Text

Love in the age of Facefuck: Iphigenia Baal’s Merced es Benz

Original unedited text; a poorly edited version appeared in Real Review issue 4, Summer 2017.

I guess I always was a little bit in love with Iphigenia Baal. I remember seeing glimpses of a whirlwind careening through parties, pubs, gigs, the backstages of shows with all of London’s seedy nightlife scrolling behind her as if the rolling backdrop of a private theatre, moving like a comet burning its own path through the heavens, a singular orbit governed by laws all its own and beware all those that fall within its thrall.

I recall a hazy cloud of curling hair, gap toothed, cheekbones, eyes that I now want to say were green, deepest hazel green flecked gems. Eyes that burned right through you, unforgivingly. Contemptuously. They had an intensity, a holding you to something, whatever it was. That’s what I remember most, a kind of smouldering raging intensity to truth — the kind that no one can really live with.

She was staff writer at Dazed at a time when, on the dole in a band and sleeping on friends couches or at the studio, I thought being on staff to write was just about the greatest job anyone could have. Somethings never change.

And she was simply beautiful. Beauty like in a Greek myth, with something timeless to it, otherworldly, at once raw and serene. All carried with such attitude, an always more hardcore than you kinda attitude. I guess I was struck. Intimidated.

From afar, a distance. I never really knew her, of course, friends of friends of an acquaintance, the occasional party, a couple of words here or there, nodded acknowledgement outside an opening, doorways, corridors, street-level passings by. Stories and rumours and gossips…I guess I was a little bit in love with the idea of Iphigenia Baal. I’m probably wrong about the eyes.

And so a decade later, in another life, Miss Baal’s second novel arrives in a package for me at the office sent by her publisher. Merced es Benz is a love story, a non-fiction novel charting the relationship between the author and one Ben Thomas — seemingly the love of her life.

Bookended by Baal’s own reflective prose, we’re witness to the relationship through a little over eight months of Facebook posts and chats, SMS, BBM, email, and google searches. It’s an exhaustive record of every digital exchange between them. From SMS setting up a date or time to meet, likes on each other’s posts or updates, arguments raging across different handsets, emails, sponsored posts, Merced Es’ google search results into drug networks, police informants, flights to Australia. A transcript of all the links and communiques between them logged in the system run out in chronological order. Objet trouvé. Print All.

It’s all text-speak dialogue, slanged abbreviations, the ping-pong chat messaging we’re conditioned to now. Bite-sized fluid snippets. Situated in the media that now frame our social exchanges, it feels utterly modern. And it reads quickly. Pages are scanned, scrolled rather than read. The layout echoes user interfaces — like the wireframes used to blueprint a webpage design. And yet it’s also antiquated, a rolling-back to an archaic version — Facefuck v1.3.2 circa 2011.

The drama is often in the details. You find yourself checking the timestamps of text exchanges, noting the gaps, the jumps, the ellipses. Merced Es traveling across London to meet Benz, only to be stood up, the messages repeating, ten minutes, twenty minutes, two hours no response, ‘where are you’s turning to anger then rage towards the other who only resurfaces the next morning. Everything feels real, and these are conversations, relationships, exchanges, acts of dickishness and inconsolable rejection that everyone can relate to, has been, played out. It’s London love baby, utterly relatable stories as old as the hills and bitched across spilling pints in pub corners across the capital forevermore.

As a teen, Baal was nicknamed ‘that Mercedes chic’ by her friends for wearing one of the iconic three-pointed-star-in-a-circle emblems snatched from the hood of a fancy MB motor around her neck. In Benz, she finds her completing half. Star-crossed lovers, a real-life Romeo and Juliette for the digital age. Merced es Benz has that touch of fate about it.

Love is a fiction, a story we weave, to entwine us together.

After opening with their first exchange online, Benz responding to a characteristically disdainful ‘Facefuck’ status update from Merced Es, the book jumps ahead to the immediate aftermath of Thomas’s untimely death from a drug overdose in July 2012.

Everything unfolds under the shadow of this tragedy — a death that perhaps if not accidental, if not a suicide, might awfully be wilful. Heartbreak even. A deep sadness pervades the reading of the couple’s exchanges. A constricting fatality born of the knowledge of what is to come. The whole book is a looking back, involving both a deciphering and an occlusion. You read searching for clues why, as well as vainly attempting to forget what you know so as to experience the couple’s shared moments in something approaching an authentic innocence. But death shadows, a constant companion inexorably pulling us back towards the curtain closed.

It’s a story of a doomed love told from the surviving half. A story of survival, of the telling required to ensure the other half lives on, can become full again once more. No longer simply that Mercedes chic.

There is of course the gap here between the author and her avatar or handle, between Ben Thomas and Benz. Merced Es both is and is not Baal. They elide, and this layering, merging, pulling away, leaving out, this différence, is dynamic.

In the same way, all the events and action of their relationship are absent. In between texts or emails we have to guess and imagine what transpired. Read between the lines, and project our own experiences into their exchanges, in order to make sense of the trace. A deciphering of what-must-have-to-have-happened to provoke this.

Thus as one looks for the source, for the reasons why, all we have are the traces of events that have always already happened elsewhere. Events that have been removed, isolated, quarantined. What we read is reductive — reduced to a trace that itself is raw, it’s copy itself, a copy of a copy, and we’re left with the bare bones. We see the outlines of rich media, image boxes with no filler, YouTube links vacant. Absentia in media res. Just like the object of love (Benz) himself.

Severed from both real life and the interconnecting digital web, the printed page is a mausoleum, but doubly here, triply even. Perhaps the only true archive or resting place of our online conversations is precisely offline — otherwise they are still live, active, full of potential to change, be rewritten, re-skinned.

I toy with the idea of looking up the video links on YouTube, copying the URLs out verbatim, for veracity, to establish the mood, to listen to the same track by The Rutts. But somehow that’s not the point. Memory, clouded and somewhat made up, filled in over the gaps, feels more authentic to this story.

Across the transposed Facebook group patter names are scratched out, effaced for anonymity but still recognisable, half legible, if you know what or who you’re looking for. Photographers, stylists, former colleagues from one magazine masthead to another, public house heroines and pinups. It’s a familiar world, that London of the turn of the decade.

Perhaps always in negative, Baal captures the nihilistic decadence of modern urban twenty-something living. Our protagonists are neurotic, directionless within a drifting affluence, never short of a party full of people they loath who are their best friends. Alienation for the trust-fund generation at the end of history. All this… and nowhere to go, nothing to do. Baal’s unforgiving cynicism and rejection of this scene shines through. The tawdry sub-gossip milieu of rich kids idling the world from party to party to beach to island to who cares where next with the touch of overly perfumed Louis XIV court intrigues in their drama and tousling themselves up with all the braggadocio of a rap promo. This centrifugal star-lit social scene is contrasted with hints of stunning dawn views from her 15th floor flat in a Bow housing estate tower block out in deepest East London.

But how much of all this is true I ask myself, is this real? I certainly remember seeing some of these posts on Baal’s Facebook, the letter that got her fired from Dazed, the ‘I fucked… and all I got was this petty vendetta’ t-shirt. Maybe one of those anonymous likes is mine.

Who was Ben? Did the author make him up? If not, what would his friends or family make of who you read about here? Did she write/ make all of this up?

Within a couple of quick searches Benz is revealed in the tabloid daily reports of his death. But even these always by a kind of second degree, headlines that the friend of so and so rock star kid it boy died. His death simply isn’t the story, isn’t the news, it’s his associates. Even here we miss him.

I think perhaps Merced es Benz is an attempt to reclaim part of this person lost. A way of saying it did happen, that for all of everything else he was/is/was this, at least to me. The idea and love of a person is surpassed on all sides by them, until that love is all we have left.

How much of this is a transcript? Untouched, unedited, unwritten? To read is to be invited in to be a witness, but of what? All the events here, everything that happens, happens elsewhere, IRL somewhere, off read, off piste, off script.

Merced es Benz is an account from the aftermath of a cataclysm. It’s the act of piecing together how we got here, a looking back and re-reading of archives. It’s the act of the bereft that Baal puts us as readers into, into her shoes.

