – and actually get one. This is an attitude that carries over to a lot of other issues as well, and the worst part is – we are surrounded by people who are okay with it, who believe in and support that mentality.

The myth of Sita, for example. She is a strong female figure in Indian mythology, who overcomes her circumstances to live a ‘good’ life, and for all intents and purposes, is a hell of a role model.

But that’s the thing; her life wasn’t good, was it? She was supposed be a goddess reincarnated, she should have been powerful, and respected, but instead she is reduced to ‘wife’ – and everyone today is fine with it.

I respect her immensely for the choices she made; marrying for love was her choice, going into exile with her husband was her choice. She was the paragon of virtue, of 'wifeliness', of kindness – she chose her husband over everyone and everything else, including herself, as was expected of her. But yet – she couldn't win his trust or respect. It should not even have needed to be won.

It’s commendable the way she takes it all in stride, but why did she? She was kidnapped and held captive for years, entirely against her will, and her husband's response to that is to force her to walk through fire to prove her ‘purity’ – and she does it. And she stays with him after, and I cannot understand the depths of her patience and forgiveness, because I would have been livid, and I want her to be so too. I’m furious for her, because Ram was not just her husband, he was also the king, and his later verdict to exile her, alone, while heavily pregnant, his readiness to condemn her based on speculation and public sentiment, was not just a verdict against her, it was against every woman in his kingdom who had ever been victimised.

Sita became a martyr to the modern feminist movement – if she could not be angry on her own behalf, we will do it for her. But at the same time, she is still relatable, because we are held to a slightly lesser degree of the same expectations. There are always going to be aspects of things that you relate to. ‘Big Mood’ culture is a strong indicator of the human ability to empathise, especially with characters that you like, or respect.

Sita’s world, I imagine, was run by the expectations her society and community had of her, and maybe she didn’t even have the liberty to be angry. Who is responsible for portraying her in passive acceptance of her fate? Is that representation reliable? Would the story have been different had it been written by a woman?

I can't remember a time when I was not angry, especially about things like this. I am always ready to fight, and I think the same goes for so many other people today, sometimes to our detriment. I cannot imagine a world where that was not at the very least an option. Not necessarily the best option, - but Sita’s world was very different to ours. Even with centuries between us, we’ve just gotten over angry and depressed women being labelled as ‘hysterical’ and subsequently being locked away. What is it like, to have to be calm and careful in response to being treated like this? This care in response may not be an overt requirement anymore – though the fact remains that society will not take you seriously if you become hysterical - but shouldn't you, at the very least, be able to rely on the support of other people in the same boat?

That is the main difference in these stories, and another main point of relatability to me; Mae, like myself, had a support system. Sita did not. Mae was selfish and demanding in so many ways, and required a lot of time and patience and healing before she was able to give back, but she got there eventually because she was able to put herself first. She fought for herself, and when she couldn’t, she had other people to fight for her. Night in the Woods represents the intersection of oppressed minorities and community with their portrayal of Mae, Greg, and Angus in particular, and the importance of community support – and, the difference between geographical community, and communities formed through camaraderie and actual unity. And so does the Ramayana - except, where was Sita’s community? Where were her sisters, or her parents, when she was abandoned in the woods, and later when she committed suicide? We are well aware, in the modern day, of the state of mind that causes people to kill themselves, and yet that is a part of the story that we never talk about. Where were her people then?

What would have happened if she had been more like Mae, and put herself first instead of bleeding herself dry for people who never respected her, and would never do the same for her?

People relate to personalities. They relate to choices, and circumstances, and habits, and it is neither a good nor a bad thing, to be relatable or not. Sita will be highly relatable to people who, like her, were governed by their circumstances, and were screwed over despite their best efforts. People who felt they couldn’t, or shouldn’t exercise their power and agency. Sita’s death was at odds with her strong personality, and so was her deference to her fate on many occasions, but there are a lot of people out there who will relate to the feeling of simply wanting things to be over. Mae on the other hand; she’s a steamroller, and she doesn’t stop. There’s a reason her character is a cat, and jokingly referred to as feral in the game. She is persistent, she is growing.

