#koine greek

Text

Odysseus, the lord of lies

Okay, I’ve been reading Emily Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey, and for a million and one reasons I would recommend it.* But my favorite reason, by far, is that she decides to call Odysseus “the lord of lies” as one of his epithets. Of course, it’s not a word for word translation of the original epithet, because that can be hard to pin down, but I think it so interestingly and comically describes Odysseus. So yeah. That’s all.

*She writes it in IAMBIC PENTAMETER?! Do you know how hard it is to write in iambic pentameter? Do you know how hard it is to translate a work like the Odyssey? DO YOU KNOW HOW HARD IT IS TO TRANSLATE A WORK LIKE THE ODYSSEY INTO IAMBIC PENTAMETER?!?! All this work, she does, to preserve the common rhythm that listeners would’ve felt. God bless Emily fucking Wilson.

#classics#classicist#ancient greece#ancient greek#koine greek#the odyssey#odysseus#literature#litblr#ancient literature#greek literature#emily wilson#the iliad#epic poetry#homeric epics#Homeric greek#attic greek

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The New Testament in the original Greek is not a work of literary art : it is not written in a solemn, ecclesiastical language, it is written in the sort of Greek which was spoken over the Eastern Mediterranean after Greek had become an international language and therefore lost its real beauty and subtlety.

In it we see Greek used by people who have no real feeling for Greek words because Greek words are not the words they spoke when they were children. It is a sort of “basic” Greek; a language without roots in the soil, a utilitarian, commercial and administrative language. Does this shock us? It ought not to, except as the Incarnation itself ought to shock us.

The same divine humility which decreed that God should become a baby at a peasant-woman’s breast, and later an arrested field-preacher in the hands of the Roman police, decreed also that He should be preached in a vulgar, prosaic and unliterary language. If you can stomach the one, you can stomach the other.

The Incarnation is in that sense an irreverent doctrine: Christianity, in that sense, an incurably irreverent religion. When we expect that it should have come before the World in all the beauty that we now feel in the Authorised Version we are as wide of the mark as the Jews were in expecting that the Messiah would come as a great earthly King.

The real sanctity, the real beauty and sublimity of the New Testament (as of Christ’s life) are of a different sort: miles deeper or further in.”

—

CS Lewis, intro to JB Phillip’s translation of the New Testament letters, 𝘓𝘦𝘵𝘵𝘦𝘳𝘴 𝘵𝘰 𝘠𝘰𝘶𝘯𝘨 𝘊𝘩𝘶𝘳𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘴, 1947

#CS Lewis#new testament#jb Phillips#christianity#ancient texts#koine Greek#Greek language#first century ad#ancient manuscripts#messiah#the Christ#vulgar

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I love learning dead languages because I can’t ask you how you’re doing in Koine Greek but I can talk about slavery and gifts from God

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submission:

Γεία σας, ο θεία μου! Ο Ελληνικά μου δεν είναι καλο, επομένος λεω συγνώμη.

Στα αγγλικα: Are there resources for studying Koine Greek (and maybe the Bible) with Greek culture in mind? The internet feels saturated with English people making a fuss out of Greek terms, and instances like the "four types of love" have made me skeptical of people making theology out of a language they don't understand.

(One time, while reading in church, I heard this guy who explained that φιλεω was for sentimental love while αγαπάω was not love but care)

Also, how can I improve my study of modern Greek, beyond Duolingo?

Love,

ένας ξένος

=============

Γεια σου 💖💖 Χαίρομαι που μαθαίνεις Ελληνικά! Μπράβο σου!! For future reference and for your own knowledge I think it's worth saying that it would be more correct to write "Γεια σου, ω, θεία μου!" ;) Ω/ω is used for calling someone, usually in an archaic style. When you're using the archaic style you don't use the politeness plural (hence it is γεια σου, and not γεια σας) And especially since you're using the endearing "μου" you don't have to use any politeness plural. In a religious context Greeks always addressed their gods or Abrahamic god in the singular. "Ω, Ζευ, βοήθη μι" or "Θεέ μου, σώσον με".

I think the best source for studying the Koine Greek with Greek culture in mind would be the theological Greek Orthodox studies. The most known text in Koine Greek is the New Testament after all.

