#it being Chinese was kind of central to the story? and it adapt that into a non Chinese history would be difficult to say the least

Text

May Reading Recap

A Memory Called Empire and A Desolation Called Peace by Arkady Martine. Rereading A Memory Called Empire was a treat - an expected treat, but it was good to find out that it lived up to memory. I liked A Desolation Called Peace a little bit less, but only a little bit - it very much followed up directly on the themes from A Memory Called Empire that I appreciated.

The Last Graduate and The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik. I devoured these books. I'm very surprised by this fact, since I'm not generally a "magic school" person, but there we are; Naomi Novik apparently managed to make me one temporarily. The last book was a particularly strong one and did some very interesting things with its worldbuilding that'd been set up in previous books and delivered in the last one.

Armageddon: What the Bible Really Says About the End by Bart Ehrman. I've read and enjoyed some Bart Ehrman previously, but I feel like the quality of his books has diminished from his earlier work, and this book confirmed that for me. I'm a bit of an eschatology enthusiast (the main reason I picked this up, as well as the fact that (a) it was available at the library one time and I grabbed it on a whim and (b) author recognition), but I learned very little from this book that I didn't already know.

Strange Beasts of China by Yan Ge. One of the things that made me happiest about reading this book was, unfortunately, the fact that I thought I recognized the ways in which it was referring back to Classic of Mountains and Seas, which I felt (again, unfortunately) sort of smug about. Checking the Wikipedia page for the book, apparently "Additionally, each chapter begins with a brief description of the beast which, in the original writing, was written in Classical Chinese, while the rest of the book was written in standard Chinese," which is so cool and I wish had been conveyed in the translation.

In general though, this was a good one, though I feel like the descriptive copy was a little misleading. It's less a mystery than a series of interconnected stories following a central character investigating the titular strange beasts, and learning how they connect to her life and history.

Dark Heir by C.S. Pacat. I liked this one significantly more than Dark Rise - which I guess makes sense, since a lot of Dark Rise was setting up the concept that most compels me about the series (the main character being the reincarnation of a notorious villain from the past). It still feels YA in the way that YA usually does, which isn't necessarily a bad thing if stylistically less my preference (and something I feel worth mentioning in the context of a possible recommendation). The ending was a gut-punch of a fun kind. I will be looking forward to reading the third one.

"There Would Always Be a Fairy-Tale": Essays on Tolkien's Middle Earth by Verlyn Flieger. I loved Splintered Light and was disappointingly underwhelmed by most of the essays in this collection. There were a couple that were more interesting to me, but on the whole a lukewarm response.

The Doors of Eden by Adrian Tchaikovsky. Adrian Tchaikovsky wins again!!! I don't love this one quite as much as I've enjoyed the Children of Time series, but I actually think that I liked it more than The Final Architecture series. Fascinating concept, as usual fascinating worldbuilding for societies wildly different from our own, and dedicated to themes of cooperation and unity-across-difference without it feeling preachy or didactic.

Aphrodite and the Rabbis: How the Jews Adapted Roman Culture to Create Judaism as We Know It by Burton Visotzky. This was a good one! I already was familiar with some of the information here, but not all of it, and the work around art and architecture was new to me. I felt in some ways like Visotzky overstated his case a little, but on the whole a very interesting read.

Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical Narratives by Phyllis Trible. This one is kind of a classic of feminist Bible scholarship - a short book that does a close reading of the text of the stories of four biblical women who suffer in some way (Hagar, Tamar, the unnamed woman from Judges 19, and Jephthah's daughter). It's a powerful work, though it felt a little basic to me on the whole - probably due to the fact that it's relatively early scholarship on the subject working from a literary angle.

Nevernight by Jay Kristoff. Books with footnotes are very hit-or-miss for me - not meaning books with contextual footnotes, but books with footnotes that are part of the conceit of the text itself. Some authors can pull it off; others really shouldn't try. In this case, the author felt a bit too taken with his own cleverness to pull it off; in general I felt like this book was trying a little too hard to be edgy and voice-y and ended up just feeling kind of shallow. It was a fun read, in some ways, but not a good one, and I'm torn on if I'm going to continue reading the series. If I do, it probably won't be in a hurry.

Tolkien and Alterity ed. by Christopher Vaccaro. I was excited about this particular collection of essays (you can probably guess why) and found them mostly uninspiring in the reading. The exception was a bibliographic essay on the treatment of race in Tolkien scholarship, which proposed more use of reader response theory, a suggestion which seems fruitful to me and more interesting than debates about whether or not Tolkien/his works are or aren't racist.

Knock Knock, Open Wide by Neil Sharpson. I feel like this is going to sound more critical than I really mean it to, but this was a perfectly adequate horror novel. I wouldn't call it exceptional, and it didn't freak me out, but I read it pretty much straight through and enjoyed the experience on the whole.

Thousand Autumns: vol. 4 by Meng Xi Shi. I liked this volume more than I've liked some of the others, and am enjoying the development of the central relationship, though I feel a little like I've been bait-and-switched about the level of fucked up that it's involved. Maybe that's why I'm enjoying this one a little less than I feel like I should: I was expecting more fucked-up between the two main characters based on the initial conceit and don't feel like the novel has really delivered on that. But I am enjoying Yan Wushi getting a little more...outwardly affectionate toward Shen Qiao, and Shen Qiao's concomitant confusion about it.

This Wretched Valley by Jenny Kiefer. More than an adequate horror novel but less than an excellent one, I felt like this book relied more on gross-out horror than I typically prefer. Still, was definitely spooky, and confirmed for me that wilderness horror gets to me in a very specific way.

I'm presently reading Goodbye to Berlin by Christopher Isherwood, which I have mixed feelings about (not negative! just mixed). I'm not sure what I'm going to read after that, save that I'm now trying to alternate genres and might try to read some nonfiction, which I've been sort of off for a while. Otherwise I'll probably just end up reading Translation State by Ann Leckie, and possibly A Fire in the Deep by Vernor Vinge. But I'm really going to try for some more nonfiction next month.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

New three body problem adaptation??? Westernized? Hm.

#I’m going to watch it because my mom wants to watch it#so we’re gonna watch it together#but let the record show I have some… reservations#I’m not against a reimagining of the story I just think#it being Chinese was kind of central to the story? and it adapt that into a non Chinese history would be difficult to say the least#and to be directed by the game of thrones directors and trust them to do something like that well?? um.#I’m glad they’re not making the characters white tho from what I’ve seen#still it’s pretty sus#but yeah my mom asked me to watch it with her and I thought she was talking about the Chinese drama and I was like !!! yeah bc I’ve been mea#*meaning to watch it forever but I was also like ??? bc it’s 30 episodes long and not dubbed afaik and it’s very ooc for my mom to want to a#*watch something that long and she has dyslexia so she doesn’t really do well with subs#then I remembered about the new one but I didn’t realize it was in production so I forgot about it#but yeah. anyway. I still need to watch the drama tho#three body#.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Knowing Shintoism

Shintoism is a traditional religion originated in Japan that has influenced the Japanese people’s view of the world. It is rooted in Japanese culture. Shinto means “the way of the gods” or “the way of the divine”. This is based on a belief system that everything existing in this world, whether living or not, has a spirit or also known as kami that is deserving of worship and respect. Kami can be from anything like mountains or rivers.

ITS ORIGIN

Shintoism is believed to be a religion with no founder. However, it arose with unification of Japanese people back on the 6th century BC. Shinto was created for the native religion to distinguish it from the Chinese religion and philosophy, Confucianism and Budhism. Buddhism overshadowed Shintoism as the gods were considered as manifestations of Buddha. Originally, Shinto shrines were taken care of by Buddhist priests, who mixed Buddhist rituals with Shinto practices.

In the 9th century, a new religion called Ryobu Shinto, which means the Shinto of two kinds), combined elements of Shinto, Buddhism, and Confucianism. This was established by Kukai or Kobo Daishi, with Buddhism denominating Shinto and adapting the elements of Confucianism. This is the time where Shinto became less prominent. Emperors themselves had become Buddhists and Shinto-priests became fortune-tellers and magicians.

In the 18th century, Shinto was revived as a nationalistic religion, emphasizing the emperor's divine right to rule and Japan's superiority. This is through the writings and teachings of a succession of notable scholars, including Mabuchi, Motoori Norinaga, and Hirata Atsutane. This ideology fueled Japanese military expansion before WWII.

Beliefs

The followers of Shintoism mostly believe in spiritual powers. They also believe that there are spirits living inside natural living things or places. One of the concepts they believe in is comparable to yin and yang, where everything has its opposites. These things, as they say, are meant to balance and live in harmony. Examples of these are the sun and moon, fire and water, and the world and netherworld.