[1] In Defence of Kaikeyi and Draupadi: a Note – by Fritz Blackwellhttps://www.jstor.org/stable/23334398?read-now=1&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[2] https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2015/10/emergency-room-wait-times-sexism/410515/

90 notes

·

View notes

Note

💋( amycus & marlene ) + @smotheredtragedy

kiss my muse out of nowhere ( accepting ) + @smotheredtragedy // amycus

( wanted to try something different lol )

dear diary –

today was a strange day; mother and father had me round for the summer this year instead of being sent off with relatives or me simply taking off to spend it with the girls. 3 weeks, they asked for, and we’d stay in the ancestral home in scotland, by the lakes i grew up around, and it’d be a lovely time. i didn’t think they’d have the carrows there, but then again, i feel it’s not often there’s a double meaning, under, everything that they do.

but it was beautiful... and amycus was there. still all straight backed, no fun, amycus, but he was looking at me strange and asked if i knew why he was here, and i’d thought maybe it was because they’d wanted to be there for my 16th birthday but he’d let me know then the whole point behind all this, which was, as i suspected, some means to an end with a marriage proposal there at the end of it.

i didn’t really answer him but i asked him to come by the lake with me, even though it was dark. jumped in when he wasn’t looking though, maybe he stared at the clothes i left behind in my haste, and, it was kind of fun, you know... watching him from the water. maybe i was mean to say, ‘how could i ever think of saying yes when you won’t even say yes to something like this?’ in getting him to jump in, but when he did that was kind of magic too.

i didn’t say yes to the marriage. but i did get to kiss him for the first time then, beneath a full moon, in the middle of a lake in scotland and maybe that’s better than any supposed wifeliness he could have expected out of me. i told him he didn’t want me, not really, not in the ways that it counted, but he still kissed me like it could be true, and, maybe just a little bit, i really loved that. the maybe. how thrilling the unknown is, to a girl who loves to know it all.

#smotheredtragedy#❝ m. mckinnon ❞ ┆ canon verse ┆ telephone wires above are sizzlin like a snare !#❝ m. mckinnon ❞ ┆ meme reply ┆ as you colour me blue !

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

By Elizabeth Carolyn Miller

The Perils of Public Visibility

Conan Doyle’s resistance to visually identifying the female criminal sometimes appears, nonetheless, as a denial of women’s public subjectivity, a refusal to grant women full citizenry by refusing to grant them full criminality. The anonymous female avenger in “Charles Augustus Milverton” perfectly exemplifies this tendency in the series. Despite the violence of the murder she enacts, Holmes keeps her publicly invisible by chivalrously covering up her deed; her name remains a secret even to readers of the story. This is not the only case where Holmes opts not to pursue legal redress after discovering a crime, but it is the most obviously illegal instance, since he actually witnesses the murder. On the night in question, Holmes and Watson break into the home of Milverton, a blackmailer, to secure some letters written by Holmes’s client, Lady Eva. While searching his study, they inadvertently witness Milverton’s meeting with a lady’s maid who has offered to sell him her mistress’s letters. Page 63

"You couldn't come any other time—eh?"

Fig. 14. From “Charles Augustus Milverton”

Page 64

The maid turns out to be a former victim in disguise. Milverton previously exposed her secret letters to her husband, who died from the shock, and she has returned to enact revenge.

In describing the interplay between Holmes, Milverton, and the avenger, Conan Doyle orchestrates a complicated interplay of the visible and the invisible. An illustration of the avenger shows her thickly veiled—utterly obscured by the accoutrement of feminine propriety (figure 14). Secreted behind a curtain, Holmes and Watson witness her visual revelation: “The woman without a word had raised her veil and dropped the mantle from her chin. It was a dark, handsome, clear-cut face which confronted Milverton, a face with a curved nose, strong, dark eyebrows, shading hard, glittering eyes, and a straight, thin-lipped mouth set in a dangerous smile” (171). While suggesting formidability, this description counters the visual criminal theory of criminologists like Lombroso, who claimed female criminals have racialized or masculine features such as a heavy jaw (102). The avenger speaks:

“It is I … the woman whose life you have ruined. … you sent the letters to my husband, and he—the noblest gentleman that ever lived, a man whose boots I was never worthy to lace—he broke his gallant heart and died. … You will ruin no more lives as you ruined mine. You will wring no more hearts as you wrung mine. I will free the world of a poisonous thing. Take that, you hound, and that!—and that!—and that!—and that!”