It’s also the act of writing today. Through technology tracing our every move, thought, exchange, calorie burnt, website visited, link clicked, the great book of being is being written by machines in a language we can’t read. What we mean is our trace, the trail we leave behind through the systems we traverse. In this way the writer is effaced from the writing. Baal tries to take herself out of the equation, effacing herself, by instead reaching towards becoming a pure conduit to this trace of her past. It’s an act of carrying that trace forward — an act of not acting, of not writing but rather of reading — the writer in negative. In absentia.

But in this way we become her — recalling and returning to the aftermath, trying to make sense of the event(s) of our lives. This non-writing — this archaeology, this digging up — this is ours, perhaps all that we have ultimately.

There is a great vulnerability and honesty in Baal’s non-fiction novel. It pulls no punches, about anyone, least of all herself. If we’re sympathetic to her characters, they’re not faultless. We’re welcomed inside the expressions of their neuroses, doubts and rages to each other just as much as any love between them.

And here’s the thing, thinking back I wonder if there is really love in this story, in so far as it’s a story of a failed, doomed romantic encounter. Almost as if the love each of our protagonists held for the other, living outside the book, the traces of its expression and thus their ability to communicate it to each other, couldn’t navigate these mediums between them — perhaps it’s a warning about love being innately atrophied in the age of Facefuck. You’ll only find love in the real world.

Recently I’ve been seeing clips of scorpions and crabs shredding their shells recur on my social feed. There’s something strangely satisfying in watching the disconnecting, withdrawing and pulling away under the hard surface, the reveal of the soft vulnerable pink fresh skin exposed underneath and then the empty husk left behind. The hollow shape of the thing, there but without substance, without content.

I think of this husk in relation to Merced es Benz. There is bravery in letting oneself be so laid bare, opening out the vulnerability and shape of oneself. An affirmation to say a kind of, I once was this.

To be a writer is to share of yourself, invite others to step inside this externalised piece of you. You can only really write what you know, or write to unlearn yourself. Perhaps in reaching for an already externalised trace of herself at the intersections with another person, Baal finds something that enables an authentic intimate encounter with an other for a reader, a kind of genericity that everyone can reach towards.

Ultimately, I think Baal suggests that writing today is neither simply the digital trace nor using that trace as a medium of expression, but lies beyond, within a composition or choreography that primes the possibility for encounter. And against the comforting alienation of our self-reinforcing media bubbles, her book asks how one can encounter the other, perhaps even how can one love today?

Told almost entirely through social media posts and digital communications, about love and about death, Merced es Benz is an uncovering of the past and a trying to come to terms with it; it addressing the nature, and thus future, of writing itself as confronted with technology and the mediations of today; and, for the old Badiouian in me, it is about fidelity to an event, twice over, that of their love encounter, and that of his death; the one nested in the other, for only by faithfully expressing the truth of the first can one face that of the second.

I guess I’m still a little bit in love with Iphigenia Baal, but not in the way I was before. Now, perhaps on her terms, in the way that she invites us readers all into a love that is forever lost, to step into these moments, and feel and watch and recall through the moments of our own lives, what it is to know, to love someone — if not the writer then perhaps her Benz.

Merced Es Benz by Iphgenia Baal is published by Book Works as part of the Semina series guest edited by Stewart Home. Order a copy here.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writing After the End of Writing: An Interview with Tom McCarthy

Shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker Prize, author Tom McCarthy’s latest novel Satin Island is that rare occurrence of a book that feels both eerily prescient and utterly contemporary. Near East Contributing Editor William Alderwick recounts a personal exchange with the writer and text that takes in the Venice Biennale, new video streaming apps and parachutes let loose to the winds.

Text by William Alderwick

Photos by James Pearson-Howes

“W., Is that you?” he asked, peering over dipped shades in the garden of Palazzetto Bru Zane in San Polo, Venice. Wearing a trim, dark linen suit, standard issue sunglasses, and hair tightly cropped, the author had just completed a reading of his latest novel in one of the upstairs halls. Pinching the neck of a champagne flute in one hand, his eyes darted once, searching for an answer. As we loitered momentarily in between the celebrated curator and magazine editor with whom he had just shared a stage, it struck me that there had always been something of the secret agent about Tom McCarthy.

I was in Venice for the biennale. Arriving a few days before the press circus kicked into gear and staying in St Elena at the southeastern tip of the islands, offered a calm sleepy neighbourhood, quiet like a mountain village, vacant of tourists and the bustling hustles of the alleys and canals. Each morning, after sipping uno espresso at the counter of a local bar, I would sit on one of Cafe Paradiso's little tables outside the entrance to the Giardini watching the water buses off-load their passengers, gazing out over the waters from the bank of the lagoon, reading my former supervisor’s new novel.

McCarthy’s Satin Island is the story of U., a corporate anthropologist working for the Company, a nameless agency dealing in ‘narratives'. U.’s work involves providing strategic advice for brands like Levi Strauss jeans, often by taking avant-garde leftist theory (Lévi-Strauss, Deleuze) and plugging it back into the capitalist machine. Beyond this, U.’s charismatic boss Peyman (a kind of bloated cross between Rem Koolhaus and William Gibson’s Hubertus Bigend) charges him with writing the 'Great Report' — a definitive account of the contemporary, as part of a much larger invisible project that will apparently 'change everything'. Heroic, modernist stuff for sure. Except that without a set brief to work towards, U. never gets round to writing the great report itself. With a subject as ubiquitous as 'the now', U.’s ongoing research covers everything and nothing. He compiles scrappy dossiers of illegible notes into topics as varied as oil spills, parachute deaths, south pacific cargo cults and buffering. But, like a Thomas Barnhard novel, we never get to read this Platonic great report. Instead, Satin Island is filled with everything else, with U.’s account of not-writing it and by the detritus thrown off by that process.

It is easy to identify with a character called U., every sentence can feel like it is personally directed. Indeed, McCarthy’s Kafkaian protagonist is a modern day everyman. Almost everyone I know who has read the book identifies strongly with him. “U. could be me,” is a common reply, “that’s my job he’s describing!” I remember thinking that, perhaps McCarthy’s compromised corporate anthropologist has captured something, a pervading feeling of futility: a sense that no matter how well educated and informed and inspired and passionate we are about our causes, the magnum opus we each work towards today is always already out of reach. The thought carried me to the idea that most architects failing to break through to professionally are probably condemned to working on the mundane, traffic islands or stop signals even. It carried me to Roarke-ish individualists crafting detailed plans and blueprints for unrealizable projects, great arching mausoleums like the French C18th visionary Boullée. That perhaps we’re all collectively carving out grand cenotaphs never to be built. Sat soaking in the mid-morning sun, by the lagoon, buzzing under a riddle of caffeine shots, Satin Island felt like a book about the contemporary, somehow uniquely capturing the modern condition. What subjectivity is today. What it all means.

The vaporettos spit out more art world insiders, faces and names, steely associate directors and flamboyant Latin collectors. A large poster on the terminal billows lightly in the breeze kicking up off the waters. All The World’s Futures — the title and theme the biennale writ in large bright red lettering. It is a Baroque curatorial approach, taking a single theme split into three strands, with yet more sub-threads dangling loosely beneath them, that ultimately fails to provide a frame of reference. With it impossible to place more than a handful of artworks successfully in this semantic architecture, the Biennale comes across like a grand menagerie of unique pieces, objects and words shorn of all context to sit lost and adrift.

The challenge with the world’s largest group show, of course, is both its scale and that of its audience. The biennale is implicitly about making an artistic statement to the world. But, this begs the question of how effective communication with the global multitudes, across cultures, across generations, across languages, is even possible?

Fittingly, the logo for U’s Company in Satin Island is a giant, crumbling tower. Babel. Channeling Koolhaus, the part-Persian Peyman claims the myth has been misunderstood. Rather than a symbol of man’s hubris, the attempt to reach the heavens through the tower and speak the language of God only matters in its failure. The collapse that scatters the tower’s would-be occupants horizontally across the earth, babbling away in different tongues, actually becomes "the precondition for all subsequent exchange, all cultural activity”. That the jagged ruins and rusty scaffolding remain derelict and useless is actually what is most valuable about them. This uselessness sets the ruins to work as a spur to the imagination and productiveness. And thus, any strategy of cultural production must first liberate things into uselessness. Perhaps then, I wondered, are the biennale’s failures deliberate and liberating, like being gifted a handful of jigsaw pieces without a puzzle?