Gods

At the heart of Japanese mythology lies the story of the sun goddess Amaterasu Omikami. Amaterasu, the most revered, is considered the ancestor of the Japanese emperors. Amaterasu, also known as Amaterasu Omikami, is a superstar in Japanese mythology. Her name translates to "The Great Divinity Illuminating Heaven" – basically, the sun goddess who rules the heaven she's also known as Ohirume no Muchi no Kami, which means "The Great Sun of the Kami".

Alongside other divine spirits (kami), creation myths tell of Izanagi and Izanami birthing the Japanese islands and ancestral kami.

Legends recount her descendants, like Jimmu, the supposed first emperor, unifying the people.

This divine lineage is further emphasized by the Three Sacred Treasures – a mirror, sword, and jewels – passed down from Amaterasu, symbolizing the emperors' divinely ordained rule.Even today, the Inner Shrine of Ise-jingu, dedicated to Amaterasu, stands as a testament to her enduring legacy in Japanese mythology and Shinto religion.

DOCTRINES

At the heart of Shintoism lies a profound reverence for kami, the mysterious and harmonizing spirits believed to inhabit all aspects of existence. Central to Shinto belief are concepts such as musubi, the creative force of kami, and makoto, the truthful will of these divine beings. Though the nature of kami transcends human understanding, devoted followers apprehend them through faith and recognize their polytheistic manifestations. Each shrine's parishioners regard their tutelary kami as the source of life and existence, believing in their divine personalities and the power of truthful prayers to evoke responses from them. In traditional Japanese thought, truth is embodied in empirical existence and is constantly transforming. Makoto, the truthful way of kami, is discerned through every moment and encounter with these divine entities. Shinto teaches that living in accordance with a kami's will not only garners their protection and approval but also fosters a mystical power that gains the cooperation and support of all kami. However, there are some key principles and beliefs that are commonly associated with Shintoism:

Kami: Shintoism revolves around the concept of kami, which are sacred spirits or divine beings that inhabit natural elements, objects, and phenomena. These can include deities, spirits of ancestors, and even spirits of natural features like mountains, rivers, and trees.

Harmony with Nature: Shintoism emphasizes a deep reverence for nature. Nature is seen as inherently sacred, and humans are encouraged to live in harmony with it, respecting and appreciating its beauty and power.

TRADITIONS

Visiting Shrines (Omairi)

Shinto shrines (Jinji) are public places constructed to house kami. Anyone is welcome to visit public shrines, though there are certain practices that should be observed by all visitors, including quiet reverence and purification by water before entering the shrine itself. Worship of kami can also be done at small shrines in private homes (kamidana) or sacred, natural spaces (mori).

Purification (harae or harai)

It is a ritual performed to rid a person or an object of impurity (kegare). Purification rituals can take many forms, including a prayer from a priest, cleansing by water or salt, or even a mass purification of a large group of people

Kagura (Ritual Dances)

Kagura is a type of dance used to pacify and energize kami, particularly those of recently deceased people. It also is directly related to Japan’s origin story, when kami danced for Amaterasu, the kami of the sun, to coax her out of hiding to restore light to the universe. Like much else in Shinto, the types of dances vary from community to community.

FESTIVALS

Matsuri

A matsuri is a traditional festival that honors the Japanese gods with processions, dances, performances, and parades. Usually accompanied by yatai, games, and beverages, this religious celebration takes a very colorful turn. In Japan, matsuri are held throughout the year.

Spring Festival (Haru Matsuri, or Toshigoi-no-Matsuri; Prayer for Good Harvest Festival)

Springtime (January to May) is a period for haru matsuri, or festivals, many of which revolve around the sowing of crops. Around the nation, various shrines celebrate on different days. This springtime ceremony provides an opportunity to thank the gods for a bountiful harvest.

Autumn Festival (Aki Matsuri, or Niiname-sai; Harvest Festival)

During the late summer and early fall, there are several aki matsuri, or autumn celebrations, where people praise the kami for a bountiful crop. Around the nation, various shrines celebrate on different days. The Imperial family performed rites at the festival's initial harvest celebration to express gratitude for a bountiful crop production

Annual Festival (Rei-sai)

This is an annual celebration that falls on a certain day that is significant to the shrine hosting it. During this celebration, the local kami are paraded through the town or village in effigy while riding on an elaborate litter known as a mikoshi, which resembles a sedan chair. There are frequently musicians and dancers accompanying the procession, and the event is joyous overall. Within the shrine, more solemn rites are held.

Divine Procession (Shinkō-sai)

A mikoshi, or "divine palanquin," is frequently seen in the processions carrying a kami or an image of a kami. A common description of the mikoshi is that of a transportable altar or shrine.

The local community that is devoted to the kami of the shrine is visited by them during the mikoshi parade, which is believed to bestow a blessing onto them.

Since Shinto's roots lie in Japan's agricultural antiquity, the majority of its festivals coincide with the agricultural seasons

3 SECTS OF SHINTOISM

Shrine Shinto, is the oldest way of practicing Shinto, is like visiting special buildings called shrines to honor spirits of nature and ancestors (kami) with gifts and ceremonies. It's been around for a very long time and is connected to Japan's royal family. This type of Shinto puts a lot of importance on living in balance with nature. This sect is also called Jinja Shinto.

Sect Shinto, also known as Shuha Shinto, is a bunch of newer Shinto groups that started in the 1800s. Unlike Shrine Shinto, these groups often have a clear leader, specific beliefs, and organized structures. After World War II, even more groups popped up, with some wanting to bring back old practices, some mixing Shinto with other religions, and others focusing on healing through faith.

Folk Shinto, or Minzoku Shinto, is all about honoring kami in your daily life, especially in rural areas. People show respect to small statues on roadsides and perform rituals during different parts of the farming year to bring good harvests and keep their families safe. These traditions are often passed down from parents to children and continue within communities.

1 note

·

View note

Text

a subtle detail among the cultures in atla: the water tribes have extremely limited depictions of written and visual culture although it’s clear throughout the series the characters, at least from the southern water tribe, are perfectly literate in the lingua franca and use it in messages and on maps to communicate when necessary. As opposed to the secular uses of writing and image prevalent throughout the Earth and Fire Kingdom (used for advertising, government propaganda, and policing of citizens) symbolic depiction seems to have spiritual relevance in the Water Tribes. Even compared to the murti-style statuary representations in the air temples, the water tribe’s visual culture seems particularly ascetic.

Refined symbols are painted over the ajna (third eye) chakras during rites of passage and warrior ceremonies. Pictograms also reside on the gate in the Spirit Oasis, along bridges, and on the protective wall to the NWT, suggesting a mystic significance, even power, to these rare images. This aligns with a number of indigenous belief systems that historically restricted symbolic depiction to impermanent forms during community ceremonies (for a really complicated and interesting example of controversies around this iconoclasm in the face of colonial tides, see Hastiin Tlah, a nadleehi/non-binary spiritual leader and weaver in the Navajo Nation in the first half of the twentieth century). In fact, even much of their architecture has a temporary quality, being made of snow and ice or tents of animal hides. When you observe the significance of visual representation in the Water Tribe culture, it adds to the importance of the Waterbending scroll Katara finds in the first season. It’s not simply a book someone took from a library. Katara likely saw it more as a pillaged sacred relic that wasn’t supposed to be seen by those outside the community.

More prevalent and important to Water Tribe epistemology, especially in the moment of their history the audience finds them, is the oral tradition. Since visual representation is instilled with dangerous power, the passing of culture through stories and relationships takes a central role in their culture. “Earth. Fire. Water. Air. My grandmother used to tell me stories about the old days.” That’s the first line of the series, and those first four words can be understood as an established tradition to opening an oral story (and the written Chinese characters alongside images of benders that accompany it point us to a kind of traditional/spiritual storytelling incantation in this practice rather than simple communication). The Water tribes’ oral traditions and limits on recording knowledge, on one hand, made the water tribe’s knowledge vulnerable to erasure through means of genocide, a fact the Fire Nation takes advantage of in their sieges of the SWT--especially directed at the women who served in that community as the maintainers of spiritual knowledge, not to mention their connection, too, to healing practices. But the intangible qualities of oral epistemologies make them elusive, too. They adapt and persist within the broad community in the face of formal attempts by conquerors to eradicate individuals through acculturation and violence. It’s this quality that opens the series and makes Katara’s faith in the Avatar’s existence and return possible. Her mother gifts her life, a grandmother gifts her the stories, and she holds them, embodies them, and shepherds them out for others into the world as a form of resistance.

#atla meta#water tribe#swt#nwt#katara#also the way the show structures a lot of storytelling into the series too#it's really lovely

463 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, I hope you're doing well! I recently read what you shared RE: the risk of being outed for GG/DD & I appreciate your insight. Would you mind sharing your thoughts on the popularity of The Untamed in China, and the production of other BL dramas given the issues of censorship and cultural perceptions of queerness? If dramas with queer subtext are profitable, are those in power willing to "overlook" the queerness as long as it's done in a way that can be plausibly denied? Thanks for your time!

