#李白

Text

For the 2024 dostoyevsky-official challenge by @dostoyevsky-official:

It's 静夜思 or "Thoughts on a Quiet Night" by Tang Dinasty poet Li Bai (李白).

I already knew the poem but now I've memorized it (and practiced writing it).

Haven't decided on a poem for February yet, but I'll keep it short...

#my voice#challenge#poetry challenge#chinese poetry#li bai#李白#langblr#chinese langblr#poetry#chinese language#mandarinblr#中文

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

answer based on personal preference! in the tags please tell me why, and also if you've read their work in the original or in translation :)

#li bai#du fu#李白#杜甫#唐诗#chinese poetry#chinese literature#my polls#tang poetry#conducting a little study!#the stereotype is that du fu is objectively better but everyone secretly prefers li bai so i'm curious to see how true that is#not saying which one i prefer for now. keeping my cards close to my chest 👀

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

BEBIENDO SOLO A LA LUNA

Con un jarro entre las flores,

bebo solo y sin amigo.

Le brindo a la clara luna,

seremos tres con mi sombra.

La luna ni oye ni bebe;

mi necia sombra me sigue.

Mas no tengo otra compaña

mientras dure primavera.

Si canto, la luna oscila;

Si bailo, mi sombra duda.

Sobrios, conversamos juntos;

ebrios, es la desbandada.

Unión eterna, si esquiva;

nos reunirá la Galaxia.

Li Bai

di-versión©ochoislas

*

月下獨酌四首

花間一壺酒 獨酌無相親

舉杯邀明月 對影成三人

月既不解飲 影徒隨我身

暫伴月將影 行樂須及春

我歌月徘徊 我舞影零亂

醒時同交歡 醉後各分散

永結無情遊 相期邈雲漢

李白

#Li Bai#literatura china#poesía de Tang#soledad#convivialidad#embriaguez#sombra#luna#di-versiones©ochoislas#李白

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

侠客行 - An Ode to Swordsmen

by 李白 (Li Bai, 701 - 762)

赵客缦胡缨 吴钩霜雪明

zhào kè màn hú yīng, wú gōu shuāng xuě míng

Chivalrous guest of Zhao with his tasseled helm, sabre shining snow-bright,

银鞍照白马 飒沓如流星

yín ān zhào báimǎ, sà dá rú liúxīng

silver saddle glowing against his horse's white, passing swift as shooting stars in flight.

十步杀一人 千里不留行

shí bù shā yīrén, qiānlǐ bù liú xíng

Ten steps, he kills a man; a thousand li - nought will stay his pace.

事了拂衣去 深藏身与名

shì liao fú yī qù, shēn cángshēn yǔ míng

Deed done, with a brush of his robes, he buries all and leaves no name, no trace.

闲过信陵饮 脱剑膝前横

xián guò xìnlíng yǐn, tuō jiàn xī qián héng

In idleness, with Lord Xinling he drank, sword doffed, resting across his knees;

将炙啖朱亥 持觞劝侯嬴

jiāng zhì dàn zhū hài, chí shāng quàn hóu yíng

he partook in a roast with Zhu Hai, and tipped a vessel in invitation to Hou Ying.

三杯吐然诺 五岳倒为轻。

sān bēi tǔ rán nuò, wǔyuè dào wèi qīng

Three cups in, out tumbled a promise; beside it, the Five Mountains even seemed light.

眼花耳热后 意气素霓生。

yǎn huā ěr rè hòu, yìqì sù ní shēng

Visions cleared and warmed ears cooled; from spirits ardent still, a white rainbow burst forth.

救赵挥金槌 邯郸先震惊。

Jiù zhào huī jīnchuí, hándān xiān zhènjīng

Wielding an iron hammer in Zhao’s aid, how every heart in Handan first quaked;

千秋二壮士 烜赫大梁城。

qiānqiū èr zhuàngshì, xuǎn hè dàliáng chéng

all ages henceforth, two brave men were remembered, their names aflame in Daliang City.

