#the vampire by william polidori

Text

I am of the idea that all vampire characters are queer until proven otherwise.

#no tengo pruebas pero tampoco dudas#i have no evidence and neither doubts#vampire#vampires#vampire media#vampires in literature#vampires in movies#vampires in tv#the vampire diaries#the originals#carmilla#castlevania#interview with the vampire#dracula#the vampire by william polidori#true blood#die vampirschwestern#first kill#my babysitter's a vampire#what we do in the shadows#nosferatu#adventure time#lilyrambles

185 notes

·

View notes

Text

pretty iconic that on one stormy night a bunch of dark academia gays gave the world not just frankenstein but also the broody vampire as we know it

#lord byron is connected to stephanie meyer is connected to 9/11 is connected to gerard way is connected to 50 shades#this is canon#you can achieve anything you set your mind to#geneva squad#lord byron#john william polidori#the vampyre#frankenstein#mary shelley#percy shelley#claire clairmont#dark academia#vampires#classic literature#twilight

56 notes

·

View notes

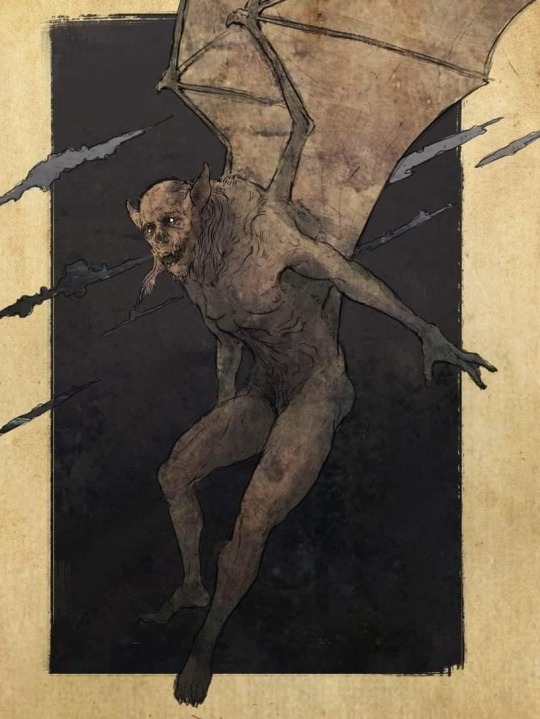

Photo

Spooky Staff Pick of the Week: The Vampyre

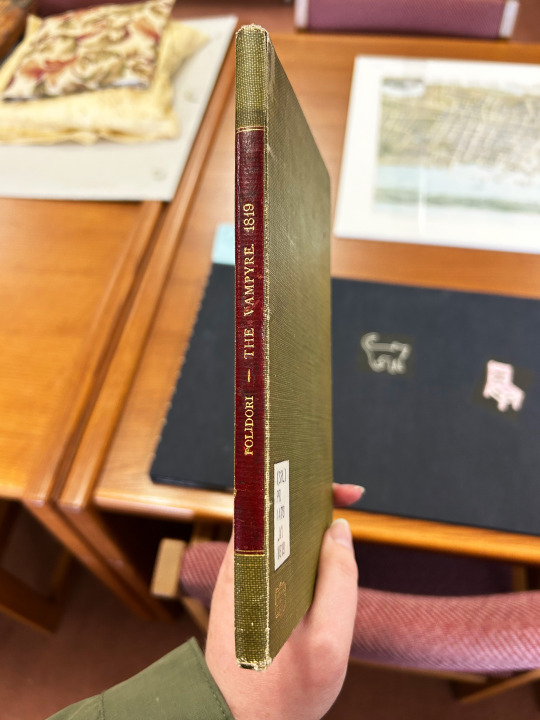

Because Halloween is coming up, I decided to pick something spooky for my staff pick this week! I chose this first edition copy of the original modern vampire story, The Vampyre, by John Polidori (1795-1821). Although the binding is not original (there is a note on the front cover from the Harvard College Library that it was bound on July 12, 1904), it is indeed a first edition, published in 1819 by Sherwood, Neely, and Jones in Paternoster Row, London.