Happy 2021 Anon! I may not be the most qualified to answer the question about popularity, because I feel these answers can only be discerned at the ground level-- ie, I have to live in China, or have to have followed the the developments on China’s social media since the airing of the series. Because of time limitations, I’ve been satisfying my curiosity about the cultural aspects surrounding The Untamed and BJYX mainly by scouring the internet for news, social commentaries and opinion pieces. This weekend is the first time I do more than observe and interact directly with fans of the series and the pairings. :)

Re: censorship, and the government’s response to the onslaught of “adapted” BL dramas (“dangai”). Here’s my admittedly still very limited knowledge so far. First of all, I think it’s important to emphasise that there are three censorship issues surrounding these dramas:

1) the original works from which the dramas are adapted, which are often called IP (Intellectual property). These stories are published online, and therefore bypass the censorship board

2) the queer / BL elements of these works, in word form

3) how the queer / BL elements are handled when they are adapted for TV, which has its own set of censorship rules.

International fans often focus on 2) and 3). 1), however, is the one that I believe has got the most attention from the government — it’s a flaw in the country’s tightly-controlled speech environment. Millennials are avid IP readers; IPs are also very popular among overseas Chinese readers (ie, they can be effective propaganda tools).

I’m not sure if this is common knowledge among its international fandom, but this is something I think all Untamed fans should know:

In 2020 November, the author of MDZS, Mo Xiang Tong Xiu (MXTX) (real name: Yuan Yimei 袁依楣, was sentenced for “illegal business operation (非法經營) ”. The details of the sentence — including if she’s found guilty or not — was not disclosed (Reminder that China isn’t a transparent country). According to insiders, MXTX was sentenced to three years imprisonment, + 400,000 RMB (~61,227 USD) in fines. (Sorry, can’t find a good English link)

(This is yet another example of China’s lack of transparency.)

(For reference: the conviction rate in China’s judicial system is 99.93% in China in 2013, and 99.97% in 2018 and 2019.)

News of her arrest first spread in August 2019 (when The Untamed aired). At the time, Jinjiang, the site where her works were hosted, denied being under any investigations related to her. Still, fans continued to be suspicious as MXTX was known to be very good at advertising her works, creating merchandise etc. She hadn’t updated her site since February 2019 and remained quiet through the airing of the Untamed, when most authors would ‘ve said something, especially considering the series’ popularity.

What does it mean by “Illegal business”? Some says it means publishing their works without going through publishing houses. This has been a common practice among IP writers; all publishing houses in China are licensed through the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP) and have the rights to screen / censor / ban and so, to bypass publishing houses is to bypass the censorship apparatus. Some says it is a cover for her selling pornographic material. MXTX isn’t the first BL author to get jail time. Since 2017, there have been, for example, Tian Yi 天一 and Shen Hai Xian Cheng 深海先生. Some are charged for selling pornography, some also for “illegal business operations”. 深海先生 was considered to be the first BL author imprisoned for her work (she got a 4 year sentence). In 天一’s case, the author and the owner of the printing shop both got a 10-year sentence. The cover artists got a 4-year sentence. The internet shop owner who sold the books got ten month sentence. They sold 7000 books total.

Was it the pornography that hits a nerve of the Chinese government? The queerness in the pornography? The bypassing publishing houses? No one really knows for sure. The co-sentencing of the printer and seller seems to suggest the issue is with the illegal publishing, but that, again, is a common practice. So is writing BL. If no one knows what hits a nerve, it means…no one knows how to avoid it for sure.

What people do know is this: The rights to adapt MXTX’s Tian Guan Ci Fu (天官賜福) into Donghua was sold for 40 million RMB (6.1 million USD) in 2018 July. Her arrest and sentencing have not deterred the airing and popularity of the donghua, or the preparation of the live-action drama. Not only has The Untamed been highly profitable, THE China’s state newspaper, People’s Daily 人民日報 (Overseas version), dedicated an article in praise of the series, which is considered a very high honour. The article focused on the series’ artistic direction and brushed over the dangai element, described LWJ as WWX’s best friend.

The messages from the state have therefore been mixed and inconsistent. It seems to approve of the TV series but isn’t happy with the source material, which seems to support the hypothesis that as long as the romance in the original work is modified into “socialist brotherhood” (what fans of these dramas calls the modified relationship), the government is okay with these adapted BL series. However, plausible denial from the production team isn’t the same as perception from the audience, and the temporary ban on The Guardian 鎮魂 (2018), which many would call the predecessor of The Untamed as the first popular adapted BL series, seems to suggest that the censorship board would still move to remove the drama from the shelves if the audience decides that the central relationship is queer. As far as I can tell, The Untamed didn’t generate a lot of noise before its airing, and the production team never tried to sell the drama as a thinly veiled BL — in fact, it did the opposite, intentionally or not; the rumour that Wen Qing would be paired with WWX (which, according to the unofficial BTS, seemed to be a backup plan) enraged the book fans, but also provided an impression that the BL element could be completely eliminated from the product. So, when the article from People’s Daily came out within the first few days of the series’s broadcast, it could describe the relationship between LWJ and WWX a simple friendship without irony.

This isn’t true anymore with the adapted BL dramas currently in the works. They are hotly anticipated, and internet is already filled with articles describing their BL element, and the beautiful men who will/may play the leads and what these leads have done in the original IP (that has mostly bypassed the state’s censorship board). The most likely series to challenge The Untamed in terms of popularity, Immortality 皓衣行, is already building its cp (“couple”), and is doing so for both the characters and the actors. Leaked photos not only show the leads touching each other, arranging each other’s costumes etc etc on set, but them wearing couple necklaces and matching brands of clothes off work.

(The title of an article says: even BJYX didn’t do that.)

This strategy works in that it generates buzz, successfully captures the attention (and ire, in some cases) of The Untamed fans who the marketing teams see as the target audience. I’m not sure how well or long the state can tolerate this kind of “advertisements”, however, because the underlying message is this: the “socialist brotherhood” is a joke to fool the censorship board, which isn’t a message a regime so intent on demonstrating its might wants to hear. Assuming that the economic health of c-ent isn’t in such shambles that these dramas are its only hope of avoiding financial ruin, and if I must put in a guess — there have honestly been too many logic-defying policies by the Xi regime to make educated guesses — I’d imagine, after a series or two, one of the well-respected state media will call out on these publicity stunts. Depending on how harsh the critique is (and how well the already aired dramas fare), it may put an at least temporary hold on those that haven’t been aired.

165 notes

·

View notes

Text

Madam Yu is an Amazing Character, Here's Why

What's up guys it's been 57 years but I finally have another meta lmao. Shoutout to those who helped me decide on this one, and for those who wanted the Yi City analysis? Don't worry that's coming soon lol.

So Madam Yu is a really important character in MDZS, and here’s a whole meta post about why I think she’s (in my opinion) the best-written minor character in the entire story. Quick note though, this meta is going to focus on the animation specifically, because that’s my favourite version of Madam Yu (though design-wise, Audio Drama Madam Yu is best lmao). The novel and CQL versions will be mentioned, but I don’t quite remember all the novel details and I don’t really like CQL-Madam Yu, so yeah. ^^; Also, this is talking about her character writing, not her morality as a person if she were real. Feel free to disagree with the post, but here's my take on her and why I love her despite not liking her as a person.

Anyways let's goooooooo. Warning: This is pretty long cuz I have a lot of feelings about Madam Yu ZiYuan.

Madam Yu is a very well written character, easily the best written female and minor character in my opinion. From her very first appearance, we are shown much of her personality in very little time. In the novel, we are told of her fearsome reputation and why she goes by Madam Yu instead of Madam Jiang, followed by her verbal abuse towards Jiang Cheng in front of the other disciples. In the animation, she is shown talking down to the struggling disciples and scowling as soon as she sees Wei WuXian, despite smiling at Jiang YanLi moments earlier. In CQL, she is shown with a commanding authority over her husband and children, and in all three versions we’re shown how much she hates Wei WuXian. We also see her verbally abusing Jiang Cheng (Wei WuXian in the animation) in her introduction scenes, but also some degree of motherly love showed by how she adjusts Jiang Cheng’s clothes (or showing a kind smile to Jiang YanLi in the animation).

Her introduction scenes alone tell us the core important traits of her character: That she’s a fierce and prideful woman, that she is a powerful cultivator with a frightening reputation (the animation and CQL also make a point to show ZiDian in her hands in her introductions), and that she is an abusive mother despite having love for her children (but not Wei WuXian). We also instantly understand that SHE is the reason why Jiang Cheng is so uptight about saving face for the Jiang Sect when Wei WuXian never seemed to give a fuck about it (he does, but you know, teen Wei Ying lol), berating Jiang Cheng constantly about how he doesn’t seem to be doing well enough despite being the future Sect Leader. She’s kind of the epitome of the “It’s for your own good” brand of abusive parent.