You can see what various Greek Orthodox videos and blogs say about New Testament passages. Indeed both φιλέω/-ώ and αγαπάω/-ώ denote some type of "love" but as you said in the ancient context the first had a more sentimental tint to it while the second had also the element of care. However it doesn't mean that with φιλέω you couldn't show care, or that with αγαπώ you couldn't show sentimentality. There's of course the ancient phrase "αγαπάτε αλλήλους (ως εαυτόν)" which tell us to care about and love each other (like we do for ourselves). Also there are other Greek verbs to more exclusively show "care". (In the way of "I care for the well-being of a baby")

For more resources apart from Duolingo, you can check my tag #learn Greek where you can find many organizations and channels that will help you in your journey!

Let me know if I can help more :)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

12.11.2022 = Ancient Greek is difficult. Very difficult. And yet I’m doing very well in this course, and will likely walk away with at least a B+ ... so I guess I can chill out a bit with this final!

My third semester of college ends in less than a week. I’m in awe of even getting here, and very proud of myself for how far I’ve come :)

#studyblr#langblr#aesthetic#studyspo#study with me#ancient greek#attic greek#koine greek#dark academia#light academia#grey academia#study aesthetic#college#university#college student#college life#university student#college studyspo

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Since I did a lot of pronunciation talk yesterday, I did a little research and I found a very fresh (2020!) yet very reasonable approach on Ancient Koine Greek. Its creators call it Lucian pronunciation and suggest it is used for even earlier eras without concern. I found myself agreeing a lot on their mindset approaching the challenge: they tried to unite all those elements from all prevalent pronunciations (Modern, Reconstructed, Restored Koine, Erasmian) that can create a functional and aesthetically pleasing result that distances itself neither from the pronunciation modern natives are accustomed to nor from some very popular western approaches that have been established as generally accurate.

I believe they succeed for the most part. Most comments seem to agree, although there are of course the occasional “there’s nothing except eternal Modern” Greeks and the occasional “Whoever says something opposite to Erasmus must be executed” westerners. You can check for yourselves though. I believe they make sense. I am adding the video and also the explanatory text, which is very helpful, in the link below.

youtube

Of course I think this checks post-classical. For anything before 4th-5th century BC, I guess Reconstructed might still be closer to the truth but also harder to bring to life accurately... However, the creators of Lucian say you can use it with any era (even Homeric) in the sense that it is the most wholistic approach and that you can never be perfectly accurate anyway.

Tagging some people who might be interested: @alatismeni-theitsa, @tattered-cynic and @desertdwellingforestcreature.

#greek#polymathy#greek language#koine greek#langblr#linguistics#languages#ancient greek#pronunciation#greek facts#Youtube

64 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studying right now, and idk if this is an unpopular opinion, but I think we should just banish all the -μι verbs to the Bogs of the Hinterlands. We don't need them. Observe:

δίδωμι? I don't give things to people.

ἵστημι? I hate standing.

τίθημι? Imagine picking up an object just to set it back down. Couldn't be me.

φημί? Just don't talk, bro.

εἰμί? Whoever said being verbs were necessary? Just don't be, and we won't need being verbs. Simple.

#why are they so irregular#why can't they just make sense#7 years of this shit and I still have to check almost every time#what kind of psychopath sees both φημὶ and λέγω meaning the same thing and chooses to use φημί#also yes that is a fairytopia reference bite me#ancient greek#attic greek#homeric greek#koine greek#classical studies#classics stuff#local queer classicist posts

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

αὕτη ἐστὶν ἡ ἐντολὴ ἡ ἐμή, ἵνα ἀγαπᾶτε ἀλλήλους καθὼς ἠγάπησα ὑμᾶς:

John 15: 12.

Translation:

This is the command of me, that you love one another as I loved you. (Literal).

My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you. (NIV).

This is my commandment, That ye love one another, as I have loved you. (KJV).

#Bible#Koine#Koine greek#scripture#new testament#bible verse#St John the Apostle#Gospel of John#Jesus

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

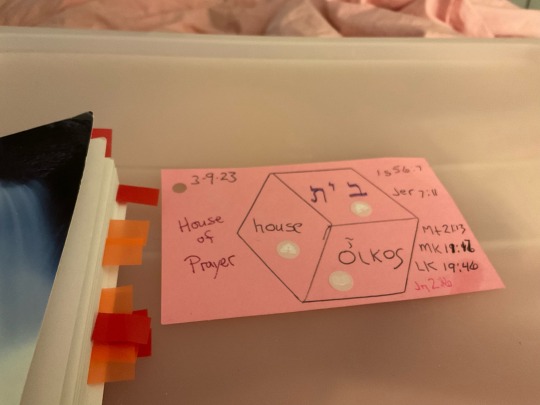

Theology Thursday: Mark 11:17

Jesus is famous for his parables. In the last week of his life on earth, Jesus dramatically clears the temple of money changers. As recorded in Mark 11:17 he says, “ Is it not written: ‘My house will be called a house of prayer for all nations’? But you have made it ‘a den of robbers.’” He is quoting two different OT verses, Isaiah 56:7 and Jeremiah 7:11. Both are quoted nearly verbatim from the Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible) although in this case, the Greek translation is a literal translation of the Hebrew. Both verses should have been familiar to anyone who witnessed the scene.