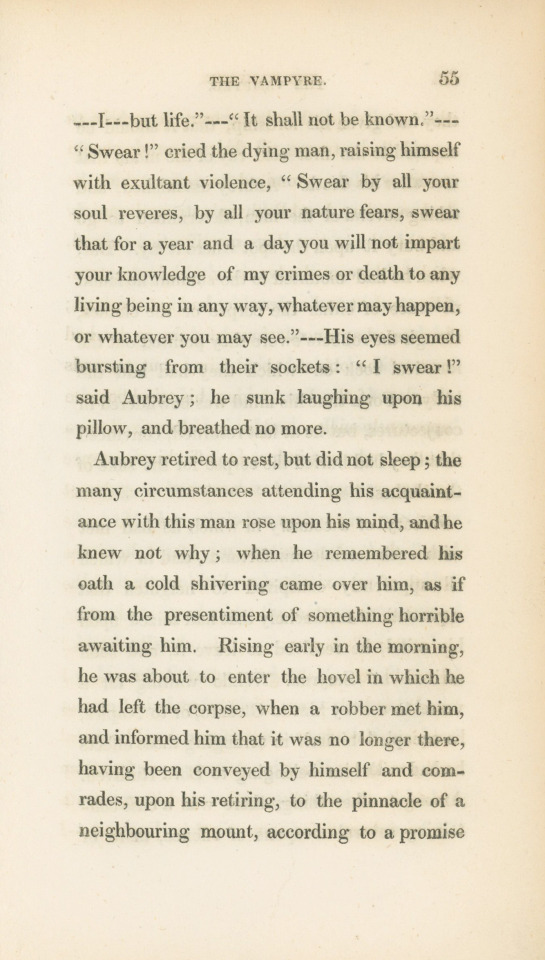

It follows the story of Aubrey, a wealthy young English gentleman who becomes acquainted with the mysterious Lord Ruthven. They set out to travel together to Greece, where Aubrey meets the beautiful Ianthe, who warns him of the evil vampyre and tells him that if he does not believe the tale he will surely have some evidence of this evil creature befall him. During a storm, Aubrey encounters the vampyre in a hovel where Ianthe is found dead, with her throat opened. Afterward, Ruthven and Aubrey leave Greece and on their travels are ambushed by robbers and Ruthven is mortally wounded. Before he dies, Ruthven makes Aubrey swear that he will not speak of his death for a year and a day, then dies with an evil cackle. Can you guess who the vampire is? Hint: It ain’t Aubrey.

Ruthven’s body disappears the following morning and Aubrey decides to return to England and his sister, who is oddly only called “Miss Aubrey.” Shortly thereafter, Miss Aubrey is introduced to society and who should appear but Lord Ruthven! Only now he goes by the name Earl of Marsden. He reminds Aubrey to keep his oath, and Aubrey subsequently has a nervous breakdown because he now knows for sure that Ruthven/Marsden is... THE VAMPYRE!

While Aubrey is having his nervous breakdown for literally the next year, his sister is being seduced by none other than the “Earl of Marsden.” Aubrey snaps out of his misery only to find out that his sister is to be married to Marsden on the exact day his oath is to end. He writes a letter to his sister warning her of the danger she is in, and dies. The letter is never delivered, and Miss Aubrey is found dead on her wedding night with her throat ripped open and Marsden long gone into the night.

The story was written after a fragment by Lord Byron—in which a man seemingly dies and then comes back to life—for the same scary story contest that prompted Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein. John Polidori, who was 21 at the time, was Lord Byron’s personal physician during some of his travels and joined Byron, Percy Shelley, Mary Godwin (not-yet-Shelley), and Mary’s stepsister Claire Clairmont at Villa Diodati on Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. When The Vampyre was initially published in 1819 without Polidori’s permission, it was credited to Lord Byron, who denied having written it, and attributed it to Polidori. It is perhaps the case that Lord Byron was unhappy with Polidori’s portrayal of Ruthven, whose name was taken from the satirical novel Glenarvon by Lady Caroline Lamb in which Ruthven is based on Lord Byron, who was Lady Lamb’s ex-lover. Eventually Polidori’s authorship was established and his name added to subsequent editions. Polidori died of “natural causes” in 1821 at the age of 25 in a state of depression due to various things including large gambling debts.

View more Staff Picks.

View more Halloween posts.

-- Alice, Special Collections Department Manager

#The Vampyre#John Polidori#Lord Ruthven#Vampires#Lord Byron#Mary Shelley#John William Polidori#spooky#scary#horror#scary stories#Halloween#Lady Caroline Lamb#Glenarvon

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

When you have finished reading "The Vampyre" tale by G. G. Byron, (J.W. Polidori) press the "back" button...

#the vampyre#short story#george gordon byron#john william polidori#picsart#collage art#vampire aesthetic#vampire art#dark and moody#dark aesthetic#gothic aristocrat#goth art#dark literature#творю и вытворяю

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

one thing that's really funny about interview with the vampire becoming pretty popular again is that I keep seeing people who've either only seen adaptations or only read the first book calling the gay part 'subtext'...girl in the next book lestat talks pretty plainly about how he was in love with louis. like romantically. he also had a boyfriend called nicolas in that book and they kiss on the lips and everything. in the third book the interviewer guy (whose name is daniel) gets with armand and they have weird vampire gay sex and everything. anne rice literally said that part of the lore for her books is that the vampirification process also makes you bisexual. I'm not fucking kidding. it was a lot of things but subtextual was not one of them

#it's so funny to me like I think she said it pretty plainly???#the only thing subtextual about iwtv was the 1994 movie where they tried to not make it obvious that it was gay#and even so it's pretty fuckin hard to make the story not be about brad pitt and tom cruise of all people being gay vampire married#the anne rice quote where she says that was so funny as well btw she's literally like#'vampires are inherently gay. this is because lord byron and john william polidori (who wrote 'the vampyre') definitely fucked'#say what you will about her but it has to be said. she was so right for that#sapphire's random thoughts#interview with the vampire#the vampire chronicles

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lord Ruthven, the Unbeaten Vampire Bastard Who Spread Misery and Murder Long Before Dracula Ever Left the Castle

A while ago I talked about my favorite underappreciated vampire babe, Clarimonde, who is well overdue for a modern day debut. But now I want to shed a little light on a gentleman of wealth and bad taste that some vampire lit fans may have come across while deep-diving through the old stories. Specifically, the grandaddy of all psychologically torturous, enigmatic, undiluted evil undead villains, Lord Ruthven.

Ruthven is the masterfully malevolent antagonist of John William Polidori’s short story, “The Vampyre,” published in 1819. He technically had his pre-publishing literary birthday in the same period as Mary Shelley’s, Frankenstein, as he was a product of the infamous challenge made by Lord Byron in the Villa Diodati to pass the time, urging his scribbling companions to write the scariest story they could. That was back in the summer of 1816, so hey, happy birthday to you, you old Nosferasshole!