纵死侠骨香,不惭世上英。

zòng sǐ xiá gǔ xiāng, bù cán shìshàng yīng

In spite of death, heroes’ bones smolder in perpetual fragrance, leaving this world with no regrets.

谁能书阁下,白首太玄经。

sheí néng shū géxià, bái shǒu tài xuán jīng.

Who can remain ‘neath shelves of tomes ‘till they are old and grey with their ‘Canon of Supreme Mystery’?

………………………………………………………..……………..………

NOTES

And here I present poem 2 of the homework group!

So I said not all of the assignments will get a post, and that is still true. But like, LOOK AT THIS 侠客行!!!!! It’s passionate, it’s hilarious, it’s got a story! Who could possibly resist?

But it has also been a mad three days at work, stacked on a merlion-tastic bout of food poisoning. So, as I did not have time for unraveling-type digging and writing practice, this will be structured like a normal post.

BACKGROUND

Li Bai the wine-mad Tang Dynasty poet needs no introduction right? This section will focus on the couple of years in his life before and during 744, which was the year 侠客行 was written.

A fascinating titbit that will become more interesting later: Li Bai was a skilled swordsman, and had been passionate in his learning and practice since a young age. The sword was a source of inspiration for many of his poems, in fact. Here is an interesting article about that! I would highly recommend it if you’re open to seeing more samples of lines from his heroes, sword and sword fighting related works.

In 742, Emperor Xuanzhong on recommendation, summoned Li Bai to court and was impressed enough with his talent to offer him a position in Hanlin Academy, ‘which served to provide scholarly expertise and poetry for the Emperor’. Thus began the period of his life where he served as the Emperor’s personal on-call poetry, song and entertainment provider. During this time, he was showered with the Emperor’s favour and his fame grew to new heights.

It was probably tiresome though, knowing his ambitions. There were also likely jealous people about. And he certainly had been drinking a lot! Whatever led to the result, in the year 743, at the age of 43, he was bestowed a great deal of gold by the Emperor and ‘set free’.

It is 744, and he is traveling a lot. During this time, he met Du Fu (yes. that Du Fu. eleven years his junior, and who would later go on to write eleven poems for him that survive today) and they became friends over drinks, making a deal to meet again in Liangsong (Kaifeng / Shangqiu area of today). In the Autumn of this year, they met again as agreed and made another new friend, Gao Shi, whom they bonded with over writing, politics and their shared worry about the country. After parting, Li Bai went on to Qi Prefecture where he became a daoist priest at Ziji Temple.

It was around this period in Li Bai’s life that 《侠客行》 was written. [1]

[1] Sourced from Li Bai’s page and the poem’s introduction on Baidu. 2022, September 10

FORMAT

In the previous post I mentioned the new style poetry (近体诗) and old style poetry (古体诗) forms of Tang Dynasty poetry. This one is a five character old style poem.

The key characteristic of old style poetry is that it is unregulated. There is a lot of freedom here in terms of tones, where characters can sit and also their rhyming (...at least, that’s my very valid excuse for rhyming the first 4 lines, like the poem did, and abandoning the rest to whim and fancy xD)

STORY

There are twenty four lines of five characters each. For my rambles, the first twelve lines shall be grouped into one part, the next eight into the second part, and the last four into the third part.

Part One

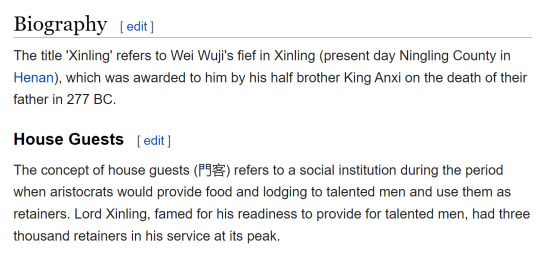

This first part introduces the character of a particular curved-sword wielding hero. His perspective is almost like an outsider looking in, giving us a front row seat to real people and events as they are told in written history. Specifically, this is about a story in the Spring and Autumn period about Lord Xinling, Wei Wuji gaining the loyalty of Hou Ying and his friend Zhu Hai, and how they saved the State of Zhao when it was under siege. This all happened in about 257 BCE.

