#Victorian Britain

Text

A Wet Moon, Putney Road, John Atkinson Grimshaw, 1886

#art#art history#John Atkinson Grimshaw#cityscape#London#night scene#British art#English art#Victorian period#Victorian Britain#Victorian England#Victorian London#Victorian art#19th century art#oil on canvas

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Halloween, everyone 🦇🧪✨

Henry Jekyll, you're a devil!

We're convinced that anyone who's anyone has got to have a take on Jekyll and Hyde, especially in lieu 🎃

🌟patreon | commission us🌟🌟

Our favourite portrayal would be Flemyng's, in a very corny movie That Had Potential!

#91939art#fanart#henry jekyll#edward hyde#robert louis stevenson#league of extraordinary gentlemen#lxg#jason flemyng#halloween marathon#halloween#happy halloween#artists on tumblr#ukrtumblr#ukrart#fan art#literature#victorian britain#victorian

120 notes

·

View notes

Text

Flatland is an underrated classic that imagines life in a 2-D world. This is my review.

You’ll get a lot of answers when you ask when speculative fiction was born. Some will tell you that it began with Hugo Gernsback and the pulps. Others will say that it goes as far back as mythology and folklore. Personally, I go with those who say that it began with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, though I don’t discount earlier works such as Gulliver’s Travels or The Tempest. I say all of this because I’m taking us back to the 19th Century for today’s review. We’re going to review the classic novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott.

Imagine, if you will, a sheet of paper that is infinitely large and stretching to all sides. Now imagine that on this sheet of paper there are a series of geometric shapes, but instead of staying in place these shapes move about and have complex social lives. Welcome to Flatland, a world of only two dimensions. There is width and length, but there is no height or depth.

The book follows A. Square who is…well, he’s literally a two-dimensional square. He acts as our guide to the realm of Flatland and relates to use the ways of his countrymen and their doings. There are two main events that serve to completely change A. Square’s world view. The first is his contact with Lineland, a world of only one dimension, and the second is meeting a figure known as Lord Sphere. Lord Sphere claims to come from a strange world of three dimensions called Spaceland.

The book goes into great detail about how life works in a world with only two dimensions. For example, it is customary to meet someone by feeling them in order to determine their shape. It’s also considered polite to give directions to the way north when meeting a traveler on the road. Societal rank and job are determined by the number of sides that one has, with circles being at the top of things. Each successive generation gains an additional side, except for the low ranking isosceles triangles, though there are exceptions. Women, being incredibly sharp and pointy lines, have restrictions placed on them so that they can avoid constantly killing people by accident. We also learn much of the history of Flatland, such as why colors have been banned by the upper classes. There is some pretty great world building in this novel.

That having been said the fact the citizens of Flatland are all living geometric shapes does limit the amount of exploration that can go into their biology and physics. A. Square does hint at future explanations, but he decides that it will take up too much time and bore the reader. Or to put it another way, if you wonder how they eat and breathe and other science facts…well, I’m sure you all know the words to the Mystery Science Theater 3000 theme song. You’ll also notice that Flatland society bares more than a passing resemblance to the society of Victorian Britain. This is intentional, as Abbott intended for Flatland to be just as much a satire as a compelling story. For example, the class system of Flatland is rather absurd when given further scrutiny, but Abbott was making about about how the British class system was absurd and ultimately rather arbitrary.

Since it was written in 1884 Flatland has long since fallen into the Public Domain. As such, many other writer have tried their hand at tackling the subject matter Flatland is built upon. Usually they will focus on one particular aspect while ignoring the others. Admittedly I haven’t read any of these books, but of the ones I’ve heard of thanks to TV Tropes I’d say Planiverse sounds the most promising. It attempts to look at how biology, chemistry, physics and culture would function in a realistic 2-D world.

Have you read Flatland? If so, what did you think?

Link to the full review on my blog: https://drakoniandgriffalco.blogspot.com/2017/02/book-review-flatland-by-edwin-abbot.html?m=1

#flatland#Edwin A Abbott#2-D#2-D World#satire#review#science fiction#scifi#Victorian Britain#science fiction books#book recommendations#book review#audiobook review#audiobook#Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions#alternate dimension#speculative fiction#speculative evolution#2-D Dimension#speculative biology#public domain#public domain books#public domain literature

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

The British soldier's morale was fed not only by patriotism (`Your Country needs you') but by the unique regimental spirit that has been the envy of other armies down to the present day: one cannot let the Regiment down.

J.M. Bereton, The British Soldier

Victorian Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Officers Drill Order on Foreign Service.