So, was Jesus just throwing a tantrum, in contrast to his mild manner throughout the rest of his ministry? That could mean it’s ok for us to follow his example since we know nothing Jesus does is a sin. Or is this a special case and there is more to it? Some say this is Jesus acting out a parable. The location of the event was the court of the gentiles at the Temple. Evidently the elitism of the Jews had prompted them to edge the gentiles out of the court designated for them and filled it with tables of money changers. Jesus is making it obvious that it is unacceptable to violate God’s clear instructions for his house to be a house of prayer for all nations, not just his chosen people, the Jews. The scene must be important because it’s recorded in all four gospels. Jesus loves us and shows it in many ways, not just by giving his life for us.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doxology or Ancient Greek is the language of hymns, psalms, and canticles. It is an expression of praise to God. By learning this language, you can feel more connected to God and gain a better understanding of the Bible. Among the various options available to learn Doxology, the best one is to join Koine Greek online courseby Greek to Me. It is a comprehensive course designed by experts using a mnemonic approach. Doxology holds great significance in Christianity. If you want to explore the historic significance of Christianity, join an online course and learn Ancient Greek.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

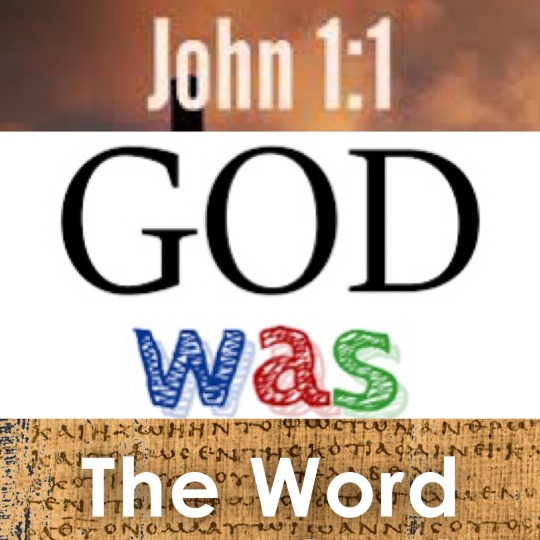

How Should We Translate John 1.1: “the Word was God,” or “God was the Word”?

By (native Greek speaker) Eli Kittim 🎓

John 1.1:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς

τὸν θεόν, καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος.

John 1.1 is often broken down into 3 phrases:

Phrase 1: Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος

Phrase 2: καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν

Phrase 3: καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος.

From the outset, before they even consider the process of biblical interpretation and exegesis, textual critics and Greek scholars set out to produce a faithful *translation* of the original Greek New Testament. Bear in mind that the processes of translation and interpretation are not the same. We expect the translation committees to translate (not to interpret) the text!

Therefore, a literal and accurate translation of the Greek language should correctly translate the last phrase of Jn 1.1 as “God was the word.” In other words, the third phrase of Jn 1.1 (καὶ θεὸς ἦν ὁ λόγος) should be translated exactly as it was written in the original Greek (for emphasis), not rearranged and reassembled (in the target language) as we would wish it would be. In the original Greek, the text doesn’t actually say that “the Word was God,” as most modern translations maintain:

That’s an interpretation!

Rather, the original Greek New Testament says that “God was the Word”! So, the *interpretative* rearrangement is forcing the critical reader to read it backwards, which neglects the emphasis of the word order in the original Greek. It’s as if we were told to read Hebrew backwards, from left to right. What is more, the third phrase of John 1.1 doesn’t actually say ὁ λόγος ἦν (the word was). It says θεὸς ἦν (God was). If the text wanted to emphasize that “the word was God,” the phrase would have been: καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν θεὸς. It would have been written as follows:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς

τὸν θεόν, καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν θεὸς.

But that’s not what it says! To try to manipulate what the original Greek New Testament is actually emphasizing——by rearranging or *reinterpreting* it during the translation process——is equivalent to editing and, therefore, corrupting the “inspired” text.