There’s a scene in the animation, Episode 6, that strongly shows the discord between her and Jiang FengMian. This scene, though hard to watch cuz my favourite character is Wei Ying, is one of my absolute favourite character building scenes in the whole adaption, which makes me sad that it’s not in the other mediums (that I’m aware of). If you haven’t seen the animation, PLEASE go watch it because gods that’s my favourite version of Madam Yu.

In this scene, Madam Yu is relaxing alone in one of the pavilions late at night, and Jiang FengMian joins her. She’s civil at first, speaking without any real hostility as she asks what he was doing out so late. He offers her a gift in the form of a jade hairpin, and says he bought it because he thought it was beautiful when she asked why he bought “such a useless thing”. Jiang FengMian then tells her of Jiang YanLi and Jin ZiXuan’s arranged marriage being called off, and while she’s obviously annoyed, she still doesn’t speak with the same fierceness or hostility as she did previously.

That is, until Jiang FengMian makes a comment about how the children should not be forced into a marriage without love between them.

This is clearly a sore spot for Madam Yu, who immediately becomes hostile. Even the gentle music takes a darker turn for the shift in tone. She then makes a comment about how “Wei Ying always causes trouble”, and subtly looks back to gauge Jiang FengMian’s reaction. As soon as her husband defends Wei WuXian, she lashes out. She accuses Jiang FengMian of treating Wei WuXian better than his own son, and goes as far as to say that if Jiang Cheng had started the fight with Jin ZiXuan, Jiang FengMian wouldn’t have been in such a hurry to help him. In Madam Yu’s defense for this accusation, it’s not completely an unfair assumption, as Jiang FengMian does canonically treat Wei WuXian better, and the fact that he didn’t even try to deny Madam Yu’s accusation is very telling. Madam Yu then laughs bitterly about how Sect Leader Jiang will always be there to clean up Wei Ying’s messes before she walks away without a word, and the scene cuts to Wei WuXian watching them forlornly in the distance.

I really really love this scene as character building, because from this scene we are very quickly shown Madam Yu’s personal problems, and how she resents her unhappy marriage and blames it on the child she believes took it from her, but the scene also doesn’t hold back on showing that she’s the one being unreasonable and unwilling to talk things out because she lets anger, pride and resentment control her. We see how she was fine and willing to try and talk at first, trying to reason with Jiang FengMian about why the marriage should be carried out, because their daughter does like Jin ZiXuan, and she also wants the Jiang Sect to have good relations to the Jin Sect like the Meishan Yu Sect does due to her close friendship with Madam Jin. This shows that she does care about her daughter’s feelings and that she’s doing what she can to help the Jiang Sect. But as soon as the sore topic of the loveless marriage is brought up, she blames Wei WuXian for it and starts the argument.

From this scene, we also learn the extent of Jiang FengMian’s favouritism and how it hurt Madam Yu as well as their son, and having Wei WuXian watching their argument creates a nice transition into the next scene where he apologies to Jiang YanLi for ruining the marriage, showing that he feels guilty about the situation and most likely, the discord between his adoptive parents in general.

As the story goes on, we see that Madam Yu’s problem is basically based ENTIRELY around Wei WuXian. She gets mad at Jiang YanLi for peeling lotus seeds for him. She gets mad at Jiang FengMian for giving Wei WuXian a choice to go or not to go to the Wen doctrine. She gets mad at Jiang Cheng for trying to calm her down and berates him for not being as good as Wei WuXian. As the audience, we are more sympathetic to Wei WuXian’s point of view, and so far Madam Yu comes off as an abusive bitch who hates him for no reason.

Then after the whole XuanWu incident, we get the scene where Madam Yu storms in on Wei WuXian’s conversation with Jiang FengMian and Jiang Cheng. And holy fuck does it make her seem even more unredeemable than she already was. She comes in right as Jiang FengMian is scolding Jiang Cheng for not upholding the family values, refusing to recognize Wei WuXian’s accomplishment and saying he was bound to bring ruin to the Jiang Sect sooner or later. When Jiang FengMian asks her why she was there, after all it’s common knowledge that she doesn’t care about Wei WuXian’s injuries, she intentionally aggravates him by literally grabbing and shoving Jiang Cheng into her husband’s face, forcefully reminding him that Jiang Cheng was their “true son”. She accuses him of disliking Jiang Cheng because she was the mother, then accuses him of actually being Wei WuXian’s real father. And with that, we instantly know what he whole fucking problem is.

It’s jealousy. She had been jealous of Jiang FengMian’s feelings for CangSe Sanren this whole time, and took it out on an innocent child who lost his family at a young age. All that unreasonable, misguided resentment, all directed towards a dead woman’s son. A dead woman her husband was most likely in love with, who hadn’t even returned those feelings.

Personally, when this scene showed up, I decided, “Yup, I fucking hate this bitch.” But I will say this, this scene was also such a good character building scene. It amplified the drama, always necessary in ancient Chinese stories, and was a catalyst that led to a very important plot point: Wei WuXian’s promise to Jiang Cheng.

Time to talk about how Madam Yu actually functions as a plot-driving character!

As I just said, this scene drove Wei WuXian to make the promise of becoming Jiang Cheng’s right-hand man in the future, and it was a promise he had fully intended to keep. Madam Yu, and to a lesser extent also Jiang FengMian, were the driving force behind that decision. By now, we as the audience fully understand the core factors of Wei WuXian and Jiang Cheng’s insecurities. Wei WuXian feels like he doesn’t have a proper place in the Jiang Family because of Madam Yu, and Jiang Cheng feels like he’s never doing enough to please either of his parents. The abuse from Madam Yu and the neglect from Jiang FengMian weighs down on Jiang Cheng’s shoulders constantly as he feels unloved by both parents, meanwhile Wei WuXian believes he is what ruined the love for the family just by being alive.

To me, Madam Yu is the strongest catalyst character in the story because she drives the story’s two central characters, Wei WuXian and Jiang Cheng, in a way that both explains and exploits their insecurities and the decisions they make because of those problems. She is legitimately the primary reason why both boys are so messed up (though Jiang FengMian played no small part in that too), and we feel the effects of her actions on the two of them long after she's dead. Which brings us to the big topic of her death.

Now, let's be real, Madam Yu was still kind of a fridged woman like Wen Qing and Jiang YanLi. However, in my opinion she was at the very least a fridged woman done right. The reason for this is that both Wen Qing and Jiang YanLi were overall much weaker characters (especially in the novel) and essentially both died for no real reason except to cause more tragedy and pain for Wei WuXian to push him to his death. They both only died to set up Wei Ying's death, which is why I'm furious about that, but that's for another post (let me know if y'all want it lol). But Madam Yu's death? Her death was far, far more significant and there's a huge reason why a lot of fans, regardless of which adaptation they follow, agree that Madam Yu's last scenes were her best ones.

Now, onto the analysis of the massacre of Lotus Pier. It started with Wang LingJiao’s pompous ass waltzing in and demanding that they chop off Wei WuXian’s hand and submit to the Wen Sect, even after Madam Yu violently lashed out at Wei WuXian with ZiDian to the point where he shouldn’t have been able to move for days (the animation doesn't agree though cuz they wanted a cool fight scene lmao). This scene is very interesting for Madam Yu’s character, because you can interpret it in two ways; one that makes Madam Yu seem to hold SOME sympathy for Wei WuXian as a member of the Jiang Sect, or another that shows her tactical insight as well as her pride for her Sect and status, or even both. Later in the story, Wen Qing reveals that Madam Yu hadn’t actually hurt Wei WuXian as badly as she claimed, and we can interpret this as either her not truly wanting to cause lasting damage to Wei WuXian, or that she knew there would be a fight regardless and made sure Wei WuXian would be able to fight the Wens off along with her and Jiang Cheng. Madam Yu has previously made it clear that she believes in Wei WuXian’s skills in combat and cultivation, shown in her berating comparison of him and Jiang Cheng, so it would make sense for her to keep one of the Jiang Sect’s strongest fighters on his feet while putting on a show for Wang LingJiao in case it was enough to satisfy the Wens into leaving them alone for the time being (while probably finally having an excuse to act violently against the poor kid she hates maybe). Personally, I do think it is more of the latter, but I also don’t think Madam Yu is one to turn to physical abuse too much. Yes, she slapped Jiang Cheng in the shoulder in the novel introduction and shoves him around when she’s angry, but aside from that we have no reason to believe she actively and frequently engages in physical abuse against them as they never seem to be scared of her in that way, and Jiang Cheng was particularly horrified and scared when she did hit Wei WuXian in that scene with Wang LingJiao, so I lean towards believing it was a rare occurrence (not that emotional abuse really any better, but you know.)