#bereton#quote#uniform#british army#regiment#patriotism#regimental spirit#argyll and sutherland highlanders#victorian army#britain#victorian britain#scottish#army uniform

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

It is August 1854, and London is a city of scavengers. Just the names alone read now like some kind of exotic zoological catalogue: bone-pickers, rag-gatherers, pure-finders, dredgermen, mud-larks, sewer-hunters, dustmen, night-soil men, bunters, toshers, shoremen. These were the London underclasses, at least a hundred thousand strong. So immense were their numbers that had the scavengers broken off and formed their own city, it would have been the fifth-largest in all of England. But the diversity and precision of their routines were more remarkable than their sheer number. Early risers strolling along the Thames would see the toshers wading through the muck of low tide, dressed almost comically in flowing velveteen coats, their oversized pockets filled with stray bits of copper recovered from the water's edge. The toshers walked with a lantern strapped to their chest to help them see in the predawn gloom, and carried an eight-foot-long pole that they used to test the ground in front of them, and to pull themselves out when they stumbled into a quagmire. The pole and the eerie glow of the lantern through the robes gave them the look of ragged wizards, scouring the foul river's edge for magic coins. Beside them fluttered the mud-larks, often children, dressed in tatters and content to scavenge all the waste that the toshers rejected as below their standards: lumps of coal, old wood, scraps of rope.

Above the river, in the streets of the city, the pure-finders eked out a living by collecting dog shit (colloquially called “pure”) while the bone-pickers foraged for carcasses of any stripe. Below ground, in the cramped but growing network of tunnels beneath London's streets, the sewer-hunters slogged through the flowing waste of the metropolis. Every few months, an unusually dense pocket of methane gas would be ignited by one of their kerosene lamps and the hapless soul would be incinerated twenty feet below ground, in a river of raw sewage.

The scavengers, in other words, lived in a world of excrement and death. Dickens began his last great novel, Our Mutual Friend, with a father-daughter team of toshers stumbling across a corpse floating in the Thames, whose coins they solemnly pocket. “What world does a dead man belong to?” the father asks rhetorically, when chided by a fellow tosher for stealing from a corpse. “'Tother world. What world does money belong to? This world.” Dickens' unspoken point is that the two worlds, the dead and the living, have begun to coexist in these marginal spaces. The bustling commerce of the great city has conjured up its opposite, a ghost class that somehow mimics the status markers and value calculations of the material world. Consider the haunting precision of the bone-pickers' daily routine, as captured in Henry Mayhew's pioneering 1844 work, London Labour and the London Poor:

It usually takes the bone-picker from seven to nine hours to go over his rounds, during which time he travels from 20 to 30 miles with a quarter to a half hundredweight on his back. In the summer he usually reaches home about eleven of the day, and in the winter about one or two. On his return home he proceeds to sort the contents of his bag. He separates the rags from the bones, and these again from the old metal (if he be luckly enough to have found any). He divides the rags into various lots, according as they are white or coloured; and if he have picked up any pieces of canvas or sacking, he makes these also into a separate parcel. When he has finished the sorting he takes his several lots to the ragshop or the marine-store dealers, and realizes upon them whatever they may be worth. For the white rags he gets from 2d. to 3d. per pound, according as they are clean or soiled. The white rags are very difficult to be found; they are mostly very dirty, and are therefore sold with the coloured ones at the rate of about 5 lbs. for 2d.

The homeless continue to haunt today's postindustrial cities, but they rarely display the professional clarity of the bone-picker's impromptu trade, for two primary reasons. First, minimum wages and government assistance are now substantial enough that it no longer makes economic sense to eke out a living as a scavenger. (Where wages remain depressed, scavenging remains a vital occupation; witness the perpendadores of Mexico City). The bone collector's trade has also declined because most modern cities possess elaborate systems for managing the waste generated by their inhabitants. (In fact, the closest American equivalent to the Victorian scavengers – the aluminium-can collectors you sometimes see hovering outside supermarkets – rely on precisely those waste-management systems for their paycheck.) But London in 1854 was a Victorian metropolis trying to make do with an Elizabethan public infrastructure. The city was vast even by today's standards, with two and a half million people crammed inside a thirty-mile circumference. But most of the techniques for managing that kind of population density that we now take for granted – recycling centers, public-health departments, safe sewage removal – hadn't been invented yet.