In Autumn a thousand and one years later, this famous poet named Li Bai wrote them all into a poem. He had created this for an audience that already knew their story, but alas illiterate yjtc was not within the range of audience he thought of while writing this. Thankfully, baidu exists!

The first first four lines describe the appearance of his fictional swordsman and original character in loving detail, giving him the most dramatic and cool entrance through imagery.

赵客缦胡缨 | Chivalrous guest of Zhao with his tasseled helm,

吴钩霜雪明 | sabre shining snow-bright,

银鞍照白马 | silver saddle glowing against his horse's white,

飒沓如流星 | passing swift as shooting stars in flight.

King Wen of Zhao was famed for his love of sword fights. It was written in one of Zhuangzi’s miscellaneous chapters On the Sword / 说剑 that guests of Zhao who were a deft hand with the sword numbered three thousand. It makes sense to create a swordsman character from such a legend because it’s just immediately very striking!

缦胡 (màn hú) are plain, unadorned ribbons that secured a hat to one’s head, and 缨 (yīng) is a tassel - not at all sure if I got this right, but let’s just go along with this reading! And here’s a mark of a dedicated OC creator: historically accurate terms! An 吴钩 (wú gōu), a type of sword with a curved blade was a popular weapon during the Spring and Autumn period.

I wouldn’t have been surprised at all if told this man was also dressed in white - what with all the snow, frost, white horse and silver going on. The last line about 飒沓如流星 | passing swift as shooting stars in flight, gives him such a instantly dashing vibe!

(Guess who has the word white in their name. Guess! He has it twice over… both in his given and courtesy name.)

(Source)

十步杀一人 | Ten steps, he kills a man

千里不留行 | a thousand li - nought will stay his pace.

事了拂衣去 | Deed done, with a brush of his robes.

深藏身与名 | he buries all and leaves no name, no trace.

The first two lines are about his skill, single minded focus and determination. They are also a reference to a quote from the same chapter of Zhuangzi. There’s a very domineering and ‘inevitable death coming for you’ vibe from it! (Competence kink activate!!!) But then just as clearly in a quick turn of the brush, it is clarified that this person does not desire to make a name for himself, nor does he want riches and fame - he doesn’t leave any calling card behind!

I think 事了拂衣去 深藏身与名 is perhaps the most quoted and well known line of this poem.

It feels like a very crisp and decisive motion. A person who just wants to do what he feels is the right thing.

闲过信陵饮 | In idleness, with Lord Xinling he drank,

脱剑膝前横 | sword doffed, resting across his knees;

将炙啖朱亥 | he partook in a roast with Zhu Hai,

持觞劝侯嬴 | and tipped a vessel in invitation to Hou Ying.

This is the part that leads the reader into the lives of these historical figures. Remember - they were historical figures as well to Li Bai and his contemporaries.

Lord Xinling, as mentioned before, is Wei Wuji. He was one of the Four Lords of the Warring States, and a very prominent aristocrat and general of the State of Wei.

(Source)

Hou Ying was a mysterious old man of seventy, working as a guard at the city gates of Daliang, capital of the State of Wei. Wei Wuji had seeked him out, hearing that he was a worthy man with talent, and eventually secured his loyalty as retainer after Hou Ying observed that he was a worthy lord in turn. Part of Wei Wuji’s strategy had been to throw a banquet, but had the tables turned on him, so to speak, and then his reputation benefitted in the same stroke!