She had drawn a little gleaming revolver, and emptied barrel after barrel into Milverton’s body, the muzzle within two feet of his shirt front. … Then he staggered to his feet, received another shot, and rolled upon the floor. “You’ve done me,” he cried, and lay still. The woman looked at him intently and ground her heel into his upturned face. She looked again, but there was no sound or movement. I heard a sharp rustle, the night air blew into the heated room, and the avenger was gone. (171–72)

This passage depicts one of the most violent murders committed by a woman in turn-of-the-century fiction, and its graphic illustration brought that violence home to readers (figure 15). Despite the woman’s ferocity, however, Conan Doyle takes pains to rationalize—even defend—her act. Her invocation of her husband and her insistence on her own humility position her squarely in the tradition of self-renunciatory Victorian wifeliness. The scandalous letters do not challenge this characterization:Page 65

"Then he staggered to his feet and recieved another shot."

Page 66

we know from Lady Eva’s case that most of the letters in which Milverton traffics were written when the women were young and unmarried, and Holmes describes Lady Eva’s letters as “imprudent, Watson, nothing worse” (159). Watson’s reference to Milverton’s killer as an “avenger” also serves to justify her act, as does her seemingly selfless invocation of Milverton’s future victims.

Holmes and Watson choose not to expose the avenger. When Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard tries to enlist Holmes’s help in solving the case, obviously unaware that he witnessed the murder, Holmes replies, “there are certain crimes which the law cannot touch, and which therefore, to some extent, justify private revenge. … My sympathies are with the criminals rather than with the victim, and I will not handle this case” (174). Even in the moment of watching the woman unload her pistol into Milverton’s breast, while Watson reacts, Holmes holds him back:

No interference upon our part could have saved the man from his fate; but as the woman poured bullet after bullet into Milverton’s shrinking body, I was about to spring out, when I felt Holmes’s cold, strong grasp upon my wrist. I understood the whole argument of that firm, restraining grip—that it was no affair of ours; that justice had overtaken a villain. … But hardly had the woman rushed from the room when Holmes, with swift, silent steps, was over at the other door. He turned the key in the lock. At the same instant we heard voices in the house and the sound of hurrying feet. The revolver shots had roused the household. With perfect coolness Holmes slipped across to the safe, filled his two arms with bundles of letters, and poured them all into the fire. Again and again he did it, until the safe was empty. Someone turned the handle and beat upon the outside of the door. … “This way, Watson,” said he; “we can scale the garden wall in this direction.” (172–73)

Holmes not only keeps quiet about the murder, but seizes the opportunity to actively cover it up and destroy all of the compromising letters in Milverton’s safe. Committed in cold blood, with premeditation, this crime would presumably be quite disturbing to contemporary readers: a woman shooting a man with a phallic gun in his own study is a perfect example of the kind of invading and destructive threat that characterized many representations of first-wave feminism.[34] In covering the woman’s act, however, Holmes ensures that the avenger will remain outside of the public forums of the newspaper, courts, and legal system. Indeed, the female avenger remains anonymous even on a metafictional level, for Watson refuses to reveal her name even to the “public” readership of the story.

Conan Doyle’s discomfort with women in public cannot alone account for his shocking and remarkable female avenger, however; it does not explain why he makes her at once so appalling and so appealing. He takes a potentially threatening woman and normalizes her by providing justification for her act and presenting her as a loyal and loving wife; but he goes on to present her, like Irene Adler, as an object of public desire, idolization, and glamorization. At the end of the story, gazing into “a shop window filled with photographs of the celebrities and beauties of the day,” Holmes recognizes what we might call the “mug shot” for the anonymous avenger:

Holmes’s eyes fixed themselves upon one of [the photographs], and following his gaze I saw the picture of a regal and stately lady in Court dress, with a high diamond tiara upon her noble head. I looked at that delicately curved nose, at the marked eyebrows, at the straight mouth, and the strong little chin beneath it. Then I caught my breath as I read the time-honoured title of the great nobleman and statesman whose wife she had been. My eyes met those of Holmes, and he put his finger to his lips as we turned away from the window. (174–75)