I only hear about McCarthy's talk in Venice a day beforehand, in a moment of deliberately distracted and self-induced boredom scanning the events listings on Facebook for other things going on. #FOMO. In the bright early morning I rode the vaporetto back up the grand canal, into the heart of the city of light. Watching gondoliers set up their boats and the crooked shadow of an old woman, almost bent double by the weight of her black shawl, stand palm out, upward facing, begging for alms in a lonely corner, I sat for an hour in a local square, burning through the final few chapters of the novel's climax.

During the reading, McCarthy's voice rang out like on the tannoy at a local train station. Each word was carefully enunciated, revealing new alliterations, subtle rhymes and unconscious resonances that had be lost in my own reading of the text. Like a Sartrean waiter, he was almost playing, playing at the precision and care in delivery of public service announcements, playing so that all meaning and mis-meaning might linger out in the air between us all like forgotten children left behind on an evacuated platform.

Stepping outside into the mid-morning sun, shuffling through the pleasantries of another reception and sipping sparkling water, I nod.

“Yes T., it’s me. W.”

A couple of months later, we’re speaking over a Skype video call. As we talk the image stutters in that familiar way, colours decaying and refracting at the edges as variable bandwidths compress our data and digitally tinge our voices into echoes of the singing tone poems of dial-up modems. Thinking back, I ask myself what a literary double-o agent would actually be? An author who was using language to subvert or re-engineer culture and society? Through the low level network noise, an encryption of sorts tracing the wires, subroutines and pathways our exchange takes in the network of communication servers linking us, I ask T. about the connection between agents and writers. Are writers in some sense ‘secret agents’?

“Burroughs’ idea of the writer is that he’s some kind of agent,” affirms McCarthy in response. “He’s either called into action by a command elsewhere within a network of other agents or he himself activates these agents through his symbolic interventions. His media hack activates a whole other network of sleepers; he turns people into agents.”

“There’s a line that Burroughs and Brion Gysin sampled a lot, 'Calling all active agents, recalling all agents, calling all reactive agents', and all these permutations. This seems to really sum up the way he sees what it is to write. With Burroughs you’re being called by the underground into active acts of sabotage.”

Or almost infected perhaps? I offer.

“Yes, this whole viral structure of language and writing is something that appeals to me very much. In Satin Island I play with both sides of what it would mean to be an agent. My hero at one point has these very Burroughsian fantasies of sabotaging everything, using his insider status as a corporate anthropologist to put badass data into the system. But at the same time he’s very aware that he’s also an agent of power. He’s feeding his anthropological skill, all of which comes politically speaking from the left, back into the neoliberal machine. He’s a kind of double agent who harbours fantasies of becoming a triple agent, but then what if that just means you’re a quadruple agent and so on? So the whole idea of agency is very dissipated.”

As well as his writings, McCarthy has acted as General Secretary of the International Necronautical Society for over 15 years. The INS is a kind of fictive avant-garde revivalist group playing on the bureaucratic trappings of international bodies to explore and navigate the 'space of death'. One of the group’s early actions involved turning London’s Institute of Contemporary Art into an analogue radio broadcast station. Reenacting the broadcasts out of Hades in Cocteau’s Orphée, McCarthy and his team used Burroughs and Gysin’s cut-up techniques to create fragments and random splices of text from newspaper articles. These found poems were read out on air as little lyrical ‘earworms’, hacked media voiced as calls to action.

If McCarthy has always been an agent of sorts, in person he can come across with an almost clandestine, guarded air. It’s not out of a sense that he is hiding anything, but on the contrary the feeling that McCarthy is about to reveal something. Reveal that there are secrets, even if they never quite breach the surface… like an ongoing unsheathing of a truth that could never quite be exposed. It is as if he is always on the cusp of an interrogation, eyes glinting brightly like a shrink who has sniffed out the faint scent of a breakthrough in the case.

My first encounter with T. was when he taught a course as part of my postgraduate studies. Active with the INS, with his first novel Remainder critically praised and other books being published with some regularity, he must have been writing his previous novel, C, at about this time. Also shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, in 2010, C follows the short life of Serge Carrefax through the emergence of the early C20th's electro-modernity to explore ideas of transmission, death and mourning. Taking in similar themes, McCarthy’s course centered around reading Abraham and Török’s psychoanalytic studies of Freud’s famous ‘wolf man’ case. Their approach took the form of a ‘cryptonymy’: exploring anagrams, homophones, rhymes, puns and other word and sound plays as expressions of unconscious desires that circumvent the mind’s linguistic censorship. In other words, that a patient’s dreams can be decoded to reconstruct and expose a core, hidden truth or primal scene locked within a crypt deep within the psyche, and otherwise inexpressible to the conscious mind.

“In my last novel, C, that Abraham and Török book was a huge influence,” offers McCarthy when asked if these ideas carried over into his latest work. “[C] revolves quite literally around crypts, family crypts, encryption and encrypted signals. It’s about the crypt of early late modernity, of the early 20th century. By Satin Island, which is set about 100 years on I guess, that has become a kind of digital crypt, the black box of the mysterious servers that basically organise every moment of our existence—including this one we’re having right now.”

Static crackles echo faintly in the Skype hinterlands behind T.’s voice.

“We are dwelling right now inside some black box in a Nevada desert and another somewhere in Finland and a black satellite up in the sky with some black box in Maryland doubtless listening in. Not even human black boxes, just crypts decrypting and re-encrypting each other.”

Non-human agents, I offer.

“Yeah, the whole human agency is pushed out to the side—it’s data reading data. Humans are implicated in that but we’re not the center of it. We’re not the generators of it. We’re just kind of little flies in that mash, or affects of the network somehow.”

Is there a continuity between these two character, Satin Island’s protagonist U. and C’s hero Serge, I ask? Both characters experience similar kinds of emergent technologies that are transforming what connectivity, communication and mediation itself are, but perhaps responding to them with different postures.

“It was funny to see the way C played out in the mainstream media. They saw it as a historical novel, but for me it wasn’t really at all. It was about new media, it was about empire, but it was an archaeology of the present moment. It had very contemporary concerns but it was a Foucauldian archeology of where we’re at now. With Satin Island it really is set now, it’s about now and it’s set now.”

“At the same time, [Satin Island]’s through-running premise is that the present is impossible; ‘now’ is an impossible kind of ontological situation, or an epistemological one. You can’t talk about now, there is no such thing as now, as the contemporary. So it’s a novel about the contemporary without a contemporary.”

* * *

I fall back into the moment. A vibration in my pocket pulls me out of my thoughts. Glancing at the locked screen of my phone a notification pop-up from a new app I’ve recently downloaded. Periscope. Live shareable video streaming. Hans Ulrich Obrist is live. The Age of Earthquakes with Douglas Coupland. The extreme present. Watch. Now. Live. Sleepily I thumb-print myself into the stream.

Coupland is speaking, mid-sentence, answering a question from the sounds of it. I try to figure out what it might have been. He stands against a clean white wall. You can tell he’s standing by the way his weight shifts slightly from left to right, the way he leans a little against the wall, though really you can only see him from the solar plexus up. The Generation X author, original zeitgeist-y spokesman, is being loosely interviewed from off camera.

Behind the screen, presumably from a point equidistant to his own phone filming the scene as to where I am sitting holding mine watching it, comes the voice of Han Ulrich. They’re plugging their new book, The Age of Earthquakes. They’re talking about now. How the internet and digital technologies have sped up time. Our experience of time has changed. We now live in the extreme present, a moment caught in continual acceleration, ever faster, ever onwards — it sounds like falling upwards on the far side of some informational asymptote. Watching, I get a faint feeling, like a recollection, the afterglow of a vertiginous overload of information. It’s as if they’re grasping at something profound, if not quite ever reaching it. Heraclitus once, famously, said that you can’t enter the same stream twice. I tap out to see what’s happening on Instagram.