Now, who is Lord Ruthven?

Spoilers for, “The Vampyre,” below

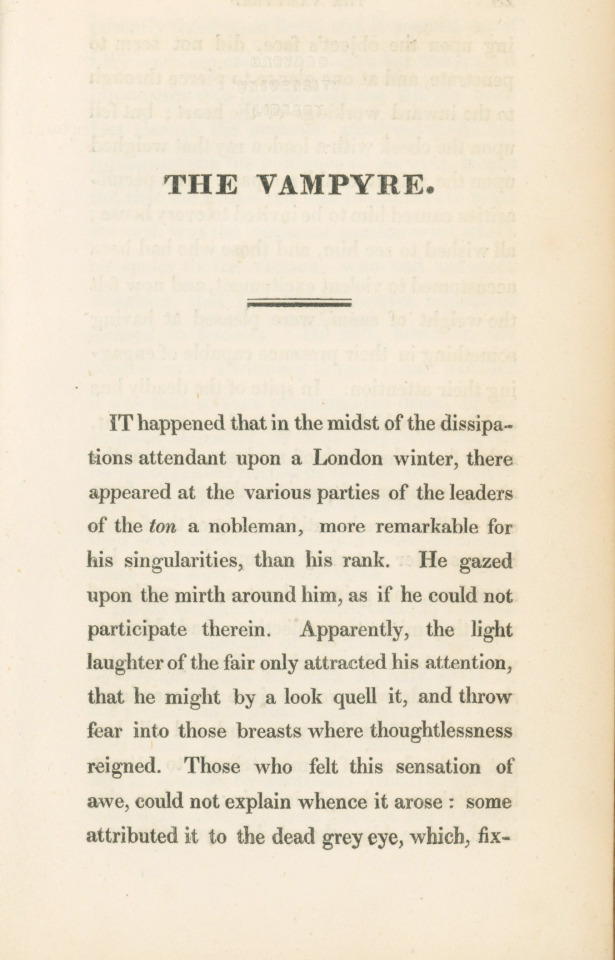

We’re introduced to him on the very first page like so:

It happened that in the midst of the dissipations attendant upon a London winter, there appeared at the various parties of the leaders of the ton a nobleman, more remarkable for his singularities, than his rank. He gazed upon the mirth around him, as if he could not participate therein. Apparently, the light laughter of the fair only attracted his attention, that he might by a look quell it, and throw fear into those breasts where thoughtlessness reigned. Those who felt this sensation of awe, could not explain whence it arose: some attributed it to the dead grey eye, which, fixing upon the object's face, did not seem to penetrate, and at one glance to pierce through to the inward workings of the heart; but fell upon the cheek with a leaden ray that weighed upon the skin it could not pass.

His peculiarities caused him to be invited to every house; all wished to see him, and those who had been accustomed to violent excitement, and now felt the weight of ennui, were pleased at having something in their presence capable of engaging their attention. In spite of the deadly hue of his face, which never gained a warmer tint, either from the blush of modesty, or from the strong emotion of passion, though its form and outline were beautiful, many of the female hunters after notoriety attempted to win his attentions, and gain, at least, some marks of what they might term affection: Lady Mercer, who had been the mockery of every monster shewn in drawing-rooms since her marriage, threw herself in his way, and did all but put on the dress of a mountebank, to attract his notice—though in vain—when she stood before him, though his eyes were apparently fixed upon hers, still it seemed as if they were unperceived;—even her unappalled impudence was baffled, and she left the field.

But though the common adulteress could not influence even the guidance of his eyes, it was not that the female sex was indifferent to him: yet such was the apparent caution with which he spoke to the virtuous wife and innocent daughter, that few knew he ever addressed himself to females. He had, however, the reputation of a winning tongue; and whether it was that it even overcame the dread of his singular character, or that they were moved by his apparent hatred of vice, he was as often among those females who form the boast of their sex from their domestic virtues, as among those who sully it by their vices.

Lord Ruthven: What’s up, I’m pretty, I hate you all, my goal in life is to ruin any and all happiness happening near me, thirsty chicks DNI, sinners ditto, y’all got any virtuous ladies around here? Asking for non-nefarious purposes, honest

The well-to-do of London, apparently: Guys, guys, check out this sexy well-spoken goth we found, he makes us miserable, we love him

Following this, we’re introduced to the protagonist, a well-off young man named Aubrey who is, the narrative points out, a wee bit sheltered due to a lot of soft living, general naivete, and a big mushy Romantic’s heart about things like honor and art and so on. He meets Lord Ruthven. He becomes fascinated by his character. One line in particular spells out his mistake perfectly:

—allowing his imagination to picture everything that flattered its propensity to extravagant ideas, he soon formed this object into the hero of a romance, and determined to observe the offspring of his fancy, rather than the person before him.

The young man attaches himself to Ruthven like a puppy, even going out of his way to schedule his traveling to time itself with Ruthven’s own plans to move on.