Shop window photography promoting “celebrities and beauties of the day” was part of the new visual landscape of Victorian consumerism. Just as magazine illustrations and newly visual textual formats transformed the medium in which readers encountered crime fiction and other narratives, the display of famous women’s photographs as a means of selling products helped shift public culture toward the visual, consumerist, and feminine. Here, Conan Doyle portrays one such woman—displayed in all her aristocratic splendor to encourage others’ consumption—as a murderer, a sharp distinction from what she appears to signify on a visual, imagistic level. The Holmes series on the whole presents criminality and truth as visually ascertainable categories, but when depicting female criminality, it suggests that the orchestration and framing of an image determines its meaning. Here, the murderer’s photograph is a marketing tool, not a revelation of essential identity. Rather than a low brow, sensuous lips, or a misshapen ear, she has a tiara. The photograph represents the avenger’s invulnerability: she gets away with murder in part because of her social standing, but more obviouslyPage 68

"Following his gaze I saw the picture of a regal and stately lady in court dress."

Page 69

because of her image. Conan Doyle’s depiction of the avenger encapsulates the entire series’ ambivalence about the female criminal, who represents a newly roused feminist power, the failures of patriarchy, and the consumerist appeal of feminine disobedience. The anonymous avenger is not a figure of criminal degeneracy, but of glamour and beauty; she is appealing rather than repulsive to readers. As the illustration accompanying this scene shows, she is literally a representation for the public to admire (figure 16). Thus, while Conan Doyle’s stories do commodify feminine victimization, their commodification of feminine violence and criminality is even more significant. At a historical moment when a faction of the suffrage campaign was becoming ever more violent in its acts of civil disobedience, Conan Doyle’s 1904 story banks on the allure of feminine disobedience for readers. The avenger puts the anger of first-wave feminism into an exquisite, consumable package. Like other female offenders in the series, her image and body project fantasy and glamour rather than criminological stigmata; she suits a consumerist model of vision rather than an anthropological or criminological one. In consumerist discourse, as I discuss in the introduction, to be visible and noticeable is a form of power rather than submission. Late- nineteenth-century advertisers and marketers preached, unlike Holmes, that it was better to be looked at than to look. They also defined, however, what kind of feminine embodiment was worthy of the gaze. Consumerism redefined femininity as public and visible, but only when it conformed to the logic of consumerism.

Given the series’s apparent investment in a criminological theory of vision, one would expect its female criminals to be easily identifiable, but envisioning women is an activity fraught with problems for Holmes, the otherwise expert eye. Women criminals prove capable of resisting the detective’s gaze, and Conan Doyle makes a sustained case for legal interventionism, which he associates (not unproblematically) with state feminism rather than state paternalism. Thus, at the turn of the twentieth century, Conan Doyle’s stories put forth a far more compound and ambivalent theory of gender, vision, and the public than has been previously acknowledged; they support the authority of the gaze and locate ontology in image, except when depicting women criminals. In these instances, Conan Doyle’s detective fiction prefigures filmic genres like film noir, in which femmes fatales reveal a great “truth” about the visual landscape of modern urban culture: that the unknowable is not signified by the invisible, but by a peculiarly modern disjunction between the visible and the real.”

This is an interesting article but it reminded me wasn’t there a meta or mention of a theory saying that it might have been Holmes who actually killed Milverton?

@sarahthecoat @ebaeschnbliah @raggedyblue @therealsaintscully

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

No, she ‘is’ a poet.

Hughes took Plath’s talent as seriously as she did and encouraged her to move beyond the sometimes stilted, thesaurus-heavy verse of her apprentice years; she, in turn, helped introduce him to contemporary American poetry that then left its mark on his own work. In 1962, when a Devon neighbor came round for tea and asked, “Does Sylvia write poetry, too?” Hughes responded, “No, she is a poet.” He had dared her to choose the artistic life she truly wanted over the comfortable bourgeois life her mother had carefully planned. Plath, always eager to show she had “guts,” took the gamble. Together, Plath thought, they would fly close to the sun: “no precocious hushed literary circles for us: we write, read, talk plain and straight and produce from the fiber of our hearts and bones.” She knew she was breaking new ground in her own creative marriage as writer rather than muse. In her journal she wrote, “there are no rules for this kind of wifeliness—I must make them up as I go along & will do so.”

— Heather Clark, Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath (Knopf; October 27, 2020)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The show is titled Gilmore Girls for a reason, because it centers around the lives of the three Gilmore women generations, but across those generations, Richard Gilmore remains an important anchor, which is why it is so interesting to see how they each react so similarly, and differently at the same time, towards the possibility of his death.