Maybe a fortnight later, I’m back on the call, watching T. on another screen, another stream, this one live from his living room. He’s talking about how he’s collaborated with Hans Ulrich a lot and thinks he’s a wonderful cultural presence. The Serpentine Gallery director being a driver of a lot of what’s happening in the cultural landscape. How T. and Coupland did a public dialogue in Toronto a few years back, but they have quite different positions on all this.

“Douglas is always talking about the future as though it were this fixed thing, and I’m suspicious of that,” he counters when asked about the ‘extreme present’. “I’m suspicious of an overall narrative where the future is inevitable, which is usually a narrative that capitalism is an inevitability to which the future belongs. Also, I’m suspicious of this linear idea of acceleration into the future. Hasn’t modernism given us different temporalities? Joyce and Beckett have given us gyres and loops and simultaneity. Benjamin argued for this notion of the angel of history always looking backwards."

With these new temporalities, I ask, should we be trying to develop new languages or new dispositions towards time? If the language that we use and the politics that we have is structured in such a way as to provide us with grand linear narratives, of progress and capitalism even, perhaps we should be trying to find ways to increase our literacy in different ways of living in time?

“Yeah, I think a backward facing politics would be really interesting,” responds McCarthy. “It’s what’s so interesting about punk. Every other political movement is about saying, ‘In the future… a better future…’. Punk just goes, ‘Screw that. No Future.’ Mallarmé was another big influence on Satin Island. He has these weird temporal models where a present doesn’t exist. There’s just this gap with past and future colliding, all strung around an event that he cannot name, that cannot be named. Alain Badiou gets his whole idea of ‘the event’ from Mallarmé, the event as the thing that makes thinking the event impossible, that vandalises its own possibility of being thought. My temporal model would be this out-of-jointness, this multiple slippage and in the middle of that, it would be pregnant with the possibility of an event."

Where did the idea of using the anthropologist as a model for the writer today come from?

“When I started this book U. was going to be a writer who’d written a mildly successful novel and then got picked up by the brilliant Peyman, founder of The Company, this super-zeitgeisty consultancy that has philosophers and urban theorists and film-makers and mathematicians working for it, and instructed to write a kind of literary report on the present moment. [But] I just really didn't want to write a book about a writer trying to write a book because there’s quite a lot of those all written by white men and I just felt that the world does not need another one."

“Then I thought, the anthropologist is an interesting figure because he’s a writer, who looks at the world and who write reports on it. Then I came across the figure of the corporate anthropologist, who’s just brilliant. He’s the perfect figure for our age. This collapse of any exteriority, any sense that you’re looking at things from the outside. You’re right in it, you’re in the heart of the machine, you’re totally compromised; and this was very attractive to me as a position to articulate and to map this whole situation from."

“I’ve done readings where the bit about U. feeding Deleuze back to jeans manufacturers [has] people roaring with laughter. I have to stop and say, ‘guys, this is no satire, this is true, this is totally true.’ This is what corporate anthropologists do.”

You can tell who works for the corporation, they’re the one’s laughing and crying, I offer, somewhat guiltily.

“Exactly. It just seemed so perfect to use a corporate anthropologist, like an anthropologist after the end of anthropology, as a kind of stand-in for the writer after the end of writing."

So if all the great writers, artists, thinkers or visionaries of today are now working for the Company like U., they’re at Google or have their own start-ups, what is the future of what might once have been called the avant-garde?

“I think writing is in an incredibly dynamic mode now, now more so than ever. But, paradoxically, only because it’s facing up to its own kind of death and its own impossibility. Writing for me is always most interesting when it’s in that incredibly threatened and challenged state. The same with painting. Painting only really becomes interesting when it’s made redundant by photography, that’s when you get Gerhard Richter and Andy Warhol. The really, really interesting stuff happens after the seismic traumatic apocalypse. And I think writing’s in that state."

“While I was writing this book, the whole Edward Snowden story was breaking. This is really interesting because it places questions of reading and writing right at the heart of political and of personal experience. Politics has become a question of reading and writing: who gets to read what, of legibility and encryption and illegibility. So writing is definitely a completely central cultural mode for me. At the same time, I think mainstream middle-brow fiction is not really engaging with this situation, or with these possibilities.”

“What’s interesting about more recent media is that they acknowledge and celebrate distraction and interference as central to the whole aesthetic experience. This is what writing should be doing."

Lamplight skipped scattered arpeggios across the silken black surface of the lagoon. Walking back along Venice's long waterfront through the silent night, I think back to the biennale’s title. All the World’s Futures. It suggests that this one moment, one point in time, was the fulcrum and axis about which all else turned. It names this moment. That from now, everything is defined, chosen, limited, excised, forgiven, forgotten, born and lost, as if to pass away into a dream. It’s a conceit and a truism of course — all potential and possibility lies hollowingly within the actual. This moment could be any other. It is every other. But to name it, focus it, draw our collective attention down and together — if but for the sheer popularity and visibility of the biennale itself — perhaps makes of it something? Even if but for a choice, a call for a choice, for action.

Another of Peyman’s riffs in Satin Island is about knowledge: that the last individual enjoying a full command of the intellectual activity of their day, was Leibniz. The C17th polymath was on top of it all, physics, chemistry, geology, philosophy, maths, engineering, medicine, theology, aesthetics, politics. But since then the disciplines have scattered like the would be residents of Babel. “Each in its own stall, shut off from all the others.” A Leibniz 2.0 is now impossible; no single human intellect is capable of unifying this diaspora across the fields of knowledge. Instead, Peyman see continual migration and mutation. Each discipline surpassing itself and breaking its own boundaries, merging with each other into new fantastical mirages upon impossible topologies in the interstitial zones between what can be known.

Reading a newspaper, U.’s attention gets caught by the story of a parachutist who died when his chute failed on a jump. The death is being treated as a murder case and U. becomes obsessed. Consumed, he devours all the details, researches other examples and similar cases, concocts elaborate whodunits and proofs of dark suicide cult conspiracies. Rather than the fate of the man, the most striking image comes when McCarthy writes of the parachute let slip of its charge, billowing freely in the skies above as the jumper plummets in terror to be dashed on the ground below.

8.1 And all this time, behind these apparitions, another one: the image of a severed parachute that floated, like some jellyfish or octopus, through the polluted waters of my mind: the domed canopy above, the floppy strings casually twinning their way downwards from this like blithe tentacles, free ends waving in the breeze… This sense of calm, of languidness, grows all the more pronounced when set against the pain of the man hurtling away from it below. He would have looked up, naturally, and seen the chute lolling unburdened and indifferent above him—as though freed from the dense load of all its troubles, that conglomeration of anxiety and nerves that he, and the human form in general, represented.

— Satin Island

This air-born jellyfish took me back to Benjamin's angel of history, forever facing the past with its wings caught in the winds roaring out of creation and its back forever to the future.

As time and information swells and roars around us, as our comprehension of the present moment shrinks in focus and the sum total of knowledge surpasses the capabilities of the knower, are we now not left behind as lost to the world and doomed as the falling jumper? Already dead, in some kind of half-life free-fall, like Wile E. Coyote hanging air time above the chasm. An angel shorn of its wings, cast out of history as residual and collateral to the surge and roars of the great storm of the world. Exit stage left.

Back in the small garden, on a patchwork of little islands clustered in the waters of the Adriatic, I ask T. if this is what the jellyfish represents. With our technologies now increasingly autonomous, are we no longer the protagonists in the story of the world? Is this the moment U. writes about, in negative, in his reports? Writes without writing?

McCarthy smiles. Behind the shades, I wonder if there’s that knowing glint.

The deferred climax of Satin Island sees U.’s girlfriend Madison recount her experience as a protestor at anti-capitalist riots in Genoa. Brutally herded up by militarized police corps, shuttled to a school gymnasium and beaten, Madison is then taken alone to a remote Alpine villa. In a decidedly Lynchian setting, Madison is made to perform an algorithmic sequence of bizarre nonsensical yoga-esque poses by a portly suit-wearing Euro-crat executive waving a cattle-prod, like some erotically bankrupt future sex act.