Aubrey: Hey, buddy! :) I just happened to overhear you were going to do some traveling! :) So am I! :) What a coincidence! :) Would be super awesome not to go alone, though, being my first time really out and about, with no learned and mysterious handsome older gentleman to wander around with, ha ha! :)

Lord Ruthven:

Aubrey: :)

Lord Ruthven: …Would you like to join m—

Aubrey, already dragging his luggage: YesYeahSureIfYouInsist

So off they go, enjoying the tourist spots. Aubrey just wishes Ruthven was more interested in, you know, the vacation aspect versus abjectly, almost supernaturally, casting ruin upon everyone he comes in contact with. In true Devil-in-All-But-Name fashion, Ruthven has a habit of turning every interaction with others into one resulting in an act of cruelty. One of the most interesting points is the way he gambles.

Namely, if he’s in a game with some lout who will only use his gains to sink deeper into personal vices, he always loses, with great sums and not a tear shed. If he enters a game with a desperate player whose every cent is precious, needed for their life and the well-being of loved ones, the tables being a last recourse between themselves and destitution? Ruthven wins. Every time.

The rule holds the same when he gives out charity as plain old alms. Desperate and good and simply an unfortunate trying to get by or get a leg up? Fuck off. Begging for money to feed a wretched and self-destructive habit? He empties his pockets. Reading this, it could just be taken for an ordinary combo of skill and sadism, or a manner of psychic vampirism. Either way, our guy is showing his true colors.

Aubrey also discovers what happens to all the virtuous ladies Ruthven appeared to prefer over less scrupulous babes back home. All of them, without fail, fell apart into degeneracy in a way that suggests a total deformation of their former selves. Yeah, we’re going full ‘corruption of the innocent’ here. Dude just needs horns and a pitchfork. So where does the vampire stuff come in? We’re getting there. (Also, note that said degeneracy is later revealed to be him at his tamest when he picks out a nice girl. Not all of them get to live.)

Aubrey, now informed of his traveling companion’s MO and freshly wary for some new sweet girl Ruthven’s been sniffing after, leaves a warning for the targeted family and straight up ditches the guy. He heads to Greece solo. He falls in love with the daughter of a family he stays with, Ianthe, who shares horror stories of the vampire. And their predilection for feasting on young girls.

Guess who gets vamp-murdered, with her cries and a very familiar voice reaching Aubrey’s ear in the night? RIP Ianthe.

Aubrey falls to grief and a fever. While he’s in bed, guess who shows up?

Lord Ruthven: :)

Aubrey: >:(

Lord Ruthven: Sorry about your girlfriend. I was conveniently very far away in Alibi Land when I heard of the tragedy. Want to be friends and travel again?

Aubrey: :)

Obviously there’s more nuance, but Ruthven is very much the absolute king of persuasive wordsmithing (or else is just too handsome to stay creeped out at). They travel some more. Then Lord Ruthven dies.*

*Mostly. Poor Ruthven is shot by robbers and the wound necrotizes over a few days. As he’s near ‘death,’ he forces Aubrey to swear a vow of silence about both his illicit deeds and his being dead to anyone for at least a year and a day from now. A bit Fae in the wording there, Ruthy. So much so that, even after the corpse is laid out under the moonlight as was requested by the dying man, even after Aubrey is well away from the place, every time Aubrey feels the urge to mention something of Ruthven to others—including his sweet younger sister—he senses/hears/is grasped by Ruthven.

“Remember your oath.”

It doesn’t help that, surprise, Lord Ruthven is back in town! Alive! And now courting Aubrey’s own sister! Again, fever and a sort of madness locks down on Aubrey, making him seem wild and incoherent even as he tries to work around the binding power of the oath to warn his sister against marrying the man. The ending scenes should scratch a particular itch when it comes to us folks who have theorized about what fate might have befallen Jonathan Harker if he was counted so loony that he needed protection from himself.

Namely …

Aubrey, when he was left by the physician and his guardians, attempted to bribe the servants, but in vain. He asked for pen and paper; it was given him; he wrote a letter to his sister, conjuring her, as she valued her own happiness, her own honour, and the honour of those now in the grave, who once held her in their arms as their hope and the hope of their house, to delay but for a few hours that marriage, on which he denounced the most heavy curses. The servants promised they would deliver it; but giving it to the physician, he thought it better not to harass any more the mind of Miss Aubrey by, what he considered, the ravings of a maniac. Night passed on without rest to the busy inmates of the house; and Aubrey heard, with a horror that may more easily be conceived than described, the notes of busy preparation.

Morning came, and the sound of carriages broke upon his ear. Aubrey grew almost frantic. The curiosity of the servants at last overcame their vigilance, they gradually stole away, leaving him in the custody of a helpless old woman. He seized the opportunity, with one bound was out of the room, and in a moment found himself in the apartment where all were nearly assembled.

Lord Ruthven was the first to perceive him: he immediately approached, and, taking his arm by force, hurried him from the room, speechless with rage. When on the staircase, Lord Ruthven whispered in his ear—"Remember your oath, and know, if not my bride today, your sister is dishonoured. Women are frail!"

So saying, he pushed him towards his attendants, who, roused by the old woman, had come in search of him. Aubrey could no longer support himself; his rage not finding vent, had broken a blood-vessel, and he was conveyed to bed. This was not mentioned to his sister, who was not present when he entered, as the physician was afraid of agitating her. The marriage was solemnized, and the bride and bridegroom left London.