Admittedly, the third phrase of Jn 1.1 is somewhat of a Gestalt configuration in which different *meanings* can arise depending on the angle from which it is viewed. One could make the *interpretative* argument that the original phrase “God was the Word” might be equivalent to or interchangeable with “the Word was God.” In other words, on an *exegetical* level, one could make the case that the phrase “the Word was God” might be the converse of “God was the Word.” I don’t deny that possibility on grammatical grounds. That is certainly worthy of exegetical consideration. But when we’re initially *translating* the text, we shouldn’t be interested in theories of exegesis. Rather, we should be entirely focused on producing a faithful translation, which precedes interpretation and subsequent theological ramifications.

In *interpreting* the third phrase of Jn 1.1, many textual scholars typically reverse the word-order of the original Greek phrase (via a grammatical rule) so that we’re forced to read the words backwards. According to this rule, we can determine the *subject* of a phrase if a noun falls into one of the following categories: a) if it’s a proper name; b) if it’s preceded by an article; or c) if it’s a personal pronoun. However, in contradistinction to this grammatical rule, θεὸς can actually be the subject that precedes the verb ἦν (here, a form of "to be"), while λόγος can be the predicate nominative. On the other hand, in order to identify θεὸς as the predicate nominative and λόγος as the subject, one has to invoke what is known as the “Subset Proposition" rule, or the "Convertible Proposition" rule. In other words, this alteration involves a complex set of esoteric grammatical assumptions and decisions which essentially turn the text upside down.

By contrast, the straightforward way of reading the text seems to be the smoothest and the most natural. Not to mention that the phrase “God was the Word” is actually a faithful translation, whereas the phrase “the Word was God” is merely an *interpretation.* I’m not arguing that the phrase “the Word was God” is a wrong interpretation. I’m arguing that it’s a wrong translation! In the critical edition, we must always let the reader know what the text ACTUALLY says, not our INTERPRETATION of what we think it might mean. That can go in the commentary section. In translating a text——if the word-order of the original Greek doesn’t make any sense——translators are allowed to rearrange the words in order for it to make sense. But this exception to the rule doesn’t apply here because the original Greek makes perfect sense! Therefore, our decision to abandon our fidelity to the lexical details and grammatical structures of the Greek New Testament makes us no better than the scribes who corrupted it.

Moreover, the decision to change the *meaning* of the text (or to *reinterpret* it) is done for obvious theological reasons. Christian translators have a theological axe to grind. In order to validate and uphold the Trinity, they want to maintain the *distinction* between God the Father (the first person of the Trinity) and the Word of God (the second person of the Trinity). Hence why they deliberately *translate* the last part of Jn 1.1 backwards. Because if they were to translate it as the author intended it, namely, that “God was the word,” it might give the wrong impression that there’s no distinction between the Father and the Word. However, the third phrase of Jn 1.1 is not necessarily making a *modalistic* theological claim that there’s no distinction between the Father and the Word. Rather, since the second phrase (καὶ ὁ λόγος ἦν πρὸς τὸν θεόν) clearly distinguished the two persons of the Trinity, the third phrase establishes their *ontological* unity by affirming that God was not simply separate from the Word, but that God himself was, in fact, the Word per se! After all, the first and second persons of the Trinity share one homoousion (essence): “I and the Father are one” (Jn 10.30)!

At any rate, this *interpretation* has become so wide spread, to such an extent that it has become a dogmatic and systematic standard, not only overriding or supplanting the original *translation* but also prompting modern translations to follow suit. It’s a case of special pleading where an *interpretation* has supplanted a *translation*!

However, there are many credible Bible translations that *translate* the last phrase of Jn 1.1 as “God was the Word”:

Coverdale Bible of 1535

In the begynnynge was the worde, and the

worde was with God, and God was ye

worde.

Smith's Literal Translation

In the beginning was the Word, and the

Word was with God, and God was the Word.

Literal Emphasis Translation

In the beginning was the Word, and the

Word was with God, and God was the Word.

Catholic Public Domain Version

In the beginning was the Word, and the

Word was with God, and God was the Word.

Lamsa Bible

THE Word was in the beginning, and that

very Word was with God, and God was that

Word.

Aramaic New Covenant: In the beginning

the Word having been and the Word having

been unto God and God having been the

Word.

Concordant Literal New Testament: In the

beginning was the word, and the word was

toward God, and God was the word.

Coptic Version of the New Testament: In

(the) beginning was the Word, and the Word

was with God, and God was the Word.