Emily is afraid of Richard’s death because the first twenty years of her life were a build up to marriage, wifeliness, and motherhood, and after she met Richard, her whole life came to be intertwined with his. She has known little beyond a life with Richard, so the idea of losing such an important piece of her life is not only heartbreaking, but scary. Emily would much rather die than live a life without Richard.

Lorelai has, similarly, never lived a moment without knowing of her father, it’s quite impossible of her to do otherwise, and yet knowing of her father isn’t the same as knowing him. While she also faces the same fear as Emily of losing someone she has always had in her life, in one way of another, Lorelai instead worries of the moments her and her father never shared. She doesn’t have fond memories with her dad, and that fact scares her because, despite years to make such memories, they never did, and Lorelai does not want to lose her father with nothing to say for their relationship.

On the final end of the spectrum, Rory shares a familiar fear of losing Richard without ever really knowing him, but her situation varies in the fact that she only recently began to really communicate with Richard, and she never before realized how fleeting their time may really be.

Three women. Three relationships. Three motivations. One fear.

#Gilmore girls#gilmore girls review#season 1#episode 10#1.10#richard gilmore#emily gilmore#lorelai gilmore#rory gilmore

261 notes

·

View notes

Text

the very specific media aesthetic based around Wifeliness aimed at abusive men who would get their asses divorced in world record time

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Girls night out slash date night outfits are traditionally taken in the toilet for me. Because my outfit photographers are asleep since 7:30pm. My dresses are typically cross over style for bfeeding access. Chapter: Style Enthusiast #chapterstyleenthusiast #rielanini #styleenthusiast #Summer #Australia #datenight #ootn #ootd #whatiwore #blackonblack #mamaswag #momstyle #mumstyle #breastfeedingmama #breastfeedingoutfit #septum #rogueone #marriedtoastarwarsfan #wifeduties #wifeliness #marriage Signed, Wife of a Star Wars Fan

#breastfeedingmama#summer#australia#rogueone#styleenthusiast#datenight#rielanini#septum#mumstyle#wifeduties#momstyle#whatiwore#marriage#marriedtoastarwarsfan#ootd#wifeliness#mamaswag#breastfeedingoutfit#ootn#chapterstyleenthusiast#blackonblack

0 notes

Text

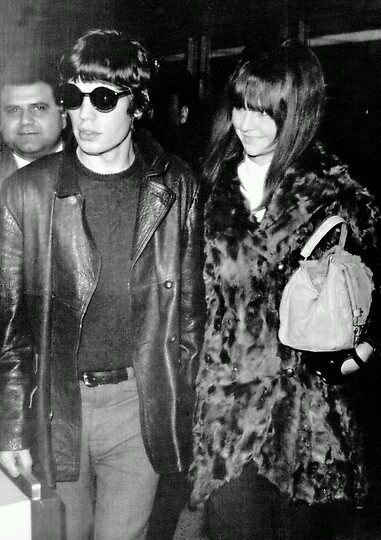

When Mick first met Chrissie, He was then 19 and a student at the London School of Economics, while Chrissie, 17, was a secretary in Covent Garden — in those days still the scene of a raucous fruit and veg market.

‘Mick would come and meet me for lunch,’ Chrissie recalls. ‘One day, as we walked through the market, a stall-holder threw a cabbage at his head and shouted “You ugly f*****”.’

Given all this, it’s perhaps not surprising that Mick hugely enjoyed showing off his beautiful ‘bird’ to his fellow LSE students, and she would later become the envy of his legions of fans. But life as his trophy girlfriend was far from the paradise they might have imagine

It was a fate which the young Chrissie can scarcely have envisaged when she first locked eyes with Mick Jagger at the Ricky-Tick, a blues club opposite Windsor Castle, in early 1963.

She occasionally collected glasses at the Ricky-Tick — one of the many small clubs the newly-formed Rolling Stones played as they began making their name in early 1963.

The night they met, Mick asked her out on a date. They had been seeing each other for about two weeks when the Stones’ fortunes suddenly began to improve with the appointment of their first manager, Andrew Loog Oldham.