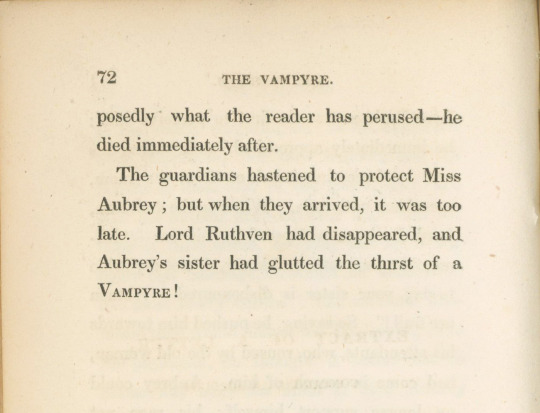

Aubrey's weakness increased; the effusion of blood produced symptoms of the near approach of death. He desired his sister's guardians might be called, and when the midnight hour had struck, he related composedly what the reader has perused—he died immediately after.

The guardians hastened to protect Miss Aubrey; but when they arrived, it was too late. Lord Ruthven had disappeared, and Aubrey's sister had glutted the thirst of a VAMPYRE!

Yeah.

He gets away with all of it. The absolute fucker.

It honestly stuns me that he doesn’t get any modern mileage, same as Clarimonde. These two are at the perfect polar opposite ends of the vampire spectrum.

Clarimonde = Full Bacchanalia Mode, Baby, Let’s Bang, Let’s Bleed, Let’s Party Like the Church Isn’t Watching (and If They Are, See If I Give a Fuck!)

Lord Ruthven = I Can, Must, and Will Ruin Everything and Everyone in Reach, I’ll Drink Your Girlfriend, I’ll Drink Your Sister, I’ll Blow a Fucking Blood Vessel in Your Brain, Try Me

“The Vampyre,” is available to read on Project Gutenberg (though you have to scroll a bit to pass the introduction), same as Clarimonde’s story, “La Morte Amoureuse.” I sincerely recommend both as prime Classic Vampire © ™ tales that precede the more well-known, “Carmilla,” and Dracula. They deserve more love (or, in Ruthven’s case, more loathing). If we’re heading into some Draculean Old School Vampire Renaissance in the midst of all our Dracula Daily/The Invitation/Last Voyage of the Demeter/Renfield/yes, even Moffat’s wet fart of a Dracula series goings-on, these guys deserve to catch some belated bloodsucker limelight too.

(Credit to @theskyismadeofpenguins for the cropped illustration, the original art is a thing of majesty, it deserves a spot in the MoMA)

#Lord Ruthven#the original undead asshole Dracula wishes he was#I like to imagine Clarimonde hiring a portrait artist explicitly to paint likenesses of Dracula and Ruthven#handing copies to the bouncers at her ye olde revelries#along with crosses holy water and blessed pistols#'The asshole with the moustache doesn't get in because he keeps trying to poach all my hot friends for his castle'#'The pretty asshole doesn't get in because he is both a guest and party killer'#'If they speak more than a syllable to you after being told they're not allowed inside you have my permission to get violently creative'#'I've got a crypt on hand specifically for the leftovers'#anyway#The Vampyre#john william polidori#vampire literature#dracula#clarimonde#la morte amoureuse

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

When is Tumblr going to read The Vampyre by John William Polidori

#it's my favourite 19th century vampire work <3#the vampyre#john william polidori#1816 geneva#fuck off me

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

But first, on earth as vampire sent,

Thy corse shall from its tomb be rent:

Then ghastly haunt thy native place, And suck the blood of all thy race;

There from thy daughter, sister, wife, At midnight drain the stream of life;

Yet loathe the banquet which perforce

Must feed thy livid living corse:

Thy victims ere they yet expire

Shall know the demon for their sire, As cursing thee, thou cursing them,

Thy flowers are withered on the stem.

But one that for thy crime must fall, The youngest, most beloved of all,

Shall bless thee with a father's name - That word shall wrap thy heart in flame!

Yet must thou end thy task, and mark Her cheek's last tinge, her eye's last spark, And the last glassy glance must view Which freezes o'er its lifeless blue;

Then with unhallowed hand shalt tear

The tresses of her yellow hair, Of which in life a lock when shorn

Affection's fondest pledge was worn,

But now is borne away by thee,

Memorial of thine agony!

Wet with thine own best blood shall drip

Thy gnashing tooth and haggard lip;

Then stalking to thy sullen grave,

Go - and with Gouls and Afrits rave;

Till these in horror shrink away

From spectre more accursed than they!

excerpt from Lord Byron’s Giaour, as seen in John William Polidori’s The Vampyre

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m going to reread & annotate a copy of John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” that I printed the other day. I might not liveblog it much or at all, but I’ll show off any fun annotations afterwards for sure :D👍

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning that Lord Ruthven is pronounced “Riven” after half a decade of saying “Ruth-ven” is the sort of thing that makes me want to take a bath in a wood chipper

#vampires#vampire#the vampyre#lord ruthven#john polidori#john william polidori#it’s not a big deal but also it is#riven is so much easier for me to say but I’m still mad about it

0 notes

Text

youtube

Chapter 1. Part 1. William Lamb

"...Brocket Hall was dark and lonely that night, even the silent shadows seemed menacing. The Lambs still weren’t used to the darkness of the countryside and it would take some adjustment. Their family had recently moved their household back to their country estate, Brocket Hall, to quiet the suggestions of an affair between Lady Caroline Lamb and the upstart poet, Lord Byron..."

-V. B. Lavender, To Be The Hunter or the Hunted via Youtube (it's an audiobook)

There are subtitles available too on the videos. This will be an ongoing project posting to YouTube every so often.