The episode sits in the book as both a promise of meaning and its renunciation at the same time. Fundamentally meaningless, or rather beyond meaning, laden with a profound, inscrutable and indecipherable truth that goes beyond its telling, it is the point the text comes closest to revealing everything but…

“[It reveals] nothing."

Exactly.

“I was thinking of Lynch a lot and particularly of how in Lynch, when you get all the way in, through that kind of labyrinth, you get to the inner chamber and there’s a control room. He always has a walkie-talkie or an intercom or CCTV going somewhere else. I think he gets that directly from Kafka. You get this always in Kafka, the room is never the room because it’s always just the antechamber to another room which is actually on a telephone to another room and even if you got to that other room that would just be the kind of back-up room.”

“Madison gets to the very heart of power, thinks it’s a place, and then discovers it’s a network. It’s just always a network, it’s never here. In the same way as U. notes that, in bed, she can’t come unless she’s thinking of someone else, power seems to operate the same way."

“It’s about a staging of power, and a staging of power as a kind of perverse form of theatre. A theatre of repetition and simulation, of aesthetics done in an incredibly violent and exploitative way."

I wonder about the ever increasing processing power of technology and networks. What happens to us if we lose our seat as the writers of history, cede sovereignty to some future-born A.I. and fall in line behind the Singularity?

“The whole Singularian thing seems rather Christian, frankly, it’s very teleological. One journalist called it ‘the rapture of the nerds’—it’s a good way of summing it up. In Satin Island, U. is meant to be writing the book, the über-book, the Great Report, and at one point he thinks that it’s impossible to write it. Then he has an even more horrific thought, which is that it’s already been written, but by software. Our networks of kinship are being mapped. Every time we go on Amazon, Facebook or just walk down the street it’s being written [down] by software and it’s only legible by software."

"So at the same time U. is writing he’s slipping sideways. It’s kind of useless. The ultimately meaning is always eluding him. But at the same time there is this text produced, a set of agitations and connections that he is an agent in making, and I think they’re significant. He’s like Theseus, wandering blindly around a labyrinth but he has this ball of string, and he is mapping it."

“As I said to Nicolas [Bourriaud] when we did our dialogue in Venice, the distinction isn’t between the human and the machine, but between the master script and the re-write. To come back to Burroughs, to Operation Re-write. The master script has already been written, the techno-corporate system is writing that. It’s always been written since the beginning, but the writer’s role isn’t really to write that, it’s to somehow get into that labyrinth and start unpicking and deterritorialising and recombining. That’s a machinic procedure in a way, a technology, but it’s an important one and one I’d see as being the technology of writing, of being a writer."

Sometime after this. On the call. I forget exactly when as I’ve played the recording backwards and forwards too many times. It’s all cut ups of transcript and shuffled moments now. I ask about the INS, and whether the group is still active?

“Yeah, it’s a sleeper, an eternal sleeper,” T. replies. “Every so often we can do something and then maybe for eight months we won’t really do anything, but hopefully it’s still doing something even when we’re not doing anything."

Actively inactive as it were.

“Actively inactive. Yeah, just waiting to be recalled."

www.jamespearsonhowes.com

#tom mccarthy#satin island#c#remainder#international necronautical society#ins#writing#walter benjamin#william s burroughs#hans ulrich obrist#douglas coupland#booker prize#near east#james pearson howes#venice biennale#art

0 notes

Text

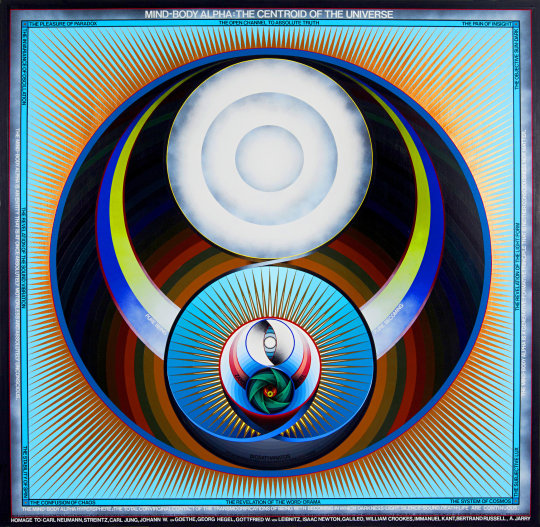

Beyond the Kitsch Barrier: An Exploration of the Bauhauroque. [On Paul Laffoley]

From Under/current magazine 01 Dynasty September 2008.

Encountering US artist Paul Laffoley for the first time at a Disinformation conference in upstate New York back in 2004 has left an indelible mark on me ever since. Somewhere between Buddha and Back to The Future’s Doc Brown, Laffoley gave a slide show of his works, lecturing with a lion’s paw in place of his left foot on his various theoretical subjects encompassing alternative histories, blue-prints for future human development, Goethe’s Ur-plant re-articulated into genetically engineered living architecture and his design for a working time machine. As collector Norman Dolph puts it in his foreword to Laffoley’s book ‘The Phenomenolgy of Revelation’, Laffoley could be the ‘spokespainter of a con- sciousness yet unborn’.

The problem is that the ideas presented in Laffoley’s science fiction visions are so far removed from established reality that by definition they’re insane. His mandalic architectural blueprints of metaphysical ideas regularly pays homage to and draw on such a diverse range of intellectual ingredients that no one person can possibly be capable of properly evaluating it all: Plato, Goethe, Schopenhaur, Madame Blavatsky, P.D. Ouspensky, Nikola Tesla, H.G Wells, Claude Bragdon, R. Buckminster-Fuller and Teilard de Chardin, to name a very small and under-representative selection. Much of Laffoley’s lack of attention within the mainstream art industry can be put down to this. As Disinformation host Richard Metzger muses, Laffoley’s ‘singular erudition’ and transdisciplinary auto-didacticism, almost entirely self-taught and thus free of academic compartmentalization and categorization, is so over most people’s heads that he’s misunderstood to the point of tragicomedy.

Despite this pervading incomprehensibility, Laffoley’s credentials are kookishly ivy-league impeccable. Educated in Classics and Art History at Brown, he went on to study under the authentic Modernists then teaching at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where he was dismissed for ‘conceptual deviancy’ — for proposing a living architecture of grafted and cultivated vegetable chimera as the only logical solution to the issue of low cost housing. He went on to work in the design group for the World Trade Centre at Emery Roth & Sons before apprenticing with visionary architect Fredrick Kiesler and Andy Warhol. His first solo show, in New York City, resulted in the gallery owner appropriating all Laffoley’s works and transposing them to a pot-smoked and hay strewn tent at the Woodstock festival, leaving Laffoley to commandeer a van and drive endlessly round the festival attempting to liberate them. Forming the one-man think-tank Boston Visionary Cell in 1971, Laffoley has dedicated his life to the practice of his singular form of art and philosophy, participating in over two hundred exhibitions both national and international.

Whilst staying at Warhol’s pre-Factory studio on Lexington Avenue in Harlem, an enormous abandoned fire station conversion, Laffoley was tasked with watching a wall of televisions running night and day like in the Bowie film The Man Who Fell to Earth. As the new guy he got the worst spots, from two in the morning until dawn. All that was broadcast at that time in those days was a series of test patterns. Laffoley thought these test patterns “looked pretty much like Tibetan mandalas” and compared them to Warhol’s own screen print multiples as in the Campbell’s Soup Cans: “once you set up diagonals, circles, put in multiple images you have Tanka or Tibetan religious paintings”. Warhol completely rejected this connection between religious metaphysical imagery and post-modern representations of our iterated cultural landscape in relation to his own work, but this offers us an essential clue in attempting to understand what Laffoley’s work could mean for us today. Laffoley’s gallerist, Douglas Walla of Kent Gallery, New York, uses the metaphor of operating systems to describe his work. Whilst Laffoley’s near autistic totalizing world view could be misunderstood as outsider art, Walla contends that it is actually the very pinnacle of conceptual art. The constantly running televisions enabled Warhol to see what was filling the mass overmind – the contents of the zeitgeist’s self-image – which he could then take as the contents for his own Pop Art. The test patterns however concerned not the contents but the structure of this collective self-presentation via television; they were used to tune your set to pick up the broadcast image. Laffoley’s ‘operating systems’ could be thought of in the same way, as test images for attuning our mental software to a new frequency.