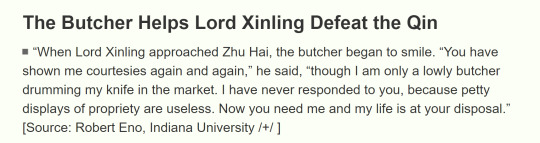

As for Zhu Hai, he was a friend of Hou Ying’s who worked as a butcher in the market because ‘none had recognized his high abilities’. Despite Wei Wuji’s multiple visits and attempts to convince him to be his guest retainer, the man was rebuffed. Zhu Hai never acquiesced until Hou Ying was in his hour of need.

(Source)

You can read more about Lord Xinling’s meeting and interaction with Hou Ying and Zhu Hai in the source above. Just Ctl + F their names.

And so, now knowing a little more about these three people than their titles or how their names look like - Lord Xinling with his retainers, Zhu Hai the butcher and Hou Ying the old city gate guard, their introduction starts to look quite clever.

A capable swordsman who had been a guest of the king of Zhao, would of course be treated with courtesy by Lord Xinling. Even if he did not stay as a retainer, Wei Wuji sounds just like the sort of person who would not have refused a drink on a lazy day with his new acquaintance, even if this person was keeping many secrets. What better way to befriend a butcher, jaded to the world of aristocrats and lords, than through his stomach? And what better attempt to soften sensitive, sharp and observant Hou Ying, than through a jaunty yet courteous offer to toast?

(Tell me this isn’t a self insert from someone who knows the canon.)

Part 2

This part still continues on from the story of the fiction swordsman meeting these figures from the history books. But it is already moving in on the climax.

三杯吐然诺 | Three cups in, out tumbled a promise;

五岳倒为轻 | beside it, the Five Mountains even seemed light.

眼花耳热后 | Visions cleared and warmed ears cooled,

意气素霓生 | from spirits ardent still, a white rainbow burst forth.

This is actually my favourite part of this poem. I laughed reading it at first because of how flippant 三杯吐然诺 was. A drunk man’s promise - taken seriously? And what is especially clever in the wording of the next line, the use of the word 倒 as in 倒是 which gives a certain flavour of an afterthought to ‘contrary to what you might be thinking’. The 五岳 are referring to the Five Great Mountains - five of the most renowned mountains in Chinese history. So, to say that they are light, less important in comparison to a promise made under the influence… well.

Prove it.

And prove it he did. When the effects of the alcohol faded, the blurred vision, the reddened, warm ears, their spirit and sincerity remains - so strong and so true that a white rainbow appears, an omen of unusual events to come.

救赵挥金槌 | Wielding an iron hammer in Zhao’s aid,

邯郸先震惊 | how every heart in Handan first quaked;

千秋二壮士 | all ages henceforth, two brave men were remembered,

烜赫大梁城 | their names aflame in Daliang City.

The story of how Lord Xinling, Wei Wuji ‘Stole the Commander's Tally to Rescue the State of Zhao’ is a famous one, so too was his feat of leading an army of eighty thousand to successfully defend Handan, Capital of the State of Zhao from the siege they were under. But he could not have done it at all without the aid of Hou Ying who advised him on strategy, nor Zhu Hai who, with his extraordinary strength and a hammer, took down the general that Lord Xinling could not.

Considering how this story took up a portion of Lord Xinling’s biography in Shiji 史记 / Records of the Grand Historian, Chapter 77, compiled nearly three hundred and fifty years later. I’d say it did go down in history.

Part 3

This is the conclusion of the poem. After going through the whole story, we return to the title - an ode to swordsmen. There is more than a little bit of exaggeration and idealization of historical events here, but this is a piece of work written to celebrate heroes, to express admiration towards them. Maybe it was all the more dramatic because the writer had dreams that hadn’t been realised yet.

Remember how Li Bai has just ‘escaped’ the capital, finished his travels with friends and turned to daoism. You have to live vicariously through your writing when real life doesn’t deliver, no?