Quick bonus point, I love how in CQL she just nods at JinZhu and YinZhu and they immediately know what to do, and also when she trusted them to hold Wen ZhuLiu off while she escaped with the boys. It really shows how close the three of them are despite being mistress and servants, having grown up and trained together. JinZhu and YinZhu are criminally under-utilised and I will be forever bitter about it.

In the scene that follows, the animation has my whole heart once again. Mostly because it was the best fight scene don’t @ me, but also because it showed her fighting side by side with Jiang Cheng and Wei WuXian. Madam Yu took the frontline first, taking out the large group headed towards them before letting the boys rush forward ahead of her to fight, only taking over the main fight when Wen ZhuLiu entered the fray. During their battle, Wen ZhuLiu used the body of a dead Wen to block her attack, blinding her with blood as she paused in shock at the unexpected action. Realizing she could not win the unfair fight, Madam Yu quickly switched tactics and escaped, aiming to make sure that the Jiang heir survived. I really liked seeing her fight alongside them, even though it doesn’t totally make sense with Wei WuXian’s injury, because it does give a better look into them being able to function as combat partners. It is implied that Madam Yu trained them more than Jiang FengMian did and that'sthe headcanon I go for myself, so I enjoyed that scene a lot. Then comes her biggest defining moment, her final scene with Jiang Cheng and Wei WuXian. Please note: This is 100% the animation and why anime-Madam Yu is best Madam Yu.

Madam Yu shoves Wei WuXian into a boat, screaming that this was all his fault. She knows it’s over, that there’s no chance of winning this fight, so she gives ZiDian to Jiang Cheng, and tells him, in the softest voice we’ve ever heard from her, to leave. When Jiang Cheng starts begging her to escape with them, she gives into her emotions and pulls her son in for a hug, telling him he’s a good child. Jiang Cheng is shocked, likely never having received her affection like this before. Here, Madam Yu has no reason to hide her feelings anymore, because she knows she's going to die, and she knows she cannot bear to flee Lotus Pier as she is the Jiang Matriarch and has her pride. She spares Wei WuXian, but I don't think it's because she wants him to live. I think she spared him to ensure her hot-headed son will have someone to protect him, because she knows that Jiang Cheng will absolutely try to save her, and because she fully believes that Wei WuXian absolutely will fulfill that promise. She knows Wei WuXian is loyal to the Sect, and more importantly, to Jiang Cheng. She knows that while Wei WuXian is more reckless and impulsive, Jiang Cheng is the one who reacts more emotionally. Just like herself. When demanding that Wei WuXian give his life to protect Jiang Cheng, she’s not simply giving him an order as a master to a servant. She was telling him, in her own way, that she cannot protect Jiang Cheng as she believed she was doing any longer, and entrusts that task to Wei WuXian, because he’s the only person who can do so. In this very moment, she knows she’s walking to her death, and she knows she would never see her children again, and doesn’t know if her husband would even return for her, because she genuinely believes she’s unloved by him. So, she gives her family to Wei WuXian in the worst way possible, and we see her biggest flaw of her unyielding pride also being her greatest strength as she fights to protect her family and home one last time.

This scene, this GODDAMN scene, is Madam Yu’s most defining moment as a catalyst character, because now her character has served its full purpose. It’s the moment both we as the audience, AND Wei WuXian and Jiang Cheng, see that she is more than an abusive, jealous mother. She is more than just prideful and fierce. She’s also a “real” person with emotions and problems she never managed to work out, but did truly love her son, her family, her sect. But she was also never going to be redeemed, because she refused to face her own demons even to the very end. She was such a prideful and stubborn person, that she died upright, holding on to her sword in a refusal to kneel to the Wens. And for Jiang Cheng, to see the proudest, most powerful person he knew, dead and disrespected by Wen Chao and Wang LingJiao, well, can you blame him for snapping?

Madam Yu’s presence in the story was primarily to set up the conflict between Jiang Cheng and Wei WuXian. Her problems, her abuse, caused them to develop insecurities that became their worst flaws, with Jiang Cheng always feeling inferior because she always told him he was inferior, and with Wei WuXian’s guilt and tendency to blame himself for anything that goes wrong around him. Jiang FengMian’s lousy parenting and neglect (y'all want an analysis on him too cuz he's honestly a really interesting take on a bad parent imo), which is also a form of emotional abuse by the way, shouldn’t be ignored, but Madam Yu is simply the better and more impactful character. We see how her starting arguments with Jiang FengMian push the boys into heartfelt talks, leading to the promise between them before Lotus Pier fell. We see how she set up Wei WuXian’s feeling of owing an unpayable debt to the Jiang Sect, and to her for sparing his life to protect her son. But she also wasn’t simply a plot-device-abusive character type. She is fully shown to have her own motivations, her own problems unique to her, and her own strengths and flaws in ways that a lot of other minor characters don’t get, especially in the animation. Hell, not even Jiang YanLi, a character supposedly being more significant than her, got such an in-depth character. Madam Yu isn’t a developed character by any means, but she has a lot of depth, and the impact she left on both the audience and the canon characters is felt long after she’s dead. When Jiang Cheng and Wei WuXian break things off, Jiang Cheng talks about how Wei WuXian is the perfect disciple of the Jiang Sect, and that leads to Wei WuXian leaving so he “doesn’t cause them any more trouble”. Wei WuXian cannot abandon the ideals of the man who took him in all those years ago, but he also felt that he had given his all to Jiang Cheng already in his golden core, and thus he felt that he should respect Madam Yu’s presumed wishes and stop causing more problems for them. Even far, far later on, Wei WuXian still feels guilt towards her and Jiang FengMian’s death and wishes to pay respects, but doesn’t argue with Jiang Cheng when he’s told that he doesn’t deserve even that. And honestly, we also just know who’s fault that unreasonable guilt really is.

I say Madam Yu is the best minor character, and a fridged character done right, because she genuinely felt like an actual person, an actual abusive mother but also a human being with her own complex feelings while also being an overall bad person who (arguably) needed to be out of the protagonist's life. To get a little personal for a moment, Madam Yu strongly reminds me of my own mother, who is quite emotionally abusive, though not as extreme, which might have made me feel more realism from her than most other minor characters and definitely made me think that MXTX has some personal experiences herself. The animation is the best at this, because her tones and expressions change drastically here and there when it’s needed, plus her voice actress does such an outstanding job conveying her emotions instead of just shouting everything like the novel and CQL presents it, but she maintains her pride, the most defining trait, both her greatest strength and greatest flaw, until she was no longer needed in the story. A lot of stories with such a character tend to give them an emotional breakdown before they end their arc, but Madam Yu had none of that (...except...in CQL...I guess...yeah that’s why I don’t like that one). Her death was to push the story and the motivations of two male characters forward, and I agree that it’s not fantastic given that most other women died within the same story for male plot progress, but her death actually felt, to me at least, like it also had a genuine purpose to her own character as well as the plot. Wen Qing’s death was heartbreaking to me because I love her and she is my QUEEN, but narratively pointless especially since Wen Ning came back and in the end she was only really there to perform the golden core transfer. Jiang YanLi’s death was just...utterly unnecessary man pain. I have made no secret of hating how her death was handled.

With Madam Yu, I personally really liked that she essentially was an irredeemable person that would never change herself out of pride so she almost needed to die, but was still human nonetheless. And going by MDZS’s heavy theme of grey morality, she fits the theme perfectly. And that’s why, while Madam Yu may be an abusive and terrible person, she’s easily one of the strongest characters in the whole story, right up there with Wei WuXian, Jiang Cheng, and Jin GuangYao in my opinion.

I hope y’all enjoyed this monster of a post of me rambling about the angry purple lady.

#yu ziyuan#madam yu#mdzs#mo dao zu shi#cql#chen qing ling#the untamed#mdzs meta#my meta#mdzs donghua#my posts#my ramblings#there are a bunch of things i had to leave out im mad lol#but it would've been too long#so uh#feel free to send me asks lmaooooo

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

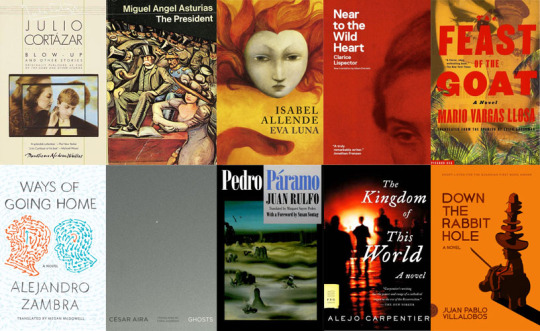

“The World’s Literature”

Literature refers to a book to a written works or books that has an extremely lasting artistic merit. It usually means works of poetry and prose that are especially well written. It is also defined as writings proposed by people with various language. It is very important not only in today’s society but also in past generations. It helps us in critical thinking, writing, reading, and understanding. It also help to share ideas or information about our history and different cultures or languages. It is also important since it will enlighten and acknowledge about the world we are living in. Etymologically, the term derives from Latin litaritura or litteratura that means “writing formed with letters,” even though some definitions include spoken or sung texts. Some examples of literature are prose, poetry, novels, drama, short stories, and more.