This notion of existential software or metaphysical cartography is perhaps most apparent in works such as Dimensionality or The Parturient Blessed Morality of Physiological Dimensionality where Laffoley proposes a theory of dimensionality at once divergent from not only our immediate experience and mundane ideas but also ground-breaking scientific research. Laffoley’s rejects the multi-dimensional String Theory of physicists such as Brian Greene or Lisa Randal as “like looking through a gigantic cosmic filing system”. For Laffoley scientific theories of dimensionality fail to get “a sense of what its like to be alive in there”, and fail to think temporality fully – in terms of possibility, manifestation and types of energy – and hence get stuck with the single catch-all word ‘time’. Laffoley illustrates ‘Hyparxis’, the sixth dimension, through the role that anticipation plays in conversation. Anticipating the meaning that the other person is attempting to communicate to you determines their actuality, which of the possible manifestations or courses of the conversation become real; “completing possible manifestations for another person… you recognize you are both on the same page as the cliché goes”. Hyparxis or “the completion of being” involves the actualization of every possibility, or an infinite number of compresent universes all on top of each other and collectively manifesting every configuration of being possible. An essential aspect to Laffoley’s project is the challenge that these higher-dimensions pose and whether we can coherently think about them. As Laffoley points out, the consciousness living within this realm would be as different from us as our own is to that of an amoeba doing the back-stroke in a Petri dish. As the example of our limited conceptualization of temporality shows for Laffoley, “we have no nomenclature, I am trying to build a nomenclature to describe this because it explores possibilities and manifestations”. In effect, Laffoley’s work offers us potential cartographies of reality and the logics underpinning it on a far vaster scale than anything else we’re used to; a change of perspective capable of changing we way we live.

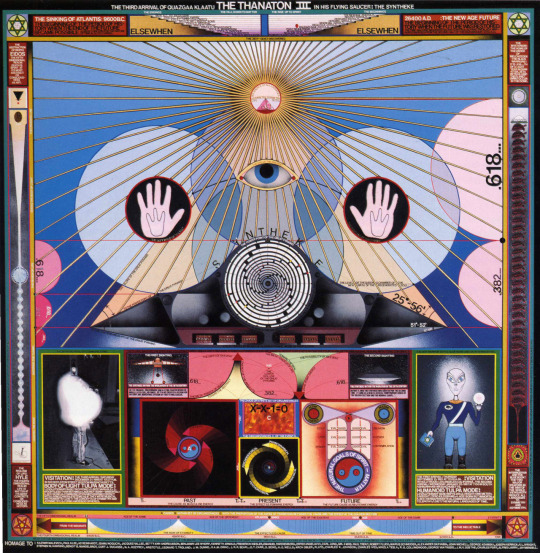

Perhaps Laffoley’s most famous painting is Thanaton III. In contrast to most of his other work, blueprints for unmade devices or metaphysical cartographies, Thanaton III is the machine itself. Laffoley describes it as a psycho-tronic device, meaning that the very structure and composition of the image utilizes the activity of looking at it on the part of the viewer to impart knowledge to them. In order to understand this we need to turn to Laffoley’s theory of the epistemic ladder. Briefly, Laffoley sees a hierarchy in the mutually interdependent relation between the subject and object of knowledge in terms of which is active and which is passive. On the lowest rung of the ladder, that of the sign, “the knower is in control and that which is known is completely controlled”; the knower is active in relation to a completely passive object. As we move up the rungs the relationship balances out and then inverts, until we get to the symbol where “the knower is passive and the knowledge is active, you reach a point where a single occasion of knowing could not be willfully released by you. In the true symbol, the environment has nothing to do with it at all. The knowledge is intransigent. You’re in rapture and you have to be pulled out of the epistemic structure by an environmental entity. That’s the way you could describe the knowingness of a mystical experience”.

Thanaton III invokes this symbolic potency through a deceptively simple optical technique. Standing about an inch away from painting with your hands touching it on the pads, you stare into the eye embedded into the great pyramid. That close to the canvas your eyes cross. Unable to sustain this, they defocus and wander outwards before refocusing back onto the black sphere in front of you. Each time your eyes de- then re-focus they effectively and unconsciously suck in more and more of the information coded both geometrically and textually into the surrounding imagery. After a while you stop seeing the image before you at all and start what could be called daydreaming. However, it’s a ‘daydream’ encoded and structured by Laffoley; the viewer is passively consuming the informational matrix actively provided by the image. Laffoley likens this to medieval illumination: “where you look at something that bypasses your conscious critical powers, and you have to absorb the ideas”. For Laffoley this image ‘downloads’ the information into the viewer through by-passing their standard routes of cognitive consumption and digestion.

Laffoley’s short-circuiting of disciplines and theories means that it’s almost impossible to think of his work in terms of the standard discourses and narratives of art history. His own typically divergent view of art history centres on the three phases of modernism: Heroic Modernism proper, post-modernism, and what he calls the ‘Bauhauroque’. For Laffoley, post-modernism began with the demolition of the Igoe-Pruitt housing project in 1972. The multi-award winning project crystallized modernist utopic visions in its attempt to solve the housing crisis but “exploded in their faces because no one could stay there”. Its demolition in turn crystallized the inherent flaws and failures of the modernist project itself. The Bauhauroque, “combining the heroic Modernism of the German Bauhaus, with its aspiration towards technical Utopia, and the exalted theatricality of the Italian Baroque, in which an exuberance of form and illusion serve to express the mystical union of art and life”, in turn was inaugurated by the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the demolition of the twin towers. Whilst Heroic Modernism penetrated the sublime barrier characterizing Romanticism – incorporating the sublimity of confrontation with the absolute and the phenomenology of eternity into consciousness – we now face the kitsch barrier and the connected aesthetic of zombies, or the relation of thought to the undead. Loose comparisons could be made with Slavoj Žižek's engagements with the psychoanalytic undead of the lamella; or the immortality of the subject to an eternal truth for Alain Badiou. Through post-modernism, for Laffoley, the kitsch took over and became ubiquitous. The Bauhauroque and “zombie aesthetics [are] the attempt to penetrate the kitsch barrier. Kitsch is the visual equivalent of a zombie, because it is a reanimated form of life, like losing your soul and then repossessing your body with the same soul. You have to get past that and you have to recognize what it is that you are getting past, because otherwise you end up just repeating yourself, like people who don’t understand history are doomed to repeat it”.

Laffoley gives examples of cultural figures who seem to lack the ingredient of consciousness, behaving like un-conscious automatons – such as Elvis in the year before his death, the current state of Michael Jackson or ‘the culturally ubiquitous Andy Warhol for his whole life’ – to explain how zombie aesthetics operates: they “exaggerate positions so that people can observe that in a way that’s never been done before and that opens up possibilities for people. The function that people who indulge in zombie aesthetics perform is that they give you an inoculation, like getting inoculated with a dead virus because these people are working with death themselves. Like recognizing there is a portal to something new, they are creative road signs to the future”. Laffoley likens this inoculation to the effect that Jules Verne’s Man on the Moon had in relation to the Apollo landings. Verne got the sensibility of going to the moon so spot on that when it actually happened the actual surprise had been muted to the point that some people believed it wasn’t real: “the shock of the new was over”. That Laffoley can easily be equated with outsider art comes from the kitsch nature of his images: “all outsider art is pure kitsch, done without any satiric content and just living in it completely. That is what in essence ends with the Bauhauroque”.

The ‘operation’ of Thanaton III – a touchstone for Laffoley’s entire body of work and a distillation of his theories – could thus be seen as purporting to put one into the state of a zombie, rendered totally passive by the inversion of the epistemic relation between the knower and that which is known, and hence penetrating the kitsch barrier. Interestingly Laffoley suggest that the same symptoms can be produced by an overexposure to visual kitsch in the ‘worlds of bad taste’ such as Las Vegas, Times Square, Graceland, Disneyland and the entire of Switzerland (Botox also produces the visual symptoms of undead zombie-ness, if only on the surface).