纵死侠骨香 | In spite of death, heroes’ bones smolder in perpetual fragrance,

不惭世上英 | leaving this world with no regrets.

谁能书阁下 | Who can remain ‘neath shelves of tomes

白首太玄经 | ‘till they are old and grey with their ‘Canon of Supreme Mystery’?

太玄经, known also as the Canon of Supreme Mystery was a guide for divination composed by the Confucian writer Yang Xiong (53 BCE–18 CE) of the Western han dynasty in his later years. In his youth, his talent in fu composition earned him a summons to the imperial capital at Chang'an to serve as an Expectant Official, responsible for composing poems and fu for the emperor. It was required of the official in this post to praise the virtue and glory of Emperor Cheng of Han and the grandeur of imperial outings. Outings which he deeply disapproved of for their extravagance.

Yeah.

Ouch.

There’s more than a little salt in there!

But he is also saying as loudly and with as much scorn as he can inject into written word, ‘I don’t want this fate for myself’.

TRANSLATION CHOICES

赵客缦胡缨 | Chivalrous guest of Zhao with his tasseled helm

Helm is most definitely not the accurate word to be using in this sentence. But what sort of headwear would a well travelled commoner wear? The only reference I can think of offhand from this period would be...

Which is... hm. Not a good reference. It’s an entirely different state, for one. (Qin instead of Zhao.) Anyway in conclusion... this will do.

银鞍照白马 | silver saddle glowing against his horse's white

The 照 in the line 银鞍照白马 brought my mind’s eye to reflection, but the saddle is ON the horse? How does it reflect the horse? So then what came to mind was that saddle gleaming in the sun, against a white pelt also gleaming in the sun.

飒沓如流星 | passing swift as shooting stars in flight.

‘Swift’ and ‘flight’ are both aspects/different meanings of 飒沓 in different contexts, but I liked the idea of the horse being swift, but also galloping as if it were in the wind.

Rhyming:

霜雪明 / shuāng xuě míng / shining snow-bright - Line 1

如流星 / rú liú xīng / shooting stars in flight. - Line 2

and

不留行 / bù liú xíng / nought will stay his pace - Line 3

身与名 / shēn yǔ míng / no name, no trace - Line 4.

脱剑膝前横 | sword doffed, resting across his knees

I do know that doffed refers to taking off clothes, but there was no other more elegant way to say ‘took his sword off his belt’. There has to be some give and take sometimes. I hope this doesn’t sound too odd though…

纵死侠骨香 | In spite of death, heroes’ bones smolder in perpetual fragrance

‘Smolder in perpetual fragrance’ brought to you by my dilemma between reading 香 either as fragrance or as incense. Both would work with ‘in spite of death’ 纵死, with fragrance vs the pungence of decay, and prayers & remembrance by future generations represented by incense. Why not keep both, then explain in the notes, right? But then the incense reading was just a lark. Leave a good name for the future generations / 流芳后世 (liú fāng hòu shì), where 芳 can also be read as fragrance, as a phrase has existed since at least the Northern and Southern Dynasties. See A New Account of the Tales of the World, by Liu Yiqing, 403–444. I still like incorporating both though! So that’s how I kept it.

谁能书阁下 | Who can remain ‘neath shelves of tomes

The word 书阁 does actually mean library, or someplace where books are kept. But I enjoyed the mental image of some guy beginning his career with a head of black hair, scribbling under a sparsely populated shelf of books. Time Lapse speedup. The book piles on the shelves behind him rise and fall, rise and fall, all while grey hair starts to appear. And finally, the camera stops on him, pans up to full shelves then zooms in on his full head of white hair and the work in progress book on the table.