It is said that literature’s definition depends on varid of time. In Western Europe prior to the 18th century, literature denoted all books and writing. Then, during the Romantic Period, a more restricted sense of the term emerged that emphasize the idea that "literature" was "imaginative" writing.

https://simple.wikipedia.org/

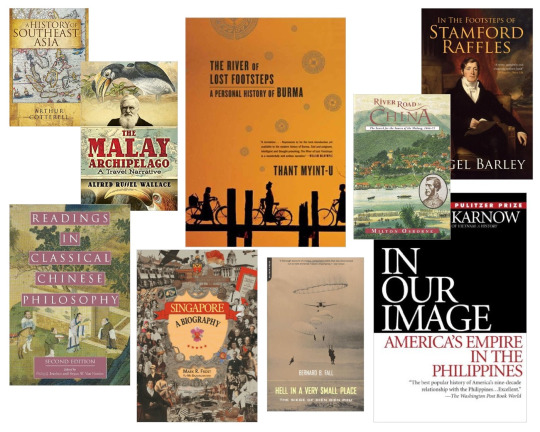

Southeast Asia is composed of eleven countries of impressive diversity in religion, culture and history: Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Southeast Asia was known as mainland of buddhism. Its influence was a major source of traditional literature in the Buddhist countries of Southeast Asia. Vietnam, under Chinese rule, was influenced by Chinese and Indian literature. Indonesia and Malaysia were influenced by Islam and its literature. All of the countries, except for Thailand, underwent a colonial experience and each of the countries reflects in its literature and in other aspects of its culture the influence of the colonizing power, including the language of that power. On the other hand, until now poetry was the most famous form of traditional literature in Southeast Asia for centuries. However, through increased acquaintance with Western poetry, the poets of Southeast Asia broke the bonds of tradition and began to imitate various poetic types. From the point of view of its “classical” literatures, Southeast Asia can be divided into three major regions: (1) the Sanskrit region of Cambodia and Indonesia; (2) the region of Burma where Pali, a dialect related to Sanskrit, was used as a literary and religious language; and (3) the Chinese region of Vietnam.

“MYANMAR”

The literature of Myanmar spans over a millennium. Burmese literature was historically influenced by Indian and Thai cultures, as seen in many works, such as the Ramayana wgich we all knew that it is very popular. Burmese literature has historically been an extremely important aspect of Burmese life steeped in the Pali Canon of Buddhism. In addition, Burmese children were educated by monks in monasteries in towns and villages. The earliest forms of Burmese literature were on stone engravings which is also called “kyauksa” for memorials or for special occasions such as the building of a temple or a monastery. Later, palm leaves were used as paper (peisa), which resulted in the rounded forms of the Burmese alphabet.

Monks is said to be influencial in improving Burmese literature. During this time, Shin Maha Thila Wuntha wrote a chronicle on the history of Buddhism. A contemporary of his, Shin Ottama Gyaw, was famous for his epic verses called Tawla that revelled in the natural beauty of the seasons, forests and travel. Monks remained powerful in Burmese literature, compiling histories of Burma. Kyigan Shingyi (1757-1807) wrote the Jataka Tales incorporating Burmese elements, including the myittaza. When Burma became a colony of British India, Burmese literature continued to flourish. English literature was still relatively inaccessible although both English and Burmese were now taught in schools.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burmese https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine

“INDONESIA”

Indonesia is centrally-located along ancient trading routes between the Far East, South Asia and the Middle East, resulting in many cultural practices being strongly influenced by a multitude of religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, and Islam, all strong in the major trading cities. Prose and poetry wrote in Javanese, Sundanese, Malay, and more, refers to a literature in Indonesia. Indonesian literature can refer to literature produced in the Indonesian archipelago. It is also used to refer more broadly to literature produced in areas with common language roots based on the Malay language (of which Indonesian is one scion). This would extend the reach to the Maritime Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, but also other nations with a common language such as Malaysia and Brunei, as well as population within other nations such as the Malay people living in Singapore. Indonesian literature is not widely known compared to works from other countries. Writings of Indonesian authors do not get translated as much as works by other authors of “Third World” countries. Literary production remained consistently high even during the repressive era of Suharto. The styles and characteristics of Indonesian literature change from time to time. They sometimes follow the political dynamics of the country and the region. In the colonial era, local authors were heavily inspired by Western novels and poetry. Many writers produced adaptations of Western fiction in their local setting or even “plagiarised” works produced by their Western counterparts. However, realism remains to be the dominant style, although sometimes it also blends with some kind of romanticism – a nostalgia for the lost past – and a sense of disillusionment that replaces it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/

“CAMBODIA”

Cambodian or Khmer literature has a very ancient origin. Like most Southeast Asian national literatures its traditional corpus has two distinct aspects or levels: The written literature, mostly restricted to the royal courts or the Buddhist monasteries. The oral literature, which is based on local folklore. On the past centuries, their literature was proposed or transmitted orally. The earliest written works took the form of Sanskrit verses inscribed on palm leaf manuscripts during the Angkorian era (9th-13th centuries). By the 11th century Buddhist treatises and jataka were being produced on a regular basis. From the 17th century onwards poems known as chbap (‘codes of conduct’) were written by Buddhist monks to teach novices about morality. These poems, written in the precise metre demanded of Khmer poetry with colourful compounds and complex rhyme patterns, subsequently became set texts in wat schools. Cambodian literature based on the contemporary world, though still inspired by classical themes, began to emerge in the mid-19th century. However, not until 1908 – with the publication of Pantan Ta Mas (‘The Recommendations of Grandfather Mas’) – did the Khmer script appear in print. On the other hand, between 1938 and 1972 over 1,000 novels were printed, ranging from detective and adventure tales to mysteries, historical novels and love stories. After independence, Cambodian literature was added to the national educational curriculum. With the establishment of the Khmer Writers’ Association in 1956, writers were recognised as making a cultural contribution in their own right and the institutionalisation of Khmer literature appeared complete. In today’s modern era, most Cambodian writers cannot live on the proceeds of their writing. In recent years, well-known writers have turned their hand to writing for television and video, where the rewards are more certain. However some formal encouragement for novels and other creative writing does exist.

https://vietlongtravel.com/news

“VIETNAM”

Vietnamese literature has been fed by two great tributaries: the indigenous oral literature and the written literature of Chinese influence. The oral poetry tradition is purely native. Vietnamese literature is literature, both oral and written, created largely by Vietnamese-speaking people, although Francophone Vietnamese and English-speaking Vietnamese authors in Australia and the United States are counted by many critics as part of the national tradition. The Vietnamese literary tradition has evolved through multiple events that have marked the country’s history. New literary movements can usually be observed every ten years but in the last century, Vietnamese literature underwent several literary transitions. The Vietnamese literature has been rich in folklore and proverbs; tales that have been handed down from generation to generation, gradually becoming valuable treasures. The folk literature grows during the processes of activity, labour, construction and struggle of the people. It is the soul and vital power of the nation. The bond between fighting men is a theme in all the literature about Vietnam. That devotion, the key to survival, becomes the reason for fighting.

https://dnqtravel.com/vietnam https://www.britannica.com/

“THAILAND”

Thai literature was heavily influenced by the Indian culture and Buddhist-Hindu ideology since the time it first appeared in the 13th century. Thailand's national epic is a version of the Ramayana called the Ramakien, translated from Sanskrit and rearranged into Siamese verses. Another major Thai literary figure was Sunthon Phu (1786-1855), a poetic genius and well-beloved commoner. Sunthon Phu’s enduring achievement (apart from his legendary personal adventures) was to write superbly well in common language about common feelings and the common folk. Easily understood by all classes, his work became widely accepted. His major works were Phra Aphai Mani, a romantic adventure, and nine Nirats mostly written during a pilgrimage, associating romantic memories with the places he visited in central and eastern Thailand. Moving into the modern age about 1900 onward, most of the Thai readers are well acquainted with the work of Dokmaisod whose real name is M.L. Boobpha Nimmanhaemindha. She was a novelist in the pioneering age. Her best-known works were for example, Phu Di, Nung Nai Roi, Nit, Chaichana Khong Luang Naruban, etc. Many of her works have been assigned as books for external reading for students at the secondary and tertiary levels of education today.