Laffoley makes an art form of metaphysical and conceptual speculation, continually pitching us into unbelievable worlds, pushing our incredulity and testing our abilities to think of reality in radically different ways like an instructor of transcendental yoga. He believes true science fiction died in 1955 with Robert Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land and that after that the genre “became ad hoc research and development for companies” – think the communicator from Star Trek and the mobile phone in your pocket. In this sense, we could see Laffoley’s ‘fictions’ as mapping out the radical contours or terrain of the scene of our future thought and consciousness. He believes that all knowledge is a mix of the physical and the metaphysical; conceiving the world in terms of spirit, matter or the opposition of the two is incorrect – rather “there are degrees of characteristics from one to the other”, and whilst our analogies and grasps at conceiving the world inherently fail, “each time it leaves in its wake a nomenclature that gives you the memory of having come up against a problem and from which you can eventually forge on”.

kentfineart.net

paullaffoley.net

#paul laffoley#thanaton III#kent gallery#douglas walla#richard metzger#disinformation#art#outsider art#andy warhol#vampire#fashion#zombie#clone#beauty#sublime#dimensionality#time travel#frederick kiesler#igoe pruitt#bauharoque#visionary art

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Genesis: Breyer P-Orridge

Self-styled cultural engineer, seminal performance artist, musician, poet and 'cult' leader, and someone whose life has always been lived as a work of art, Genesis Breyer P-Orridge was always going to be nigh impossible to adequately introduce. Whether one focuses on the legendary Throbbing Gristle, being decried as a 'wrecker of civilization' or the unfounded Tabloid accusation of being a child abusing Satanist that ran him out of the country, the performance works of COUM Transmissions or the cosmetic surgeries redefining identity and gender in the Pandrogeny project, far too much will always be left out. One thing is certain, not least in name alone, Genesis is one of the most Biblical entities active today.

Now resembling some bleached blonde crusty biker's grandmother, despite the final termination of TG after the sad passing of Peter 'Sleazy' Christopherson, Genesis has lost none of her cultural resonance or import. Two films, several exhibitions, future PTV3 shows and a series of poetry books in the works promise to introduce Genesis as a matriarchic icon of the 'counter' culture for yet another generation.

In many ways, P-Orridge is one of our last link to the beat generation of William S. Burroughs and Gysin. Beyond personal friendships with Burroughs and other luminaries, P-Orridge has lived out their ideas and ideals unforgivingly, from the cut-up to treating language as an alien virus, all under an ethos of continual change and of individual empowerment as a spiritual quest. She links us back to a 'true' counterculture, from a time before the ubiquity of capital flattened everything into the shallows of mainstream pop.

Perhaps Genesis' last great project and a culmination of each of those coming before, outwardly the Pandrogeny project saw Genesis and her wife, Lady Jayne, having a series of matching cosmetic surgeries, breast implants and reductions, cheek re-structurings, in order to look the same. Until the tragic, untimely death of Jayne in Genesis' arms in October 2007, Pandrogeny sprang from the deepest, personal love and connection with the couple attempting to break sex, gender and identity to ultimately forge a new form of being from their union.

These themes of gender and identity carry back to the performances of COUM Transmissions, with Genesis and her then porn-model girlfriend Cosey Fanni Tutti, often exploring the interchangeability of binary gender roles. While COUM Transmissions gained increasing recognition in the art scene, earning their infamous Prostitution retrospective at the ICA in '76, the group became increasingly frustrated at the safe and cozy confines of art galleries. With Throbbing Gristle they sought to see if their strategies, practices, and perhaps most importantly, ideas of finding liberation through breaking taboos could be externalised and made into public, shared rituals via the spectacle of music. TG’s ‘avant-garde freak out’ and experimental noise enacted sonic warfare on themselves and their audiences. Originators of industrial music, pioneers of DIY self-publishing, by turns critically acclaimed and ridiculed as they waged 'nothing short of a total war', TG terminated their mission on the eve of commercial/mainstream success to remain the cult band of the next two decades. In this hiatus before TG regrouped, Genesis pioneered hypadelic pop and acid house with Psychic TV and through sister 'cult' the Temple of Psychic Youth, disseminated techniques of self-discovery, empowerment and liberation from conditioning to a new audience through the second summer of love and beyond. This is the context in which Pandrogeny needs to be seen.

It is interesting that this entity, born Neil Megson in Manchester in 1950, refers to 'Genesis' as an avatar and thus highlights the extent to which identity is a construct and a projection outwards into the various social and cultural spheres of conditioning we find ourselves embedded within. Throughout every project and artistic practice P-Orridge has engaged with she has always problematized and challenged what has heretofore been held as immutable, and aimed at exposing the contingencies that we often overlook as a means to advance our freedom. With Pandrogeny, Genesis and Lady Jayne Breyer P-Orridge attempted to reach beyond the confines of our gendered bodies, our times and places, towards a higher level of being and a liberated identity.

Within imagined scenes of our tele-connected worlds of the future, as our identities and personas expand exponentially outwards through the profiles, platforms, and people we engage with, as the accelerating changes to our world push exponentially onwards and the crushing event horizon of the future bears down upon us as a singularity, as our increasing symbiosis with the entire digitized memory of the species loosens our grip on the present and our ubiquitous tele-presence loosens our grip on space, in worlds beyond gender, race or perhaps even age, P-Orridge offers us a simple question: that there, are we not all Pandrogyn?

On being a cultural engineer

Once was somebody asked me to sum up in a few words what it was that we really did. We’d been looking at the Muzak Corporation at the time and they had a sign up in the foyer of their building, ‘a concept in human engineering’, which sounded really 1984 and sci-fi. We thought that we do is really ‘cultural engineering’. It was not carefully thought through when we first improvised the idea, but it made sense on various levels. You could argue that, for example with Throbbing Gristle deciding to call our music ‘industrial music’, we inserted that concept into the prevailing popular culture and quite literally changed it forever. 35 years on and it’s a huge industry, globally. It all began with a dialogue in a squat in Hackney in 1975. The work we do is not to just create art, put our name on it and go, “Look at me I’ve made this beautiful, original object”. Our interest is more in how to interface with and explore the prevailing culture in order to destabilise it, adjust it or reveal the underlying messages inside. That’s why we tend to work collectively and with long-term concepts.

On the control process

Brion Gysin used to say that the cut-ups happened at a time, in what he called a ‘hotspot’, when the Beat hotel was there with him, Burroughs, Ginsberg, Kerouac sometimes and all these other people. The seeds at work all occurred in that year in this rundown hotel. That happens at certain points in the culture; you get hotspots. What we try and do is almost scry or put feelers out to see where it is shifting and changing, what’s happening in the way people perceive everything, to get us to the control point. Popular culture to us is part of the architecture of control and is used to co-opt and emasculate subversion. As an activist from the 60s, to me you can’t just stand by and be a spectator, you have to be involved in that process, try and see if it can be made potent again, if there’re ways to create change. To do that you have locate where the pressure is that makes people censor themselves. Culture and control are linked in self-censorship, now more than ever. In this bogus concept, the art market, where things sell for millions and millions, it has nothing to do with trying to further or expand human consciousness and our perception of what we are as beings. For us, art should always ultimately be about human-kind and how to change the species in the end to be less destructive and more constructive.

On the ‘Genesis P-Orridge’ avatar

Back in 1965, Neil Andrew Megson thought, “What would it be like to take Warhol’s ideas of the superstar and 15 minutes of fame even further, to consciously create a character that one would then insert into the popular culture? If that character had none the usual requisites to succeed in any of the media they chose to be active in, could it be done? Could somebody with no art training and no financial backing, no social network or free masonry, actually create an icon of themselves that would eventually become a vibrant part of the culture, that could become at least a semi celebrity.” So Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, as we are now, was an artwork created by this other person. One of the weirdest questions is, ‘Does Neil still exist?’ or ‘Did Neil create this monster that has completely devoured him?’ So we are somebody else’s artwork and that’s a strange thought.