#侠客行#李白#oh my goodness this has been incredibly looooong#he is filled with so much salt#poor dude#commentary

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

李白

就是很想畫

#畫#影像創作#繪畫#鄭雲龍#將進酒#李白#artwork#art#illustration#drawing#doodle#ball point pen art#ball point drawing#some silly touch up with felt tip pen#fanart#zheng yunlong#invitation to wine#li bai

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

靜夜思 / quiet night thoughts

牀前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故鄉

Bedside moonlit glow

Coats the ground like snow.

Upcast gaze to moon;

Downcast thoughts of home.

李白 Li Bai (701–762 CE)

- - -

note 1 - moon day!!!

Happy Mid-Autumn Festival! Here, have a moony little thing I made back in January 11, 2021 (and revisited in August 2022 to polish a bit).

note 2 - vibes

There is a gentle simplicity in the original poem that often doesn’t carry through in English translations. I did my best to capture the poem’s concision while remaining true to its themes and its basic structure (rhyme, meter, parallelism).

note 3 - adaptations

Note that this is the Ming Dynasty version of the famous Jing Ye Si by Li Bai. Some alternate versions may have:

1. 看月光 (viewing the moonlight) in the first line instead of 明月光 (the bright moonlight). In Chinese, I personally think the latter sounds nicer and more poetic.

2. 望山月 (gazing at the mountain-moon) in the third line instead of 望明月 (gazing at the bright moon). In Chinese, I think the former sounds more poetic; however, it is more costly in terms of English syllables. The former is also more lacking in self-insertion potential. What about all the people who want to project their childhood nostalgia but don’t live by any mountains? Grounding the poem in a specific geography can really break their immersion!

The alternate versions (看月光、望山月) tend to pre-date the Ming Dynasty version (example from the Song Dynasty linked below [1]) and are thus likely to be more faithful to the poem as originally written by Li Bai (who lived in the Tang Dynasty). But the far more popular Ming version is the one that is engraved in the hearts of Chinese schoolchildren everywhere.

- - -

[1] Example of an alternate version, compiled during the Song Dynasty by Guo Maoqian (郭茂倩):

Source 1: 《樂府詩集·卷九十·靜夜思》 Yuefu Poetry Collection: Scroll Ninety: Jing Ye Si

Source 2: Internet Archive

#李白#静夜思#li bai#jing ye si#quiet night thoughts#poetry#chinese poetry#translation#pseudotranslation#mid autumn festival