https://vietlongtravel.com/news/thailand-fact

“PHILIPPINES”

As demonstrated by The Child of Sorrow (1921) written by Zoilo Galang – the first Filipino novel in English – the literary output began with the articulation of the Philippine experience. The early writings in English were characterized by melodrama, unreal language, and unsubtle emphasis on local color. The Philippines is unique for having important works in many languages. The most politically important body of Philippine literature is that which was written in Spanish. The Propaganda movement, which included Jose Rizal agitated for independence in the 1880's and 1890's, writing exclusively in Spanish. Literatures in the Philippines has a lot of lessons that you can learn and apply to, for your daily livings. There are various Filipino writers and interpreters who define literature in their views as citizens of the Philippines. These included Jose Arrogante, Zeus Salazar, and Patrocinio V. Villafuerte, among others. Literacy is for all Filipinos. It is a kind of valuable remedy that helps people plan their own lives, to meet their problems, and to understand the spirit of human nature. A person’s riches may be lost or depleted, and even his patriotism, but not literature. One example is the advancement of other Filipinos. Although they left their homeland, literature was their bridge to their left country. The main themes of Philippine literature focus on the country's pre-colonial cultural traditions and the socio-political histories of its colonial and contemporary traditions. Some of the famous Philippine literatures are: Noli Me Tángere by Dr. José Rizal, Florante at Laura by Francisco Balagtas, Mga Ibong Mandaragit by Amado V. Hernandez, The Woman Who Had Two Navels by Nick Joaquin, Po-on A Novel by F. Sionil Jose, Banaag at Sikat by Lope K. Santos, Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco, Dekada '70 by Lualhati Bautista.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippine https://www.hisour.com/philippine

“LAOS”

Lao literature spans a wide range of genres including religious, philosophy, prose, epic or lyric poetry, histories, traditional law and customs, folklore, astrology, rituals, grammar and lexicography, dramas, romances, comedies, and non-fiction. Most works of Lao literature have been handed down through continuous copying and have survived in the form of palm-leaf manuscripts, which were traditionally stored in wooden caskets and kept in the libraries of Buddhist monasteries. The act of copying a book or text held deep religious significance as a meritorious act. The emphasis in writing was to convey Theravada Buddhist thought, although syncretism with animist beliefs is also common, religious and philosophical teachings. Individual authorship is not important; works were simply attributed with a perceived religious origin raising its status in the eyes of the audience. The Lao period of classical literature began during the Lan Xang era, and flourished during the early sixteenth century. The primary cultural influence on Lan Xang during this period was the closely related Tai Yuan Kingdom of Lanna.

The epic of Sin Xay was composed by the Lao poet Pangkham during the reign of King Sourigna Vongsa and is regarded as the seminal work of Lao epic poetry. The central message is one that unchecked desires will inevitably lead to suffering. The Thao Hung Thao Cheuang epic is regarded by literary critics and historians as one of the most important indigenous epic poems in Southeast Asia and a Lao language literary masterpiece for artistic, historical, and cultural reasons. The established authors such as Outhine Bounyavong, Dara Viravongs, Pakian Viravongs, Douangdeuane Viravongs and Seree Nilamay resumed their literary activities alongside revolutionary writers such as Phoumi Vongvichit, Souvanthone Bouphanouvong, Chanthy Deuansavanh, Khamlieng Phonsena and Theap Vongpakay. They have since been joined by a younger generation of writers. In the decade following the communists' victory in 1975, the major themes treated in literature were the virtues of the communist revolution and the great strides Lao society was taking under communist party leadership.

https://www.britannica.com/art/Lao-literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literature_of_Laos

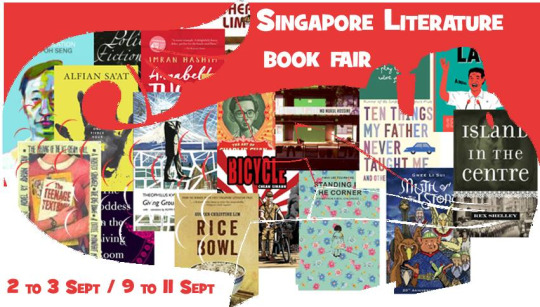

“SINGAPORE”

The literature of Singapore comprises a collection of literary works by Singaporeans. It is written chiefly in the country's four official languages: English, Malay, Standard Mandarin and Tamil. While Singaporean literary works may be considered as also belonging to the literature of their specific languages, the literature of Singapore is viewed as a distinct body of literature portraying various aspects of Singapore society and forms a significant part of the culture of Singapore. Literature in all four official languages has been translated and showcased in publications such as the literary journal Singa, that was published in the 1980s and 1990s with editors including Edwin Thumboo and Koh Buck Song, as well as in multilingual anthologies such as Rhythms: A Singaporean Millennial Anthology Of Poetry (2000), in which the poems were all translated three times each into the three languages. Since the nation-state sprang into being in 1965, Singapore literature in English has blossomed energetically, and yet there have been few books focusing on contextualizing and analyzing Singapore literature despite the increasing international attention garnered by Singaporean writers. This volume brings Anglophone Singapore literature to a wider global audience for the first time, embedding it more closely within literary developments worldwide. Singaporean writers are producing work informed by debates and trends in queer studies, feminism, multiculturalism and social justice work which urgently calls for scholarly engagement. The endeavour to establish this identity is echoed in the literature through the themes they raise.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singaporean https://www.lifestyleasia.com/sg/culture/art-design

The modern states of East Asia include China, Hong Kong, Japan, Macau, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. The East Asian states of China, North Korea, South Korea and Taiwan are all unrecognized by at least one other East Asian state due to severe ongoing political tensions in the region, specifically the division of Korea and the political status of Taiwan. Hong Kong and Macau, two small coastal quasi-dependent territories located in the south of China, are officially highly autonomous but are under de jure Chinese sovereignty. China, Korea, and Japan, however, have been uniquely linked for several millennia by a common written language and by broad cultural and political connections that have ranged in spirit from the uncritically adorational to the contentious.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki

“CHINA”

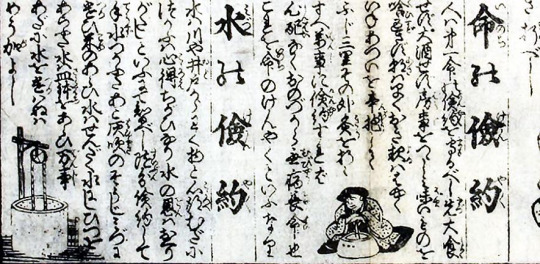

Chinese literary works include fiction, philosophical and religious works, poetry, and scientific writings. The dynastic eras frame the history of Chinese literature and are examined one by one. The grammar of the written Classical Language is different than the spoken languages of the past two thousand years. The most important of these philosophical writings, as far as Chinese culture are concerned, are the texts known as The Five Classics and The Four Books. Chinese poetry, besides depending on end rhyme and tonal metre for its cadence, is characterized by its compactness and brevity. There are no epics of either folk or literary variety and hardly any narrative or descriptive poems that are long by the standards of world literature. Chinese poetry, besides depending on end rhyme and tonal metre for its cadence, is characterized by its compactness and brevity. Not only was the Chinese script adopted for the written language in these countries, but some writers adopted the Chinese language as their chief literary medium, at least before the 20th century. On the other hand, the line of demarcation between prose and poetry is much less distinctly drawn in Chinese literature than in other national literatures. Chinese literary works include fiction, philosophical and religious works, poetry, and scientific writings. The dynastic eras frame the history of Chinese literature and are examined one by one. The grammar of the written Classical Language is different than the spoken languages of the past two thousand years. Water Margin, Journey to the West, Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Dream of the Red Chamber; these four novels form the core of Chinese classical literature and still inform modern culture.

https://www.britannica.com/

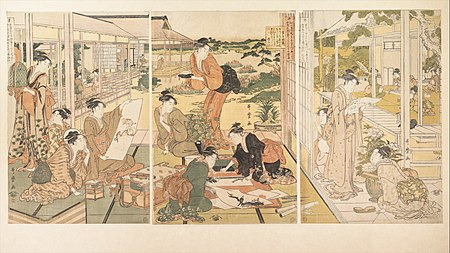

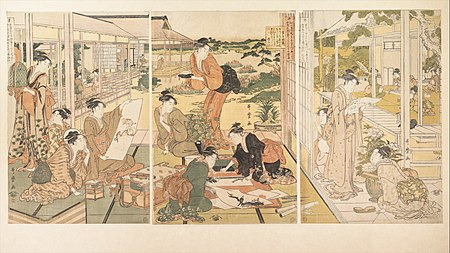

“JAPAN”

Japanese literature Earliest extant works are the Kojiki (712) and the Nihongi (720), which are histories written in Chinese characters used phonetically. The earliest recorded Japanese poetry is in the Manyoshu (760), which contains poems dating to the 4th century. Japanese literature has a long and illustrious history, with its most famous classic, The Tale of Genji, dating back to the 11th century. Often dark but full of humor, Japanese literature showcases the idiosyncrasies of such a culturally driven nation. Japanese literature expresses multiple components of Japanese people. It expresses their gratitude towards traditions and their sympathy towards nature. However, Japanese literature was not known outside of Japan until the 1900's.