Great Bible (Cranmer 1539): In the

begynnynge was the worde, and the worde

was wyth God: and God was the worde.

New English Bible: When all things began,

the Word already was. The Word dwelt with

God, and what God was, the Word was.

Revised English Bible: In the beginning the

Word already was. The Word was in God’s

presence, and what God was, the Word

was.

Today’s English New Testament: In the

beginning was the Logos. And the Logos

was with God. And God was the Logos.

The Wyclif Translation (by John Wycliffe): In

the bigynnynge was the word and the word

was at god, and god was the word.

Latin Vulgate: in principio erat Verbum et

Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat

Verbum.

Vulgate translation: in the beginning was

the Word and the Word was with God and

God was the Word.

See also:

Was the Word “God” or “a god” in John 1.1?

#greektranslations#Greek linguistics#GreekPhilology#Βιβλικήμελέτη#John1v1#theWordwasGod#GodwastheWord#θεὸςἦνὁλόγος#biblicalinterpretation#ελικιτίμ#ModalisticMonarchianism#trinity#biblicalgreekgrammar#koine greek#το_μικρο_βιβλίο_της_αποκάλυψης#εκ#GreekNewTestament#ek#Bibletranslations#Bibleversions#the little book of revelation#elikittim#homoousion#john10v30#biblestudy#authorialintention#biblicalexegesis#ontologicalunity#textual criticism#theologicalbias

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bart Ehrman is gonna get a time machine one of these days only to find out epiousion was the first century version of shagadelic or bussin'

1 note

·

View note

Text

"are you trying to learn ancient greek Menw?"

"...yeah..."

"oh neat! is it to learn some stuff about greek polytheism? maybe to connect with people on the internet?"

"about that..."

"it's to read more early christian writings isn't it?"

*holding bundles of texts by Origen and Clement*

"οὔ"

1 note

·

View note

Text

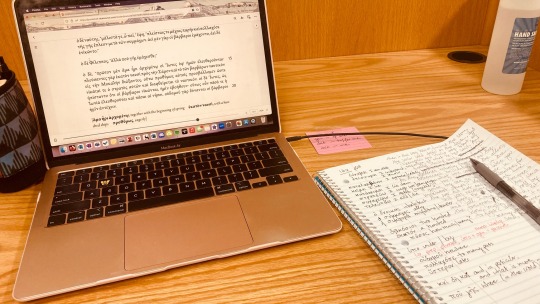

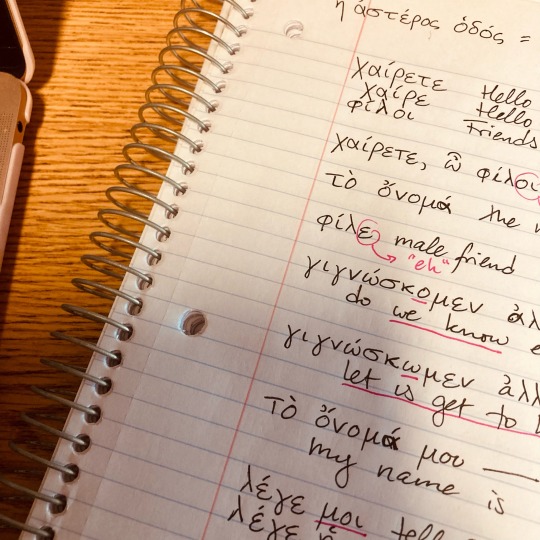

09.03.2022 = getting started on Greek and rescuing more bamboo from Walmart

#college#religious studies#rels#studyblr#studyspo#university#college student#original post#school#aesthetic#dark academia#images#notetaking#reading#religious studies major#studying#Greek#koine Greek#koine#langblr#language learning

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

How comprehensible is New Testament Greek to modern Greek people?

Very, almost entirely. My impression is that: a) People of a generally good education (not lingual, just generally high school - college education) can understand 91-99% of it without problem. b) People of a basic education (elementary - middle school) can still make about 80-90% of it. c) For people taking lingual studies it is a stroll in the park, needless to say.

Still, Greek bibles always come with a modern translation too but it is mostly useful for “confirmation” rather than interpretation, as in, double-checking to ensure you understood correctly if you need.

A little known fact to foreign people is that Koine / Biblical Greek is lingually closer to Modern rather than Ancient Greek.

#Greek#Greek language#languages#linguistics#langblr#Koine Greek#biblical Greek#bible#New Testament#Christianity#Greek facts#emmenai-kalliston#ask

39 notes

·

View notes