15 notes

·

View notes

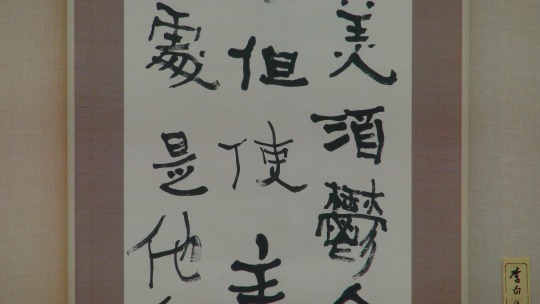

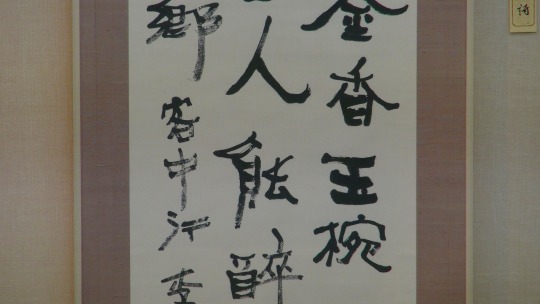

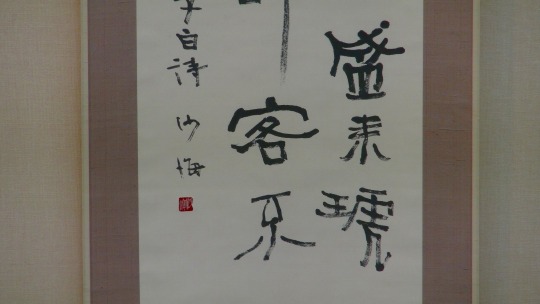

Photo

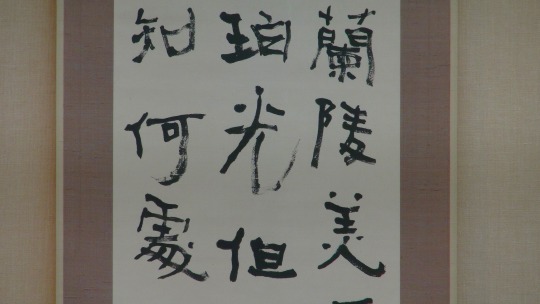

與君歌一曲

請君 爲我 傾耳聽

歌をうたうよ あなたのために

聴いてください わたしのために

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

李白驚呆了!今天終於發現,竟是因為這跨越千年的物件!這還不是最玄的,更玄的是⋯| #未解之謎 扶搖

0 notes

Text

赤壁歌 送別(李白)

二頭の龍が雌雄を決するがごとく

赤壁に構えた楼船はことごとく焼き払われ��

烈火の炎は空一面に燃え上がり雲海を照らす

この地において周瑜は曹操を打ち破ったのだ

君よ ここを旅立ち 長江のほとりで碧く澄んだ水を望むならば

天下を呑み込もうとした者たちがぶつかりあった痕跡を目にするだろう

逐一余さず手紙をしたため 昔なじみに報せてほしい

わたしはその手紙によって魂を熱く滾らせたいと願う

二龍爭戰決雌雄 赤壁樓船掃地空

烈火張天照雲海 周瑜於此破曹公

君去滄江望澄碧 鯨鯢唐突留餘跡

一一書來報故人 我欲因之壯心魄

0 notes

Text

『李白の詩』

0 notes

Text

spring-spun thoughts by li bai

(my translation; original and notes under the cut)

for you, the jade silk grasses of yan province

for me, the mulberries of qin with their drooping green bows

dear sir, in all your dreams of homecoming

do you spare any thought for your heartsick love?

i’m troubled by the spring breeze (no acquaintance of mine!)

that slips, unbidden, within my silk-gauze screens

春思(李白)

燕草如碧絲

秦桑低綠枝

當君懷歸日

是妾斷腸時

春風不相識

何事入羅幃

notes on the translation:

this translation is a little looser/more daring than other poems i've tried my hand at before... i'm not usually brave enough to strongly push my own interpretation in my translation, but i did this time because 1) it's a li bai poem so there are already countless other more traditional english translations available and 2) if you can't make fun, slightly risqué interpretations/translations of li bai, then who else is there?

the context: it is spring! a gentleman has gone to yan province (in the army) while his lover is left alone in qin. sad!

the title: 春思 is usually just translated as 'spring thoughts', but i wanted to somehow capture the parallel between the homonyms 思 (sī, 'thoughts', 'yearning') and 絲 (sī, 'silk') that's in the original. i don't know how well it carries over, but i tried to make that connection between 'spring-spun thoughts (of an absent lover)' and the jade silk grasses of yan. i also wanted to preserve the sense of causality (which is an important part of the chinese poetic tradition but not necessarily evident to the english language reader): the specific brand of yearning that she’s feeling right now is specifically caused by her sorrow that he’s not there to enjoy the spring with her

the poem: translators seem to favour reading this as a fairly typical poem of yearning, but when i read it i felt there was a slightly... arch edge to the speaker's voice? it's very possible to read it as a straight lament at their distance, but i feel like you can also imbue it with a slightly sarcastic or accusatory tone, so i wanted to let both interpretations remain open in my version. hence my translation of the second couplet in second person, to give it a slightly more confrontational edge than a simple neutral statement of fact.