‘As far as I was concerned, it was total love and I’d be with him for the rest of my life. I hated all the fan hysteria stuff, and I wasn’t that interested in running around the clubs and everything rock chicks are supposed to do. All I wanted was to have babies and be normal.’

At first, it seemed that her newly-famous lover shared her values.‘When I was first with Mick, I wasn’t allowed to look at anyone else or even be friends with girls he considered tarts,’ she says.Yet increasingly he seemed to regard any attractive young female who crossed his own path as fair game.

For her own peace of mind, Chrissie did not inquire too deeply into what went on out on the road. ‘I think I only knew he was unfaithful to me about three times, though there must have been many more times when I didn’t find out. And when I did, he would be so regretful.‘I remember him playing I’ve Been Loving You Too Long — the first time I’d heard that beautiful song, which I still find hard to listen to — after I’d found out about something. And I can remember him lying on the floor and crying all over my feet because I’d threatened to leave him.’

Despite such upsets, she and Mick were eventually engaged. No date was set for the wedding, but, in preparation, Mick’s mother, Eva, taught Chrissie to make pastry — for Eva, one of the first essentials of good-wifeliness — while Chrissie’s father, Ted, began looking for houses suitable for them once they were married.In June 1966, Mick made his own efforts in that direction, renting a fifth-floor flat in Harley House, an Edwardian mansion block near Regent’s Park. It was supposed to be their first home as newlyweds, but soon after finding the flat, he informed Chrissie that he no longer wanted to get married, just to live with her there.She paid a heavy price for agreeing to this new arrangement. Until then she’d managed to conceal from her parents the fact that she was spending most nights with Mick — keeping on, as a cover, a small bedsit in West London with a friend.The news that she would be openly ‘living in sin’ was so shaming a prospect for her father that he warned she would no longer be welcome at their family home if she went through with it.

That was at a party in London. While the other girls were wearing the new daringly short skirts of the day, Marianne arrived in blue jeans and a baggy shirt.

She caused a stir nonetheless. ‘It was like seeing the Virgin Mary with an amazing pair of t**s,’ says record promoter Tony Calder, who was there with Mick and Stones’ manager Andrew Oldham.

Around that time, Mick made various clumsy attempts at seduction — on one occasion trying to persuade her to sit on his lap in a taxi. But she dismissed him as a ‘cheeky little yob’ and went on to marry John Dunbar, with whom she had a son, Nicholas.

She had clearly changed her mind about Mick by the time of that Bristol concert. Her marriage was already over by then, and, after she and Mick slept together at his hotel after the show that night, he began visiting her secretly at her flat in London.

On December 15, Chrissie and Mick were supposed to be going on holiday, but there was no sign of him, and when she phoned his office she discovered that the flights had been cancelled. Even then, she still had no idea that he was seeing Marianne.

‘I remember thinking “He doesn’t want me, and I can’t live without him”.’Alone at the Harley House flat with her dog, six cats and three songbirds chirruping in the Victorian cage which Mick had bought for her 21st, Chrissie took an overdose of sleeping pills.

Only after Chrissie was released from the hospital, and recuperating at her parents’ home, did she learn from the newspapers about Mick and Marianne. And when at last she nerved herself to return to Harley House to collect her possessions, she found the flat’s front-door lock had been changed and she had to telephone the Stones’ office and make an appointment to be allowed in.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

I'm gonna SCREAM you and your WIFE look so gorgeous i mean THOSE DRESSES!!i m gonna cry i want a wife

WIFE - YESA LEGALLY BINDING WIFE-E-TUDE ! The magnificent-magnitude of my wifeliness is mind blowing !! Also thank you so much !! I’ll never tire of mentioning the creator of these gorgeous corsets, Retrofolie (Instagram) She’s AMAZING go check her out !I hope you someday have a wife !

12 notes

·

View notes

Quote

During the years in which I had come of age, American women had pioneered an entirely new kind of adulthood, one that was not kicked off by marriage, but by years and, in many cases, whole lives, lived on their own, outside matrimony. Those independent women were no longer aberrations, less stigmatized than ever before. Society had changed, permitting this revolution, but the revolution's beneficiaries were about to change the nation further: remapping the lifespan of women, redefining marriage and family, reimagining what wifeliness and motherhood entail, and, in short, altering the scope of possibility for over half the country's population.

Rebecca Traister, All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation (2016)

1 note

·

View note