It’s almost like trying to imagine what happened before there was anything, before the Big Bang? Nothing. Your brain can’t do it. “Where’s that guy that invented me?” Because we exist so completely in the ‘Genesis Breyer P-Orridge’ construct, we rarely remember there was a Neil.

On the genius factor

Learning about art at the beginning from reading books about Dada, Surrealism, and Andy Warhol, all of them struck me as important in that these were all people who didn’t see any separation between performance and fine art, life and art. It was all one thing. Anything could be art, anything could be life and the way that you lived your life was also the art. That was ingrained in me from the very beginning and is still our modus operandi.

The performances in COUM were about looking for the ‘genius factor’, as we called it, that everybody can find a way to be creative and do something of worth. It’s just a matter of opening them up to believe they have that possibility.

We had a big room called ‘the costume room’, and in it we had characters that we’d developed, partly in conversations, sometimes when you’re just all sat around joking. Basically there would be an outfit to wear with each of these characters. Each Friday night people would assemble at the commune, pick or be assigned a character and then for the whole weekend they would be that character, all the time. They all had to stay in character, even if they didn’t agree with anything that that character represented, which was part of the exercise. It was amazing, it was really liberating to have to be someone else and to suddenly realise how much of life is the projection of characters and symbols of what we want to be seen and perceived as. We were deconstructing social perceptions and social expectations.

Therefore if you could take off your outfit and put on another one and become someone else, that means you can be anyone you want to be and you can always change again. That was the way we were trying to go, to make everything malleable, that nothing is fixed. Nothing has to be the way it was yesterday, you can constantly reinvent, in fact it’s healthy to reinvent.

On the external deconstructions of Throbbing Gristle, Psychic TV and T.O.P.Y.

After about three years we moved to London, it was basically just me and Cosey, and the COUM performances then changed. It was just two people and it became about male/female. An important part of the story is that it suddenly became about those dynamics and gender. What is acceptable and what is not acceptable? Who makes the rules about sexuality? And if there are rules, are they viable and reasonable? Or are they unreasonable? If they’re taken away, what’s damaged, what’s not damaged? By the end, COUM was very much about personal space and one’s deeper personality, not the one you project to the public but the one that you deal with inside yourself. As you probably know, it got quite extreme by the end because we were pushing ourselves to say, “Is there point beyond?” Do we get to a point where it’s both not there and it’s there? Where is that boundary again, where it becomes impossible to describe?

We were in a pub talking to some local old guys having a beer about COUM and one guy said, “It’s all very well Genesis, but look around you, how many people in this pub would understand what the fuck you’re talking about?” And we sort of went, “Yeah you’re right.” He said, “You should do something that anyone in here could understand, find a way to do it where they would understand.” And that was the beginning of TG, to take it out of the elite, safe environment that we’d ended up in with art galleries. We could have carried on being comfortable but that wasn’t the idea, the idea was to keep pushing. So we decided to see if we could apply our techniques and our strategies to that idea of having a band, because a band goes out in public and has all these people listening. What would happen if we could somehow create the ‘anti-band’ but make it work? And that was Throbbing Gristle. It was very much about taking the message out further to the public. Then, of course, with Psychic TV and T.O.P.Y. we took it even further because we now had people’s attention, and we took them back in: “How am I built? How does my character work? Where is my sexuality, can it be used so that I can reach my maximum potential?” The same themes come through all the time, in all the projects, especially in the way that they’re constructed and perceived in terms of their impact on the current status quo, in terms of culture.

On Pandrogeny and breaking gender

In a way Pandrogeny is the ultimate project. It’s the refined elixir of all the others. We stepped back, looked and realised that amongst everything no matter how many overlays of media attention and glamour, we were trying to find out how does a personality work? How much control do we have over that? Can it be rebuilt so it’s exactly what we would like to be? That’s the constant search, to become a different being. Pandrogeny was an inevitable result of all of the other projects. It’s the last one, basically, that’s the last project personally.

On liberation as political and spiritual

It’s true that the personal liberation at the heart of our art and ideas is a mixture of spiritual and political. But it’s not political with a big ‘P’, it’s innately political to look for utopian alternatives and utopia is a spiritual quest. For me all art is and has to be about the quest for perfection, for peace, for ultimate kindness and compassion. Even though some of the work we’ve done might seem to be jarring, it’s been to jar people into an awareness that things aren’t quite as easy and comfortable as they seem and that they should actually activate themselves in order to change the way things are. But they can, that’s the thing. We always add, “You can do it, and if you don’t believe us look! We’ve done it and we didn’t have any money, etc.” We did it through sheer will power and through sharing, through sharing with other people and having their inputs as well. Basically everything we do is the sum total of everyone we know at any given moment.

It’s not about the fabulous artist, it’s about what got done and did it work? Is it a functional option for people? It’s an almost messianic thing, to want to save the human-kind from itself. It’s always an enigma because at some points you think this is such a stupid species, still fighting, maiming and killing after thousands of years… And yet it’s also a wonderful species, miraculous. Really what’s always behind it all is the search for a way to live within what appears to be reality, doing the minimum damage and inspiring the maximum creativity.

On the Sacred

We hold the potential of humanity sacred, the idea that every human being really is the owner of their own universe and capable of what we would think of as the ‘miraculous’. Everybody truly has the potential to expand even beyond the physical into pure consciousness. That that’s really what our, if we have a function as beings at all, that’s what it is. It’s for us to keep on searching for and expanding knowledge, wisdom and ideas, consciousness. The obsession with physicality and the material, consumption, endless productivity and growth is all... it’s base material, it’s a base form of existence. Personally for me, the ultimate dream for me and Lady Jayne, always was once our bodies were dead to still have enough sense of being to together become one new consciousness, the combination of both of us, and exist throughout eternity, maybe other dimensions and other universes… Who knows? But just to become one.

www.genesisbreyerporridge.com

Photos by Lukas Wassmann

www.lukaswassman.com

#genesis#genesis p-orridge#throbbing gristle#coum transmissions#psychic tv#topy#temple of psychic youth#cultural engineer#art#music#industrial#metabolic#acid house#pandrogeny#lady jayne#brion gysin#hackney#lukas wassmann

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Behold, Dis!’: The Fall of Salò

“Before being a death camp, Auschwitz is the site of an experiment that remains unthought today, an experiment beyond life and death in which the Jew is transformed into a Muselmann and the human being into a non-human. And we will not understand what Auschwitz is if we do not first understand who or what the Muselmann is if we do not learn to gaze with him upon the Gorgon.”

(Agamben, p.52)

Pier Pablo Pasolini’s film Salò o le 120 giornate di Sodoma updates Sade’s tale of debauched libertinage to the last days of fascist Italy. The film’s structure, loosely based on Dante’s Inferno, follows the progressive escalation of exploitation and violence enacted by Pasolini’s fascist libertines through three ‘circles’ of descent into hell. Through this paper we shall trace the progressive corruption and descent of Salò in pursuit of its inexplicable core. Establishing an interpretative framework for the film through considering Pasolini’s conception of cinema as the reproduction of reality we shall articulate the dehumanization of the fascists’ victims and the ‘refinements’ of the fascists’ architectonic. Finally drawing on Primo Levi and Agamben’s discussions of the Muselmann of Nazi concentration-extermination camps, we shall articulate the final ambiguously un(re)presented horror in the closing scenes of the film.

Ante-Inferno:

The ‘Ante-Inferno’, the first division of the film, is a space of transition from the external world of the viewer to Pasolini’s nightmarish dream-world in which we witness the inauguration of its logic. The film’s opening shot gazes out from the shore across water into an indiscernible horizon shrouded in blinding brightness, signifying the infinite depths of possibility within the blank (inconsistent and unstructured) celluloid. A pan shot comes in to land and the signpost, Salò. Everything that follows transpires under this primordial sign, this naming of the event. In a darkened room , silhouetted by the light of a window behind them, Pasolini’s four fascists (Duke, Judge, President and Bishop) sit like elemental watchtowers of authority around a table. With the film’s first words a field of power opens up between their mutual recognitions, its language and logic, the state of Salò, emerges enshrined in the book of rules they sign.

Bishop: “All things are good when taken to excess”.