#historic fiction#lgbt characters#audio series#vampires#lord byron#william lamb#lady caroline lamb#Lord M#mary shelley#percy shelley#dr. polidori#claire clairmont#vampire hunters#demons#demon slayers#regency AU#the romantics#paranormal#bisexual characters#bisexual#writing#writeblr#V. B. Lavender#WIP#audio books#2023 release#Youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

I've been doing a lot of reading lately about the history of vampires in fiction and how the vampire as we know it today first entered literature, and the subject is honestly fascinating. The traditional folklore around vampires and vampire-like creatures is largely very different from what we'd think of as a vampire today, and it's also very different from how vampires appeared in even their earliest literary incarnations.

For one thing, there's nothing particularly alluring about most traditional vampires. They're bloated corpses that have crawled out of their graves, not dashing mysterious counts in lonely castles. They're not a particularly stylish or sexy monster.

However, from pretty much the moment that western literature first turned to the vampire myth for inspiration, writers saw something in the concept to sexualize. The poem "Der Vampir" (The Vampire) by Heinrich August Ossenfelder is often cited as the first ever true literary depiction of a vampire (published 1748!), and it is about a man corrupting a chaste and religious woman through his unwanted kiss/vampiric bite. John William Polidori's 1819 short story "The Vampyre" is widely seen as the first work to truly codify vampire fiction, and the titular Vampyre Ruthven is in large part inspired by the womanizing Lord Byron. Le Fanu's Carmilla depicts an intense attraction between Carmilla and her victim Laura. Stoker's Count Dracula is a man with overly flushed lips and hair on his palms, marks of Victorian fears of sexuality.

From the very start, vampires in literature have been a sexual monster. They're emblems of the seductive and terrible—the kiss of death that you can't help but be drawn to anyway. A violent forced intimacy that will corrupt you and drain away your very life force. There's a great deal of xenophobia and fear of the un-christian in early vampire fiction as well, but the fear of sex and sexual assault have always been a driver of literary vampires' horror and allure. Writers seem eternally split between desire for the vampire and revulsion at that very lust, even from the moments that the creatures first graced the page.

There's a great tradition of vampiric fiction both using vampirism to evoke sexual predators and making vampires themselves desirably sexy. Thus, given that it is very concerned with sexual assault and bodily autonomy as themes, often uses predation by a vampire to evoke sexual violence, and is deeply horny about vampires and blood drinking, Jun Mochizuki's The Case Study of Vanitas is actually one of if not the best modern successor to the canon of early vampire literature. In this essay, I will

#rare vnc post on main bc starting off with my obvious vnc icon and url would spoil the punchline#wanna take y'all by surprise a little ;P#anyway this post is a joke but the point I'm making genuinely kinda isn't#you know how it is#I am genuinely fascinated by the ways that vnc is in conversation with the literary sources that it pulls from#it really is riffing on a LOT of the same ideas through a modern lens#vnc#vanitas no carte#the case study of vanitas#invasion of the frogs

458 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just recently found your blog and i love it!!! do have any theories for vanitas' original name? My guess is Abraham, for all it doesn't really fit him, after Abraham van hellsing, who is both a doctor and vampire expert, which I think matches mochijuns naming conventions. Doesn't hurt that it matches with Noe (noah) religiously.

Thank you!! Welcome to the party ;D

Traditionally, I've always said I don't have any strong theories on Vanitas's name—at least none that I actually expect to come true. I think(?) I've talked about this before, but that's not really the kind of theorizing I do? Since right now any name theory is wild guessing and speculation, not elaborating from the text.

That said, I do now have one pet theory that I'm partial to (one I didn't have the last time someone asked me this). I don't actually think this is going to be the case in canon, but for now, I really enjoy the concept of Vanitas's real name being Byron. This is mostly because I think it would be funny, but there are some actual connections too.

Long context short, Lord Byron wrote an unfinished draft of what would have been the first modern vampire story, and then his personal doctor (John William Polidori) took the same idea and fleshed it out into The Vampyre—the actual generally recognized first modern vampire story. But! Polidori's version of the vampire (the version that established a lot of our vampire tropes) was partly inspired by Byron himself. So Byron is sort of this almost-but-not-quite vampire author, writing but also inspiring the tropes of vampirism, which reflects interestingly on Vanitas's relationship to actual vampirism. He's not a vampire, but he's much closer to one than any other human, and in demeanor, he acts more stereotypically vampiric than Noé and many other vampire characters.

Also, Byron is the namesake of the Byronic hero, which Vanitas is a perfect example of. He's brooding, cynical, arrogant, and intelligent, but despite his gloom and self-destructiveness, he has a sort of lonely magnetism about him. Once again, the concept of the Byronic hero is inspired by/named after both Byron himself and the characters he wrote.

As I said, I don't think I'm going to be right about this, as there's a million other theories that could fit just as well, but in the meantime, the concept does tickle me. Polidori's Byron-based vampire even has an especially strong connection to the moon :D.

Anyway, I really like your theory as well. I've noted before that it's interesting that there's no Van Hellsing reference in VnC (or any direct Dracula references at all, save poor dead Mina). It's almost surprising given Dracula is the iconic vampire story. I never even considered that there could be a Dracula reference hidden right there in Vani and waiting to be discovered, but it does make sense. The doctor/vampire expert connection is really fun and fitting! Though I'm afraid I don't know enough about the biblical Abraham to say anything interesting about that aspect beyond what you pointed out there.