And so the city itself improvised a response – an unplanned, organic response, to be sure, but at the same time a response that was precisely contoured to the community's waste-removal needs. As the garbage and excrement grew, an underground market for refuse developed, with hooks into established trades. Specialists emerged, each dutifully carting goods to the appropriate site in the official market: the bone collectors selling their goods to the bone-boilers, the pure-finders selling their dog shit to tanners, who used the “pure” to rid their leather goods of the lime they had soaked in for weeks to remove animal hair. (A process widely considered to be, as one tanner put it, “the most disagreeable in the whole range of manufacture.”)

We're naturally inclined to consider these scavengers tragic figures, and to fulminate against a system that allowed so many thousands to eke out a living by foraging through human waste. In many ways, this is the correct response. (It was, to be sure, the response of the great crusaders of the age, among them Dickens and Mayhew.) But such social outrage should be accompanied by a measure of wonder and respect: without any central planner coordinating their actions, without any education at all, this itinerant underclass managed to conjure up an entire system for processing and sorting the waste generated by two million people. The great contribution usually ascribed to Mayhew's London Labour is simply his willingness to see and record the details of these impoverished lives. But just as valuable was the insight that came out of that bookkeeping, once he had run the numbers: far from being unproductive vagabonds, Mayhew discovered, these people were actually performing an essential function for their community. “The removal of the refuse of a large town,” he wrote, “is, perhaps, one of the most important of social operations.” And the scavengers of Victorian London weren't just getting rid of that refuse – they were recycling it.

�� The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic - and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World (Steven Johnson)

#book quotes#steven johnson#the ghost map#the ghost map: the story of london's most terrifying epidemic - and how it changed science cities and the modern world#history#sanitation#waste management#recycling#economics#poverty#employment#labour#sociology#homelessness#welfare#authors#britain#victorian britain#england#london#thames#mudlarks#toshers#tanners#charles dickens#henry mayhew

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dinner at Haddo House, 1884 by Alfred Edward Emslie.

Depicted people;

John Hamilton-Gordon, 1st Marquess of Aberdeen and Temair

Ishbel Hamilton-Gordon, Marchioness of Aberdeen and Temair

Henry Drummond

Victor Bruce, 9th Earl of Elgin

Lady Constance Mary Carnegie

William Ewart Gladstone

Helen Gladstone

Catherine Gladstone

Edward Glyn

Mary Campbell

#art#art history#Alfred Edward emslie#Alfred emslie#Victorian era#victorian britain#victorian Scotland

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grim Doings in Victorian Britain

#body#snatcher#BlodigRodion#resurrectionists#vintage photography#victorian britain#Victorian#photography#grim#black and white#mine#me#grave robber

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Remember that you are an Englishman, and have consequently won first prize in the lottery of life."

Cecil Rhodes, former Prime Minister of the Cape Colony

Born 5th July 1853

Died 26th March 1902

#cecil rhodes#cape town#quotes#quoteoftheday#victorian britain#british#english#queen victoria#africa#good idea#idea#plan#ask me anything#late night blogging#royal family#south africa#british imperialism#imperialism#english language#england#patriotism#patriotic#Patriot

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Marking the 125th anniversary of the publication of Dracula, Roger Luckhurst tells Ellie Cawthorne why Bram Stoker’s vampire thriller has had such an enduring appeal. They discuss how the book exposed the anxieties of the late Victorian age, how contemporary readers reacted, and some of the most intriguing adaptations.

#Dracula at 125: what can a vampire tell us about Victorian Britain#Dracula#History Extra podcast#Victorian Britain#victorian novel#victorian#victorian history#books and literature#books and writing#books and libraries#books and authors#books and reading#books#podcasts#podcast#history#reading#vampires#vampire

1 note

·

View note

Text

love the concept of transfem fitzjames not just because it's both fun to headcanon characters as trans and also thematically appropriate in her case but because i feel like she'd be so ideologically incoherent about it. she'd be like i should be allowed to fight and die in a war not because i'm a man or a woman but because i'm james fitzjames and i can do anything. diversity ??? this trans woman is defying traditional gender roles in a way that seemingly benefits absolutely no one.

#🐉#the terror#i love her. but i think its important to recognize that shes completely deranged and she/her pronouns wouldnt change that.#james fitzjames voice dont treat me like a [remembers im a woman in victorian britain] normal person.