the final couplet was tricky, because it seems like such a non-sequitur. i made two possible interpretations: 1) that the spring wind in her bedchamber is just another reminder of her lover's absence from her side; or alternatively, and slightly more daringly, 2) that she's obliquely warning her lover that he's left her open and unprotected, and that she's been receiving unwelcome attentions from other men while he's gone (depending on whether you read the poem as sincere or snarky, this could be a genuine warning... or a mischievous, innuendo-laden hint that he should get his arse in gear and come back home to stop her running off with someone else. i think this last interpretation is a bit out-there, but i'm quite fond of it—and also, i'm pretty sure i read somewhere that 春風 (spring wind) is a euphemism for sex, which would lend credence to my theory...). it also strikes me that my slightly irreverent reading lends itself to a third possible interpretation of the final couplet: she’s coyly warning him that if he’s gone too long, she won’t recognise him when he returns to her bed lmao. but idk! i might be reading too much into it. or maybe not! the possibilities are endless

#my translations#poetry#li bai#李白#春思#古诗#chinese poetry#poetry in translation#feedback always welcome

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

ZAZEN EN EL MONTE JINGTING

Las aves se han perdido en lo alto,

la última nube devánase en nada.

Nos sentamos solos, la montaña y yo,

hasta que sólo queda la montaña.

*

ZAZEN ON CHING-T'ING MOUNTAIN

The birds have vanished down the sky.

Now the last cloud drains away.

We sit together, the mountain and me,

until only the mountain remains.

Sam Hamill

di-versión©ochoislas

**

SENTADO SOLO EN EL MONTE JINGTING

Se perdieron las aves en lo alto,

sólo vaga una nube solitaria.

Dos que no se hartan de mirarse:

yo y el sin par monte Jingting.

Li Bai

di-versión©ochoislas

*

獨坐敬亭山

衆鳥高飛盡

孤雲獨去閒

相看兩不厭

只有敬亭山

#Sam Hamill#literatura estadounidense#poesía de Tang#zazen#absorción#versión libre#Li Bai#李白#di-versiones©ochoislas

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

李白

舞劍太帥了

#畫#影像創作#繪畫#鄭雲龍#將進酒#李白#artwork#art#illustration#drawing#doodle#ball point pen art#ball point drawing#fanart#zheng yunlong#invitation to wine#li bai

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

夢遊天姥吟 留別 唐 李白 海客談瀛洲,煙濤微茫信難求。 越人語天姥,雲霞明滅或可覩。 天姥連天向天橫,勢拔五嶽掩赤城。 天台四萬八千丈,對此欲倒東南傾。 我欲因之夢吳越,一夜飛度鏡湖月。 湖月照我影,送我至剡溪。 謝公宿處今尚在,淥水蕩漾清猨啼。 腳著謝公屐,身登青雲梯。 半壁見海日,空中聞天雞。 千巖萬轉路不定,迷花倚石忽已暝。 熊咆龍吟殷巖泉,慄深林兮驚層巔。 雲青青兮欲雨,水澹澹兮生煙。 列缺霹靂,丘巒崩摧。 洞天石扉,訇然中開。 青冥浩蕩不見底,日月照耀金銀臺。 霓爲衣兮風爲馬,雲之君兮紛紛而來下。 虎鼓瑟兮鸞迴車,仙之人兮列如麻。 忽魂悸以魄動,恍驚起而長嗟。 惟覺時之枕席,失向來之煙霞。 世間行樂亦如此,古來萬事東流水。 別君去兮何時還?且放白鹿青崖間,須行即騎訪名山。 安能摧眉折腰事權貴,使我不得開心顏。 #手寫 #手寫文字 #手抄 #手抄詩 #隨筆 #poem #chinesepoem #漢字 #漢詩 #唐詩 #tangdynasty #李白 #李太白 #詩仙 #夢遊天姥吟留別 #梦游天姥吟留别 #安能摧眉折腰事權貴使我不得開心顏 https://www.instagram.com/p/CnGvmJ1SsA4/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note