#look mom I finally have my very own Vanitas name theory! I'm finally a real theorist!#(lmao)#thanks for the ask!#ask#anon#vnc#vanitas no carte#the case study of vanitas#theory#comparison#vanitas my beloved

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

the relationship between vampirism & queerness

Vampires are inherently queer characters. Their queerness is represented in countless texts including Bram Stoker’s novel, Dracula (1897), Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella, Carmilla (1872), the film Interview with the Vampire (1994), and Rainbow Rowell’s novel Carry On (2015). Vampires’ queerness is enforced by a multitude of factors; notably the sexual nature of a vampire itself, the relationship vampires have with ‘normal’ society, and the inherent evilness behind vampires.

The queerness of vampires is enforced by the sexuality behind the concept of a vampire itself. Unlike other monsters, vampires are not apparently beastly or undead. Their evil nature is hidden beneath a suave, charismatic personality. The ‘charming vampire’ character was first popularised by John William Polidori in his 1819 short story, The Vampyre. This story was a source of inspiration for Carmilla and Dracula, who further cemented ‘charisma’ into the fundamentals of the vampire archetype. A part of vampires’ hunting method is seduction, which often leads to a blurry line between ‘prey’ and ‘romantic interest’. One of the most iconic traits of a vampire is the bite to the neck. Popularised by Bram Stoker, vampires typically drain their victims of blood from the neck. While it’s a convenient spot because of the carotid artery, a plentiful source of blood, it’s often argued that the sexual nature of biting one’s neck played a large part in the popularisation of it.

The sexulisation of vampires opens up an opportunity for authors to explore queerness in a non-explicit setting. The relationship between a vampire and their victim can mirror that of a romantic/sexual couple. Often vampire characters are more fluid with their sexuality and they influence their human prey with their vampiric, sexual, queer nature. In Interview with the Vampire, Louis de Pointe du Lac’s story starts with his partner, Lestat de Lioncourt turning him into a vampire. The scene in which Lestat bites him includes him pinning Louis to the ground and biting his neck before whispering in his ear. “You can be young always, my friend, as we are now.” Lestat’s use of ‘we’ as opposed to ‘you can stay young’ shows his interest in staying with Louis. Louis’ character development stems from a queer male vampire changing his life. Count Dracula’s prisoner was Jonathon Harker, with whom he was extremely infatuated. Upon finding other female vampires attempting to bite Jonathon’s neck, Dracula was outraged. "How dare you touch him, any of you? How dare you cast eyes on him when I had forbidden it? Back, I tell you all! This man belongs to me!” Dracula was possessive of Jonathon, which alludes to an attraction beyond chaste fascination. In Carmilla, the titular character came into human Laura’s life and engaged her in a romantic relationship. Carmilla says “‘I have been in love with no one, and never shall,’ she whispered, ‘unless it should be with you.’” to Laura, who consistently described Carmilla as attractive, “She was so beautiful and so indescribably engaging.” While it’s up to the reader if Carmilla’s feelings were simply an act used to lure Laura in or true love, their relationship was intimate and unmistakingly queer. In Carry On, Tyrannus Basilton ‘Baz’ Grimm Pitch never bites Simon Snow, but they are involved. Baz says “You were the centre of my universe. Everything else spun around you.” While Baz did not attempt to make Simon a vampire, he was knowingly queer before Simon; Simon was unaware of his own queerness before Baz. This is another example of a queer vampire influencing their human partners. The queer themes in these texts are fueled by the sensual nature of the vampire characters.

One way vampires are shown as an allegory for being queer, is the relationship vampires have with regular society. A vampire fitting in with human communities is difficult, due to the inability to be in sunlight or eat normal food. Queer folk historically struggle to fit into heteronormative spaces seeing as, like vampirism, it’s been widely viewed as a negative trait. That sense of displacement or otherness felt by queer people is mirrored by vampires. Count Dracula’s odd behaviour was quickly picked up on by Jonathon. Upon finding Jonathon using a shaving mirror, Dracula was enraged. “This is the wretched thing that has done the mischief. It is a foul bauble of man's vanity. Away with it!" And opening the window with one wrench of his terrible hand, he flung out the glass.” Similarly, Simon always suspected Baz was a vampire, and spent his highschool career trying to prove it. “Are you saying you don’t think Baz is a vampire?” “I know he’s a vampire. But it’s still unconfirmed.” Baz being odd because he was a vampire is not unlike his being different because he was queer. Baz was always self aware he was unlike everyone else. Baz and Simon in a crowded room: “They’ll know that we’re gay.” “There go my job prospects. What will my family say? Baz, you’re actually, literally the only thing I have to lose. So as long as doing gay stuff in public doesn’t make you hate me, I don’t really care.” Regular, heteronormative, human society makes both the vampire community and queer people feel like outsiders; creating a sense of guilt for being different. Baz and Louis have both chosen to drink rat blood to avoid drinking humans. Their inner turmoil over being a blood-sucking demon reflects the common queer mindset of feeling guilty over being different. The sense of ‘otherness’ unites queer folk and vampires.