434 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Quayside, Newcastle upon Tyne, Arthur Edmund Grimshaw, 1895

#art#art history#Arthur Edmund Grimshaw#cityscape#Newcastle upon Tyne#England#United Kingdom#night scene#British art#English art#Victorian Britain#Victorian England#Victorian period#Victorian art#19th century art#oil on canvas#Laing Art Gallery

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

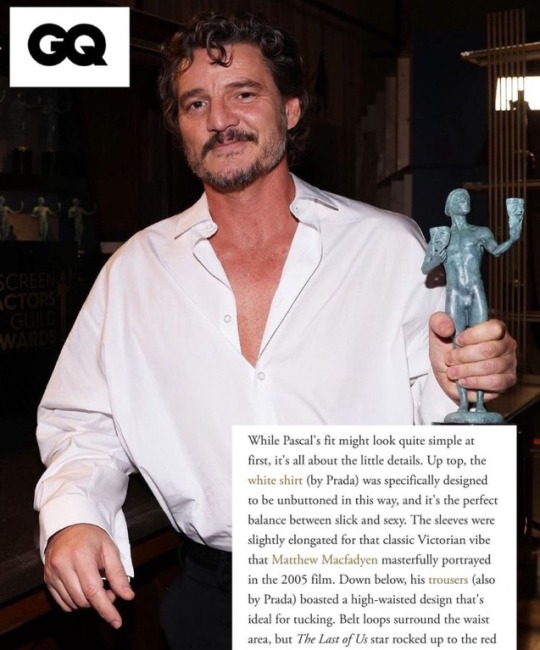

Permission to be a nerdy expert and deeply thirsty for two minutes.

I am begging - begging - fashion writers et al to realise that “Victorian” is a specific time period and place, not an entire century. And if you must insist on the Darcy comparison (about which more anon), then recognise that Pride and Prejudice was published in 1813, aka the Georgian/Regency period. (Victoria wouldn’t become queen for almost two decades.)

And that being said: I stand by my read of the whole look being far more 1830s European Romantic.

Now that I’ve got my nerdy twitching out of the way: I would like to hear more about the whole “making a shirt that’s nicely oversized and designed to be opened like that” design process please and thank you. 😘

#let me nerd out on this please#Victorian doesn’t mean 19th century and shouldn’t be used to refer to anything outside Britain#just say no to everything being framed in the Anglosphere#other references exist beyond pride and prejudice and the regency and I’m begging people to realise that#thank you for coming to my ted talk#pedro pascal#it’s fashion baby

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Downham Hall - a modest Lancashire retreat in the lush Ribble Valley

#Downham Hall#Ribble Valley#Lancashire#English mansions#rural britain#country estate#landscaping#Victorian era#UK#classic architecture#Lord Clitheroe#squire#Georgian#1835

50 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Costume design by Wilhelm (William Charles John Pitcher) for a character in the operetta Le Voyage dans la Lune' or A Trip to the Moon, 1883,1898, or 1910

#creatures#aliens#moon creatures!#william charles john pitcher#I think the moon creatures sing a song#I would go back in time to see the moon creatures sing their song#britain#england#europe#opera#costumes#costume designs#La Voyage dans la Lune'#A Trip to the Moon#victorian#19th century#watercolor#pencil#ink#drawings#paintings

608 notes

·

View notes

Text

But the single most important factor driving London's waste-removal crisis was a matter of simple demography: the number of people generating waste had almost tripled in the space of fifty years. In the 1851 census, London had a population of 2.4 million people, making it the most populous city on the planet, up from around a million at the turn of the century. Even with a modern civic infrastructure, that kind of explosive growth is difficult to manage. But without infrastructure, two million people suddenly forced to share ninety square miles of space wasn't just a disaster waiting to happen – it was a kind of permanent, rolling disaster, a vast organism destroying itself by laying waste to its habitat. Five hundred years after the fact, London was slowly re-creating the horrific demise of Richard the Raker: it was drowning in its own filth.

— The Ghost Map: The Story of London's Most Terrifying Epidemic - and How it Changed Science, Cities and the Modern World (Steven Johnson)

#book quotes#steven johnson#the ghost map#the ghost map: the story of london's most terrifying epidemic - and how it changed science cities and the modern world#history#sanitation#waste management#medical history#sociology#victorian era#britain#victorian britain#england#london

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia with her sister Queen Alexandra of the United Kingdom, during Russian state visit in 1873.

#Empress Maria Feodorovna of Russia#Empress Maria of Russia#Empress Maria Feodorovna#Empress Maria#princess dagmar of denmark#Queen Alexandra of Great Britain#Queen Alexandra of United Kingdom#Queen Alexandra#princess alexandra of denmark#Princess Alexandra of Wales#Tsarevna Maria#Princess of Wales#1870s#1873#1870s fashion#victorian#romanovs#imperial russia#Imperial Family#british royal family#british royals#British Royalty#denmark royalty#denmark royals#Dagmar of Denmark#alexandra of denmark#history colored#digital coloring#colored photography#b&w picture coloring

241 notes

·

View notes