Early works of Japanese literature were heavily influenced by cultural contact with China and Chinese literature, and were often written in Classical Chinese. Indian literature also had an influence through the spread of Buddhism in Japan. Eventually, Japanese literature developed into a separate style, although the influence of Chinese literature and Classical Chinese remained. Following Japan's reopening of its ports to Western trading and diplomacy in the 19th century, Western literature has influenced the development of modern Japanese writers, while they have in turn been more recognized outside Japan, with two Nobel Prizes so far, as of 2020. In translation many of the biggest and best names in Japanese literature are women, and these women are breaking boundaries and smashing literary traditions by tackling themes like societal structures and patriarchy, loss and isolation, and non-romantic love.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese

“KOREA”

Korean literature is the body of literature produced by Koreans, mostly in the Korean language and sometimes in Classical Chinese. For much of Korea's 1,500 years of literary history, it was written in Hanja. It is commonly divided into classical and modern periods, although this distinction is sometimes unclear. The stories are generally didactic, emphasizing correct moral conduct, and almost always have happy endings. Another general characteristic is that the narratives written by yangban authors are set in China, whereas those written by commoners are set in Korea. The Department of Korean Language and Literature aims at the creative inheritance and development of Korean culture through the study of Korean language and literature. There are four major traditional poetic forms: hyangga (“native songs”); pyŏlgok (“special songs”), or changga (“long poems”); sijo (“current melodies”); and kasa (“verses”). Other poetic forms that flourished briefly include the kyŏnggi style in the 14th and 15th centuries and the akchang (“words for songs”) in the 15th century. Korean poetry originally was meant to be sung, and its forms and styles reflect its melodic origins. The basis of its prosody is a line of alternating groups of three or four syllables, probably the most natural rhythm to the language. Korean prose literature can be divided into narratives, fiction, and literary miscellany. Narratives include myths, legends, and folktales found in the written records. The principal sources of these narratives are the two great historical records compiled during the Koryŏ dynasty: Samguk sagi (1146; “Historical Record of the Three Kingdoms”) and Samguk yusa (1285; “Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms”). On the other hand, oral literature includes all texts that were orally transmitted from generation to generation until the invention of Hangul—ballads, legends, mask plays, puppet-show texts, and p’ansori (“story-singing”) texts. The origins of Korean literature can be traced back to an Old Stone Age art form that combined dance, music, and literature. Most Korean literature has the theme: Loyalty, Order, Relationships, Fear of alienation, and Fear of separation.

https://www.britannica.com/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Korean http://www.asianinfo.org/

“MONGOLIA”

Mongol literature has been greatly influenced by its nomadic oral traditions. The "three peaks" of Mongol literature, The Secret History of the Mongols, Epic of King Gesar and Epic of Jangar, all reflect the age-long tradition of heroic epics on the Eurasian Steppe. Mongolian literature, the written works produced in any of the Mongolian languages of present-day Mongolia; the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region of China; the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang, China; and the Russian republics of Buryatiya and Kalmykiya. Written Mongolian literature emerged in the 13th century from oral traditions, and it developed under Indo-Tibetan, Turkic, and Chinese influence. The 20th century saw the publication of many new literary works in Mongolia as well as in Buryatiya and Kalmykia in Russia and in China’s Inner Mongolia and Dzungaria (in Xinjiang) regions. Until the middle of the 20th century, the Mongols and Buryats used Mongol script to write a language known as Classical, or Literary, Mongolian. The most significant work of pre-Buddhist Mongolian literature is the anonymous Mongqolun niuča tobča'an (Secret History of the Mongols), a chronicle of the deeds of the Mongol ruler Chinggis Khan (Genghis Khan) and of Ögödei, his son and successor.

https://www.britannica.com/art/Mongolian-literature https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mongolian_literature

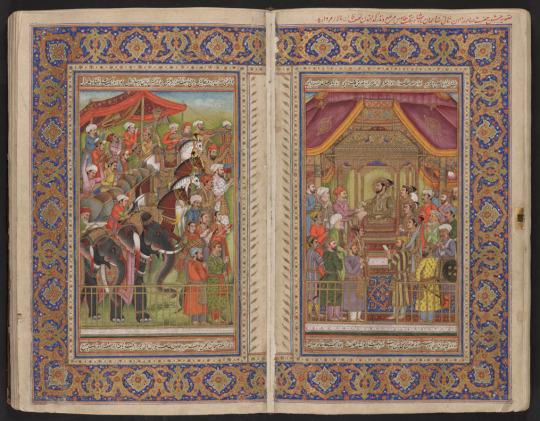

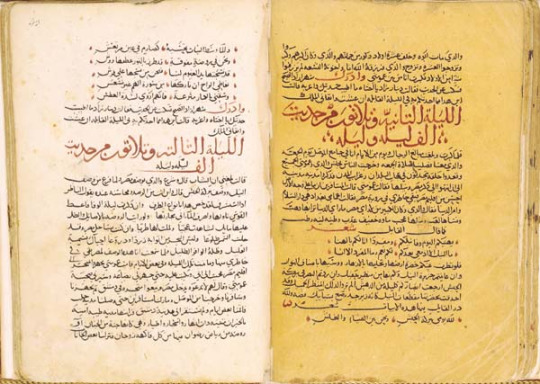

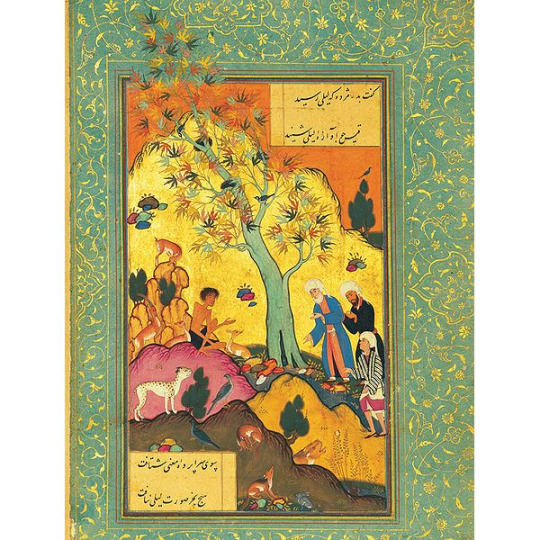

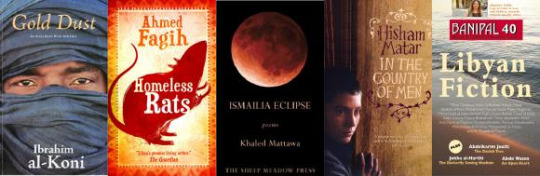

Twenty-first-century Middle Eastern (primarily Arabic, Persian, and Turkish) literature encompasses a rich variety of genres, whose maturation has profited from internal and external influences upon this literature over the past fourteen centuries. Middle Eastern Literatures, was launched in 1998 by former editorial board members of Journal of Arabic Literature. After considering the current state of research in the field, the Editors have decided a new forum for publication and discussion is required. Middle Eastern Literatures vigorously promotes the academic study of all Middle Eastern literatures. Work on literature composed in, for example, Persian, Turkish, post-Biblical and Modern Hebrew, Berber, Kurdish or Urdu language is welcomed.

“IRAN”

Iranian literature, body of writings in the Iranian languages produced in an area encompassing eastern Anatolia, Iran, and parts of western Central Asia as well as Afghanistan and the western areas of Pakistan. Literature in Iran encompasses a variety of literary traditions in the various languages used in Iran. Modern literatures of Iran include Persian literature (in Persian, the country's primary language), Azerbaijani literature (in Azerbaijani, the country's second largely spoken language), and Kurdish literature (in Kurdish, the country's third largely spoken language), among others. Iran's earliest surviving literary traditions are that of Avestan, the Iranic sacred language of the Avesta whose earliest literature is attested from the 6th century BC and is still preserved by the country's Zoroastrian communities in the observation of their religious rituals, and that of Persian. Persian literature differs from the common definition of “literature” in that it is not confined to lyrical compositions, to poetry or imaginative prose, because the central elements of these appear, to greater or lesser degrees, in all the written works of the Persians.

https://www.ancient.eu/Persian_Literature/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Literature_in_Iran

“SAUDI ARABIA”