From their conception in common folklore, vampires have been written as evil, soulless beings. Vampires are undead demons that drink blood and transform innocent humans into more blood-drinking demons. The queerness behind vampire characters is linked to their being inherently evil. Vampires turning humans into vampires is a metaphor for gay people ‘corrupting’ others with their homosexuality. After the death of his wife and child, Louis was attacked by Lestat and turned into a vampire. Lestat gave him a whole new life and they adopted a daughter, Claudia. Louis went from a ‘straight’ human man who played his part in regular society, to a queer vampire. Vampires have a massive influence over their victims and partners. Their influence, in terms of both vampirism and homosexuality, leaves lasting effects on their prey. In the aftermath of Carmilla and Dracula, Laura and Jonathon are said to have struggled with recovery. From Carmilla, “The following Spring my father took me a tour through Italy. We remained away for more than a year. It was long before the terror of recent events subsided.” Vampires’ impact on their human partners is not necessarily for the better. For Laura, it was detrimental to herself, whereas in other stories, such as Carry On, Simon Snow was better off with his vampire boyfriend. Baz helped him find a version of himself he was unfamiliar with and they started their new life together. “He's not a villain. He's just a boy. I'm kissing a boy. I'm kissing Baz.”

Vampirism is an allegory for being queer. The queerness with which vampire characters are written is shown through the sexulisation of vampires, the sense of ‘otherness’ felt by both parties, and the inherent evil nature behind vampires. The evidence and recurring themes across Dracula, Carmilla, Interview with the Vampire and Carry On show the ways in which queerness shows itself in vampire texts. Writers using vampires as an outlet for queer allegories implies an urge on the author’s part to explore a more fluid perspective on sexuality. I think a lot of the appeal of vampire texts and characters lies in the desire to fantasise about a different way of being — it’s a safe, abstract way of exploring one’s own sexuality through stories. Vampires represent homosexuality in a subtle, indirect way that connects with the queer community and create a way to show queer stories without being blatantly queer.

#essay#writing#vampires#queerness#dracula#bram stoker#interview with the vampire#anne rice#carry on#rainbow rowell#carmilla#sheridan le fanu#vampire#dracula daily#you might be interested#queer#gay#1313 words#which is cool#jonathon harker#count dracula#simon snow#baz grimm pitch#tyrannus basilton grimm pitch#carry on series#louis de pointe du lac#lestat de lioncourt#iwtv#carmilla x laura#snowbaz

408 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Vampyre by John William Polidori

This is supposed to be the first vampire story in European literature, predating both Carmilla and Dracula, and it was a bit of a disappointment for me. I don't know what I was expecting to be honest, but the story fell flat for me. It was definitely interesting to read and I am glad I did finally read it, but it's definitely not going to become one of my favourite gothic horror pieces.

#2024 book#book cover#book#book rec#book review#book recommendation#bookblr#booklr#reading#mine#the---hermit

14 notes

·

View notes

Photo

SLAVIC VAMPIRES

• modern Polish — upiór, upir, wąpierz, wupi

• Czech and Slovak — upír

• Ukrainian — упир (upyr)

• Russian — упырь (upyr')

• Belarusian — упыр (upyr)

• Old East Slavic — упирь (upir')

A demonic being from Slavic folklore, a prototype of the vampire.

🦇 The term upiór was introduced to the English-language culture as a "vampyre", mentioned by Lord Byron in “The Giaour“ in 1813, described by John William Polidori in "The Vampyre" in 1819, and popularised by Bram Stoker's “Dracula”. With the development of mass culture, he returned as a "vampire" recognizable in literature and film.

🦇 Slavic belief indicates a stark distinction between soul and body. The soul is not considered to be perishable. The Slavs believed that upon death the soul would go out of the body and wander about its neighbourhood and workplace for 40 days before moving on to an eternal afterlife. Thus pagan Slavs considered it necessary to leave a window or door open in the house for the soul to pass through at its leisure. During this time the soul was believed to have the capability of re-entering the corpse of the deceased. Much like the spirits mentioned earlier, the passing soul could either bless or wreak havoc on its family and neighbours during its 40 days of passing. Upon an individual's death, much stress was placed on proper burial rites to ensure the soul's purity and peace as it separated from the body. The death of an unbaptized child, a violent or an untimely death, or the death of a grievous sinner (such as a sorcerer or murderer) were all grounds for a soul to become unclean after death. A soul could also be made unclean if its body were not given a proper burial. Alternatively, a body not given a proper burial could be susceptible to possession by other unclean souls and spirits. Slavs feared unclean souls because of their potential for taking vengeance.

🦇 From these deep beliefs pertaining to death and the soul derives the invention of the Slavic concept of Ubır. A vampire is the manifestation of an unclean spirit possessing a decomposing body. This undead creature needs the blood of the living to sustain its body's existence and is considered to be vengeful and jealous towards the living. Although this concept of vampire exists in slightly different forms throughout Slavic countries and some of their non-Slavic neighbours, it is possible to trace the development of vampire belief to Slavic spiritualism preceding Christianity in Slavic regions.

🦇 An upiór was a person cursed before death, a person who died suddenly, or someone whose corpse was desecrated. Other origins included a dead person over whom an animal jumped, suicide victims, witches, unchristened children, and those who were killed by another upiór.

🦇 Slavic vampires were able to appear as butterflies, echoing an earlier belief of the butterfly symbolizing a departed soul. Some traditions spoke of "living vampires" or "people with two souls", a kind of witch capable of leaving its body and engaging in harmful and vampiric activity while sleeping.

#Vampires#Upiór#slavic culture#slavic folklore#slavic mythology#slavic#slavs#pagan#poland#czechia#czech republic#slovakia#ukraine#russia#belarus#posted by me#🔮

264 notes

·

View notes